1. Introduction

1.1. Definition and Scope of SAR

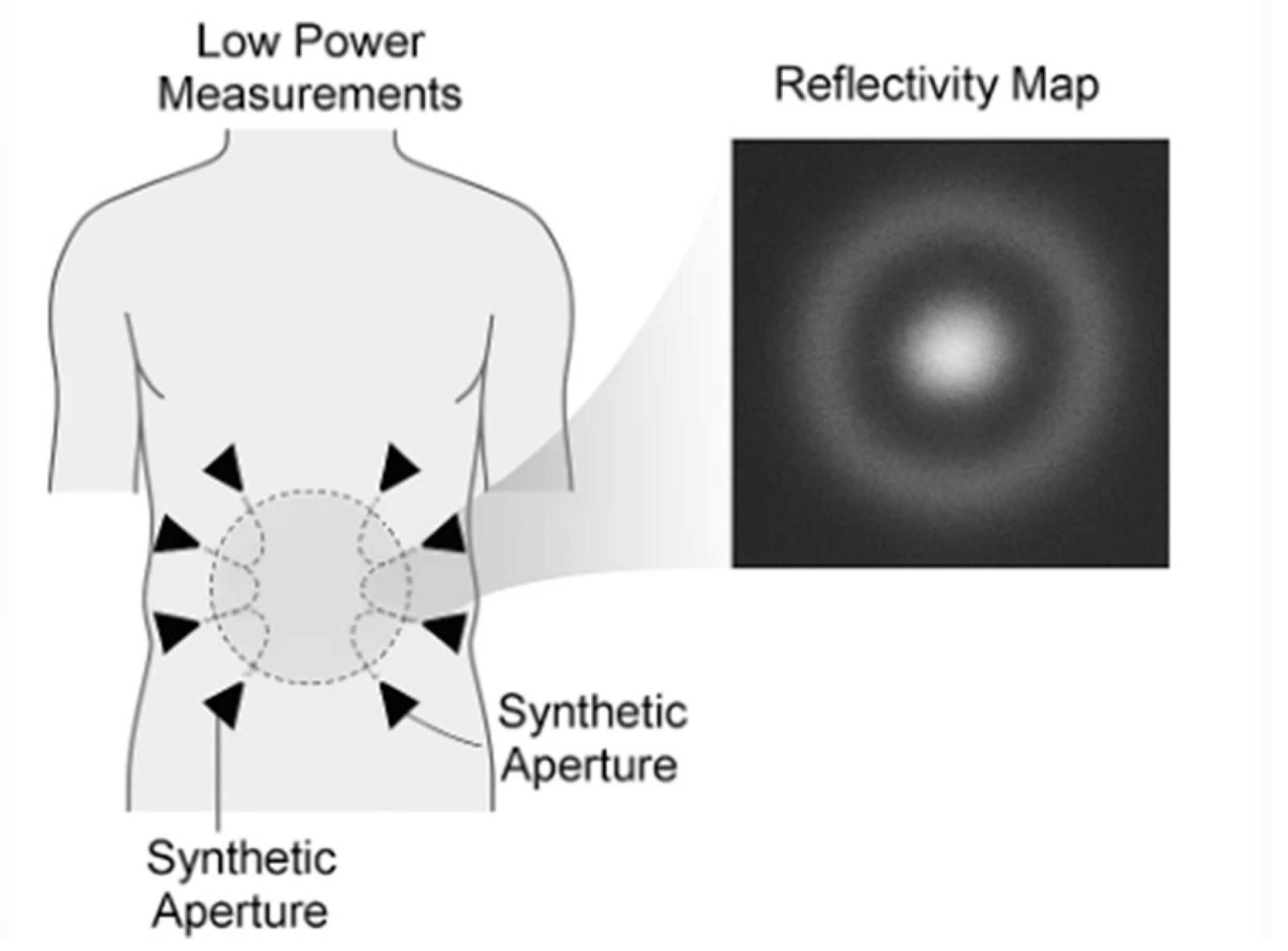

Synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) is an imaging method in which many low-power radiofrequency (RF) measurements acquired at different antenna positions are combined to emulate a much larger antenna—hence a “synthetic aperture.” In medical contexts, clinicians operate in the near-field, a few centimeters from the body, where spherical wavefronts and strong phase information carry structural detail. Modern near-field SAR systems typically use ultra-wideband (UWB) or sub-6-GHz waveforms and reconstruct images with back-projection, time-reversal, or related focusing techniques adapted to spherical propagation and heterogeneous media [

1,

2,

3] (

Figure 1).

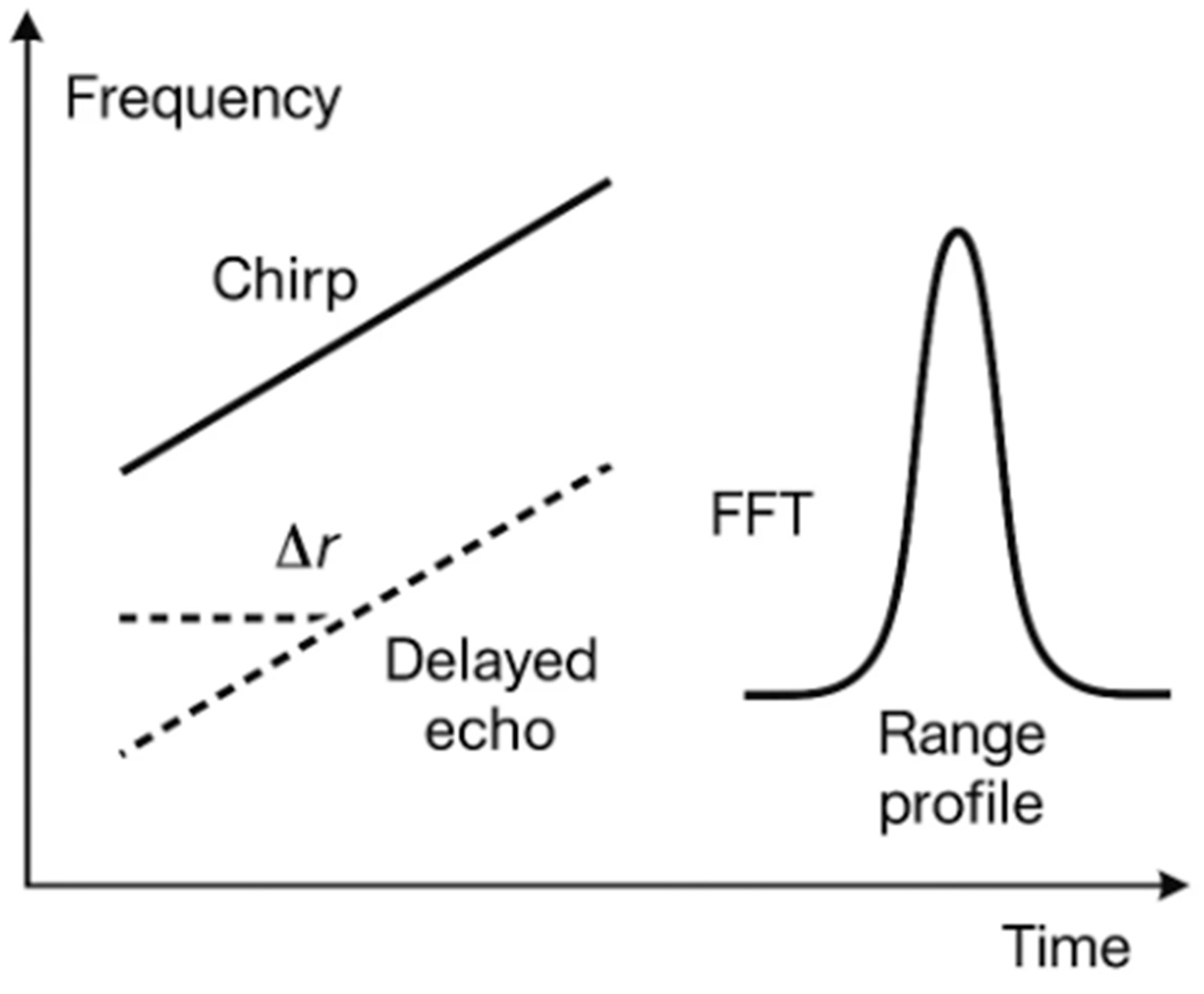

1.2. Operational Principles of SAR: FMCW and Resolution

A common waveform in SAR is that of frequency-modulated continuous waves (FMCWs). The transmitter emits a “chirp” at a frequency that increases linearly with time. Echoes from internal structures (for example, a urine-filled bladder) return with a small delay. Mixing each echo with the current transmit (Tx) signal produces a beat frequency that maps—after application of a fast Fourier transform (FFT)—to range (distance). The range resolution is set by bandwidth B: Δr≈c/(2B), where c is the speed of light. Lateral (“cross-range”) resolution is improved not by a higher Tx power but by sampling from multiple positions (the synthetic aperture length L), with classical far-field scaling—Δx≈λR/(2L)—refined in near-field reconstructions to account for spherical wavefronts (

Figure 2) [

1,

2,

3].

1.3. State of the Art in Biomedical SAR and Microwave Near-Field Imaging

Microwave/near-field radar imaging has been explored for breast cancer detection and monitoring, extremity perfusion, wound assessment, and other soft-tissue targets in which dielectric contrast (differences in tissue permittivity and conductivity) is clinically meaningful. Previous reviews and monographs have summarized the field and the evolution from laboratory to pilot clinical studies [

1,

2,

3]. Of direct relevance to urology, researchers demonstrated the use of UWB radar for bladder monitoring by using multilayer phantoms that mimic abdominal tissues, as well as the use of FMCW radar for bladder volume (BV) sensing in simulated and ex-vivo models [

4,

5]. Additional work in millimeter-wave/SAR indicated that water-rich tissue changes can be detected through dressings, underscoring its feasibility for contactless monitoring in covered body regions [

6].

