Submitted:

29 November 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Metastatic relapse often reflects the survival of a small population of disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) that take up residence in distant organs and then shift into a dormant state. Rather than dividing, these cells sit quietly for long periods and rely on local niche signals to stay inactive and avoid therapy. Dormant cells are difficult to eliminate because the immune system cannot detect them, and treatments aimed at actively growing cells are ineffective. DTCs stop oncogenic signaling and start stress-response and cell-cycle arrest pathways. These pathways are often characterized by higher levels of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors and greater p38 signaling than ERK signaling. LIFR–STAT3 signaling in the bone marrow supports quiescence in breast cancer cells, while inflammatory cytokines and Wnt/BMP antagonists in the lung microenvironment can trigger reactivation of cancer DTCs. Because these dormant DTCs are not cycling, standard cytotoxic agents rarely remove them. Current strategies are now testing immune-directed therapies. Recent single-cell and long-read sequencing efforts have started to reveal the transcriptional programs that mark DTCs, including stress-response and quiescence signatures that differ from the primary tumor. These insights are shaping therapies for interrupting dormancy and lowering the risk of late metastatic relapse.

Keywords:

Introduction

1. Metastasis-Inducing Genes and Mechanisms

2. Epigenetic Regulators of Metastasis

| Gene name | Function | Description | REF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snail | EMT, CAF activation, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | Induces EMT and invasion in carcinoma cells (Represses E-cadherin). Required for CAF activation; CAFs secrete PGE₂ and cytokines to drive tumor invasion (Regulates mesenchymal differentiation, wound healing) | 51 |

| TWIST1 | EMT, PDGFRα→Src, invadopodia | TWIST1 EMT TF: invadopodia formation (via PDGFRα/Src) Drives EMT, motility, invadopodia-mediated ECM degradation (Not directly studied). Upregulated in CAFs of many tumors: Twist1 promotes invasion and tumor growth. | 21 |

| SP1 | Pan-cancer TF, survival/invasion, WNT/β-catenin | Pan-cancer TF; induces WNT signaling, survival, and invasion. Master regulator of metastasis genes; enhances WNT/β-catenin signaling in tumor cells. Drives expression of angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF); WNT signals from stroma to endothelium. | 52, 53 |

| IL-6 | STAT3/EMT; CAF source; angiogenesis | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; activates JAK/STAT3, EMT receptor-expressing carcinoma cells undergo STAT3-dependent EMT and proliferation. Promotes angiogenesis and leukocyte recruitment in tumor vessels. Secreted by CAFs (and tumor cells); drives EMT/migration of cancer cells. IL-6 can recruit and modulate MSCs (MSC chemotaxis, differentiation) | 54, 55 |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | Angiogenesis, EMT/invasion, CXCR1/2 | Promotes angiogenesis, EMT, and invasion. Tumor-derived IL-8 induces autocrine EMT/invasion and survival. Potent angiogenic factor; stimulates endothelial proliferation and vessel permeability. CAFs secrete IL-8 to boost tumor angiogenesis and invasion. MSCs respond to IL-8 (via CXCR1/2), promotes MSC migration and possibly MSC-to-CAF transition. | 56, 57 |

| CXCL1 | Neutrophil recruitment, angiogenesis | CXCL1 Chemokine (ELR+); recruits neutrophils, fosters angiogenesis. Tumor-secreted CXCL1 creates a pro-inflammatory niche for invasion (by analogy to IL-8). Angiogenic; contributes to neovascularization (via CXCR2). Expressed by CAFs and TAMs; enhances tumor cell motility and chemoresistance (paracrine). May attract MSCs to the tumor; role is less defined than IL-8 | 58, 59 |

| CXCR4 | CXCL12 homing, organotropism | CXCR4 Chemokine receptor; guides cells to CXCL12-rich organs. Binds CXCL12 to direct cancer cell homing/migration to metastatic sites (lung, liver, bone). Endothelial cells produce CXCL12; CXCR4+ tumor cells adhere to the vasculature and extravasate. CXCR4 is expressed on fibroblasts/CAFs; CXCL12 from stroma promotes tumor-CAF interactions. Highly expressed on MSCs; mediates MSC homing and survival. | 60, 61 |

| MMP9 | ECM degradation, growth-factor activation, angiogenesis | MMP9 Secreted matrix metalloprotease; cleaves ECM, activates growth factors. Tumor cells secrete MMP9 to breach the basement membrane (promoting intravasation). Degrades endothelial basement membranes to enable angiogenesis and metastasis. CAFs/myofibroblasts produce MMP9 to remodel the stroma and release pro-metastatic signals. MSCs secrete MMP9 to facilitate migration; MSC-derived MMPs shape the metastatic niche. | 62, 63 |

| MMP1 | Interstitial collagenase, invasion/angiogenesis | MMP1 Interstitial collagenase; degrades type-I/III collagen. Tumor-derived MMP1 promotes invasion through dense stroma, enabling new vessel growth by remodeling perivascular ECM. CAFs produce MMP1 to stiffen or remodel the matrix, enabling tumor spreading. MSCs may also express MMP1 in differentiation contexts. | 64, 65 |

| EZH2 | H3K27me3 silencing, EMT, stromal remodeling | EZH2 Histone methyltransferase; epigenetic silencer of adhesion genes. Silences E-cadherin/epithelial genes, activating EMT and invasion (May promote EndMT by methylating endothelial promoters). Drives fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition; promotes fibrotic stroma. Regulates MSC proliferation/differentiation (Wound healing analogies). | 66, 67 |

| FOXM1 | EMT, MMPs, angiogenesis | FOXM1 Forkhead TF; drives cell cycle, EMT (upregulates Snail/MMPs). In tumor cells, FOXM1 induces MMP2/9 and EMT factors, enhancing invasion. Promotes angiogenesis via VEGF expression; also implicated in EndMT in fibrosis. Shown to regulate CAF proliferation and extracellular proteases (in some tumors). May influence MSCs’ proliferative and migratory potential FOSL1 (FRA1) AP-1 subunit; EMT and invasion activator. Upregulates genes involved in motility (e.g., MMPs); promotes a mesenchymal phenotype. Stimulates VEGF and inflammatory cytokines, aiding vessel formation. In stromal cells, it supports the production of pro-tumorigenic ECM factors. In MSCs, differentiation may tilt toward a CAF-like state. | 68, 69 |

| E2F1 | Cell cycle invasion/angiogenesis programs | E2F1 Cell-cycle TF; pro-metastatic when overexpressed. Aside from proliferation, E2F1 can induce MMPs and EMT-associated genes. Drives expression of angiogenic factors (FGF, VEGF); can act in the endothelium. Linked to fibroblast proliferation; may contribute to desmoplasia. Activates proliferation of MSCs and endothelial precursors. | 70 |

| MYB | stemness/invasion; angiogenic transcription | MYB Transcription factor can promote stemness and invasion. Activates target genes (including MMPs, EMT factors) in carcinomas. Regulates angiogenic gene expression (e.g., VEGFR). Influences fibroblast proliferation; MYB is expressed in some CAF subsets. Helps maintain MSC self-renewal; influences differentiation pathways. | 71 |

| PTTG1 (Securin) | Genomic instability, EMT, invasion | PTTG1 (Securin) Promotes genetic instability and EMT. Overexpressed PTTG1 drives EMT and cell motility in cancer cells. May enhance secretion of angiogenic factors (through p53 inhibition). In fibroblasts, PTTG1 can promote proliferation and matrix production. In MSCs, PTTG1 supports proliferation, possibly aiding their tumorigenic roles. | 72, 73 |

| YBX1 | EMT, stress survival, drug resistance | YBX1 RNA/DNA-binding protein; induces EMT and stress survival. Activates EMT-related mRNAs (Snail, Twist) and drug resistance pathways in tumors. Regulates VEGF expression under hypoxia, promoting angiogenesis. Contributes to fibroblast activation by stabilizing cytokine mRNAs. Modulates MSC plasticity and response to microenvironmental stress. | 74, 75 |

| BIRC5 (Survivin) | Anoikis resistance, survival of CTCs/ endothelium | BIRC5 (Survivin) Inhibitor of apoptosis; cell division regulator. Upregulated in metastatic tumors to allow anoikis resistance and survival in circulation. Supports the survival of proliferating endothelium in tumor vessels. Protects CAFs/myofibroblasts from apoptosis, sustaining pro-metastatic stroma. Ensures MSC survival in harsh metastatic niches. | 76, 77 |

| ZEB2 | EMT TF; metastasis and stromal/EndMT links | ZEB2 EMT transcription factor; represses epithelial genes. Drives EMT and mesenchymal phenotype in carcinoma cells (analogous to Snail/Zeb1) (Possible role in EndMT/transdifferentiation of endothelium). Induces fibroblast-like program in epithelial and endothelial cells. In MSCs, ZEB2 may regulate multilineage differentiation toward mesenchyme. | 78, 79 |

