1. Introduction

Flooding and marine submersion are now major governance issues for coastal areas, whose vulnerability is exacerbated by the effects of climate change (Magnan, 2009). This situation calls for more structured public action that can coherently combine the protection of populations, the preservation of aquatic environments, and risk anticipation. It is with this in mind that a major reform of water governance has been undertaken in France, as part of a drive to decentralize and streamline public action.

The 2014 Law on the Modernization of Local Public Action and the Affirmation of Metropolises (MAPTAM) thus conferred on public inter-municipal cooperation establishments (EPCI) the mandatory competence of GEMAPI (Management of Aquatic Environments and Flood Prevention), transferring responsibility for protection against water risks to the local level (Barone and Ghiotti, 2023). This reform was designed to provide more consistent and unified management at the watershed level, breaking with the fragmented institutional framework that had previously prevailed despite European directives, notably the Floods Directive (FDI) and the Water Framework Directive (2000 and 2007), and the numerous planning tools (SDAGE1, SAGE22, PGRI33, PPRI4, PAPI5) (Harle, 2015; Heitz et al., 2018).

In the Dunkirk area, this reorganisation was anticipated as early as 2016, two years before the national deadline. This initiative reflects an acute awareness of the vulnerability of the area: as a polder reclaimed from the sea, it depends on a complex and costly hydraulic system to ensure its safety. Located in the Aa delta, France's first inhabited polder, the Dunkirk region is based on a dense network of canals, watergangs and wateringues. The Intercommunal Institution of Wateringues plays a central role in organising the evacuation of water to the sea, in particular through ‘sea gates’ that operate in alternation with the tides (IIW, 2023). During periods of high water, this system is reinforced by electric pumps, which are essential but particularly costly in terms of investment, maintenance and energy consumption.

The intensification of extreme events, such as the episode in the winter of 2023-24 (Baraër, 2024) linked to climate change, makes it essential to strengthen and modernise these infrastructures. Alongside this hydraulic strategy, complementary solutions are being considered, such as increased water retention upstream through flood expansion areas. While these solutions help to limit pressure downstream, they also require heavy funding and raise issues of social acceptability in an intensively farmed agricultural area. The Dunkirk region must therefore combine local protection with regional solidarity, since its canals also drain part of the water from neighbouring areas during floods, as demonstrated by the events of 2023 (Barraqué, 2025).

The financing of these developments is based in part on the GEMAPI tax, introduced in 2016 in the Dunkirk region with a yield of three million euros, now increased to nearly 4.8 million, representing an average of around 24 euros per inhabitant per year. However, this average mask the reality of a growing budgetary effort: on the one hand, some households that are exempt from property tax do not contribute, and the same is true for tenants; on the other hand, elected officials vote for an overall amount intended to cover needs that are set to increase over time. In this context, the GEMAPI tax is an essential lever, but its amount is set to increase in the coming years due to the rise in extreme events (Heitz et al., 2018). The Dunkirk area thus illustrates a paradox: relatively spared by certain floods, it nevertheless bears a high cost to secure not only its own territory but also part of the Hauts-de-France region. This ‘buffer zone’ function further emphasises the need for sustained and lasting financial support.

Are the population really aware of these technical requirements and the vulnerability of the area? Is the GEMAPI tax perceived as legitimate? Would residents accept an increase in the future? Answering these questions requires a perception survey carried out in two phases, one qualitative through interviews and the other quantitative through a questionnaire.

This article takes a multidisciplinary approach combining sociology, anthropology and geography to analyse social representations and local governance. It first looks at the population's perception of risks and representations of the GEMAPI tax (I). It then analyses the issues related to territorial equity in the financing of GEMAPI (II). Finally, it considers the role of transparency and communication in legitimising residents' contributions (III), before reflecting on the conditions for greater social acceptability, territorial justice and institutional transparency.

1.1. How Should Social Representations be Taken Into Account in the Implementation of the GEMAPI Tax?

The implementation of the GEMAPI tax, introduced to finance the management of aquatic environments and flood prevention, raises both social and territorial issues. Behind its apparent fiscal technicality, this tax questions citizens' relationship to the collective management of water, risks and environments, in a context marked by socio-spatial inequalities and tensions around local governance.

Analysis of the tax cannot be limited to simply measuring residents' consent: it is necessary to study how they perceive it and how they receive it, i.e., how they understand, interpret and evaluate this policy.

To this end, we propose to analyse the GEMAPI tax through three theoretical axes that revolve around citizens' perceptions. First, we will examine the social representation of the tax. Then, we will address issues of justice and socio-spatial inequalities in the distribution of this tax. Finally, we will look at communication and the legitimacy of the measure, which are key conditions for citizen acceptance.

1.2. Social representation of the GEMAPI tax: a question of legitimacy

The GEMAPI tax faces challenges in terms of social representation and fiscal legitimacy. Rather than a mere financial instrument, it reveals how residents perceive and form opinions about local taxation. This tax social representation, i.e., the set of beliefs, values and ideas the population has about it, does not always coincide with the meaning given it by institutions.

According to Alexis Spire (2018), the feeling of ‘social unease’ about taxation does not stop at national taxes, but extends to local taxation. For some of the population, the GEMAPI tax may be perceived as ‘yet another tax’, a new addition to an already excessive tax burden, reinforcing the feeling that the tax system is unbalanced and unfair.

The legitimacy of a tax does not stem solely from individual cognitive mechanisms, but also from collective dynamics. Indeed, several studies highlight that perceptions of unfairness and the visibility of taxation significantly influence the acceptance of taxation. ‘The feeling of relative deprivation in the face of unfair tax policies, [...] as well as the high visibility of the tax system, are the main causes of the rejection of taxation observed in various Western democracies’ (Wilensky, 1976, cited by Adrien Fabre, 2020). Similarly, ‘high taxation levels and the increasing reorientation of public resources towards unpopular priorities […] will lead to massive tax revolts, fuelled by a sense of excessive tax burden and relative deprivation’ (O’Connor, 1973, cited by Adrien Fabre, 2020).

As Bazart (2001) has shown, “among the main factors that generate tax resistance and thus a loss of legitimacy, the unfairness of the tax system, a perception exacerbated by the opacity of tax legislation and the complexity of the tax structure, is often highlighted” and reinforces citizens' mistrust. Transparency, communication and the visible allocation of revenue thus appear to be necessary conditions for the acceptance of a local tax (Oh, 2024; Solen and Kallbekken, 2011; Baranzini and Carattini, 2017).

Beyond the informational dimension alone, Brunson's (1996) work shows that each taxpayer forms their own individual judgement, comparing the existing situation with possible alternatives. This representations plurality reveals a relationship with taxation by no means uniform.

From this perspective, the “fiscal malaise” described by Spire emerges locally, not as a rejection of the idea of solidarity, but as a rebuff of a fiscal policy perceived as unfair or ineffective, which corresponds to this theory's “social unacceptability”

It is, moreover, the absence of dialogue that can undermine this tax legitimacy. From a collective perspective, Caron-Malenfant and Conraud (2009) emphasise the role of deliberation and compromise between stakeholders in establishing the “minimum conditions for harmonious integration” of a project into its social and natural environment. However, in Dunkirk, the GEMAPI tax early implementation in 2016 was not accompanied by structured consultation or appropriate communication. The lack of dialogue between public actors and residents has limited the conditions for collective legitimisation of the levy, forcing citizens to form their own opinions of the measure in a context of limited public debate (Simard, 2024; Roger, 2021).

The analysis of this perceived legitimacy can be refined through three dimensions. In terms of distribution, residents assess fiscal justice (Bernard, 2010). In terms of procedure, legitimacy is based on transparency and the quality of citizen participation. Finally, in terms of substance, it refers to the expected effectiveness of the measure, i.e. its actual ability to reduce the area's vulnerability to flooding. In Dunkirk, the initial lack of information and consultation weakens the procedural dimension, while the substantive dimension remains to be confirmed.

Thus, social representations of the GEMAPI tax reveal its legitimacy is not a given, but an ongoing process. This depends on a combination of individual perceptions, collective recognition and tangible results on the ground.

1.3. Justice and Socio-Spatial Inequalities: The Question of Contributory Equity

The GEMAPI tax lies at the intersection of territorial solidarity and distributive justice (Rawls, 1971; Bret, 2009). The transfer of GEMAPI responsibility from central government to self-financed public establishments for inter-municipal cooperation (EPCI), although intended to bring management closer to grassroots level, has resulted in increased territorial inequalities. As recent literature has emphasised (Barone and Ghiotti, 2023), this decentralisation has created significant disparities between local authorities, as they do not all have the same financial capacity to bear this new burden. EPCIs with a solid tax base, thanks to a dense economic fabric or a high concentration of wealthy property owners, are better equipped to finance aquatic environment prevention and management works. Conversely, other more vulnerable territories are left with limited resources to deal with environmental risks.

