1. Introduction

Bangladesh is a land-scarce and densely populated country where forests play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance and supporting rural livelihoods. Forests provide timber, fuelwood, fodder, and a wide range of non-timber products while also ensuring environmental services such as biodiversity conservation, watershed protection, and carbon sequestration [

1,

2]. However, forest resources have drastically declined due to rapid population growth, agricultural expansion, and overexploitation, leaving Bangladesh with one of the lowest per capita forestlands in the world (approximately 0.02 ha/person) [

3]. According to the Forestry Master Plan, only about 6% of the country's land area is under tree cover, which is far below the internationally recommended 25% threshold [

4]. As a result of this degradation, it becomes a challenge to meet the growing demand for forest products while safeguarding ecological stability.

In response to these challenges, social forestry emerged in the early 1980s as a participatory forest management strategy aimed at ensuring sustainable resource use and improving rural livelihoods [

5,

6]. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) defines social forestry as forestry activities planned “by the people and for the people,” where communities participate actively in tree planting, management, and benefit sharing. Social forestry practices have been promoted in Bangladesh to achieve the dual objectives of resource conservation and poverty alleviation. Examples of these practices include strip plantations along roads and embankments, woodlot plantations on degraded forestlands, and agroforestry on marginal and homestead lands. Among them, homestead forestry or homestead agroforestry is a low-cost, high-return system practiced on approximately 25.49 million homesteads covering 0.80 million hectares, which significantly contributes to food security, income generation, biodiversity conservation, and rural development in Bangladesh [

7]. In order to encourage community involvement, the Social Forestry Rules (2004) institutionalized a benefit-sharing mechanism that ensures that beneficiaries receive a significant portion of economic returns from harvested plantations. In 2004, a new approach named 'Protected Area (PA) Co-management' was introduced in Bangladesh for conserving and protecting the biological diversity of forests against man-made disturbances [

8]. The main objective of this approach is the involvement of local stakeholders in forest management with the Forest Department, while ensuring alternative livelihoods through income-generating activities without degrading forests [

9,

10].

Kamalganj Upazila of Moulvibazar District, located under the Sylhet Division, represents a significant example where social forestry practices and co-management approaches have been implemented. Strip plantations, woodlot plantations, and collaborative forest management systems have created opportunities for local communities to access resources, diversify their livelihoods, and reduce pressure on natural forests [

11]. Previous studies have mostly emphasized the roles and impacts of homestead agroforestry at Kamalganj Upazila [

12,

13] and have not explored other social forestry practices.

Lawachara National Park (LNP) is one of the Protected Areas of Bangladesh located at Kamalganj upazila (sub-district) of Maulvibazar district under Sylhet division, which is nearly 160 km northeast of the capital Dhaka of Bangladesh. The notified area of the park is 1250 ha [

17]. This research study deals with the perspectives of members involved in co-management regarding the protection of the area at LNP. Co-management in protected areas, particularly at Lawachara National Park, has demonstrated how local participation may improve biodiversity conservation while generating alternative income sources for forest-dependent households [

14]. These initiatives contribute to rural development while simultaneously advancing the broader national and global goals of environmental sustainability and poverty alleviation.

Despite the growing importance of social forestry in combating deforestation, livelihood insecurity, and climate challenges, this study focuses on the practices and co-management strategies adopted in Kamalganj Upazila. The research aims to assess the role of social forestry in improving socio-economic conditions, identify the challenges faced by beneficiaries, and analyze its potential as a sustainable land management technique in Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of the Study Area

