1. Introduction

The Future–Mass Projection (FMP) framework replaces particle dark matter by a nonlocal mapping from baryonic to effective gravitating mass. In its covariant formulation this mapping is encoded in a bitensor kernel

on a closed time path (CTP) of finite temporal width

. In the Newtonian limit and in static, axisymmetric configurations one expects this kernel to reduce to a configuration–independent linear operator acting on the surface density of the baryonic disc,

with

the projected “future mass” contribution that plays the role of an effective dark component in the Poisson equation. Previous FMP studies have implemented (

1) with simple phenomenological kernels and have shown that Milky Way and SPARC rotation curves can be reproduced without particle dark matter over a wide range of galaxy types, provided the kernel satisfies a radial zero–DC condition and does not spoil Solar System tests.

However, the structure of remains poorly constrained from first principles. In particular, the relation between the covariant CTP kernel and the Newtonian kernel used in galactic fits is not yet understood beyond a schematic level. Moreover, previous attempts to label certain kernel shapes as “entropic” have lacked a systematic statistical or thermodynamic underpinning.

In this work we propose a more disciplined, but still exploratory, organisation of the Newtonian FMP kernel in terms of a coarse–grained entropy functional on the space of axisymmetric surface density profiles . The central idea is to construct a background–dependent linear–response kernel from the Hessian of an entropy–like functional around a chosen background disc . The resulting kernel is linear in fluctuations but state–dependent, and hence should be viewed as a surrogate for the Newtonian limit of the full CTP kernel, not as a fundamental derivation.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In

Section 2 we define the coarse–grained entropy functional and its sign convention, and derive the corresponding Hessian.

Section 3 introduces a simple Gaussian model for the radial weight and covariance kernel and defines the background–dependent entropic kernel

. In

Section 4 we apply this construction to an exponential Milky Way–like disc, enforce the radial zero–DC condition, and compute representative entropic boost factors

.

Section 5 discusses the limitations of the Gaussian closure, the state dependence of the kernel, and the tentative connection to the CTP horizon

. We conclude in

Section 6.

2. Coarse–Grained Entropy Functional and Linear Response

2.1. Configuration Space and Sign Convention

We consider axisymmetric, time–averaged baryonic surface density profiles

on the disc plane, with

R the cylindrical radius. The total baryonic mass is

We define a coarse–grained functional

on this configuration space which will play the role of an entropy potential. To avoid confusion with physical entropy we explicitly distinguish

so that a local maximum of the physical entropy

corresponds to a local minimum of

S. With this convention the Hessian of

S is positive semidefinite at entropy–maximising configurations, which is convenient for linear response.

2.2. Local Term

The simplest local contribution to

S that respects positivity and is compatible with a Boltzmann–Gibbs form is

where

is a reference surface density and

is a radial weight function that encodes how strongly local entropy variations couple to the nonlocal kernel. The first functional derivative is

and the second functional derivative is

Evaluated at a background configuration

this Hessian is positive definite wherever

, as desired.

The reference density drops out of the Hessian and hence does not affect the linear–response kernel. It does however enter the first variation and would therefore influence any attempt to determine equilibrium profiles from a variational principle. Since in the present work we only use S as a generator of the Hessian around a given background disc, we treat as an arbitrary constant and do not attempt to interpret S as a full thermodynamic potential.

2.3. Pair Term and Gaussian Approximation

To encode finite–range correlations between fluctuations at different radii we add a pair term of the form

where

denotes fluctuations around the background and

is a symmetric, positive semidefinite kernel that we interpret as the inverse covariance. The corresponding Hessian is

which is again positive semidefinite by construction.

In a Gaussian statistical closure the probability functional for fluctuations

around

can be written as

so that

is the covariance of

in this approximation. Higher–order cumulants are neglected. In reality, late–time gravitating systems are known to exhibit non–Gaussian density statistics, and we will later estimate the size of cubic corrections.

2.4. Linear–Response Kernel from the Hessian

Combining the local and pair contributions we obtain the total Hessian evaluated at the background disc

,

This kernel is positive semidefinite under the assumptions stated above.