Bret (2009), re-reading Rawls, points out that inequalities are only justified if they benefit the most vulnerable. The situation with the GEMAPI tax seems to contradict this principle. The contribution, which is mainly paid by businesses and landowners, is set to increase in a context of climate change where the risks of flooding and marine submersion are intensifying. Areas such as Dunkirk, which are already environmentally vulnerable and do not have a sufficient tax base, will be made even more vulnerable, widening the gap between ‘resilient’ communities and others (Fujiki and Finance, 2022).

Lack of inter-municipal pooling at watershed level exacerbates these inequalities and fuels controversy (Matias, 2024). Harvey (2009), in ‘Social Justice and the City’, points out that spatial justice is not limited to the equitable distribution of wealth, but also includes the distribution of burdens, benefits and risks. Consent to taxation therefore depends on its perceived fairness: residents may legitimately question whether the financial burden is distributed fairly between directly exposed coastal areas and more remote areas, or whether large companies, which are often major polluters, contribute proportionately to costs. We therefore consider the GEMAPI tax acceptability would only be consolidated if it were perceived as a solidarity-based project, beneficial to all residents and reinforcing the sense of territorial justice. This dimension is undermined by the inherent limitations of implementing this competence, which risk exacerbating territorial inequalities at the national level.

As Ytier (2024) points out, a densely populated EPCI can generate substantial GEMAPI revenue, perhaps even exceeding the costs actually necessary to implement the competence. On the other hand, a less populated territory that is highly exposed to water risks could receive insufficient revenue to cover its needs. The €40 per capita tax cap could limit the expected tax revenue, which could result in insufficient funding to cover the operating and investment costs associated with GEMAPI. This tension illustrates a structural difficulty because, despite the legal obligation to exercise this competence (since 2018), the current method of calculating the tax would not always enable vulnerable areas such as Dunkirk to have adequate resources to deal effectively with environmental challenges.

This disconnect between available resources and actual needs highlights the fact that the tax calculation method does not fairly reflect each territory’s specific characteristics, which tends to increase inequalities and fuel a sense of local injustice.

1.4. Communication and Legitimacy: From Information to Communicational Action

The introduction of the GEMAPI tax by the Urban Community of Dunkirk (CUD) raises issues regarding legitimacy and acceptability. Although it is linked to property tax to finance essential environmental and safety measures, there is still a significant lack of awareness among residents about its role and purpose. This information deficit is not only a technical shortcoming but also a democratic issue.

According to Dominique Wolton (1997), effective public communication is not limited to the top-down dissemination of information, but aims to create meaning and establish dialogue, thereby strengthening public action legitimacy. In the case of GEMAPI, lack of clear communication transforms an essential contribution into a mere additional tax cost, with no perceived benefit (Gilbert 1998). This situation can be explained by Crozier and Friedberg's sociology of organisations (1977). According to them, the ‘stakeholders’, in this case the Dunkirk authorities and residents, pursue divergent interests, which generates areas of uncertainty. An asymmetry of information is created when citizens do not perceive the need for the tax, thus preventing the establishment of a trust relationship. This communication deficit fuels a ‘power of non-acceptance’ among residents.

This deficit also corresponds to a weakness in ‘communicative action’, a central concept in Habermas (1981), taken up by Robichaud (2015), according to which the legitimacy of a policy cannot be built without a deliberative space where consensus is being shaped. However, the lack of transparency regarding the GEMAPI tax amount, use and purpose undermines this process, limiting citizen ownership. As Ulrich Beck (1986) points out in ‘The Risk Society’, threats are often invisible, created by modernity and perceived as distant. In Dunkirk, the absence of major floods since 1953 reinforces this diminished perception of risk.

For communication to be truly effective, it must be transparent, participatory and engaging. Lascoumes (2018) points out that institutional media coverage must be accompanied by local co-construction of decisions. This observation is in line with the analyses of Flanquart et al. (2017), which show that the perception of risk and the acceptability of measures are closely linked to the quality of institutional dialogue.

The Dunkirk area's geography and technical context are also key to understanding the communication challenges around the GEMAPI tax. The Dunkirk Urban Community is on polders, which are areas of land reclaimed from the sea that are below sea level. Keeping this area safe depends on a complex and historic network of ditches, canals, and pumping stations. This technical reality fits into the ‘modern water’ paradigm (Linton, 2013), which is a highly technical approach that values engineers' expertise over local experience.

However, this technical efficiency paradoxically constitutes an obstacle to understanding the tax: the fact that major flooding is prevented thanks to infrastructure makes the risk ‘invisible’ to residents (Flanquart et al., 2017).

Beyond the economic and technical dimensions, acceptability raises questions about social recognition. Dubois (2009) shows that every decision affects the value attributed to individuals and groups. Being kept out of the loop when it comes to information or decision-making, as is the case for many residents of Dunkirk with regard to the GEMAPI tax, amounts to being symbolically ‘devalued’.

This lack of recognition is part of a fundamentally asymmetrical social transformation (Barbier and Nadaï, 2015), where authorities impose an innovation without citizens being able to take ownership of it. This unilateral imposition creates a symbolic imbalance and fuels protest, illustrating a dynamic consistent with the issue of distributive justice. Mauss's (1954) work on ‘gift-giving’ and ‘counter-gift-giving’ sheds light on the contributory relationship: the payment of tax is a “gift” that calls for a visible ‘counter-gift’ in the form of tangible services.

For communication to be truly effective, it must be transparent, participatory and engaging. Bernard (2010) emphasises the importance of these dimensions. Lascoumes (2018) points out that institutional media coverage must be accompanied by local co-construction of decisions. This observation is consistent with the analyses of Flanquart et al. (2017): risk perception and the acceptability of measures are inextricably linked to the quality of institutional dialogue.

2. Materials and Methods

This article is based on the initial findings of an action research project conducted in the Dunkirk Urban Community (CUD) as part of the POPSU Transitions programme (Platform for Observation of Urban Projects and Strategies). Several tools and methods were used to collect data.

2.1. Presentation of the Case Study

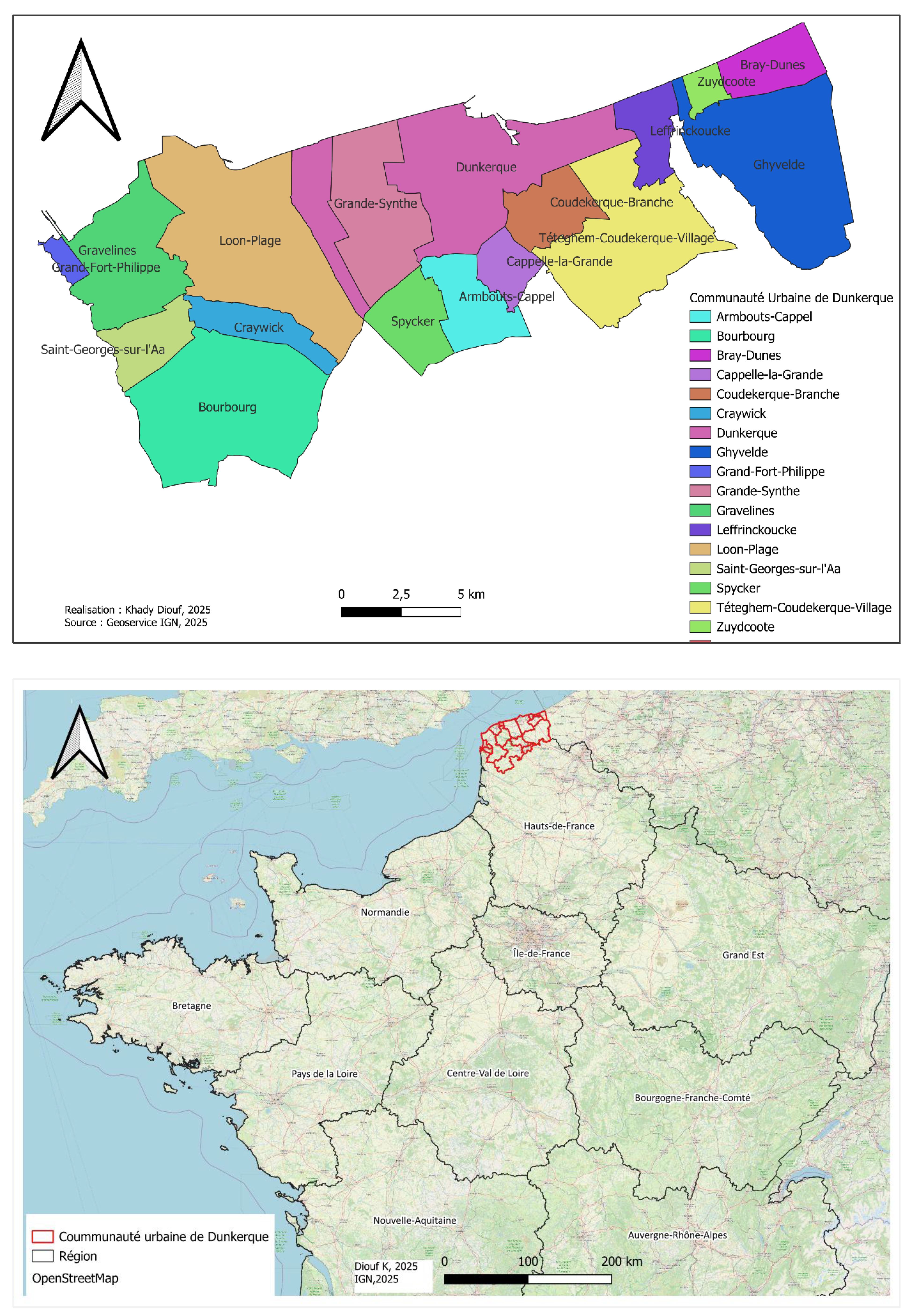

The Dunkirk Urban Community is located in the Nord department in the Hauts-de-France region. It is bordered by the North Sea, Pas-de-Calais to the west and Belgium to the east. It is located at the mouth of the Aa river and is a strategic location for draining water from Flanders into the sea.

