Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

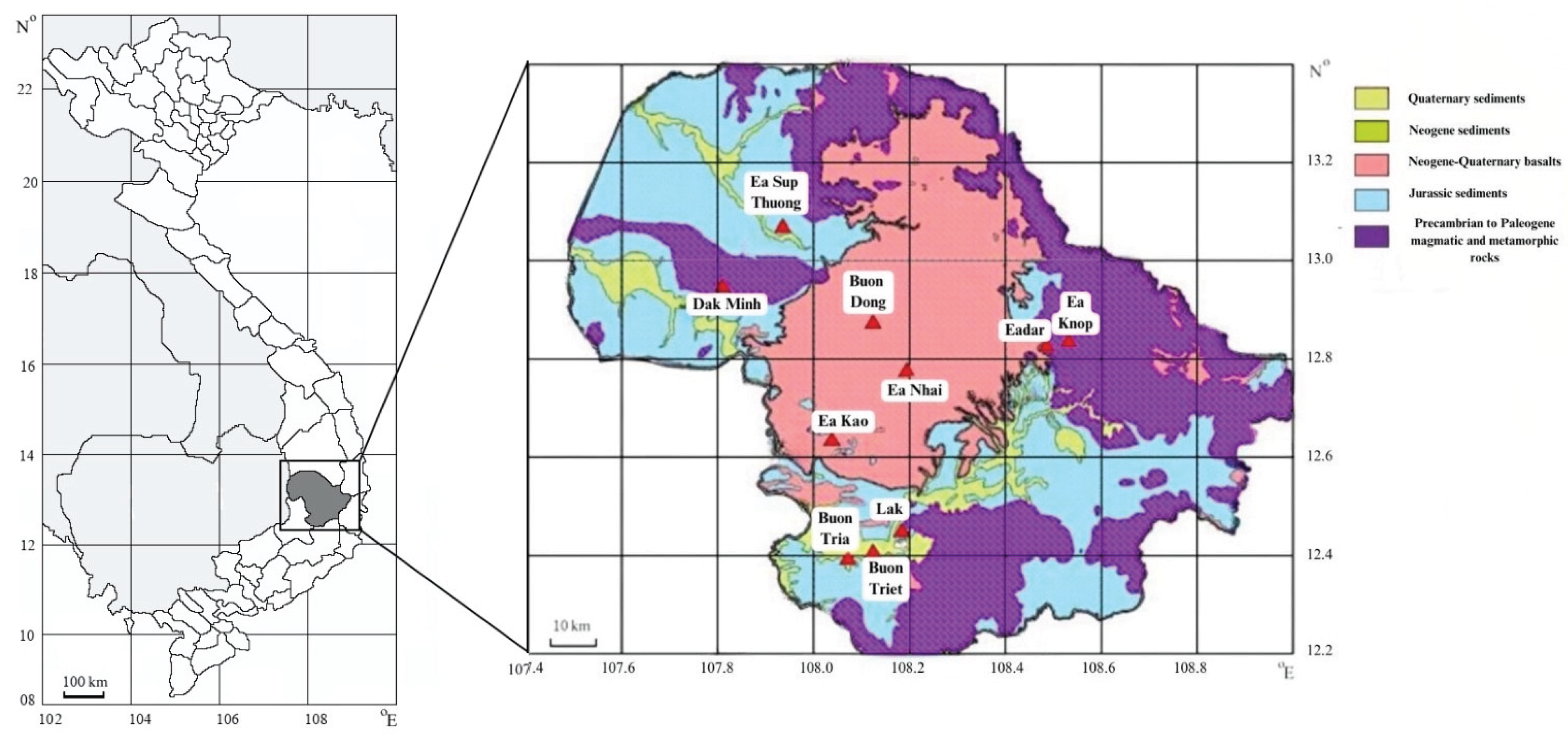

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Laboratory Analyses

2.4. Calculation of the Enrichment Factor

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Lake Bottom Sediment Characteristics

