Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

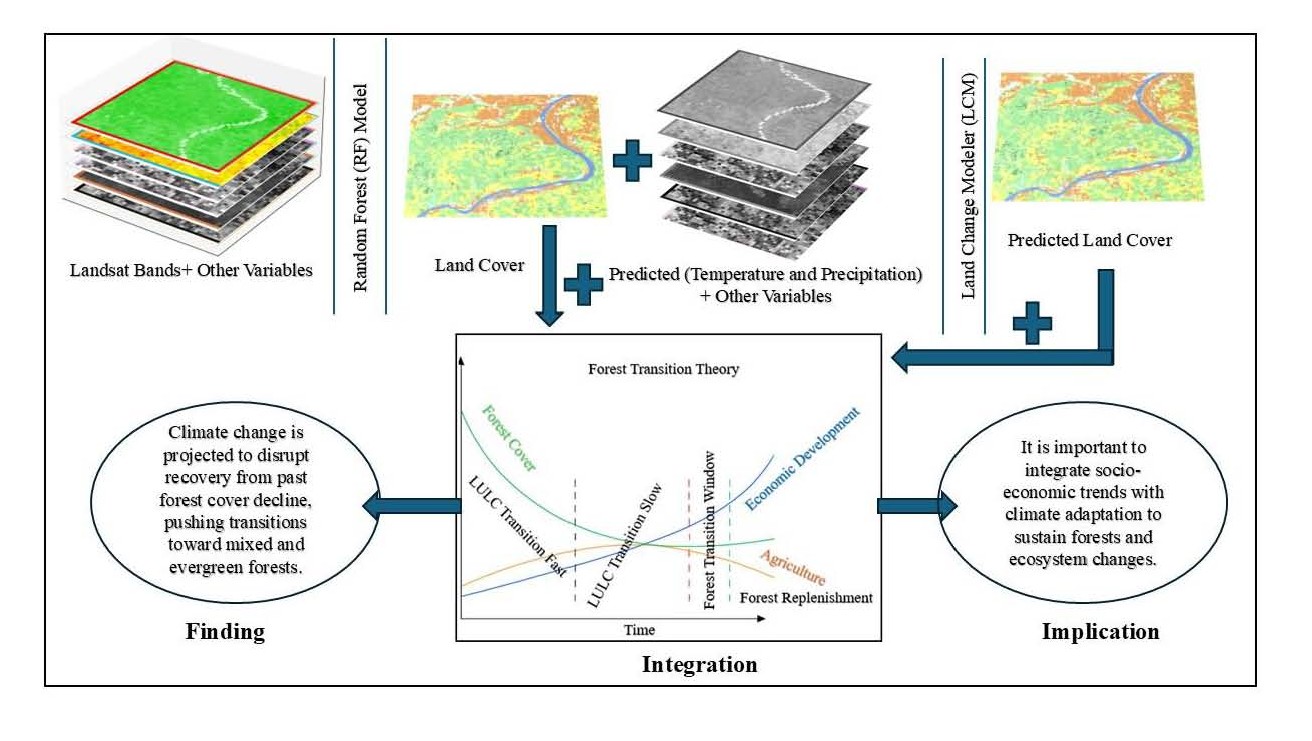

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Relationship Between Land Use Land Cover Change, Climate Change, and Ecosystem Services