The Dunkirk urban community comprises 17 municipalities with a population of approximately 193,000 in 2022, covering an area of nearly 300 km² (PLUIHD, 2023). The city of Dunkirk, the most populous, has a population of approximately 87,000 in 2025, with a high urban density. The area is socially and economically diverse, but also vulnerable due to high unemployment and an ageing population (INSEE 2025). Added to this is marked social diversity, with a poverty rate of around 19.4% and a median income per consumption unit of around £17,500. The unemployment rate remains high, at around 16.8% of the working population.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the Urban Community of Dunkirk.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the Urban Community of Dunkirk.

In terms of geography and climate, the CUD is marked by an oceanic climate, cool and humid, with approximately 700 mm of annual rainfall, average temperatures ranging from 5.5°C in January to 18.8°C in August, and sea temperatures varying between 7°C and 18°C depending on the season (PACET 2015-2021). The territory is part of a so-called ‘polderised’ landscape, consisting of land reclaimed from the sea, much of which is below sea level (PACET 2015-2021). The combination of these climatic characteristics and polders' low altitude increases the area's vulnerability to flooding, sea submersion and erosion, exacerbated by the effects of climate change. To address these constraints, Dunkirk relies on a set of technical developments that structure its spatial and economic organisation. The network of canals, locks and dykes regulates the flow of water between the hinterland and the sea, while pumping stations reinforce drainage capacity in the event of flooding. Major protective structures include the Alliés dyke and the 4 Écluses (

Figure 2).

The 4 Écluses is a strategic hydraulic crossroads, built mainly between 1930 and 1939 on the site of a former fortified bastion. It plays a crucial role in regulating the flow of fresh and salt water to protect the city, ensure navigation and channel water flows from the surrounding areas, including inland Flanders. The Alliés dyke, built in 1876, is another major structure. It plays a dual role: channelling continental floods towards a controlled drainage system (notably via the Tixier structure) and protecting the population from sea flooding. After suffering two serious breaches during the 1949 and 1953 storms, which caused major flooding in several neighbourhoods, the dyke has recently undergone reinforcement work. These include massive sand replenishment (1.5 million m³) in front of the dyke to mitigate the impact of the swell, as well as structural repairs to ensure the structure's resistance for more than 50 years, particularly in the event of a hundred-year storm (CUD, 2014).

Economically, the CUD remains a dynamic hub thanks to its large industrial port and its logistics, chemical, naval and commercial activities. Dunkirk is France's third largest port, specialising in bulk traffic (minerals, coal, cereals, containers). This port has fostered the development of heavy industry (steel, petrochemicals, power stations) and is now home to projects related to carbon-free energy (offshore wind power, hydrogen). More than 4,800 active establishments are listed there, with a majority in commerce, transport and services, but also a significant amount in industry (INSEE 2025).

At the same time, the region is seeking to diversify its economy with sectors such as logistics, the environment, research and seaside tourism around Malo-les-Bains. This economic fabric remains closely linked to water management, which protects port and urban areas. All infrastructure and governance, within the framework of GEMAPI (General Management of Public Waterways), ensures integrated risk and resource management, thus preserving the Dunkirk region's safety, resilience and development.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Several tools were used to collect data, including an interview guide, a questionnaire, as well as software and platforms for processing and storing information such as Sphinx and Google Drive. A mixed methodology was adopted, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. The sample studied comprised 130 residents, including 18 interview participants and 113 questionnaire respondents, selected to reflect a diversity of socio-economic profiles and residential situations.

Participants were recruited using a variety of approaches: in public spaces, particularly in the streets and libraries, but also through door-to-door canvassing. We also sought participants at public events organised in the CUD, such as Heritage Day, science workshops, Housing Day and at the Coudekerque-Branche wastewater treatment plant. On these occasions, participants were also interviewed as part of participatory observations. We also visited community centres to meet residents. In addition, we were able to count on the help of several community organisations, which facilitated our access to their facilities, allowing us to introduce ourselves to staff and the public.

The collection of qualitative data took place in two phases. An appointment was made with each participant according to their availability, followed by a semi-structured individual interview. These interviews, conducted in March and April 2025, took place mainly in the Dunkirk University Library and media libraries in reserved areas, ensuring optimal confidentiality. Other interviews were conducted at the TVES laboratory. In order to preserve data integrity, each exchange was digitally recorded after obtaining the participant's informed consent. Field notes were also taken simultaneously to capture non-verbal observations and contextual impressions.

Quantitative data was collected between June and August 2025 using a questionnaire consisting of 26 closed-ended questions (multiple choice and open-ended). The surveys were conducted in situ in locations such as Pôle Emploi, in front of Dunkirk Town Hall during the Gigapuces6 (Figure 3), in community centres such as the one in the Glacis district (Dunkirk), at the media libraries in Dunkirk centre and Malo-les-Bains, and on Place Jean Baert, notably with the Bustr'EAU initiative in collaboration with the SUEZ team, as well as during the Voiles des Légendes event in July 2025 at the water cycle management stand.

We also collected informal data through field observations, particularly during public events in which we participated. We took note of these verbal exchanges, which were often a kind of ‘venting’ for some, expressing frustrations or complaints, while others discussed their satisfaction, shared anecdotes, and for those who were not from the area, they shared examples from other places in France. This diversity of methods aimed to maximise the representativeness of the profiles encountered as well as the richness of the information gathered.

Figure 3.

Face-to-face administration of the questionnaire at Dunkirk Town Hall during the Gigapuces event (Field survey, Diouf, 2025.

Figure 3.

Face-to-face administration of the questionnaire at Dunkirk Town Hall during the Gigapuces event (Field survey, Diouf, 2025.

This was followed by the processing and analysis of the data. Qualitative data was collected through semi-structured interviews and analysed using Nvivo software, enabling thematic coding and detailed interpretation of the responses. Quantitative data, collected via a face-to-face questionnaire, was processed and analysed using Excel software to complement the qualitative analysis.

Here is one of the limitations of the field survey: it is restricted to residents and does not take into account the views of other stakeholders in the area. In addition, the data collection process encountered several difficulties. Many of those approached refused to respond, some were reluctant or did not have time, and others were not residents of the area. These constraints may have influenced the representativeness and richness of the information collected.

Box: GEMAPI COMPETENCE

At national level

The need for more consistent flood and marine submersion risks management led to a major reform in France, culminating in the 2014 law on the modernisation of local public action and the affirmation of metropolitan areas (MAPTAM).

• Creation of the competence: The MAPTAM law created the GEMAPI (Management of Aquatic Environments and Flood Prevention) competence, making it mandatory for public establishments for inter-municipal cooperation (EPCI) as of 1 January 2018. This measure aimed to unify water governance at watershed level, replacing a fragmented institutional framework. The GEMAPI competence is defined by Article L.211-7 of the Environment Code, which includes: "1° The development of a watershed or part of a watershed; 2° The maintenance and development of a watercourse, canal, lake or body of water, including access to that watercourse, canal, lake or body of water; [...] 5° Flood and sea defence; [...] 8° The protection and restoration of sites, aquatic ecosystems and wetlands, as well as riparian woodlands" (Environment Code, 2014a).

• Funding: To finance this competence, EPCIs may introduce a specific tax, also known as the GEMAPI tax. Its yield is capped at €40 per inhabitant. Tax authorities then distribute it among taxpayers: individuals or businesses subject to the business property tax (CFE), property taxes (built and unbuilt), the housing tax on second homes and, where applicable, on vacant dwellings. Although national revenues have increased significantly (from €150 million in 2018 to €455 million in 2023), they remain insufficient to cover all needs, creating regional disparities.