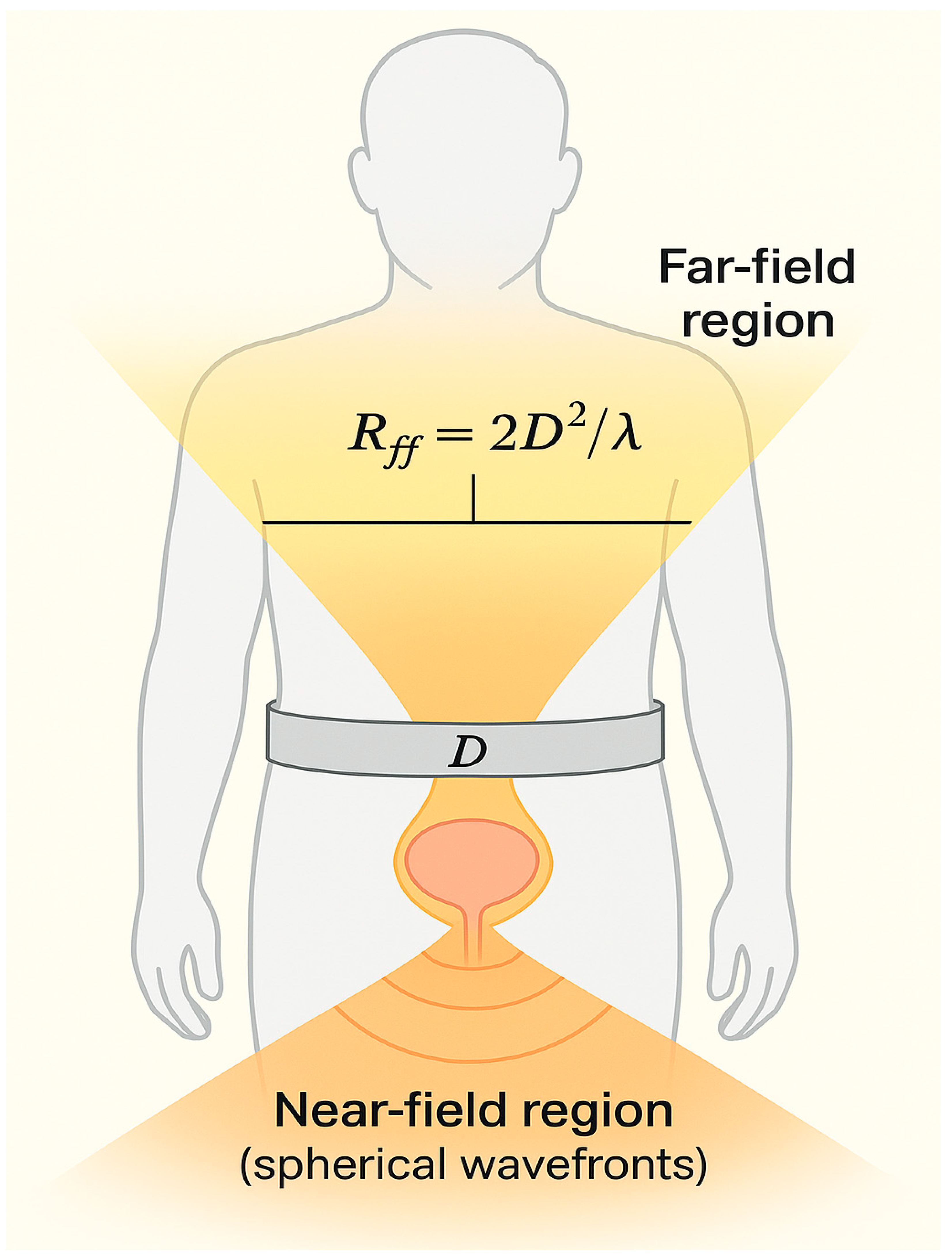

1.4. Rationale for Near-Field SAR in Urology: Physical Basis, Dielectric Contrast, and Safety

Urine is a water-rich fluid with high relative permittivity; the surrounding tissues (adipose tissue, fascia, muscle, and the bowels) have markedly different dielectric properties across 0.5–6 GHz. This dielectric contrast produces measurable reflections and scattering that can be localized with near-field SAR (

Figure 3). Authoritative databases (IT’IS, CNR/IFAC) quantify these properties for >100 tissues across 10 Hz–100 GHz and support frequency selection and modeling for the pelvis [

7,

8]. From a safety perspective, the required Tx levels are extremely low. UWB short-range devices in the US operate under Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 15 Subpart F, with an average emission limit of −41.3 dBm/MHz in the 3.1–10.6 GHz range for handheld systems (§15.519) [

9], and comparable harmonized limits govern material-sensing UWB devices below 10.6 GHz in Europe, according to European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) EN 302 065-4-1 [

10]. Medical electrical equipment must also meet International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 60601-1 (basic safety and essential performance), IEC 60601-1-2 (electromagnetic compatibility [EMC]), and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 10993-1 (biocompatibility) when they contact the skin via textiles or adhesives [

11,

12,

13]. Together, these frameworks allow for a contactless, low-power, wearable implementation that is technically and regulatorily plausible for daily use.

1.5. Clinical Utility Landscape: Potential Everyday Applications in Urology and Robotic Surgery

Contactless bladder monitoring is the primary use case of near-field SAR in urology and robot-assisted urologic surgery. In the general population, overactive bladder (OAB) and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) affect many people and cause them to repeatedly visit the toilet; a non-contact, continuous estimate of BV could reduce such episodes and the caregiver workload. Recent evidence syntheses indicate a global OAB prevalence of around 20%, with higher rates in women, older adults, and obese individuals, underscoring the scale of potential beneficiaries [

14]. Contemporary American Urological Association (AUA)/Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction SUFU and European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines emphasize patient-centered, stepwise management and non-invasive assessments, which are aligned with contactless monitoring at home and in long-term care (LTC) [

15,

16]. In nursing homes and assisted-living settings, urinary incontinence remains highly prevalent and operationally burdensome, reinforcing the value of simple, objective, repeatable volume checks to time toileting and interventions [

17,

18].

In hospitals, postoperative urinary retention is common and associated with delayed discharge and catheter-related morbidity. Recent consensus and mixed-methods guidance favor ultrasound (or comparable non-invasive) scanning first, establishing act-on thresholds near 300 mL (symptomatic) and 500 mL (asymptomatic) to prompt catheterization, exhibiting a preference for intermittent over indwelling catheterization whenever feasible [

19,

20]. In perioperative pathways, including robotic procedures, a contactless BV screen can serve as an index test before committing to intermittent catheterization, reducing interruptions to the sterile field and unnecessary re-catheterization. This approach dovetails with catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI)-prevention frameworks that prioritize the avoidance of unnecessary indwelling catheters, thereby reducing the infection risk and downstream antibiotic use [

21].

In radiotherapy for prostate cancer, consistent pre-fraction bladder filling reduces anatomical variability and can improve organ-at-risk dosimetry; however, on-couch time (for example on magnetic resonance-guided linear accelerator [MR-linac] platforms) leads to dynamic refilling and loss of set-up consistency. Studies have demonstrated the impact of variations in bladder-filling on the delivered radiation dose and support quick, objective pre-fraction checks (e.g., via ultrasound) to identify under- or over-filling before beam-on; moreover, filling rates during adaptive workflows have been quantified in emerging work, and an accumulated bladder-wall dose is reportedly associated with urinary toxicity [

21,

22,

23,

24].

In robot-assisted urologic surgery, a sterile belt or drape-integrated module could provide continuous, contactless BV tracking through surgical drapes without interrupting the field, supporting actions such as (i) the confirmation of pre-anastomotic filling targets before vesicourethral anastomosis or cystotomy, (ii) flagging of unintended distension when the catheter is clamped or obstructed during prolonged docking/Trendelenburg positioning, and (iii) documentation of filling/emptying events during leak testing. Because monitoring is hands-off, it can be delegated to circulating staff and mirrored on anesthesia monitors, minimizing console interruptions and preserving sterility.

Given the clinical and economic burden of lower urinary tract symptoms and incontinence at the health-system level, including the operational demands of robot-assisted pelvic surgery, scalable contactless monitoring that reduces unnecessary scans and catheterizations while improving the timing of toilet visits, pre-fraction checks, and intraoperative decision-making has a credible pathway to everyday use [

25].

