1. Introduction

Recently there is a significantly increased interest in poly-l-lactide (PLLA) organic piezoelectric as very promising natural-sourced biomaterial for designing next-generation stimuli-active medical devices [

1]–[

4]. Partially it comes from biodegradable and biocompatible nature of PLLA, approved by EMA and FDA for the application in therapeutics and medical devices [

5], which has been validated during extensive investigations for past few decades and clinical applications [

6]–[

8]. As biodegradable organic piezoelectric PLLA is potentially applicable for implantable bioelectronics, advanced biomedical sensing technologies, stimuli-responsive drug delivery and bioactive tissue regeneration approaches [

2], [

4]. Particular advantages of PLLA as organic piezoelectric consider its ability to be activated using ultrasound (US) [

9]. This opens the possibility for remote activation of the implanted biomaterial and triggering electrical stimuli on request which opens minimally invasive, very precise and wireless electrical stimulation [

2], [

10].

As organic piezoelectric with piezoelectric constant d

14 = 9.82 [

11] PLLA is positioned at the pivotal place among leading biodegradable piezoelectric [

1], [

12]–[

14]. Still its piezoelectric properties are low for effective applications and require further tailoring [

4], [

13]–[

15]. For that purpose diverse strategies based on processing composites, applying fillers (including morphologically anisotropic hydroxyapatite (HAp) crystalline particles), physical and chemical modifications were developed [

1], [

4], [

14]–[

16]. Due to the helix structure with polar C=O groups bonded to the asymmetric C-atom in PLLA chains, the orientation of dipoles is random resulting in zero net polarization [

14], [

15]. Shearing the PLLA helixes slightly orients the C=O dipoles producing the net polarization and inducing shear piezoelectricity[

14], [

15]. Because of this type of the structure, all of the processing approaches focused on increasing the PLLA piezoelectricity, either they are performed in solid, solution or melt, are targeting two critical parameters, including crystallization (crystalline phase, degree of orientation and crystallite orientation) and molecular chain orientation [

1], [

14].

Processing polymer melt or softened solid provides controlled solidifying of the polymer under unidirectional force which affects its structural properties and enables oriented semi-crystalline structures [

1]. The main advantages of processing PLLA from melt or softened solid is in simplicity and skipping the toxic organic solvents. However the main challenge in this type of processing remains in keeping the molecular chain orientation stable as polymer melt and softened solid relax fast [

14]. The main parameters which are commonly controlled are annealing temperature, drawing rate and drawing ratio (DR) [

4], which are found to be 80-90⁰C, 40mm/min and DR5 for PLLA [

17]. The stretching, however, strongly depends on molecular chains mobility in the melt and softened solid, mechanical properties of the polymer and effect of the force used for mechanical drawing. At certain point there is a limit in maximal drawing ratio before breaking the film that also limits maximal contribution of applied force.

In general, PLLA suffers from low melting and softening strength, poor thermal resistance, low crystallization kinetics and brittleness, which is particularly increased with increased percentage of crystallinity [

18]. Fortunately, there are processing approaches, including branching, adding fillers and blending with other polymers, which increase its melting and softening strength and crystallization behavior. Particularly it has been observed that PLLA composites, containing low contents of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or cellulose blended with PLLA, have capacity to improve crystallization and mechanical properties, including better melting elasticity [

19], [

20]. Interestingly, tailoring the properties of PTFE tailors its influence to the crystallization and mechanical properties of another polymer, which then includes possibility of applying different types of PTFE as another processing option [

21].

Despite recent progress, optimizing piezoelectricity of PLLA still remains one of the important challenges for exploring the full capacities offered by biodegradable flexible bioelectronics. Starting from the above described benefits and limitations of the high-temperature drawing for optimizing piezoelectricity of PLLA, the idea of this work was exploring the applicability of another polymer, deposited at the surface of PLLA as contacting layer, and its potential contribution to the drawing process toward improved crystallization, molecular orientation and increased piezoelectricity. We hypothesized that piezo-PLLA films with different contacting layers will be differently activated with US which will affect piezostimulation of cells directly grown at their surface and their response to transferred electro-stimuli.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials. Poly-L-lactide resomer L 207 S (Evonik), chloroform (≥99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich), N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, anhydrous, 99.8%, Sigma Aldrich), Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, Teflon, Dastaflon), Teflon S (Coating Solutions), Polyimide (PI, Kapton, Dasteflon), Baking Paper, dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR, >95%, Sigma-Aldrich), Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich), fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), penicillin-streptomycin (1:1, Gibco), Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS, Sigma-Aldrich), TrypLE select (Gibco, USA), poly-L-lysine solution (mol wt. 70 000–150 000, 0.01%, sterile-filtered, Bio Reagent, Sigma, UK), PrestoBlue Cell Viability Reagent (Molecular Probes, Thermo-Fisher Scientific), bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein detection assay kit (Sigma Aldrich), RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer (Thermo Scientific), HaltTM protease & phosphatase inhibitor single-use cocktail (100x) (Thermo Scientific), Triton X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich Life science, USA), paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), Rhodamine Phalloidin (RP, Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and DAPI (diamidino-2-phenylindole, Biotium, Fremont, CA) were used.

Processing PLLA films. After dissolving PLLA (2 g) in chloroform (20 ml), 5 ml of DMF was added and the mixture was homogenized by mixing at magnetic stirrer for the next 2 hours. In case of adding HAp filler, it was dispersed in DMF to form 1wt.% PLLA HAp. The HAp filler has been synthesized using previously developed sonochemical approach [

22], [

23]. It was dispersed in DMF and the mixture is added to the polymer solution to homogenize. The mixture was solvent- casted in Petri dish (φ=15cm) and dried polymer was further processed into films, as previously optimized [

17]. The polymer was put in rectangle aluminium mold covered by contacting layer (Teflon, Treflon S, PI or Paper), pressed by metallic plates and then heated to 250 °C in order to melt inside the mold. Afterwards, it was hot pressed (40 kN, 2 min) and immediate quenched in water (10 ⁰C) to form non-drawn films (PLLA DR1 or PLLA HAp DR1). The DR1 films were pre-heated at 80 °C and then uniaxially drawn (with 40 mm/min rate) to 5 times their initial length to form PLLA DR5 and PLLA HAp DR5 films. Depending on the type of contacting layer the films were labelled PLLA DR5 Teflon, PLLA DR5 Teflon S, PLLA DR5 Paper or PLLA DR5 PI as well as PLLA HAp DR5 Teflon, PLLA HAp DR5 Teflon S, PLLA HAp DR5 Paper or PLLA HAp DR5 PI.

