1. Introduction

Human-caused alterations of the Earth's surface frequently lead to the destruction of forests and woodlands, as well as the degradation of forested areas [

1,

2,

3]. The primary issues around forest conservation and livelihood change issues are attributed to land use and human interactions [

4,

5,

6]. These human activities are linked to deforestation and forest degradation which work against the protection of forests and their management systems [

7,

8]. Assessing these are vital for effective local, regional, and global development of environmental settings [

9,

10]. The impact of land use change and the factors that drive it have been shown to affect forest cover and biodiversity negatively, which has important implications as biodiversity sustains the livelihoods that people depend on to survive [

11,

12,

13].

It is important to evaluate drivers that contribute to changes and degradation in forest cover and protect areas from the local perspective [

10,

14]. This approach ensures that interventions are relevant to the specific context, garner community support, address root causes, and adapt to changing conditions, ultimately leading to better outcomes for both forests and the local people who depend on them, often directly, for their livelihoods [

15,

16]. Incorporating a local perspective enables the consideration of both environmental and human aspects of forest management. Forests play a crucial role as a valuable resource, providing a diverse array of ecosystem services, including timber, food, fuel, and non-timber bioproducts [

17]. Additionally, they contribute to the maintenance of ecological functions, including carbon storage, nutrient cycling, water and air purification, and the preservation of wildlife habitat; services that are essential for promoting human well-being and supporting life [

18,

19,

20]. Human activities have led to a 60% decrease in ecosystem services globally, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [

21], reiterated by [

14,

22]. As the primary means of subsistence for people living in poverty, they rely heavily on these services, so often lose the most in terms of ecosystem service losses [

23,

24,

25].

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [

21], when a driver has an evident influence, it is referred to as a "direct driver". When it underlies or leads to a "direct driver," it is referred to as an "indirect" (underlying) driver. Direct drivers have a clear and straightforward cause-and-effect relationship with the observed changes. They comprise activities or actions that directly affect forest cover and land use, such as agriculture, urban expansion, mining, logging, livestock grazing, and forest fires, among others [

2,

26,

27]. Indirect drivers encompass complex political, socio-economic, cultural, and technological interactions [

13,

28,

29]. Further indirect drivers contributing to deforestation include corruption, inadequate governance, population growth, climate change, and ambiguous land tenure arrangements [

15,

30,

31]. According to Geist and Lambin [

32] and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [

21] indicate that changes in these drivers influence not only the land cover but also change the forest although the drivers and their impacts differ regionally.

In most developing nations of Latin America, Asia, and Africa, the key driver of deforestation is the conversion of forest land to agriculture (commercial and subsistence) linked to activities such as logging, charcoal, collecting fuelwood and forest fires and livestock grazing [

10,

33,

34].

In Nigeria, research has been conducted on LULCC, and the drivers of it using remote sensing and survey data [

35,

36,

37], but there has been limited research on the current drivers of protected and forest reserves changes, particularly in North Central Nigeria [

35,

38,

39]. Although remote sensing data and GIS applications have been used in quantifying the extent of changes in land use and forest change in many regions [

40,

41,

42,

43], it cannot explain the rationale behind the anthropogenic drivers that are felt or perceived by the stakeholders in the forest communities. Understanding perceptions is important as it affects how people behave and their attitudes towards the forest. Gaining this understanding demands quantitative and qualitative approaches for detailed understanding beyond just the observation of the change. This paper aims to evaluate the perceived drivers of forest change using an empirical perspective at the local community level including those populations living close to the gazetted forest reserves. The study assesses the socio-economic activities in the gazetted forest-dependent community, evaluates direct and indirect drivers that influence the gazetted forest reserves change and compares the drivers and human activities across the three forest regions in the state.

