1. Introduction

Odontogenic chronic rhinosinusitis (OCRS) is a subtype of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) associated with dental infection. The definition corresponds to CRS, with OCRS additionally requiring an identifiable odontogenic cause. According to EPOS 2020, OCRS belongs to the category of secondary localized (usually unilateral) forms of CRS [

1]. Older literature reports OCRS prevalence in CRS at 10–15 %, whereas more recent studies report up to 40 % [

2,

3,

4,

5]. This trend is attributed to the increasing number of procedures in conservative oral surgery and dental implantology [

3,

5,

6].

The key etiopathogenetic requirement for OCRS is disruption of the Schneiderian membrane lining the maxillary sinus. Due to its close proximity to the roots of upper premolars and molars, inflammatory processes may spread into the maxillary sinus and subsequently into other paranasal sinuses [

7,

8,

9]. Causes include periapical pathology (chronic periodontitis, periapical abscess, radicular cyst), oroantral fistula (persistent oroantral communication after tooth extraction), inflammatory complications after implant placement, or complications of endodontic treatment (e.g., overfilling of root canals) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. All these complications share a common origin: carious or periodontally compromised teeth resulting from inadequate oral hygiene. Less common causes include trauma and retained, ectopic, or supernumerary teeth [

15,

16].

The microbiology of OCRS differs from non-odontogenic CRS. Strict and facultative anaerobes are more frequent, often presenting as mixed aerobic–anaerobic infections. Common pathogens include

Peptostreptococcus spp.,

Prevotella spp.,

Fusobacterium spp., and

Eikinella corrodens [

17,

18,

19]. Other organisms include alpha-hemolytic streptococci,

Staphylococcus aureus, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

2,

20]. Fungal species such as

Candida albicans or

Aspergillus spp. may also occur, particularly in cases of overfilled root canals leading to fungus balls of odontogenic origin [

3,

21,

22].

Typical symptoms include nasal discharge (usually unilateral, anterior or postnasal, often malodorous), facial or dental pain/pressure, nasal obstruction, and olfactory dysfunction [

3,

23]. Less common symptoms are cough, nausea, fatigue, fever, or fetor [

2,

4]. Symptoms must persist for more than 12 weeks to meet CRS criteria.

Diagnosis is multidisciplinary, combining history, clinical examination by both dentist and ENT specialist including nasal endoscopy, and imaging studies [

24]. Conventional CT of the paranasal sinuses is the standard modality, confirming the dental cause and displaying the extent of sinus involvement. Disease severity may be classified using the Lund–Mackay (LMS) or modified Zinreich score [

25,

26,

27]. Additional imaging options include panoramic radiography (OPG) or cone-beam CT (CBCT) [

6].

Treatment of OCRS consists of eliminating the underlying dental source (tooth removal, implant removal, closure of oroantral fistula, etc.) and managing the affected paranasal sinuses, typically using ESS (usually middle meatal antrostomy, with further steps depending on disease extent) [

28]. Dental treatment should ideally precede ESS or be performed during the same session. Dental management alone may resolve symptoms, with ESS reserved for persistent disease [

3,

29]. Conservative therapy using antibiotics or nasal corticosteroids is usually ineffective but may temporarily alleviate symptoms (e.g., preoperatively) [

30].

The primary aim of the study was to determine LMS on CT and correlate it with treatment modality in OCRS patients treated between 2012 and 2022. The study assessed whether higher LMS values were associated with indication for ESS versus dental management alone. Additional goals included identifying the underlying dental cause and evaluating reported symptoms, with analysis of their impact on treatment choice. OCRS patients were compared with a control group of patients with unilateral CRS of non-odontogenic origin.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 2067 patients with CRS examined between 2012–2022 were identified. Among them, 86 had unilateral localized CRS. Based on history, clinical examinations (ENT and dental), and CT findings, 61 patients were diagnosed with OCRS. Four patients were excluded due to incomplete CT documentation, leaving 57 for final analysis. The remaining 25 patients with unilateral CRS of non-odontogenic origin formed the control group.

In the OCRS cohort (n = 57, mean age 50.05 ± 15.50 years; 27 men, 30 women), CRS symptoms, dental pathology subtype, and LMS (calculated for the affected side only) were evaluated. Patients treated solely by dental intervention were compared with those treated surgically with FESS (with or without simultaneous dental surgery). In surgically treated patients, the proportion undergoing combined FESS and dental surgery and the specific teeth treated were recorded.

