1. Introduction

The fall armyworm (

Spodoptera frugiperda [J. E. Smith]) is a highly destructive, polyphagous lepidopteran native to the tropical and subtropical Americas. It feeds on more than 350 plant species, including maize, rice, wheat, sorghum, soybean, and cotton [

1,

2]. In December 2018,

S. frugiperda entered Yunnan Province from Myanmar and—owing to its strong migratory capacity and ecological plasticity—rapidly spread across 27 provinces, causing substantial maize yield losses in Southwest and South China. It has since become a major migratory pest that threatens China’s maize production and national food security [

3,

4].

Beyond chemical control, transgenic insect-resistant maize has become a key tactic against

S. frugiperda. Since the first commercial approval of the Bt maize event Bt176 in the United States in 1996, hybrids expressing distinct insecticidal proteins (e.g., Cry1Ab, Cry1F) have been widely adopted to target lepidopteran pests such as the Asian corn borer (

Ostrinia furnacalis) and the corn earworm (

Helicoverpa zea Boddie) [

5,

6]. Among these, many Bt maize hybrids (e.g., those expressing Cry1F or the pyramided proteins Cry1A.105 and Cry2Ab2) have also demonstrated high efficacy against the subsequently invasive fall armyworm and, as a result, have become one of the primary control measures against this pest in countries such as the United States, Canada, and in South America [

7,

8,

9]. In China, insect-resistant maize events such as DBN9936(

cry1Ab +

epsps) and Ruifeng 125 (

cry1Ab +

cry2Aj +

epsps ) have received production-use safety certificates and contribute to management of this pest [

10].

Robust resistance evaluation is indispensable during the research, deregulation, and stewardship of transgenic maize to identify transformation events suitable for commercialization. Laboratory bioassays of Rodriguez-Chalarca and colleagues [

11] reported > 90% mortality of

S. frugiperda larvae on VT2P maize (expressing Cry1A.105 and Cry2Ab2) and VT3P maize (expressing Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, and Cry3Bb1). Zhao and colleagues [

12] further showed that Bt maize DBN3601T carrying the

cry1Ab and

vip3Aa19 transgenes caused 100% mortality of neonates by day 3 when they fed on leaves collected at different plant growth stages. Nevertheless, toxicity differs among Bt proteins (e.g., Cry1Ab, Cry1F, Vip3A), and expression levels and efficacy can vary across transformation events and genetic backgrounds [

13,

14]. These realities underscore the need for standardized, operational procedures for resistance evaluation in maize. However, systematic, detailed protocols for infestation and rating against

S. frugiperda remain limited. For instance, the leaf damage rating methods proposed by Williams et al. [

15] and by Toepfer et al. [

16], respectively, lack standardized specifications for larval age and infestation density, which likely compromises the comparability of experimental results. Therefore, this study aims to establish rapid, accurate, and detailed laboratory and field infestation methods by analyzing the effects of infestation timing, larval density, and larval age on the degree of maize damage. Our goal is to deliver efficient, reliable protocols for resistance assessment that improve evaluation throughput while reducing research and development costs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Maize Materials and S. frugiperda Colony

The transgenic maize hybrid Xianda 901ZL, developed by China National Seed Group Co., Ltd., carries the transgenes vip3Aa20, cry1Ab, epsps, and pat, conferring insect resistance and herbicide tolerance; this hybrid has obtained biosafety certification in China. The nontransgenic control was the commercial hybrid Guidan 162, which does not contain insect-resistance traits and was purchased from the market.

S. frugiperda colony used in this study was obtained from Baiyun Industrial Co., Ltd. (Jiyuan, Henan, China). After several generations of laboratory rearing, larvae were used for subsequent experiments. All rearing was conducted in programmable climate chambers at 26 ± 1 °C, a 16:8 h light: dark photoperiod, and 70–80% relative humidity. Eggs were incubated until hatch; neonates were reared in plastic boxes (29.3 × 19.3 × 9.6 cm) on artificial diet. After reaching the third instar, larvae were transferred to 24-well plastic rearing plates (13 × 8.5 × 2.8 cm; one larva per well) and maintained individually until pupation. Newly emerged adults were held in rearing cages (40 × 40 × 40 cm) and supplied with 10% (v/v) honey solution for water and nutrients; egg masses were collected for subsequent trials.

The artificial diet followed Zhao et al. [

12] with minor modifications. Briefly, soy flour, wheat bran, brewer’s yeast, sorbic acid, and casein were weighed and mixed thoroughly. Separately, 20 g agar was dissolved by boiling in 1300 mL distilled water and the dry mixture was incorporated with stirring. When the mixture cooled to 70–80 °C, 2 mL formaldehyde and 4 mL glacial acetic acid was added and mixed evenly. Ascorbic acid and a multivitamin premix were dissolved in 100 mL distilled water and added when the mixture cooled to ~60 °C. The diet was stirred thoroughly, dispensed into bags, allowed to cool and solidify at room temperature, and stored at 4 °C for further use. (Appropriate personal protective equipment should be used when handling formaldehyde.)

Maize seedlings of the transgenic hybrid Xianda 901ZL and the nontransgenic hybrid Guidan 162 were first raised in the laboratory and transplanted at the two-leaf, one-whorl stage into round plastic pots (20 cm diameter) filled with a 1:1 mixture of local soil and organic substrate to support normal growth for subsequent screenhouse experiments. The screenhouse was covered with a plastic film at the top to protect the plants from rain, and cultivation was carried out at ambient temperature. In parallel, a cohort of uniform seedlings was transplanted to the Teaching and Research Base of South China Agricultural University (Guangzhou, Guangdong Province). The field was planted at 60 cm row spacing and 30 cm within-row spacing to ensure adequate growing space. Both screenhouse and field maize plants were managed using standard agronomic practices—regular irrigation and fertilization, manual weeding, and no insecticide applications throughout the maize growth cycle. To ensure material security, the field site was managed by dedicated personnel with continuous monitoring.

All husbandry complied with institutional biosafety and pest-containment guidelines. No insecticides were applied to experimental plants, and all plant materials and insect cultures were handled to prevent escape.

2.2. Laboratory Bioassays

Young whorl leaves were collected from transgenic and nontransgenic maize plants grown in a screenhouse to the 4–6 leaf stage. In the laboratory, leaf surfaces were gently wiped with moistened sterile gauze to remove dust and debris, then cut into 4 cm² pieces and placed in Petri dishes (60 mm diameter). S. frugiperda larvae were gently transferred to the dishes with a fine camel-hair brush. Five S. frugiperda larvae were introduced per dish as one replicate, with five replicates established for each larval age group of 1–4 days post-hatching (D1–D4).

Fresh, unpollinated silks were collected from ears at the silking stage. For each Petri dish, 1 g of intact silks were weighed and placed as substrate. An additional 1 g of silks from the same source were supplemented when the original silks were completely eaten. Five S. frugiperda larvae were introduced per dish as one replicate, with five replicates established for each larval age group of 1–4 days post-hatching.

Kernels at the grain-filling stage were placed individually into the wells of 24-well rearing plates (one kernel per well). For each larval age (D1–D4), two larvae were introduced per well, with five replicate plates per treatment.