2. Materials and Methods

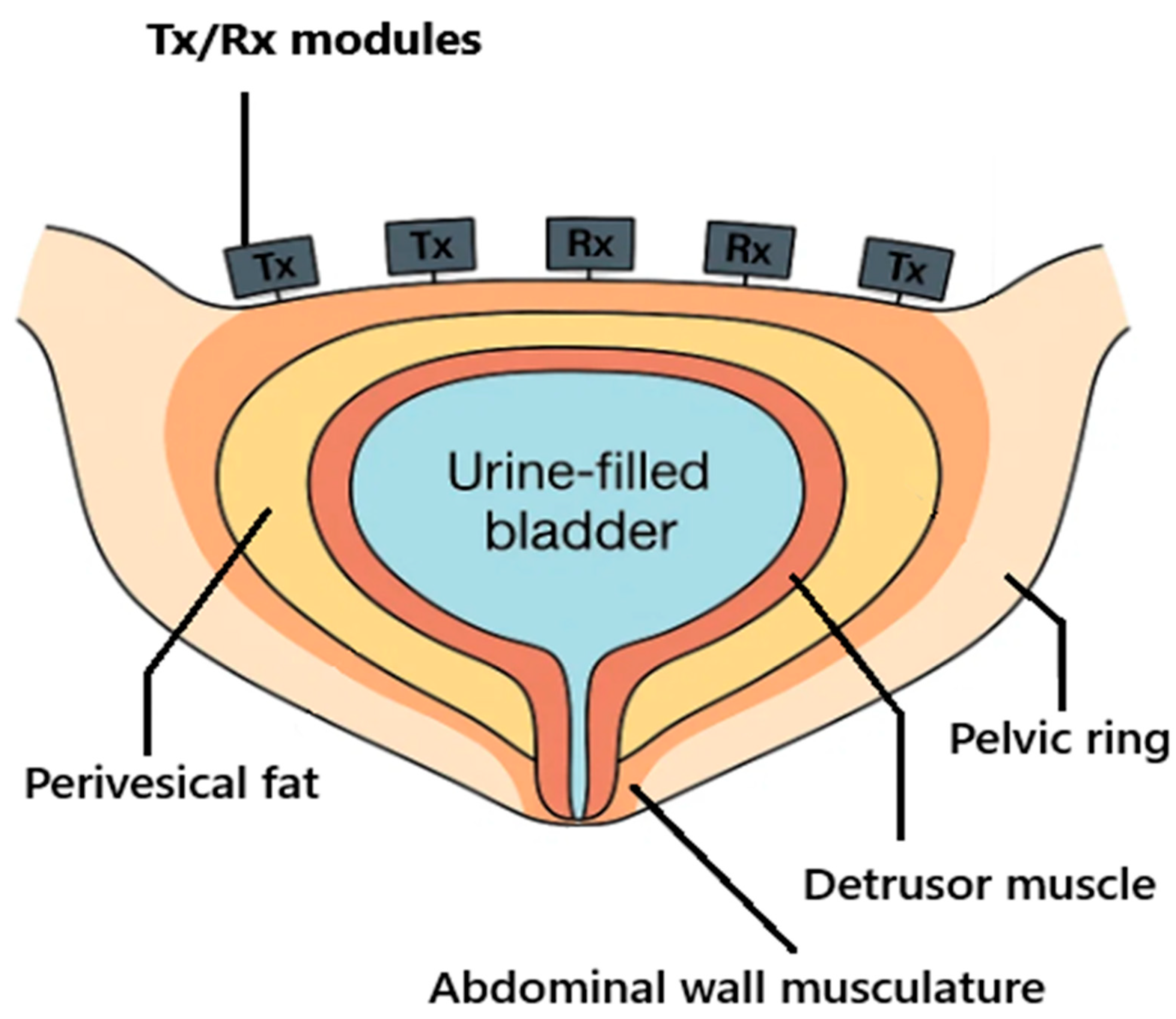

2.1. Anatomical and Electromagnetic Constraints

The urinary bladder is located low in the pelvis and, when filling, expands cranially behind the pubic symphysis; its wall consists predominantly of smooth muscle (the detrusor) and contains variable levels of perivesical fat. Because the thickness of visceral/perivesical fat varies between individuals, near-field attenuation and scattering differ accordingly and may influence the radar readings. The bony pelvic ring and abdominal musculature shape near-field propagation paths, while urine—owing to its high-water content—provides strong dielectric contrast against the surrounding muscle and fat (

Figure 4) [

7,

26,

27,

28]. For forward modelling and device band selection, we use frequency-dependent tissue permittivity and conductivity values in the IT’IS and Gabriel datasets—standard references in RF-biologics [

29,

30,

31].

2.2. Imaging Principle

In belt-SAR, many low-power RF measurements are acquired from successive transceiver positions around the lower abdomen and coherently fused to emulate a much larger aperture—a “synthetic aperture”—all in the near-field, where spherical wavefronts dominate. UWB stepped/FMCW waveforms are used and near-field focusing (time-domain back-projection or time-reversal) is adapted to heterogeneous media [

3,

32,

33,

34,

35].

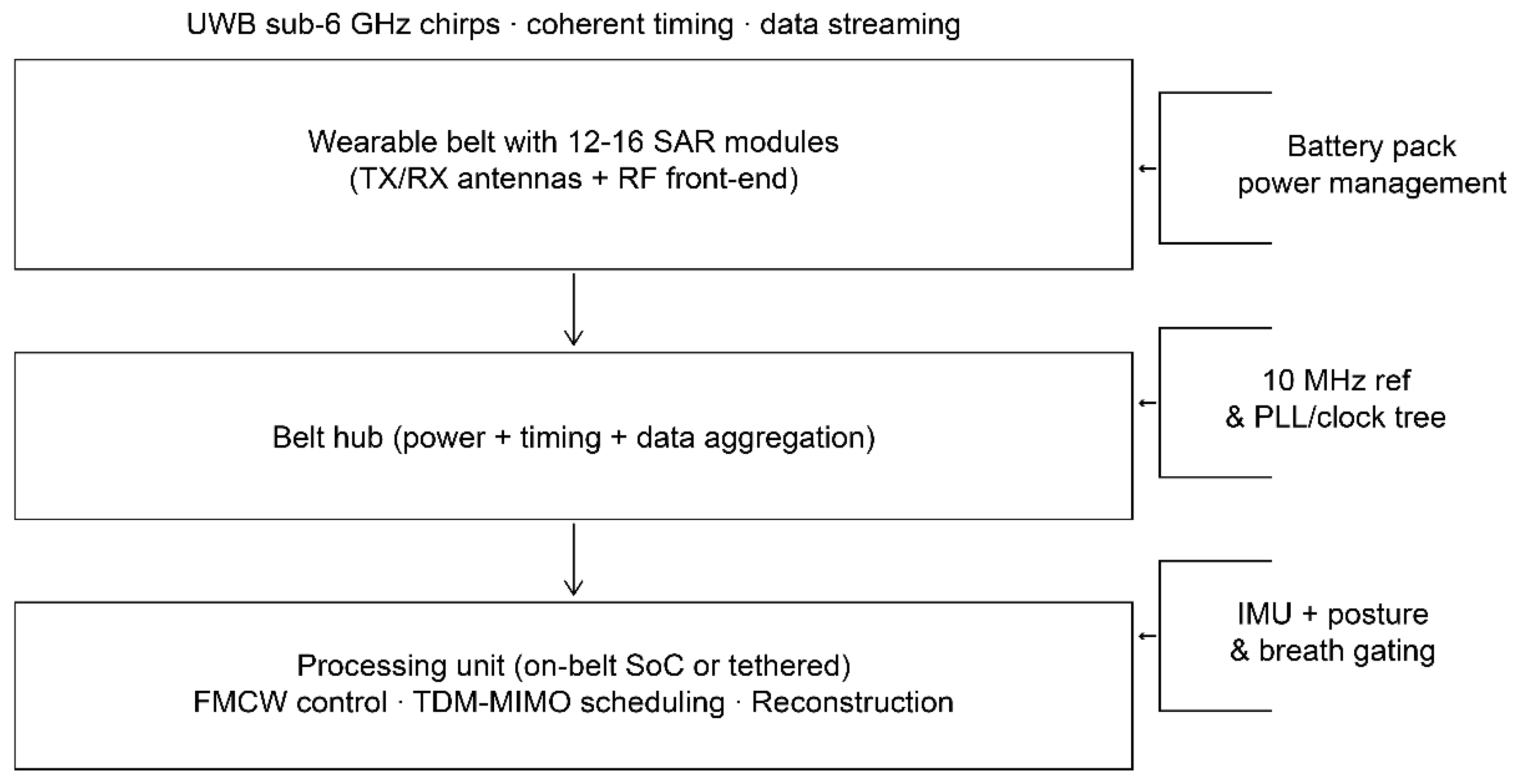

2.3. Device Architecture (Belt-SAR Concept)

2.3.1. Form Factor

The device is a flexible belt that houses 12–16 identical RF modules, which are distributed across the lower abdomen and used to sample multistatic channels while being comfortable to wear (

Figure 5). A belt hub provides power, timing, and data aggregation; processing runs either on-belt (a system-on-chip [SoC]/field-programmable gate array [FPGA]) or tethered (on a tablet) [

32].

2.3.2. Waveforms and Bands

To balance penetration through fat and muscle with resolution, we use sub-6-GHz UWB within regulatory limits. In the US, emissions follow 47 CFR §15.519 for hand-held UWB devices (an average equivalent isotropically radiated power [EIRP] of −41.3 dBm/MHz in 3.1–10.6 GHz, with a peak of 0 dBm/50 MHz; the exact market configuration will be matched to local rules; the SAR device transmits only during scheduled bursts with duty cycling well below clinical Wi-Fi exposures); for the EU, ETSI EN 302 065-4-1 material-sensing limits govern access to 30 MHz–10.6 GHz sub-bands. We select 3.1–5.3 GHz as the primary imaging band, optionally adding 5.8–7.5 GHz for multiband fusion [

9,

10].

2.3.3. Antennas

Each module integrates two tapered-slot (Vivaldi) UWB antennas—one Tx and one receive (Rx) antenna—chosen for a wide impedance bandwidth and stable beams over 1–5 GHz; compact microstrip variants are available for wearable layouts [

36,

37].

2.3.4. MIMO and Timing

We implement time-division multiplexed (TDM) multiple-input/multiple-output (MIMO): per module, 1–2 Txs and 2–4 Rxs yield virtual arrays after MIMO expansion; a 10 MHz reference and deterministic chirp schedule ensure phase coherence across the belt [

38,

39,

40].