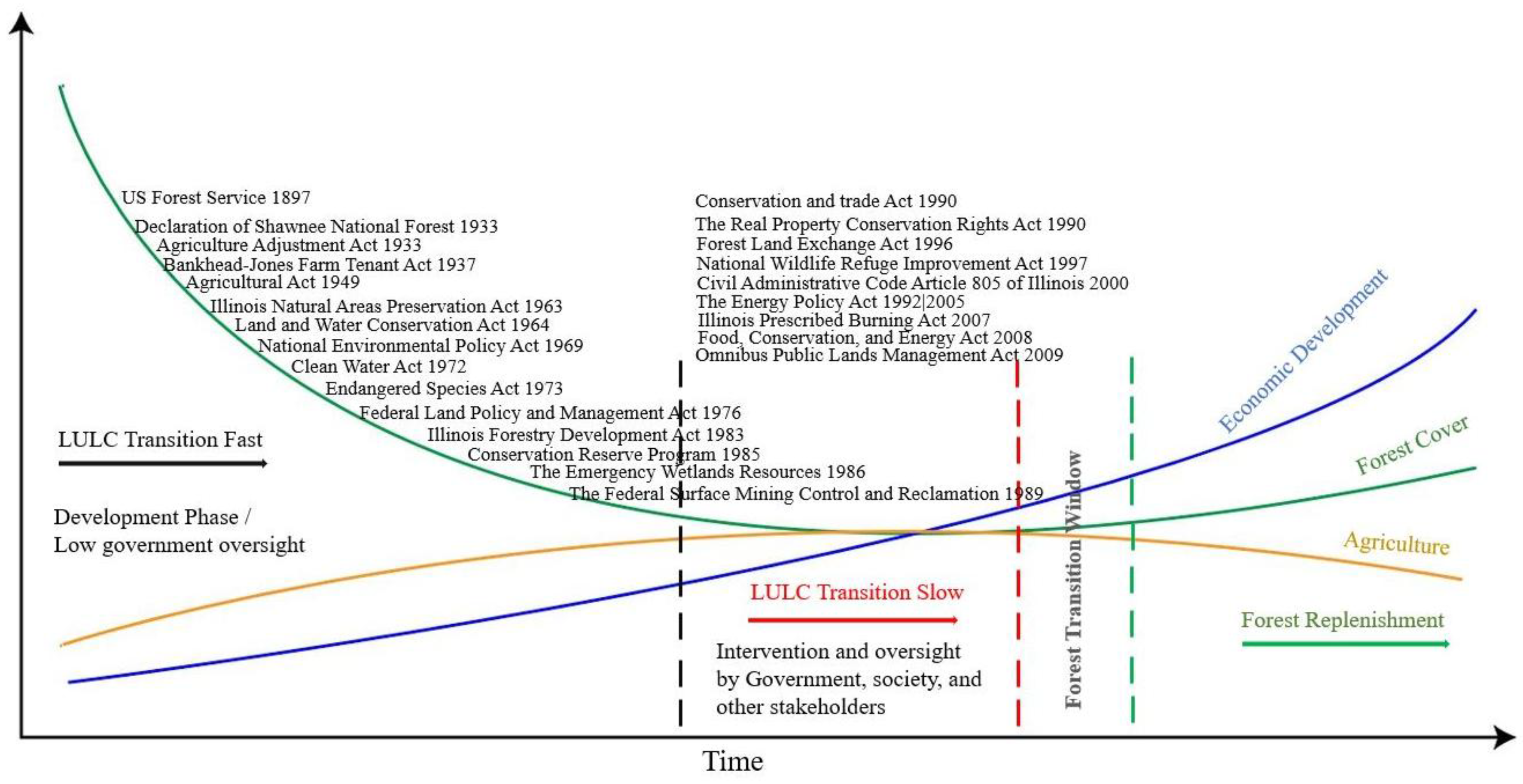

1.2. LULC in the Context of Forest Transition Theory

1.3. Research Motivation and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

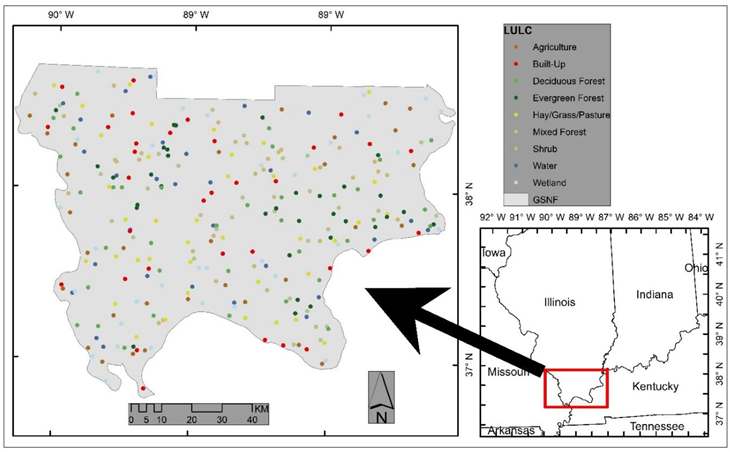

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.3. LULC Classification and Prediction

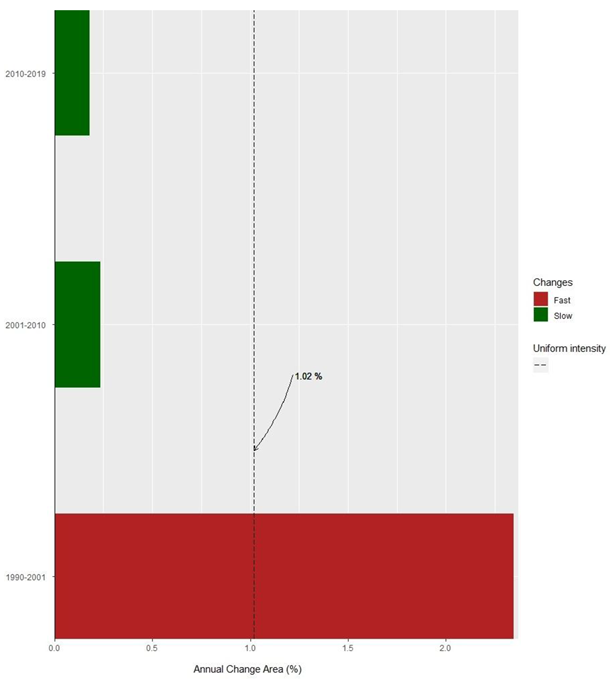

2.4. LULC Intensity

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy Assessment and LULC Change

