Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

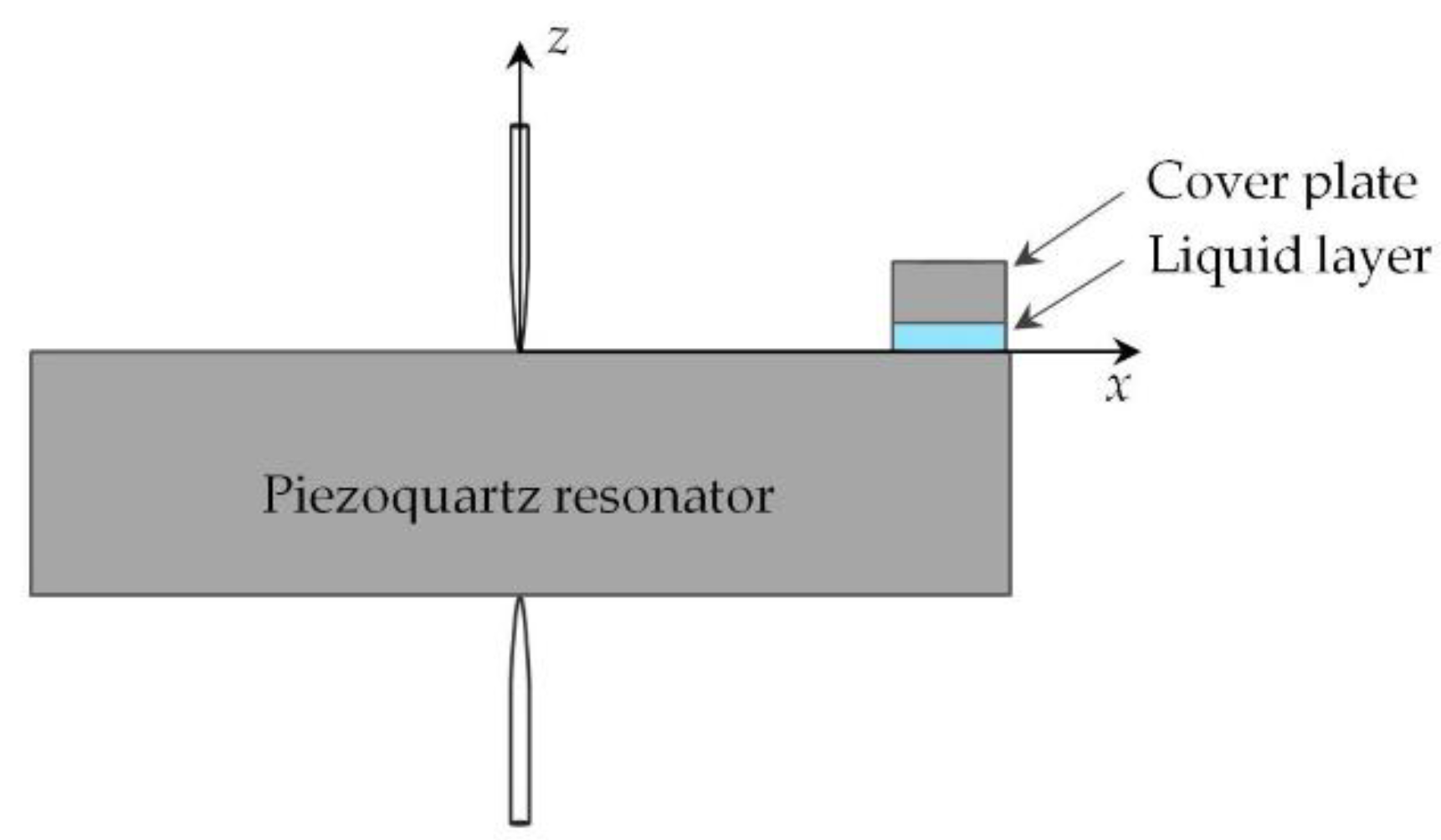

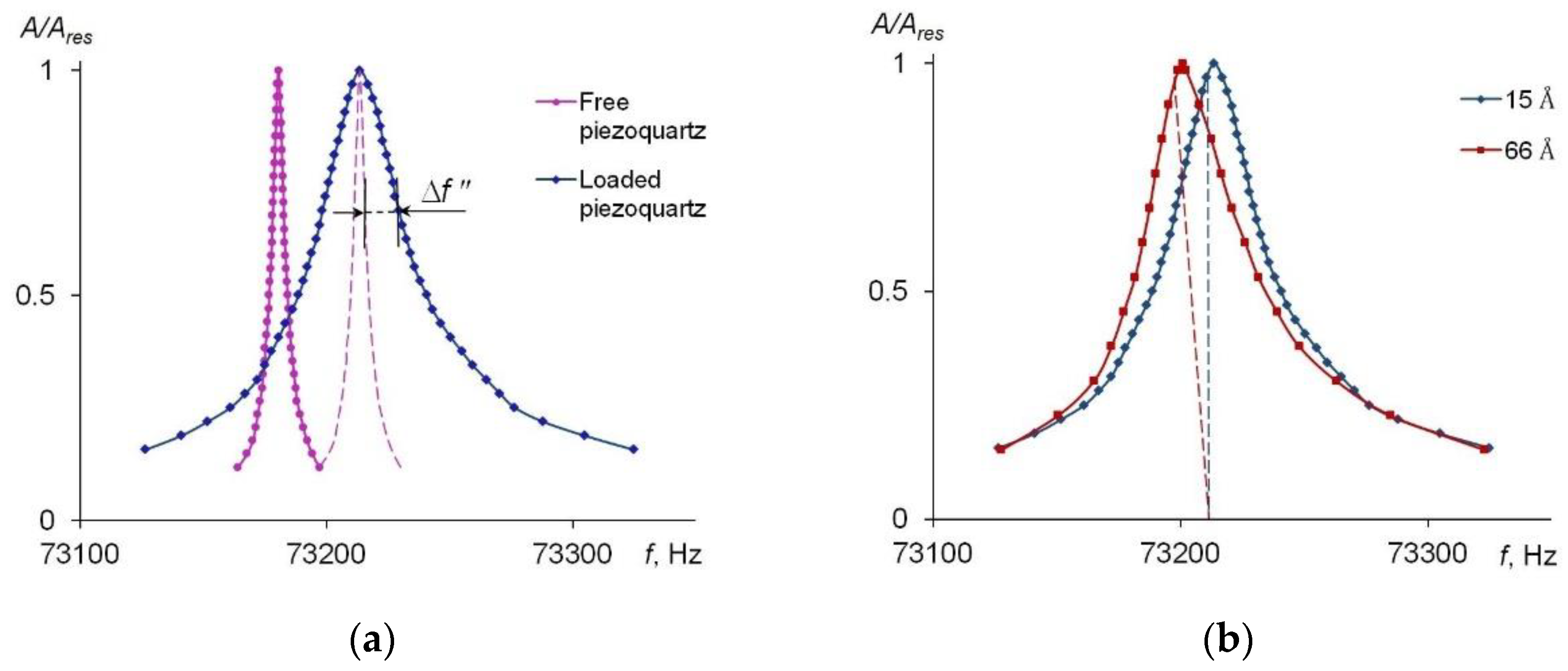

2. Materials and Methods

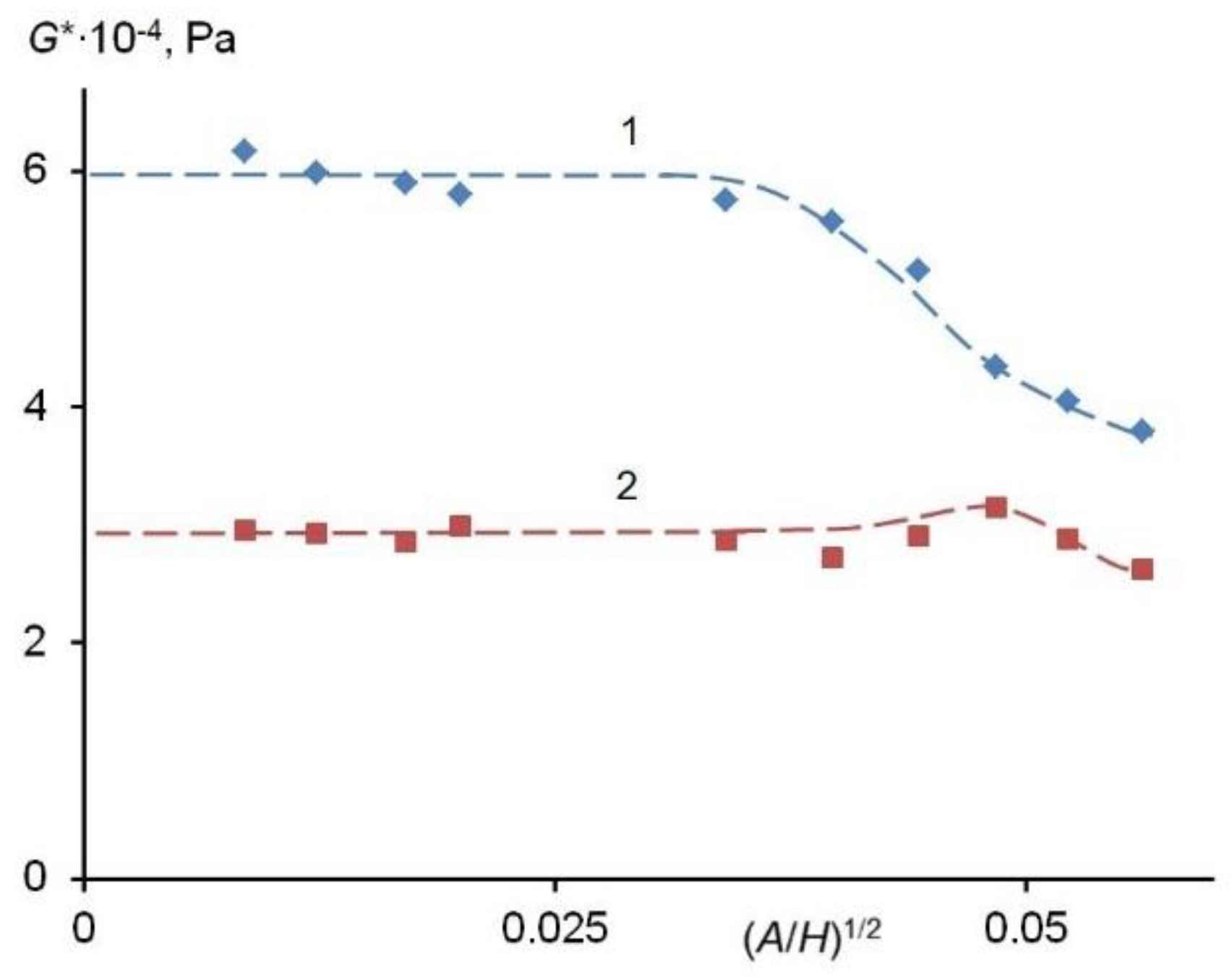

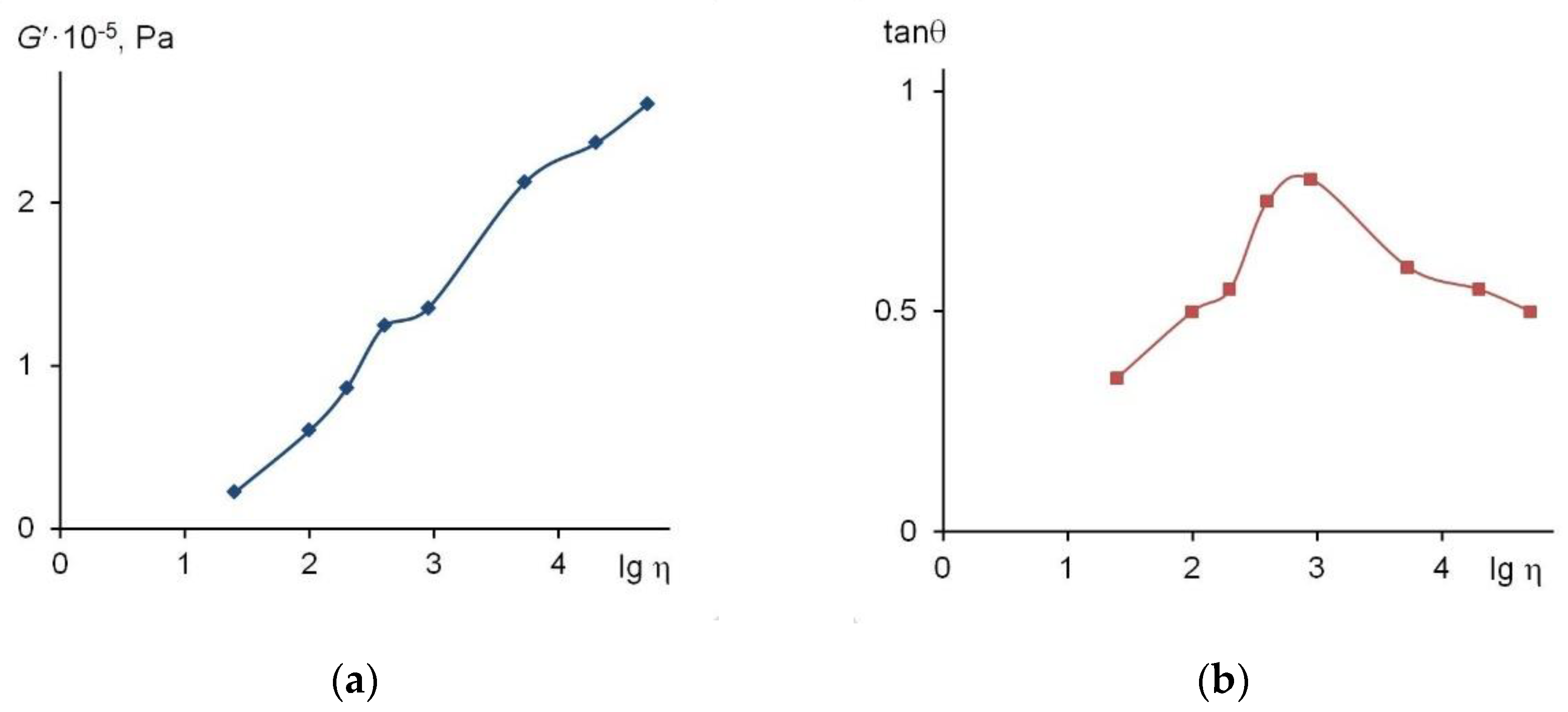

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volarovich, M.P.; Derjaguin, B.V.; Leontieva, A.A. Measurement of the shear modulus of vitreous systems in the softening interval. Acta Phys. Chem. 1936, 8, 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld, M. Elastic and strength properties of liquids. JETF 1943, 13, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, W.P. Measurement of the viscosity and shear elasticity of Liquids by means of a torsionally vibrating crystal. Trans. ASME 1947, 69, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSkimin, H.J.; Andreatch, Р. Measurement of Dynamic shear Impedance of low viscosity Liquids at Ultrasonic Frequencies. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1967, 42, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, A.J.; Lamb, J; Matheson, A.J. Viscous behaviour of supercooled liquids. Proc.Roy.Soc 1967, A298, 467¬480. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, J. Mechanical retardation and relaxation in liquids. Rheol.Acta 1971, 12, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, G.; Pechhold, W.; Willenbacher, N.; et al. Characterizing complex fluids with high frequency rheology using torsional resonators at multiple frequencies. J. Rheol. 2003, 47, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizaki, H. Measurement of viscoelastic properties of polymer solution by tortional crystals. Polymer Journal 1993, 25, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaron, U.B.; Derjaguin, B.V.; Bulgadaev, A.V. On shear elasticity of boundary layers of liquids. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1965, 160(4), 799–803. [Google Scholar]

- Bazaron, U.B.; Derjaguin, B.V.; Bulgadaev, A.V. Measurement of the shear elasticity of fluids and their boundary layers by a resonance method. JETF 1966, 24, 645–653. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, D.D.; Riccius, O.; Arney, M. Shear waves speeds and elastic moduli for different liquids, Part II. Theory. J. Fluid Mech. 1986, 171, 309–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, D.; Martinoty, P. Dynamic macroscopic heterogeneities in a flexible linear polymer melt. Physica A 2003, 320, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, T.; Wada, Y. Acoustic relaxations in toluene and alcohols in the frequency range of 10 to 300 kHz measured by the resonance reverberation method. Japanese J. Applied Physics 1969, 8, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirez, L.; Baroni, Р. Identification of a low-frequency elastic behaviour in liquid water. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2012, 24, 372101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirez, L.; Baroni, P. Identification of thermal shear bands in a low molecular weight polymer melt under oscillatory strain field. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, A.; Trachenko, K. Explaining the low-frequency shear elasticity of confined liquids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 19653–19655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, E.; Zaccone, A.; Noirez, L. Unexpected thermo-elastic effects in liquid glycerol by mechanical deformation. Physics of fluids 2021, 33, 072007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayanattil, M.; Huang, Zh.; Gitaric, D.; Epp, S.W. Rubber-like elasticity in laser-driven free surface flow of a Newtonian fluid. PNAS 2023, 120, e2301956120. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3426-1770. [CrossRef]

