Submitted:

30 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

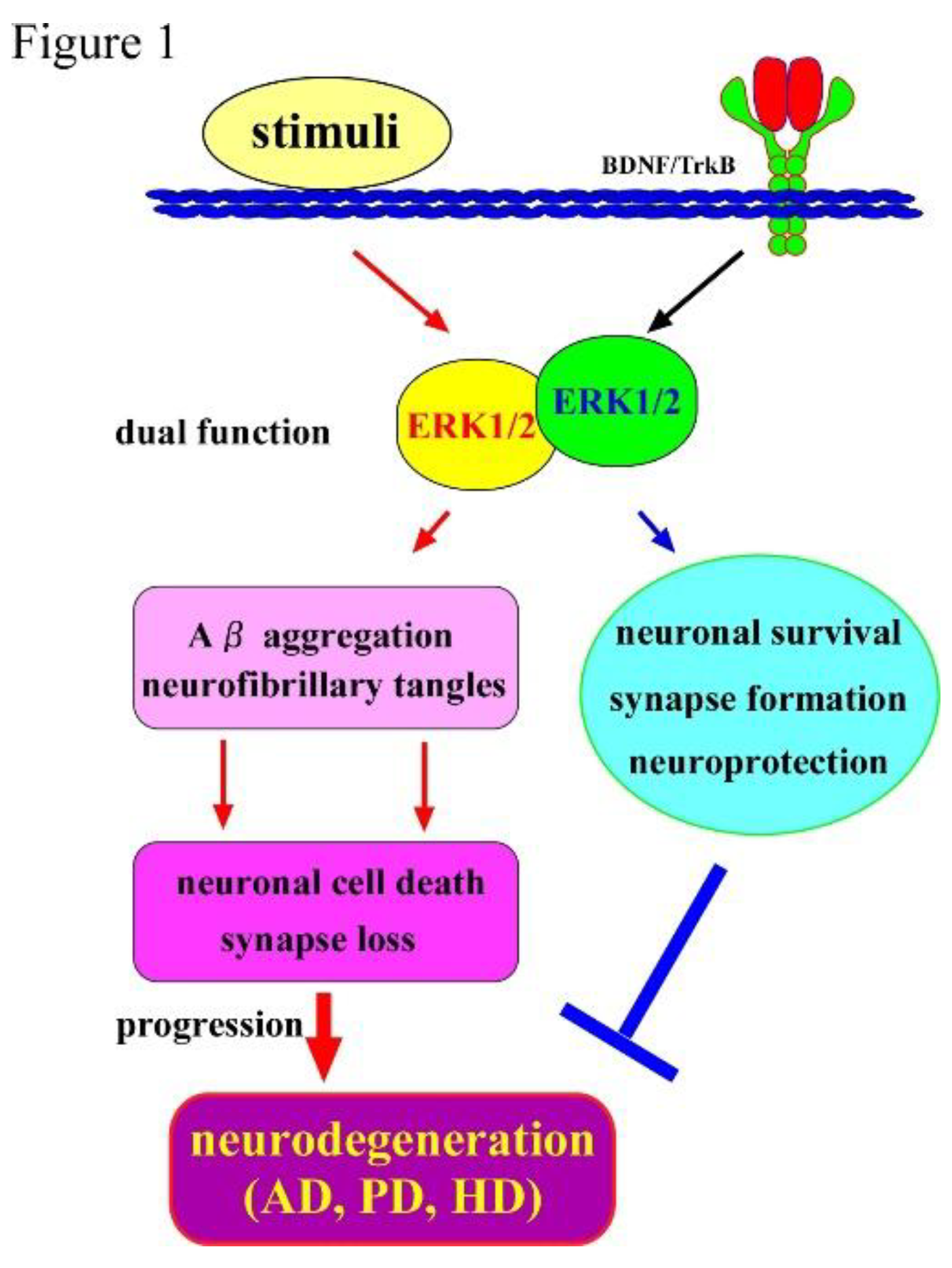

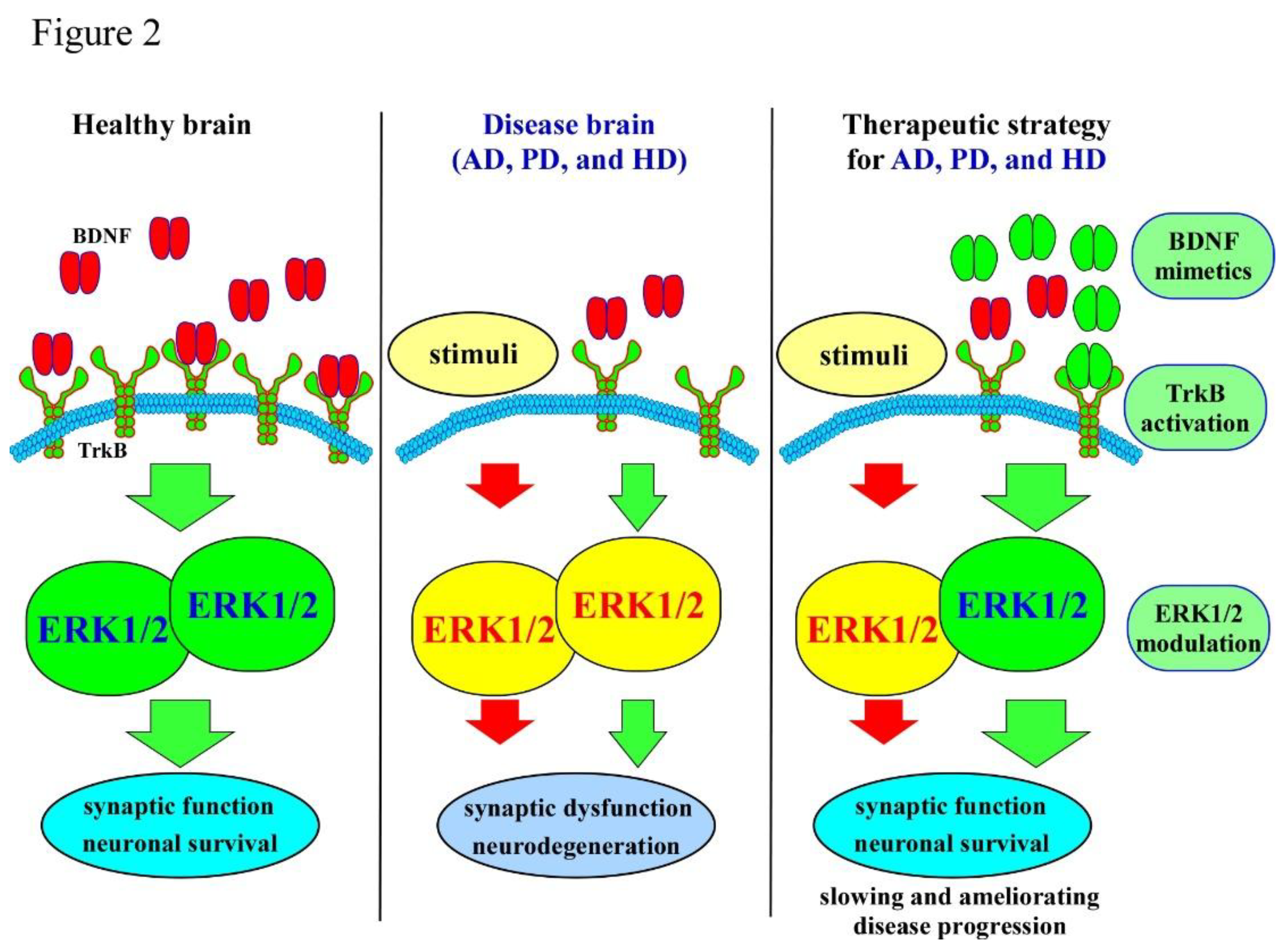

2. Relationship Among ERK Signaling and BDNF/TrkB System in Neurons

3. Natural Compounds and ERK-Signaling in AD Models

4. Chemicals and ERK-Signaling in AD Models

5. Inhibitors of ERK Signaling and AD Models

6. Neurotoxicity of Aβ and ERK Signaling

7. Role of ERK Signaling in Parkinson’s Disease

8. Role of ERK Signaling in Huntington’s Disease

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Numakawa, T.; Suzuki, S.; Kumamaru, E.; Adachi, N.; Richards, M.; Kunugi, H. BDNF function and intracellular signaling in neurons. Histol Histopathol 2010, 25, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numakawa, T.; Kajihara, R. The Role of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor as an Essential Mediator in Neuronal Functions and the Therapeutic Potential of Its Mimetics for Neuroprotection in Neurologic and Psychiatric Disorders. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, T.G.; Cobb, M.H. Identification of multiple extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) with antipeptide antibodies. Cell Regul 1991, 2, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojea Ramos, S.; Feld, M.; Fustiñana, M.S. Contributions of extracellular-signal regulated kinase 1/2 activity to the memory trace. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 988790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweatt, J.D. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2004, 14, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumamaru, E.; Numakawa, T.; Adachi, N.; Yagasaki, Y.; Izumi, A.; Niyaz, M.; Kudo, M.; Kunugi, H. Glucocorticoid prevents brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated maturation of synaptic function in developing hippocampal neurons through reduction in the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol Endocrinol 2008, 22, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numakawa, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Yokomaku, D.; Taguchi, T.; Niki, E.; Hatanaka, H.; Kunugi, H.; Numakawa, T. 17beta-estradiol protects cortical neurons against oxidative stress-induced cell death through reduction in the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase and in the accumulation of intracellular calcium. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Nan, G. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway in neurological diseases: A potential therapeutic target (Review). Int J Mol Med 2017, 39, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Hou, L.; Wei, G.; He, C.; Li, H.; Liu, L. Advances in ERK Signaling Pathway in Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Neurochem Res 2025, 50, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.L.; Lapadat, R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002, 298, 1911–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrado Fernandez, C.; Juric, S.; Backlund, M.; Dahlström, M.; Madjid, N.; Lidell, V.; Rasti, A.; Sandin, J.; Nordvall, G.; Forsell, P. Neuroprotective and Disease-Modifying Effects of the Triazinetrione ACD856, a Positive Allosteric Modulator of Trk-Receptors for the Treatment of Cognitive Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.S.; Cho, S.; Nelson, J.W.; Zipfel, G.J.; Han, B.H. TrkB agonist antibody pretreatment enhances neuronal survival and long-term sensory motor function following hypoxic ischemic injury in neonatal rats. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogdakis, T.; Charou, D.; Latorrata, A.; Papadimitriou, E.; Tsengenes, A.; Athanasiou, C.; Papadopoulou, M.; Chalikiopoulou, C.; Katsila, T.; Ramos, I.; et al. Development and Biological Characterization of a Novel Selective TrkA Agonist with Neuroprotective Properties against Amyloid Toxicity. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chu, H.; Kong, L.; Yin, L.; Ma, H. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Increases Synaptic Protein Levels via the MAPK/Erk Signaling Pathway and Nrf2/Trx Axis Following the Transplantation of Neural Stem Cells in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurochem Res 2017, 42, 3073–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Im, J.H.; Balakrishnan, R. Paeoniflorin exercise-mimetic potential regulates the Nrf2/HO-1/BDNF/CREB and APP/BACE-1/NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathways to reduce cognitive impairments and neuroinflammation in amnesic mouse model. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 189, 118299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, Z.; Cao, C.; Ding, J.; Ding, L.; Yu, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of PRG on Aβ(25-35)-induced cytotoxicity through activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 313, 116550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Che, R.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Lian, W.; He, J.; Tu, S.; Bai, X.; He, X. Cornuside, by regulating the AGEs-RAGE-IκBα-ERK1/2 signaling pathway, ameliorates cognitive impairment associated with brain aging. Phytother Res 2023, 37, 2419–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuedo, Z.; Chotphruethipong, L.; Raju, N.; Reudhabibadh, R.; Benjakul, S.; Chonpathompikunlert, P.; Klaypradit, W.; Hutamekalin, P. Oral Administration of Ethanolic Extract of Shrimp Shells-Loaded Liposome Protects against Aβ-Induced Memory Impairment in Rats. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Cycloastragenol: An exciting novel candidate for age-associated diseases. Exp Ther Med 2018, 16, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Jo, M.H.; Choe, K.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, S.; Saeed, K.; Kim, M.W.; Kim, M.O. Cycloastragenol, a Triterpenoid Saponin, Regulates Oxidative Stress, Neurotrophic Dysfunctions, Neuroinflammation and Apoptotic Cell Death in Neurodegenerative Conditions. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munni, Y.A.; Dash, R.; Choi, H.J.; Mitra, S.; Hannan, M.A.; Mazumder, K.; Timalsina, B.; Moon, I.S. Differential Effects of the Processed and Unprocessed Garlic (Allium sativum L.) Ethanol Extracts on Neuritogenesis and Synaptogenesis in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Sha, T.