3. Extracellular Proteases and Matrix Modifiers in Metastatic Progression

4. Mechanisms of Immune Evasion in Metastatic Cancer

5. Cytokine and Chemokine Networks in Metastatic Dissemination

6. Pre-Metastatic Niche Formation and Organ-Specific Colonization

7. Tumor Dormancy

8. Tumor Metastasis Mechanisms by Tumor Type

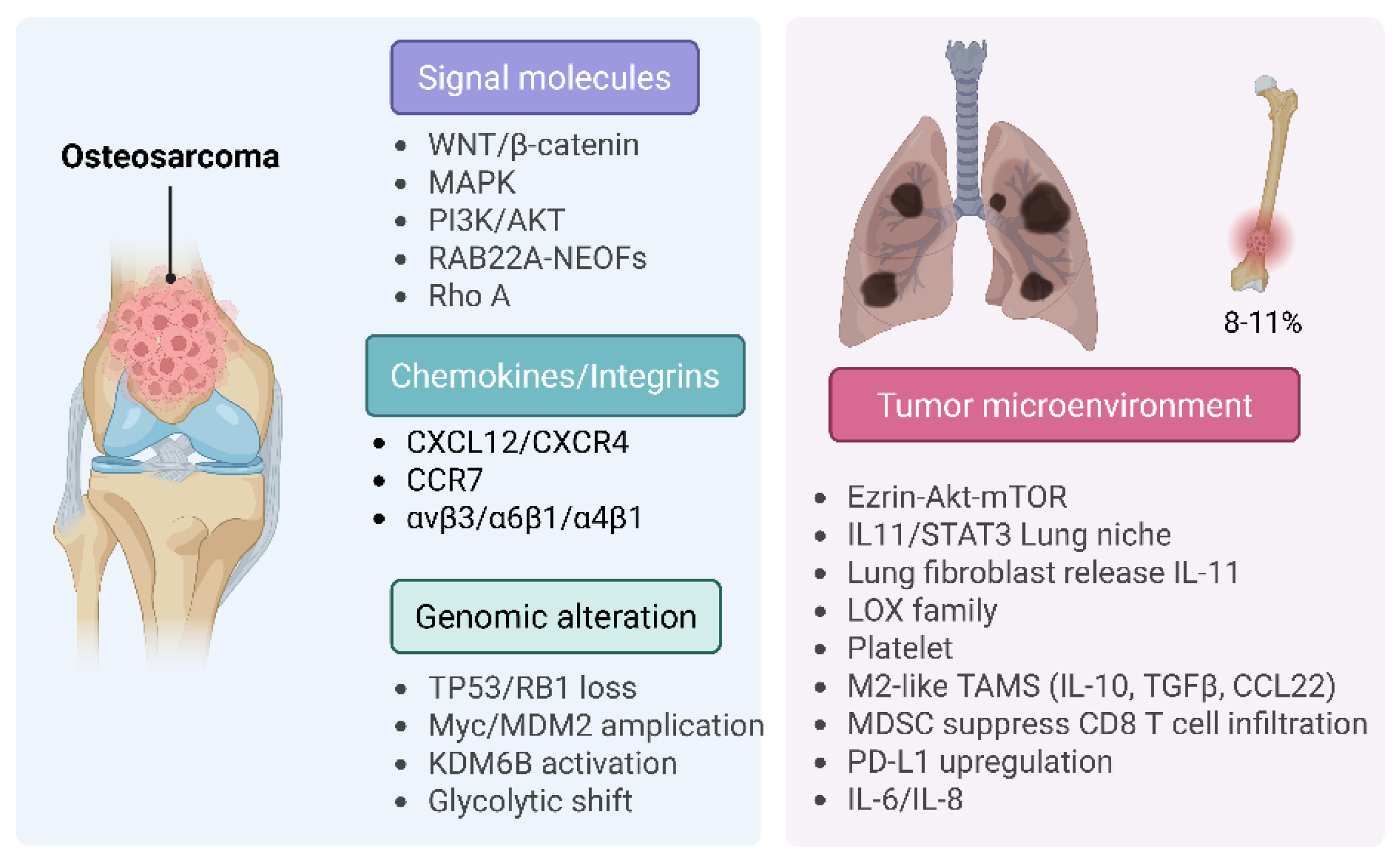

8.1. Osteosarcoma (OS)

8.2. Chondrosarcoma (CS)

8.3. Liposarcoma (LPS)

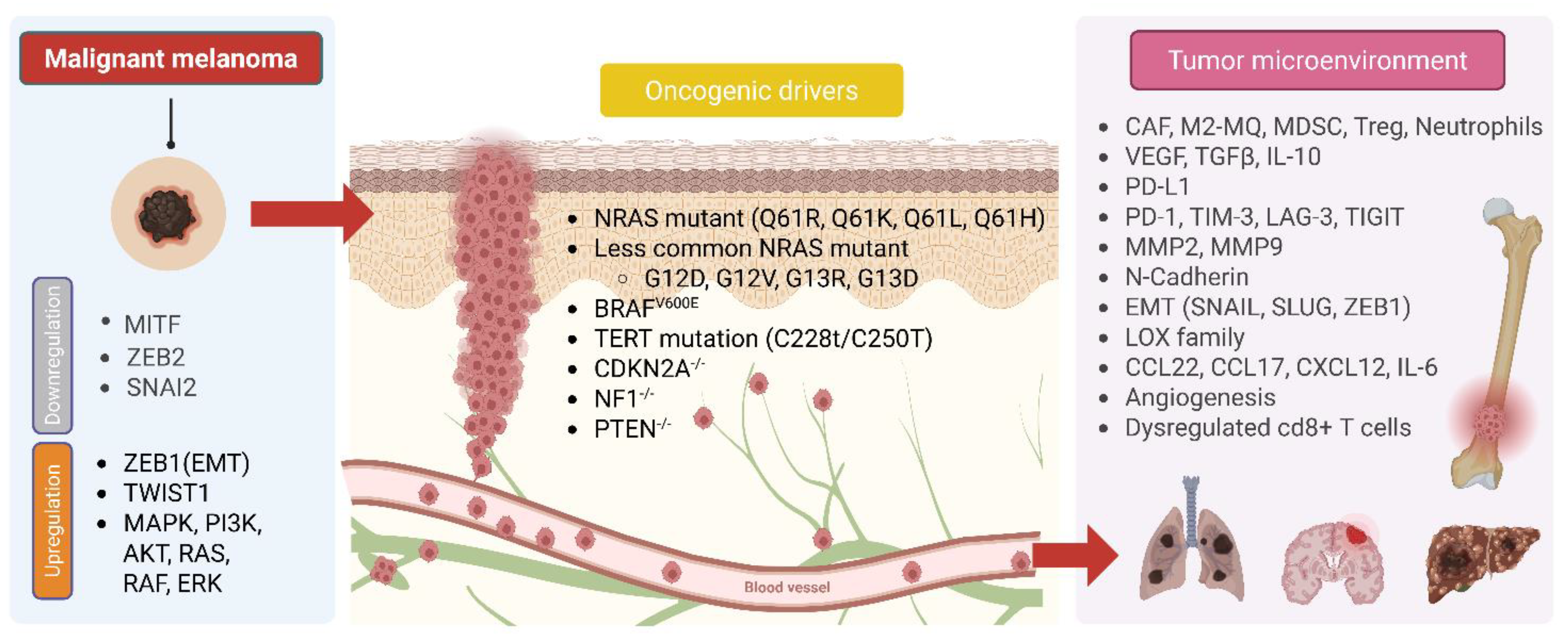

8.4. Melanoma

8.5. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

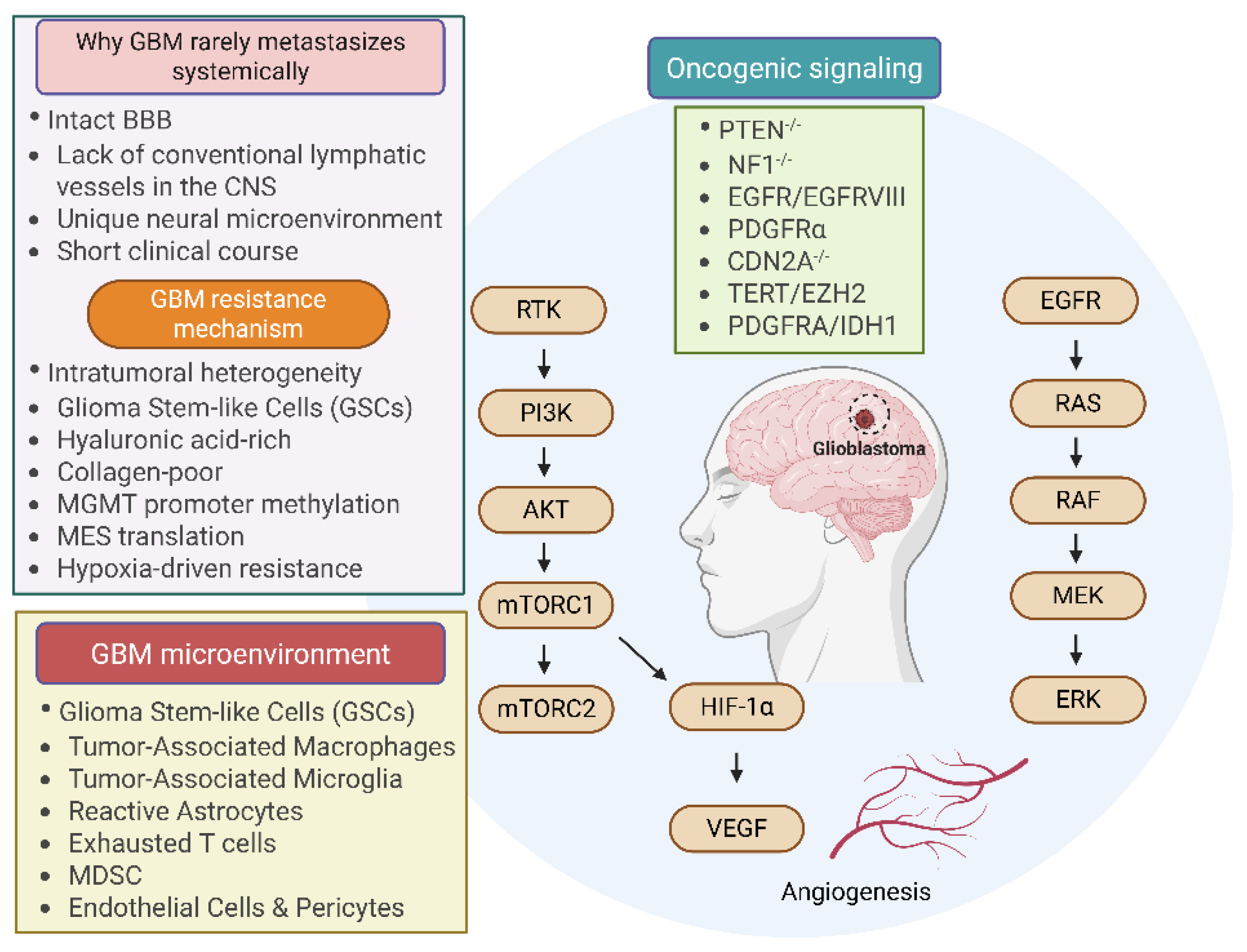

8.6. Glioblastoma (GBM)

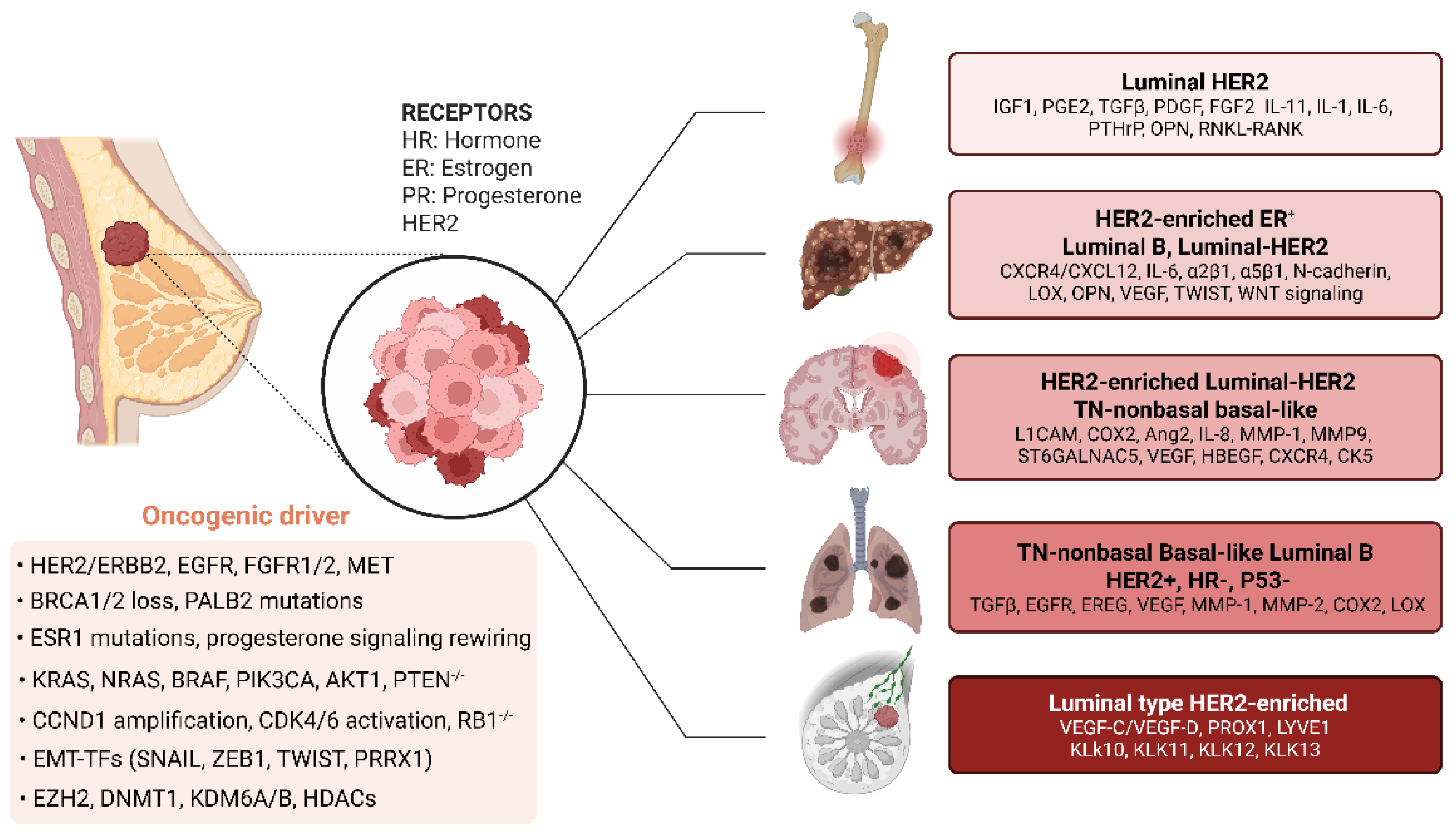

8.7. Breast Tumor

9. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for Metastatic Disease

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):453-8. PubMed PMID: 12778135. [CrossRef]

- Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1423-37. PubMed PMID: 24202395; PMCID: PMC3954707. [CrossRef]

- Yates LR, Gerstung M, Knappskog S, Desmedt C, Gundem G, Van Loo P, Aas T, Alexandrov LB, Larsimont D, Davies H, Li Y, Ju YS, Ramakrishna M, Haugland HK, Lilleng PK, Nik-Zainal S, McLaren S, Butler A, Martin S, Glodzik D, Menzies A, Raine K, Hinton J, Jones D, Mudie LJ, Jiang B, Vincent D, Greene-Colozzi A, Adnet PY, Fatima A, Maetens M, Ignatiadis M, Stratton MR, Sotiriou C, Richardson AL, Lonning PE, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ. Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):751-9. Epub 20150622. PubMed PMID: 26099045; PMCID: PMC4500826. [CrossRef]

- Turajlic S, Swanton C. Metastasis as an evolutionary process. Science. 2016;352(6282):169-75. PubMed PMID: 27124450. [CrossRef]

