1. Introduction

In recent decades, frontier questions in modern physics have begun to reveal the conceptual limits of explanations grounded solely in empirical verification or mathematical formalism. Foundational problems—such as the emergence of mass, the ontological status of vacuum energy, the discreteness or continuity of spacetime, and the mechanisms underlying symmetry breaking—cannot be resolved by formal modeling alone. They require broader ontological categories capable of addressing intelligibility, ordered relations, and the conditions of manifestation (Penrose, 2004; Smolin, 2019). Although contemporary theories such as quantum field theory, general relativity, and various approaches to quantum gravity describe physical behavior with remarkable precision, their ontological commitments remain contested. This has led philosophers of science to argue that the conceptual vocabulary of physics has shifted from substance to structure (Ladyman & Ross, 2007; French, 2014) and that emergence is best understood through functional and relational patterns rather than intrinsic essences (Mitchell, 2009).

Within the Islamic intellectual tradition, the Qur’an articulates a symbolic–metaphysical ontology that likewise privileges structure, orientation, and function over material mechanism. The Qur’an does not present a catalogue of physical laws; rather, it offers a metaphysical cartography that discloses the conditions of intelligibility, the ordering principles of existence, and the divine grounding of meaning. Among its symbolic articulations, Qur’an 24:35—the Verse of Light—occupies a paradigmatic position:

“God is the Light(Nūr) of the heavens and the earth.

The likeness of His Light is as a niche containing a lamp;

the lamp is within a glass;

the glass is as if it were a brilliant planet.

It is lit from a blessed olive tree, neither of the East nor of the West;

its oil would almost shine even if untouched by fire.

Light upon Light. God guides to His Light whom He wills.

And God sets forth parables for humankind, and God is Knowing of all things.” (Qur’an 24:35)

Classical exegetes—including al-Ghazālī, Ibn al-ʿArabī, and Mullā Ṣadrā—did not treat these symbols as descriptions of discrete physical objects. Rather, they interpreted them as components of a hierarchical and relational ontology in which each element—orientation (miškāt), activation (miṣbāḥ), mediation (zujāja), latent potentiality (zayt), and manifestation (nūr ʿalā nūr)—performs a distinct metaphysical function (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019). Modern scholars such as Izutsu (2002), Chittick (1998), Nasr (1987, 2001), and Rahman likewise emphasize that the verse articulates a symbolic grammar of intelligibility rather than a physical model.

This study adopts an explicitly structural–functional methodology. The symbolic elements of the verse are analyzed not by ontological equivalence but by their patterned roles within a relational architecture in which meaning arises through structural placement, graded mediation, and functional interaction. The niche, lamp, glass, oil, and layered illumination are thus treated as elements within an ordered system

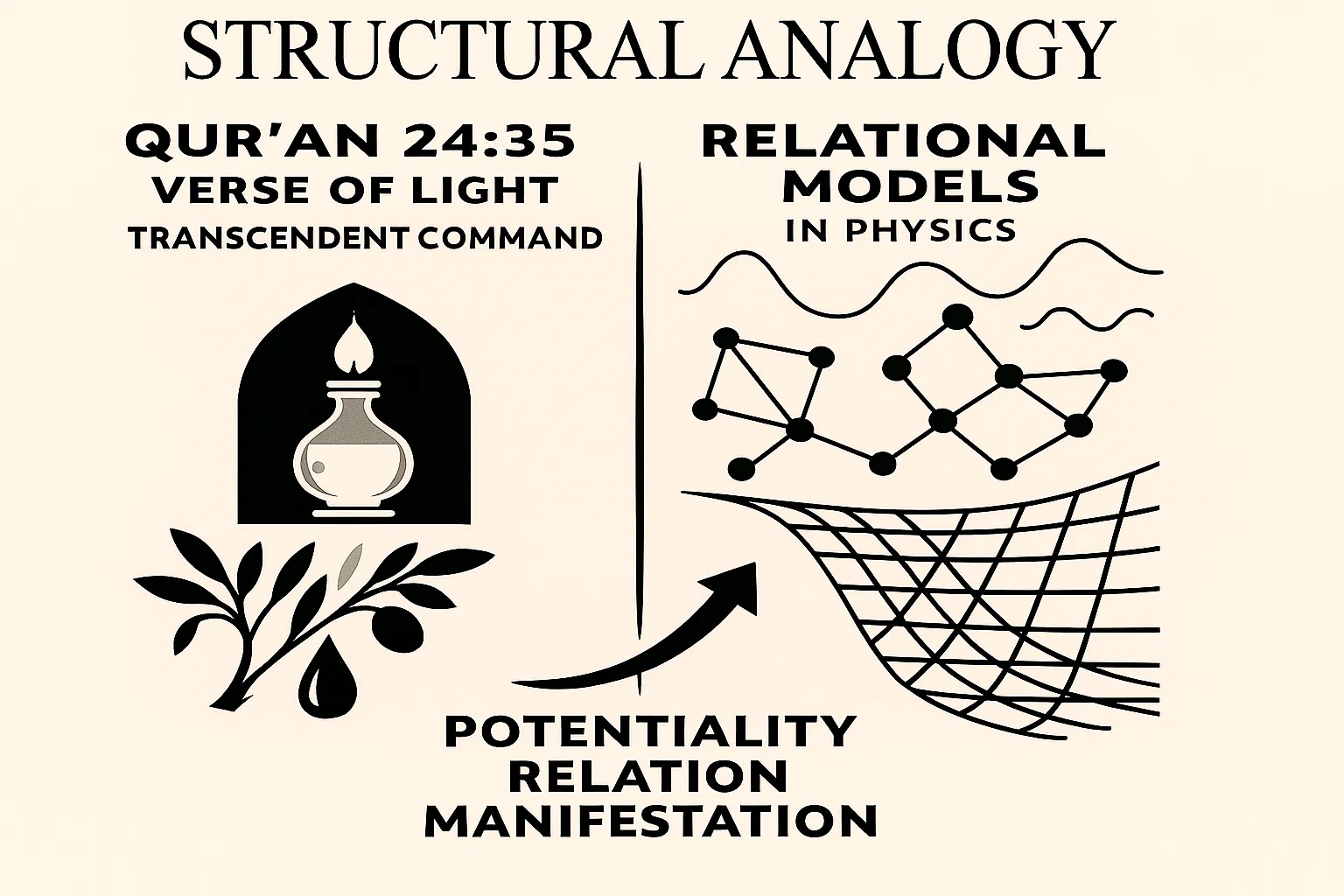

i. This approach resonates with ontic structural realism, which maintains that structures and relations—not substances—constitute the fundamental fabric of reality (French, 2014; Ladyman & Ross, 2007). In this sense, the Qur’anic parable can be understood as a symbolic analogue to contemporary relational ontologies.

The proximity between these domains becomes particularly clear against the backdrop of recent developments in modern physics. Quantum theory models particles as relational excitations of fields; loop quantum gravity describes spacetime as a network of discrete relations rather than a continuous background (Rovelli, 2018; Wüthrich, 2020); and contemporary cosmology interprets the vacuum not as absence but as a structured matrix of latent potentialities (Carroll, 2019). These shifts redirect attention from substances to functional patterns, from intrinsic qualities to relational configurations, and from static entities to emergent structures—parallels that closely echo the semantic–relational architecture of Qur’an 24:35.

The aim of this article is not concordism, nor the extraction of scientific predictions from scripture, nor the reduction of physics to mystical allegory. Rather, it is to identify structural resonances—pattern-level correspondences—between Qur’anic symbolic ontology and contemporary scientific conceptualizations of relationality and emergence. Waḥy, ʿaql, and ṭabīʿa are treated as distinct yet intersecting epistemic axes. Through a structural–functional lens, the Verse of Light articulates a metaphysical schema—orientation, mediation, potentiality, activation, manifestation—that aligns with modern relational accounts of reality while remaining grounded in its own theological horizon.

2. Conceptual Framework: Revelation–Reason–Nature

This study is grounded in a tripartite epistemic architecture that treats waḥy, ʿaql, and ṭabīʿa as distinct yet mutually illuminating avenues of intelligibility. Rather than conceiving these domains as competing explanatory systems, the broader Islamic intellectual tradition—as well as contemporary philosophy of science—understands them as complementary modalities through which reality becomes knowable, each with its own hermeneutical norms and ontological presuppositions (Izutsu, 2002; Abdelnour, 2023; Malik, 2025). This framework allows symbolic ontology, philosophical analysis, and empirical regularity to enter conceptual dialogue without collapsing their epistemic identities.

2.1. Revelation (Waḥy) and Ontological Symbolism

In the Qur’anic worldview, metaphysical knowledge unfolds through symbolic configurations rather than propositional abstractions (For a contemporary example regarding the possibility of knowledge, see Zorba (2016)). The symbols of Qur’an 24:35—miškāt, miṣbāḥ, zujāja, zayt, and nūr ʿalā nūr—do not describe empirical entities but articulate an ontology of manifestation in which graded modes of being are expressed through layered images. Classical exegetes, particularly al-Ghazālī in Mishkāt al-Anwār and later Sufi metaphysicians, interpret these symbols as encoding a structural architecture of intelligibility that delineates how existence becomes knowable, oriented, mediated, and disclosed (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; Chittick, 1998). Revelation thus functions as a symbolic map of ontological relations, rendering the cosmos an ordered field of meaning rather than an undifferentiated totality.

2.2. Reason (ʿAql) and Philosophical Mediation

Reason serves as the mediating faculty that interprets, analyzes, and systematizes the symbolic structures disclosed through waḥy and observed in ṭabīʿa. Within both Islamic philosophy and contemporary metaphysics, ʿaql denotes more than formal logic; it includes conceptual abstraction, analogical reasoning, ontological modeling, and the search for coherence across domains. Through reason, symbolic images are clarified, relational patterns are articulated, and the implications of their structural arrangement become philosophically explicit. In this study, ʿaql provides the methodological basis for exploring structural parallels between Qur’anic imagery and modern scientific frameworks without asserting equivalence or collapsing distinct ontological registers.