We now define a background–dependent “entropic” linear–response kernel as

with

an overall normalisation constant that absorbs both the fluctuation amplitude and any dimensional factors. The entropic contribution to the FMP source is then written as

where

will be modelled in terms of

below. Note that

and

are explicitly

background–dependent; this is a central conceptual feature of the present construction and differs from the configuration–independent kernel assumed in the covariant FMP formulation.

3. Radial Weight and Covariance Model

3.1. Small Fluctuations and Effective Amplitudes

We restrict attention to small fractional fluctuations around the background disc,

with a dimensionless shape function

. In the numerical example below we will adopt

for simplicity, so that

is proportional to the background disc but suppressed by the small parameter

.

Inserting the model (

10) into (

11) and combining constants, we parametrise the entropic kernel as

where the effective amplitudes

and

absorb

,

and any numerical factors from the Hessian. Explicitly, one may write

with

dimensionless constants of order unity. For our purposes it is sufficient to work directly with

and

, which will later be recast in a dimensionless form adapted to the exponential disc.

3.2. Dimensionless Variables for Exponential Discs

We consider an exponential background disc

with central surface density

and scale length

. Introducing the dimensionless radius

we write

and define dimensionless kernels

The entropic kernel becomes

where we have introduced the dimensionless combinations

with

a dimensionless measure of the covariance amplitude defined below. The numerical values of

and

will be fixed by phenomenological input and by the radial zero–DC condition.

