1. Introduction

Because deep-sea polymetallic nodules are rich in critical minerals such as nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese, their exploitation has attracted significant international attention. Polymetallic nodules are potato-shaped and partially embedded in deep-sea sediments. During mining, a tracked collector travelling over the seafloor sediments collects the nodules through mechanical or hydraulic methods and transports them to a conveying pipeline, which then pumps them to the mining vessel at the surface[

1,

2]. For this reason, deep-sea polymetallic nodule collectors are also often referred to as deep-sea mining robots [

3]. To ensure thorough collection of nodules within the seabed mining area, the collector usually performs full-area traversal during operation, advancing in straight-line loops across the mining field, in a pattern analogous to that of a lawn-mowing operation [

4,

5]. Due to the length limitation of the flexible hose, the collector must turn back after traveling in a straight line for approximately 600 m on the seabed. At the same time, because both the bearing capacity and shear strength of seabed sediments are relatively low [

6,

7], the collector generally performs turning maneuvers along circular-arc paths with a relatively large turning radius during each reversal[

8,

9], to prevent slipping and sinkage [

10]. Before mining deep-sea polymetallic nodules, it is necessary to plan and design the collector’s travelling path and speed according to the above requirements. Depending on the relative arrangement of the turning arcs and the straight outbound–return lines, the planned paths are mainly classified into two types: the “keyhole type” [

11] and the “bulb type” [

12]. During polymetallic nodule mining operations, the collector is required to travel along the planned path; therefore, the collector’s travelling during operation is also a process of tracking and executing the planned path and speed.

As a key technology in deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining, considerable research has been conducted on path tracking for the operational travelling of collectors.

In terms of path tracking methods and strategies, Yoon et al. adopted a pure pursuit–based approach, in which preview points on the target path are continuously selected and updated, and the collector’s travelling speed and angular velocity are adjusted to approach the preview points, yielding good simulation and experimental results [

13]. Yeu et al. proposed a path-tracking algorithm for the collector to follow a predefined path using a vector tracking method [

14]. Mao et al., based on the principle of the Stanley method, proposed an algorithm that regulates the speed difference between the collector’s two tracks according to the heading deviation to perform target path tracking, and verified the feasibility of the method through simulations [

15].

More studies have focused on control algorithms for reducing the deviation between the collector and the desired path. Commonly used methods include fuzzy control, model predictive control (MPC), and sliding mode control (SMC), as well as combined applications of different control approaches. Regulating the vehicle’s angular velocity according to the heading angle deviation and path deviation between the vehicle body and the target path is a common method for path tracking of tracked vehicles, and the dual-input, single-output structure of conventional fuzzy controllers fits this characteristic well. Therefore, fuzzy control algorithms have been widely applied in studies on collector path tracking [

16,

17,

18]. To improve control accuracy, Li et al. adopted a variable-universe method in the design of the fuzzy controller [

17], while Dai et al. applied a fuzzy adaptive PID control method to directly compute the collector’s track velocities and velocity ratio [

18]. However, in the fuzzy PID controller designed by Mao for path tracking, the input variables were the heading angle deviation between the collector and the target path and its rate of change [

15]. Cao [

19] and Wu [

20] conducted MPC-based studies on path tracking for deep-sea collectors. After linearizing and discretizing the kinematic model of the tracked collector, they constructed a predictive model by selecting the prediction horizon according to the MPC approach, formulated a quadratic performance evaluation function, performed rolling optimization, and carried out error correction. Simulation analyses verified the effectiveness of the proposed algorithms. g Chen et al. combined SMC and MPC for the collector’s path tracking [

21]. First, a sliding-mode control law was designed to enable rapid convergence of trajectory tracking errors, and then MPC was used to perform predictive optimization of the control law. Simulation results show that this combined control method can not only improve path tracking accuracy but also suppress the chattering caused by using sliding-mode control alone.

Some studies have paid attention to issues such as track slippage during the collector’s travelling on seabed sediments, but most of them remain at the level of making corrections based on assumptions or estimations—for example, applying slip-ratio compensation to the computed track velocities [

16,

17], or limiting the collector’s maximum angular velocity [

15,

20]. Chen et al. proposed a path-tracking method that compensates for the collector’s longitudinal deviation. Based on the Stanley tracking principle, they used a PD control algorithm to correct the lateral deviation between the collector and the target path, while employing an unscented Kalman filter to estimate and compensate for longitudinal offsets caused by slippage and other factors. Simulation analysis demonstrated that this method can reduce longitudinal deviation and heading-angle deviation during path tracking [

22]. Qihang Chen et al. established a collector dynamic model that accounts for nonlinear slip and random resistance, and designed a path-tracking controller based on the deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm. Through simulation and experimental studies, they showed that stable and rapid path-tracking performance can be achieved under conditions closer to actual mining operations [

23].

Overall, considerable research has been conducted on path tracking for deep-sea collectors. Most of these studies are rooted in the foundations and developments of path-tracking research for land vehicles, verifying the feasibility of applying such methods to deep-sea collector path tracking, while also revealing issues that require further investigation. For example, regarding path-tracking methods, the pure pursuit method uses a circular-arc route to move toward preview points, which may provide smooth turning advantages when tracking straight-line paths [

11]; however, during collector operations, large-curvature turning along circular arcs is frequently required, making the selection of preview points inconvenient. The Stanley tracking method, on the other hand, was originally proposed for wheeled vehicles and is not suitable for direct application to tracked collectors. In terms of control algorithms for reducing path deviation, sliding-mode control may exhibit robustness to certain uncertain variations in the system (such as disturbances caused by track slippage), but the high-frequency switching required near the sliding surface may aggravate track slippage on the seabed and increase disturbance to the sediment [

24]. The model predictive control method improves path-tracking performance by predicting future states, but it relies heavily on the accuracy of the system model. The nonlinear characteristics of the collector’s travelling dynamics make the model and algorithm complex, which affects their practical engineering application. On the other hand, although phenomena such as track slippage during seabed travelling of collectors objectively exist [

25], current research on the interaction between tracks and seabed sediments remains immature. Slip coefficients adopted based on assumptions cannot represent the varying slippage conditions, and some established dynamic models cannot accurately reflect the mechanisms and patterns of slippage. Moreover, the algorithms are complex and computationally intensive, making them difficult to apply to the real-time control of deep-sea collectors.

From the existing literature, most of these studies focus solely on eliminating the deviation between the vehicle body and the target path, which falls under path tracking in vehicle motion-control research. However, during deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining operations, the collector must maintain a certain speed during straight-line travelling to ensure nodule production capacity [

26], while the travelling speed must be reduced during turning maneuvers to avoid slippage [

27]. Therefore, the operational travelling of deep-sea collectors must follow not only the planned path but also the planned speed, which constitutes trajectory tracking of the planned path. From the perspective of planned path characteristics, polymetallic nodules are generally located on deep-sea plains below 4 km. Although features such as trenches or seamounts may also be present, the slope of actual mining areas is generally less than 5%, and the collector’s travelling during operation is a planar motion. Regarding path characteristics, each outbound-and-return trip includes straight lines required by the traversal operation as well as turning arcs with large curvature. At the scale of the entire mining area, the collector travels repeatedly along the same planned path. In terms of travelling control, GPS information is not available in the deep sea, and collectors rely on acoustic and inertial navigation technologies for positioning and navigation. The controllers and actuators must also meet the requirements of the deep-sea environment. As a result, the application of some advanced trajectory-tracking methods and technologies used in land vehicles is constrained when applied to deep-sea collectors.