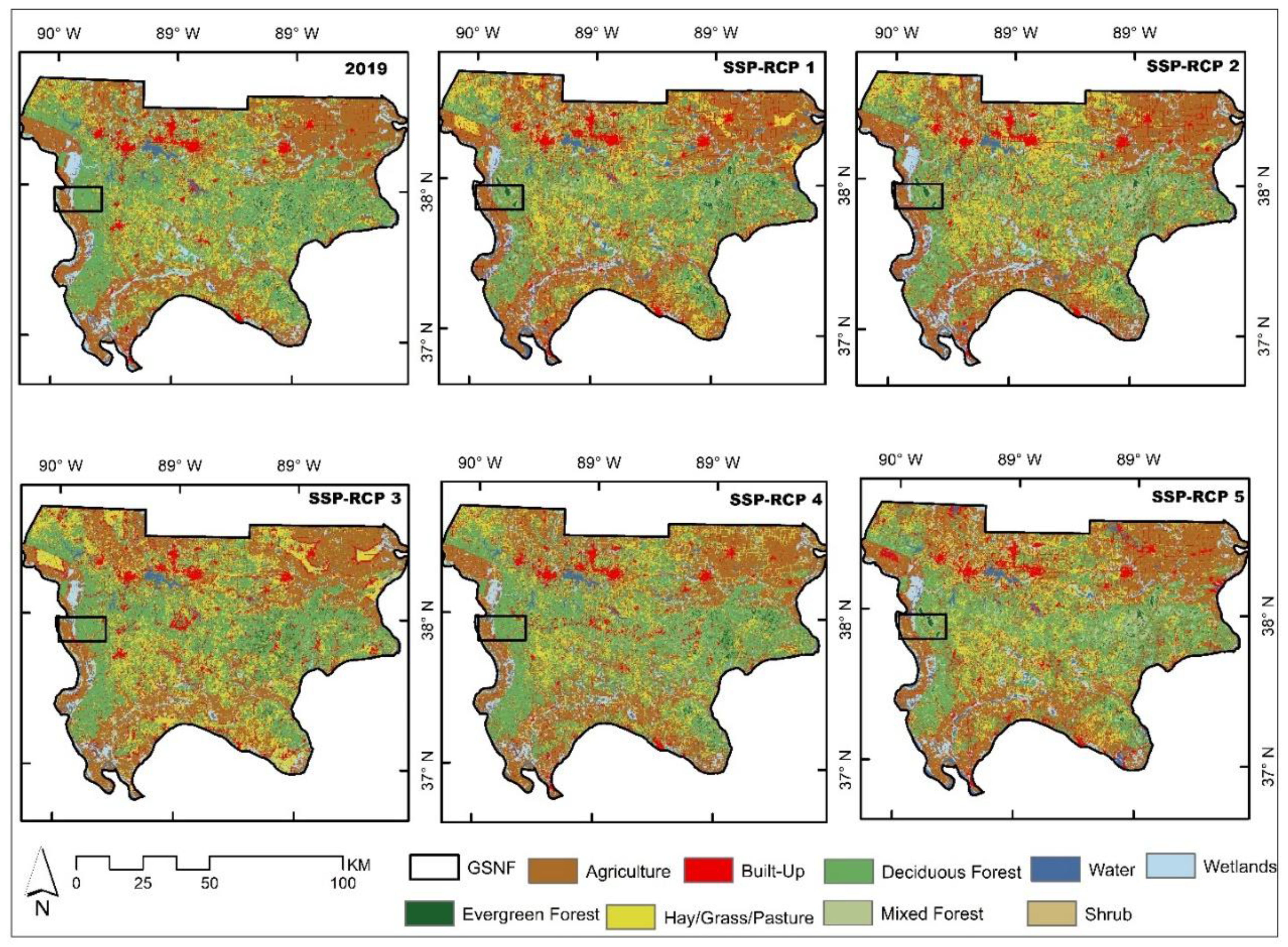

3.2. LULC Transition and Prediction

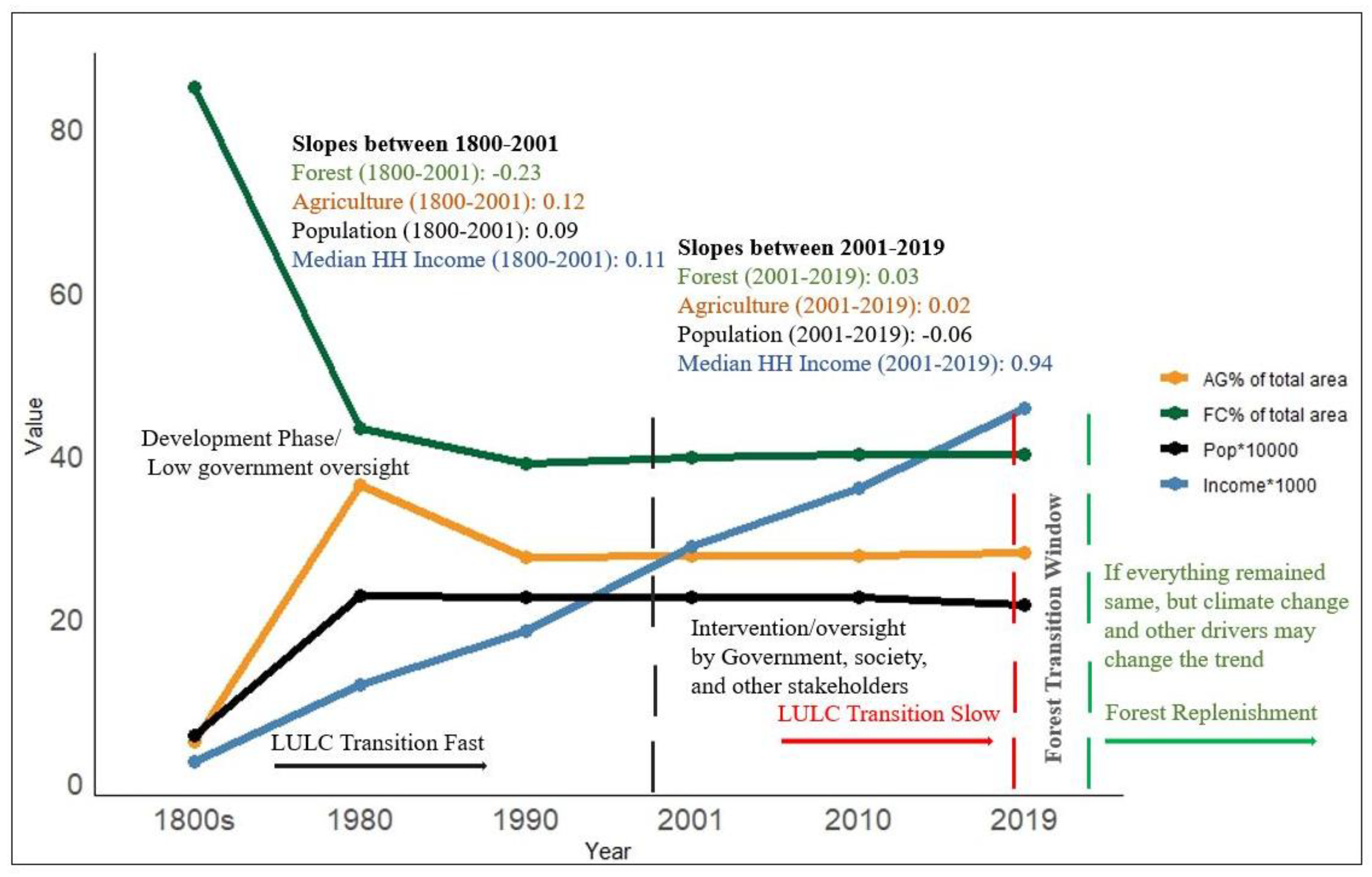

3.3. Testing Forest Transition Theory in the GSNF

4. Discussion

4.1. Accuracy Assessment

4.2. LULC Change

4.3. LULC Prediction

4.4. Forest Transition Theory Framework

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Locations Visited During the Summers of 2019 and 2020 to Train and Validate Random Forest Model for LULC Classification

Appendix B. LULC Classification and Its Definitions Based on the System Developed by Anderson in 1976

| LULC | LULC Description |

| Agriculture | Areas actively tilled or no-tilled for producing annual/perennial crops like corn, soybean, vegetables, and others. |

| Built-Up | The area is covered with structures such as commercial buildings and roads, as well as areas with a matrix consisting of vegetation, grass, and other structures (low-intensity residential area). |

| Deciduous Forest | Forest area dominated by deciduous tree species (species shedding foliage) and covers more than 80 percent. |

| Evergreen Forest | The forest area is dominated by evergreen tree species (those that do not shed foliage) and covers more than 80 percent. |

| Hay/Grass/Pasture | Areas of perennial or annual natural and domesticated grasses with a tree cover of less than 5 percent, and areas used for livestock grazing. |

| Mixed Forest | Forest areas where deciduous or evergreen forests comprise less than 80 percent of the land. |

| Water | The area covered by water and vegetation is less than 5 percent. |

| Shrub | Forest areas, either deciduous or evergreen, that are less than 5 meters tall and have a canopy cover greater than 20 percent. |

| Wetlands | Areas where the soil or substrate is occasionally wet with water or covered with it, and perennial herbaceous plants are often present. |

Appendix C. Interval Intensity of LULC Between 1990 and 2019. The Dashed Line Shows the Average Change Intensity that Partitions Intensity into Slow or fast LULC Conversion

References