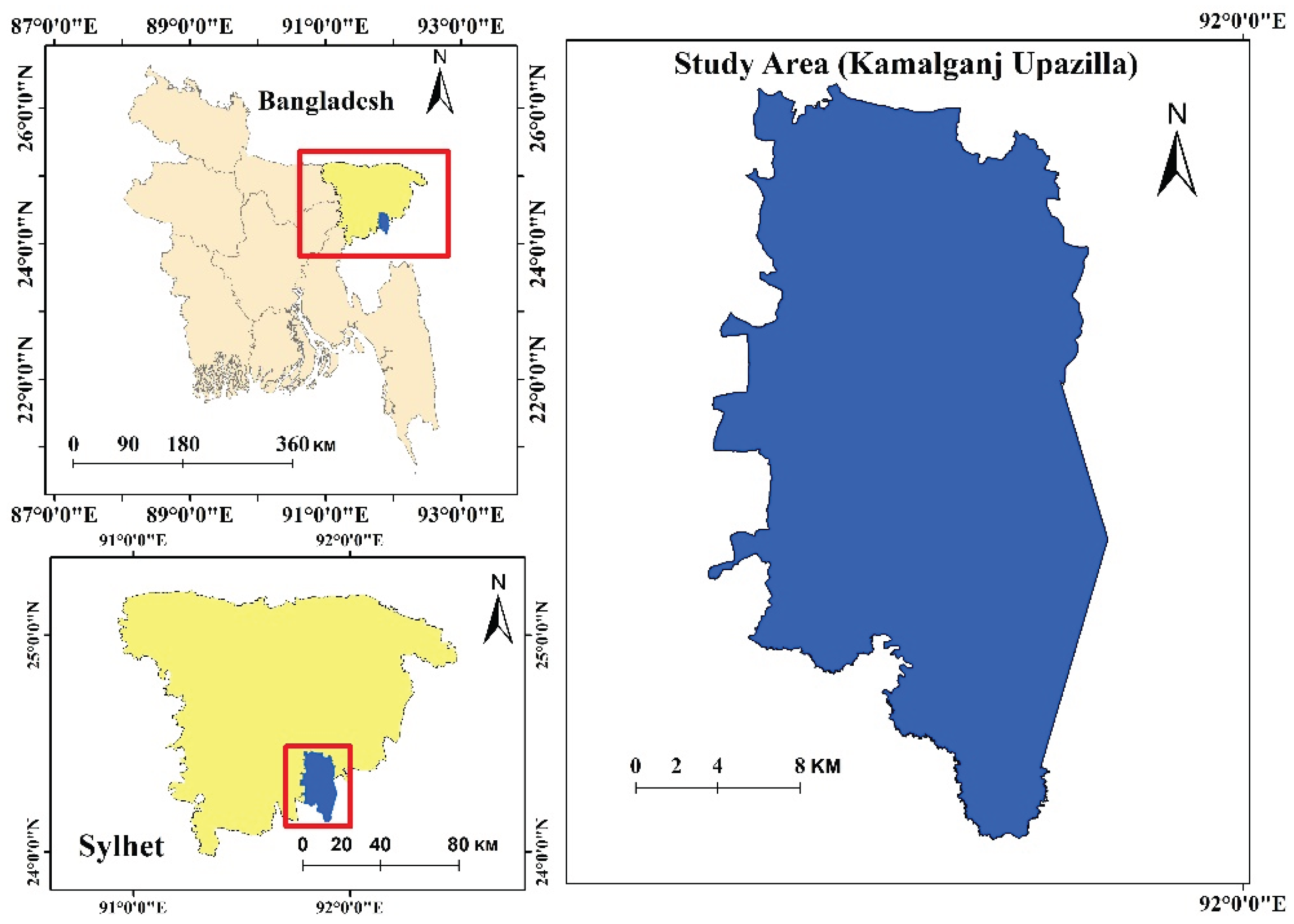

The study was conducted in Kamalganj Upazila of Moulvibazar District, Sylhet Division, Bangladesh, focusing particularly on the Munshibazar region and the Kamarchora Forest Beat under the Rajkandi Range. The research was carried out during September 2024 to document and assess the social forestry activities practiced in the area. A map of the study area is presented in

Figure 1.

The study area was selected for the strip plantations, woodlot plantations, and community participation under social forestry programs. Munshibazar was chosen for its well-developed strip plantation, while Kamarchora Forest Beat was selected for its operational woodlot garden.

2.2. Sampling Technique and Respondents

A total of 32 beneficiaries involved in social forestry activities were purposively selected for this study. Respondents included participants engaged in strip plantations, woodlot plantations, and community forest management systems. All respondents were residents of the Kamalganj Upazila and directly involved in the program.

2.3. Data Collection

Primary data were collected through a structured questionnaire, consisting of both open- and closed-ended questions. The questionnaire covered socioeconomic characteristics, household profile, and involvement in the plantation program, benefits received, and perceptions of the co-management system. Before commencing the interview, each participant received a concise overview of the objectives of this study, and they were assured that all information would remain confidential.