2.3. Nature (Ṭabīʿa) and the Order of Phenomena

Nature is approached as the domain in which empirical regularities appear in structured patterns, not as a repository of doctrinal proofs. Contemporary physics—whether in field theory, symmetry-breaking cosmology, or relational interpretations of spacetime—presents accounts of form, constraint, and emergence that raise ontological questions analogous to those explored within Islamic philosophical theology. These scientific models remain methodologically autonomous: they describe phenomena rather than metaphysical meaning. Yet their structural vocabulary—relations, networks, potentialities, excitations, constraints—offers conceptual resources for understanding how patterned intelligibility arises within the natural order (Rovelli, 2018; Wüthrich, 2020; Carroll, 2019). Nature thus contributes the relational and functional motifs that render empirical reality available for philosophical reflection.

2.4. Intersections Without Reduction

Within this tripartite framework, waḥy, ʿaql, and ṭabīʿa intersect without reducing one domain to another. Waḥy provides symbolic-metaphysical orientation; ṭabīʿa presents structured phenomena and conceptual patterns; ʿaql mediates between them by articulating categories such as manifestation, relationality, hierarchy, potentiality, and form. This relational model enables the exploration of structural affinities between Qur’anic symbolic ontology and contemporary scientific accounts while preserving non-concordism and resisting both theological reductionism and scientistic overreach. The aim is analogy rather than verification, resonance rather than equivalence, dialogue rather than synthesis.

Grounding the study in this framework establishes the epistemic boundaries necessary for a disciplined analysis of the Verse of Light, clarifying how Qur’anic symbolism and modern physics may converge at the level of structural patterns while operating within distinct modes of intelligibility.

3. Methodology: Structural Analogy, Non-Concordism, and Hermeneutic Constraints

This study employs a structural–analogical methodology to examine conceptual resonances between Qurʾān 24:35 and selected ontological themes in contemporary physics. Because scholarship at the intersection of science and religion often blurs the distinctions between empirical explanation, theological exegesis, and metaphysical reflection, this section establishes the epistemic constraints necessary for a disciplined conceptual dialogue. The aim is to articulate structural parallels without collapsing distinct domains or suggesting cross-domain verification.

3.1. Structural Analogy as Conceptual Mapping

Structural analogy functions here as a hermeneutic instrument rather than an explanatory or empirical tool. In the philosophy of science, analogies operate as “selective likenesses” (Hesse, 1963), mapping relational patterns across domains without implying material identity or ontic correspondence. Van Fraassen (1980) likewise emphasizes that scientific models illuminate structural relations while abstracting from concrete physical content; their value lies not in literal representation but in the intelligible patterns they reveal.

Following this insight, the symbols of the Light Verse—miškāt, miṣbāḥ, zujāja, zayt, and nūr ʿalā nūr—are examined at the level of form, pattern, and functional role. These symbols are not interpreted as physical entities or anticipations of scientific discovery; rather, they serve as conceptual templates for themes such as gradation, mediation, transparency, potentiality, and manifestation. Their structural roles can thus be placed in dialogue with analogous motifs found in philosophical interpretations of modern physics.

3.2. No Empirical Inference, Prediction, or Verification

Because structural analogies are conceptual and hermeneutical, they do not constitute scientific hypotheses. They are neither testable nor falsifiable in a Popperian sense (Popper, 2002), nor do they belong to the “hard core” of scientific research programs as described by Lakatos (1970). Their purpose is heuristic and metaphysical: to illuminate ontological themes rather than to explain physical mechanisms.

Accordingly:

This methodological separation preserves the epistemic integrity of both the scientific and scriptural domains.

3.3. Disciplinary Non-Reduction and Epistemic Autonomy

This study treats revelation, philosophical reasoning, and scientific explanation as autonomous epistemic domains, each governed by its own methodological norms and epistemic aims. Concordist approaches have been criticized for collapsing these domains into one another; at their most reductive, such models obscure the differences between empirically constrained scientific theory and the symbolic–metaphysical orientation of revelation (Brooke, 1991; Guessoum, 2008; Bigliardi, 2017).

Within this framework, Qurʾān 24:35 is approached not as a bearer of empirical content but as a symbolic articulation of categories such as gradation of being, mediation, orientation, and manifestation. Conversely, contemporary physics is not used as a hermeneutical key for revelation; scientific models retain their autonomy and appear in this study only insofar as their structural motifs—relationality, symmetry breaking, discreteness, emergence—lend themselves to philosophical reflection.

The relationship among these domains is therefore framed in terms of conceptual resonance rather than mutual confirmation. None is reduced to another, and none serves as the epistemic criterion for the others.

3.4. Hermeneutic Sources and Interpretive Limits

The interpretive analysis is anchored in classical Islamic metaphysics—particularly al-Ghazālī’s

Mishkāt al-Anwār, Ibn ʿArabī’s doctrine of

ẓuhūrii, and later Sufi elaborations expounded by Chittick (1989) and Izutsu (2002). These traditions understand Qurʾān 24:35 as presenting a layered ontology of being and manifestation rather than a physical description.

Contemporary physics contributes only at the level of conceptual vocabulary—fields, relations, symmetry breaking, discreteness, potentiality, and emergence—which is employed hermeneutically rather than empirically. These scientific motifs are used to illuminate structural features of Qurʾānic symbolism, not to provide explanatory reduction.

3.5. Epistemic Modesty and Domain Separation

The methodological framework is grounded in epistemic modesty: structural parallels between metaphysical symbolism and scientific ontology do not entail identity, equivalence, or mutual validation. Qurʾānic exegesis, philosophical argument, and empirical science operate under distinct epistemic norms.

The guiding commitments of this study are therefore:

structural analogy rather than empirical correspondence;

conceptual resonance rather than verification;

domain autonomy rather than reduction;

philosophical exploration rather than synthesis.

By upholding strict domain separation while permitting pattern-level comparison, this methodology safeguards the integrity of revelation, reason, and nature as independent yet mutually illuminating sources of intelligibility.

4. The Verse of Light and Scientific Parallels

Qurʾān 24:35 does not begin with a cosmogenetic account but with an ontological proclamation: “God is the Light of the heavens and the earth.” Read structurally, the verse situates nūr not as physical luminosity but as the principle that renders existence intelligible, distinct, and knowable (Chittick, 1998; Zorba, 2016). The imagery that follows constructs a layered symbolic architecture in which the niche, lamp, glass, oil, and light encode relational roles rather than discrete material entities. This multilayered structure makes the verse unusually amenable to a structural–functional reading while remaining faithful to classical Islamic metaphysics.

4.1. Miškāt (Niche): The Horizon of Ontological Orientation

Literally an alcove designed to hold a lamp, the miškāt in the Qurʾānic parable functions as an orienting horizon rather than a container. Classical exegetes, especially al-Ghazālī, read it as the non-spatial and non-temporal “encompassing” of divine intelligibility—the metaphysical frame through which illumination becomes possible (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; Izutsu, 2002). It designates the transcendent backdrop against which manifestation can occur, not a physical location in which God resides.

Structurally, this role resonates with Schrödinger’s notion of “negative entropy” as an enabling horizon—one that does not produce order but makes ordered processes possible through orientation, boundary, and directionality (Schrödinger, 1944; Prigogine & Stengers, 1984)

iii. The analogy is conceptual: it highlights the pattern readiness → activation → sustained order without importing thermodynamic categories into scripture.

Thus, the miškāt symbolizes continuous, indivisible ontological unity—the unitive ground that renders relationality intelligible.

4.2. Zujāja (Glass): The Mediating Domain of Manifestation

The verse situates the lamp “within a glass” (zujāja). In both classical exegesis and structural–analogical reading, the glass serves as an active mediator rather than a passive vessel. It shapes, conditions, and configures the diffusion of illumination. Epistemically, it functions as transparency; metaphysically, as an intermediary domain; structurally, as a resonator (Nasr, 1987; Chittick, 1998).

In physical optics, the amorphous lattice structure of glass determines how light refracts and reflects. Bohm (1980) describes analogous mediatory structures as “implicate orders” that guide the unfolding of potential. Likewise, the zujāja does not generate nūr but renders it perceptible, giving form to illumination.

In classical metaphysics, the glass corresponds to the ordered layers of the cosmos—domains through which potentiality is received, modulated, and disclosed. For al-Ghazālī, it mediates between transcendent light and its manifest reception, functioning as an intermediate ontological plane (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019).

4.3. Kawkab Durrī (A Brilliant Planet): Relational, Not Essential, Luminosity

The glass is likened to a kawkab durrī, a “brilliant planet.” A planet does not emit light; it reflects it. This distinction is decisive. The metaphor emphasizes that created luminosity is relational, derivative, and contingent rather than essential (Quṭb, 2003; Nasr, 2001). Brilliance arises not from the glass’s essence but from its orientation, refinement, and proper integration with oil, wick, and command.

This relational luminosity aligns conceptually with Prigogine’s account of local negentropic emergence: openness to a sustaining source enables ordered patterns to arise (Prigogine & Stengers, 1984). Thus, the verse symbolically encodes a fundamental metaphysical principle: manifestation depends on receptive structure rather than intrinsic radiance.

4.4. The Oil That “Almost Glows”: Potentiality near Actualization

The phrase

“its oil would almost shine even if untouched by fire” signals a state of heightened potentiality—an ontological threshold between potency and act. Classical exegetes understand this as spiritual preparedness; structurally, it represents metaphysical readiness predisposed toward illumination (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; Chittick, 1998)

iv.

In contemporary physics, this finds a conceptual parallel in the quantum vacuum, which is not empty but characterized by zero-point fluctuations and latent possibilities (Penrose, 2004; Krauss, 2012). Likewise, the Higgs field’s nonzero vacuum expectation value captures structured potentiality awaiting activation under specific conditions (Smolin, 2019). The analogy is strictly structural: in both cases, what appears “inert” is permeated with latent readiness.

Thus, the oil symbolizes a reservoir of potentiality poised on the verge of actualization.

4.5. The Ontological Cosmogram: A Layered Architecture of Manifestation

Taken together, the symbolic elements of the Verse of Light trace a coherent ontological sequence:

Divine nūr — the transcendent ground of intelligibility

Miškāt — the orienting horizon that frames manifestation

Zujāja — the mediating domain configuring appearance

Zayt (oil) — latent potentiality awaiting activation

Nūr ʿalā nūr — manifest illumination

This sequence describes not a physical cosmology but a metaphysical architecture in which existence emerges through ordered relations, layered mediation, and the transition from potentiality to actuality. Qur’anic imagery stands in structural resonance with contemporary ontological models that describe reality as arising from relational networks, structured fields, or discrete processes—while at the same time preserving the grounding and formative role of the transcendent principle (the Divine Light, the Mishkāt).