2. Research Design and Methods

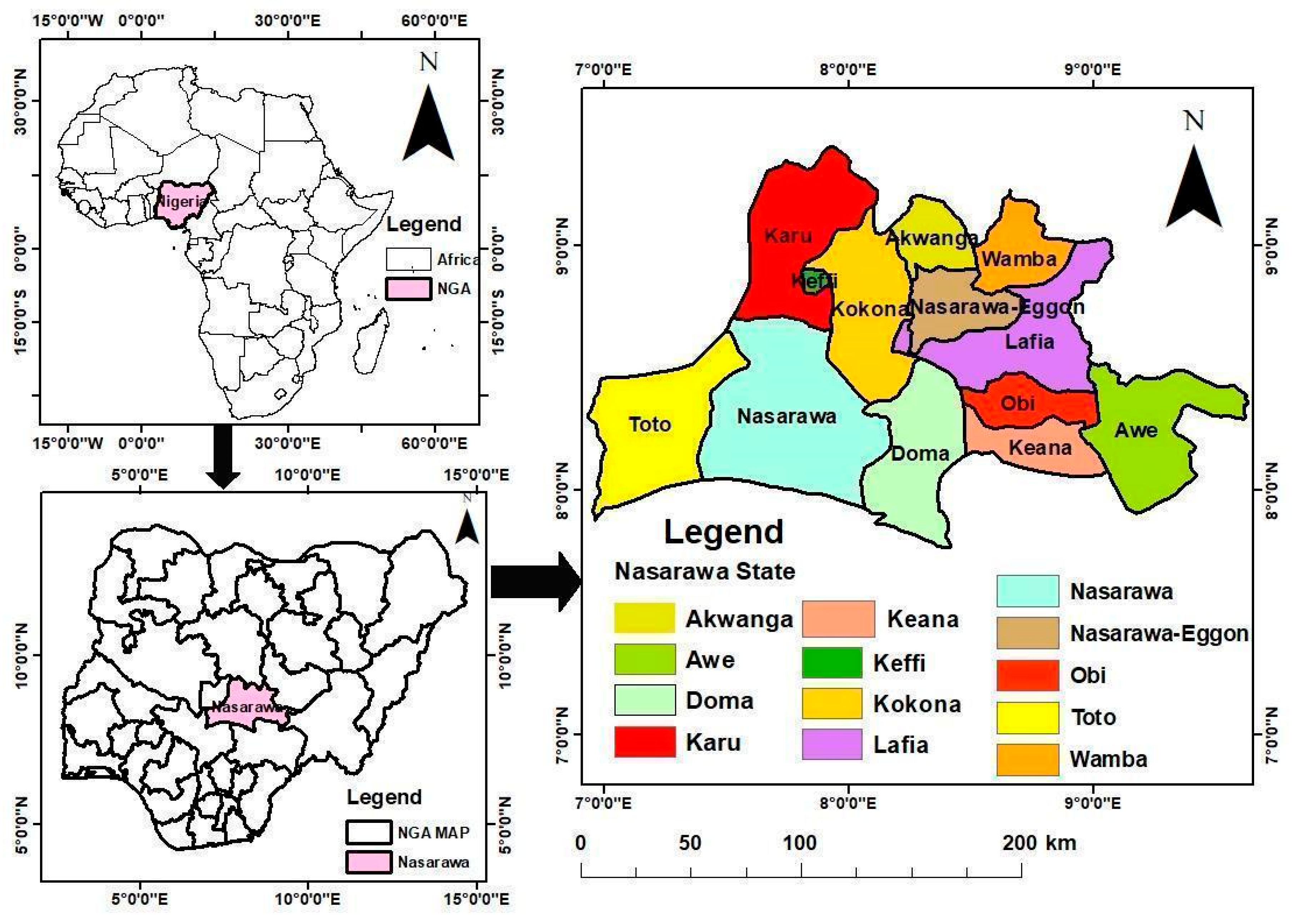

This section describes the geographical setting of the research area, the methods used, procedures employed, and the techniques used to gather and analyse data. This study was carried out in Nasarawa State (

Figure 1).

The choice to carry out this research in Nigeria was driven by its strategic position in the West African Guinea savanna region (

Figure 1), which is renowned for its economy based on natural resources and rich biodiversity [

44]. Nasarawa State, located in North Central Nigeria within the Guinea savanna zone, was selected due to migration caused by conflicts between farmers and herders, prompting people to seek safety and livelihoods in Nasarawa State [

45,

46,

47,

48]. This influx has enhanced Nasarawa's reputation as a significant national food producer, supporting a variety of food and cash crops and drawing individuals in search of sustainable livelihoods [

49,

50]. As observed worldwide, the expansion of farmland is the leading cause of deforestation [

51]. The state exhibits characteristics of both Southern and Northern Guinea, with Northern Guinea grass species resembling those of the southern region, featuring grasslands and woody shrubs [

52,

53]. This vegetation is subjected to annual fires caused by human activity [

54,

55], with species such as

Parkia biglobosa (African locust bean tree),

Vitellaria paradoxa (Shea butter tree),

Milicia excelsa (Iroko tree)

Burkea africana (wild syringa),

Anogeisses leiocarpa (African, birch satin wood)

Afromosia, (African teak) are resistant to fire [

55,

56]. Additionally, the area's vegetation has evolved over centuries due to selective tree harvesting based on their utility to the local population and ongoing fire damage [

35,

54], with trees developing long taproots and thick bark for survival [

55,

57].

Nasarawa State receives between 1100 and 2000mm of annual rainfall, with moderate to heavy precipitation during the wet season supporting agriculture and vegetation [

52,

54,

57]. The dry season, spanning from November to March, brings lower humidity, higher temperatures, and Harmattan winds that affect temperature and visibility [

57]. The vegetation and climate of Nasarawa State shape agricultural practices, with land use ranging from agricultural to urban. Agriculture is the primary economic activity, with land allocated for crops and livestock. The communities engage in subsistence farming reliant on seasonal rainfall [

29]. The state's fertile soils and climate support crops such as yams, maize, rice, and cassava, even within designated forest reserves [

35,

58].

