Submitted:

29 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Key Terminology

| Term | Definition | Key Distinguishing Features |

| Academic Health System (AHS) | Integrated organization combining medical education, biomedical research, clinical care delivery, and community health missions under unified or coordinated governance | Multiple missions, complex stakeholder ecosystem, distributed operations |

| Organizational Model | One of three archetypal structural frameworks (independent, integrated, hub-spoke) characterized by reporting relationships, resource allocation, and service delivery patterns | Conceptual framework used for analysis and comparison |

| Organizational Structure | The actual implemented arrangement of reporting, governance, and operations at a specific institution | May combine elements from multiple models; context-specific implementation |

| Independent (School-Based) Model | Library operates as unit within medical school with director reporting to dean, school-funded budget, and governance within school administration | Autonomy within school, direct educational alignment, single-site focus |

| Integrated (University Library) Model | Health sciences library services provided as part of comprehensive university library system with shared infrastructure and centralized operations | Economies of scale, shared services, potential for specialized positions |

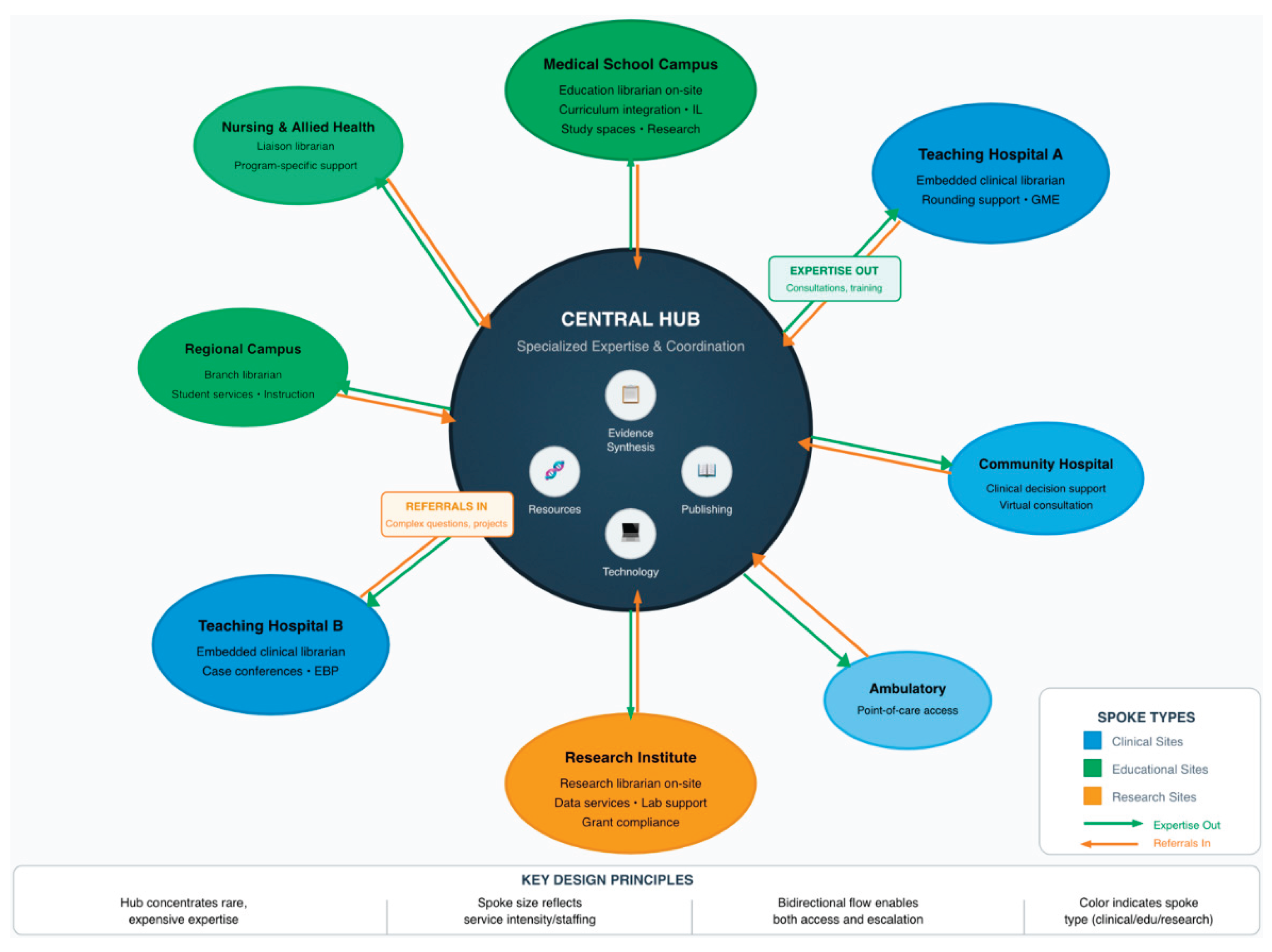

| Hub-Spoke Model | Organizational structure featuring centralized specialized expertise and coordination functions (hub) connected to distributed service points (spokes) providing local access | Combines specialization with geographic reach; requires coordination infrastructure |