- Lawson DA, Bhakta NR, Kessenbrock K, Prummel KD, Yu Y, Takai K, Zhou A, Eyob H, Balakrishnan S, Wang CY, Yaswen P, Goga A, Werb Z. Single-cell analysis reveals a stem-cell program in human metastatic breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;526(7571):131-5. Epub 20150923. PubMed PMID: 26416748; PMCID: PMC4648562. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Models, mechanisms and clinical evidence for cancer dormancy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(11):834-46. PubMed PMID: 17957189; PMCID: PMC2519109. [CrossRef]

- Manjili MH. Tumor Dormancy and Relapse: From a Natural Byproduct of Evolution to a Disease State. Cancer Res. 2017;77(10):2564-9. PubMed PMID: 28507050; PMCID: PMC5459601. [CrossRef]

- Sosa MS, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Mechanisms of disseminated cancer cell dormancy: an awakening field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(9):611-22. Epub 20140814. PubMed PMID: 25118602; PMCID: PMC4230700. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh S, Werner C, Fratzl P, Cipitria A. Microenvironment-mediated cancer dormancy: Insights from metastability theory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(1). PubMed PMID: 34949715; PMCID: PMC8740765. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini H, Obradovic MMS, Hoffmann M, Harper KL, Sosa MS, Werner-Klein M, Nanduri LK, Werno C, Ehrl C, Maneck M, Patwary N, Haunschild G, Guzvic M, Reimelt C, Grauvogl M, Eichner N, Weber F, Hartkopf AD, Taran FA, Brucker SY, Fehm T, Rack B, Buchholz S, Spang R, Meister G, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Klein CA. Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;540(7634):552-8. Epub 20161214. PubMed PMID: 27974799; PMCID: PMC5390864. [CrossRef]

- Cristiano S, Leal A, Phallen J, Fiksel J, Adleff V, Bruhm DC, Jensen SO, Medina JE, Hruban C, White JR, Palsgrove DN, Niknafs N, Anagnostou V, Forde P, Naidoo J, Marrone K, Brahmer J, Woodward BD, Husain H, van Rooijen KL, Orntoft MW, Madsen AH, van de Velde CJH, Verheij M, Cats A, Punt CJA, Vink GR, van Grieken NCT, Koopman M, Fijneman RJA, Johansen JS, Nielsen HJ, Meijer GA, Andersen CL, Scharpf RB, Velculescu VE. Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature. 2019;570(7761):385-9. Epub 20190529. PubMed PMID: 31142840; PMCID: PMC6774252. [CrossRef]

- Paez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Vinals F, Inoue M, Bergers G, Hanahan D, Casanovas O. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(3):220-31. PubMed PMID: 19249680; PMCID: PMC2874829. [CrossRef]

- Hotz B, Arndt M, Dullat S, Bhargava S, Buhr HJ, Hotz HG. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: expression of the regulators snail, slug, and twist in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(16):4769-76. PubMed PMID: 17699854. [CrossRef]

- Onder TT, Gupta PB, Mani SA, Yang J, Lander ES, Weinberg RA. Loss of E-cadherin promotes metastasis via multiple downstream transcriptional pathways. Cancer Res. 2008;68(10):3645-54. PubMed PMID: 18483246. [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR, Laklai H, Sugimoto H, Kahlert C, Novitskiy SV, De Jesus-Acosta A, Sharma P, Heidari P, Mahmood U, Chin L, Moses HL, Weaver VM, Maitra A, Allison JP, LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. Depletion of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis Induces Immunosuppression and Accelerates Pancreas Cancer with Reduced Survival. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(6):831-3. Epub 20151214. PubMed PMID: 28843279. [CrossRef]

- Come C, Magnino F, Bibeau F, De Santa Barbara P, Becker KF, Theillet C, Savagner P. Snail and slug play distinct roles during breast carcinoma progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(18):5395-402. PubMed PMID: 17000672. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher JL, Shibue T, Tischler V, Reinhardt F, Itzkovitz S, Noske A, Zurrer-Hardi U, Bell G, Tam WL, Mani SA, van Oudenaarden A, Weinberg RA. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148(5):1015-28. PubMed PMID: 22385965; PMCID: PMC3305806. [CrossRef]

- Shih JY, Yang PC. The EMT regulator slug and lung carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(9):1299-304. Epub 20110610. PubMed PMID: 21665887. [CrossRef]

- Katoh M, Katoh M. Comparative genomics on SNAI1, SNAI2, and SNAI3 orthologs. Oncol Rep. 2005;14(4):1083-6. PubMed PMID: 16142376.

- Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S, Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A, Weinberg RA. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117(7):927-39. PubMed PMID: 15210113. [CrossRef]

- Eckert MA, Lwin TM, Chang AT, Kim J, Danis E, Ohno-Machado L, Yang J. Twist1-induced invadopodia formation promotes tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(3):372-86. PubMed PMID: 21397860; PMCID: PMC3072410. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Zhong L, Li Y, Xiao D, Zhang R, Liao D, Lv D, Wang X, Wang J, Xie X, Chen J, Wu Y, Kang T. Up-regulation of PCOLCE by TWIST1 promotes metastasis in Osteosarcoma. Theranostics. 2019;9(15):4342-53. Epub 20190609. PubMed PMID: 31285765; PMCID: PMC6599655. [CrossRef]

- Fang X, Cai Y, Liu J, Wang Z, Wu Q, Zhang Z, Yang CJ, Yuan L, Ouyang G. Twist2 contributes to breast cancer progression by promoting an epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem-like cell self-renewal. Oncogene. 2011;30(47):4707-20. Epub 20110523. PubMed PMID: 21602879. [CrossRef]

- Gasparotto D, Polesel J, Marzotto A, Colladel R, Piccinin S, Modena P, Grizzo A, Sulfaro S, Serraino D, Barzan L, Doglioni C, Maestro R. Overexpression of TWIST2 correlates with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oncotarget. 2011;2(12):1165-75. PubMed PMID: 22201613; PMCID: PMC3282075. [CrossRef]

- Safe S, Abdelrahim M. Sp transcription factor family and its role in cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(16):2438-48. Epub 20051004. PubMed PMID: 16209919. [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahim M, Smith R, 3rd, Burghardt R, Safe S. Role of Sp proteins in regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(18):6740-9. PubMed PMID: 15374992. [CrossRef]

- Beishline K, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and the ‘hallmarks of cancer’. FEBS J. 2015;282(2):224-58. Epub 20150108. PubMed PMID: 25393971. [CrossRef]

- Sun X, Xiao C, Wang X, Wu S, Yang Z, Sui B, Song Y. Role of post-translational modifications of Sp1 in cancer: state of the art. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1412461. Epub 20240820. PubMed PMID: 39228402; PMCID: PMC11368732. [CrossRef]

- Deniaud E, Baguet J, Mathieu AL, Pages G, Marvel J, Leverrier Y. Overexpression of Sp1 transcription factor induces apoptosis. Oncogene. 2006;25(53):7096-105. Epub 20060522. PubMed PMID: 16715126. [CrossRef]

- Kim KH, Roberts CW. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):128-34. PubMed PMID: 26845405; PMCID: PMC4918227. [CrossRef]

- Zheng M, Jiang YP, Chen W, Li KD, Liu X, Gao SY, Feng H, Wang SS, Jiang J, Ma XR, Cen X, Tang YJ, Chen Y, Lin YF, Tang YL, Liang XH. Snail and Slug collaborate on EMT and tumor metastasis through miR-101-mediated EZH2 axis in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(9):6797-810. PubMed PMID: 25762643; PMCID: PMC4466650. [CrossRef]

- Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419(6907):624-9. PubMed PMID: 12374981. [CrossRef]

- Chang CJ, Yang JY, Xia W, Chen CT, Xie X, Chao CH, Woodward WA, Hsu JM, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC. EZH2 promotes expansion of breast tumor initiating cells through activation of RAF1-beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):86-100. Epub 20110106. PubMed PMID: 21215703; PMCID: PMC3041516. [CrossRef]

- Gong S, Wu C, Duan Y, Tang J, Wu P. A Comprehensive Pan-Cancer Analysis for Pituitary Tumor-Transforming Gene 1. Front Genet. 2022;13:843579. Epub 20220225. PubMed PMID: 35281830; PMCID: PMC8916819. [CrossRef]

- Altieri DC. Survivin, cancer networks and pathway-directed drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(1):61-70. PubMed PMID: 18075512. [CrossRef]

- Lasham A, Print CG, Woolley AG, Dunn SE, Braithwaite AW. YB-1: oncoprotein, prognostic marker and therapeutic target? Biochem J. 2013;449(1):11-23. PubMed PMID: 23216250. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JL, Pillai S, Pernazza D, Sebti SM, Lawrence NJ, Chellappan SP. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase genes by E2F transcription factors: Rb-Raf-1 interaction as a novel target for metastatic disease. Cancer Res. 2012;72(2):516-26. Epub 20111115. PubMed PMID: 22086850; PMCID: PMC3261351. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(7):523-34. PubMed PMID: 18574464. [CrossRef]

- Kim DJ. The Role of the DNA Methyltransferase Family and the Therapeutic Potential of DNMT Inhibitors in Tumor Treatment. Curr Oncol. 2025;32(2). Epub 20250205. PubMed PMID: 39996888; PMCID: PMC11854558. [CrossRef]

- Casalino L, Verde P. Multifaceted Roles of DNA Methylation in Neoplastic Transformation, from Tumor Suppressors to EMT and Metastasis. Genes (Basel). 2020;11(8). Epub 20200812. PubMed PMID: 32806509; PMCID: PMC7463745. [CrossRef]

- Wozniak M, Czyz M. Exploring oncogenic roles and clinical significance of EZH2: focus on non-canonical activities. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2025;17:17588359241306026. Epub 20250107. PubMed PMID: 39776536; PMCID: PMC11705335. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Ye D, Guo W, Yu W, He Y, Hu J, Wang Y, Zhang L, Liao Y, Song H, Zhong S, Xu D, Yin H, Sun B, Wang X, Liu J, Wu Y, Zhou BP, Zhang Z, Deng J. G9a is essential for EMT-mediated metastasis and maintenance of cancer stem cell-like characters in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(9):6887-901. PubMed PMID: 25749385; PMCID: PMC4466657. [CrossRef]

- Tan T, Shi P, Abbas MN, Wang Y, Xu J, Chen Y, Cui H. Epigenetic modification regulates tumor progression and metastasis through EMT (Review). Int J Oncol. 2022;60(6). Epub 20220421. PubMed PMID: 35445731; PMCID: PMC9084613. [CrossRef]

- Iyer NG, Ozdag H, Caldas C. p300/CBP and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4225-31. PubMed PMID: 15156177. [CrossRef]

- Weichert W. HDAC expression and clinical prognosis in human malignancies. Cancer Lett. 2009;280(2):168-76. Epub 20081221. PubMed PMID: 19103471. [CrossRef]

- Kroesen M, Gielen P, Brok IC, Armandari I, Hoogerbrugge PM, Adema GJ. HDAC inhibitors and immunotherapy; a double edged sword? Oncotarget. 2014;5(16):6558-72. PubMed PMID: 25115382; PMCID: PMC4196144. [CrossRef]

- Alver BH, Kim KH, Lu P, Wang X, Manchester HE, Wang W, Haswell JR, Park PJ, Roberts CW. The SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex is required for maintenance of lineage specific enhancers. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14648. Epub 20170306. PubMed PMID: 28262751; PMCID: PMC5343482. [CrossRef]

- Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, Wang Y, Brzoska P, Kong B, Li R, West RB, van de Vijver MJ, Sukumar S, Chang HY. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1071-6. PubMed PMID: 20393566; PMCID: PMC3049919. [CrossRef]

- Italiano A, Soria JC, Toulmonde M, Michot JM, Lucchesi C, Varga A, Coindre JM, Blakemore SJ, Clawson A, Suttle B, McDonald AA, Woodruff M, Ribich S, Hedrick E, Keilhack H, Thomson B, Owa T, Copeland RA, Ho PTC, Ribrag V. Tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):649-59. Epub 20180409. PubMed PMID: 29650362. [CrossRef]

- Chen IC, Sethy B, Liou JP. Recent Update of HDAC Inhibitors in Lymphoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:576391. Epub 20200903. PubMed PMID: 33015069; PMCID: PMC7494784. [CrossRef]