At local level: the case of Dunkirk

Dunkirk plays a strategic role at regional level, as the canals located in the area have served as an outlet for upstream waters, protecting other areas of the watershed. This ‘shield’ role increases the need for costly infrastructure, making funding through the GEMAPI tax all the more vital.

• Implementation of GEMAPI competence: The Dunkirk Urban Community (CUD) took over GEMAPI competence on 1 January 2016. Management of this competence is entrusted to the Intercommunal Institution of Wateringues (IIW), which maintains this vital hydraulic system.

• A dedicated financial instrument: The GEMAPI tax was introduced to finance the costly maintenance of the ancestral water management system. CUD elected representatives vote on a total amount based on estimated needs for the coming year, which is then passed on to property taxes. For 2025, the revenue is expected to be €4.8 million, which corresponds to an average of around €24 per inhabitant per year across the 17 municipalities. However, it is important to note this figure is a statistical average, as the tax is calculated per household and not based on an amount per inhabitant paying property tax.

• Funding for major operations is also supplemented by substantial subsidies from the State and the European Union, which can cover up to 80% of investment costs.

• A regional protection role: The recent floods of 2023-2024 highlighted

|

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. A Widespread Awareness of Risks and Conditional Acceptance of the GEMAPI tax

The GEMAPI tax, introduced to finance the management of aquatic environments and flood prevention, perfectly illustrates the tensions between collective necessity and individual perception. In the Dunkirk area, its acceptability appears conditional, as it is based on a vague awareness of the risks rather than fully informed support. While everyone recognises the existence of territorial vulnerability to water hazards, many are still unaware of the specific purpose of this tax, which is inconspicuously added to property tax. This lack of education breeds mistrust and heightens the feeling that it is an additional levy, especially as its benefits often remain invisible. Conversely, acceptance tends to increase when residents can make a concrete link between their contribution and tangible protection measures, which means that the effectiveness of this tax depends as much on institutional transparency as on the visibility of the developments carried out. This reflects the complexity of social perceptions and the tensions inherent in the territorial governance of essential and vulnerable resources (Tiberghien, 2008).

During our interviews, we found that those who are best informed or directly involved in water management understand its importance, as evidenced by this statement: “I am willing to accept an increase because I understand the importance of these watering networks” This acceptance of the tax is strongly linked to an awareness of the specific risks to which the Dunkirk area is exposed. Several residents point out that the area is “highly vulnerable to marine submersion”, but also to other threats, such as “pollution, with the weapons from the world war that were dumped in the water and which could sink and pollute the sea water” or the need to take ‘waterings’ into account. This exposure creates a constant dependence on the maintenance and upkeep of these structures to ensure the safety of the population and the preservation of economic activities. The GEMAPI tax therefore finances not only prevention and repair related to environmental impacts, but also the need to anticipate and protect the area against its structural natural risks (Ytier, 2024).

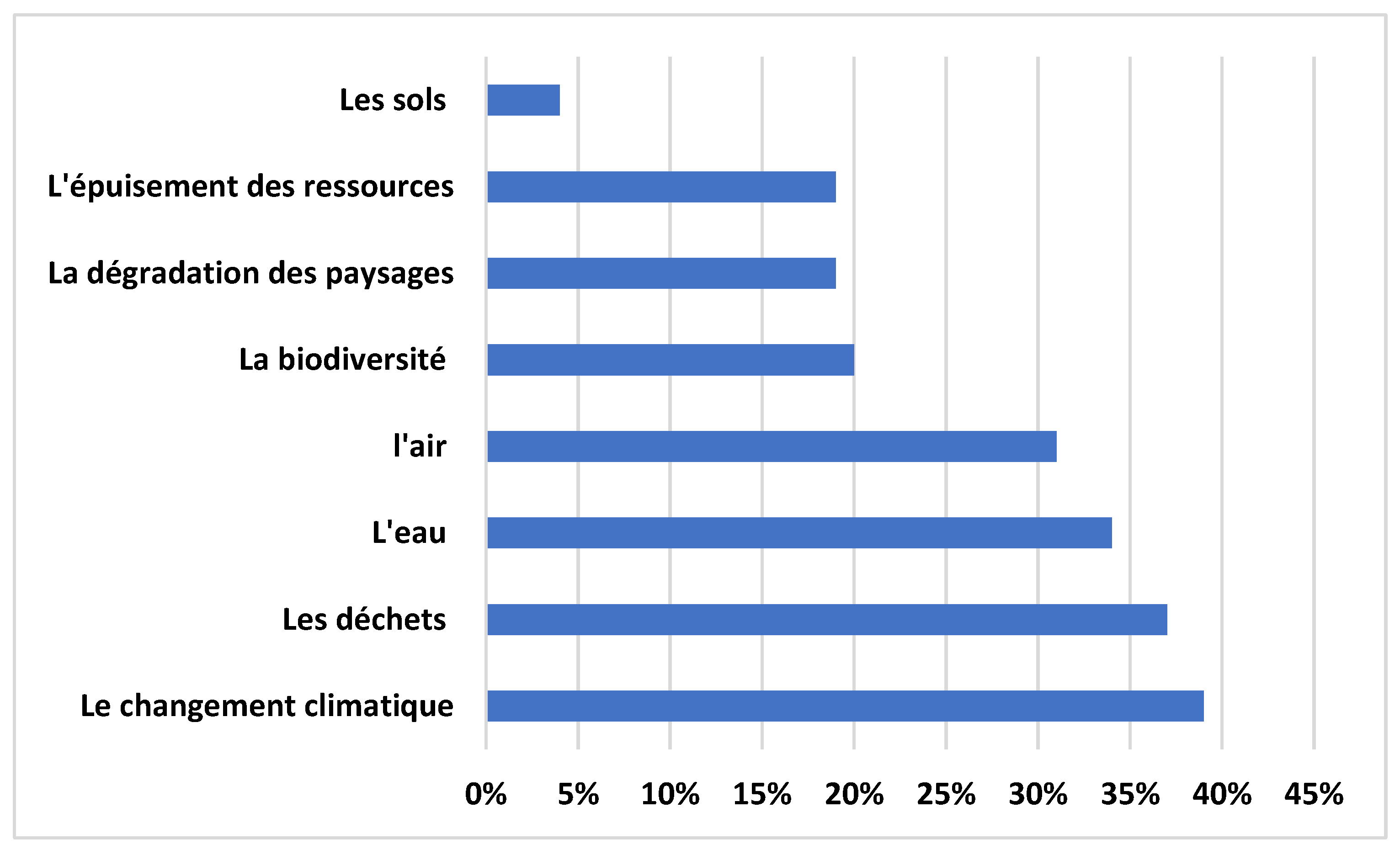

In addition to this sensitivity to the geographical context mentioned above, the results reveal that respondents are aware that the proximity of the sea makes the area potentially vulnerable: “We could soon be affected too, more so by these floods, because we are not far from the sea either.” This perception is confirmed by the results of the first question in the questionnaire, which allows us to rank the importance of water-related risks among the main environmental problems: climate change is the primary environmental concern (39.3%), followed by waste (37.5%) and water, with 33.9% of respondents mentioning it as one of their main concerns.

Figure 4.

Perceptions of the most pressing environmental issues (n=113) (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

Figure 4.

Perceptions of the most pressing environmental issues (n=113) (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

Some even make a direct link between climate change and increased risks: “Of course, if we do nothing, the water level will rise and we will be at risk of flooding”. In this context, the GEMAPI tax may seem like a reasonable investment, especially since the amount is considered affordable: “It's only natural because everyone can afford to pay £24 or £25 a year out of their own pocket; you don't really notice the cost”.

To illustrate this mutualisation logic, one respondent used a telling metaphor: “It's as if 20 people each give you one euro. That gives you €20 to solve your problem. But if you have to pay €20 yourself...” This comparison reflects an intuitive understanding of the principle of financial solidarity underlying the tax, while emphasising that the collective effort makes the individual cost more acceptable (Matias, 2024).

