Submitted:

18 June 2025

Posted:

19 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Soil and Biochar

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

2.3.1. Determination of the Activities of Soil Enzymes

2.3.2. Analysis of Soil Chemical Properties

2.3.3. Sequencing of Fungal and Bacterial Amplicons

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

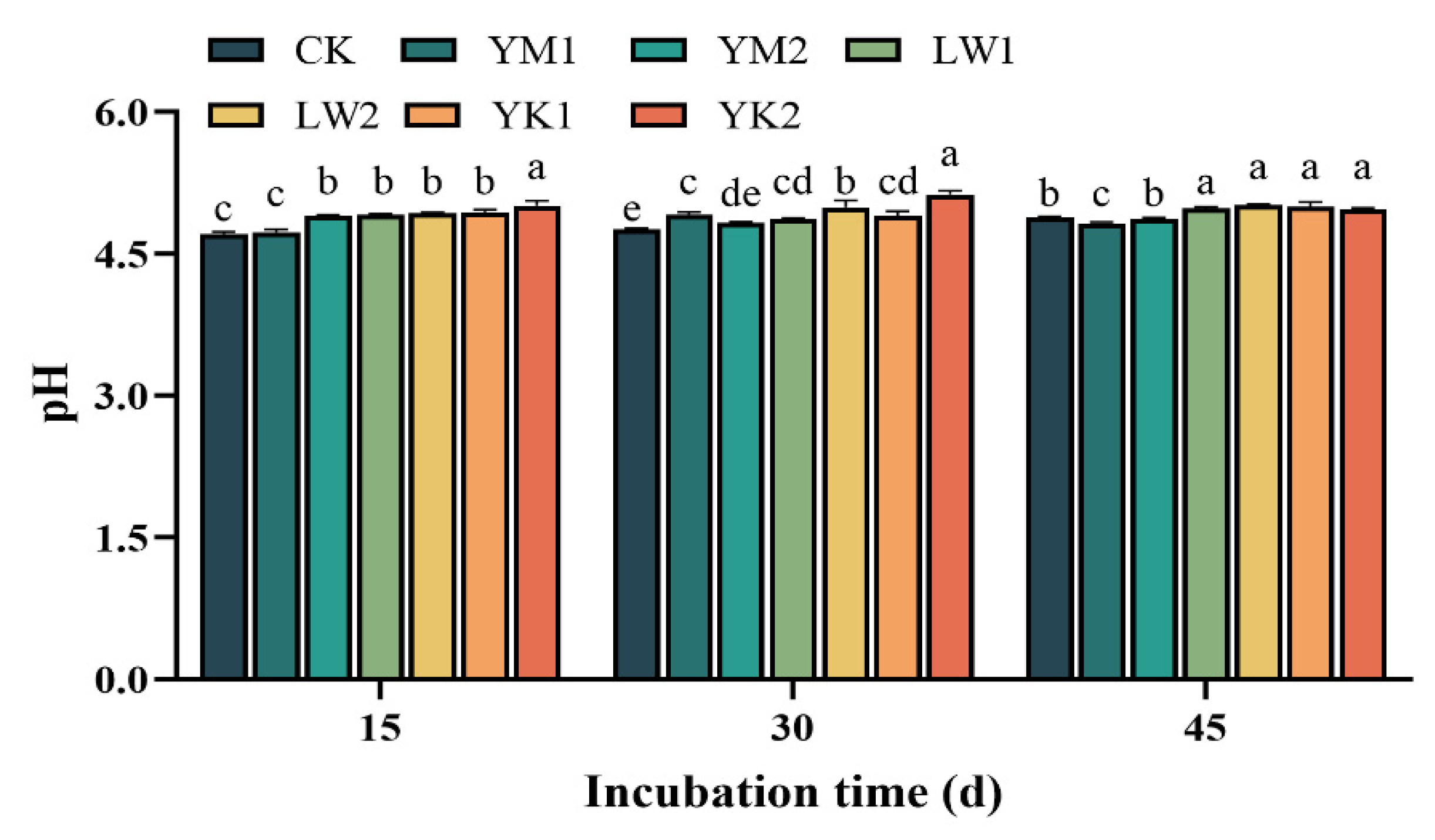

3.1. Effect of Biochar Application on Soil pH in Tea Plantation

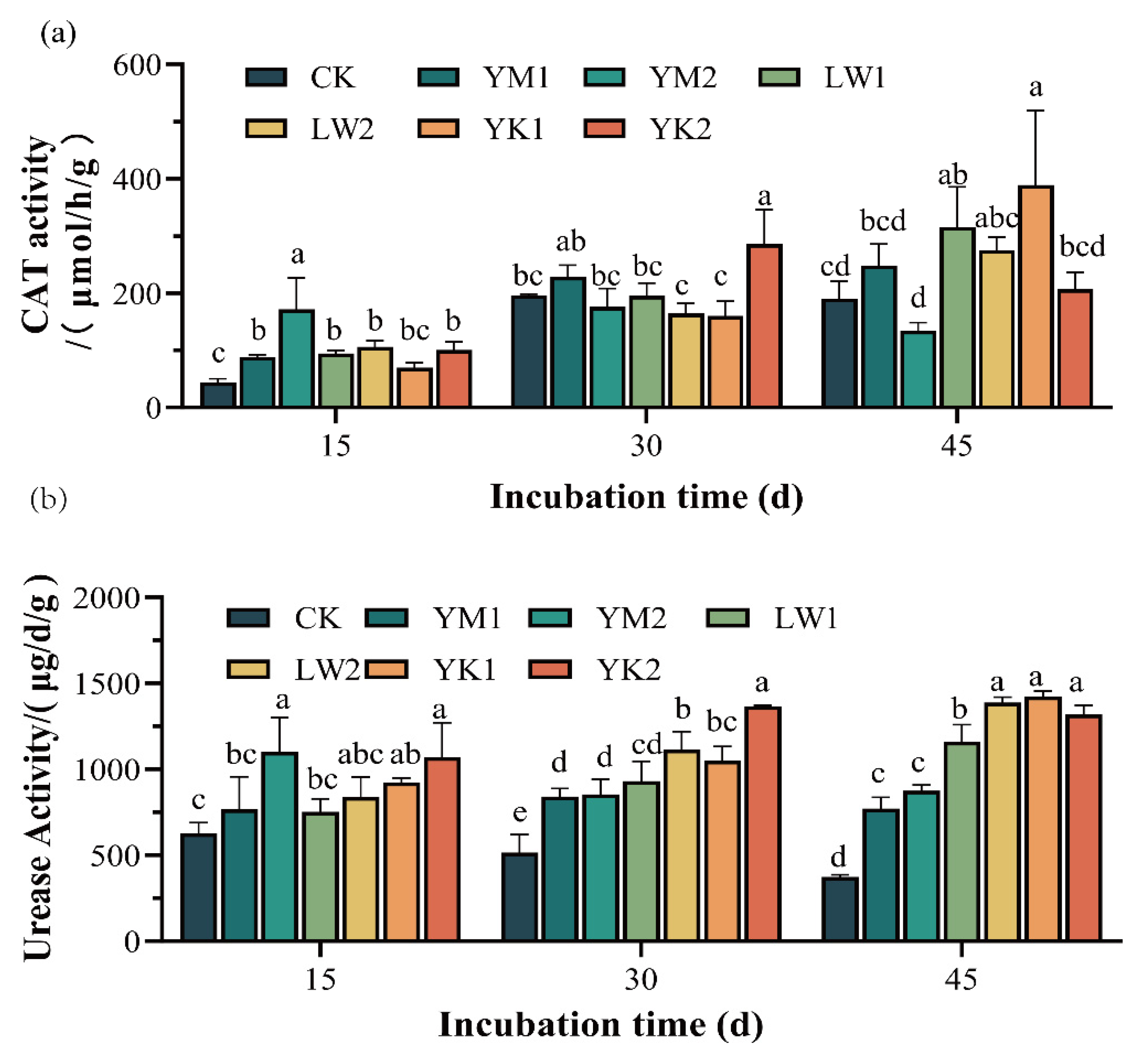

