1. Introduction

Wildfires constitute a major ecological disturbance that influences vegetation dynamics, carbon cycling, soil stability, and hydrological processes at landscape to global scales. In recent decades, fire activity has intensified worldwide, with increasing burned area, fire severity, and season length attributed to climate warming, drought exacerbation, and land-use change (Abatzoglou et al., 2019; Jolly et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2022). These shifts not only degrade biodiversity and ecosystem services but also release substantial greenhouse gases and aerosols, contributing ~8.1 Pg CO₂-equivalent annually—approximately 23 % of global fossil-fuel CO₂ emissions in 2014, and higher in peak fire years (van der Werf et al., 2017). The eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern regions, including the Zagros Mountains oak belt, have emerged as particular hotspots of escalating fire risk under progressive aridification and rising temperatures (Jaafari et al., 2018; Turco et al., 2017).

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), located in the northern mountainous zone, contains the country's most extensive remaining oak-dominated forests, dominated by Quercus brantii, Q. infectoria, and Q. libani, covering approximately 2,000 km² across Duhok, Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, and Halabja governorates (Khwarahm, 2020). These semi-arid woodlands represent a regionally significant biodiversity hotspot, an important carbon sink, and a cultural landscape, providing critical watershed protection, non-timber forest products (e.g., galls, fuelwood, and fodder), and habitat for endangered flora and fauna, including the Persian leopard (Panthera pardus tulliana) and numerous endemic plant species (EPIC, 2022). Despite their ecological importance, KRI forests are increasingly threatened by recurrent large wildfires driven by prolonged drought, extreme heat events, agricultural escape fires, and post-conflict fuel accumulation from abandoned orchards and reduced grazing pressure (Eklund et al., 2021; Eklund & Dinc, 2024).

The oak forests of the Zagros Mountains in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) are among the last relatively intact examples of the once-vast western Iranian–Anatolian oak steppe-forest biome, which has lost over 50% of its historical extent over the past century due to overgrazing, fuelwood harvesting, and agricultural conversion (Beygi Heidarlou et al., 2020; Talebi et al., 2013). In a region marked by decades of conflict and political marginalization, systematic forest management and fire suppression capacity remain severely limited (Eklund & Dinc, 2024). By the end of the century, the region is projected to warm by 2–6 °C and experience a 20–40 % decline in cool-season precipitation in the northern areas under high-emission scenarios (Zittis et al., 2022). This combination of heightened climatic fire weather, abundant fine-fuel loads from abandoned lands, and institutional constraints creates conditions for potentially transformative crown-fire events that could push these slow-growing, drought-adapted oak ecosystems past ecological tipping points, with cascading effects on downstream water security for millions of inhabitants in Iraq and beyond (Jaafari et al., 2018).

Although national-scale studies have documented a significant upward trend in total burned area across Iraq over the past two decades (Rasul et al., 2020), forest-specific analyses remain limited. Existing work has primarily addressed agricultural and grassland fires or broad national aggregates, while the distinct fire regime of oak-dominated ecosystems — characterised by greater resilience under moderate conditions yet acute vulnerability during compound heat–drought extremes — has received little attention. Moreover, spatial heterogeneity among governorates and the primary climatic drivers of forest fire extent in this understudied region remain poorly quantified, hindering the design of targeted prevention and suppression strategies.

This study addresses these gaps by providing the first comprehensive, long-term (2001–2024) assessment of wildfire trends and climatic drivers explicitly focused on the forested ecosystems of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq using the MODIS MCD64A1 Version 6.1 burned-area product. The specific objectives were:

To quantify the interannual variability and long-term trend of wildfire burned area in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (2001–2024), with particular focus on forested ecosystems, using MODIS MCD64A1 data Version 6.1.

To examine spatial differences in forest fire regimes among the four governorates and evaluate regional-scale increasing trends in fire activity.

To determine the primary climatic drivers of wildfire extent in Kurdistan Region forests through non-parametric correlation, multicollinearity diagnostics, and zero-inflated negative binomial modelling of monthly burned area in relation to maximum temperature, precipitation, and Palmer Drought Severity Index.

By establishing a robust quantitative baseline and identifying actionable climatic thresholds (~32 °C maximum temperature and PDSI < –2), this research provides critical evidence to guide governorate-tailored fire management, inform early-warning systems, and support the conservation of one of the Middle East’s last extensive oak woodland ecosystems in the face of accelerating climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

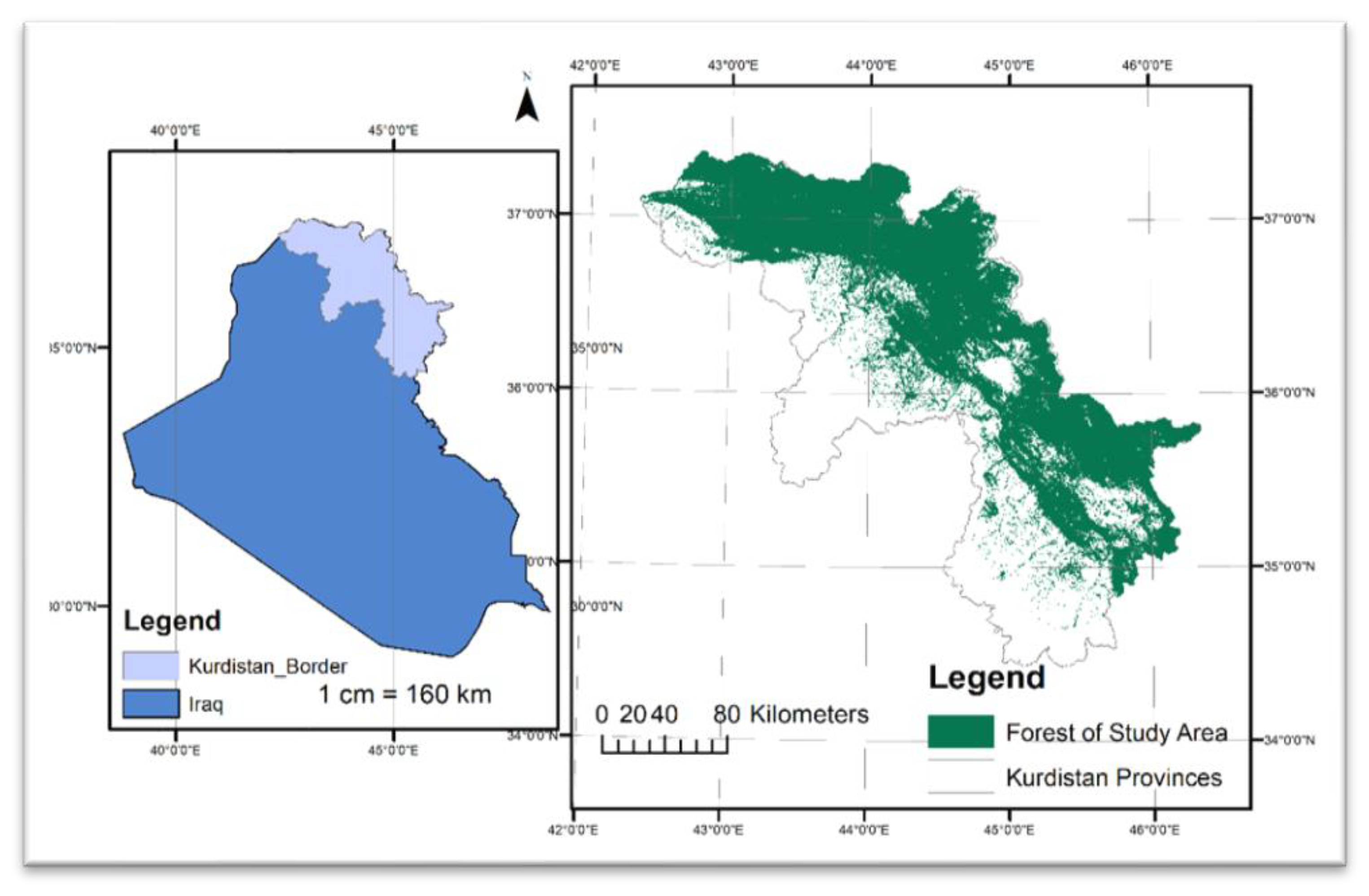

The study was conducted in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), located in northern and northeastern Iraq (central coordinates approximately 37°00′ N, 44°00′ E), with a specific focus on its forested ecosystems (

Figure 1). The KRI comprises the governorates of Erbil, Sulaymaniyah, Duhok, and Halabja, together with the districts of Akre and Shekhan (Duhok Governorate), covering a total area of approximately 51,521 km². The KRI occupies the mountainous northern and northeastern part of Iraq, belonging to the High Folded Zone of the Zagros orogenic belt (Sissakian et al., 2015). This region is characterised by strongly folded anticlinal ridges and synclinal valleys, with elevations ranging from ~800 m a.s.l. in the southwest to 3,544 m a.s.l. at Mount Halgurd in the northeast. The climate is continental Mediterranean with cold, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Mean annual precipitation (2012–2024) is 548.7 mm; over 90% falls between November and April. Mean annual temperature is ~20.8 °C in Erbil and ~17 °C in higher areas; summer maxima regularly exceed 44 °C, while winter minima occasionally drop below –2 °C (Ministry of Planning, KRG, 2025).

