Submitted:

26 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

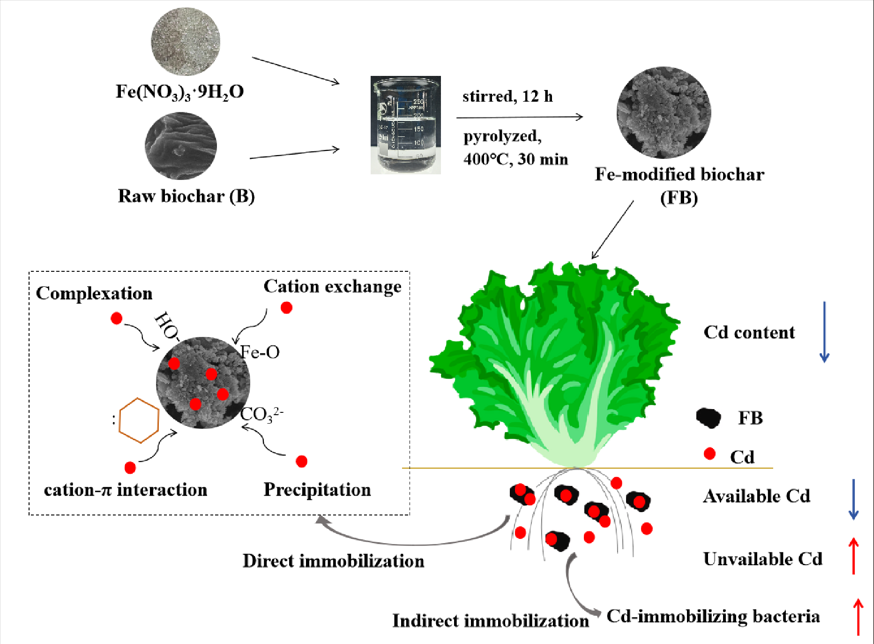

2.1. Synthesis and Screening of Absorbent

2.2. Characterization of Biochar

2.3. Pot Experiment

2.4. Plant Sample Analysis

2.5. Soil Sample Analysis

2.6. High-Throughput Sequencing

3. Results

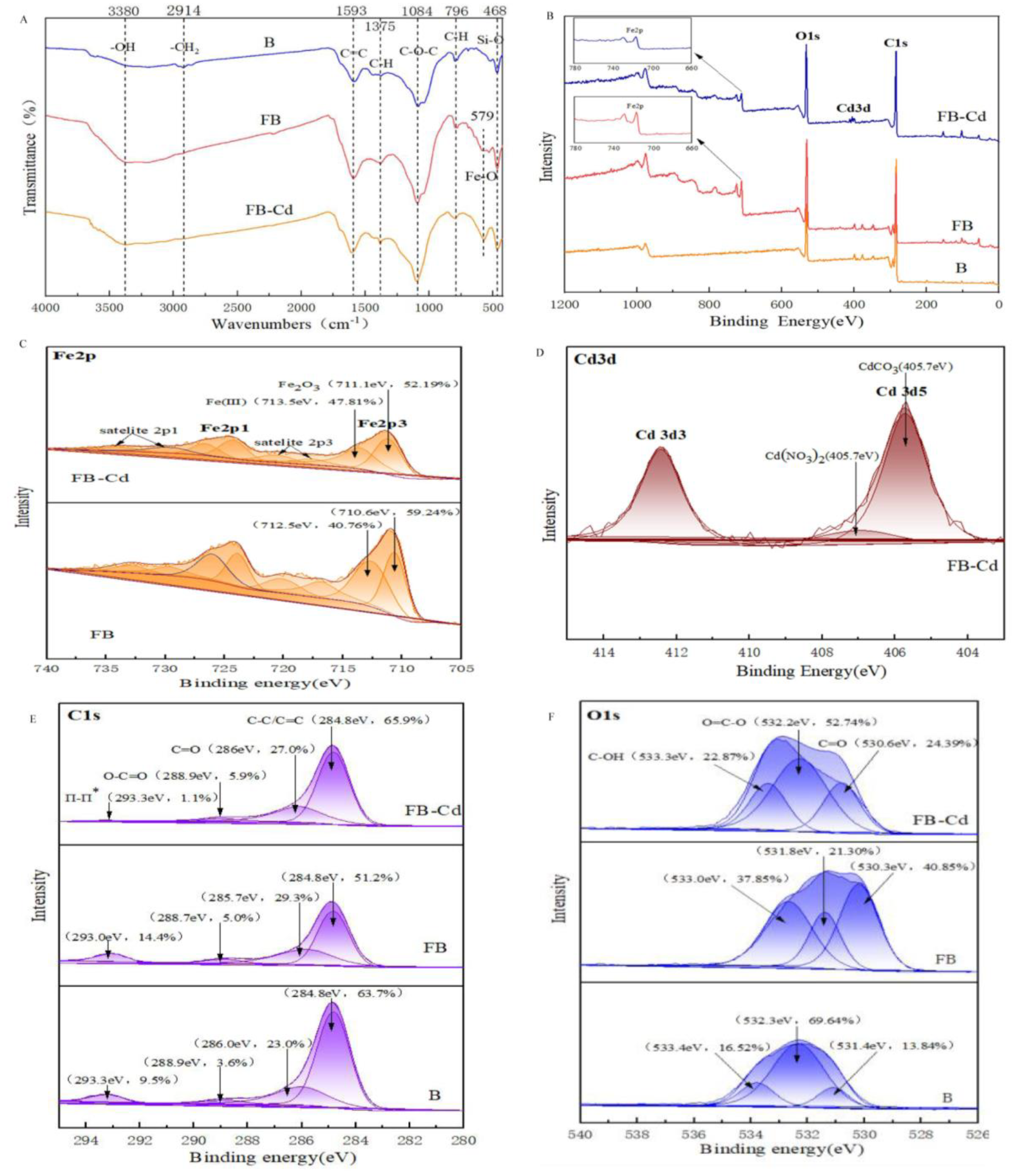

3.1. Selection and Characterization of Modified Biochar

3.2. Mechanism for Cd Immobilization by Fe-Modified Biochar

3.3. Soil Physiochemical Properties

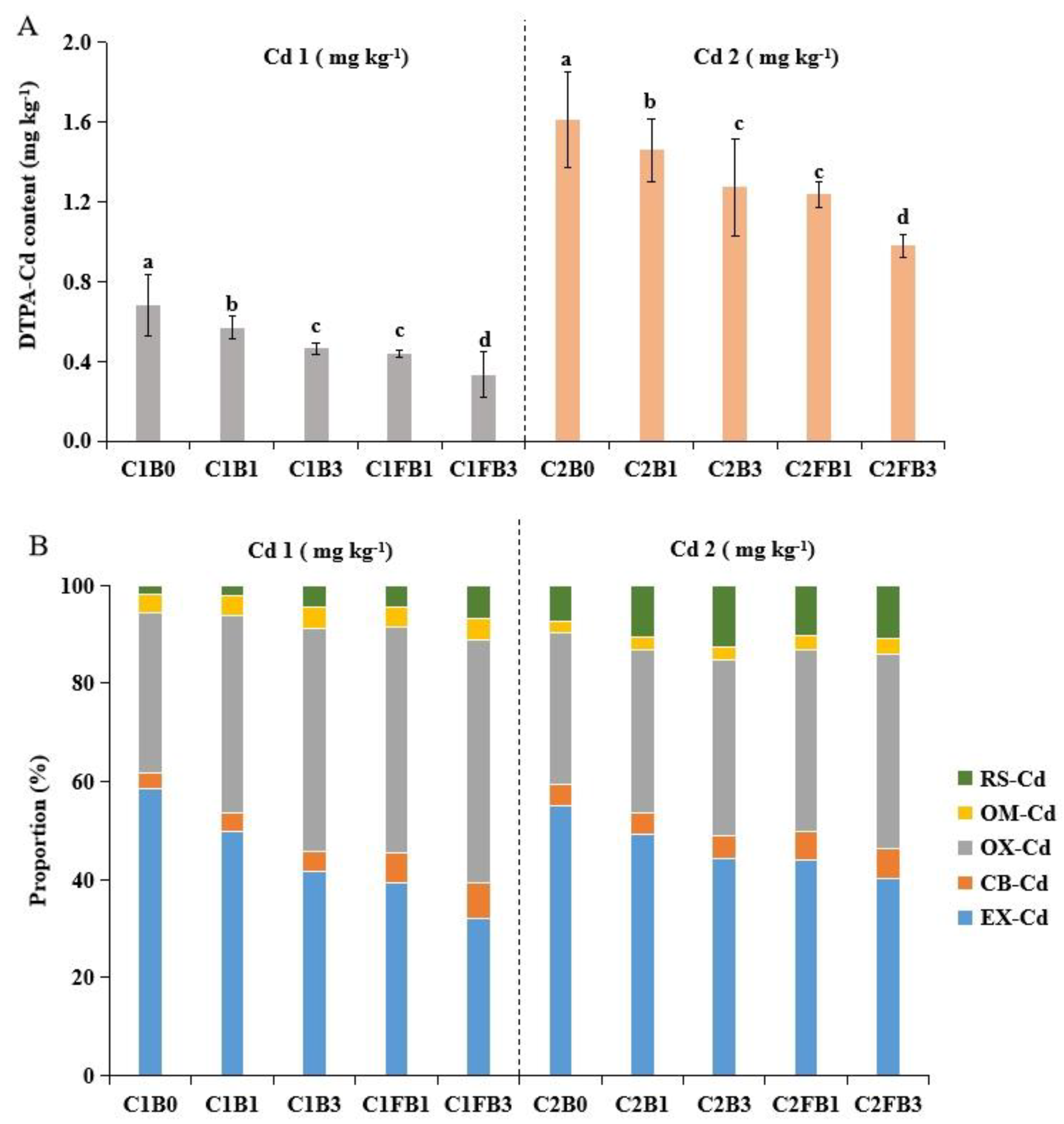

3.4. Soil Cd Bioavailability and Fractionation

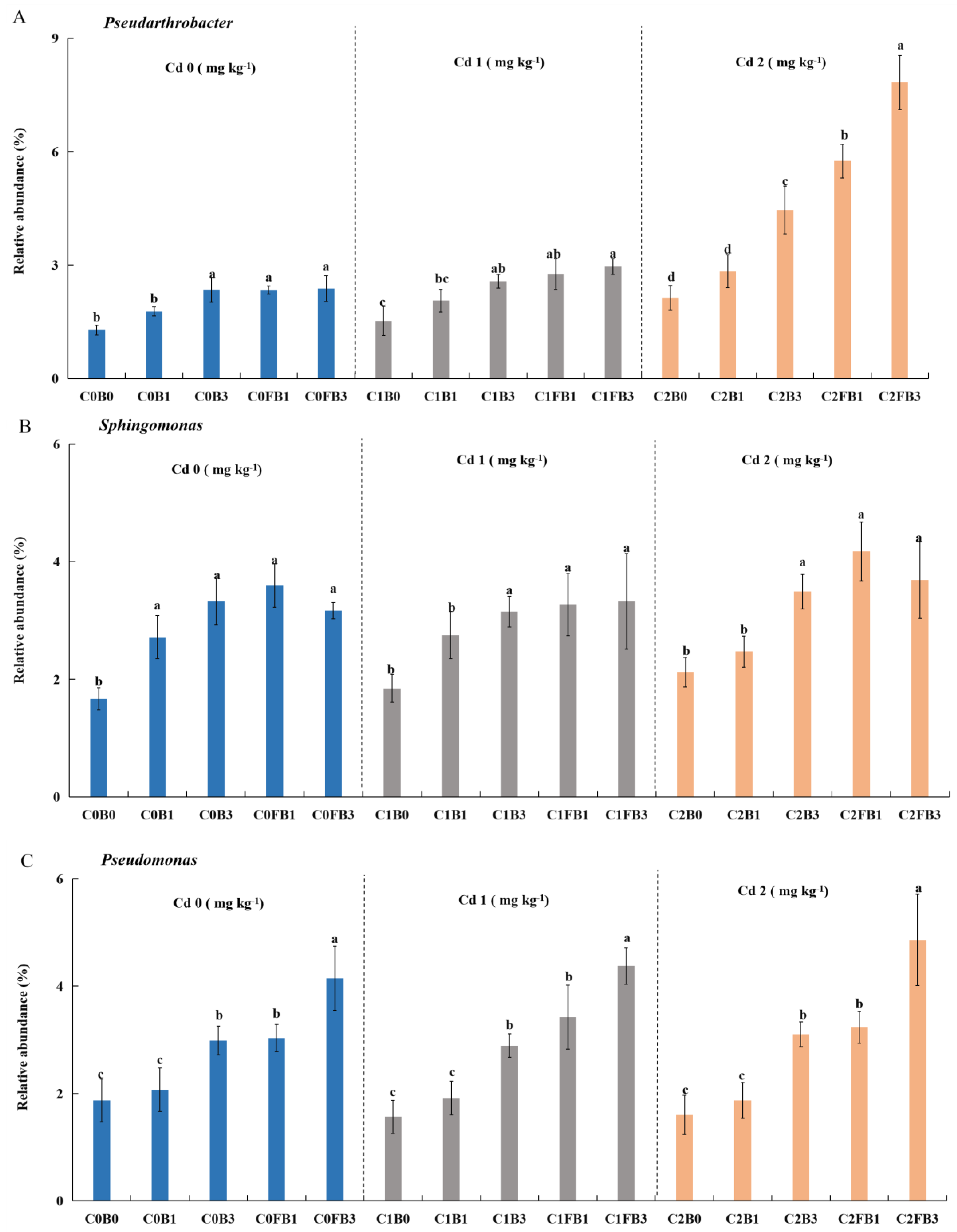

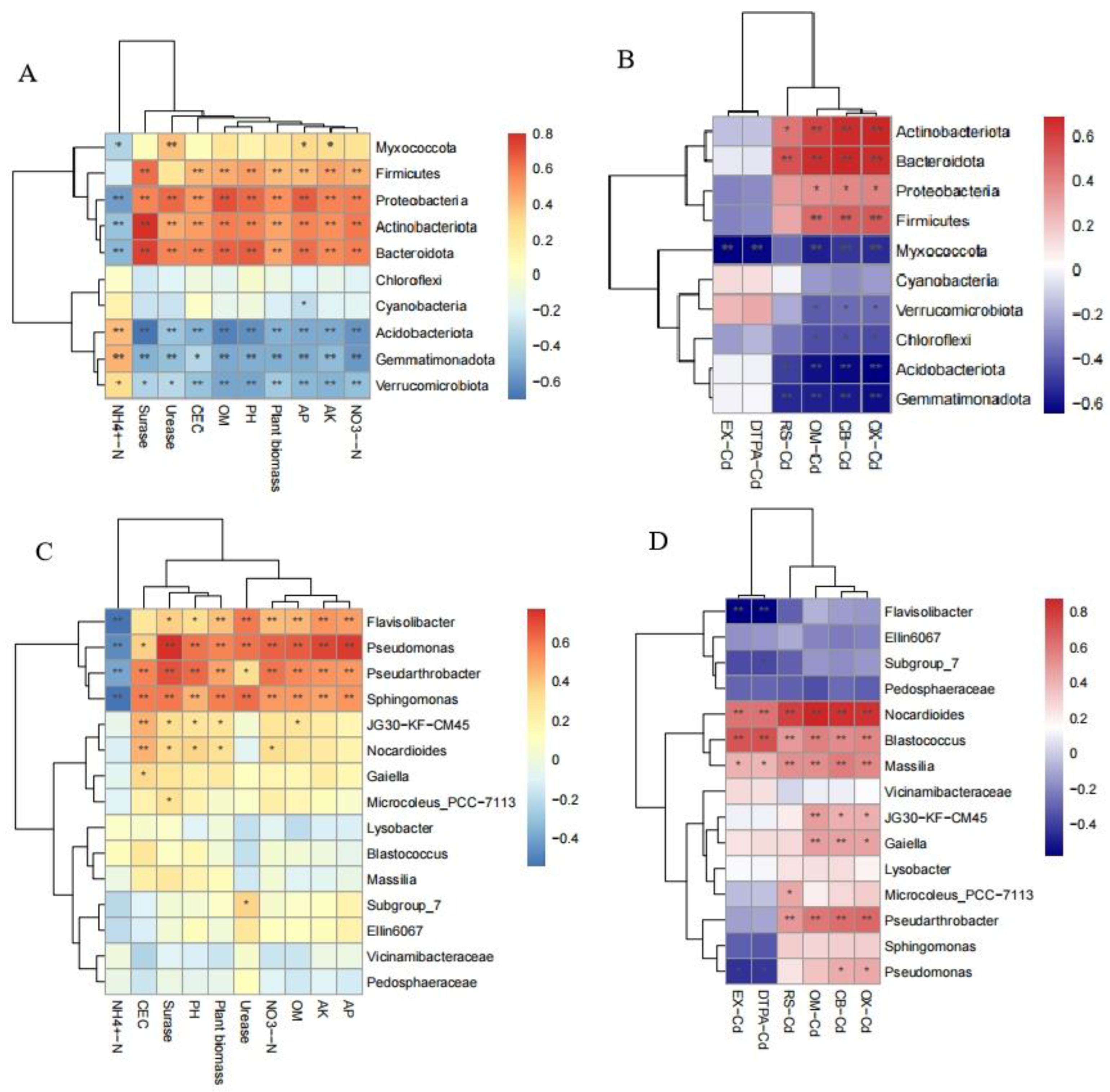

3.5. Soil Microbial Communities

3.6. Lettuce Growth and Physiological Parameters

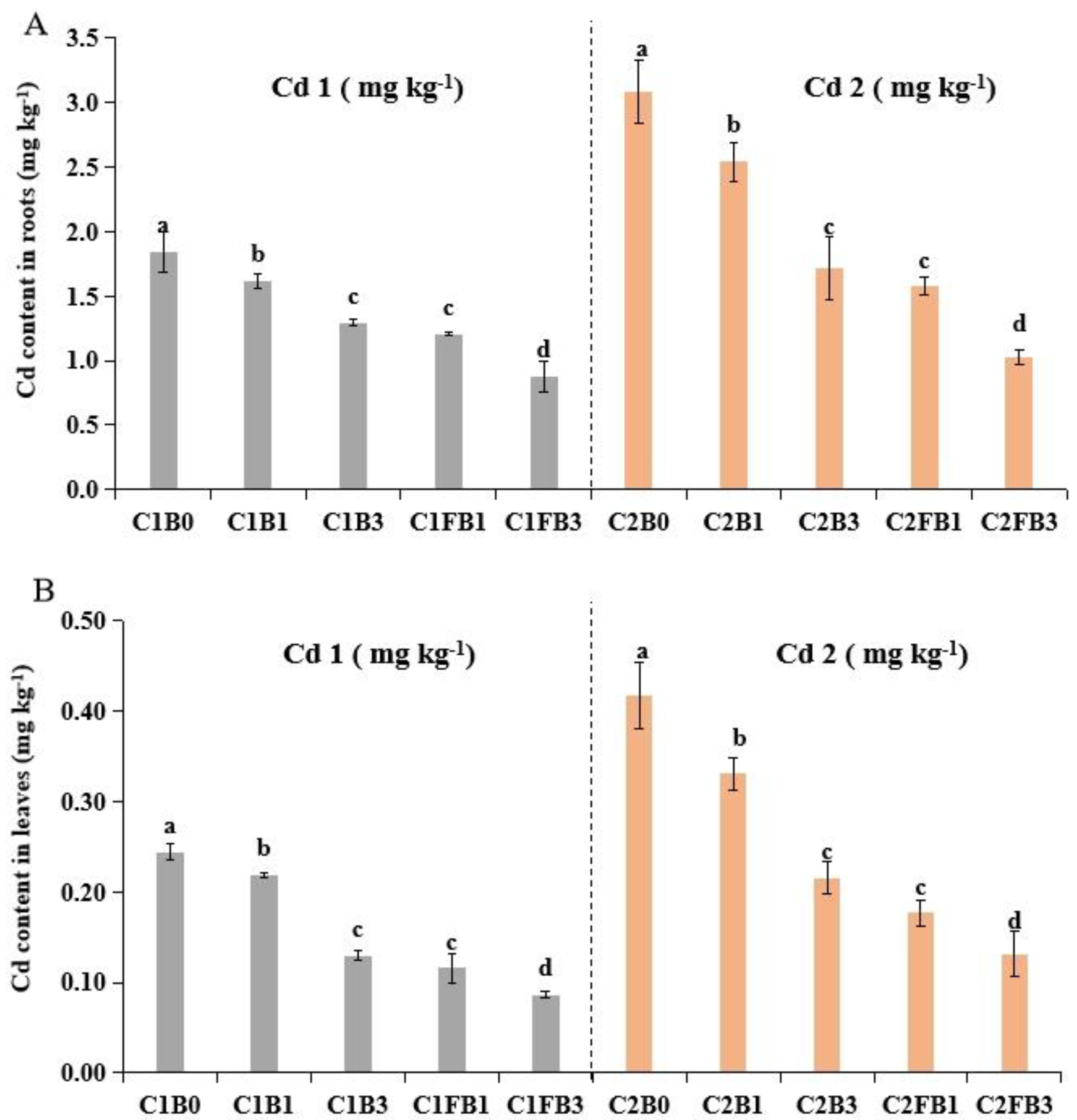

3.7. Lettuce Cd Uptake

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamid: Y.; Tang, L.; Hussain, B.; Usman, M.; Lin, Q.Rashid, M.S.;He, Z.; Yang, X. Organic soil additives for the remediation of cadmium contaminated soils and their impact on the soil-plant system: A review. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 707: 136121.