All assays were maintained in programmable climate chambers at 26 °C, a 16:8 h light: dark photoperiod, and 70–80% relative humidity. Maize tissue injury and larval survival were monitored daily and photographically documented. Mortality was defined as larvae exhibiting flaccid, blackened bodies with no movement upon gentle probing. The survival (%) was measured as follows:

2.3. Screenhouse Potted-Plant Infestation Trials

Using a fine camel-hair brush, 20 S. frugiperda larvae were gently placed the whorl funnel of maize plants at the whorl stage (4–6-leaf or 8–10-leaf stage). Larval ages were D1, D2, D3, or D4. Each plant constituted one replicate (n = 3 plants per treatment). D2 larvae were inoculated onto maize plants at the 4–6-leaf stage at densities of 10, 20, 30, or 40 larvae per plant. Each plant was treated as one replicate (n = 3 plants per treatment). Plant injury was assessed on days 6 and 10 post-infestation by recording the number of notched leaves and the type of whorl damage; plants were photographed with a B500 digital camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Field Infestation Trials

Using a fine camel-hair brush, 20 S. frugiperda larvae were gently placed the whorl funnel of maize plants in the field at the whorl stage (4–6-leaf or 8–10-leaf stage). Larval ages were D1, D2, D3, or D4. Each plant constituted one replicate (n = 3 plants per treatment). All treated plants were laid out in the field following a randomized arrangement, with the rule of selecting one plant at every two-plant interval. D3 larvae were inoculated onto maize plants at the 4–6-leaf stage at densities of 10, 20, 30, or 40 larvae per plant. Each plant was treated as one replicate (n = 3 plants per treatment). All treated plants were laid out in the field following a randomized arrangement, with the rule of selecting one plant at every two-plant interval. Plant injury was assessed on days 7 and 12 post-infestation by recording the number of notched leaves and the type of whorl damage; plants were photographed with a B500 digital camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

2.5. Data Analysis

All experimental data were statistically analyzed using Excel 2019. The survival rate of Spodoptera frugiperda was analyzed for significance using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software. Data were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variances. Percentage data were subjected to arcsine square root transformation before analysis of variance. For normally distributed data, we used one-way ANOVA to determine the effect of treatment, and means were compared using Tukey’s post-hoc test. For the nonnormally distributed data, we used a nonparametric method. the Kruskal-Wallis test, with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatment groups (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Laboratory Bioassays of Transgenic Maize Resistance to S. frugiperda

To investigate the differences in maize injury caused by

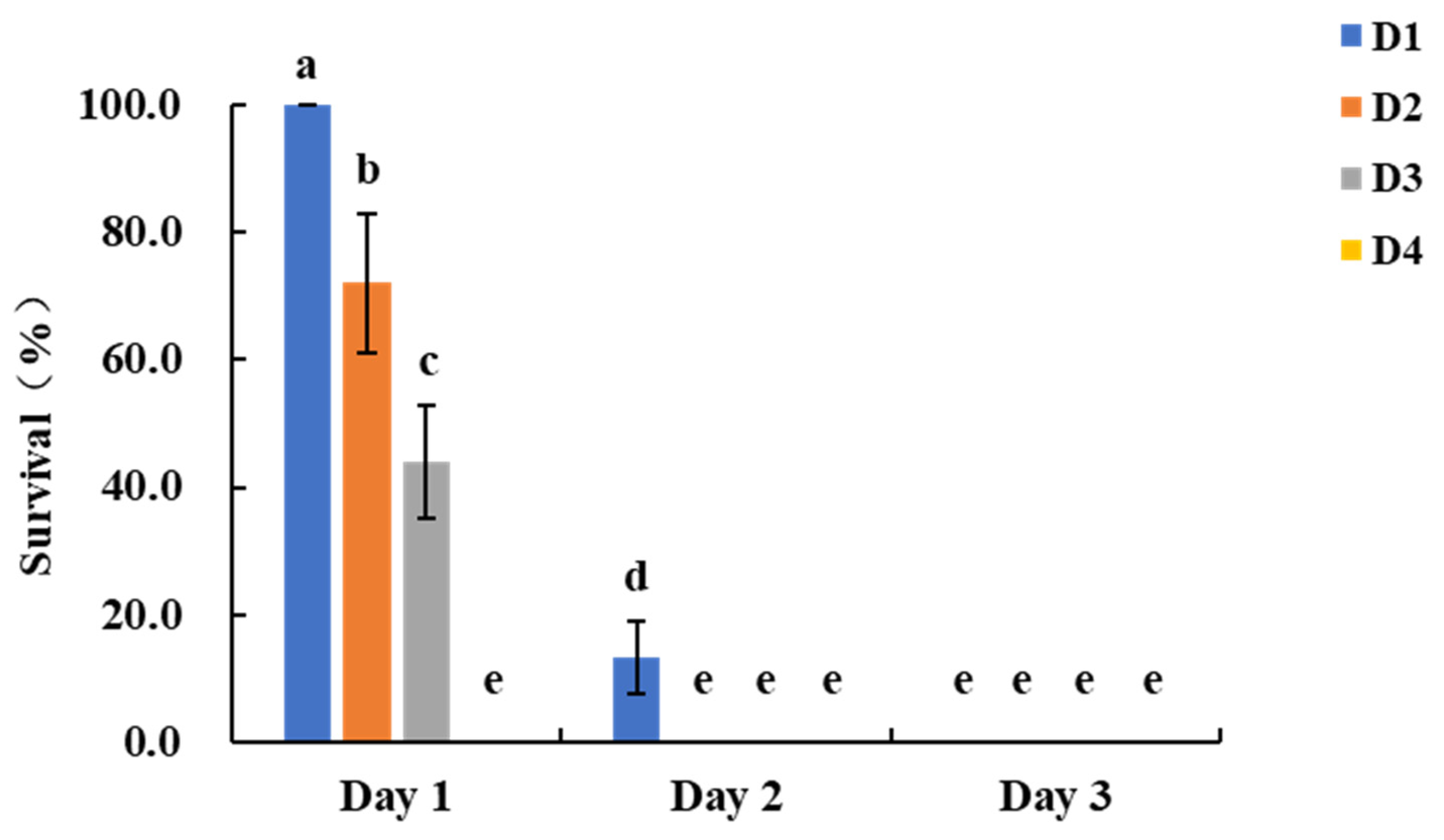

S. frugiperda larvae of different ages, we conducted assays using whorl leaves, silks, and kernels as feeding substrates. Maize injury and larval survival were observed and recorded daily, evaluating the mortality progression on transgenic maize and the developmental and feeding performance of larvae on nontransgenic maize. In the leaf assay, larvae feeding on transgenic maize exhibited the following survival rates on day 1 post-infestation: D1 larvae 100.0 ± 0.0%, D2 larvae 72.0 ± 11.0%, D3 larvae 44.0 ± 8.9%, and D4 larvae 0.0 ± 0.0%. On day 2, survival rates were 13.3 ± 5.8%, 0.0 ± 0.0%, and 0.0 ± 0.0% for D1, D2, and D3 larvae, respectively, while by day 3, no D1 larvae survived (

Figure 1). In contrast, nontransgenic maize plants experienced extensive feeding damage, with large, irregular holes and notched leaves, and in severe cases, only the leaf veins remained, particularly from D2 and D3 larvae. Transgenic maize leaves showed only slight feeding marks (

Figure S1). Given that the experimental cycle for D2 larvae was shorter than that for D3 and D4 larvae, and considering both time and economic costs, we recommend an infestation protocol for laboratory bioassays that uses five D2 larvae, with larval survival rate assessed on day 2 post-infestation, for the evaluation of resistance in transgenic maize whorl leaves.