- Sobolevsky, M.V.; Muzovskaya, O.A.; Popeleva, G.S. Properties and Applications of Organosilicone Products; Khimiya: Moscow, Russia, 1975; pp. 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, I; Castro, I; Carvalho, V; et al. Polydimethylsiloxane mechanical properties: A systematic review. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2021, 8, 952–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolper, T.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Jungk, M.; Marks, T.; Chung, Y.-W.; Wang, Q. Lubrication Properties of Polyalphaolefin and Polysiloxane Lubricants: Molecular Structure–Tribology Relationships. Tribol. Lett. 2012, 48, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiheng, W.; Dehua, T.; Xuejin, S.; Xiaoyang, C. Study on a new type of lubricating oil for miniature bearing operating at ultra-low temperature. China Pet. Process. Petrochem. Technol. 2018, 20, 93–100. Available online: http://www.chinarefining.com/EN/Y2018/V20/I1/93 (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Niu, R.; Gong, J.; Xu, D.; Tang, T.; Sun, Z.-Y. Rheological properties of ginger-like amorphous carbon filled silicon oil suspensions. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem.Eng.Aspects. 2014, 444, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichester, C.W. Development of High Service Temperature Fluids. SAE Technical Paper 2016, 2016-01-0484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. Grafting of thermotropic fluorinated mesogens on polysiloxane to improve the processability of linear low-density polyethylene. RSC Advances 2022, 12, 12463–12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Cao, B.; Cai, J.; Ye, Zh.; Lu, X.; Huang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J. Design and synthesis of Polysiloxane based side chain liquid crystal polymer for improving the processability and toughness of Magnesium hydrate/linear low-density Polyethylene composites. Polymers 2020, 12, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembelova, T.; Badmaev, B.; Makarova, D.; Mashanov, A.; Mishigdorzhiyn, U. Rheological and tribological study of polyethylsiloxane with SiO2 nanoparticles additive. Lubricants 2023, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimytov, T.A.; Nomoev, A.V.; Kalashnikov, S.V.; et al. Observation of memory effects in 5CB/PVAc liquid crystal-polymer composites. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2025, 12, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STAR. Available online: https://star-pro.ru/gost/13032-77 (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Badmaev, B.B.; Dembelova, T.S.; Damdinov, B.B. Viscoelastic properties of polymer liquids; Publisher of the Buryat Scientific Center, SB RAS: Ulan-Ude, Russia, 2013; 190 p. [Google Scholar]