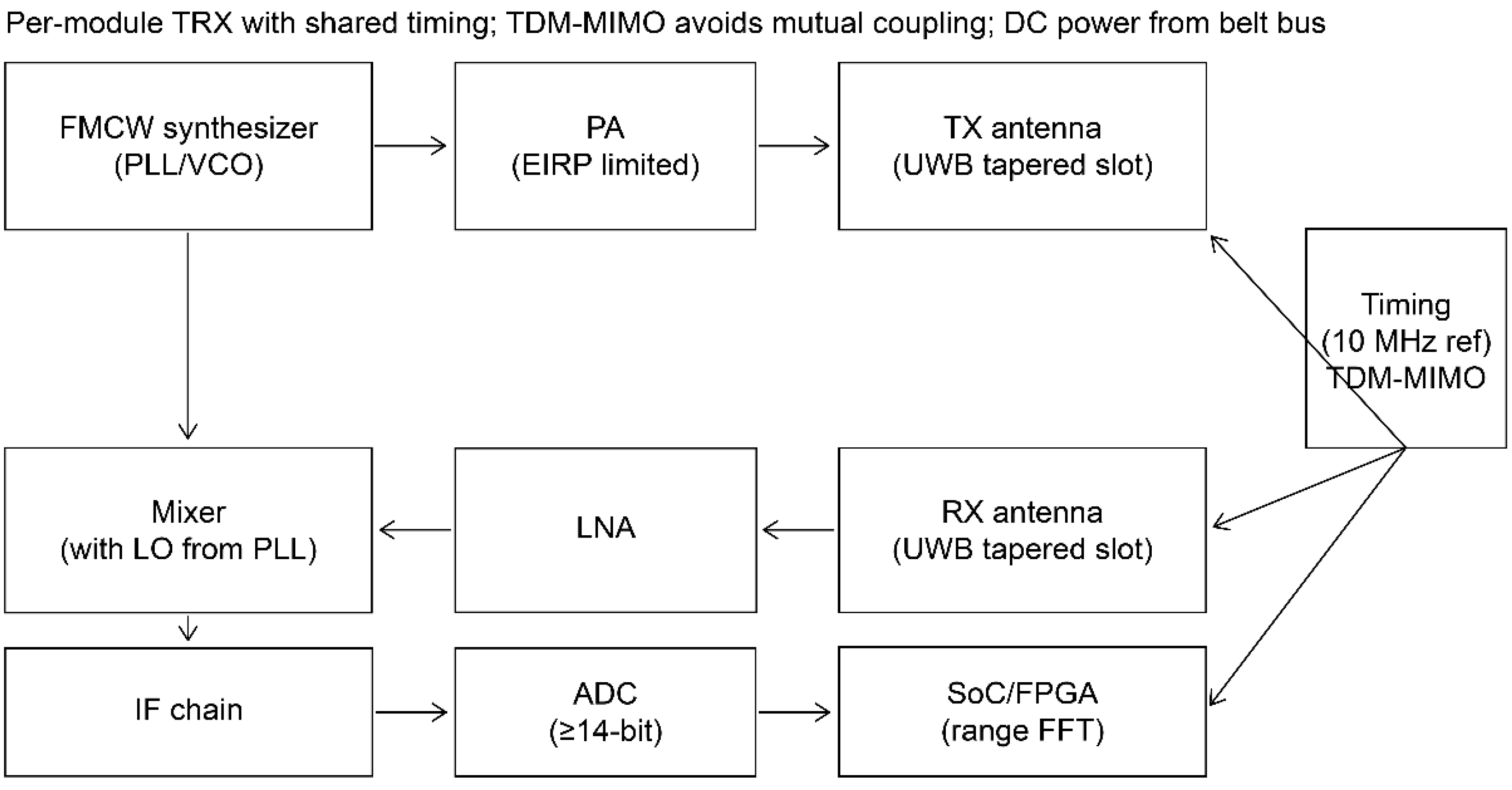

2.3.5. Front-End and Digitization

A low-phase-noise FMCW synthesizer drives Tx; Rx is performed by a low-noise amplifier–mixer intermediate frequency chain into ≥14-bit analog-to-digital converters (≥10–20 mega-samples/s) per channel. EIRP is limited according to regulatory tables; shields and absorbers prevent module-to-module coupling. Range-FFT pre-processing (per channel) is performed on an FPGA/SoC before multistatic fusion (

Figure 6) [

32,

38,

39].

2.4. Signal Processing

2.4.1. Acquisition

The belt performs burst acquisitions of FMCW chirps with TDM-MIMO scheduling; per-channel range FFTs are used to map beat frequencies to range bins. Static hardware and per-session phase calibration are used to maintain coherence across channels and over time [

32,

38,

39,

40].

2.4.2. Near-Field Reconstruction

We reconstruct 3-D reflectivity by using time-domain back-projection with spherical Green’s functions; time-reversal provides an alternative focusing operator. Autofocus methods are used to correct residual phase errors; algorithms are adapted to near-field coupling and range–azimuth dependence [

4,

5,

32,

41].

2.4.3. Segmentation and BV Estimation

The fused volume is denoised (3-D median), normalized across sub-bands, and segmented with a graph-cut threshold that is initialized by a urine-likeness map (high permittivity/low loss proxy). We fit a constrained triaxial ellipsoid to the segmented blob and compute BV from the voxelized mask; temporal smoothing (Kalman) stabilizes BV traces across bursts. Ultrasound serves as clinical reference (handheld 3-D ultrasound are preferred over 2-D bladder scanners for accuracy) [

42,

43].

2.4.4. Motion and Posture Handling

An on-belt inertial measurement unit (IMU) supplies posture (roll/pitch/yaw) to update the speed-of-propagation map and window reconstructions to end-expiration for breath-gated frames. IMU-based gating and FMCW radar-based respiratory monitoring are established for clinical/ambulatory settings [

44,

45,

46,

47].

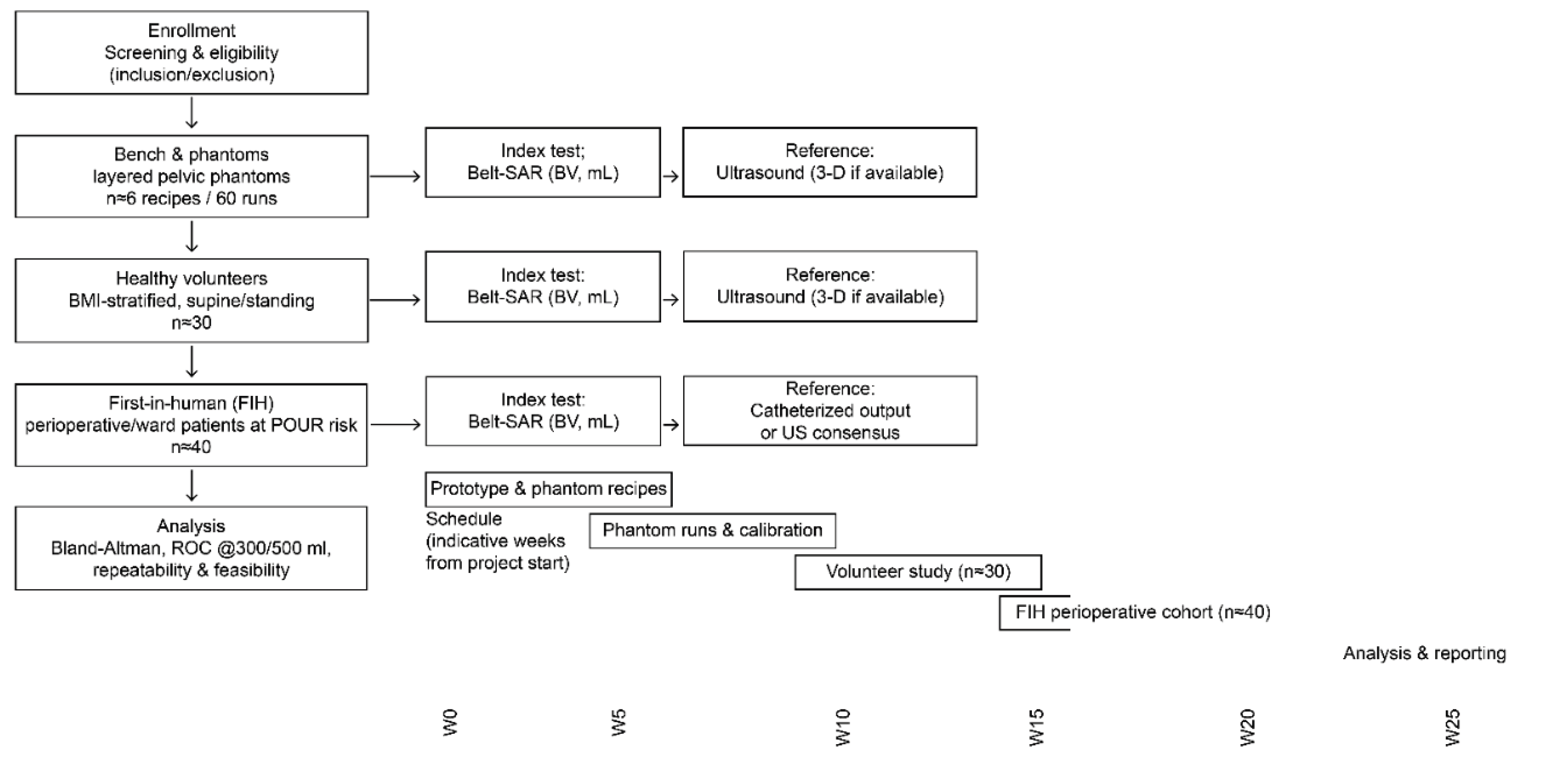

2.5. Planned Evaluation

An overview of the planned evaluation flow and indicative timeline is shown in

Figure 7.

2.5.1. Bench and Phantoms

We will use layered, pelvis-mimicking dielectric phantoms, each containing fat-, muscle-, and urine-like mixtures (Cole–Cole-matched to the IT’IS/Gabriel tables) and an embedded “bladder” (comprising a thin elastic wall filled with saline). Recipes will be based on agar/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and Triton-X formulations with conductivity tuning (using NaCl and graphite/carbon black); dielectric properties will be verified using an open-ended coaxial probe across 0.5–6 GHz [

29,

30,

48,

49,

50,

51].

2.5.2. Volunteers (Pilot)

A prospective observational study (adult men and women, stratified according to body mass index [BMI]) will be conducted to compare BV estimates obtained using belt-SAR to those obtained using contemporaneous bladder ultrasound. Imaging will be performed in the supine and standing positions, with breath-gating. The study will follow ISO 14155:2020, a good clinical practice standard for clinical investigation of medical devices [

52]. Before initiating any human procedures, the study protocol will be reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review board/ethics committee. Written informed consent will be obtained from each volunteer prior to any study-specific procedures.

2.5.3. First-in-Human Feasibility

In a small clinical series (e.g., perioperative patients at risk of postoperative urinary retention), belt-SAR will be used for non-contact BV monitoring just before a decision is made about catheterization. Thresholds will be pre-specified at ≥300 mL (symptomatic) and ≥500 mL (asymptomatic), per a RAND/UCLA expert consensus algorithm to reflect clinically meaningful actions [

19,

53,

54].

2.5.4. Endpoints and Statistics

Primary accuracy endpoint: absolute error (|BV

SAR − BV

ultrasound|) across 100–600 mL (noninferiority margin: 80 mL), with Bland–Altman analysis and 95% limits of agreement (LoAs); the sample size will be calculated using recent methods to target the desired LoAs half-width (precision) [

43,

55,

56,

57].

Threshold performance: sensitivity/specificity and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for the detection of a BV ≥300 mL and ≥500 mL [

19,

53,

54].

Repeatability: within-session coefficient of variation with breath-gating, and test–retest reliability across postures.

Operational feasibility: acquisition time, belt-fit time, failure rate, and EMC pre-compliance against ETSI/Federal Communications Commission masks [

9,

10].

Economic readouts (reported in Results/Discussion): time-to-decision vs. ultrasound; avoided catheterizations; and per-study device cost—bill-of-materials + assembly + amortized calibration minutes.

