Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

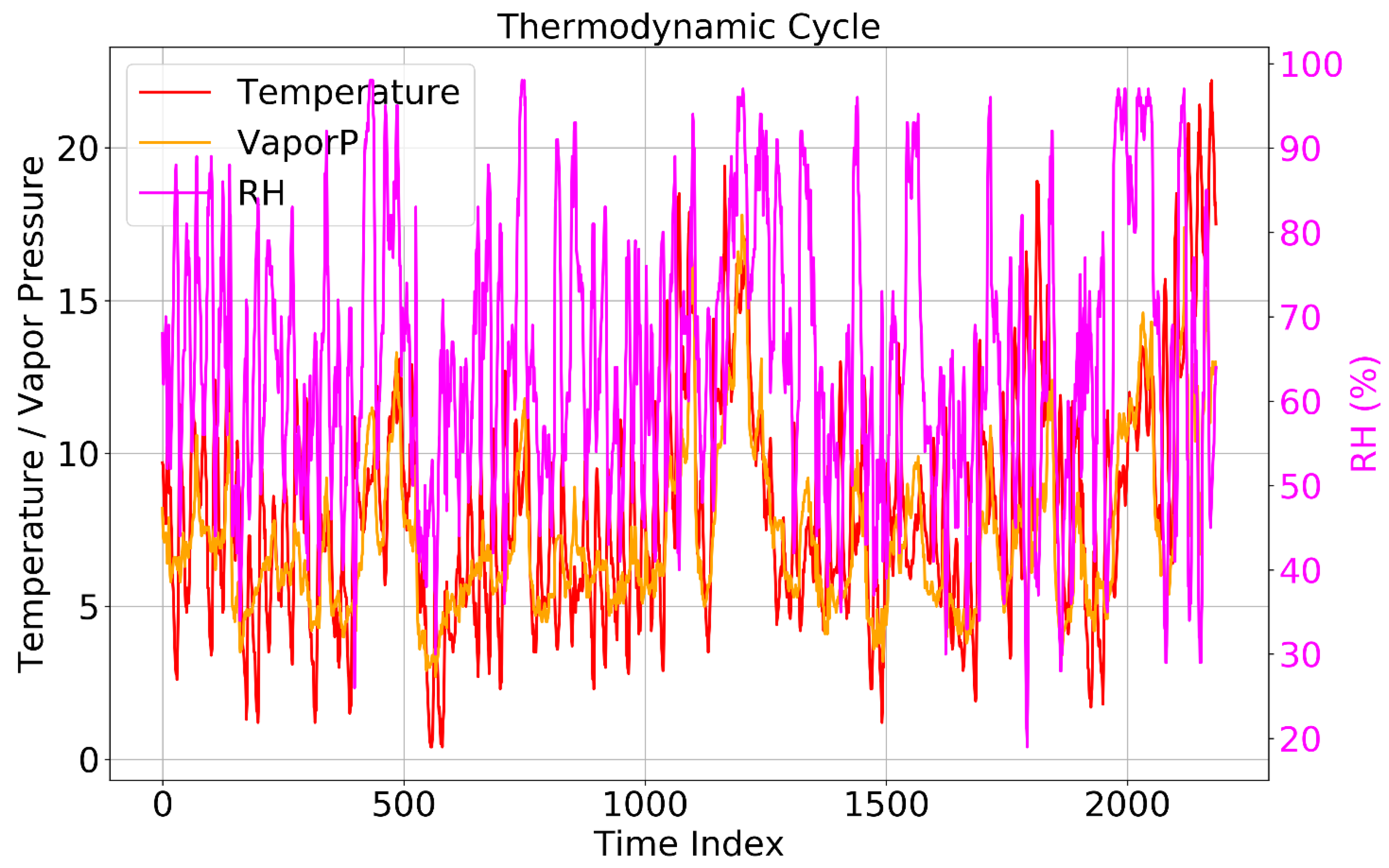

3.1. Thermodynamic Variability

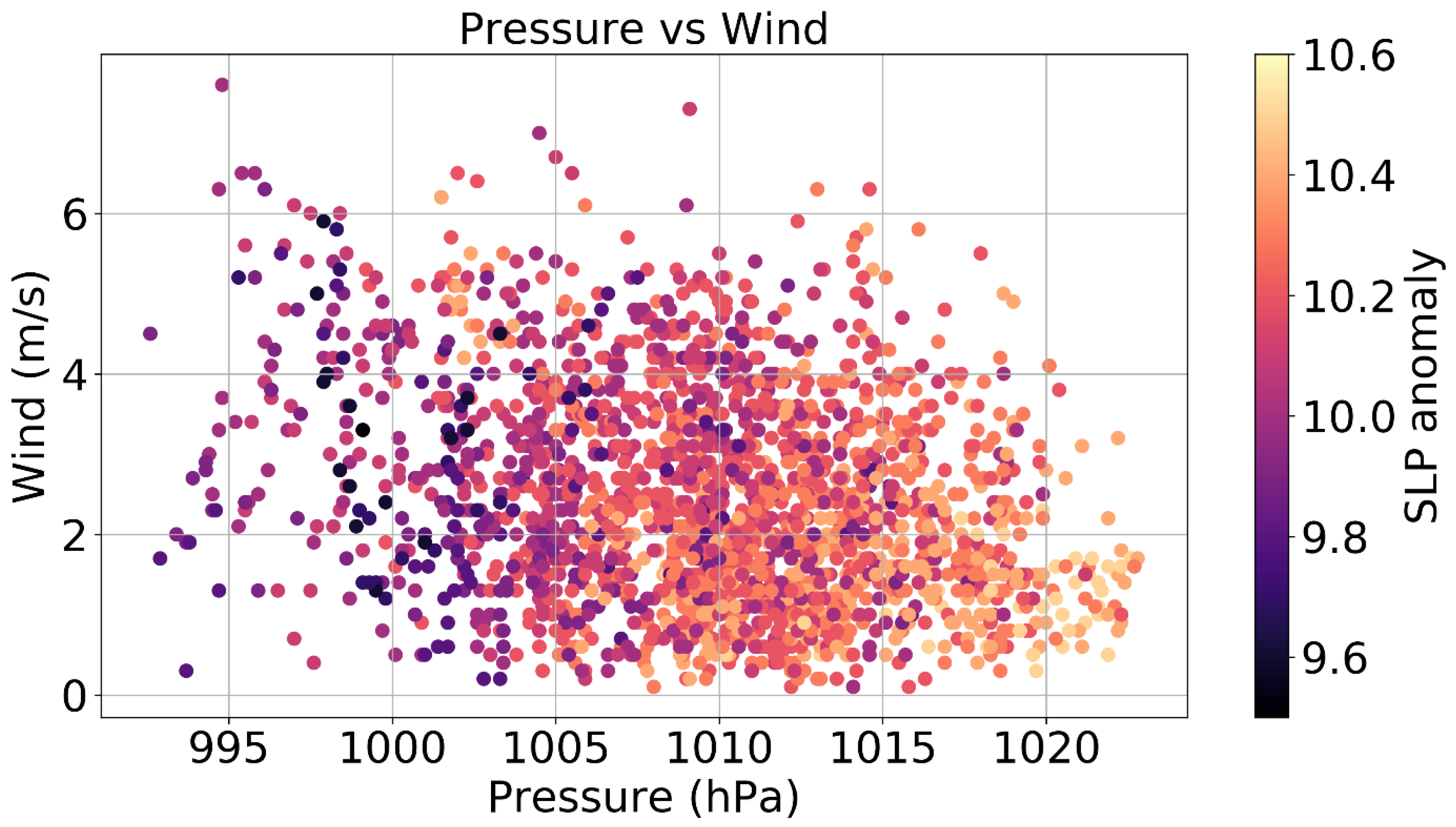

3.2. Dynamical Coupling

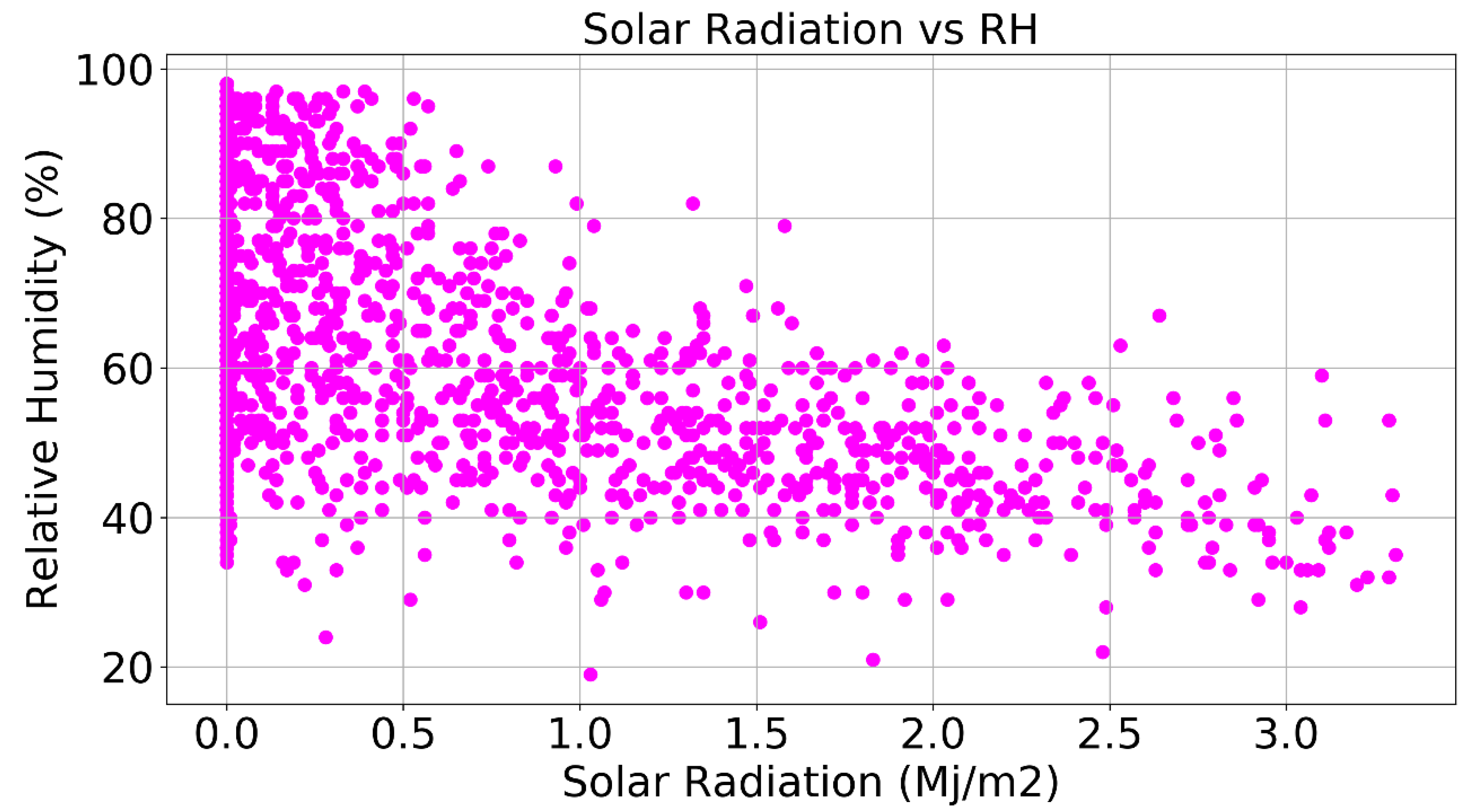

3.3. Radiative–Moisture Interaction

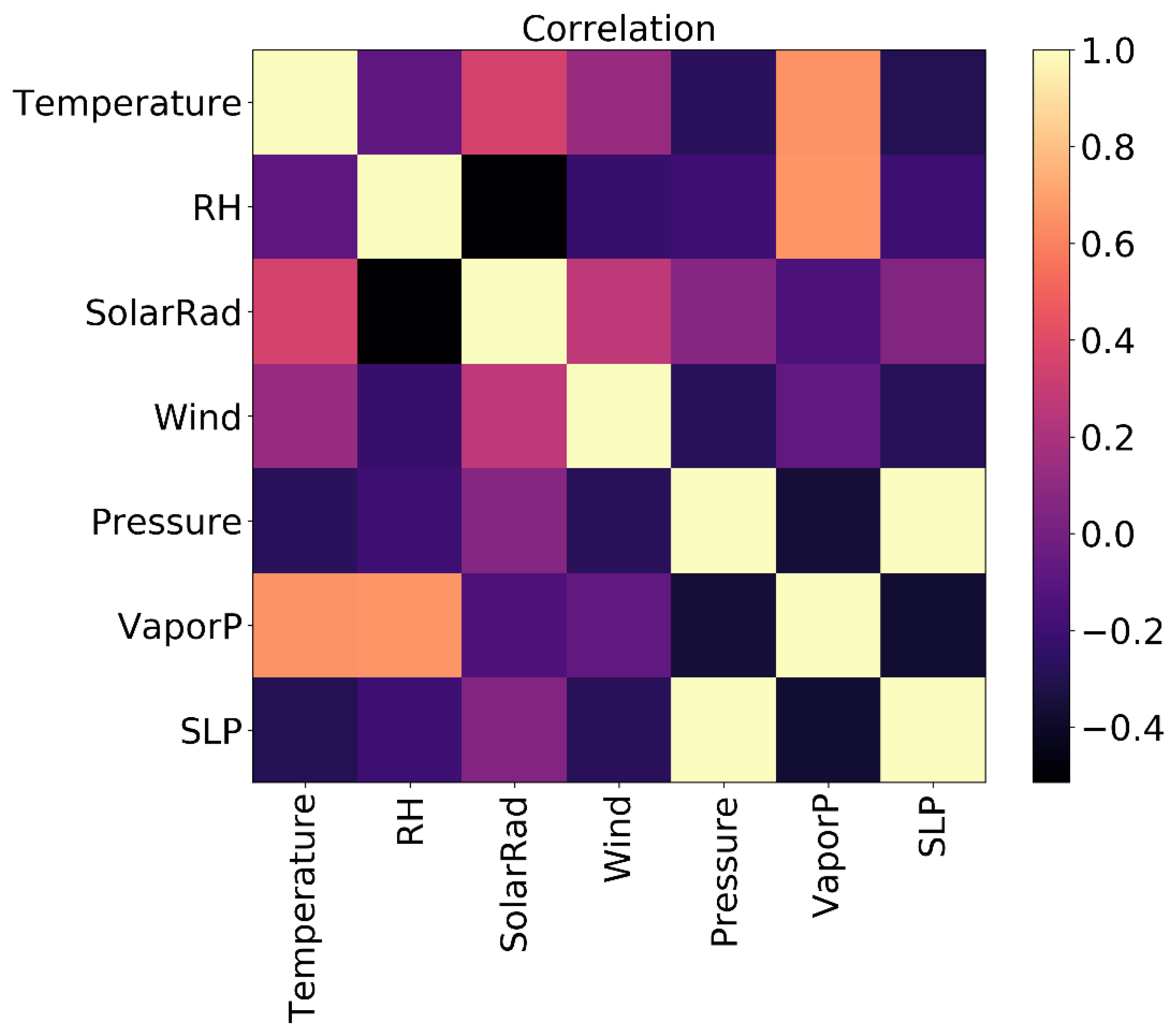

3.4. Multivariate Atmospheric Relationships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Dabral, A., Shankhwar, R., Martins-Ferreira, M. A. C., Pandey, S., Kant, R., Meena, R. K., Chandra, G., Ginwal, H. S., Thakur, P. K., Bhandari, M. S., Sahu, N., & Nayak, S. (2023). Phenotypic, geological, and climatic spatio-temporal analyses of an exotic Grevillea robusta in the Northwestern Himalayas. Sustainability, 15(15), 12292. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. (2023). Exploring the future rainfall characteristics over India from large ensemble global warming experiments. Climate, 11(5), 94. [CrossRef]

- Zwiers, F. W., Alexander, L. V., Hegerl, G. C., Knutson, T. R., Kossin, J. P., Naveau, P.,... & Zhang, X. (2013). Climate extremes: challenges in estimating and understanding recent changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme climate and weather events. Climate science for serving society: research, modeling and prediction priorities, 339-389.

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2022). Assessing the impact of climate change on temperature and precipitation over India. In T. Sumi et al., (Eds.), Wadi Flash Floods, Natural Disaster Science and Mitigation Engineering: DPRI Reports (pp. 121-142). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2024). Climate change scenario over Japan: trends and impacts. In Khare (Ed.), The Role of Tropics in Climate Change (pp. 145-169), Elsevier Inc.

