1. Introduction

Natural history collections (NHCs) host large amounts of specimens collected since the 17th century. The total amount of specimens worldwide is estimated at more than 2 billion [

1]. Herbaria, which are natural history collections of dried plant specimens, are estimated to host ca. 400 million specimens worldwide [

2]. Each specimen normally has one or more labels reporting metadata such as scientific name, date and locality of collection, collector, etc. These data are pivotal for understanding the evolution of biodiversity [

3], and for forecasting its changes in the future, other than for a wide array of other research topics [

4,

5].

The mobilization of specimen data utilizing digitization is thus particularly relevant [

6,

7,

8]. While several digitization efforts are made manually, massive and industrialized workflows to improve digitization efficiency have been experimented on botanical [

9] and, more recently, entomological collections. In general, modern digitization efforts follow an image-to-data workflow [

10]. This consists of taking digital images of specimens and their labels, from which metadata are transcribed. This allows for a limited manipulation of the specimens, which, being biological objects, are particularly prone to deterioration [

11,

12]. Label data are then usually published in “global” repositories such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) organized with a common standard, such as Darwin Core [

13].

To further increase the efficiency of digitization actions, the process of metadata extraction - which is quite labor-intensive [

14,

15] - through computer vision for automated metadata extraction is being investigated [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Since standard OCR was seen as the only tool able to recognize printed and handwritten strings on labels, most previous attempts focused on combining an OCR system and a natural language processing (NLP) algorithm, the former to get unstructured information out of the image, the latter to tackle Name Entity Recognition (NER). Those systems normally provide an interface where a human operator can correct or enter missing data from scratch. HERBIS19 [

20] and SALIX20 [

16] are representatives of such a design. Simple OCR approaches can speed up data entry supporting label transcription, but they cannot overcome limitations related to lackluster label quality [

16]. Indeed, these approaches still require motivated manpower for day-to-day supervision of their output, since they are not - at the current state of the art - reliable enough. With the advancement of OCR technologies and the emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs), however, it was possible to create new integrated workflows. “Publish First” [

21] is an example of this novel approach. These approaches, however, rely on fully developed services accessible by APIs, often managed by external entities, which can be commercial companies. Thus, several drawbacks could arise, the first being that it is usually impossible to interpret and improve all the components in the workflow relying on external APIs. Except for a satisfactory result obtained in a pipeline which used external services, like GPT-4, no other explicit explanation supporting service choice or further analysis of worst cases can be provided [

21]. Furthermore, data privacy and confidentiality often cannot be properly ensured when using LLMs hidden behind APIs, since they may store or misuse private or sensitive data, thus exposing users to the risk of private data leakage [

22].

A fully trainable and adjustable information extraction (IE) model composed of only open-source solutions is, however, still lacking. This challenge has been partly addressed with the development of a novel automated label data extraction and database generation system from herbarium specimen images using OCR and NER [

23]. This workflow uses the SpaCy python package for NER parsing after the text has been extracted through the Google Cloud Vision OCR service. While this NER parsing solution is promising and innovative, the OCR service it uses is not flexible enough to tackle the complexity arising from different label formats. An OCR can detect and recognize the portions of text in a document but not understand them and their content based on their position in the image. Google’s OCR is also a closed-source service, thus limiting users in its tailoring to their needs. With the advent of new techniques in NLP and Computer Vision (CV), driven by the rise of Transformer [

24], however, an alternative approach leveraging their power and versatility might be developed. Thanks to Transfer Learning [

25], Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs), trained with huge sets of general data, can be fine-tuned for specific sub-tasks targeting fewer data. Several Language-Vision Transformers were developed, since [

26] proposed the Multimodal Transformer (MulT), a cross-modal attention mechanism based on a Transformer, capable of decreasing the stress of explicit data aligning. These approaches had astonishing performances, as evidenced by [

27] in the development of TrOCR and [

28] in the development of Donut. Language-vision models include both an image encoder and a text decoder. They are trained to recognize all texts in images and to extract information, but with some differences. TrOCR takes text lines as input and is not suitable for NER out of the box, while Donut is better suited for an IE task [

27].

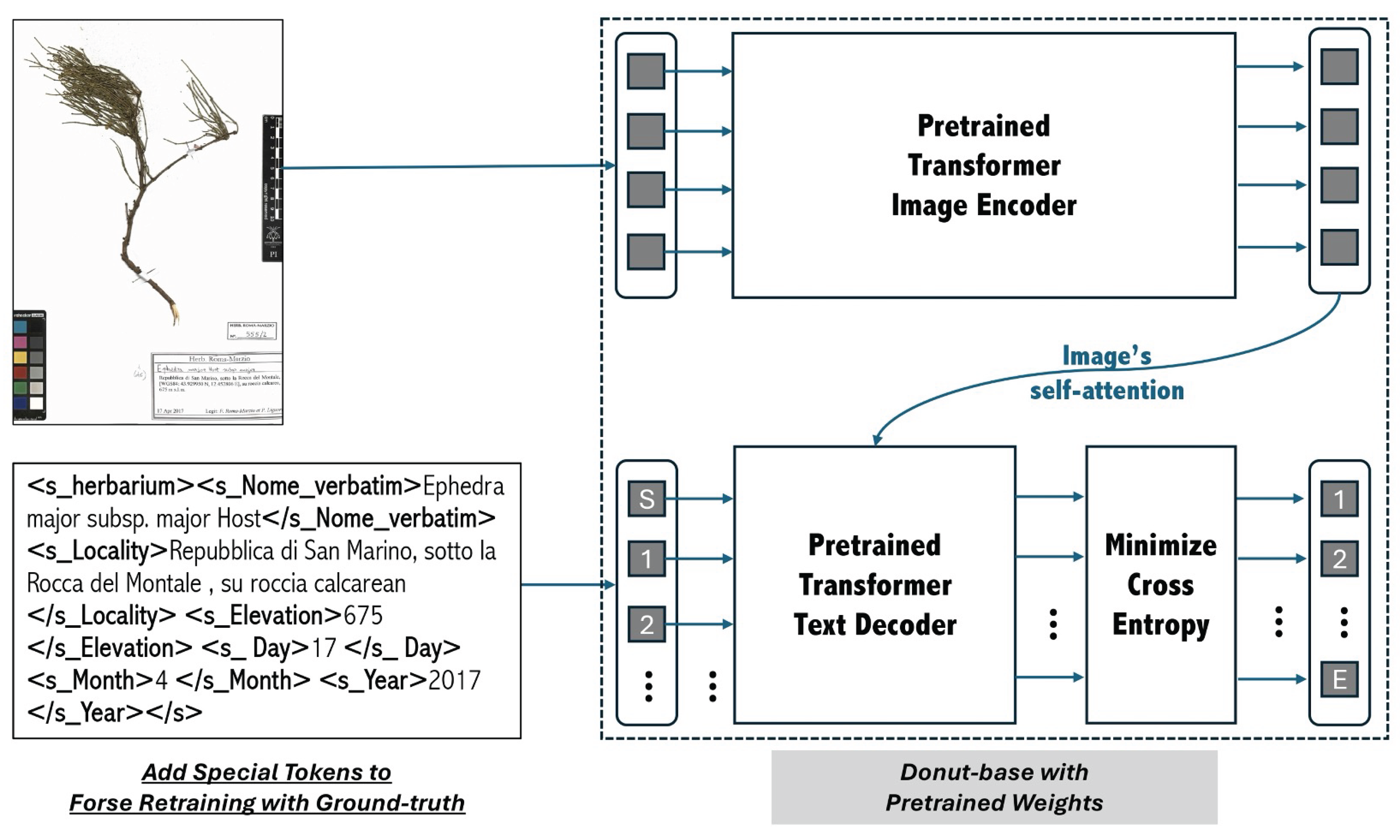

This research aims at describing the first successful fine-tuning of Donut [

28] to automatically extract information from herbarium specimen labels and to arrange them in the concepts of the metadata standard scheme Darwin Core [

13], which is internationally adopted for the interoperability of these data. This is the first real-world use of the latest multimodal Transformer to effectively facilitate the difficult tasks of digitizing herbarium specimens.