3.2. Effect of Biochar Application on Soil Enzyme Activity in Tea Plantation

3.3. Effects of Biochar Application on Soil Nutrient Content in Tea Plantation

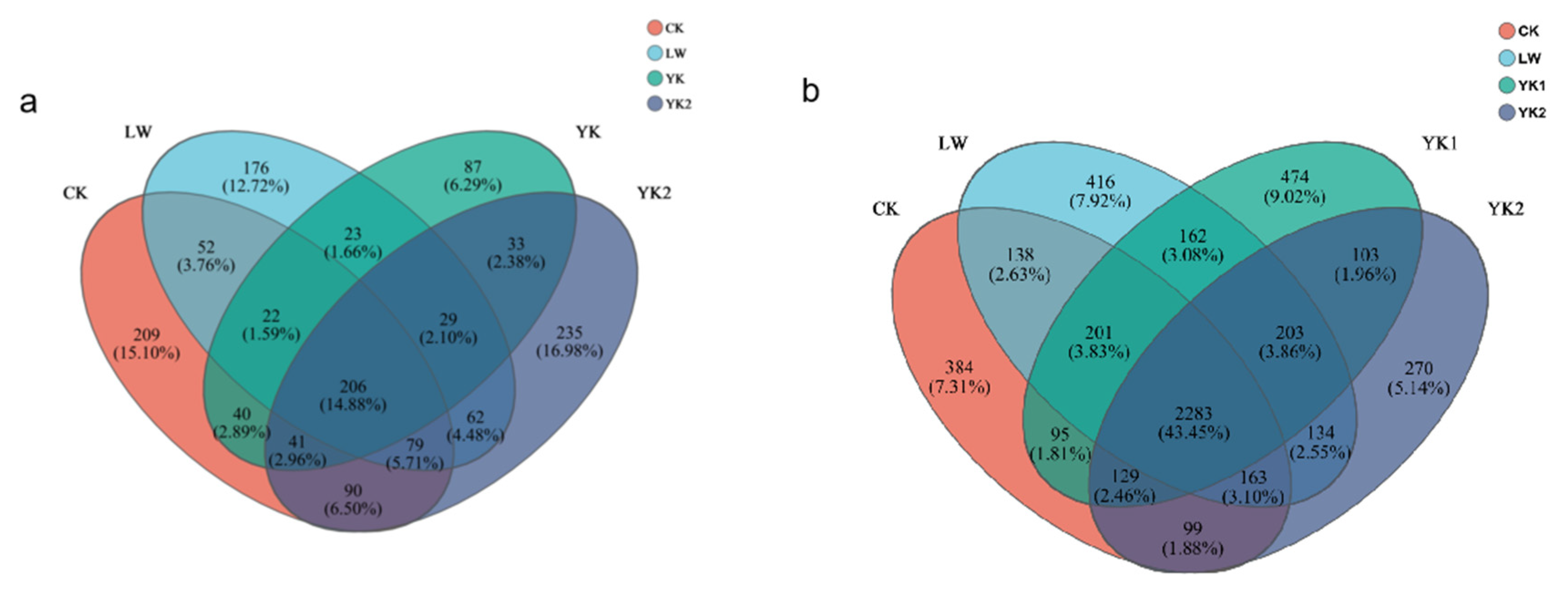

3.4. Effects of Biochar on Microbial Community Richness and Diversity

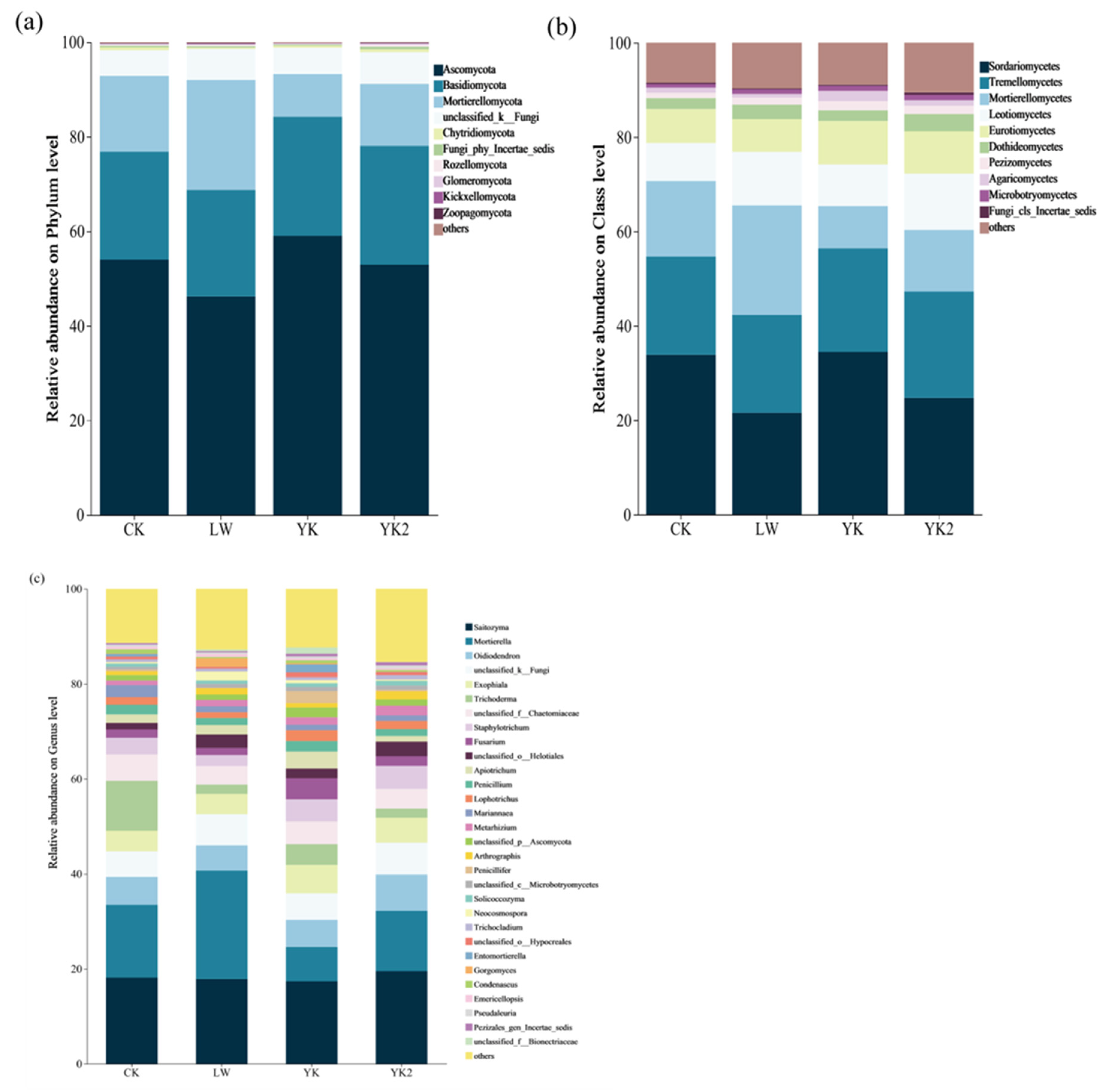

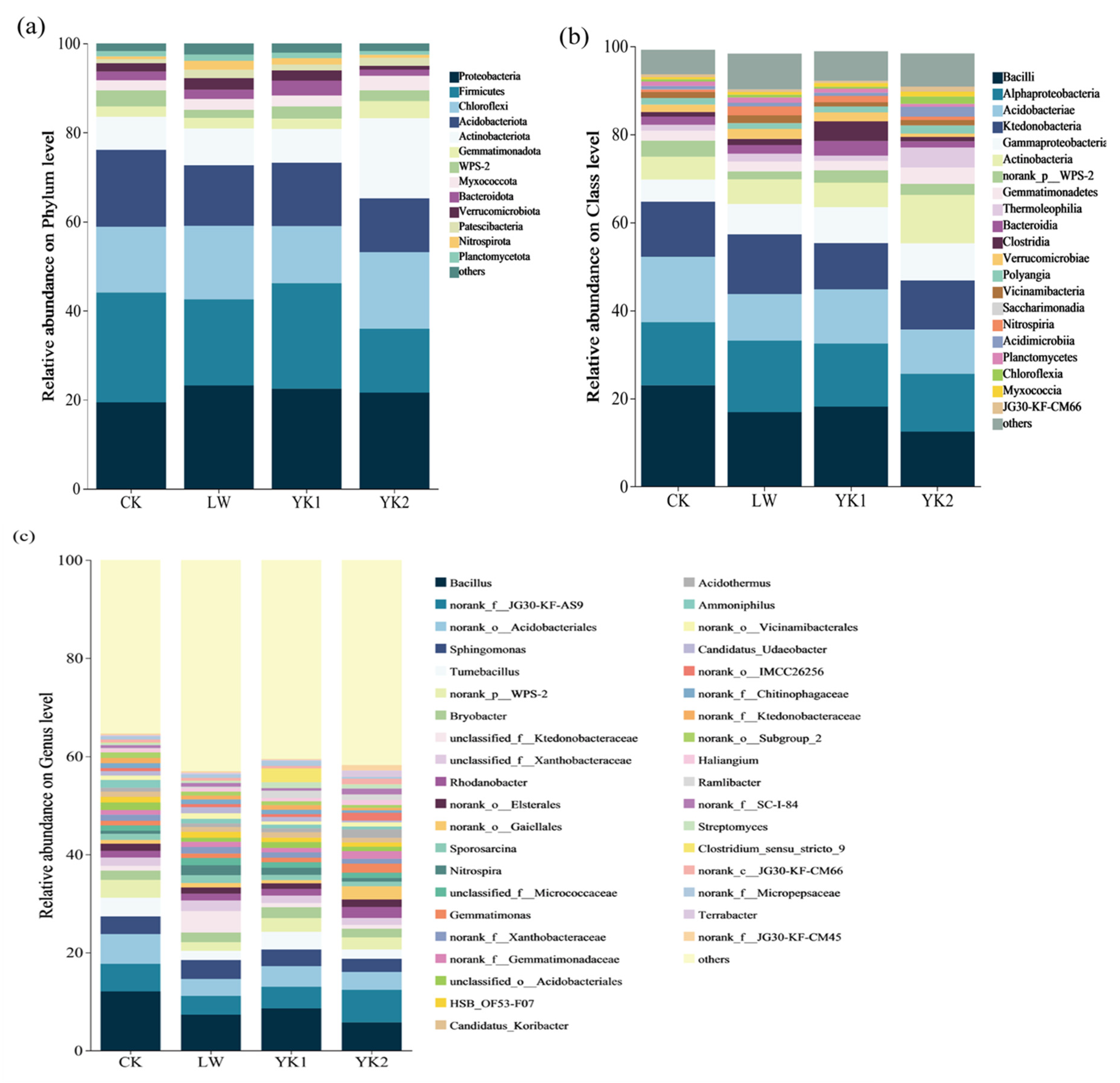

3.5. Effects of Biochar on Microbial Community Composition

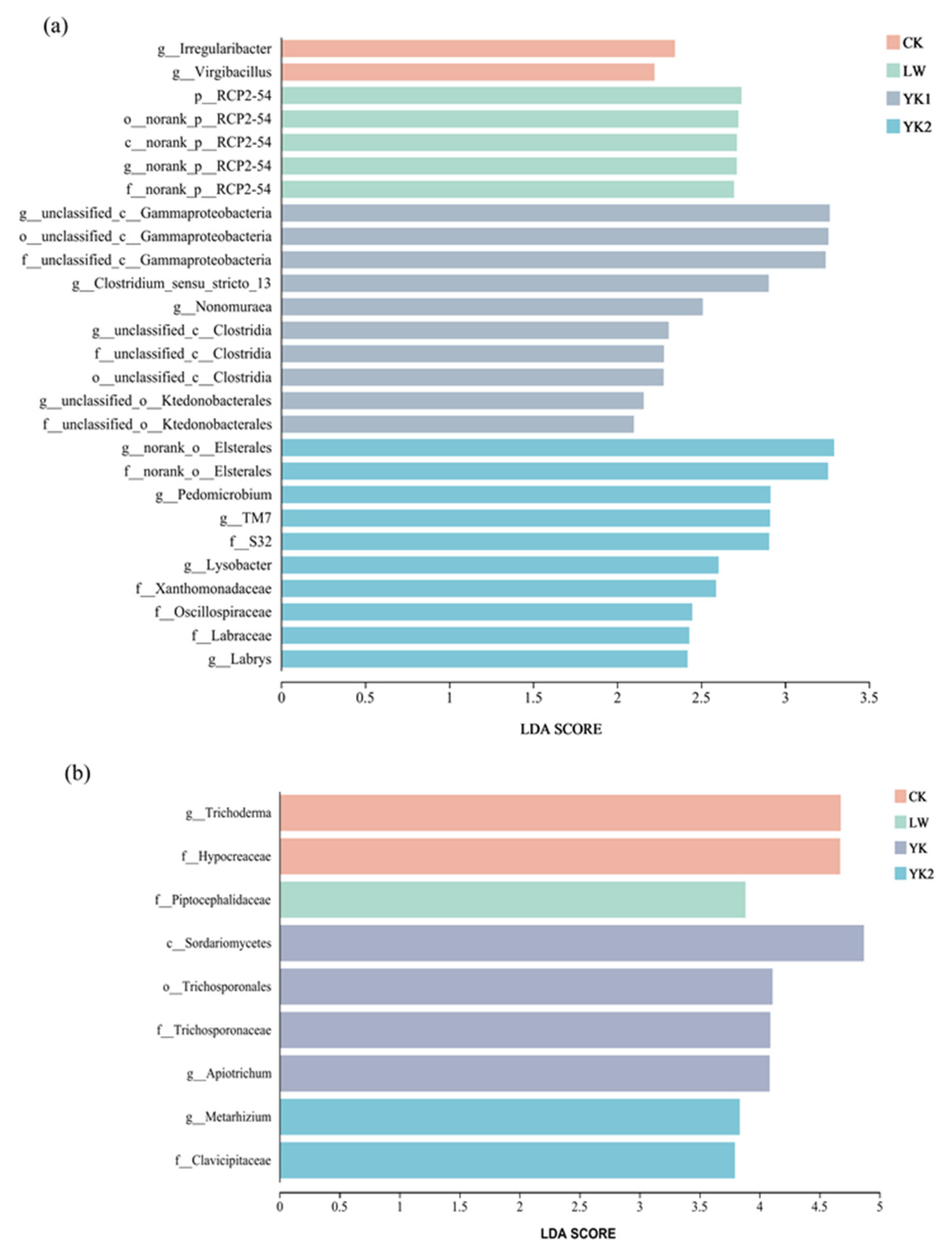

3.6. Differences in Microbial Community Populations in Tea Plantations

3.7. Correlations Between Soil Environmental Factors and Microbial Community Structure

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Biochar on Soil pH in Tea Plantations

4.2. Effects of Biochar on Soil Enzyme Activity and Chemical Properties in Tea Plantationls

4.3. Effects of Biochar on Microbial Communities in Tea Plantation Soils

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, X.P.; Sun, M.S.; Xiong, Y.Y.; Liu, X.; Li, C.H.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.B. Restriction site-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq) of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) in Sichuan province, China, provides insights into free amino acid and polyphenol contents of tea. PLoS ONE 2024, 19(12), e0314144. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Huang, X.J.; Zang, Z. Spatio-temporal variation and driving forces of tea production in China over the last 30 years. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28(3), 275-290. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Y.; Yang, J.F. Economic analysis of the change of tea production layout in China. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1629, 012048. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Tang, X.B.; Zeng, X.Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.H. Analysis of Fertilization Status and Measures in Tea Plantations in Sichuan. Sichuan Agricultural Science and Technology 2021, 9, 39–40.

