1. Introduction

This paper examines moral language in

Meta ad copy—the standardized textual fields (primary text, headline, description) that accompany images and videos in paid placements on Facebook and Instagram. Marketing has long leveraged affect to shape judgment and capture attention [

1,

2,

3]; neuroimaging shows reward- and emotion-related activation during consumer choice, consistent with hot–cold empathy gaps [

4] and with the vulnerability that bounded rationality creates for strategically crafted appeals [

5]. Beyond generic affect, moral language is distinctive: people routinely ascribe moral value to marketplace choices, and intuitionist accounts—rapid, affect-laden judgments followed by post hoc reasoning—explain why moral cues can be consequential [

6].

Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) provides a tractable framework for categorizing moral content into care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and purity/degradation [

7]. In an intuitionist view, moral judgments are not primarily the product of deliberation but arise from fast, affective appraisals that guide judgments of right and wrong; these intuitions coevolve with culture, yielding plural moral “channels” that communities weight differently [

6,

8]. In marketing contexts, messages can trigger these channels by appealing to (or violating) specific foundations, shaping evaluations and intentions; evidence links morally charged communication to shifts in consumer responses, particularly when appeals align with audience moral identities [

9,

10,

11,

12].

MFT is not the only lens for moralized persuasion. Value-based accounts (e.g., Schwartz’s basic human values) emphasize universal motivational goals that segment audiences by prioritized ends [

13,

14]; the norm-activation model (NAM) and the value–belief–norm (VBN) framework highlight the role of personal norms, awareness of consequences, and responsibility appraisals in prosocial and sustainability decisions [

15,

16,

17]. Dual-process work in moral judgment underscores the interaction of affective and controlled processes [

18]. Alternative theories propose different primitives: Morality-as-Cooperation grounds moral rules in solutions to recurrent cooperation problems [

19,

20,

21], whereas Dyadic Morality posits perceived harm as a central organizing construct [

22]. Identity-based accounts examine how

moral identity (internalization/symbolization) moderates responsiveness to moralized messages [

23]. We situate our study within this broader landscape but adopt MFT pragmatically because (i) it offers

operationally distinct, lexicon-mappable dimensions used in consumer research [

6,

8]; (ii) it generates audience-congruence predictions already validated in marketing and prosocial behavior [

9,

10]; and (iii) it aligns with available computational tools for large-scale text analysis [

24].

A key reason moralized persuasion may look different in advertising is

multimodality. Ad copy is brief and often subordinated to a central visual or audiovisual asset. Visual rhetoric suggests that text–image relations in ads are complementary, not redundant: text provides precision, while visuals activate emotions and cultural associations that amplify meaning [

25]. Images possess an intrinsic persuasive force and often elicit stronger affective responses than text alone [

26]; nevertheless, verbal information is indispensable for clarifying attributes and guiding inferences [

27]. Eye-tracking shows a division of labor: visuals capture initial attention, whereas textual elements—once fixated—receive longer reading and support more specific inferences [

28]. From a measurement standpoint, copy fields are standardized, exportable, and explicitly optimized by platforms and advertisers, making them a tractable locus for large-scale analysis even amid multimodality.

Platform governance further shapes moral expression. Meta’s review and policy systems restrict violent, discriminatory, or politically sensitive content [

29]. Simultaneously, the ad-delivery stack encourages multiple variants of primary text, headlines, and descriptions that are algorithmically recombined with different creatives to optimize outcomes [

30], and text quality predicts click-through and related metrics [

31]. In practice, marketers tune language to “fit” algorithms and policies, embedding

implicit moral cues that preserve resonance without triggering filters [

32].

Against this backdrop, we provide a descriptive map of moral and emotional language in Meta ad copy using MFT as the organizing framework. We assemble a cross-market corpus from the Meta Ad Library, focusing on leading global firms selected from established rankings with transparent, annually updated methodologies, and examine categories with heightened public-health and sustainability salience—alcohol and tobacco—given their regulatory scrutiny, responsibility messaging, and alignment with SDG 3 and SDG 12 [

33,

34]. Our analysis addresses three primary quantitative research questions: (RQ1) How are moral foundations distributed in Meta ad copy across brands? (RQ2) How does foundation usage differ within high-salience categories (alcoholic vs. non-alcoholic)? and (RQ3) To what extent do moral and sentiment-laden terms co-occur?

To make the complex labeling mechanics transparent, we supplement this corpus-level analysis with a fourth, qualitative objective: to conduct an expert-led "deep dive" into a representative subset of ad exemplars, illustrating the interplay of the unsupervised and supervised channels and the application of the consensus rules.

We conduct a descriptive (non-causal) analysis of

textual ad fields; moral signaling conveyed visually or auditorily is undercaptured. Platform policies likely suppress explicit moral language, biasing distributions toward implicit cues. Algorithmic recombination of copy–creative variants complicates precise alignment between text and served impressions. Text embedded in images, sarcasm/irony, and cross-language nuances may be missed or misclassified. Sampling leading global firms and focusing on alcohol/tobacco limits representativeness but targets economically salient actors under strong public-interest scrutiny; the covered time window further constrains generalizability. To preserve cohesion with the rest of the manuscript,

Materials and Methods details the Meta Ads Library data source (Graph API v23.0), brand and market sampling, text normalization, and the moral-language estimation pipeline (unsupervised SIMON and supervised classifiers, consensus rules, confidence index, and purity diagnostics).

Results reports foundation-level distributions, co-occurrence patterns of moral and emotional terms, and sensitivity checks—without inferring causal effectiveness.

Discussion interprets these descriptive patterns in light of multimodal creative, policy filtering, and algorithmic optimization, articulates domain-specific limitations (including ongoing debates around MFT dimensionality and discriminant validity [

8]) and outlines implications for future multimodal and multilingual work.