- Alba-Castellon L, Olivera-Salguero R, Mestre-Farrera A, Pena R, Herrera M, Bonilla F, Casal JI, Baulida J, Pena C, Garcia de Herreros A. Snail1-Dependent Activation of Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Controls Epithelial Tumor Cell Invasion and Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016;76(21):6205-17. Epub 20160808. PubMed PMID: 27503928. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Cui P, Deng Y, Zhang B, Gao Z, Li T, Yin Y, Li J. Function of SP1 in tumors and focused treatment approaches for immune evasion (Review). Oncol Lett. 2025;30(4):483. Epub 20250814. PubMed PMID: 40861097; PMCID: PMC12373422. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Gan K, Liu K, Xu B, Chen M. SP1 Expression and the Clinicopathological Features of Tumors: A Meta-Analysis and Bioinformatics Analysis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2021;27:581998. Epub 20210128. PubMed PMID: 34257529; PMCID: PMC8262197. [CrossRef]

- Wu X, Tao P, Zhou Q, Li J, Yu Z, Wang X, Li J, Li C, Yan M, Zhu Z, Liu B, Su L. IL-6 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of gastric cancer via JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8(13):20741-50. PubMed PMID: 28186964; PMCID: PMC5400541. [CrossRef]

- Huang B, Lang X, Li X. The role of IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in cancers. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1023177. Epub 20221216. PubMed PMID: 36591515; PMCID: PMC9800921. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Li A, Tian Y, Wu JD, Liu Y, Li T, Chen Y, Han X, Wu K. The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 pathways in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;31:61-71. Epub 20160825. PubMed PMID: 27578214; PMCID: PMC6142815. [CrossRef]

- Xiong X, Liao X, Qiu S, Xu H, Zhang S, Wang S, Ai J, Yang L. CXCL8 in Tumor Biology and Its Implications for Clinical Translation. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:723846. Epub 20220315. PubMed PMID: 35372515; PMCID: PMC8965068. [CrossRef]

- Yan M, Zheng M, Niu R, Yang X, Tian S, Fan L, Li Y, Zhang S. Roles of tumor-associated neutrophils in tumor metastasis and its clinical applications. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:938289. Epub 20220817. PubMed PMID: 36060811; PMCID: PMC9428510. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C, Gao Y, Ding P, Wu T, Ji G. The role of CXCL family members in different diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):212. Epub 20230701. PubMed PMID: 37393391; PMCID: PMC10314943. [CrossRef]

- Domanska UM, Kruizinga RC, Nagengast WB, Timmer-Bosscha H, Huls G, de Vries EG, Walenkamp AM. A review on CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in oncology: no place to hide. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(1):219-30. Epub 20120609. PubMed PMID: 22683307. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee S, Behnam Azad B, Nimmagadda S. The intricate role of CXCR4 in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;124:31-82. PubMed PMID: 25287686; PMCID: PMC4322894. [CrossRef]

- Augoff K, Hryniewicz-Jankowska A, Tabola R, Stach K. MMP9: A Tough Target for Targeted Therapy for Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(7). Epub 20220406. PubMed PMID: 35406619; PMCID: PMC8998077. [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Fabian S, Arreola R, Becerril-Villanueva E, Torres-Romero JC, Arana-Argaez V, Lara-Riegos J, Ramirez-Camacho MA, Alvarez-Sanchez ME. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Angiogenesis and Cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1370. Epub 20191206. PubMed PMID: 31921634; PMCID: PMC6915110. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Avila G, Sommer B, Mendoza-Posada DA, Ramos C, Garcia-Hernandez AA, Falfan-Valencia R. Matrix metalloproteinases participation in the metastatic process and their diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;137:57-83. Epub 20190303. PubMed PMID: 31014516. [CrossRef]

- Foley CJ, Luo C, O’Callaghan K, Hinds PW, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Matrix metalloprotease-1a promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(29):24330-8. Epub 20120509. PubMed PMID: 22573325; PMCID: PMC3397859. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Xu C, Wang R, Tang Q, Zhou Q, Wu W, Wan X, Mo H, Pan J, Wang S. Treating human cancer by targeting EZH2. Genes Dis. 2025;12(3):101313. Epub 20240425. PubMed PMID: 40028035; PMCID: PMC11870178. [CrossRef]

- Mortezaee K. CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in the microenvironment of solid tumors: A critical mediator of metastasis. Life Sci. 2020;249:117534. Epub 20200307. PubMed PMID: 32156548. [CrossRef]

- Raychaudhuri P, Park HJ. FoxM1: a master regulator of tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4329-33. Epub 20110628. PubMed PMID: 21712406; PMCID: PMC3129416. [CrossRef]

- Liao GB, Li XZ, Zeng S, Liu C, Yang SM, Yang L, Hu CJ, Bai JY. Regulation of the master regulator FOXM1 in cancer. Cell Commun Signal. 2018;16(1):57. Epub 20180912. PubMed PMID: 30208972; PMCID: PMC6134757. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Hong W, Wei X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):129. Epub 20220908. PubMed PMID: 36076302; PMCID: PMC9461252. [CrossRef]

- Anand S, Vikramdeo KS, Sudan SK, Sharma A, Acharya S, Khan MA, Singh S, Singh AP. From modulation of cellular plasticity to potentiation of therapeutic resistance: new and emerging roles of MYB transcription factors in human malignancies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024;43(1):409-21. Epub 20231110. PubMed PMID: 37950087; PMCID: PMC11015973. [CrossRef]

- Yoon CH, Kim MJ, Lee H, Kim RK, Lim EJ, Yoo KC, Lee GH, Cui YH, Oh YS, Gye MC, Lee YY, Park IC, An S, Hwang SG, Park MJ, Suh Y, Lee SJ. PTTG1 oncogene promotes tumor malignancy via epithelial to mesenchymal transition and expansion of cancer stem cell population. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19516-27. Epub 20120416. PubMed PMID: 22511756; PMCID: PMC3365988. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Zeng W, Zheng D, Tang M, Zhou W. Clinical significance of securin expression in solid cancers: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis of published studies and bioinformatics analysis based on TCGA dataset. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(37):e30440. PubMed PMID: 36123907; PMCID: PMC9478268. [CrossRef]

- Alkrekshi A, Wang W, Rana PS, Markovic V, Sossey-Alaoui K. A comprehensive review of the functions of YB-1 in cancer stemness, metastasis and drug resistance. Cell Signal. 2021;85:110073. Epub 20210703. PubMed PMID: 34224843; PMCID: PMC8878385. [CrossRef]

- D’Costa NM, Lowerison MR, Raven PA, Tan Z, Roberts ME, Shrestha R, Urban MW, Monjaras-Avila CU, Oo HZ, Hurtado-Coll A, Chavez-Munoz C, So AI. Y-box binding protein-1 is crucial in acquired drug resistance development in metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):33. Epub 20200210. PubMed PMID: 32041631; PMCID: PMC7011538. [CrossRef]

- Faldt Beding A, Larsson P, Helou K, Einbeigi Z, Parris TZ. Pan-cancer analysis identifies BIRC5 as a prognostic biomarker. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):322. Epub 20220325. PubMed PMID: 35331169; PMCID: PMC8953143. [CrossRef]

- Siragusa G, Tomasello L, Giordano C, Pizzolanti G. Survivin (BIRC5): Implications in cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2024;350:122788. Epub 20240605. PubMed PMID: 38848940. [CrossRef]

- Lin J, Zhang P, Liu W, Liu G, Zhang J, Yan M, Duan Y, Yang N. A positive feedback loop between ZEB2 and ACSL4 regulates lipid metabolism to promote breast cancer metastasis. Elife. 2023;12. Epub 20231211. PubMed PMID: 38078907; PMCID: PMC10712958. [CrossRef]

- Parfenyev SE, Daks AA, Shuvalov OY, Fedorova OA, Pestov NB, Korneenko TV, Barlev NA. Dualistic role of ZEB1 and ZEB2 in tumor progression. Biol Direct. 2025;20(1):32. Epub 20250320. PubMed PMID: 40114235; PMCID: PMC11927373. [CrossRef]

- McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1159-69. PubMed PMID: 16775176. [CrossRef]

- Hebert JD, Myers SA, Naba A, Abbruzzese G, Lamar JM, Carr SA, Hynes RO. Proteomic Profiling of the ECM of Xenograft Breast Cancer Metastases in Different Organs Reveals Distinct Metastatic Niches. Cancer Res. 2020;80(7):1475-85. Epub 20200204. PubMed PMID: 32019869; PMCID: PMC7127975. [CrossRef]

- Fang S, Dai Y, Mei Y, Yang M, Hu L, Yang H, Guan X, Li J. Clinical significance and biological role of cancer-derived Type I collagen in lung and esophageal cancers. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10(2):277-88. Epub 20190103. PubMed PMID: 30604926; PMCID: PMC6360244. [CrossRef]

- Fogg KC, Renner CM, Christian H, Walker A, Marty-Santos L, Khan A, Olson WR, Parent C, O’Shea A, Wellik DM, Weisman PS, Kreeger PK. Ovarian Cells Have Increased Proliferation in Response to Heparin-Binding Epidermal Growth Factor as Collagen Density Increases. Tissue Eng Part A. 2020;26(13-14):747-58. Epub 20200625. PubMed PMID: 32598229; PMCID: PMC7398436. [CrossRef]

- van ‘t Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, van der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, Schreiber GJ, Kerkhoven RM, Roberts C, Linsley PS, Bernards R, Friend SH. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415(6871):530-6. PubMed PMID: 11823860. [CrossRef]

- Lokeshwar VB, Mirza S, Jordan A. Targeting hyaluronic acid family for cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2014;123:35-65. PubMed PMID: 25081525; PMCID: PMC4791948. [CrossRef]

- Bae YK, Kim A, Kim MK, Choi JE, Kang SH, Lee SJ. Fibronectin expression in carcinoma cells correlates with tumor aggressiveness and poor clinical outcome in patients with invasive breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(10):2028-37. Epub 20130514. PubMed PMID: 23684510. [CrossRef]

- Gudjonsson T, Ronnov-Jessen L, Villadsen R, Rank F, Bissell MJ, Petersen OW. Normal and tumor-derived myoepithelial cells differ in their ability to interact with luminal breast epithelial cells for polarity and basement membrane deposition. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 1):39-50. PubMed PMID: 11801722; PMCID: PMC2933194. [CrossRef]

- Guess CM, Quaranta V. Defining the role of laminin-332 in carcinoma. Matrix Biol. 2009;28(8):445-55. Epub 20090815. PubMed PMID: 19686849; PMCID: PMC2875997. [CrossRef]

- Pearce OMT, Delaine-Smith RM, Maniati E, Nichols S, Wang J, Böhm S, Rajeeve V, Ullah D, Chakravarty P, Jones RR, Montfort A, Dowe T, Gribben J, Jones JL, Kocher HM, Serody JS, Vincent BG, Connelly J, Brenton JD, Chelala C, Cutillas PR, Lockley M, Bessant C, Knight MM, Balkwill FR. Deconstruction of a Metastatic Tumor Microenvironment Reveals a Common Matrix Response in Human Cancers. Cancer Discovery. 2018;8(3):304-19. PubMed PMID: WOS:000426997500021. [CrossRef]

- Gocheva V, Naba A, Bhutkar A, Guardia T, Miller KM, Li CM, Dayton TL, Sanchez-Rivera FJ, Kim-Kiselak C, Jailkhani N, Winslow MM, Del Rosario A, Hynes RO, Jacks T. Quantitative proteomics identify Tenascin-C as a promoter of lung cancer progression and contributor to a signature prognostic of patient survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(28):E5625-E34. Epub 20170626. PubMed PMID: 28652369; PMCID: PMC5514763. [CrossRef]

- Xiao W, Wang S, Zhang R, Sohrabi A, Yu Q, Liu S, Ehsanipour A, Liang J, Bierman RD, Nathanson DA, Seidlits SK. Bioengineered scaffolds for 3D culture demonstrate extracellular matrix-mediated mechanisms of chemotherapy resistance in glioblastoma. Matrix Biol. 2020;85-86:128-46. Epub 20190424. PubMed PMID: 31028838; PMCID: PMC6813884. [CrossRef]

- Vihinen P, Ala-aho R, Kahari VM. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5(3):203-20. PubMed PMID: 15892620. [CrossRef]

- Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Tumour microenvironment - Opinion - Validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(3):227-39. PubMed PMID: WOS:000235591900017. [CrossRef]

- Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K, Tanzawa K, Thorpe P, Itohara S, Werb Z, Hanahan D. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):737-44. PubMed PMID: 11025665; PMCID: PMC2852586. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(9):582-98. PubMed PMID: 27550820. [CrossRef]

- Duffy MJ, Duggan C. The urokinase plasminogen activator system: a rich source of tumour markers for the individualised management of patients with cancer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(7):541-8. PubMed PMID: 15234235. [CrossRef]