3.3. Radial Weight Function

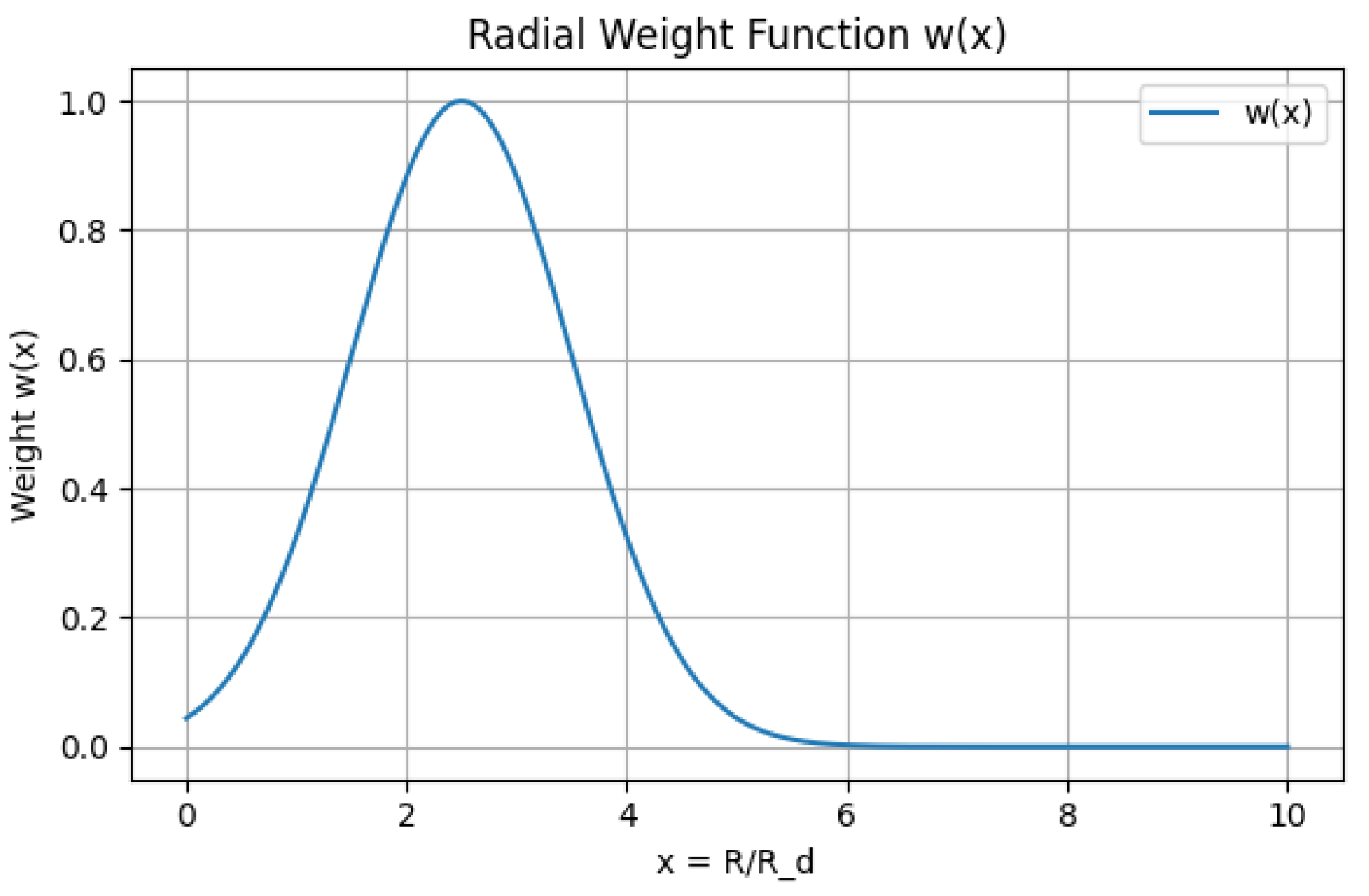

Motivated by the idea that entropic leverage should be largest in the intermediate disc where phase–space mixing is most efficient, we adopt a Gaussian radial weight,

centred at dimensionless radius

with width

. In the Milky Way application below we will choose

and

, corresponding to a maximum in the entropic weight near

and a gentle decay towards both smaller and larger radii. This reflects the expectation that the very inner disc is dynamically hot and dominated by the bulge, while the outer disc is too sparse to support strong correlations.