- Clarke, B., Otto, F., Stuart-Smith, R., & Harrington, L. (2022). Extreme weather impacts of climate change: an attribution perspective. Environmental Research: Climate, 1(1), 012001. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Takemi, T., & Maity, S. (2022). Precipitation and temperature climatologies over India: A study with AGCM large ensemble climate simulations. Atmosphere, 13(5), 671. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., Nayak, S., Bhattacharyya, I., Saha, S., Mandal, A. K., Chakraborty, S., Bhattacharyya, R., Chakraborty, R., Franco, O. L., Mandal, S. M., & Basak, A. (2014). Understanding the patterns of antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria causing urinary tract infection in West Bengal, India. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5, 463. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, N., Panda, A., Nayak, S., Saini, A., Mishra, M., Sayama, T., Sahu, L., Duan, W., Avtar, R., Behera, S. (2020). Impact of Indo-Pacific Climate Variability on High Streamflow Events in Mahanadi River Basin, India. Water, 12(7), 1952. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, N., Saini, A., Behera, S., Sayama, T., Nayak, S., Sahu, L., Duan, W., Avtar, R., Yamada, M., Singh, R.B., Takara, K. (2020). Impact of Indo-Pacific Climate Variability on Rice Productivity in Bihar, India. Sustainability, 12(17), 7023. [CrossRef]

- Saini, A., Sahu, N., Kumar, P., Nayak, S., Duan, W., Avtar, R., Behera, S. (2020). Advanced Rainfall Trend Analysis of 117 Years over West Coast Plain and Hill Agro-Climatic Region of India. Atmosphere, 11(11), 1225. [CrossRef]

- Saini, A., Sahu, N., & Nayak, S. (2023). Determination of Grid-Wise Monsoon Onset and Its Spatial Analysis for India (1901–2019). Atmosphere, 14(9), 1424. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, N., Jayal, T., Singh, M., Mandwal, V., Saini, A., Nirbhav, Sahu, N., & Nayak, S. (2022). Evaluation of Observed and Future Climate Change Projection for Uttarakhand, India, Using CORDEX-SA. Atmosphere, 13(947). [CrossRef]

- Sahu, N., Nayan, R., Panda, A., Varun, A., Kesharwani, R., Das, P., Kumar, A., Mallick, S.K., Mishra, M.M., Saini, A., Aggarwal, S.P., Nayak, S. (2025). Impact of Changes in Rainfall and Temperature on Production of Darjeeling Tea in India. Atmosphere, 16(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, J., Aiba, M., Furukawa, F., Mishima, Y., Yoshimura, N., Nayak, S., Takemi, T., Haga, C., Matsui, T., & Nakamura, F. (2021). Risk assessment of forest disturbance by typhoons with heavy precipitation in northern Japan. Forest Ecology and Management, 479, 118521. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. (2018). Do extreme precipitation intensities linked to temperature over India follow the Clausius–Clapeyron relationship? Current Science, 115(3), 391-392. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Dairaku, K. (2016). Future changes in extreme precipitation intensities associated with temperature under SRES A1B scenario. Hydrological Research Letters, 10(4), 139–144. [CrossRef]

- Sayat, A., Lyazzat, M., Elmira, T., Gaukhar, B., & Gulsara, M. (2024). Assessment of the impacts of climate change on drought intensity and frequency using SPI and SPEI in the Southern Pre-Balkash region, Kazakhstan. Watershed Ecology and the Environment. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Mandal, M. (2019). Assessment of sea level and morphological changes along Indian coastal areas during 1975-2005. Earth Science India, 12(II), 117-125.

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2019). Dependence of extreme precipitable water events on temperature. Atmósfera, 32(2), 159-165. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M. T., & Piracha, A. (2021). Natural disasters—origins, impacts, management. Encyclopedia, 1(4), 1101-1131. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2020). Clausius-Clapeyron scaling of extremely heavy precipitations: Case studies of the July 2017 and July 2018 heavy rainfall events over Japan. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, 98(6), 1147–1162. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2021). Atmospheric driving mechanisms of extreme precipitation events in July of 2017 and 2018 in western Japan. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 93, 101186. [CrossRef]

- Rajkovich, N. B., Brown, C., Azaroff, I., Backus, E., Clarke, S., Enriquez, J.,... & Stevens, A. (2024). New York State Climate Impacts Assessment Chapter 04: Buildings. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Mandal, M., Adhikari, A., & Bhatla, R. (2013). Estimation of Indian coastal areas inundated into the sea due to sea-level rise during the 20th century. Current Science, 104(5), 583-585.

- Nayak, S., Dairaku, K., Takayabu, I., Suzuki-Parker, A., & Ishizaki, N. N. (2018). Extreme precipitation linked to temperature over Japan: current evaluation and projected changes with multi-model ensemble downscaling. Climate Dynamics, 51, 4385–4401. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.K., Choudhury, G., Vissa, N.K., Tyagi, B., & Nayak, S. (2022). The Impact of El-Niño and La-Niña on the Pre-Monsoon Convective Systems over Eastern India. Atmosphere, 13(8), 1261.