3. Results

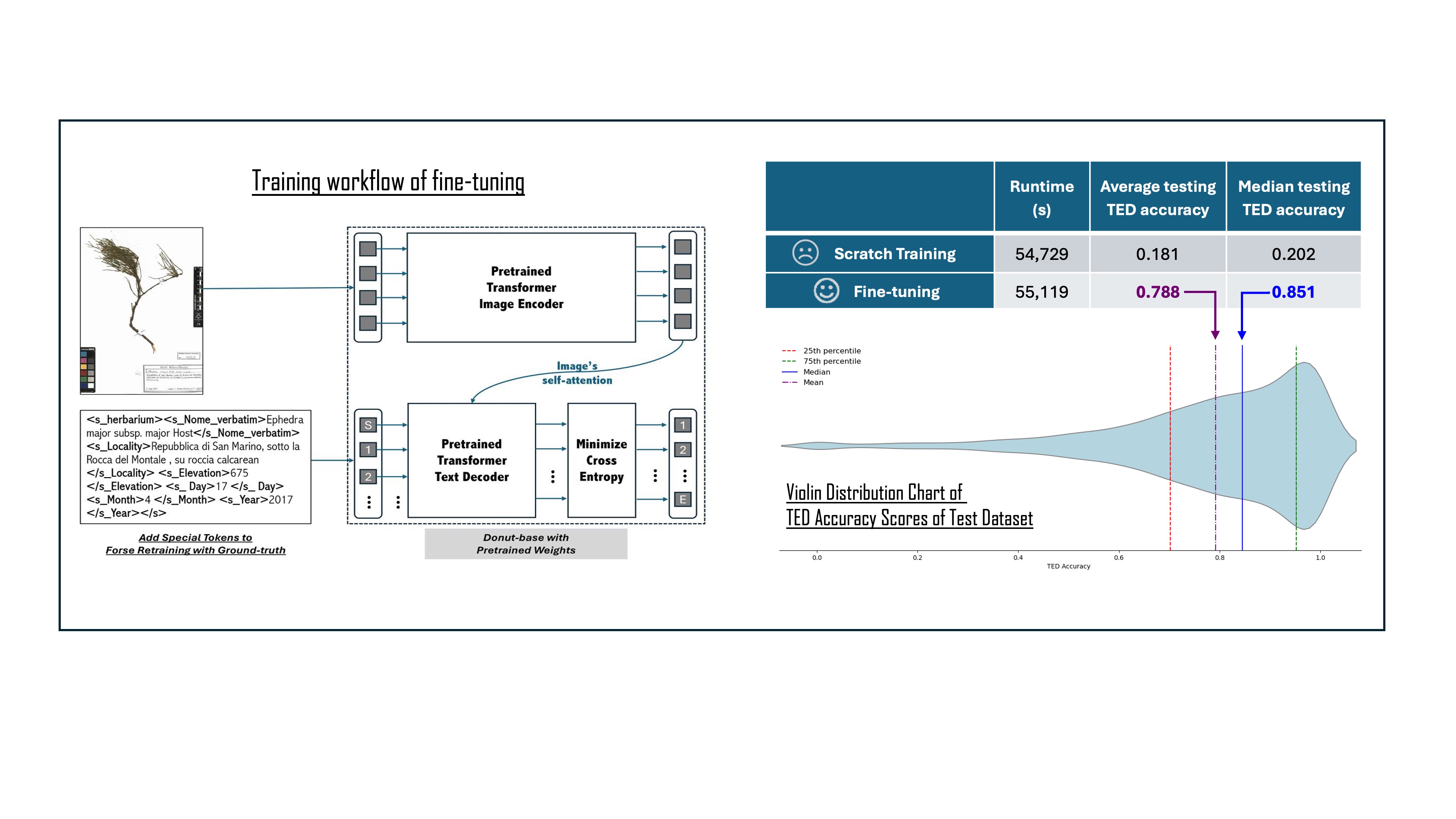

Three attempts of fine-tuning were conducted with different image resolution setups, and all models’ performances were assessed on the same test image dataset with corresponding resolutions: 600×800, 960×1280, and 1200×1600. As shown in

Table 3, TED accuracies increase with the image resolution. Thus, the 1200×1600 resolution was adopted for further inference as it achieved the best TED accuracy median score.

To test whether the pre-trained Donut transferred the effective learning process to the IE task of extracting information from specimen labels, the model was also trained from scratch with images at 1200×1600 and the same parameters used in the fine-tuning. For comparison, the scratch training was stopped after five epochs, which is the same as the training epoch in the fine-tuning with 1200×1600 images.

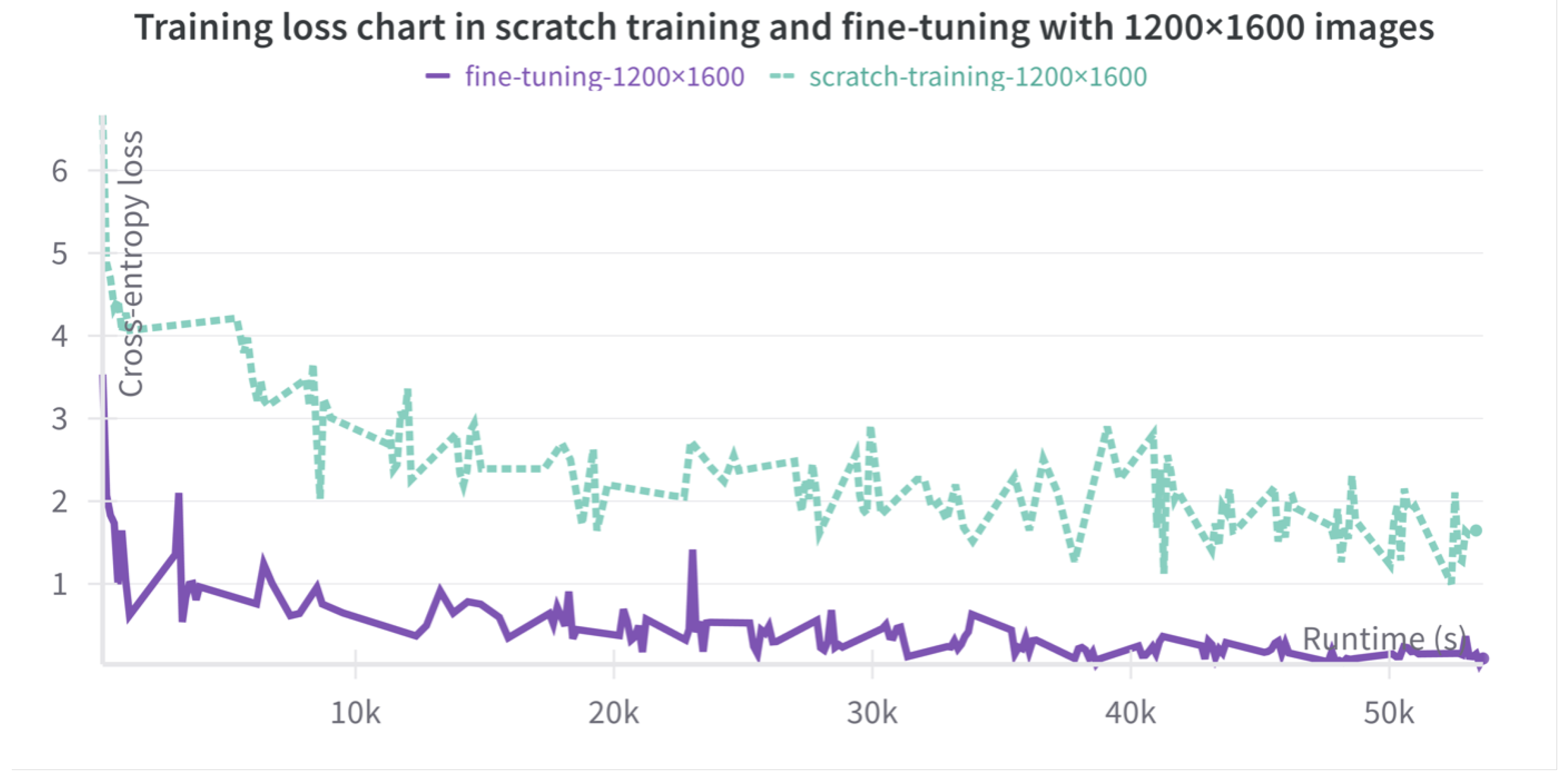

After an initial training from scratch of five epochs without early stopping, the process evidenced a limited improvement in both training loss and evaluation score. In

Figure 2, both training from scratch loss curves remain high, if compared with fine-tuning. A detailed comparison is reported in

Table 4.