- Afshar, M.; Mofatteh, S. Biochar for a sustainable future: Environmentally friendly production and diverse applications. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102433. [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.S.; Bhandari, S.; Bhatta, D.; Poudel, A.; Bhattarai, S.; Yadav, P.; Ghimire, N.; Paudel, P.; Paudel, P.; Shrestha, J.; Oli, B. Biochar application: A sustainable approach to improve soil health. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 11, 100498. [CrossRef]

- Oo, A.Z.; Sudo, S.; Akiyama, H.; Win, K.T.; Shibata, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Sano, T.; Hirono, Y. Effect of dolomite and biochar addition on N₂O and CO₂ emissions from acidic tea field soil. PLOS One 2018, 13, e0192235. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.H.; Mi, W.H.; Li, X.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, L.P.; Zhang, L.; Fu, J.Y.; Li, Z.Z.; Han, W.Y.; Yan, P. Biochar application method influences root growth of tea (Camellia sinensis L.) by altering soil biochemical properties. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 315, 111960. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.F.; Liu, Y.Z.; Mo, C.Y.; Jiang, Z.H.; Yang, J.P.; Lin, J.D. Microbial mechanism of biochar addition on nitrogen leaching and retention in tea soils from different plantation ages. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143817. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Comparison of Biochar- and Lime-Adjusted pH Changes in N2O Emissions and Associated Microbial Communities in a Tropical Tea Plantation Soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1144. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xia, X.; Su, Y.; Liao, W. Combined Application of Biochar and Pruned Tea Plant Litter Benefits Nitrogen Availability for Tea and Alters Microbial Community Structure. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1465. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Huang, J.Q.; Ye, J.; Li, Y.C.; Lin, Y.; Liu, C.W. Effects of Biochar Application on Soil Properties and Fungi Community Structure in Acidified Tea Garden. Journal of Tea Science 2021, 41, 419-429. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, Y.Z.; Wu, Z.D.; Jiang, F.Y.; Yu, W.Q.; You, Z.M. Effects of Reduced Chemical Fertilizer Applications on Fungal Community and Functional Groups in Tea Plantation Soil. Acta Tea Sinica 2021, 62, 170-178.

- Kuang, C.T.; Jiang, C.Y.; Li, Z.P.; Hu, F. Effects of Biochar Amendments on Soil Organic Carbon Mineralization and Microbial Biomass in Red Paddy Soils. Soils 2012, 44, 570-575. [CrossRef]

- Trasar-Cepeda, C.; Camiña, F.; Leirós, M.C.; Gil-Sotres, F. An improved method to measure catalase activity in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31(3), 483-485. [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55(1), 11-33. [CrossRef]

- Dick, W.A.; Tabatabai, M.A. An Alkaline Oxidation Method for Determination of Total Phosphorus in Soils†. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1977, 41(3), 511-514. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Planting increases the abundance and structure complexity of soil core functional genes relevant to carbon and nitrogen cycling. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14345. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.L.; Crandall, S.H. Power Flow and Energy Relations in a Cello-Stage-Air System. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1974, 55(2_Supplement), 456–457. [CrossRef]

- Mehlich, A. Mehlich 3 soil test extractant: A modification of Mehlich 2 extractant. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1984, 15(12), 1409–1416. [CrossRef]

- Inorganic Forms of Nitrogen. In Handbook of Soil Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006; pp 767–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-31211-6_28. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.H.; Zhou, B.Q.; Yang, J.; Xing, S.H. Effect of Biochar-based fertilizer on soil bacteria and fungi quantity and community structure in acidified tea garden. J. Fujian Agric. Forest. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 52, 247-257. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.W.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.H.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.L.; Feng, J.T.; Chen, H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big - data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733 - 1742. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Sun, J.H.; Gan, Q.Y.; Shi, N.N.; Fu, S.L. Zea mays cultivation, biochar, and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal inoculation influenced lead immobilization. Microbiol. Spectrum 2024, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Stpniewska, Z.; Wolińska, A.; Ziomek, J. Response of soil catalase activity to chromium contamination. J. Environ. Sci. 2009, 21(8), 1142-1147. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wu, J.Q.; Li, G.; Yan, L.J. Changes in soil carbon fractions and enzyme activities under different vegetation types of the northern Loess Plateau. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10(21), 12211-12223. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; He, L.L.; Liu, Y.X.; Lü, H.H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Yang, S.M. Effects of biochar addition on enzyme activity and fertility in paddy soil after six years. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 1110-1118. [CrossRef]

- Pettit, N.M.; Smith, A.R.J.; Freedman, R.B.; Burns, R.G. Soil urease: Activity, stability and kinetic properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1976, 8(6), 479-484. [CrossRef]

- Walters, K.E.; Martiny, J.B.H. Alpha-, beta-, and gamma-diversity of bacteria varies across habitats. PLoS ONE 2020, 15(9), e0233872. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of microbial compositions: a review of normalization and differential abundance analysis. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 60. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Hou, R.J.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.X.; Li, M.; Cui, S.; Li, Q.L.; Liu, M.X. A critical review of biochar as an environmental functional material in soil ecosystems for migration and transformation mechanisms and ecological risk assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121196. [CrossRef]

