1. Introduction

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing the global marketing environment at an unprecedented pace. However, the rate of adoption of AI-driven marketing systems varies significantly between different sectors. For example, larger corporations are increasingly relying on AI marketing systems to manage their customer relationships; however, smaller home-service based businesses — such as plumbers, electricians, HVAC technicians, home renovation contractors, and cleaning services — continue to manually collect, track, and manage customer inquiries. This disparity is concerning, given that home-service businesses compete in highly competitive environments in which timely responses to customers’ inquiries, effective lead qualification, and scheduling appointments directly impact a company’s revenues and customer satisfaction. However, this rapid integration brings multidisciplinary challenges that require a comprehensive agenda for research and practice (Dwivedi et al., 2021).

AI-based lead generation automation systems offer a great opportunity to help small service businesses automate the inquiry-to-appointment process, and therefore potentially greatly enhance their efficiency and profitability. Many AI-based lead generation systems include features such as automated chatbots and voice agents, CRM scoring algorithms, automated email/SMS responder capabilities, and calendar automation. However, despite the theoretical potential of AI-based lead generation automation systems to transform the way small service businesses interact with customers and generate new business opportunities, their actual adoption by small service businesses remains surprisingly low.

Previous research on AI adoption has primarily focused on large corporations, online retailers, and other organizations that have substantial amounts of data available to them. As a result, there is little published research on how small home-service businesses — with their own set of challenges — can leverage AI to enhance their operations and profitability. Specifically, small home-service businesses face unique challenges that limit their ability to adopt AI-based solutions, including:

* Limited digital literacy;

* Low budget constraints;

* Resistance to automation; and,

* Skepticism regarding the accuracy of AI-driven solutions.

Therefore, previous models of AI adoption are not applicable to this context.

This paper posits that the decision of a small home-service business to implement AI-based lead generation automation systems is influenced by a combination of behavioral, technological, and organizational factors. In particular, owner mindset, level of trust in the technology, perceived complexity of the technology, owner digital self-efficacy, accuracy of AI-driven automation processes, quality of the lead generation system, cost of implementing the technology, vendor support, and owner’s constraints related to resources will collectively determine whether or not a small home-service business will adopt and effectively utilize an AI-driven lead generation automation system.

There are two major gaps in the existing research base that this paper addresses:

Gap 1: There is a lack of AI adoption models specifically designed for micro-home-service businesses. Prior research on AI adoption has focused extensively on large corporations with formalized marketing departments. Small home-service businesses, on the other hand, are characterized by:

* Single-owner or 2–5 employees;

* Limited digital skills;

* No dedicated marketing staff;

* Inconsistent workflow;

* High volume of service calls;

* Unstructured lead handling.

The conditions described above create unique behavioral and technological barriers to AI adoption that have not been previously studied by researchers.

Gap 2: There is no prior conceptual model for AI-driven lead generation automation. Much of the prior research on AI in marketing has focused on customer experience applications, recommender systems, and predictive analytics. However, AI-based lead generation automation — particularly AI calling agents, qualification bots, and automated appointment scheduling systems — has been largely neglected in academic research. This is surprising, given that lead generation automation is likely the most important function for small service businesses and lead generation inefficiencies are the primary cause of customer loss among home-service businesses.

Purpose of the Study To develop a general conceptual model outlining how home service businesses adopt AI lead generation automation, while incorporating:

Behavioral Factors (Trust, Self-Efficacy, Risk Attitudes)

Technology Factors (System Quality, Accuracy, Integration Capability)

Organization Factors (Resources, Vendor Support, Owner Mindset)

Performance Outcomes (Lead Quality, Conversion Rate, Response Time, Revenue Impact)

Contributions of This Study This conceptual study provides contributions to the literature by:

Developing the First AI Adoption Framework Developed Specifically for Home Service Businesses

Integrating Behavioral, Technological and Performance Factors into One Unifying Model

Presenting Clear Conceptual Propositions to Guide Future Empirical Studies

Providing an Academic Rationale for Understanding the Adoption Dynamics of Practical Relevance

Identifying an Understudied Area of Marketing and Entrepreneurship

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

To comprehend why local home service businesses, characterized by limited digital literacy, constrained resources and a high reliance upon manual processes and work flows, would accept or reject AI driven lead generation automation, it is essential to go beyond one single theoretical lens. The extant literature on technology acceptance has been voluminous; however, much of it ignores the unique characteristics of micro enterprises operating in the manual trade sectors. This study integrates four well-established models of technology acceptance, namely the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), the Technology Organization Environment (TOE) framework and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory. This section will critically review each of the theories in the specific context of micro-enterprises operating in the service sectors to identify knowledge gaps and provide a solid theoretical foundation for the study.

2.1. The Context of Home-Service Businesses

The “Immediate Response” Imperative As opposed to e-commerce or SaaS companies founded in the digital era, home service businesses (e.g., HVAC, plumbing, landscaping, renovations) are fundamentally based in the physical environment. Their marketing challenges differ because they suffer from the “immediately responsive pressure.” Research indicates that 78% of consumers purchase from the first respondent (HubSpot, 2024). Consumers today are accustomed to on-demand services and expect rapid responses from their service providers — regardless if the consumer is booking a plumber or electrician. Nevertheless, many of the predominantly owner operated service firms have a structural limitation — the owner is typically the principal technician who works onsite at the customer location and thus cannot answer incoming phone calls. Consequently, home service businesses lose substantial revenue due to the lack of immediate response capability. AI-based lead generation automation (which combines voice agents, SMS bots and CRM scheduling) eliminates the human latency factor in responding to customer inquiries. Existing research on AI in marketing has largely focused on big data analytics for retail (Davenport et al., 2020) or programmatic advertising — thereby creating a void in the body of knowledge regarding the mechanisms for adopting operational automation in the micro-service sectors. Adopting the technology for a home service business is therefore not simply a matter of achieving “efficiency,” it is also a matter of “survival” in a marketplace where immediacy of response equates to revenue. This shift represents a strategic evolution in marketing, where AI moves beyond simple automation to feeling and thinking tasks that enhance customer engagement (Huang and Rust, 2021).