Thus, the Verse of Light operates as an ontological cosmogram: a symbolic map of how intelligible being becomes manifest through structured mediation from a transcendent source.

5. Glass, Isotropy, and the Mediation of Reality

Among the symbolic elements in the Verse of Light, zujāja (glass) occupies a distinctive metaphysical role. The Qurʾānic description—“as if it were a brilliant planet” (Qur’an 24:35)—indicates that the glass is not merely a transparent vessel but the mediating plane in which illumination becomes structured, intensified, and perceptible. Classical commentators, especially al-Ghazālī, describe the glass as a locus of refinement: transparent enough to transmit illumination, yet sufficiently structured to shape, focus, and condition its diffusion (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019). In this sense, the glass functions as an ontological interface between divine amr (command) and the world of manifest forms.

From a structural–functional perspective, the metaphor gains additional conceptual depth. Glass unites determinate internal order—surface continuity, refractive regularity, and optical homogeneity—with functional capacities such as directing, modulating, and amplifying light. It thus becomes a paradigmatic example of the union of structure and function within a single mediating entity. Philosophically, this reflects a general pattern: complex systems evolve toward increased differentiation while sustaining higher degrees of functional integration (Barbour,1997)

v. The glass in the Qurʾānic parable therefore symbolizes the convergence of ordered transparency and mediatory efficacy. It is both structure—an organized medium—and function—the condition of visibility and intelligibility

vi.

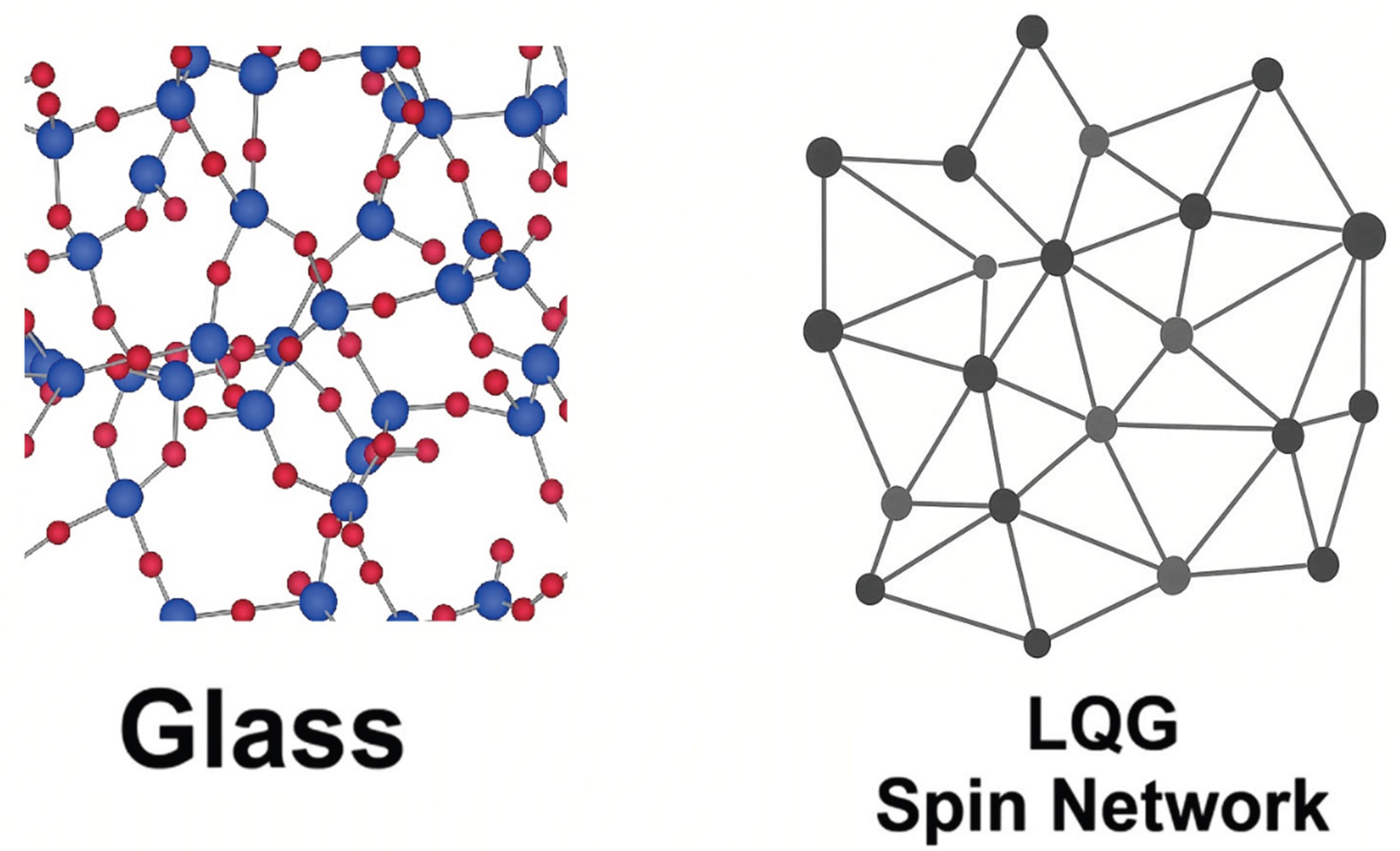

From the standpoint of the physical sciences, glass is itself a structurally unusual material: amorphous, lacking long-range periodic order yet exhibiting stable short-range coordination

Figure 5-1 (Yang et al., 2021; Fan & Ma, 2021; Aykol et al., 2024). While this pertains only to physical glass, its intermediate, neither-crystalline-nor-chaotic character serves as a useful analogical template. Contemporary physics frequently employs analogous intermediate domains—probability amplitudes, vacuum fields, and relational networks—as latent structures that shape observable outcomes despite remaining partly hidden

Figure 5-1 (Rovelli, 2010; Smolin, 2019; Chirco, 2019). These comparisons do not imply empirical correspondence; they draw attention to the conceptual pattern of mediation enacted by underlying, incompletely knowable structure.

Optically, glass exhibits macroscopic isotropy under stress-free conditions (

Figure 5-1), maintaining a constant refractive index regardless of direction or polarization. This physical isotropy offers a symbolic parallel to the large-scale isotropy of the early universe inferred from the cosmic microwave background (Greene, 2004). In both cases, a uniform background provides the enabling ground from which structured differentiation can emerge. These parallels are interpretive rather than empirical; they emphasize the conceptual utility of a homogeneous backdrop for the possibility of ordered manifestation.

Within this interpretive framework, glass exemplifies—strictly at the level of analogy—two principles shared by theological metaphysics and modern physics:

Epistemic transparency: Glass does not generate illumination; it renders it visible. It mediates intelligibility without being the source of Nūr.

Ontological partiality:Glass possesses determinate structure, yet its microscopic configuration is too complex to be exhaustively known. This partial knowability symbolically reflects the limits of human cognition emphasized in classical metaphysics and in modern discussions of uncertainty and indeterminacy (Chittick, 1998; Moosa, 2005; Dyke, 2023).

Taken together, these features show that the glass metaphor articulates a vision of reality that is simultaneously accessible and veiled. Zujāja is not an auxiliary layer; it is the threshold at which illumination acquires form without exhausting its transcendent source. Its symbolic function therefore extends beyond physical transparency: it signifies the intermediate ontological domain in which divine illumination becomes structured manifestation while remaining rooted in an origin beyond form.

6. Tree, Symmetry, and Topological Structures

The Qurʾānic reference to a “blessed olive tree, neither of the East nor of the West” conveys more than geographical neutrality. It symbolizes transcendence, directionlessness, and primordial symmetry. Across Qurʾānic cosmology, the motif of the tree frequently appears as a principle of being extending from an unseen ontological root toward the manifest world, forming a vertical axis that links multiple planes of reality. In the Verse of Light, however, the olive tree is presented without directional bias—“neither East nor West”—suggesting a source beyond conventional spatial coordinates (Qur’an 24:35).

Classical metaphysics often treats the tree as symbolically unified with Being itself, a metaphysical center transcending spatial direction, temporal sequence, and physical orientation (Izutsu, 2002; al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; 1997). This symbolic neutrality resonates structurally—though not empirically—with the large-scale isotropy posited for the early universe: a regime in which no direction is privileged and differentiation has not yet emerged (Planck Collaboration, 2020; Penrose, 2004; Smolin, 2019). Prior to symmetry breaking, fundamental interactions had not separated and particle species had not acquired distinct identities (Particle Data Group, 2024; Horn, 2020).

Symmetry breaking in modern physics refers to the process by which an initially uniform field differentiates into distinct, stable structures. Read analogically, the Qurʾānic “tree neither of the East nor the West” may be understood as a pre-differentiated ontological condition: an undivided state from which multiplicity, orientation, and functional contrast later arise. Its directionlessness mirrors—at the level of conceptual form—the transition from primordial symmetry to structured differentiation (Nasr, 2001; Greene, 2004).