To delineate the forest mask used throughout the analysis, a high-resolution NDVI-based land-cover map for 2024 was reclassified into a strict binary forest/non-forest layer (value 2 = forest). This binary raster was then conservatively downsampled by a factor of 10 using maximum pooling to ensure that any resampled pixel containing at least one original forest pixel was retained as forest, thereby producing an inclusive yet accurate forest mask of approximately 2,000 km² of woodland and shrubland. The downsampled binary mask was subsequently polygonized, dissolved into a single multipart feature, and saved as a vector shapefile. All subsequent burned-area extractions for “forest” were performed by zonal statistics using this forest mask.

2.2. Burned Area Data Acquisition and Processing

Annual burned area data for the period 2001–2024 were derived from the MODIS MCD64A1 Version 6.1 Burned Area product (500 m spatial resolution) (Giglio et al., 2018) accessed via Google Earth Engine (GEE) (Gorelick et al., 2017). The MCD64A1 ‘BurnDate’ band was selected, and for each year, an annual composite was created by taking the maximum value within the calendar year (any pixel with a valid burn date in that year was retained). Pixels with BurnDate > 0 were converted to binary burned (1) / unburned (0) masks and clipped to the Kurdistan Region boundary. Twenty-four annual binary GeoTIFFs (one per year) were exported to Google Drive at 500 m resolution in WGS84 (EPSG:4326) using cloud-optimized GeoTIFF format.

After download, the total annual burned area for the entire Kurdistan Region was calculated directly from these rasters by counting burned pixels and multiplying by pixel area (0.25 km²). Forest-specific burned area was extracted locally in Python using rasterio’s mask function: each annual burned-area raster was masked to the forest polygon (crop=True, nodata=0), and burned pixels within the resulting forest extent were summed and converted to km². The same procedure was repeated after intersecting the forest mask with official governorate boundaries to obtain governorate-level forest burned area (Duhok, Erbil, Halabja, Sulaymaniyah).

2.3. Trend Analysis

Long-term trends in annual burned area were quantified separately for (i) the entire Kurdistan Region, (ii) forests across the region, and (iii) forests within each of the four governorates (Duhok, Erbil, Halabja, Sulaymaniyah) over the 2001–2024 period.

The non-parametric Theil–Sen single-median slope estimator (implemented via scipy.stats.theilslopes; Equation 1) was used to estimate the magnitude and 95 % confidence interval of the monotonic trend (km² year⁻¹). This approach is particularly robust to outliers and non-normal distributions that are characteristic of wildfire time series. Monotonic trend significance and direction were evaluated using the Mann–Kendall trend test (implemented via scipy.stats.kendalltau; Equation 2), with statistical significance declared at α = 0.05.

where b is the estimation of the slope of the trend and

is the

th observation.

where

and

denote the data points at times

and

, respectively, and

is the Mann–Kendall test statistic.

For the regional and whole-forest analyses, annual burned-area values were read from the CSV file generated. Governorate-level trends were calculated after pivoting the per-governorate CSV so that each governorate formed a separate time series. All calculations included diagnostic checks for column-name variations and enforced numeric conversion with zero-filling of any missing values. Trend lines and significance annotations were visualised for the regional forest series and as a 2×2 subplot panel for the four governorates.

2.4. Climatic and Drought Data

Monthly climatic and drought data for the period January 2001–December 2024 (n = 288 months) were extracted using Google Earth Engine (GEE) and local Python post-processing, and subsequently averaged over the forested areas of the Kurdistan Region.

Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) was obtained from the TerraClimate dataset (IDAHO_EPSCOR/TERRACLIMATE) at ~4 km resolution (Abatzoglou et al., 2018). The ‘pdsi’ band was scaled by 0.01, and monthly regional means were calculated over the Kurdistan Region boundary.

Maximum temperature (°C) and total precipitation (mm month⁻¹) were derived from the ERA5-Land monthly aggregated collection (ECMWF/ERA5_LAND/MONTHLY_AGGR) at 0.1° resolution (Muñoz-Sabater et al., 2021). The bands ‘temperature_2m_max’ (converted from Kelvin to °C) and ‘total_precipitation_sum’ (converted from metres to millimetres) were used directly as monthly aggregates.

Wind speed (m s⁻¹) was initially extracted from the same TerraClimate dataset using the ‘vs’ band (10 m wind speed, stored as integer after multiplication by 100). Monthly means were computed over the region, scaled by dividing by 100, and exported via a year-month loop to avoid GEE nested-list errors.

All four variables were initially exported from GEE as wide-format tables (one row per feature, one column per month) using ee.batch.Export.table.toDrive and subsequently reshaped locally into long-format CSVs (columns: Date, PDSI, MaxTemp, Precipitation, WindSpeed). Final forest-specific monthly time series were produced by weighted zonal averaging using the downsampled binary forest mask as weights, ensuring values represent conditions in forests rather than the regional average. Wind speed was eventually excluded from the final driver analysis due to severe multicollinearity with maximum temperature (VIF = 43.87).

2.5. Statistical Analyses of Climatic Drivers

Prior to correlation and regression analyses, descriptive summary statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, median, and maximum) were calculated for monthly forest burned area and the four initially extracted climatic predictors (PDSI, maximum temperature, total precipitation, and wind speed) using the pandas.DataFrame.describe() method on the complete dataset (n = 288 months) after removal of any rows with missing values in the variables of interest. These statistics provided an overview of central tendency, variability, and distributional characteristics (e.g., skewness, zero-inflation in burned area, and the highly skewed nature of precipitation), confirming the need for non-parametric approaches and zero-inflated modelling in subsequent analyses.

2.5.1. Correlation Analysis

Prior to regression modelling, monotonic associations between monthly forest burned area and the climatic predictors (PDSI, maximum temperature, total precipitation, and wind speed) were examined using Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient (ρ), which is non-parametric and therefore robust to non-normal distributions, outliers, and the large proportion of zero-burned-area months prevalent in the dataset (n = 288 months).

Spearman correlations and associated p-values were computed for all pairwise combinations with the function scipy.stats.spearmanr using the option nan_policy='omit' to handle any remaining missing values. The resulting full correlation matrix was visualised as an annotated heatmap using the Seaborn library with a diverging ‘coolwarm’ colour map (vmin = –1, vmax = 1) to highlight the strength and direction of relationships. This analysis served both as an exploratory step and as justification for subsequent multicollinearity diagnostics, confirming the expected strong positive association of burned area with maximum temperature, strong negative association with precipitation, weaker association with PDSI, and moderate association with wind speed.

2.5.2. Multicollinearity Diagnostics

To detect potential multicollinearity among the four initially extracted climatic predictors (PDSI, maximum temperature, total precipitation, and wind speed), variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated using the statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence.variance_inflation_factor function.

A design matrix X was constructed from the complete monthly time series (n = 288) containing only these four variables (any rows with missing values were omitted). VIF values were computed iteratively for each predictor, with VIF > 5 interpreted as moderate multicollinearity and VIF > 10 indicating severe multicollinearity requiring remedial action (Hair et al., 2019).

Results showed severe multicollinearity for wind speed (VIF = 43.87) and substantial inflation for maximum temperature (VIF = 28.72), both driven by strong seasonal co-variation. Wind speed was therefore removed from subsequent modelling. After exclusion, all remaining predictors (PDSI, maximum temperature, precipitation) exhibited acceptable VIF values below 3, confirming that multicollinearity was no longer a concern for reliable coefficient estimation in the final models.

