Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

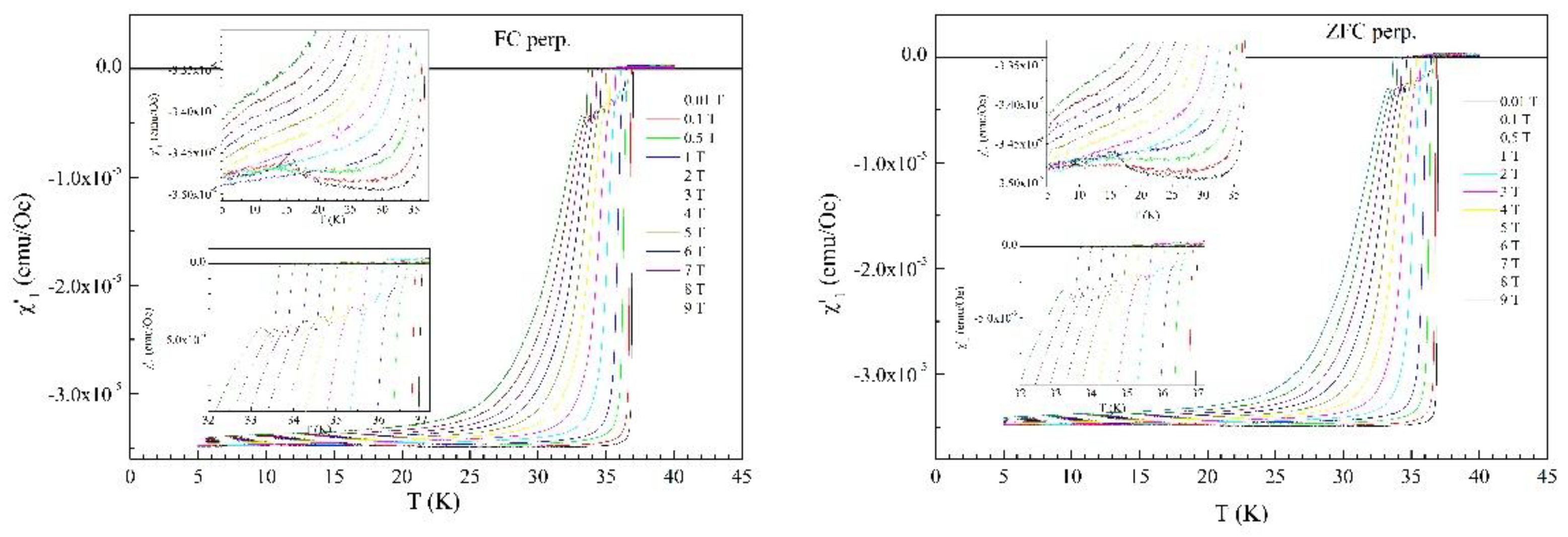

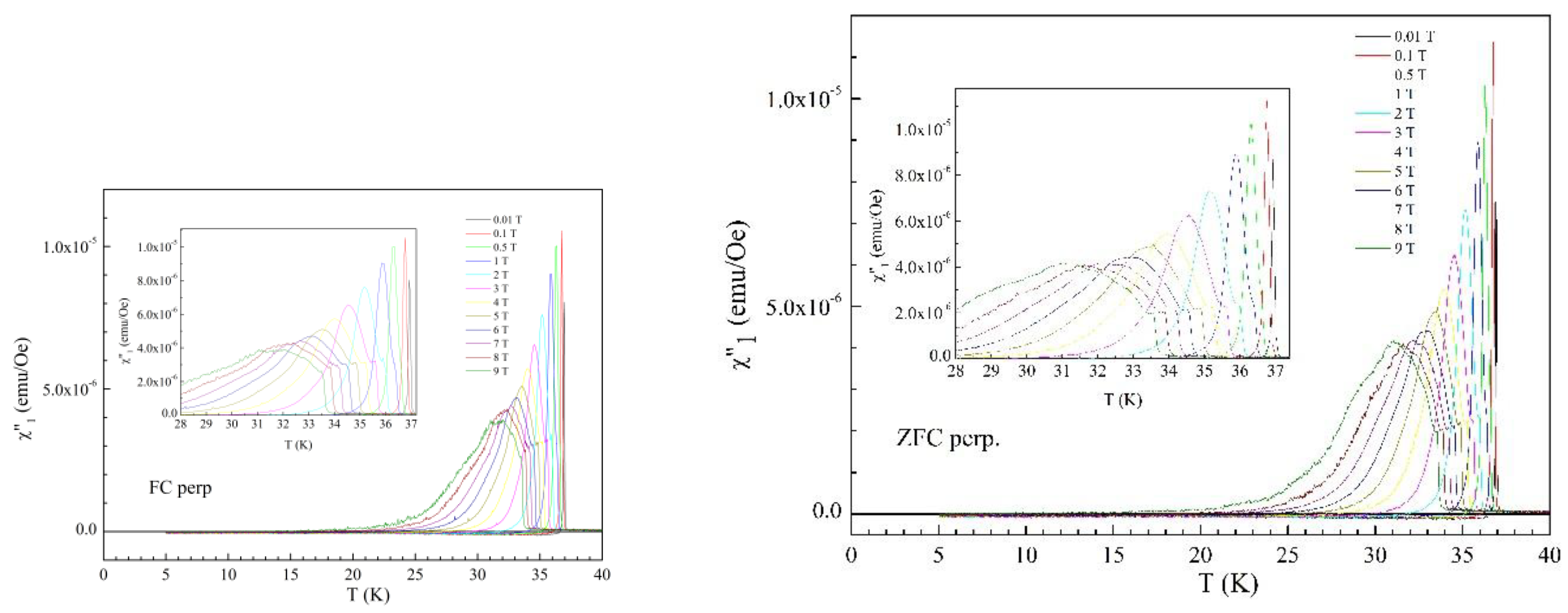