Conclusions summarizes the main takeaways and delineates avenues for subsequent research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Sampling Frame

We assembled a multi-market corpus of brand advertising messages retrieved from Meta’s Ads Library via the Graph API (v23.0). The corpus covers seven global beverage brands—Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Red Bull, Heineken, Hennessy, Nescafé, and Corona—across eight English-speaking markets: United States, Great Britain (GB), Ireland (IE), Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Singapore.

Brand selection followed the 2025

Forbes Global 2000 list (Food, Drink, and Tobacco)

1 and a focus on multinational beverage firms with high consumer visibility and policy relevance. For RQ2 we contrasted

alcoholic (

Heineken,

Hennessy,

Corona) versus

non-alcoholic (

Coca-Cola,

Pepsi,

Red Bull,

Nescafé) categories given regulatory salience and responsibility messaging.

Because disclosure rules vary by country, harvesting proceeded in two stages. First, in GB and IE—where comprehensive archive search is available—we discovered official brand pages using disjunctive queries (for example, “Coca-Cola” OR “Coke”) and retained candidates containing brand tokens, bounded by a minimum delivery date of 1 January 2021. We appended a curated list of verified page IDs to mitigate recall gaps. Second, we projected discovered IDs to the other English-language markets and retrieved ads with a uniform field set: unique identifiers; creation and delivery timestamps; text fields and creative snapshot URL; language and platform metadata; impression and spend bounds (lower/upper/average where available); demographic and geographic delivery aggregates; and bylines.

For cross-country consistency, we respected the API constraint on ad_type: ALL in GB/IE and POLITICAL_AND_ISSUE_ADS elsewhere, with graceful fallback if unsupported. Because this can bias the pool toward issue ads outside GB/IE, we present GB+IE as a commercial benchmark and either stratify or cautiously pool other markets. The primary analysis window is 1 January 2021 through 15 October 2025; legacy creatives earlier than 2021 are included only when required by archive constraints and are flagged in robustness checks.

Ads with multiple text bodies were exploded so that each body constituted a distinct observation linked to its parent ad. The resulting analysis variable underwent Unicode NFKC folding and whitespace compaction. The final dataset contains text bodies and serves as the basis for all quantitative analyses (RQ1–RQ3). Data are public, aggregated, and non-personal; no sensitive attributes were accessed or inferred.

2.2. Depuration and Normalization

Prior to each run we removed residual outputs from previous executions to prevent contamination. Normalization preserved lexical content while harmonizing diacritics and spacing (for example, “Nescafé” → “Nescafe”). We retained analytic variables (normalized text, identifiers, timestamps, delivery metadata) and deduplicated at both the parent-ad and text-body levels.

2.3. Moral Language Estimation

We operationalized Moral Foundations Theory (care, fairness, loyalty, authority, purity) using the

moralstrength library [

24]. Two complementary estimators were employed: an unsupervised semantic similarity model (SIMON) and a lexicon-based supervised estimator. Where applicable, we pinned dictionary resources to their latest available release to stabilize vocabulary coverage.

2.3.1. Unsupervised Estimator (SIMON)

For each text

t and foundation

f, SIMON computes the cosine similarity

with

. For interpretability we rescale to a 0–10 metric:

We summarize SIMON by the maximum score and the winning margin

and record the argmax label

.

2.3.2. Supervised Estimator

The supervised channel is a lexicon-based unigram+count estimator that maps foundation-specific dictionary evidence to calibrated probabilities

. Let

denote the score for foundation

f under model

m; the primary model is

. We summarize by

and record

. Probability scores are used only for ranking, thresholding, and correlation analyses; no downstream causal inference is attempted.

2.4. Consensus Rules and Label Assignment

To prioritize precision, we assign a high-confidence label only when the two channels agree at sufficient confidence. With thresholds chosen a priori to favor precision over recall and varied in sensitivity checks,

the consensus indicator is

We flag potential ambiguity when either channel exhibits a small winning margin. Using a common 0–1 scale for comparison, let

. With

,

A confidence index combines the channels on a common 0–1 metric:

2.5. Purity Diagnostic

To detect potential misclassification of marketing claims related to cleanliness or formulation (for example, “clean,” “zero sugar”), we compute a non-overriding diagnostic

where

matches a curated term list. This flag supports sensitivity analyses and does not alter labels.

2.6. Moral–Sentiment Co-Occurrence (RQ3)

We first evaluated the NRC Emotion Lexicon, which yielded no matches in this corpus. As an alternative suited to short, informal text, we used VADER [

35]. For each text

t, VADER outputs positive, negative, and neutral scores and a normalized compound score

. These metrics are related to moral estimates through non-parametric association measures (

Section 2.7).

2.7. Analytical Strategy, Weighting, and Inference

Analyses are descriptive and aligned with the three research questions. After exploding creatives, each text body is one observation linked to its parent ad. Unless stated otherwise, estimates use the full corpus of text bodies pooled across markets; for interpretability we also report summaries on the high-confidence subset where .

For RQ1, we tabulate brand-level distributions over the label space care, fairness, loyalty, authority, purity, or non–moral using the final label . For RQ2, we aggregate labels to alcoholic versus non-alcoholic categories. For RQ3, we compute Spearman rank correlations between continuous foundation scores and VADER polarity metrics (compound, positive, negative). Correlations are computed pairwise with listwise omission of non-finite values. Where p-values are reported, we control the false discovery rate across families of tests using Benjamini–Hochberg at .

Weighting reflects data availability and platform constraints. Primary estimates are unweighted at the text-body level to maintain transparency given heterogeneous disclosure across markets. As a robustness check, where impression or spend bounds are exposed, we use midpoint values of the reported lower/upper bounds as analytic weights; observations without bounds receive unit weight. Because copy–creative mixing can decouple text from served impressions, weighted results are presented as sensitivity checks.