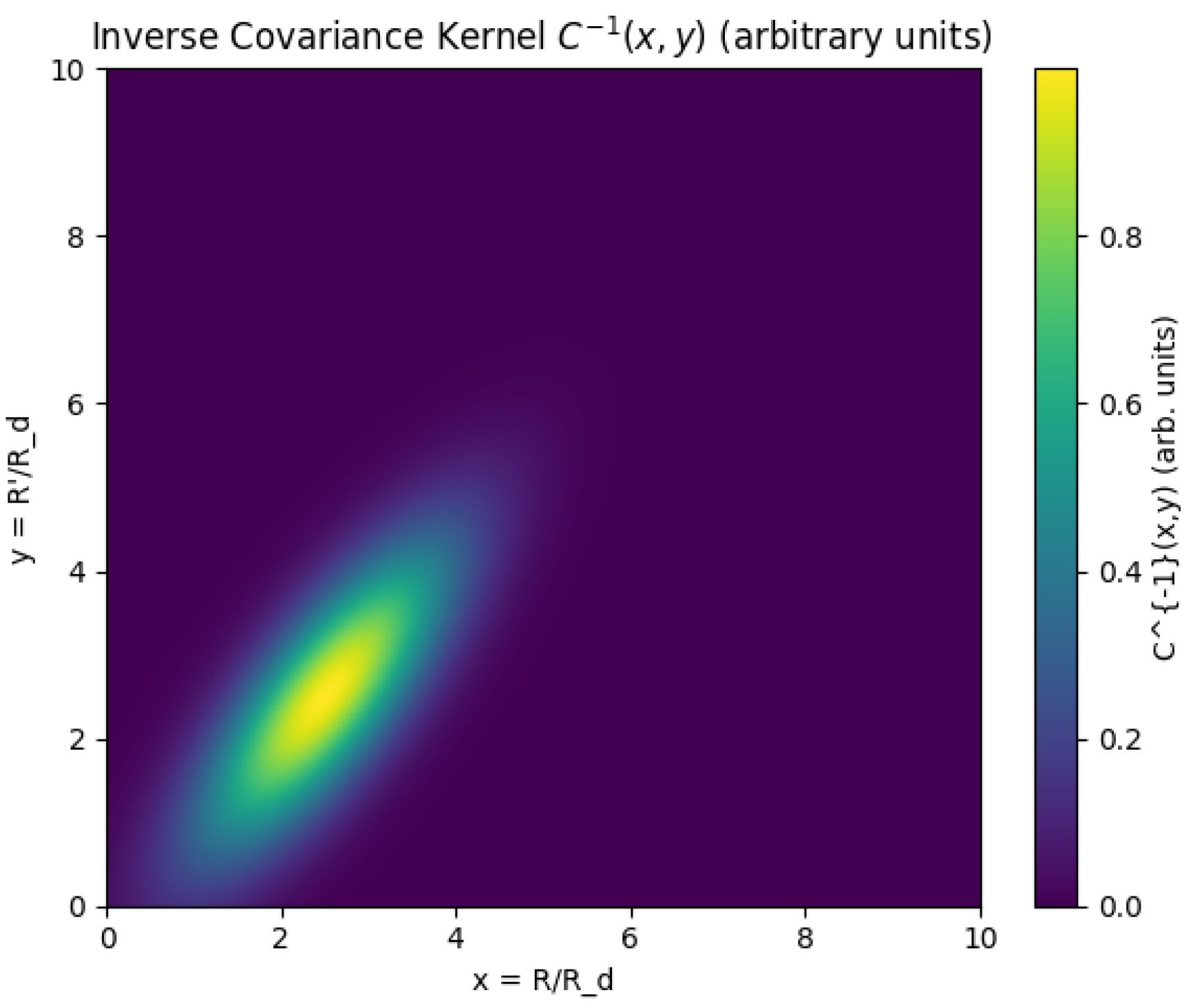

3.4. Gaussian Covariance Kernel

For the inverse covariance kernel we adopt a Gaussian form in the radial separation, modulated by the same radial envelope as

,

where

is a dimensionless correlation length. The overall amplitude has been absorbed into

in the definition of

above. The Gaussian in

encodes short–range radial correlations, while the envelope in

x suppresses couplings far from the entropically active region around

.

Figure 1 shows the radial weight

for our fiducial parameters

.

Figure 2 displays the corresponding inverse covariance kernel

, which is strongly peaked along the diagonal

and localised around

. Both figures are generated on a dimensionless grid

.

4. Application to a Milky Way–like Disc

4.1. Fiducial Disc Parameters

For definiteness we adopt a simple exponential disc model for the Milky Way with

These values are representative of standard Milky Way mass models. The entropic parameters are chosen as

For the amplitude combinations we adopt

which, together with a fluctuation amplitude

and a covariance strength

, correspond to effective amplitudes

and

consistent with the zero–DC condition discussed below. The precise numerical values are not unique but fix a concrete benchmark.

4.2. Radial Zero–DC Condition

The FMP kernel must satisfy a radial zero–DC condition to avoid changing the total baryonic mass when integrated over radius. For the entropic contribution this translates into

Inserting the parametrisation (

14) with

and using the exponential disc background, the condition (

26) reduces to

with

For the Gaussian model of

Section 3, and the fiducial parameter choices given above, a straightforward numerical evaluation yields

The zero–DC condition then fixes the ratio

Expressed in terms of the dimensionless amplitudes this is compatible with the benchmark values (

25) for an appropriate choice of

, as stated above. In this way the zero–DC condition removes one free degree of freedom and correlates the local and nonlocal parts of the entropic kernel for the chosen background disc.