- Gocheva V, Joyce JA. Cysteine cathepsins and the cutting edge of cancer invasion. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(1):60-4. Epub 20070106. PubMed PMID: 17245112. [CrossRef]

- Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, Chi JT, Jeffrey SS, Giaccia AJ. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440(7088):1222-6. PubMed PMID: 16642001. [CrossRef]

- Peinado H, Del Carmen Iglesias-de la Cruz M, Olmeda D, Csiszar K, Fong KS, Vega S, Nieto MA, Cano A, Portillo F. A molecular role for lysyl oxidase-like 2 enzyme in snail regulation and tumor progression. EMBO J. 2005;24(19):3446-58. Epub 20050818. PubMed PMID: 16096638; PMCID: PMC1276164. [CrossRef]

- Vlodavsky I, Singh P, Boyango I, Gutter-Kapon L, Elkin M, Sanderson RD, Ilan N. Heparanase: From basic research to therapeutic applications in cancer and inflammation. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;29:54-75. Epub 20161006. PubMed PMID: 27912844; PMCID: PMC5447241. [CrossRef]

- Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Hedrick CC, Vonderheide RH, Pittet MJ, Jain RK, Zou W, Howcroft TK, Woodhouse EC, Weinberg RA, Krummel MF. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):541-50. Epub 20180423. PubMed PMID: 29686425; PMCID: PMC5998822. [CrossRef]

- Schumacher D, Strilic B, Sivaraj KK, Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Platelet-derived nucleotides promote tumor-cell transendothelial migration and metastasis via P2Y2 receptor. Cancer Cell. 2013;24(1):130-7. Epub 20130627. PubMed PMID: 23810565. [CrossRef]

- Berghoff AS, Venur VA, Preusser M, Ahluwalia MS. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Brain Metastases: From Biology to Treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e116-22. PubMed PMID: 27249713. [CrossRef]

- Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):418-29. PubMed PMID: 22439937; PMCID: PMC3371414. [CrossRef]

- Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, Verastegui E, Zlotnik A. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410(6824):50-6. PubMed PMID: 11242036. [CrossRef]

- Cabioglu N, Yazici MS, Arun B, Broglio KR, Hortobagyi GN, Price JE, Sahin A. CCR7 and CXCR4 as novel biomarkers predicting axillary lymph node metastasis in T1 breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5686-93. PubMed PMID: 16115904. [CrossRef]

- Xu B, Deng C, Wu X, Ji T, Zhao L, Han Y, Yang W, Qi Y, Wang Z, Yang Z, Yang Y. CCR9 and CCL25: A review of their roles in tumor promotion. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(12):9121-32. Epub 20200513. PubMed PMID: 32401349. [CrossRef]

- Mitsui E, Kikuchi S, Okura T, Tazawa H, Une Y, Nishiwaki N, Kuroda S, Noma K, Kagawa S, Ohara T, Ohtsuka J, Ohki R, Fujiwara T. Novel treatment strategy targeting interleukin-6 induced by cancer associated fibroblasts for peritoneal metastasis of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):3267. Epub 20250125. PubMed PMID: 39863722; PMCID: PMC11762302. [CrossRef]

- Han YP, Tuan TL, Wu H, Hughes M, Garner WL. TNF-alpha stimulates activation of pro-MMP2 in human skin through NF-(kappa)B mediated induction of MT1-MMP. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 1):131-9. PubMed PMID: 11112697; PMCID: PMC2435089. [CrossRef]

- Colak S, Ten Dijke P. Targeting TGF-beta Signaling in Cancer. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(1):56-71. Epub 20170103. PubMed PMID: 28718426. [CrossRef]

- Waugh DJ, Wilson C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(21):6735-41. PubMed PMID: 18980965. [CrossRef]

- Eisenblaetter M, Flores-Borja F, Lee JJ, Wefers C, Smith H, Hueting R, Cooper MS, Blower PJ, Patel D, Rodriguez-Justo M, Milewicz H, Vogl T, Roth J, Tutt A, Schaeffter T, Ng T. Visualization of Tumor-Immune Interaction - Target-Specific Imaging of S100A8/A9 Reveals Pre-Metastatic Niche Establishment. Theranostics. 2017;7(9):2392-401. PubMed PMID: WOS:000403704900004. [CrossRef]

- Steeg PS. Targeting metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(4):201-18. PubMed PMID: 27009393; PMCID: PMC7055530. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438(7069):820-7. PubMed PMID: 16341007; PMCID: PMC2945882. [CrossRef]

- Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Cox TR, Lang G, Bird D, Koong A, Le QT, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxia-induced lysyl oxidase is a critical mediator of bone marrow cell recruitment to form the premetastatic niche. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(1):35-44. PubMed PMID: 19111879; PMCID: PMC3050620. [CrossRef]

- Peinado H, Zhang H, Matei IR, Costa-Silva B, Hoshino A, Rodrigues G, Psaila B, Kaplan RN, Bromberg JF, Kang Y, Bissell MJ, Cox TR, Giaccia AJ, Erler JT, Hiratsuka S, Ghajar CM, Lyden D. Pre-metastatic niches: organ-specific homes for metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(5):302-17. Epub 20170317. PubMed PMID: 28303905. [CrossRef]

- Grant G, Ferrer CM. The role of the immune tumor microenvironment in shaping metastatic dissemination, dormancy, and outgrowth. Trends Cell Biol. 2025. Epub 20250704. PubMed PMID: 40628544. [CrossRef]

- Endo H, Okuyama H, Ohue M, Inoue M. Dormancy of cancer cells with suppression of AKT activity contributes to survival in chronic hypoxia. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98858. Epub 20140606. PubMed PMID: 24905002; PMCID: PMC4048292. [CrossRef]

- Pouyssegur J, Dayan F, Mazure NM. Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature. 2006;441(7092):437-43. PubMed PMID: 16724055. [CrossRef]

- Inoue M, Hager JH, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Hanahan D. VEGF-A has a critical, nonredundant role in angiogenic switching and pancreatic beta cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(2):193-202. PubMed PMID: 12086877. [CrossRef]

- Takeda T, Okuyama H, Nishizawa Y, Tomita S, Inoue M. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha is necessary for invasive phenotype in Vegf-deleted islet cell tumors. Sci Rep. 2012;2:494. Epub 20120704. PubMed PMID: 22768384; PMCID: PMC3389366. [CrossRef]

- Harada H, Inoue M, Itasaka S, Hirota K, Morinibu A, Shinomiya K, Zeng L, Ou G, Zhu Y, Yoshimura M, McKenna WG, Muschel RJ, Hiraoka M. Cancer cells that survive radiation therapy acquire HIF-1 activity and translocate towards tumour blood vessels. Nat Commun. 2012;3:783. Epub 20120417. PubMed PMID: 22510688; PMCID: PMC3337987. [CrossRef]

- Qannita RA, Alalami AI, Harb AA, Aleidi SM, Taneera J, Abu-Gharbieh E, El-Huneidi W, Saleh MA, Alzoubi KH, Semreen MH, Hudaib M, Bustanji Y. Targeting Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) in Cancer: Emerging Therapeutic Strategies and Pathway Regulation. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(2). Epub 20240201. PubMed PMID: 38399410; PMCID: PMC10892333. [CrossRef]

- Ameri K, Jahangiri A, Rajah AM, Tormos KV, Nagarajan R, Pekmezci M, Nguyen V, Wheeler ML, Murphy MP, Sanders TA, Jeffrey SS, Yeghiazarians Y, Rinaudo PF, Costello JF, Aghi MK, Maltepe E. HIGD1A Regulates Oxygen Consumption, ROS Production, and AMPK Activity during Glucose Deprivation to Modulate Cell Survival and Tumor Growth. Cell Rep. 2015;10(6):891-9. Epub 20150213. PubMed PMID: 25683712; PMCID: PMC4534363. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Estrada Y, Liu D, Ossowski L. ERK(MAPK) activity as a determinant of tumor growth and dormancy; regulation by p38(SAPK). Cancer Res. 2003;63(7):1684-95. PubMed PMID: 12670923.

- Bui T, Gu Y, Ancot F, Sanguin-Gendreau V, Zuo D, Muller WJ. Emergence of beta1 integrin-deficient breast tumours from dormancy involves both inactivation of p53 and generation of a permissive tumour microenvironment. Oncogene. 2022;41(4):527-37. Epub 20211115. PubMed PMID: 34782719; PMCID: PMC8782722. [CrossRef]

- Nam JM, Onodera Y, Bissell MJ, Park CC. Breast cancer cells in three-dimensional culture display an enhanced radioresponse after coordinate targeting of integrin alpha5beta1 and fibronectin. Cancer Res. 2010;70(13):5238-48. Epub 20100601. PubMed PMID: 20516121; PMCID: PMC2933183. [CrossRef]

- Huang T, Sun L, Yuan X, Qiu H. Thrombospondin-1 is a multifaceted player in tumor progression. Oncotarget. 2017;8(48):84546-58. Epub 20170711. PubMed PMID: 29137447; PMCID: PMC5663619. [CrossRef]

- Choi YH, Burdick MD, Strieter BA, Mehrad B, Strieter RM. CXCR4, but not CXCR7, discriminates metastatic behavior in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(1):38-47. Epub 20130911. PubMed PMID: 24025971; PMCID: PMC4262747. [CrossRef]

- Sosa MS, Parikh F, Maia AG, Estrada Y, Bosch A, Bragado P, Ekpin E, George A, Zheng Y, Lam HM, Morrissey C, Chung CY, Farias EF, Bernstein E, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. NR2F1 controls tumour cell dormancy via SOX9- and RARbeta-driven quiescence programmes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6170. Epub 20150130. PubMed PMID: 25636082; PMCID: PMC4313575. [CrossRef]

- Barnieh FM, Morton J, Olanrewaju O, El-Khamisy SF. Decoding the adaptive survival mechanisms of breast cancer dormancy. Oncogene. 2025;44(40):3759-73. Epub 20250827. PubMed PMID: 40866498; PMCID: PMC12477053. [CrossRef]

- Park SL, Buzzai A, Rautela J, Hor JL, Hochheiser K, Effern M, McBain N, Wagner T, Edwards J, McConville R, Wilmott JS, Scolyer RA, Tuting T, Palendira U, Gyorki D, Mueller SN, Huntington ND, Bedoui S, Holzel M, Mackay LK, Waithman J, Gebhardt T. Tissue-resident memory CD8(+) T cells promote melanoma-immune equilibrium in skin. Nature. 2019;565(7739):366-71. Epub 20181231. PubMed PMID: 30598548. [CrossRef]

- Karacz CM, Yan J, Zhu H, Gerber DE. Timing, Sites, and Correlates of Lung Cancer Recurrence. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020;21(2):127-35 e3. Epub 20191220. PubMed PMID: 31932216; PMCID: PMC7061059. [CrossRef]

- Shin JH, Yoo HB, Roe JS. Current advances and future directions in targeting histone demethylases for cancer therapy. Mol Cells. 2025;48(3):100192. Epub 20250210. PubMed PMID: 39938867; PMCID: PMC11889978. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Li N, Xiang R, Sun P. Emerging roles of the p38 MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in oncogene-induced senescence. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(6):268-76. Epub 20140509. PubMed PMID: 24818748; PMCID: PMC4358807. [CrossRef]

- Di Martino JS, Nobre AR, Mondal C, Taha I, Farias EF, Fertig EJ, Naba A, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Bravo-Cordero JJ. A tumor-derived type III collagen-rich ECM niche regulates tumor cell dormancy. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(1):90-107. Epub 20211213. PubMed PMID: 35121989; PMCID: PMC8818089. [CrossRef]

- Fox DB, Garcia NMG, McKinney BJ, Lupo R, Noteware LC, Newcomb R, Liu J, Locasale JW, Hirschey MD, Alvarez JV. NRF2 activation promotes the recurrence of dormant tumour cells through regulation of redox and nucleotide metabolism. Nat Metab. 2020;2(4):318-34. Epub 20200420. PubMed PMID: 32691018; PMCID: PMC7370851. [CrossRef]

- Kaur A, Webster MR, Marchbank K, Behera R, Ndoye A, Kugel CH, 3rd, Dang VM, Appleton J, O’Connell MP, Cheng P, Valiga AA, Morissette R, McDonnell NB, Ferrucci L, Kossenkov AV, Meeth K, Tang HY, Yin X, Wood WH, 3rd, Lehrmann E, Becker KG, Flaherty KT, Frederick DT, Wargo JA, Cooper ZA, Tetzlaff MT, Hudgens C, Aird KM, Zhang R, Xu X, Liu Q, Bartlett E, Karakousis G, Eroglu Z, Lo RS, Chan M, Menzies AM, Long GV, Johnson DB, Sosman J, Schilling B, Schadendorf D, Speicher DW, Bosenberg M, Ribas A, Weeraratna AT. sFRP2 in the aged microenvironment drives melanoma metastasis and therapy resistance. Nature. 2016;532(7598):250-4. Epub 20160404. PubMed PMID: 27042933; PMCID: PMC4833579. [CrossRef]