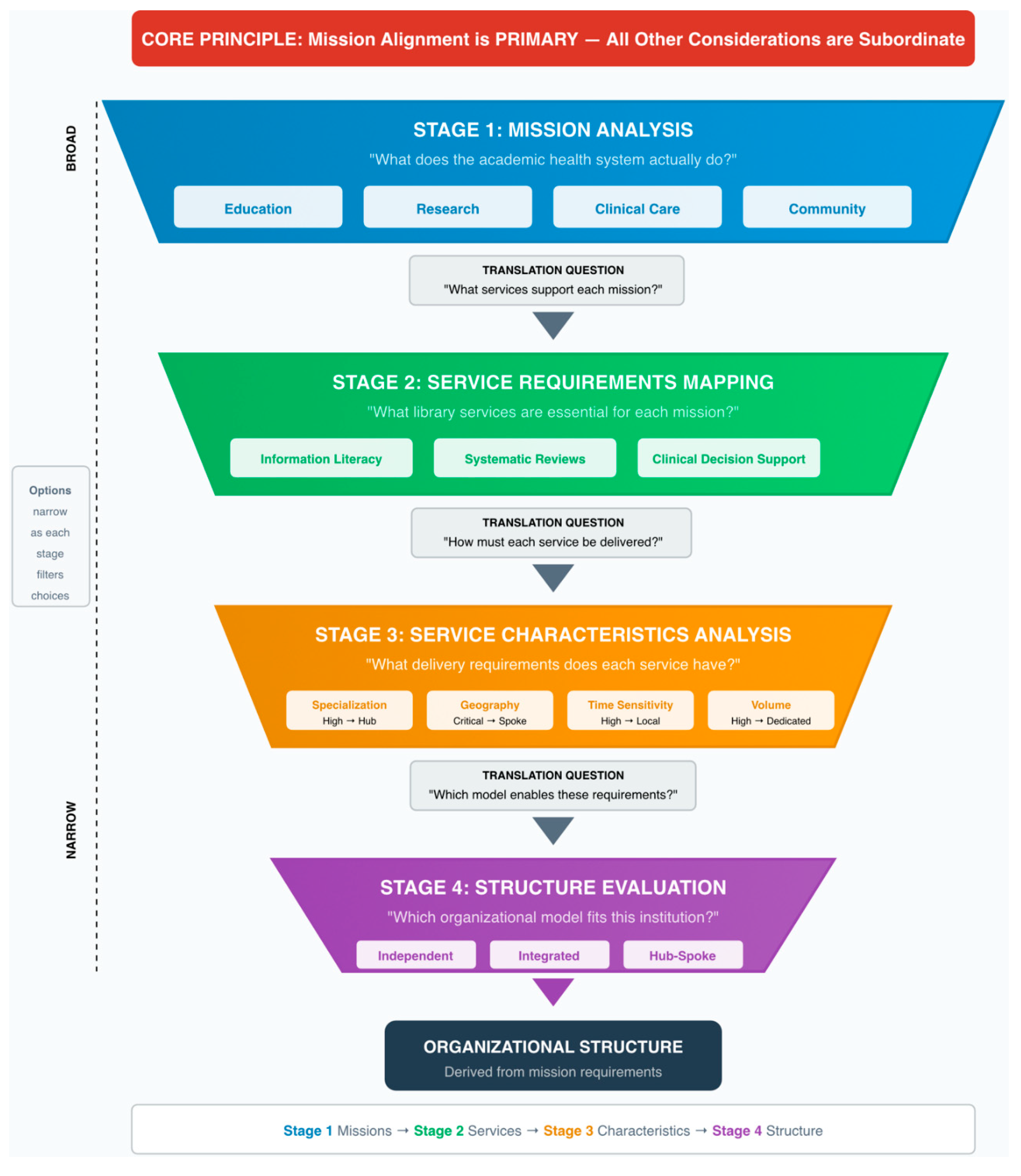

| Mission-Driven Design | Analytical approach determining organizational structure through systematic translation: institutional missions → essential services → service delivery characteristics → enabling organizational structures | Mission alignment is PRIMARY principle; other considerations are subordinate |