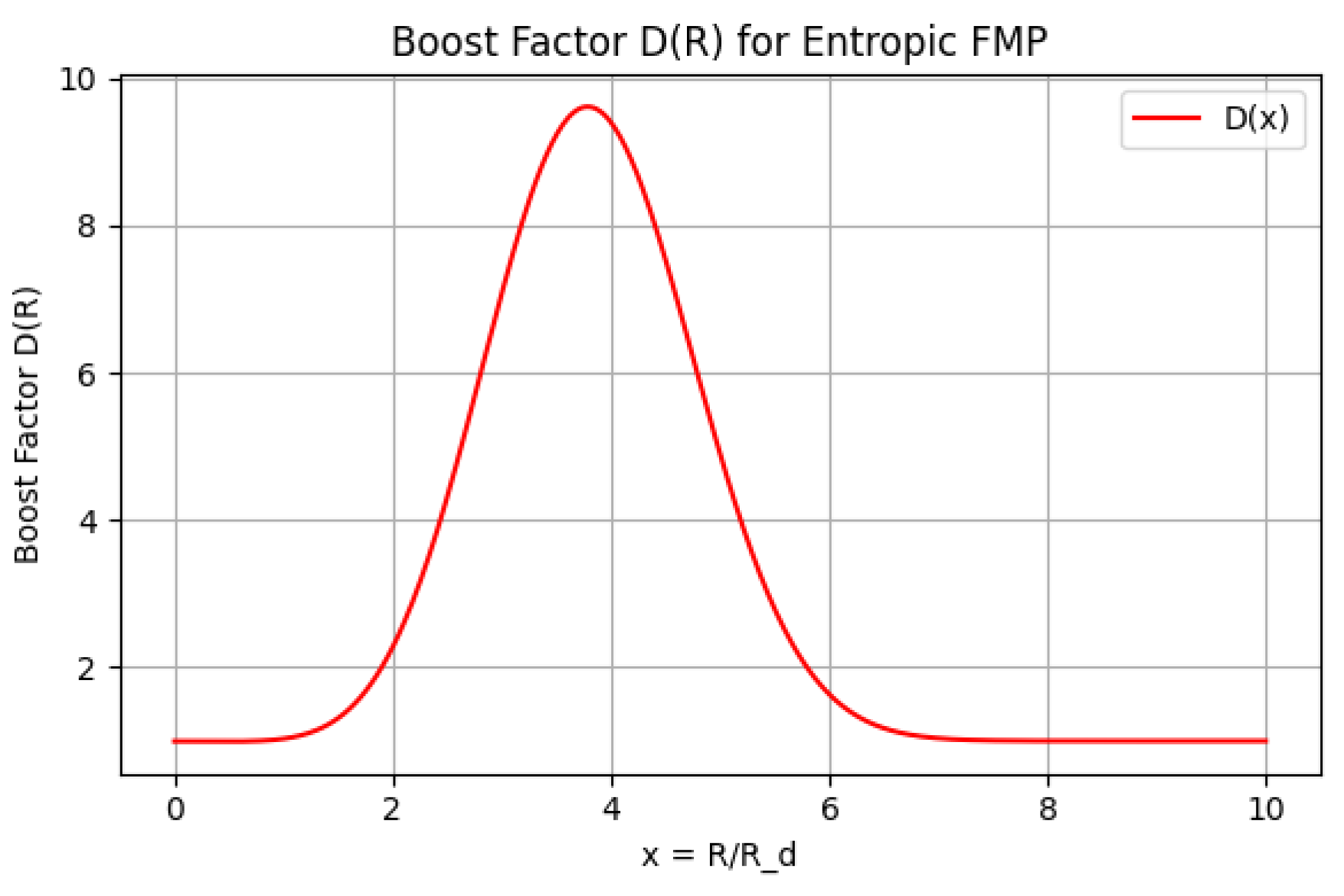

4.3. Entropic FMP Boost for the Milky Way

The entropic contribution to the FMP source for small fluctuations can be written as

It is convenient to define a dimensionless entropic boost factor

via

so that

corresponds to no entropic enhancement. In terms of

and

this yields

Using the exponential disc and Gaussian kernel model described above, the integral in (

34) can be evaluated numerically.

Figure 3 shows the resulting entropic boost factor

as a function of dimensionless radius

for our fiducial parameter set. The boost is close to unity in the inner disc, peaks around

and falls back towards

in the outer disc. For the Milky Way parameters quoted above we obtain

These values are in the range required by previous FMP fits to the Milky Way rotation curve and demonstrate that an entropic organisation of the kernel can reproduce phenomenologically viable boost factors while respecting the zero–DC condition.

5. Discussion

5.1. State Dependence of the Kernel

A central conceptual feature of the present construction is the explicit dependence of the entropic kernel

on the background disc

. This state dependence arises because the Hessian (

10) is evaluated at

and because the covariance kernel is modulated by the radial weight

. In contrast, the covariant FMP formulation assumes a configuration–independent bitensor kernel

on the CTP, whose Newtonian limit is expected to reduce to a kernel independent of the particular disc under consideration.