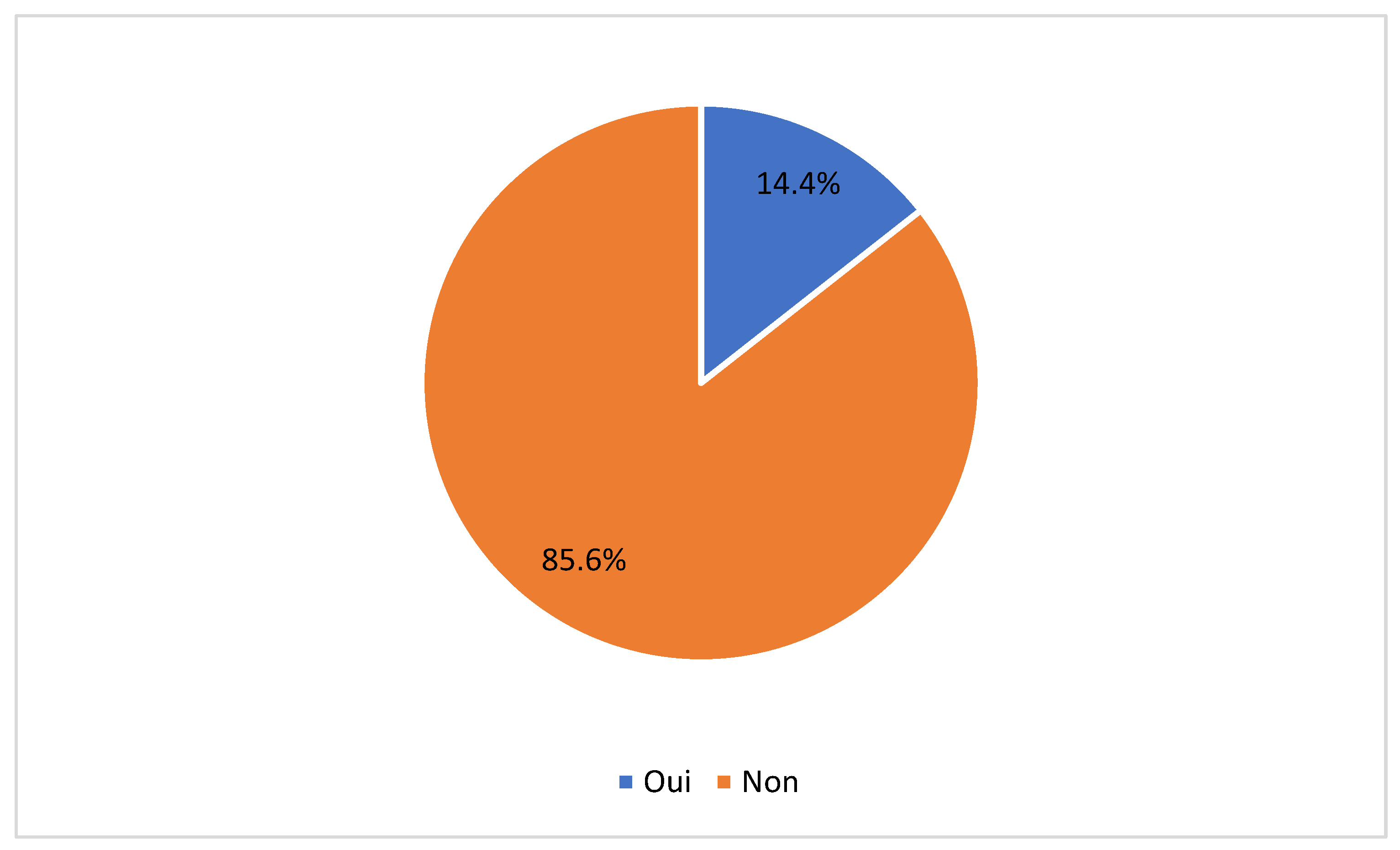

However, while some people clearly identify its link with flood prevention or dyke management, many (85%) are unaware of its existence or struggle to understand its practical uses. As one respondent put it : "I didn't know about this GEMAPI tax. I didn't know about it. And above all, I don't know what criteria are used to determine the amount of this tax. We don't know how it is calculated or why it is calculated in this way." The technical and regulatory complexity of this environmental tax makes it difficult for most citizens to understand. The survey shows that around 80% of respondents are unaware of how the tax works and what is at stake (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Awareness of the GEMAPI tax (n = 113) (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

Figure 5.

Awareness of the GEMAPI tax (n = 113) (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

This graph reveals a lack of awareness and a communication problem with regard to the GEMAPI tax. More than eight out of ten respondents say they have never heard of it. This lack of awareness was confirmed during interviews, through expressions such as: “Is it on the water bill?”, “How much is this tax?”, “Are we the ones paying this tax?”, or “Why is this tax being levied?”. This lack of transparency fuels doubt and resistance (Spire, 2018). Indeed, if a tax is added to property tax without providing a clear explanation of its purpose or amount, it is perceived as an unjustified additional tax burden. Lack of knowledge then turns into mistrust, as citizens feel they are being taxed without in any way understanding what they are getting in return.

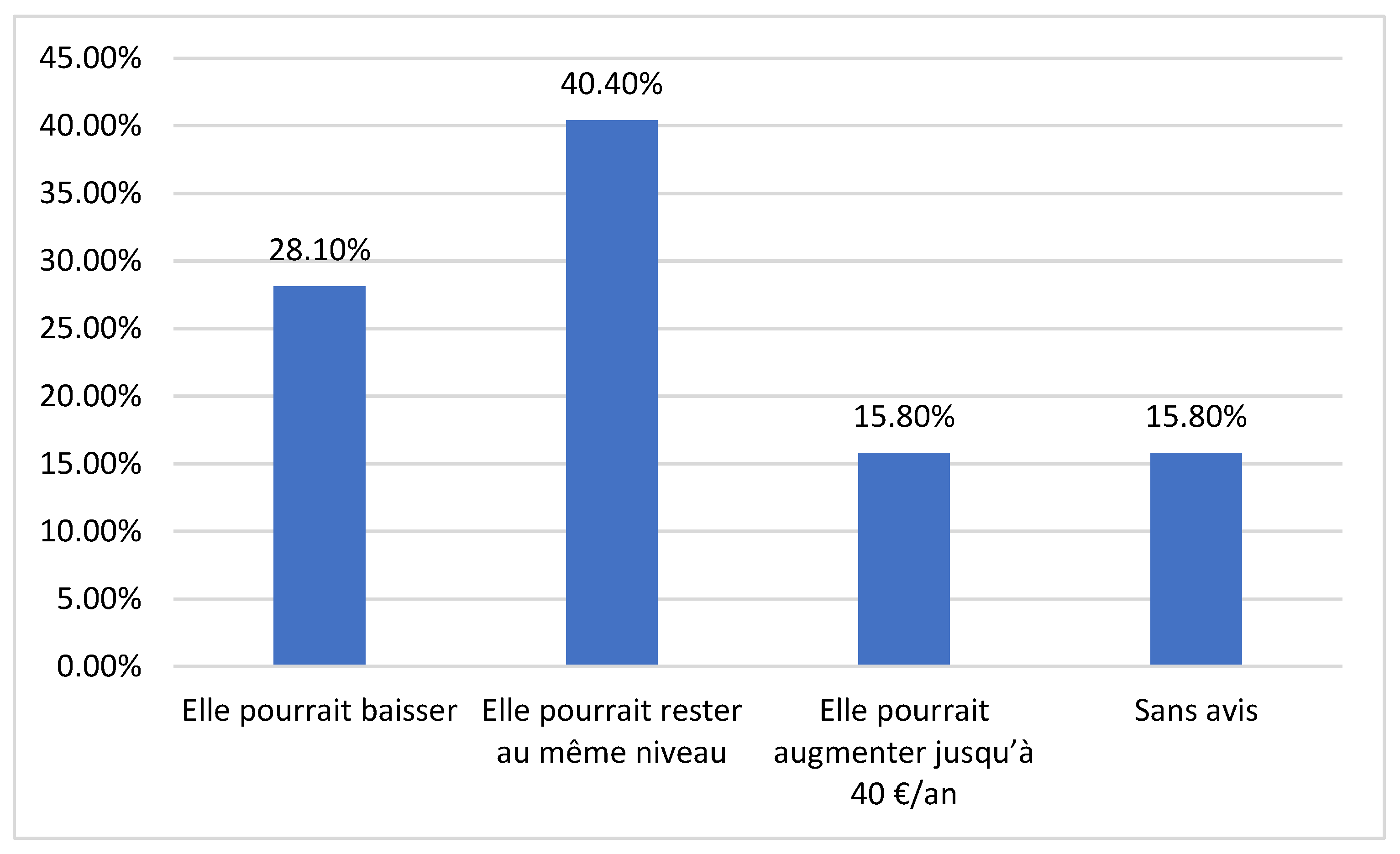

The problem goes beyond a simple lack of information. There is a disconnect between the tax's administrative rationale and taxpayers' perceptions. Authorities believe the tax finances essential services, but if these services are not made visible or if their link to the tax is not explained, citizens cannot make the connection (Heitz et al., 2018). This creates a sense of distance between political power and the population. The results of the quantitative survey (Figure 6) show the majority want to maintain the current amount, while a significant proportion would prefer to reduce it with few in favour of an increase.

Figure 6.

Local perceptions and expectations regarding changes to the GEMAPI tariff (n= 62)cart (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

Figure 6.