- Prunier C, Baker D, Ten Dijke P, Ritsma L. TGF-beta Family Signaling Pathways in Cellular Dormancy. Trends Cancer. 2019;5(1):66-78. Epub 20181128. PubMed PMID: 30616757. [CrossRef]

- Kurppa KJ, Liu Y, To C, Zhang T, Fan M, Vajdi A, Knelson EH, Xie Y, Lim K, Cejas P, Portell A, Lizotte PH, Ficarro SB, Li S, Chen T, Haikala HM, Wang H, Bahcall M, Gao Y, Shalhout S, Boettcher S, Shin BH, Thai T, Wilkens MK, Tillgren ML, Mushajiang M, Xu M, Choi J, Bertram AA, Ebert BL, Beroukhim R, Bandopadhayay P, Awad MM, Gokhale PC, Kirschmeier PT, Marto JA, Camargo FD, Haq R, Paweletz CP, Wong KK, Barbie DA, Long HW, Gray NS, Janne PA. Treatment-Induced Tumor Dormancy through YAP-Mediated Transcriptional Reprogramming of the Apoptotic Pathway. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(1):104-22 e12. PubMed PMID: 31935369; PMCID: PMC7146079. [CrossRef]

- Lotter W, Hassett MJ, Schultz N, Kehl KL, Van Allen EM, Cerami E. Artificial Intelligence in Oncology: Current Landscape, Challenges, and Future Directions. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(5):711-26. PubMed PMID: 38597966; PMCID: PMC11131133. [CrossRef]

- Vandekerkhove G, Lavoie JM, Annala M, Murtha AJ, Sundahl N, Walz S, Sano T, Taavitsainen S, Ritch E, Fazli L, Hurtado-Coll A, Wang G, Nykter M, Black PC, Todenhofer T, Ost P, Gibb EA, Chi KN, Eigl BJ, Wyatt AW. Plasma ctDNA is a tumor tissue surrogate and enables clinical-genomic stratification of metastatic bladder cancer. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):184. Epub 20210108. PubMed PMID: 33420073; PMCID: PMC7794518. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Tang L, Peng N, Wang L. Lung and bone metastases patterns in limb osteosarcoma: Surgical treatment of primary site improves overall survival. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(42):e35671. PubMed PMID: 37861481; PMCID: PMC10589517. [CrossRef]

- Silva JAM, Marchiori E, Amorim VB, Barreto MM. CT features of osteosarcoma lung metastasis: a retrospective study of 127 patients. J Bras Pneumol. 2023;49(2):e20220433. Epub 20230428. PubMed PMID: 37132704; PMCID: PMC10171270. [CrossRef]

- Marko TA, Diessner BJ, Spector LG. Prevalence of Metastasis at Diagnosis of Osteosarcoma: An International Comparison. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(6):1006-11. Epub 20160229. PubMed PMID: 26929018; PMCID: PMC4833631. [CrossRef]

- Harris MA, Hawkins CJ. Recent and Ongoing Research into Metastatic Osteosarcoma Treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7). Epub 20220330. PubMed PMID: 35409176; PMCID: PMC8998815. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Wang J, Sun M, Zuo D, Wang H, Shen J, Jiang W, Mu H, Ma X, Yin F, Lin J, Wang C, Yu S, Jiang L, Lv G, Liu F, Xue L, Tian K, Wang G, Zhou Z, Lv Y, Wang Z, Zhang T, Xu J, Yang L, Zhao K, Sun W, Tang Y, Cai Z, Wang S, Hua Y. Multi-omics analysis identifies osteosarcoma subtypes with distinct prognosis indicating stratified treatment. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7207. Epub 20221123. PubMed PMID: 36418292; PMCID: PMC9684515. [CrossRef]

- Beird HC, Wu CC, Nakazawa M, Ingram D, Daniele JR, Lazcano R, Little L, Davies C, Daw NC, Wani K, Wang WL, Song X, Gumbs C, Zhang J, Rubin B, Conley A, Flanagan AM, Lazar AJ, Futreal PA. Complete loss of TP53 and RB1 is associated with complex genome and low immune infiltrate in pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. HGG Adv. 2023;4(4):100224. Epub 20230719. PubMed PMID: 37593416; PMCID: PMC10428123. [CrossRef]

- Zhong L, Liao D, Li J, Liu W, Wang J, Zeng C, Wang X, Cao Z, Zhang R, Li M, Jiang K, Zeng YX, Sui J, Kang T. Rab22a-NeoF1 fusion protein promotes osteosarcoma lung metastasis through its secretion into exosomes. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):59. Epub 20210211. PubMed PMID: 33568623; PMCID: PMC7876000. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Li F, Gao B, Ma M, Chen M, Wu Y, Zhang W, Sun Y, Liu S, Shen H. KDM6B-mediated histone demethylation of LDHA promotes lung metastasis of osteosarcoma. Theranostics. 2021;11(8):3868-81. Epub 20210206. PubMed PMID: 33664867; PMCID: PMC7914357. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Xu Y, Bao Y, Luo Y, Qiu G, He M, Lu J, Xu J, Chen B, Wang Y. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification in osteosarcoma: expression, function and interaction with noncoding RNAs - an updated review. Epigenetics. 2023;18(1):2260213. Epub 20230928. PubMed PMID: 37766615; PMCID: PMC10540650. [CrossRef]

- Feng Z, Ou Y, Hao L. The roles of glycolysis in osteosarcoma. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:950886. Epub 20220817. PubMed PMID: 36059961; PMCID: PMC9428632. [CrossRef]

- Luo ZW, Liu PP, Wang ZX, Chen CY, Xie H. Macrophages in Osteosarcoma Immune Microenvironment: Implications for Immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2020;10:586580. Epub 20201210. PubMed PMID: 33363016; PMCID: PMC7758531. [CrossRef]

- Zhou J, Liu T, Wang W. Prognostic significance of matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression in osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis of 16 studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(44):e13051. PubMed PMID: 30383677; PMCID: PMC6221749. [CrossRef]

- Lucotti S, Muschel RJ. Platelets and Metastasis: New Implications of an Old Interplay. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1350. Epub 20200918. PubMed PMID: 33042789; PMCID: PMC7530207. [CrossRef]

- McAloney CA, Makkawi R, Budhathoki Y, Cannon MV, Franz EM, Gross AC, Cam M, Vetter TA, Duhen R, Davies AE, Roberts RD. Host-derived growth factors drive ERK phosphorylation and MCL1 expression to promote osteosarcoma cell survival during metastatic lung colonization. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2024;47(1):259-82. Epub 20230907. PubMed PMID: 37676378; PMCID: PMC10899530. [CrossRef]

- Du X, Wei H, Zhang B, Wang B, Li Z, Pang LK, Zhao R, Yao W. Molecular mechanisms of osteosarcoma metastasis and possible treatment opportunities. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1117867. Epub 20230501. PubMed PMID: 37197432; PMCID: PMC10183593. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Wang Z, Wu H, Xue M, Lin P, Wang S, Lin N, Huang X, Pan W, Liu M, Yan X, Qu H, Sun L, Li H, Wu Y, Teng W, Wang Z, Zhou X, Chen H, Poznansky MC, Ye Z. Epigenetic Regulation of CXCL12 Plays a Critical Role in Mediating Tumor Progression and the Immune Response In Osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(14):3938-53. Epub 20180507. PubMed PMID: 29735547. [CrossRef]

- Gvozdenovic A, Boro A, Meier D, Bode-Lesniewska B, Born W, Muff R, Fuchs B. Targeting alphavbeta3 and alphavbeta5 integrins inhibits pulmonary metastasis in an intratibial xenograft osteosarcoma mouse model. Oncotarget. 2016;7(34):55141-54. PubMed PMID: 27409827; PMCID: PMC5342407. [CrossRef]

- Grisez BT, Ray JJ, Bostian PA, Markel JE, Lindsey BA. Highly metastatic K7M2 cell line: A novel murine model capable of in vivo imaging via luciferase vector transfection. J Orthop Res. 2018. Epub 20180210. PubMed PMID: 29427436; PMCID: PMC6086764. [CrossRef]

- Berman SD, Calo E, Landman AS, Danielian PS, Miller ES, West JC, Fonhoue BD, Caron A, Bronson R, Bouxsein ML, Mukherjee S, Lees JA. Metastatic osteosarcoma induced by inactivation of Rb and p53 in the osteoblast lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(33):11851-6. Epub 20080812. PubMed PMID: 18697945; PMCID: PMC2575280. [CrossRef]

- Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, Mohiuddin S, Mishra DK, Krishnan S, Velasco AR, Vetter AM, Pence K, McCall D, Truong DD, Cuglievan B, Menegaz BA, Utama B, Daw NC, Molina ER, Zielinski RJ, Livingston JA, Gorlick R, Mikos AG, Kim MP, Ludwig JA. Transcriptional activators YAP/TAZ and AXL orchestrate dedifferentiation, cell fate, and metastasis in human osteosarcoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021;28(12):1325-38. Epub 20210106. PubMed PMID: 33408328; PMCID: PMC8636268. [CrossRef]

- Just MA, Van Mater D, Wagner LM. Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(8):e29084. Epub 20210424. PubMed PMID: 33894051; PMCID: PMC8238849. [CrossRef]

- Bhalla S, Gerber DE. AXL Inhibitors: Status of Clinical Development. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(5):521-9. Epub 20230315. PubMed PMID: 36920638; PMCID: PMC11161200. [CrossRef]

- Nirala BK, Yamamichi T, Yustein JT. Deciphering the Signaling Mechanisms of Osteosarcoma Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14). Epub 20230712. PubMed PMID: 37511127; PMCID: PMC10379831. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Yustein JT, Xu J. Research models and mesenchymal/epithelial plasticity of osteosarcoma. Cell Biosci. 2021;11(1):94. Epub 20210522. PubMed PMID: 34022967; PMCID: PMC8141200. [CrossRef]

- Imamura T. Physiological functions and underlying mechanisms of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family members: recent findings and implications for their pharmacological application. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37(7):1081-9. PubMed PMID: 24988999. [CrossRef]

- Sbaraglia M, Bellan E, Dei Tos AP. The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: news and perspectives. Pathologica. 2021;113(2):70-84. Epub 20201103. PubMed PMID: 33179614; PMCID: PMC8167394. [CrossRef]

- Bovee JV, Hogendoorn PC, Wunder JS, Alman BA. Cartilage tumours and bone development: molecular pathology and possible therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(7):481-8. Epub 20100610. PubMed PMID: 20535132. [CrossRef]

- Amary MF, Bacsi K, Maggiani F, Damato S, Halai D, Berisha F, Pollock R, O’Donnell P, Grigoriadis A, Diss T, Eskandarpour M, Presneau N, Hogendoorn PC, Futreal A, Tirabosco R, Flanagan AM. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent events in central chondrosarcoma and central and periosteal chondromas but not in other mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol. 2011;224(3):334-43. Epub 20110519. PubMed PMID: 21598255. [CrossRef]

- Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, Fantin VR, Jang HG, Jin S, Keenan MC, Marks KM, Prins RM, Ward PS, Yen KE, Liau LM, Rabinowitz JD, Cantley LC, Thompson CB, Vander Heiden MG, Su SM. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2010;465(7300):966. PubMed PMID: 20559394; PMCID: PMC3766976. [CrossRef]

- Evans HL, Ayala AG, Romsdahl MM. Prognostic factors in chondrosarcoma of bone: a clinicopathologic analysis with emphasis on histologic grading. Cancer. 1977;40(2):818-31. PubMed PMID: 890662. [CrossRef]

- Ingangi V, De Chiara A, Ferrara G, Gallo M, Catapano A, Fazioli F, Di Carluccio G, Peranzoni E, Marigo I, Carriero MV, Minopoli M. Emerging Treatments Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment for Advanced Chondrosarcoma. Cells. 2024;13(11). Epub 20240604. PubMed PMID: 38891109; PMCID: PMC11171855. [CrossRef]

- Syrjanen KJ. Spontaneous evolution of intraepithelial lesions according to the grade and type of the implicated human papillomavirus (HPV). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65(1):45-53. PubMed PMID: 8706956. [CrossRef]