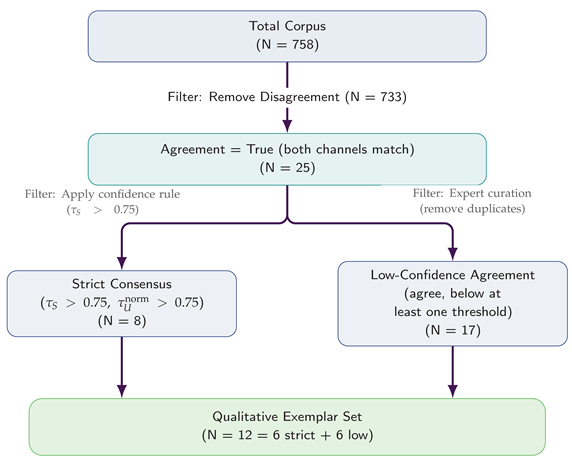

2.8. Qualitative Exemplar Selection ()

From the full corpus, we removed items where the channels disagreed on the top foundation (

; Disagreement). The remaining

cases exhibited inter-model agreement and were partitioned into Strict Consensus (

; Eq.

6) and Low-Confidence Agreement (

). Manual review identified near-duplicates; a subject-matter expert curated a balanced exemplar set of

texts comprising 6 Strict-Consensus and 6 Low-Confidence items for qualitative analysis.

2.9. Validation, Governance, and Reproducibility

HTTP requests handled 429/5xx responses with exponential backoff; pagination continued until exhaustion or a configured limit. We persisted intermediate artifacts (discovered page IDs and the final ads table). Each run began by dropping prior unsupervised outputs, model-suffixed columns, and derived flags to prevent leakage across experiments. All thresholds were set a priori and varied in sensitivity analyses. Analytic code recorded software versions and random seeds; results are reproducible from the provided scripts and configuration files. Grammar tools such as Grammarly and Generative AI assisted only with language polishing and document structure, and were not used for data collection, modeling, or statistical estimation.

2.10. Ethics and Data Availability

The study uses public, aggregate advertising data and does not involve human subjects research as defined by institutional policy; no personal data were processed. Data-collection scripts and derived data sufficient for replication are provided, subject to platform terms, together with instructions for recreating the corpus from the Ads Library.