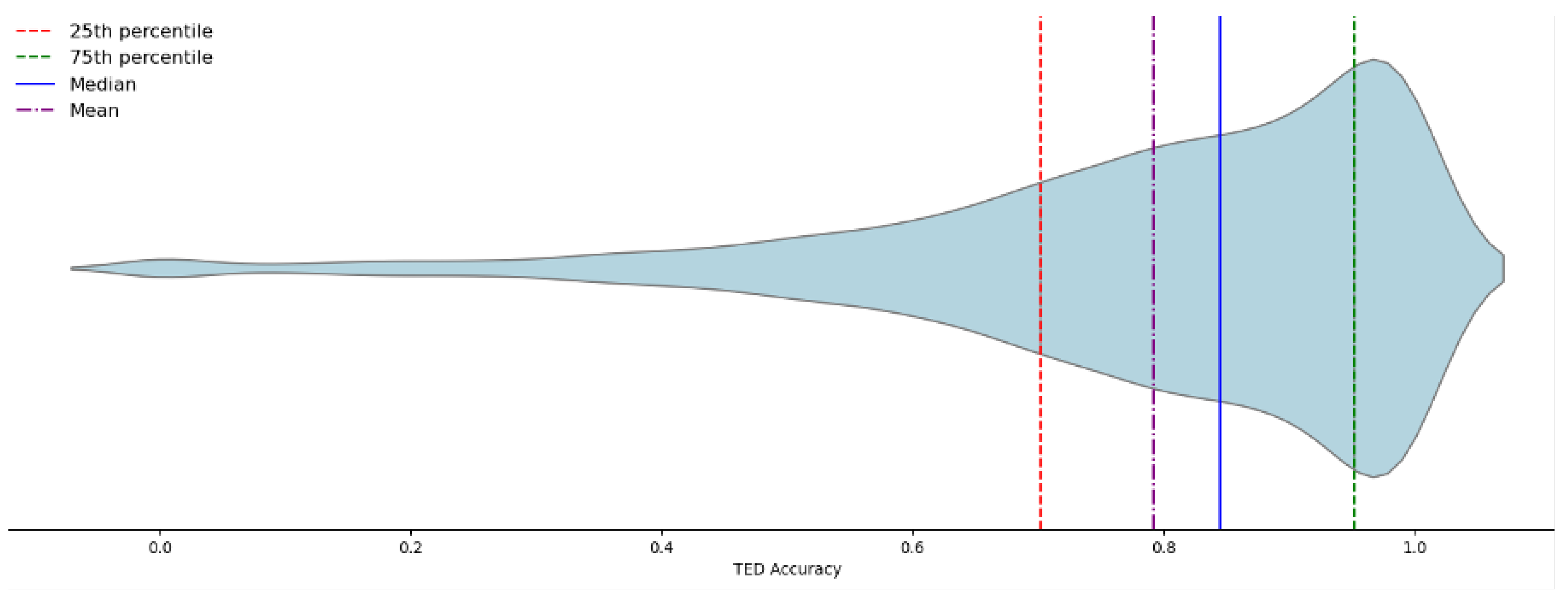

In

Table 3 and

Table 4, even if median and average TED accuracy have margin to 1, which is the max TED accuracy score, the evaluation has been satisfactory considering the TED accuracy distribution in the test dataset. In more than 75% of the cases, the TED accuracy score is higher than 0.702 (

Figure 3), and in 25% of the cases it is higher than 0.952.

The lower performances, however, are not necessarily errors in the identification of the text. They might represent “false negatives”, often due to differences between the ground truth and the actual text on the labels.

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 showcase several examples of different performance, from the lowest to the best. The images in the tables are available also as supplementary materials (

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5,

Figure A6,

Figure A7 and

Figure A8). In the tables the text in green is the portion which is identical in the ground truth and in the prediction, while in red the portion which differs.