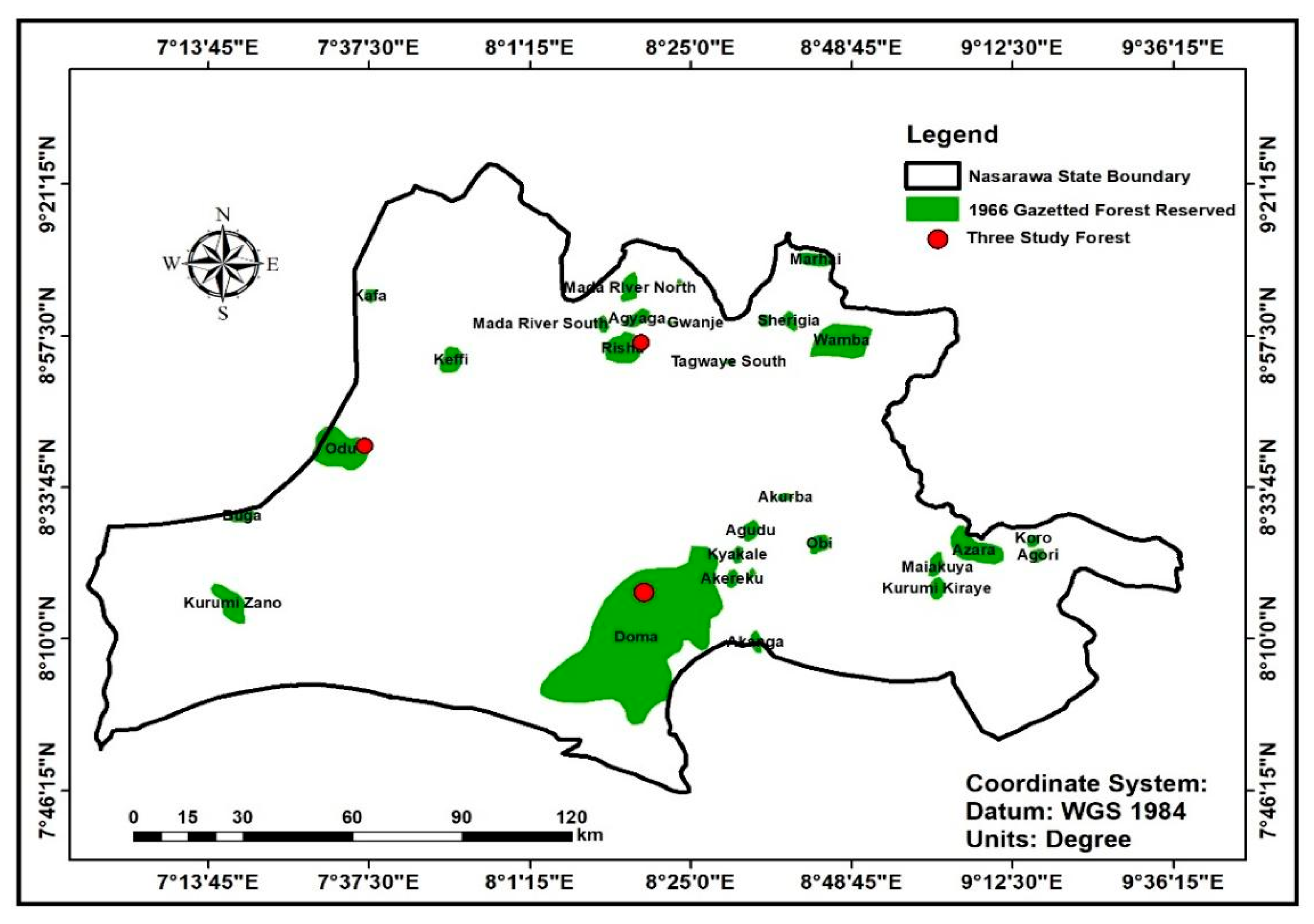

Nasarawa State is home to 41 officially recognized forest reserves (

Figure 2), which were established and charted in 1966 with legal documentation, although some were proposed without complete legal authorization [

59]. Due to varying years of official recognition, not all were mapped. These reserves are distributed across the Nasarawa North, South, and West Senatorial districts (

Figure 2.1), with the majority located in the southern region, followed by the northern and western areas. They were officially recognized under the Benue Plateau State of Nigeria gazetted supplement part B to N.R gazetted No.8 vol. 2, 1966. While local residents were prohibited from clearing vegetation, forest communities retained the right to access resources while maintaining the forest cover. They could gather water, thatching grass, dead wood, stones, fruits, and medicinal plants important to their culture. However, resource extraction was restricted to personal domestic use and not for commercial purposes, ensuring no harm to the vegetation cover [

59]. Three forests- Doma, Risha, and Odu were chosen to represent each geopolitical zone: Doma in the south, Risha in the north, and Odu in the west (

Figure 2). This selection ensures a comprehensive approach by encompassing ecological zones, cultural landscapes, and socioeconomic activities. Doma Forest is characterized by rich biodiversity, tropical trees, and wildlife. It holds cultural importance for indigenous communities engaged in traditional farming and fishing, with riverine and lowland forests bolstering local economies (55, 35). The community is ethnically diverse, with the Alago-speaking tribe being predominant. Risha Forest, located in the northern study area, serves as a transition between savanna and woodland ecosystems. It supports agricultural and grazing activities for pastoralist communities and acts as a barrier against desertification, sustaining local economies [

35,

54]. The Mada ethnic group is predominant in this area, although other groups are also present.

Nasarawa State is home to 41 officially recognized forest reserves (

Figure 2), which were established and charted in 1966 with legal documentation, although some were proposed without complete legal authorization [

59]. Due to varying years of official recognition, not all were mapped. These reserves are distributed across the Nasarawa North, South, and West Senatorial districts (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), with the majority located in the southern region, followed by the northern and western areas. They were officially recognized under the Benue Plateau State of Nigeria gazetted supplement part B to N.R gazetted No.8 vol. 2, 1966. While local residents were prohibited from clearing vegetation, forest communities retained the right to access resources while maintaining the forest cover. They could gather water, thatching grass, dead wood, stones, fruits, and medicinal plants important to their culture. However, resource extraction was restricted to personal domestic use and not for commercial purposes, ensuring no harm to the vegetation cover [

59]. Three forests- Doma, Risha, and Odu were chosen to represent each geopolitical zone: Doma in the south, Risha in the north, and Odu in the west (

Figure 2). This selection ensures a comprehensive approach by encompassing ecological zones, cultural landscapes, and socioeconomic activities. The selected process also considered ecological similarity, cultural significance, and geographic distribution, representing various ecological zones and forest types of different sizes with comparable biodiversity [

35,

54,

55].