- A S, Kani V, Vasudevan S, Esakki M. Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcoma: A Report of a Rare and Intriguing Case. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e68452. Epub 20240902. PubMed PMID: 39360119; PMCID: PMC11446496. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Lou S, Yao T. Trends in primary malignant bone cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 2000-2017: A population-based study. J Bone Oncol. 2024;46:100607. Epub 20240511. PubMed PMID: 38778835; PMCID: PMC11109025. [CrossRef]

- van Praag Veroniek VM, Rueten-Budde AJ, Ho V, Dijkstra PDS, Study group B, Soft tissue t, Fiocco M, van de Sande MAJ. Incidence, outcomes and prognostic factors during 25 years of treatment of chondrosarcomas. Surg Oncol. 2018;27(3):402-8. Epub 20180506. PubMed PMID: 30217294. [CrossRef]

- Nicolle R, Ayadi M, Gomez-Brouchet A, Armenoult L, Banneau G, Elarouci N, Tallegas M, Decouvelaere AV, Aubert S, Redini F, Marie B, Labit-Bouvier C, Reina N, Karanian M, le Nail LR, Anract P, Gouin F, Larousserie F, de Reynies A, de Pinieux G. Integrated molecular characterization of chondrosarcoma reveals critical determinants of disease progression. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4622. Epub 20191011. PubMed PMID: 31604924; PMCID: PMC6789144. [CrossRef]

- Campbell VT, Nadesan P, Ali SA, Wang CY, Whetstone H, Poon R, Wei Q, Keilty J, Proctor J, Wang LW, Apte SS, McGovern K, Alman BA, Wunder JS. Hedgehog pathway inhibition in chondrosarcoma using the smoothened inhibitor IPI-926 directly inhibits sarcoma cell growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):1259-69. Epub 20140314. PubMed PMID: 24634412. [CrossRef]

- Walker RL, Hornicek FJ, Duan Z. Advances in the Molecular Biology of Chondrosarcoma for Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(16). Epub 20250819. PubMed PMID: 40867318; PMCID: PMC12385095. [CrossRef]

- Iozzo RV, Sanderson RD. Proteoglycans in cancer biology, tumour microenvironment and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(5):1013-31. PubMed PMID: 21155971; PMCID: PMC3633488. [CrossRef]

- Cui N, Hu M, Khalil RA. Biochemical and Biological Attributes of Matrix Metalloproteinases. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2017;147:1-73. Epub 20170322. PubMed PMID: 28413025; PMCID: PMC5430303. [CrossRef]

- Lau YK, Gobin AM, West JL. Overexpression of lysyl oxidase to increase matrix crosslinking and improve tissue strength in dermal wound healing. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34(8):1239-46. Epub 20060628. PubMed PMID: 16804742. [CrossRef]

- Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139(5):891-906. PubMed PMID: 19931152; PMCID: PMC2788004. [CrossRef]

- Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148(3):399-408. PubMed PMID: 22304911; PMCID: PMC3437543. [CrossRef]

- Hou SM, Lin CY, Fong YC, Tang CH. Hypoxia-regulated exosomes mediate M2 macrophage polarization and promote metastasis in chondrosarcoma. Aging (Albany NY). 2023;15(22):13163-75. Epub 20231121. PubMed PMID: 37993261; PMCID: PMC10713415. [CrossRef]

- Cammarota F, Laukkanen MO. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Stromal Evolution and Cancer Progression. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:4824573. Epub 20151221. PubMed PMID: 26798356; PMCID: PMC4699086. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhou F, ten Dijke P. Signaling interplay between transforming growth factor-beta receptor and PI3K/AKT pathways in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(12):612-20. Epub 20131114. PubMed PMID: 24239264. [CrossRef]

- Meijer DM, Ruano D, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Wijers-Koster PM, van de Sande MAJ, Gelderblom H, Cleton-Jansen AM, de Miranda N, Kuijjer ML, Bovee J. The Variable Genomic Landscape During Osteosarcoma Progression: Insights From a Longitudinal WGS Analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2024;63(7):e23253. PubMed PMID: 39023390. [CrossRef]

- Wada T, Nakashima T, Hiroshi N, Penninger JM. RANKL-RANK signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone disease. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12(1):17-25. Epub 20051213. PubMed PMID: 16356770. [CrossRef]

- Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(10):721-32. PubMed PMID: 13130303. [CrossRef]

- Jones RL, Katz D, Loggers ET, Davidson D, Rodler ET, Pollack SM. Clinical benefit of antiangiogenic therapy in advanced and metastatic chondrosarcoma. Med Oncol. 2017;34(10):167. Epub 20170829. PubMed PMID: 28852958; PMCID: PMC5574947. [CrossRef]

- Su Z, Ho JWK, Yau RCH, Lam YL, Shek TWH, Yeung MCF, Chen H, Oreffo ROC, Cheah KSE, Cheung KSC. A single-cell atlas of conventional central chondrosarcoma reveals the role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in malignant transformation. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):124. Epub 20240124. PubMed PMID: 38267611; PMCID: PMC10808239. [CrossRef]

- Dermawan JKT, Nafa K, Mohanty A, Xu Y, Rijo I, Casanova J, Villafania L, Benhamida J, Kelly CM, Tap WD, Boland PJ, Fabbri N, Healey JH, Ladanyi M, Lu C, Hameed M. Distinct IDH1/2-associated Methylation Profile and Enrichment of TP53 and TERT Mutations Distinguish Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcoma from Conventional Chondrosarcoma. Cancer Res Commun. 2023;3(3):431-43. Epub 20230314. PubMed PMID: 36926116; PMCID: PMC10013202. [CrossRef]

- Lacuna KP, Ingham M, Chen L, Das B, Lee SM, Ge L, Druta M, Conley AP, Keohan ML, Agulnik M, Burgess MA, Chalmers AW, D’Amato GZ, Powers B, Seetharam M, Siontis BL, Pelosof LC, Van Tine BA, Schwartz GK, Weiss MC. Correlative results from NCI CTEP/ETCTN 10330: A phase 2 study of belinostat with SGI-110 (guadecitabine) or ASTX727 (decitabine/cedazuridine) for advanced conventional chondrosarcoma (cCS). J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(16). PubMed PMID: WOS:001275557402684.

- Sheikh TN, Chen X, Xu X, McGuire JT, Ingham M, Lu C, Schwartz GK. Growth Inhibition and Induction of Innate Immune Signaling of Chondrosarcomas with Epigenetic Inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021;20(12):2362-71. Epub 20210922. PubMed PMID: 34552007; PMCID: PMC8643315. [CrossRef]

- Dai W, Qiao X, Fang Y, Guo R, Bai P, Liu S, Li T, Jiang Y, Wei S, Na Z, Xiao X, Li D. Epigenetics-targeted drugs: current paradigms and future challenges. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):332. Epub 20241126. PubMed PMID: 39592582; PMCID: PMC11627502. [CrossRef]

- Oza J, Lee SM, Weiss MC, Siontis BL, Powers BC, Chow WA, Magana W, Sheikh T, Piekarz R, Schwartz GK, Ingham M. A phase 2 study of belinostat and SGI-110 (guadecitabine) for the treatment of unresectable and metastatic conventional chondrosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15). PubMed PMID: WOS:000708120306169. [CrossRef]

- Micaily I, Roche M, Ibrahim MY, Martinez-Outschoorn U, Mallick AB. Metabolic Pathways and Targets in Chondrosarcoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:772263. Epub 20211206. PubMed PMID: 34938658; PMCID: PMC8685273. [CrossRef]

- Bansal A, Goyal S, Goyal A, Jana M. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours 2020: An update and simplified approach for radiologists. Eur J Radiol. 2021;143:109937. Epub 20210828. PubMed PMID: 34547634. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz E, Nessim C. Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Care in 2021. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(5). Epub 20220302. PubMed PMID: 35267600; PMCID: PMC8909774. [CrossRef]

- Engstrom K, Willen H, Kabjorn-Gustafsson C, Andersson C, Olsson M, Goransson M, Jarnum S, Olofsson A, Warnhammar E, Aman P. The myxoid/round cell liposarcoma fusion oncogene FUS-DDIT3 and the normal DDIT3 induce a liposarcoma phenotype in transfected human fibrosarcoma cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(5):1642-53. PubMed PMID: 16651630; PMCID: PMC1606602. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Ren W, Zhou X, Sheng W, Wang J. Pleomorphic liposarcoma: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic study of 32 additional cases. Pathol Int. 2013;63(11):523-31. PubMed PMID: 24274714. [CrossRef]

- Jonczak E, Grossman J, Alessandrino F, Seldon Taswell C, Velez-Torres JM, Trent J. Liposarcoma: A Journey into a Rare Tumor’s Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Limitations of Current Therapies. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(22). Epub 20241118. PubMed PMID: 39594813; PMCID: PMC11592651. [CrossRef]

- Haddox CL, Hornick JL, Roland CL, Baldini EH, Keedy VL, Riedel RF. Diagnosis and management of dedifferentiated liposarcoma: A multidisciplinary position statement. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024;131:102846. Epub 20241018. PubMed PMID: 39454547. [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba B, Wang F, Taher A, Aslam R, Madewell JE, Nassar S. Myxoid Liposarcoma With Skeletal Metastases: Pathophysiology and Imaging Characteristics. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2021;50(1):66-73. Epub 20191030. PubMed PMID: 31813645. [CrossRef]

- Wan L, Tu C, Qi L, Li Z. Survivorship and prognostic factors for pleomorphic liposarcoma: a population-based study. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):175. Epub 20210304. PubMed PMID: 33663547; PMCID: PMC7931523. [CrossRef]

- James J, Yajid AI, Yahaya S, Abdullah S, Sharif SET. Prognostic Implications of and Co-amplification in Liposarcoma: Insights from FISH analysis for Translational Oncology. Clin Transl Oncol. 2025. PubMed PMID: WOS:001529127500001. [CrossRef]

- Hou X, Shi W, Luo W, Luo Y, Huang X, Li J, Ji N, Chen Q. FUS::DDIT3 Fusion Protein in the Development of Myxoid Liposarcoma and Possible Implications for Therapy. Biomolecules. 2024;14(10). Epub 20241014. PubMed PMID: 39456230; PMCID: PMC11506083. [CrossRef]

- Gruel N, Quignot C, Lesage L, El Zein S, Bonvalot S, Tzanis D, Ait Rais K, Quinquis F, Manciot B, Vibert J, El Tannir N, Dahmani A, Derrien H, Decaudin D, Bieche I, Courtois L, Mariani O, Linares LK, Gayte L, Baulande S, Waterfall JJ, Delattre O, Pierron G, Watson S. Cellular origin and clonal evolution of human dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7941. Epub 20240912. PubMed PMID: 39266532; PMCID: PMC11393420. [CrossRef]

- Benesova I, Kalkusova K, Kwon YS, Taborska P, Stakheev D, Krausova K, Smetanova J, Ozaniak A, Bartunkova J, Smrz D, Strizova ZO. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in human malignancies, with a particular emphasis on sarcomas (Review). Int J Oncol. 2025;67(4). Epub 20250808. PubMed PMID: 40776758; PMCID: PMC12370362. [CrossRef]

- Vautrot V, Hervieu A, Bertaut A, Charon-Barra C, Naiken I, Causseret S, Chaigneau L, Desmoulins I, Rederstoff E, Isambert N, Gobbo J. Small Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers in Sarcoma Follow-Up: Protocol for a Prospective, Multicentric Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2025;14:e63718. Epub 20250909. PubMed PMID: 40925003; PMCID: PMC12457855. [CrossRef]

- Torres MB, Leung CH, Zoghbi M, Lazcano R, Ingram D, Wani K, Keung EZ, Zarzour MA, Scally CP, Hunt KK, Conley A, Bishop AJ, Guadagnolo BA, Farooqi A, Mitra D, Yoder AK, Nakazawa MS, Araujo D, Livingston A, Ratan R, Patel S, Ravi V, Lazar AJ, Roland CL, Somaiah N, Nassif Haddad EF. Dedifferentiated liposarcomas treated with immune checkpoint blockade: the MD Anderson experience. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1567736. Epub 20250430. PubMed PMID: 40370451; PMCID: PMC12075363. [CrossRef]

- Schmid A, Eisenhardt AE, Bogner B, Runkel A, Lausch U, Pauli T, Antolini LN, Boneberg A, Kiefer J, Bronsert P, Boerries M, Eisenhardt SU, Braig D. Intratumoral heterogeneity of cancer driver genomic alterations in myxoid liposarcomas. Cancer. 2025;131(12):e35937. PubMed PMID: 40489430; PMCID: PMC12148203. [CrossRef]