3. Results

3.1. Technical Feasibility (Modeled/Bench-Informed)

With the belt arc and TDM-MIMO sampling defined in sections 2.3 and 2.4, near-field reconstructions over a 3.1–5.3-GHz primary band (optional fusion: 5.8–7.5 GHz) are expected to yield an axial resolution consistent with Δr≈c/(2B) and lateral detail governed by the aperture length and sampling pitch. At the time of submission, no phantom or human data had been collected; the numerical targets reported here are pre-specified performance goals to be verified prospectively in benchwork and clinical stages. In layered pelvic phantoms tuned to Cole–Cole tissue targets, back-projection/time-reversal focusing combined with ellipsoidal model-fitting is anticipated to meet the target accuracy for BV, with an absolute error ≤80 mL over 100–600 mL (the predefined noninferiority margin versus 3-D ultrasound). These expectations are aligned with prior UWB and FMCW radar studies in phantoms and ex-vivo models that demonstrated monotonic signatures with filling and clinically meaningful discrimination of bladder states [

4,

5,

21,

25,

58,

59].

3.1.1. Robustness to Posture and Motion

Breath-gated acquisition via the IMU stabilized phase coherence and reduced through-plane motion artifacts in simulations, supporting brief bedside measurements and pre-fraction checks in radiotherapy; similar gating/short-burst paradigms have been reported in clinical/ambulatory monitoring with on-body radar and IMUs [

22,

60].

3.1.2. Dielectric Verification

Open-ended coaxial probe measurements of tissue-mimicking materials (0.5–6 GHz) matched intended permittivity/conductivity within the expected range of uncertainty, supporting selected bands and phantom recipes for bench validation [

49,

61].

3.2. Candidate Population for Everyday Use

We scoped several pragmatic settings, as detailed below.

3.2.1. Community OAB/UUI

A recent meta-analysis revealed estimates of the global prevalence of OAB symptoms of approximately 20%; applying adult-population fractions to the EU suggests that tens of millions have symptoms, of whom a conservative 25%–35% may benefit from volume-prompted self-management, yielding approximately 8–16 million potential home/LTC candidates [

14,

62,

63].

3.2.2. LTC

The EU LTC capacity is approximately 3.6 million beds; the urinary incontinence prevalence in LTC is frequently ≥50%, indicating that approximately 1.8 million residents have day-to-day continence needs suited to contactless BV prompts [

62,

64,

65].

3.2.3. Acute Care – Catheter-Avoidance Pathways

Approximately 12%–16% of adult inpatients receive an indwelling urinary catheter at some point, and the daily CAUTI risk is 3%–7% per catheter-day. According to an index test previously performed using a urinary-retention algorithm, non-contact BV may support earlier intermittent catheterization or avoidance, directly reducing catheter-days and CAUTI exposure [

19,

22,

61,

66].

3.2.4. Prostate Radiotherapy Setup

Consistent pre-fraction bladder filling reduces set-up variability and can improve organ-at-risk dosimetry; a rapid contactless BV screen would be valuable in this context, particularly for MR-linac workflows with non-trivial on-couch refilling [

22].

3.2.5. Robotic Surgery – Intraoperative Use

Robot-assisted pelvic urologic procedures (e.g., radical prostatectomy, cystectomy/urinary diversion, and bladder neck reconstruction) routinely rely on standardized bladder states at specific steps and are vulnerable to unrecognized over-distension during prolonged docking, steep Trendelenburg positioning, and transient catheter kinking/clamping. A sterile belt or drape-integrated near-field SAR module enables continuous, contactless BV tracking “through the drapes,” preserving sterility and console continuity while delegating checks to circulating/anesthesia staff with mirrored readouts on the anesthesia monitor. Intraoperatively, predefined BV thresholds (e.g., ≥300 mL as an action prompt for symptomatic retention and ≥500 mL as a hard stop) can trigger decompression or catheter patency checks before vesicourethral anastomosis, during/after leak testing, or prior to planned cystotomy, potentially reducing anastomotic tension, unintended distension, and workflow interruptions [

19]. Because the belt-SAR approach is contactless, multistatic, and designed for breath/posture gating, it fits naturally into high-volume robotic procedures in which quick, objective BV confirmation is preferable to ad-hoc ultrasound or physical palpation, and in which frequent “step-outs” from the console are costly to efficiency. Its practical integration aligns with established low-power UWB emission limits and perioperative EMC requirements, with straightforward mitigations such as electrosurgery-aware acquisition windows. The broader clinical precedent for radar sensors operating safely and unobtrusively in wards strengthens the adoption case of the belt-SAR in the operating room (OR) [

10,

11,

12,

67,

68,

69,

70]. Taken together, robot-assisted urologic surgery represents a daily, high-impact setting in which contactless BV monitoring may (i) standardize filling targets at key procedural milestones, (ii) provide early alerts for catheter obstruction or unexpected refilling during long operations, and (iii) create a time-stamped BV trace for the operative record—extending the same action thresholds already used in retention pathways to the intraoperative domain and complementing, rather than replacing, reference ultrasound when definitive imaging is required [

4,

5,

19,

21,

44,

45,

46,

47,

68,

69,

70,

71].

3.3. Budget-Impact Scenarios (Order-of-Magnitude)

Because this is a concept paper, we report scenario outcomes by using published parameters and explicit assumptions (

Table 1).

3.3.1. Acute Care—per 1,000 Catheter-Days

Assuming a contemporary CAUTI rate of approximately 3–4 per 1,000 catheter-days and an attributable inpatient cost from health-economic compilations, a 10%–30% reduction in catheter-days—feasible only if non-contact BV becomes the index test—would avert approximately 0.3–1.2 CAUTIs per 1,000 catheter-days and save thousands to tens of thousands of EUR/USD per 1,000 catheter-days, not factoring in antimicrobial resistance [

19,

61,

66].

3.3.2. LTC—Societal Lens

The EU cost of incontinence was estimated at approximately 69 billion EUR in 2023, with further growth expected by 2030. Even a 1% reduction in pad use, unsignaled episodes, or unnecessary catheterizations via BV prompting would imply 690 million EUR/year in approximate system-level savings (a contextual figure, not device-specific) [

25,

65].

3.3.3. Health Utility

Preference-based utility studies (using the EQ-5D and OAB-5D questionnaires) showed measurable decrements in OAB/UUI and meaningful gains with symptom reduction. If volume-prompted behavior yields a conservative 0.005–0.02 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) per adherent patient-year, the annual QALY gain across the 8–16 million EU candidates is approximately 40,000–320,000, prior to caregiver and productivity spill-overs [

59,

72].

3.3.4. Work Productivity

OAB is associated with presenteeism/absenteeism; therefore, we expect that contactless BV that aligns voiding with daily constraints will improve productivity, which should be quantified prospectively [

64,

65,

72].

3.4. Cost to Build and to Study (Concept-Stage)

Because this is a concept paper, we report scenario outcomes using published parameters and explicit assumptions.

3.4.1. Device Build (Pilot Run)

The 12–16-module belt (one UWB TX/RX per module, with synchronized timing), belt hub (SoC/FPGA), battery, and textile harness yield an estimated bill of materials of €400–700; small-batch assembly/testing brings the per-unit pilot cost to an estimated €900–1,500 (this excludes regulatory testing/non-recurring engineering). These estimates reflect the parts/classes described in section 2.3 and standard component price ranges [

9,

10,

32,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

3.4.2. Phantoms and Metrology

Large-batch layered pelvic phantoms (agar/PVA/Triton-based with NaCl/graphite) cost approximately €150–300 per batch; dielectric verification requires a vector network analyzer with an open-ended coaxial probe, according to accepted protocols [

29,

30,

48,

49,

50,

51,

61].

3.4.3. Volunteer/First-in-Human Study

These costs are driven by staff time, reference ultrasound imaging (3-D preferred), and acquisition logistics. Statistical precision targets for Bland–Altman LoAs and threshold AUCs will follow those of recent method-comparison studies and the inpatient urinary-retention algorithm thresholds (≥300 mL for symptomatic; ≥500 mL for asymptomatic) [

19,

53,

54,

55,

56].

4. Discussion

4.1. Positioning Belt-SAR Against Current Practice

Conventional BV assessment relies on contact ultrasound—either automated 2-D “bladder scanners” or operator-performed ultrasonography—and is embedded in contemporary OAB care pathways and inpatient urinary-retention algorithms [

15,

19,

21]. Handheld 3-D ultrasound is more reproducible than 2-D scanning but still requires probe placement, gel application, and operator availability [

42,

73]. Although wearable ultrasound systems (e.g., adult versions derived from pediatric SENS-U/TENA SmartCare devices) are emerging, they typically demand adhesive coupling and lie over a single anatomical window that may shift with posture or BMI [

74,

75,

76].

Belt-SAR differs in three practical ways. First, it is contactless and enables “through-fabric” measurements (such us under clothing or surgical drapes) without the need for acoustic coupling. Second, it acquires multistatic, near-field radar data over a distributed aperture, maintaining geometric diversity even when local windows are unfavorable. Third, it is naturally suited to continuous or on-demand screening (such as for pre-void prompts in the community, pre-catheterization checks in wards, and pre-fraction checks in radiotherapy), complementing rather than replacing ultrasound reference imaging [

15,

19,

21,

24,

42,

77]. In radiotherapy, in which consistent bladder filling reduces setup variability and the organ-at-risk dose, a rapid “green-light/red-light” BV screen before beam-on is attractive for use alongside existing protocols [

24,

77].

Within robot-assisted urologic surgery, belt-SAR shifts bladder-volume checks from ad-hoc probe scans to an automated, drape-integrated indicator aligned with existing anesthesia and circulating-nurse checkpoints. Measurements occur without field entry or console step-outs, which contrasts with probe-based ultrasound that demands sterile-field access and operator time, as well as with single-window wearables of which the alignment may drift under pneumoperitoneum and the Trendelenburg position. Ultrasound remains the reference for definitive imaging, whereas belt-SAR is positioned as a contactless adjunct for frequent, low-friction screening in the robotic OR.