2.2. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in Micro Business Settings Davis’s (1989)

Technology Acceptance Model posits that Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) are the primary drivers of technology adoption.

Criticism of Perceived Usefulness: In a home service contracting business, usefulness is binary and financial. Does this tool generate additional jobs? Will this tool prevent me from missing calls? Typically, TAM studies examining “usefulness” assess usefulness from an employee productivity perspective. In the micro business context, we argue that “usefulness” is viewed by contractors as “capturing revenue.” If the AI system is viewed as merely a “high-tech chatbot” rather than as “a revenue generating tool,” the likelihood of adoption decreases.

Criticism of Perceived Ease of Use: This is a major impediment to adoption. Many home service business owners are trades people and not technologists. Therefore, complex dashboard interfaces, API keys and/or programming requirements can immediately deter adoption. Contractors require that the AI system be “invisible” or “touchless” to achieve the ease of use criteria in this industry — which is significantly higher than the ease of use criteria of large corporations.

Shortcoming: Although TAM explains the individual’s intention, it fails to consider the degree of support needed from outside entities to implement the technology. For example, a plumber may believe that AI is “useful”, but without a vendor providing support to install it, no adoption occurs.

2.3. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT/ UTAUT2)

Venkatesh et al. (2003, 2012) extended TAM to include social influences and facilitating conditions. These constructs have the following meanings in the context of AI lead generation:

Performance Expectancy: This construct extends the definition of TAM’s PU and includes the aspect of speed. Speed of lead response is the primary performance metric for service businesses. AI systems that offer “instant response” are likely to receive high performance expectancy scores.

Effort Expectancy: The amount of mental energy needed to learn the system. If AI agents require ongoing prompts or script training, they create high effort expectancy which generates resistance.

Facilitating Conditions: This is very important for this study. Since home-service businesses almost always do not have internal IT teams, they depend upon facilitating conditions – primarily the availability of third-party agencies (like white-label providers) to handle the back-end infrastructure. Without access to these supporting entities is one of the most significant barriers to adoption.

Hedonic Motivation: Hedonic motivation is relatively non-existent for contractors who purchase lead gen tools since the motivation is solely utilitarian (to survive and grow).

2.4. Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE)

Framework The TOE framework developed by Tornatzky and Fleischer (1990) offers great potential for adoption research at the organizational level, even for micro-enterprises.

Technology Context: This refers to the AI tool. Will the tool work with their current landlines? Will the AI voice sound natural so as not to offend customers? The reputational risk posed by “AI hallucinations” or inaccuracies can scare small local businesses who heavily rely on word-of-mouth. Contractors fear “technology failure” in front of a customer and this fear is a significant barrier to adopting an AI tool.

Organization Context: This includes the firm size, the firm’s slack resources, and the owner’s mindset. Most home-service firms have no slack resources. They are running at full capacity. Thus, AI adoption is often driven by necessity (e.g., “I don’t have a receptionist, therefore I am going to use an AI agent”) rather than a desire to be innovative.

Environment Context: This includes the competitive pressures and the customer’s willingness to accept AI-generated leads. As aggregators (such as Angi, Thumbtack, hipages) begin to utilize automation to provide leads to contractors, independent contractors will feel increasing environmental pressure to develop similar speed-enabling technologies to remain competitive.

2.5. Diffusion of Innovation (DOI)

Theory Rogers’ (2003) DOI theory extends the variables of “Observability” and “Trialability.”

Observability: Marketing operations are typically backend processes for home-service companies. Contractors cannot easily see competitors using an AI bot to book appointments. Contractors cannot visually observe the success of other contractors when they adopt AI tools, and therefore rely on agency case studies to evaluate the efficacy of AI-based lead generation.

Trialability: AI systems require extensive setup (number porting and API integrations), making them difficult for small business owners to “try out.” The “lock-in fear” created by low trialability discourages many contractors from adopting AI solutions due to their fear of becoming locked in to a particular solution.

2.6. The Role of Trust in Human-AI Interaction

Traditional adoption models emphasize utility; however, the fact that AI is an “autonomous agent” adds the additional factor of trust (Glikson and Woolley, 2020). Within the home services industry, there are two types of trust: trust in the technology (will it work?) and trust in the provider (do they understand my business?). Research has shown that people judge AI mistakes differently than they judge human mistakes (“algorithmic aversion,” Dietvorst et al., 2015); i.e., people tend to judge AI errors more harshly than human errors. For a small business owner who is reliant upon the local community to sustain their livelihood, the risk of an AI agent “hallucinating” or speaking rudely to a customer is a catastrophic risk, not just a minor glitch. Therefore, for this type of adoption model, “Reputational Risk Perception” is an important construct to include in addition to those constructs traditionally used in general IT adoption models.