The survey started at Munshibazar, where strip plantations were observed, followed by field visits to the Rajkandi Reserve Forest to assess woodlot plantations. Interviews were conducted in the field during regular work activities.

Additionally, a discussion session was held with members of the Co-Management Committee (CMC) of Lawachara National Park at the Lawachara Rescue Center to obtain insights regarding management practices, responsibilities, and challenges faced by co-management groups.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

Qualitative data gathered from the interview were transformed into quantitative data through appropriate scoring methods. Data were then systematically organized and analyzed according to the study objectives. Pearson’s Correlation (r) was applied to examine relationships between selected socioeconomic variables using MS Excel and R software. The computed correlation values were compared with standard tabulated values to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

The social forestry activities observed in Kamalganj Upazila included strip plantations, woodlot plantations, and the establishment of plantations along railway lines, all of which were operated under a 10-year agreement with a renewable term of an additional 30 years, divided into three installments. These activities primarily engage landless and marginalized households, impoverished tribal communities, destitute women, and forest villagers, with a five-member management committee selected from nearby villages. According to information obtained from the Assistant Conservator of Forests, the Munshibazar strip plantation and the Kamarchora woodlot represent the principal operational sites in the area.

In Munshibazar, the first rotation of the strip plantation had been completed, and the second rotation was found to be progressing satisfactorily. The plantation covers approximately 3 km, with seedlings spaced at 2 m × 2 m. Acacia auriculiformis dominated the stand composition, reflecting its fast-growing nature and suitability as fuelwood. Native species are being promoted under the Sustainable Forest and Livelihood (SUFAL) initiative. Beneficiaries reported collecting fuelwood and receiving economic incentives during harvest. From the first rotation, 15 beneficiaries received Tk. 4,05,330 as their 55% share, consistent with the provisions of people-oriented forestry in Bangladesh. A subsequent plantation was established in 2018–2019, expanding participation to 30 beneficiaries.

At Kamarchora Forest Beat, the 10-hectare woodlot plantation was divided into 13 plots, where 30 beneficiaries were involved in management. From the sale of eight lots, 30 beneficiaries received Tk. 17,37,623 as their 45% share. Beneficiaries reported no operational difficulties and noted improvements in their socioeconomic conditions following participation in social forestry.