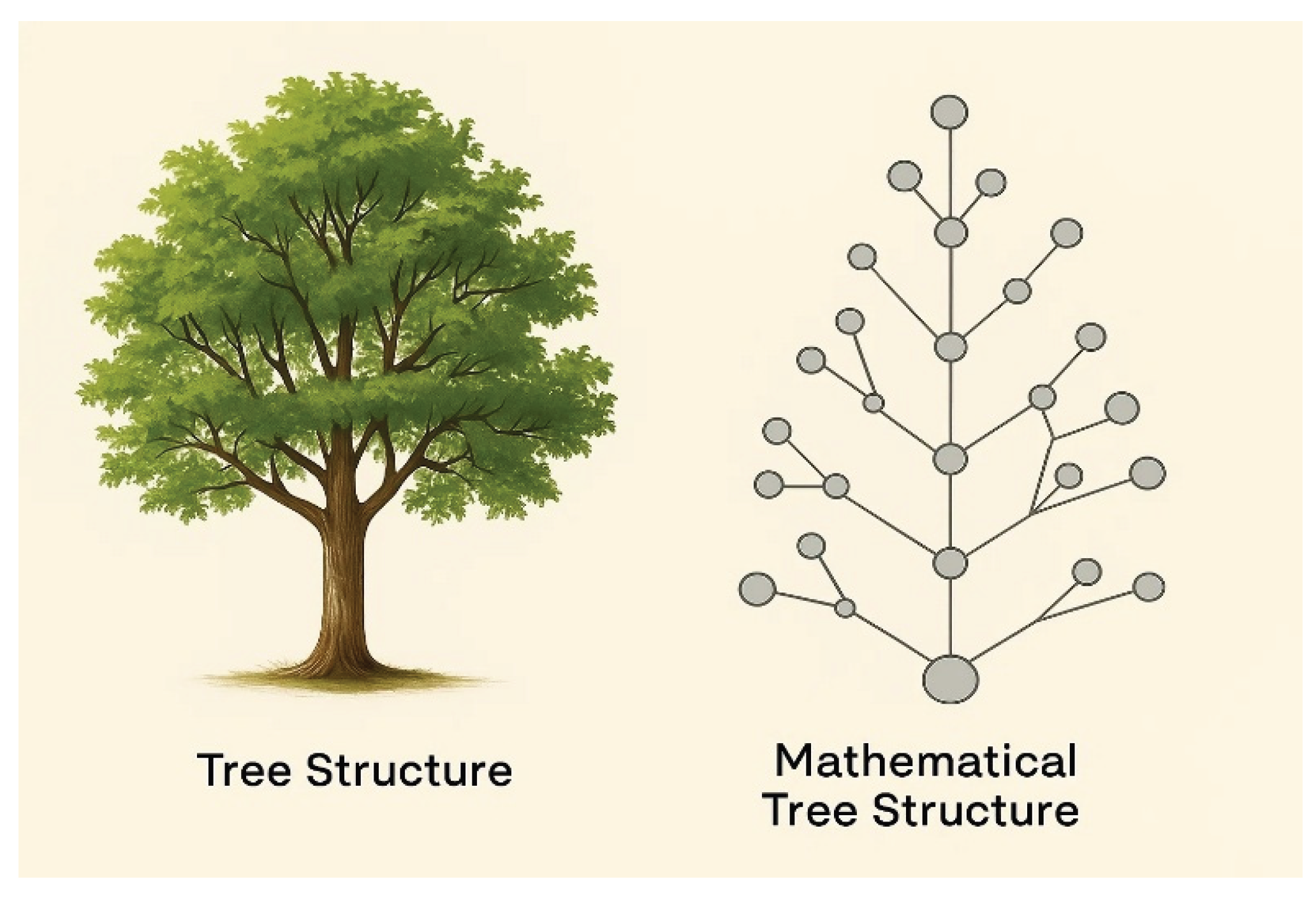

The tree can also be read as a topological rather than strictly biological structure. The Qurʾānic imagery evokes a branching system rooted in a single source—nodes, edges, and graded articulations—closely resembling the organizational logic of networked systems in mathematical physics. In Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG), space is modeled not as a continuous manifold but as a discrete web of vertices and links—spin networks—encoding adjacency and relational structure without presupposing geometric continuity (Rovelli, 2010; Chirco, 2019).

Figure 6-1 visualizes this conceptual parallel by placing a natural tree beside a mathematical tree graph, emphasizing their shared logic of branching topology.

From this perspective, the metaphors of glass and tree converge at the level of abstract structure:

Glass exhibits local organization without long-range periodicity, resembling a disordered yet coherent network (Yang et al., 2021; Fan & Ma, 2021; Aykol et al.).

The tree offers a branching architecture defined by nodes and edges, paralleling graph-theoretic and topological models of connectivity.

Moreover, the verse describes the tree’s oil as “almost glowing even if untouched by fire,” indicating heightened receptivity or latent readiness. Classical commentators regard this as a state of spiritual potentiality; analogically, it recalls modern accounts of pervasive background fields—such as the quantum vacuum or the Higgs field—whose latent potential precedes all excitation (Penrose, 2004; Smolin, 2019).

Taken together, these elements allow the Qurʾānic olive tree to be understood as more than a biological image. It functions as an ontological topology:

grounded in primordial symmetry,

articulated through branching differentiation,

unified by a single root of being,

and charged with latent potentiality.

This reading does not seek empirical correspondence between scripture and physics. Rather, it highlights how Qurʾānic symbolism and contemporary physical models can share parallel structural intuitions. The “tree” thus becomes a symbolic cosmogram expressing the movement from unity to articulated multiplicity—a theme central to both metaphysical reflection and modern relational physics.

Glass and Tree: Metaphysical and Physical Nodes as Analogical Structures

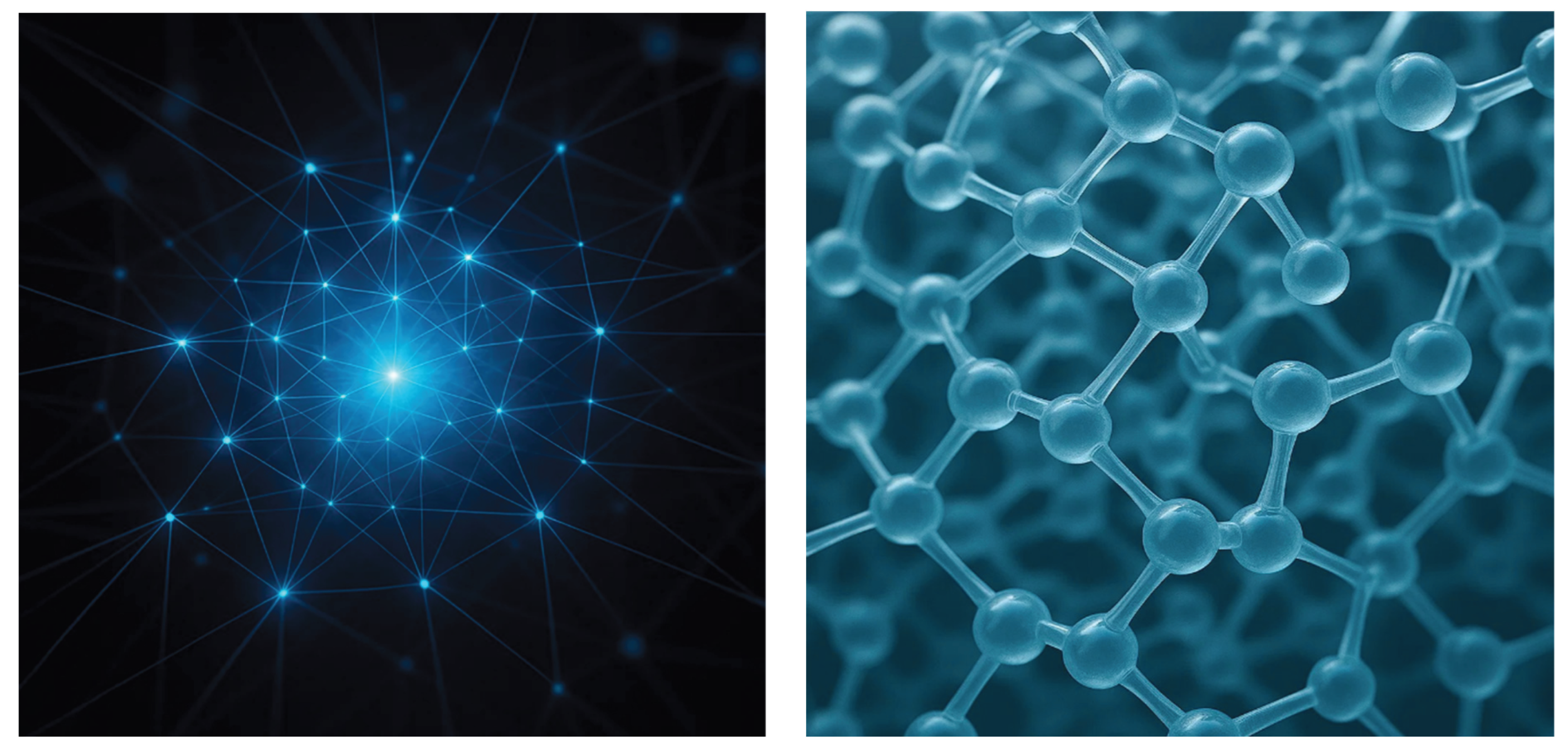

At first glance, the Qurʾānic references to “glass” (zujāja) and to “a blessed tree neither of the East nor the West” (shajarah mubārakah) appear solely symbolic. Yet these metaphors display striking structural affinities with foundational models in contemporary physics. In particular, network-based ontologies—such as spin networks in Loop Quantum Gravity (LQG) and the combinatorial structures of spin foam theory—suggest that space is not a smooth continuum but a discrete relational web of nodes and links (Rovelli, 2010; Smolin, 2019).

In LQG, space is defined at the Planck scale through vertices and edges that collectively form a non-crystalline yet coherent geometrical network. Although the network contains local irregularities, its short-range relations generate large-scale stability: order emerges from a lattice of interconnected, discrete units (Penrose, 2004). As illustrated in

Figure 6-3, this relational architecture manifests as a non-directional, node-based structure that mirrors the organizational logic found in group field theory (Chirco, 2019).

Figure 6-3.

Analogy between relational networks (left) and the amorphous network of glass (right). The left

panel illustrates an abstract relational network that encodes connectivity without fixed coordinates. The right

panel depicts the amorphous silicate glass network—a continuous‐random network with short‐range order

(stable bond lengths/angles) but no long‐range translational symmetry. Taken together, these images reinforce

the Qur’ānic metaphor of “a tree neither of the East nor of the West” as directionless rootedness, and analogically

align relational order in physics with the isotropic, non‐crystalline medium of glass.

Figure 6-3.

Analogy between relational networks (left) and the amorphous network of glass (right). The left

panel illustrates an abstract relational network that encodes connectivity without fixed coordinates. The right

panel depicts the amorphous silicate glass network—a continuous‐random network with short‐range order

(stable bond lengths/angles) but no long‐range translational symmetry. Taken together, these images reinforce

the Qur’ānic metaphor of “a tree neither of the East nor of the West” as directionless rootedness, and analogically

align relational order in physics with the isotropic, non‐crystalline medium of glass.

Within this interpretive framework, the Qurʾānic statement “the lamp is within the glass” (Qur’an 24:35) acquires a dual significance. It conveys not only the containment of light but also its modulation through a medium that is locally structured yet globally non-oriented. The glass thus functions as both a physical analogy and a conceptual model of an ontological interface—transparent enough to transmit illumination, yet structured enough to shape its manifestation (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019).