3. Results

3.1. Model Calibration and Consensus

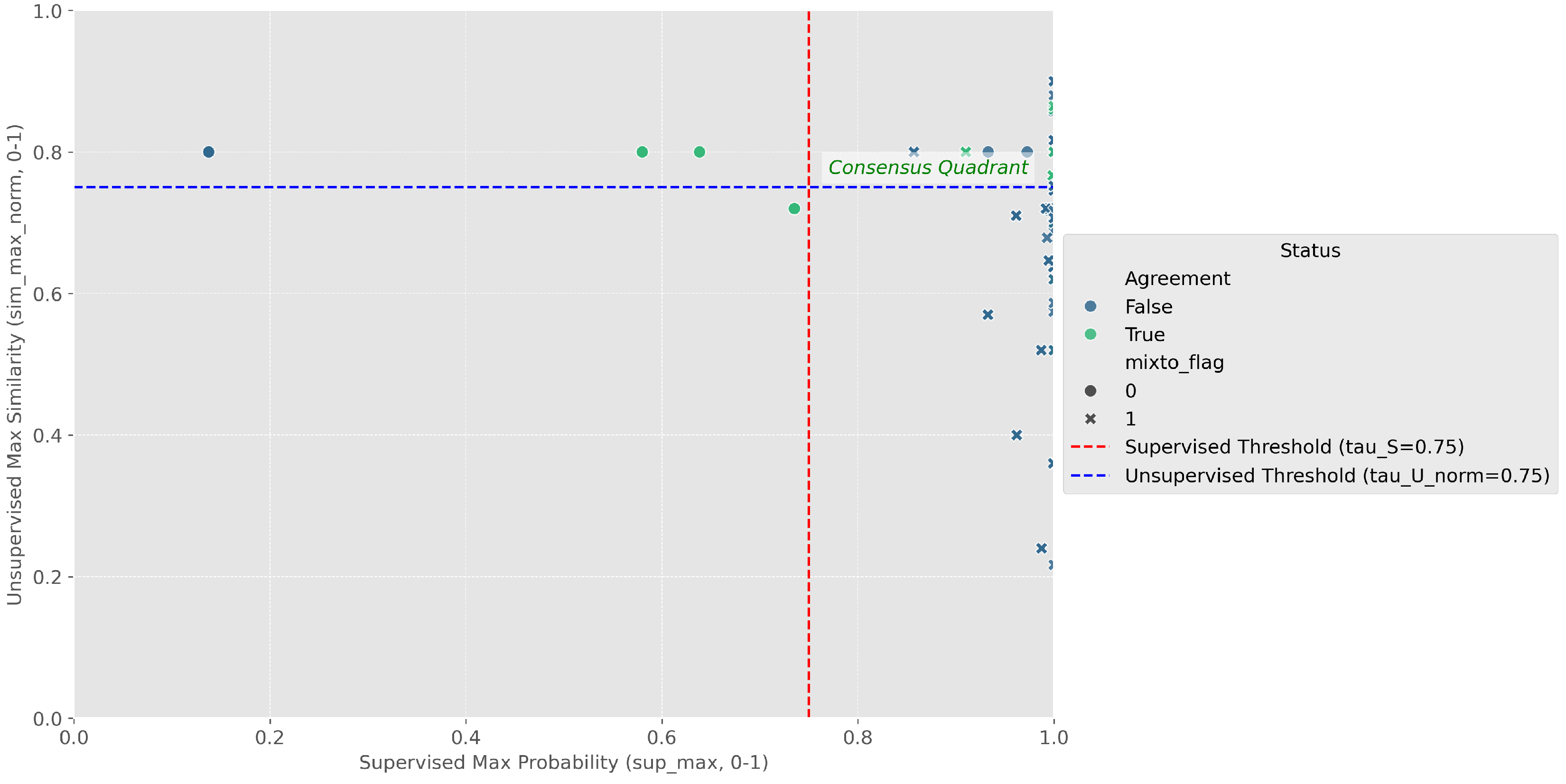

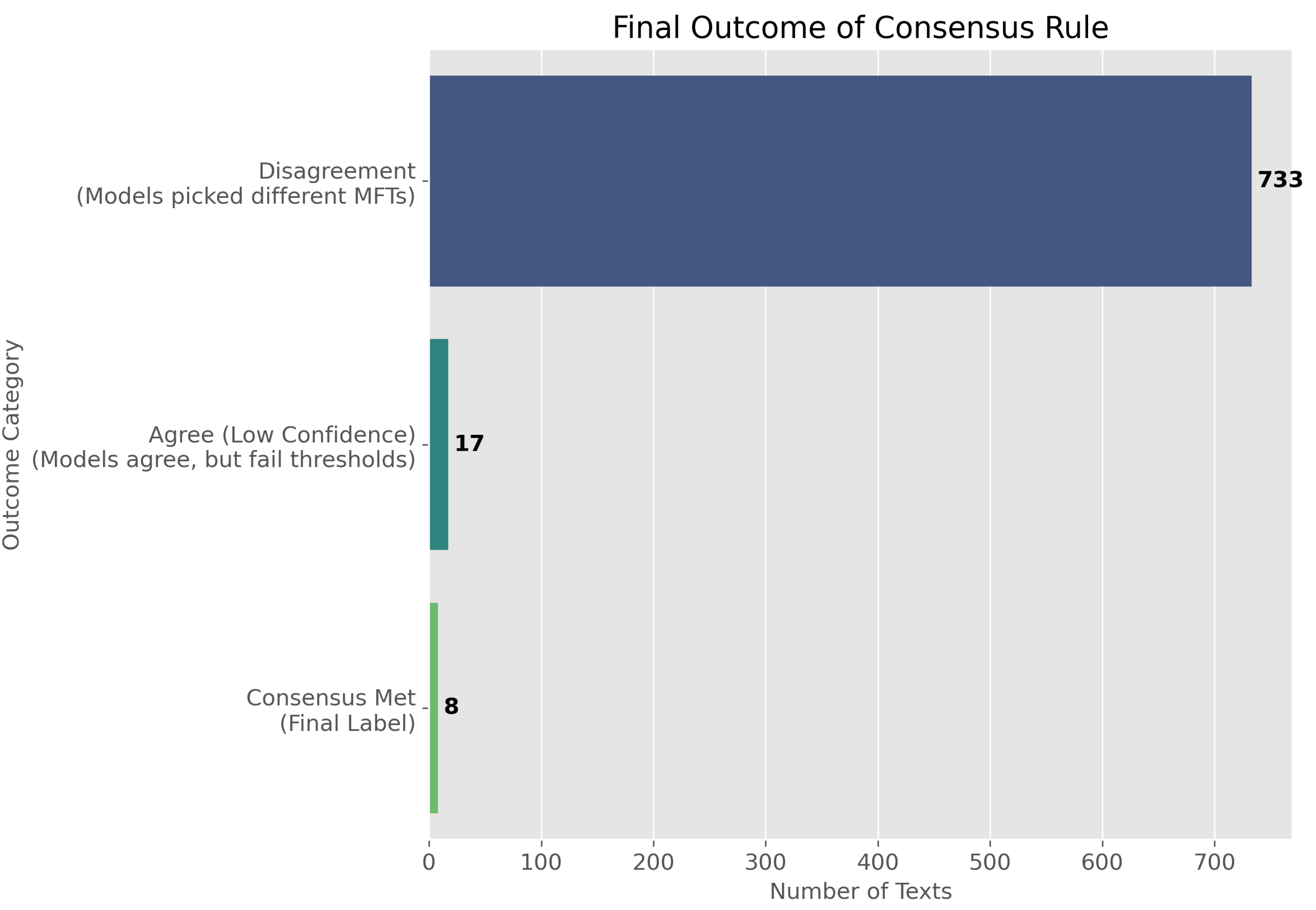

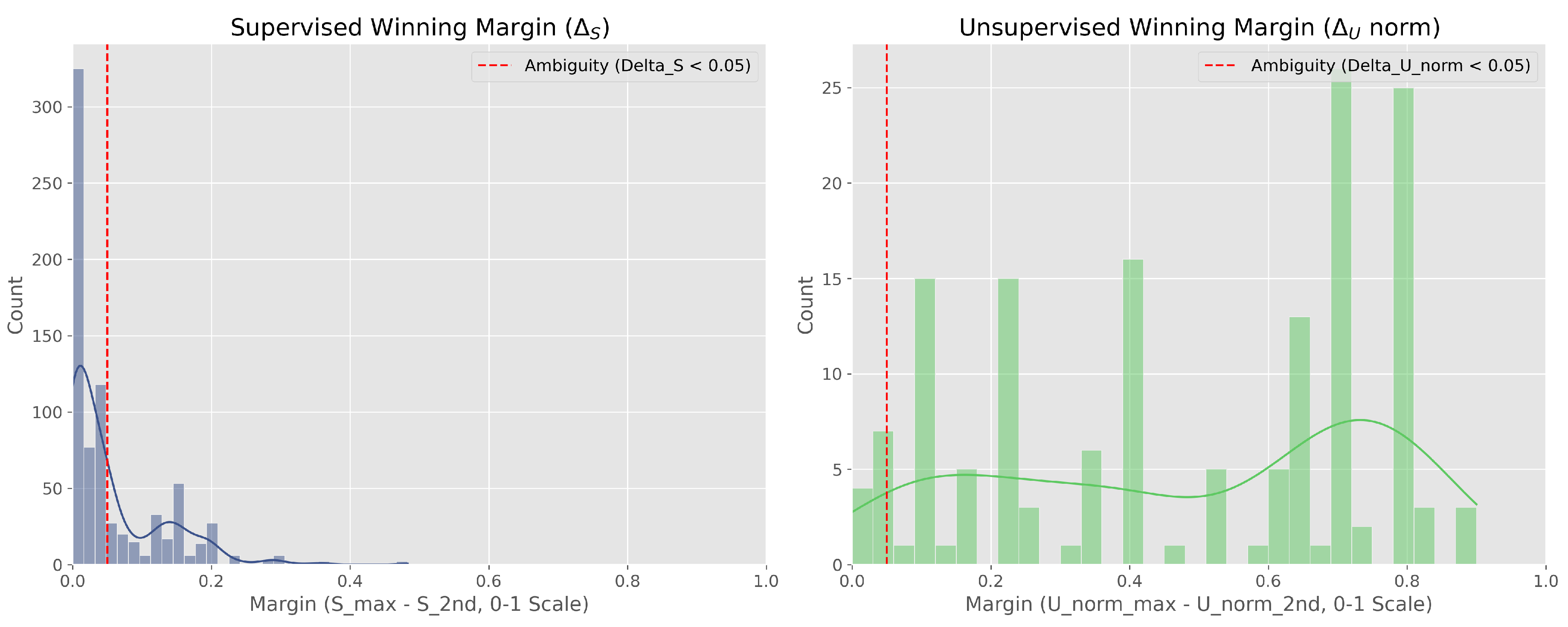

To assess the reliability of moral labels produced by our two-channel pipeline (a supervised lexical classifier and an unsupervised semantic matcher), we calibrated agreement, confidence, and ambiguity, and used these diagnostics to define a conservative selection funnel (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Figure 1 plots the full corpus (N=758) in the confidence–confidence plane: the x-axis is the supervised model’s maximum predicted probability (

sup_max) and the y-axis is the normalized unsupervised similarity to the best-matching foundation (

sim_max_norm). The upper-right “Consensus Quadrant” encodes our gold-standard rule (

and

). Point color indicates whether both channels selected the same top foundation (yellow,

Agreement=True) or not (purple,

Agreement=False).

Figure 2 quantifies these outcomes. Most texts fall into

Disagreement (N=733, 96.7%), while only N=25 texts (3.3%) exhibit channel agreement. Of the agreed cases,

Consensus Met (N=8, 1.1%) satisfy the high-confidence rule (inside the quadrant), and

Agree (Low Confidence) (N=17, 2.2%) agree but fail one or both thresholds.

Finally,

Figure 3 diagnoses ambiguity via the “winning margin”

, defined as the gap between the highest and second-highest foundation score within each channel. The supervised lexical model (left,

) is highly decisive, with margins concentrated near 1.0. In contrast, the unsupervised semantic model (right,

) is the main source of ambiguity, with a prominent cluster below

(near-ties).

The agreement subset, consisting of 25 advertisements, represents the high-precision segment of the corpus used for qualitative inspection. Within this group, the most reliable references—termed the Consensus Met core—comprise eight cases where both the supervised and unsupervised estimators converge with strong confidence. Most observed disagreements arise from semantic near-ties between foundations, which validates our decision to require both estimator agreement and high confidence as conditions for final label assignment. The remaining cases categorized as Agree (Low Confidence) can be included in robustness checks to expand coverage, although their interpretive reliability is limited and they should therefore be treated with appropriate caution.