2.7. Service-Dominant Logic (S-D Logic) and AI Vargo and Lusch’s (2004)

Service-Dominant Logic provides a useful lens for examining why contractors would resist purchasing DIY software, yet accept managed services. From an S-D Logic perspective, the contractor is not attempting to acquire a “good” (the AI software) but is seeking a “service” (appointments booked through AI). When AI is marketed as a tool requiring configuration, the contractor is forced to view the tool as a “goods-dominant” item, focusing on its technical features. When an agency provides the AI as a managed service outcome, it aligns with S-D Logic, where the value is co-created. This conceptual difference explains the emergence of “Done-For-You” (DFY) agencies in the SME sector: they convert a complex technological good into a consumable service, thus reducing the technical self-efficacy adoption barrier.

The study examines how the home-service micro-enterprise business owner responds to AI lead generation, specifically the factors that influence whether they intend to implement the technology. Based on a comprehensive review of literature from the past 20 years, we conclude that current theory has two major shortcomings when applied to the home-service micro-enterprise business owner. First, most of the literature assumes that there is some level of autonomy with regard to the implementation of technology; therefore, the literature does not account for the reality of many home-service businesses who have no choice but to purchase products or services that they are unable to fully control. Second, the literature largely assumes that the technology being implemented is simply “software,” which is easily implemented. As stated above, however, AI lead generation is fundamentally different than other types of software because it represents a complete paradigm shift with respect to how a home-service business interacts with its customers.