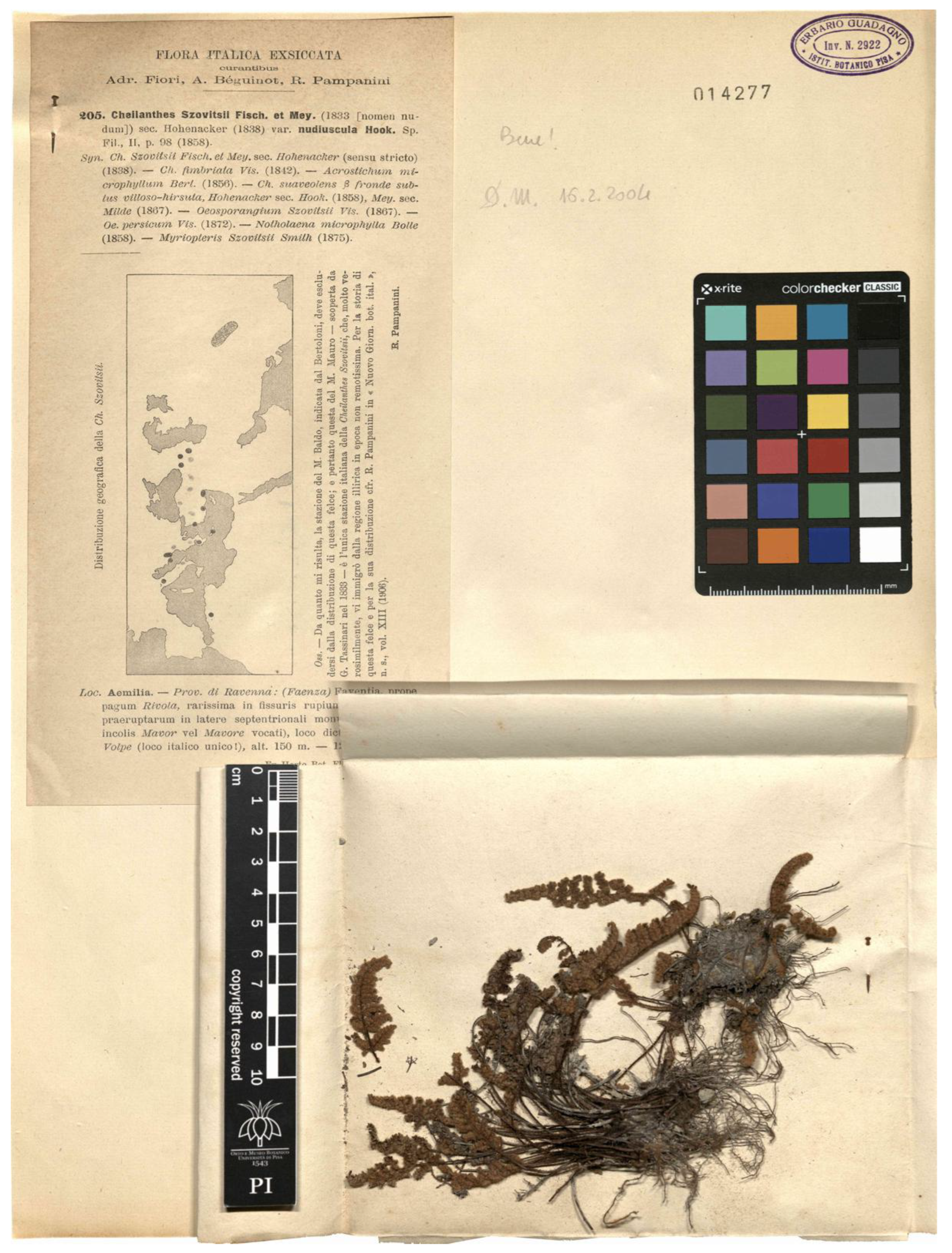

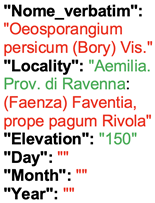

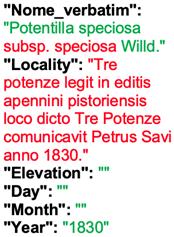

In

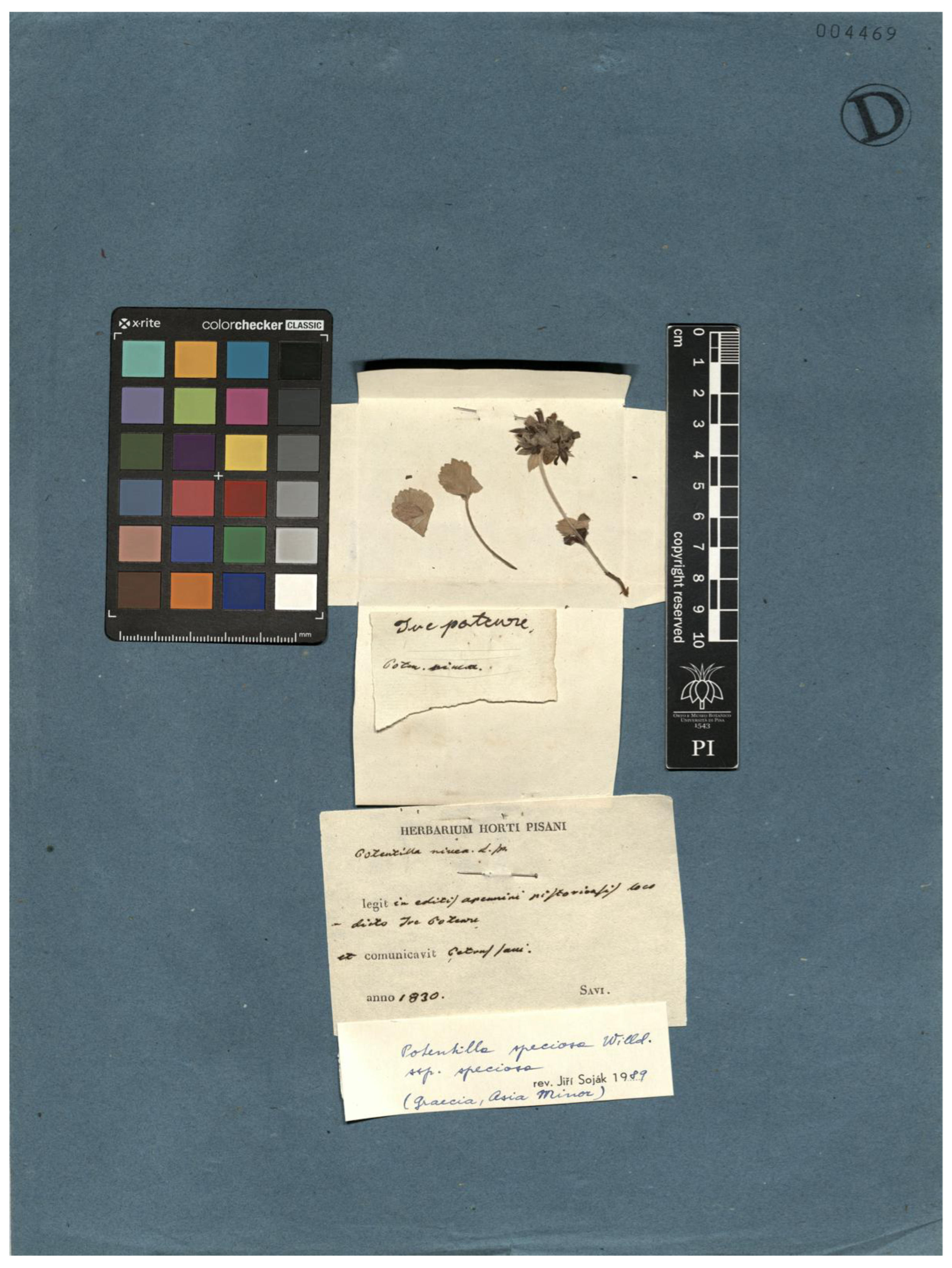

Table 5 there are two specimens for which the accuracy score is 0. In the first case, the fine-tuned Donut correctly extracted the scientific name, though only partially as it missed the authorities and the variety. However, it is worth noting that the ground truth provided for this specimen differs from what is literally written on the label. This is because the name in the dataset was updated due to recent nomenclatural changes. In fact, one of the synonyms listed in the label is the currently accepted name of the taxon, while the name which was used on the label was not valid since it is a nomen nudum (i.e., not validly published), and should be discarded.

The extracted gathering locality is partially accurate, but the subsequent information in Latin, which in the image is partly hidden by the envelope of the specimen, is not extracted correctly. Thus, even if the TED accuracy score is 0, the algorithm extracted correctly at least part of the information. Thus, this case could be listed among the “false negatives”. In the second case of

Table 5, the TED accuracy of 0 is due to the presence of two specimens on a single sheet, and to the presence in the ground truth of the transcription of the first one alone. Donut, on the contrary, extracted (correctly) the information from the second label alone. If the latter were considered, the TED accuracy would have been close to 1. However, Donut missed one of the two labels.

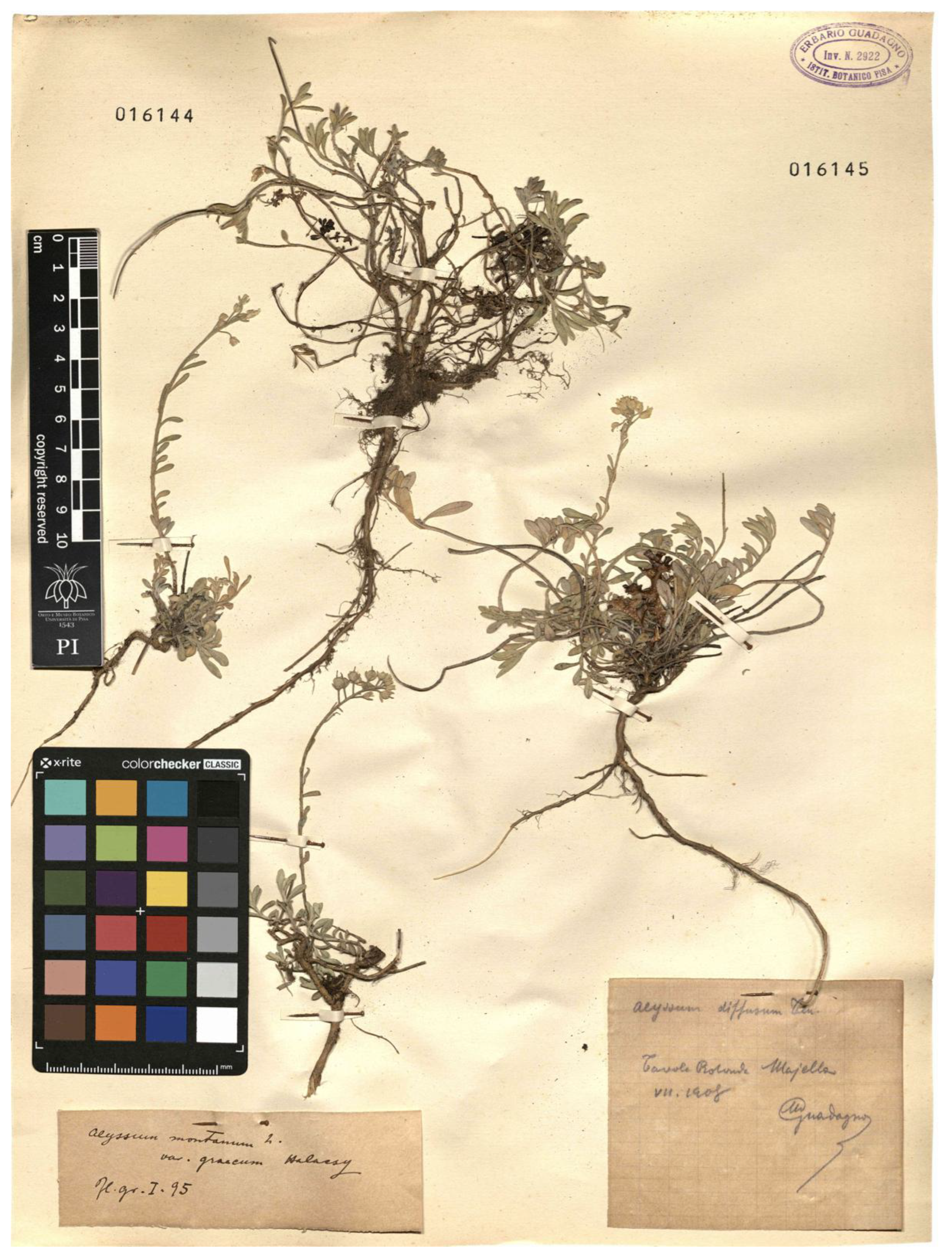

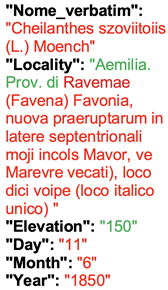

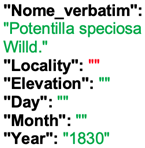

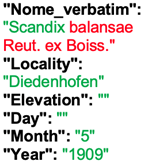

In

Table 6, there are two examples of poor performance (TED accuracy ca. 0.2). In the first case, the presence of three labels (instead of the classical one) could be the cause of the poor performance. Donut extracted the scientific name (while missing the variety) from the label at the bottom, while took the year of gathering from the second one. It did not extract other information, such as the gathering locality. The ground truth, however, is not corresponding to one label alone. The scientific name was taken from the third label, but is not written correctly, since the authority (Willd.) should be placed after the binomial (Potentilla speciosa), and not after the variety (var. speciosa). Even the ground truth took the gathering date from the second label, together with the locality.

