Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mechanism of Adsorption Using Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

2.1. General Conceptions of Adsorption

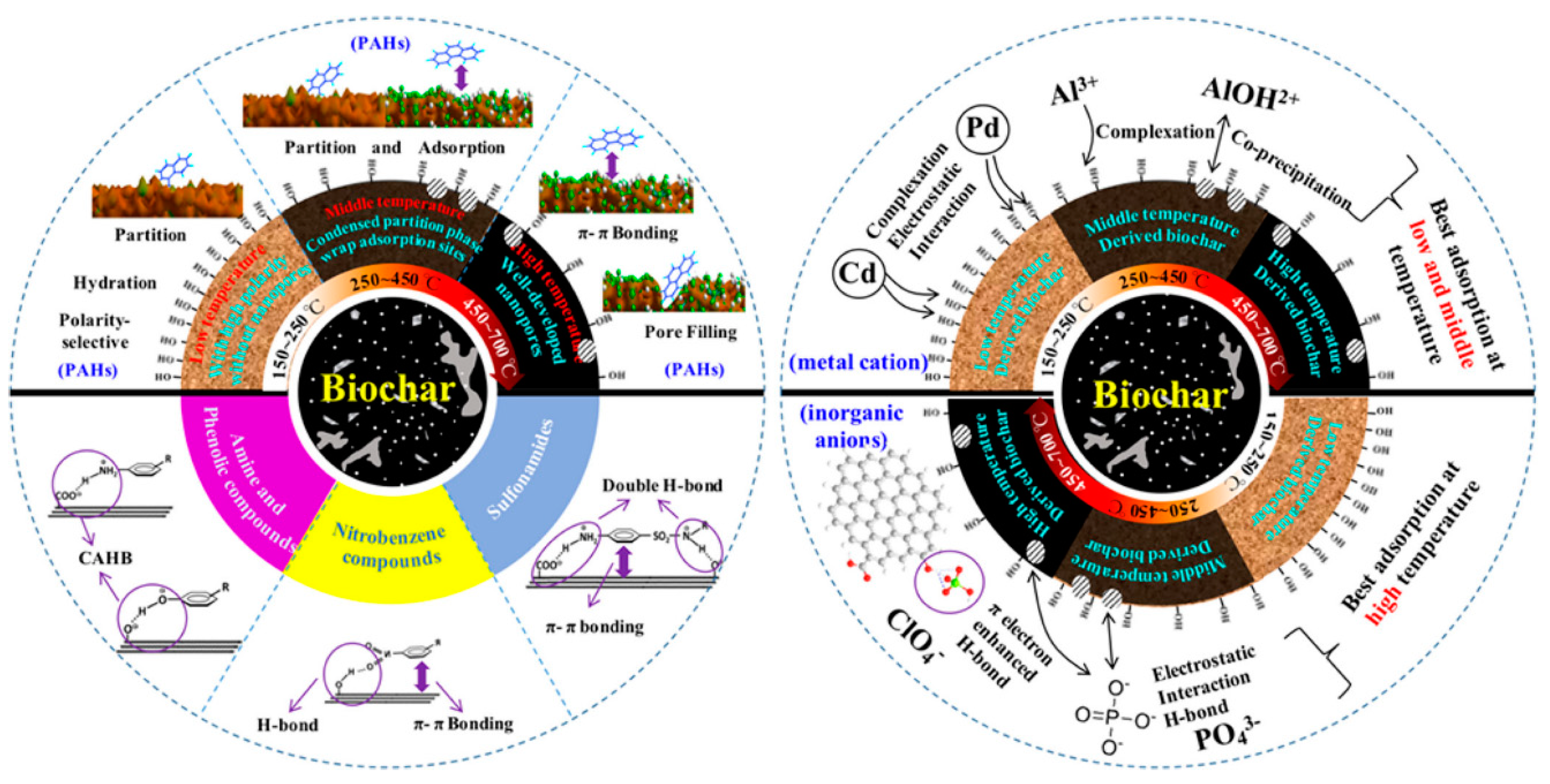

2.2. Interactions Between Biochar and Contaminants in Wastewater

2.3. Description and Illustration of Adsorption in Wastewater

3. Preparation and Characterization of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

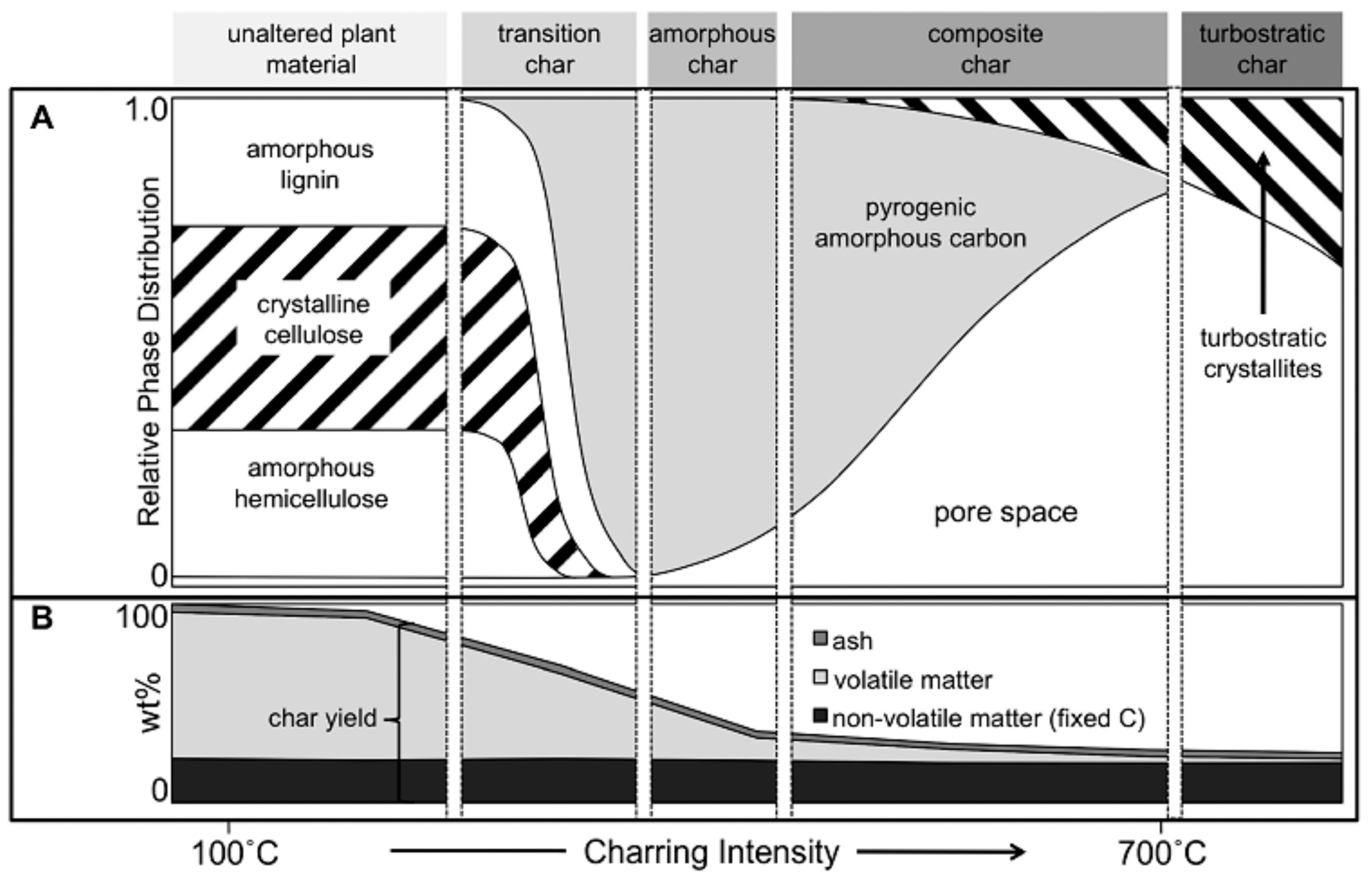

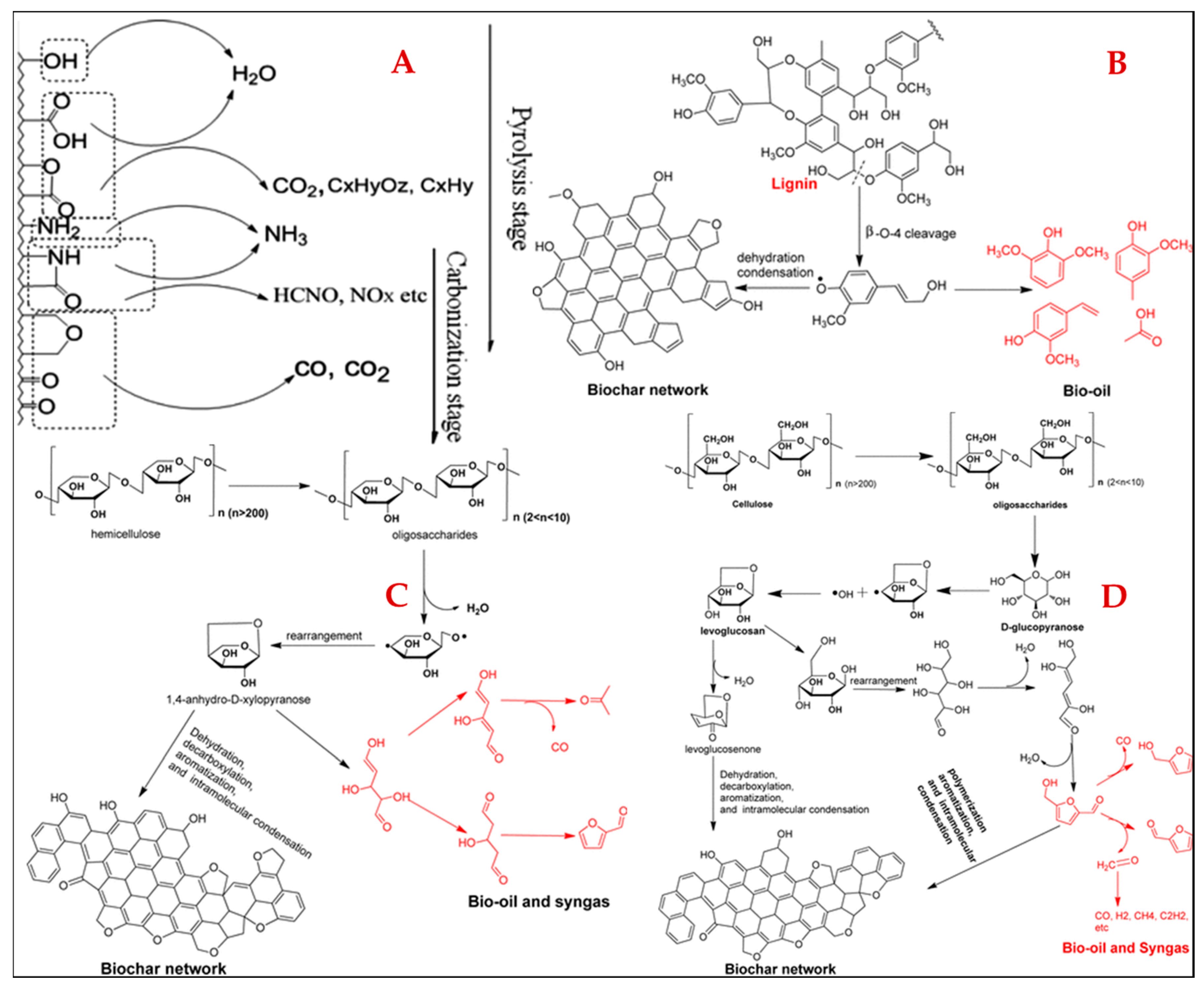

3.1. General Conceptions and Properties of Biochar