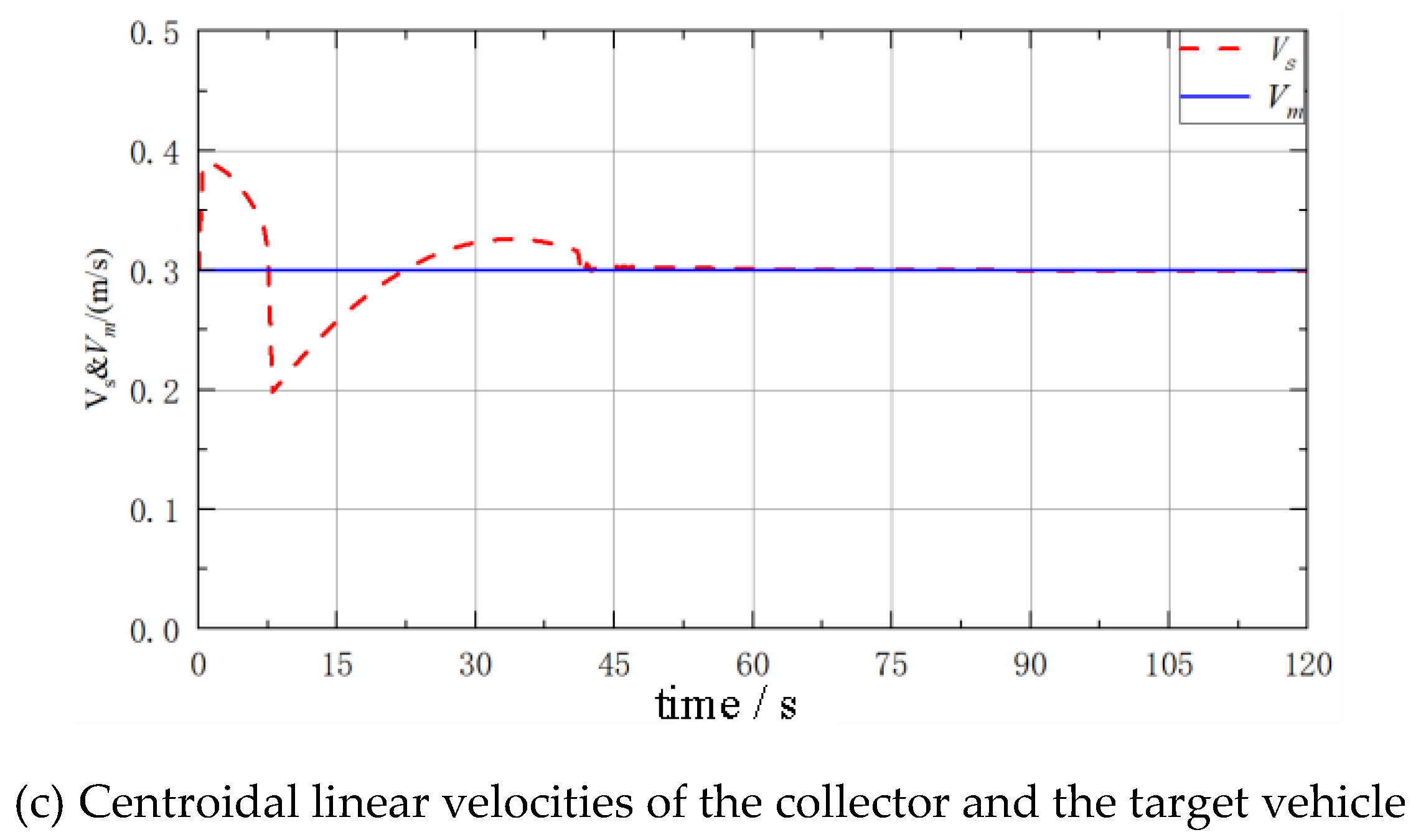

Based on the characteristics of the planned travelling path for collector mining operations and the operational conditions of the deep-sea environment, this paper proposes a trajectory-tracking method for the collector to follow the planned path and speed, using virtual target vehicle following. Fuzzy control and proportional control algorithms, which are convenient for engineering implementation, are employed to regulate the collector’s angular velocity and linear velocity, enabling the collector to travel according to the planned path and speed throughout the entire operation.