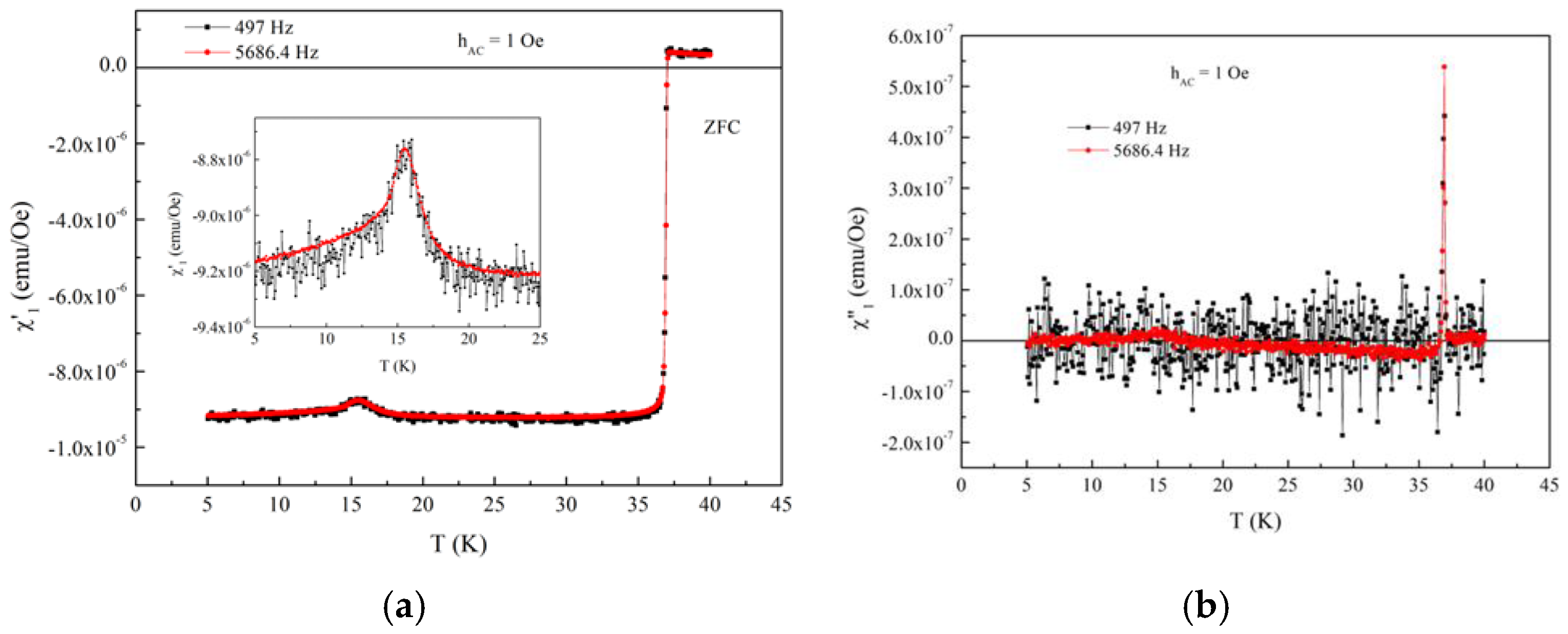

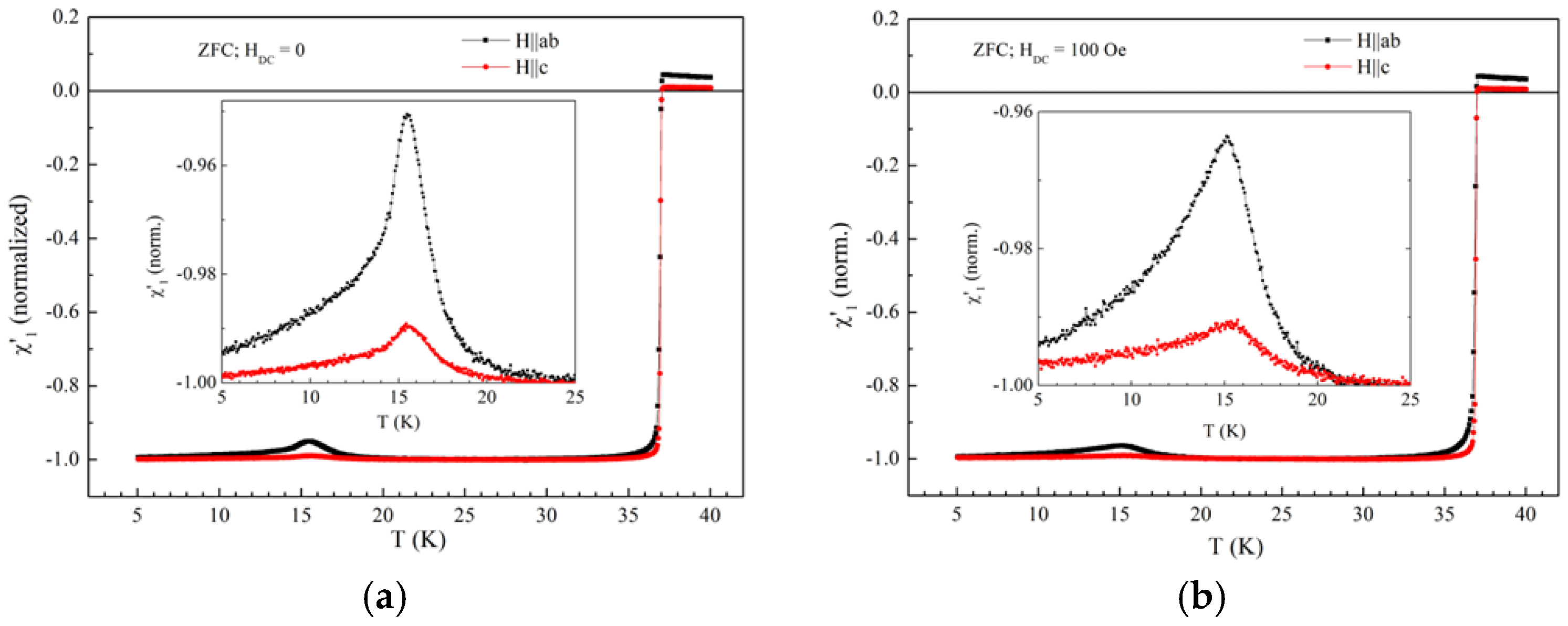

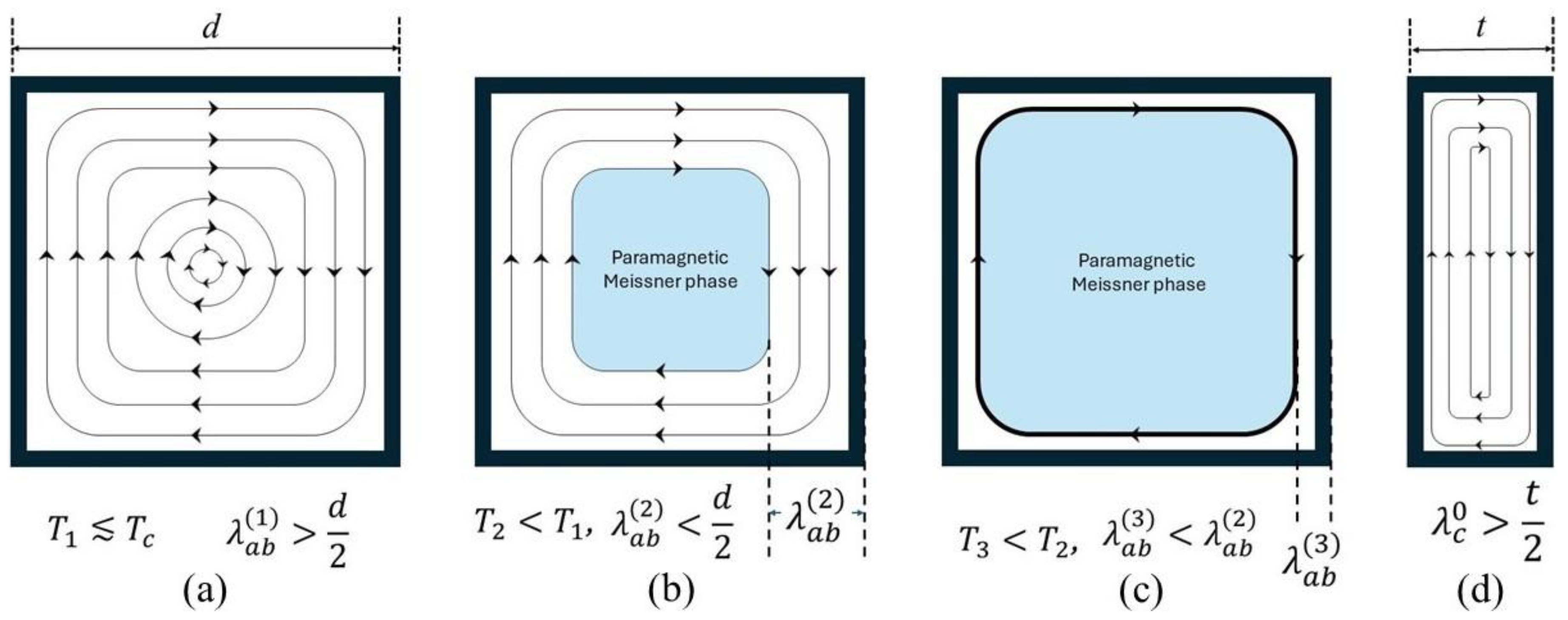