Figure 2 illustrate the 1966 forest boundaries for the state, and the selection of forest sites took into account security threats, including kidnapping, farmer-herdsmen conflicts, inter-community crises, and cultural barriers. Prior to field visits, consultations were held with the Nigeria security services at the state divisional headquarters in Lafia, the capital of Nasarawa State, to obtain relevant security information before travelling to the area, making our final selections and data collection.

2.1. Data Source and Methodology

The study employed a mixed-methods research design [

60,

61], combining household surveys, key informant interviews (KII), and focus group discussions (FGD) to understand the perceived historical drivers and human activities that contribute to the trajectory of the gazetted forest reserve change in the study area. The data collection process involved a household survey, stakeholder interviews and focus group discussions (

Table 1).

2.1.1. Household Survey

The survey comprised a set of structured questions, which were specifically designed to gather insights from the local community living near the forest reserves. The primary goal of the household survey was to capture a comprehensive range of perspectives from the targeted gazetted forest communities. The household survey was purposefully designed to survey a large population; ultimately, data were collected from a total of 252 respondents (

Table 1), providing a robust basis for analyzing the communities’ views. It was nevertheless difficult to obtain precise figures and data on the villages and communities surrounding the forest reserves, which resulted in challenges in establishing what was a valid sample. Since the study area's population was unknown, multi-stage sample approaches were used to choose household survey respondents [62, 63). This involved selecting respondents through a series of stages, typically narrowing down from larger, more general groups to smaller, more specific groups.

Three communities within each selected forest reserve area were chosen from a list of all the communities in the Local Government Areas. Doma forest villages included Doma, Dogon Kurmi, and Yelwa Doma. Risha forest selected villages were Risha, Nggazu and Tidde Rinze while the Odu forest villages were Karmo Mission, Karma Sabo and Karm Oguwa. The household survey was conducted during June and July 2022 in the wet season. As some of the participants could not adequately read and write in English, questions were translated into the Hausa language with assistance from the field research team. All participants were adults (over 18 years old), and their informed verbal consent was obtained. The data collectors spoke directly with respondents at the point of collection. However, measures were taken to ensure the confidentiality of the data.

Three research assistants were recruited and trained on standardization of procedures, diverse perspectives in identifying and clarifying any subjective interpretations. This enabled a balanced approach and shared understanding of data collection protocols to minimize bias and ensured data was collected in a consistent manner. The household survey was administered face-to-face in English and Hausa when required, with respondents’ answers recorded in hard copy.

The activities of the research assistants were supervised by the first author. Since some of the respondents agreed to be contacted by giving their phone numbers, a random sample of participants across six villages was called to verify if they participated. The responses from the participants were tallied with the hardcopy household survey completed by the research assistants. The research field team met together every day, both before and after the data collection, to reconcile, back up, and discuss any challenges that arose in the field activities.

2.1.2. Key Informant Interviews (KIIs)

Key informant interviews were conducted to gather in-depth insights from individuals with significant knowledge, experience and expertise related to forest use, management, and conservation. A total of 40 stakeholder participants were recruited for KIIs using the snowball sampling method, with the help of the community heads and local contacts.

The local community groups were selected based on their experience with forest resource use, their understanding of land use change, and their active involvement in forest-related activities (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Semi-structured interviews were conducted in English and Hausa, allowing participants to share their perspectives on the drivers, human activities, and benefits of ecosystem services provided by the gazetted forests. Hausa responses were later translated into English for analysis. These interviews provided valuable qualitative data to understand the complexities of historical drivers and human activities from the local communities around the gazetted forests area.

2.1.3. Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

To complement the household surveys and key informant interviews, eight focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted with community members from the same stakeholder groups who participated in the KIIs (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted to foster deeper engagement and dialogue, enabling participants to share communal perceptions, experiences, and evaluate the historical drivers and their trajectory of human activities to lead to the gazetted forest reserve change and the decline of conservation of forest ecosystem services. The same participants from the Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were invited to participate in the FGDs, ensuring continuity and cost-effectiveness in participant recruitment. Their prior familiarity with the topic facilitated deeper engagement, allowing for the validation and triangulation of findings. This approach proved valuable for understanding community dynamics, social norms, and areas of stakeholder consensus or divergence.

The discussions were conducted in both English and Hausa to accommodate participants’ language preferences. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for audio recording. Field notes were also taken to capture non-verbal cues, contextual factors, and other relevant observations. This strategy provided a comprehensive dataset, which facilitated a detailed and nuanced analysis of the participants’ responses. Audio recordings were subsequently translated from Hausa into English and transcribed for analysis. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Environment and Geography Department Ethical Review Committee at the University of York, UK, prior to the commencement of the research.

2.2. Data Analysis

Data were analysed using statistical packages for social science (SPSS) Version 21 and NVivo was used to generate descriptive statistics, code themes and extract relevant narrative data analyses. The process started with the use of Microsoft Excel to create spreadsheets to facilitate the creation of a structured database of variables, allowing for the systematic entry of information. This included entering the quantitative data collected from the household questionnaires. The descriptive statistics were generated in SPSS, and Python software was used to generate bar graphs and analysis summarised in tables and figures, providing a comprehensive report of all quantitative information.