- Haider,F.U.; Liqun, C.; Coulter, J.A.; Cheema, S.A.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Wenjun, M.; Farooq, M.Cadmium toxicity in plants: Impacts and remediation strategies. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2021, 211: 111887. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Zhang, Q.C.; Yan, C.A.; Tang, G.Y.; Zhang, M.Y.; Ma, L.Q.; Gu, R.H.; Xiang, P.Heavy metal(loid)s in agriculture soils, rice, and wheat across China: Status assessment and spatiotemporal analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 2023a. 882: 163361. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.M.; Fu, R.B.; Wang, J.X.; Shi, Y.X.; Guo, X.P.Chemical stabilization remediation for heavy metals in contaminated soils on the latest decade: Available stabilizing materials and associated evaluation methods-A critical review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021. 321: 128730. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Du, Y.; Teng, G.; Wu, Z.Functional biochar fabricated from waste red mud and corn straw in China for acidic dye wastewater treatment. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 320: 128887. [CrossRef]

- Qianqian, M.; Haider, F.U.; Farooq, M.; Adeel, M.; Shakoor, N.; Jun, W.; Jiaying, X.; Wang, X.W.; Panjun, L.; Cai, L.Selenium treated foliage and biochar treated soil for improved lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) growth in Cd-polluted soil. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022, 335: 130267. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Liu, Q.; Li, M.; Yuan, X.Y.; Uchimiya, M.; Wang, S.W.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ji, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.Rhizospheric pore-water content predicts the biochar-attenuated accumulation, translocation, and toxicity of cadmium to lettuce. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2021b, 208: 111675. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.M.; Mosa, A.; Niazi, N.K.; Antoniadis, V.; Shahid, M.; Song, H.; Kwon, E.E.; Rinklebe, J.Removal of toxic elements from aqueous environments using nano zero-valent iron- and iron oxide-modified biochar: a review. Biochar. 2022, 4: 24. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.Adsorption characteristics and mechanisms of Cd(II) from wastewater by modified chicken manure biochar. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2024, 31: 3800-3814. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Hong, M.; Li, H.; Ye, Z.; Gong, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Q.; Tan, Z.Contributions and mechanisms of components in modified biochar to adsorb cadmium in aqueous solution. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 733: 139320. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, H.; Gu, J.F.; Huang, F.; Yang, W.J.; Wang, S.L.; Yuan, T.Y.; Liao, B.H.Effects of nano-Fe3O4-modified biochar on iron plaque formation and Cd accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environmental Pollution. 2020a, 260: 113970. [CrossRef]

