Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

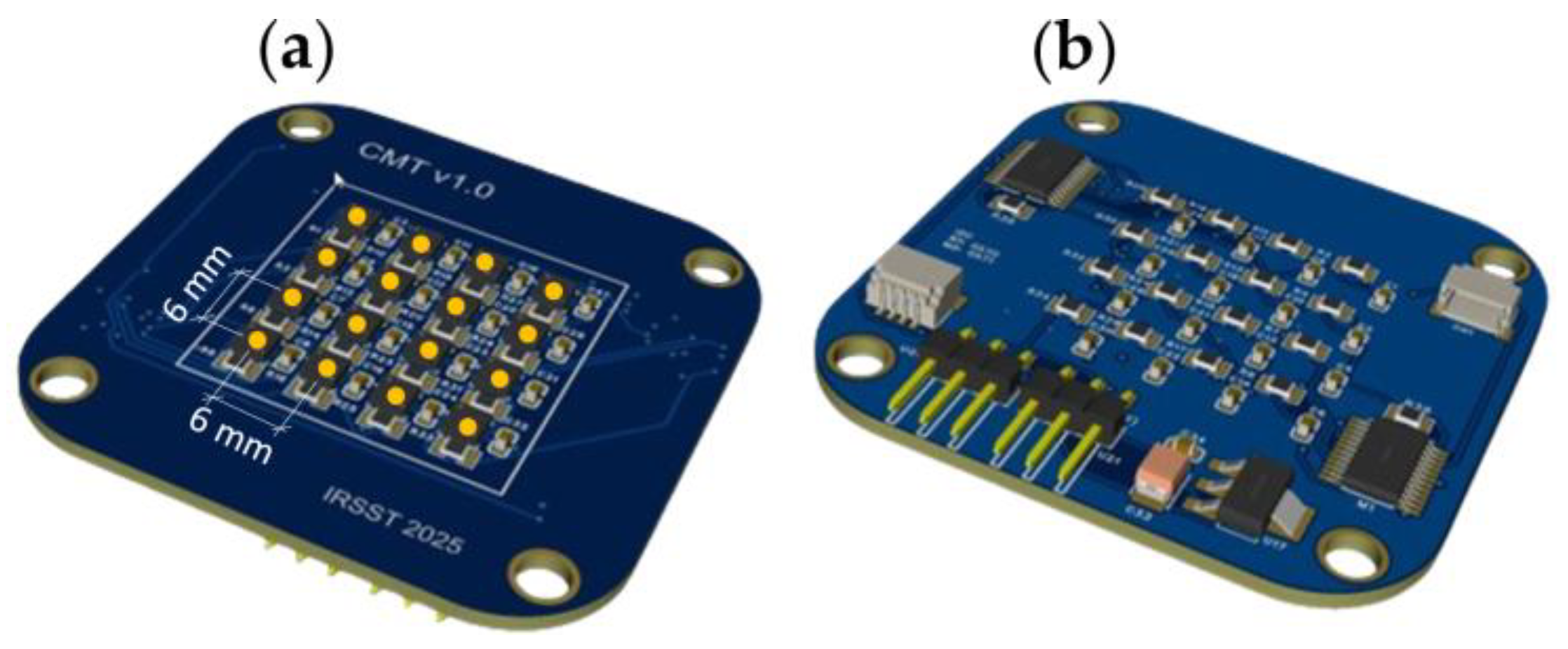

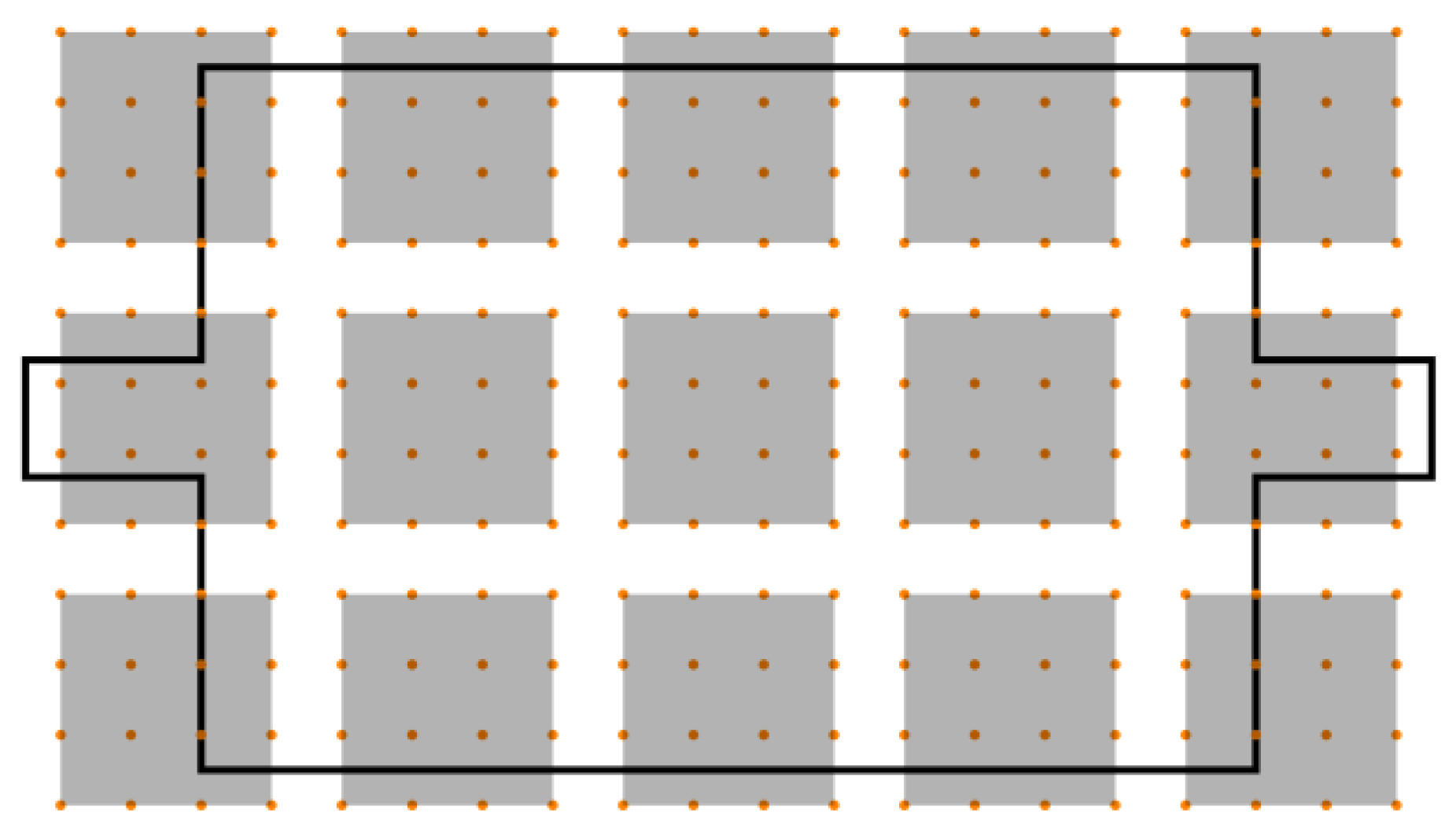

2.1. The Magnetic Sensor Array (MSA)

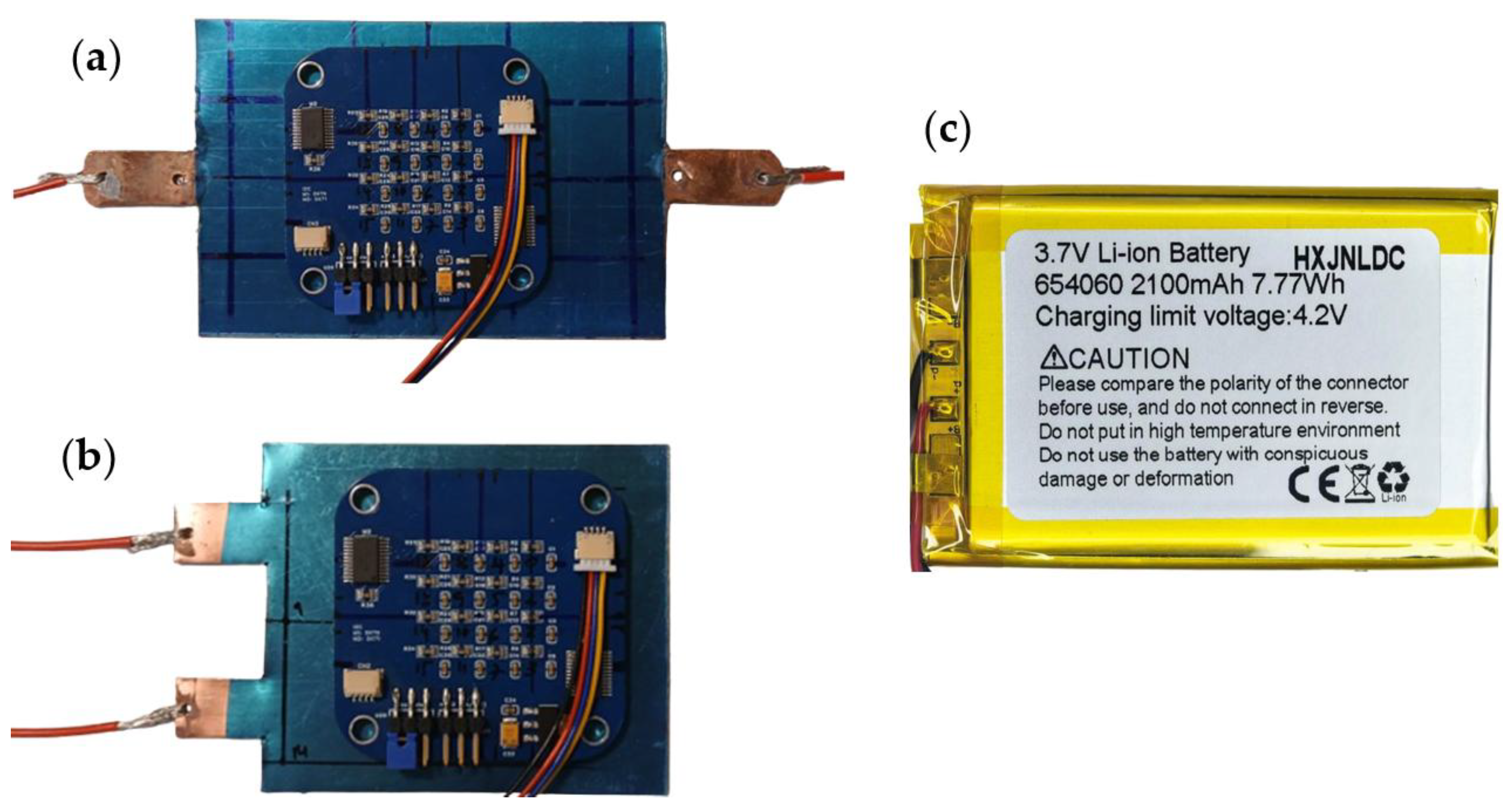

2.2. The Examined Samples

2.2.1. Planar Copper Conductors

2.2.2. Lithium-Polymer (LiPo) Battery

2.3. The Measurement Procedure

2.4. Post-Treatment of the Experimental Data

2.5. Numerical Computation of the B Field for the Copper Samples

3. Results and Discussion

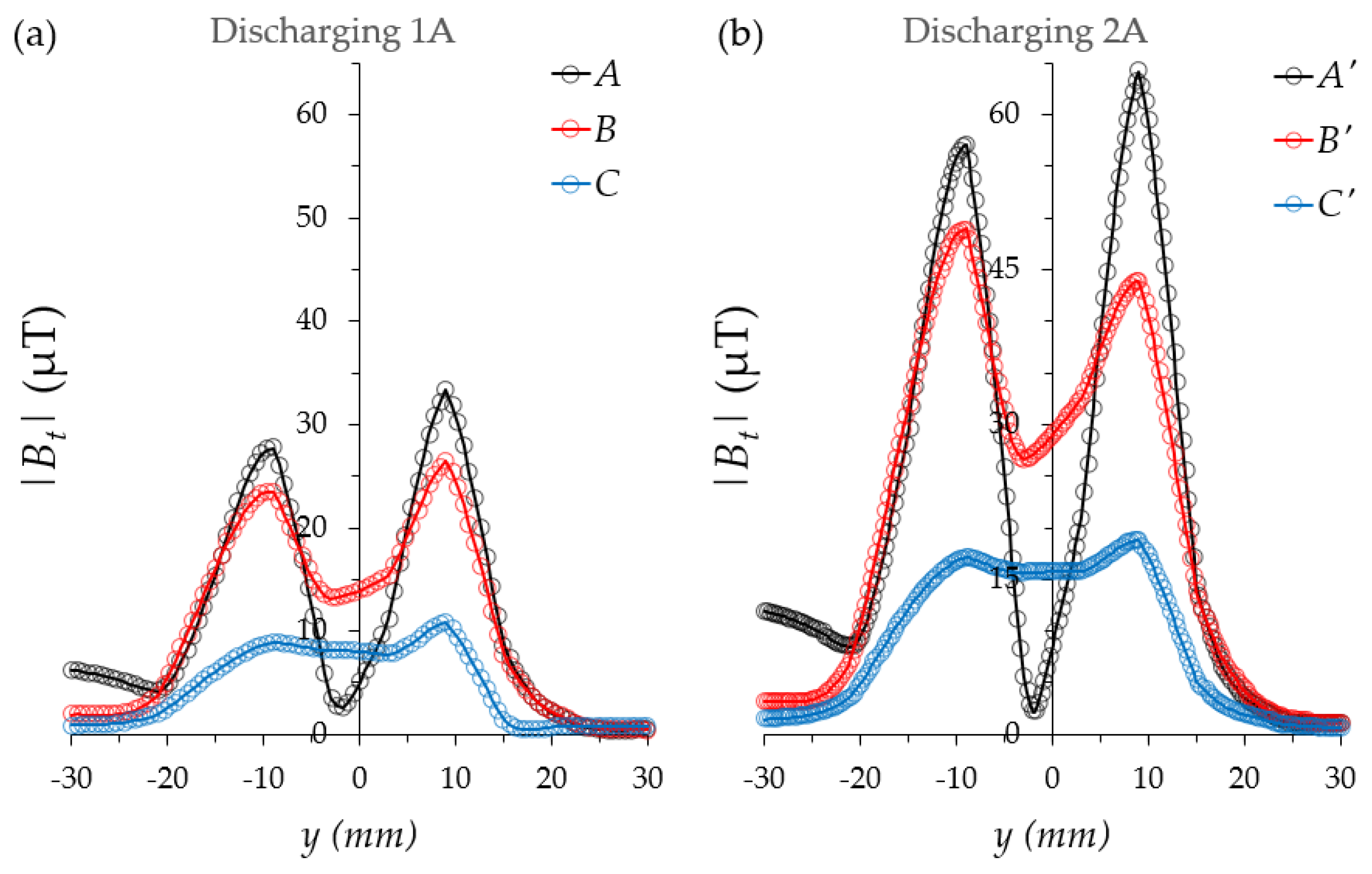

3.1. Magnetic Field of Copper Samples

3.2. Magnetic Field of a LiPo Battery

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ripka, P. Magnetic Sensors and Magnetometers; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.W.; Jeng, J.T. Implementation of 16-channel AMR sensor array for quantitative mapping of two-dimension current distribution series. IEEE Trans. Mag. 2018, 54, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Huang, H.; Peng, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y. Algorithm research on the conductor eccentricity of a circular dot matrix Hall high current sensor for ITER. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2022, 50, 1962–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Song, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S. Magnetic signal denoising based on auxiliary sensor array and deep noise reconstruction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.Y.; Hsieh, S.H.; Chen, C.H.; Lin, C.H. High-performance chip design with parallel architecture for magnetic field imaging system. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eto, A.; Akimoto, Y.; Okajima, K.; Okano, J.; Onoue, Y. Evaluation of lithium-ion batteries with different structures using magnetic field measurement for onboard battery identification. Green Energy Intell. Transport. 2025, 4, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wan, X.; Lin, Y.; Wu, H.; Tan, X.; Zou, S.; Zhu, M.; Liu, J. Magnetic field--based non--destructive testing techniques for battery diagnostics. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 2404295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, K. State monitoring of lithium--ion batteries based on in situ magnetic techniques: A review. Ionics 2025, 31, 7595–7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K. Research progress of lithium-ion battery monitoring technology based on noninvasive magnetic induction sensors. ACS Appl. Electr. Mater. 2025, 7, 4907–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Yu, C. Research on charging monitoring method for lithium-ion batteries based on magnetic field sensing. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2024, 19, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, R. A concise review of power batteries and battery management systems for electric and hybrid vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waag, W.; Fleischer, C.; Sauer, D.U. Critical review of the methods for monitoring of lithium-ion batteries in electric and hybrid vehicles. J. Power Source 2014, 258, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborelli, C.; Onori, S.; Maes, S.; Sveum, P.; Al-Hallaj, S.; Al-Khayat, N. Advanced battery management system design for SOC/SOH estimation for e-bikes applications. Int. J. Powertrains 2017, 5, 325–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliaperumal, M.; Dharanendrakumar, M.S.; Prasanna, S.; Abhishek, K.V.; Chidambaram, R.K.; Adams, S.; Zaghib, K.; Reddy, M.V. Cause and mitigation of lithium-ion battery failure—A review. Materials 2021, 14, 5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, D.; Schweiger, H.