1. Introduction

The importance of virtual simulations in teaching has increased over the years and is increasingly recognized and valued in the educational field [

1]. These tools are considered technological resources capable of offering a wide variety of benefits and opportunities that enrich teaching. Access to realistic studies is improved, since, in the face of potential difficulties in gaining direct experience with industrial equipment, students can enter detailed virtual environments to explore complex machines or scientific phenomena by simulating experiments, observing internal processes, or visualizing natural events.

Furthermore, virtual simulations support inquiry-based learning, allowing students to directly interact with engineering principles through active experimentation. Rather than passively absorbing lessons on kinematic chains or torque transmission, students manipulate variables such as pulley ratios and observe the resulting mechanical behaviors in real time through a screen. This hands-on approach allows them to witness cause-and-effect relationships, interpret simulation outputs, and iteratively adjust their models, thereby developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Particularly when exploring failure modes, as these environments prove invaluable in practice, students can challenge conditions such as misaligned clamps, overloaded bearings, or insufficient lubrication to visualize the mechanics of failure and internalize good maintenance practices long before handling physical equipment [

1,

2].

Interactive and participatory learning is enhanced through virtual recreations, increasing student motivation and engagement. Furthermore, flexibility and adaptability allow students to access the material individually, at any time, and from any location. Risk-free experimentation is another key aspect, as although real machines incorporate safety mechanisms, an inexperienced person can still face danger; virtual models completely eliminate that risk. Another important factor is that these tools allow for continuous updating and adaptation to technological advances [

3], ensuring that the educational content remains relevant. In universities, engineering and design curricula have long grappled with the limitations of physical workshops: expensive equipment, safety concerns, limited machine availability, and the costs of inputs such as tools, lubricants, and materials [

1,

2]. Virtual models of machine tools such as lathes, milling machines, drill presses, or hydraulic presses overcome these barriers by offering students high-fidelity, interactive simulations accessible from laptops, tablets, or virtual reality labs. A mechanical engineering student can virtually mount a cutting tool, adjust spindle speed, vary feed rate, and observe chip formation, surface finish, and stresses on the tool, all without risk of injury or damage to the machine. By repeating experiments at no additional cost and instantly visualizing internal forces, temperature distributions, and vibration modes, students gain a deep and intuitive understanding of machining principles that complements the theoretical content [

4,

5].

The educational, cultural, and economic benefits of virtual recreations are mutually reinforcing. Universities reduce investment and operating costs by moving part of their laboratory instruction to virtual environments; museums expand their reach and impact without putting fragile artifacts at risk; researchers gain a non-destructive testing bench for engineering analysis [

6]. Virtual laboratories do not consume cutting fluids, generate metal chips, or require safety shutdowns. This supports sustainability goals while protecting institutional budgets.

By achieving these goals, the work will provide an effective and innovative teaching tool, allowing educators and students to acquire practical knowledge about the fundamentals of machine tools. In turn, this contributes to safeguarding industrial heritage, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration, and preparing future professionals to innovate responsibly in a world where the interaction between physical artifacts and digital representations is becoming increasingly important in education, culture, and research. The integration of virtual recreations into both university education and museum practice is redefining the way industrial heritage is taught, learned, and preserved [

7].

In museum settings, virtual recreations transform static exhibits into living experiences. An early 20th-century column drill, motionless behind a display case, becomes comprehensible when visitors use an augmented reality application [

8,

9] or a touchscreen to animate its moving mechanism, view exploded diagrams, and even “operate” the machine under guided supervision. This interactivity positively engages diverse audiences such as students, families, and apprentices, turning observation into participation. Potential uses in games (gamification) attract younger visitors, who are more accustomed to digital interfaces, prolonging their stay and deepening their connection with industrial history [

10]. As the debate about the role of digital technologies in museums and cultural institutions continues, the concept of “augmented realism” is closely linked to emerging technologies that seek to minimize the perceived gap between the viewer and the experience itself [

11]. From this perspective, it is anticipated that digital tools will be seamlessly and deeply integrated into the museum environment, eventually eliminating any distracting effects they may initially have caused [

12].