3.2. Abundance and Risk Assessment

3.3. Geochemical Indicators

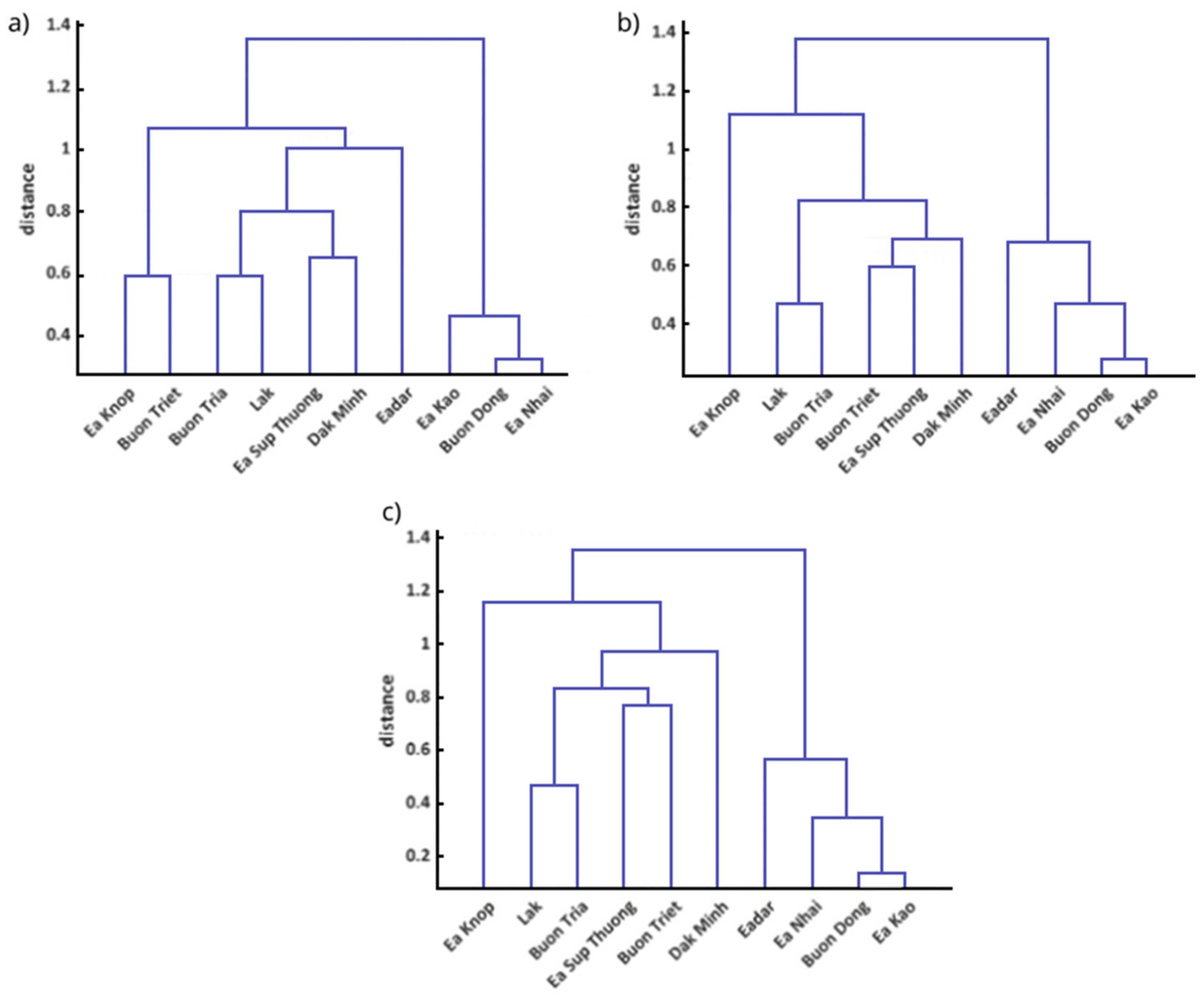

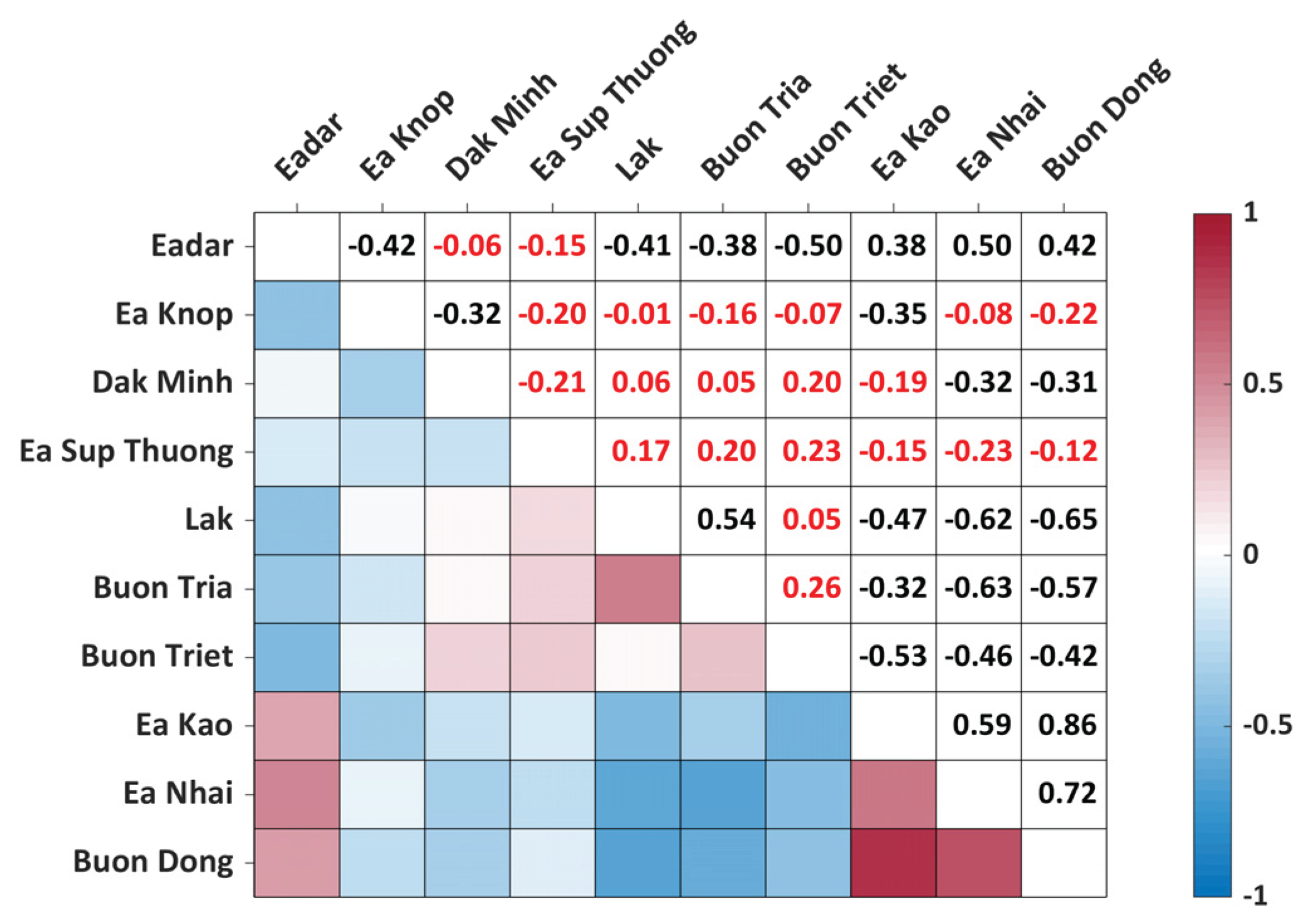

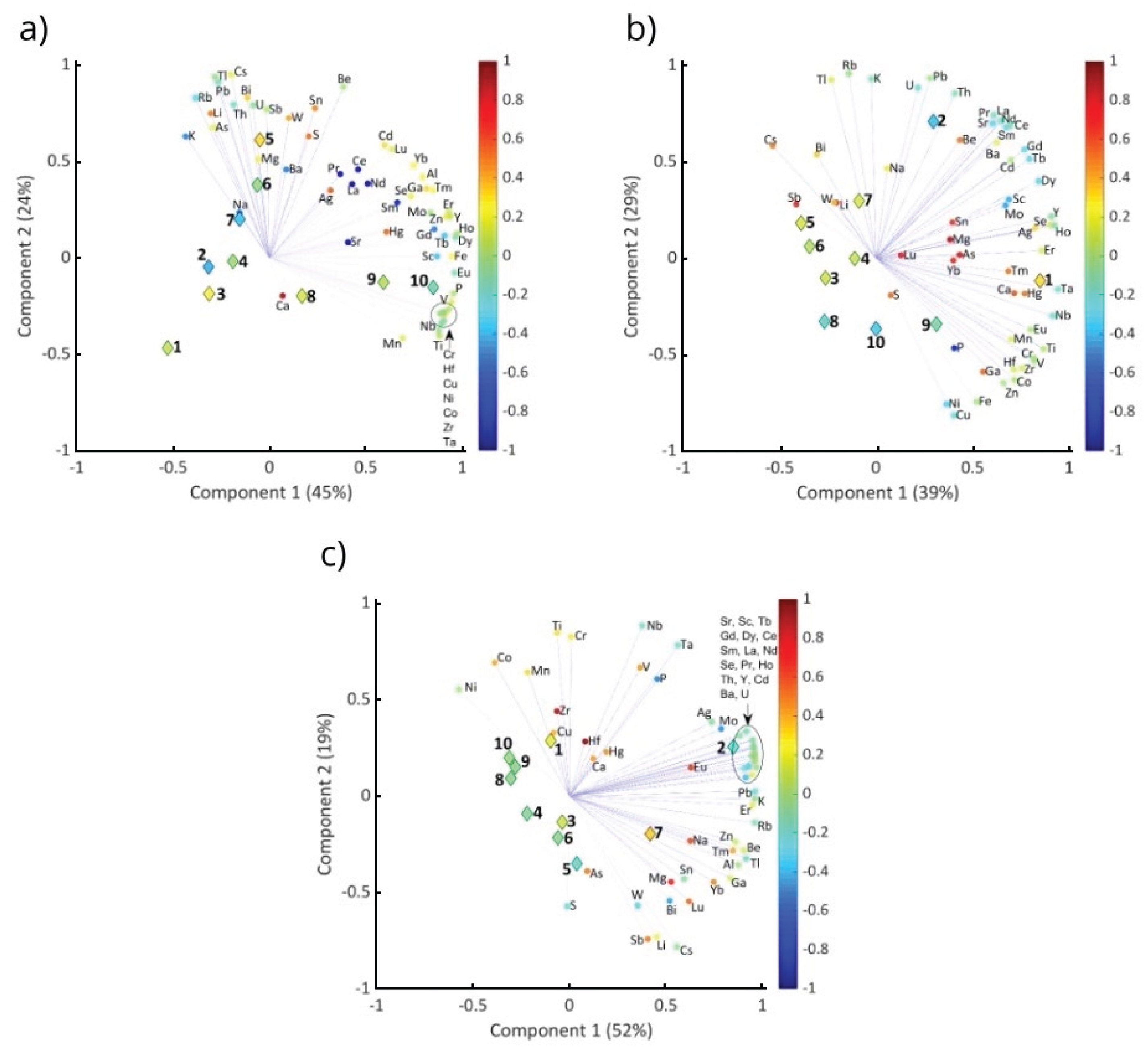

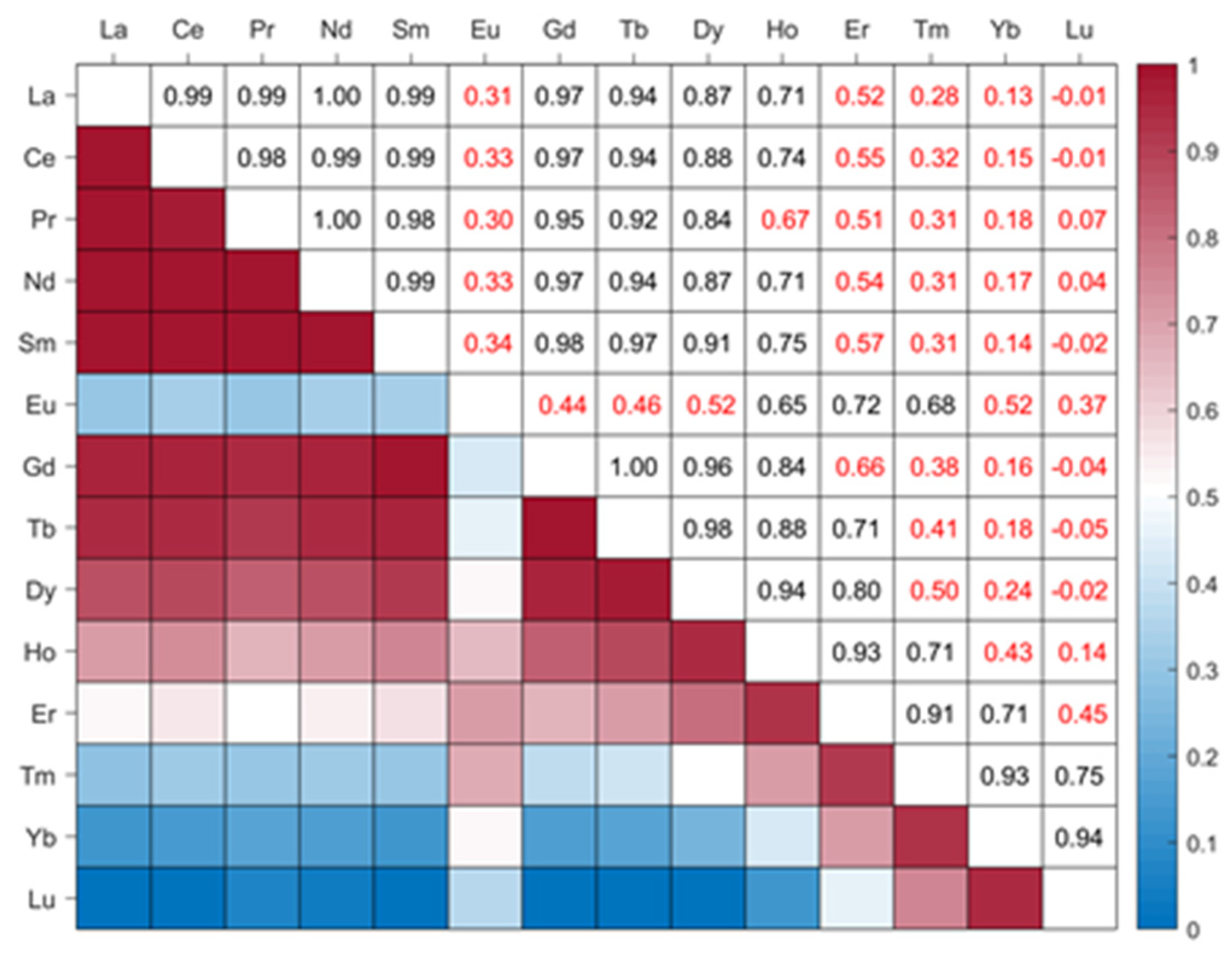

3.4. Multivariate Analyses

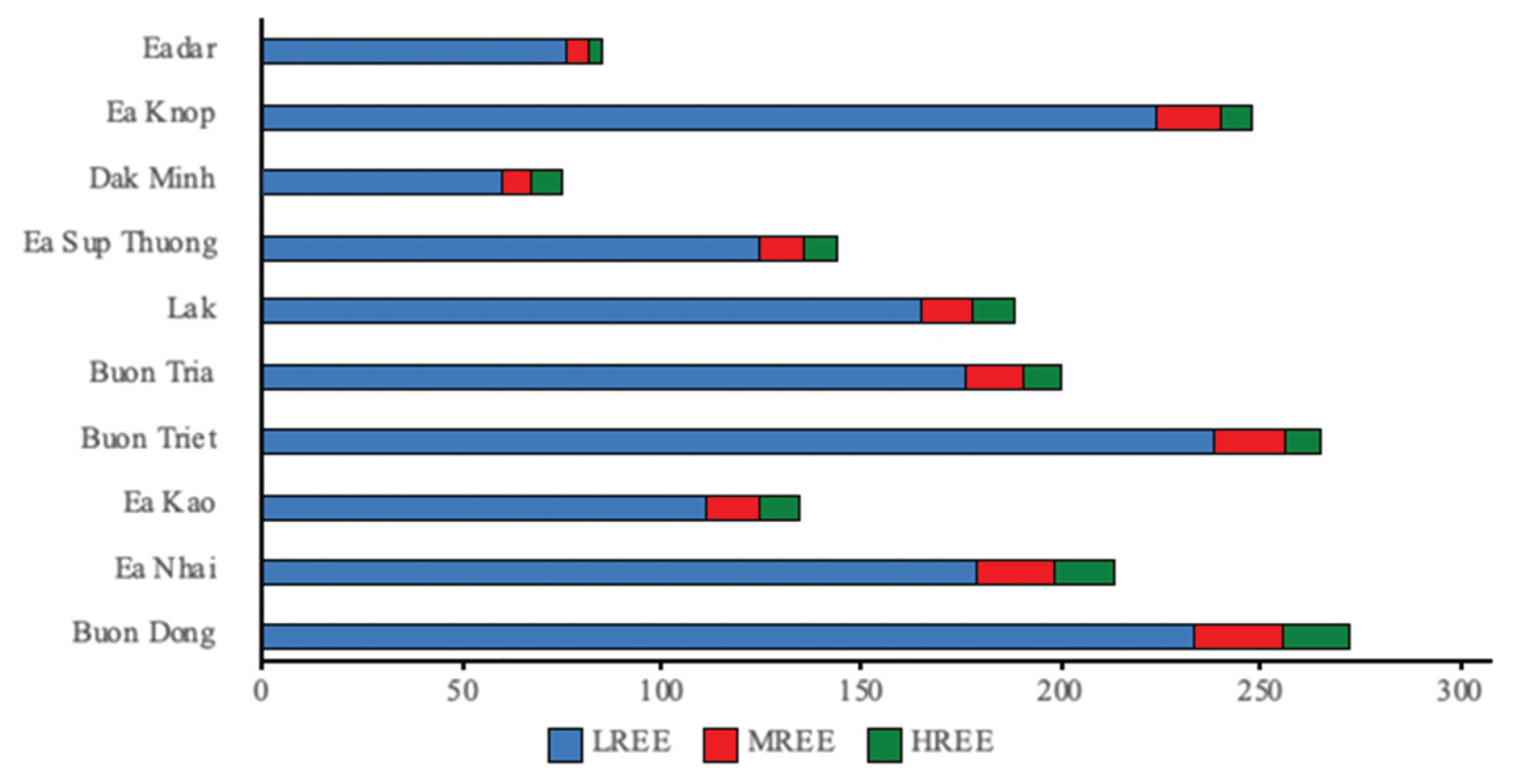

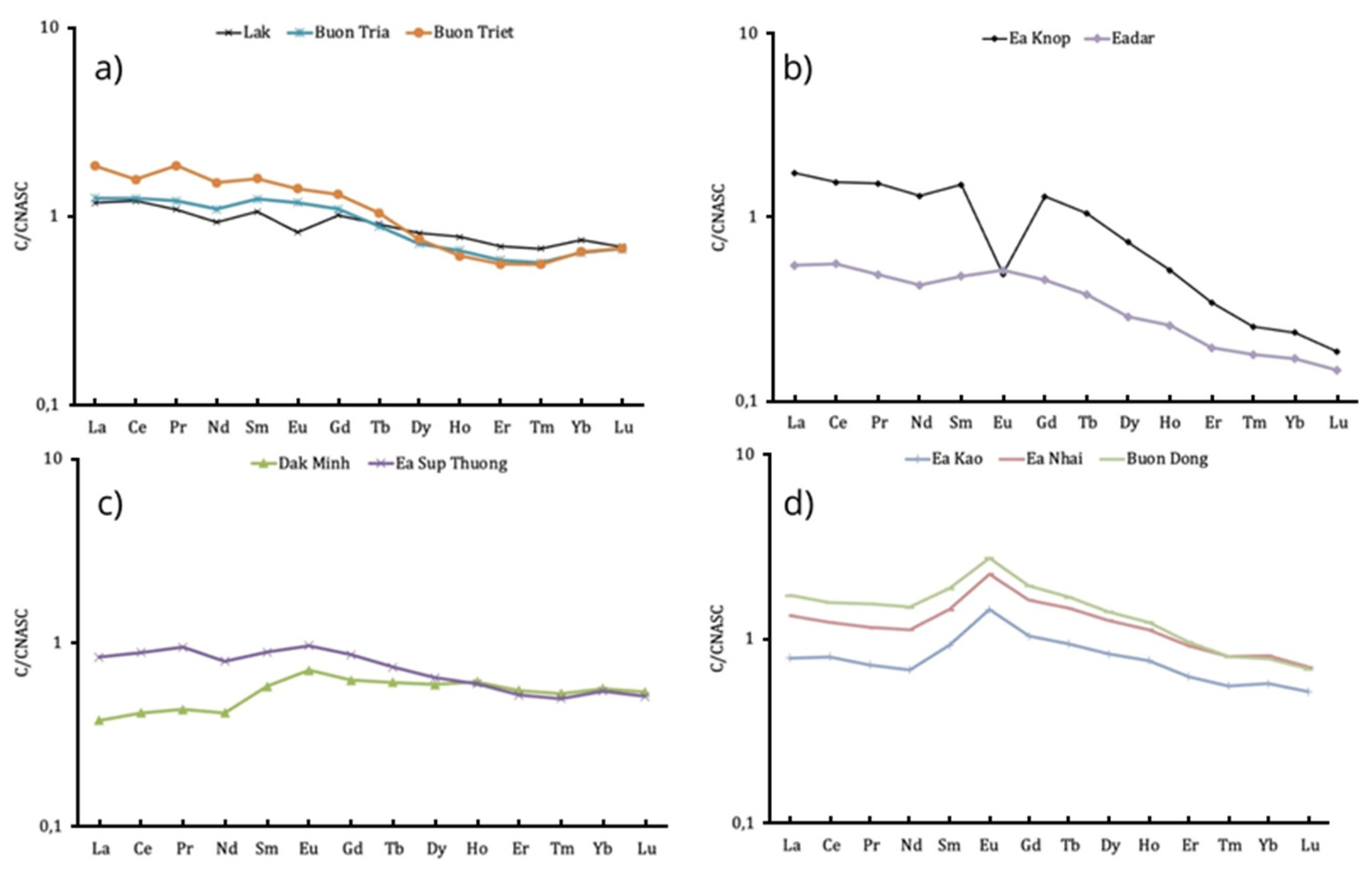

3.5. REE Patterns

4. Provenance Discrimination

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TE | Trace Elements |

| REE | Rare Earth Elements |

| CA | Cluster Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| EF | Enrichment Factor |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| NASC | North American Shale Composite |

References

- Le, H.T.; Ngo, H.T.T. Cd, Pb, and Cu in water and sediments and their bioaccumulation in freshwater fish of some lakes in Hanoi, Vietnam. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2013, 95, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N. Da; Hoang, T.T.H.; Phung, V.P.; Nguyen, T.L.T.D.T.A.H.; Rochelle-Newall, E.; Duong, T.T.; Pham, T.M.H.; Phung, T.X.B.; Nguyen, T.L.T.D.T.A.H.; Le, P.T.; et al. Evaluation of heavy metal contamination in the coastal aquaculture zone of the Red River Delta (Vietnam). Chemosphere 2022, 303, 134952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.H.; Gad, M.; Khalifa, M.M.; Elsayed, S.; Moghanm, F.S.; Ghoneim, A.M.; Danish, S.; Datta, R.; Moustapha, M.E.; Abou El-Safa, M.M. Environmental Pollution Indices and Multivariate Modeling Approaches for Assessing the Potentially Harmful Elements in Bottom Sediments of Qaroun Lake, Egypt. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, R.; Rabbi, M.H.; Baharim, N.B.; Carnicelli, S. Source identification and ecological risk assessment of heavy metal pollution in sediments of Setiu wetland, Malaysia. Environ. Forensics 2022, 23, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, G.; Yin, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.; Cao, Y.; Ni, X.; Gyimah, E. Spatial distribution and eco-environmental risk assessment of heavy metals in surface sediments from a crater lake (Bosomtwe/Bosumtwi). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19367–19380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, M.; Ustaoğlu, F.; Tokatlı, C. Ecological risks and controlling factors of trace elements in sediments of dam lakes in the Black Sea Region (Turkey). Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Peng, B.; Guo, X.; Wu, S.; Xie, S.; Wu, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Dai, Y. Distribution, source and contamination of rare earth elements in sediments from lower reaches of the Xiangjiang River, China. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojka, M.; Choiński, A.; Ptak, M.; Siepak, M. Causes of variations of trace and rare earth elements concentration in lakes bottom sediments in the Bory Tucholskie National Park, Poland. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slukovskii, Z.I.; Dauvalter, V.A.; Shelekhova, T.S. Anomalies of rare earth elements and heavy metals/metalloids in modern sediments of small lakes in the north of Karelia (Arctic): geology and technogenesis influence. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys Grygar, T.; Popelka, J.; Grygar, T.M.; Popelka, J. Revisiting geochemical methods of distinguishing natural concentrations and pollution by risk elements in fluvial sediments. J. Geochemical Explor. 2016, 170, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabijańczyk, P.; Zawadzki, J.; Łukasik, A. Assessment of the concentration of rare earth elements (REEs) in industrially impacted topsoil: a case study from the Jizera Mountains and Upper Silesian Industrial Area (USIR), Poland. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, A.P.; Priya, S.L.; Banerjee, K.; Hariharan, G.; Purvaja, R.; Ramesh, R. Heavy metal assessment using geochemical and statistical tools in the surface sediments of Vembanad Lake, Southwest Coast of India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 5899–5915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, S.; Bellucci, L.G.; Nhon, D.H. The Coast of Vietnam: Present Status and Future Challenges for Sustainable Development. In World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 415–435. ISBN 9780081008539. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Böddeker, S.; Hoelzmann, P.; Thuyên, L.X.; Huy, H.D.; Nguyen, H.A.; Richter, O.; Schwalb, A. Ecological risk assessment of a coastal zone in Southern Vietnam: Spatial distribution and content of heavy metals in water and surface sediments of the Thi Vai Estuary and Can Gio Mangrove Forest. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 114, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Nhu, T.; Bui Van, N.; Le, D.-A.; Tran Thi, T.H.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Dang Xuan, T.; Tran, H.-N.; Sang, P.N.; Saiyad Musthafa, M.; Duong, V.-H. Characteristics of heavy metals in surface sediments of the Van Don-Tra Co coast, northeast Vietnam. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 73, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.L.; Dang, H.N.; Nguyen, D.V.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Duong, T.N.; Hoang, T.C.; Nguyen, N.A.; Bui, V.V.; Nguyen, D.T.; Le, V.N.; et al. Assessment of heavy metal pollution risk in sediments of coastal ecosystems in Vietnam. Vietnam J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2025, 25, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhon, D.H.; Thanh, N.D.; Manh, H.N.; Nguyen Thi Mai, L.; Do Thi Thu, H.; Hoang Thi, C.; Van Nam, L.; Vu Manh, H.; Bui Van, V.; Bui Thi Thanh, L.; et al. Distribution and ecological risk of heavy metal(loid)s in surface sediments of the Hai Phong coastal area, North Vietnam. Chem. Ecol. 2022, 38, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh-Nho, N.; Marchand, C.; Strady, E.; Vinh, T.-V.; Nhu-Trang, T.-T. Metals geochemistry and ecological risk assessment in a tropical mangrove (Can Gio, Vietnam). Chemosphere 2019, 219, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.H.; Bien, T.X.; Dao, K.H. Reservoir surface water area variations change research using Sentinel 2 MSI data. A case study in Dak Lak province, Central Highlands (Vietnam). Adv. Geod. Geoinf. 