3.1. Fields Perpendicular to the Superconducting Planes

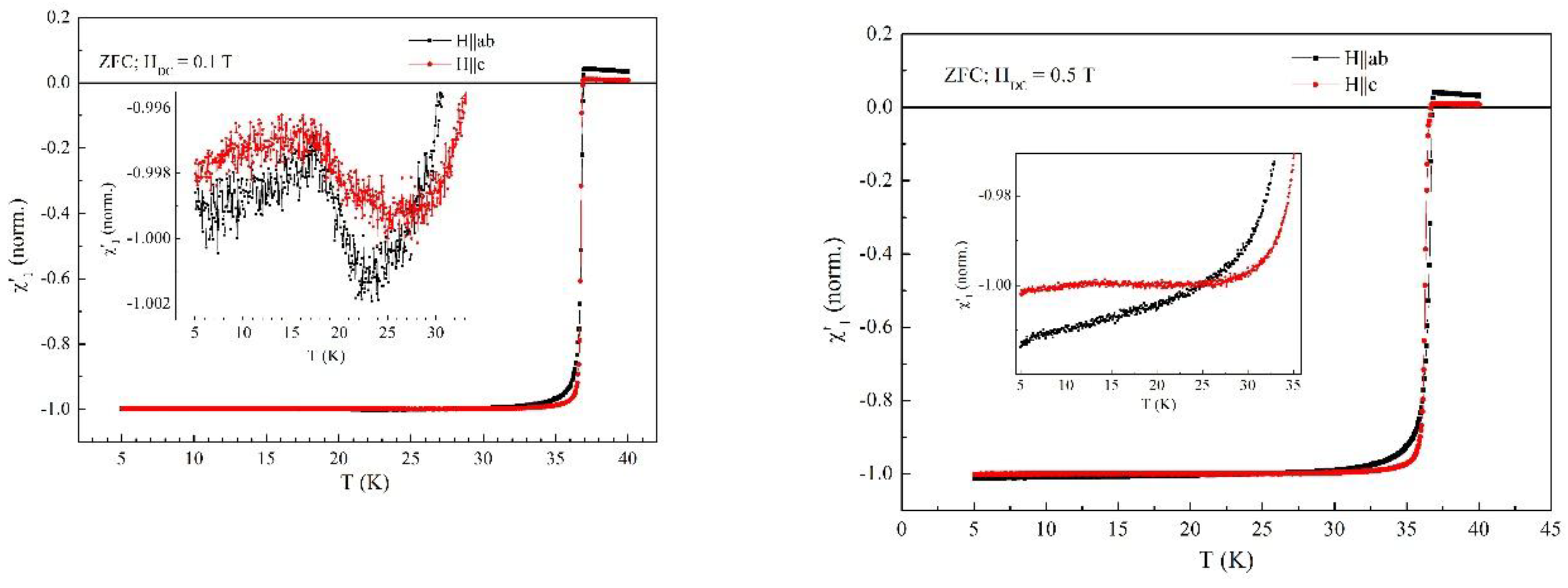