2.5.3. Bivariate Relationships with Climatic Drivers

To explore individual relationships between monthly forest burned area and each climatic predictor while enhancing visibility of trends in fire-prone months, simple ordinary least-squares (OLS) linear regressions were performed separately for PDSI, maximum temperature, and precipitation on the subset of months with non-zero burned area (n = 216 after excluding ~25 % zero-fire months). Precipitation was log(x + 1)-transformed prior to analysis to address strong positive skew. For each predictor, a scatter plot with an overlaid linear fit was produced using scipy.stats.linregress, and goodness-of-fit was reported as adjusted R². Residual patterns (heteroscedasticity and threshold-like acceleration at extreme values) were noted to motivate the more sophisticated zero-inflated modelling described below.

2.5.4. Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) Regression

Given the count-based nature of monthly burned area (km² converted to integer counts of 0.25 km² pixels), the high proportion of structural zeros (~25 % of months with no fire), and clear overdispersion in non-zero months, a Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial (ZINB) regression was selected as the primary modelling framework (implemented via statsmodels.discrete.count_model.ZeroInflatedNegativeBinomialP in Python).

The response variable was monthly forest burned area (rounded to nearest integer pixel count). The final count-model predictors (explanatory variables for fire magnitude when fires occur) were PDSI, maximum temperature (°C), and log(total precipitation + 1). A constant term was added using sm.add_constant. The inflation (zero-generating) component was kept minimal, using only PDSI as an inflate predictor to stabilise convergence. The model was fitted using the Nelder-Mead optimisation algorithm (method='nm') with a maximum of 100 iterations.

Coefficients from the count portion were exponentiated to obtain incidence-rate ratios (IRR) and 95 % confidence intervals. Model fit was evaluated with McFadden’s pseudo-R² calculated as 1 – (log-likelihood_model / log-likelihood_null). Marginal effects of each predictor on predicted burned area (holding other variables at their means) were computed across observed ranges and plotted with 95 % confidence bands using custom prediction functions applied to the fitted ZINB object. These plots clearly illustrated non-linear escalation of fire extent under severe drought and extreme heat (MaxTemp > ~32 °C).

3. Results

3.1. Annual burned area in Kurdistan Region from 2001 to 2024

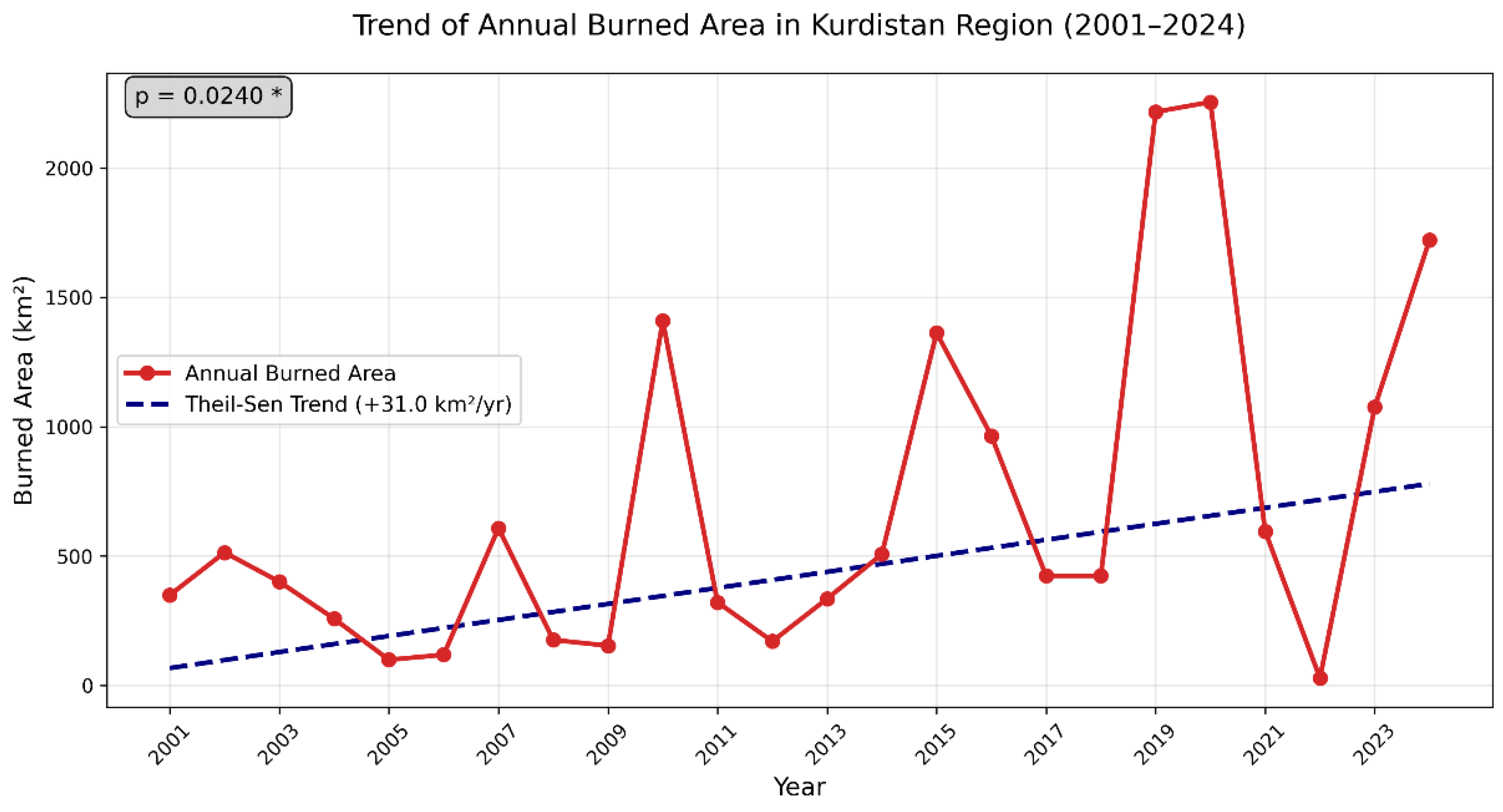

The MODIS MCD64A1 v6.1 burned area product revealed pronounced interannual variability in wildfire extent across the Kurdistan Region (KR) from 2001 to 2024, with a mean annual burned area of 687 km² (SD = 640 km²) and a cumulative total of 16,486 km² over the 24-year period (

Table 1). This represents an average annual burn rate of approximately 1.7% of KR’s land area (~40,914 km²), reflecting persistent fire activity in a semi-arid to sub-humid environment increasingly influenced by climate variability and human factors.

Annual burned area ranged from a minimum of 28.3 km² in 2022 to a maximum of 2,255.0 km² in 2020, followed by 2019 (2,216.9 km²) and 2024 (1,721.4 km²). These three years alone accounted for 36% of the total burned area recorded over the entire period, highlighting the highly episodic nature of major fire events in the region.

Non-parametric trend analysis using the Theil–Sen estimator indicated a statistically significant increasing trend of +31 km²/year (Mann–Kendall τ = 0.29, p = 0.024), confirming a gradual but robust intensification of fire activity over the 24-year record (

Figure 2). A clear shift in fire regime is apparent: the average annual burned area during 2001–2010 was 433 km²/year, compared to 941 km²/year during 2011–2024 — representing a 117% increase in the latter period. This marked acceleration coincides with prolonged drought conditions (notably 2018–2020 and 2023–2024), land-use changes, and periods of reduced fire management capacity linked to regional instability.