The metaphor of

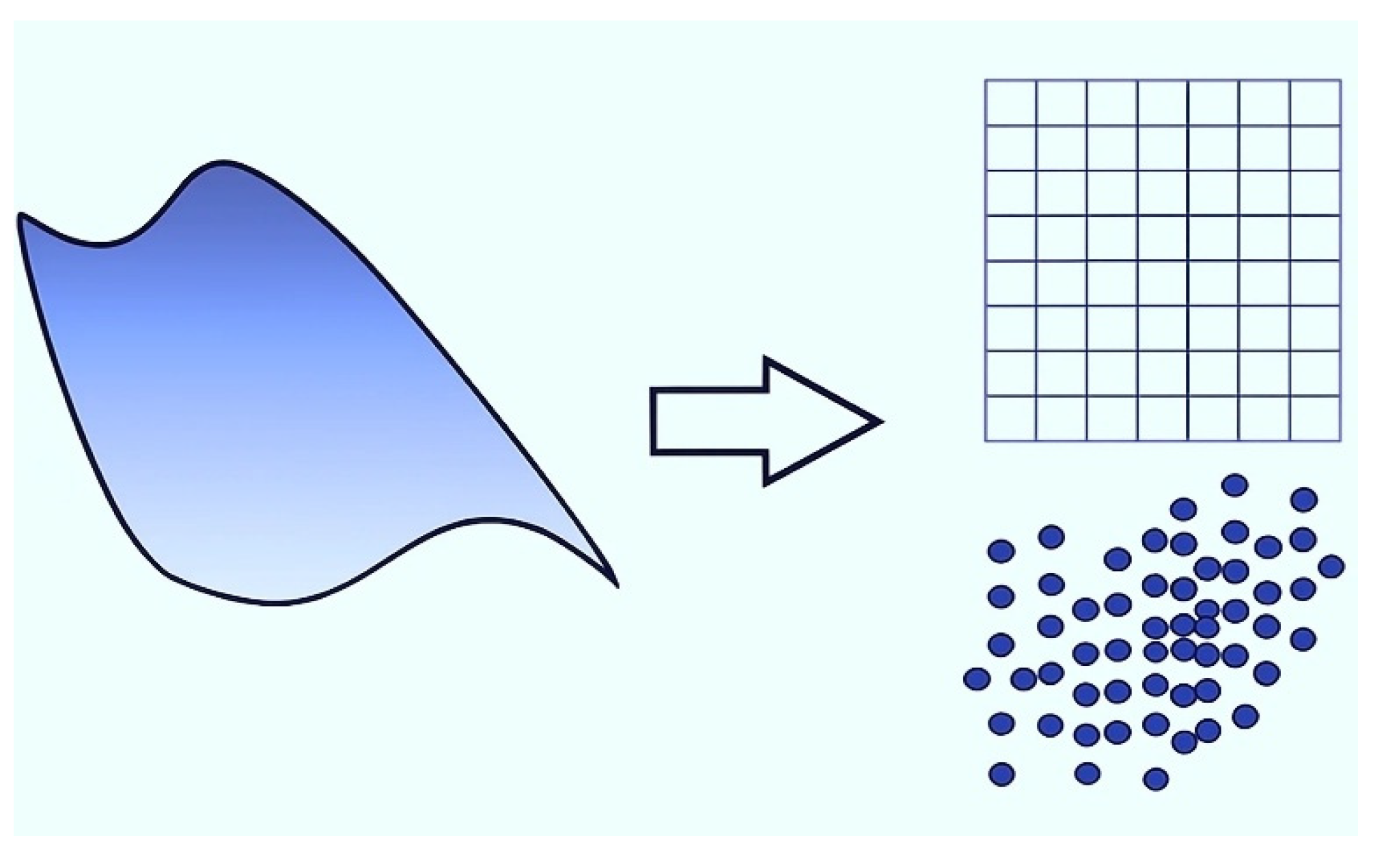

“a tree neither of the East nor the West” further reinforces a vision of primordial order unbound by spatial coordinates. Its directionlessness evokes an isotropic state—one in which no axis is privileged—and simultaneously suggests a metaphysical substratum prior to differentiation. Modern physical theories offer a useful parallel: LQG’s spin networks exhibit precisely such coordinate-free order, defined not by spatial position but by patterns of connectivity. In this sense, the Qurʾānic tree resonates structurally with relational conceptions of space, as depicted earlier in Figure 6-2 and echoed in the network-like forms shown in

Figure 6-4 (Quṭb, 2003; Pais, 2005; Barrau & Rovelli, 2014).

Figure 6-4.

Transition from the classical Cartesian lattice to a discrete relational network (visual analogy). The

illustration shows how continuous space is first idealized as a Cartesian grid and then reinterpreted as a distribution

of discrete nodes—highlighting a shift from coordinate‐based representation to relational structures in quantum

gravity (e.g., node–edge spin networks in Loop Quantum Gravity). Analogical reading; no identity claim.

Figure 6-4.

Transition from the classical Cartesian lattice to a discrete relational network (visual analogy). The

illustration shows how continuous space is first idealized as a Cartesian grid and then reinterpreted as a distribution

of discrete nodes—highlighting a shift from coordinate‐based representation to relational structures in quantum

gravity (e.g., node–edge spin networks in Loop Quantum Gravity). Analogical reading; no identity claim.

For this reason, contemporary physicists such as Rovelli and Smolin moved decisively away from grid-based metaphors of space inherited from classical physics. Drawing on Einstein’s dynamic conception of spacetime, they developed non-linear, relational, and background-independent models. The spin-network framework abandons fixed background coordinates, articulating instead a relational and topologically organized structure with no privileged directions. Accordingly, the analogies between these physical theories and the Qurʾānic metaphors of glass and tree are not merely literary; they constitute a formally resonant mapping of how being acquires structure (Rovelli, 2010; Smolin, 2019; Chirco, 2019).

In this chapter, the images of zujāja (glass) and the “blessed tree neither of the East nor the West” reveal a vision of cosmic order operating through structuration and relational interweaving. These symbols represent—at both metaphysical and ontological-topological levels—the transition of being from non-directionality to orientation, from unity to multiplicity, and from potentiality to actuality. Yet these structural affinities also prepare the ground for a deeper question: What is the source of this order?

While modern physics accounts for processes such as symmetry breaking, phase transitions, vacuum potentials, and the emergence of spacetime through internal dynamics, the Qurʾān foregrounds

amr, the transcendent divine command (

kun fa-yakūn), as the ontological ground of creation. Thus, the relational networks, pre-symmetry states, and topological origins explored here naturally lead into

Section 7, which examines the analogical convergence between early-universe physics and Qurʾānic cosmogony.

7. Creation Theories in Physics: A Qur’anic Convergence

Modern cosmology traces the observable universe back to a hot, dense, and rapidly expanding initial state. Commonly referred to as the “Big Bang,” this event does not describe an explosion within pre-existing space but the expansion of space-time itself (Penrose, 2004). In this model, space, time, and matter arise from an extremely high-energy condition and evolve as the universe cools and differentiates. Although the Qurʾān does not articulate physical processes in scientific–technical terms, its language of creation consistently emphasizes sudden origination, principial beginning, and the immediacy of divine command. Rather than supplementing scientific models, these representations provide an ontological horizon within which physical accounts may be situated (Abdelnour, 2023).

7.1. The Limits of Iʿjāz: Compressing Meaning into a Single Dimension

The iʿjāz approach is restrictive because it collapses the Qurʾān’s symbolic complexity into a single physical referent. For example, the imagery of “pearls and coral emerge” in Sūrat al-Raḥmān (Qur’an 55:19–37) carries layered symbolic meanings—order, differentiation, and the inner texture of being—when interpreted within the sūrah’s thematic architecture. Yet iʿjāz-oriented readings commonly reduce this imagery to the physical phenomenon of “non-mixing waters.”

Such interpretations often rely on a form of lexical overloading, asking isolated words or phrases to bear specific scientific content that the broader Qurʾānic discourse neither requires nor sustains. By stretching individual terms beyond their semantic and literary horizon, they inadvertently narrow a symbolic field that is intentionally multidimensional.

In reality, Qurʾānic representations shift function across contexts; the same symbol may operate differently within legal, theological, cosmological, or moral registers. The Qurʾān’s symbolic language is therefore inherently plural, dynamic, and contextual. It resists compression into a single scientific phenomenon or any one-to-one correspondence. A responsible hermeneutic must preserve this polyvalence rather than restrict it. Similar concerns about reductionism and the overextension of Qurʾānic language into scientific domains have been highlighted in recent critiques of iʿjāz ʿilmī in the contemporary literature (Guessoum, 2008; Bigliardi, 2017).

7.2. Analogical Reading: The Qur’an’s Conceptual Map

This study adopts an analogical reading grounded in the premise that the Qurʾān articulates a holistic conceptual structure across ontological, cosmological, and epistemic levels. The relevant verses of Sūrat al-Raḥmān reveal a metaphysical layer emphasizing the relation between form and function. Their purpose is not to describe physical events literally, but to convey a broader framework concerning the order of existence.

Central to this framework is the principle in Sūrat al-Ḥadīd 57:4: “Wherever you are, He is with you.” This “being with” (maʿiyyah) denotes not spatial proximity but divine agency and continuous creation. Within this horizon, processes of interpretation and system-building unfold through ontological nearness rather than purely inferential distance.

Islamic thought does not restrict meaning to rational inference (istidlāl). Analogy (qiyās), structural correspondence, pattern-recognition, and symbolic representation form essential components of its epistemic structure. Thus, Qurʾānic representations do not override scientific explanations; instead, they offer an alternative order of knowledge that operates beyond empirical description while remaining structurally resonant with non-reductive scientific models (Chittick, 1998; Nasr, 2001).

7.3.“. He Says ‘Be,’ and It Is”: Divine Command and the Ontological Ground of Physical Processes

The expression “He says ‘Be,’ and it is” (Qur’an 2:117; 3:47; 36:82), central to the Qurʾān’s doctrine of creation, affirms that existence originates directly from divine will, independently of sequential causal chains. Secondary causes are not negated but positioned as derivative manifestations of transcendent command (amr). Grounding creation in amr places ontological priority not in temporal succession but in the primacy of will and agency.

In modern physics, spontaneous symmetry breaking illustrates how differentiation can emerge from an initially uniform state through internal Dynamics (Smolin, 2019; Greene, 2004). Viewed metaphorically, this process offers a structural analogue for amr: just as symmetry breaking yields the distinct interactions of the early universe, divine command signifies that multiplicity and becoming arise from a primordial determining source. Thus, the Qurʾānic perspective does not deny physical causality; rather, it situates physical causality within a deeper ontological grounding.