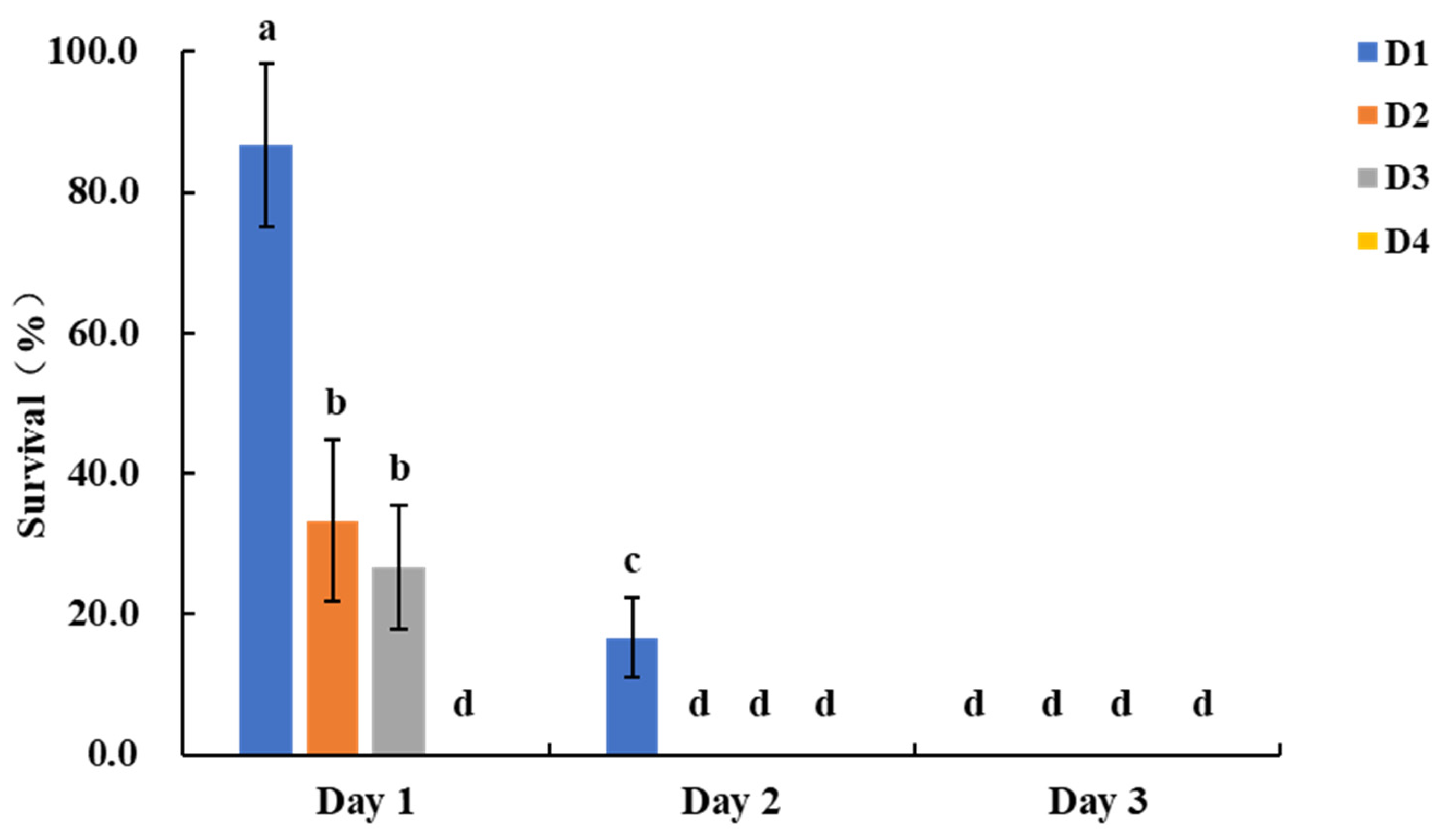

In the silk assay, survival rates for larvae feeding on transgenic maize were as follows: D1 larvae 86.7 ± 11.5%, D2 larvae 33.3 ± 11.5%, D3 larvae 26.7 ± 11.5%, and D4 larvae 0.0 ± 0.0% on day 1 post-infestation. On day 2, survival rates were 16.7 ± 5.8%, 0.0 ± 0.0%, and 0.0 ± 0.0% for D1, D2, and D3 larvae, respectively, with no survivors by day 3 (

Figure 2). Nontransgenic maize silks experienced substantial damage, with large sections consumed and only basal remnants remaining. Transgenic maize silks showed almost no damage, maintaining intact structure (

Figure S2). Based on the shorter test cycle for D2 larvae compared to D3 and D4 larvae, the use of five D2 larvae per assay and assessment on day 2 is recommended for evaluating resistance in transgenic maize silks.