2. Trajectory-Tracking Scheme for Implementing the Planned Path Based on Virtual Target Vehicle Following

2.1. Trajectory-Tracking Method for the Planned Path Based on Virtual Target Vehicle Following

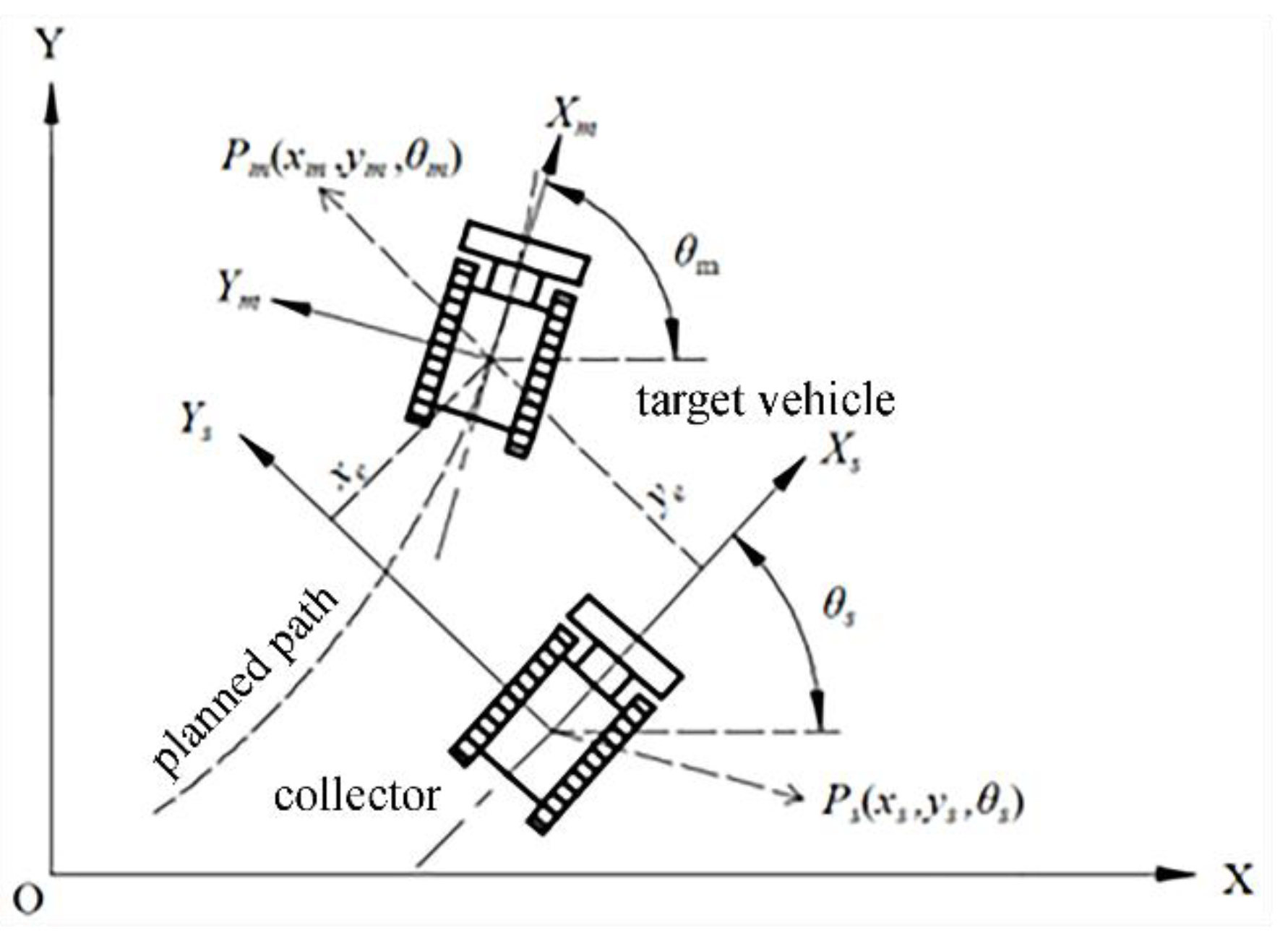

The pure pursuit method, the Stanley method, and the vector tracking method all belong to geometric approaches. They perform path tracking by gradually selecting preview points along the target path and moving toward those points. Their basic idea can be summarized as the so-called “carrot-chasing method”: moving a carrot slowly in front of an animal to induce it to move toward the carrot’s position. As a geometric approach, these tracking methods do not consider the moving speed of the carrot, and as a point, it has neither a heading angle nor an angular velocity. Clearly, for trajectory tracking of a large collector operating along complex paths that require frequent turning, such information is insufficient. To address this issue, a trajectory-tracking scheme for implementing the planned path based on virtual target vehicle following is proposed. In this scheme, on one hand, a virtual target vehicle with the same structure and performance characteristics as the collector is constructed. This virtual target vehicle travels according to the planned path and speed preset by the mining process, thereby forming the dynamic planned travelling path and speed of the collector’s operation. On the other hand, the collector minimizes its position and heading-angle deviations from the target vehicle by adjusting its own travelling speed and angular velocity according to the real-time deviations in position and heading angle between the two, thus achieving trajectory tracking of the planned path.

Figure 1 illustrates the trajectory-tracking method for the planned path based on virtual target vehicle following. In the figure,

Pm(

xm,

ym,

θm) and

Ps(

xs,

ys,

θs) represent the positions and heading angles of the target vehicle and the collector, respectively. Compared with geometric tracking methods, the trajectory of the target vehicle is not merely a sequence of preview points on the target path, but a planned path formed by continuously travelling along the preset path and speed. Furthermore, the collector’s tracking toward the target vehicle relies not only on the position deviation between the collector and the target path, but also on the heading-angle deviation between the collector and the target vehicle.

2.2. Kinematic Model of the Collector and the Virtual Target Vehicle

Since the virtual target vehicle is assumed to have the same structure and performance as the collector, they share the same kinematic model. The collector’s travelling on the seabed can be regarded as planar motion, and its kinematic model can be expressed as:

In the above equation, V0 denotes the linear velocity at the collector’s center of mass, ω0 denotes its angular velocity, and t represents time.

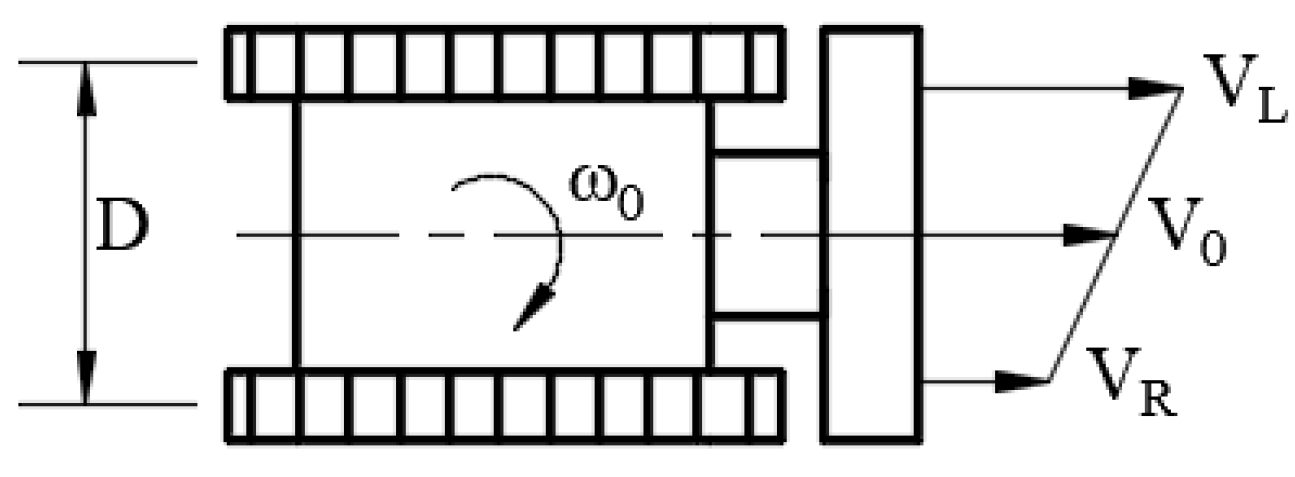

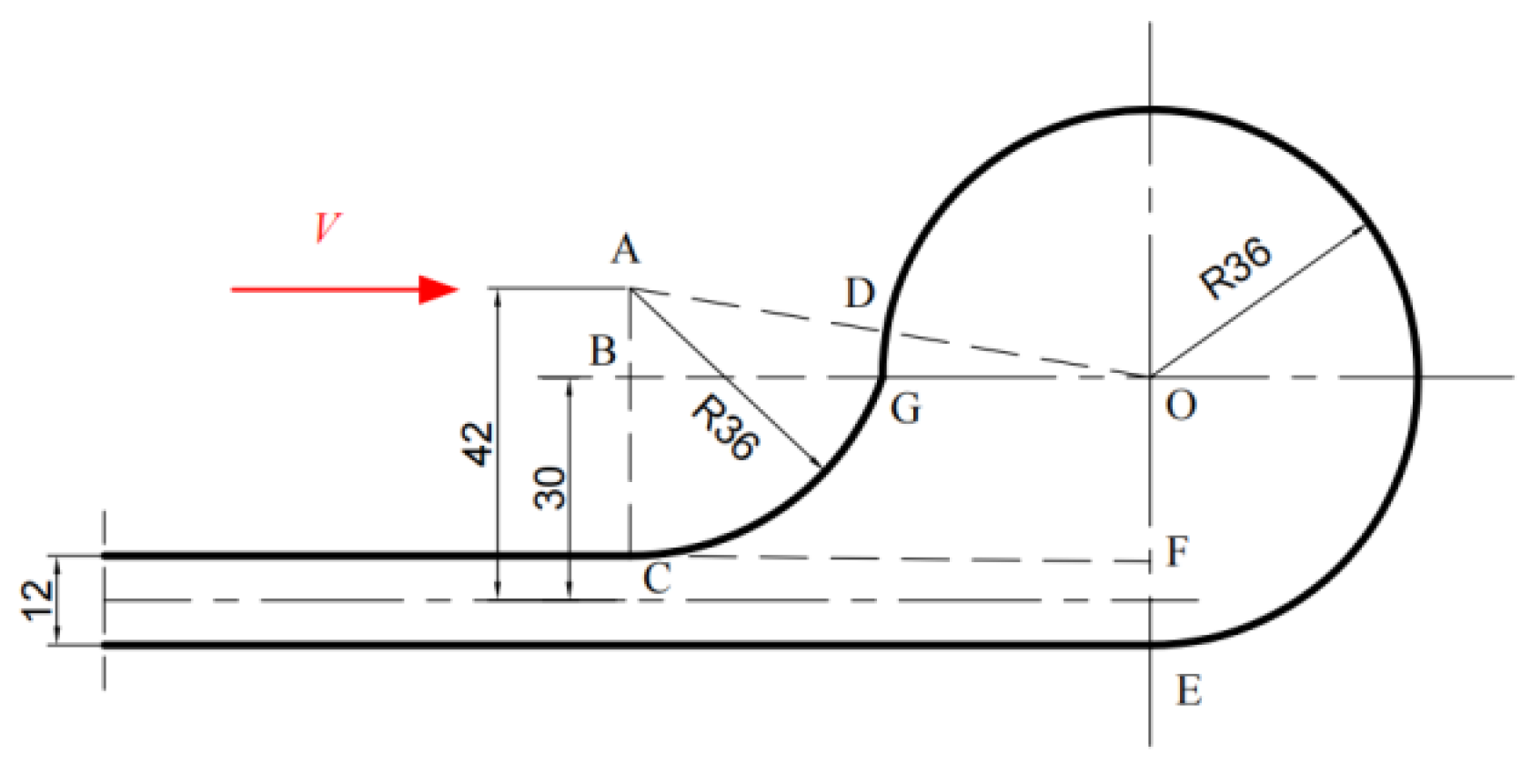

Both the collector and the target vehicle are tracked vehicles, whose straight-line travelling or turning is controlled by the speed difference between the left and right tracks. As shown in