In the control group (n = 25, mean age 48.12 ± 19.12 years; 9 men, 16 women), LMS values were similarly assessed and compared between surgically and conservatively treated patients, as well as between the control group and the OCRS group. Conservative treatment consisted of topical corticosteroids and saline irrigation.

Statistical analyses included Mann–Whitney U test, Student’s t-test, chi-square test, and biserial correlation.

3. Results

During the study period, 61 patients with OCRS were treated, representing 3.0 % of all CRS cases. Among unilateral CRS cases, OCRS accounted for 69.5 %.

Of the 57 evaluated OCRS patients, 15 (26.3 %) were treated exclusively by dental intervention, while 42 (73.7 %) underwent ESS. All procedures were endoscopic; one case required supplementary Caldwell–Luc approach. In 21 patients (50 % of the surgical group), dental surgery (e.g., extraction, closure of chronic or acute oroantral fistula using a Wassmund flap) was performed during in one procedure. Most frequently extracted teeth were the first molar (9 cases), second molar (7 cases), and second premolar (5 cases).

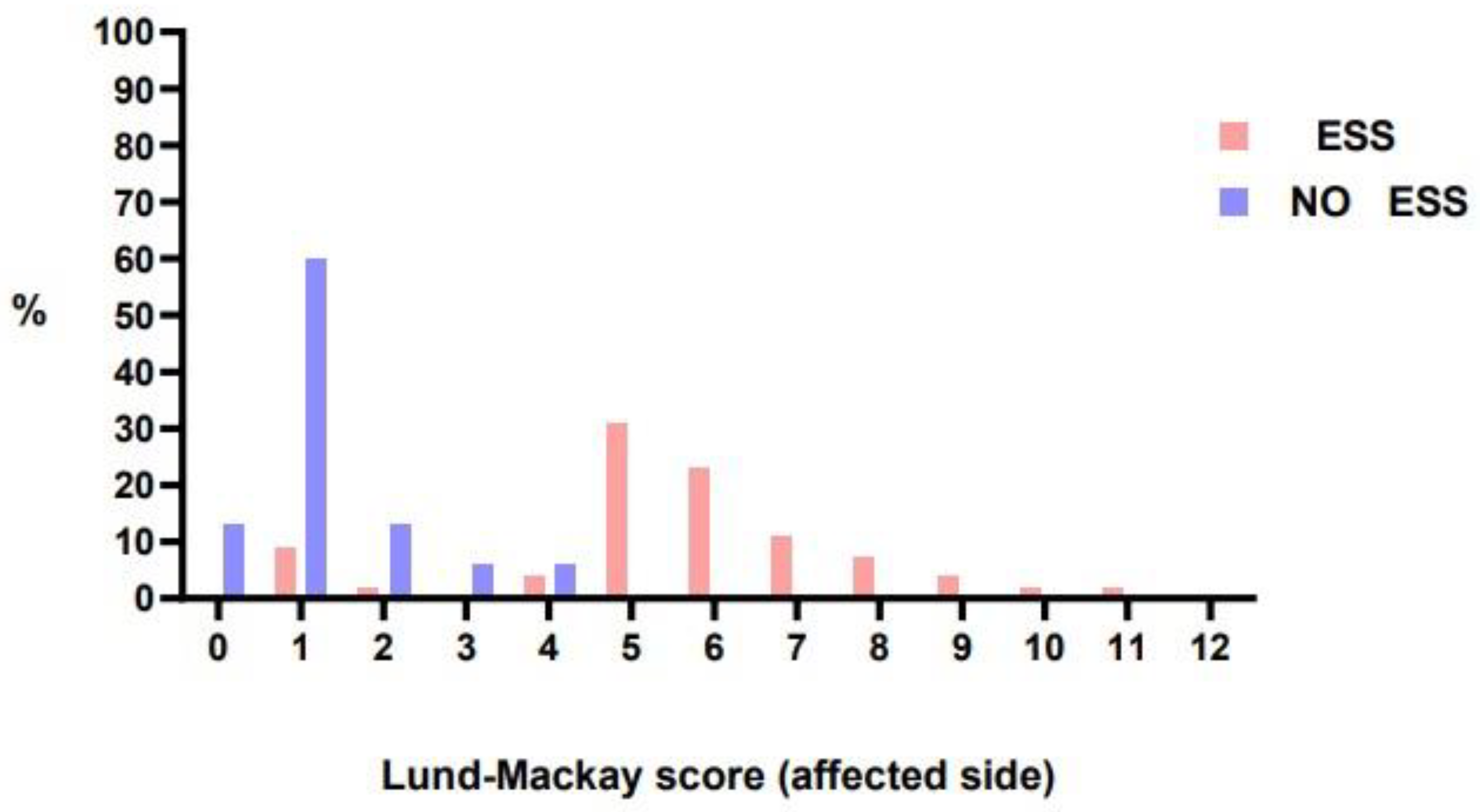

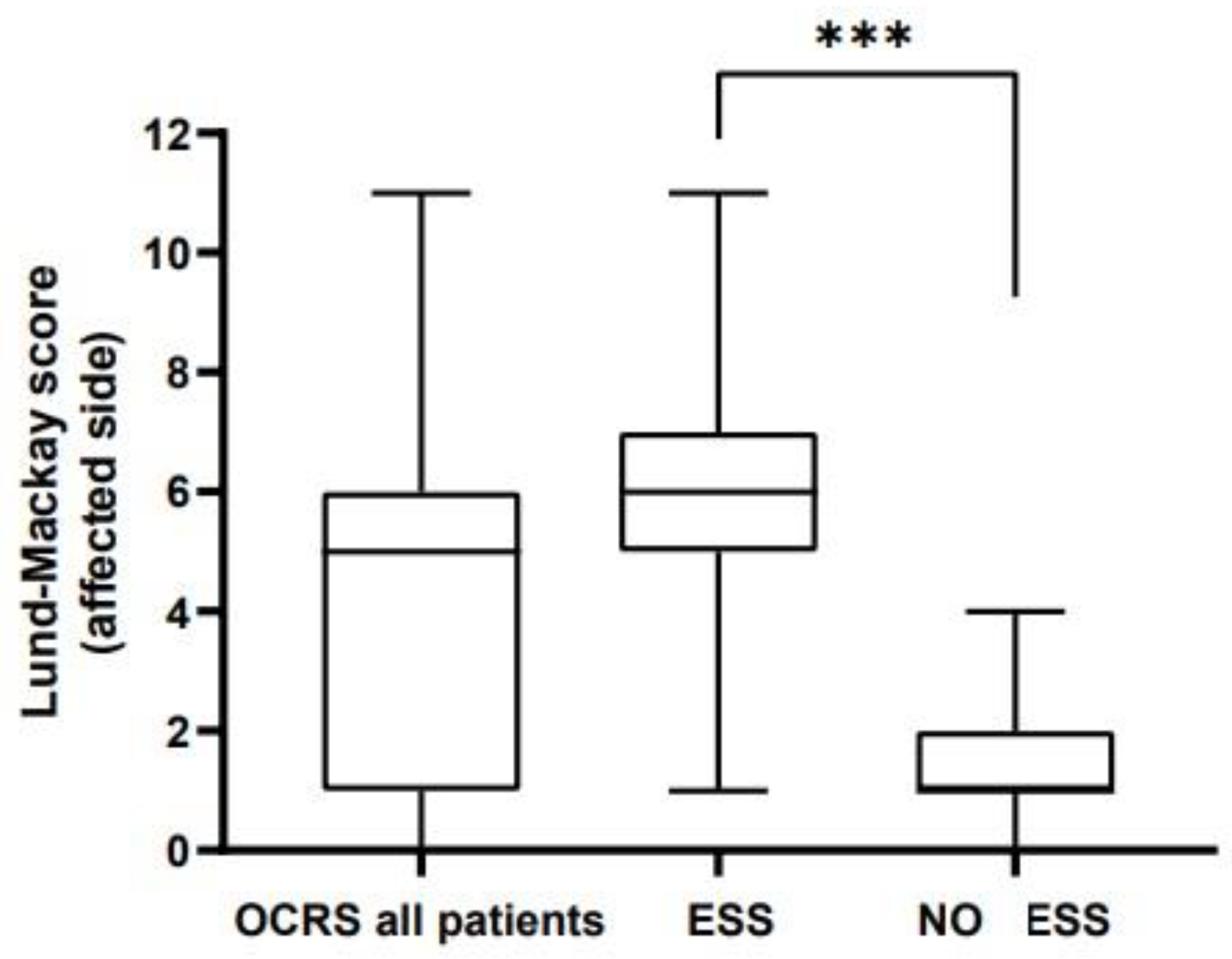

LMS on the affected side ranged from 1 to 11 in patients undergoing ESS (median 6). In contrast, LMS in patients not undergoing surgery ranged from 0 to 4 (median 1) and the difference was significant (