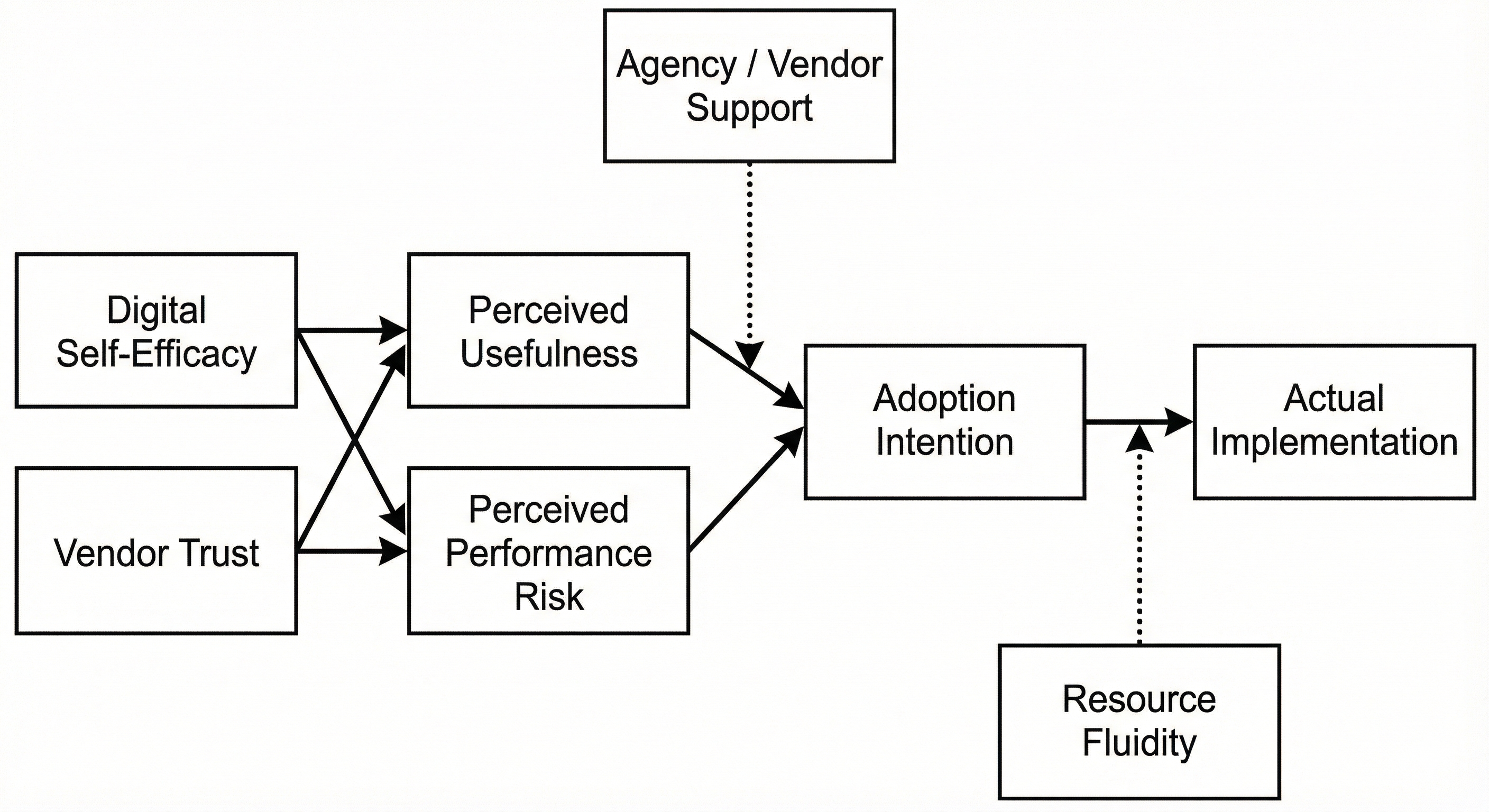

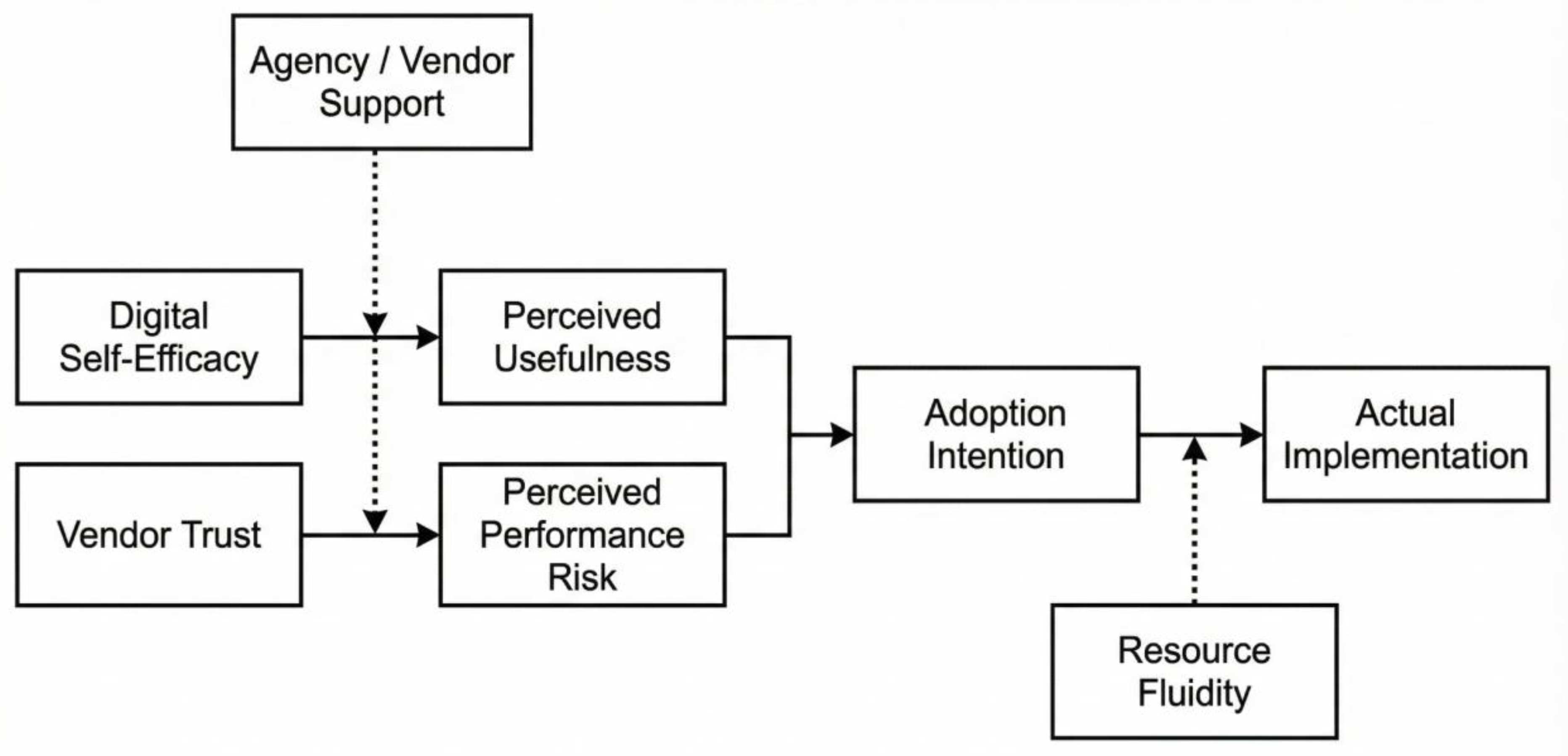

In order to address these limitations, we develop a conceptual framework that we call the Vendor-Supported AI Adoption Framework (VSAAF). The VSAAF identifies four primary constructs that drive the intention to adopt AI lead generation automation: (1) Digital Self-Efficacy, (2) Vendor Trust, (3) Perceived Performance Risk, and (4) Resource Fluidity. Each of the constructs that make up the VSAAF is described below.

3.1. The Interaction of Digital Self-Efficacy and Operational Complexity

In the technology acceptance literature, complexity is typically viewed as the cognitive load required to understand a new technology (Rogers, 2003). For example, if a new piece of software is difficult to learn and use, consumers may perceive that software to be too complex and therefore reject it. However, for a home-service business owner who is responsible for all aspects of the business (i.e., the CEO, the primary technician, and the customer service representative), complexity is not simply a matter of understanding the technical characteristics of a new technology. Rather, complexity also refers to the operational friction created by the need to change one’s manual workflow processes in response to the adoption of the new technology. For example, if an AI tool requires a home-service business owner to log into a dashboard between jobs in order to manage leads, the business owner would perceive that activity to create operational friction. This friction would contribute to the status quo bias inherent in all human decision making, wherein the known inefficiencies of manual lead handling are preferred to the unknown friction associated with digital transformation.

3.1.1. The Role of Digital Self-Efficacy

Social Cognitive Theory posits that self-efficacy is a primary driver of behavior change (Bandura, 1977). Specifically, social cognitive theory defines self-efficacy as an individual’s belief in their capability to execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations. In the context of information technology adoption, Compeau and Higgins (1995) found that “computer self-efficacy” was a critical determinant of technology usage. Home-service business owners typically have high “trade self-efficacy” (i.e., confidence in their vocational skills, e.g., plumbing or electrical work); however, they typically have low “digital self-efficacy” (i.e., confidence in configuring software or managing digital tools). Consequently, when users with low digital self-efficacy encounter high-tech solutions such as AI, they experience anxiety and avoid using the technology. Even if the AI tool is “low-code,” the terminology associated with the technology (e.g., “neural networks,” “training data,” “workflows”) can trigger a psychological barrier. Therefore, we assert that self-efficacy acts as a filter for PEOU. That is, a high-efficacy user will view a configuration dashboard as a flexible tool; whereas, a low-efficacy user will view the same dashboard as an insurmountable obstacle. Thus, the perception of ease is not an intrinsic property of the software, but rather it is relative to the user’s confidence.