2024, 56–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, E.; Yu, Z.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, E.; Shen, J. Spatio-temporal accumulation patterns of trace metals in sediments of a large plateau lake (Erhai) in Southwest China and their relationship with human activities over the past century. J. Geochemical Explor. 2022, 234, 106943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukina, S.; Lobus, N.; Bolotov, S. Spatial Variations of Trace and Rare Earth Elements in Tropical Lake Sediments. In Recent Research on Environmental Earth Sciences, Geomorphology, Soil Science and Paleoenvironments, Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Çiner, A., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2024; pp. 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Koukina, S.; Lobus, N.; Bolotov, S. Multi-element Signatures in Lake Bottom Sediments of Central Vietnam. In Recent Advances in Environmental Science from the Euro-Mediterranean and Surrounding Regions; Ksibi, M., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2024; pp. 811–814. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, C.; Garrett, R.G. Geochemical background—concept and reality. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 350, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koukina, S.E.; Lobus, N. V. Relationship between enrichment, toxicity, and chemical bioavailability of heavy metals in sediments of the Cai River estuary. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Viet, L.; Thuy, T.T.T. Improving the quality of coffee yield forecasting in Dak Lak Province, Vietnam, through the utilization of remote sensing data. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 095011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milnes, E.; Negro, P.; Perrochet, F. Hydrogeological study of the Basaltic Plateau in Dak Lak province, Vietnam. Prepared by the Centre for Hydrogeology and Geothermics (CHYN); 2015.