- Foley, J.A.; DeFries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Barford, C.; Bonan, G.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chapin, F.S.; Coe, M.T.; Daily, G.C.; Gibbs, H.K.; et al. Global consequences of land use. Science 2005, 309, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.; Haverd, V.; Poulter, B.; Anthoni, P.; Quesada, B.; Rammig, A.; Arneth, A. Multimodel Analysis of Future Land Use and Climate Change Impacts on Ecosystem Functioning. Earth’s Future 2019, 7, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Geist, H.J.; Lepers, E. Dynamics of land-use and land-cover change in tropical regions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2003, 28, 205–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, J.J.; Lewis, D.J.; Nelson, E.; Plantinga, A.J.; Polasky, S.; Withey, J.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Martinuzzi, S.; Pennington, D.; Radeloff, V.C. Projected land-use change impacts on ecosystem services in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 7492–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leta, M.K.; Demissie, T.A.; Tränckner, J. Modeling and prediction of land use land cover change dynamics based on land change modeler (Lcm) in nashe watershed, upper blue nile basin, Ethiopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallimer, M.; Davies, Z.G.; Diaz-Porras, D.F.; Irvine, K.N.; Maltby, L.; Warren, P.H.; Armsworth, P.R.; Gaston, K.J. Historical influences on the current provision of multiple ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change 2015, 31, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickelson, J.B.; Holzmueller, E.J.; Groninger, J.W.; Lesmeister, D.B. Previous land use and invasive species impacts on long-term afforestation success. Forests 2015, 6, 3123–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, K.; Yang, J.; Fang, L. Assessing Ecosystem Services from the Forestry-Based Reclamation of Surface Mined Areas in the North Fork of the Kentucky River Watershed. Forests 2018, 9, 652–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Anderson, S.; Sutton, P. The future value of ecosystem services: Global scenarios and national implications. In Environmental Assessments; Environmental Assessments Edward Elgar Publishing: 2020; pp. 81-108.