The qualitative data derived from Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were coded and analysed using NVivo software. This process was conducted in two stages. The initial stage of coding produced numerous categories without limiting the number of codes, in line with the grounded theory approach proposed by Charmaz [

63] and further elaborated by Ganesha [

62]. Emerging ideas were identified, relationship diagrams were developed, and frequently cited keywords were utilised to formulate key themes aligned with the study's research objectives. In the second stage, the initial codes were refined through the elimination, amalgamation, or subdivision of categories, with emphasis placed on recurring concepts and broader thematic patterns [

63]. Direct quotations from participants, as extracted through NVivo, were employed to substantiate and support the narrative within the research storylines, based on the categories underpinning each theme.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the community household survey, KII and FGD on perceived historical drivers of gazetted forest changes and human activities around the three forest reserves (Doma Risha and Odu) in Nasarawa State.

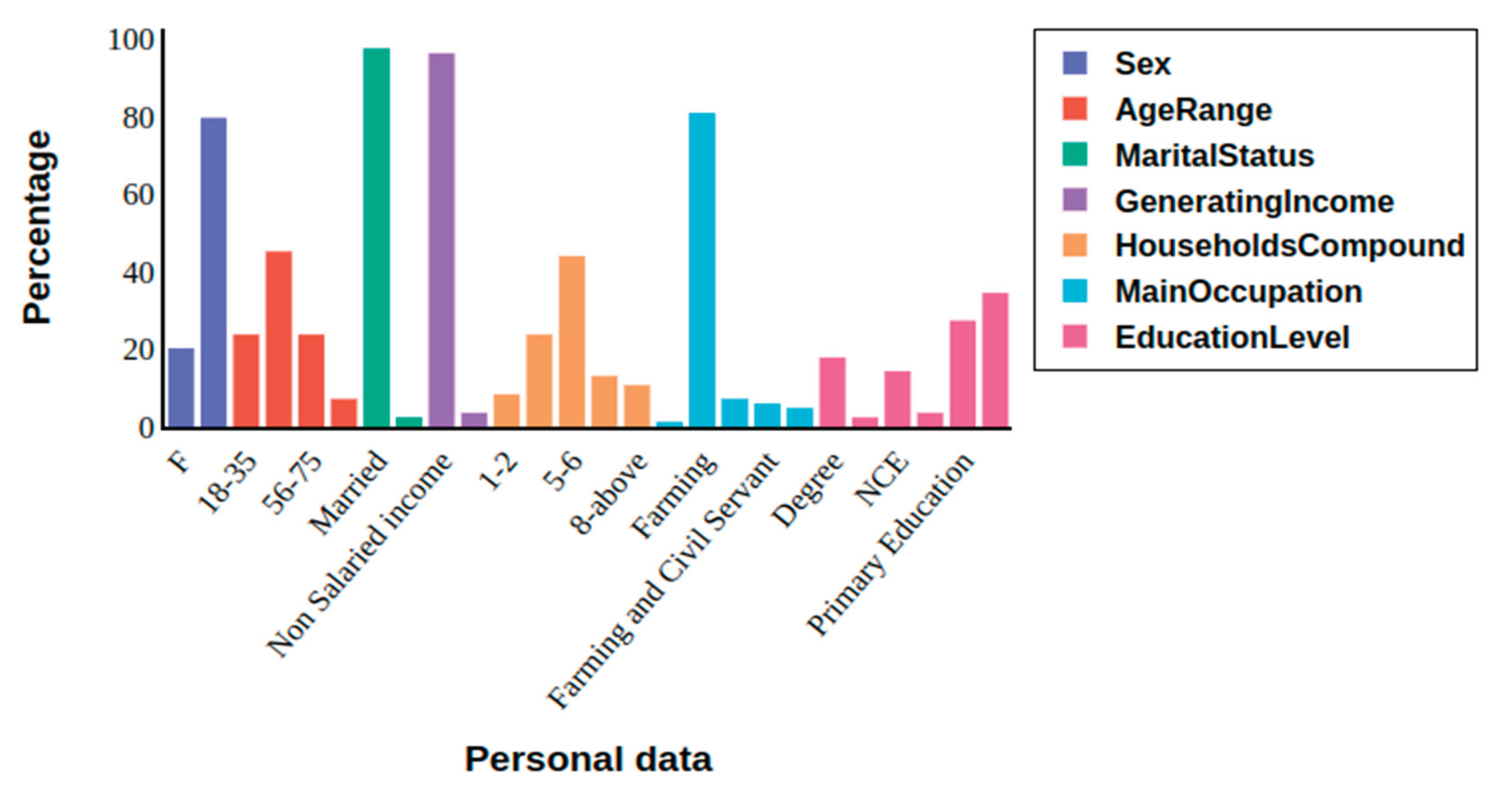

3.1. The Household Survey Respondents on Socioeconomic Responses from the Gazetted Forest Change Across the Three Study Forests in Nasarawa State

A socioeconomic survey conducted among 252 respondents around forest reserves of the study area indicates that 80% of the participants are male, with a predominant age range of 18–55 years (69%) (

Appendix A Figure 1). The majority possess secondary or tertiary education, although a portion has limited or no formal education. Notably, 95% of the respondents earn non-salaried incomes, with 65% earning less than N60,000 (USD 40) per month. Farming is the primary livelihood for 81% of the respondents, supplemented by civil service and trading, with a substantial reliance on forest resources for subsistence. In the regions of Doma, Risha, and Odu, the proportion of non-salaried income earners is 98%, 96%, and 90%, respectively, indicating that agricultural activities are most prevalent in Risha and Doma (81%). Commonly cultivated crops across the three study forest areas include yams, maize, cassava, and Guinea corn, with Doma exhibiting greater crop diversity.