Figure 2, and without considering slippage, the relationship among the center velocity

V0, angular velocity

ω0, and the left and right track speeds

VL and

VR is given by:

In the above equations, D is the distance between the centers of the two tracks. From (2) and (3), it can be seen that once the center velocity and angular velocity of the collector are determined, the travelling speeds of the left and right tracks are also determined. Therefore, in the motion control of the collector, its center velocity and angular velocity can be taken as the control variables.

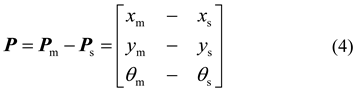

2.3. Pose Deviation Between the Collector and the Virtual Target Vehicle

In

Figure 1,

Ps(

xs,

ys,

θs) and

Pm(

xm,

ym,

θm) represent the positions and heading angles of the collector and the target vehicle in the geodetic coordinate system, respectively. Their position and heading-angle deviations can be expressed as:

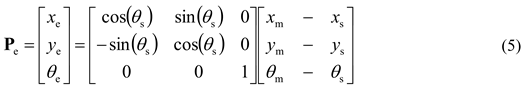

However, during trajectory tracking, since the onboard acoustic beacons, inertial navigation systems, side-scan sonars, controllers, hydraulic motors, and other actuators are all mounted on the collector, it is more convenient to make trajectory-tracking decisions and implement control from the collector’s perspective—namely, based on the position and heading-angle deviations between the collector and the target vehicle expressed in the collector’s body coordinate system. Therefore, the pose deviation between the collector and the target vehicle in the geodetic coordinate system must be transformed into the pose deviation between the two in the collector’s coordinate system. According to the transformation method of planar Cartesian coordinate systems, the position and heading-angle deviations between the collector and the target vehicle in the collector’s coordinate system can be expressed as:

where xe, ye and θe denote the position and heading-angle deviations between the collector and the target vehicle in the collector’s coordinate system.

2.4. Control Algorithms for Reducing Pose Deviation

In the tracking method proposed in this paper, the virtual target vehicle travels according to the planned path and speed. If tracking control enables the pose deviation between the collector and the virtual target vehicle to reach zero, trajectory tracking of the planned path is thereby achieved. According to Equation (5), the pose deviation consists of the longitudinal position deviation

xe, the lateral position deviation

ye, and the heading-angle deviation

θe. Although, in principle, these three deviations could be used as input variables to design a trajectory-tracking controller, such a controller would inevitably become complex. From

Figure 1, the lateral deviation

ye represents the distance between the collector and the planned path, while the heading-angle deviation

θe is the key factor for path correction. The planned path can be tracked based on these two deviations. The longitudinal deviation

xe represents the distance between the collector and the target vehicle along the direction of the planned path. If

xe remains zero, it indicates that the collector and the target vehicle are travelling at the same speed; therefore,

xe can be used to control the collector’s tracking of the planned speed. This approach—separately tracking the planned path and the planned speed—can substantially reduce the complexity of the controller.

Regarding control algorithms, although various approaches have been explored, limitations still exist when considering engineering applications in deep-sea mining operations. In comparison, the dual-input single-output structure of the conventional fuzzy controller is highly suitable for designing a controller that adjusts the collector’s angular velocity based on the lateral position deviation and heading-angle deviation. Moreover, this method directly computes control commands from the path and heading-angle deviations without relying on the dynamic model of the collector’s travelling, providing good operability and robustness. On the other hand, adjusting the collector’s travelling speed according to longitudinal position deviation is physically intuitive. From a control perspective, constructing a proportional controller that uses longitudinal position deviation as the input variable is not only simple but also efficient and practical.