-G. Possibilities for a quick onsite safety-state assessment of stand-alone lithium-ion batteries. Batteries 2022, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, R.; Moeslund, T.B. Thermal cameras and applications: A survey. Machine Vision Appl. 2014, 25, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. A study on thermal performance of batteries using thermal imaging and infrared radiation. J. of Ind. and Eng. Chem. 2017, 45, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafadarova, N.; Sotirov, S.; Herbst, F.; Stoynova, A.; Rizanov, S. A system for determining the surface temperature of cylindrical lithium-ion batteries using a thermal imaging camera. Batteries 2023, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavaš, H.; Barić, T.; Karakašić, M.; Keser, T. Application of infrared thermography in e-bike battery pack detail analysis—Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, X.C.A.; Laureti, S.; Ricci, M.; Cappuccino, G. A review of non-destructive techniques for lithium-ion battery performance analysis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, J.; Shin, Y.; Lee, H. Multiscale imaging techniques for real-time, noninvasive diagnosis of li-ion battery failures. Small Sci. 2023, 3, 2300063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutam, S.; Omar, N.; Van den Bossche, P.; Van Mierlo, J.; Rodriguez, L.; Nieto, N.; Swierczynski, M. Surface temperature evolution and the location of maximum and average surface temperature of a lithium-ion pouch cell under variable load profiles. European Electric Vehicle Conf. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Shin, Y.; Chang, H.; Jin, D.; Lee, H.; Lim, M.; Seo, J.; Band, T.; Kaufmann, K.; Moon, J.; et al. Diagnosis of current flow patterns inside fault-simulated li-ion batteries via non-invasive, in operando magnetic field imaging. Small Methods 2023, 7, 2300748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Peng, D.; Chen, Y.; Ma, C.; Qu, W.; Liu, S.; Luo, L. Three-dimensional electrochemical-magnetic-thermal coupling model for lithium-ion batteries and its application in battery health monitoring and fault diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bason, M.G.; Coussens, T.; Withers, M.; Abel, C.; Kendall, G.; Krüger, P. Non-invasive current density imaging of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sour. 2022, 533, 231312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhan, Z.; Cui, B.; Wang, Y.; Yin, G.; Han, G.; Xiang, L.; Du, C. Non-destructive detection techniques for lithium-ion batteries based on magnetic field characteristics-A model-based study. J. Power Sour. 2024, 604, 234511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchle, F.; Grimsmann, F.; von Kessel, O.; Birke, K.P. Defect detection in lithium-ion cells by magnetic field imaging and current reconstruction. J. Power Sour. 2023, 558, 232587.10–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, J.M.; Ali, A.; Yan, X.; Pei, G.; Zhang, S.; Naveed, A.; Shehzad, K.; Shahnavaz, Z.; Ahmad, F.; Yousaf, B. Sensors innovations for smart lithium-based batteries: Advancements, opportunities, and potential challenges. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Okada, H.; Yabumoto, K.; Matsuda, S.; Mima, Y.; Kimura, N.; Kimura, K. Non-destructive visualization of short circuits in lithium-ion batteries by a magnetic field imaging system. Jap. J. of Appl. Phys. 2021, 60, 056502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, K.; Mao, L.; He, Q.; Wu, Q.; Li, Z. Evaluation of lithium-ion battery pack capacity consistency using one-dimensional magnetic field scanning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.E.; Stone, D.A.; Foster, M.P.; Tennant, A. Spatially resolved measurements of magnetic fields applied to current distribution problems in batteries. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2015, 64, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhatov, A.; Le, T.A.; Pham, T.T.; Do, T.D. A comprehensive review on magnetic imaging techniques for biomedical applications. Nano Select 2023, 4, 213–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhou, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, X. A High-Resolution Magnetic Field Imaging System Based on the Unpackaged Hall Element Array. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, R. Magnetic characterization of geologic materials with first-order reversal curves. In Magnetic measurement techniques for materials characterization, 1st ed.; Franco, V., Dodrill, B., Eds.; Spinger: Switzerland, 2021; pp. 455–604. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wang, J. Magnetic sensors for navigation applications: An overview. J. Navig. 2014, 67, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMC5983MA-AMR Magnetometer-MEMSIC Semiconductor Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.memsic.com/magnetometer-5 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Pan, L.; Xie, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Bao, X.; Shang, J.; Li, R.