3.2. RQ1: Distribution of Moral Foundations in the Full Corpus

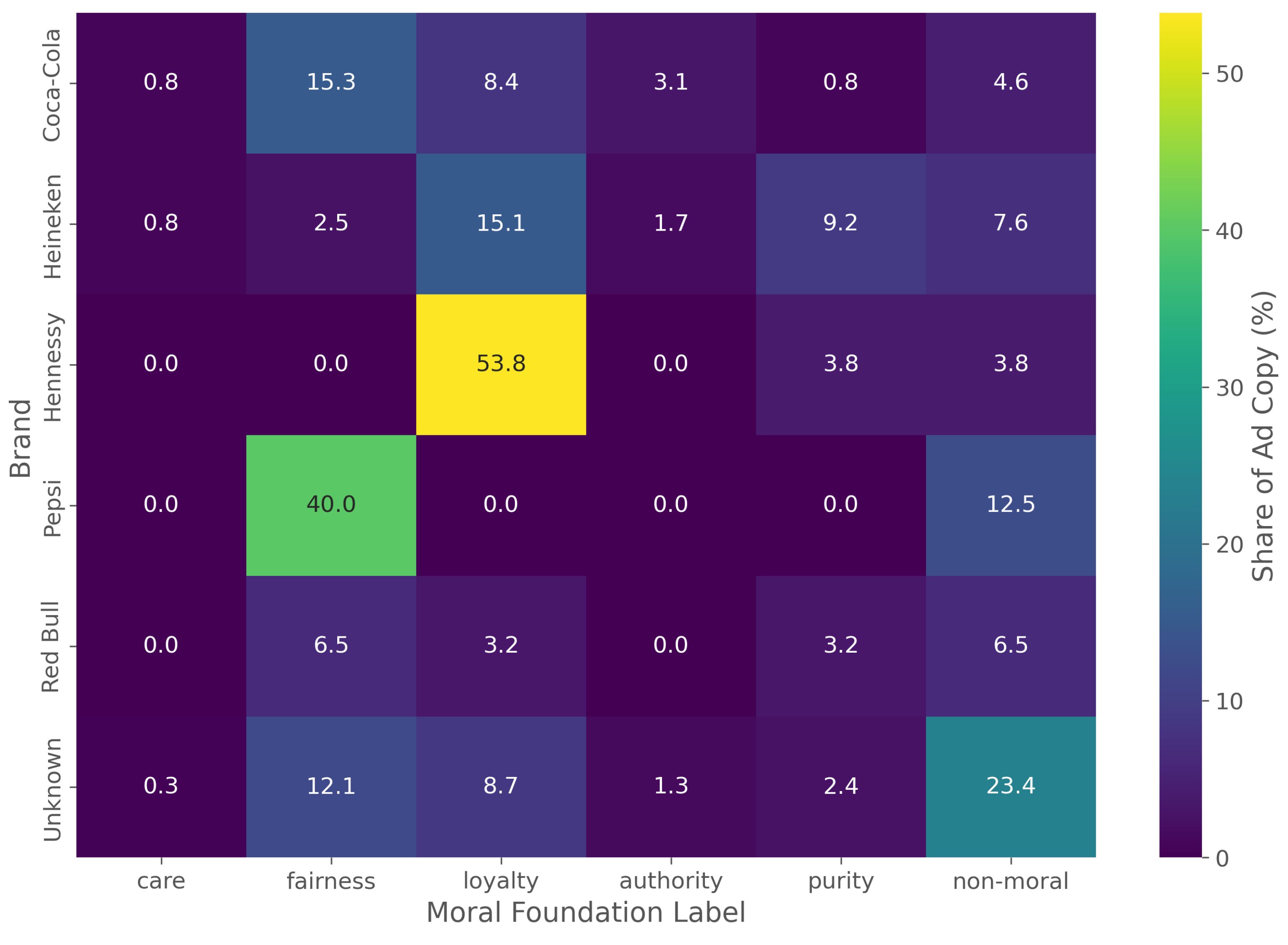

We first analyze the distribution of final moral labels across the full 758-item corpus. The heatmap in

Figure 4 and the detailed percentages in

Table 1 reveal distinct brand-level strategies.

Brands show clear preferences: Hennessy’s messaging is overwhelmingly dominated by loyalty (53.85%), and Pepsi’s by fairness (40.00%). Other brands show a more diverse moral palette; Coca-Cola utilizes both loyalty (20.61%) and fairness (15.27%), while Heineken also leans on loyalty (16.81%) but adds significant use of purity (9.24%). The "Unknown" category, which contains ads where a brand could not be inferred, has the largest share of non-moral text (23.42%), as expected for ads lacking clear brand identifiers.