Among the various heritage categories, this paper focuses on industrial heritage. This specific type of heritage, internationally recognized as a distinct modality, possesses unique characteristics that differentiate it from other forms of heritage. For example, many of the movable and immovable assets classified as industrial heritage are relatively recent compared to other categories [

13]. Furthermore, rapid technological advances have continuously transformed industrial activity, leaving a tangible record of these changes in remarkably short periods [

14]. Historical and cultural heritage represents an expression and testimony of collective and social identity. Therefore, it is crucial to promote studies that examine this heritage, analyzing its historical and cultural dimensions. This approach aims to preserve and transmit valuable knowledge that, if not documented, risks being lost over time [

15].

Industrial transformation also gave rise to significant social changes and movements, which are closely related. These aspects increase interest in the study of industrial heritage, allowing us to connect machinery and equipment with their historical context. This includes the analysis of the technology used, the social dynamics, and the corresponding historical period. In this context, the unique characteristics of industrial heritage make it a particularly attractive subject of study compared to other heritage categories [

16,

17].

The digital realm has great potential to revolutionize how individuals interact with heritage in its broadest sense. This topic has been a central focus of academic debates and cultural initiatives. On the one hand, the internet has been highlighted as a powerful platform for raising awareness of the heritage sector, fostering greater interest and encouraging in-person visits, especially to museums. On the other hand, digital environments have been proposed as dynamic and interactive spaces that allow for two-way communication with cultural heritage, complementing and enriching the physical experience. A key question for researchers and managers involved in the study or management of heritage, history, and its cultural significance is to identify the intrinsic value that interaction with digital tools brings to these experiences [

18].

Virtual heritage also democratizes access [

19]. A specialized machine tool, located in a technical museum in another country or region, can be shared globally through web portals or virtual reality platforms [

20]. Distance learning students, researchers, and enthusiasts from anywhere in the world gain 24/7 access to the same interactive model, equalizing educational opportunities and fostering international collaboration. Instructors integrate these resources into online courses, enabling hybrid and fully remote programs that maintain practical rigor through virtual laboratories. The selection of a machine or facility for 3D modeling will be based on several criteria, such as its educational relevance, historical and cultural significance, historic location [

21,

22], advances in energy efficiency [

23], or its association with a recognized figure, which may have made it an iconic object [

24]. These three-dimensional representations provide heritage managers with a valuable tool for developing sustainable and economically viable reuse strategies for the industrial heritage under consideration. The introduction of computer numerical control marked a milestone in industrial automation, but also represents a threat to the recognition and preservation of the tools that laid the foundations of modern manufacturing [

25].

Digital modeling has emerged as a valuable solution for preserving the legacy of these industrial machines. The ability to create accurate virtual recreations of historic machines allows not only to preserve their physical appearance but also to document their operating principles and their role in the evolution of engineering and manufacturing [

26]. The study of the manufacturing industry has greatly benefited from advances in current 3D design software, which allows remote analysis of the mechanisms inherent in machinery. From a research and preservation perspective, virtual recreations act as dynamic archives. Detailed 3D scans, combined with metadata (date of manufacture, material properties, maintenance records) and sensors, create a digital twin that can be analyzed to verify its structural integrity, simulated under different loading conditions, or tested for energy efficiency improvements prior to any intervention on the machine itself [

27]. Heritage managers use workflows based on building information models to plan the adaptive reuse of industrial sites, exploring virtual factory layouts, assessing material deterioration, and visualizing new architectural works without compromising historical authenticity [

28].