- Loring, D.H.; Rantala, R.T.T. Manual for the geochemical analyses of marine sediments and suspended particulate matter. Earth-Science Rev. 1992, 32, 235–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobus, N. V.; Peresypkin, V.I.; Shulga, N.A.; Drozdova, A.N.; Gusev, E.S. Dissolved, particulate, and sedimentary organic matter in the Cai River basin (Nha Trang Bay of the South China Sea). Oceanology 2015, 55, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukina, S.E.; Lobus, N.V.; Peresypkin, V.I.; Dara, O.M.; Smurov, A.V. Abundance, distribution and bioavailability of major and trace elements in surface sediments from the Cai River estuary and Nha Trang Bay (South China Sea, Vietnam). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 198, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, Y.A.; Orlova, V.A. Modern methods of autoclave sample preparation in chemical analysis of substances and materials. Inorg. Mater. 2008, 44, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandashev, V.K.; Turanov, A.N.; Orlova, T.A.; Lezhnev, A.E.; Nosenko, S. V.; Zolotareva, N.I.; Moskvitina, I.R. Use of the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry for element analysis of environmental objects. Inorg. Mater. 2008, 44, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukina, S.E.; Lobus, N. V.; Shatravin, A. V. Dataset on the abundance, enrichment and partitioning of chemical elements between the filtered, particulate and sedimentary phases in the Cai River estuary (South China Sea). Data Br. 2021, 107412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turekian, K.K.; Wedepohl, K.H. Distribution of the elements in some major units of the earth’s crust. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1961, 72, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The Continental Crust: its Composition and Evolution.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, 1985; ISBN 0632011483. [Google Scholar]

- Savenko, V.S. Chemical composition of World River’s suspended matter; GEOS, 2006.

- Gromet, L.P.; Haskin, L.A.; Korotev, R.L.; Dymek, R.F. The “North American shale composite”: Its compilation, major and trace element characteristics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1984, 48, 2469–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coțac, V.N.; Iancu, O.G.; Necula, N.; Sandu, M.C.; Loghin, A.A.; Chișcan, O.; Stoian, G. Rare earth elements distribution in the river sediments of Ditrău Alkaline massif, Eastern Carpathians. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0314874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Yang, J.; Wu, H.; Fu, Y.; Gao, J.; Tang, S.; Ma, S. Distribution of soil selenium and its relationship with parent rocks in Chengmai County, Hainan Island, China. Appl. Geochemistry 2022, 136, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briqueu, L.; Bougault, H.; Joron, J.L. Quantification of Nb, Ta, Ti and V anomalies in magmas associated with subduction zones: Petrogenetic implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1984, 68, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaraisky, G.P.; Aksyuk, A.M.; Devyatova, V.N.; Udoratina, O. V.; Chevychelov, V.Y. The Zr/Hf ratio as a fractionation indicator of rare-metal granites. Petrology 2009, 17, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery Claiborne, L.; Miller, C.F.; Walker, B.A.; Wooden, J.L.; Mazdab, F.K.; Bea, F. Tracking magmatic processes through Zr/Hf ratios in rocks and Hf and Ti zoning in zircons: An example from the Spirit Mountain batholith, Nevada. Mineral. Mag. 2006, 70, 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.H. Significance of Nb/Ta as an indicator of geochemical processes in the crust-mantle system. Chem. Geol. 1995, 120, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfänder, J.A.; Münker, C.; Stracke, A.; Mezger, K. Nb/Ta and Zr/Hf in ocean island basalts — Implications for crust–mantle differentiation and the fate of Niobium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2007, 254, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, K.; Schiano, P.; Allègre, C. Assessment of the Zr/Hf fractionation in oceanic basalts and continental materials during petrogenetic processes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2000, 178, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Foley, S.F.; Chen, C.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kong, W.; Lv, Y.; Santosh, M.; Jin, Q.; et al. Transition from tholeiitic to alkali basalts via interaction between decarbonated eclogite-derived melts and peridotite. Chem. Geol. 2023, 621, 121354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Deng, X.; Pirajno, F.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Chen, S.; Sun, H. The genesis of the granitic rocks associated with the Mo-mineralization at the Hongling deposit, eastern Tianshan, NW China: Constraints from geology, geochronology, geochemistry, and Sr-Nd-Hf isotopes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2022, 146, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Chen, J.; Teng, H.; Chetelat, B.; Cai, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Bouchez, J.; Moynier, F.; Gaillardet, J.; et al. A Review on the Elemental and Isotopic Geochemistry of Gallium. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; Liang, T.; Guo, Q.; Li, J.; Dai, L.; Ding, S. Discrimination of rare earth element geochemistry and co-occurrence in sediment from Poyang Lake, the largest freshwater lake in China. Chemosphere 2019, 217, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budakoglu, M.; Abdelnasser, A.; Karaman, M.; Kumral, M. The rare earth element geochemistry on surface sediments, shallow cores and lithological units of Lake Acıgöl basin, Denizli, Turkey. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2015, 111, 632–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Och, L.M.; Müller, B.; Wichser, A.; Ulrich, A.; Vologina, E.G.; Sturm, M. Rare earth elements in the sediments of Lake Baikal. Chem. Geol. 2014, 376, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Stephenson, W.; Chen, Y. Geochemical Behavior of Rare Earth Elements in Tidal Flat Sediments from Qidong Cape, Yangtze River Estuary: Implications for the Study of Sedimentary Environmental Change. Land 2024, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Han, X.; Ding, S.; Liang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Dong, L.; Zhang, H. Combining multiple methods for provenance discrimination based on rare earth element geochemistry in lake sediment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 672, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabakaran, K.; Nagarajan, R.; Eswaramoorthi, S.; Anandkumar, A.; Franco, F.M. Environmental significance and geochemical speciation of trace elements in Lower Baram River sediments. Chemosphere 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.A.; Venancio, I.M.; Marques, E.D.; Figueiredo, T.S.; Nascimento, R.A.; Smoak, J.M.; Albuquerque, A.L.S.; Valeriano, C.M.; Silva-Filho, E.V. REE Anomalies Changes in Bottom Sediments Applied in the Western Equatorial Atlantic Since the Last Interglacial. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardiyah, A.; Syahputra, M.R.; Tang, Q.; Okabyashi, S.; Tsuboi, M. The Spatial Distribution of Trace Elements and Rare-Earth Elements in the Stream Sediments Around the Ikuno Mine Area in Hyogo Prefecture, Southwest Japan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lake | Year of creation | TOC | Granulometric fractions | |||