Structural characterization. The crystalline phases were identified by x-ray diffraction analysis using EMPYREAN (2θ range 10°–60°, 0.026° step size with 500 s time of capture). Small- and wide -angle X-ray scattering (SAXS and WAXS) analyses were performed on a SAXS Point 2.0 system (Anton Paar, Institute of Biotechnology of the Czech Academy of Sciences located in BIOCEV centre, Czech Republic) equipped with Gallium source (λ = 1.34 Ӓ), synchrotron, and a Eiger R 1M detector at room temperature in the transmission mode. Intensities were taken for 180 ms frame rate and 15 s acquisition time. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (NETZSCH STA 449, in an Ar/O atmosphere (40/10) was used to determine the total crystallinity of films. The samples were measured in a range from 40 °C to 200 °C at 20°C/min heating rate and percentage of crystallinity (Xc) was calculated using Xc (%) = ((∆H(m )- ∆Hcc ))/(∆H100) with ΔH100% corresponding to the theoretical 100% crystalline PLLA films with α crystalline form (93.6 J/g). Polarized Raman spectrometry (NTEGRA Spectra NT-MDT) was used to determine the molecular chain orientation of the polymer. The spectra were recorded using 488 nm laser in the range 200–3200 cm−1. The normalization was done to the CH3 bend (1454 cm-1) and the order ratio (R) was calculated as the ratio of C–COO stretching bend (875 cm−1) intensities for parallel and normal orientation of the polarizer relative to the direction of film drawing.

Surface properties. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, K-alpha, Thermo VG Scientific, East Grinstead, U.K.) investigated surface chemistry. Measurements were performed using monochromated Al source operated at 1486.6 eV, 12 kV, and 3 mA and 6.8 × 10−7 Pa working pressure and charge shifting were corrected based on the C1s (285.26 eV) and O1s (532.29 eV). Data were analysed using Spectral Data Processor software (ver. 4.3). Wettability was investigated using contact angle meter Theta Lite system (Biolin Scientific). The water contact angle (WCA) was measured using sessile drop method in which a drop of milli-Q water (5 μL) was placed onto the film surface (10 × 10 mm) and recorded for contacting angle. WCA results are mean values of at least three measurements. Surface morphology of films was investigated using scanning electron microscopy (JSM-7600 F, Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Piezoelectric properties. Piezoelectric response was measured as voltage output generated during mechanical deformation using US. The deformation was generated by 1MHz- US transducer (Mfd. Sun Medisys, Deltasound 1MHz) using US-conductive hydrogel (Ultragel Hungary 2000 Kft., Hungary) or by 80kHz US ultrasonic bath (80kHz, Elma, Elmasonic P) filled with water. Measurements were done for two positions of the copper electrodes- on the top and bottom of the film and on side edges of the film corresponding to their drawing direction and generated voltage was detected using a Kaysight MSOX3034T oscilloscope. The measurements were performed in at least three different films.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS). Dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR) assay[

24] has been applied for detecting the ROS generation by films with different contacting layer, before and after activation with US. The films (5 × 5 mm size) were put in 96-well plate containing physiological solution (0.9% NaCl). Testing included four 96 well plates with the same set of samples. Two of the plates were stimulated with 1MHz US while the remaining two stayed without stimulation. One of the stimulated and one of the non-stimulated plates were added vitamin C as an ROS scavenger (40 µL/well, 1 mg/ml). In addition, negative control was NaCl medium while positive control was H

2O

2 (5wt%) pre-irradiated with UV light. After addition of the DHR agent (10 µL per well, 0.1 mM) following the US stimulation, the samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and then measured for the fluorescence at 490/530 nm Ex/Em. All samples were tested in triplicate.

Human cell piezostimulation. Low passage HaCaT human keratinocytes (ATCC PCS-200-011) were grown in 6-well plates in full DMEM (with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin). PLLA films with different contacting layers (1 × 1 cm size) were immersed in poly-L-lysine solution (300 µL), washed with full DMEM and then seeded with HaCaT cells inside 24-well plates (20.000 cells/well). Two 24-well plates with the same set of samples were further incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 (MCO-19AIC(UV)-PE, Panasonic). After incubation, the films with adhered cells were replaced in new 24-well plates, and cell attachment was measured using Presto Blue Cell Viability Reagent (following the provided protocol). The reagent was washed with DPBS, and the plates were filled with the fresh full DMEM. Stimulation was done according to previously optimized protocol.[

16] One of the plates was stimulated with 1MHz US while the second stayed without stimulation. The stimulated plate was immersed in the Petri dish (20 cm diameter) filled with 100 mL of distilled water which was connected to the 1MHz US transducer (Mfd. Sun Medisys, Deltasound 1MHz) via thin layer of US transducing gel (Ultragel Hungary 2000 Kft., Hungary). The stimulation was done using 1:10 on:off intervals and 1.8-W/cm

2 power. Both plates were then transferred to a CO

2 incubator and incubation was followed during the next 24 h. The stimulation and Presto blue growth detection steps were repeated daily for the next 72 hours. Analysis was performed in at least two independent experiments, each time in three parallel experiments.

Total protein detection. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay was applied for quantifying the total protein levels following the protocol for 96 well plate. The protein levels were detected in cells adhered to the surface of films as well as in cells which proliferated on films for 72hour with or without piezostimulation. The total cell lysates were prepared by incubating films with cells in RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with enzyme inhibitors, scratching films surface to detach cells, separating the suspended cells / cell debris and their incubation at low temperature, sonication and centrifugation. All samples were tested in triplicate.

Actin filaments detection. Expression of actin was detected in cells grown at the surface of films with different contacting layers with or without stimulation. Detection was done in the final step after 72- hour stimulation and growth. The cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (3.7% solution in DPBS), permeabilized with Triton X 100 (0.5% solution in DPBS), washed with DPBS, and finally stained with RP (1 µl/ml) for actin and DAPI (5 µL/ml in Hank's balanced salt solution) for nuclei detection. RP fluorescence was detected at 584/562 nm Ex/Em, while DAPI was measured at 355/346 nm Ex/Em (Synergy H1, Biotec). The expression of actin was normalized to total cell number and presented as actin filaments per cell. The stained cells on top of films were also observed under a fluorescence inverted microscope (Eclipse Ti-U Nikon). Analysis was performed for three parallel samples and in at least two individual experiments.

Cell morphology detection. Morphological properties of HaCaT cells adhered and grown at the surface of films with different contacting layers with or without US stimulation was observed using SEM microscopy. Cells were fixed in glutaraldehyde (2.5w% in DPBS) for 2 h at room temperature. After fixation they were washed with DPBS and then gradually dehydrated using a series of ethanol dilutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 100%). In each of the ethanol solutions films with cells were incubated for 10 min and in the final 100% ethanol they were left for 30min. The last step was chemical drying which was done by incubating samples in 100% HMDS for 15 min, replacing the HDMS for the fresh amount of the drying agent which was then left to dry in air. Samples were sputtered with gold before examination in SEM (JSM-7600 F, Jeol Ltd.).

Statistical analysis. The results are presented as the mean values of at least three measurements (n = 3) and are indicated with standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA (GraphPad 9.0 Software) with a confidence level of 95% and p < 0.05.

3. Results

Processing PLLA into uniaxially drawn films, characterized by piezoelectric properties, always starts with hot pressing the polymer into non-drawn films (DR1). The hot pressing is performed by putting the polymer powder inside aluminium mold between two metallic surfaces. For easier detachment of the hot pressed PLLA DR1 film from the hot metallic surfaces another inert protecting layer in commonly applied. This protecting layer, here labelled as contacting layer, is supposed to be thermally resistant, it is quenched in cold water along with PLLA DR1 films and then physically separated from its surface. Here we investigated the influence of different contacting layers, including Teflon, Teflon S, Kapton (PI) and Paper, to the surface chemistry of finally processed PLLA DR5 films, their potential role in crystallization and structural properties of piezo-PLLA as well as their influence to the cells stimulated directly at the surface of these films, as illustrated in Fig.1.