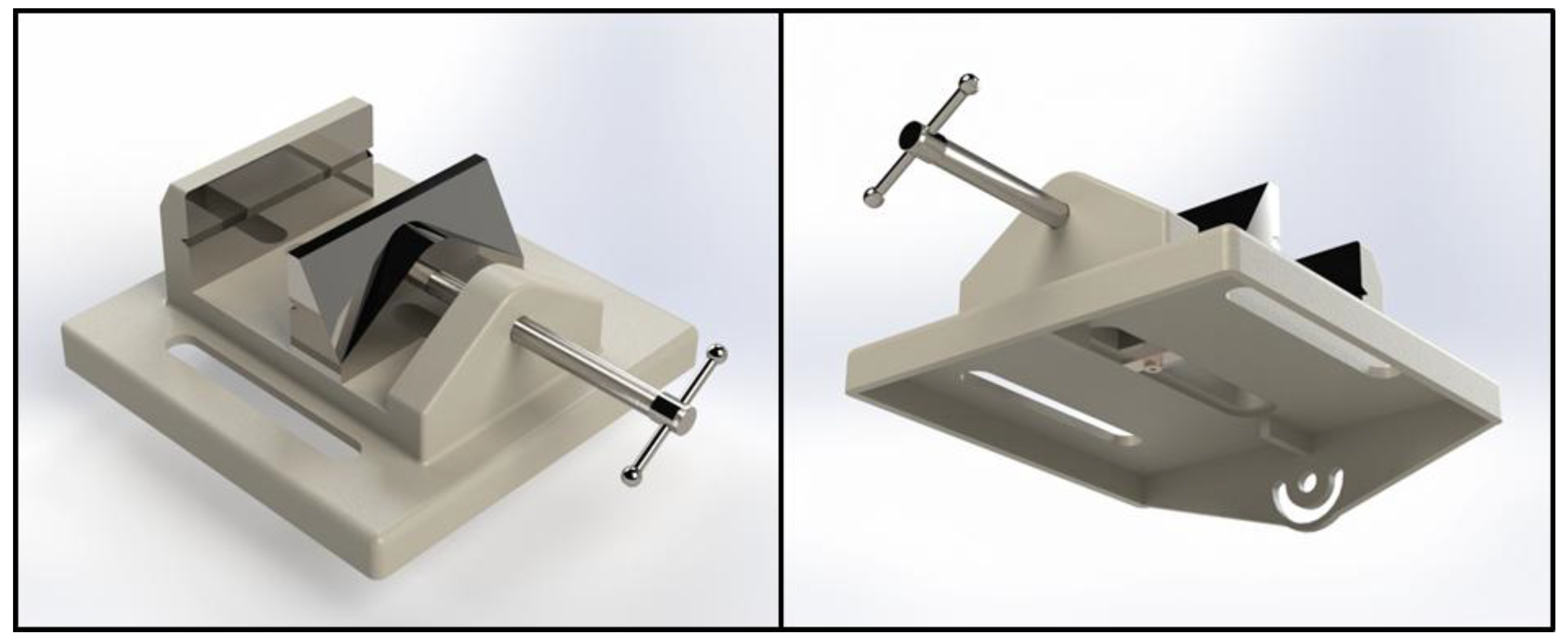

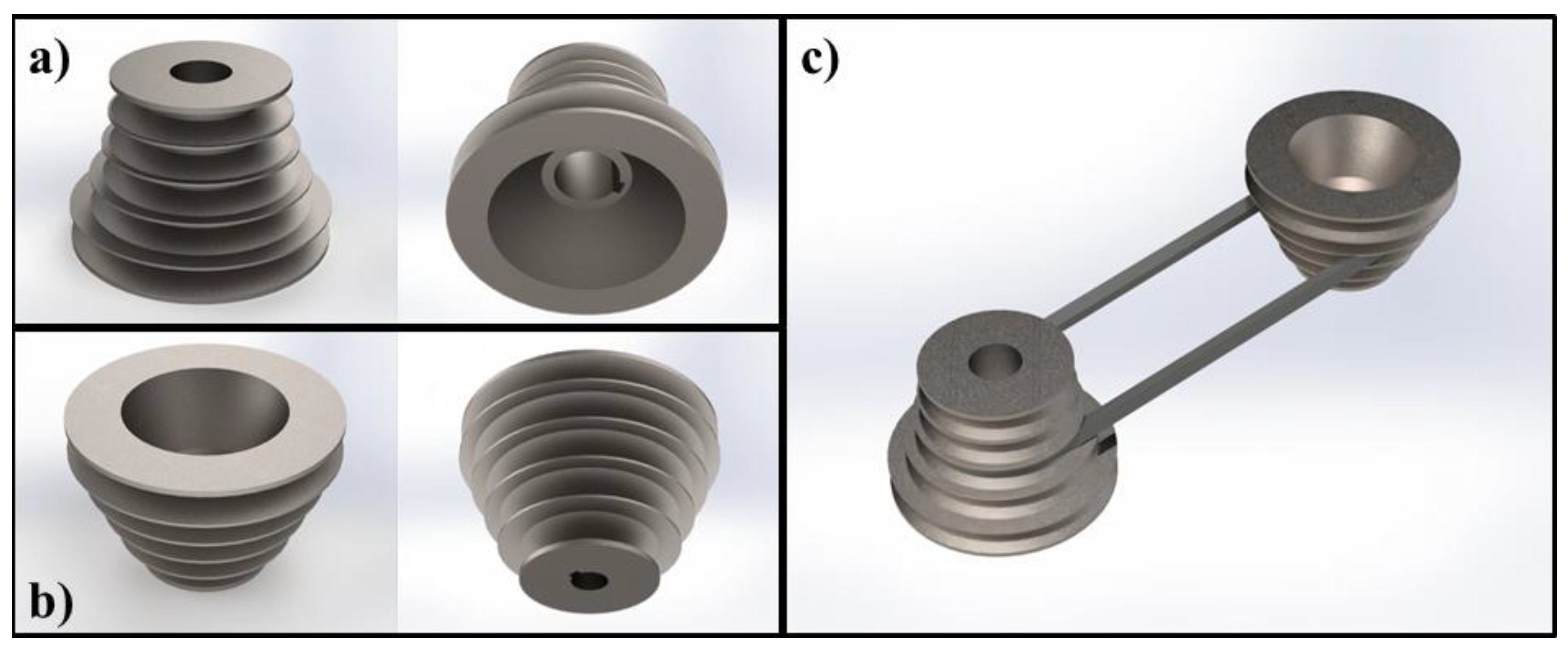

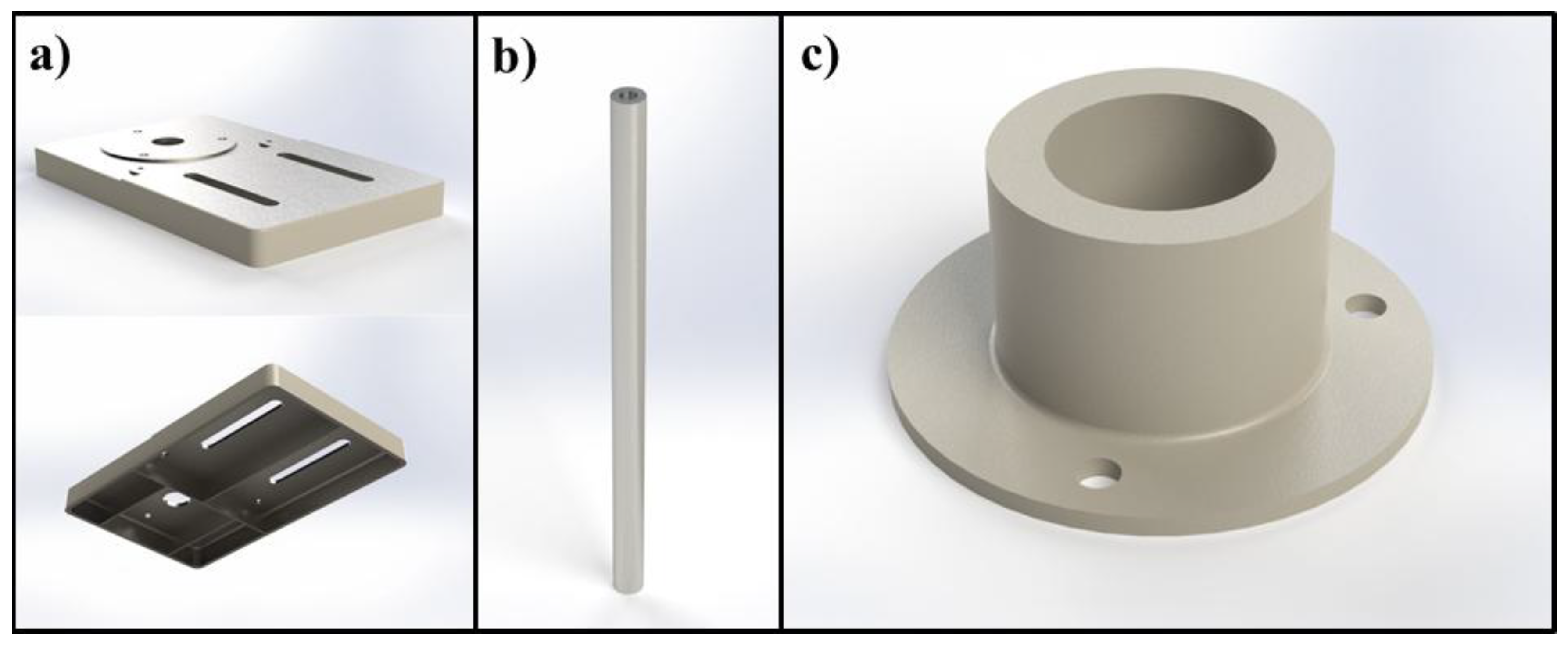

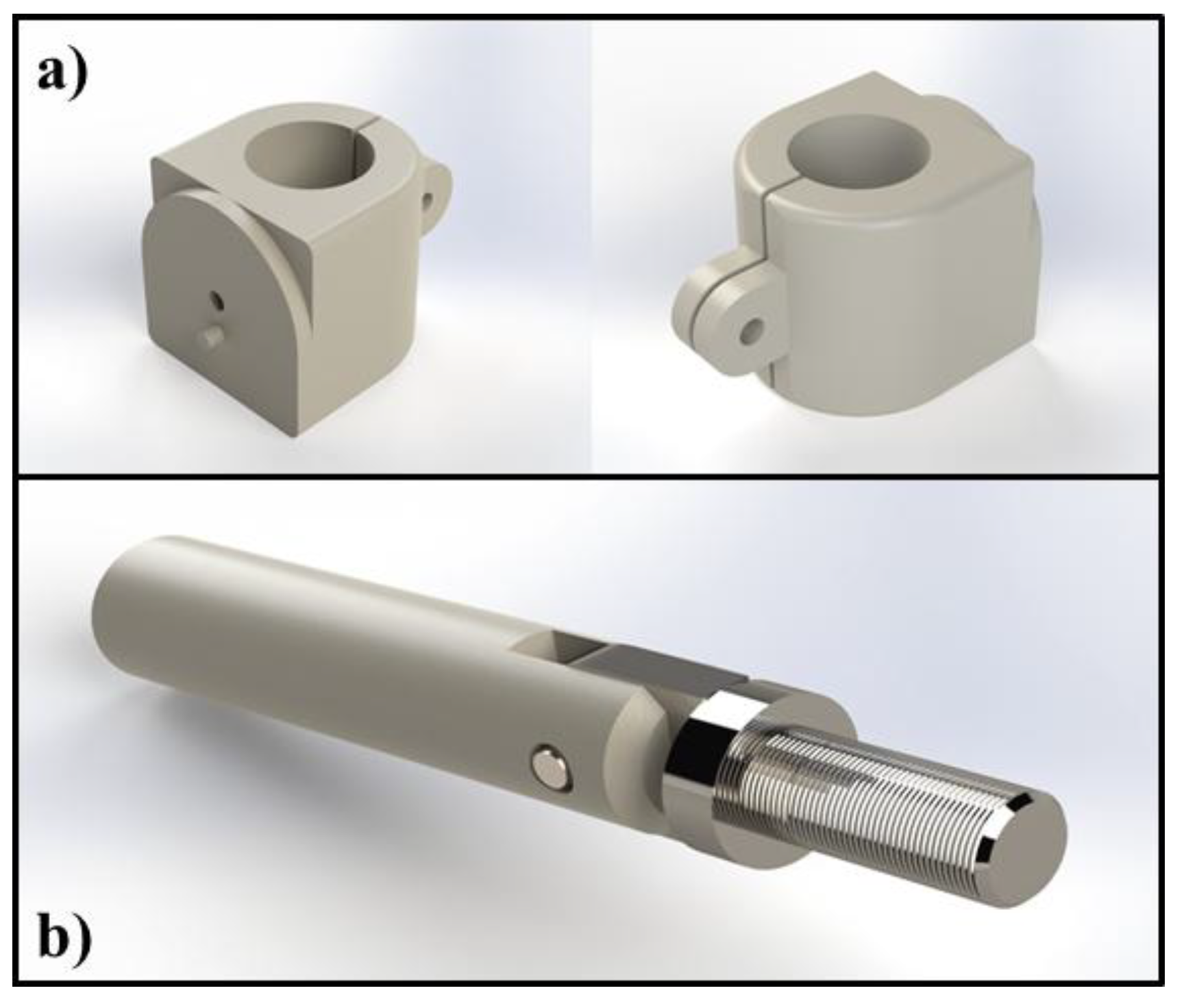

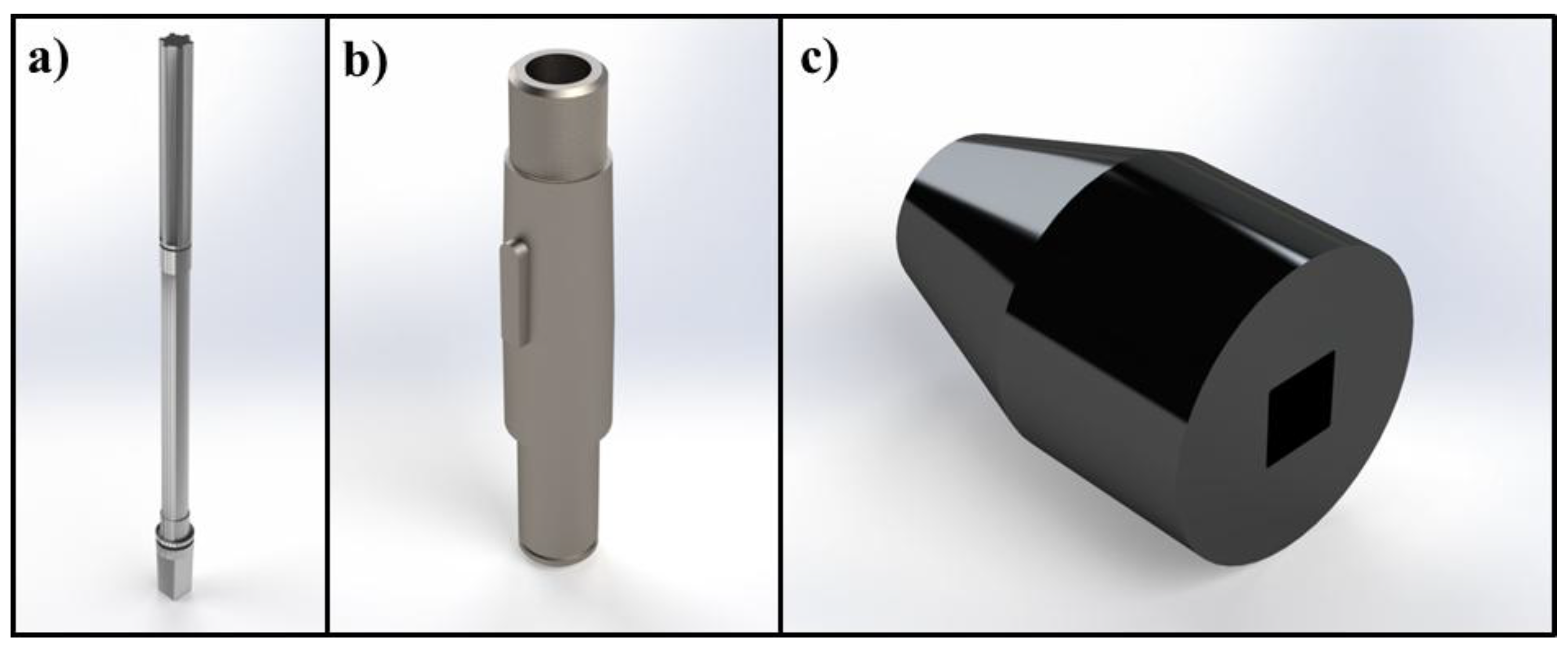

This work seeks to apply one of these tools to create a three-dimensional model of a manual drill press. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to understand and analyze the operation of a drill press by creating a virtual recreation. This recreation aims to virtually create the parts that make up this machine tool. In this way, a deeper understanding of this machine tool can be achieved without the need for its physical presence. Drill presses are widely used in industry to perform precise drilling operations in various solid materials, including metals, wood, and plastics. These machines possess distinctive features that make them highly effective for specific applications. Some of their notable qualities include accuracy, drilling capacity, control and adjustability, safety, and versatility.