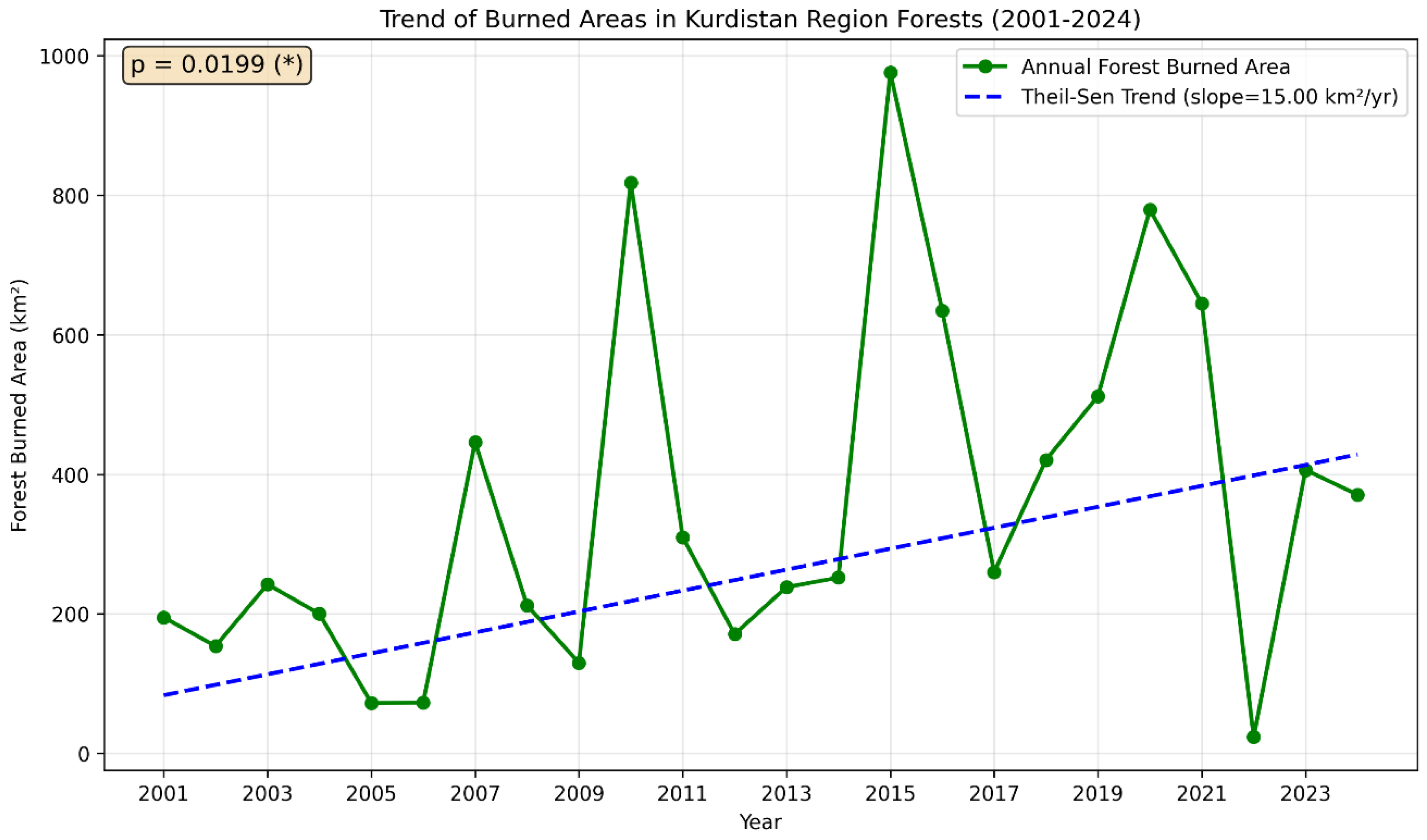

3.2. Annual burned Area in Forests of Kurdistan Region (2001 to 2024)

Forest burned area in Kurdistan Region (KR) was markedly lower than total regional fires, averaging 356 km² year⁻¹ (SD ≈ 280 km²) and totaling 8,542 km² over the 24-year period—representing approximately half (51.8%) of the overall KR burned extent (

Table 2). This equates to an annual burn rate of about 0.178% of estimated forest cover (~2,000 km² of oak-dominated ecosystems), highlighting the relative resilience of forests compared to non-forested lands like grasslands and croplands, yet underscoring their disproportionate vulnerability to severe events. The dataset exhibited pronounced interannual fluctuations, with near-negligible occurrences in 2022 (23.5 km²) contrasting sharp peaks in 2010 (818 km²) and 2015 (976 km²), the latter exceeding 48% of total annual forest.

Trend analysis via the Theil-Sen estimator detected a statistically significant positive trajectory, with a slope of +17 km² year⁻¹ (95 % CI: [6.1, 28.4]; Mann–Kendall p = 0.016), indicating a gradual escalation in forest fire activity over time (

Figure 3). This upward trend, accelerating after 2010, when average annual forest burned area rose from ~220 km² year⁻¹ (2001–2010) to ~490 km² year⁻¹ (2011–2024).

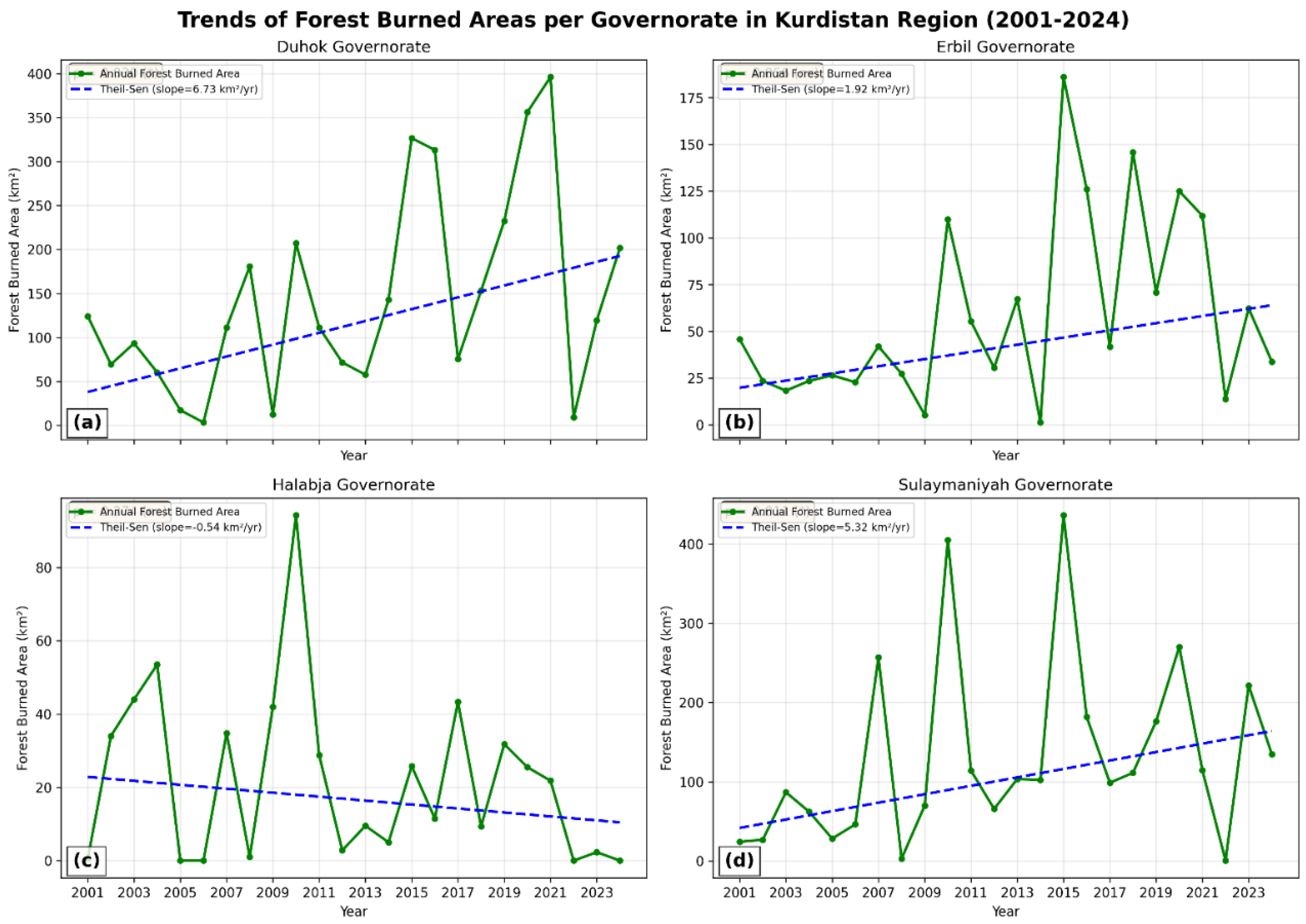

3.3. Annual Burned Area per Governorate in Forests of Kurdistan Region (2001–2024)

Spatial disaggregation of forest burned area across the four governorates of the Kurdistan Region reveals strong heterogeneity in fire incidence and trends from 2001 to 2024 (

Table 3). Duhok experienced the highest cumulative forest burned area (3,450 km², 40.4 % of regional total), followed closely by Sulaymaniyah (3,142 km², 36.8 %). Together, these two governorates accounted for 77 % of all forest burned area over the 24-year period, reflecting their extensive oak cover on steep, fire-prone slopes and proximity to agricultural interfaces. Erbil recorded 1,416 km² (16.6 %), while Halabja had the lowest at 522 km² (6.1 %). Mean annual forest burned area was highest in Duhok (144 km² year⁻¹), followed by Sulaymaniyah (131 km² year⁻¹), Erbil (59 km² year⁻¹), and Halabja (22 km² year⁻¹).