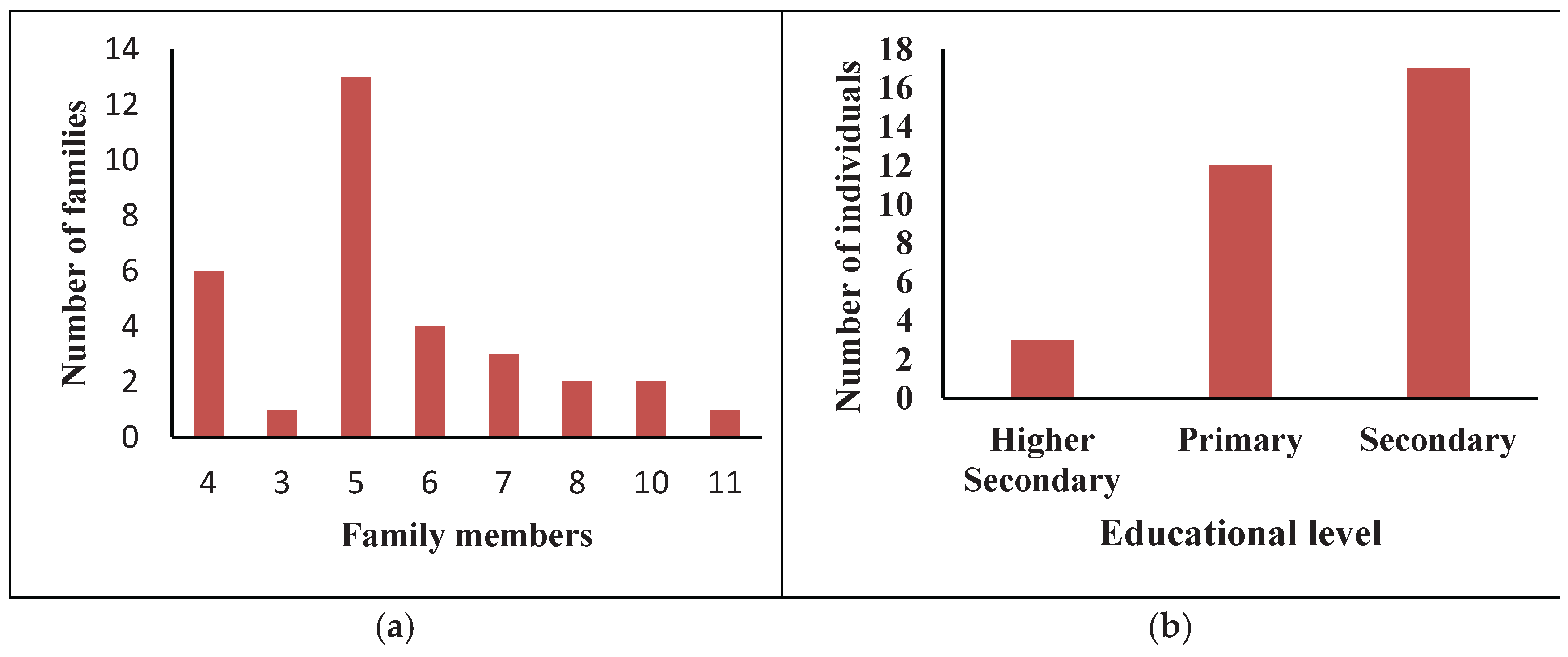

A total of 32 male respondents participated in the survey. Their ages ranged from 30 to 60 years, with household sizes between 3 and 11 members (

Figure 2a). Educational attainment varied: 10% completed higher secondary, 40% primary, and 50% secondary education (