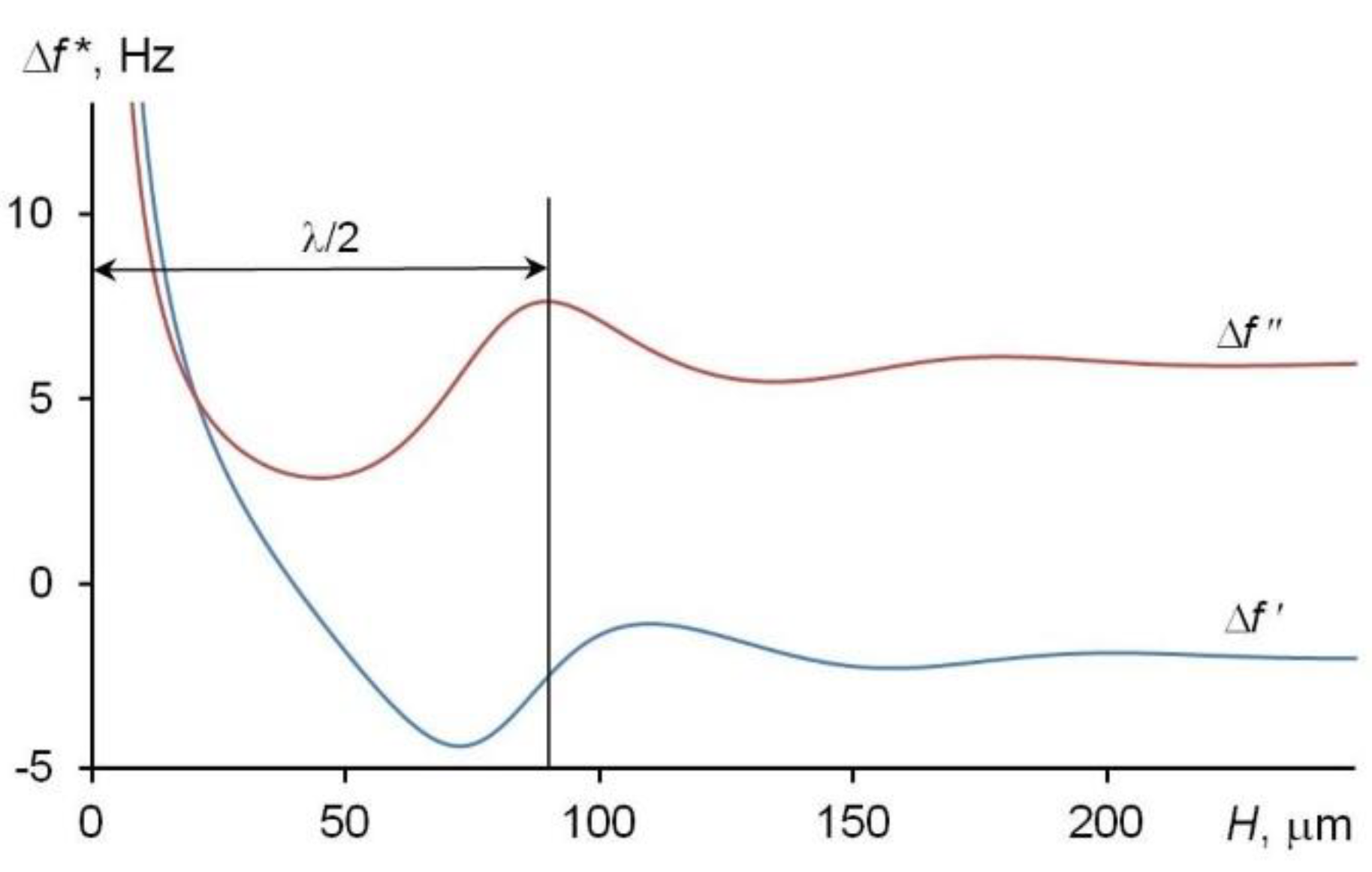

- Badmaev, B.B.; Dembelova, T.S.; Makarova, D.N.; Gulgenov, C.Z. Ultrasonic Interferometer on Shear Waves in Liquids. Russian Physics Journal 2020, 62, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmaev, B.; Dembelova, T.; Damdinov, B.; Makarova, D.; Budaev, O. Influence of surface wettability on the accuracy of measurement of fluid shear modulus. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2011, 383, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