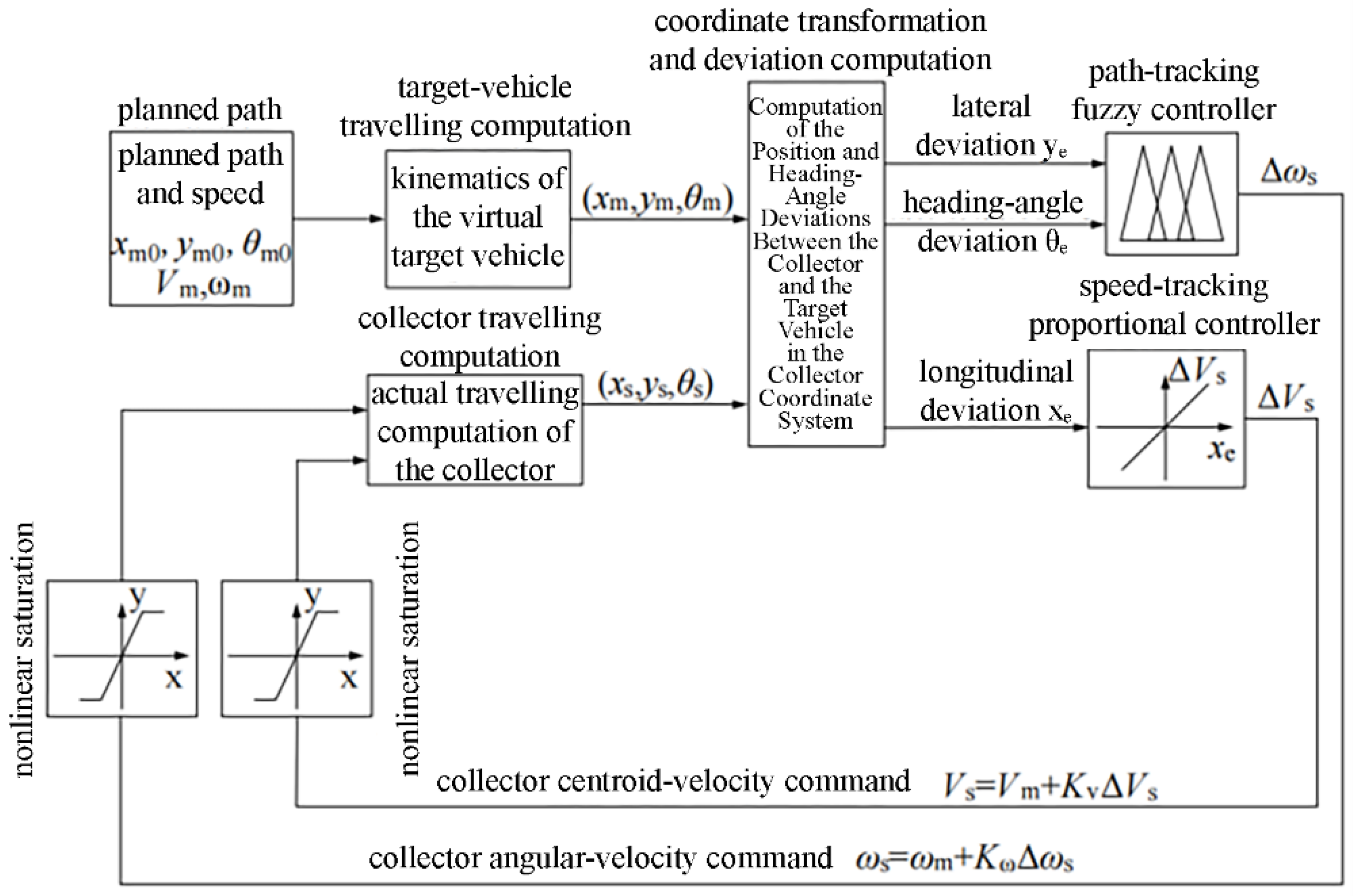

2.5. Trajectory-Tracking System for the Planned Path Based on Virtual Target Vehicle Following

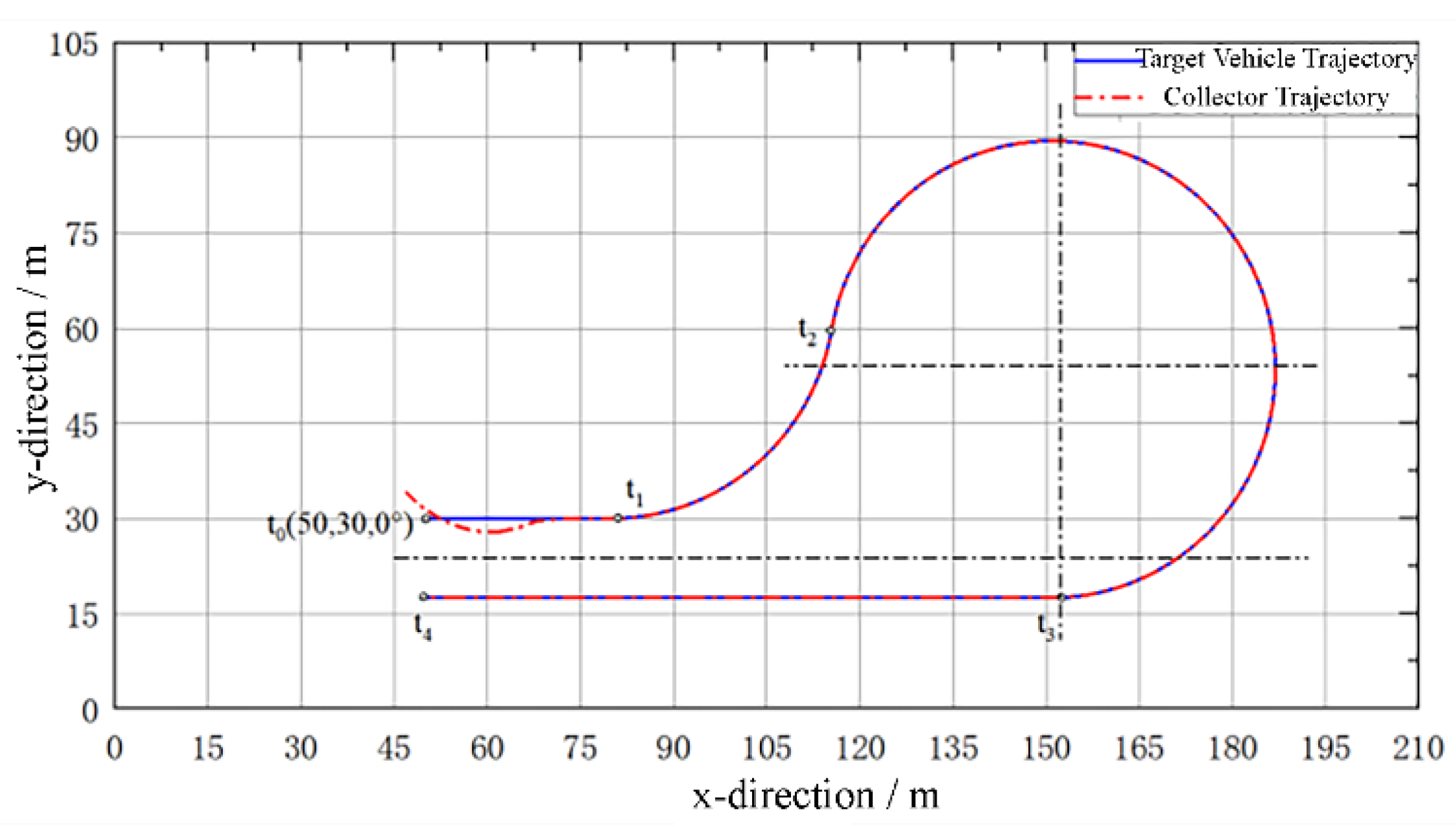

According to the proposed tracking method and the analysis of the control algorithms, a trajectory-tracking control system for the collector’s operational planned path based on virtual target vehicle following can be constructed, as shown in

Figure 3.

In this system, the predesigned planned path is stored in the “Planned Path” module in data form, and dynamic position and heading-angle information is generated through the “Target Vehicle Travelling Computation” module. The “Coordinate Transformation and Deviation Computation” module calculates the pose deviation between the collector and the target vehicle in the collector’s body coordinate system based on their positions and heading angles in the geodetic coordinate system. The path-tracking and speed-tracking controllers compute the collector’s angular-velocity and linear-velocity commands, respectively, from this pose deviation, enabling the collector to perform trajectory tracking of the planned path and speed. To prevent sudden changes in speed from causing impact disturbances to the seabed sediment, incremental control commands are adopted for both the angular-velocity fuzzy controller and the speed proportional controller. Meanwhile, nonlinear saturation limits are applied to the speed and angular velocity based on the maximum track speed of the collector.