p < 0,001). (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

In the control group, 18 of 25 patients (72.0 %) underwent FESS; three procedures included septoplasty. LMS values for surgically treated patients ranged from 1 to 10 (median 3.5). Conservatively treated patients had LMS values between 1 and 7 (median 2).

The most frequently reported symptom was nasal discharge (46 patients, 80. 7 %), usually unilateral and malodorous. Facial pressure/pain occurred in 35 patients (61. 4 %), nasal obstruction in 21 (36.8 %), olfactory dysfunction in 3 (6 %), and facial swelling in 2 (4 %). Nasal discharge correlated positively with increasing LMS (p = 0.043), whereas nasal obstruction (p = 0.265) and pain (p = 0.712) did not. No significant relationship was found between treatment modality and symptoms.

The most common etiologies were periapical pathology (27 patients, 47.4 %), oroantral fistula (15 patients, 26.3 %), endodontic complications (7 patients, 12.3 %), implant-related inflammation (5 patients, 8.8 %), and retained tooth (3 patients, 5.3 %).

4. Discussion

During the study period, OCRS accounted for 3.0 % of all CRS cases—lower than values reported in the literature [

2,

3,

4,

5]. This may reflect a higher proportion of diffuse nasal polyposis cases at the tertiary care center. Within unilateral CRS, the proportion of OCRS (69.5 %) corresponded well with published data [

2,

23]. Age distribution and sex ratio also matched literature reports [

2,

27].

The primary finding was a statistically significant difference in LMS values between OCRS patients treated with FESS and those managed dentally only. Patients undergoing ESS had significantly higher LMS (p < 0.001).

The ostiomeatal complex appears to be a key factor: involvement of the maxillary sinus together with the ostiomeatal unit (and possibly other sinuses) suggests preference for ESS with simultaneous dental management [

27]. Prospective studies would be useful to validate whether selected patients with higher LMS may still be successfully treated with dental therapy alone. Some authors support an initial dental-only approach [

2], while others advocate primary ESS [

29].

Symptoms in our study—mainly nasal discharge and pain—reflect published patterns. Only nasal discharge correlated with LMS. No previous studies have evaluated symptom–LMS correlation specifically in OCRS. Future work could use visual analogue scales (VAS) for symptom severity.

The distribution of odontogenic causes was consistent with literature, though classification methods vary across studies. No significant relationship between type of dental pathology and treatment choice was observed.

The control group of patients with localized chronic rhinosinusitis of non-odontogenic etiology did not exhibit overall differences in LMS values compared with the OCRS group. Thus, the distribution of LMS scores was similar between the groups (p = 0.258). Within the control group itself, LMS values did not differ between surgically and nonsurgically treated patients (p = 0.412). While non-operated OCRS patients were referred for dental treatment, conservative management in the control group consisted of antibiotics, topical corticosteroids and saline irrigations.