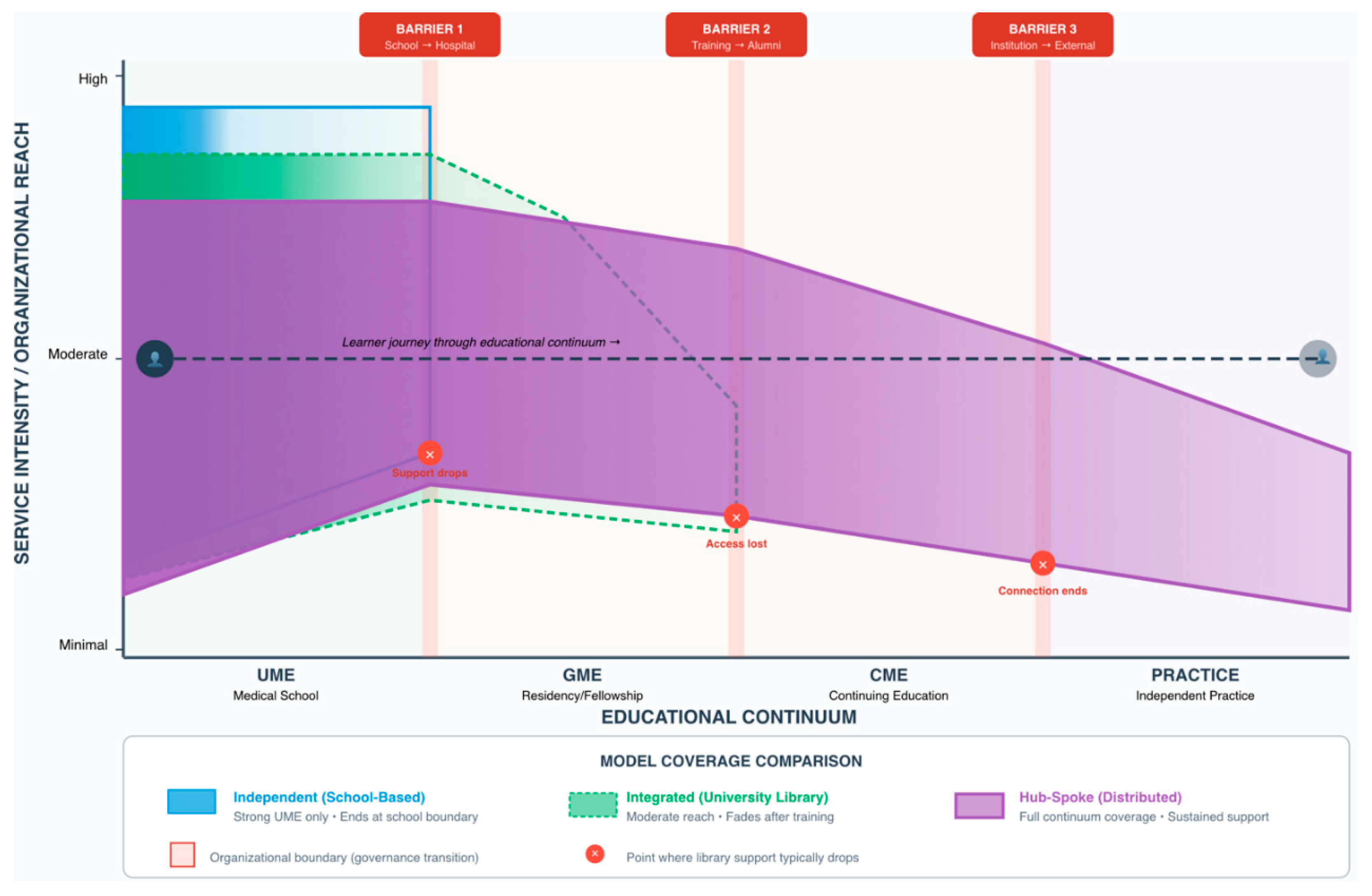

| Educational Continuum | The complete trajectory of physician development from undergraduate medical education (UME) through graduate medical education/residency (GME) through continuing medical education (CME) and lifelong learning | Emphasizes progressive competency development requiring coordinated support |