These findings underscore the widespread poverty and informal livelihoods, highlighting the significant pressure exerted by high forest dependence on human activities within the communities surrounding the gazetted forest reserves. This emphasises the necessity for integrated forest reserve governance and sustainable development strategies.

3.2. Households’ Perceived Responses of the Drivers and Human Activities That Affect the Gazetted Forest Change in the Three Forests (Doma, Risha and Odu) in Nasarawa State

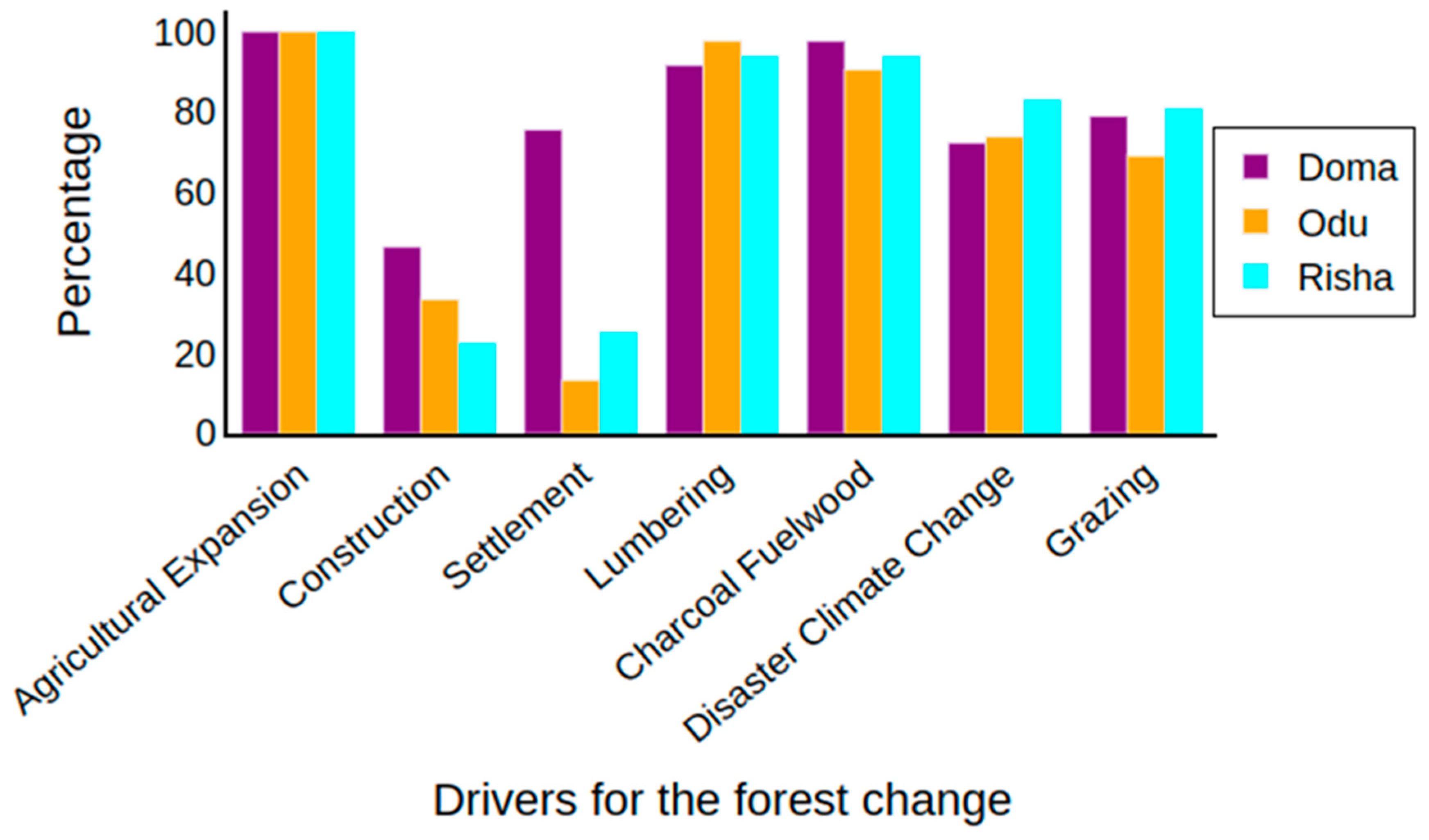

The results of the household survey of the community perceptions of the drivers and human activities that contribute to the gazetted forest reserve change in their community are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Multiple options were given to the respondents so they could select any number of possible drivers of the change. In terms of direct drivers, all respondents identified agricultural expansion and lumbering across the three forests. Fuelwood/charcoal production was another top driver of forest change. Other drivers were natural disaster/ climate change, grazing, settlement, and construction across the three forests (Doma, Risha and Odu (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