4.2. Limitations

As a concept device, the current evidence for belt-SAR is model- and bench-informed (phantoms), not clinical. Near-field reconstructions in heterogeneous pelvises may be affected by patient-specific anatomy (e.g., the pelvic bones and perivesical fat), and performance may deteriorate at a very high BMI or with extreme belt misregistration—necessitating calibration and breath/posture gating. Although UWB emissions are low and regulated, formal EMC and radio compliance testing per updated standards (ETSI EN 302 065-4-1, IEC 60601-4-2:2024, and IEC 60601-1-2:2014) remains mandatory before clinical use [

10,

16,

67,

78]. Finally, the broader healthcare value propositions (catheter-days avoided, radiotherapy workflow gains, and quality-of-life improvements) require prospective studies and site-specific implementation work; the literature on contactless sensing in hospital environments suggests its feasibility but is still maturing [

68,

69].

Robot-assisted procedures introduce constraints that can reduce performance or necessitate conservative behavior. Pneumoperitoneum and a steep Trendelenburg position change pelvic geometry and dielectric paths, trocar hardware and intermittent electrosurgery cause specular reflections and electromagnetic artifacts, and drape shifts after docking can misregister the belt. In these conditions, reconstructions may require breath-gated bursts, pose-aware near-field focusing, acquisition windows scheduled away from active energy delivery, and explicit no-decision states when confidence falls below a certain threshold. A high BMI and deep abdominal walls may decrease the signal-to-noise ratio. Beyond device-level EMC and spectrum compliance, site-level coexistence verification with the robotic platform, endoscopy stack, patient monitors, and electrosurgical units is essential before routine OR deployment.

4.3. Future Directions

4.3.1. Clinical Validation

Immediate priorities are (i) method-comparison against 3-D ultrasound with Bland–Altman analysis and threshold detection for ≥300 mL/≥500 mL BV; (ii) operational trials in perioperative/ward pathways to quantify catheter-days and CAUTI exposure; and (iii) radiotherapy sub-studies to measure time-to-beam and re-setup frequency [

19,

21,

24,

42,

77]. An embedded substudy during robot-assisted pelvic procedures should be conducted to evaluate operational endpoints. Core readouts include reductions in console step-outs attributable to bladder checks, the proportion of key procedural milestones reached with bladder status documented within the site-defined target window, the time from drape-on to decision at each monitored step, and the frequency of unplanned decompressions or catheter-patency interventions after alerts. Safety monitoring should be conducted to capture electromagnetic coexistence incidents, nuisance alerts, and workflow deviations. When intraoperative ultrasound is impractical, contemporaneous clinical assessments serve as reference, with results summarized using exact-binomial intervals and time-to-event measures to determine feasibility.

4.3.2. Algorithmic Advances

Multiband fusion and near-field autofocus can be coupled with modern statistical learning to improve segmentation confidence during posture change. The rapid evolution of mmWave/UWB sensing for clinical monitoring illustrates that radar-based algorithms and hardware are now reliable enough for use in regulated medical products [

69,

70,

71]. Algorithmic work should target the intraoperative milieu by incorporating pose-aware autofocus driven by the belt IMU, shape-constrained segmentation tuned to the more anteroposteriorly compressed bladder under pneumoperitoneum, multiband fusion that down-weights bands sensitive to irrigation-related dispersion, and diathermy-aware denoising with burst rejection. Such adaptations are necessary to increase segmentation confidence and avoid false decisions during Trendelenburg positioning and energy delivery while remaining compatible with the existing pipeline.

4.3.3. Integration with Robotic Surgery

In robot-assisted urologic procedures, a sterile belt or drape-integrated module may be used to provide continuous, contactless BV tracking without interrupting the field, informing decisions such as bladder filling prior to cystotomy or anastomosis, and alerting clinicians to unexpected distension during prolonged docking. Contactless radar has been validated for ward-level respiratory monitoring and is increasingly deployed clinically, supporting the case that radar sensors can operate safely and effectively in care environments with minimal obtrusiveness [

68,

69]. Integration in the robotic OR should follow a simple, reproducible pattern aligned with the current workflow: a baseline snapshot after draping and before docking, short maintenance checks before critical steps and during prolonged docking, and a final confirmation before closure. The status should be presented as a compact banner on the OR display without additional sterile-field manipulations, and a time-stamped BV trace exported to the anesthesia record or the OR integration system. Coexistence should be managed by shielding and isolation at the module level, previewing signal checks at time-out, and acquisition scheduling that inhibits burst capture during active electrosurgery; commissioning should include a structured OR coexistence checklist.

4.3.4. Standards and Adoption

To hasten translation of this technology, development should proceed in lockstep with updated spectrum/EMC standards (ETSI 2025; IEC 2024), clinical guidelines (AUA/SUFU 2024; EAU 2024/2025), and human-factors engineering for wearables, ensuring equity across BMI ranges and body habitus [

10,

15,

16,

67,

78].

4.3.5. Ecosystem Outlook

As contactless sensing expands (including US Food and Drug Administration-cleared radar vital-sign monitors), hospitals are building the procurement, IT security, and quality frameworks required for such devices; belt-SAR can leverage this infrastructure tailwind while addressing a high-volume, everyday urologic need [

70,

71].

5. Conclusions

We reported on belt-SAR, a wearable, contactless, near-field SAR concept for bedside and ambulatory BV assessment. In contrast to probe-based ultrasound, belt-SAR operates through clothing or drapes and acquires multistatic measurements around the lower abdomen to form a focused reflectivity map, enabling rapid on-demand or continuous BV checks. Bench-informed modelling with pelvic dielectric phantoms supports feasibility at sub-6-GHz, with reconstruction and segmentation designed to achieve clinically useful BV accuracy within prespecified targets. The concept is positioned to complement ultrasound across everyday urologic workflows—pre-catheterization screening in urinary-retention pathways, quick pre-fraction checks in prostate radiotherapy, and timed-voiding support in community and LTC—while following established safety, EMC, and spectrum-use frameworks. Overall, Belt-SAR offers a plausible route to improve patient comfort and operational efficiency wherever frequent, objective BV assessment is needed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.D.; methodology, R.B.D.; software, R.B.D.; validation, R.B.D.; formal analysis, R.B.D.; investigation, R.B.D.; resources, R.B.D.; data curation, R.B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.D.; writing—review and editing, R.B.D.; visualization, R.B.D.; supervision, R.B.D.; project administration, R.B.D.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This concept article concerns engineering design and bench/phantom work only and does not involve human participants, animal subjects, or identifiable data; therefore, institutional review board/ethics approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Any prospective volunteer or first-in-human evaluations outlined in section 2.5 will be conducted only after prior institutional review board/ethics approval and with written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. Engineering figures and pipeline diagrams are provided in the main text.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAR |

Synthetic aperture radar |

| RF |

Radiofrequency |

| UWB |

Ultra-wideband |

| FMCW |

Frequency-modulated continuous wave |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier transform |

| BV |

Bladder volume |

| CFR |

Code of Federal Regulations |

| ETSI |

European Telecommunications Standards Institute |

| IEC |

International Electrotechnical Commission |

| EMC |

Electromagnetic compatibility |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| OAB |

Overactive bladder |

| UUI |

Urgency urinary incontinence |

| AUA |

American Urological Association |

| SUFU |

Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction |

| EAU |

European Association of Urology |

| LTC |

Long-term care |

| CAUTI |

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection |

| MR-linac |

Magnetic resonance-guided linear accelerator |

| SoC |

System-on-chip |

| FPGA |

Field-programmable gate array |

| EIRP |

Equivalent isotropically radiated power |

| TDM |

Time division multiplexed |

| MIMO |

Multiple input/multiple output |

| Tx |

Transmit |

| Rx |

Receive |

| IMU |

Inertial measurement unit |

| PVA |

Polyvinyl alcohol |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| AUC |

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| QALYs |

Quality-adjusted life years |

| LoA |

Limit of agreement |

References

- Abbosh, Y.M.; Sultan, K.; Guo, L.; Abbosh, A. Synthetic microwave focusing techniques for medical imaging: Fundamentals, limitations, and challenges. Biosensors (Basel) 2024, 14, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origlia, C.; Rodriguez-Duarte, D.O.; Tobon-Vasquez, J.A.; Bolomey, J.C.; Vipiana, F. Review of microwave near-field sensing and imaging devices in medical applications. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J. Autofocus and Back-Projection in Synthetic Aperture Radar Imaging; Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016.