- Algethami, J.S.; Irshad, M.K.; Javed, W.; Alhamami, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.Iron-modified biochar improves plant physiology, soil nutritional status and mitigates Pb and Cd-hazard in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Frontiers in Plant Science. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, A.; Du, W.; Mao, L.; Wei, Z.; Wang, S.; Yuan, H.; Ji, R.; Zhao, L.Insight into the interaction between Fe-based nanomaterials and maize (Zea mays) plants at metabolic level. Science of the Total Environment. 2020b, 738: 139795. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, D.; Wu, Z.; Peng, A.; Niazi, N.K.; Trakal, L.; Sakrabani, R.; Gao, B.; Wang, H.; Wu, W.Lead and copper-induced hormetic effect and toxicity mechanisms in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) grown in a contaminated soil. Science of the Total Environment. 2020a, 741: 140440. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, X.; Liu, F.; Hu, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, P.; Li, J.; Ji, P.Potential of a novel modified gangue amendment to reduce cadmium uptake in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2021, 410: 124543. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Lu, X.; Xia, T.Poly-γ-glutamic acid-producing bacteria reduced Cd uptake and effected the rhizosphere microbial communities of lettuce. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2020, 398: 123146. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Y.; Lobo, M.G.; González, M.Determination of vitamin C in tropical fruits: A comparative evaluation of methods. Food Chemistry. 2006, 96: 654-664. [CrossRef]

- Kayaalp, N.; Ersahin, M.E.; Ozgun, H.; Koyuncu, I.; Kinaci, C.A new approach for chemical oxygen demand (COD) measurement at high salinity and low organic matter samples. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2010, 17: 1547-1552. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; He, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Kong, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hu, R.Biochar amendment ameliorates soil properties and promotes Miscanthus growth in a coastal saline-alkali soil. Applied Soil Ecology. 2020, 155: 103674. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Gao, P.; Li, X.; Ji, P.Possibility of using modified fly ash and organic fertilizers for remediation of heavy-metal-contaminated soils. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 284: 124713. [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Campbell, PG.; Bisson, M.Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Analytical chemistry. 1979, 51: 844-851. [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Keeney, D.R.Steam distillation methods for determination of ammonium, nitrate and nitrite. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1965, 32: 485-495. [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R.Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011, 108: 4516-4522. [CrossRef]

- Sun. R.; Ding, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Li, K.; Ye, X.; Sun, S. Mitigating nitrate leaching in cropland by enhancing microbial nitrate transformation through the addition of liquid biogas slurry. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 2023, 345: 108324. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Yun, W.; Luo, B.; Chai, R.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, X.; Su, X. Changes in phosphorus mobilization and community assembly of bacterial and fungal communities in rice rhizosphere under phosphate deficiency. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2022b, 13:953340. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Tong, C. Bacterial community diversity of traditional fermented vegetables in China. LWT. 2017, 86: 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73:5261 - 5267. [CrossRef]

- Yang. T.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Qin, X.; Zhao, L. Adsorption characteristics and the removal mechanism of two novel Fe-Zn composite modified biochar for Cd(II) in water. Bioresource Technology. 2021b, 333: 125078. [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, K.B.; Hunt, P.G.; Uchimiya, M.; Novak, J.M. Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physicochemical characteristics of biochar. Bioresource Technology. 2012, 107: 419-428. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, H.Y.; Li, F.; Liu, T.; Wu, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X. Enhanced immobilization of arsenic and cadmium in a paddy soil by combined applications of woody peat and Fe(NO3)3: Possible mechanisms and environmental implications. Science of the Total Environment. 2019b, 649: 535-543. [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Song, X.; Tao, L.; Sarkar, B.; Sarmah, A.K.; Zhang, W.; Lin, Q.; Xiao, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Novel Fe-Mn binary oxide-biochar as an adsorbent for removing Cd(II) from aqueous solutions. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2020, 389: 124465. [CrossRef]

- Al-Swadi, H.A.; Al-Farraj, A.S.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Ahmad, M.; Usman, A.R.; Ahmad. J.; Mousa, M.A.; Rafique, M.I.; Impacts of kaolinite enrichment on biochar and hydrochar characterization, stability, toxicity, and maize germination and growth. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14: 1259.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Xiong, R.; Fu, D.; He, C.; Lai, B.; Ma, J. Enhanced degradation of Bisphenol AF by Fe/Zn modified biochar/ferrate(VI): Performance and enhancement mechanism. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2023, 11: 111582. [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Li, C.; Parikh, S.J. Simultaneous removal of arsenic, cadmium, and lead from soil by iron-modified magnetic biochar. Environmental Pollution. 2020, 261: 114157. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Xu, W.; Khan, S.B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Su, X.; Lin, Z. Preparation of sludge biochar rich in carboxyl/hydroxyl groups by quenching process and its excellent adsorption performance for Cr(VI). Chemosphere. 2021, 285: 131439. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Du, Y.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, J. Adsorption and coadsorption mechanisms of Cr(VI) and organic contaminants on H3PO4 treated biochar. Chemosphere. 2017, 186: 422-429. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Ma, S.; Xu, S.; Duan, R.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, P. Hierarchically porous magnetic biochar as an efficient amendment for cadmium in water and soil: Performance and mechanism. Chemosphere, 2021. 281: 130990. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Luo, G.; He, S.; Deng, F.; Pang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yao, H. Efficient removal of elemental mercury by magnetic chlorinated biochars derived from co-pyrolysis of Fe(NO3)3-laden wood and polyvinyl chloride waste. Fuel. 2019, 239: 982-990. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Cheng, K.; Li, J.S.; Tsang, D.C.W. Corn straw-derived biochar impregnated with α-FeOOH nanorods for highly effective copper removal. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2018. 348: 191-201. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Xu Z, Feng Q, Yao D, Yu J, Wang D, Liu Y, Zhou N, Zhong M (2018) Effect of pyrolysis condition on the adsorption mechanism of lead, cadmium and copper on tobacco stem biochar. Journal of Cleaner Production 187: 996-1005.