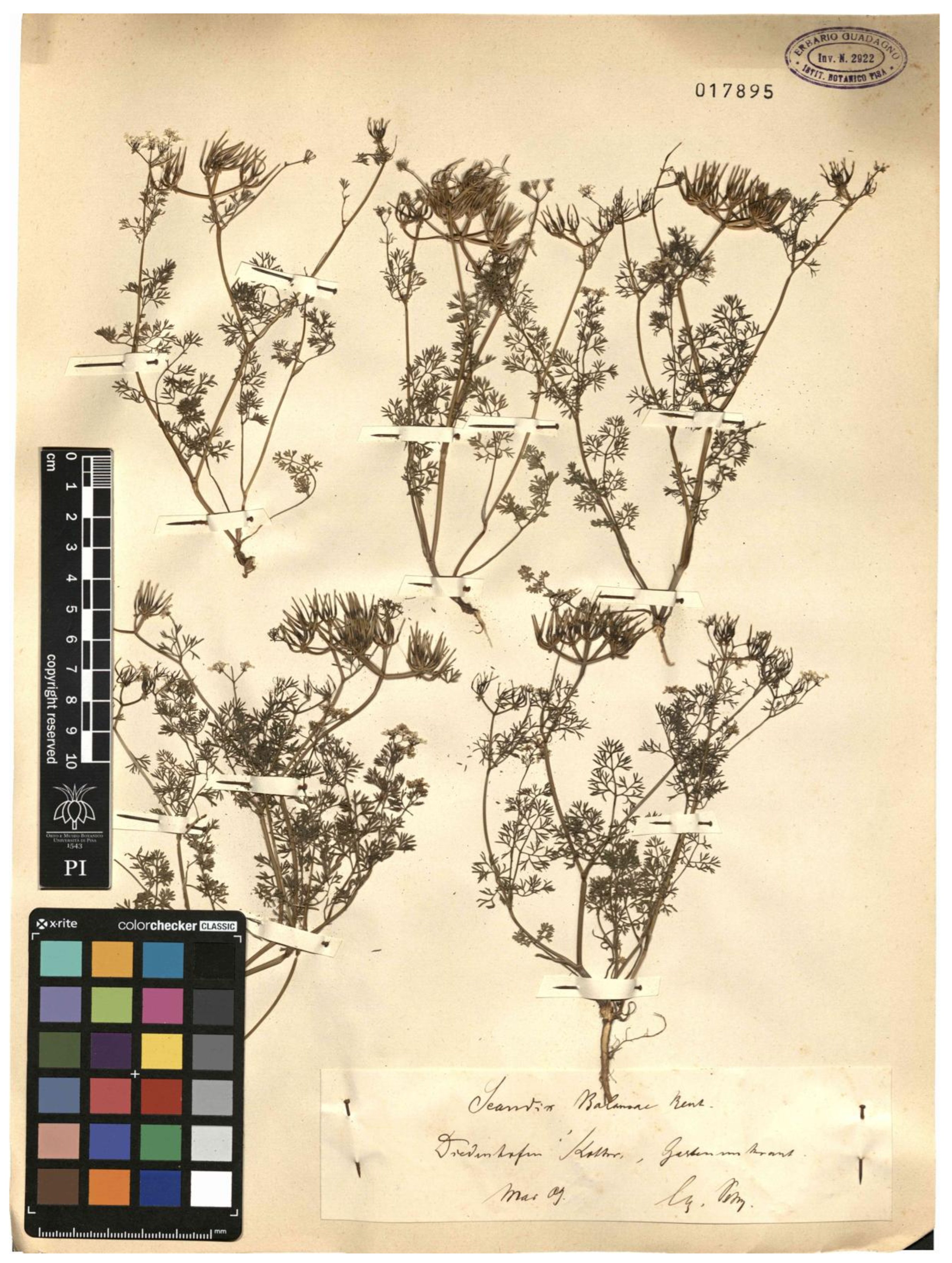

In the second case, Donut extracted a scientific name which is correct only as far as the genus is concerned (Scandix), while the species and authority are incorrect. The locality of collection was extracted entirely, while in the ground truth, it was only partially transcribed. However, Donut probably interpreted the text incorrectly, which was not transcribed in the ground truth. The gathering year is correct.