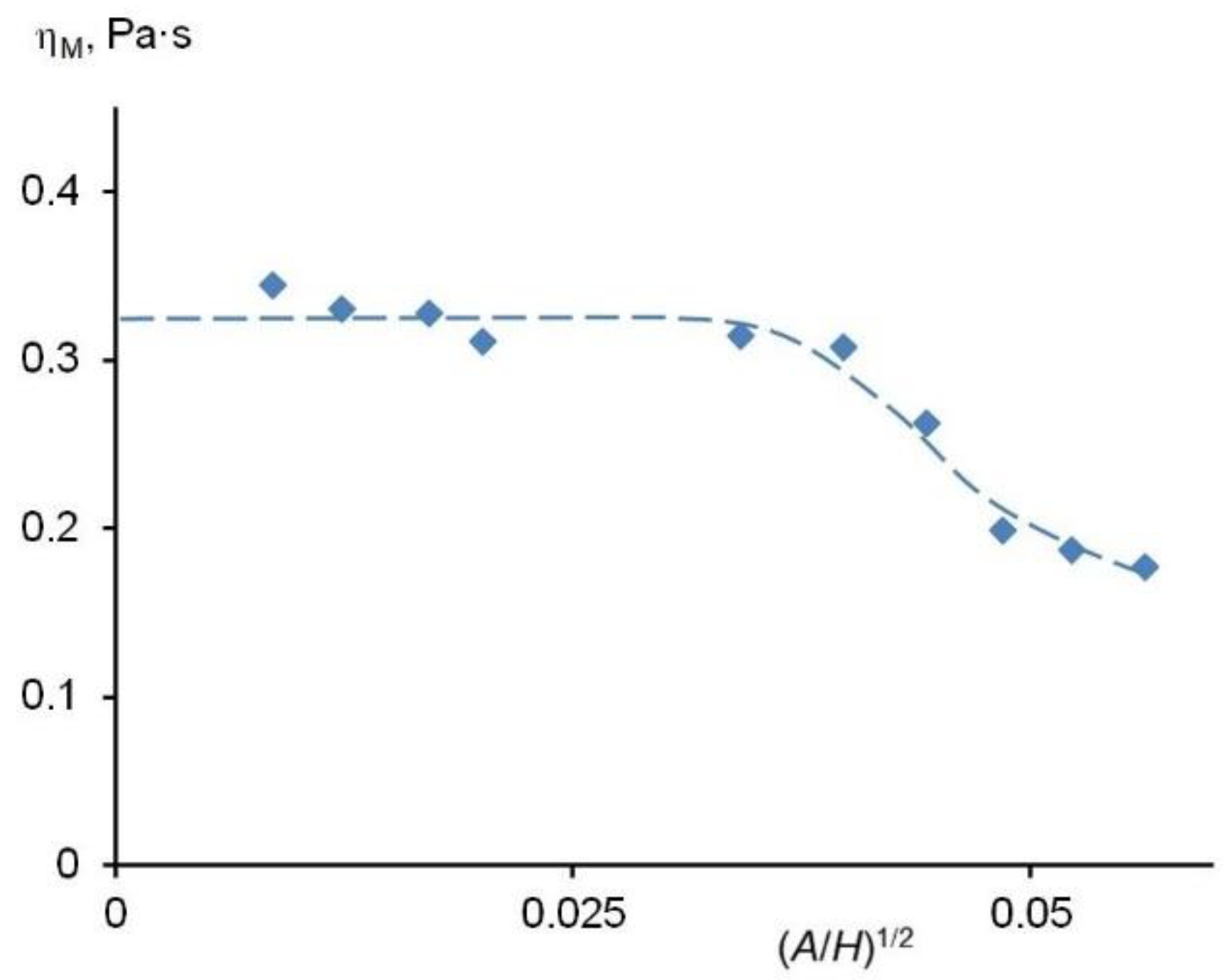

- Dembelova, T.S.; Badmaev, B.B.; Makarova, D.N.; Vershinina, Ye.D. Nonlinear viscoelastic properties of nanosuspensions. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 704, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaron, U.B.; Derjaguin, B.V.; Zandanova, K.T.; Lamazhapova, Kh.D. Nonlinear properties of shear elasticity of liquids. Zhurnal fizicheskoi khimii 1981, 55, 2812–2816. [Google Scholar]

- Badmaev, B.B.; Dembelova, T.S.; Makarova, D.N.; Gulgenov, C.Z. Shear elasticity and strength of the liquid structure by an example of diethylene glycol. Technical Physics 2017, 62, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Bazaron, U.B.; Zandanova, K.T.; Budaev, O.R. The complex shear modulus of polymeric and small-molecule liquids. Polymer 1989, 30, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmaev, B.B.; Bazaron, U.B.; Derjaguin, B.V.; Budaev, O.R. Measurement of the shear elasticity of polymethylsiloxane liquids. Physica B+C 1983, 122, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derjaguin, B.V.; Badmaev, B.B.; Bazaron, U.B.; Lamazhapova, Kh.D.; Budaev, O.R. Measurement of the low-frequency shear modulus of polymeric liquids. Phys. Chem. Liq. 1995, 29, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmaev, B.B.; Budaev, O.R.; Dembelova, T.S.; Damdinov, B.B. Shear elasticity of fluids at low frequent shear influence. Ultrasonics 2006, 44, e1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartenev, G.M.; Sanditov, D.S. Relaxation processes in glassy systems; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1986; pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bartenev, G.M.; Barteneva, A.G. Relaxation properties of polymers; Khimiya: Moscow, Russia, 1992; pp. 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Badmaev, B.B.; Damdinov, B.B.; Dembelova, T.S. Viscoelastic relaxation in fluids. Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Physics 2015, 79, 1301–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembelova, T.S.; Sanditov, D.S. Low-frequency viscoelastic relaxation in polymer liquids. Bulletin of Buryat State University. Chemistry. Physics (In Russ.). 2022, 1, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakovich, M.A.; Chaban, I.A. Propagation of sound in strongly viscous liquids. JETP 1966, 23, 893–905. Available online: http://www.jetp.ras.ru/cgi-bin/dn/e_023_05_0893.pdf.

- Sanditov, D.S. Thermally induced low-temperature relaxation of plastic deformation in glassy organic polymers and silicate glasses. Polymer Science Series A 2007, 49, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanditov, D.S.; Ojovan, M.I. On relaxation nature of glass transition in amorphous materials. Physica B 2017, 523, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schawe, J.E.K.; Hallavant, K.; Esposito, A.; Löffler, J.F.; Saiter-Fourcin, A. The Universality of Cooperative Fluctuations in Glass-Forming Supercooled Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 12255−12265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Louzguine-Luzgin, D.V. Role of Structural Changes at Vitrification and Glass–Liquid Transition. Materials 2025, 18, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Tournier, R.F. On structural rearrangements near the glass transition temperature in amorphous silica. Materials 2021, 14, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippoff, W. Relaxation in polymer solutions, polymer liquids and gels. In Physical acoustics. Properties of polymers and nonlinear acoustics; Mason, W.P., Ed.; Mir: Moscow, USSR, 1969; Volume II, Part B, pp. 9–109. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, J.; Laloy-Borgna, G.; Rus, G.; Catheline, S. A phase transition approach to elucidate the propagation of shear waves in viscoelastic materials. Appl Phys Lett 2023, 122, 223702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fluid | t,°C |