1. Introduction

1.1. The Problem and Its Strategic Importance

1.2. Purpose and Research Questions

1.3. Scope and Significance

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Foundations

2.1. Mission-Driven Organizational Design: Establishing the Foundational Principle

2.1.1. The Mission-to-Structure Translation Process

| Mission Domain | Primary Stakeholders | Essential Library Services | Consequence of Absence | Mission Criticality |

| Undergraduate Medical Education (UME) | Medical students, educational faculty | Curriculum-integrated information literacy instruction; study resources and spaces; research support for scholarly projects; clinical resources during rotations | Students graduate without required information literacy competencies; educational quality declines; accreditation jeopardized | HIGH |

| Research Mission (Basic-Level) | Faculty at primarily teaching institutions | Literature searching and retrieval; interlibrary loan; basic reference consultation; citation management support | Faculty conduct literature reviews less efficiently; publication productivity constrained | MODERATE |

| Research Mission (Research-Intensive) | Faculty at institutions with >$50M research expenditures | Systematic review services with librarian co-authorship; bioinformatics consultation; research data management; scholarly communication expertise; bibliometrics | Research quality compromised; researchers cannot compete for funding; compliance with funder mandates fails | HIGH |

| Clinical Care Mission | Attending physicians, residents, fellows, advanced practice providers | Clinical decision support tools at point of care; embedded clinical librarian services; support for practice guideline development | Clinicians make decisions without current evidence; clinical quality suffers; patient safety compromised | HIGH |

| Community Service Mission | Public, patients, community partners | Consumer health information; health literacy resources; training for professionals in patient education | Community engagement opportunities missed; population health impact limited | MODERATE |

| Characteristic Dimension | High/Critical Level | Moderate/Preferential Level | Low/Independent Level | Organizational Implication |

| Specialization Level | Systematic reviews requiring methodological sophistication; bioinformatics requiring computational expertise | Research consultation requiring professional librarian knowledge; information literacy instruction | Circulation services; basic access support; routine interlibrary loan | High specialization favors hub concentration |

| Geographic Dependence | Clinical embedding requiring physical presence at care sites; student services requiring campus proximity | Reference consultation benefiting from face-to-face but functional via video | Systematic reviews fully location-independent; electronic resource management | Geographic dependence requires spoke presence |

| Time Sensitivity | Clinical questions requiring evidence within hours; urgent grant deadlines | Literature support for manuscripts needed within days | Systematic review projects unfolding over months | High time sensitivity demands local presence |

| Volume and Frequency | Information literacy instruction in hundreds of sessions annually; daily clinical consultations | Systematic review requests averaging 30-50 annually | Specialized methodology consultation occurring occasionally | High volume justifies dedicated positions |

2.1.2. Mission Primacy: Why Mission Alignment Must Be the Primary Principle

2.2. Organizational Theories as Analytical Tools

2.3. Literature Review: Findings and Implications

2.4. Accreditation Requirements: Establishing Minimum Standards

| Accrediting Body | Applicable Standard | Key Requirements | Organizational Implications |

| LCME | Standard 6.1: Library Resources and Staff | Sufficient resources and staff at all sites; adequate personnel with expertise; training in literature searching | Distribution requirement: challenges campus-only models. Expertise requirement: cannot rely solely on non-professional staff. |

| LCME | Standard 7.5: Self-Directed and Lifelong Learning | Prepare students for lifelong learning; information literacy as core competency | Curriculum integration imperative: library must be educational partner. |

| ACGME | Common Program Requirement II.B.1 | Residents have access to adequate resources at all training sites | Multi-site access requirement: creates challenge for traditional campus libraries. |

| ACGME | Common Program Requirement IV.C | Adequate resources for scholarly activities | GME-specific support requirement: services that school-based libraries may not provide. |

3. Research Methods

3.1. Research Approach

4. Organizational Models and Mission Alignment Analysis

4.0. Comparative Overview: Three Primary Models

| Dimension | Independent (School-Based) | Integrated (University Library) | Hub-Spoke (Distributed) |

| Governance | Reports to Dean of Medical School | Reports through university library administration | Unified governance across distributed locations |

| Budget Structure | School educational budget | University library allocation with health sciences share | Multiple funding sources pooled |

| Typical Staffing | 6-10 FTE | 6-12 FTE health sciences specialists plus shared services | 12-18 FTE (6 hub + 7-12 spokes) |

| Geographic Reach | Single campus concentration | Single campus or limited distribution | System-wide distributed presence |

| 136 refereUME Support | Excellent | Good to Strong | Excellent |

| GME Support | Weak to Minimal | Weak to Moderate | Excellent |

| Research Support (Generalist) | Good | Strong | Excellent |

| Research Support (Specialized) | Limited | Strong to Excellent | Excellent |

| Clinical Care Support | Weak | Weak to Moderate | Excellent |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Moderate | High |

| Optimal Context | Education-focused, geographically centralized, 300-600 students | Research-intensive universities, multiple health sciences programs, cost efficiency priority | Large geographically distributed AHS, 3+ clinical sites, >1,500 residents/clinicians |

| Primary Strength | Deep educational integration | Cost efficiency through economies of scale | Comprehensive mission support across distributed geography |

| Primary Limitation | Cannot sustain specialized services; limited GME/clinical reach | Risk of health sciences focus dilution | Highest organizational investment and coordination complexity |