3.2. Fields Parallel with the Superconducting Planes

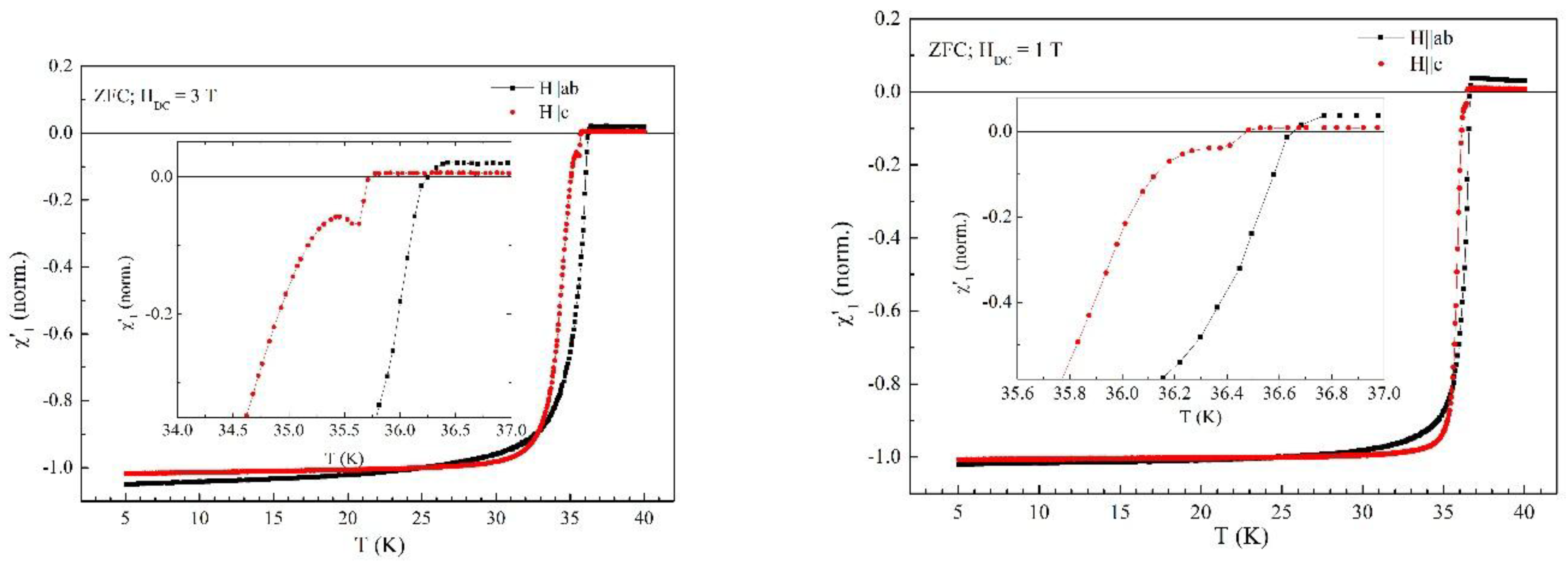

3.3. Comparison Between Perpendicular and Parallel Configurations

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| IBS | Iron-based superconductors |