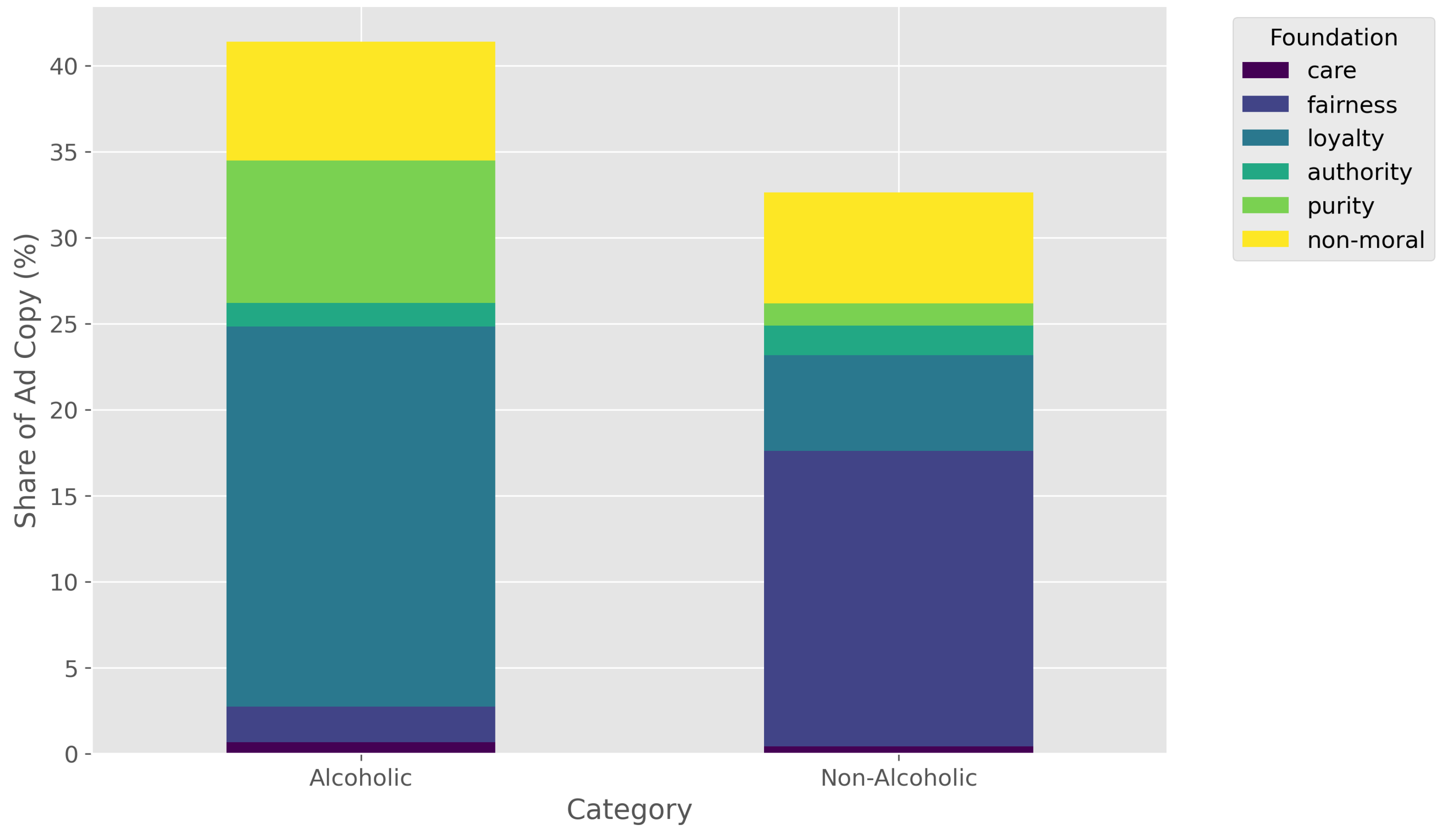

3.3. Category Contrast (Alcoholic vs. Non-Alcoholic)

Aggregating brands into ’Alcoholic’ and ’Non-Alcoholic’ categories reveals a clear divergence in moral framing, as shown in

Figure 5 and

Table 2.

A stark contrast emerges: the Alcoholic category (e.g., Heineken, Hennessy) most frequently employs loyalty (23.45%) and purity (8.28%). This suggests a focus on in-group identity, heritage, and the quality or integrity of the product.

Conversely, the Non-Alcoholic category (e.g., Coca-Cola, Pepsi) heavily favors fairness (17.17%) and, to a lesser extent, loyalty (12.45%). This framing aligns with messages of social justice, equality, and community engagement, which are common themes in their corporate social responsibility campaigns.

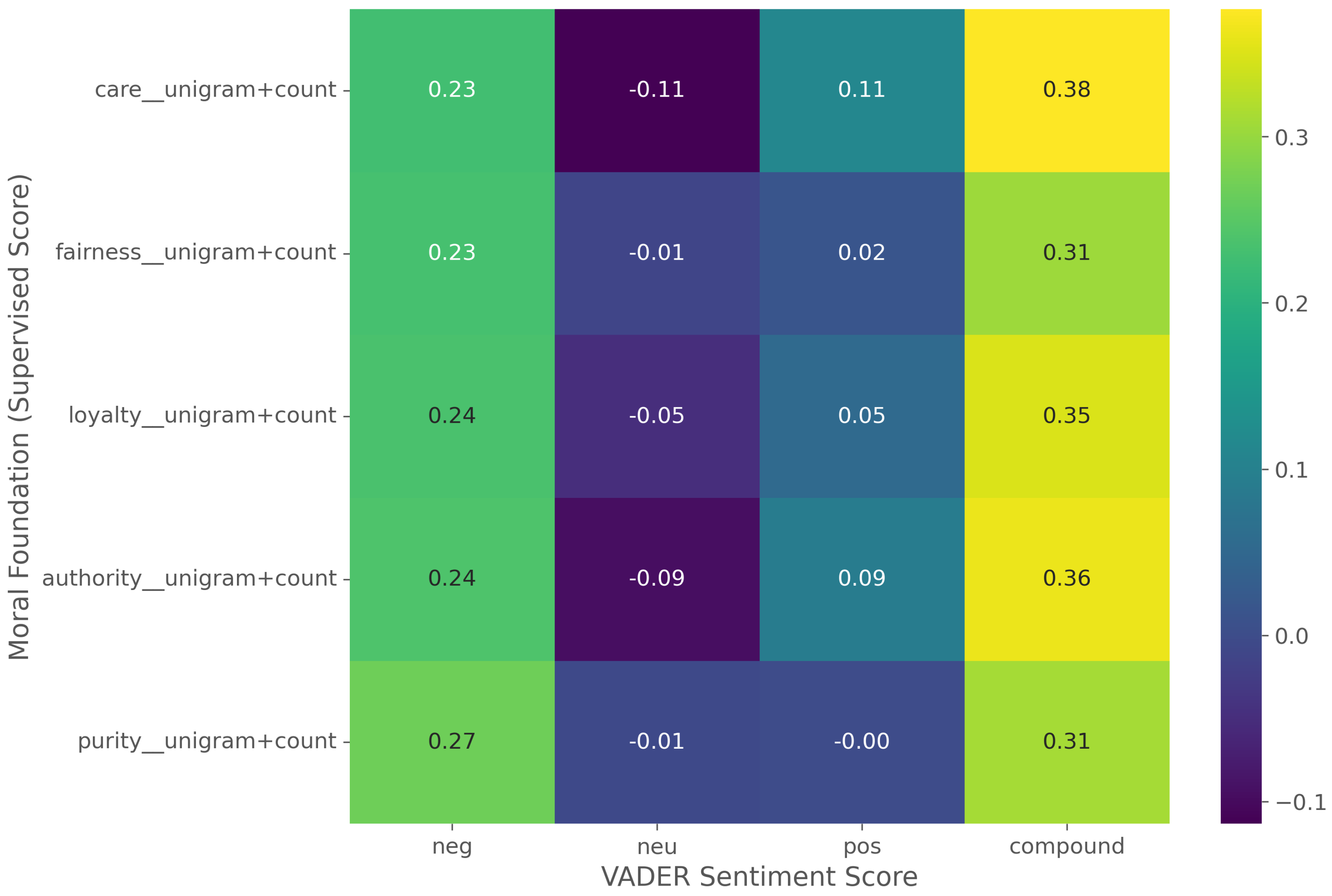

3.4. RQ3: Moral-Sentiment Co-Occurrence

To answer RQ3, we assessed the co-occurrence of moral language with emotional sentiment. An initial pass using the NRC Emotion Lexicon (nrclex) yielded no matches, indicating its lexicon has poor coverage for our ad copy corpus. As a robust alternative, we used VADER to calculate sentiment polarity scores and computed the Spearman’s rank correlation () between these scores and our supervised moral foundation scores.