- Sahu, R.K., Nayak, S., Singh, K.S., Nayak, H.P., & Tyagi, B. (2023). Evaluating the impact of topography on the initiation of Nor’westers over eastern India. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 14(1), 2184669. [CrossRef]

- Trošelj, J., Nayak, S., Hobohm, L., & Takemi, T. (2023). Real-time flash flood forecasting approach for development of early warning systems: integrated hydrological and meteorological application. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 14(1), 2269295. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Mandal, M. (2019). Examining the impact of regional land use and land cover changes on temperature: the case of Eastern India. Spatial Information Research, 27, 601-611. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Mandal, M. (2019). Impact of land use and land cover changes on temperature trends over India. Land Use Policy, 89, 104238. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. (2021). Land use and land cover change and their impact on temperature over central India. Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences, 14(3), 339–356. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Mandal, M. (2012). Impact of land-use and land-cover changes on temperature trends over Western India. Current Science, 102(8), 1166-1173.

- Nayak, S., Maity, S., Singh, K. S., Nayak, H. P., & Dutta, S. (2021). Influence of the changes in land-use and land cover on temperature over Northern and North-Eastern India. Land, 10(52), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Maity, S., Sahu, N., Saini, A., Singh, K. S., Nayak, H. P., & Dutta, S. (2022). Application of "Observation Minus Reanalysis" Method towards LULC Change Impact over Southern India. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 11(2), 94. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, H.P., Nayak, S., Maity, S., Patra, N., Singh, K.S., & Dutta, S. (2022). Sensitivity of Land Surface Processes and Its Variation during Contrasting Seasons over India. Atmosphere, 13, 1382. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Behera, M.D. (2008). Land use/land cover classification and mapping of Pilibhit District, Uttar Pradesh, India. Indian Geographical Journal, 83, 15-24.

- Meinander, O., Dagsson-Waldhauserova, P., Amosov, P., Aseyeva, E., Atkins, C., Baklanov, A.,... & Vukovic Vimic, A. (2021). Newly identified climatically and environmentally significant high latitude dust sources. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions, 2021, 1-74.

- Nayak, S., & Behera, M. D. (2009). Improving Land Use and Vegetation Cover Classification Accuracy using Fuzzy Logic - A Study in Pilibhit District Uttar Pradesh, India. International Journal of Geoinformatics, 5(2), 1–10.

- Nayak, S., Mandal, M., & Maity, S. (2021). Assessing the impact of Land-use and Land-cover changes on the climate over India using a Regional Climate Model (RegCM4). Climate Research, 85, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Maity, S., Satyanarayana, A.N.V., Mandal, M., & Nayak, S. (2017). Performance evaluation of land surface models and cumulus convection schemes in the simulation of Indian summer monsoon using a regional climate model. Atmospheric Research, 197, 21–41. [CrossRef]

- Maity, S., Mandal, M., Nayak, S., & Bhatla, R. (2017). Performance of cumulus parameterization schemes in the simulation of Indian Summer Monsoon using RegCM4. Atmósfera, 30(4), 287-309. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2025). Regional and vertical scaling of water vapor with temperature over Japan during extreme precipitation in a changing climate. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 34826. [CrossRef]

- Maity, S., Nayak, S., Singh, K.S., Nayak, H.P., & Dutta, S. (2021). Impact of soil moisture initialization in the simulation of Indian summer monsoon using RegCM4. Atmosphere, 12, 1148. [CrossRef]