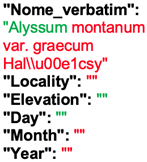

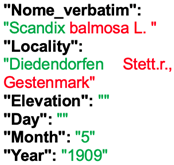

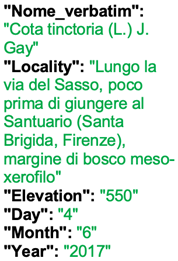

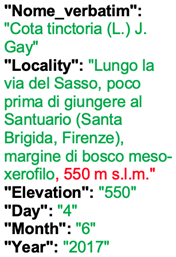

In

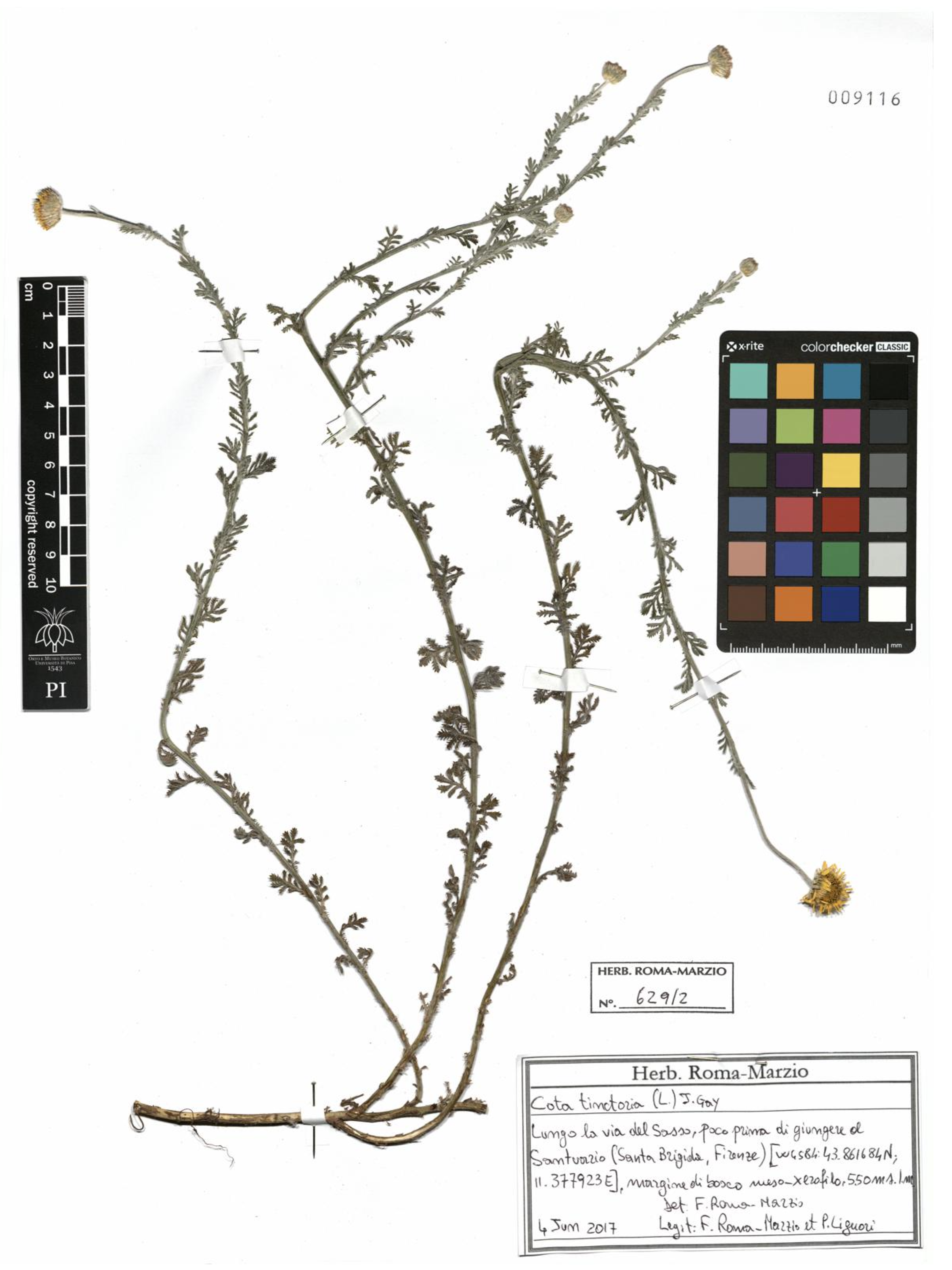

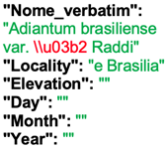

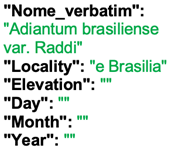

Table 7, there are two examples in which the TED accuracy score was higher than 0.8. In these cases, the discrepancies between the predicted text and the ground truth are slight, if not irrelevant. In the first example, Donut predicted perfectly the content of the label, the only difference being in the inclusion of the altitude in the locality. The altitude is repeated in its concept as well. Thus, this is not an error in recognition, but in the organization of the output.

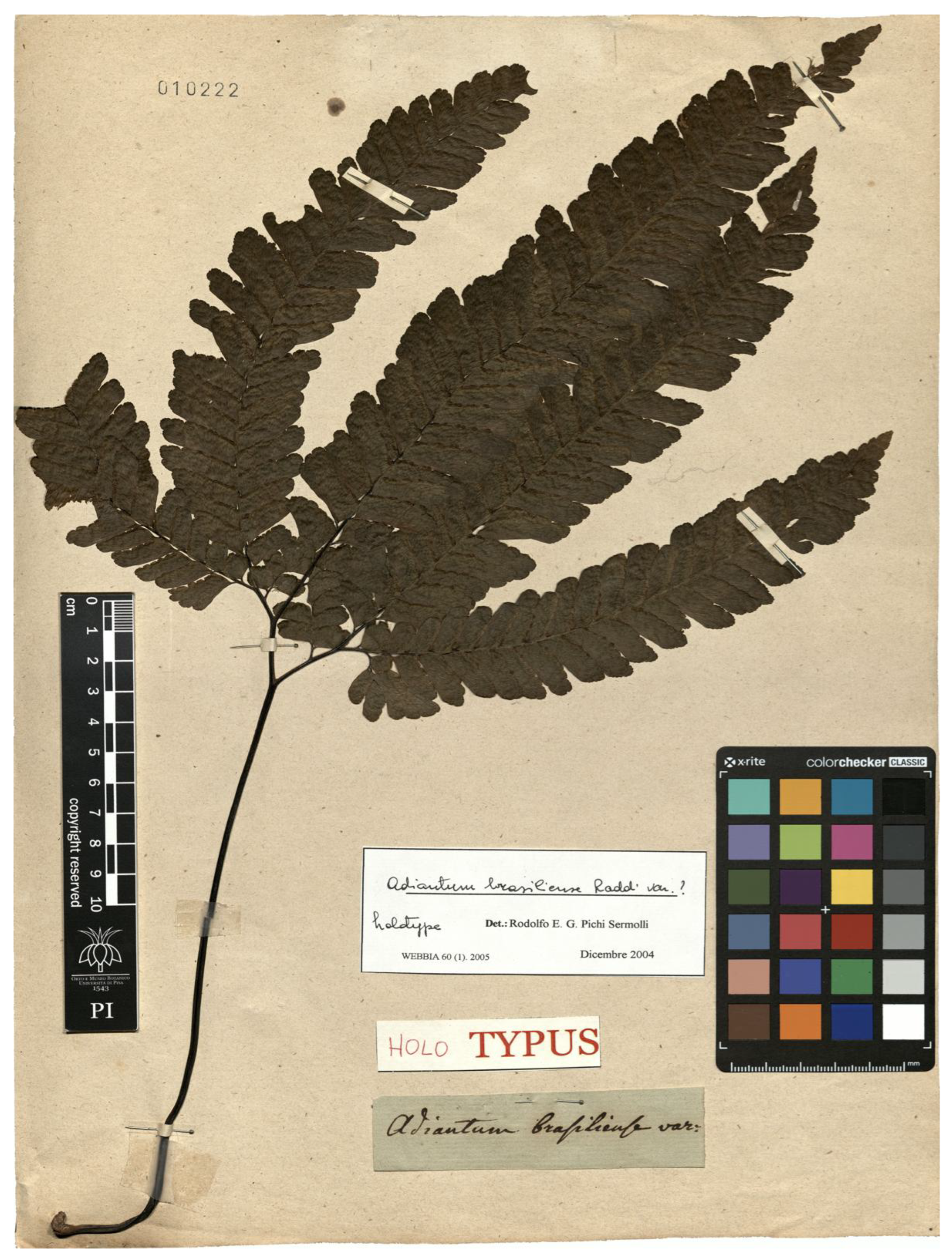

The second case is quite interesting. While the score in TED accuracy is lower than 1, the error is due to the presence of a typo in the ground truth. Donut predicted the text correctly, but for an error which is also present in the ground truth, i.e., the string of the scientific name, in which the authority (Raddi) is misinterpreted as the variety. In fact, while on the label the scientific name is written correctly (Adiantum brasiliense Raddi) and it is followed by the string “var.?”, which indicates that the specimen is probably a variety of the nominal species, the variety itself still lacks a proper identification. In both cases, anyway, the performance is satisfactory.

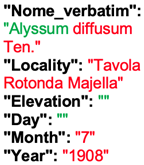

Table 8 displays some examples of a perfect TED accuracy score (1.0). In both cases, the prediction is exactly the same as the ground truth, which is the correct transcription of the contents of the label. While the first specimen has a handwritten label, the second is typewritten. In both cases one label alone is present on the herbarium sheet, which hosts a single specimen (the ideal scenario).

4. Discussion

Extracting metadata from natural history collection specimens is a challenging task, which calls for a relevant effort [

14,

15] if carried out manually. Thus, several attempts have been made to automate at least partially the process thanks to the use of OCR solutions, or by coupling an OCR with an NLP algorithm [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] take full advantage of the emergence of LLMs, creating integrated workflows. However, most of these examples rely on APIs managed by external entities, thus leading to several drawbacks, especially related to the lack of customizing and fine-tuning opportunities. The development of a fully customizable and adjustable IE approach could be seen as a step forward. [

23] explored this solution by coupling a customizable SpaCy Python package for NER parsing with the Google Cloud Vision OCR service. However, this approach still lacks customization and fine-tuning opportunities as far as the OCR service is concerned.

Thus, we tried a novel approach to the problem by taking advantage of Transfer Learning [

25], which allows to fine-tune LVLMs that have been pre-trained with huge sets of general data. Among the different possible solutions, we adopted Donut [

27]. If compared to training a model from scratch, fine-tuning a pre-trained LVLM yields substantial performance improvements. A pre-trained LVLM as Donut, even if trained for more general-purpose tasks, is trained on datasets which are far larger than any domain-specific dataset. In the case of natural history specimens, a dataset should consist of images coupled with their metadata transcribed verbatim (the ground truth). Given the amount of images and data required, training from scratch a model for performing on this specific domain could be quite difficult. In our experience, training from scratch was ineffective if compared to the fine-tuning, especially at our dataset size. The fine-tuning process took less time and provided far better results, with a TED of 0.910 compared to 0.629 in the best-case scenario of training from scratch. Another issue related to training from scratch, other than the size of the training set, is related to the quality of the data. Existing domain-specific datasets produced by digitizing natural history collections sometimes do not contain the actual ground truth, but metadata which are derived from the ground truth. As an example, in some datasets, the localities of gathering of the specimens are not reported as they are written on the label, but homogenized according to some gazetteer, or toponymic database. In other cases, the scientific names are corrected, if they were written incorrectly on the label (e.g., without the authorities, or abbreviated), or even updated to the last nomenclatural updates (without updating the names written on the labels). Similar issues were also present in the dataset we adopted for the fine-tuning of Donut in this research.