The present entropic kernel should therefore be interpreted as a surrogate that captures some qualitative features of the Newtonian limit of in a given state, rather than as a direct reduction of the covariant kernel. An important open question is how strongly changes as one varies across different galaxy types. A minimal test would be to repeat the analysis for a low–surface–brightness disc with larger and lower and compare the resulting dimensionless boost profiles . If remains approximately universal in scaled variables, the state dependence may be weak enough to be compatible with a more fundamental, configuration–independent kernel; if not, the entropic surrogate may have to be refined or supplemented.

5.2. Gaussianity and Higher–Order Corrections

The Gaussian closure adopted here neglects cubic and higher–order cumulants in the fluctuation statistics. A rough estimate of the leading correction can be obtained by comparing the cubic and quadratic terms in an expansion of

S around

. Denoting by

an effective skewness parameter and by

the variance of fluctuations, one expects schematically

For relative fluctuations

and moderate skewness

this suggests corrections at the

–level, which is acceptable for an exploratory framework. In strongly non–Gaussian, nonlinearly evolved gravitating systems one might have

–3 and larger relative fluctuations, in which case cubic corrections could reach

–50%. A more careful treatment of non–Gaussian statistics is therefore warranted once the present framework is confronted with high–precision data.

5.3. Connection to the CTP Horizon

In the covariant FMP framework the bitensor kernel

is defined on a CTP segment of finite duration

. Intuitively, the finite temporal horizon should translate into finite spatial correlation lengths in the Newtonian limit. A crude estimate can be obtained by considering typical radial excursions

of disc stars over the time

, with

and

a characteristic radial velocity. Identifying

suggests

For Milky Way parameters (

,

) and a correlation length

as used in this work, this relation points to a horizon

of order

yr, comparable to a few orbital timescales at the solar radius. A rigorous CTP–based derivation of

would be needed to confirm or refute this intuition.

6. Conclusions

We have constructed an exploratory “entropic” linear–response organisation of the Newtonian FMP kernel for axisymmetric galactic discs. Starting from a coarse–grained functional consisting of a local logarithmic term and a quadratic pair term in the fluctuations, we defined a background–dependent linear–response kernel as the Hessian of S around a chosen background disc. Restricting to Gaussian statistics and a simple radially modulated covariance kernel, we parametrised the entropic contribution to the FMP source as a superposition of local and nonlocal pieces controlled by a small fluctuation parameter and two effective amplitudes.

For an exponential Milky Way–like disc we showed how the radial zero–DC condition fixes the ratio of local to nonlocal amplitudes and used a fiducial set of parameters to compute the resulting entropic boost factor . The boost is of order unity, with in the inner disc, a peak near , and a decay towards at , compatible with previously required FMP boosts for the Milky Way. The construction is explicitly background–dependent and phenomenological and does not claim to derive the FMP kernel from microphysics. Instead it provides a structured surrogate that organises the kernel in terms of coarse–grained disc properties and highlights which aspects a future, fully covariant CTP calculation would need to reproduce.

Future work should address at least three directions. First, a derivation of the covariance kernel from the CTP formalism would clarify the relation between the temporal horizon and the spatial correlation lengths used here. Second, the state dependence of the entropic kernel should be quantified by comparing different galaxy types and assessing the universality of the resulting boost functions in scaled variables. Third, a more realistic treatment of non–Gaussian density statistics could reduce the uncertainty associated with the Gaussian closure and provide additional structure in the kernel beyond the minimal ansatz adopted here.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Data Availability Statement

No new observational or simulation data were generated in this study. All numerical examples are based on analytic model profiles described in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Portions of the initial drafting and language polishing of this manuscript were assisted by a large language model (ChatGPT, OpenAI). All physical assumptions, mathematical derivations, parameter choices, and the final text have been checked and approved by the author, who remains fully responsible for the content.

References

- T. Jacobson, Thermodynamics of spacetime: the Einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Verlinde, On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. JHEP 2011, 4, 29. [Google Scholar]

- M. Milgrom, A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophys. J. 1983, 270, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Sofue, Grand rotation curve and dark matter halo in the Milky Way Galaxy. Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan 2012, 64, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Lali,Future–Mass Projection gravity: divergence–free bilocal kernels and galactic rotation curves. Preprints, in preparation. 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).