5. Conclusions

To date, LMS has not been described as a criterion for treatment selection in OCRS. Based on our findings, LMS may help guide decision-making. CT findings appear more important than specific symptoms or dental pathology type. Involvement of the ostiomeatal complex seems crucial. When maxillary sinus disease does not extend to the ostium, dental treatment alone may be sufficient. When inflammation extends beyond the ostiomeatal unit into ethmoids or additional sinuses, primary FESS combined with dental surgery is likely more appropriate. Further studies are needed to validate these findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and K.Z.; methodology, K.Z.; software, J.F.; validation, P.S., K.Z., J.F. and M.S.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, K.Z., J.F., M.K., M.S.; resources, J.F., K.Z.. and M.K. data curation, K.Z. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z, P.S.; writing—review and editing, P.S; visualization, K.Z. and J.F.; supervision, P.S.; project administration, P.S and K.Z. ; surgery performed by P.S., K.Z. and J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project was approved by the local Ethical Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients signed informed consent for the use of anonymous data in a retrospective study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 0, 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martu, C.; Martu, M.A.; Maftei, G.A.; et al. Odontogenic Sinusitis: From Diagnosis to Treatment Possibilities—A Narrative Review of Recent Data. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecha, J.; Filipovský, T.; Betka, J.; et al. Chronic Rhinosinusitis of Dental Origin. Otorinolaryngol. Foniatr. 2022, 71, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Filleul, O.; Costa de Araujo, P.; et al. Chronic Maxillary Rhinosinusitis of Dental Origin: A Systematic Review of 674 Patient Cases. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2014, 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurchis, M.C.; Pascucci, D.; Lopez, M.A.; et al. Epidemiology of Odontogenic Sinusitis: An Old, Underestimated Disease, Even Today. A Narrative Literature Review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Psillas, G.; Papaioannou, D.; Petsali, S.; et al. Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis: A Comprehensive Review. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allevi, F.; Fadda, G.L.; Rosso, C.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2020, 35, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescia, G.; Alessandrini, L.; Bacci, C.; et al. Odontogenic Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Structured Histopathology Evidence in Different Patho-Physiological Mechanisms. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, S. Oroantral Communications and Oroantral Fistula. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. 2021, 491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M. Definition and Management of Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2019, 41, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taschieri, S.; Torretta, S.; Corbella, S.; et al. Pathophysiology of Sinusitis of Odontogenic Origin. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2015, 8, e12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, M.; Bulfamante, A.M.; Pipolo, C.; et al. Odontogenic Sinusitis and Sinonasal Complications of Dental Treatments: A Retrospective Case Series of 480 Patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimigean, V.R.; Nimigean, V.; Maru, N.; et al. The Maxillary Sinus and Its Endodontic Implications: Clinical Study and Review. B-ENT 2006, 2, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Cho, K.M.; Park, S.H.; et al. Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis Caused by Root Canal Overfilling of Calcipex II. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2014, 39, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalek, P. Rinosinusitidy., 1st ed.; Mladá fronta: Praha, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas Júnior, O.; Moura, L.; Sonego, C.; et al. Unusual Case of Sinusitis Related to Ectopic Teeth in the Maxillary Sinus Roof/Orbital Floor. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2016, 9, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noleto, J.; Prado, R.; Rocha, J.; et al. Intranasal Inverted Tooth: A Rare Cause of Persistent Rhinosinusitis. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2013, 24, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyvas, D.; Kapsalas, A.; Paikou, S.; et al. Thickness of the Schneiderian Membrane and Its Correlation with Anatomical Structures and Demographic Parameters: A CBCT Study. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2018, 4, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.T.; Wang, S.H.; Liou, M.L.; et al. Microbiota Dysbiosis in Odontogenic Rhinosinusitis and Its Association with Anaerobic Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin-Kassab, A.; Bhargava, P.; Tibbetts, R.J.; et al. Comparison of Bacterial Maxillary Sinus Cultures Between Odontogenic Sinusitis and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 11, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuokko-Landén, A.; Blomgren, K.; Suomalainen, A.; et al. Odontogenic Causes Complicating the Chronic Rhinosinusitis Diagnosis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 25, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Min, J.Y.; et al. Endodontic Treatment: A Significant Risk Factor for the Development of Maxillary Fungal Ball. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 3, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauman, C.H.J.; Chandler, N.P.; Tong, D.C. Endodontic Implications of the Maxillary Sinus: A Review. Int. Endod. J. 2002, 35, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.E.; Long, C.M.; Loehrl, T.A.; et al. Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Review of the Current Literature. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2018, 3, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, V.J.; Mackay, I.S. Staging in Rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 1993, 31, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zinreich, S.J. Imaging for Staging of Rhinosinusitis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2004, 113, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodu, E.J.; Fasunla, A.J.; Akano, A.O.; et al. Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Correlation of Symptoms with CT Findings. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, P.; Tvrdý, P.; Pink, R.; et al. Současný Pohled na Možnosti Terapie Maxilární Sinusitidy Odontogenního Původu. LKS 2017, 27, 238–242. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J.R.; McHugh, C.I.; Griggs, Z.H.; et al. Optimal Timing of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Odontogenic Sinusitis. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L.; Pierri, M.; Iafrati, F.; et al. Odontogenic Sinusitis from Classical Complications and Its Treatment: Our Experience. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).