- Zhu, Y.; Yi, B.; Hu, H.; Zong, Z.; Chen, M.; Yuan, Q. The relationship of structure and organic matter adsorption characteristics by magnetic cattle manure biochar prepared at different pyrolysis temperatures. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2020, 8: 104112. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Sun, P. Fenton-like oxidation of antibiotic ornidazole using biochar-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron as heterogeneous hydrogen peroxide activator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health .2020b, 17: 1324. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.; Pang, Y.; Hao, Z.; Hu, M.; Qiu, R.; Chen, Z. Enhanced adsorption of tetracycline by an iron and manganese oxides loaded biochar: Kinetics, mechanism and column adsorption. Bioresource Technology. 2021, 320: 124264. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ding, F.; Huang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Zhao, P.; Men, S. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of Cd (II) by modified coal-based humin. Environmental Technology & Innovation. 2021a, 23: 101699. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Huang, S.; Laird, D.A.; Wang, X.; Meng, Z. Adsorption behaviour and mechanisms of cadmium and nickel on rice straw biochars in single- and binary-metal systems. Chemosphere. 2019, 218: 308-318. [CrossRef]

- Teng, D.; Zhang, B.; Xu, G.; Wang, B.; Mao, K.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Feng, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H. Efficient removal of Cd(II) from aqueous solution by pinecone biochar: Sorption performance and governing mechanisms. Environmental Pollution. 2020, 265: 115001. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Cai, C.; Chi, H.; Reid, B.J.; Coulon, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y. Remediation of cadmium and lead polluted soil using thiol-modified biochar. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2020, 388: 122037. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Han, L. Qualitative and quantitative correlation of physicochemical characteristics and lead sorption behaviors of crop residue-derived chars. Bioresource Technology. 2018, 270: 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi. M.K.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, T.; Awasthi, S.K.; Duan, Y.; Varjani, S.; Pandey, A.; Zhang, Z. Role of compost biochar amendment on the (im)mobilization of cadmium and zinc for Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L.) from contaminated soil. Journal of Soils and Sediments. 2019, 19: 3883-3897. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.; Zia ur Rehman, M.; Ali, S.; Qayyum, M.F.; Naeem, A.; Ayub, M.A.; Anwar, M.; Iqbal, A.; Rizwan, M. Comparative effectiveness of different biochars and conventional organic materials on growth, photosynthesis and cadmium accumulation in cereals. Chemosphere. 2019, 227: 72-81. [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Yin, S.; Suo, F.; Xu, Z.; Chu, D.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, L. Biochar and fertilizer improved the growth and quality of the ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L.) shoots in a coastal soil of Yellow River Delta, China. Science of the Total Environment. 2021, 775: 144893. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; DeLuca, T.H.; Cleveland, C.C. Biochar additions alter phosphorus and nitrogen availability in agricultural ecosystems: A meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment. 2019, 654: 463-472. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, N.; Cao, T.; An, Z.; Yang, X.; He, T.; Yang, T.; Meng, J. Maize straw is more effective than maize straw biochar at improving soil N availability and gross N transformation rate. European Journal of Soil Science, 2023. 74: 13403. [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Huang, B.; Fernández-García, V.; Miesel, J.; Yan, L. Biochar and Rhizobacteria amendments improve several soil properties and bacterial diversity, Microorganisms. 2020, 8: 502. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Ren, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, L.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, A. Physicochemical features, metal availability and enzyme activity in heavy metal-polluted soil remediated by biochar and compost. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 701: 134751. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, X.; Zheng, S. Cd immobilization and soil quality under Fe–modified biochar in weakly alkaline soil. Chemosphere. 2021, 280: 130606. [CrossRef]

- Si, T.; Yuan, R.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bian, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Joseph, S.; Li, L.; Pan, G. Enhancing soil redox dynamics: Comparative effects of Fe-modified biochar (N–Fe and S–Fe) on Fe oxide transformation and Cd immobilization. Environmental Pollution. 2024, 347: 123636. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, C.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, Z. The addition of degradable chelating agents enhances maize phytoremediation efficiency in Cd-contaminated soils. Chemosphere. 2021, 269: 129373. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gong, P.; Sun, Y.; Qin, Q.; Song, K.; Ye, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, B.; Xue, Y. Modified chicken manure biochar enhanced the adsorption for Cd2+ in aqueous and immobilization of Cd in contaminated agricultural soil. Science of the Total Environment. 2022a, 851: 158252. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xiao, Q.; Li, B.; Zhou, T.; Cen, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Insights into remediation of cadmium and lead contaminated-soil by Fe-Mn modified biochar. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2024, 12: 112771. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Tao, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, J. Changes in heavy metal bioavailability and speciation from a Pb-Zn mining soil amended with biochars from co-pyrolysis of rice straw and swine manure. Science of the Total Environment. 2018, 633: 300-307. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Tang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Q.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, M. Characterization of goethite-fulvic acid composites and their impact on the immobility of Pb/Cd in soil. Chemosphere. 2019, 222: 556-563. [CrossRef]