- Gourevitch, J.D.; Alonso-Rodríguez, A.M.; Aristizábal, N.; de Wit, L.A.; Kinnebrew, E.; Littlefield, C.E.; Moore, M.; Nicholson, C.C.; Schwartz, A.J.; Ricketts, T.H. Projected losses of ecosystem services in the US disproportionately affect non-white and lower-income populations. Nature communications 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.; Ratliff, J.; Bliss, N.; Wein, A.; Sleeter, B.; Sohl, T.; Li, Z. Quantifying climate change mitigation potential in the United States Great Plains wetlands for three greenhouse gas emission scenarios. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2015, 20, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Mishra, U.; Scown, C.D.; Wills, S.A.; Adhikari, K.; Drewniak, B.A. Continental United States may lose 1.8 petagrams of soil organic carbon under climate change by 2100. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2022, 31, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benez-Secanho, F.J.; Dwivedi, P. Analyzing the impacts of land use policies on selected ecosystem services in the upper Chattahoochee Watershed, Georgia, United States. Environmental Research Communications 2021, 3, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, I.M.D.; Purvis, A.; Alkemade, R.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Ferrier, S.; Guerra, C.A.; Hurtt, G.; Kim, H.J.; Leadley, P.; Martins, I.S.; et al. Challenges in producing policy-relevant global scenarios of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 22, e00886–e00886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Schulte to Bühne, H.; Tulloch, A.; Dubois, G.; Macinnis-Ng, C.; Queirós, A.M.; Keith, D.A.; Wegmann, M.; Schrodt, F.; Stellmes, M.; et al. Satellite remote sensing of ecosystem functions: opportunities, challenges and way forward. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 2018, 4, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.P.; Ju, J.; Lewis, P.; Schaaf, C.; Gao, F.; Hansen, M.; Lindquist, E. Multi-temporal MODIS–Landsat data fusion for relative radiometric normalization, gap filling, and prediction of Landsat data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2008, 112, 3112–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, M.A.; Woodcock, C.E.; Olofsson, P.; Zhu, Z.; Loveland, T.; Stanimirova, R.; Arevalo, P.; Bullock, E.; Hu, K.-T.; Zhang, Y. Medium Spatial Resolution Mapping of Global Land Cover and Land Cover Change Across Multiple Decades From Landsat. Front. Remote Sens 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Motesharrei, S. Spatial and temporal patterns of global NDVI trends: correlations with climate and human factors. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 13233–13250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, B.; Kinigadner, J.; Ji, C.; Wright, B.; Wulfhorst, G. The TUM accessibility atlas: Visualizing spatial and socioeconomic disparities in accessibility to support regional land-use and transport planning. Networks and Spatial Economics 2018, 18, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Homer, C.; Yang, L.; Danielson, P.; Dewitz, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, Z.; Xian, G.; Howard, D. Overall methodology design for the United States national land cover database 2016 products. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafy, A.-A.; Dey, N.N.; Al Rakib, A.; Rahaman, Z.A.; Nasher, N.R.; Bhatt, A. Modeling the relationship between land use/land cover and land surface temperature in Dhaka, Bangladesh using CA-ANN algorithm. Environmental Challenges 2021, 4, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azari, M.; Billa, L.; Chan, A. Multi-temporal analysis of past and future land cover change in the highly urbanized state of Selangor, Malaysia. Ecological Processes 2022, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnood Motlagh, S.; Sadoddin, A.; Haghnegahdar, A.; Razavi, S.; Salmanmahiny, A.; Ghorbani, K. Analysis and prediction of land cover changes using the land change modeler (LCM) in a semiarid river basin, Iran. Land Degradation & Development 2021, 32, 3092–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P.; Chowdhury, R.R.; de Bremond, A.; Ellis, E.C.; Erb, K.-H.; Filatova, T.; Garrett, R.; Grove, J.M.; Heinimann, A.; Kuemmerle, T. Middle-range theories of land system change. Global environmental change 2018, 53, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Cui, X. Building Regional Sustainable Development Scenarios with the SSP Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5712–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, A.S. The forest transition. Area 1992, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudel, T.K.; Coomes, O.T.; Moran, E.; Achard, F.; Angelsen, A.; Xu, J.; Lambin, E. Forest transitions: towards a global understanding of land use change. Global environmental change 2005, 15, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, H. Envisioning better forest transitions: A review of recent forest transition scholarship. Heliyon 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.R.; Brancalion, P.H.; Crouzeilles, R.; Tambosi, L.R.; Piffer, P.R.; Lenti, F.E.; Hirota, M.; Santiami, E.; Metzger, J.P. Hidden destruction of older forests threatens Brazil’s Atlantic Forest and challenges restoration programs. Science advances 2021, 7, eabc4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Yang, H.; Tao, S.; Su, Y.; Guan, H.; Ren, Y.; Hu, T.; Li, W.; Xu, G.; Chen, M. Carbon storage through China’s planted forest expansion. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Eppinga, M.B.; Furrer, R.; Santos, M.J. The Effect of Dominant Land-Cover Transitions in Shaping Trajectories of Global Forest Change. Environmental Management 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auch, R.F.; Wellington, D.F.; Taylor, J.L.; Stehman, S.V.; Tollerud, H.J.; Brown, J.F.; Loveland, T.R.; Pengra, B.W.; Horton, J.A.; Zhu, Z. Conterminous United States Land-Cover Change (1985–2016): New Insights from Annual Time Series. Land 2022, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, C.; Dewitz, J.; Jin, S.; Xian, G.; Costello, C.; Danielson, P.; Gass, L.; Funk, M.; Wickham, J.; Stehman, S. Conterminous United States land cover change patterns 2001–2016 from the 2016 national land cover database. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 162, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.G.; Stevenson, A.P.; Knapp, B.O.; Kabrick, J.M.; Jensen, R.G. Is there evidence of mesophication of oak forests in the Missouri Ozarks. In Proceedings of the 19th Central Hardwood Forest Conference; 2014; pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, S.D.; Homoya, M.A.; Hoosier-Shawnee, E.L.S.T.; Undefined. Native plants and communities and exotic plants within the Hoosier-Shawnee ecological assessment area. In The Hoosier-Shawnee Ecological assesment, Thompson, F.R., Ed.; U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station: 2004; pp. 59-80.