2. Drill Press Identification

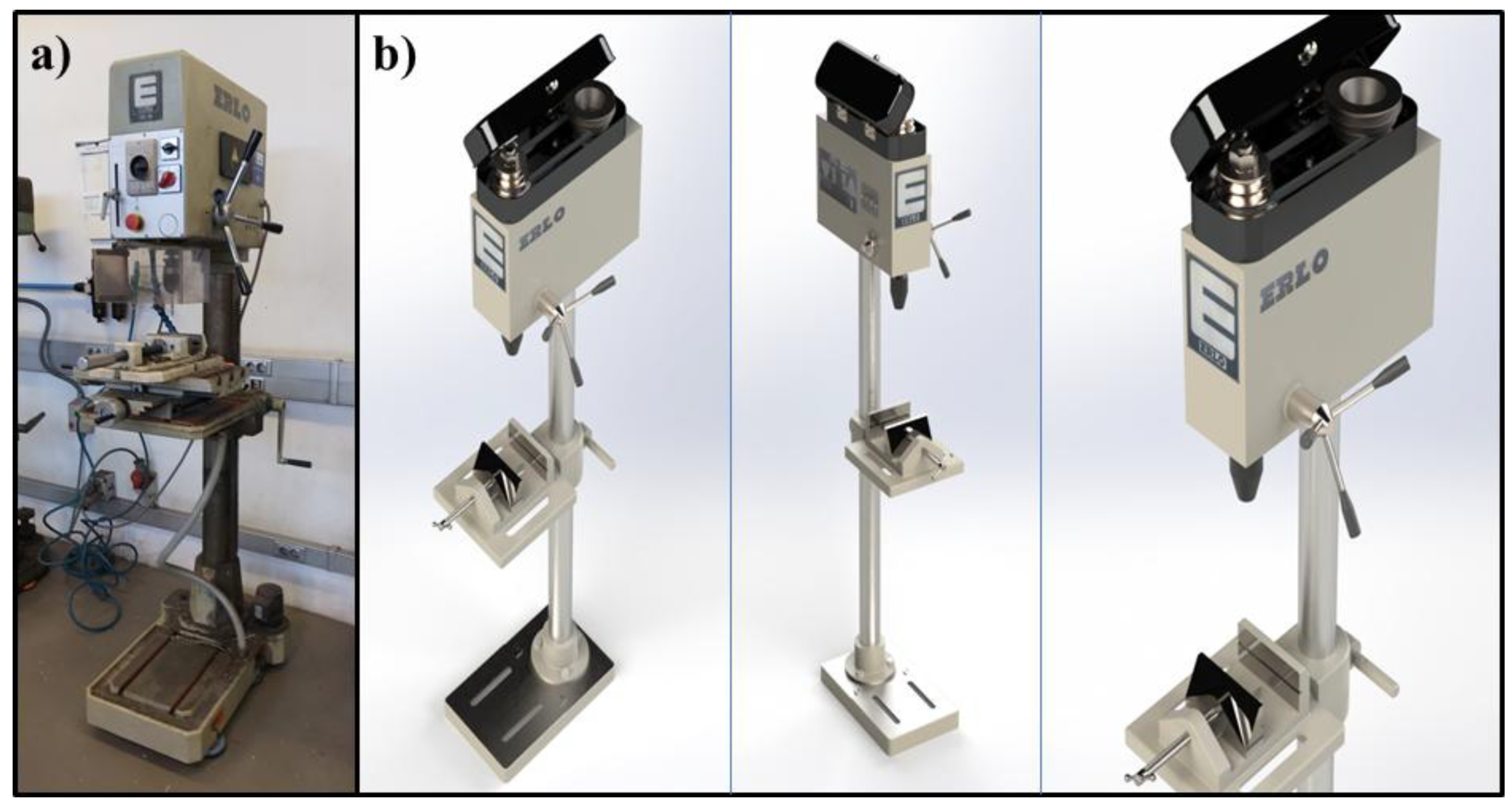

The company Erlo S.A. was founded in Spain in 1961 and has specialized in manufacturing high-quality drills, tapping machines, and machining centers. Its range of column drills has been widely used in the mechanical, metallurgical, and manufacturing industries. The CR-18 model,

Figure 1, is a manually operated column drill designed for precision work in workshops and industrial environments. The digitized drill press model dates back to the 1990s, although its original design is older. Known for its robustness, reliability, and precision, the CR-18 has been extensively used across various industrial sectors. Over time, drill designs have evolved to incorporate automated controls and CNC systems. However, the CR-18 remains highly valued in environments where precise manual control and durability are essential.

The CR-18 is a manually fed column drill, suitable for machining metal, plastic, and other materials. It has a drilling capacity of up to 18 mm in steel and features a manual feed with a belt-driven transmission, allowing easy speed adjustment depending on the material. To ensure structural stability, it has a 100 mm column diameter and can accommodate workpieces with a 250 mm spindle-to-column distance.

The worktable is height-adjustable, and the spindle speed can be fine-tuned, making it adaptable for different materials. It has a maximum drilling depth of 120 mm, allowing for deep drilling operations. The motor power is 500 Watts, and its weight of approximately 280 kg ensures stability and precision during operation. Additionally, its compact dimensions (655 × 400 × 1900 mm) make it well-suited for industrial workshops.

Machines like the Erlo CR-18 are considered part of industrial heritage for several reasons:

• Historical and technological significance: They mark a milestone in the evolution of machining and industrial production.

• Role in manufacturing: These machines were fundamental in workshops and factories, playing a crucial role in producing mechanical components.

• Durability and design: Built to last, many of these machines are still in operation decades after their manufacture.

• Engineering evolution: They demonstrate the technological shift from manual operation to automation and CNC (computer numerical control).