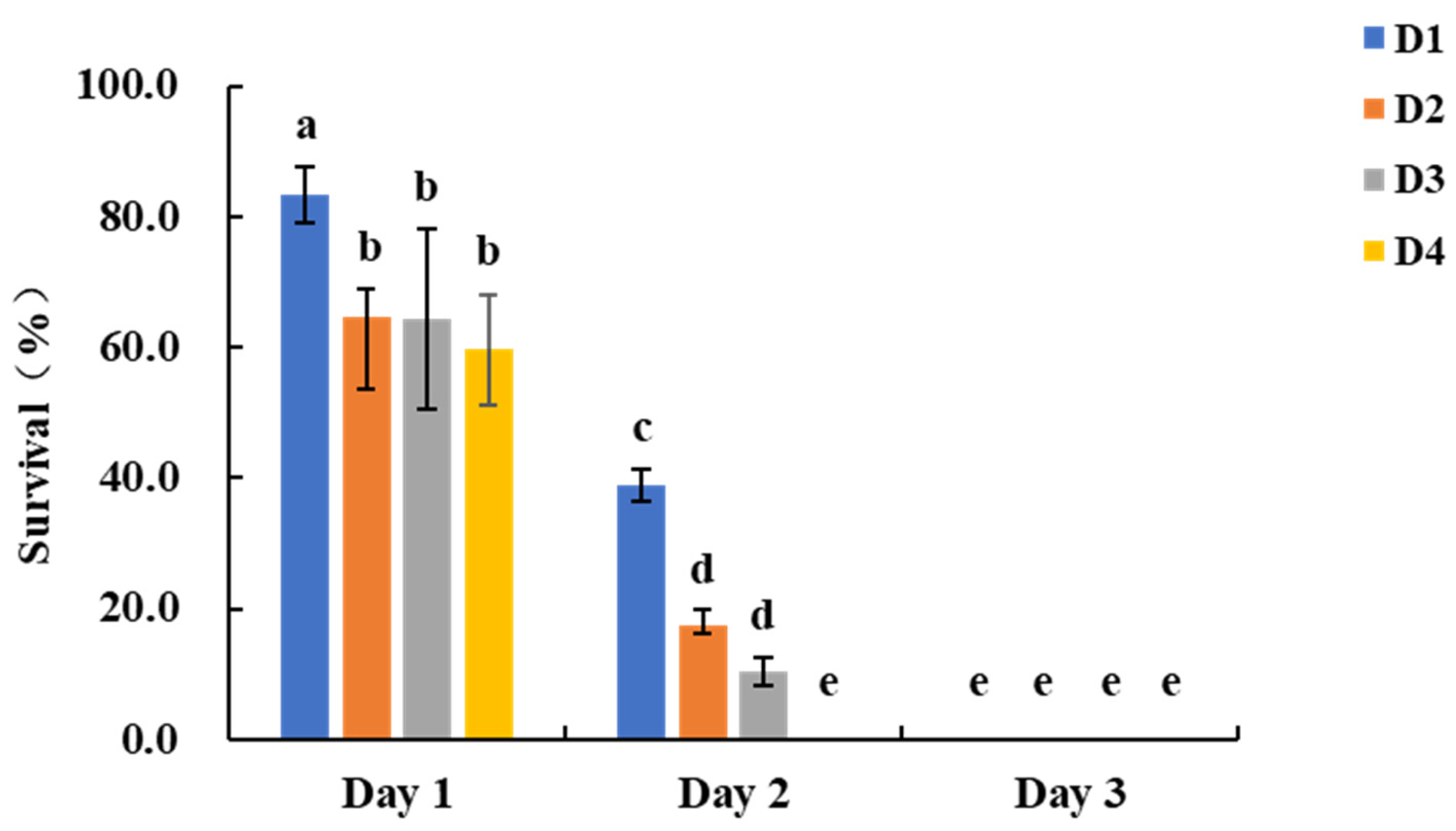

In the kernel assay, survival rates on day 1 post-infestation for larvae feeding on transgenic maize were as follows: D1 larvae 83.3 ± 4.2%, D2 larvae 64.6 ± 11.0%, D3 larvae 64.6 ± 13.7%, and D4 larvae 59.7 ± 8.4%. On day 2, survival rates were 38.9 ± 2.4%, 17.4 ± 1.2%, 10.4 ± 2.1%, and 0.0 ± 0.0% for D1, D2, D3, and D4 larvae, respectively, with no survivors of D1, D2, or D3 larvae by day 3 (

Figure 3). Nontransgenic maize kernels exhibited extensive feeding damage, with large depressions and perforations on the surface. In contrast, transgenic maize kernels showed minimal damage, maintaining nearly intact structures (

Figure S3). Given the shorter assay cycle for D1 larvae compared to D2 and D3 larvae, it is recommended to use two D1 larvae per assay and assess survival on day 3 for resistance evaluation in transgenic maize kernels.

3.2. Screenhouse Potted-Plant Infestation Trials

3.2.1. Optimization of Larval Age for Infestation Protocols

To evaluate the impact of larval age on maize injury, twenty

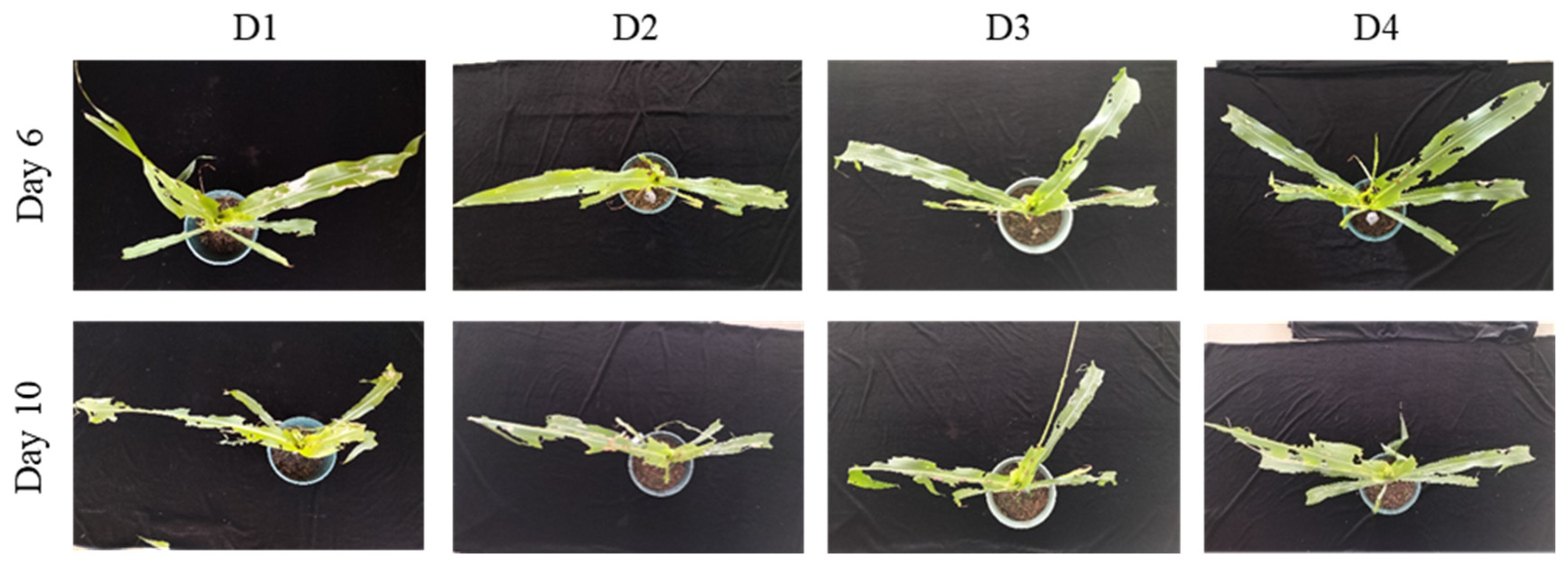

S. frugiperda larvae of ages D1–D4 were inoculated onto maize plants at the whorl stage (4–6 or 8–10 leaves). The number of notched leaves and the type of whorl damage were used as assessment metrics to comprehensive analysis of the differences in harm among different treatments. At the 4–6-leaf stage, on day 6 post-infestation, the mean number of notched leaves was 2.7 ± 0.6 for D1 larvae and 4.6 ± 0.6 for D2 larvae, with a significant difference between the two. No significant differences were observed among the D2, D3, and D4 treatments (

Table 1). In terms of whorl-injury types, D1 larvae caused only minor notching and small perforations in the whorl leaves, whereas D2–D4 larvae produced progressively larger notched areas and all resulted in whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 4). On day 10, the number of notched leaves was 3.7 ± 0.6 for D1 larvae and 5.6 ± 0.6 for D2 larvae, again showing a significant difference, while no significant differences were found among the D2–D4 treatments (

Table 1). At this stage, all larval ages caused severe injury, including extensive notching, with some leaves reduced to only veins (

Figure 4). Overall, considering both the severity of injury and the reliability of results, infestation with D2 larvae and evaluation on day 10 post-infestation is recommended for resistance assessment of transgenic maize. For rapid assessments, evaluation on day 6 can also be used.