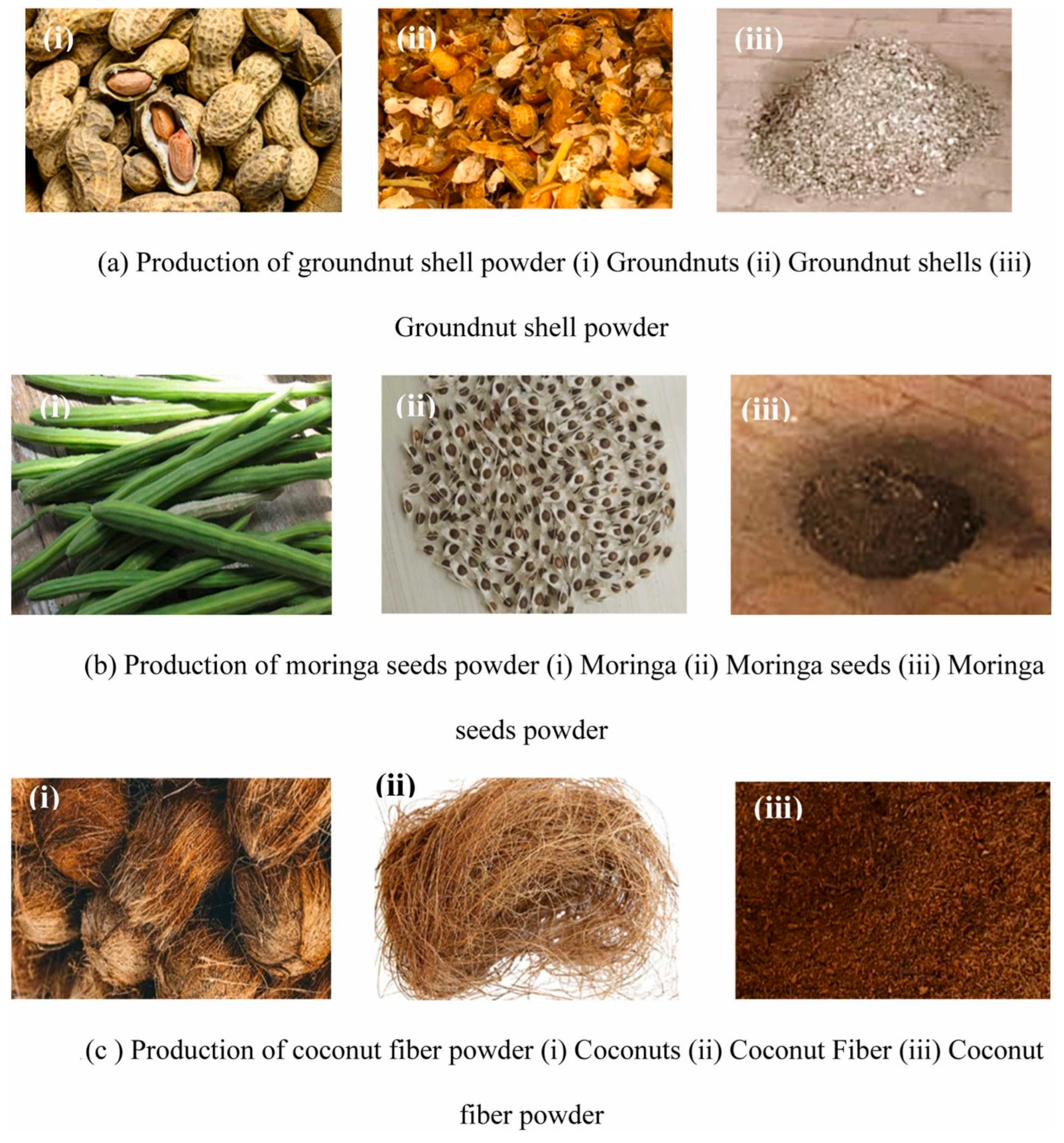

3.2. Preparation of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

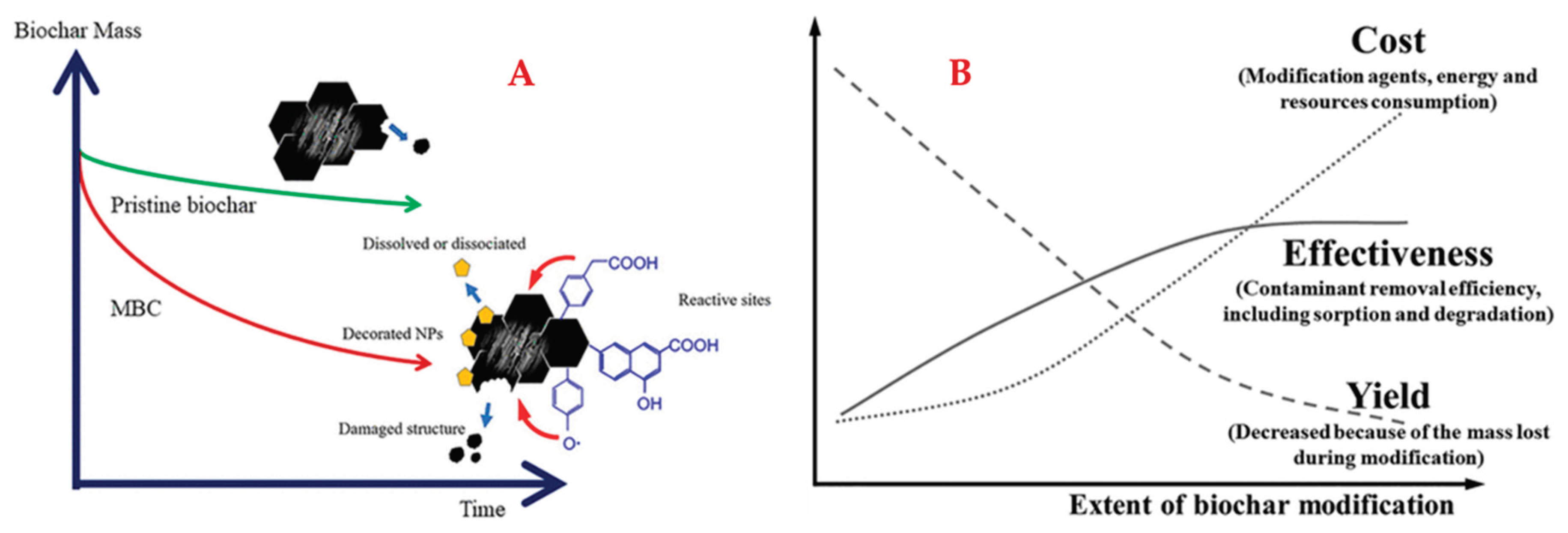

3.3. Improved Fabrication of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar

3.4. Characterization of Biochar

4. Use of Agricultural Residue-Based Biochar for Wastewater Remediation

5. Economic Evaluation and Environmental Impacts

6. Future Directions and Challenges

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BET BOD COD EDS FT-IR PFO pHL pHpzc PSO SEM TC TDS TGA TOC TS TSS TVSS XPS XRD |