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ni, R.; Qi, X. Isoliquiritigenin attenuated cognitive impairment, cerebral tau phosphorylation and oxidative stress in a streptozotocin-induced mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Life Sci 2025, 376, 123759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, F.; Wang, S.; Ye, L.; Wan, W.; Zhou, X.; Liu, M.; Mo, K.; Lu, Y.; Wei, N.; Guan, Z.; et al. Chondroitin sulfate protects against synaptic impairment caused by fluorosis through the Erk1/2-MMP-9 signaling pathway. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 29760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joodi, S.A.; Khattab, M.M.; Ibrahim, W.W. Repurposing of cabergoline to improve cognitive decline in D-galactose-injected ovariectomized rats: Modulation of AKT/mTOR, GLT-1/P38-MAPK, and ERK1/2 signaling pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2025, 500, 117391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.C.; Cozachenco, D.; Argyrousi, E.K.; Staniszewski, A.; Wiebe, S.; Calixtro, J.D.; Soares-Neto, R.; Al-Chami, A.; Sayegh, F.E.; Bermudez, S.; et al. The ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine rescues hippocampal mRNA translation, synaptic plasticity and memory in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 5398–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Ramirez, K.Y.; Bagnall, C.; Frias, L.; Abdali, S.A.; Ahles, T.A.; Hubbard, K. Doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide induce cognitive dysfunction and activate the ERK and AKT signaling pathways. Behav Brain Res 2015, 292, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Sasaki, K.; Ferdousi, F.; Suresh, M.; Isoda, H.; Szele, F.G. Senescence accelerated mouse-prone 8: a model of neuroinflammation and aging with features of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Stem Cells 2025, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiguchi, I.; Pallàs, M.; Budka, H.; Akiyama, H.; Ueno, M.; Han, J.; Yagi, H.; Nishikawa, T.; Chiba, Y.; Sugiyama, H.; et al. SAMP8 mice as a neuropathological model of accelerated brain aging and dementia: Toshio Takeda's legacy and future directions. Neuropathology 2017, 37, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B.Y.; Jia, H.; Xu, L.J.; Liu, A.L.; Du, G.H. DL0410 ameliorates cognitive disorder in SAMP8 mice by promoting mitochondrial dynamics and the NMDAR-CREB-BDNF pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Liu, A.; Du, G. DL0410 attenuates oxidative stress and neuroinflammation via BDNF/TrkB/ERK/CREB and Nrf2/HO-1 activation. Int Immunopharmacol 2020, 86, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R.M.; Elsayed, N.S.; Assaf, N.; Budzyńska, B.; Skalicka-Wożniak, K.; Ibrahim, S.M. Limettin and PD98059 Mitigated Alzheimer's Disease Like Pathology Induced by Streptozotocin in Mouse Model: Role of p-ERK1/2/p-GSK-3β/p-CREB/BDNF Pathway. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2025, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Feng, P.; Peng, A.; Qiu, X.; Lai, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, W. Protective effects of isoquercitrin on streptozotocin-induced neurotoxicity. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 10458–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieb, P. Intracerebroventricular Streptozotocin Injections as a Model of Alzheimer's Disease: in Search of a Relevant Mechanism. Mol Neurobiol 2016, 53, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcicchia, C.; Tozzi, F.; Arancio, O.; Watterson, D.M.; Origlia, N. Involvement of p38 MAPK in Synaptic Function and Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.M.; Grum-Tokars, V.L.; Schavocky, J.P.; Saeed, F.; Staniszewski, A.; Teich, A.F.; Arancio, O.; Bachstetter, A.D.; Webster, S.J.; Van Eldik, L.J.; et al. Targeting human central nervous system protein kinases: An isoform selective p38αMAPK inhibitor that attenuates disease progression in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. ACS Chem Neurosci 2015, 6, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morroni, F.; Sita, G.; Tarozzi, A.; Rimondini, R.; Hrelia, P. Early effects of Aβ1-42 oligomers injection in mice: Involvement of PI3K/Akt/GSK3 and MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways. Behav Brain Res 2016, 314, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Kondo, K.; Chen, X.; Homma, H.; Tagawa, K.; Kerever, A.; Aoki, S.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.; Muramatsu, S.I.; et al. The intellectual disability gene PQBP1 rescues Alzheimer's disease pathology. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23, 2090–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Guo, S.; Luo, M.; Wu, B.; Xu, M.; Tian, Q.; et al. ELK1 inhibition alleviates amyloid pathology and memory decline by promoting the SYVN1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of PS1 in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Mol Med 2025, 57, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, R.M.; Yehia, R.; Elmongy, N.F.; Sallam, A.A.; Abd-Elgalil, M.M.; Schaalan, M.F.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.M.A.; Bazan, L.S. Evaluation of betanin-loaded liposomal nanocarriers in AlCl(3)-induced Alzheimer's disease in rats: Impact on cognitive function, neurodegeneration, and TREM2/ADAM10 pathways. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2025, 358, e2400641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yuan, J.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Zhao, K.; Huang, J.; Jiang, R. Tauopathy after long-term cervical lymphadenectomy. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21, e70136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojan, E.; Curzytek, K.; Cieślik, P.; Wierońska, J.M.; Graff, J.; Lasoń, W.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Basta-Kaim, A. Prenatal stress aggravates age-dependent cognitive decline, insulin signaling dysfunction, and the pro-inflammatory response in the APP(NL-F/NL-F) mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2023, 184, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegami, T.; Sasaki, T.; Shimbo, T.; Kitayama, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ouchi, Y.; Yamazaki, S.; Sugiyama, S.; Nishiyama, K.; Gon, Y.; et al. Characterizing stroke-related cellular changes in the surviving neurons of mouse ischemic stroke. Neurochem Int 2025, 191, 106086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. Parkinson's Disease: Bridging Gaps, Building Biomarkers, and Reimagining Clinical Translation. Cells 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.H.