4.1. Independent School-Based Library Model

4.2. Integrated University Library System Model

4.3. Hub-Spoke Distributed Model

5. Service Delivery Across the Educational Continuum

5.1. The Continuum Challenge

5.2. Phase-Specific Characteristics and Support Requirements

5.3. Organizational Models and Continuum Support

6. Implementation Framework

6.1. Pre-Implementation Assessment

6.2. Phased Implementation Approach

6.3. Stakeholder Engagement

6.4. Monitoring and Adaptation

7. Discussion

7.1. Key Findings

7.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations

8. Conclusion

8.1. Central Conclusions

8.2. Recommendations by Stakeholder Group

8.3. Call to Action and Final Reflections

References

- Cooper ID, Crum JA. New activities and changing roles of health sciences librarians: a systematic review, 1990-2012. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013;101(4):268-77. [CrossRef]

- Rankin JA, Grefsheim SF, Canto CC. The emerging informationist specialty: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Libr Assoc. 2008;96(3):194-206. [CrossRef]

- Lessick S, Perryman C, Billman BL, Alpi KM, De Groote SL, Babin TD. Academic health sciences libraries and affiliated hospitals: a study of collaboration models. J Med Libr Assoc. 2020;108(2):269-78.

- Sathe NA, Jerome RN, Giuse NB. Librarian-perceived barriers to the implementation of the informationist/information specialist in context role. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(3):270-4. [CrossRef]

- Gore SA, Nordberg JM, Palmer LA, Piorun ME. Trends and gaps in awareness of systematic review methodology: a pilot survey of medical librarians in the northeastern United States. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(4):541-6.

- Gore SA, Epstein BA, Grayson K, Kramer JS, Layton R, Palmer LA, et al. Health sciences librarian research and instruction services in pandemic information environments. J Med Libr Assoc. 2022;110(2):198-209.

- Tooey MJ. Information and Innovation: A Natural Combination for Health Sciences Libraries. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(4):423-9.

- Breathnach R, O'Connor Á. Key Performance Indicators in Irish Hospital Libraries: Developing Outcome-Based Metrics to Support Advocacy and Service Delivery. Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2017;12(4):27-44.

- Hamdy H, Anderson MB. The Arabian Gulf University College of Medicine and Medical Sciences: a successful model of a multinational medical school. Acad Med. 2006;81(12):1085-90. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581-629. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. [CrossRef]

- Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL Jr. The hub-and-spoke organization design: an avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(Suppl 1):457. [CrossRef]

- Katz SS, Linderman AR, Akers AK, Campion TR Jr. Health Sciences Libraries Advancing Collaborative Clinical Research. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(3):308-16.

- Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Chen HC, ten Cate O, O'Brien B. Evidence-based medicine training in undergraduate medical education: a review and critique of the literature published 2006-2011. Acad Med. 2013;88(7):1022-8.

- Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):676-82.

- Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149-58. [CrossRef]

- Wartman SA. Toward a virtuous cycle: the changing face of academic health centers. Acad Med. 2008;83(9):797-9. [CrossRef]

- Eldredge JD, Morley SK, Hendrix IC, Carr MP, Bengtson JD. Library services in the curricula of U.S. nurse practitioner programs. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001;89(1):26-33.

- Lappa E. Undertaking an information-needs analysis of the emergency-care physician to inform the development of a digital library at the point of care. Health Info Libr J. 2005;22(2):124-32.

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65-76. [CrossRef]

- Michener JL, Yaggy S, Lyn M, Warburton S, Champagne M, Black M, et al. Improving the health of the community: Duke's experience with community engagement. Acad Med. 2008;83(4):408-13. [CrossRef]

- Detlefsen EG. The information behaviors and reflective learning of pre-clinical medical students. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013;101(1):20-30.

- Urquhart C, Yeoman A. Reflective practice and continuing professional development in health library and information services. Health Info Libr J. 2010;27(4):255-64.

- Jabareen Y. Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(4):49-62. [CrossRef]

- Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2016;11:33. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer J, Salancik GR. The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. Am Sociol Rev. 1978;23(2):123-33.

- Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):95. [CrossRef]

- Sen BA. Defining and measuring effectiveness and productivity in the academic library. Libr Manag. 2014;35(3):200-5.

- Cooke M, Irby DM, O'Brien BC. Educating physicians: a call for reform of medical school and residency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1339-40.

- Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-45.

- Moses H 3rd, Matheson DH, Cairns-Smith S, George BP, Palisch C, Dorsey ER. The anatomy of medical research: US and international comparisons. JAMA. 2015;313(2):174-89.

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743-8.

- Darnell JS, Cahn S, Turnock B, Becker C, Franzel J. Factors associated with state health department engagement in community health improvement. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(5):432-41.

- Lyon JA, Giuse NB, Williams A, Koonce T, Walden R. A model for training the new bioinformationist. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004;92(2):188-95.

- Koufogiannakis D, Buckingham J, Alibhai A, Rayber D. Impact of librarians in first-year medical and dental student problem-based learning (PBL) groups: a controlled study. Health Info Libr J. 2005;22(3):189-95. [CrossRef]

- Eldredge JD. Evidence-based librarianship: an overview. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000;88(4):289-302.

- McGowan J, Hogg W, Campbell C, Rowan M. Just-in-time information improved decision-making in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3785. [CrossRef]

- Lappa E. Teaching information literacy for evidence-based practice at the medical school of the University of Patras. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(1):64-8.

- Shaneyfelt T, Baum KD, Bell D, Feldstein D, Houston TK, Kaatz S, et al. Instruments for evaluating education in evidence-based practice: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1116-27.

- Dee C, Blazek R. Information needs of the rural physician: a descriptive study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1993;81(3):259-64.

- Tenopir C, King DW, Edwards S, Wu L. Electronic journals and changes in scholarly article seeking and reading patterns. Aslib Proc. 2009;61(1):5-32. [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen ML, Murad MH, Livingston EH. Engaging medical librarians to improve the quality of review articles. JAMA. 2014;312(10):999-1000. [CrossRef]

- Swinkels JA, Albarqouni L, de Boer A, Borra R, Burger H, Cunningham M, et al. Large-scale systematic review support for guideline developers by health science librarians: a mixed-methods study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2024;112(3):304-14.

- Frooman J. Stakeholder influence strategies. Acad Manage Rev. 1999;24(2):191-205.

- Hillman AJ, Withers MC, Collins BJ. Resource dependence theory: a review. J Manage. 2009;35(6):1404-27. [CrossRef]

- Zucker LG. Institutional theories of organization. Annu Rev Sociol. 1987;13:443-64.

- Federer LM, Lu YL, Joubert DJ. Data literacy training needs of biomedical researchers. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(1):52-7. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2006;101(473):318-20.

- Dorsey ER, de Roulet J, Thompson JP, Reminick JI, Thai A, White-Stellato Z, et al. Funding of US biomedical research, 2003-2008. JAMA. 2010;303(2):137-43. [CrossRef]

- Tenopir C, Sandusky RJ, Allard S, Birch B. Research data management services in academic research libraries and perceptions of librarians. Libr Inf Sci Res. 2014;36(2):84-90. [CrossRef]

- Topper LA, Boyce KM, Maggio LA. Leveraging accreditation to integrate sustainable information literacy instruction into the medical school curriculum. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106(3):355-63.

- Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(1):25-32. [CrossRef]

- Yin RK. Case study research and applications: design and methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2018.

- Morgan DL. Pragmatism as a paradigm for social research. Qual Inq. 2014;20(8):1045-53. [CrossRef]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.

- May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci. 2016;11:141.

- Davidoff F, Florance V. The informationist: a new health profession? Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(12):996-8. [CrossRef]

- Perry GJ, Kronenfeld MR. Evidence-based practice: a new paradigm brings new opportunities for health sciences librarians. Med Ref Serv Q. 2005;24(4):1-16.

- Swanberg SM, Dennison CC, Farrell A, Machel V, Marton C, O'Brien KK, et al. Integrating Information Literacy and Evidence-based Medicine Content within a New School of Medicine Curriculum. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(2):134-42.

- Williams L, Zipperer L. Improving access to information: librarians and nurses team up for patient safety. Nurs Econ. 2003;21(5):199-201.

- Giuse DA, Williams AM, Giuse NB. Integrating best evidence into patient care: a process facilitated by a seamless integration with information technology. J Med Libr Assoc. 2010;98(3):220-2. [CrossRef]

- Crespo J. Training the health information seeker: quality issues in health information websites. Libr Trends. 2004;53(2):360-74.