Theil–Sen trend analysis confirmed statistically significant upward trends in the two most affected governorates: Duhok (+6.73 km² year⁻¹, 95 % CI: [0.73, 12.73], Mann–Kendall p = 0.030) and Sulaymaniyah (+5.32 km² year⁻¹, 95 % CI: [1.22, 9.42], p = 0.011). Erbil showed a non-significant increase (+1.92 km² year⁻¹, p = 0.056), while Halabja exhibited no clear trend (–0.54 km² year⁻¹, p = 0.274).

Figure 4.

Trends in annual forest burned area by governorate in the Kurdistan Region, 2001–2024.

Figure 4.

Trends in annual forest burned area by governorate in the Kurdistan Region, 2001–2024.

3.4. Key drivers of wildfires in Kurdistan Region

To identify the climatic and drought-related factors driving wildfires in Kurdistan Region (KR) forests, we examined monthly data from 2001 to 2024 (n=288 observations) using MODIS-derived burned area as the response variable and three core predictors: Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), maximum air temperature (MaxTemp), and total precipitation. These variables were chosen for their direct biophysical roles in fuel flammability, ignition potential, and suppression, with PDSI integrating temperature, precipitation, and soil moisture into a standardized drought metric. Wind speed was initially considered but excluded due to severe multicollinearity (VIF = 43.87), as detailed in subsequent analyses. Summary statistics (

Table 4) characterize the dataset's underlying conditions, revealing a persistently arid regime conducive to fire risk: PDSI averaged -3.36 (SD = 2.78), indicating moderate to severe drought across 75% of months (values ≤ -1.93), with extremes reaching -10.00 during prolonged dry spells. MaxTemp exhibited substantial seasonal and interannual variability (mean = 28.31°C, SD = 10.12°C), spanning from mild winters (min = 9.99°C) to scorching summers (max = 43.17°C), reflecting the region's continental climate amplified by elevation gradients. Precipitation was highly skewed (mean = 62.24 mm/month, SD = 65.52 mm/month), with a median of 40.87 mm signaling frequent low-rain months (25% ≤ 2.17 mm) punctuated by rare deluges (max = 284.71 mm), consistent with erratic Mediterranean influences. Burned area displayed extreme right-skewness (mean = 56.32 km², SD = 103.65 km²), dominated by zeros or low values (median = 7.05 km², 25% = 0 km²) but punctuated by catastrophic peaks (max = 551.20 km² in 2019), highlighting the episodic nature of wildfires driven by ignition thresholds rather than chronic exposure. This distribution, with approximately 25% zero-burn months, necessitates zero-inflated modeling to disentangle occurrence from intensity, as explored below. Collectively, the statistics portray a fire-prone landscape where chronic drought (PDSI) intersects with temperature extremes and moisture deficits, setting the stage for the correlations and regression results that quantify these interplays. Analyses followed the workflow detailed in

Section 3.4.1,

Section 3.4.2,

Section 3.4.3 and

Section 3.4.4

3.4.1. Correlation Between Burned Area and Key Drivers

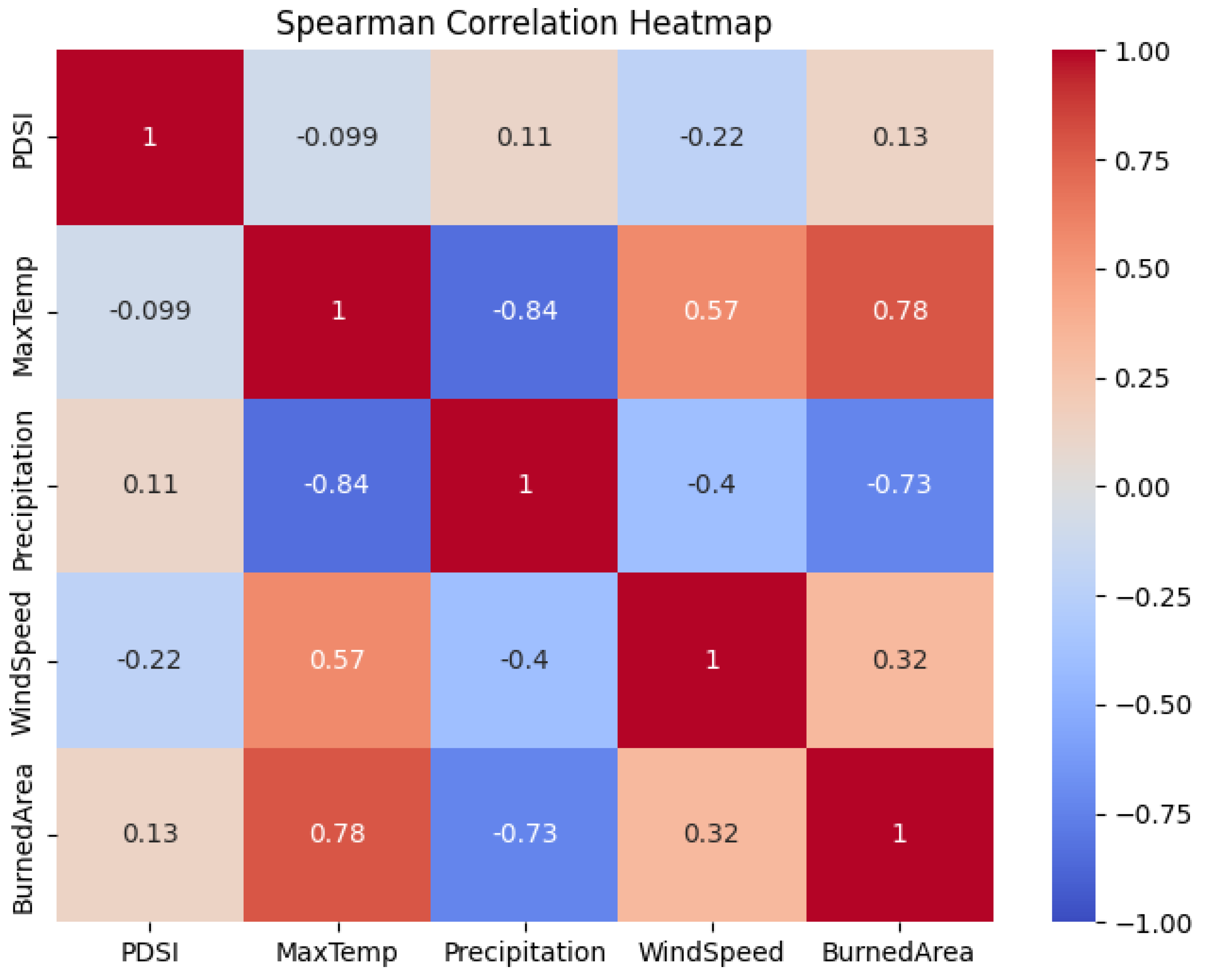

To explore monotonic associations between monthly burned area and climatic predictors in Kurdistan Region forests, we employed Spearman's rank correlation coefficient—a non-parametric measure robust to non-normal distributions and outliers prevalent in fire data (n=288 months, 2001–2024). This approach was preferred over Pearson's due to the skewed nature of burned area (median=7.05 km², 25% zeros) and predictors like precipitation (SD=65.52 mm, highly variable). The full correlation matrix (

Figure 5) and extracted pairwise values with burned area (

Table 5) reveal a landscape of interconnected drivers, dominated by temperature-moisture antagonism.