Smolin’s account of time in quantum gravity sharpens this parallel. Basic constituents of the universe—spin networks, nodes, and relational structures—exhibit both discrete and processual features. Space and time emerge not as fixed backgrounds but as products of evolving relational dynamics. In this view, “time is real and fundamental,” whereas space arises from the evolution of relational structures (Smolin, 2001, 2019).

From this vantage point, conceiving space and time as two interpenetrating “currents” provides a useful analogical framework. When distinct flows meet, new patterns arise—much as convection cells form when waters of different temperatures interact. These fractal motifs conceptually recall the Qurʾānic imagery of “pearls and coral” arising from the encounter of “two seas” separated by a barzakh (Qur’an 55:19–37). The physical patterns are not direct counterparts to the Qurʾānic symbols, but they illuminate how the convergence of distinct media can yield new forms and layers of meaning.

A similar dynamic characterizes the macro-cosmos. Human experience unfolds within the interplay of two fundamental “seas”: the gravitational field and the electromagnetic field. Motion, balance, and form emerge from the combined impact of these two fields. At the atomic scale, short-range nuclear forces generate “coral-like” clusters and fractal structures. Just as coral reefs arise through collective biological organization, stable subatomic configurations emerge through the interplay of multiple interacting forces.

This framework clarifies the metaphysical orientation of Qurʾānic symbolism: existence arises through the convergence of flows and interactions across multiple levels of reality. This corresponds to continuous becoming—physically in modern cosmology and ontologically through divine command. Although Qurʾānic and scientific accounts operate within distinct epistemic domains, they exhibit structural resonance in their emphasis on becoming, differentiation, and emergence.

7.4. Real Time and Ontological Order: Smolin and al-Ghazālī

The status of real time is a decisive ontological question at the center of both contemporary physics and Islamic metaphysics. For Lee Smolin, time is fundamental to the universe: it is more basic than space and more primordial than any allegedly timeless laws. The universe is not a frozen instantiation of fixed mathematical equations, but a genuinely historical process in which new structures and even new laws can emerge (Smolin, 2019; Cortês & Smolin, 2019, al-Ghazālī, 1997). Time is therefore not merely a measure of change; it is the very condition of ontological productivity.

Al-Ghazālī, by contrast, does not treat time as an intrinsic property of beings. In line with the doctrine of tajdīd al-khalq—constant re-creation—time is understood as the ordered sequence of divine acts (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; 1997; Griffel, 2009). For him, time is a relational order that arises when created entities acquire succession; continuity consists in the regular flow of these successive divine acts. Time is thus not an independent background, but the very articulation of appearance, manifestation, and ordering.

At the ontological level, the two orientations diverge:

Nevertheless, both models converge on three basic functions of time: it provides an ordering condition for intelligibility, a directionality for causality, and a field for agency. In both perspectives, the universe is not a collection of inert substances but a constantly rearticulated web of relations. Smolin’s emphasis on “real time” and al-Ghazālī’s account of tajdīd al-khalq thus meet in a shared intuition: reality becomes determinate in and through time (For a discussion that presents strong critiques of physics from mathematical and philosophical perspectives on this matter, see Dolev (2024)).

7.5. Dynamic Balance (Mīzān): Cosmological Order and Moral Principle

In physics, equilibrium signifies not static rest but continuously reestablished responsiveness to disturbance. In Newtonian mechanics, perturbations generate acceleration, requiring ongoing adjustment (Newton, 1687/1846). Prigogine and Stengers (1984) likewise describe the universe as a dynamically self-organizing system—an insight anticipated in early secular reflections linking entropy to normative concepts (Lindsay, 1959, pp. 383–384; Massoudi, 2016).

This dynamic structure parallels the Qurʾānic portrayal of apparent solidity masking constant transformation:

“You see the mountains, thinking them solid, yet they pass away like clouds.” (Qur’an 27:88)

Smolin’s evolving-cosmos model reinforces this vision by proposing that even cosmological constants may vary across cosmic history (Smolin, 2001, 2019). Within the Qurʾān, this dynamic cosmic order is expressed through mīzān, which carries a moral correlate: “Do not transgress in the balance” (Qur’an 55:8). Thus, the same order structuring the cosmos establishes human ethical responsibility (Moosa, 2005; Nasr, 2001; Ben-Naim, 2020).

7.6. Nūr and the Transcendent Ground: Beyond Physical Models

Smolin’s methodological stance seeks to account for the universe through internal dynamics alone, without appealing to transcendent causes (Smolin, 2019). The Qurʾānic framework instead situates reality within a dual structure: immanent laws and transcendent amr. Thus, while physics describes internal dynamics, the Qurʾān gestures to the ontological ground that renders those dynamics possible.

In Qurʾān 24:35, Nūr is not physical luminosity but the metaphysical condition that enables existence, manifestation, and intelligibility. It stands outside physical space and time. Even the discrete network structures of Loop Quantum Gravity remain internal to creation and therefore cannot fulfill the role attributed to Nūr (Rovelli, 2010; Chirco, 2019).

Debates in fundamental physics nevertheless provide conceptual resources. Bohmian mechanics posits a deeper ontological substrate guiding measurable phenomena, exhibiting structural affinity with the Qurʾānic notion of a transcendent ground (Einstein, 1960). The quantum measurement problem offers another parallel: the observer is part of the system. From a Qurʾānic perspective, Nūr is not an observer but the ground enabling both observer and observed (Chittick, 1998). Thus, no physical model can occupy the ontological position of Nūr.

7.7. Conclusion: The Ontological Convergence of Qur’an and Cosmology

Despite operating in distinct registers, Qurʾānic representations of creation and modern cosmology share significant structural resonances. Both portray the cosmos as a dynamic, intelligible, and ordered process governed by principles. The Qurʾānic worldview frames this order as a moral trust; physics understands it as an emergent, self-organizing whole. Together, they sustain the possibility of viewing the universe as a coherent and meaningful totality.

Structural analogy claims no universal explanatory authority. Like a key shaped for a particular lock, it illuminates only those structures attuned to its form. Applied appropriately, it enhances metaphysical reflection and contemplative engagement. Islamic intellectual history demonstrates a rich methodological plurality—kalām, tafsīr, Sufism, falsafah, fiqh—each with distinct modes of reasoning yet rooted in the same textual foundation. This plurality forms a unity-in-diversity akin to the harmonious complexity of a coral reef.

Structural analogy thus occupies the moderate path emphasized by al-Ghazālī, avoiding both literalism and unrestrained allegorization. It neither reduces revelation to scientific discourse nor elevates science as a hermeneutical arbiter. Instead, it preserves methodological autonomy while revealing patterned similarities that make conceptual dialogue possible.

The method sharpens intellectual discernment by training the mind to perceive relations, structures, and patterns—capacities foundational to both classical Islamic scholarship and contemporary scientific reasoning. A broader exegetical corpus would likely confirm an even more coherent representational order, suggesting that the Qurʾān’s symbolic mode of describing the world structurally mirrors foundational patterns in the natural order.

Thus, structural analogy emerges as a productive method for interpreting both the cosmos and the layered meanings of the sacred text. It preserves the coherence of revelation, reason, and nature, allowing their shared intuitions—order, emergence, unity-in-multiplicity, and balance—to illuminate one another without collapsing into equivalence.

8. The Concept of Shayʾ and the Ontology of Non-Being

One of the central ontological questions shared by classical kalām and contemporary theoretical physics is the inquiry, “What is a thing?” (mā huwa al-shayʾ). In the Qurʾān, shayʾ is linked not merely to physical entities but to intelligible modes of being that are knowable, nameable, and subject to divine address—“God is powerful over all things” (Qur’an 2:284). Classical Islamic metaphysicians such as al-Ghazālī and later commentators emphasize that “thingness” (shayʾiyyah) does not refer to a fixed essence; rather, a thing is what stands in an intelligible relation grounded in divine will, knowledge, and orientation (Izutsu, 2002; Chittick, 1998; Abdelnour, 2023).

At a structural level, this relational conception of being resonates with modern physics, where entities are defined less by intrinsic substance and more by interactions, processes, and relational configurations—whether in quantum mechanics, quantum gravity, or cosmology (Smolin, 2019; Rovelli, 2018).

8.1. Defining Shayʾ in Islamic Ontology

One of the fundamental ontological questions shared by classical kalām and contemporary In classical Islamic metaphysics, al-shayʾ denotes any possible existent (mumkin al-wujūd)—that is, anything whose existence is neither necessary (wājib al-wujūd) nor impossible (mumtaniʿ al-wujūd), but capable of attaining actuality through a specific cause (ʿilla) or divine command (amr). The Qurʾān’s affirmation that God possesses knowledge of “all things” (ʿilm kulli shayʾ) (Qur’an 72:28) makes clear that shayʾ encompasses more than presently existing entities. It includes the full spectrum of possibles: beings not yet actualized, contingencies that may or may not come to be, and determinate quiddities known to God prior to their manifestation (Izutsu, 2002; Chittick, 1998; Barlak, 2020).

Ashʿarite theologians such as al-Ashʿarī and al-Ghazālī therefore define thingness (shayʾiyyah) relationally rather than essentially. A “thing” is not a substance possessing inherent reality; it is that which stands in a possible relation to divine knowledge, address, and actualization. Its determinability—its capacity to be known, commanded, or brought forth—constitutes its ontological status. Thus, shayʾ marks the threshold at which a quiddity becomes intelligible within the scope of divine omniscience (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019).

A significant nuance within Qurʾānic usage is that the term shayʾ is at times applied to God (Qur’an 6:19). Classical interpreters are unanimous that this does not render the Divine a “thing” among things, nor does it place God within the ontological category of created beings. Rather, it expands the semantic field of shayʾ by anchoring its highest and truest measure in the Necessary Being. The Divine is “a thing” only in the sense of being the incomparable referent against which all determinate being is measured—not because the Divine essence is encompassed by the category (Moosa, 2005; al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019).

Accordingly, the range of shayʾ extends from the possible existent to the Necessary Real, while preserving the absolute qualitative difference between Creator and creation. This avoids both anthropomorphic reduction and metaphysical nominalism: shayʾ becomes a category of intelligibility grounded in divine knowledge, and contingency becomes a function of relation rather than intrinsic essence.