Local perceptions and expectations regarding changes to the GEMAPI tariff (n= 62)cart (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

The graph reveals mixed acceptance of the GEMAPI tax. The majority of respondents (40.4%) would like the GEMAPI tariff to remain at the same level, reflecting a preference for fiscal stability in a context where the tax is already perceived as significant. A significant proportion (28.1%) are in favour of a reduction in the tariff, reflecting concerns about purchasing power or the perceived tax burden. On the other hand, a minority (15.8%) accept an increase in the rate up to the regulatory ceiling of €40 per year, showing a degree of recognition of the financial needs associated with water environment management and risk prevention. Finally, 15.8% of respondents say they have no opinion, indicating a possible lack of knowledge or reservations about this specific tax.

This fragile and conditional acceptance of the GEMAPI tax emerged in the quantitative surveys, with several of our respondents insisting on the need to justify any increase: “If the increase is explained, argued and justified, we can understand it, but increasing it without saying anything is always a burden.” ”If the increase remains reasonable. Of course, if it is multiplied by three or four... but if it is reasonable, then yes.” These comments remind us that transparency and education are essential to maintaining trust and avoiding rejection of the scheme. Analyses by the French Council on Compulsory Levies (2019) confirm that clear objectives and transparent uses are key to gaining acceptance for environmental taxation. Without precise explanations or visible evidence of the actions being financed, the GEMAPI tax risks being perceived as an additional constraint rather than a genuine collective investment in the safety and preservation of the territory. Education is therefore not simply an option, but an essential element in transforming a simple tax burden into a shared investment in the safety and resilience of the territory.

3.2. Public Perception, Inequalities and Territorial Justice in the Financing of GEMAPI

The decentralisation of GEMAPI competence aims to bring flood risk management closer to the territory and its citizens. However, its implementation raises important questions of territorial justice and social equity. Variations in the adoption of the tax, differences in contributions between municipalities and the fact that only a few actors directly finance water protection fuel a sense of injustice.

Although the GEMAPI tax was introduced around ten years ago at the inter-municipal level, it remains largely unknown to residents. This lack of information leads to a perceived lack of transparency regarding its objectives, how it works and the use of the funds collected, giving rise to mistrust and questions about local water governance (Ostrom, 1990). Several aspects of GEMAPI's remit are not understood by citizens: the transfer of responsibilities to local authorities, the differences in contributions between territories and the fact that only property owners and selected businesses are direct contributors.

Analysis of the interviews reveals a marked distrust of the transfer of flood risk management from the State to local authorities. This measure is perceived by some respondents as “a way of shrugging off a national problem”, highlighting the State’s disengagement from an issue that should remain a collective and solidarity-based concern. There is also dissatisfaction with the idea of a breach of territorial equality, “because the fact that it was managed by the State allowed for equality between territories. It must remain a political and democratic issue.” Local management, although intended to bring decision-making closer to citizens, crystallises fears about fairness and national solidarity. In other words, it casts doubt on the ability of local authorities to independently implement prevention policies that are commensurate with the challenges. As Milot et al. (2015) point out, national policies always result in local adjustments. While decentralisation promotes local management, in the absence of robust equalisation mechanisms, it can worsen disparities and hinder equity.

The budgetary consequences of tax reform and the scarcity of local resources are fuelling the unease. Some respondents linked the abolition of the housing tax to the decline in local authorities' resources: “They have fewer and fewer resources with the end of the housing tax, for example. There is less money for local authorities. As a result, the burden once again falls on property owners. They have increased property tax”. This perception is in line with the evolution of the average GEMAPI tax revenue, which rose from €6.9 per inhabitant in 2017 to €7.5 in 2021, and now stands at €24 in the Dunkirk area, with prospects for an increase close to the national legal ceiling of €40.

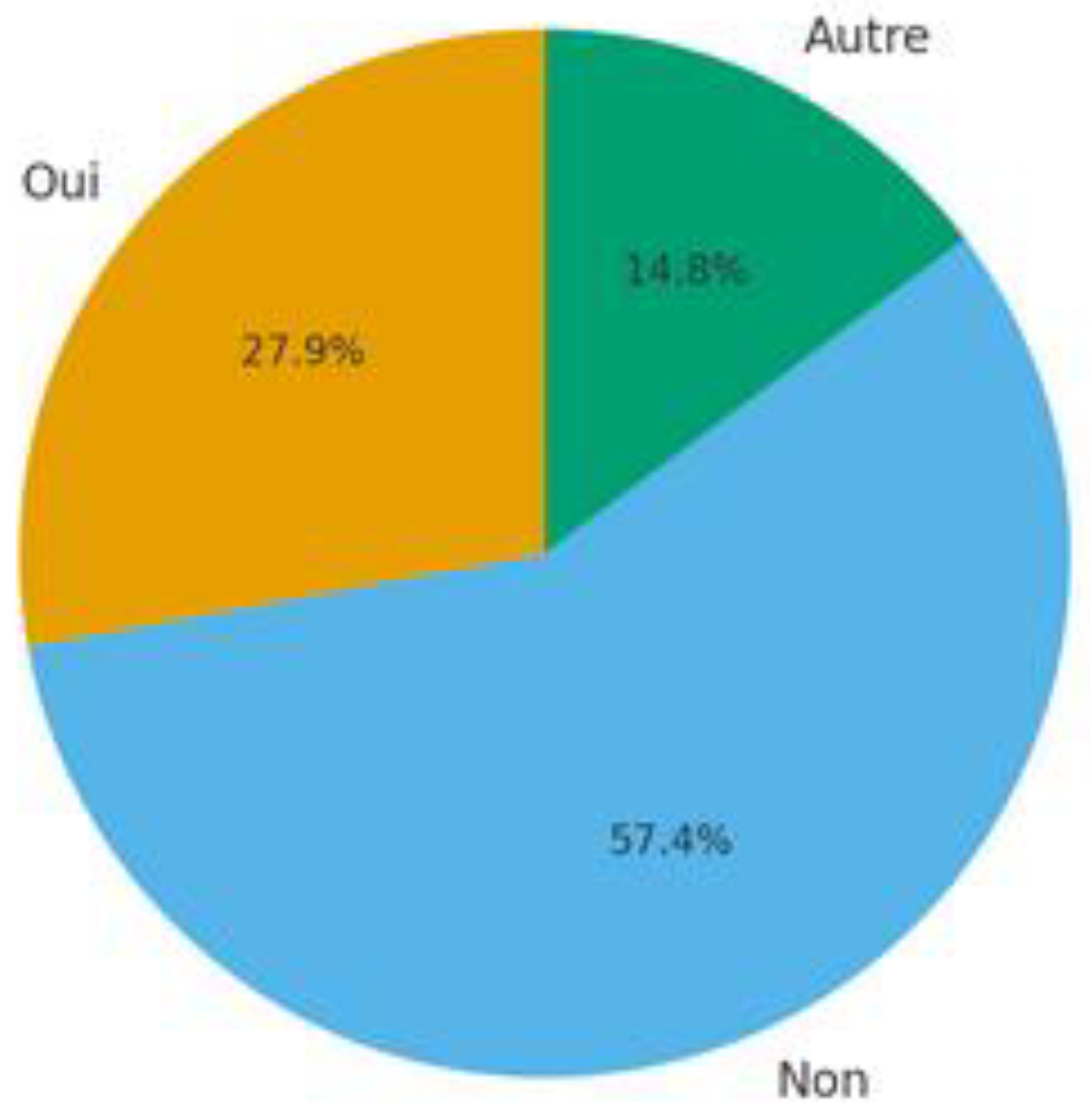

The results of the questionnaire show that a majority of respondents are opposed to the tax increase. More than half (57.4%) are against it, while 27.9% are in favour. The presence of an ‘Other’ category (14.8%), made up of people without an explicit opinion, highlights a significant degree of indecision or reservation on the issue (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Perception of the increase in the GEMAPI Tax (n=62) (Field Survey, Diouf, 2025).

Figure 7.

Perception of the increase in the GEMAPI Tax (n=62) (Field Survey, Diouf, 2025).

The issue of how the GEMAPI tax is distributed and assessed generates a sense of injustice among most respondents: “Why does it only affect property owners? I think it should affect everyone.” Several people emphasize the absurdity of linking flood protection solely to property ownership, while vulnerability affects all residents: “I think it should be paid by everyone, because if you live in public housing and there’s flooding, you suffer the consequences too. It’s not just the owners.” These remarks are especially relevant given that water-related risks, such as flooding, concern all inhabitants, whether owners or tenants. This imbalance is perceived as contrary to the principle of environmental justice, which aims to ensure fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, regardless of socio-economic status (Walker, 2012).

Furthermore, criticism also targets inequalities in contributions between municipalities. In the Aa delta, discrepancies in amounts collected between neighboring areas raise questions about territorial equity. Some northern coastal zones, like Greater Calais, which are more vulnerable to marine submersion, reportedly pay less than inland municipalities. One respondent, a property owner in Calais but resident in Dunkirk, stated he pays between 15 and 16 euros in Calais, while the average tax in Dunkirk is around 24 euros, revealing unequal contributions between areas with different levels of vulnerability. Some residents noted during interviews that neighboring municipalities seemed more exposed to water-related risks than Dunkirk itself. As one resident of central Dunkirk said: “I’ve lived here for 15 years and never had any flooding issues,” thus questioning the relevance of her financial contribution. This perception aligns with local reality, as the last major floods in the city date back to 1953.