- Versari I, Salucci S, Bavelloni A, Battistelli M, Traversari M, Wang A, Sampaolesi M, Faenza I. The Emerging Role and Clinical Significance of PI3K-Akt-mTOR in Rhabdomyosarcoma. Biomolecules. 2025;15(3). Epub 20250225. PubMed PMID: 40149870; PMCID: PMC11940244. [CrossRef]

- Kruiswijk AA, Kuhrij LS, Dorleijn DMJ, van de Sande MAJ, van Bodegom-Vos L, Marang-van de Mheen PJ. Follow-Up after Curative Surgical Treatment of Soft-Tissue Sarcoma for Early Detection of Recurrence: Which Patients Have More or Fewer Visits than Advised in Guidelines? Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(18). Epub 20230918. PubMed PMID: 37760585; PMCID: PMC10527323. [CrossRef]

- Kerrison WGJ, Lee ATJ, Thway K, Jones RL, Huang PH. Current Status and Future Directions of Immunotherapies in Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Biomedicines. 2022;10(3). Epub 20220228. PubMed PMID: 35327375; PMCID: PMC8945421. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Wang X, Wang X, Qiu F, Zhou B. Challenges and hope: latest research trends in the clinical treatment and prognosis of liposarcoma. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1529755. Epub 20250512. PubMed PMID: 40421219; PMCID: PMC12104207. [CrossRef]

- von Mehren M, Kane JM, Agulnik M, Bui MM, Carr-Ascher J, Choy E, Connelly M, Dry S, Ganjoo KN, Gonzalez RJ, Holder A, Homsi J, Keedy V, Kelly CM, Kim E, Liebner D, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Mesko NW, Meyer C, Pappo AS, Parkes AM, Petersen IA, Pollack SM, Poppe M, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Shabason J, Sicklick JK, Spraker MB, Zimel M, Hang LE, Sundar H, Bergman MA. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(7):815-33. PubMed PMID: 35830886; PMCID: PMC10186762. [CrossRef]

- Resag A, Toffanin G, Benesova I, Muller L, Potkrajcic V, Ozaniak A, Lischke R, Bartunkova J, Rosato A, Johrens K, Eckert F, Strizova Z, Schmitz M. The Immune Contexture of Liposarcoma and Its Clinical Implications. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19). Epub 20220921. PubMed PMID: 36230502; PMCID: PMC9559230. [CrossRef]

- Somaiah N, Tap W. MDM2-p53 in liposarcoma: The need for targeted therapies with novel mechanisms of action. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024;122:102668. Epub 20231210. PubMed PMID: 38104352. [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski SM, Fisher DE. Biology of Melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2021;35(1):29-56. Epub 20201026. PubMed PMID: 33759772. [CrossRef]

- Mataca E, Migaldi M, Cesinaro AM. Impact of Dermoscopy and Reflectance Confocal Microscopy on the Histopathologic Diagnosis of Lentigo Maligna/Lentigo Maligna Melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40(12):884-9. PubMed PMID: 29933314. [CrossRef]

- Switzer B, Puzanov I, Skitzki JJ, Hamad L, Ernstoff MS. Managing Metastatic Melanoma in 2022: A Clinical Review. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(5):335-51. Epub 20220208. PubMed PMID: 35133862; PMCID: PMC9810138. [CrossRef]

- Adler NR, McArthur GA, Mar VJ. Lymphatic and Hematogenous Dissemination in Patients With Primary Cutaneous Melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(11):1322. PubMed PMID: 31509186. [CrossRef]

- Caruso G, Garcia Moreira CG, Iaboni E, Tripodo M, Ferrarotto R, Abbritti RV, Conte L, Caffo M. Tumor Microenvironment in Melanoma Brain Metastasis: A New Potential Target? Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(11). Epub 20250523. PubMed PMID: 40507830; PMCID: PMC12154486. [CrossRef]

- Rhodin KE, Fimbres DP, Burner DN, Hollander S, O’Connor MH, Beasley GM. Melanoma lymph node metastases - moving beyond quantity in clinical trial design and contemporary practice. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1021057. Epub 20221014. PubMed PMID: 36411863; PMCID: PMC9675405. [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff W, Mwamba RN, Grullon K, Armstrong M, Zhao P, Hendren-Santiago B, Qin KH, Li AJ, Hu DA, Youssef A, Reid RR, Luu HH, Shen L, He TC, Haydon RC. Melanoma: Molecular genetics, metastasis, targeted therapies, immunotherapies, and therapeutic resistance. Genes Dis. 2022;9(6):1608-23. Epub 20220427. PubMed PMID: 36157497; PMCID: PMC9485270. [CrossRef]

- Braden J, Conway JW, Wilmott JS, Scolyer RA, Long GV, da Silva IP. Do BRAF-targeted therapies have a role in the era of immunotherapy? ESMO Open. 2025;10(7):105314. Epub 20250620. PubMed PMID: 40543211; PMCID: PMC12221719. [CrossRef]

- Kolathur KK, Nag R, Shenoy PV, Malik Y, Varanasi SM, Angom RS, Mukhopadhyay D. Molecular Susceptibility and Treatment Challenges in Melanoma. Cells. 2024;13(16). Epub 20240820. PubMed PMID: 39195270; PMCID: PMC11352263. [CrossRef]

- Yang TT, Yu S, Ke CK, Cheng ST. The Genomic Landscape of Melanoma and Its Therapeutic Implications. Genes (Basel). 2023;14(5). Epub 20230429. PubMed PMID: 37239381; PMCID: PMC10218388. [CrossRef]

- Guo W, Wang H, Li C. Signal pathways of melanoma and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):424. Epub 20211220. PubMed PMID: 34924562; PMCID: PMC8685279. [CrossRef]

- Lade-Keller J, Riber-Hansen R, Guldberg P, Schmidt H, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Steiniche T. E- to N-cadherin switch in melanoma is associated with decreased expression of phosphatase and tensin homolog and cancer progression. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(3):618-28. PubMed PMID: 23662813. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Yan Y, Wei W. Research advances of matrix metalloproteinases family in uveal melanoma. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):609. Epub 20250709. PubMed PMID: 40635067; PMCID: PMC12239450. [CrossRef]

- Hunter MV, Joshi E, Bowker S, Montal E, Ma Y, Kim YH, Yang Z, Tuffery L, Li Z, Rosiek E, Browning A, Moncada R, Yanai I, Byrne H, Monetti M, de Stanchina E, Hamard PJ, Koche RP, White RM. Mechanical confinement governs phenotypic plasticity in melanoma. Nature. 2025. Epub 20250827. PubMed PMID: 40866703. [CrossRef]

- Reiss Y, Proudfoot AE, Power CA, Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. CC chemokine receptor (CCR)4 and the CCR10 ligand cutaneous T cell-attracting chemokine (CTACK) in lymphocyte trafficking to inflamed skin. J Exp Med. 2001;194(10):1541-7. PubMed PMID: 11714760; PMCID: PMC2193675. [CrossRef]

- Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, DeNardo DG, Egeblad M, Evans RM, Fearon D, Greten FR, Hingorani SR, Hunter T, Hynes RO, Jain RK, Janowitz T, Jorgensen C, Kimmelman AC, Kolonin MG, Maki RG, Powers RS, Pure E, Ramirez DC, Scherz-Shouval R, Sherman MH, Stewart S, Tlsty TD, Tuveson DA, Watt FM, Weaver V, Weeraratna AT, Werb Z. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(3):174-86. Epub 20200124. PubMed PMID: 31980749; PMCID: PMC7046529. [CrossRef]

- Basak U, Sarkar T, Mukherjee S, Chakraborty S, Dutta A, Dutta S, Nayak D, Kaushik S, Das T, Sa G. Tumor-associated macrophages: an effective player of the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1295257. Epub 20231116. PubMed PMID: 38035101; PMCID: PMC10687432. [CrossRef]

- Sun M, Wu J. Molecular and immune landscape of melanoma: a risk stratification model for precision oncology. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):667. Epub 20250504. PubMed PMID: 40319421; PMCID: PMC12050255. [CrossRef]

- Ju W, Cai HH, Zheng W, Li DM, Zhang W, Yang XH, Yan ZX. Cross-talk between lymphangiogenesis and malignant melanoma cells: New opinions on tumour drainage and immunization (Review). Oncol Lett. 2024;27(2):81. Epub 20240105. PubMed PMID: 38249813; PMCID: PMC10797314. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi E, Chiari C, Madina BR, Yarovinsky TO, Krady MM, Chen J, Almassian B, Nakaar V, Wang K. CARG-2020 targets IL-12, IL-17, and PD-L1 pathways to effectively treat melanoma and breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):29649. Epub 20250813. PubMed PMID: 40804279; PMCID: PMC12350727. [CrossRef]

- Knight A, Karapetyan L, Kirkwood JM. Immunotherapy in Melanoma: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(4). Epub 20230209. PubMed PMID: 36831449; PMCID: PMC9954703. [CrossRef]

- Michielon E, de Gruijl TD, Gibbs S. From simplicity to complexity in current melanoma models. Exp Dermatol. 2022;31(12):1818-36. Epub 20221005. PubMed PMID: 36103206; PMCID: PMC10092692. [CrossRef]

- Hu A, Sun L, Lin H, Liao Y, Yang H, Mao Y. Harnessing innate immune pathways for therapeutic advancement in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):68. Epub 20240325. PubMed PMID: 38523155; PMCID: PMC10961329. [CrossRef]

- Ernst M, Giubellino A. The Current State of Treatment and Future Directions in Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. Biomedicines. 2022;10(4). Epub 20220331. PubMed PMID: 35453572; PMCID: PMC9029866. [CrossRef]

- Reschke R, Enk AH, Hassel JC. Prognostic Biomarkers in Evolving Melanoma Immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2025;26(2):213-23. Epub 20241221. PubMed PMID: 39707058; PMCID: PMC11850490. [CrossRef]

- Patton EE, Mueller KL, Adams DJ, Anandasabapathy N, Aplin AE, Bertolotto C, Bosenberg M, Ceol CJ, Burd CE, Chi P, Herlyn M, Holmen SL, Karreth FA, Kaufman CK, Khan S, Kobold S, Leucci E, Levy C, Lombard DB, Lund AW, Marie KL, Marine JC, Marais R, McMahon M, Robles-Espinoza CD, Ronai ZA, Samuels Y, Soengas MS, Villanueva J, Weeraratna AT, White RM, Yeh I, Zhu J, Zon LI, Hurlbert MS, Merlino G. Melanoma models for the next generation of therapies. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(5):610-31. Epub 20210204. PubMed PMID: 33545064; PMCID: PMC8378471. [CrossRef]

- Singh SP, Madke T, Chand P. Global Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2025;15(2):102446. Epub 20241028. PubMed PMID: 39659901; PMCID: PMC11626783. [CrossRef]

- Gan C, Yuan Y, Shen H, Gao J, Kong X, Che Z, Guo Y, Wang H, Dong E, Xiao J. Liver diseases: epidemiology, causes, trends and predictions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):33. Epub 20250205. PubMed PMID: 39904973; PMCID: PMC11794951. [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca LG, Araujo RLC. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: Advances, challenges and opportunities in a rare malignancy. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2025;17(10):109107. PubMed PMID: 41178855; PMCID: PMC12576631. [CrossRef]

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. Epub 20210121. PubMed PMID: 33479224. [CrossRef]

- Salimiaghdam N, Mustafa A, Pokuaa IO, Hamidi A, Chen E. Recurrent Aggressive Hepatocellular Carcinoma Presenting With Chest Wall Metastasis and Portal Vein Thrombosis: A Rare Case and a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Cureus. 2025;17(7):e87330. Epub 20250705. PubMed PMID: 40762000; PMCID: PMC12320916. [CrossRef]

- Macedo F, Ladeira K, Pinho F, Saraiva N, Bonito N, Pinto L, Goncalves F. Bone Metastases: An Overview. Oncol Rev. 2017;11(1):321. Epub 20170509. PubMed PMID: 28584570; PMCID: PMC5444408. [CrossRef]

- Terada T, Maruo H. Unusual extrahepatic metastatic sites from hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(5):816-20. Epub 20130415. PubMed PMID: 23638212; PMCID: PMC3638091.

- Wang S, Wang A, Lin J, Xie Y, Wu L, Huang H, Bian J, Yang X, Wan X, Zhao H, Huang J. Brain metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and future avenues. Oncotarget. 2017;8(15):25814-29. PubMed PMID: 28445959; PMCID: PMC5421971. [CrossRef]

- Ramaite FT, Nkadimeng SM. Targeting inflammatory pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma: recent developments. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):1174. Epub 20250622. PubMed PMID: 40544399; PMCID: PMC12183140. [CrossRef]