8.2. Reconsidering ʿAdam (Non-Being)

Within this relational ontology, ʿadam (non-being) must be interpreted with care. Islamic metaphysics does not equate ʿadam with absolute nothingness. Rather, it designates the absence of actualized relation to divine will—existence not yet called forth into actuality. Nothing attains ḥaqīqah without amr.

Classical debates—particularly between the Muʿtazila and the Ashʿarites—revolved around whether the maʿdūm (non-existent) possesses quiddity (māhiyyah) prior to creation. Many theologians affirmed that the non-existent is fully encompassed by divine knowledge and possesses definable quiddity (māhiyyah thābita) even before it is actualized (Doko, 2024; Barlak, 2020; Wolfson, 1976). Thus, ʿadam is not a metaphysical void but a relational possibility awaiting manifestation through amr.

8.3. Parallels in Modern Physics

Modern physics also reconfigures the meaning of “nothingness.” In quantum field theory, the vacuum is not an empty void but the lowest-energy configuration of a field—dynamic, fluctuation-rich, and charged with latent potential (Heisenberg, 1958; Zee, 2010; Krauss, 2012). Zero-point energy, virtual particles, entanglement structures, and vacuum fluctuations reveal a vacuum that is physically active (Hawking & Penrose, 1996; Krauss, 2012)

vii. Phenomena such as the Casimir effect and Hawking radiation empirically demonstrate that the vacuum participates in causal dynamics.

The structural parallel is conceptual rather than empirical:

potential → relation → manifestation

Just as the quantum vacuum contains latent dynamism awaiting perturbation, ʿadam in Islamic ontology is relational potential awaiting divine command. Markopoulou’s (2012) “pre-geometric” domain in quantum gravity similarly treats spacetime as emerging from a deeper layer of dynamic possibility. Loop Quantum Gravity models spacetime as a network of relations—spin networks—rather than as a fixed stage (Rovelli, 2010).

Metaphysically, these relational models echo Nasr’s insistence that ʿadam is not absolute void but a mode of potentiality grounded in divine omniscience and awaiting activation (Nasr, 1987; Dyke, 2023).

Yet the analogy remains strictly structural:

the quantum vacuum is immanent, governed by physical laws;

ʿadam is transcendentally grounded, defined by relation to amr.

8.4. Relational Ontology and the Role of Nūr

Placed within this relational frame, a profound structural affinity emerges between the Qurʾānic notion of shayʾ and modern relational ontologies. Being is not a static, self-subsistent substance but a relational event. A being becomes a shayʾ when it becomes intelligible—knowable, addressable, or open to actualization. Conversely, ʿadam is not sheer nothingness but the absence of relation, conceptually akin to unentangled or uncorrelated quantum states that lack determinate properties prior to interaction.

Within this ontological architecture, nūr in Qurʾān 24:35 assumes decisive metaphysical significance. Nūr is not merely the illumination of pre-existing entities; it is the precondition for determinability itself. Without nūr, nothing could qualify as a shayʾ, because nothing could be known, distinguished, or addressed.

In Mishkāt al-Anwār, al-Ghazālī presents nūr as the principle of manifestation that bridges the Divine and creation al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019). Nūr therefore functions as the ontological threshold through which relational potential becomes intelligible being.

A conceptual parallel—strictly analogical—appears in physics: observability and interaction are mediated through photons. A phenomenon becomes accessible only through coupling, measurement, or information-bearing interaction. Although the ontological assumptions differ entirely, both frameworks rely on the triad:

emergence → relation → intelligibility

This structural parallel indicates that intelligibility always requires a mediating ground—Nūr at the metaphysical level, dynamic interaction at the physical level, and virtual-particle interactions at the quantum level.

8.5. Conclusion

This relational reconstruction of shayʾ and ʿadam reveals a unified ontological vision structured by potentiality, relation, and manifestation. In both Islamic metaphysics and modern physics:

being emerges through relations,

intelligibility requires mediation,

actuality presupposes structured potential,

and determinacy is not intrinsic but relationally conferred.

Yet a decisive distinction remains: whereas modern physics operates entirely within immanent causal structures, Islamic metaphysics posits amr as a transcendent source that activates potentials and brings relational possibilities into actuality.

The parallels identified here do not collapse theology into physics or physics into theology. Instead, they disclose shared structural intuitions across distinct epistemic domains, opening fertile ground for deeper philosophical and theological reflection.

9. Conclusion: Layered Ontology, Structural Resonance, and the Limits of Cross-Domain Dialogue

This study set out to examine how the Qurʾān’s symbolic cosmology—most explicitly articulated in the Verse of Light (Qur’an 24:35)—may enter into a disciplined conceptual dialogue with contemporary approaches in fundamental physics without collapsing their distinct epistemic registers. The guiding premise was that structural analogy, when carefully delimited, can illuminate shared patterns of intelligibility across domains that otherwise remain methodologically autonomous. The analyses developed throughout the article confirm this premise: while theology and physics operate on different ontological strata, each articulates a universe structured by potential, relation, and ordered manifestation.

The Qurʾānic metaphysics of Nūr, as elaborated by al-Ghazālī, frames existence not as self-subsisting substance but as a dynamic order grounded in a transcendent command (amr) (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; Griffel, 2009). The symbols of niche, glass, tree, oil, and layered light collectively express a graded ontology in which emergence is inseparable from orientation, mediation, and metaphysical grounding. Contemporary relational physics—through symmetry breaking, quantum fields, emergent structures, and the primacy of real time—likewise portrays the universe as an evolving network of dynamic processes rather than static entities. The structural parallels traced here do not imply equivalence; instead, they reveal a shared grammar of potential → relation → manifestation that underlies both modes of discourse.

A central insight emerging from the comparison is the role of time. For Smolin, time is real and fundamental; the universe develops through genuine novelty, and its laws may themselves have a history. For al-Ghazālī, time is the ordered succession of divine acts, renewed at every moment through tajdīd al-khalq (al-Ghazālī, 1924; 1998; 2019; 1997; Griffel, 2009). Although these frameworks diverge ontologically—one immanent, the other transcendent—they converge structurally in treating time as the condition through which intelligibility, agency, and becoming unfold. In both perspectives, reality is not static but continuously articulated through relational processes grounded in principled order.

The discussion of non-being further reinforces this convergence. In classical Islamic metaphysics, ʿadam denotes a state of determinability awaiting activation by divine will (Chittick, 1998; Nasr, 1987). In quantum field theory, the vacuum is not an empty void but a reservoir of latent potential—fluctuations, zero-point energies, and virtual excitations (Heisenberg, 1958; Zee, 2010; Krauss, 2012). While metaphysically distinct, these notions share an intuition that “nothingness” is structured, patterned, and generative. Such parallels exemplify the purpose of structural analogy: to reveal conceptual affinities at the level of form, without suggesting empirical confirmation or theological equivalence.

In shaping the final form of this article, a detailed analysis of debates on atomism and ontological discreteness has been deliberately left outside its scope. This decision does not reflect a view that these themes are secondary; rather, their technical density, historical complexity, and conceptual depth warrant a dedicated treatment of their own. A comprehensive examination of the relationships between classical kalām atomism, al-Ghazālī’s metaphysical framework, and modern discussions of discreteness in quantum gravity would substantially expand the article and shift its thematic focus. For this reason, these issues have been deferred to a forthcoming companion piece, where they can be addressed with the requisite level of detail and methodological rigor. This choice allows the present study to maintain its emphasis on relational ontology, symbolic cosmology, and the metaphysics of Nūr.

Ultimately, the significance of this study lies not in proposing a synthesis between scripture and science, but in demonstrating that both domains, when read through their own internal principles, converge on a shared conviction: reality is intelligible because it is ordered. The Qurʾān articulates this order through symbolic metaphysics grounded in nūr and amr; physics articulates it through dynamical laws, relational structures, and emergent patterns. Recognizing this structural resonance does not blur epistemic boundaries; rather, it clarifies why multiple modes of knowing—revelatory, philosophical, and empirical—can jointly contribute to a coherent understanding of existence.

In light of these reflections, structural analogy emerges not as a reductive method, but as a disciplined mode of inquiry that preserves the integrity of each epistemic domain while making visible the patterned similarities between them. When the Qurʾān’s symbolic language is placed alongside the conceptual tools of contemporary cosmology, it becomes apparent that both frameworks portray a universe characterized by order, continuity, emergence, unity-in-multiplicity, and dynamic balance (Nasr, 2001; Moosa, 2005). This does not establish identity across levels, but opens a shared horizon of reflection—one that future work will extend by examining the ontology of discreteness, multiplicity, and the dynamics of becoming in greater detail. Real time may be conceived not merely as a passive dimension of human experience, but as a temporality that emerges through acts of ontological orientation and choice.

Author Contributions

The author is the sole contributor to this research and manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. All costs were covered by the author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

| i |

Structural analogy does not dismiss the literal or devotional meanings traditionally associated with the verse. Rather, it presupposes the literal layer as the primary semantic ground and focuses on the relational patterns formed by the symbols (niche, lamp, glass, oil, layered light). In this sense, the method intentionally brackets ontological equivalence claims and directs attention to functional mediation, graded structure, and symbolic interaction. |

| ii |

The ẓuhūr doctrine referred to here took on a systematic metaphysical form especially after Ibn ʿArabī, and denotes the manifestation of the divine Reality as it becomes visible through different levels of being. This approach departs from the necessary efflux model of the ṣudūr (emanation) theory by placing at its centre the multi-layered self-disclosure of existence; it also differs in aim from the kümūn–ẓuhūr (latency–manifestation) scheme in kalām, which describes the actualization of what is latent. In Mishkāt al-Anwār, al-Ghazālī interprets existence as the gradual emergence of lights, thereby offering an original ontological framework that—without implying any direct historical influence—exhibits a structural affinity with the later Ibn ʿArabīan notion of graded divine self-disclosure (marātib al-tajallī). |

| iii |

Schrödinger’s concept of “negative entropy” (negentropy) emphasizes that the maintenance of order in living systems does not arise from an internal mechanism that directly reduces entropy, but rather from an inflow of low-entropy energy from the environment (Schrödinger, 1944). Prigogine’s later theory of dissipative structures brings this intuition into harmony with the second law of thermodynamics, showing that open systems, under continuous energy flow, can generate local order and increase in complexity (Prigogine & Stengers, 1984). In this way, Prigogine provides a physical grounding for Schrödinger’s notion of negentropy as an explanation of biological order within the framework of nonequilibrium thermodynamics. Ultimately, ordered systems sustain their internal organization by consuming low-entropy energy sources while producing a greater increase of entropy in their surroundings, thereby satisfying the condition of total entropy increase (ΔStotal>0) required for their continued existence. |

| iv |

“You now know that Light is summed up in appearing and manifesting, and you have ascertained the various gradations of the same. You must further know that there is no darkness so intense as the darkness of Not-being. For a dark thing is called “dark” simply because it cannot appear to anyone’s vision; it never comes to exist for sight, though it does exist in itself. But that which has no existence for others nor for itself is assuredly the very extreme of darkness.