However, a strictly local reading of vulnerability to hydrological hazards overlooks the interdependent nature of the territory. The Aa delta watershed is a complex system, where each water event causes cascading effects between municipalities. One significant testimony illustrates this interdependence: “Last year, near Saint-Omer, there were severe floods. The Bourbourg canal, which comes directly from Saint-Omer, crosses our territory, and during the floods, the pumps in Calais had to be opened to relieve pressure.” This highlights the interconnectedness of hydraulic infrastructure and the importance of coordinated risk management. This hydrological reality would justify a contribution model based on an integrated watershed vision, recognizing that a municipality’s safety depends on actions taken both upstream and downstream in the network.

Nevertheless, the findings highlight the need to strengthen communication, transparency, and explanation of distribution choices to build strong social legitimacy for the GEMAPI tax and ensure local governance capable of addressing Dunkirk’s water-related challenges.

3.3. The Fiscal Legitimacy of the GEMAPI Tax: Transparency and Environmental Justice

The social acceptability of a tax does not depend solely on its amount, but also on how it is perceived and understood by the population (Gendron, 2014; Conseil des prélèvements obligatoires, 2019). This acceptability is conditioned by transparency in fund allocation and clarity in how the tax burden is distributed among different stakeholders, based on their respective contributions to pollution. This requires clear communication about the criteria used to calculate the GEMAPI tax and how it accounts for the diversity of actors residents, farmers, and industrial companies with varying economic levels and environmental impacts.

This lack of transparency also raises questions about the tax’s actual effectiveness. Field observations, such as the silting of the wateringues (drainage channels), fuel the idea that the tax is collected without any visible action in return. One respondent noted: “I think that’s the main problem in France: we pay for things without knowing what they’re for, without seeing any results. It would probably be better accepted if there were better explanations about why the spending, the taxes, etc., and also some feedback to show what benefits it brings.” This sentiment echoes Stoker’s (1998) analysis of citizen distrust toward governance perceived as ineffective.

According to Gilbert (1998), the complexity of French local taxation lies in “the layering of taxes needed to exercise local powers, sometimes generating overlaps and redundancies.” Local taxation must therefore balance competencies, transparency, and fairness. “A good local tax must balance competencies, be based on sources that are both localizable and stable, and allow communities to differentiate themselves. It must also ensure a fair distribution of burdens, which is fundamental to guaranteeing the social acceptability of local levies.” (Gilbert, 1998).

Despite the organization of citizen meetings, one participant pointed out that concrete information about the tax’s actions and role is nonexistent: “There were small citizen meetings about the marine submersion issue, but really, it was just information, and nothing came out of it. There’s no information about it.”

This lack of transparency also raises questions about the tax’s real effectiveness. As one respondent emphasized: “There’s a noticeable level of neglect, if not general negligence. When you let silt and wild weeds accumulate, it takes up the space that water could occupy during excess rainfall.” This testimony, based on tangible field observations, reinforces the idea that the tax is collected without any visible action in return.

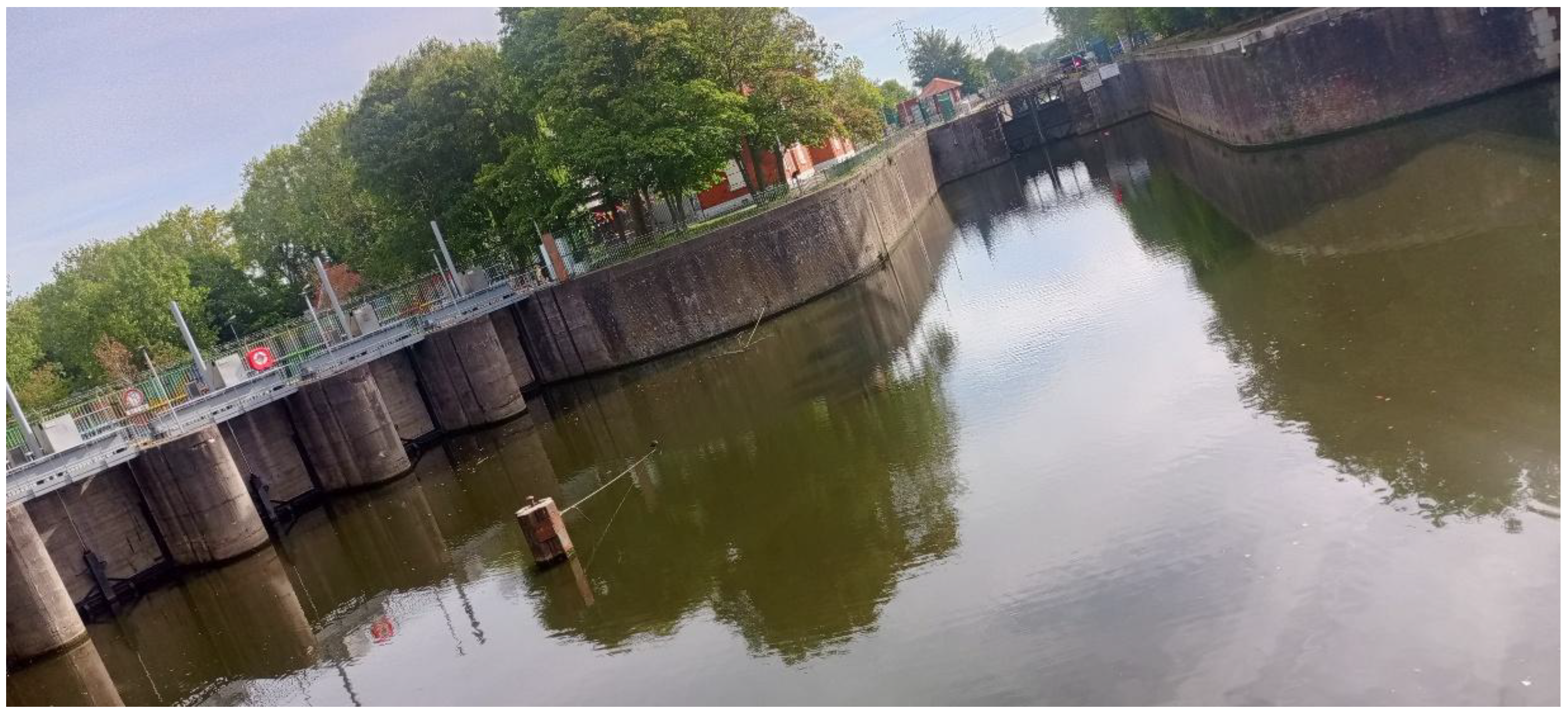

One participant went further, criticizing what she saw as inadequate measures given the scale of the risks: “They built tiny little walls in some parts of the beach against marine submersion, as if the sea would stop where the walls end.” (Figure 8). The Alliés dike has experienced major breaches in 1949 and 1953, causing significant flooding, which underscores the territory’s ongoing vulnerability to rising waters and the critical need for effective management tools like the GEMAPI tax (CUD, 2014).

Some authors argue that dikes are no longer an adequate solution, as they can, in the event of flooding, worsen damage rather than prevent it. Guerrin, Bouleau, and Grelot (2014) also point out that their structural integrity is weakened by climate change, which may alter the flood regimes they were originally designed to address. Another participant added: “It’s something that, in the end, we only see during crisis periods. We don’t see the fate of this tax in everyday life.” For this person, outside of exceptional situations (such as flooding or marine submersion…), the use of collected funds and the actions taken remain largely invisible. Moreover, since floods are rare in Dunkirk, the GEMAPI tax may seem unjustified to the local population.

Yet its usefulness goes beyond risk prevention; it ensures a secure and sustainable living environment for the territory. A polder, located below sea level, requires constant hydraulic management, including pumping and maintenance of the wateringue network. Additionally, Dunkirk, being highly industrialized and artificialized, has limited surface areas available to discharge or retain excess water during floods.

Figure 8.

Allies dike near the Texier pumping station (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

Figure 8.

Allies dike near the Texier pumping station (Field survey, Diouf, 2025).

The survey also reveals a deep-seated perception of fiscal injustice. Although industrialists and farmers contribute financially, this contribution remains largely invisible to the general public. Residents, already burdened by the tax burden, are particularly aware of the share they pay personally, which fuels a sense of unfairness. As one of them sums up: "They should pay in proportion to the pollution they generate. I would very much like to know how much Arcelor pays, for example. We need to know, citizens need to know how much polluting companies pay. ArcelorMittal is a highly polluting company. [...] In actuality, we do not know, it is completely opaque."