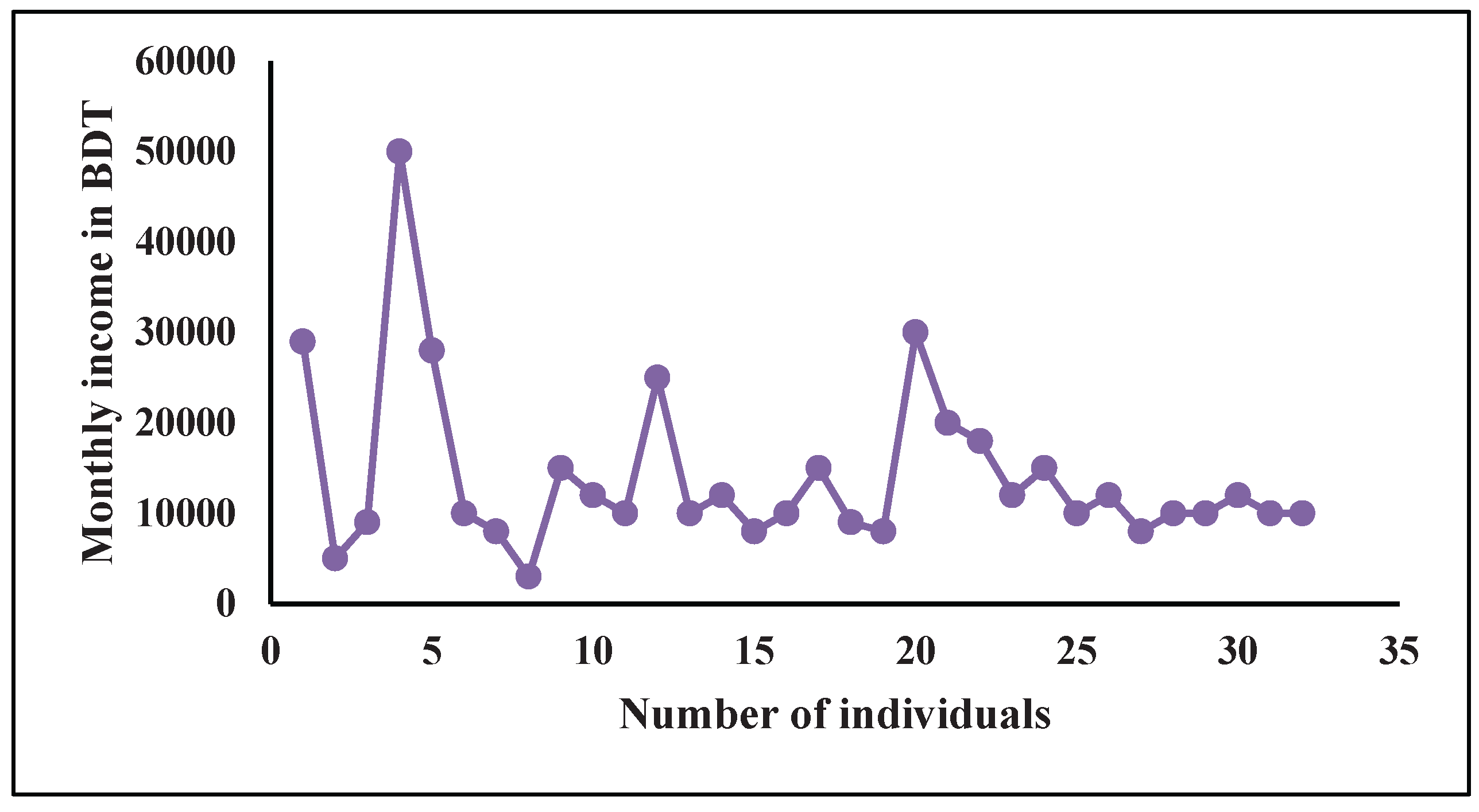

Figure 2b). A statistically significant relationship was observed between family size and education level (p < 0.05). Monthly incomes ranged from Tk. 3000 to Tk. 50,000 (

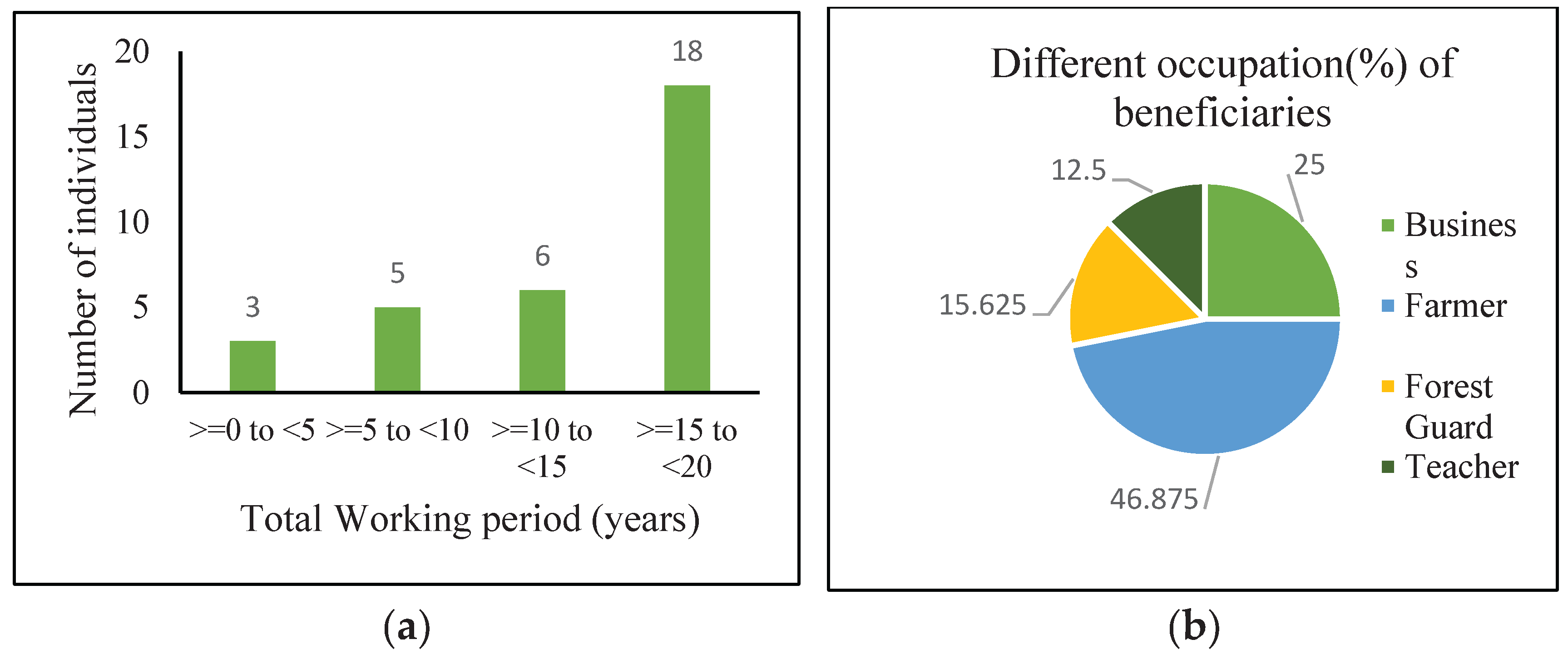

Figure 3) with occupations including farming, business, teaching, labor work, and forest guarding (

Figure 4a). Most beneficiaries had more than 15 years of involvement in social forestry (

Figure 4b).