- Thurau, R.G.; Fralish, J.; Hupe, S.; Fitch, B.; Carver, A. Ecological modeling for forest management in the Shawnee National Forest. In Proceedings of the In: Jacobs, Douglass F.; Michler, Charles H., eds. 2008. Proceedings, 16th Central Hardwood Forest Conference; 2008 April 8-9; West Lafayette, IN. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-P-24. Newtown Square, PA: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: 374-385., 2008.

- Nowacki, G.J.; Abrams, M.D. The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the eastern United States. BioScience 2008, 58, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, B. Borderlands: The Goshen Settlement of William Bolin Whiteside. Available online: https://whiteside.siue.edu/illinois-frontier (accessed on 11/24/2025).

- Anderson, J.R. A land use and land cover classification system for use with remote sensor data; Geological Survey US Governement Printing Office, 1976; Volume 964.

- Phiri, D.; Morgenroth, J. remote sensing Review Developments in Landsat Land Cover Classification Methods: A Review. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.K.; Roy, D.P. Using the 500 m MODIS land cover product to derive a consistent continental scale 30 m Landsat land cover classification. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 197, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Saber, M.; Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H.; Homayouni, S. Urban Land Use and Land Cover Change Analysis Using Random Forest Classification of Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galiano, V.F.; Ghimire, B.; Rogan, J.; Chica-Olmo, M.; Rigol-Sanchez, J.P. An assessment of the effectiveness of a random forest classifier for land-cover classification. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2012, 67, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical com-puting. 2017.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria 2020.

- Eastman, J. TERRSET Tutorial. 2018.

- Swanwick, R.H.; Read, Q.D.; Guinn, S.M.; Williamson, M.A.; Hondula, K.L.; Elmore, A.J. Dasymetric population mapping based on US census data and 30-m gridded estimates of impervious surface. Scientific Data 2022, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.J.; Díaz-Pacheco, J.; Moya-Gómez, B. A cellular automata land use model for the R software environment. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Aldwaik, S.Z.; Pontius, R.G. Intensity analysis to unify measurements of size and stationarity of land changes by interval, category, and transition. Landscape and Urban Planning 2012, 106, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, X.; Guo, Q.; Wu, X.; Fu, Y.; Xie, T.; He, C.; Zang, J. Intensity and Stationarity Analysis of Land Use Change Based on CART Algorithm. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vojteková, J.; Vojtek, M. GIS-Based Landscape Stability Analysis: A Comparison of Overlay Method and Fuzzy Model for the Case Study in Slovakia. Professional Geographer 2019, 71, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E.F. Forest transition in Vietnam and displacement of deforestation abroad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 16139–16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Long, Y.; Tang, Y.; Mao, Y. Impact of economic growth and agricultural expansion on forest cover in ASEAN: New evidence for forest transition theory. Forest Policy and Economics 2025, 178, 103576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-S.; Ling, J.-Y.; Lin, T.-W.; Liu, Y.-T.; Shen, Y.-C.; Kono, Y. Quantifying uncertainty in land-use/land-cover classification accuracy: a stochastic simulation approach. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2021, 9, 628214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmate, S.S.; Wagner, P.D.; Fohrer, N.; Pandey, A. Assessment of uncertainties in modelling land use change with an integrated cellular automata–Markov chain model. Environmental Modeling & Assessment 2022, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G.; Gu, J.; Yadav, K.; Thenkabail, P.; Ozdogan, M. Global land cover mapping: A review and uncertainty analysis. Remote Sensing 2014, 6, 12070–12093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanka, D.E.; Shaver, D.K. Land-Use Change Trends in the Interior Lowland Ecoregion; 2007-5145; 2007.

- Li, X.; Tian, H.; Pan, S.; Lu, C. Four-century history of land transformation by humans in the United States: 1630–2020: annual and 1 km grid data for the HIStory of LAND changes (HISLAND-US). Earth System Science Data Discussions 2022, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDNR. Illinois forest action plan: a statewide forest resource assessment and strategy; 2019.

- IDNR. Illinois Forest Action Plan: A statewide forest resource assessment and strategy 2018 revision; 2018.

- Gibson, D.J.; Thapa, S.; Benda, C. Herbaceous Layer Response to Forest Management at Trail of Tears State Forest from 2014-2018; Shawnee RC&D: 2019.

- Anderson, R.C. Presettlement forests of Illinois; 1991; pp. 9-19.