At the 8–10-leaf stage, on day 6 post-infestation, the mean number of notched leaves was 3.3 ± 0.6 for D1 larvae and 5.3 ± 0.6 for D2 larvae, with a significant difference between the two; no significant differences were detected among the D2, D3, and D4 treatments (

Table 2). In terms of whorl-injury categories, D1 larvae produced minor notching and some perforations in whorl leaves, while D2–D4 larvae caused substantially greater notching, with whorl leaves often reduced to only veins (

Figure 5). On day 10, the number of notched leaves was 4.7 ± 0.6 for D1 larvae and 7.0 ± 1.0 for D2 larvae, with significant differences between the two, but no significant differences among D2–D4 treatments (

Table 2). At this point, severe damage occurred in all treatments, with large notched areas, some leaves were extensively defoliated, leaving only the midrib intact, and whorl leaves often broken (

Figure 5). Accordingly, infestation with D2 larvae and evaluation on day 10 post-infestation is recommended for resistance assessment in transgenic maize. For rapid evaluations, assessment on day 6 may also be used.

3.2.2. Optimization of Larval Density for Infestation Protocols

To investigate the effects of different densities of

S. frugiperda on maize injury, larvae of age D2 were inoculated onto maize plants at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves) at densities of 10, 20, 30, or 40 larvae per plant. The number of notched leaves and the type of whorl damage were used as assessment metrics to analyze the differences in maize injury across treatments. On day 6 post-infestation, the mean number of notched leaves was 2.3 ± 0.6 for the 10 larvae treatment and 3.7 ± 0.6 for the 20 larvae treatment, with a significant difference between the two. No significant differences were observed among the 20, 30, and 40 larvae treatments (

Table 3). In terms of whorl-injury types, the 10 larvae treatment caused only minor notching, with slight feeding on the whorl leaves and small perforations. The 20 larvae treatment resulted in a significant increase in notched leaves, with more extensive feeding and larger perforations in the whorl leaves. The 30 larvae treatment caused more severe damage, with increased notching and extensive feeding in the whorl. The 40 larvae treatment led to the most severe damage, with many notched leaves and whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 6). On day 10 post-infestation, the number of notched leaves was 3.3 ± 0.6 for the 10 larvae treatment and 5.3 ± 0.6 for the 20 larvae treatment, with a significant difference between the two. No significant differences were found among the 20, 30, and 40 larvae treatments (

Table 3). In terms of whorl injury, all treatments caused severe damage, with extensive notching and large areas of feeding, leaving only the midrib in some leaves. Whorl-leaf breakage was observed in all treatments, and the extent of damage increased with larval density (

Figure 6). Considering both the severity of damage and the reliability of the results, infestation with 20 D2 larvae per plant and evaluation on day 10 post-infestation is recommended for resistance evaluation in transgenic maize. For rapid assessments, evaluation on day 6 can also be used.

3.3. Field Infestation Trials for Assessing Transgenic Maize Resistance to S. frugiperda

3.3.1. Comparison of Different Larval Ages for Infestation Protocols

To explore the effects of different larval ages of

S. frugiperda on maize injury, twenty larvae of age D1–D4 were inoculated onto maize plants at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves or 8–10 leaves). The number of notched leaves and the type of whorl damage were used as assessment metrics to analyze the differences in maize injury across treatments. At the 4–6-leaf stage, on day 7 post-infestation, the mean number of notched leaves was 0.3 ± 0.6 for the D1 larvae treatment, 2.0 ± 0.0 for the D2 larvae treatment, and 3.0 ± 0.0 for D3 larvae, with significant differences between D1 and D2, and D1 and D3 treatments. No significant differences were observed between the D3 and D4 treatments (

Table 4). In terms of whorl-injury types, the D1 and D2 larvae treatments caused light damage, with small notches and slight perforations in the whorl leaves. The D3 and D4 treatments caused progressively more extensive damage, with increased notching and larger perforations in the whorl, resulting in whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 7). By day 12, the number of notched leaves was 2.7 ± 0.6 for D2 larvae and 4.6 ± 0.6 for D3 larvae, with a significant difference between the two, while no significant differences were observed between D1 and D2, or D3 and D4 treatments (

Table 4). Whorl damage also increased significantly, with the D1 and D2 treatments showing more notching and slight perforations, while D3 and D4 treatments caused severe notching, large holes, and whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 7).

At the 8–10-leaf stage, on day 7 post-infestation, the mean number of notched leaves for the D1, D2, D3, and D4 larvae treatments was 0.0 ± 0.0, 1.6 ± 0.6, 3.7 ± 0.6, and 4.7 ± 0.6, respectively, with significant differences observed between all treatments (

Table 5). In terms of whorl-injury types, the D1 larvae treatment showed mostly “windows” (tissue loss without notching), while the D2 larvae treatment exhibited both “windows” and some notching. The D3 larvae treatment caused slight notching, with feeding on the whorl leaves and small holes, while the D4 larvae treatment caused severe notching, large holes, and complete whorl-leaf breakage, leaving only veins (

Figure 8). On day 12, the number of notched leaves was 3.3 ± 0.6 for the D1 larvae treatment, 4.0 ± 0.0 for D2 larvae, 5.3 ± 0.0 for D3 larvae, and 5.6 ± 0.6 for D4 larvae, with no significant differences observed between D1 and D2, or D3 and D4 treatments, but with a significant difference between D2 and D3 treatments (

Table 5). Whorl damage further increased, with the D1 treatment showing mild damage, the D2 treatment showing further notching and larger holes, and the D3 and D4 treatments causing severe damage, including large notches and whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 8). Considering both the severity of injury and the reliability of the results, infestation with D3 larvae and evaluation on day 12 post-infestation is recommended for resistance assessment in transgenic maize. For rapid evaluations, assessment on day 7 can also be used.