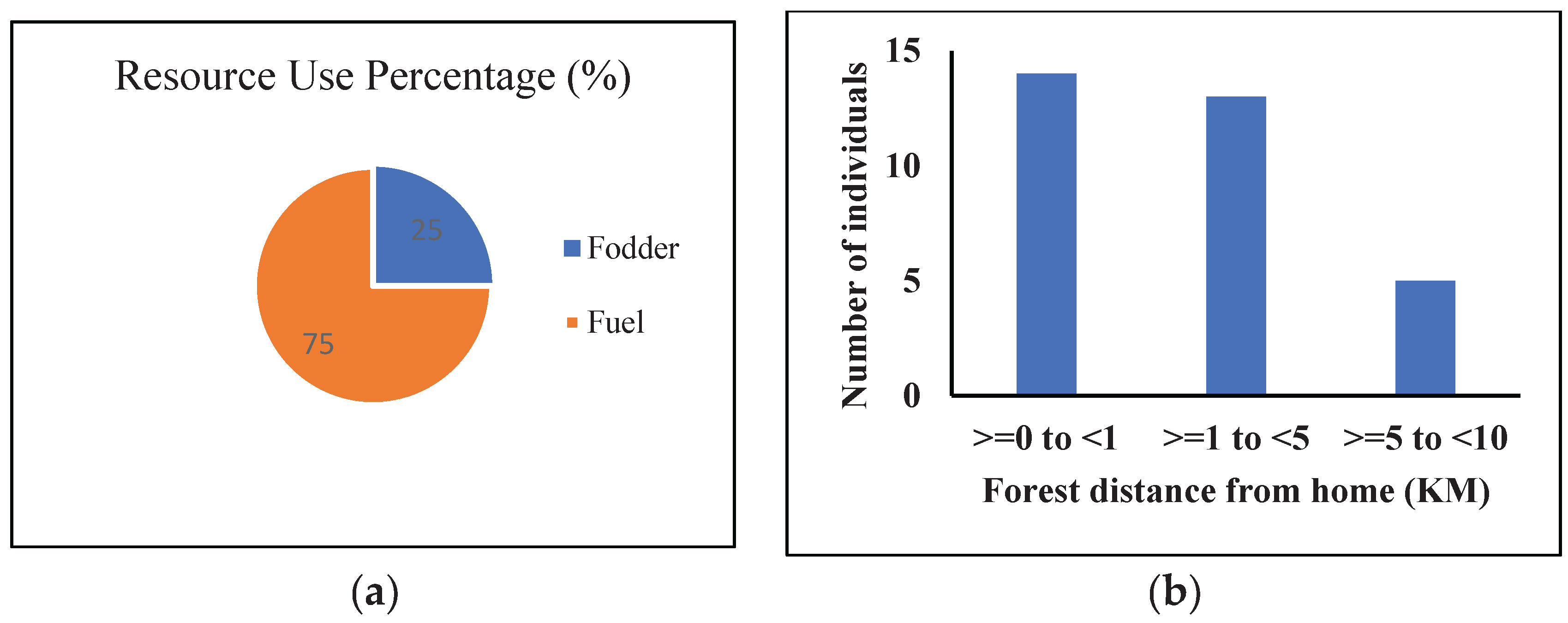

Respondents obtained multiple benefits from the plantation forests, including 20–25 mounds of seasonal fuelwood (

Figure 5a). Satisfaction levels were generally high, with 30% delighted, 40% moderately satisfied, and 30% satisfied. Most beneficiaries lived within 1 km of the plantation and traveled on foot (

Figure 5b). Planted species included

Acacia auriculiformis,

Albizia procera, Chukrasia tabularis, and

Melia azedarach, none of which included perennial fruit species (

Table 1). Beneficiaries suggested incorporating indigenous fruit trees such as jackfruit and guava. Occasional illegal felling was reported, but had decreased substantially due to community monitoring and enforcement. Under the SUFAL program, beneficiaries could access Alternative Livelihood Generation (ALG) loans of approximately Tk. 42,000, although requests for expanded loan opportunities were common.