- Iverson, L.R.; Taft, J.B. Past, Present, and Possible Future Trends with Climate Change in Illinois Forests. Erigenia: Journal of the Southern Illinois Native Plant Society 2022, 53, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, K.R.; Speidel, D.R. Why Does the Repaired Len Small Levee, Alexander County, Illinois, US Continue to Breach during Major Flooding Events? Open Journal of Soil Science 2020, 10, 16–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Flint, C. Southern Illinois Land Use; University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign: Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sohl, T.L.; Sayler, K.L.; Bouchard, M.A.; Reker, R.R.; Friesz, A.M.; Bennett, S.L.; Sleeter, B.M.; Sleeter, R.R.; Wilson, T.; Soulard, C. Spatially explicit modeling of 1992–2100 land cover and forest stand age for the conterminous United States. Ecological Applications 2014, 24, 1015–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wear, D.N. Forecasts of county-level land uses under three future scenarios: a technical document supporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-141. Asheville, NC: US Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 41 p. 2011, 141, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebbles, D.J.; Angel, J.; Petersen, K.; Lemke, A.M. An Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Change in Illinois; 2021.

- Smith, A.B.; Alsdurf, J.; Knapp, M.; Baer, S.G.; Johnson, L.C. Phenotypic distribution models corroborate species distribution models: A shift in the role and prevalence of a dominant prairie grass in response to climate change. Global Change Biology 2017, 23, 4365–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belesky, D.P.; Malinowski, D.P. Grassland communities in the USA and expected trends associated with climate change. Acta Agrobotanica 2016, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, A.C.; Reilly, J.; Blanc, E. Agriculture and forest land use change in the continental United States: Are there tipping points? Iscience 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, W.K.; Yiotis, C.; Murray, M.; Parnell, A.; Wright, I.J.; Spicer, R.A.; Lawson, T.; Caballero, R.; McElwain, J.C. Rising CO2 drives divergence in water use efficiency of evergreen and deciduous plants. Science Advances 2019, 5, eaax7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dial, R.J.; Maher, C.T.; Hewitt, R.E.; Sullivan, P.F. Sufficient conditions for rapid range expansion of a boreal conifer. Nature 2022, 608, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B.; Bermudez, R.; Montgomery, R.A.; Rich, R.L.; Rice, K.E.; Hobbie, S.E.; Stefanski, A. Even modest climate change may lead to major transitions in boreal forests. Nature 2022, 608, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, H.; McKenney, D. Envisioning a global forest transition: Status, role, and implications. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosonuma, N.; Herold, M.; De Sy, V.; De Fries, R.S.; Brockhaus, M.; Verchot, L.; Angelsen, A.; Romijn, E. An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environmental Research Letters 2012, 7, 044009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeter, B.M.; Liu, J.; Daniel, C.; Rayfield, B.; Sherba, J.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Zhu, Z.; Selmants, P.C.; Loveland, T.R. Effects of contemporary land-use and land-cover change on the carbon balance of terrestrial ecosystems in the United States. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 045006–045006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo Cuaresma, J.; Danylo, O.; Fritz, S.; McCallum, I.; Obersteiner, M.; See, L.; Walsh, B. Economic development and forest cover: evidence from satellite data. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 40678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Sources | Year |

| Landsat | USGS (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) | 1990-2019 |

| NAIP | NRCS (https://nrcs.app.box.com/v/naip) | 2001-2019 |

| LULC Map | Illinois Clearinghouse (https://clearinghouse.isgs.illinois.edu/) | 1800s |

| LULC Map | US EPA (https://www.epa.gov/hydrowq/metadata-giras) | 1980 |

| Population | US Census Bureau (https://data.census.gov/) | 1800-2019 |

| Median Household Income | US Census Bureau (https://data.census.gov/) | 1800-2020 |

| Landsat | Bands | Wavelength | Other Variables/Indices | Description |

| Landsat 5TM | Band 1 - Blue | 0.45-0.52 | DEM | NA |

| Band 2 - Green | 0.52-0.60 | Aspect | NA | |

| Band 3 - Red | 0.63-0.69 | Slope | NA | |

| Band 4 - NIR | 0.76-0.90 | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | NDVI = (NIR – Red) / (NIR + Red) | |

| Band 5 - NIR | 1.55-1.75 | Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | GNDVI = (NIR-GREEN) /(NIR+GREEN) | |

| Band 7 - SWIR | 2.08-2.35 | Enhanced Vegetation Index | EVI = G * ((NIR – R) / (NIR + C1 * R – C2 * B + L)) | |

| Landsat 7 ETM | Band 1 - Blue | 0.45-0.52 | Advanced Vegetation Index | AVI = [NIR * (1-Red) * (NIR-Red)] 1/3 |

| Band 2 - Green | 0.52-0.60 | Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | SAVI = ((NIR – R) / (NIR + R + L)) * (1 + L) | |

| Band 3 - Red | 0.63-0.69 | Normalized Difference Moisture Index | NDMI = (NIR – SWIR) / (NIR + SWIR) | |

| Band 4 - NIR | 0.77-0.90 | Moisture Stress Index | MSI = MidIR / NIR | |

| Band 5 - SWIR | 1.55-1.75 | Green Coverage Index | GCI = (NIR) / (Green) – 1 | |

| Band 7 SWIR | 2.09-2.35 | Normalized Burned Ratio Index | NBR = (NIR – SWIR) / (NIR+ SWIR) | |