Figure 1.

The concept of using different contacting layers for processing uniaxially drawn PLLA films to design their piezoelectricity and tailor ultrasound- activated piezo-stimulation of human cells.

Figure 1.

The concept of using different contacting layers for processing uniaxially drawn PLLA films to design their piezoelectricity and tailor ultrasound- activated piezo-stimulation of human cells.

3.1. Surface –Induced Crystallization of PLLA

After applying different contacting layers, including PI, Paper, Teflon or Teflon S, during the melt-pressing of the PLLA and PLLA HAp into DR1 films, the resulting films had macroscopically very different appearances (Fig. 2a). The XPS spectra confirmed F1s peak at the surface of PLLA processed with Teflon and Teflon S (corresponding to F in C-F bonds at 689eV)[

25] and N1s peak (corresponding to C-N at 400.1eV)[

26] at the surface of PLLA processed with PI, as well as their absence in XPS spectrum of non-processed PLLA granules. Based on these differences in surface chemistry we suspected that thin depositions of contacting layers remained on top of the processed films (Fig. 2b).

In further evaluation of the surface we investigated the wettability of films and confirmed that, in addition to the surface chemistry, different contacting layers affected the WCA of processed films. Initially hydrophobic surface of PLLA film has been changed after applying the contacting layer which definitely confirmed their presence on films surfaces (Fig. 2c). Particularly PLLA HAp films processed with PI contacting layer had practically the same WCA as PI itself. Low standard deviation (SD) for consecutive measurement along the film indicates its uniform coverage by PI. On the other hand, Teflon, Teflon S and paper contacting layers did not change the initial WCA of PLLA so intensively and, as SDs for different measurements were quite high, they pointed to variations of the wettability due to partial coverage of certain areas.

Next, we investigated potential contribution of contacting layers to the structural properties of PLLA films. According to 2D SAXS data the presence of the top layer significantly affected the structure of the polymer in PLLA and PLLA HAp films (Fig. 2e). Lower scattering around the central beam obtained for films with PI at the top indicated low long-range ordering which was not particularly increased in presence of HAp filler. In case of the presence of other contacting layers on top of PLLA films, the scattering is significantly intensified and it was further enhanced if HAp filler was present. While the intensity of scattering indicated the long-range ordering, the shape of the diffuse rings in 2D SAXS revealed the PLLA crystallite orientations. The elongated diffuse rings obtained for films drawn with paper, Teflon or Teflon S on the top (Fig. 2d) indicated the preferentially oriented crystallization. In addition to enhancing long-range ordering, the presence of the HAp filler further enhanced preferential crystallization. Increased long range ordering in PLLA and PLLA HAp films with different contacting layers was detected in 1D SAXS (Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

The influence of surface chemistry to PLLA crystallization. Physical appearance of PLLA HAp DR5 films pressed using different contact surfaces (paper, Teflon, Teflon S and PI) (a), XPS spectra of non-processed PLLA (b1) and PLLA processed with Teflon (b2) and PI (b3) confirming their presence at the surface; water contact angle of PLLA without surface layer (c1) and pairs of materials used as contacting layers (paper, Teflon, Teflon S and PI (c2-5)) and relative PLLA HAp DR5 films (c6-9); SAXS patterns showing difference in crystallization of PLLA and PLLA HAp films with different contacting layers (d); XRD patterns of hot-pressed (DR1) and drawn (DR5) PLLA (e1-4) and PLLA HAp (e5-8) films with different contact layers at the surface; DSC determined crystallinity (f) and polarized Raman spectroscopy determined orientation (g) of PLLA and PLLA HAp drawn films with different contacting layers at the surface.

Figure 2.

The influence of surface chemistry to PLLA crystallization. Physical appearance of PLLA HAp DR5 films pressed using different contact surfaces (paper, Teflon, Teflon S and PI) (a), XPS spectra of non-processed PLLA (b1) and PLLA processed with Teflon (b2) and PI (b3) confirming their presence at the surface; water contact angle of PLLA without surface layer (c1) and pairs of materials used as contacting layers (paper, Teflon, Teflon S and PI (c2-5)) and relative PLLA HAp DR5 films (c6-9); SAXS patterns showing difference in crystallization of PLLA and PLLA HAp films with different contacting layers (d); XRD patterns of hot-pressed (DR1) and drawn (DR5) PLLA (e1-4) and PLLA HAp (e5-8) films with different contact layers at the surface; DSC determined crystallinity (f) and polarized Raman spectroscopy determined orientation (g) of PLLA and PLLA HAp drawn films with different contacting layers at the surface.

The contribution of contacting layers on top of PLLA to crystallization has been seen already in initially formed DR1 films. In contrast to PLLA DR1 films with PI top which were amorphous (with or without HAp filler), the XRD patterns of other films confirmed the initial presence of α′ PLLA phase and its further crystallization during unidirectional drawing in PLLA DR5 films. In case of all crystallized films (110)/(200) preferentially oriented crystallization is observed. The crystallization was enhanced from PLLA films with PI toward paper to Teflon and Teflon S surface layers (Fig. 2e). Additionally the presence of HAp filler promoted the formation of β PLLA phase. Interestingly, in case of the Teflon and Teflon S contacting layers, the β PLLA phase has been detected in both PLLA and PLLA HAp films (Fig. 2e3,e4,e6,e7).

Figure 3.

The influence of contact layer to surface morphology of PLLA. Changing the roughness at the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with PI (a), Teflon (b), Paper (d) and Teflon S (e) at the top; the intensive roughness on the surface of PLLA DR5 films with Teflon (c1,2) and Teflon S (f1,2); the adhesion of contact layer to the surface of DR1 film during processing and its tearing during film drawing to DR5 (g).

Figure 3.

The influence of contact layer to surface morphology of PLLA. Changing the roughness at the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with PI (a), Teflon (b), Paper (d) and Teflon S (e) at the top; the intensive roughness on the surface of PLLA DR5 films with Teflon (c1,2) and Teflon S (f1,2); the adhesion of contact layer to the surface of DR1 film during processing and its tearing during film drawing to DR5 (g).

In contrast to increased preferential orientation in (200) direction, the total crystallinity based on DSC measurements did not show statistically relevant differences. Similarly the total molecular chain orientation was statistically increased for PLLA DR5 films with paper on top however these differences were lost in case of presence of HAp filler.

SEM investigations clearly confirmed the presence and morphological distribution of contacting layer at the surface of PLLA films (Fig. 3). While PLLA HAp DR5 films with PI at the top had very smooth surface, the roughness of films with paper and Teflon S was increased. The films with Teflon on top showed a variation for the case of presence of absence of HAp. The morphology explained the variations of the WCA along the films and confirmed the assumption about the smooth deposition of PI and partial presence of other contacting on PLLA films surface. Based on the observed morphologies it looked that contacting layers were not initially randomly deposited on some parts of the PLLA during processing DR1 films. Instead they were probably tore off during uniaxial drawing, as illustrated in Fig. 3g.