Digital Self-Efficacy (DSE) is defined as an individual’s confidence in their ability to effectively use technology. While DSE has been demonstrated to influence technology adoption generally, the specific relationship between DSE and the PEOU of AI lead generation systems has yet to be explored in empirical research. Based upon prior studies of self-efficacy, it is expected that individuals with greater levels of DSE will find AI-based lead generation systems easier to use, while those with lower levels of DSE will avoid them altogether, regardless of their perceived ease-of-use.

Thus,

Proposition 1 (P1): Digital self-efficacy positively affects the Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) of AI lead generation systems; specifically, owners who have a high degree of digital self-efficacy will perceive AI-based lead generation systems as easier to configure, and therefore will be more willing to utilize them. Owners with lower levels of digital self-efficacy will be unwilling to utilize even simple AI-based lead generation systems.

In order to address the barrier of low self-efficacy in the adoption process, the literature on “technology intermediation” provides several mechanisms by which third party support can facilitate the adoption of technology by users who lack sufficient technical expertise to configure and utilize the technology themselves. One such mechanism is the provision of “done-for-you” (DFY) services, whereby the vendor or agency provides all of the technical support required for the effective utilization of the product. Unlike the SaaS model, wherein the user rents the product and is responsible for configuring and utilizing it, the DFY model sells the outcome of the product, thereby eliminating the user’s need for digital self-efficacy. Thus, the agency serves as a “complexity absorber” and the user’s need for technical expertise to utilize the product is greatly diminished.

Therefore, we expect that the negative effect of complexity on adoption will be mitigated by the level of vendor-provided support. Specifically, when vendor-provided support is very high (i.e. full implementation service), the complexity of the product will be deemed negligible by the user, and thus the user will be much more likely to purchase and utilize the product.

Thus,

Proposition 2 (P2): The negative relationship between System Complexity and Adoption Intention will be significantly moderated by the level of “done-for-you” (DFY) vendor-provided support. Specifically, the level of vendor-provided support will decrease the negative effect of complexity on the likelihood of adopting the product.

Vendor Trust as a Determinant of Perceived Usefulness

3.2.1. Black Box Anxiety

As discussed above, one of the primary concerns of micro-business owners regarding the adoption of AI-based lead generation systems is the “black box” nature of these systems. AI-based lead generation systems make decisions (e.g. how to respond to a lead) using algorithms that are unknown to the user. This creates significant anxiety for micro-business owners whose livelihoods depend on their local reputations. This anxiety is due to what is known in the literature as Algorithm Aversion (Dietvorst et al., 2015), wherein humans are more critical of AI errors than human errors. In a high-stakes environment such as the home-service market, the standard Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) construct of Perceived Usefulness (PU) is inadequate. Although a tool may be theoretically useful (it could save time), if the user does not trust the tool to perform social acceptable actions, then the user will not adopt the tool.

3.2.2. Multidimensional Trust: Competence, Benevolence, and Integrity

We adapted Mayer et al.’s (1995) integrative model of organizational trust to the context of AI vendors. Trust in an AI vendor is made up of three dimensions:

Competence Trust: Does the vendor have an adequate understanding of the unique aspects of your trade? An example of an AI that lacks competence would be a generalist AI that treats a “roof leak” the same way it treats a “clogged toilet”. An example of an AI that has a high level of competence is a vertical-specific AI (for example, “AI for Roofers”). The vertical-specific AI demonstrates that the bot will ask the correct qualifying questions, therefore giving the owner confidence that the bot will behave in a manner consistent with social norms.

Benevolence Trust: Will the vendor act in my best interest? If the AI causes problems (such as double-booking), will the vendor take care of the problem immediately, or will I have to spend hours trying to get help through the vendor’s support ticket system?

Integrity Trust: Is the vendor transparent about the limits of the AI? Over-promising (“The AI closes every lead!”) reduces integrity trust, while providing realistic expectations increases integrity trust.

3.2.3. Trust as a Precondition to Utility

We believe that in the home-service sector, vendor trust is a necessary precondition to the perception of usefulness of AI-based lead generation systems. If a contractor does not trust the vendor’s knowledge of the trade, he/she will reduce the perceived utility of the tool. He/she will assume that the AI will sound robotic, spammy, unprofessional, etc. On the other hand, if trust is established — often through industry-specific social proof or vertical specialization — the contractor is more likely to view the tool as a viable asset rather than a liability. This is consistent with Agency Theory (Eisenhardt, 1989), wherein the business owner (principal) delegates a task to the AI/agency (agent). The decision to adopt the tool is really a contract between the agent and the principal, based on the principal’s belief that the agent will not shirk his/her responsibilities nor damage the principal’s reputation.

Proposition 3 (P3): Vendor trust positively affects the perceived usefulness (PU) of AI-based lead generation systems. Business owners will be significantly more likely to assess AI-based lead generation systems as useful if the vendor is specialized in the contractor’s trade and if the vendor is transparent about the limitations of the AI.