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller Biochemical oxygen demand Chemical oxygen demand Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy Pseudo-first order pH of liquids Point of zero charge Pseudo-second order Scanning electron microscopy Total organic carbon Total dissolved solids Thermogravimetric Analysis Total organic carbon The total solids Total suspended solids Total volatile suspended solids X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy X-ray diffraction |

References

- Shi, T.-T.; Yang, B.; Hu, W.-G.; Gao, G.-J.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Yu, J.-G. Garlic Peel-Based Biochar Prepared under Weak Carbonation Conditions for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue from Wastewater. Molecules 2024, 29, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshakhs, F.; Gijjapu, D.R.; Aminul Islam, Md.; Akinpelu, A.A.; Nazal, M.K. A Promising Palm Leaves Waste-Derived Biochar for Efficient Removal of Tetracycline from Wastewater. J Mol Struct 2024, 1296, 136846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, H.; Liu, G.; Fang, J. Recent Advances and Perspectives of Biochar for Livestock Wastewater: Modification Methods, Applications, and Resource Recovery. J Environ Chem Eng 2024, 12, 113678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlović, I.; Hgeig, A.; Novaković, M.; Gvoić, V.; Ubavin, D.; Petrović, M.; Kurniawan, T.A. Valorizing Date Seeds into Biochar for Pesticide Removal: A Sustainable Approach to Agro-Waste-Based Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, X. Magnetic Coconut Shell Biochar/Sodium Alginate Composite Aerogel Beads for Efficient Removal of Methylene Blue from Wastewater: Synthesis, Characterization, and Mechanism. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 284, 137945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Mo, Y.; Lin, X.; Gao, S.; Chen, M. Efficient Removal of Atrazine in Wastewater by Washed Peanut Shells Biochar: Adsorption Behavior and Biodegradation. Process Biochemistry 2025, 154, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Lee, J.; Cravotto, G. Sonocatalytic Degrading Antibiotics over Activated Carbon in Cow Milk. Food Chem 2024, 432, 137168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Cavitational Technologies for the Removal of Antibiotics in Water and Milk. PhD, University of Turin, 2023.

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Cannizzo, F.T.; Mantegna, S.; Cravotto, G. Removal of Antibiotics from Milk via Ozonation in a Vortex Reactor. J Hazard Mater 2022, 440, 129642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Cravotto, G. Sonolytic Degradation Kinetics and Mechanisms of Antibiotics in Water and Cow Milk. Ultrason Sonochem 2023, 99, 106518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M.; Liao, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, S.; Liao, W.; Zhao, X. Removal of Anthracene from Vehicle-Wash Wastewater through Adsorption Using Eucalyptus Wood Waste-Derived Biochar. Desalination Water Treat 2024, 317, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizkallah, B.M.; Galal, M.M.; Matta, M.E. Characteristics of Tetracycline Adsorption on Commercial Biochar from Synthetic and Real Wastewater in Batch and Continuous Operations: Study of Removal Mechanisms, Isotherms, Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Desorption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Tang, S.; You, X.; Li, Y.; Mei, Y.; Chen, Y. Investigation of the Key Mechanisms and Optimum Conditions of High-Effective Phosphate Removal by Bimetallic La-Fe-CNT Film. Sep Purif Technol 2024, 341, 126938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Ye, J. Comparison Study of Naphthalene Adsorption on Activated Carbons Prepared from Different Raws. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2018, 35, 2086–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Ge, X.; Yang, X. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Microwave-Assisted Activation of Starch-Derived Carbons as an Effective Adsorbent for Naphthalene Removal. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 11696–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Manzoli, M.; Cravotto, G. Magnetic Biochar Generated from Oil-Mill Wastewater by Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Treatment for Sonocatalytic Antibiotic Degradation. J Environ Chem Eng 2025, 13, 114996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viotti, P.; Marzeddu, S.; Antonucci, A.; Décima, M.A.; Lovascio, P.; Tatti, F.; Boni, M.R. Biochar as Alternative Material for Heavy Metal Adsorption from Groundwaters: Lab-Scale (Column) Experiment Review. Materials 2024, 17, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boni, M.; Marzeddu, S.; Tatti, F.; Raboni, M.; Mancini, G.; Luciano, A.; Viotti, P. Experimental and Numerical Study of Biochar Fixed Bed Column for the Adsorption of Arsenic from Aqueous Solutions. Water (Basel) 2021, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Ding, H.; Wan, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gao, J. Cost-Effective Biochar Produced from Agricultural Residues and Its Application for Preparation of High Performance Form-Stable Phase Change Material via Simple Method. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin, T.; Komala, P.S.; Mera, M.; Zulkarnaini, Z.; Jamil, Z. Coconut Shell Biochar as a Sustainable Approach for Nutrient Removal from Agricultural Wastewater. Journal of Water and Land Development 2025, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konneh, M.; Wandera, S.M.; Murunga, S.I.; Raude, J.M. Adsorption and Desorption of Nutrients from Abattoir Wastewater: Modelling and Comparison of Rice, Coconut and Coffee Husk Biochar. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tariq, M.; Ali Baig, S.; Shams, D.F.; Hussain, S.; Hussain, R.; Qadir, A.; Maryam, H.S.; Khan, Z.U.; Sattar, S.; Xu, X. Dye Wastewater Treatment Using Wheat Straw Biochar in Gadoon Industrial Areas of Swabi, Pakistan. Water Conservation Science and Engineering 2022, 7, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.; Nizamuddin, S.; Griffin, G.; Selvakannan, P.; Mubarak, N.M.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Synthesis and Characterization of Rice Husk Biochar via Hydrothermal Carbonization for Wastewater Treatment and Biofuel Production. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huong, P.T.; Jitae, K.; Al Tahtamouni, T.M.; Le Minh Tri, N.; Kim, H.-H.; Cho, K.H.; Lee, C. Novel Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by Biochar Derived from Rice Husk toward Oxidation of Organic Contaminants in Wastewater. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2020, 33, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Chu, T.T.H.; Nguyen, D.K.; Le, T.K.O.; Obaid, S. Al; Alharbi, S.A.; Kim, J.; Nguyen, M.V. Alginate-Modified Biochar Derived from Rice Husk Waste for Improvement Uptake Performance of Lead in Wastewater. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nguyen, Q.; Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Duong, T.D.; Dong, M.N.T.; Tran, H.M.T.; Van Hoang, H. Evaluation of Adsorption and Desorption of Wastewater onto Rice Husk Biochar on the Course of Hydroponic Nutrient Production. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2025, 15, 18615–18628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, Q.; Nguyen, K.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Van Hoang, H.; Duong, T.D.; Dong, M.T.N.; Tran, H.T.M. Transforming Domestic Wastewater into Hydroponic Nutrients Using Corncob-Derived Biochar Adsorption. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr 2025, 25, 3708–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Bojmehrani, A.; Zare, E.; Zare, Z.; Hosseini, S.M.; Bakhshabadi, H. Optimization of Antioxidant Extraction Process from Corn Meal Using Pulsed Electric Field-subcritical Water. J Food Process Preserv 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walanda, D.K.; Anshary, A.; Napitupulu, M.; Walanda, R.M. The Utilization of Corn Stalks as Biochar to Adsorb BOD and COD in Hospital Wastewater. International Journal of Design and Nature and Ecodynamics 2022, 17, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, L.; Li, W.; Yao, H.; Luo, H.; Liu, G.; Fang, J. Corn Stover Waste Preparation Cerium-Modified Biochar for Phosphate Removal from Pig Farm Wastewater: Adsorption Performance and Mechanism. Biochem Eng J 2024, 212, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.T.H.; Nguyen, M.V. Improved Cr (VI) Adsorption Performance in Wastewater and Groundwater by Synthesized Magnetic Adsorbent Derived from Fe3O4 Loaded Corn Straw Biochar. Environ Res 2023, 216, 114764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, F.; Slijepcevic, A.; Piantini, U.; Frey, U.; Abiven, S.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Charlet, L. Real Wastewater Micropollutant Removal by Wood Waste Biomass Biochars: A Mechanistic Interpretation Related to Various Biochar Physico-Chemical Properties. Bioresour Technol Rep 2022, 17, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guo, H.; Jiang, D.; Cheng, S.; Xing, B.; Meng, W.; Fang, J.; Xia, H. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Rape Stalk to Prepare Biochar for Heavy Metal Wastewater Removal. Diam Relat Mater 2023, 134, 109794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sarsaiya, S.; Chen, H.; Singh, E.; Kumar, A.; Ravindran, B.; Awasthi, S.K.; Liu, T.; Duan, Y.; et al. Resource Recovery and Circular Economy from Organic Solid Waste Using Aerobic and Anaerobic Digestion Technologies. Bioresour Technol 2020, 301, 122778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Ghosh, G.K.; Avasthe, R. Conversion of Crop, Weed and Tree Biomass into Biochar for Heavy Metal Removal and Wastewater Treatment. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023, 13, 4901–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Barge, A.; Boffa, L.; Martina, K.; Cravotto, G. Determination of Trace Antibiotics in Water and Milk via Preconcentration and Cleanup Using Activated Carbons. Food Chem 2022, 385, 132695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masmoudi, M.A.; Abid, N.; Feki, F.; Karray, F.; Chamkha, M.; Sayadi, S. Study of Olive Mill Wastewater Adsorption onto Biochar as a Pretreatment Option within a Fully Integrated Process. EuroMediterr J Environ Integr 2024, 9, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fito, J.; Abewaa, M.; Nkambule, T. Magnetite-Impregnated Biochar of Parthenium Hysterophorus for Adsorption of Cr(VI) from Tannery Industrial Wastewater. Appl Water Sci 2023, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, M.; Babaee, S.; Worku, A.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Nure, J.F. The Development of Giant Reed Biochar for Adsorption of Basic Blue 41 and Eriochrome Black T. Azo Dyes from Wastewater. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 18320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Illankoon, W.A.M.A.N.; Milanese, C.; Calatroni, S.; Caccamo, F.M.; Medina-Llamas, M.; Girella, A.; Sorlini, S. Preparation and Modification of Biochar Derived from Agricultural Waste for Metal Adsorption from Urban Wastewater. Water (Basel) 2024, 16, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Zhang, X.; Varjani, S.; Liu, Y. Feasibility Study on a New Pomelo Peel Derived Biochar for Tetracycline Antibiotics Removal in Swine Wastewater. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 720, 137662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hu, H.; Wu, X.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, R.; Zheng, H. Coupling of Biochar-Mediated Absorption and Algal-Bacterial System to Enhance Nutrients Recovery from Swine Wastewater. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 701, 134935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, B.; Sommer-Márquez, A.; Ordoñez, P.E.; Bastardo-González, E.; Ricaurte, M.; Navas-Cárdenas, C. Synthesis Methods, Properties, and Modifications of Biochar-Based Materials for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Resources 2024, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.O.; Yaqoob, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.N.M.; Ahmad, A.; Alshammari, M.B. Introduction of Adsorption Techniques for Heavy Metals Remediation. In Emerging Techniques for Treatment of Toxic Metals from Wastewater; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 1–18.