·10-3, kg/m3 ·10-3, kg/m3

|

G′·10-5, Pa |

tan

|

fM·10-3, Hz |

M, Pa·s M, Pa·s

|

| PMS-25 | 24 | 0.94 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 25.90 | 0.15 |

| PMS-100 | 23 | 0.97 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 37.00 | 0.32 |

| PMS-200 | 22 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 40.70 | 0.44 |

| PMS-400 | 23 | 0.98 | 1.24 | 0.75 | 55.50 | 0.55 |

| PMS-900 | 22 | 0.98 | 1.35 | 0.80 | 59.20 | 0.59 |

| PMS-5384 | 22 | 0.98 | 2.12 | 0.60 | 44.40 | 1.03 |

| PMS-20000 | 23 | 0.98 | 2.36 | 0.55 | 40.70 | 1.20 |

| PMS-52000 | 24 | 0.98 | 2.60 | 0.50 | 37.00 | 1.39 |

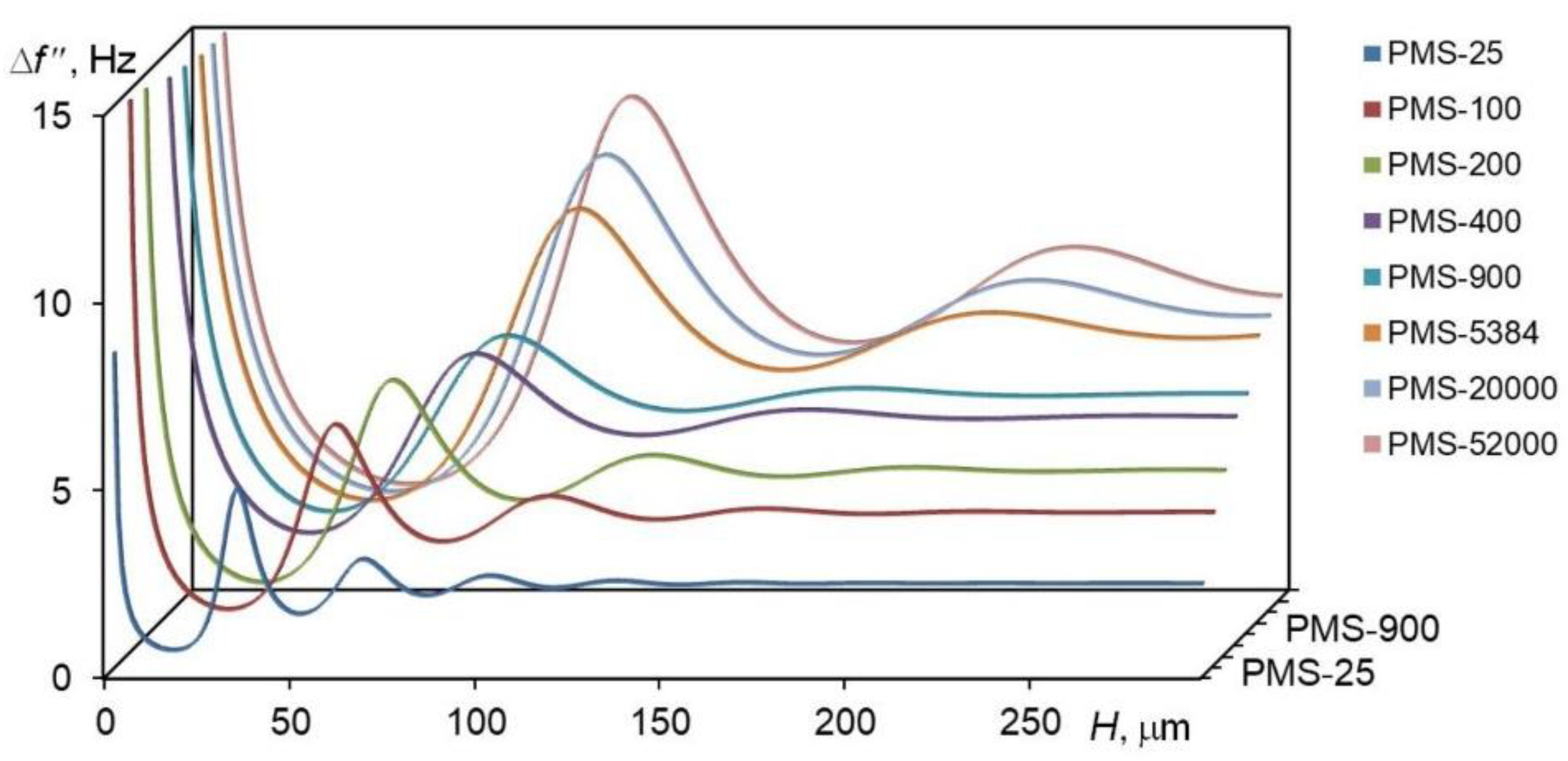

| Liquid | λ, μm | α, cm-1 |

| PMS-25 | 68 | 156,9 |

| PMS-100 | 116 | 127,8 |

| PMS-200 | 140 | 115,2 |

| PMS-400 | 180 | 116,3 |

| PMS-900 | 190 | 115,9 |

| PMS-5384 | 222 | 78,4 |

| PMS-20000 | 232 | 69,5 |

| PMS-52000 | 240 | 61,8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).