| Landsat 8 OLI | Band 1 - Coastal aerosol | 0.43-0.45 | Bare Soil Index | BSI = ((Red+SWIR) – (NIR+Blue)) / ((Red+SWIR) + (NIR+Blue)) |

| Band 2 - Blue | 0.45-0.51 | Normalized Difference Water Index | NDWI = (NIR – SWIR) / (NIR + SWIR) | |

| Band 3 - Green | 0.53-0.59 | Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index | ARVI = (NIR – (2 * Red) + Blue) / (NIR + (2 * Red) + Blue) | |

| Band 4 - Red | 0.64-0.67 | Structure Insensitive Pigment Index | SIPI = (NIR – Blue) / (NIR – Red) | |

| Band 5 - NIR | 0.85-0.88 | Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index | MSAVI=(2 * NIR + 1 – sqrt ((2 * NIR + 1)2 – 8 * (NIR - R))) / 2 | |

| Band 6 - SWIR | 1.57-1.65 | Normalized Difference Built-up Index | NDBI = (SWIR – NIR) / (SWIR + NIR) | |

| Band 7 - SWIR | 2.11-2.29 |

| LULC/Parameters | 1990 | 2001 | 2010 | 2019 | ||||

| Users Accuracy | Producers Accuracy | Users Accuracy | Producers Accuracy | Users Accuracy | Producers Accuracy | Users Accuracy | Producers Accuracy | |

| Agriculture | 89.067 | 95.514 | 97.341 | 99.183 | 94.549 | 98.932 | 90.958 | 98.783 |

| Built-Up | 97.678 | 97.702 | 97.534 | 1.004 | 98.924 | 99.175 | 99.623 | 99.467 |

| Deciduous Forest | 96.345 | 97.269 | 94.924 | 98.476 | 97.105 | 97.939 | 96.465 | 98.027 |

| Evergreen Forest | 80.581 | 83.611 | 90.117 | 80.625 | 82.932 | 85.073 | 90.294 | 88.289 |

| Hay/Grass/Pasture | 79.327 | 58.252 | 92.666 | 91.848 | 97.424 | 83.475 | 96.987 | 84.500 |

| Mixed Forest | 67.109 | 68.992 | 89.560 | 86.001 | 87.016 | 87.161 | 93.630 | 86.199 |

| Water | 96.385 | 99.390 | 98.951 | 99.378 | 96.926 | 99.195 | 99.194 | 98.820 |

| Shrub | 82.262 | 56.550 | 96.380 | 78.051 | 94.985 | 85.049 | 96.412 | 96.979 |

| Wetlands | 92.436 | 73.070 | 95.828 | 93.808 | 97.101 | 94.869 | 96.789 | 95.352 |

| Overall Accuracy | 0.929 | 0.949 | 0.951 | 0.959 | ||||

| Kappa Coefficient | 0.898 | 0.933 | 0.936 | 0.945 | ||||

| LULC | %cover by year | % change between years | ||||||

| 1990 | 2001 | 2010 | 2019 | 1990-2001 | 2001-2010 | 2010-2019 | 1990-2019 | |

| Agriculture | 27.463 | 27.619 | 27.699 | 28.054 | 0.568 | 0.293 | 1.282 | 2.154 |

| Built-Up | 6.844 | 7.133 | 7.237 | 7.303 | 4.218 | 1.517 | 0.915 | 6.703 |

| Deciduous Forest | 35.128 | 35.489 | 35.406 | 35.604 | 1.027 | -0.234 | 0.557 | 1.354 |

| Evergreen Forest | 1.124 | 1.103 | 1.103 | 1.097 | -1.897 | 0.066 | -0.526 | -2.348 |

| Hay/Grass/Pasture | 17.634 | 16.120 | 15.163 | 14.811 | -8.585 | -5.428 | -2.318 | -16.006 |

| Mixed Forest | 2.266 | 2.781 | 2.837 | 2.864 | 22.757 | 2.447 | 0.957 | 26.403 |

| Water | 2.488 | 2.730 | 3.065 | 2.891 | 9.722 | 13.448 | -5.678 | 16.177 |

| Shrub | 0.423 | 0.258 | 0.810 | 0.598 | -39.081 | 130.351 | -26.147 | 41.259 |

| Wetlands | 6.630 | 6.768 | 6.680 | 6.778 | 2.078 | -1.318 | 1.453 | 2.224 |

| LULC | SSP-RCP 1 | SSP-RCP 2 | SSP-RCP 3 | SSP-RCP 4 | SSP-RCP 5 |

| Agriculture | -0.239 | -3.415 | -10.380 | -3.576 | 8.204 |

| Built-Up | 42.609 | 39.071 | 35.905 | 17.122 | 28.377 |

| Deciduous Forest | -15.415 | -16.870 | -8.501 | -3.110 | -19.873 |

| Evergreen Forest | -7.025 | -17.134 | 2.903 | -4.535 | -18.752 |

| Hay/Grass/Pasture | 19.184 | 15.504 | 38.377 | 6.232 | 11.572 |

| Mixed Forest | -4.442 | 12.453 | -37.082 | 22.846 | 23.629 |

| Water | 39.701 | 28.748 | 29.793 | 32.624 | 34.013 |

| Shrub | 37.452 | 33.797 | -12.707 | 8.924 | 8.091 |

| Wetlands | -23.096 | 9.045 | -31.318 | -24.547 | -7.600 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).