- Wu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Liu, P.; Li, Q.; Yang, R.; Yang, X. Competitive Adsorption of Naphthalene and Phenanthrene on Walnut Shell Based Activated Carbon and the Verification via Theoretical Calculation. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 10703–10714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, B.; Petropoulos, E.; Duan, J.; Yang, L.; Xue, L. The Potential of Biochar as N Carrier to Recover N from Wastewater for Reuse in Planting Soil: Adsorption Capacity and Bioavailability Analysis. Separations 2022, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Cravotto, G. In Situ Modification of Activated Carbons by Oleic Acid under Microwave Heating to Improve Adsorptive Removal of Naphthalene in Aqueous Solutions. Processes 2021, 9, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, A.S.; Popoola, L.T.; Ibrahim, I.S. Adsorptive Removal of Anthraquinone Dye from Wastewater Using Silica-Nitrogen Reformed Eucalyptus Bark Biochar: Parametric Optimization, Isotherm and Kinetic Studies. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2025, 166, 105503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, M.; Niu, B.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Jiang, K. Rotten Sugarcane Bagasse Derived Biochars with Rich Mineral Residues for Effective Pb (II) Removal in Wastewater and the Tech-Economic Analysis. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2022, 132, 104231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Tan, W.; Liu, X.; Jin, Y.; Qu, J. Adsorption of Cd(II) onto Auricularia Auricula Spent Substrate Biochar Modified by CS2: Characteristics, Mechanism and Application in Wastewater Treatment. J Clean Prod 2022, 367, 132882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaime, G.; Baçaoui, A.; Yaacoubi, A.; Lübken, M. Biochar for Wastewater Treatment—Conversion Technologies and Applications. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewoye, T.L.; Ogunleye, O.O.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Salawudeen, T.O.; Tijani, J.O. Optimization of the Adsorption of Total Organic Carbon from Produced Water Using Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghebrehiwot, H.; Fynn, R.; Morris, C.; Kirkman, K. Shoot and Root Biomass Allocation and Competitive Hierarchies of Four South African Grass Species on Light, Soil Resources and Cutting Gradients. Afr J Range Forage Sci 2006, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonam, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Bharti, S.K.; Kumar, N. Kinetic Study of Lead (Pb2+) Removal from Battery Manufacturing Wastewater Using Bagasse Biochar as Biosorbent. Appl Water Sci 2018, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashebir, H.; Nure, J.F.; Worku, A.; Msagati, T.A.M. Prosopis Juliflora Biochar for Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole and Ciprofloxacin from Pharmaceutical Wastewater. Desalination Water Treat 2024, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Mo, H.; Gao, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X. Adsorption of Crystal Violet from Wastewater Using Alkaline-Modified Pomelo Peel-Derived Biochar. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 68, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Du, W.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Kang, W. Adsorption Characteristics and Removal Mechanism of Quinoline in Wastewater by Walnut Shell-Based Biochar. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2025, 70, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, W.; Lan, X.; Guo, J.; Cai, A.; Liu, P.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Lei, Y. Preparation of Iron/Calcium-Modified Biochar for Phosphate Removal from Industrial Wastewater. J Clean Prod 2023, 383, 135468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illankoon, W.A.M.A.N.; Milanese, C.; Karunarathna, A.K.; Liyanage, K.D.H.E.; Alahakoon, A.M.Y.W.; Rathnasiri, P.G.; Collivignarelli, M.C.; Sorlini, S. Evaluating Sustainable Options for Valorization of Rice By-Products in Sri Lanka: An Approach for a Circular Business Model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasubramanian, K.; Thangagiri, B.; Sakthivel, A.; Dhaveethu Raja, J.; Seenivasan, S.; Vallinayagam, P.; Madhavan, D.; Malathi Devi, S.; Rathika, B. A Complete Review on Biochar: Production, Property, Multifaceted Applications, Interaction Mechanism and Computational Approach. Fuel 2021, 292, 120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Vaccari, M.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Amrane, A.; Rtimi, S. Mechanisms and Adsorption Capacities of Biochar for the Removal of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants from Industrial Wastewater. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2021, 18, 3273–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, M.; Keskin, M.E.; Mazlum, S.; Mazlum, N. Hg(II) and Pb(II) Adsorption on Activated Sludge Biomass: Effective Biosorption Mechanism. Int J Miner Process 2008, 87, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zeng, W.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Peng, Y. Adsorption Removal and Reuse of Phosphate from Wastewater Using a Novel Adsorbent of Lanthanum-Modified Platanus Biochar. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2020, 140, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chen, B.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, L.; Schnoor, J.L. Insight into Multiple and Multilevel Structures of Biochars and Their Potential Environmental Applications: A Critical Review. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52, 5027–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Cravotto, G. In Situ Modification of Activated Carbons by Oleic Acid under Microwave Heating to Improve Adsorptive Removal of Naphthalene in Aqueous Solutions. Processes 2021, 9, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Hameed, B.H. Insight into the Adsorption Kinetics Models for the Removal of Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2017, 74, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musah, M.; Azeh, Y.; Mathew, J.; Umar, M.; Abdulhamid, Z.; Muhammad, A. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherm Models: A Review. Caliphate Journal of Science and Technology 2022, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Guo, X. Guideline for Modeling Solid-Liquid Adsorption: Kinetics, Isotherm, Fixed Bed, and Thermodynamics. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Da’ana, D.A. Guidelines for the Use and Interpretation of Adsorption Isotherm Models: A Review. J Hazard Mater 2020, 393, 122383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Largitte, L.; Pasquier, R. A Review of the Kinetics Adsorption Models and Their Application to the Adsorption of Lead by an Activated Carbon. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2016, 109, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; You, X.; Tang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Mei, Y.; Shu, W. Phosphate Uptake over the Innovative La–Fe–CNT Membrane: Structure-Activity Correlation and Mechanism Investigation. ACS ES&T Engineering 2024, 4, 2642–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundari, L.; Prasanna, K. Optimum Usage of Biochar Derived from Agricultural Biomass in Removing Organic Pollutant Present in Pharmaceutical Wastewater. Sustainable Chemistry for the Environment 2025, 10, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Über Die Adsorption in Lösungen. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 1907, 57U, 385–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fseha, Y.H.; Shaheen, J.; Sizirici, B. Phenol Contaminated Municipal Wastewater Treatment Using Date Palm Frond Biochar: Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Emerg Contam 2023, 9, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Lei, Z.; Zheng, B.; Xia, H.; Su, Y.; Ali, K.M.Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Beryllium Adsorption from Beryllium Mining Wastewater with Novel Porous Lotus Leaf Biochar Modified with PO43−/NH4+ Multifunctional Groups (MLLB). Biochar 2024, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdeha, E. Biochar-Based Nanocomposites for Industrial Wastewater Treatment via Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation and the Parameters Affecting These Processes. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024, 14, 23293–23318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motasemi, F.; Afzal, M.T. A Review on the Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis Technique. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 28, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, R.; Gopinath, K.P.; Kumar, P.S. Adsorptive Separation of Toxic Metals from Aquatic Environment Using Agro Waste Biochar: Application in Electroplating Industrial Wastewater. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 128031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutarut, P.; Cheirsilp, B.; Boonsawang, P. The Potential of Oil Palm Frond Biochar for the Adsorption of Residual Pollutants from Real Latex Industrial Wastewater. Int J Environ Res 2023, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-J.; Jiang, H.; Yu, H.-Q. Development of Biochar-Based Functional Materials: Toward a Sustainable Platform Carbon Material. Chem Rev 2015, 115, 12251–12285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.W.; Mubarak, N.M.; Sahu, J.N.; Abdullah, E.C. Microwave Induced Synthesis of Magnetic Biochar from Agricultural Biomass for Removal of Lead and Cadmium from Wastewater. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2017, 45, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.A.; Izzuddin, N.M.; Bahari, M.B.; Hatta, A.H.; Kasmani, R.M.; Norazahar, N. Recent Advances in Lignocellulosic Biomass-Derived Biochar-Based Photocatalyst for Wastewater Remediation. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2024, 163, 105670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Goldfarb, J.L. Heterogeneous Biochars from Agriculture Residues and Coal Fly Ash for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Coking Wastewater. RSC Adv 2019, 9, 16018–16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.-T.; Do, K.-U. Insights into Adsorption of Ammonium by Biochar Derived from Low Temperature Pyrolysis of Coffee Husk. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023, 13, 2193–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lap, B.Q.; Thinh, N.V.D.; Hung, N.T.Q.; Nam, N.H.; Dang, H.T.T.; Ba, H.T.; Ky, N.M.; Tuan, H.N.A. Assessment of Rice Straw–Derived Biochar for Livestock Wastewater Treatment. Water Air Soil Pollut 2021, 232, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Maitra, J.; Khan, K.A. Development of Biochar and Chitosan Blend for Heavy Metals Uptake from Synthetic and Industrial Wastewater. Appl Water Sci 2017, 7, 4525–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Han, J.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, S.; Lee, S.H. Reswellable Alginate/Activated Carbon/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Hydrogel Beads for Ibuprofen Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 249, 126053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Abbas, G. Phosphorus Removal Using Ferric–Calcium Complex as Precipitant: Parameters Optimization and Phosphorus-Recycling Potential. Chemical Engineering Journal 2015, 268, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumi, A.G.; Ibrahim, M.G.; Fujii, M.; Nasr, M. Petrochemical Wastewater Treatment by Eggshell Modified Biochar as Adsorbent: Atechno-Economic and Sustainable Approach. Adsorption Science & Technology 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, W.; Peng, H.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Functional Biochar and Its Balanced Design. ACS Environmental Au 2022, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzyka, R.; Misztal, E.; Hrabak, J.; Banks, S.W.; Sajdak, M. Various Biomass Pyrolysis Conditions Influence the Porosity and Pore Size Distribution of Biochar. Energy 2023, 263, 126128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeonuegbu, B.A.; Machido, D.A.; Whong, C.M.Z.; Japhet, W.S.; Alexiou, A.; Elazab, S.T.; Qusty, N.; Yaro, C.A.; Batiha, G.E.-S. Agricultural Waste of Sugarcane Bagasse as Efficient Adsorbent for Lead and Nickel Removal from Untreated Wastewater: Biosorption, Equilibrium Isotherms, Kinetics and Desorption Studies. Biotechnology Reports 2021, 30, e00614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruthi, S.; Vishalakshi, B. Hybrid Banana Pseudo Stem Biochar- Poly (N-Hydroxyethylacrylamide) Hydrogel and Its Magnetic Nanocomposite for Effective Remediation of Dye from Wastewater. J Environ Chem Eng 2024, 12, 112682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egila, J.N.; Dauda, B.E.N.; Iyaka, Y.A.; Jimoh, T. Agricultural Waste as a Low Cost Adsorbent for Heavy Metal Removal from Wastewater. Int J Phys Sci 2011, 6, 2152–2157. [Google Scholar]