Preserving such machines allows us to study the history of engineering, understand past production methods, and appreciate the impact of industrialization on society. The Erlo CR-18 stands as a classic column drill, renowned for its reliable design and widespread use in metalworking industries and machine shops. Its recognition as industrial heritage stems from its historical and technological significance, representing a key stage in the development of mechanical tools over time. Materials

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed a complete digital model of a manually operated vertical drill press, demonstrating the potential of virtual recreation as a tool for industrial heritage preservation and education. By utilizing advanced 3D modeling techniques in SolidWorks, this research has provided a detailed and interactive representation of a historically significant machine, enabling a deeper understanding of its mechanics, components, and operational principles. The digital reconstruction of historical machine tools offers an effective means of preserving their legacy, ensuring that valuable knowledge about past manufacturing processes is not lost to technological obsolescence.

Additionally, the virtual model serves as an accessible and interactive educational resource, allowing students and professionals to explore the structure and function of the drill press without requiring physical access to the machine. This enhances teaching methodologies in technical and engineering education, particularly in resource-limited environments. Moreover, by replacing hands-on training with virtual simulations, the risks associated with operating heavy machinery are significantly reduced, enabling safe experimentation, especially for inexperienced users, while also offering greater flexibility in learning.

Beyond educational benefits, the methods employed in this study can be extended to other industrial machines, facilitating the creation of virtual museums. The integration of augmented or virtual reality could further enhance the immersive experience of interacting with these digital heritage assets. As technology continues to evolve, adopting virtual recreations in historical and educational contexts will become increasingly relevant, bridging the gap between past and present manufacturing knowledge. Future research could explore expanding this approach by incorporating dynamic simulations or haptic feedback systems to create more comprehensive and engaging educational experiences.