Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Visualizing the Mass Mystery

2. Wave-Based Paradigm Foundations

3. Two Manifestations of Energy Exchange

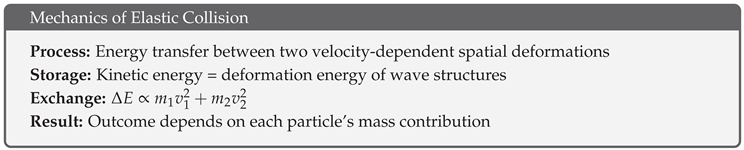

3.1. Case 1: Elastic Collision - Inertial Mass in Action

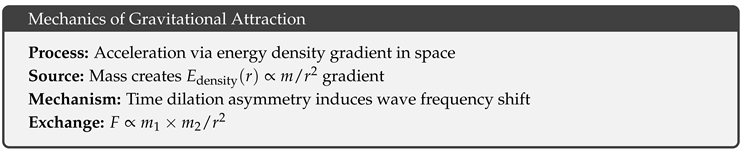

3.2. Case 2: Gravitational Attraction - Gravitational Mass in Action

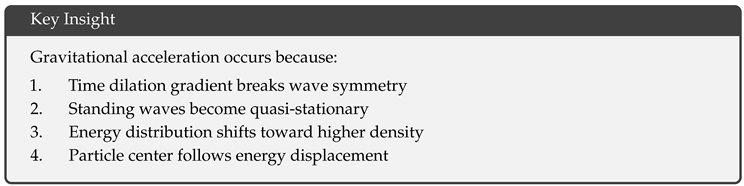

4. Visual Mechanism: Why Gravity Accelerates Matter

4.1. Standing Waves in a Gradient Field

4.2. Time Dilation Breaks Symmetry

4.3. From Standing to Quasi-Stationary Waves

5. Unified Proportionality Principle

5.1. Common Energy Basis

5.2. Why Acceleration Is Mass-Independent

6. Mathematical Formulation

6.1. Deformation Energy Framework

6.2. Unified Mass Definition

7. Resolving Historical Paradoxes

7.1. Galileo’s Universality Revisited

- Each individual atom experiences precisely the same time dilation gradient

- Wave frequency shifts induced by this gradient are identical for every atomic component

- The collective acceleration of the entire body equals the acceleration experienced by each constituent atom

- This mass-independent behavior emerges because gravitational interaction operates at the wave-structure level, not through bulk material properties

7.2. Einstein’s Elevator Thought Experiment

- Acceleration involves external forces directly reconfiguring the wave pattern geometry

- Gravity operates through internal energy density gradients that similarly reconfigure wave structures

- Both processes modify the wave geometry relative to the fundamental spatial medium

- An observer confined within either system cannot detect which mechanism is active, since both produce identical deformations of measuring instruments and biological processes

8. Experimental Verification: Explaining Established Results

8.1. Historical Experimental Validation

- Galileo (1638): All bodies fall equally regardless of composition

- Eötvös (1909): to precision for diverse materials

- Bessel (1832): Pendulum experiments confirming mass equivalence

- Modern tests: Lunar laser ranging, torsion balances, atom interferometry

8.2. Our Contribution: Explaining the "Why"

- Both masses measure deformation energy of wave structures

- Energy exchange in both collision and gravitational contexts must be proportional to this energy

- Therefore, the proportionality constants must be equal (up to universal factor G)

8.3. Future Experimental Directions

- High-energy collisions: The asymmetric H+/He+ test [3] probes whether kinetic energy storage depends on absolute velocity relative to the spatial medium, which could reveal inertial/gravitational mass differences at relativistic energies.

- Extreme gravitational fields: Near black holes or neutron stars, where energy density gradients approach wave structure scales, non-linear effects might become measurable.

- Quantum regime: As experimental techniques approach quantum gravity scales, the discrete nature of wave structure deformation could yield testable predictions.

9. Conclusion

- Inertial mass quantifies deformation energy in velocity-dependent wave structures

- Gravitational mass quantifies capacity to create energy density gradients

- Both measure the same deformation energy, differently manifested

- Gravitational acceleration occurs via time-dilation-induced wave frequency shifts

- Mass independence of g arises because each atom experiences identical gradients

References

- G. Furne Gouveia. The Vibrational Fabric of Spacetime: A Model for the Emergence of Mass, Inertia, and Quantum Non-Locality. Preprints 2025, 2025090184. [CrossRef]

- G. Furne Gouveia. The IN/OUT Wave Mechanism: A Non-Local Foundation for Quantum Behavior and the Double-Slit Experiment. Preprints 2025, 2025092122. [CrossRef]

- G. Furne Gouveia. Towards a New Physics of Space: Experimental Test via Asymmetric Ion Collisions. Preprints 2025, 2025110658. [CrossRef]

- Galileo Galilei. Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences. Leiden (1638).

- A. Einstein. The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity. Annalen der Physik 49, 769 (1916).

- L. I. Schiff. On Experimental Tests of the General Theory of Relativity. American Journal of Physics 28, 340 (1960).

- R. H. Dicke. Experimental Tests of Mach’s Principle. Physical Review Letters 12, 311 (1964).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).