| Gravel | Sand | Silt | Clay | |||

| Eadar | 1984 | 1.31 | 4.90 | 83.26 | 11.84 | 0.00 |

| Ea Knop | 1985-1986 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 72.97 | 26.38 | 0.00 |

| Dak Minh | 1981 | 1.92 | 2.19 | 37.17 | 58.02 | 2.62 |

| Ea Sup Thuong | 2000-2005 | 2.35 | 19.37 | 15.53 | 63.22 | 1.88 |

| Lak | Natural lake | 8.41 | 0.00 | 6.80 | 86.11 | 7.10 |

| Buon Tria | 1980 | 4.84 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 97.31 | 2.57 |

| Buon Triet | 1987 | 1.91 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 92.76 | 6.98 |

| Ea Kao | 1976-1986 | 3.05 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 92.62 | 6.66 |

| Ea Nhai | 1988 | 4.99 | 0.00 | 7.01 | 91.86 | 1.13 |

| Buon Dong | 2002-2006 | 1.23 | 0.00 | 1.69 | 96.22 | 2.09 |

| Elements | Mean ± SD | EFAlS | EFFeS | EFAlf | EFFef | Reference values | |

| [33] | [35] | ||||||

| Major elements, in % | |||||||

| Na | 0.12±0.16 | 0.14±0.17 | 0.14±0.22 | 0.09±0.11 | 0.09±0.14 | 0.96 | 0.79 |

| Mg | 0.27±0.12 | 0.18±0.09 | 0.15±0.09 | 0.25±0.13 | 0.21±0.13 | 1.50 | 0.57 |

| Al | 9.20±4.02 | 1.00 | 0.83±0.30 | 1.00 | 0.82±0.30 | 8.00 | 4.30 |

| P | 0.07±0.06 | 0.89±0.44 | 0.67±0.30 | 0.42±0.21 | 0.31±0.14 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| S | 0.06±0.05 | 0.23±0.14 | 0.18±0.11 | 1.49±0.89 | 1.15±0.73 | 0.24 | 0.02 |

| K | 0.86±0.70 | 0.34±0.32 | 0.35±0.43 | 0.44±0.42 | 0.45±0.55 | 2.66 | 1.10 |

| Ca | 0.13±0.06 | 0.09±0.09 | 0.07±0.05 | 0.05±0.05 | 0.03±0.03 | 1.60 | 1.70 |

| Ti | 0.99±0.91 | 2.14±1.97 | 1.42±0.29 | 1.71±1.57 | 1.12±0.69 | 0.46 | 0.31 |

| Mn | 0.08±0.08 | 0.96±0.99 | 0.65±0.16 | 0.88±0.90 | 0.58±0.44 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Fe | 7.38±4.38 | 1.35±0.48 | 1.00 | 1.37±0.49 | 1.00 | 4.72 | 2.50 |