Co-management interactions at Lawachara National Park indicated active participation of community groups, including 35 Village Conservation Forums (VCFs) and community patrolling groups, consistent with collaborative forestry frameworks previously implemented in Bangladesh.

4. Discussion

Tree diversity in both strip and woodlot plantations was comparatively low, dominated by fast-growing timber species rather than mixed agroforestry compositions. This contrasts with agroforestry systems documented in previous studies, where diverse associations of trees, vegetables, and crops contributed significantly to ecological and economic resilience [

12]. Only two social forestry practices, strip and woodlot plantations, were observed in this study, whereas Rashid et al. [

15] identified 11 traditional agroforestry practices in Pabna district, and three classes of agroforestry systems were found in another study [

12]. The findings emphasize the need for further research to better understand the ecological and economic contributions of existing social forestry systems and explore diversification opportunities.

Beneficiaries reported a variety of advantages from social forestry, including fuelwood, fodder, and seasonal income. These benefits align with earlier agroforestry studies, which identified shade, daily household resources, and cash income as major outputs of tree-based land-use systems [

12]. The consistent availability of fuelwood from plantations remains particularly important in rural Bangladesh, where alternative energy options are limited.

Occupational patterns among beneficiaries, presented in

Figure 4b, largely mirrored findings from previous studies. Farming was the dominant profession (46.88%), followed by business (25%), forest guarding (15.6%), and schooling (12.5%), as supported by earlier socio-economic assessments of agroforestry participants in the region [

13]. The diversity of occupations reflects the inclusive nature of social forestry, engaging individuals across economic backgrounds and livelihood strategies.

The age distribution of beneficiaries (30–60 years, average 45 years) closely aligns with findings from earlier demographic studies in Kamalganj Upazila, where respondents’ ages ranged from 25 to 80 years with an average of 43.66 years [

13]. Similar age distributions have been reported in other districts, such as Tangail, where respondent ages ranged from 19 to 70 years [

12]. This suggests that social forestry programs predominantly attract middle-aged adults who have established links to rural livelihoods.

Educational levels recorded in this study (

Figure 2b) are consistent with findings by Singha et al. [

13], who reported similar distributions among homestead agroforestry practitioners in Kamalganj. These consistent patterns indicate that social forestry is accessible across educational levels and supports diverse communities.

Family sizes (3–11 persons, avg. 5.75) also align with previous regional studies, such as Singha et al. [

13], where family sizes ranged from 2 to 11 with an average of 4.71. The present findings are also close to the national average family size of Bangladesh (5.6) [

16]. Larger family units are likely to rely more heavily on social forestry resources, reinforcing the system’s importance as a livelihood support mechanism.

Co-management at Lawachara National Park was found to play a critical role in reducing illegal extraction and promoting conservation. The activities of Village Conservation Forums and community patrolling groups align with earlier research documenting effective community participation in protected area management [

17]. However, challenges persist, including communication gaps between CMC and VCFs, limited manpower, inadequate training, and increased tourist pressures. Studies indicate that ecotourism development, awareness-building, and alternative income generation can mitigate these issues and enhance conservation outcomes.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that social forestry practices in Kamalganj Upazila provide meaningful socio-economic benefits while facilitating community-based conservation. However, diversification of species, improved financial mechanisms, enhanced training, and stronger co-management coordination are essential to ensure long-term sustainability and ecological resilience.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed the socioeconomic characteristics, benefits, and management conditions associated with strip and woodlot plantations practiced under social forestry programs in Kamalganj Upazila. The findings show that participation in these activities has contributed positively to the livelihoods of the beneficiaries, who reported improvements in income, access to fuelwood, and overall socioeconomic stability following their engagement in the program. Although most participants were male, the gradual involvement of women indicates growing inclusivity within community-based forestry initiatives. The beneficiaries generally lived close to the plantation sites, which facilitated active participation in planting, maintenance, and protection activities. The results also highlight the importance of selecting appropriate tree species to enhance the long-term sustainability of the program. While the existing plantations rely primarily on fast-growing timber species, beneficiaries expressed interest in incorporating multipurpose and indigenous trees to increase ecological resilience and generate additional household benefits. Discussions with the co-management committee at Lawachara National Park further emphasized the importance of community participation, shared responsibilities, and alternative livelihood opportunities in mitigating pressure on forest resources and enhancing conservation outcomes. The insights gained from this research underscore the potential for social forestry to make a meaningful contribution to sustainable land management and community development in Bangladesh.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.A.; methodology, F.J.A.; software, F.J.A.; validation, F.J.A. and S.K.T.; formal analysis, F.J.A.; resources, F.J.A. and S.K.T.; data curation, F.J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.A. and S.K.T.; writing—review and editing, S.K.T.; visualization, S.K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions during this review phase of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or any personal circumstances that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FD |