- Marshall JG, Morgan JC, Klem ML, Thompson CA, Wells AL. The value of library and information services in patient care: results of a multisite study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013;101(1):38-46. [CrossRef]

- Carlson J, Kneale R. Embedded librarianship in the research context: navigating new waters. Coll Res Libr News. 2011;72(3):167-70. [CrossRef]

- Kronenfeld MR, Stephenson PL, Nail-Chiwetalu B, Tweed EM, Sauers EL, McLeod TCV, et al. Review for librarians of evidence-based practice in nursing and the allied health professions in the United States. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(4):394-407. [CrossRef]

- Beyer FR, Wright K. Can we prioritise which databases to search? A case study using a systematic review of frozen shoulder management. Health Info Libr J. 2013;30(1):49-58. [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Stahl L, Knotts E. Emerging roles of health information professionals for library and knowledge services in the face of automation. Med Ref Serv Q. 2018;37(3):288-99.

- Banks MA, Cogdill KW, Selden CR, Cahn MA. Complementary competencies: public health and health sciences librarianship. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93(4):452-8.

- Williams L, Zipperer L, Muñoz M. Clinical librarian participation in interprofessional education and practice. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(4):430-2.

- Huber JT, Snyder M. Facilitating access to consumer health information: a collaborative approach addressing information overload. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(3):284-92.

- Maggio LA, Leroux TC, Meyer HS, Artino AR Jr. #MedEd: exploring the relationship between altmetrics and traditional measures of dissemination in health professions education. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(4):239-47. [CrossRef]

- Giuse NB, Williams AM, Giuse DA. Evolving to meet user needs: case studies of library spaces that support redefined roles of academic health sciences libraries. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013;101(3):171-7.

- Shumaker D, Talley M. Models of embedded librarianship: a research summary. Inf Outlook. 2010;14(1):26-8.

- Morris M, Boruff J, Gore GC. Scoping reviews: establishing the role of the librarian. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(4):346-54.

- Dee C, Stanley EE. Information-seeking behavior of nursing students and clinical nurses: implications for health sciences librarians. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93(2):213-22.

- Wagner KC, Briere L, Corrêa JA, Marcotte S, Bouffard AS. Integrating Medical Librarians Into Infectious Disease Consultations: Enhancing Evidence-Based Practice. J Med Libr Assoc. 2024;112(2):223-32.

- Perrier L, Farrell A, Ayala AP, Lightfoot D, Kenny T, Aaronson E, et al. Effects of librarian-provided services in healthcare settings: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(6):1118-24. [CrossRef]

- Weightman AL, Williamson J; Library and Information Research Group. The value and impact of information provided through library services for patient care: a systematic review. Health Info Libr J. 2005;22(1):4-25. [CrossRef]

- Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, Wallace F. Core implementation components. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19(5):531-40. [CrossRef]

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225-30.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [CrossRef]

- Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. 2003;289(15):1969-75.

- Ilic D, Maloney S. Methods of teaching medical trainees evidence-based medicine: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2014;48(2):124-35. [CrossRef]

- Guyatt GH, Meade MO, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Haynes RB. Practitioners of evidence based care. Not all clinicians need to appraise evidence from scratch but all need some skills. BMJ. 2000;320(7240):954-5.

- Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou P, Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach it. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

- Burnham E, Peterson EB. Health information literacy: a library case study. Health Info Libr J. 2005;22(2):97-105.

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1613-22. [CrossRef]

- Chen FM, Bauchner H, Burstin H. A call for outcomes research in medical education. Acad Med. 2004;79(10):955-60.

- Kennedy TJ, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard LA. Progressive independence in clinical training: a tradition worth defending? Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S106-11. [CrossRef]

- Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT; ACGME Work Group on Resident Duty Hours. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1112-4.

- Norcini JJ. Current perspectives in assessment: the assessment of performance at work. Med Educ. 2005;39(9):880-9. [CrossRef]

- Prideaux D. Curriculum design. BMJ. 2003;326(7383):268-70.

- Hunt DP, Haidet P, Coverdale JH, Richards B. The effect of using team learning in an evidence-based medicine course for medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15(2):131-9. [CrossRef]

- Schuers M, Griffon N, Kerdelhué G, Foubert A, Mercier A, Darmoni SJ. Behavior and attitudes of residents and general practitioners in searching for health information. Int J Med Inform. 2016;89:9-14. [CrossRef]

- Murphy SA, Boden C. Benchmarking participation in Canadian health sciences journal clubs. J Med Libr Assoc. 2015;103(1):38-46.