3.3.2. Optimization of Larval Density for Infestation Protocols

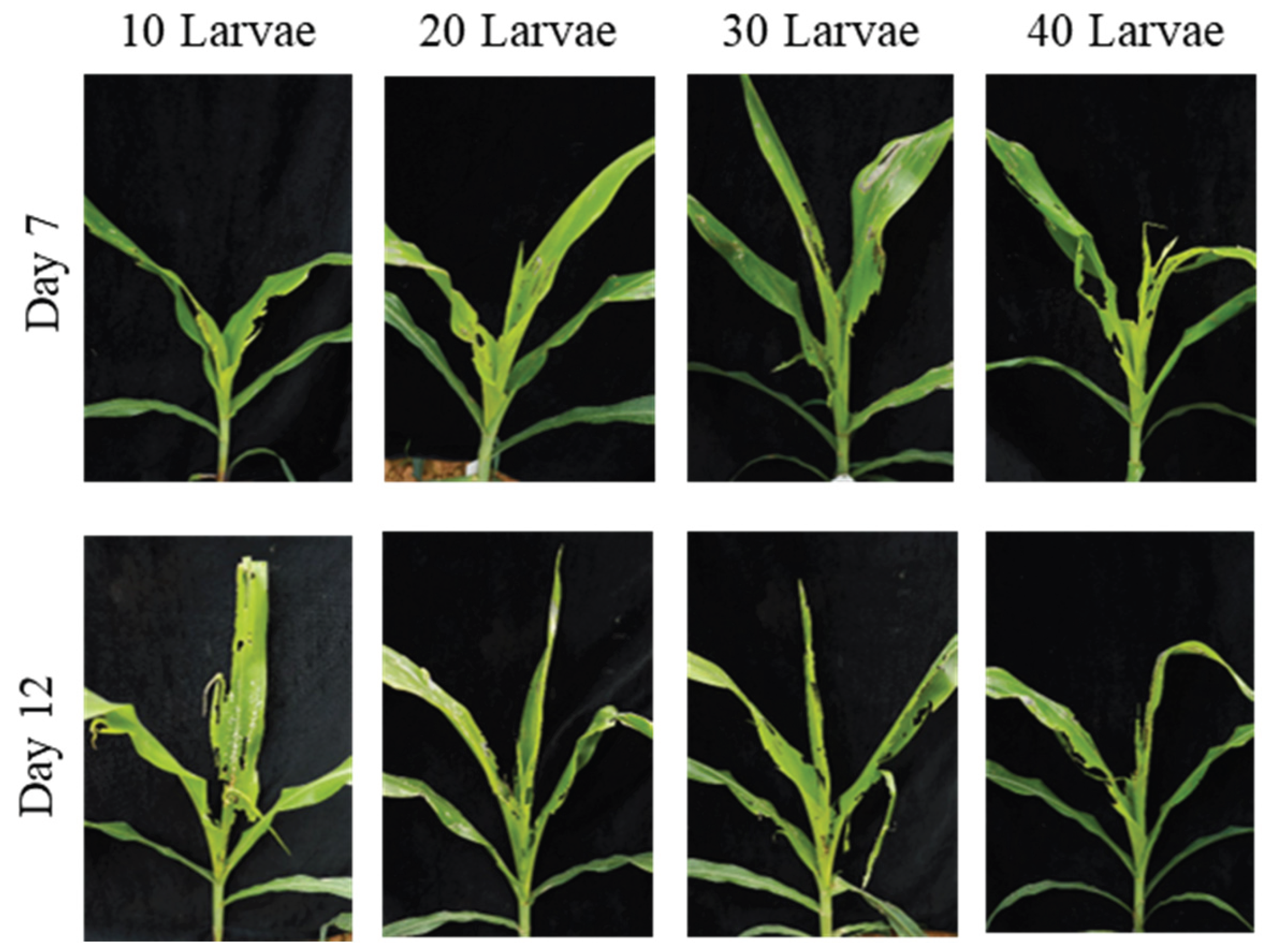

To explore the effects of different densities of

S. frugiperda on maize injury, larvae of age D3 were inoculated onto maize plants at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves) at densities of 10, 20, 30, or 40 larvae per plant. The number of notched leaves and the type of whorl damage were used as assessment metrics to analyze the differences in maize injury across treatments. On day 7 post-infestation, the mean number of notched leaves was 2.0 ± 0.0 for the 20 larvae treatment and 3.7 ± 0.6 for the 30 larvae treatment, with a significant difference between the two. No significant differences were observed between the 10 larvae and 20 larvae treatments, or between the 30 larvae and 40 larvae treatments (

Table 6). In terms of whorl-injury types, the 10 larvae treatment caused minor notching, with slight feeding on the whorl leaves and small perforations. The 20 larvae treatment showed an increase in the area of leaf notching, with the whorl leaves exhibiting more extensive feeding and larger perforations. The 30 larvae treatment caused more severe damage, with increased notching and extensive feeding in the whorl. The 40 larvae treatment led to the most severe damage, with many notched leaves and whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 9). On day 12, the number of notched leaves was 3.3 ± 0.6 for the 20 larvae treatment and 5.0 ± 0.0 for the 30 larvae treatment, with a significant difference between the two. No significant differences were found between the 10 larvae and 20 larvae treatments, or between the 30 larvae and 40 larvae treatments (

Table 6). In terms of whorl damage, the 10 larvae treatment caused an increase in the number of notched leaves and more extensive feeding, with some leaves showing large notches and whorl-leaf breakage. The 20, 30, and 40 larvae treatments resulted in severe damage, with large notches on the leaves and extensive feeding, leading to whorl-leaf breakage (

Figure 9). Considering both the severity of injury and the reliability of the results, infestation with 30 D3 larvae per plant and evaluation on day 12 post-infestation is recommended for resistance evaluation in transgenic maize. For rapid evaluations, assessment on day 7 can also be used.

4. Discussion

The fall armyworm (

S. frugiperda) is a globally significant agricultural pest native to the tropical and subtropical Americas. Research on transgenic maize resistance to

S. frugiperda has made notable progress. For instance, Abel et al. [

17] evaluated the resistance of eight maize genotypes native to Ecuador through field planting and artificial inoculation, identifying four genotypes with moderate resistance. Moscardini et al. [

18] assessed the resistance of six Bt maize lines to

S. frugiperda through field trials and found that Bt maize expressing the Cry1F, Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, and Vip3Aa20 proteins exhibited high resistance to the pest. However, these studies did not standardize the larval age and density for infestation, which may have affected the experimental outcomes and led to longer testing periods. In contrast, the infestation protocol proposed in this study clarifies specific operational parameters. In screenhouse conditions, the protocol recommends the use of 20 D2 larvae per maize plant, with leaf injury evaluated on day 10 post-infestation. In field conditions, it suggests using 30 D3 larvae per plant, with leaf injury evaluated on day 12 post-infestation. This protocol allows for stable and reliable data within 10–12 days, significantly improving evaluation efficiency and reducing experimental costs, including labor and transportation for field access, diet and manpower for insect rearing, etc. Moreover, this method is not only applicable to

S. frugiperda resistance studies but can also serve as a reference for research on infestation techniques for other lepidopteran pests, such as the Asian corn borer (

O. furnacalis) and cotton bollworm (

H. armigera).

During the study, it was observed that, compared to screenhouse trials, a higher larval density and longer infestation period were required in the field to achieve the same level of maize injury. This difference is primarily due to environmental factors: the screenhouse environment is more controlled, providing optimal conditions for

S. frugiperda growth and development while limiting the interference of natural enemies. In contrast, field conditions are more influenced by natural climate factors (such as diurnal temperature variations, rainfall, and wind), which may reduce larval activity and delay feeding processes [

19,

20]. Additionally, field trials are exposed to natural enemies like stink bugs, ladybirds, and various parasitoid wasps, which may limit the movement of

S. frugiperda larvae and affect the resistance evaluation [

21,

22,

23]. Therefore, when assessing the resistance of transgenic maize to

S. frugiperda, it is essential to consider the differences between screenhouse and field environments in relation to the study objectives, in order to devise accurate pest control strategies.