- El Ouassif, H.; Gayh, U.; Ghomi, M.R. Biochar Production from Agricultural Waste (Corncob) to Remove Ammonia from Livestock Wastewater. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Philip, L. Sustainability Assessment of Acid-Modified Biochar as Adsorbent for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products from Secondary Treated Wastewater. J Environ Chem Eng 2022, 10, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.; Galinato, S.; Granatstein, D.; Garcia-Pérez, M. Economic Tradeoff between Biochar and Bio-Oil Production via Pyrolysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fdez-Sanromán, A.; Pazos, M.; Rosales, E.; Sanromán, M.A. Unravelling the Environmental Application of Biochar as Low-Cost Biosorbent: A Review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, J.L.; Lehmann, J. Energy Balance and Emissions Associated with Biochar Sequestration and Pyrolysis Bioenergy Production. Environ Sci Technol 2008, 42, 4152–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.Y.; Hwang, G.Y.; Um, J.B. An Analysis of the Influence Factors of Farmers’ Acceptance Intention on Low Carbon Agricultural Technology Bio-Char. Journal of Agricultural Extension & Community Development 2023, 30, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, R.D.; Zhang, * -Hanwen; Englund, K.; Windell, K.; Gu, H. Curitiba, Brazil Proceedings of the 59th International Convention of Society of Wood Science and Technology, 2016.

- Thuan, D. Van; Chu, T.T.H.; Thanh, H.D.T.; Le, M.V.; Ngo, H.L.; Le, C.L.; Thi, H.P. Adsorption and Photodegradation of Micropollutant in Wastewater by Photocatalyst TiO2/Rice Husk Biochar. Environ Res 2023, 236, 116789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanisms | Illustrations | Examples | Refs. |

| Precipitation | Contaminants can chemically precipitate via reaction with the liquid solute or biochar surface, and are finally adsorbed on the biochar surface | i) Between Al3+, Fe3+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Pb2+, or Cd2+ and OH- at alkaline conditions ii) Between PO43- and Fe-doped biochar to form Fe3(PO4)2·(H2O)8 |

[37,42,58] |

| Complexation | Biochar surface’s functional groups can act as electron donors or acceptors, interact with metal ions or ammonium ions to produce complexes | i) Between -OH groups and Fe2+ ii) Between phosphate and ammonium ion iii) Between –COOH, C=O, or –OH with Cr6+ iv) Between OH-, C=O or C–OH with Pb2+ v) Between -NH2 and Cu2+ or Pb2+ |

[31,40,54] |

| H-bonding | H-bonding (theoretical bond energies of 4–17 kJ/mol) can be formed via the interaction between the functional groups on the biochar surface (e.g., -NH2 and -OH) with F-, N-, or O- containing molecules | i) Between -OH and ammonium ion or -NO2 ii) Between -OH and -OH or -NH2 iii) Between -COOH and its conjugate acid |

[5,46,59] |

| Electrostatic attraction and repulsion | Electrostatic interaction refers to the formation of ionic bonds between surface-charged biochar and ions or charged molecules. Electrostatic interaction is highly related to the pH of liquids, surface charge of the biochar, and pKa of the target substrates, which can be limited under high pH | i) Between cationic dye and -COO-of biochar ii) Between the Si-N of biochar and anionic dyes iii) Between Mn2+ and -OH, -COOH, or C=O of biochar iv) Between PO43- and nitrate or nitrite of biochar v) Between the same ions on the biochar surface and in liquids |

[5,48,60] |

| π-π electron donor–acceptor interaction | π-π interactions (theoretical bond energies of 4-167 kJ/mol) are weak non-covalent bonds, referring to interactions between groups with π electron systems (e.g., -Ph, -C=C-, C=O, -COOH, -OH, and C-O) of the biochar surface and the target compounds | i) Between -Ph of biochar and the enone structure of tetracycline ii) Between -OH or -COOH of biochar surface and -Ph of phenolic compounds |

[2,6,12] |

| Pore-filling | Pore filling is a physisorption process, referring to the substrate being adsorbed and concentrated on biochar's pore, depending on the properties of biochar (e.g., porosity) and the substrate (e.g., polarity) | i) Extensively occurs during various porous biochar involved adsorption | [42,61] |

| Ion exchange | Ion exchange refers to the exchange of ions between the biochar surface and the charged substrate in liquid | i) Between the SiO2 of biochar and ammonium-N ii) Between Ca2+, Na+, or K+ of biochar and Hg2+ iii) Between -COOH, -OH, or -FeOOH of biochar with Cr6+ |

[26,31,62] |

| Ligand exchange | Ligand exchange refers to the original ligand of a coordination compound of biochar being selectively substituted by other ligands in liquids, which is limited at high pH | i) Between -OH of biochar and PO43- in liquids ii) Between S- or O- containing groups of biochar with Cd2+ in liquids |

[30,50,63] |

| Hydrophobic interaction | Hydrophobic interaction refers to the interaction between aromatized, graphitized layers or the hydrophobically modified surface of biochar and hydrophobic substances | i) Extensively occurs between the hydrophobic surface of biochar and hydrophobic compounds ii) Between oleic acid-modified activated biochar and naphthalene |

[40,47] |

| Redox effects | Redox effects occur between biochar surfaces with oxidation or reduction capabilities and substrates in liquids | i) [Adsorbent]-Fe2+ + CrO42− + 4OH− + 4H2O → 3 Fe(OH)3 +Cr(OH)3 | [38] |

| Van der Waals forces | Van der Waals forces, a weaker electrostatic interaction than H-bonding, refer to non-directional and unsaturated interactions between the biochar surface and substrates in liquids | i) Between the biochar surface and neutral creatinine, urea, or uric acids | [26] |

| Models and equations | Nomenclature | Illustrations | Refs. | |

| Individual adsorption capacity | C0- the initial concentration of substrate Ce (mg/L)- the equilibrium concentration qe (mg/g)- the equilibrium adsorption amount V (L)- the reaction volume m (g)- the biochar’s mass |

Used for calculating the adsorption capacity of a single substrate | [72] | |

| Competitive adsorption capacity |

|

CA and CB (mg∙L−1)- the concentrations of A and B, respectively , , , and - the calibration constants for the A and B at their characteristic sorption wavelength (i.e., λ1 and λ2) and - the optical densities of λ1 and λ2, respectively |