| AE | Alkali-earth metal |

| A | Alkali metal |

| AEA1144 | AEAFe4As4 |

| FM | Ferromagnet/Ferromagnetic |

| ZFC | Zero-field cooling |

| FC | Field cooling |

| DC | Direct current |

| AC | Alternate current |

| PPMS | Physical Properties Measurement System |

| ACMS | Alternate Current Measurement System |

References

- Kamihara, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Hirano, M.; Hosono, H. Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1-xFx]FeAs (x= 0.05-0.12) with Tc = 26 K. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2008, 130, 3296–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotter, M.; Tegel, M.; Johrendt, D. Superconductivity at 38 K in the iron arsenide (Ba1-xKx)Fe2As2. Physical Review Letters 2008, 101, 107006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.Q.; Singleton, J.; Balakirev, F.F.; Baily, S.A.; Chen, G.F.; Luo, J.L.; Wang, N.L. Nearly isotropic superconductivity in (Ba,K)Fe2As2. Nature 2009, 457, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altarawneh, M.M.; Collar, K.; Mielke, C.H.; Ni, N.; Bud’Ko, S.L.; Canfield, P.C. Determination of anisotropic Hc2 up to 60 T in Ba0.55K0.45Fe2As2 single crystals. Physical Review B - Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2008, 78, 220505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyo, A.; Kawashima, K.; Kinjo, T.; Nishio, T.; Ishida, S.; Fujihisa, H.; Gotoh, Y.; Kihou, K.; Eisaki, H.; Yoshida, Y. New-Structure-Type Fe-Based Superconductors: CaAFe4As4 (A = K, Rb, Cs) and SrAFe4As4 (A = Rb, Cs). Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 3410–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, A.M.; Ivan, I.; Crisan, D.N.; Galluzzi, A.; Polichetti, M.; Ishida, S.; Iyo, A.; Eisaki, H.; Crisan, A. Pinning potential in highly performant CaKFe4As4 superconductor from DC magnetic relaxation and AC multi-frequency susceptibility studies. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, K.; Kinjo, T.; Nishio, T.; Ishida, S.; Fujihisa, H.; Gotoh, Y.; Kihou, K.; Eisaki, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Iyo, A. Superconductivity in Fe-Based Compound EuAFe4As4(A=Rb and Cs). Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 2016, 85, 064710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Bin; Tang, Z.T.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z.C.; Ablimit, A.; Jiao, W.H.; Tao, Q.; Feng, C.M.; Xu, Z.A.; et al. Superconductivity and ferromagnetism in hole-doped RbEuFe4As4. Physical Review B 2016, 93, 214503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albedah, M.A.; Nejadsattari, F.; Stadnik, Z.M.; Liu, Y.; Cao, G.H. Mössbauer spectroscopy measurements on the 35.5 K superconductor Rb1-δEuFe4As4. Physical Review B 2018, 97, 144426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, K.; Nagai, Y.; Ishida, S.; Ishikado, M.; Murai, N.; Christianson, A.D.; Yoshida, H.; Inamura, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Nakao, A.; et al. Coexisting spin resonance and long-range magnetic order of Eu in EuRbFe4As4. Physical Review B 2019, 100, 