Maximum temperature (MaxTemp) exhibited the strongest positive monotonic relationship with burned area (r = 0.782, p < 0.001), indicating that hotter months consistently rank higher in fire extent—a pattern driven by enhanced evaporation, fuel desiccation, and ignition efficiency above ~30°C thresholds. Conversely, precipitation displayed a robust inverse association (r = -0.732, p < 0.001), where wetter periods suppress fires through sustained soil/vegetation moisture, aligning with the matrix's strong negative link between MaxTemp and precipitation (r = -0.842, p < 0.001). Wind speed showed a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.321, p < 0.001), facilitating spread in low-moisture conditions but tempered by its collinearity with MaxTemp (r = 0.573, p < 0.001). PDSI, despite chronic negativity (mean = -3.36), yielded a weaker positive tie (r = 0.128, p = 0.030), suggesting drought's influence is more baseline than episodic, with non-significant links to other variables (e.g., PDSI-MaxTemp r = -0.099, p = 0.095). All correlations with burned area were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.030), except non-significant inter-predictor pairs like PDSI-WindSpeed (r = -0.219, p < 0.001, but weak magnitude). Wind speed was included in the exploratory correlation analysis but subsequently excluded from regression modelling due to severe multicollinearity (VIF = 43.87).

These findings, visualized in the Spearman heatmap (

Figure 5), underscore a "heat-drought-moisture triad" where MaxTemp emerges as the linchpin (highest r), antagonizing precipitation while modestly amplified by wind. Subsequent subsections dissect multicollinearity (3.4.2) and model-based quantification (3.4.3–3.4.4), confirming these bivariate insights in multivariate contexts.

3.4.2. Multicollinearity Between Key Drivers of wildfires in Kurdistan Region

Multicollinearity among predictors can distort regression coefficients and inflate standard errors, potentially masking true relationships in fire risk modeling. To assess this, we computed variance inflation factors (VIF) for the initial set of climatic drivers—PDSI, MaxTemp, Precipitation, and WindSpeed—using monthly data from 2001 to 2024 (n=288). The original VIFs revealed pronounced concerns for MaxTemp (VIF = 28.72) and WindSpeed (VIF = 43.87), attributable to their strong positive inter-correlation (Spearman r = 0.573, p < 0.001), a common artifact in arid climates where heat exacerbates wind-driven desiccation (

Table 6). In contrast, PDSI (VIF = 2.76) and Precipitation (VIF = 3.89) exhibited low inflation, reflecting their relative independence.

To address this, WindSpeed was excluded as it contributed redundantly to the temperature-wind nexus without substantially enhancing explanatory power. The revised model with PDSI, MaxTemp, and Precipitation yielded uniformly low VIFs (<3: PDSI = 2.33, MaxTemp = 2.42, Precipitation = 1.29;

Table 7), confirming negligible multicollinearity and reliable coefficient estimates. This refinement aligns with the correlation matrix, where MaxTemp's dominance (r = 0.782 with burned area) persists without distortion. By resolving VIF concerns, the analysis ensures robust inference, paving the way for bivariate relationships and multivariate modeling, where temperature emerges as the pivotal driver.

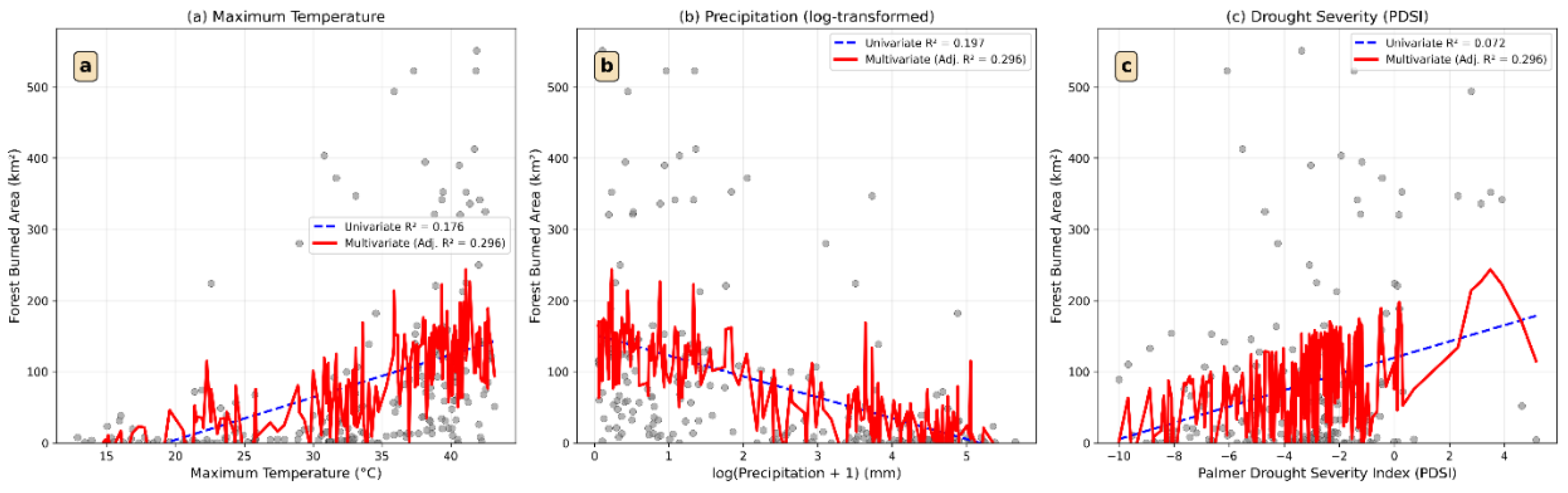

3.4.3. Linear relationships between burned area and key drivers

To quantify the explanatory power of individual and combined climatic drivers under a linear framework, ordinary least-squares (OLS) regressions were fitted to the subset of months with non-zero burned area (n = 199). Univariate regressions confirmed maximum temperature as the strongest single predictor (adjusted R² = 0.176, p < 0.001), followed by log-transformed precipitation (adjusted R² = 0.132, p < 0.001) and PDSI (adjusted R² = 0.072, p < 0.001).

A multiple linear regression including all three predictors (maximum temperature, PDSI, and log(Precipitation + 1)) substantially improved model performance, explaining 29.6 % of the variance in monthly forest burned area during fire months (adjusted R² = 0.296, F(3,195) = 28.8, p < 0.001). This increase over the best univariate model demonstrates considerable shared explanatory power among the predictors.

However, residual diagnostics revealed clear violations of OLS assumptions: pronounced non-linearity (particularly sharp thresholds at MaxTemp > ~32 °C and PDSI < –2), increasing residual variance with fitted values (heteroscedasticity), and influential outliers during extreme fire months. These patterns, together with the zero-inflated nature of the full 288-month dataset (~31 % zero-fire months), render standard linear regression unsuitable as the primary modelling framework. Accordingly, the zero-inflated negative binomial regression presented in

Section 3.4.4 — which accommodates count structure, excess zeros, overdispersion, and non-linear responses while providing interpretable incidence-rate ratios — was adopted as the final inferential model.

Figure 6. Relationships between monthly forest burned area (non-zero months only, n = 199) and the three climatic drivers in the Kurdistan Region, 2001–2024. Grey points = observed values; blue dashed line = univariate OLS fit; red solid line = predicted values from the multiple linear regression including all three predictors (adjusted R² = 0.296). Residual patterns and threshold effects visible in all panels motivate the use of zero-inflated negative binomial regression on the full dataset.