Used for calculating the adsorption capacities of multiple substances | [45] |

| PFO kinetic model |

qt (mg/g)– adsorption capacity at time t K1 (min-1)– the PFO rate constant |

Describing the alteration rate of adsorption capacity over time is positively correlated to the gradient between the qe and qt (or instant free sites) | [14] | |

| PSO kinetic model | K2 (g/(mg min)) – the PSO rate constant | Describing the adsorption rate positively relates to the improved useful adsorption sites, while chemisorption is dominant and related to strong interaction (valency forces) of the target contaminant and biochar | [15] | |

| Elovich model |

α (mg/(g min))– the initial sorption constant β (g/mg)– the initial desorption constant |

Describing initial heterogeneous surface chemisorption. | [65] | |

| Langmuir isotherm model |

qm (mg/g)– the maximal adsorption capacity KL (L/mg)– the Langmuir constant related to the adsorption free energy |

Describing monolayer physisorption occurs at a specific homogeneous surface with fixed active site amounts and the same energy, and free of interactions among the uptake molecules and lateral interactions. RL values between 0-1 suggest favorable adsorption | [40] | |

| Freundlich isotherm model |

KF (L/mg)–adsorption bonding energy (or affinity parameter) 1/n– the adsorption intensity coefficient, indicating the adsorption driving force magnitude |

Describing non-ideal and reversible multilayer adsorption at heterogeneous surface sites, with exponentially decreased energy distribution, uneven adsorption enthalpy distribution, and improved surface coverage 0<1/n<1 (or high KF values) suggests favorable adsorption and high adsorption ability 1/n>1 suggests unfavorable adsorption n=1 suggests linear adsorption n=0 suggests unfavorable and irreversible adsorption |

[73] | |

| Temkin isotherm model | b (mol2/J2)- the adsorption free energy bT (kJ/mol)- the Temkin constant KT (l/g)- the equilibrium binding constant T (K)- the temperature of the adsorption system |

Describing the chemisorption on an uneven surface involves adsorbent–adsorbate interaction and the non-uniform and linearly decreased adsorption heat, neglecting the impact of extreme concentration values | [48] | |

| Redlich–Peterson isotherm models | KR (L/g) - Redlich-Peterson constant aR (L/mg(1–1/A)- Redlich Peterson constant θ- the exponent reflecting the heterogeneity of the adsorbent |

Describing the combined characteristics of both the Langmuir and the Freundlich models | [37] | |

| Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherm model |

|

KDR (mol2/J2)- a constant indicating the adsorption energy qDR (mg/g)- the adsorption capacity ES (kJ/mol) – a value crucial to clarify the adsorption mechanisms |

Describing whether the adsorption follows the micropore filling mechanism, which is a more general monolayer adsorption model than the Langmuir type. ES < 8 suggests a physisorption 8 <ES < 16 suggests an adsorption related to ion exchange ES > 16 suggests a chemisorption |

[39] |

| Weber and Morris model |

KP (mg/(g min1/2))– the intraparticle diffusion constant C – a constant related to the boundary layer thickness |

Describing three-step adsorption, i.e., the transfer of adsorbed substrates from liquids to the boundary layer, from the boundary layer to the biochar surface, and intraparticle diffusion into biochar. If the linear plot passes through the origin, intraparticle diffusion is the only controlling step. High intercept favors the adsorption | [55] | |

| Boyd model | Kbf (1/min)– liquid-film diffusion constant | Describing the transfer of adsorbed substrates from the liquids to the surface of the biochar. If the linear plot passes through the origin, film diffusion is the only rate-limiting step | [34] | |

| Thomas breakthrough curve model |

kTh (mL/(min mg))– the Thomas rate constant q0 (mg/g)– the adsorption capacity v (mL/min)– the feed flow rate |

This model is derived from the Langmuir isotherm and PSO models, describes the adsorption mainly being controlled by interface mass transfer instead of chemical interactions, and is commonly used to predict the column adsorption performance of biochar |

[65] | |

| Adams–Bohart breakthrough curve model |

kAB (L/(mg min))– the kinetic constant N0 (mg/L)– the saturation concentration z (cm) – the bed depth of the fixed bed column U0 (cm/min)– the superficial velocity |

Describing the adsorption rate is limited by external material transfer, the adsorption balance does not achieve instantaneously, and the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent is proportional to the adsorption kinetics, which is generally used to explain the relevance between Ct/C0 and t in the initiation of breakthrough curves (Ct/C0 ≤ 0.15) | [50] | |

| Arrhenius formula | A- the Arrhenius constant R (8.314 J/(K mol))- the universal gas constant |

Describing the effects of temperature on adsorption | [15] | |

| Van't Hoff equation | (L/g) is the distribution coefficient | Describing the effects of temperature on adsorption | [5] | |

| Gibbs free energy |

|

(kJ/mol)- the Gibbs free energy | Negative ΔG° values identify spontaneous adsorption. ΔG° values in the range of 0-20 kJ/mol suggest physisorption | [74] |

| Enthalpy and entropy |

(kJ/mol)- the adsorption enthalpy (kJ/mol)- the adsorption entropy |

Negative ΔH° values identify exothermic adsorption. ΔH value (67.74 kJ/mol) shows chemisorption. ΔH° of 40-800 kJ/mol and (2.1-40 kJ/mol identify chemisorption and physisorption, respectively. Negative ΔS° values indicate the entropy-decreasing adsorption, high orderliness, low molecule colliding, and low intramolecular and intermolecular degrees of freedom of adsorbed molecules |

[12] | |

| Strategies | Merits | Limitations |

| Conventional high-temperature heating (pyrolysis) | Most common and well-established method. Can use a variety of feedstocks. Higher temperatures (above 500°C) yield highly stable carbon and porous biochar with high fixed carbon content. Products (bio-oil, syngas, and biochar) can be used for energy. | Longer processing times (especially slow pyrolysis). Heat transfer can be slow and non-uniform, particularly in large reactors. Requires a significant amount of energy, especially to drive off moisture from wet biomass. |

| High-temperature heating under vacuum | Lower decomposition temperature and shorter processing time compared to atmospheric pyrolysis. This strategy can potentially increase bio-oil yield and improve product quality by quickly removing volatiles. | Increased complexity and cost due to the need for vacuum equipment. This strategy may require specialized reactor design. |

| Microwave Calcination (Pyrolysis) | Rapid and uniform heating due to direct energy transfer to the biomass. Shorter processing time and higher energy efficiency compared to conventional heating. Can produce biochar with enhanced microporous structure and surface functional groups. | Potential for hotspots and temperature non-uniformity in large-scale applications. Reactor design and precise control are more complex. |

| Hydrothermal synthesis (hydrothermal carbonization) | Uses wet biomass directly (no pre-drying needed), which is an advantage for high-moisture feedstocks. Operates at lower temperatures (180 to 250°C) under high pressure. Produced hydrochar is carbon-rich but often less stable than pyrolysis biochar. | Requires specialized equipment (autoclaves) to handle high pressure. Longer reaction times (hours to days). Hydrochar may have lower C-stability and surface area than high-temperature biochar. |

| Microwave hydrothermal synthesis | Combines the benefits of microwave heating with hydrothermal carbonization. Offers significantly reduced reaction time (hours to minutes) and homogeneous heating compared to conventional hydrothermal carbonization. Allows for rapid and precise process control. | Requires specialized microwave equipment designed for high-pressure hydrothermal conditions. Cost and scalability can be challenging. |

| Salt-melting method (molten salt pyrolysis) | Molten salts can act as pore-forming agents or activating agents to produce biochar with high specific surface areas and enhanced properties (e.g., magnetic biochar). The salt can often be recovered and reused, promoting sustainability. | Introduces a new chemical, i.e., salt, into the process, requiring a separation step to recover the salt and clean the biochar. Higher complexity and potential for secondary pollution if not properly managed. |

| Precursors of biochar | Pollutants | Wastewater | Fabrication conditions of biochar | Adsorption conditions | Surface area, pore size, total pore volume | Functional groups and mechanisms | Adsorption capacities | RE (%) | Refs. |

| Date seed | Carbendazim | Municipal wastewater | 550°C, 0.5 h, N2 atmosphere | 3 g biochar/L, pH 7, 40 min, 200 mL, 1 mg/L | 307.5 m2/g, 3.80 nm, 0.278 cm3/g | -OH, -COOH, -Ph π–π electron donor–acceptor interactions, π–π stacking, dipole–dipole interactions, pore filling, electrostatic attraction, H-bonding |

- | 88.7 | [4] |

| Linuron | 85.9 | ||||||||

| Corncob | N, P, K | Human urine | 600°C, anaerobic condition | 60 g biochar, 600 mL, 5 days | 1.7 m2/g, -, 0.0005 cm3/g | -OH, -COOH, C = C ion exchange, chemical interaction |

1200, 242.8, 43.7 mg/L | - | [27] |

| Biogas wastewater | 342.4, 105, 35 mg/L | ||||||||

| Groundnut shells, drumstick seeds, coconut fiber | BOD | Pharmaceutical wastewater | Groundnut shell: 500°C, 4 h; drumstick seeds: 600°C, 2 h; coconut fiber: 700°C, for 2 h | 35 g biochar mixture (1:1:1), 443.6 mg/L, pH 7, 25°C, 1.5 h | - | OH, -CH₃, C-H, C=C, C-OH, C=O - |