- Maity, S., Nayak, S., Nayak, H. P., & Bhatla, R. (2022). Comprehensive assessment of RegCM4 towards interannual variability of Indian summer monsoon using multi-year simulations. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 147, 129–140. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Mandal, M., & Maity, S. (2017). Customization of regional climate model (RegCM4) over Indian region. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 127, 153-168. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Mandal, M., & Maity, S. (2018). RegCM4 simulation with AVHRR land use data towards temperature and precipitation climatology over Indian region. Atmospheric Research, 214, 163–173. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Mandal, M., & Maity, S. (2019). Performance evaluation of RegCM4 in simulating temperature and precipitation climatology over India. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 138(3), 1535–1552. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2019). Dynamical Downscaling of Typhoon Lionrock (2016) for Assessing the Resulting Hazards under Global Warming. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, 97(1), 123–143. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2019). Quantitative estimations of hazards resulting from Typhoon Chanthu (2016) for assessing the impact in current and future climate. Hydrological Research Letters, 13(2), 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2020). Robust responses of typhoon hazards in northern Japan to global warming climate: cases of landfalling typhoons in 2016. Meteorological Applications, 27, e1954. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2020). Typhoon-induced precipitation characterization over northern Japan: a case study for typhoons in 2016. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science, 7(39). [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2023). Statistical analysis of the characteristics of typhoons approaching Japan from 2006 to 2019. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 14(1), 2208722. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Takemi, T. (2023). Structural characteristics of typhoons Jebi (2018), Faxai (2019), and Hagibis (2019). Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics, 135(34). [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. S., Nayak, S., Maity, S., Nayak, H. P., & Dutta, S. (2023). Prediction of extremely severe cyclonic storm “Fani” using moving nested domain. Atmosphere, 14(4), 637. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Kanda, I. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of Doppler lidar-based observation nudging in WRF simulation for wind field: A case study over Osaka, Japan. Atmosphere, 14(972). [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J. E., Ballinger, T. J., Euskirchen, E. S., Hanna, E., Mård, J., Overland, J. E.,... & Vihma, T. (2020). Extreme weather and climate events in northern areas: A review. Earth-Science Reviews, 209, 103324. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. (2024). Temporal Characteristics of Rainfall Events at Very High Timescale. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Koteshwaramma, T., Singh, K. S., & Nayak, S. (2024). Performance of High-Resolution WRF Modeling System in Simulation of Severe Tropical Cyclones over the Bay of Bengal Using IMDAA Regional Reanalysis Dataset. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., Trošelj, J., Pattnayak, K. C., & Bharambe, K. P. (2025). Exploring the Underlying Patterns and Relationships Between Temperature and Heavy Rainfall Events over Western Japan. In Computing, Communication and Intelligence (pp. 300-304). CRC Press.

- Mishra, M., Mishra, A., Mangaraj, P., Srivastava, A. K., Beig, G., Sahoo, P.,... & Sahu, S. K. (2025). Quantification and spatial assessment of industrial Cd and Pb emission across India. All Earth, 37(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. S., Nayak, S., Maity, S., Nayak, H. P., & Dutta, S. (2022). Prediction of Bay of Bengal Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm "Fani” Using Moving Nested Domain. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Maity, S. (2021). Evaluating the Performance of Cumulus Convection Parameterization Schemes in Regional Climate Modeling System. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. (2021). Assessing the Changes of the Landmass Surrounded by the Indian Coast. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Crisp, D., Dolman, H., Tanhua, T., McKinley, G. A., Hauck, J., Bastos, A.,... & Aich, V. (2022). How well do we understand the land-ocean-atmosphere carbon cycle?. Reviews of Geophysics, 60(2), e2021RG000736.

- Bindajam, A. A., Mallick, J., AlQadhi, S., Singh, C. K., & Hang, H. T. (2020). Impacts of vegetation and topography on land surface temperature variability over the semi-arid mountain cities of Saudi Arabia. Atmosphere, 11(7), 762. [CrossRef]

- Lhotka, O., Trnka, M., Kyselý, J., Markonis, Y., Balek, J., & Možný, M. (2020). Atmospheric circulation as a factor contributing to increasing drought severity in central Europe. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 125(18), e2019JD032269. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., & Sahu, N. (2025). Editorial for the Special Issue on Climate Change and Climate Variability, and Their Impact on Extreme Events. Atmosphere, 16(2), 182. [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y., Wang, S., Yang, Z. L., & Gentine, P. (2023). Soil moisture− atmosphere feedbacks have triggered the shifts from drought to pluvial conditions since 1980. Communications Earth & Environment, 4(1), 254. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. (2024). Understanding the Interaction Between Land, Atmosphere and Ocean Towards Intensifying the Extreme Weather Events.

- Koteshwaramma, T., Singh, K. S., & Nayak, S. (2025). The Performance of a High-Resolution WRF Modelling System in the Simulation of Severe Tropical Cyclones over the Bay of Bengal Using the IMDAA Regional Reanalysis Dataset. Climate, 13(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Maity, S., Patil, K., & Nayak, S. (2025). Evaluation of CMIP6 models for future rainfall projections over India: Insights on bias correction and scenario-based variability.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).