- Moradi, N.; Karimi, A. Fe-Modified common reed biochar reduced cadmium (Cd) mobility and enhanced microbial activity in a contaminated calcareous soil. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2021, 21: 329-340. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Qin, X.; Zhao, L. An efficient biochar synthesized by iron-zinc modified corn straw for simultaneously immobilization Cd in acidic and alkaline soils. Environmental Pollution. 2021c, 291: 118129. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, L.; Lesueur, D.; Robin, A.; Robain, H.; Wiriyakitnateekul, W.; Bräu, L. Impact of biochar application dose on soil microbial communities associated with rubber trees in North East Thailand. Science of the Total Environment. 2019, 689: 970-979. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Song, X.; Yrjälä, K.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Qin, H. Biochar mitigates the effect of nitrogen deposition on soil bacterial community composition and enzyme activities in a Torreya grandis orchard. Forest Ecology and Management. 2020c, 457: 117717. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Dai, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Huang, F.; Mei, C.; Huang, S.; Liu, C.; Wang, P.; Xiao, R. Effect of rice straw biochar on three different levels of Cd-contaminated soils: Cd availability, soil properties, and microbial communities. Chemosphere. 2022, 301: 134551. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, X. Efficacy and microbial responses of biochar-nanoscale zero-valent during in-situ remediation of Cd-contaminated sediment. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 287: 125076. [CrossRef]

- Whitman, T.; Pepe-Ranney, C.; Enders, A.; Koechli, C.; Campbell, A.; Buckley, D.H.; Lehmann, J. Dynamics of microbial community composition and soil organic carbon mineralization in soil following addition of pyrogenic and fresh organic matter. The ISME Journal. 2016, 10: 2918-2930. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, L.; Khan, Z.H.; Saqib, H.; Gao, M.; Song, Z. Enhancing rice quality and productivity: Multifunctional biochar for arsenic, cadmium, and bacterial control in paddy soil. Chemosphere. 2023, 342: 140157. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Pei, J.; Wei, Z.; Ruan, X.; Hua, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T.; Guo, Y. A novel maize biochar-based compound fertilizer for immobilizing cadmium and improving soil quality and maize growth. Environmental Pollution. 2021, 277: 116455. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, L.; Zeng, G.; Xu, P.; Huang, C.; Deng, L.; Wang, R.; Wan, J. The effects of rice straw biochar on indigenous microbial community and enzymes activity in heavy metal-contaminated sediment. Chemosphere. 2017, 174: 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Luo, Y.; Sheng, M.; Xu, F.; Xu, H. Ecological responses of soil microbial abundance and diversity to cadmium and soil properties in farmland around an enterprise-intensive region. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2020, 392: 122478. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.; Saez, J.M.; Davila Costa, J.S.; Colin, V.L.; Fuentes, M.S.; Cuozzo, S.A.; Benimeli, C.S.; Polti, M.A.; Amoroso, M.J. Actinobacteria: Current research and perspectives for bioremediation of pesticides and heavy metals. Chemosphere. 2017, 166: 41-62. [CrossRef]

- Sazykin, I.; Khmelevtsova, L.; Azhogina, T.; Sazykina, M. Heavy metals influence on the bacterial community of soils: A review, Agriculture. 2023, 13: 653. ttps://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030653.

- Fan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Guo, Z. Characterization of keystone taxa and microbial metabolic potentials in copper tailing soils. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2023, 30: 1216-1230. [CrossRef]

- Fuke, P.; Kumar, M.; Sawarkar, A.D.; Pandey, A.; Singh, L. Role of microbial diversity to influence the growth and environmental remediation capacity of bamboo: A review. Industrial Crops and Products. 2021, 167: 113567. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Bai, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, P.; Xiao, Y.; Geng, J.; Liu, Q.; Hao, X. Application of mixotrophic acidophiles for the bioremediation of cadmium-contaminated soils elevates cadmium removal, soil nutrient availability, and rice growth. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2022, 236: 113499. [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H.; Yoon, A.R.; Park, Y.G. Plant growth-promoting microorganism Pseudarthrobacter sp. NIBRBAC000502770 enhances the growth and flavonoid content of Geum aleppicum, Microorganisms. 2022, 10: 1241.

- Li, J.; Peng, W.; Yin, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Deng, Z.; Lin, S.; Liang, R. Identification of an efficient phenanthrene-degrading Pseudarthrobacter sp. L1SW and characterization of its metabolites and catabolic pathway. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2024, 465: 133138. [CrossRef]

- Al-Karablieh, N.; Al-Shomali, I.; Al-Elaumi, L.; Hasan, K. Pseudomonas fluorescens NK4 siderophore promotes plant growth and biocontrol in cucumber. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2022, 133: 1414-1421. [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A.L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: from diversity and genomics to functional role in environmental remediation and plant growth. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 2020, 40: 138-152. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Govinden, R.; Chenia, H.Y.; Ma, Y.; Guo, D.; Ren, G. Suppression of Phytophthora blight of pepper by biochar amendment is associated with improved soil bacterial properties. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 2019a, 55: 813-824. [CrossRef]

- Chellaiah, E.R. Cadmium (heavy metals) bioremediation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a minireview. Applied Water Science. 2018, 8: 154. [CrossRef]

- Cheng. C.; Wang, R.; Sun, L.; He, L.; Sheng, X. Cadmium-resistant and arginine decarboxylase-producing endophytic Sphingomonas sp. C40 decreases cadmium accumulation in host rice (Oryza sativa Cliangyou 513). Chemosphere. 2021, 275: 130109. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xiong, J.; Zhou, B.; Wei, J.; Qian, A.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, J. Odor removal by and microbial community in the enhanced landfill cover materials containing biochar-added sludge compost under different operating parameters. Waste Management. 2019, 87: 679-690. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, Q.; Huang, Q.; Chen, W. Soil microbial augmentation by an EGFP-tagged Pseudomonas putida X4 to reduce phytoavailable cadmium. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 2012, 71: 55-60.