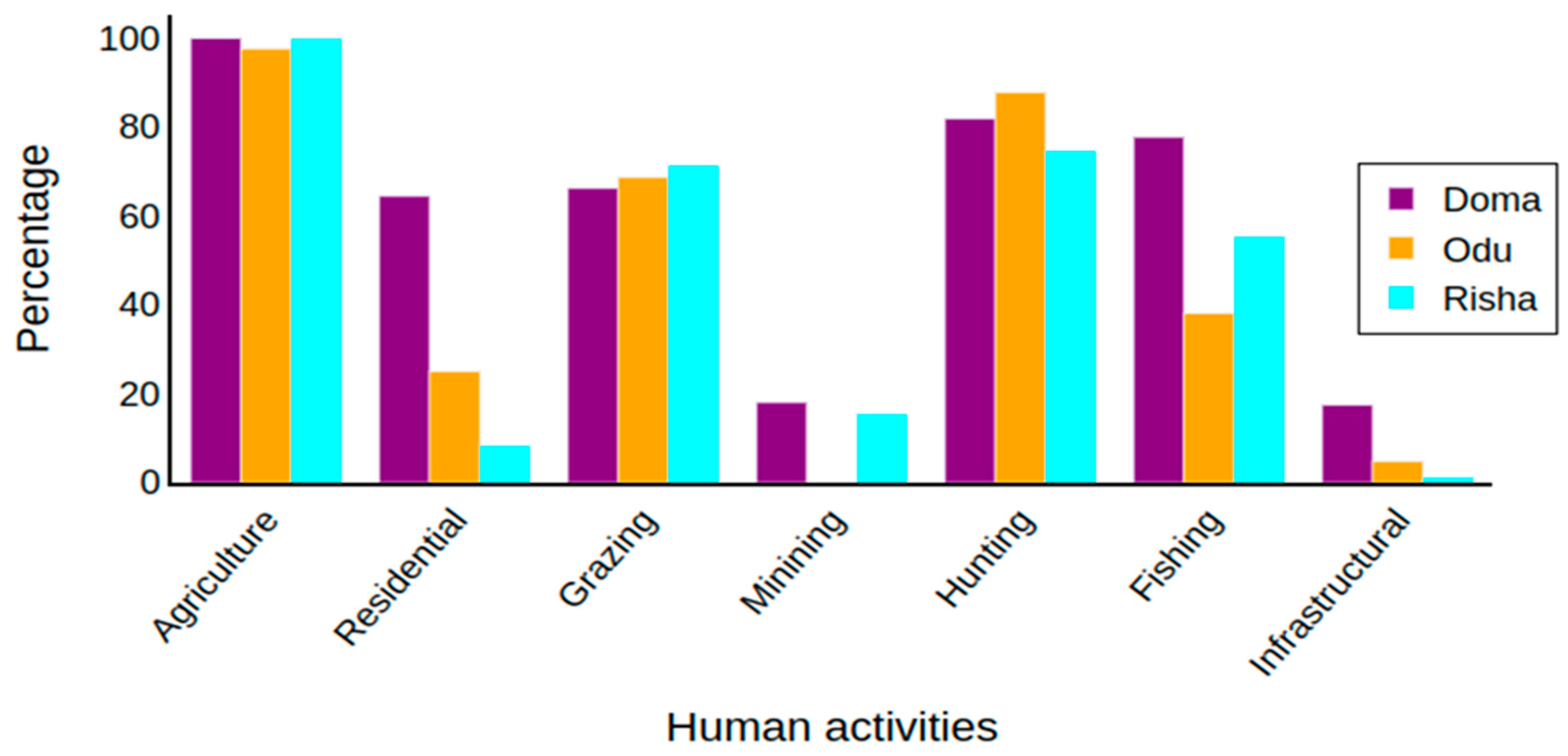

To understand more details on the human activities that led to the change of the gazetted forest in the study area, the household survey further evaluated local community activities around the gazetted forest communities (

Figure 4). This also was to relate their perception of the drivers and human activities in the area. Respondents identified agriculture, grazing, hunting, residential, mining, fishing, and infrastructural development as human activities around the gazetted forest area which influence the drivers that cause the changes in the gazetted forest across the three forests in the study area.

3.3. Comparison of (Households’) Perceived Responses of the Drivers and Human Activities That for the Gazetted Forest Change in the Three Forests in Nasarawa State

The comparative result of drivers of the LULCC in the three gazetted forests is shown in

Figure 3, and that of human activities is presented in

Figure 4. All the respondents (100%) in the three gazetted forests indicated agriculture expansion as the major driver of change, while 99% of the respondents identified agriculture as human activities (

Figure 4 and plate 1). From the household survey sample, respondents also identified grazing, hunting, residential, mining (quarry), fishing, and infrastructural development as key human activities around the three gazetted forest areas (

Figure 4). However, construction and settlement were perceived by far fewer people as driving the forest change across the three reserves. Doma had the highest construction response (47%) with Risha followed while Odu had the least (

Figure 3). 76% of respondents in Doma identified settlement as one of the major drivers while only a few in Risha and Odu considered it as a driver for forest change in the area (

Figure 3). Over 90% of respondents in all three forest reserves identified lumbering as one of the major drivers of the gazetted forest change in their communities (

Figure 3, 4). Fuelwood and charcoal production were similar in the three forest reserves with over 90%, however, this was slightly higher in Doma, with Risha next and Odu being the least among the three reserves. In terms of respondents' perceptions of disaster and climate change, more than 70% of respondents in the three forest communities (as shown in

Figure 3) agreed that these drivers had contributed to changes in their gazetted forest reserves. Grazing was a commonly identified driver across the three forest reserves noted by 81% of respondents in Risha and 79% in Doma and 69% in Odu (

Figure 3). Similarly, grazing activities were common over the three reserves, over 60% identified grazing as human activities in the survey (

Figure 4). Other findings comparing results linked to perceptions of hunting, mining, fishing are presented in

Figure 4.