3.2. Ultrasound Activation of PLLA Films with Different Contacting Layers

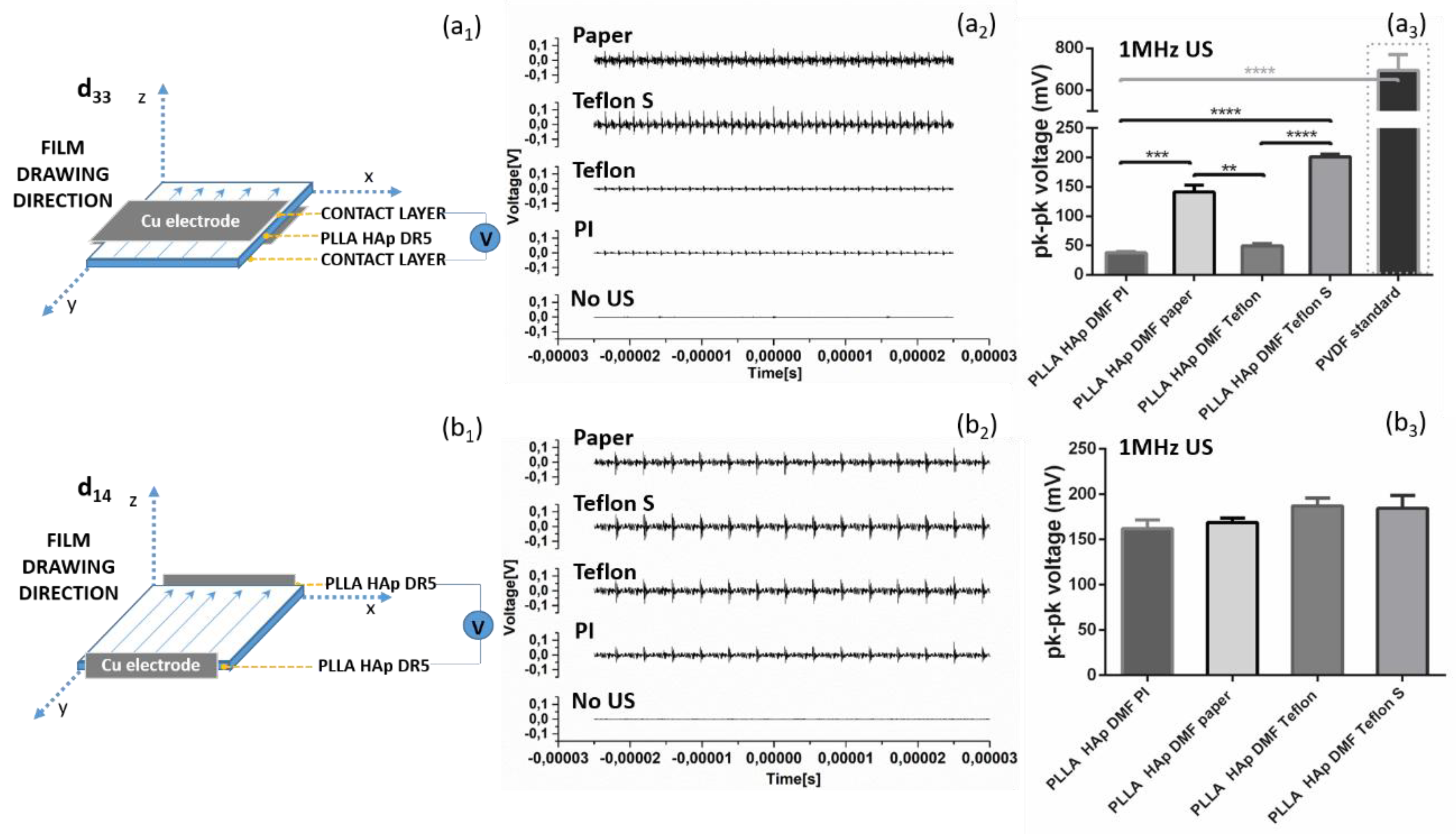

The differences in surface layers were directly percolated to ability of films to be activated by US. Depositing electrode at the top and bottom of the films (as illustrated in Fig. 4a1) provided significantly relevant variations in detected output voltages which depended on the type of contacting layer remained at their surface (Fig. 4a3). Despite these differences in intensity all of the films were responding to US activation (Fig. 4a2). Obviously there was a contacting layer in between the PLLA and electrodes, which covered either whole surface or just its parts (as detected in SEM images (Fig. 3), and therefore interfered with detecting the surface polarization and voltage output generation. In case when the electrodes were deposited on edges of the films, which correspond to films drawing directions (as illustrated in Fig. 4b1), the activation with US did not show very high variations between samples (Fig. 4b2). There was an increasing voltage output trend which followed the order from PI over paper to Teflon and Teflon S deposited on the surface of films which could be assigned to the contribution of these contacting layers to the oriented crystallization of the films, as seen in Fig. 2.

Figure 4.

Piezoelectric properties of PLLA films with different surface contact layers. Voltage signal in d33 direction (electrodes placed in direct contact with the contact layer) (a1), piezoelectric properties of films during mechanical deformation with 1MHz ultrasound (US) (a2) and resulted voltage signals which depend on the type of contact layer (a3) as well as voltage signal in d14 direction (electrodes placed on sides of the PLLA HAp films in direct contact with the PLLA HAp) (b1), piezoelectricity of the same films after mechanical deformation with 1MHz US (b2) and uniform voltage signal (b3), statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=4-5, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

Figure 4.

Piezoelectric properties of PLLA films with different surface contact layers. Voltage signal in d33 direction (electrodes placed in direct contact with the contact layer) (a1), piezoelectric properties of films during mechanical deformation with 1MHz ultrasound (US) (a2) and resulted voltage signals which depend on the type of contact layer (a3) as well as voltage signal in d14 direction (electrodes placed on sides of the PLLA HAp films in direct contact with the PLLA HAp) (b1), piezoelectricity of the same films after mechanical deformation with 1MHz US (b2) and uniform voltage signal (b3), statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=4-5, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

3.3. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Formation During Biomaterials Ultrasound Activation