- Davies K. Formulating the evidence based practice question: a review of the frameworks. Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2011;6(2):75-80.

- Crumley E, Koufogiannakis D. Developing evidence-based librarianship: practical steps for implementation. Health Info Libr J. 2002;19(2):61-70. [CrossRef]

- Blake L, Ballance D. Teaching evidence-based practice in the hospital and the library: two different groups, one course. Med Ref Serv Q. 2013;32(1):100-10. [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Chandler J, Hawkes CA, Crichton N, Allen C, et al. The role of evidence, context, and facilitation in an implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2013;8:28. [CrossRef]

- Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, McElwee N, Guise JM, Santa J, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):985-91. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh T, Wieringa S. Is it time to drop the 'knowledge translation' metaphor? A critical literature review. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(12):501-9. [CrossRef]

- Rapport F, Clay-Williams R, Churruca K, Shih P, Hogden A, Braithwaite J. The struggle of translating science into action: foundational concepts of implementation science. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24(1):117-26. [CrossRef]

- Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. [CrossRef]

- Boaz A, Hanney S, Borst R, O'Shea A, Kok M. How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):60. [CrossRef]

- Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102-11. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):189. [CrossRef]

- Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments. Implement Sci. 2015;10:155. [CrossRef]

- Brehaut JC, Eva KW. Building theories of knowledge translation interventions: use the entire menu of constructs. Implement Sci. 2012;7:114. [CrossRef]

- Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8:65. [CrossRef]

- Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):281-315. [CrossRef]

- Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Interventions in organizational and community context: a framework for building evidence. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(1-2):21-37. [CrossRef]

- Olswang LB, Prelock PA. Bridging the gap between research and practice: implementation science. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2015;58(6):S1818-26. [CrossRef]

- Lehoux P, Grimard D, Hivon M, Williams-Jones B. The practice of health technology assessment: what might implementation science bring? Healthc Policy. 2014;9(4):10-4.

- Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implement Sci. 2006;1:1.

- Wensing M, Grol R. Knowledge translation in health: how implementation science could contribute more. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):88. [CrossRef]

- Sales A, Smith J, Curran G, Kochevar L. Models, strategies, and tools: theory in implementing evidence-based findings into health care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S43-9.

- Brehaut JC, Colquhoun HL, Eva KW, Carroll K, Sales A, Michie S, et al. Practice feedback interventions: 15 suggestions for optimizing effectiveness. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(6):435-41.

- Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart EE, Jaén CR. Summary of the National Demonstration Project and recommendations for the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S80-90. [CrossRef]

- Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Tuzzio L, Jones S, et al. From classification to causality: advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Health. 2018;6:136. [CrossRef]

- Koczwara B, Stover AM, Davies L, Davis MM, Fleisher L, Raber M, et al. Harnessing the synergy between improvement science and implementation science in cancer: a call to action. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(6):335-40. [CrossRef]

- Schneider KA, Houk KM, Humphreys BL, Cooper ID. Realizing the vision: a 10-year follow-up survey of US academic libraries. J Med Libr Assoc. 2022;110(3):331-45.

- Giuse NB, Huber JT, Giuse DA, Brown RL, Bankowitz RA, Hunt S. Information needs of health care professionals in an AIDS outpatient clinic as determined by chart review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1994;1(5):395-403. [CrossRef]

- Shearer BS, Seymour A, Capitani C. Bringing the best of medical librarianship to the patient team. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002;90(1):22-6.

- Tenopir C, Dalton ED, Allard S, Frame M, Pjesivac I, Birch B, et al. Changes in data sharing and data reuse practices and perceptions among scientists worldwide. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134826. [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33(7):14-26. [CrossRef]

- Trotter RT 2nd. Qualitative research sample design and sample size: resolving and unresolved issues and inferential imperatives. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):398-400. [CrossRef]

- Anderson KM. Organizational complexity and leadership. J Nurs Adm. 2012;42(12):575-9.

- Poll R, Payne P. Impact measures for libraries and information services. Libr Hi Tech. 2006;24(4):547-62. [CrossRef]

- Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Malden: Blackwell; 2006.

- Schonfeld RC, Long MP. Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2013. New York: Ithaka S+R; 2014.

- Eskola EL. University students' information seeking behaviour in a changing learning environment. Inf Res. 2005;10(2):paper 215.

- Hallam G, Hiskens A. Challenges to library and information science education in Australia. IFLA J. 2008;34(4):343-51.

- Davidoff F, Haynes B, Sackett D, Smith R. Evidence based medicine: a new journal to help doctors identify the information they need. BMJ. 1995;310(6987):1085-6.

- Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Davis D, editors. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).