| Trace elements, in μg g−1 | |||||||

| Li | 21.12±14.01 | 0.31±0.16 | 0.26±0.16 | 0.54±0.29 | 0.46±0.28 | 66 | 20 |

| Be | 1.83±0.78 | 0.58±0.19 | 0.49±0.28 | 0.62±0.20 | 0.52±0.30 | 3 | 1.50 |

| Sc | 15.44±9.38 | 1.12±0.55 | 0.93±0.69 | 0.79±0.39 | 0.64±0.48 | 13 | 10 |

| V | 156.79±103.93 | 1.12±0.59 | 0.82±0.24 | 1.56±0.82 | 1.13±0.33 | 130 | 50 |

| Cr | 120.09±92.09 | 1.24±0.83 | 0.86±0.33 | 1.20±0.81 | 0.82±0.32 | 90 | 50 |

| Co | 32.88±26.93 | 1.58±1.11 | 1.08±0.46 | 1.07±0.76 | 0.73±0.31 | 19 | 15 |

| Ni | 89.42±102.84 | 1.04±0.83 | 0.69±0.44 | 1.52±1.22 | 0.99±0.64 | 68 | 25 |

| Cu | 41.71±31.44 | 0.79±0.36 | 0.59±0.20 | 0.96±0.44 | 0.70±0.24 | 45 | 20 |

| Zn | 81.55±40.67 | 0.75±0.13 | 0.59±0.14 | 0.64±0.11 | 0.50±0.12 | 95 | 60 |

| Ga | 22.95±10.09 | 1.06±0.10 | 0.86±0.25 | 1.08±0.11 | 0.87±0.25 | 19 | 10 |

| As | 6.03±4.69 | 0.51±0.52 | 0.39±0.31 | 0.61±0.60 | 0.45±0.36 | 13 | 6 |

| Se | 1.68±0.60 | 2.77±1.07 | 2.24±1.10 | 2.98±1.15 | 2.37±1.17 | 0.60 | 0.30 |

| Rb | 57.98±48.37 | 0.41±0.36 | 0.43±0.47 | 0.62±0.54 | 0.63±0.70 | 140 | 50 |

| Sr | 55.90±23.26 | 0.20±0.15 | 0.19±0.21 | 0.22±0.16 | 0.20±0.23 | 300 | 150 |

| Y | 19.64±7.65 | 0.71±0.20 | 0.59±0.3 | 0.50±0.14 | 0.41±0.20 | 26 | 20 |

| Zr | 139.19±105.92 | 0.81±0.52 | 0.57±0.26 | 0.28±0.18 | 0.19±0.09 | 160 | 250 |

| Nb | 35.15±35.12 | 3.17±2.82 | 2.20±1.75 | 0.94±0.84 | 0.64±0.51 | 11 | 20 |

| Mo | 1.67±1.03 | 0.59±0.30 | 0.49±0.38 | 0.55±0.28 | 0.45±0.35 | 2.60 | 1.50 |

| Ag | 0.09±0.02 | 1.47±1.12 | 1.17±0.85 | 1.10±0.85 | 0.87±0.63 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Cd | 0.07±0.02 | 0.24±0.09 | 0.21±0.13 | 0.11±0.04 | 0.08±0.05 | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| Sn | 2.70±1.69 | 0.42±0.20 | 0.35±0.19 | 0.34±0.16 | 0.28±0.15 | 6 | 4 |

| Sb | 0.57±0.35 | 0.34±0.19 | 0.30±0.22 | 0.14±0.08 | 0.12±0.09 | 1.50 | 2 |

| Cs | 4.22±4.45 | 0.72±0.59 | 0.69±0.63 | 0.49±0.39 | 0.46±0.42 | 5 | 4 |

| Ba | 356.16±123.16 | 0.64±0.32 | 0.57±0.43 | 0.69±0.35 | 0.60±0.45 | 580 | 290 |

| Hf | 3.38±2.33 | 1.11±0.59 | 0.81±0.32 | 0.28±0.15 | 0.20±0.08 | 2.80 | 6 |

| Ta | 1.94±1.66 | 2.44±1.93 | 1.79±1.43 | 0.52±0.41 | 0.38±0.30 | 0.80 | 2 |

| W | 1.82±2.13 | 0.85±0.70 | 0.74±0.74 | 0.16±0.14 | 0.14±0.14 | 1.80 | 5 |

| Hg | 0.04±0.02 | 0.10±0.09 | 0.08±0.04 | 0.45±0.40 | 0.32±0.19 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

| Tl | 0.43±0.37 | 0.29±0.21 | 0.29±0.26 | 0.22±0.15 | 0.21±0.20 | 1.40 | 1 |

| Pb | 25.51±17.24 | 1.34±0.98 | 1.29±1.37 | 0.96±0.71 | 0.91±0.97 | 20 | 15 |

| Bi | 0.33±0.45 | 0.65±0.64 | 0.61±0.68 | 0.76±0.75 | 0.70±0.77 | 0.43 | 0.20 |

| Th | 14.39±9.59 | 1.31±1.09 | 1.25±1.49 | 0.84±0.71 | 0.80±0.95 | 12 | 10 |

| U | 3.40±2.63 | 0.94±0.81 | 0.93±1.15 | 0.62±0.54 | 0.60±0.75 | 3.70 | 3 |

| Rare earth elements, in μg g−1 | |||||||

| La | 37.20±16.52 | 0.43±0.3 | 0.39±0.42 | 0.56±0.39 | 0.51±0.54 | 92 | 38 |

| Ce | 80.52±30.73 | 1.46±0.93 | 1.31±1.29 | 0.62±0.39 | 0.54±0.54 | 59 | 75 |

| Pr | 8.67±3.69 | 1.64±1.06 | 1.50±1.52 | 0.62±0.40 | 0.56±0.56 | 5.6 | 8 |

| Nd | 32.21±13.13 | 1.41±0.85 | 1.27±1.23 | 0.61±0.36 | 0.54±0.52 | 24 | 30 |

| Sm | 6.59±2.57 | 1.06±0.60 | 0.95±0.89 | 0.61±0.34 | 0.53±0.50 | 6.40 | 6 |

| Eu | 1.55±0.92 | 1.42±0.57 | 1.10±0.45 | 0.51±0.21 | 0.39±0.16 | 1 | 1.50 |

| Gd | 5.85±2.30 | 0.92±0.45 | 0.80±0.66 | 0.53±0.26 | 0.45±0.38 | 6.40 | 6 |

| Tb | 0.83±0.32 | 0.82±0.37 | 0.70±0.55 | 0.44±0.20 | 0.37±0.29 | 1 | 1 |

| Dy | 4.18±1.66 | 0.87±0.31 | 0.74±0.48 | 0.43±0.15 | 0.36±0.23 | 4.60 | 5 |

| Ho | 0.74±0.29 | 0.59±0.16 | 0.48±0.24 | 0.38±0.10 | 0.31±0.15 | 1.20 | 1 |

| Er | 2.02±0.79 | 0.75±0.16 | 0.61±0.25 | 0.33±0.07 | 0.27±0.11 | 2.50 | 3 |

| Tm | 0.27±0.10 | 1.25±0.26 | 1.02±0.39 | 0.27±0.06 | 0.22±0.08 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| Yb | 1.77±0.67 | 0.62±0.13 | 0.51±0.22 | 0.29±0.06 | 0.24±0.10 | 2.60 | 3 |

| Lu | 0.26±0.10 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.28±0.13 | 0.31±0.08 | 0.26±0.12 | 0.70 | 0.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).