3.3. Perceived Performance Risk And Trialability

3.3.1. Prospect Theory, Loss Aversion, And TAM

The TAM model looks at how much money new technologies can generate for businesses. Prospect theory suggests people experience losses (not getting something) more than gains (getting something). Loss aversion is especially strong in small businesses that operate on very tight margins. The loss of a single call from a home service business is an opportunity cost (a loss of a potential sale). But a poorly implemented AI could create a Perceived Performance Risk with unlimited potential for financial loss (customers posting negative comments on line, damaging the business’s reputation locally). Owners perform a mental accounting of the “risk of inaction” (manually missing sales leads) versus the “risk of automation” (AI makes errors). Due to the extreme consequences of a poorly implemented AI, many owners’ fears about the “risk of automation” exceed the pain of the “risk of inaction”. Since a significant portion of the marketing for many home service businesses is through word of mouth, the “reputational risk” is the major barrier to adopting AI tools in this industry.

3.3.2. The Lack Of Observability

DOI theory states that “observability”, the extent to which the effects of an innovation are visible to others, is a major factor in the diffusion of innovations. In the home service industry, backend functions are generally not observable. A plumber can’t easily observe whether his competitors are using an AI bot to fill job orders because he only sees his competitor’s van. Therefore, the lack of social observability increases the perception of risk since the owner does not feel validated by peers.

3.3.3. Trialability As A Risk Reduction Tool

One way to reduce Loss Aversion is to contain the risk. “Trialability” permits users to try the innovation with little or no risk. In the case of AI lead generation, “trialability” means allowing vendors to implement AI on segments of their leads rather than all of them (which would be high risk). Segmented implementation allows the owner to test the AI to determine its competency before risking exposure of their prime revenue stream. We assert that high levels of trialability directly mitigate Perceived Performance Risk and therefore open the door to Adoption Intentions.

Proposition 4 (P4): The greater the perceived performance risk (i.e., the greater the fear of reputational damage or the greater the fear of algorithmic error), the less the adoption intentions of owners, regardless of the amount of efficiencies generated by the technology.

Proposition 5 (P5): Trialability (i.e., being able to test the AI on a low-stakes segment of leads, e.g., reactivating contacts in the database who have not responded in 6 months) significantly reduces Perceived Performance Risk, and therefore increases the adoption intentions of owners.

3.4. Resource Fluidity: The Moderating Factor On Implementation

3.4.1. Beyond “Readiness”

The Concept Of Fluidity The TOE framework defines “organizational readiness” as a factor influencing the adoption of technological innovations. However, for micro-enterprises, “readiness” is far too general. We define the concept of “resource fluidity”. Micro-enterprises possess assets (equipment, vehicles, accounts receivable), however they generally do not possess sufficient liquidity. Adoption of AI tools requires two forms of liquid resources: Cash Flow (to pay for setup costs and subscription fees) and Time (to set up the system). Slack Resources Theory posits that organizations with excess capacity will innovate more. However, home service businesses are characterized by resource poverty (Welsh & White, 1981). The owner is generally operating at 110% capacity. He has no “time slack”.

3.4.2. The “Time Tax” Barrier

Although an AI tool may be free, it still represents a “time tax” — the number of hours required to learn, set up and maintain the tool. For example, if an owner operator of a plumbing business charges $100 per hour for his services, then the value of the 5 hours required to set up software is $500 in lost revenue. As a result, there exists a situation referred to as the “intention-behavior gap” where the owner intends to use the technology (has high intention) but cannot afford the time to cease working and begin the process of implementation.

3.4.3. Fluidity as a Gatekeeper

We suggest Resource Fluidity acts as a gatekeeper between Adoption Intention and Actual Implementation. A high-intention owner with low fluidity (no cash, no time) is stuck in a cycle of permanent delay. On the other hand, high fluidity allows immediate action. There are managerial implications for pricing models. Vendors that move from high initial CapEx (Capital Expenditure, e.g., $5,000 setup) to low monthly OpEx (Operating Expenditure, e.g., Pay-Per-Lead) reduce the need for Cash Fluidity, thus accelerating adoption. Also, vendors using DFY services reduce the need for Time Fluidity.

Proposition 6 (P6): Resource Fluidity (i.e., the available, liquid cash-flow and discretionary-time) positively affects the transformation of Adoption Intention into Actual Usage; High intention will not result in implementation if resource fluidity is critically low.

3.5. The Integrated Model: VSAAF

The Vendor-Supported AI Adoption Framework (VSAAF) illustrates the interactions mentioned previously. It describes a linear path from antecedents to consequences, interrupted by significant moderating factors:

Antecedents: Digital Self-Efficacy and Vendor Trust provide the initial inputs. Without either of these, the cognitive evaluation process cannot occur.

Cognitive Evaluation: The antecedents determine the user’s perception of Usefulness (Benefit) versus Performance Risk (Cost). The comparison of benefit and cost determines the psychological Adoption Intention.

Moderating Factors: The transition from antecedents to intention is greatly moderated by Agency/Vendor Support (Proposition 2). A robust agency presence can overcome low self-efficacy.

Outcome Realization: Finally, the transition from intention to actual implementation is controlled by Resource Fluidity (Proposition 6).

3.6. The Mediation Effect of Agencies (Intermediaries)

A novel element of this model is the formal acknowledgment of the Digital Agency as a mediator (intermediary) between the technology and the SME’s adoption process. Due to the large gap between the technological complexity of AI technologies (such as Large Language Models and Voice AI) and the SME’s ability to absorb such complexity, we do not believe that SMEs can bridge the gap directly. We propose that the digital agency functions as a “trust buffer” and a “complexity filter”.

As a trust buffer: The agency assumes the reputational risk. If the AI fails, the contractor blames the agency, not the technology, and therefore are more willing to attempt the use of the technology (because they have a throat to choke).

As a complexity filter: The agency abstracts the technology, hiding the back-end APIs and displaying only the “booked appointment” interface. This mediation effect accounts for why White-Label AI Platforms are expanding faster in the SME sector than direct-to-consumer AI tools. The agency provides the social scaffolding required for the technology to be embedded in the SME.