-W. Flexible Magnetic Sensors. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. Numerical recipes: The art of scientific computing, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2007; pp. 110–150. [Google Scholar]

- Meeker, D.C. Finite Element Method Magnetics, Version 4.2 (28 Feb 2018 Build). Available online: https://www.femm.info (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Iwata, G.Z.; Mohammadi, M.; Silletta, E.V.; Wickenbrock, A.; Blanchard, J.W.; Budker, D.; Jerschow, A. Sensitive magnetometry reveals inhomogeneities in charge storage and weak transient internal currents in Li-ion cells Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 10667–10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchle, F.; Grimsmann, F.; von Kessel, O.; Birke, K.P. Direct measurement of current distribution in lithium-ion cells by magnetic field imaging, J. Power Sour. 2021, 507, 230292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Kishimoto, Y.; Togo, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ohtsuka, T.; Amaya, K. Estimation method of current density between laminated thin sheets by inverse analysis of magnetic field (Application to short circuit localization). Eur. J. of Emergency Med. 2016, 3, 16–00046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Roth, B.J.; Sepulveda, N.G.; Wikswo, J.P. Using a magnetometer to image a two--dimensional current distribution. J. Appl. Phys. 1989, 65, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, R.; Kuhn, L.; Potthast, R. Reconstruction of a current distribution from its magnetic field. Inv. Probl. 2002, 18, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).