Forest Department |

| LNP |

Lawachara National Park |

| CMC |

Co-management committee |

| PA |

Protected Area |

| SUFAL |

Sustainable Forest and Livelihood |

| ALG |

Alternative Livelihood Generation |

| VCF |

Village Conservation Forums |

References

- Choudhury, J. K.; Hossain, M. A. A. Bangladesh forestry outlook study. APFSOS II. Bangkok, Thailand: Food and Agriculture Organization, 2011.

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010: Country Report, Bangladesh. Rome, 2010.

- Mia, A. L. Participatory forestry approaches in Bangladesh: The perspective of Mymensingh Forest Division. In World Forestry Congress, 2003, (Vol. 12, pp. 11-14).

- Forestry Master Plan. Environment and land use. Asian Development Bank (TANO- 1355- BAN) UNDP/FAO, BGD/88/025, 1993.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statics (BBS). Statistical Year Book of Bangladesh, Ministry of Planning, Government of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka, 2002.

- Muhammed, N.; Koike, M.; Sajjaduzzaman, M. D.; Sophanarith, K. Reckoning social forestry in Bangladesh: policy and plan versus implementation. Forestry, 2005, Volume 78(4), pp. 373-383. [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statics (BBS). Statistical Year Book of Bangladesh, Ministry of Planning, Government of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh, Dhaka, 2010.

- Nishorgo Support Project (NSP). Restoration of degraded forest habitat: Monitoring report Lawachara National Park, 2005-06 & 2006-07. NSP, NACOM. 2007.

- Sharma, R. A. Co-Management of Protected Areas in South Asia with Special Reference to Bangladesh, 2011. Volume 21(1), pp.1–28. [CrossRef]

- BFD. Bangladesh Forest Department - Protected Area Co-management Rule, 2017. https://bforest.portal.gov.bd/site/page/5430ce33-561e-44f6-9827-ea1ebaa2c00d/.

- Muhammed, N.; Koike, M.; Haque, F.; Miah, M. D. Quantitative assessment of people-oriented forestry in Bangladesh: A case study in the Tangail forest division. J. Environ. Manage., 2008. Volume 88(1), pp. 83-92. [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Uddin, M. S.; Banik, S. C.; Kasem, M. A. Homestead agroforestry systems practiced at Kamalganj upazila of Moulvibazar District in Bangladesh. Asian J. Res. Agric. For, 2018. Volume 2(2), pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Uddin, M. S.; Banik, S. C.; Goswami, B. K.; Kashem, M. A. Impact of homestead agroforestry on socio-economic condition of the respondents at Kamalganj upazila of moulvibazar district in Bangladesh. Asian J. Res. Agric. For, 2019. Volume 3, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. S. Comparative evaluation of co-management impacts on protected area: A case study from Lawachara National Park, Maulvibazar, Sylhet. JFE, 2007.

- Rashid, M.H.; Islam, K.K.; Mondol, M.A.; Land Pervin, M.J. Impact of traditional homestead agroforestry on the livelihood of the respondents in northern Bangladesh. J. Agrofor. Environ. 2007; Volume 2(1), pp. 11-14.

- Anonymous. Working paper for 3rd National Project Steering Committee Meeting. 3PFS, DAE, Dhaka, 2005.

- Islam, M. W. Comanagement approach and perceived ecotourism impacts at Lawachara National Park in Bangladesh. Wageningen, Netherlands: Wageningen University and Research Centre, 2009.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).