In contrast with it is Being, which is, therefore, Light; for unless a thing is manifest in itself, it is not manifest to others. Moreover, Being is itself divided into that which has being in itself, and that which derives its being from not-itself. The being of this latter is borrowed, having no existence by itself. Nay, if it is regarded in and by itself, it is pure not-being. Whatever being it has is due to its relation to a not-itself; and this is not real being at all, as you learned from my parable of the Rich and the Borrowed Garment. Therefore, Real Being is Allah most High, even as Real Light is likewise Allah.” (al-Ghazālī, 1924, pp. 102–103)

|

| v |

Is evolution a directional process? History indeed shows a general trend toward greater complexity, responsiveness, and awareness. The capacity of organisms to gather, store, and process information has increased. However, when viewed locally and over shorter periods there seem to be many directions of change rather than a uniform stream. Short-term opportunism fills temporarily unoccupied ecological niches, which may turn out to be blind alleys when conditions change. |

| vi |

The idea that nothing can come into existence unless it is encompassed by God is a principle that has settled in me almost naturally since childhood. Moreover, it is one of the most common intuitions of tawḥīd, sincerely affirmed even by people whose level of religious observance is quite low. The Qur’ānic basis of this conviction is the verse, ‘To God belongs whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth, and God is encompassing of all things’ (Qur’ān 4:126). Al-Muḥīṭ is among the divine names, indicating that God surrounds all things by His knowledge, power, and protective encompassment, allowing nothing to scatter, dissolve, or acquire an independent domain of existence. Nevertheless, Qur’ān 4:126 does not explain how this encompassment is, that is, what its ontological nature consists in. The trace of this question can be pursued in Qur’ān 24:35, the Verse of Light, which articulates the nature of existence through a symbolic-ontological language. |

| viii |

Krauss emphasizes that, thanks to QED corrections, measurements of the hydrogen spectrum can be matched at the level of “about 1 part in a billion” (Krauss 2012, 83–84). He takes this accuracy as evidence for the reality of virtual particles—a reading that may be misleading. In standard quantum field theory (QFT), virtual particles are not on-shell quanta but internal, off-shell propagators—i.e., computational intermediates; energy–momentum is conserved at each interaction vertex. Heuristic talk of “borrowing energy” reflects time–energy uncertainty and does not entail any literal suspension of conservation laws. Krauss himself gestures toward this limitation elsewhere: “Quantum systems can misbehave for only so long… If the state… requires sneaking some energy from empty space, then the system has to return that energy in a time short enough…” (Krauss 2012, 155–156). In this article, we use virtual in this operational/calculational sense. |

References

- Abdelnour, M. G. (2023). The Qurʾān and the future of Islamic analytic theology. Religions, 14(4), 556. [CrossRef]

- Aykol, M., Merchant, A., Batzner, S., Wei, J. N., & Çubuk, E. (2024). Predicting emergence of crystals from amorphous precursors with deep learning potentials. Nature Computational Science. [CrossRef]

- al-Ghazālī. (1924). Mishkāt al-Anwār (The Niche for Lights) (W. H. T. Gairdner, Trans.). Church Missionary Society.

- al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid. 1998. The Niche of Lights (Mishkāt al-anwār). Translated by David Buchman. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

- al-Ghazālī. (1997). The incoherence of the philosophers (M. E. Marmura, Trans.). Brigham Young University Press.

- al-Ghazālī. (2019). Mişkâtü’l-Envâr (Varlık–Bilgi–Hakikat) (M. Kaya, Trans.). Klasik Yayınları.

- Barlak, M. (2020). Muʿtezile’de maʿdûm anlayışı: Ebû Reşîd en-Nîsâbûrî örneğinde bir inceleme [The concept of maʿdûm in Muʿtazila: A review on Abū Rashīd al-Nīsābūrī]. Eskiyeni, 41, 73–95. [CrossRef]

- Barrau, A., & Rovelli, C. (2014). Planck star phenomenology. Physics Letters B, 739, 405–409. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, A. (2020). Entropy, information, and Boltzmann’s world. Entropy, 22(4), 430. [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, S. (2017). The “scientific miracle of the Qur’ān”: Some methodological notes. Zygon, 52(1), 202–221. [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the implicate order. First published 1980 by Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Brooke, J. H. (1991). Science and religion: Some historical perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, S. M. (2019). Something deeply hidden: Quantum worlds and the emergence of spacetime. Dutton.

- Chirco, G. (2019). Holographic entanglement in group field theory. Universe, 5(10), 211. [CrossRef]

- Chittick, W. C. (1998). The self-disclosure of God: Principles of Ibn al-ʿArabī’s cosmology. State University of New York Press.

- Cortês, M., & Smolin, L. (2019). The universality of the quantum. Universe, 5(3), 84. [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, A. (1994). The physical theory of kalām: Atoms, space, and void in Basrian Muʿtazilī cosmology. E. J. Brill.

- Doko, E. (2024). Islamic theism and the multiverse: Reconciling faith and cosmology. Religions, 15(3), 245.

- Dyke, H. (2023). Time. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Dolev, Y. (2024). Temporal direction, intuitionism and physics. Entropy, 26(7), 594. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1960). Ideas and opinions. Fifth Printing, Crown Publishing Group.

- Fan, Z., & Ma, E. (2021). Predicting orientation-dependent plastic susceptibility from static structure in amorphous solids via deep learning. Nature Communications, 12, 1506.

- French, S. (2014). The structure of the world: Metaphysics and representation. Oxford University Press.

- Greene, B. (2004). The fabric of the cosmos: Space, time, and the texture of reality. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Griffel, F. (2009). Al-Ghazali’s philosophical theology. Oxford University Press.

-

Guessoum, N. (2008). The Qur’an, science, and the (related) contemporary Muslim discourse. Zygon, 43(2), 411–438. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W., & Penrose, R. (1996). The nature of space and time. Princeton University Press.

- Heisenberg, W. (1958). Physics and philosophy: The revolution in modern science (World Perspectives series). George Allen & Unwin.

- Horn, B. (2020). The Higgs field and early universe cosmology: A (brief) review. Physics, 2(3), 503–520. [CrossRef]

- Izutsu, T. (2002). God and man in the Qur’an: Semantics of the Qur’anic Weltanschauung. Islamic Book Trust. (Original work published 1964).

- Krauss, L. M. (2012). A universe from nothing: Why there is something rather than nothing (with an afterword by Richard Dawkins). Free Press.

- Ladyman, J., & Ross, D. (2007). Every thing must go: Metaphysics naturalized. Oxford University Press.

- Lakatos, I. (1970). Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes. In I. Lakatos & A. Musgrave (Eds.), Criticism and the growth of knowledge (pp. 91–195). Cambridge University Press.

- Lindsay, R. B. (1959). Entropy consumption and values in physical science. American Scientist, 47(3), 376–385.

- Malik, S. A. (2025). Science as divine signs: Al-Sanūsī’s framework of legal (sharʿī), nomic (ʿādī), and rational (ʿaqlī) judgements. Religions, 16(5), 549. [CrossRef]

- Markopoulou, F. (2012). The computing spacetime. https://arxiv.org/abs/1201.3398v1.

- Massoudi, M. (2016). A possible ethical imperative based on the entropy law. Entropy, 18(11), 389. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S. D. (2009). Complexity: A guided tour. Oxford University Press.

- Moosa, E. (2005). Ghazali and the poetics of imagination. University of North Carolina Press.

- Nasr, S. H. (Ed.). (1987). Islamic spirituality: Foundations (Vol. 19). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Nasr, S. H. (2001). Science and civilization in Islam. ABC International Group, Inc..

- Newton, I. (1846). The mathematical principles of natural philosophy (A. Motte, Trans.; First American ed., revised and corrected; with Newton’s System of the world and a life by N. W. Chittenden). Daniel Adee. (Original work published 1687).

- Pais, A. (2005). “Subtle is the Lord…”: The science and the life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press.

- Particle Data Group. (2024). Cosmic microwave background (Chap. 29). In Review of particle physics. https://pdg.lbl.gov/2024/reviews/rpp2024-rev-cosmic-microwave-background.pdf.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The road to reality: A complete guide to the laws of the universe. Vintage Books.

- Planck Collaboration. (2020). Planck 2018 results. VII. Isotropy and statistics of the CMB. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A7. [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. (2002). The logic of scientific discovery. Routledge.

- Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: Man’s new dialogue with nature. Bantam Books.

- Quṭb, S. (n.d.). In the shade of the Qur’ān: Fī ẓilāl al-Qur’ān. Islamic Foundation.

- Rovelli, C. (2010). Quantum gravity. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (2018). The order of time (E. Segre & S. Carnell, Trans.). Riverhead Books.

- Schrödinger, E. (1944). What is life? The physical aspect of the living cell. Cambridge University Press.

- Smolin, L. (2001). Three roads to quantum gravity. Basic Books.

- Smolin, L. (2019). Einstein’s unfinished revolution: The search for what lies beyond quantum physics. Penguin Press.

- van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (Clarendon Library of Logic and Philosophy).

- Wolfson, H. A. (1976). The philosophy of the Kalam. Harvard University Press.

- Wüthrich, C. (2020). One time, two times, or no time? doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2009.02965.

- Yang, Y., Zhou, J., Zhu, F., Yuan, Y., Chang, D. J., Kim, D. S., Pham, M., Rana, A, Tian, X., Yao, Y., Osher, S. J., Schmid, A. K., Hu, L., Ercius, P., & Miao, J. (2021). Determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of an amorphous solid. Nature, 592(7852), 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Zee, A. (2010). Quantum field theory in a nutshell (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Zorba, S. (2016). God is random: A novel argument for the existence of God. European Journal of Science and Theology, 12(1), 51–67.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).