The fine tuning allowed for quite satisfactory results (

Figure 3). The median testing TED accuracy (0.851) highlights that the predictions of the fine-tuned Donut are generally quite close to the ground truth, and (

Table 5 and

Table 6) often a poor TED accuracy is not due to actual errors in the prediction, but in differences between the ground truth and the actual texts on the specimens’ labels (“false negatives”). The poorer performances are in general due to a) more than one label on the same herbarium sheet, often related to the presence of more than one specimen, and/or b) very poor handwriting. The metadata of specimens with one label are normally correctly predicted, even if the label is handwritten. In modern collections, this is mostly the case, while herbarium sheets with more than one label are rare. Thus, this approach could be potentially applied successfully to the digitization workflow for herbarium specimens. Further investigation is necessary for understanding the replicability of this approach on other natural history collections. However, wherever labels are visible in digital images, the replicability of this approach is potentially feasible.

While in this experience we adopted Donut as a base model for fine-tuning, a similar approach can be applied to any general-purpose LVLM. Since LVLMs are evolving at an incredibly fast pace, novel LVLMs could demonstrate better performance in the same domain than the relatively “old” Donut.

Author Contributions: Jacopo Zacchigna

Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing; Weiwei Liu (Corresponding Author): Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing; Felice Andrea Pellegrino: Supervision, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing; Adriano Peron: Supervision, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing; Francesco Roma-Marzio: Data Curation, Resources; Lorenzo Peruzzi: Data Curation, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing; Stefano Martellos: Supervision, Investigation (Herbarium Specimen Analysis), Validation, Writing – Review & Editing, Resources (Biodiversity Expertise).

Figure 2.

Training loss curves of training from scratch (dotted lines) and fine-tuning (continuous line) with images at a resolution of 1200×1600. Training loss curves track the decrease in cross-entropy loss during training. Even with longer training if compared to fine-tuning, the training from scratch loss never decreases enough, evidencing a poorer performance.

Figure 2.

Training loss curves of training from scratch (dotted lines) and fine-tuning (continuous line) with images at a resolution of 1200×1600. Training loss curves track the decrease in cross-entropy loss during training. Even with longer training if compared to fine-tuning, the training from scratch loss never decreases enough, evidencing a poorer performance.

Figure 3.

Violin distribution chart of the evaluation on the test set of 1200×1600 images. The 25th and 75th percentiles respectively are 0.702 and 0.952. The median value and the average value have been reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4. More than 75% of test images achieved an accuracy score of more than 0.7. Test images with low accuracy scores are rare in the test set.

Figure 3.

Violin distribution chart of the evaluation on the test set of 1200×1600 images. The 25th and 75th percentiles respectively are 0.702 and 0.952. The median value and the average value have been reported in

Table 3 and

Table 4. More than 75% of test images achieved an accuracy score of more than 0.7. Test images with low accuracy scores are rare in the test set.

Table 1.

Comparison of the capabilities of different base models on the mainstream benchmark CORD dataset. Four features have been selected for the comparison of base models: (1) Text recognition, i.e., OCR shouldn’t be a bottleneck for text recognition; (2) Multi-lingual support, i.e., the base model should be able to deal with different languages; (3) Complex format support, i.e., the capability of accurate recognition in various document formats; (4) CORD score i.e., the Tree Edit Distance (TED) accuracy in CORD benchmark.

Table 1.

Comparison of the capabilities of different base models on the mainstream benchmark CORD dataset. Four features have been selected for the comparison of base models: (1) Text recognition, i.e., OCR shouldn’t be a bottleneck for text recognition; (2) Multi-lingual support, i.e., the base model should be able to deal with different languages; (3) Complex format support, i.e., the capability of accurate recognition in various document formats; (4) CORD score i.e., the Tree Edit Distance (TED) accuracy in CORD benchmark.

| |

(1) Text Recognition |

(2)Multi-lingual Support |

(3) Complex Format Support |

(4) CORD Score (Tree-based edit distance Accuracy) [28] |

| BERT [33] |

External OCR |

Yes |

No |

65.5 |

| BROS [34] |

OCR |

No |

No |

70.0 |

| LayoutLM [35] |

OCR |

No |

Yes |

81.3 |

| LayoutLM v2 [36] |

OCR |

Yes |

Yes |

82.4 |

| TrOCR [27] |

OCR-free |

No |

No |

NA |

| Donut [28] |

OCR-free |

Yes |

Yes |

90.9 |

Table 2.

Batch size selected for three fine-tuning variations. The batch size is limited by the 64GB graphics memory and is correlated with the storage size of one image. Thus, the larger the resolution is, the smaller the batch size is.

Table 2.

Batch size selected for three fine-tuning variations. The batch size is limited by the 64GB graphics memory and is correlated with the storage size of one image. Thus, the larger the resolution is, the smaller the batch size is.

| |

600×800 |

960×1280 |

1200×1600 |

| Batch size |

10 |

8 |

5 |

Table 3.

Runtime and testing TED accuracy of three versions Donut fine-tuning with an image resolution of 600×800, 960×1280, and 1200×1600. Three variations were fine-tuned with the same Leonardo HPC system with four NVIDIA Ampere A100-64 GPUs to ensure the runtime was comparable among them. The test datasets used for testing TED accuracies of all fine-tuning versions are the same and kept apart from the training.

Table 3.

Runtime and testing TED accuracy of three versions Donut fine-tuning with an image resolution of 600×800, 960×1280, and 1200×1600. Three variations were fine-tuned with the same Leonardo HPC system with four NVIDIA Ampere A100-64 GPUs to ensure the runtime was comparable among them. The test datasets used for testing TED accuracies of all fine-tuning versions are the same and kept apart from the training.

| |

Runtime (s) |

Average Testing TED Accuracy |

Median Testing TED Accuracy |

Standard Deviation of Testing TED Accuracy |

| 600×800 |

38,715 |

0.607 |

0.629 |

0.254 |

| 960×1280 |

59,027 |

0.750 |

0.806 |

0.227 |

| 1200×1600 |

55,119 |

0.788 |

0.851 |

0.218 |

Table 4.

Runtime and TED accuracies of training from scratch and fine-tuning with images at a resolution of 1200×1600. Both approaches (training from scratch and fine-tuning) used the same test dataset and hyperparameters for the evaluation.

Table 4.

Runtime and TED accuracies of training from scratch and fine-tuning with images at a resolution of 1200×1600. Both approaches (training from scratch and fine-tuning) used the same test dataset and hyperparameters for the evaluation.