- | 72.1 | [72] |

| Coconut shells | Methylene blue | Dye wastewater | - | 20 mg Fe3O4/biochar /sodium alginate aerogel beads, 50 mL, 50 mg/L, 150 rpm, 25°C, 24 h, pH 7 | 152.5 m2/g, 2.60 nm, - | -OH, -COOH pro-filling, H-bonding, electrostatic interaction |

- | - | [5] |

| Rice husk | TC | Human urine | - | 0.1 g biochar/mL, 5 days | 4.63 m2/g, -, - | –OH, C-H, C-O, C=C H-bonding, ligand exchange, ion exchange, electrostatic interactions |

- | 60-80 | [26] |

| N, P, K | 236.5, 256.7, 4.6 mg/L | 50, 70, 80 | |||||||

| Peanut shell | Atrazine | Synthetic wastewater | 450°C, 4 h | 20 mg biochar, 25 mL, 20 mg/L, 150 rpm | 61.8 m2/g, 1.96 nm, 0.03 cm3/g | -OH, NH2, C-O, C=O, C-H, C=C, C-C π-π interactions, H-bonding |

2.8 mg/g | - | [6] |

| Coconut shell | Ammonium, nitrate, phosphate | Synthetic wastewater | - | 0.5 g biochar, 100 mL, 80 mg/L, 6 h, 80 rpm | - | C=C, C-O-C, C=O ion exchange, chemical interaction |

10.12, 7.51, 10.79 mg/g | - | [20] |

| Eucalyptus bar | Anthraquinon | Dye wastewater | 500°C, 1.5 h, anaerobic condition | 0.913 g biochar composite/L, 21 mg/L, pH 3.9, 117 min | 57.4m2/g, 1.48 nm, 0.41 cm3/g | Si-OH, Si-N, -COOH, -OH, C-O-C, C=O π–π interaction, electrostatic attraction, surface functional groups, chemisorption, pore-filling |

- | - | [48] |

| Walnut shell | Quinoline | Coking wastewater | 500°C, 2 h, N2 atmosphere | 10 mg KOH-activated biochar, 50 mg/L, 25°C, 50 mL | 969.8 m2/g, 2.34 nm, 0.4 cm3/g | C–O–C, C-O, C=OC-H, C-C, C=C–OH porous adsorption, π–π interaction, H-bonding, electrostatic attraction |

78.2 mg/g | - | [57] |

| Giant reed | Basic blue 41 | Textile wastewater | 10 °C /min at 600°C for 2 h, 5 L/min of N2 flow | 4 g biochar/L, 5.7 mg/L, 1 h | 429.0 m2/g, -, 0.09 cm3/g | C-H, C-O, C-C, C-OH, C=O, C=C electrostatic interactions |

5.14 mg/L | 90.3 | [39] |

| Color | 4 g biochar/L, 106 Pt–Co, 1 h | 83 Pt-Co | 89.3 | ||||||

| Turbidity | 4 g biochar/L, 48.55 NTU, 1 h | 33.7 NTU | 69.4 | ||||||

| COD | 4 g biochar/L, 928 mg/L, 1 h | 582 mg/L | 62.7 | ||||||

| Mandarin tree pruning | Dissolved organics | Olive mill wastewater | 600°C, N2 atmosphere | 5 g biochar, 6800 mg/L, 100 mL, 25°C, 160 rpm | - | - Precipitation, surface complexation, electrostatic interactions, π–π interactions |

- | 28 | [37] |

| 1 g biochar, 17 g/L, 100 mL, 25°C, 160 rpm | 140 mg/ g | - | |||||||

| Eucalyptus wood | Anthracene | Vehicle-wash wastewater | 450°C, 1 h, N2 atmosphere | 0.4 g biochar, 40 ppm, 1 h, pH 5, 50°C | 18.4 m2/g, 1.5 nm, 0.01 cm3/g | C-H, C=C, C=O Van der Waals dispersive contacts, electrostatic interactions, H- H-bonding |

- | 98.4 | [11] |

| Rice husks | Mn, Se, Fe ions | Urban wastewater | Biochar in 1 M NaOH (mBiochar/mNaOH, 2:1), 12 h, 25°C | 0.25 g NaOH-biochar/, biochar/HCl- biochar, 0.303 mg/L Mn, 0.116 mg/L Se, 0.390 mg/L Fe, 50 mL, 200 rpm, 10 h |

- | C≡C, C≡N, C=C, C-O, C-H, Si-O-Si electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, complexation, precipitation |

- | 76, 66, 66 | [40] |

| Biochar in 10% wt. HCl, 3 h, 500°C at 10 °C/min, 200, 8 h, mL/min of N2 flow | - | 30, 26, 59 | |||||||

| 350°C at 10 °C/min, 6 h, 200 mL/min of N2 flow | - | 3, 39, 48 | |||||||

| Garlic peel | Methylene blue | Industrial wastewater | 150°C at 5 °C/min, 2 h, vacuum atmosphere | 5 mg biochar, 20 mL, 50 mg/L, 1 h, 25°C | 5.46 m2/g, 1.49 nm, 0.18 cm3/g | O-H, C=O, C-O, C=C-H Electrostatic attraction, H-bonding, π-π stacking |

14.33 mg/g | - | [1] |

| Corn stover | Phosphate | Pig farm wastewater | 500°C, 2 h, N2 atmosphere | 0.2 g Ce-modified biochar, 100 mL, 24 h, 180 rpm, 25°C | 14.1 m2/g, 7.05 nm, - | -CH2-, -CH-, Ce-O surface precipitation, ligand exchange, complexation, electrostatic attraction |

27.96 mg/g |

43.3 | [30] |

| Lotus leaf | Be ion | Simulated beryllium mining wastewater | 600°C, 3 h | 0.05 g PO43−/NH4+ modified biochar, 50 mL, 35°C, pH 5.5, 16 h, 175 rpm | 4.927 m2/g, 3.86 nm | Phosphoric acid, ammonia, -OH surface complexation and precipitation, pore filling, |

40.38 g/kg | - | [75] |

| Palm leaves | Tetracycline | Synthetic wastewater | 500°C, 2 h, 10 °C/min under N2 atmosphere | 1 g biochar/L, 20 mL, 0.5 mg/L, 180 rpm, pH 5.7, 24 h, 25°C | 31.5 m2/g, 5.38 nm, 0.03 cm3/g | -COOH, -OH, C=O, C-O, C=C, C-H H-bonding, π-π interaction, electrostatic interaction, pore-filling |

- | 80 | [2] |

| Prosopis juliflora | Sulfamethoxazole | Industry wastewater | 600°C at 10 °C/min, 2 h, N2 atmosphere | 1 g biochar/L, pH 5, 5.3 mg/L, 2 h | 875 m2/g, -, - | -OH, -COOH, -Ph, C-N, C-H, C-Cl, C-O electrostatic interactions, H-bonding, π-π stacking |

- | 76.7 | [55] |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 g biochar/L, pH 5, 8.3 mg/L, 2 h | 80.4 | |||||||

| COD | 1 g biochar/L, pH 5, 2.5 g/L, 2 h | 79.4 | |||||||

| TOC | 1 g biochar/L, pH 5, 1.05 g/L, 2 h | 88.2 | |||||||

| Oil palm fronds | COD | Latex industrial wastewater | 300-438°C at 13 °C/min, 3 h | 15 g Biochar/L, 4 h, 150 mL | 68.98 m2/g, 1.68 nm, - | O-H, C=C, C-H, C-O, S=O, Si-O-Si, S-S Ion exchange, H-bonding |

- | 41.2 | [79] |

| Suspended solids | 87.6 | ||||||||

| Sulfate | 58.8 | ||||||||

| Sulfide | 56.8 | ||||||||

| Bamboo | Phosphate | Phosphate fertilizer plant wastewater | 900°C at 8 °C/min, 2 h, N2 atmosphere | Iron/CaO-modified biochar, 1660 mg/L, 48 h | 146.5 m2/g, 2.78 nm, 0.1 cm3/g | - Chemical precipitation |

- | ~100 | [58] |

| Fronds and leaves of date palm | Phenol | Synthetic primary-treated wastewater | 600°C at 8 °C/min, anaerobic condition | 0.1 g biochar, pH 6, 20 h, 800 mg/L, 50 mL, 200 rpm | 245.8 m2/g, 4.6 nm, 0.12 cm3/g | O-H, C=C, C-H, Si-O, -COOH π-π interactions, H-bonding, pore filling, electrostatic interaction |

241 mg/g | 60.3 | [74] |

| Synthetic secondary-treated wastewater | 0.1 g biochar, pH 6, 20 h, 52 mg/L, 50 mL, 200 rpm | 22.28 mg/g | 85.7 | ||||||

| Parthenium hysterophorus | Cr ion | Tannery wastewater | 500°C, 2 h | Fe3O4/biochar,85.13 mg/L | 237.4 m2/g, -, - | O-H, C-O-C, C-OH, Fe-O, Van der Waals forces, H- H-bonding, hydrophobic interactions |

- | 81.8 | [38] |

| Corn straw | Cr ion | Industrial wastewater | 500°C, 2 h, Ar atmosphere | 0.05 g Fe3O4/biochar, 32.8 mg/L, 3 h, pH 6 | 508.4 m2/g, 4.6 nm, 0.55 cm3/g | Fe–O, Fe–OOH, C=O, O–H Surface physisorption, pore filling, and electrostatic interaction |

- | 72.6 | [31] |

| Citrus trees | Tetracycline | Industrial wastewater | - | 3.5 g biochar, 50 mL, pH 4, 90 mg/L, 20°C | 364.9 m2/g, 1.08 nm, 0.2 cm3/g | O-H, C=C, C=O, C-H, C-Cl π-π interaction |