The results (

Figure 6) reveal a distinct pattern of affective intensity. All five moral foundations show a moderate, positive correlation with VADER’s compound sentiment score (e.g.,

Care ;

Authority). This suggests that moralized text is significantly more emotionally charged than non-moral text.

However, a decomposition of the sentiment channels reveals that this intensity is primarily driven by negative vocabulary. Contrary to expectation, the correlation with the negative sentiment score (e.g., Purity ; Loyalty) is consistently stronger than the correlation with the positive score (e.g., Purity; Loyalty). This indicates that while the overall message (Compound) may be persuasive or constructive, the specific moral vocabulary employed is frequently rooted in the description of violations, problems, or threats.

3.5. Illustrative Exemplars and Decision Mechanics

To illustrate the labeling pipeline in practice, we selected a subset of twelve advertisements (t1–t12) for a qualitative "deep dive" (

Table 3). These items span both alcoholic and non-alcoholic brands and include multiple creative styles (promotions, corporate news, responsibility messaging).

For each text, we estimated foundation scores using both the unsupervised SIMON model and the supervised classifiers (

Table 5). The final label was assigned using the consensus rule (Eq.

6) from our method. Table reports the metrics and final decisions for this subset.

Table 6.

Summary of the label-decision metrics for each advertisement

based on Equation (

6). All exemplars (

–

) are shown.

Table 6.

Summary of the label-decision metrics for each advertisement

based on Equation (

6). All exemplars (

–

) are shown.

| ID |

|

|

|

|

|

Moral label |

| t1 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

5.200 |

5.200 |

0.000 |

loyalty |

| t2 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

6.200 |

6.200 |

0.000 |

loyalty |

| t3 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

6.375 |

6.375 |

0.000 |

loyalty |

| t4 |

0.735 |

0.154 |

7.200 |

7.200 |

0.154 |

loyalty |

| t5 |

0.638 |

0.361 |

8.000 |

8.000 |

0.361 |

authority |

| t6 |

0.580 |

0.229 |

8.000 |

8.000 |

0.229 |

authority |

| t7 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

7.000 |

0.600 |

0.000 |

mixed |

| t8 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

8.000 |

8.000 |

0.000 |

purity |

| t9 |

0.910 |

0.029 |

8.000 |

8.000 |

0.029 |

purity |

| t10 |

0.999 |

0.001 |

7.667 |

0.500 |

0.001 |

purity |

| t11 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

8.600 |

1.800 |

0.000 |

care |

| t12 |

1.000 |

0.000 |

8.648 |

0.814 |

0.000 |

care |

In this illustrative set, all twelve items satisfied the strong consensus rule. The resulting labels show loyalty and purity as dominant, with care appearing in two cases (t11, t12). This subset also allows us to see the diagnostic rules in action. For example, several rows (e.g., t1, t3, t4) exhibit supervised ties () but are not flagged as mixed because the strong cross-channel consensus rule takes precedence. This confirms the value of the two-channel approach over a simpler supervised-only model.

5. Conclusions

This paper mapped how brands mobilize moral language in Meta ad copy using a two–channel Moral Foundations framework. Treating foundations as operational, lexicon–mappable dimensions, we combined an unsupervised semantic estimator (SIMON) with supervised classifiers and enforced a strict consensus rule, complemented by a purity diagnostic. The resulting labels reveal patterned, brand– and category–specific use of moral cues—most visibly in loyalty, fairness, and purity frames—while also showing that much ad text is either non–moral or too ambiguous for confident classification. Together with the valence–oriented sentiment pass, these findings support an intuitionist view of moralized persuasion in paid social while remaining descriptive and non–causal by design.

Methodologically, the study underscores that ad copy is strategic, multimodal, and platform–governed: visuals carry a substantial share of affect; policies suppress overtly polarizing language; and algorithmic recombination pairs copy with creatives in ways a text–only pipeline cannot fully capture. Future work should therefore (i) integrate visuals with text via multimodal encoders, (ii) align analyses to copy–creative variant mixing and text–strength signals, (iii) incorporate impression/spend weighting where available, and (iv) extend sampling beyond English and beverages to test cross–cultural and sectoral generality. By releasing transparent rules and emphasizing reproducibility, this paper offers a tractable baseline for studying moral communication in digital advertising and a roadmap for building domain–sensitive, multimodal measurement that links moral cues, platform constraints, and audience–congruent messaging at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C-F. (marketing framing and brand/category selection), D.V-C. (psychological theory and constructs), and L.T-S. (computational study design); methodology, L.T-S. (pipeline design, thresholds, consensus rules) and D.V-C. (construct operationalization and validity checks); software, L.T-S.; validation, D.V-C. (content/construct validity) and L.T-S. (technical validation); formal analysis, L.T-S. (primary) with interpretive support from D.V-C.; investigation, M.C-F. (industry/platform context), L.T-S. (data collection via API and preprocessing), and D.V-C. (case review and coding guidance); resources, M.C-F. (brand/market inputs) and L.T-S. (API access and tooling); data curation, L.T-S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T-S. (Methods/Results), M.C-F. (Introduction/Discussion—marketing perspective), and D.V-C. (Theoretical background/Discussion—psychology perspective); writing—review and editing, M.C-F., L.T-S., and D.V-C.; visualization, L.T-S.; supervision, M.C-F. (lead) and D.V-C. (theoretical oversight); project administration, M.C-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.