| |

Runtime (s) |

Validation TED accuracy |

Average Testing TED accuracy |

Median Testing TED accuracy |

Standard deviation of testing TED accuracy |

| Scratch Training |

54,729 |

0.697 |

0.181 |

0.202 |

0.110 |

| Fine-tuning |

55,119 |

0.929 |

0.788 |

0.851 |

0.218 |

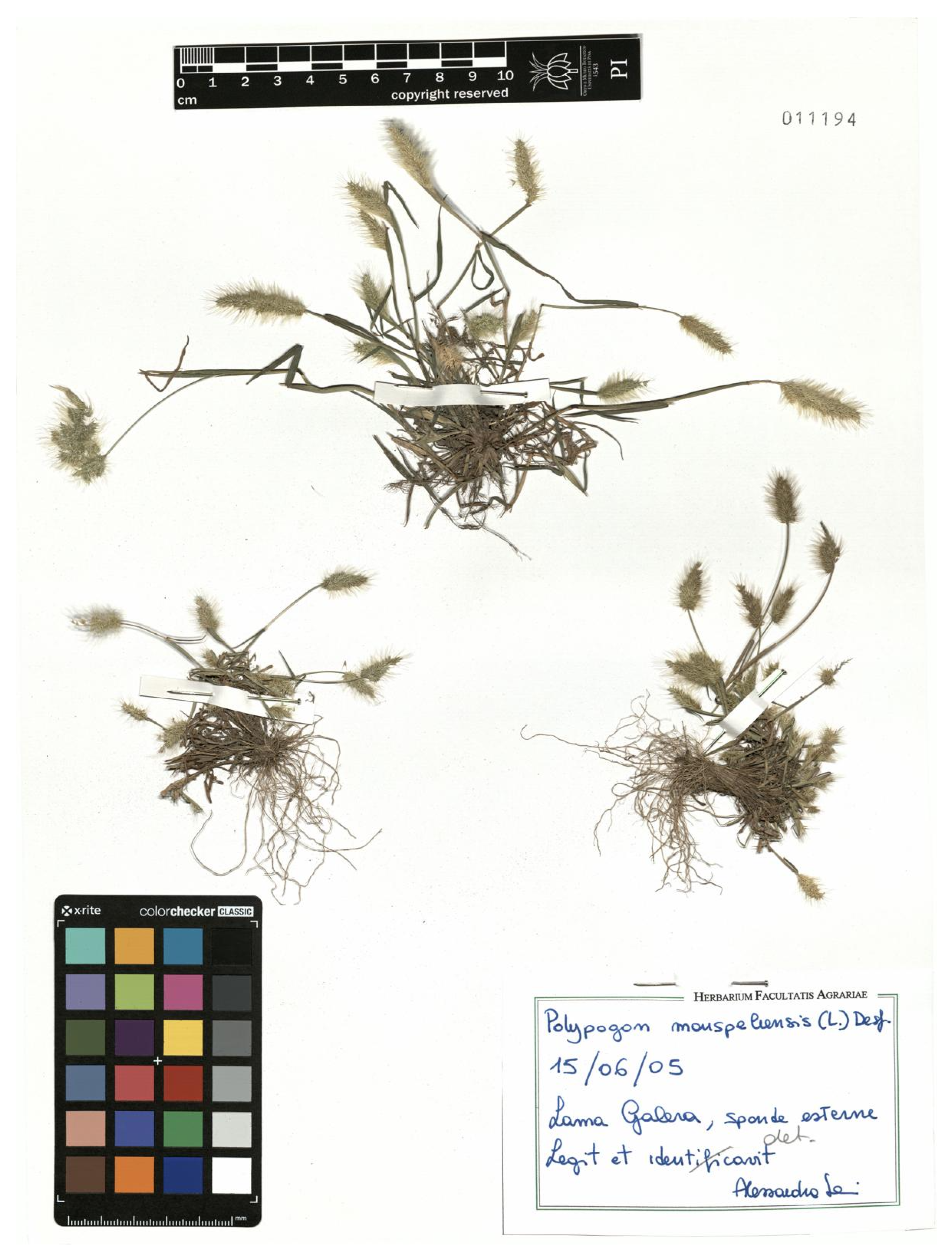

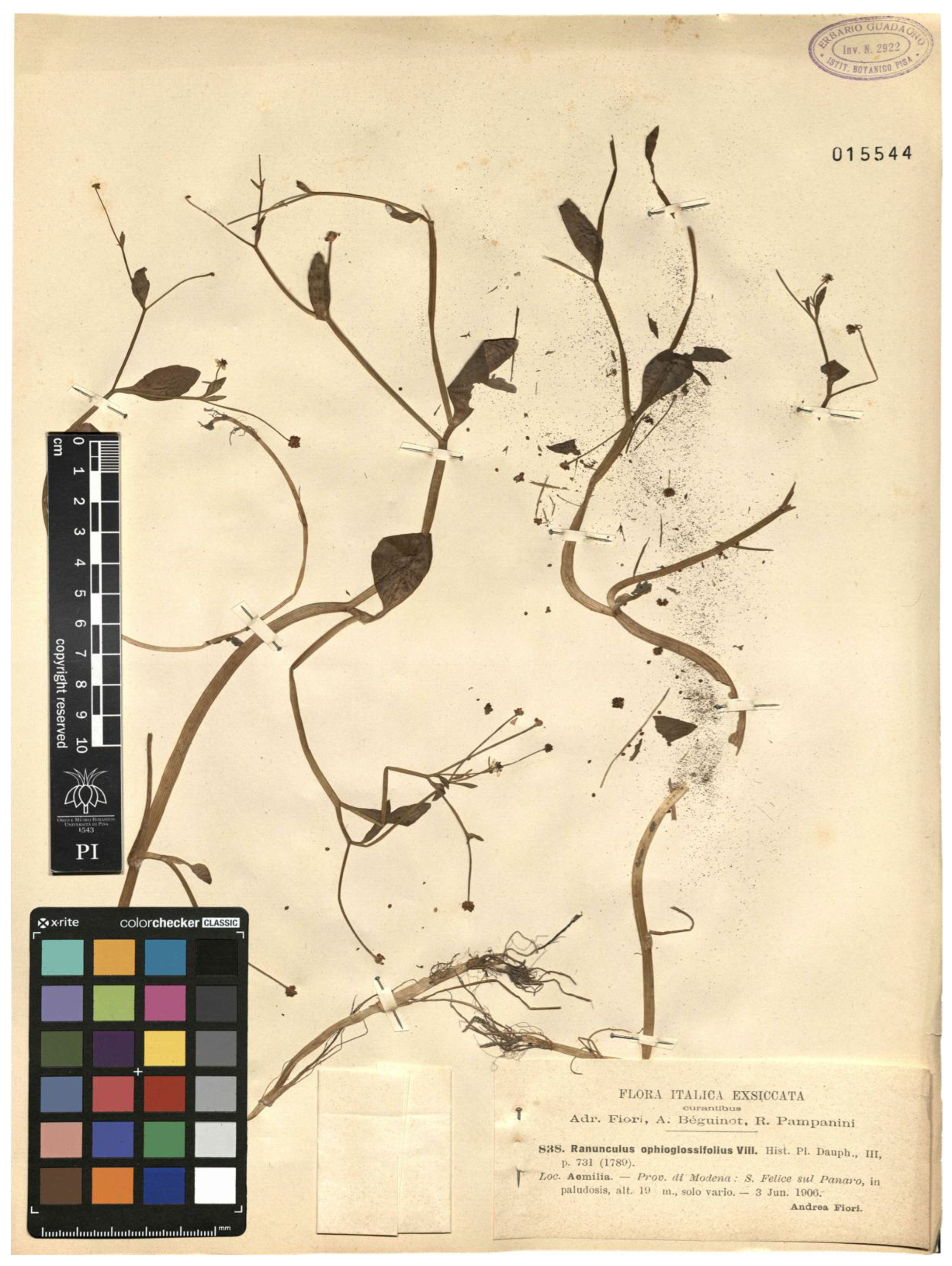

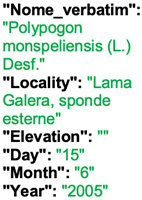

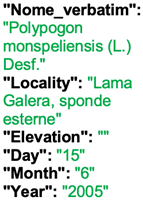

Table 5.

Recognition examples with zero scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Complex labels containing a lot of additional information, biased ground truth, and images containing more than one specimen produce the worst TED accuracy scores. However, these scores could sometimes be interpreted as “false negatives” (see text). In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

Table 5.

Recognition examples with zero scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Complex labels containing a lot of additional information, biased ground truth, and images containing more than one specimen produce the worst TED accuracy scores. However, these scores could sometimes be interpreted as “false negatives” (see text). In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

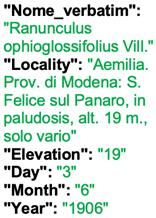

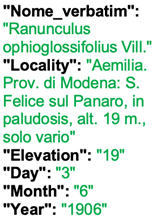

Table 6.

Recognition examples with low scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Images containing more than one label and untidy handwriting can produce poor TED accuracy scores. In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

Table 6.

Recognition examples with low scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Images containing more than one label and untidy handwriting can produce poor TED accuracy scores. In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

Table 7.

Recognition examples with high scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Labels containing minor additional information or special characters, and images containing tidy handwritings, normally result in quite good results in TED accuracy scores. In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

Table 7.

Recognition examples with high scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Labels containing minor additional information or special characters, and images containing tidy handwritings, normally result in quite good results in TED accuracy scores. In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

Table 8.

Recognition examples with full scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Specimen sheets with one label alone, hosting little to no additional information and very clean handwriting (or typewritten), normally result in very high TED accuracy scores. In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.

Table 8.

Recognition examples with full scores from the fine-tuned model with 1200×1600 images. Specimen sheets with one label alone, hosting little to no additional information and very clean handwriting (or typewritten), normally result in very high TED accuracy scores. In red, in which the ground truth and the prediction differ; in green, in which both match.