014506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smylie, M.P.; Willa, K.; Bao, J.K.; Ryan, K.; Islam, Z.; Claus, H.; Simsek, Y.; Diao, Z.; Rydh, A.; Koshelev, A.E.; et al. Anisotropic superconductivity and magnetism in single-crystal RbEuFe4As4. Physical Review B 2018, 98, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, S.; Kagerbauer, D.; Holleis, S.; Iida, K.; Munakata, K.; Nakao, A.; Iyo, A.; Ogino, H.; Kawashima, K.; Eisterer, M.; et al. Superconductivity-driven ferromagnetism and spin manipulation using vortices in the magnetic superconductor EuRbFe4 As4. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2021, 118, e2101101118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, J.K.; Willa, K.; Smylie, M.P.; Chen, H.; Welp, U.; Chung, D.Y.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Single Crystal Growth and Study of the Ferromagnetic Superconductor RbEuFe4As4. Crystal Growth and Design 2018, 18, 3517–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolyarov, V.S.; Casano, A.; Belyanchikov, M.A.; Astrakhantseva, A.S.; Grebenchuk, S.Y.; Baranov, D.S.; Golovchanskiy, I.A.; Voloshenko, I.; Zhukova, E.S.; Gorshunov, B.P.; et al. Unique interplay between superconducting and ferromagnetic orders in EuRbFe4As4. Physical Review B 2018, 94, 140506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.M.; Ivan, I.; Miclea, C.F.; Crisan, D.N.; Galluzzi, A.; Polichetti, M.; Crisan, A. Vortex Dynamics and Pinning in CaKFe4As4 Single Crystals from DC Magnetization Relaxation and AC Susceptibility. Condensed Matter 2023, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Ionescu), A.M.B.; Ivan, I.; Miclea, C.F.; Crisan, D.N.; Galluzzi, A.; Polichetti, M.; Crisan, A. Magnetic Memory Effects in BaFe2(As0.68P0.32)2 Superconducting Single Crystal. Materials 2024, 17, 5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, A.; Crisan, A.; Badea Ionescu, A.M.; Ivan, I.; Leo, A.; Grimaldi, G.; Polichetti, M. Multiharmonic AC magnetic susceptibility analysis of the rhombic-to-square transition in the Bragg vortex glass phase in a BaFe2(As1−xPx)2 crystal. Results in Physics 2025, 78, 108500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasko-Vlasov, V.K.; Welp, U.; Koshelev, A.E.; Smylie, M.; Bao, J.K.; Chung, D.Y.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Kwok, W.K. Cooperative response of magnetism and superconductivity in the magnetic superconductor RbEuFe4As4. Physical Review B 2020, 101, 104504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collomb, D.; Bending, S.J.; Koshelev, A.E.; Smylie, M.P.; Farrar, L.; Bao, J.K.; Chung, D.Y.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Kwok, W.K.; Welp, U. Observing the Suppression of Superconductivity in RbEuFe4As4 by Correlated Magnetic Fluctuations. Physical Review Letters 2021, 126, 157001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, I.; Ionescu, A.M.; Crisan, D.N.; Crisan, A. Vortex Glass—Vortex Liquid Transition in BaFe2(As1-xPx)2 and CaKFe4As4 Superconductors from Multi-Harmonic AC Magnetic Susceptibility Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).