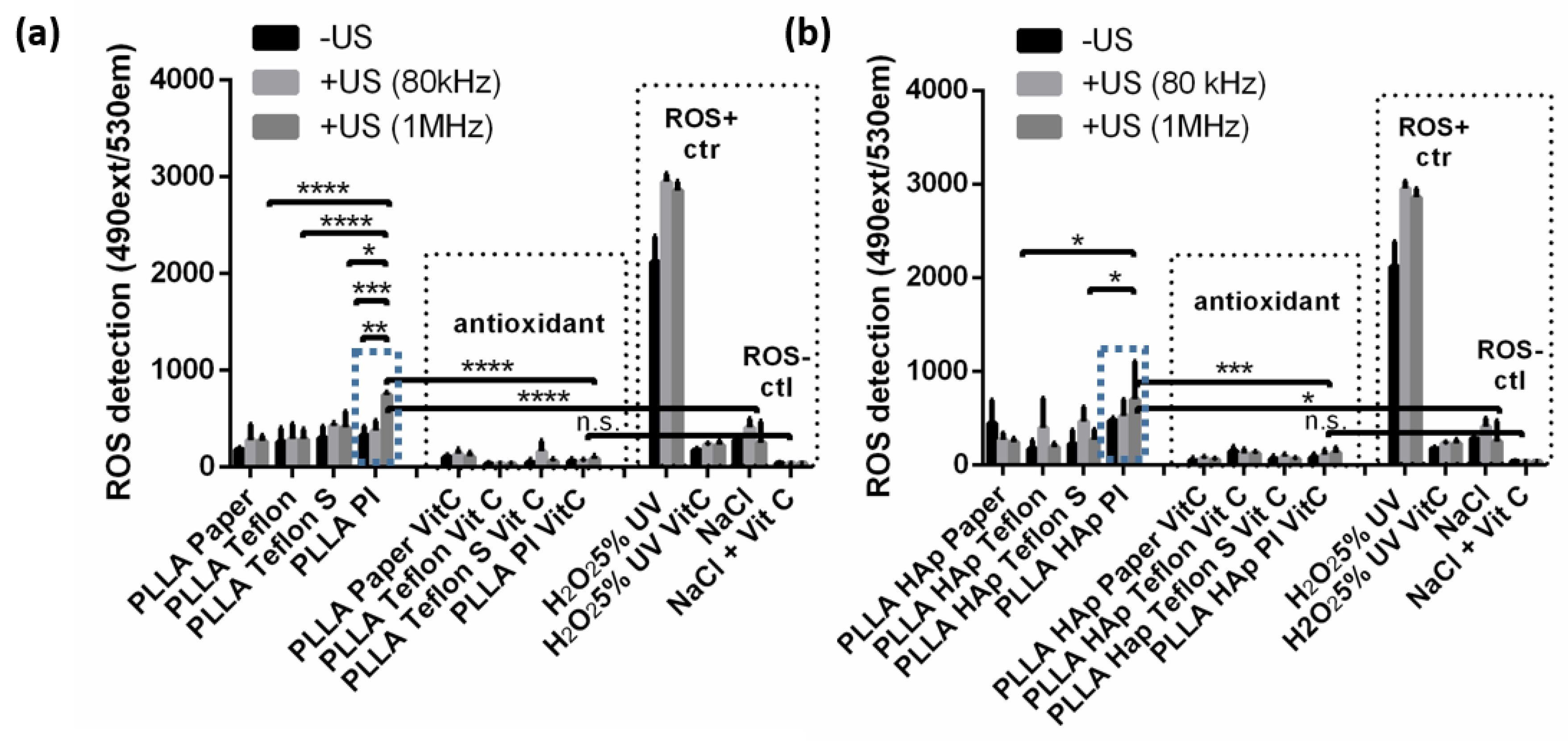

The presence of contacting layers at the surface of PLLA films affected ability of the films to produce ROS, particularly during mechanical activation with US (Fig. 5). The production of ROS has been measured using DHR assay and testing was done for the same PLLA and PLLA HAp films which differ only in type of contacting layer- paper, Teflon, Teflon S or PI. Testing was performed before and after activation with 80-kHz or 1MHz- US where films and all of the controls were activated by US or left without US treatment. As a detection control, the same set of films were tested with addition of vitamin C (Vit C) as antioxidant and ROS scavenger. In addition, ROS positive control was H2O2 (5wt%) pre-irradiated with UV lamp (with or without Vit C), while negative control was NaCl (with or without Vit C).

Figure 5.

The influence of contact layer to ROS formation during ultrasound activation. The ROS formation detected for PLLA (a) and PLLA HAp (b) films with Paper, Teflon, Teflon S and PI as contacting layers activated or non-activated with US (80kHz or 1MHz) (vitamin C (VitC) has been used as ROS scavenger, H2O2(5%)UV and non-treated cells as positive and negative controls); statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=3, *, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.05, p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

Figure 5.

The influence of contact layer to ROS formation during ultrasound activation. The ROS formation detected for PLLA (a) and PLLA HAp (b) films with Paper, Teflon, Teflon S and PI as contacting layers activated or non-activated with US (80kHz or 1MHz) (vitamin C (VitC) has been used as ROS scavenger, H2O2(5%)UV and non-treated cells as positive and negative controls); statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=3, *, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.05, p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

Looking at the controls (Fig. Fig. 5a,b) revealed that DHR detected high level of ROS in H2O2 and this level has been increased when treated with 80-kHz or 1MHz – US. Significantly lower level of ROS is detected in NaCl and its level was also slightly increased after activation with US. The high and low ROS levels detected in positive and negative control significantly dropped in case of presence of Vit C – confirming the validity of the method and quantitatively correlating detected signal directly to ROS production.

The PLLA and PLLA HAp films with paper, Teflon or Teflon S at the surface produced low levels of the ROS which was comparable to the ROS produced by NaCl solution with slight variations depend on the activation with US. The exception were PLLA and PLLA HAp films with PI at the surface. Initially the ROS production of these films was low, however after activation with US it has been significantly increased (relative to films with other type of contacting layers (p<0.05-0.0001) and also relative to NaCl negative control (p<0.0001)). Particular increase of the ROS production for PLLA PI and PLLA HAp PI films was achieved after activation with 1MHz US. In case of the presence of Vit C the ROS detected for all of the tested films dropped to very low level which was statistically similar to ROS produced by NaCl with VitC.