5. Conclusion

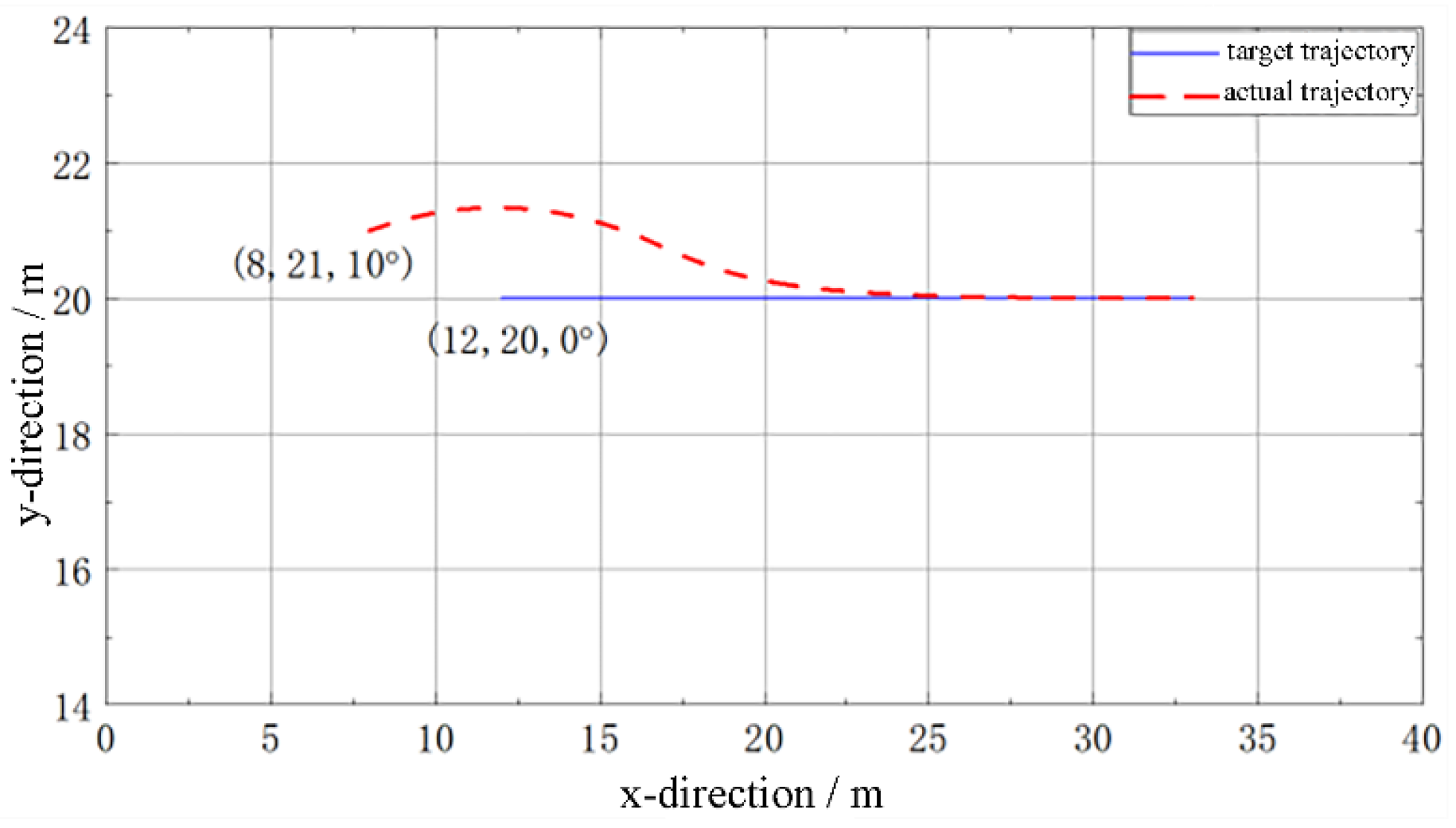

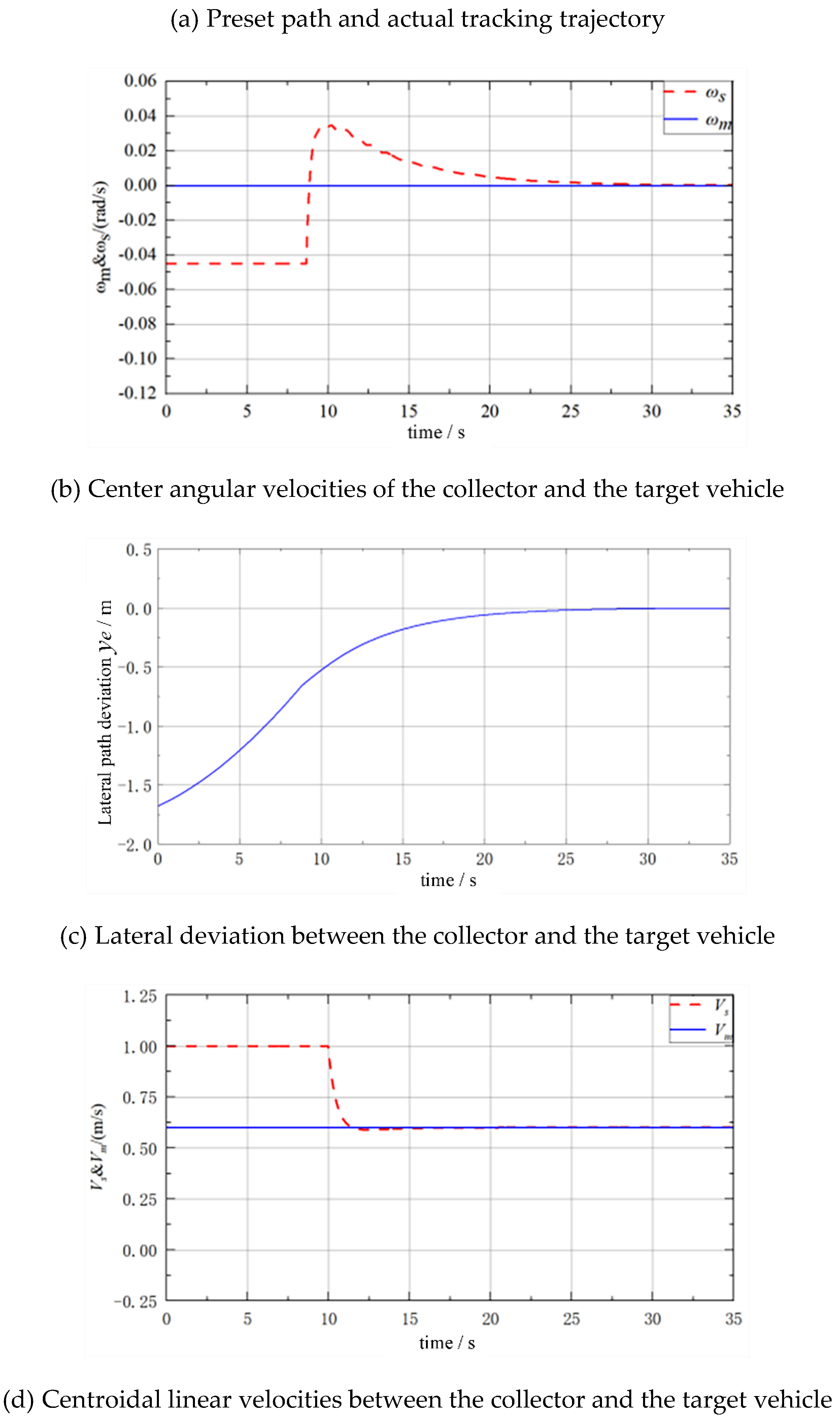

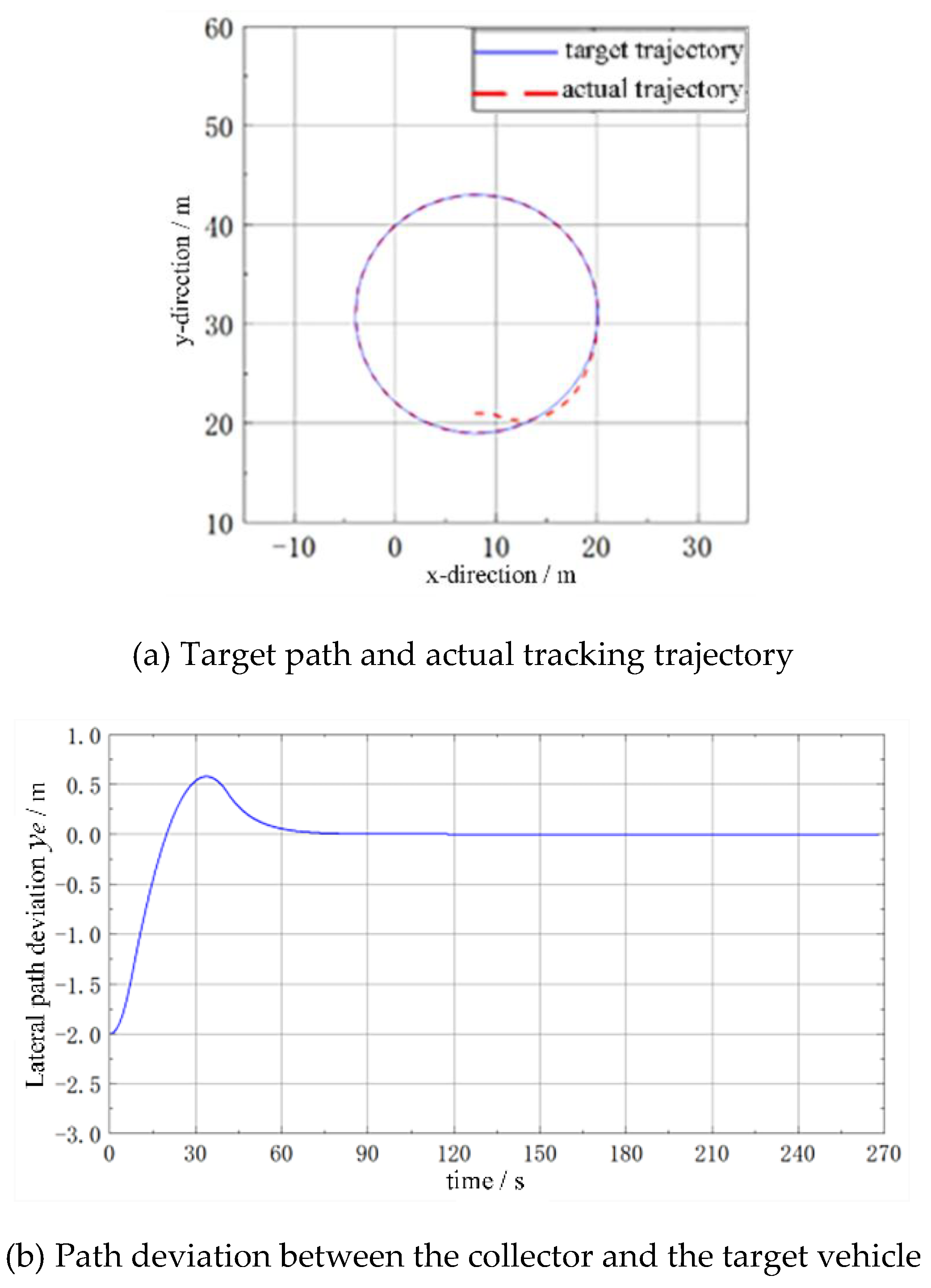

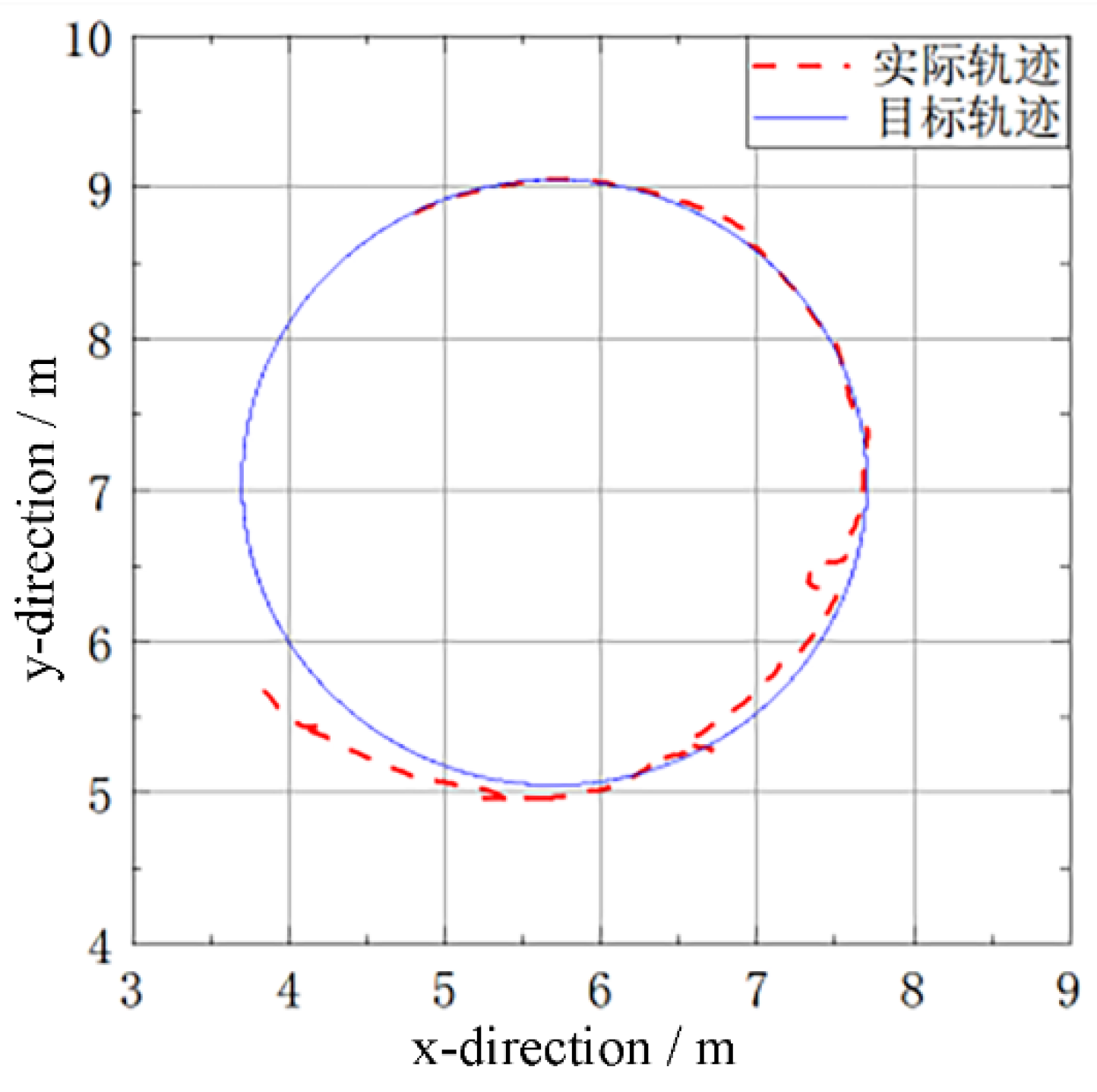

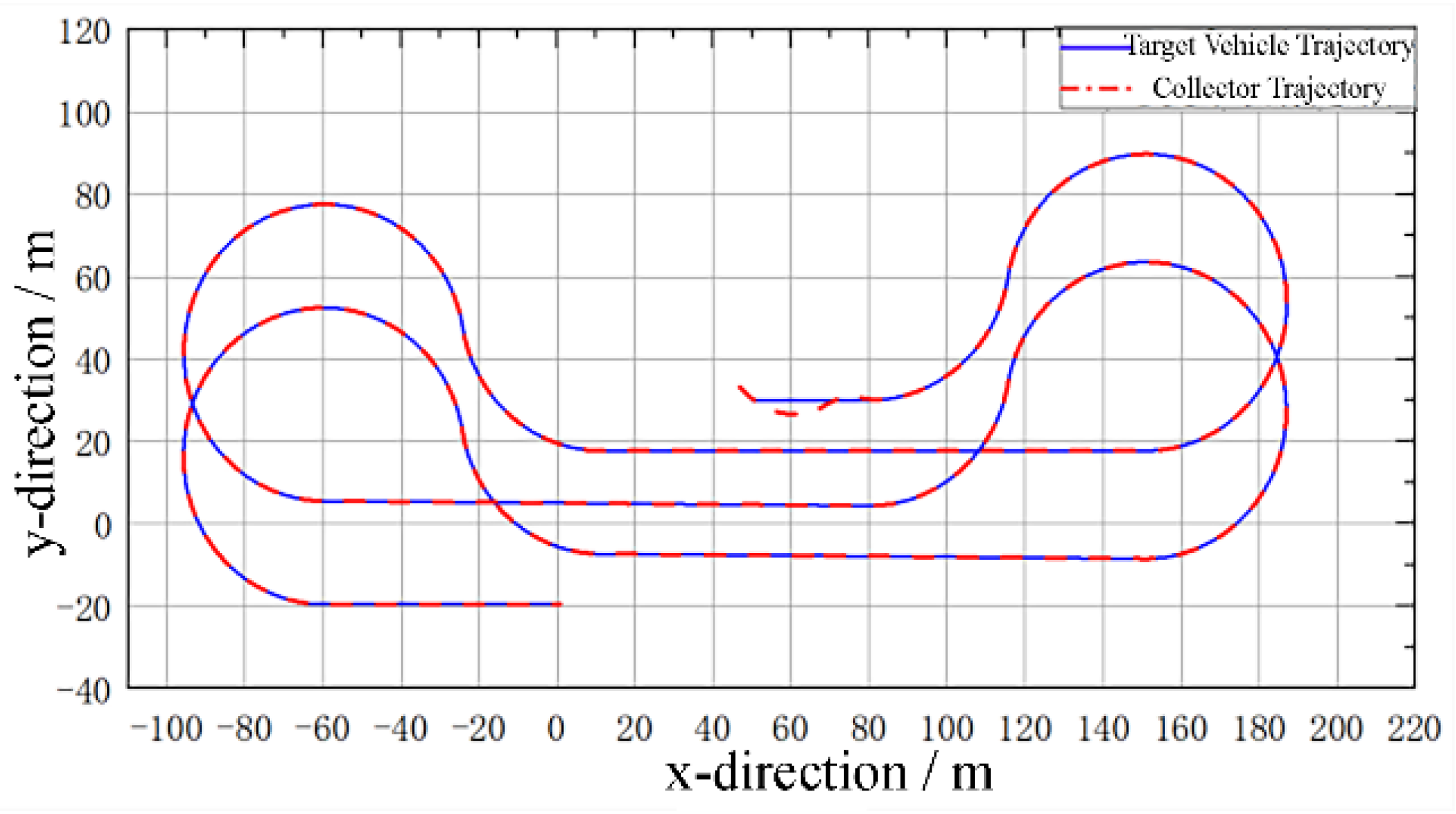

During deep-sea polymetallic nodule mining operations, to ensure mineral recovery efficiency, the collector typically travels in a straight, back-and-forth manner to traverse the entire mining area and collect nodules. At the same time, to avoid track slippage, the collector must decelerate and travel along large-curvature circular-arc paths during turning maneuvers. Therefore, the collector’s travelling process on the seabed must follow the planned path and speed required by the mining process. In this paper, considering the characteristics of the collector’s operational travelling and the deep-sea working environment, a study on trajectory tracking for the operational travelling of the deep-sea collector has been conducted, and the following conclusions have been obtained:

1)A trajectory-tracking scheme for the collector based on virtual target vehicle following is proposed. The virtual target vehicle travels according to the planned path and speed to generate a dynamic target path and speed. The collector adjusts its travelling speed and angular velocity according to the pose deviations between itself and the target vehicle, follows the target vehicle, and thereby achieves trajectory tracking of the planned path and speed.

2)A scheme in which the control commands for path tracking and speed tracking are computed separately is proposed. Based on the lateral deviation and heading-angle deviation between the collector and the target vehicle, the collector’s angular velocity is regulated through fuzzy logic control. Based on the longitudinal deviation between the collector and the target vehicle, the collector’s centroidal travelling speed is regulated through proportional control. These commands are coordinated within the same kinematic model of the collector to achieve path correction and speed tracking of the planned path.

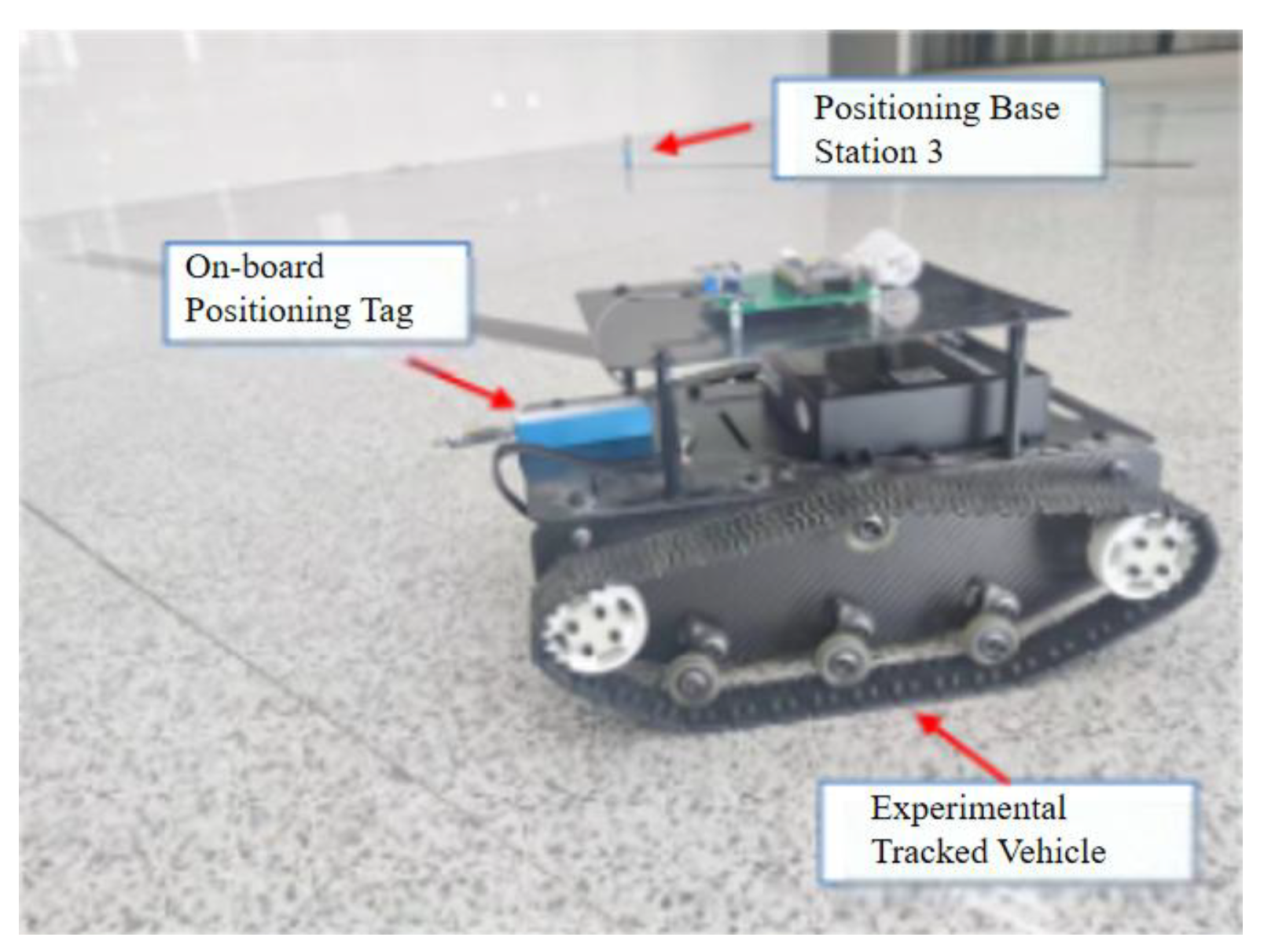

3)The results show that the designed trajectory-tracking system exhibits strong capabilities in both path and speed tracking. Under the operational travelling conditions of the collector, it can effectively follow the planned travelling and turning paths and speeds of the collector. The trajectory-tracking approach based on virtual target vehicle following can also generate dynamic planned paths and speeds for the entire mining area and enable the collector to follow the planned path and speed throughout the whole mining operation.