These comments reflect a demand for more rigorous implementation of the ‘polluter pays’ principle, a pillar of environmental policy. The lack of information on companies' contributions reinforces the perception that the tax burden falls primarily on households. One participant expressed this expectation of proportionality: "They pay €5,000 for this tax, but €5,000 means nothing. We need to know what percentage this represents in relation to the company's profits and income”. These comments reflect an explicit demand for transparency and proportionality, which is considered necessary to ensure the perceived fairness of the tax system. “[...] This tax should be calculated on the basis of the companies and the pollution they generate.” This demand for transparency is in line with the analyses of Badouard et al. (2016) on the need to make the contribution of the various actors visible and understandable in order to strengthen trust and acceptance.

Yet another respondent finds this distribution all the more unacceptable given that they already claim to adopt virtuous behaviour: "I'm one of those people who are really careful, I only travel by bicycle, I only use my car for long journeys. [...] In a way, it seems unfair to have to pay a tax on this when I'm making such a huge effort”. This feeling calls into question the ability of tax policies to integrate the sobriety of individual practices, echoing the work of Thaler and Sunstein (2008) on incentive policies.

It is important to remember that the GEMAPI tax is specifically intended to finance protection against the risks of flooding and marine submersion, the frequency and intensity of which are accentuated by climate change itself, aggravated by anthropogenic pollution, particularly industrial pollution. Thus, in the minds of many residents, the contribution of high-emission actors should be proportional to their impact on these phenomena. This desire for fairness reflects a deep commitment to environmental justice, especially since some believe that companies enjoy a form of impunity under the pretext of their economic role: “We say to ourselves, yes, but ArcelorMittal employs hundreds of thousands of people, so we mustn't mess with them. I say there's a problem there” Furthermore, among the economic players, there are also farmers, who are both heavy water users and potential polluters. It is interesting to note that respondents do not mention them spontaneously, and that when it comes to Dunkirk, residents automatically think of industry, even though the latter are making efforts to reduce their environmental impact, such as recycling, reusing treated wastewater, and other pollution reduction measures.

The GEMAPI tax is based on a logic of territorial solidarity (Matias, 2024). However, for this tool to be fully legitimate, it must be understood and accepted. This can be achieved by involving residents through information and discussion meetings, which would help to dispel doubts and provide details on the measures already implemented and future projects to come or the state of the hydraulic infrastructure. One participant expressed this need: "But the waterings are very old. Are the waterings being put into working order? I don't know. It would be interesting to have another citizens' meeting to discuss the situation." In a context where the effects of climate change are increasing the frequency of extreme events, it is essential that local authorities provide transparent details of the objectives, stages and results of the actions undertaken. This sharing of information, far from being a mere formal exercise, would allow for full public involvement in understanding the issues and encourage broader support for the policies implemented.

3.4. Discussion: Social acceptability, justice and fiscal governance of GEMAPI

The Dunkirk area, a highly artificial and heavily industrialized territory, faces cumulative risks of flooding, marine submersion, pollution, and network saturation, making the implementation of GEMAPI particularly essential for its protection and resilience. Yet, the dynamics of the hydro-social cycle that is, the entanglement of physical water-related processes and the social relationships that determine its uses remain poorly understood by a large portion of the population (Budds and Linton, 2014; Swyngedouw, 2009).

Our findings show that the opacity and lack of communication surrounding the GEMAPI tax fuel a clear “tax fatigue” and a strong sense of injustice among Dunkirk residents. The legitimacy of public levies depends primarily on transparent institutional education and clear communication about the use of funds. In this context, the GEMAPI tax, although based on a widely accepted theoretical principle the polluter-pays principle generates significant distrust. Citizens question its actual effectiveness and perceived fairness, particularly due to the lack of transparency regarding the contributions of large industrial companies such as ArcelorMittal. According to David (2003), “pollution is largely emitted by oligopolistic sectors such as the chemical and pulp industries.”

This fracture in environmental governance, where some economic actors appear less financially committed than individual citizens, creates a sense of injustice that undermines territorial solidarity (Harle, 2015).

Spire (2018) had already noted that any tax perceived as exorbitant or disproportionate could justify public resistance. Without going to such extremes, this reflection sheds light on the current situation: the GEMAPI tax, seen as vague and unfair, is likely to fuel similar distrust. The demand for transparency expressed by residents echoes Habermas’s (1987), work on democratic legitimacy. This lack of public communication may stem from a local political choice, especially since the GEMAPI tax is collected rather discreetly, embedded within the property tax, making it difficult for the general public to identify. Yet, as Gilbert (1998) argues, fiscal transparency is essential to strengthen taxpayer trust.

Beyond fiscal concerns alone, the social acceptability of the tax must be understood through a multidimensional framework. Wüstenhagen et al. (2007), as cited by Dermont et al. (2017), propose analyzing acceptability through three complementary dimensions: sociopolitical, community-based, and market-based. This framework helps explain the diversity of perceptions and objections observed in our survey. On one hand, some residents demonstrate resilience in the face of water-related risks and express a sincere willingness to contribute to the collective management of flood and marine submersion risks. On the other hand, a significant portion of citizens question the clarity and fairness of the effort required, which negatively affects the sociopolitical dimension of acceptability. These tensions are rooted in fundamental questions of environmental justice, as highlighted by Schlosberg (2007). This concept encompasses both distributive justice, which asks “who pays what?”, and procedural or participatory justice, which asks “who decides?”. Residents notably point to the disproportionate contribution of individual property owners, even though flood risk is collectively shared (Milot et al., 2015). Likewise, they question the actual involvement of major economic actors, whose impact is often significant but whose contribution remains unclear. These concerns align with recent findings by Diouf et al. (2024), which show that environmental inequalities are often exacerbated by a lack of transparency in the distribution of responsibilities and efforts.

Moreover, our study highlights a major contradiction between individual and collective effort, which fuels considerable frustration. Residents, despite adopting virtuous behaviors (such as sobriety and reduced consumption), feel penalized by a fiscal policy they perceive as uniformly applied, without recognition or reward for eco-responsible practices. This problematic dynamic raises fundamental questions about the role of fiscal policies: should they be limited to fund collection, or can they also serve as a lever for social recognition?

From a governance perspective, the GEMAPI tax embodies the typical challenges associated with managing common goods, as described by Buchs et al. (2020). The pooling of costs, a principle underlying this environmental taxation, relies on fragile financial solidarity. Such solidarity can only be sustainable if the effort required is clearly justified and if fairness in contribution is ensured both in the distribution among users and in the involvement of various economic actors (Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2017). However, the weak perceived link between residents’ contributions and tangible results on the ground undermines this solidarity. Testimonies about degraded infrastructure (“silted up,” “tiny little walls”) illustrate a lack of accountability that erodes trust. This observation echoes Stoker’s (2011) reflections on the need for transparent governance that demonstrates its effectiveness in order to strengthen legitimacy and citizen trust.

Territorial governance, in particular, appears highly complex. Cooperation between hydrologically interdependent intermunicipalities especially in the Aa delta represents a major challenge, hindering the implementation of coherent and integrated watershed-scale management (Torre, 2020; Ghiotti, 2006). As Tiberghien (2008) points out, territories with inherent hazards require governance strategies tailored to their specific vulnerabilities, promoting collective resilience and coordination among stakeholders. This situation is part of a broader context of increasing responsibility for local authorities, coinciding with the gradual withdrawal of the central state (Ghiotti and Marc, 2014). This shift generates significant disparities between territories, exacerbated by inequalities in available technical and human resources, and places a heavy burden on the ability of local actors to establish environmental taxation that is both fair, effective, and perceived as legitimate.

Managing GEMAPI in Dunkirk involves substantial expenditures for flood prevention and dike maintenance. Furthermore, as Ytier (2024) notes, Article 1530 bis of the General Tax Code sets the amount of the GEMAPI tax based on the number of inhabitants, even though these expenses depend primarily on geographical and natural characteristics. This disconnect poses a constraint for the local authority, as the tax calculation is not proportional to actual needs. Territorial justice in flood risk management depends on the ability to adapt national policies to local specificities (Milot et al., 2015). Ensuring a fair distribution of contributions among municipalities and inter-municipalities is therefore essential to guarantee equitable water protection for all.

It is essential to clarify that the GEMAPI tax can only be fully perceived as an instrument of territorial solidarity if its objectives, mechanisms, and impacts are made visible and understandable to all. Without accountability and recognition of citizens’ efforts, it risks remaining a contested levy, revealing tensions between environmental taxation, social justice, and trust in public action (Walker, 2012).

In this regard, the reflection by Guerrin, Bouleau, and Grelot (2014) on the “politics of scale” offers valuable insight into the case of Dunkirk. It highlights that water governance is not limited to technical or regulatory choices but also involves the articulation between local, intermunicipal, and national scales. This approach complements the analyses of Frère et al. (2012) and Milot et al. (2015), emphasizing that the legitimacy of water policies depends on the ability to combine public action, institutional legacies, and citizen involvement.