While the infestation method established in this study is highly efficient, it still has certain limitations. First, the experiment focused on only two maize varieties, and different maize varieties with varying nutritional components and leaf morphological traits may significantly influence larval feeding behavior [

24,

25]. Second, the field trials were conducted exclusively in South China, and the natural conditions in this region differ from those in Southwest China, the lower and middle Yangtze River, and areas with different altitudes, which may affect the generalizability of the method. Despite these limitations, this study provides a relatively accurate and specific method for evaluating the damage caused by

S. frugiperda to maize, offering valuable insights for resistance assessments of transgenic maize both indoors and in the field. It also provides important guidance for the development of standardized infestation protocols for

S. frugiperda.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.J., C.W. and W.C.; data curation, C.W. and W.C.; formal analysis, C.W., W.C. and G.H.; funding acquisition, D.J.; investigation, C.W., W.C., X.G., G.H., G.Y. and L.Z.; methodology, C.W. and W.C.; project administration, D.J.; resources, J.Y. and D.J.; supervision, D.J.; validation, C.W. and W.C.; visualization, C.W., W.C. and X.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, W.C., X.G., G.H., G.Y., L.Z., J.Y. and D.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Biological Breeding-Major Projects (2023ZD04062).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Biological Breeding-Major Projects (2023ZD04062) for its financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Montezano, D.G.; Sosa-Gomez, D.R.; Specht, A.; Roque-Specht, V.F.; Sousa-Silva, J.C.; Paula-Moraes, S.V.; Peterson, J.A.; Hunt, T.E. Host plants of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas. Afr. Entomol. 2018, 26, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, M. Prospects for classical biological control of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in invaded areas using parasitoids from the Americas. J. Econ. Entomol. 2023, 116, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.X.; Hu, C.X.; Jia, H.R.; Wu, Q.L.; Shen, X.J.; Zhao, S.Y.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Wu, K.M. Case study on the first immigration of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda invading into China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Q.L.; Zhang, H.W.; Wu, K.M. Spread of invasive migratory pest Spodoptera frugiperda and management practices throughout China. J Int Agri 2021, 20, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntin, G.D.; All, J.N.; Lee, R.D.; Wilson, D.M. Plant-incorporated Bacillus thuringiensis resistance for control of fall armyworm and corn earworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in corn. J. Econ. Entomol. 2004, 97, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.H.; Santos, A.C.; Castro, B.A.; Moscardini, V.F.; Rosseto, J.; Silva, O.A.B.N.; Babcock, J.M. Assessing the Efficacy of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Pyramided Proteins Cry1F, Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, and Vip3Aa20 Expressed in Bt Maize Against Lepidopteran Pests in Brazil. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntin, G.D. Corn expressing Cry1Ab or Cry1F endotoxin for fall armyworm and corn earworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) management in field corn for grain production. Fla. Entomol. 2008, 91, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, M.W.; Nolting, S.P.; Hendrix, W.; Dhavala, S.; Craig, C.; Leonard, B.R.; Stewart, S.D.; All, J.; Musser, F.R.; Buntin, G.D.; et al. Evaluation of corn hybrids expressing Cry1F, Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1, and Cry3Bb1 against southern United States insect pests. J. Econ. Entomol. 2012, 105, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasena, D.I.; Signorini, A.M.; Abratti, G.; Storer, N.P.; Olaciregui, M.L.; Alves, A.P.; Pilcher, C.D. Characterization of field-evolved resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis-derived Cry1F δ -endotoxin in Spodoptera frugiperda populations from Argentina. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.M.; Zhao, S.Y.; Liu, B.; Gao, Y.; Hu, C.X.; Li, W.J.; Yang, Y.Z.; Li, G.P.; Wang, L.L.; Yang, X.Q.; et al. Bt maize can provide non-chemical pest control and enhance food safety in China. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Chalarca, J.; Valencia, S.J.; Rivas-Cano, A.; Santos-González, F.; Romero, D.P. Impact of Bt corn expressing Bacillus thuringiensis Berliner insecticidal proteins on the growth and survival of Spodoptera frugiperda larvae in Colombia. Front. Insect Sci. 2024, 4, 1268092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.Y.; Yang, X.M.; Liu, D.Z.; Sun, X.X.; Li, G.P.; Wu, K.M. Performance of the domestic Bt corn event expressing pyramided Cry1Ab and Vip3Aa19 against the invasive Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) in China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, V.A.; Villalba, G.E.; Arias, O.R.; Ramirez, M.B.; Gaona, E.F. Toxicity of the Bt protein expressed in leaves of different events of transgenic corn released in Paraguay against Spodoptera frugiperda (Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 2017, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, A.S.; Erasmus, A.; du Plessis, H.; Van den Berg, J. Efficacy of Bt maize for control of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in South Africa. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.P.; Buckley, P.M.; Davis, F.M. Combining ability for resistance in corn to fall armyworm and to southwestern corn-borer. Crop Sci. 1989, 29, 913–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfer, S.; Fallet, P.; Kajuga, J.; Bazagwira, D.; Mukundwa, I.P.; Szalai, M.; Turlings, T.C.J. Streamlining leaf damage rating scales for the fall armyworm on maize. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 1075–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, C.A.; Coates, B.S. Evaluation of eight maize germplasms developed in Ecuador for resistance to leaf-feeding fall armyworm. Southwest. Entomol. 2020, 45, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardini, V.F.; Marques, L.H.; Santos, A.C.; Rossetto, J.; Silva, O.A.B.N.; Rampazzo, P.E.; Castro, B.A. Efficacy of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) maize expressing Cry1F, Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2 and Vip3Aa20 proteins to manage the fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Brazil. Crop Prot. 2020, 137, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Xie, W.Q.; Wang, R.L.; Feng, C.H.; Ma, L.; Li, Q.; Yang, Q.F.; Wang, H.J. Predicting the potential distribution of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) under climate change in China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 33, e01994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.C.; Chi, H.P.; Shi, M.Y.; Lu, Z.Z.; Zalucki, M.P. Night warming has mixed effects on the development of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in Southern China. Insects 2024, 15, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenis, M.; Benelli, G.; Biondi, A.; Calatayud, P.; Day, R.; Desneux, N.; Harrison, R. D.; Kriticos, D.; Rwomushana, I.; van den Berg, J.; et al. Invasiveness, biology, ecology, and management of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 187–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyckhuys, K.A.G.; Akutse, K.S.; Amalin, D.M.; Araj, S.E.; Barrera, G.; Beltran, M.J.B.; Ben Fekih, I.; Calatayud, P.A.; Cicero, L.; Cokola, M.C.; et al. Global scientific progress and shortfalls in biological control of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. Biol. Control 2024, 191, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Kong, W.Z.; Ran, X.T.; Lv, X.L.; Ma, C.J.; Yan, H. Biological and physiological changes in Spodoptera frugiperda larvae induced by non-consumptive effects of the predator Harmonia axyridis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.G.; Ni, X.Z.; Buntin, G.D. Physiological, nutritional, and biochemical bases of corn resistance to foliage-feeding fall armyworm. J. Chem. Ecol. 2009, 35, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.F.C.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Andueza-Noh, R.H.; Garruña-Hernández, R.; Latournerie-Moreno, L.; Mijangos-Cortés, J.O. Leaf damage by Spodoptera frugiperda J. E. Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and its relation to leaf morphological traits in maize landraces and commercial cultivars. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2020, 127, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Survival rates of S. frugiperda larvae of different ages after feeding on transgenic maize whorl leaves. Bars with different lowercase letters above them indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test). D1–D4 represent days 1–4 post-hatching.