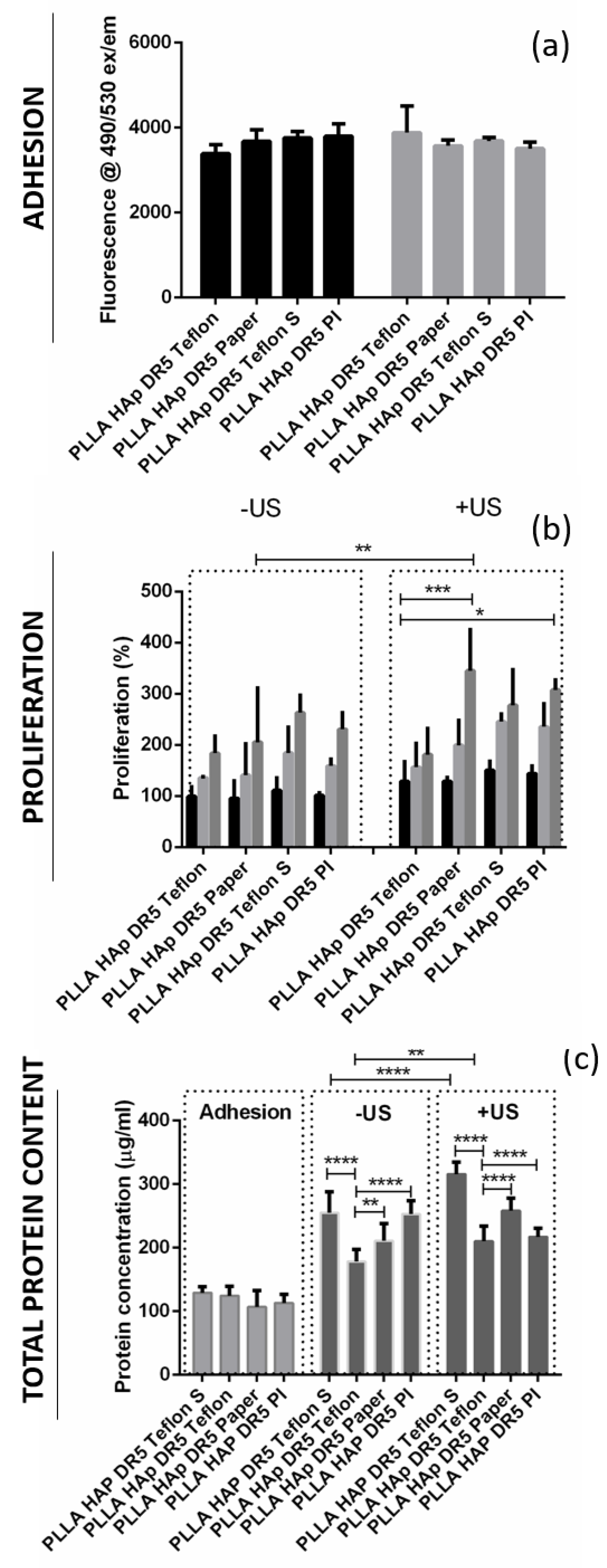

3.4. The Interactions of Human Keratinocyte (HaCaT) Cells with Ultrasound Activated Biomaterials

Initially, the cells were adhering on the films with different contacting layers (PI, Teflon, Teflon S and paper) in very similar manner- as observed based on very similar levels of their metabolic activity on these surface (Fig. 6a) as well as very similar total protein contents measured from lysates of cells extracted after adhesion on these surfaces (Fig. 6c). Metabolic activity of cells after adhesion was measured for two sets of the same samples as one of them was further activated with US while the second remained without US activation. Regardless to the type of contacting layer in both sets the differences of the cells adhered to the surface was statistically irrelevant. In this phase the metabolic activity and total protein expression correlated to number of adhered cells.

Figure 6.

Stimulated growth of HaCaT cells at the surface of ultrasound activated biomaterials. Cell adhesion (a), proliferation (b) and total protein content (c) at the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with different contact layers for the case of treatment with or without US, statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=3, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

Figure 6.

Stimulated growth of HaCaT cells at the surface of ultrasound activated biomaterials. Cell adhesion (a), proliferation (b) and total protein content (c) at the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with different contact layers for the case of treatment with or without US, statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=3, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

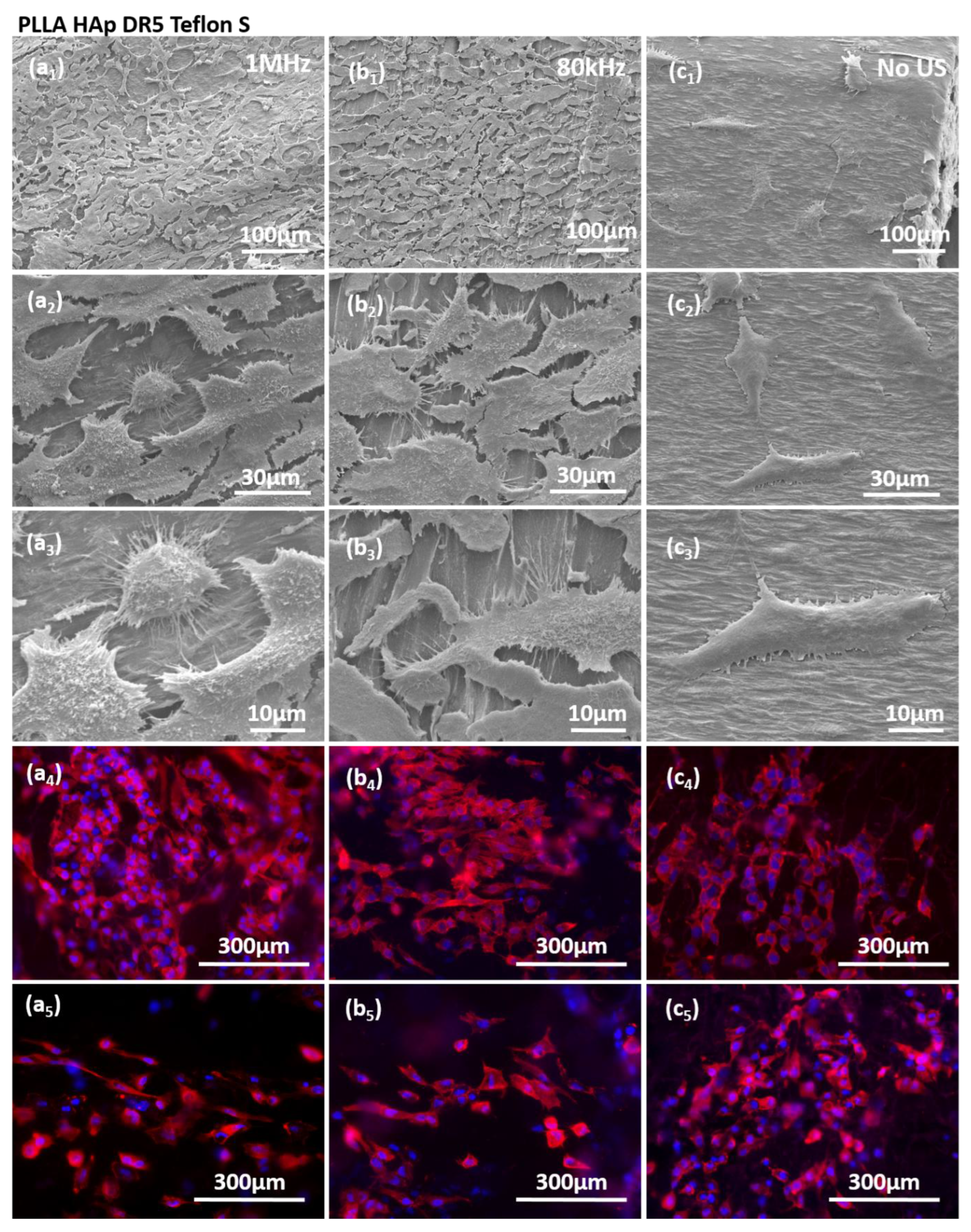

Figure 7.

Stimulated growth of HaCaT cells at the surface of ultrasound activated biomaterials. Cell adhe-sion (a), proliferation (b) and total protein content (c) at the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with different contact layers for the case of treatment with or without US, statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=3, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

Figure 7.

Stimulated growth of HaCaT cells at the surface of ultrasound activated biomaterials. Cell adhe-sion (a), proliferation (b) and total protein content (c) at the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with different contact layers for the case of treatment with or without US, statistical analysis was done for multi-comparisons, n=3, **, *** and **** refer to p<0.005, p<0.001 and p<0.0001, respectively.