- Awan, S.A.; Khan, I.; Rizwan, M.; Irshad, M.A.; Xiaosan, W.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L. Reduction in the cadmium (Cd) accumulation and toxicity in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) by regulating physio-biochemical and antioxidant defense system via soil and foliar application of melatonin. Environmental Pollution. 2023, 328: 121658. [CrossRef]

- Irshad,M.K.; Noman, A.; Alhaithloul, H.A.; Adeel, M.; Rui, Y.; Shah, T.; Zhu, S.; Shang, J. Goethite-modified biochar ameliorates the growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants by suppressing Cd and As-induced oxidative stress in Cd and As co-contaminated paddy soil. Science of the Total Environment. 2020, 717: 137086. [CrossRef]

- Kamran. M.; Malik, Z.; Parveen, A.; Zong, Y.; Abbasim G,H,l Rafiqm M,T.; Shaaban, M.; Mustafa, A.; Bashir, S.; Rafay, M.; Mehmood, S.; Ali, M. Biochar alleviates Cd phytotoxicity by minimizing bioavailability and oxidative stress in pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) cultivated in Cd-polluted soil. Journal of Environmental Management. 2019, 250: 109500.

- Liu, Q.; Huang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Z.; Ma, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y. Biochar and its combination with inorganic or organic amendment on growth, uptake and accumulation of cadmium on lettuce. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022, 370: 133610. [CrossRef]

- Ghani, M.I.; Ahanger ,M.A.; Sial, T.A.; Haider, S.; Siddique, J.A.; Fan, R.; Liu, Y.; Ali, E.F.; Kumar, M.; Yang, X.; Rinklebe, J.; Chen, X.; Lee, S.S.; Shaheen, S.M. Almond shell-derived biochar decreased toxic metals bioavailability and uptake by tomato and enhanced the antioxidant system and microbial community. Science of the Total Environment. 2024, 929: 172632. [CrossRef]

- Jing. F.; Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Wen, X.; Hu, S.; Yang, Z.; Guo, B.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Q. Effects of wheat straw derived biochar on cadmium availability in a paddy soil and its accumulation in rice. Environmental Pollution. 2020, 257: 113592. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Q,i X.; Fan, X.; Du, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y. Amending the seedling bed of eggplant with biochar can further immobilize Cd in contaminated soils. Science of the Total Environment. 2016, 572: 626-633. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Duan, C.; Liang, H.X.; Ren, J.W.; Geng, Z.C.; Xu, C.Y. Phosphorus acquisition strategies of wheat are related to biochar types added in cadmium-contaminated soil: Evidence from soil zymography and root morphology. Science of the Total Environment. 2023b, 856: 159033. [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; Xu, M.; Ma, J.; Gao, P.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.; Wu, J.; Song, C.; Long, L.; Chen, C. Remediation of cadmium contaminated soil using K2FeO4 modified vinasse biochar. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2023, 262: 115171. [CrossRef]

| Adsorbents | Yield (%) | Ash (%) | pH | ABET (m2 g-1) |

Vtot (cm3 g-1) |

Dapd (nm) |

Elemental Content (%) | Atomicratio(%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | O | N | S | H/C | O/C | |||||||

| BC | 51.6% | 20.7% | 9.45 | 7.17 | 0.0084 | 30.91 | 49 | 2.82 | 12.99 | 1.44 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.27 |

| FB | 93.7% | 36.8% | 10.48 | 17.53 | 0.0506 | 16.03 | 26.15 | 1.15 | 19.34 | 1.82 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.74 |

| Treatments | Lettuce Leaves Dry Weight (g) | Lettuce Roots Dry Weight (g) | VC (mg g-1) |

MDA (μmol g-1 ) |

POD (U mg-1) |

SOD (U mg-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd 0 | ||||||

| C0B0 | 0.82±0.14b | 0.27±0.03b | 115.5±4.82c | 6.33±0.26a | 0.399±0.029b | 0.249±0.010b |

| C0B1 | 1.25±0.25a | 0.35±0.02a | 137.5±12.35c | 5.70±0.44a | 0.479±0.036a | 0.333±0.053a |

| C0B3 | 1.33±0.14a | 0.35±0.02a | 185.2±17.18b | 4.98±0.70b | 0.549±0.061a | 0.374±0.044a |

| C0FB1 | 1.29±0.20a | 0.36±0.02a | 177.9±19.24b | 4.73±0.51b | 0.523±0.053a | 0.359±0.018a |

| C0FB3 | 1.36±0.26a | 0.39±0.03a | 221.8±19.81a | 5.03±0.59b | 0.535±0.095a | 0.328±0.048a |

| Cd 1 | ||||||

| C1B0 | 0.80±0.14b | 0.25±0.04b | 108.1±12.17c | 6.52±0.51a | 0.364±0.055b | 0.246±0.005b |

| C1B1 | 1.28±0.24a | 0.36±0.03a | 131.0±21.55c | 5.34±0.24a | 0.462±0.045a | 0.338±0.043a |

| C1B3 | 1.37±0.20a | 0.37±0.04a | 177.8±11.37b | 4.63±0.53b | 0.562±0.077a | 0.347±0.019a |

| C1FB1 | 1.36±0.23a | 0.38±0.03a | 184.2±12.82b | 4.85±0.40b | 0.511±0.053a | 0.345±0.055a |

| C1FB3 | 1.43±0.25a | 0.38±0.06a | 228.2±17.91a | 4.47±0.20b | 0.568±0.073a | 0.343±0.070a |

| Cd 2 | ||||||

| C2B0 | 0.72±0.11b | 0.27±0.05b | 100.1±1.40c | 8.33±0.32a | 0.343±0.010b | 0.232±0.009b |

| C2B1 | 1.24±0.20a | 0.37±0.05a | 122.6±7.89c | 5.62±0.97a | 0.420±0.037a | 0.346±0.041a |

| C2B3 | 1.36±0.17a | 0.37±0.01a | 163.5±23.08b | 4.70±0.33b | 0.459±0.073a | 0.379±0.029a |

| C2FB1 | 1.32±0.26a | 0.38±0.03a | 181.0±6.06a | 4.63±0.30b | 0.44±0.0260a | 0.351±0.045a |

| C2FB3 | 1.42±0.07a | 0.38±0.03a | 197.3±8.79a | 4.69±0.10b | 0.495±0.022a | 0.389±0.021a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).