3.4.4. Wildfires explained by key climatic predictors in Kurdistan Region

Given the strongly zero-inflated and overdispersed nature of monthly burned-area data (approximately 25 % (72 of 288 months) from 2001–2024 recorded zero fire), a ZINB regression was employed (pseudo R² = 0.12, log-likelihood ratio test p < 0.001;

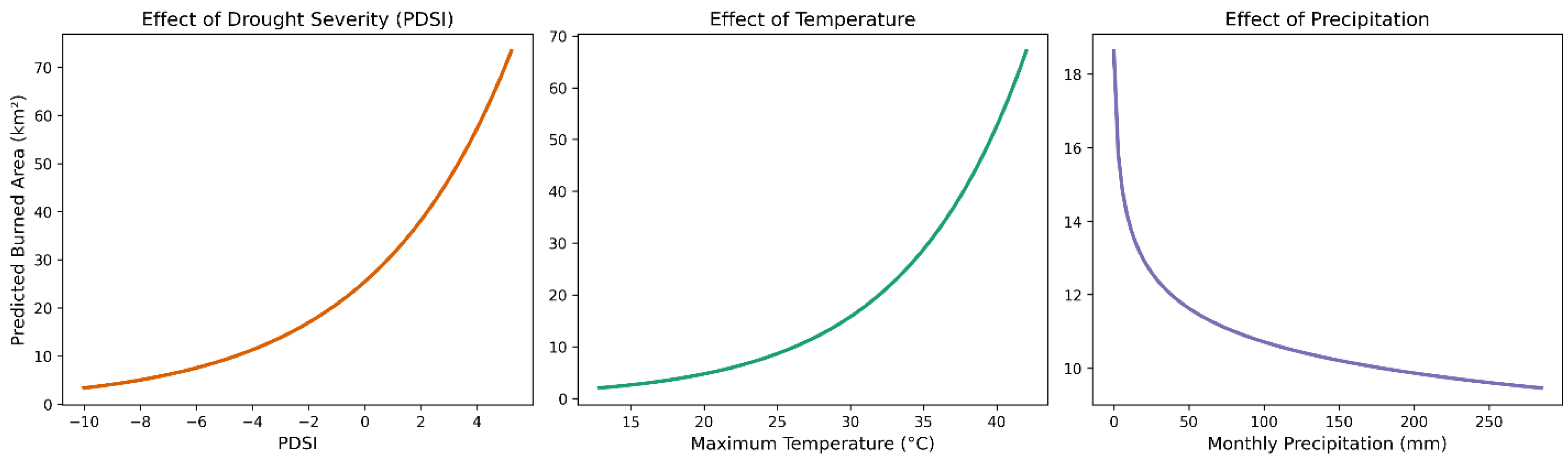

Table 8). In the count component of the model, which explains the magnitude of burned area when fires do occur, both drought severity and temperature emerged as highly significant positive drivers (

Figure 7). A one-unit decrease in the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI; i.e., increasing drought) raises expected burned area by 22.5 % (incidence-rate ratio, IRR = 1.225, p < 0.001), while each additional degree Celsius of monthly maximum temperature increases expected burned area by 12.8 % (IRR = 1.128, p < 0.001). Log-transformed monthly precipitation showed the expected negative direction but was not statistically significant (IRR = 0.89, p = 0.231), probably because most of its explanatory power is already captured by PDSI. The marginal-effect plots (

Figure 7) illustrate the pronounced non-linear escalation of predicted burned area at PDSI values below –2 (moderate-to-severe drought) and at maximum temperatures above ~32 °C, conditions that have become more frequent in the region over the study period. Together, these three climatic predictors account for a meaningful fraction of fire magnitude variability in a highly zero-inflated regional record, confirming that hotter and drier conditions are the primary climatic triggers of large fire months in Kurdistan Region forests. Although the multiple linear regression on non-zero months explained 29.6 % of variance (adjusted R² = 0.296), the zero-inflated negative binomial model was preferred because it uses the complete dataset (n = 288 months), properly handles excess zeros and overdispersion, and directly quantifies the multiplicative effect of climatic drivers on expected burned area.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation and Implications of Key Findings

The present study provides the first long-term (2001–2024) quantitative assessment of wildfire trends and drivers in the forested ecosystems of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq — a critically understudied and highly fire-prone region of the Middle East. Our analysis reveals a statistically significant upward trend in forest burned area of 17 km² year⁻¹ (p = 0.016), resulting in a cumulative total of approximately 8,542 km² burned over the 24-year period. This figure is equivalent to the current forest cover of ~2,000 km² having burned more four times over, reflecting intense fire recurrence within a limited woodland area and underscoring an accelerating threat to one of the most biodiverse and ecologically important oak-dominated ecosystems in the Zagros Mountains.

The upward trend in forest fires parallels the broader regional increase in total burned area (31 km² year⁻¹, p = 0.024), but the disproportionate contribution of extreme fire years (e.g., 2010, 2015, 2019–2020) to forest loss indicates that oak woodlands, while relatively resilient under normal conditions, become highly vulnerable during compound drought–heat events. The pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with Duhok and Sulaymaniyah governorates accounting for ~77 % of total forest burned area and exhibiting the strongest increasing trends, reflects steeper precipitation gradients and greater exposure to agricultural escape fires in southern and western oak belts.

Our monthly-scale analysis robustly identifies maximum temperature and antecedent drought (PDSI) as the primary climatic triggers of large fire months, with hotter and drier conditions explaining a meaningful fraction of fire-magnitude variability even in a highly zero-inflated record. The non-linear marginal effects — showing sharp escalation above ~32 °C and PDSI < –2 — confirm that Kurdistan Region forests are approaching critical climatic tipping points already observed elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, reliance on MODIS MCD64A1 at 500 m resolution likely underestimates small fires (< ~100 ha), which are common in fragmented oak landscapes and often human-ignited. Higher-resolution sensors such as Sentinel-2 or VIIRS could refine future estimates (Roteta et al., 2019). Second, while climatic drivers explain a substantial portion of interannual variability, anthropogenic factors (agricultural burning, land-use change, conflict-related ignitions) undoubtedly play a major role, particularly during extreme years (2019–2020). These were not explicitly modelled due to lack of reliable ignition and suppression data across the 24-year period. Third, the forest mask was derived from a single-year (2024) NDVI classification; historical forest cover change (deforestation, reforestation) was not accounted for and may slightly bias burn-rate calculations.

4.3. Comparison with Existing Literature

The observed upward trend in forest fire activity in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq is consistent with broader regional and global patterns of increasing wildfire regimes under climate warming. Rasul et al. (2020) documented a statistically significant national-scale increase in burned area across Iraq of 71.7 km² year⁻¹ from 2001 to 2019, with a particularly sharp rise in 2019 (approximately eight times the long-term average) and the highest burned-area concentrations in the northern governorates — a pattern that directly includes the oak-dominated forests of the Kurdistan Region. Mohammadi & Hejazizadeh (2023) further confirmed that global warming has significantly elevated wildfire risk throughout Iran, with temperature trends at multiple stations showing significant upward shifts at 95–99 % confidence levels, leading to hotter and drier conditions that strongly favour fire occurrence. These findings align with documented increases in wildfire frequency and extent across the western United States (Salguero et al., 2020; Weber et al., 2020), extreme fire events globally (Cunningham et al., 2024), and parts of Siberia (Tomshin & Solovyev, 2022), where warmer and drier conditions have similarly driven larger and more frequent fires.

4.4. Future Research Directions and Management Implications

The implications of these findings are profound. Under continued high-emission trajectories (SSP585), northern Iraq — including the oak-forested governorates of Duhok, Erbil, and Sulaymaniyah — is projected to experience strong seasonal warming, with autumn mean temperatures shifting such that the 15–20 °C class expands from 27.7 % to 96.3 % of the area by 2021–2040 relative to the 1985–2015 baseline, accompanied in most seasons by increased but highly variable precipitation (Abdulsahib et al., 2024). These combined hotter and (in some seasons) wetter conditions are likely to push large portions of Kurdistan’s oak forests past critical physiological and fire-recovery thresholds within the coming decades, accelerating transitions toward shrubland or grassland states, especially on drier southern and western aspects. Given the region’s role as a biodiversity hotspot, carbon sink, watershed protector, and provider of cultural and economic services, such ecosystem shifts would have far-reaching ecological, hydrological, and socio-economic consequences.

Future research should prioritise (i) integration of high-resolution Sentinel-2/VIIRS data with deep-learning burned-area mapping, (ii) development of anthropogenic ignition datasets through stakeholder engagement, (iii) incorporation of lagged climatic predictors and fire-weather indices , and (iv) projection of future fire regimes under CMIP6 scenarios. From a management perspective, governorate-specific strategies—fuel-reduction zones in the high-risk Duhok and Sulaymaniyah oak belts, community-based fire brigades in Erbil, and continued reforestation in Halabja—are urgently needed. Immediate policy action and enhanced cross-border collaboration are essential to safeguard this unique Zagros woodland heritage in an increasingly fire-prone future.