- Kuryntseva, P.; Karamova, K.; Galitskaya, P.; Selivanovskaya, S.; Evtugyn, G. Biochar Functions in Soil Depending on Feedstock and Pyrolyzation Properties with Particular Emphasis on Biological Properties. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Shen, C.; Zou, Z.H.; Fu, J.Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.P.; Zhang, L.; Han, W.Y.; Fan, L.C. Biochar stimulates tea growth by improving nutrients in acidic soil. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 283, 110078. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Hu, T., Wang, M. et al. Biochar addition to tea garden soils: effects on tea fluoride uptake and accumulation. Biochar 5, 37 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Hennayake, H.M.K.D.; Sun, H. Biochar effectively reduces ammonia volatilization from nitrogen - applied soils in tea and bamboo plantations. Phyton - Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 88, 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Sarmah, A.K.; Bordoloi, S.; Bolan, S.; Padhye, L.P.; Van Zwieten, L.; Sooriyakumar, P.; Khan, B.A.; Ahmad, M.; Solaiman, Z.M.; Rinklebe, J.; Wang, H.L.; Singh, B.P.; Siddique, K.H.M. Soil acidification and the liming potential of biochar. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 317, 120632. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.Y.; Li, J.Y.; Ni, N.; Xu, R.K. Understanding the biochar's role in ameliorating soil acidity. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18(7), 1508-1517. [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Conradie, J.; Ohoro, C.R.; Amaku, J.F.; Oyedotun, K.O.; Maxakato, N.W.; Akpomie, K.G.; Okeke, E.S.; Olisah, C.; Malloum, A.; Adegoke, K.A. Biochar from coconut residues: An overview of production, properties, and applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 204(Pt A), 117300. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.S.; Awasthi, M.K.; Wang, Y.F.; Xu, P. Current understanding in conversion and application of tea waste biomass: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 338, 125530. [CrossRef]

- Jian, M.F.; Gao, K.F.; Yu, H.P. Effects of different pyrolysis temperatures on the preparation and characteristics of biochar from rice straw. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2016, 36(05), 1757-1765. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Sharma, Y.M.; Sharma, A.; Dwivedi, A.K. Activities of β - glucosidase, Phosphatase and Dehydrogenase as Soil Quality Indicators: A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8(06), 834-846. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gan, B.; Li, Q.; Xiao, W.; Song, X. Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Addition on Soil Extracellular Enzyme Activity and Stoichiometry in Chinese Fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) Forests. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 834184. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Geng, Z.C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H.F. Effects of Biochar Amendment on Microbial Biomass and Enzyme Activities in Loess Soil. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2014, 33, 751-758.

- Liu, J.; Li, X.Y.; Zhu, Q.L.; Zhou, J.W.; Shi, L.F.; Lu, W.H.; Bao, L.; Meng, L.; Wu, L.H.; Zhang, N.M.; Christie, P. Differences in the activities of six soil enzymes in response to cadmium contamination of paddy soils in high geological background areas. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 346, 123704. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.G.; Gao, C.S.; Lü, G.H.; Sui, Y.Y. Effect of Long-Term Fertilization on Soil Enzyme Activities Under Different Hydrothermal Conditions in Northeast China. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10(3), 412-422. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.W.; Jiang, Y.H.; Weng, B.Q.; Lin, W.X. Variations of rhizosphere bacterial communities in tea (Camellia sinensis L.) continuous cropping soil by high - throughput pyrosequencing approach. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 787-799. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Li, T.X.; Zheng, Z.C. Response of soil aggregate-associated microbial and nematode communities to tea plantation age. Catena 2018, 171, 475-484. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.Q.; Xu, P.S.; Li, Z.T.; Lin, H.Y.; Zhu, C.; Wang, J.Y.; Zou, J.W. Microbial diversity and the abundance of keystone species drive the response of soil multifunctionality to organic substitution and biochar amendment in a tea plantation. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 14(4), 481-495. [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.L.; Xu, C.S.; He, H.H.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, N.; Li, X.L.; Liu, G.S. Effects of Biochar on Soil Enzyme Activity & the Bacterial Community and Its Mechanism. Environ. Sci. 2021, (01), 422-432. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.K.; Wu, Y.B.; Liu, J.P.; Xue, J.H. A Review of Research Advances in the Effects of Biochar on Soil Nitrogen Cycling and Its Functional Microorganisms. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2022, (06), 689-701. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.L.; Zhao, H.B.; Han, B.; Fan, Y.F.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.F.; Bai, X. Changes of Soil Microbial Community Structure and Diversity in Plant Growing Season of Degraded Grassland. Chin. J. Grassl. Sci. 2021, (10), 46-54. [CrossRef]

- Mujakić, I.; Piwosz, K.; Koblížek, M. Phylum Gemmatimonadota and Its Role in the Environment. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 151. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.H.; Xu, H.M.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Gundale, M.J.; Zou, X.M.; Ruan, H.H. Global meta - analysis reveals positive effects of biochar on soil microbial diversity. Geoderma 2023, 436, 116528. [CrossRef]