Proposition 7 (P7): The presence of a specialized intermediary (agency) mediates the relationship between Technology Complexity and Adoption; intermediaries eliminate the negative effect of complexity by taking over the technical setup burden and providing a layer of accountability.

4. Discussion

This paper developed a conceptual model to describe the adoption of AI-based lead generation automation in the micro-enterprise market of home service providers. Through the integration of TAM, DOI, and TOE, the proposed Vendor-Supported AI Adoption Framework (VSAAF) provides a detailed description of how tradespeople and contractors engage with advanced automation technologies.

4.1. Explaining the ‘Vendor-Dependent’ Paradigm

A primary discovery of this conceptual synthesis is the identification of a “vendor-dependent” adoption paradigm. Traditionally, literature assumes that technology adoption is an internal competence--that firms purchase technology and then learn to use it (Davis, 1989; Tornatzky and Fleischer, 1990). However, in the context of home service providers (plumbing, roofing, HVAC), our framework indicates that adoption is more about outsourcing complexity rather than developing capability. The interaction between Digital Self-Efficacy and System Complexity (Propositions 1 & 2) presents a paradox. While complexity usually discourages adoption, the introduction of AI agencies functioning as intermediaries eliminates this deterrent. If the AI tool is provided as a managed service--where the vendor manages the prompt engineering, API integrations, and CRM workflows--the complexity is eliminated from the view of the end-user. This is consistent with the Service-Dominant Logic in marketing, indicating that contractors are not purchasing software (good) but purchasing the result of “booked appointments” (service).

The authors provide some practical implications for both Home Service Business Owners looking to modernize and for Digital Agencies and AI Vendors looking to develop and sell AI-based solutions to the Home Service Market.

5.1. Implications for Home-Service Business Owners

Transition From A “Tool” To A “System” Perspective: Contractors will need to stop viewing AI as simply another tool (i.e., “a chatbot”) and instead view AI as a system designed to increase revenues through reduced lead leakage — i.e., responding to inquiries immediately while the contractor is busy on a job site.

Vendor-Specific Expertise Is Key: Contractors need to assess whether the vendors they select for AI development are specializing in their trade (i.e., “AI for Roofers,” etc.) versus selecting a generic AI platform. Vendors specializing in their trade are more likely to have developed scripts that address specific industry-related issues and are less likely to create a reputational risk for their clients.

Trialability Is Important: Contractors will need to test AI as part of a pilot program or trial to establish trust. Testing AI on a subset of leads (e.g., all after-hours calls; all older database leads) will allow them to adopt at a controlled level of risk and validate the “Perceived Performance Risk” component of the framework.

Strategic Recommendations for Micro-Enterprises

Avoid The “Pilot Trap”: Contractors will frequently test AI on their toughest leads (e.g., “Let’s see if it can handle this angry customer.”) to gauge how well the AI performs. This approach sets the AI up for failure and does little to establish trust. The framework advocates for a “Graduated Adoption Strategy” which starts with low-risk applications such as confirming appointment times via text, followed by medium-risk applications such as re-engaging inactive leads and finally moving to high-risk applications like handling incoming calls during peak hours. Gradually introducing AI to contractors at varying levels of risk will help to develop the “Trust” element of the framework.

Audit Your “Digital Surface Area”: Before adopting AI, contractors will need to ensure that their digital touch points are current and accurate. If a contractor’s digital calendar is not updated, an AI agent cannot schedule appointments using the calendar. As implied by the framework, “Organizational Readiness” is often nothing more than “Data Hygiene” — ensuring that the contractor’s pricing information and availability are digitized so that the AI can function properly.

Reframe the “Receptionist” Role: Contractors should view AI as an “Always-On” filter, not as a replacement for a human receptionist. The AI can handle the vast majority of routine queries (e.g., “How Much Will It Cost for a Quote?”, “Are You Open?”, etc.), freeing the contractor or his/her staff to concentrate solely on high-value conversion conversations. By adopting an “Augmentation Mindset,” contractors will be able to overcome the fear of being replaced by AI.

5.2. Implications for Digital Agencies and AI Vendors (The Intermediary Role)

This section provides strategic guidance for digital agencies and AI vendors who are involved in bringing AI to the home service market based on the experiences and lessons learned from digital marketing practitioners.

The “Trust Buffer” Strategy: Agencies must act as a “trust buffer” between the contractor and the AI technology. While marketing the “complexity” of LLMs may attract certain types of developers, it also increases perceived complexity for many contractors. Rather, agencies should emphasize the invisibility of the AI technology. Contractors should be focused on seeing booked appointments appear on their calendars rather than being told about advanced neural networks.

Vertical-Specific Training Data: Vertical-specific pre-training data will allow vendors to establish trust with their customers. An example would be an AI agent for a plumber needs to know when a “drain is blocked” is a critical issue vs. when they need a “quote for a bathroom renovation”. Vendors who have agency-pretrained models that are aware of the vertical significantly decrease the adoption threshold by increasing perceived usefulness and decreasing the amount of work required to set up the solution.

Addressing the Liquidity Barrier: With recognition that resource fluidity (cash flow) is a significant barrier, agencies could explore “performance-based” or “pay-per-appointment” pricing models. The performance-based model will allow both parties’ incentives to be aligned; therefore, it will mitigate the financial risk barrier. Therefore, transitioning from a significant upfront CapEx (capital expenditure) to an OPEX (operating expense) model, vendors will be able to increase the rate of diffusion into micro-enterprises.