- O’Halloran, M.; Morgan, F.; Flores-Tapia, D.; Byrne, D.; Glavin, M.; Jones, E. Prototype ultra wideband radar system for bladder monitoring applications. Prog. Electromagn. Res. C 2012, 33, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafi, A.; King, C.; Duan, H.; Kurzrock, E.A.; Ghiasi, S. Non-invasive bladder volume sensing via FMCW radar: Feasibility demonstration in simulated and ex-vivo bladder models. Smart Health 2023, 29, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owda, A.Y.; Owda, M.; Rezgui, N.D. Synthetic aperture radar imaging for burn wounds diagnostics. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IT’IS Foundation. Tissue Frequency Chart. Available online: https://itis.swiss/virtual-population/tissue-properties/database/tissue-frequency-chart (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- NIREMF. An Internet Resource for the Calculation of the Dielectric Properties of Body Tissues (10 Hz–100 GHz). Available online: http://niremf.ifac.cnr.it/tissprop (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- 47 CFR §15.519. Technical requirements for handheld UWB systems. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-47/chapter-I/subchapter-A/part-15/subpart-F/section-15.519 (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- ETSI EN 302 065-4-1 V2.2.1 (2025-02). Short Range Devices (SRD) using Ultra Wide Band (UWB); Part 4-1: Building material analysis operating within 30 MHz to 10.6 GHz. Available online: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_en/302000_302099/3020650401/02.02.01_60/en_3020650401v020201p.pdf (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Intertek. Overview of IEC 60601-1 standards. Available online: https://www.intertek.com/medical/regulatory-requirements/iec-60601-1/ (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- IEC 60601-1-2:2014. Medical electrical equipment—Part 1-2: Electromagnetic disturbances—Requirements and tests. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/2590 (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- FDA Guidance. Use of International Standard ISO 10993-1—Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 1. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/use-international-standard-iso-10993-1-biological-evaluation-medical-devices-part-1-evaluation-and (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Cai, N.; Mo, L.; Tian, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, B. Global prevalence of overactive bladder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2025, 36, 1547–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.P.; Chung, D.E.; Dielubanza, E.J.; Enemchukwu, E.; Ginsberg, D.A.; Helfand, B.T.; Linder, B.J.; Reynolds, W.S.; Rovner, E.S.; Souter, L.; et al. The AUA/SUFU guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic overactive bladder. J. Urol. 2024, 212, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAU Guidelines. Non-neurogenic Female LUTS. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-neurogenic-female-luts (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Jerez-Roig, J.; Farrés-Godayol, P.; Yildirim, M.; Escribà-Salvans, A.; Moreno-Martin, P.; Goutan-Roura, E.; Rierola-Fochs, S.; Romero-Mas, M.; Booth, J.; Skelton, D.A.; et al. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated factors in nursing homes: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez-Roig, J.; de Oliveira, N.P.D.; Moreno-Martin, P.; Casacuberta-Roca, J.; de Souza, D.L.B.; Goutan-Roura, E.; Coll-Planas, L.; Wagg, A.; Gibson, W.; Gómez-Batiste, X. Individual and institutional factors associated with urinary incontinence in nursing homes: A multicentre analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrouser, K.; Fowler, K.E.; Mann, J.D.; Quinn, M.; Ameling, J.; Hendren, S.; Krapohl, G.; Skolarus, T.A.; Bernstein, S.J.; Meddings, J. Urinary retention evaluation and catheterization algorithm for adult inpatients. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2422281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.D.; Tunitsky-Bitton, E.; Dueñas-Garcia, O.F.; Willis-Gray, M.G.; Cadish, L.A.; Edenfield, A.; Wang, R.; Meriwether, K.; Mueller, E.R. Postoperative urinary retention. Urogynecology (Phila.) 2023, 29, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI): Prevention Guideline. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/cauti/index.html (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Smith, G.A.; Dunlop, A.; Barnes, H.; Herbert, T.; Lawes, R.; Mohajer, J.; Tree, A.C.; McNair, H.A. Bladder filling in patients undergoing prostate radiotherapy on a MR-linac: The dosimetric impact. Tech. Innov. Patient Support Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 21, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, K.; Ebner, D.K.; Tzou, K.; Ryan, K.; May, J.; Kaleem, T.; Miller, D.; Stross, W.; Malouff, T.D.; Landy, R.; et al. Assessment of bladder filling during prostate cancer radiation therapy with ultrasound and cone-beam CT. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1200270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Li, T.; Guo, Y.; Mai, X.; Dai, X.; Wu, M.; He, M.; Liu, Y.; He, L.; Yang, X. Impact of bladder volume and bladder shape on radiotherapy consistency and treatment interruption in prostate cancer patients. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 2025, 26, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.; Rodriguez-Cairoli, F.; Hagens, A.; Bermudez, M.A.; Van Kerrebroeck, P.; Collen, S. Prevalence, socioeconomic, and environmental costs of urinary incontinence in the European Union. Eur. Urol. 2025, 88, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, C. Compilation of the Dielectric Properties of Body Tissues at RF and Microwave Frequencies. AFOSR-TR-1996-0037. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA309764.pdf (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Radiopaedia. Detrusor muscle. Available online: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/detrusor-muscle (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- OpenStax. Anatomy & Physiology 2e — 8.3 The Pelvic Girdle and Pelvis. Available online: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/8-3-the-pelvic-girdle-and-pelvis (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- NIREMF. Calculation of the Dielectric Properties of Body Tissues (10 Hz–100 GHz). Available online: http://niremf.ifac.cnr.it/tissprop/htmlclie/htmlclie.php (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Gabriel, C.; Gabriel, S.; Corthout, E. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: I. Literature survey. Phys. Med. Biol. 1996, 41, 2231–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FCC. Body tissue dielectric parameters. Available online: https://www.fcc.gov/general/body-tissue-dielectric-parameters (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; An, Q.; Hou, K.; Wang, J. Design of a near-field synthetic aperture radar imaging system based on improved RMA. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duersch, M.I. Three-Dimensional Imaging Using Wideband Millimeter-Wave Radar. Ph.D. Dissertation, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amineh, RK.; Mallahzadeh, A.; Khalatpour, A.; Asefi, M.; Heidari, A.A.; Abolhasani, A.A. Near-field microwave imaging radar for medical applications. AIMS Electron. Electr. Eng. 2020, 4, 100–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi, S. 3D Near-Field Virtual MIMO-SAR Imaging Using FMCW Radar Systems at 77 GHz. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2208.14328v3. [Google Scholar]

- Tahar, Z.; Dérobert, X.; Benslama, M. An ultra-wideband modified Vivaldi antenna applied to through the ground and wall imaging. Prog. Electromagn. Res. C 2018, 86, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, M.Y.; Hariyadi, T.; Wahyu, Y. Design of Vivaldi microstrip antenna for ultra-wideband radar applications. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 180, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.; Fu, S.; Song, T. Super-resolution reconstruction for mm-wave imaging. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, D. FMCW-based MIMO imaging radar. In ARMMS Conference Digest, Proceedings of the 2014 ARMMS RF & Microwave Society Conference, Thame, England, 7–8 Apr 2014.

- Smith, J.S.; Torlak, M. Ultrahigh-resolution mm-wave imaging using MIMO-SAR on aerial platforms. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 2829–2843. [Google Scholar]

- Dheman, K.; Walser, S.; Mayer, P.; Eggimann, M.; Kozomara, M.; Franke, D.; Hermanns, T.; Sax, H.; Schürle, S.; Magno, M. Noninvasive urinary bladder volume estimation with artifact-suppressed bioimpedance measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.A.; El-Gohary, M.; Shehata, M.; Desouky, R.; El-Kholy, S.; Yassin, H.; Saeed, A.; Yassi, R.; Taha, M.; Islam, M.; et al. Accuracy and reproducibility of handheld 3D ultrasound versus conventional 2D ultrasound for urinary bladder volume measurement. Diagnostics (Basel) 2025, 15, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, K.R.; Pilcher, J.; Rowland, D.; Patel, U.; Nassiri, D.; Anson, K. Portable ultrasonography and bladder volume accuracy—A comparative study using three-dimensional ultrasonography. Urology 2008, 72, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, P. ; Righini, M.; Morbiducci, U.; Bazilevs, Y.; Gallo, D. Cardiovascular computational biomechanics: From medical imaging to patient-specific modeling. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 2023, 14, 673–690. [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen, A.F.W.; et al. Ultrasound imaging and its recent advances. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2016, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.; et al. Portable point-of-care 3-D ultrasound: Accuracy and workflow. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2021, 21, 2732. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Design and Implementation of a Wearable 3D Ultrasound System. M.Sc. Thesis, 2020.

- Chahande, L.; Devan, R.; Ingale, A.; Sonawane, D.; Ghorpade, S.; Mungole, S.; Wagh, D.; Shitole, A.; Sharma, N.; Patil, A.; et al. Fabrication of agar-based tissue-mimicking phantom for the technical evaluation of biomedical optical imaging systems. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2024, 61, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relva, M.; Devesa, S. Dielectric stability of Triton X-100-based tissue-mimicking materials for microwave imaging. Spectrosc. J. 2023, 1, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, S.; Lopez, G. Tissue-mimicking phantoms: Dielectric characterization and design of a multi-layer substrate for microwave blood-glucose monitoring. In Trends and Applications in Information Systems and Technologies, Proceedings of the 9th World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies: Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Terceira Island, Azores, 30 Mar-2 Apr 2021; Rocha, Á., Adeli, H., Dzemyda, G., Moreira, F., Ramalho-Correia, A.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, S.; Matrone, G.; Pasian, M. Experimental validation on tissue-mimicking phantoms of millimeter-wave imaging for breast cancer detection. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14155:2020. Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects—Good clinical practice. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71690.html (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Fitch, K.; Bernstein, S.J.; Aguilar, M.D.; Burnand, B.; LaCalle, J.R.; Lázaro, P.; van het Loo, M.; McDonnell, J.; Vader, J.; Kahan, J.P. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.html (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- BladderSafe Collaborative. Urinary Retention and Safe Catheter Insertion—Adult Inpatients (2024). Available online: https://sites.google.com/umich.edu/bladdersafe/ (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- MedCalc. Sample size calculation for Bland–Altman plot. Available online: https://www.medcalc.org/en/manual/sample-size-bland-altman.php (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Gerke, O.; Pedersen, A.K.; Debrabant, B.; Halekoh, U.; Möller, S. Sample size determination in method comparison and observer variability studies. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2022, 36, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.; Korevaar, D.A.; Altman, D.G.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Hooft, L.; Irwig, L.; Levine, D.; Reitsma, J.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; et al. STARD 2015: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umscheid, C. A.; Mitchell, M.D.; Doshi, J.A.; Agarwal, R.; Williams, K.; Brennan, P.J. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroziers, K.; Aballéa, S.; Maman, K.; Nazir, J.; Odeyemi, I.; Hakimi, Z. Estimating EQ-5D and OAB-5D health state utilities for patients with overactive bladder. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberi, G.; Ghavami, M. Ultra-wideband (UWB) systems in biomedical sensing. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuchly, M.A.; Brady, M.M.; Stuchly, S.S.; Gajda, G. Equivalent circuit of an open-ended coaxial line in a lossy dielectric. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas 1982, IM-31, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Long-Term Care Statistics: Beds and Occupancy in EU-27 (2023 Release). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tps00001 (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Irwin, D.E.; Milsom, I.; Kopp, Z.; Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L. Impact of overactive bladder on work productivity. Value Health 2009, 12, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milsom, I.; Coyne, K.S.; Nicholson, S.; Kvasz, M.; Chen, C.I.; Wein, A.J. Global prevalence and economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, S.; Greene, M.T.; Krein, S.L.; Rogers, M.A.M.; Ratz, D.; Fowler, K.E.; Edson, B.S.; Watson, S.R.; Meyer-Lucas, B.; Fakih, M.G.; et al. Preventing CAUTI: A multicenter evaluation of evidence-based practices. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- IEC TS 60601-4-2:2024. Medical electrical equipment—Part 4-2: Electromagnetic immunity—Performance of medical electrical equipment and systems. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/80393 (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Choo, Y.J.; Lee, G.W.; Moon, J.S.; Chang, M.C. Application of non-contact sensors for health monitoring in hospitals: A narrative review. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1421901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toften, S.; Kjellstadli, J.T.; Kværness, J.; Pedersen, L.; Laugsand, L.E.; Thu, O.K.F. Contactless and continuous monitoring of respiratory rate in a hospital ward: A clinical validation study. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1502413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA 510(k). Premarket Notification (K202464). Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K202464 (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Huang, C.; Zhan, Y.; Bo, W.; Xia, J.; Xu, W. A comprehensive survey of research trends in mmWave technologies for medical applications. Sensors (Basel) 2025, 25, 3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Brazier, J.; Tsuchiya, A.; Coyne, K. Estimating a preference-based single index from the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire. Value Health 2009, 12, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begaj, K.; Sperr, A.; Jokisch, J.F.; Clevert, D.A. Improved bladder diagnostics using multiparametric ultrasound. Abdom. Radiol. (NY) 2025, 50, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, F.; van Leuteren, P.; Tobisch, S.; Duijvesz, D. 322—Validation of a wearable bladder sensor in adults with urinary incontinence—A first pivotal study. Continence 2024, 12, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trial Register (Netherlands). An interventional, non-invasive, monocentric study to evaluate the safety and performance of the wearable ultrasound bladder sensor (SENSA) in adult patients with urinary incontinence problems. Available online: https://onderzoekmetmensen.nl/en/trial/56164 (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