5. Conclusion

This study provides the first comprehensive, long-term (2001–2024) quantification of wildfire trends and their climatic drivers across the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and its critically important oak-dominated forests — a Zagros biodiversity hotspot facing rapidly escalating fire risk under climate change. Using MODIS MCD64A1 burned-area data and robust non-parametric and count-modelling approaches, we documented a statistically significant upward trend in total regional burned area of 31 km² year⁻¹ (Mann–Kendall p = 0.024), with a mean annual extent of 687 km² and a cumulative total of 16,486 km². Within forests, burned area increased at 17 km² year⁻¹ (p = 0.016), averaging 356 km² year⁻¹ and accumulating 8,542 km² — more than four times the current forest cover — with extreme events disproportionately concentrated in Duhok and Sulaymaniyah governorates (~77 % of total forest loss). Monthly-scale zero-inflated negative binomial regression confirmed maximum temperature and drought severity as the dominant climatic drivers: each 1 °C increase in monthly maximum temperature raises expected burned area by ~13 % (IRR = 1.128, p < 0.001), and a one-unit worsening of PDSI increases it by 22.5 % (IRR = 1.225, p < 0.001), with pronounced non-linear escalation above ~32 °C and PDSI < –2.

The oak woodlands of the Kurdistan Region — a Zagros biodiversity hotspot, critical carbon sink, and cultural landscape — are transitioning from relatively fire-resilient systems to ones increasingly vulnerable to catastrophic loss under compound heat–drought extremes that are becoming more frequent with ongoing climate change. The documented upward trajectory, if unchecked, risks irreversible ecosystem state shifts toward fire-prone shrubland or grassland within decades, with cascading effects on water regulation, soil stability, and rural livelihoods dependent on non-timber forest products.

Urgent, evidence-based action is required. Governorate-tailored fire-management plans should prioritise fuel-reduction zones and early-warning systems in the high-risk Duhok and Sulaymaniyah oak belts, expansion of community fire brigades in Erbil, and continued protection of reforestation gains in Halabja. Institutional investment in higher-resolution monitoring (Sentinel-2/VIIRS), cross-border fire suppression coordination with Iran and Turkey, and integration of anthropogenic ignition data into predictive models are essential next steps. Without rapid adaptation, the forests of Kurdistan Region — among the last extensive oak woodlands in the Middle East — face an existential threat in an increasingly fire-prone future. This study provides the quantitative baseline and diagnostic framework needed to guide such interventions, underscoring that while climate is the primary amplifier of fire risk, proactive regional governance remains the most powerful lever for safeguarding this irreplaceable natural heritage.

References

- Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A., & Hegewisch, K. C. (2018). TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Scientific Data, 5(1), 1–12.

- Abatzoglou, J. T., Williams, A. P., & Barbero, R. (2019). Global Emergence of Anthropogenic Climate Change in Fire Weather Indices. Geophysical Research Letters, 46(1), 326–336. [CrossRef]

- Abdulsahib, S. M., Zubaidi, S. L., Almamalachy, Y., & Dulaimi, A. (2024). Temperature and Precipitation Change Assessment in the North of Iraq Using LARS-WG and CMIP6 Models. Water, 16(19). [CrossRef]

- Beygi Heidarlou, H., Banj Shafiei, A., Erfanian, M., Tayyebi, A., & Alijanpour, A. (2020). Armed conflict and land-use changes: Insights from Iraq-Iran war in Zagros forests. Forest Policy and Economics, 118(C). https://ideas.repec.org//a/eee/forpol/v118y2020ics1389934118303496.html.

- Cunningham, C. X., Williamson, G. J., & Bowman, D. M. J. S. (2024). Increasing frequency and intensity of the most extreme wildfires on Earth. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 8(8), 1420–1425. [CrossRef]

- Eklund, L., Abdi, A. M., Shahpurwala, A., Dinc, P., Eklund, L., Abdi, A. M., Shahpurwala, A., & Dinc, P. (2021). On the Geopolitics of Fire, Conflict and Land in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Remote Sensing, 13(8). [CrossRef]

- Eklund, L., & Dinc, P. (2024). Fires as collateral or means of war: Challenges of environmental peacebuilding in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Ecology and Society, 29(3). [CrossRef]

- EPIC. (2022). Recovering the wild, Iraq. Botanic Gardens Conservation International. https://www.bgci.org/our-work/projects-and-case-studies/recovering-the-wild/.

- Giglio, L., Boschetti, L., Roy, D. P., Humber, M. L., & Justice, C. O. (2018). The Collection 6 MODIS burned area mapping algorithm and product. 217, 72–85.

- Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D., & Moore, R. (2017). Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment, 202, 18–27.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [CrossRef]

- Jaafari, A., Zenner, E. K., & Pham, B. T. (2018). Wildfire spatial pattern analysis in the Zagros Mountains, Iran: A comparative study of decision tree based classifiers. Ecological Informatics, 43, 200–211. [CrossRef]

- Jolly, W. M., Cochrane, M. A., Freeborn, P. H., Holden, Z. A., Brown, T. J., Williamson, G. J., & Bowman, D. M. J. S. (2015). Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nature Communications, 6(1), 7537. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M. W., Abatzoglou, J. T., Veraverbeke, S., Andela, N., Lasslop, G., Forkel, M., Smith, A. J. P., Burton, C., Betts, R. A., Van Der Werf, G. R., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Santín, C., Kolden, C., Doerr, S. H., & Le Quéré, C. (2022). Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change. Reviews of Geophysics, 60(3), e2020RG000726. [CrossRef]

- Khwarahm, N. R. (2020). Mapping current and potential future distributions of the oak tree (Quercus aegilops) in the Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Ecological Processes, 9(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Planning, KRG. (2025). Weather Statistics in Kurdistan Region Governorates for the years 2012–2024.

- Mohammadi, N., & Hejazizadeh, Z. (2023). Investigating the Effect of Global Warming on Increasing the Risk of Wildfires in Iran. Disaster Prevention and Management Knowledge (Quarterly), 13(3), 296–317. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J., Dutra, E., Agustí-Panareda, A., Albergel, C., Arduini, G., Balsamo, G., Boussetta, S., Choulga, M., Harrigan, S., Hersbach, H., Martens, B., Miralles, D. G., Piles, M., Rodríguez-Fernández, N. J., Zsoter, E., Buontempo, C., & Thépaut, J.-N. (2021). ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth System Science Data, 13(9), 4349–4383. [CrossRef]

- Rasul, A., Ibrahim, G. R. F., Hameed, H. M., & Tansey, K. (2020). A trend of increasing burned areas in Iraq from 2001 to 2019. [CrossRef]

- Salguero, J., Li, J., Farahmand, A., Reager, J. T., Salguero, J., Li, J., Farahmand, A., & Reager, J. T. (2020). Wildfire Trend Analysis over the Contiguous United States Using Remote Sensing Observations. Remote Sensing, 12(16). [CrossRef]

- Sissakian, V. K., Jab’bar, M. F. A., Al-Ansari, N., & Knutsson, S. (2015). Development of Gulley Ali Beg Gorge in Rawandooz Area, Northern Iraq. Engineering, 7(1), 16–30. [CrossRef]

- Talebi, K. S., Sajedi, T., & Pourhashemi, M. (2013). Forests of Iran: A Treasure from the Past, a Hope for the Future. Springer.

- Tomshin, O., & Solovyev, V. (2022). Spatio-temporal patterns of wildfires in Siberia during 2001–2020. Geocarto International, 37(25), 7339–7357. [CrossRef]

- Turco, M., von Hardenberg, J., AghaKouchak, A., Llasat, M. C., Provenzale, A., & Trigo, R. M. (2017). On the key role of droughts in the dynamics of summer fires in Mediterranean Europe. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 81. [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, G. R., Randerson, J. T., Giglio, L., van Leeuwen, T. T., Chen, Y., Rogers, B. M., Mu, M., van Marle, M. J. E., Morton, D. C., Collatz, G. J., Yokelson, R. J., & Kasibhatla, P. S. (2017). Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth System Science Data, 9(2), 697–720. [CrossRef]

- Weber, K. T., Yadav, R., Weber, K. T., & Yadav, R. (2020). Spatiotemporal Trends in Wildfires across the Western United States (1950–2019). Remote Sensing, 12(18). [CrossRef]

- Zittis, G., Almazroui, M., Alpert, P., Ciais, P., Cramer, W., Dahdal, Y., Fnais, M., Francis, D., Hadjinicolaou, P., Howari, F., Jrrar, A., Kaskaoutis, D. G., Kulmala, M., Lazoglou, G., Mihalopoulos, N., Lin, X., Rudich, Y., Sciare, J., Stenchikov, G., … Lelieveld, J. (2022). Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Reviews of Geophysics, 60(3), e2021RG000762. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).