During the proliferation phase, cells adhered to films with different contacting layers (PI, Teflon, Teflon S and paper) were analysed for two cases - with and without activation with US. Without US activation, both metabolic activity and total protein content were following the same order (Teflon < paper < PI < Teflon S) showing the increasing number of cells during proliferation on these surfaces (Fig. 6b,c). HaCaT cells were growing at the surface of PLLA HAp films with different contacting layers following the same fashion and without significant differences. However when growing on top of the films activated with 1MHz US the differences started to appear (p<0.005). The differences in metabolic activity (Teflon < Teflon S < PI < paper) and total protein contents (Teflon < PI < paper < Teflon S) occurred confirming the higher protein expression of cells grown at the surface of Teflon S which was not related only to the increased number of cells grown on this surface but also promoted another biochemical process potentially initiated by the stimuli transfer from this surface during piezostimulation.

Direct comparison of the proliferation of cells on films with different contacting layers with and without activation by US showed interesting correlations. Metabolic activity of cells grown on surfaces with different contacting layers activated with US was always higher than for the case when they were growing without US activation and the same trend followed the total protein content which was also statistically relevant (Fig. 6b,c). The exception were films with PI at the surface where protein content was decreased.

The stimulation of HaCaT cells on the surfaces of films with different contacting layers were further evaluated regarding the cell morphology and expression of actin filaments (Fig. 7, Fig. S2-S4). It should be highlighted that cells grown at PLLA HAp films covered with different contacting layers, including Teflon S (Fig. 7), paper (Fig. S2), Teflon (Fig. S3) and PI (Fig. S4), responded to US stimulation (either by 1MHz or 80kHz) by increasing the cell density. Stimulated cells were morphologically elongated and oriented with increased expression of actin filaments which indicated activation of the cytoskeleton as a response to the stimulation. We also detected higher production of cellular protrusions which cells used for connecting to the substrate and to other cells. Interestingly, the cells were favouring the regions without contacting layer, which is clearly seen in case of PLLA HAp Teflon S (Fig. 7b3), as contacting layer could be morphologically detected as “islands” at the surface of PLLA and cells were mainly occupying the area among them which confirmed their preference to stimulating structure and importance of direct contact between cells and piezo-structure as essential condition for transferring the signal during piezostimulation.

4. Discussion

Applying unidirectional mechanical force to the polymer softened solid, melt or solution is frequently used approach for ensuring oriented crystallization and enhanced molecular chains orientation as two essential parameters for obtaining piezoelectric structure in PLLA [

14], [

15]. In case of modifying polymer bulk, for example by adding low content (1wt%) of morphologically anisotropic fillers [

16], the additives affect heterogeneous crystallization, act as nucleating as well as direction agents, which promotes crystallization, additionally arrange structure and direct structural orientation.

Similar is observed in case of polymer blends when small addition of another polymer significantly affects crystallization and also mechanical characteristics of PLLA. As already proven, blending very low contents (below 10 wt%) of PTFE (Teflon) with PLLA provided significant mechanical reinforcement and toughening effect and increased elongation-to-break by 72%. PTFE also acted as homogeneous nucleating agent which promoted PLLA crystallization [

19]. Similarly, blends of PLLA with low contents of cellulose (2 wt%) increased melting elasticity and promoted PLLA crystallization [

20].

In contrast to modifying bulk, modifications of the polymer surface and its potential effect to crystallization and structure orientation are significantly less explored. Here we observed that depositing thin contacting layer at the surface of non-drawn PLLA films during hot-pressing very efficiently assists in enhancing the drawing force and contributes to oriented crystallization. Namely, contributions of the contacting layers comes from their thermal and mechanical properties. As illustrated in Fig.1, the contacting layers used in this study were all with increased thermal stability: paper, Teflon and Teflon S stable to the temperature up to 260⁰C and PI stable up to 400⁰C. In case of mechanical properties there were characterized by following: paper- inelastic, Teflon and Teflon S strong and reinforced, and PI elastic. During the hot-pressing phase, paper, Teflon and Teflon S were close to the limit of their thermal stability and they were thermally deposited on top of the PLLA surface. In the other hand, thermally more stable PI has been deposited mechanically due to its elasticity. Later during the drawing phase, deposited layers were stretched along with PLLA films. It is the point where their elasticity had the highest contribution.

The lowest contribution to structural properties of PLLA were coming from paper and PI applied as contacting layers. Although they were both adhered very well to the surface of PLLA, inelastic paper has been torn off easily in a very early phase of drawing while highly elastic PI (higher or equal to PLLA) has been easily drawn together with PLLA. As these two contacting layers did not produce any additional force during unidirectional drawing, their contributions to structural properties of PLLA were minimal.

Regardless to PI and paper, the contribution of Teflon and Teflon S were much higher. Previously it has been already noticed that tailoring properties of PTFE, by the application of different PTFE types, replicate in tailoring the influence it has to another polymers within the blend (like promoted mechanical strength, enhanced Young’s module, crystallization), as confirmed for poly(butylene succinate)/PTFE blend [

21]. Similarly, here we applied two types of PTFE as Teflon and Teflon S with two different mechanical strengths. As for PI and paper, the adhesion of Teflon and Teflon S on top of PLLA was strong enough to stay stable at their surface during drawing process. However, their elasticity has been better than paper, but still much lower than PI and PLLA. Consequently, Teflon and Teflon S were producing a friction force at the interface with PLLA, with the opposite direction to the drawing force. As Teflon S has been mechanically reinforced, the friction force produced with this layer was higher than for the Teflon. At some point, the Teflon and Teflon S elasticity limit has been reached and they were torn off at the surface of drawing PLLA. Morphologically it produced repeating “islands” of the contacting layer remained adhered along drawing direction to the surface of PLLA. The two opposite- side forces at the surface of PLLA were affecting the structural properties of drawn-induced crystallization of PLLA, including oriented crystallization and molecular chains orientation.

Previously we have observed that presence of morphologically anisotropic fillers, present during the drawing process, affects phase composition of the crystallizing polymer and contributes to the formation of low content of β PLLA phase [

16]. Interesting, the same contribution has been detected for Teflon and Teflon S when oppositely directed drawing and friction forces at the interface between PLLA and contacting layers also induced partial crystallization of PLLA into β PLLA phase.

As contacting layer contributed to crystallization and orientation, consequently they contributing to piezoelectricity of PLLA. However the presence of contacting layers at the surface was a barrier for effective transfer of the signal during activation with US, which was clearly detectable during measuring of the voltage outputs in two different set ups with and without partial presence of contacting layers between the activated PLLA and measuring electrodes. Similar barrier existed during piezostimulation of cells adhered on top of the films with PLLA. It was very interesting to see cells migrating among the “islands” of contacting layers reaching the area where they were in contact with the activated PLLA films. Here they were receiving the US-activated electro-stimuli which was transferred to them and increased the total protein content in cells and induced activation of cytoskeleton. The approach can be foreseen as very interesting tool for directing phases of cellular life and its application within advanced regeneration and tissue engineering approaches.