Figure 1.

Survival rates of S. frugiperda larvae of different ages after feeding on transgenic maize whorl leaves. Bars with different lowercase letters above them indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test). D1–D4 represent days 1–4 post-hatching.

Figure 2.

Survival rates of S. frugiperda larvae of different ages after feeding on transgenic maize silks. Bars with different lowercase letters above them indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test).

Figure 2.

Survival rates of S. frugiperda larvae of different ages after feeding on transgenic maize silks. Bars with different lowercase letters above them indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test).

Figure 3.

Survival rates of S. frugiperda larvae of different ages after feeding on transgenic maize kernels. Bars with different lowercase letters above them indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test).

Figure 3.

Survival rates of S. frugiperda larvae of different ages after feeding on transgenic maize kernels. Bars with different lowercase letters above them indicate significant differences between treatments (P < 0.05, Tukey’s test).

Figure 4.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves). This figure shows the damage to maize at the whorl stage caused by larvae of different ages (1–4 days) on days 6 and 10 post-infestation. The amount of leaf notching and the condition of the whorl leaf are shown, with increasing damage observed as larval age increases.

Figure 4.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves). This figure shows the damage to maize at the whorl stage caused by larvae of different ages (1–4 days) on days 6 and 10 post-infestation. The amount of leaf notching and the condition of the whorl leaf are shown, with increasing damage observed as larval age increases.

Figure 5.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves). This figure shows the damage to maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves) caused by larvae of different ages on days 6 and 10 post-infestation. The increasing damage as larval age increases is visually represented.

Figure 5.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves). This figure shows the damage to maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves) caused by larvae of different ages on days 6 and 10 post-infestation. The increasing damage as larval age increases is visually represented.

Figure 6.

Damage caused by different numbers of 2-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves). This figure shows how different numbers of 2-day-old larvae (10, 20, 30, 40 larvae per plant) affect maize at the whorl stage. Damage increases with higher larval density, with more extensive leaf notching and whorl-leaf breakage as the larval density increases.

Figure 6.

Damage caused by different numbers of 2-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves). This figure shows how different numbers of 2-day-old larvae (10, 20, 30, 40 larvae per plant) affect maize at the whorl stage. Damage increases with higher larval density, with more extensive leaf notching and whorl-leaf breakage as the larval density increases.

Figure 7.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves) in field conditions. This figure illustrates the damage caused by larvae of different ages (1–4 days) on maize in the field. On day 7 and day 12 post-infestation, the damage increases with larval age, showing notching and perforations, with whorl-leaf breakage in more mature larvae.

Figure 7.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves) in field conditions. This figure illustrates the damage caused by larvae of different ages (1–4 days) on maize in the field. On day 7 and day 12 post-infestation, the damage increases with larval age, showing notching and perforations, with whorl-leaf breakage in more mature larvae.

Figure 8.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves) in field conditions. This figure shows the damage caused by larvae of different ages (1–4 days) on maize at the 8–10 leaf stage in field conditions. The damage increases over time, with more notching and whorl-leaf breakage as larval age increases.

Figure 8.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves) in field conditions. This figure shows the damage caused by larvae of different ages (1–4 days) on maize at the 8–10 leaf stage in field conditions. The damage increases over time, with more notching and whorl-leaf breakage as larval age increases.

Figure 9.

Damage caused by different numbers of 3-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves) in field conditions. This figure shows the damage caused by different numbers of 3-day-old larvae (10, 20, 30, 40 larvae per plant) on maize at the whorl stage. The damage increases with the number of larvae, showing more notching and extensive feeding as the density increases.

Figure 9.

Damage caused by different numbers of 3-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves) in field conditions. This figure shows the damage caused by different numbers of 3-day-old larvae (10, 20, 30, 40 larvae per plant) on maize at the whorl stage. The damage increases with the number of larvae, showing more notching and extensive feeding as the density increases.

Table 1.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

Table 1.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

| Larval Age |

Day 6 |

Day 10 |

| Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

| D1 |

2.7 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

3.7 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D2 |

4.6 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

5.6 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D3 |

5.0 ± 1.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

6.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D4 |

5.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

6.6 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

Table 2.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves).

Table 2.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves).

| Larval Age |

Day 6 |

Day 10 |

| Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

| D1 |

3.3 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

4.7 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D2 |

5.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

7.0 ± 1.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D3 |

6.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

7.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D4 |

6.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

8.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

Table 3.

Damage caused by different numbers of 2-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

Table 3.

Damage caused by different numbers of 2-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

| Number of Larvae |

Day 6 |

Day 10 |

| Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

| 10 |

2.3 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

3.3 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| 20 |

3.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten |

5.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| 30 |

4.0 ± 0.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten |

5.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| 40 |

4.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

6.0 ± 1.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

Table 4.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

Table 4.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

| Larval Age |

Day 7 |

Day 12 |

| Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

| D1 |

0.3 ± 0.6 c |

Windows/Notching |

2.3 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

| D2 |

2.0 ± 0.0 b |

Windows/Notching |

2.7 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D3 |

3.0 ± 0.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten |

4.6 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D4 |

3.3 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten |

5.0 ± 1.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

Table 5.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves).

Table 5.

Damage caused by S. frugiperda larvae of different ages on maize at the whorl stage (8–10 leaves).

| Larval Age |

Day 7 |

Day 12 |

| Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

| D1 |

0.0 ± 0.0 d |

Windows |

3.3 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

| D2 |

1.6 ± 0.6 c |

Windows/Notching |

4.0 ± 0.0 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D3 |

3.7 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

5.3 ± 0.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| D4 |

4.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

5.6 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

Table 6.

Damage caused by different numbers of 3-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

Table 6.

Damage caused by different numbers of 3-day-old S. frugiperda larvae on maize at the whorl stage (4–6 leaves).

| Number of Larvae |

Day 7 |

Day 12 |

| Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

Number of Notched Leaves |

Whorl Injury Type |

| 10 |

1.7 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

3.0 ± 0.0 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| 20 |

2.0 ± 0.0 b |

Whorl leaf eaten |

3.3 ± 0.6 b |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| 30 |

3.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten/ eaten to breakage |

5.0 ± 0.0 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

| 40 |

3.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten/ eaten to breakage |

5.7 ± 0.6 a |

Whorl leaf eaten to breakage |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).