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; AlAseeri, A.A.; Alruwaili, M.; Saad, H.M.; Batiha, G.E. BDNF/TrkB activators in Parkinson's disease: A new therapeutic strategy. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e18368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogi, M.; Togari, A.; Kondo, T.; Mizuno, Y.; Komure, O.; Kuno, S.; Ichinose, H.; Nagatsu, T. Brain-derived growth factor and nerve growth factor concentrations are decreased in the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 1999, 270, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howells, D.W.; Porritt, M.J.; Wong, J.Y.; Batchelor, P.E.; Kalnins, R.; Hughes, A.J.; Donnan, G.A. Reduced BDNF mRNA expression in the Parkinson's disease substantia nigra. Exp Neurol 2000, 166, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, K.; Hishikawa, N.; Ono, K.; Suzuki, H.; Sawada, M.; Nagatsu, T.; Yoshida, M.; Hashizume, Y. Cytokine production of activated microglia and decrease in neurotrophic factors of neurons in the hippocampus of Lewy body disease brains. Acta Neuropathol 2005, 109, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Bohlen und Halbach, O.; Minichiello, L.; Unsicker, K. Haploinsufficiency for trkB and trkC receptors induces cell loss and accumulation of alpha-synuclein in the substantia nigra. Faseb j 2005, 19, 1740–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lian, P.; Wu, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Yang, X.; Cao, X. Alpha-synuclein Fibrils Inhibit Activation of the BDNF/ERK Signaling Loop in the mPFC to Induce Parkinson's Disease-like Alterations with Depression. Neurosci Bull 2025, 41, 951–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, A.; Maruyama, M.; Kanazawa, I.; Nukina, N. alpha-Synuclein affects the MAPK pathway and accelerates cell death. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 45320–45329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci-D'Amato, L.; Perrone-Capano, C.; di Porzio, U. Chronic activation of ERK and neurodegenerative diseases. Bioessays 2003, 25, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.H.; Kulich, S.M.; Oury, T.D.; Chu, C.T. Cytoplasmic aggregates of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases in Lewy body diseases. Am J Pathol 2002, 161, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulich, S.M.; Chu, C.T. Sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation by 6-hydroxydopamine: implications for Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 2001, 77, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Egawa, N.; Imamura, K.; Kondo, T.; Enami, T.; Tsukita, K.; Suga, M.; Yada, Y.; Shibukawa, R.; Takahashi, R.; et al. Mutant α-synuclein causes death of human cortical neurons via ERK1/2 and JNK activation. Mol Brain 2024, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.; Hensman Moss, D.; Ciosi, M.; Usdin, K.; Balmus, G.; Monckton, D.G.; Tabrizi, S.J. Huntington disease: somatic expansion, pathobiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liot, G.; Zala, D.; Pla, P.; Mottet, G.; Piel, M.; Saudou, F. Mutant Huntingtin alters retrograde transport of TrkB receptors in striatal dendrites. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 6298–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speidell, A.; Bin Abid, N.; Yano, H. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Dysregulation as an Essential Pathological Feature in Huntington's Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Li, S.H.; Sharp, A.H.; Nucifora, F.C., Jr.; Schilling, G.; Lanahan, A.; Worley, P.; Snyder, S.H.; Ross, C.A. A huntingtin-associated protein enriched in brain with implications for pathology. Nature 1995, 378, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginés, S.; Paoletti, P.; Alberch, J. Impaired TrkB-mediated ERK1/2 activation in huntington disease knock-in striatal cells involves reduced p52/p46 Shc expression. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 21537–21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodai, L.; Marsh, J.L. A novel target for Huntington's disease: ERK at the crossroads of signaling. The ERK signaling pathway is implicated in Huntington's disease and its upregulation ameliorates pathology. Bioessays. [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Lee, B.; Cho, H.Y.; Reyes, I.B.; Pu, X.A.; Saido, T.C.; Hoyt, K.R.; Obrietan, K. CREB is a key regulator of striatal vulnerability in chemical and genetic models of Huntington's disease. Neurobiol Dis 2009, 36, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, R.K.; Hennessey, T.; Johri, A.; Tiwari, S.K.; Mishra, D.; Agarwal, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Beal, M.F. Transducer of regulated CREB-binding proteins (TORCs) transcription and function is impaired in Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 3474–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, B.; Sun, Y.; von Hieber, D.; Tang, S.K.; Jones, K.S.; Maucksch, C. AAV1/2-mediated BDNF gene therapy in a transgenic rat model of Huntington's disease. Gene Ther 2016, 23, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Díaz Barriga, G.; Giralt, A.; Anglada-Huguet, M.; Gaja-Capdevila, N.; Orlandi, J.G.; Soriano, J.; Canals, J.M.; Alberch, J. 7,8-dihydroxyflavone ameliorates cognitive and motor deficits in a Huntington's disease mouse model through specific activation of the PLCγ1 pathway. Hum Mol Genet 2017, 26, 3144–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Kwatra, M.; Gawali, B.; Panda, S.R.; Naidu, V.G.M. Potential role of TrkB agonist in neuronal survival by promoting CREB/BDNF and PI3K/Akt signaling in vitro and in vivo model of 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP)-induced neuronal death. Apoptosis 2021, 26, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, P.; Dargusch, R.; Bodai, L.; Gerard, P.E.; Purcell, J.M.; Marsh, J.L. ERK activation by the polyphenols fisetin and resveratrol provides neuroprotection in multiple models of Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).