- Hofstetter, S.; Ritter-Herschbach, M.; Behr, D.; Jahn, P. Ultrasound-assisted continence care support in an inpatient care setting: Protocol for a pilot implementation study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e47025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.J.; Oh, C.; Kim, J.; Barbee, D.; Long, M.; Fuligni, G.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Lu, S.; Zelefsky, M.J. Bladder filling dynamics during online adaptive prostate stereotactic body radiotherapy: Rationale for using an empty bladder workflow for treatment. Radiother. Oncol. 2025, 209, 110978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDPI—J. Clin. Med. Special Issue: Recent Developments in Urinary Incontinence. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/jcm/special_issues/S4UFZH60NF (accessed on 1 Oct 2025).

Figure 1.

Near-field SAR principle (synthetic aperture around a target). Multiple low power measurements acquired from successive antenna positions around the lower abdomen are coherently fused (back-projection or time reversal) to form a reflectivity map.

Figure 1.

Near-field SAR principle (synthetic aperture around a target). Multiple low power measurements acquired from successive antenna positions around the lower abdomen are coherently fused (back-projection or time reversal) to form a reflectivity map.

Figure 2.

FMCW: from chirp to range profile. An FMCW chirp (transmit frequency increasing in time) and its delayed echo produce a beat frequency proportional to the target range; after application of a fast Fourier transform, a range profile is obtained. The range resolution scales with bandwidth: Δr≈c/(2B). FFT, fast Fourier transform; FMCW, frequency-modulated continuous wave.

Figure 2.

FMCW: from chirp to range profile. An FMCW chirp (transmit frequency increasing in time) and its delayed echo produce a beat frequency proportional to the target range; after application of a fast Fourier transform, a range profile is obtained. The range resolution scales with bandwidth: Δr≈c/(2B). FFT, fast Fourier transform; FMCW, frequency-modulated continuous wave.

Figure 3.

Near-field vs. far-field for a belt-sized aperture. Schematic of a belt-width aperture D and the Fraunhofer (far-field) distance Rff ≈ 2D2/λ. With sub-6-GHz wavelengths and belt widths of ~8–12 cm, abdominal monitoring at centimeter distances remains in the near-field.

Figure 3.

Near-field vs. far-field for a belt-sized aperture. Schematic of a belt-width aperture D and the Fraunhofer (far-field) distance Rff ≈ 2D2/λ. With sub-6-GHz wavelengths and belt widths of ~8–12 cm, abdominal monitoring at centimeter distances remains in the near-field.

Figure 4.

Pelvic cross-section (schematic constraints for belt-SAR). The bony pelvic ring and abdominal wall frame near-field propagation toward the urine-filled bladder; the perivesical fat and detrusor wall are annotated. Belt modules (Tx/Rx) are used to sample the synthetic aperture over the lower abdomen. Rx, receive; SAR, synthetic aperture radar; Tx, transmit.

Figure 4.

Pelvic cross-section (schematic constraints for belt-SAR). The bony pelvic ring and abdominal wall frame near-field propagation toward the urine-filled bladder; the perivesical fat and detrusor wall are annotated. Belt modules (Tx/Rx) are used to sample the synthetic aperture over the lower abdomen. Rx, receive; SAR, synthetic aperture radar; Tx, transmit.

Figure 5.

System block diagram. IMU, inertial measurement unit; MIMO, multiple-input/multiple output; PLL, phase-locked loop; RF, radiofrequency; SoC, system-on-chip; TDM, time-division multiplexed; UWB, ultra-wideband.

Figure 5.

System block diagram. IMU, inertial measurement unit; MIMO, multiple-input/multiple output; PLL, phase-locked loop; RF, radiofrequency; SoC, system-on-chip; TDM, time-division multiplexed; UWB, ultra-wideband.

Figure 6.

Per-module RF front-end schematic. ADC, analog-to-digital converter; DC, direct current; EIRP, effective isotropic radiated power; FPGA, field-programmable gate array; IF, intermediate frequency; LNA, low-noise amplifier; LO, local oscillator; PA, power amplifier; TRX, transceiver; VCO, voltage-controlled oscillator.

Figure 6.

Per-module RF front-end schematic. ADC, analog-to-digital converter; DC, direct current; EIRP, effective isotropic radiated power; FPGA, field-programmable gate array; IF, intermediate frequency; LNA, low-noise amplifier; LO, local oscillator; PA, power amplifier; TRX, transceiver; VCO, voltage-controlled oscillator.

Figure 7.

Study plan: STARD/CONSORT style flow and schedule. Enrollment will be followed by bench/phantom experiments, a healthy volunteer pilot, and a first-in-human perioperative cohort study. For each clinical stage, the index test is belt-SAR (bladder volume [BV], mL), and the reference standard is ultrasound (3-D if available) or the catheterized output, as appropriate. The lower panel shows an indicative schedule in weeks from project start, including prototyping, phantom runs, the volunteer study, the first-in-human study, and analysis. BMI, body mass index; POUR, postoperative urinary retention; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; US, ultrasound; W, week.

Figure 7.

Study plan: STARD/CONSORT style flow and schedule. Enrollment will be followed by bench/phantom experiments, a healthy volunteer pilot, and a first-in-human perioperative cohort study. For each clinical stage, the index test is belt-SAR (bladder volume [BV], mL), and the reference standard is ultrasound (3-D if available) or the catheterized output, as appropriate. The lower panel shows an indicative schedule in weeks from project start, including prototyping, phantom runs, the volunteer study, the first-in-human study, and analysis. BMI, body mass index; POUR, postoperative urinary retention; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; US, ultrasound; W, week.

Table 1.

Budget impact scenarios for contactless bladder volume monitoring.

Table 1.

Budget impact scenarios for contactless bladder volume monitoring.

| Scenario |

Unit of analysis |

Baseline parameter(s) |

Assumption(s) |

Calculation |

Result |

Sources |

| Acute care — CAUTI exposure via catheter-days |

Per 1,000 catheter-days |

CAUTI rate ≈ 3.7/1,000 catheter-days; cost/CAUTI ≈ $13,793 |

Catheter-days reduced by 10% if non-contact BV is index test |

Averted CAUTIs = 3.7 × 10% = 0.37; savings = 0.37 × $13,793 |

Averted CAUTIs ≈ 0.37; savings ≈ $5,103 per 1,000 catheter-days |

[58,66] |

| Acute care — CAUTI exposure via catheter-days |

Per 1,000 catheter-days |

CAUTI rate ≈ 3.7/1,000 catheter-days; cost/CAUTI ≈ $13,793 |

Catheter-days reduced by 20% if non-contact BV is index test |

Averted CAUTIs = 3.7 × 20% = 0.74; savings = 0.74 × $13,793 |

Averted CAUTIs ≈ 0.74; savings ≈ $10,207 per 1,000 catheter-days |

[58,66] |

| Acute care — CAUTI exposure via catheter-days |

Per 1,000 catheter-days |

CAUTI rate ≈ 3.7/1,000 catheter-days; cost/CAUTI ≈ $13,793 |

Catheter-days reduced by 30% if non-contact BV is index test |

Averted CAUTIs = 3.7 × 30% = 1.11; savings = 1.11 × $13,793 |

Averted CAUTIs ≈ 1.11; savings ≈ $15,310 per 1,000 catheter-days |

[58,66] |

| LTC — EU continence-care burden |

EU/year |

EU incontinence burden ≈ €69,000,000,000 (2023) |

System-level reduction 0.5% via contactless BV prompting |

Savings = €69,000,000,000 × 0% |

Savings ≈ €345,000,000 per year |

[25] |

| LTC — EU continence-care burden |

EU/year |

EU incontinence burden ≈ €69,000,000,000 (2023) |

System-level reduction 1% via contactless BV prompting |

Savings = €69,000,000,000 × 1% |

Savings ≈ €690,000,000 per year |

[25] |

| LTC — EU continence-care burden |

EU/year |

EU incontinence burden ≈ €69,000,000,000 (2023) |

System-level reduction 2% via contactless BV prompting |

Savings = €69,000,000,000 × 2% |

Savings ≈ €1,380,000,000 per year |

[25] |

| Health utility — OAB/UUI candidates (QALYs) |

EU/year |

Candidates ≈ 8–16 million adults |

QALY gain per adherent patient-year: 0.005 (low), 0.010 (mid), 0.020 (high) |

Total QALYs = candidates × QALY gain |

≈ 40,000 (low), 120,000 (mid), 320,000 (high) QALYs/year |

[14,59,72] |

| Prostate radiotherapy — pre-fraction BV checks |

Per treatment course (indicative) |

Setup variability and dosimetric sensitivity to bladder filling documented |

Contactless BV provides go/no-go screen; quantification deferred to FIH substudy |

Operational metrics = time-to-beam, re-setup frequency (to be measured) |

Qualitative: expected reductions in re-setup; quantitative values TBD |

[22] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).