- Kielak, A.M.; Barreto, C.C.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; van Veen, J.A.; Kuramae, E.E. The Ecology of Acidobacteria: Moving beyond Genes and Genomes. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 744. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, P.C.; Lv, A.P.; Li, P.P.; Liu, L.; Li, W.J.; Yang, L.L.; Zhi, X.Y. Comparative genomic analysis and proposal of Clostridium yunnanense sp. nov., Clostridium rhizosphaerae sp. nov., and Clostridium paridis sp. nov., three novel Clostridium sensu stricto endophytes with diverse capabilities of acetic acid and ethanol production. Anaerobe 2023, 79, 102686. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, J.; Li, T.; Liao, Y. Response of soil fungal communities to continuous cropping of flue-cured tobacco. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19911. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.Y.; McNamara, P.J.; St. Leger, R.J. Metarhizium: an opportunistic middleman for multitrophic lifestyles. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 69, 102176. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Keyhani, N.O.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Pu, H.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Lai, P.; Zhu, M.; He, X.; Cai, S.; Guan, X.; Qiu, J. Isolation of a highly virulent Metarhizium strain targeting the tea pest, Ectropis obliqua. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1164511. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Nath, B.C.; Sarma, B.; Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Borgohain, D.J.; Garganese, F.; Ahmed, S.; Batsya, S.; Mudoi, A.; Kumari, R. Interaction of Metarhizium anisopliae Against Emergent Insect Pest Problems in the North-Eastern Tea Industry. In Entomopathogenic Fungi; Deshmukh, S.K., Sridhar, K.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 319–357. [CrossRef]

| Biochar types | YM | LW | YK |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.7 |

| C (%) | 42.08 | 58.34 | 94.80 |

| Ash (%) | 8.43 | 7.50 | 4.60 |

| Pyrolysis Temperature(℃) | 500 | 500 | 700 |

| Specific Surface Area(m2/g) | 68 | 41 | 1150 |

| Treatments | The application level of biochar |

|---|---|

| CK | No biochar application (0%) |

| YM1 | Corn stover biochar (0.5%) |

| YM2 | Corn stover biochar (1.0%) |

| LW1 | Reed biochar (0.5%) |

| LW2 | Reed biochar (1.0%) |

| YK1 | Coconut shell biochar (0.5%) |

| YK2 | Coconut shell biochar (1.0%) |

| Treatments | TN/(g/kg) | TP/(g/kg) | TK/(g/kg) | AP/(mg/kg) | AK/(mg/kg) | AN/(mg/kg) | SOC/(g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 1.53 ± 0.13a | 0.79 ± 0.05a | 10.56 ± 1.23a | 61.12 ± 4.10b | 333.28 ± 20.21ab | 139.90 ± 18.53ab | 32.68 ± 0.51d |

| LW1 | 1.53 ± 0.15a | 0.76 ± 0.00a | 10.92 ± 0.35a | 52.87 ± 3.14c | 327.28 ± 10.13b | 124.91 ± 16.16ab | 35.28 ± 0.76c |

| YM1 | 1.69 ± 0.01a | 0.78 ± 0.02a | 10.28 ± 0.84a | 73.28 ± 3.10a | 356.30 ± 0.44a | 144.33 ± 9.82ab | 36.72 ± 0.73c |

| YK1 | 1.67 ± 0.02a | 0.80 ± 0.05a | 10.55 ± 1.00a | 68.17 ± 6.26ab | 327.22 ± 10.22b | 151.79 ± 7.55a | 39.47 ± 1.81b |

| YK2 | 1.66 ± 0.03a | 0.82 ± 0.08a | 11.50 ± 1.52a | 70.09 ± 1.54a | 350.42 ± 20.04ab | 121.59 ± 14.87b | 47.26 ± 1.12a |

| Treatments | ACE | Chao | Shannon | Simpson | Sobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 397.44 ± 16.70a | 402.48 ± 15.66a | 3.67 ± 0.13a | 0.0709 ± 0.01a | 387 ± 16.83a |

| LW | 323.44 ± 74.39a | 326.67 ± 75.79a | 3.57 ± 0.27a | 0.0917 ± 0.02a | 312 ± 72.26a |

| YK1 | 249.59 ± 19.34a | 248.63 ± 19.12a | 3.78 ± 0.03a | 0.0564 ± 0.00a | 243 ± 17.36a |

| YK2 | 402 ± 91.46a | 407.63 ± 93.11a | 3.9 ± 0.07a | 0.0643 ± 0.00a | 390 ± 88.40a |

| Treatments | ACE | Chao | Shannon | Simpson | Sobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 2952.24 ± 61.13a | 2852.2 ± 49.90a | 5.91 ± 0.03a | 0.0126 ± 0.00a | 2391 ± 43.24a |

| LW | 3106.68 ± 77.37a | 3008.16 ± 67.79a | 6.15 ± 0.13a | 0.0102 ± 0.00a | 2560 ± 54.48a |

| YK1 | 3117.77 ± 30.74a | 3018.05 ± 28.17a | 5.99 ± 0.16a | 0.0111 ± 0.00a | 2476 ± 75.45a |

| YK2 | 2805.04 ± 195.27a | 2749.48 ± 170.77a | 6.22 ± 0.05a | 0.0064 ± 0.00a | 2304 ± 133.23a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).