- | 95 | [12] |

| Corncob | Ammonia | Livestock wastewater | 450°C for 1.5 h, 4 °C/min | 0.3 g, 50 mL, 6.2 mg/L pH 12, 1.5 h | - | - | - | 83.98 | [96] |

| Corn Stalks | COD | Hospital wastewater | 400-500°C | 56.0 mg/L | - | - | - | 57.1 | [29] |

| BOD | 46.8 mg/L | 56.8 | |||||||

| Wheat straw | Inorganic-N | Simulated agricultural wastewater | 450°C at 5 °C/min, 5 h, 400 mL/min of N2 flow | 10 g Mg-modified biochar/L, 24 h, 250 mL, 25°C, 80 rpm | 23.4 m2/g, -, 0.062 cm3/g | C=C, -OH, -Ph -NH2, -COOH H-bonding, π-π/n-π interaction |

4.44 mg/g | - | [46] |

| Palm bunch | Methyl paraben | Secondary wastewater effluent | 450°C at 10 °C/min, 0.5 h, 400 mL/min of N2 flow | H2SO4-activated biochar | 60.3 m2/g, -, 0.54 cm3/g | C=C, -OH, C=O, S=O, C≡C Channel diffusion, H bonding, Van der Waals force, n-π/π-π interaction |

- | 80.3 | [97] |

| Carbamazepine | 79.9 | ||||||||

| Ibuprofen | 70.2 | ||||||||

| Triclosan | 74.3 | ||||||||

| Rotten sugarcane bagasse | Pb ion | Stimulated wastewater | 600°C, 2 h, air atmosphere | 30 mg biochar, 50 mg/L, pH 5 | 391.9 m2/g, 20.9 nm, 0.532 cm3/g | -COOH, CHO, C=O, C-H, C=C, O-C=O Ion exchange, surface complexation/function group coordination, precipitation, π-π interaction |

- | 97.3 | [49] |

| Cu ion | 99.8 | ||||||||

| Cr ion | 100 | ||||||||

| Wheat straw | COD | Dye industry wastewater | 300-500°C | 2.5 g biochar/L, 25 mL, pH 7.62, 150 rpm | - | C=C, C=O, C-H, C-O-C, -OH, -COOH Ion exchange, Surface physisorption, electrostatic interaction, complexation |

- | 62 | [22] |

| Rice husk | Pb ion | Industrial wastewater | 500°C at 5 °C/min, 2 h, N2 atmosphere | Biochar, 35.7 mg/L, pH 6.68, 100 mL | 63 m2/g, -, 0.381 cm3/g | C-H, C=O, -OH, C-O Ion exchange, surface physisorption, electrostatic interaction, complexation |

- | 63.8 | [25] |

| Auricularia auricula spent substrate | Cd ion | Electroplating wastewater | 500°C, 2 h, anoxic conditions | 0.1 g CS2-modified biochar/L, 5.21 mg/L Cd2+, 1.11 mg/L Cu2+, 48.72 mg/L Zn2+, 25°C, pH 5.59, 2 h | 2.54 m2/g, 13.4 nm, 0.009 cm3/g | C-S, -OH, S=C=S, C=O, -NH2 Complexation, precipitation |

14.01 mg/g | - | [50] |

| Cu ion | 13.56 mg/g | ||||||||

| Zn ion | 50.19 mg/g | ||||||||

| Coffee husk | Ammonium | Domestic wastewater | 350°C, 1 h | 20 g biochar/L, 130 rpm, 6 h, 108 mg/L, pH 7.4 | 0.43 m2/g, -, - | -OH, C-H, C=O, C=C, -COOH Complexation, ion exchange, H-bonding, electrostatic attraction |

- | 20 | [84] |

| Maize stalk, black gram, pine needle, Lantana camara | COD | Municipal wastewater | 600°C at 10 °C/min, 4 h | 5 g steam-activated biochar, 5 days | 38.9-43.9 m2/g, 2.74-3.96 nm, 2.47-3.99 cm3/g | -COOH, -OH, -NH2 Electrostatic interaction, precipitation, surface complexation |

- | 88-91 | [35] |

| TSS | 81-85 | ||||||||

| Ammonia | 87-91 | ||||||||

| Total K&N | 59-69 | ||||||||

| Total K | 78-88 | ||||||||

| As ion | 79-87 | ||||||||

| Cd ion | 53-95 | ||||||||

| Cr ion | 83-88 | ||||||||

| Pb ion | 78-95 | ||||||||

| Zn ion | 90-95 | ||||||||

| Cu ion | 93-96 | ||||||||

| Rice straw | COD | Livestock wastewater | 300°C, 6 h | Batch mode, 4 g biochar/L, pH 9 | 35.4 m2/g, -, 0.36 cm3/g | - Polarity, hydrophobic/aromatic interaction, and molecular size |

- | 40 | [85] |

| BOD | Batch mode, 4 g biochar/L, pH 9 | 40 | |||||||

| COD | Column mode, 373 mg/L COD, 105 min | 79 | |||||||

| BOD | Column mode, 240 mg/L BOD, 105 min | 84 | |||||||

| Jujube seeds | TSS | Electroplating industrial wastewater | Jujube seeds/H2SO4, 1:3 for 4 h, sonication 20 min at 24 kHz | 2 g biochar/L, pH 1 h, 30°C, 20 mg/L | 48.32 m2/g, -, 0.16 cm3/g | -OH, C=C, C=O, C-OH, La-OP-, -CO= Ligand exchange, electrostatic attraction, complexation |

- | 10 | [78] |

| TDS | 2 g biochar/L, pH 1 h, 30°C, 2.8 g/L | 0.79 | |||||||

| Ni ion | 2 g biochar/L, pH 1 h, 30°C, 15 mg/L | 99.9 | |||||||

| Zn ion | 2 g biochar/L, pH 1 h, 30°C, 20 mg/L | ~100 | |||||||

| Cu ion | 2 g biochar/L, pH 1 h, 30°C, 40 mg/L | ~100 | |||||||

| Cr ion | 2 g biochar/L, pH 1 h, 30°C, 70 mg/L | ~100 | |||||||

| Coconut husk | NO3-N and NO2-N | Slaughterhouse wastewater | 700°C, 6 h, under N2 atmosphere | 1.5 g biochar, 26°C, pH 7.35, 50 mL, 120 rpm, 2 h | 6.84 nm | -OH, C=C, Si-O-Si ligand exchange, electrostatic attraction, complexation |

0.2-13 mg/g | - | [78] |

| Rice husk | 1.97 nm | 0.2-12 mg/g | |||||||

| Coffee husk | 1.63 nm | 0.2-12 mg/g | |||||||

| Pomelo peel | Tetracycline | Synthetic swine wastewater | 400°C at 10 °C/min, 2 h | 80 mg KOH-activated biochar/L, 10 mg/L, pH 7, 21°C, 75 h | 2457.4 m2/g, -, 1.14 cm3/g | C≡C, C≡N, C-C, C=C, C-H, C-O-C, C=O π-π electron donor–acceptor interaction, electrostatic interaction, pore filling |

- | 85.0 | [41] |

| Oxytetracycline | 82.2 | ||||||||

| Chlortetracycline | 96.6 | ||||||||

| Corn straw | TS | Swine wastewater | 500°C, 1 h, N2 atmosphere | Biochar or NaOH-activated biochar, 10.6 g/L TS, 0.3 g/L TVSS, 2985.6,1908.2, 1270.3, 981.4, 85.7, 4138.6, 655.9, 0.6, 2.7, 1.1, 6.1, 0.5, and 0.2 mg/L for TC, TOC, TV, NH4+-N, TP, COD, K, Mg, Cu, Zn, Ca, Fe, and Mn, respectively |

- | - H-bonding, electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, hydrophobic interaction |

- | 50-42 | [42] |

| TVSS | 67-67 | ||||||||

| TC | 53-72 | ||||||||

| TOC | 55-73 | ||||||||

| TN | 18-33 | ||||||||

| NH4+-N | 22-32 | ||||||||

| TP | 19-25 | ||||||||

| COD | 20-26 | ||||||||

| K ion | 39-67 | ||||||||

| Mg ion | 33-83 | ||||||||

| Cu ion | 59-41 | ||||||||

| Zn ion | 27-73 | ||||||||

| Ca ion | 30-54 | ||||||||

| Fe ion | 80-80 | ||||||||

| Mn ion | 100 | ||||||||

| Platanus balls | Phosphate | Actual wastewater | 600°C at 10 °C/min, 2 h, N2 atmosphere | Column mode, 1 g La-modified biochar | 77.01 m2/g | LaO-, O-PO-, P-O electrostatic adsorption, ligand exchange, complexation |

14.85 g/g | - | [63] |

| Bagasse | Pb ion | Battery manufacturing industry wastewater | 300°C, 2.5 h | 5 g biochar, pH 5, 2.5 h, 25°C, 2.393 mg/L | 12.38 m2/g | C=O, C=C, C-H, C-N, -COO-, -COOH, -Ph-OH Complexation, ion exchange |

12.74 mg/g | 75.4 | [54] |

| Potato peel | Cu ion | Industrial wastewater | 450°C, 6 L/min of N2 flow | 0.25 g chitosan-modified biochar, 4 h | - | -NH2 - |

1.117 mg/L | - | [86] |

| Pb ion | 0.506 mg/L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).