5. Conclusions

Adding contacting layer with optimal thermal and mechanical properties and ability to strongly adhere to the surface of the polymer is found to be very effective new tool for tailoring structural properties of uniaxially drawn films, optimizing their piezoelectric properties and consequently affecting their activation with US and interactions with human cells directly adhered to their surface.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: 1D graph extracted from 2D SAXS images for PLLA and PLLA HAp films with different contacting layers; Figure S2. SEM morphology of HaCaT cells on the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with Paper as contacting layer (distribution of cells, connections among cells and cell attachments to the surface) obtained without ultrasound (US) stimulation (a1-3) as well as after stimulation using 80kHz (b1-3) or 1MHz (c1-3) US; cytoskeleton of cells observed without (a4,5) and with US (80kHz (b4,5) or 1MHz (c4,5)) US stimulation; Figure S3. SEM morphology of HaCaT cells on the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with Teflon as contacting layer (distribution of cells, connections among cells and cell attachments to the surface) obtained without ultrasound (US) stimulation (a1-3) as well as after stimulation using 80kHz (b1-3) or 1MHz (c1-3) US; cytoskeleton of cells observed without (a4,5) and with US (80kHz (b4,5) or 1MHz (c4,5)) US stimulation; igure S4. SEM morphology of HaCaT cells on the surface of PLLA HAp DR5 films with PI as contacting layer (distribution of cells, connections among cells and cell attachments to the surface) obtained without ultrasound (US) stimulation (a1-3) as well as after stimulation using 80kHz (b1-3) or 1MHz (c1-3) US; cytoskeleton of cells observed without (a4,5) and with US (80kHz (b4,5) or 1MHz (c4,5)) US stimulation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.; methodology, L.G. and M.Z.; formal analysis, L.G. and M.Z.; investigation, M.V., L.G. and M.Z.; resources, M.V.; data curation, M.V., L.G. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.V..; writing—review and editing, L.G., M.Z., M.B., S.T..; visualization, M.V.; supervision, M.V.; X.X.; funding acquisition, M.V. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work has been supported by the Slovenian Research Agency (ARIS) (projects J3-14531, program P2-0091 and Slovenian-Serbian bilateral collaboration PR-12784).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in repository Zenodo doi: 10.5281/zenodo.17725263, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.17725392 and doi: 10.5281/zenodo.17725419.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the assistance of Franci Štern in processing PLLA and PLLA HAp films, David Fabijan for piezoelectric measurements and Blaž Jaklič for XPS investigations. We acknowledge CMS-Biocev ("Biophysical techniques, Crystallization, Diffraction, Structural mass spectrometry”) of CIISB, Instruct-CZ Centre, supported by MEYS CR (LM2023042) and CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/18_046/0015974.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PLLA |

Poly-l-lactide |

| PI |

Polyimide |

| PTFE |

Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| HAp |

Hydroxyapatite |

| DHR |

Dihydrorhodamine 123 |

| DMF |

N,N-Dimethylformamide |

| DR |

Drawing ratio |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium |

| BCA |

Bicinchoninic acid assay |

References

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Javanmardi, N.; Li, T.; Jin, F.; He, Y.; Zhu, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Feng, Z.Q. A review of recent advances of piezoelectric poly-L-lactic acid for biomedical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Joshi, R.; Sharma, M.K.; Huang, C.J.; Yu, J.H.; Wang, Y.L.; Lin, Z.H. The potential of organic piezoelectric materials for next-generation implantable biomedical devices. Nano Trends 2024, 6, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Sui, J.; Wang, X. Natural Piezoelectric Biomaterials: A Biocompatible and Sustainable Building Block for Biomedical Devices. ACS Nano 2022, 11, 17708–17728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Z. Design and Manufacturing of Piezoelectric Biomaterials for Bioelectronics and Biomedical Applications. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 9875–9929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simamora, P. & Chern, W. Poly-L-lactic acid: an overview. Journal of drugs in dermatology : JDD 2006, 5, 5–436. [Google Scholar]

- Elmowafy, E.M.; Tiboni, M.; Soliman, M.E. Biocompatibility, biodegradation and biomedical applications of poly(lactic acid)/poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) micro and nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Investig. 2019, 49, 347–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.D.; Kwon, Y.S.; Lee, K.S. Biodegradation and biocompatibility of poly L-lactic acid implantable mesh. Int. Neurourol. J. 2017, 21 (Suppl 1), S48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Yang, W.; He, T.; Wu, J.; Zou, M.; Liu, X.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Lai, C.; Wang, J. Clinical applications of a novel poly-L-lactic acid microsphere and hyaluronic acid suspension for facial depression filling and rejuvenation. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3508–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wen, K.; Liao, J.; Li, L. Ultrasound-activated piezoelectric biomaterials for cartilage regeneration. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 117, 107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinikoor, T.; et al. Injectable and biodegradable piezoelectric hydrogel for osteoarthritis treatment. Nat. Commun. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, T.; Fukada Eiichi. Electromechanical Properties of Poly-L-Lactic Acid. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 37, 3374–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, S.; Tofail, S.A.M.; Thompson, D. Organic piezoelectric materials: milestones and potential. NPG Asia Materials 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Bathaei, M.J.; Istif, E.; Karimi, S.N.H. & Beker, L. Biodegradable Piezoelectric Polymers: Recent Advancements in Materials and Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schönlein, R.; et al. Piezoelectric polylactic acid-based biomaterials: Fundamentals, challenges and opportunities in medical device design. Biomaterials 2026, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, Y.; et al. Advancing green electronics: tunable piezoelectric enhancement in biodegradable poly(l-lactic acid) PLLA films through thermal-strain engineering. Nanoscale Horizons 2025, 10, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukomanović, M.; et al. Filler-Enhanced Piezoelectricity of Poly-L-Lactide and Its Use as a Functional Ultrasound-Activated Biomaterial. Small 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udovc, L.; Spreitzer, M.; Vukomanovic, M. Towards hydrophilic piezoelectric poly-L-lactide films: optimal processing, post-heat treatment and alkaline etching. Polym. J. 2020, 52, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidlou, S.; Huneault, M.A.; Li, H.; Park, C.B. Poly(lactic acid) crystallization. Progress in Polymer Science 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; et al. Mechanical properties, crystallization characteristics, and foaming behavior of polytetrafluoroethylene-reinforced poly(lactic acid) composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; et al. Cellulose nanofiber reinforced poly (lactic acid) with enhanced rheology, crystallization and foaming ability. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; et al. The effect of polytetrafluoroethylene particle size on the properties of biodegradable poly(butylene succinate)-based composites. Sci. Rep. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevtić, M.; et al. Crystal structure of hydroxyapatite nanorods synthesized by sonochemical homogeneous precipitation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevtić, M. & Uskokovic, D.P. Influence of Urea as Homogeneous Precipitation Agent on Sonochemical Hydroxyapatite Synthesis. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aničić, N.; Vukomanović, M.; Koklič, T.; Suvorov, D. Fewer Defects in the Surface Slows the Hydrolysis Rate, Decreases the ROS Generation Potential, and Improves the Non-ROS Antimicrobial Activity of MgO. Small 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, J.; et al. XPS and FTIR studies of polytetrafluoroethylene thin films obtained by physical methods. Polymers (Basel). 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Gong, C.; Tian, X.; Yang, S.; Chu, P.K. Optical properties and chemical structures of Kapton-H film after proton irradiation by immersion in a hydrogen plasma. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).