5.3. Social Implications

The widespread use of AI lead generation in the home service sector has many social economic implications. AI tools can aid in democratizing the marketplace for micro-enterprises by providing them with the ability to respond to inquiries faster and be viewed as more professional than larger aggregators. As such, independent tradespeople will be able to maintain autonomy and profitability without having to become part of large franchise networks or pay exorbitant fees to lead selling platforms. Additionally, this will foster a more diverse and resilient local service economy.

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although this paper provides a new theoretical perspective for the adoption of AI in the micro-enterprise home service sector, there are some limitations associated with this paper. However, these limitations represent opportunities for further research.

6.1. Limitations

First, the proposed Vendor-Supported AI Adoption Framework (VSAAF) is a conceptual paper and, therefore, is based upon the synthesis of existing literature and practitioner experience rather than empirical data. Although the paper is grounded in well-established theories (TOE, TAM, DOI), the correlation between the proposed constructs (Vendor Trust and Perceived Usefulness) must be validated statistically. Second, the scope is limited to “lead generation automation”. AI technology can also be applied to other aspects of the home service trade (e.g., predictive maintenance for HVAC equipment, automated quoting software) and may follow different adoption patterns. Third, the framework assumes a market environment where high-speed internet access and competitive digital marketing environments exist (e.g., Australia, U.S.A., U.K.). In developing markets where word-of-mouth still exists as the primary source of information and digital infrastructure is fragmented, the environmental pressure to adopt AI is likely to be much lower.

6.2. Directions for Future Research

There are several directions that future researchers could take to validate and extend the VSAAF model:

Empirical Validation: Researchers should develop a measure for “Digital Self-Efficacy in Trades” and conduct structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the proposed model. A survey of 300 + independent contractors (electricians, plumbers) would provide the sample size to validate whether Vendor Trust acts as a mediator for the relationship between complexity and adoption.

The “Human-in-the-Loop” Paradox: Future studies should investigate at what level of automation causes customer pushback. At what point does an AI voice agent become too robotic for a local service customer? Research is needed to define the appropriate trade-off between AI efficiency and human empathy in high-trust service trades.

ROI Analysis Over Time: Most of the discussion of the benefits of AI adoption has been based upon vendor promises of ROI. Academic rigor requires independent, longitudinal studies tracking the actual revenue impact of AI adoption on micro-businesses over 12-24 months. Does the “time tax” of setting up an AI system ultimately result in “time slack”, or does maintaining the AI system create a new burden?

Comparative Study of Intermediaries: Research should examine the adoption rates of businesses utilizing “do-it-yourself” (DIY) platforms compared to those utilizing “do-it-for-you” (DIFY) agencies. This study will empirically support proposition 7 regarding the mediating role of specialized intermediary agents.

7. Conclusions

AI-driven lead generation automation represents a major paradigm shift in the home service industry. For decades, the “digital divide” has separated large organizations with dedicated marketing departments from owner-operated micro-enterprises. AI can act as a bridge across the digital divide, provided that the barriers to adoption are accurately understood. The authors argue that small business owners are hesitant to use technology as a result of assessing the costs and benefits of technology, and not as a result of an inability to understand how it works. To illustrate the point, if a plumber or contractor misses a phone call, they lose a job, whereas losing an interaction with a bad AI would cost the plumber his reputation.

Therefore, the key to using AI with all segments of the population is to create trusted and easy-to-use environments supported by the technology vendors. Once those elements are in place, the users’ fears about the ability to use AI will diminish greatly. As such, the success of AI in the trade sectors will not depend upon the complexity of the algorithms used; it will depend upon the ease of use.

References

- Bandura, A. (1977), “Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change”, Psychological Review, Vol. 84 No. 2, pp. 191–215.

- Compeau, D.R. and Higgins, C.A. (1995), “Computer self-efficacy: development of a measure and initial test”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 189–211.

- Davenport, T., Guha, A., Grewal, D. and Bressgott, T. (2020), “How artificial intelligence will change the future of marketing”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 24-42.

- Davis, F.D. (1989), “Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 319-340.

- Dietvorst, B.J., Simmons, J.P. and Massey, C. (2015), “Algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol. 144 No. 1, pp. 114-126.

- Dwivedi, Y.K., Hughes, L., Ismagilova, E., Aarts, G., Coombs, C., Crick, T. and Williams, M.D. (2021), “Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 57, p. 101994.

- Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989), “Agency theory: an assessment and review”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 57–74.

- Glikson, E. and Woolley, A.W. (2020), “Human trust in artificial intelligence: Review of empirical research”, Academy of Management Annals, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 627-660.

- Huang, M.H. and Rust, R.T. (2021), “A strategic framework for artificial intelligence in marketing”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 49 No. 1, pp. 30-50.

- HubSpot (2024), “The 2024 Sales Trends Report”, HubSpot, available at: https://www.hubspot.com/hubfs/HubSpots%202024%20Sales%20Trends%20Report.pdf (Accessed 20 November 2025).

- Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H. and Schoorman, F.D. (1995), “An integrative model of organizational trust”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 709–734.

- Rogers, E.M. (2003), Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed., Free Press, New York, NY.

- Tornatzky, L.G. and Fleischer, M. (1990), The Processes of Technological Innovation, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

- Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2004), “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 68 No. 1, pp. 1-17.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B. and Davis, F.D. (2003), “User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 425-478.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J.Y. and Xu, X. (2012), “Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology”, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 157-178.

- Welsh, J.A. and White, J.F. (1981), “A small business is not a little big business”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 59 No. 4, pp. 18–32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).