Plate 1. Evidence of identified land use activities around the gazetted forest reserves in the study sites. From top right: ai, ii) clearing primary forest land for agriculture activities and settlement in Odu Forest; bi, bii) Agriculture cultivation and fuelwood cultivation in Doma forest; ci, cii) clearing of forest area for farming activities and cultivation in Risha forest reserve; di, dii) show grazing activities in Doma and construction along Risha forest reserves. Sources: Fieldwork July, 2023.

This comparative analysis sheds light on the multifaceted nature of human activities and the drivers within the three gazetted forest reserves in Nasarawa State. The findings provide valuable insights into the varying degrees of engagement in agriculture, residential living, grazing, mining, hunting, fishing, and infrastructural development across the surveyed areas, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the human-environment dynamics in these forest reserves (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

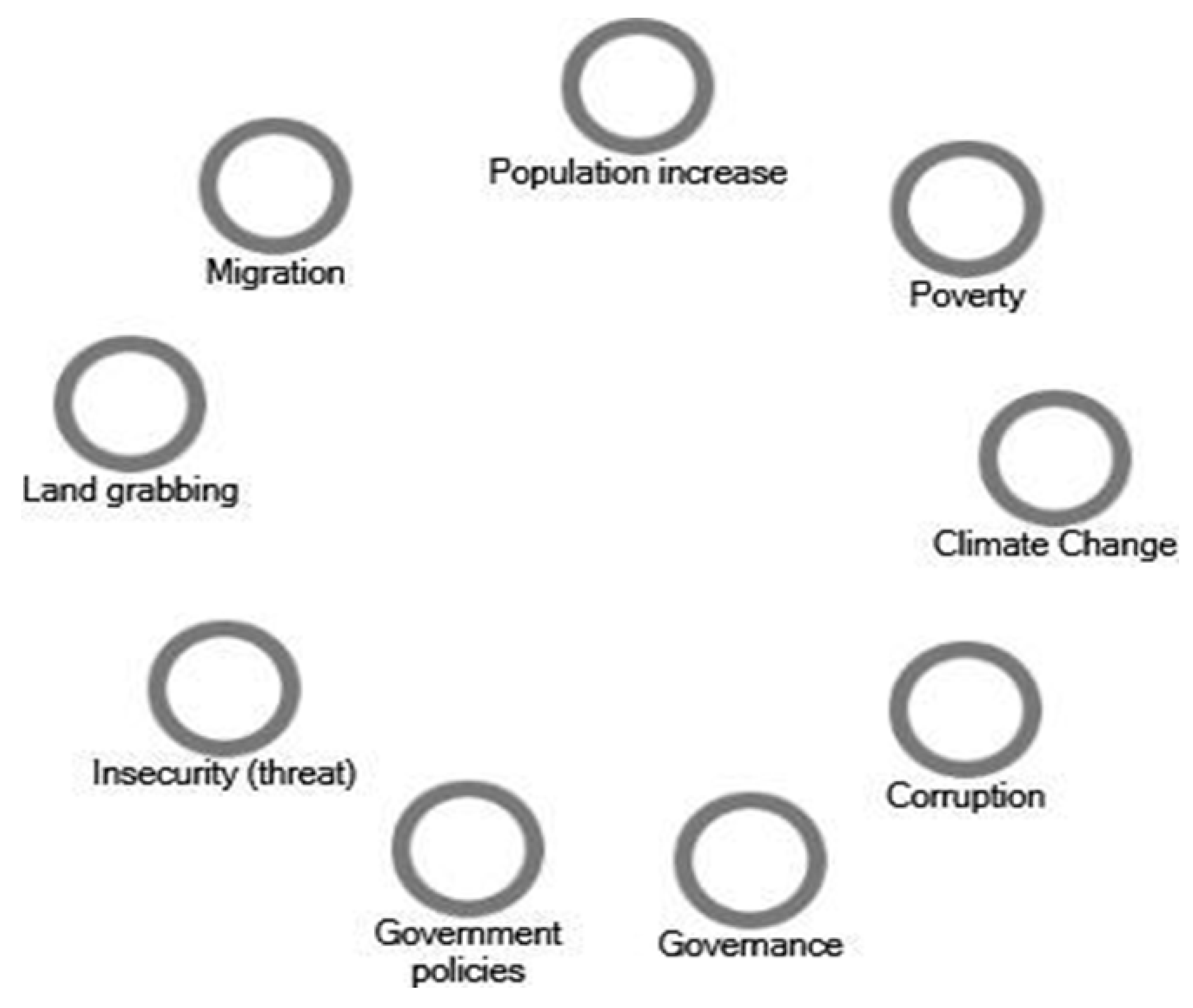

3.4. Underlying (Indirect) Drivers of the Gazetted Forest Change in Nasarawa

Themes derived from quantitative data analysis, as mapped through NVivo project coding based on KII and FGD indicate interconnected factors such as population increase, poverty, climate change, corruption, governance, government policies, insecurity, land grabbing, and migration.

Figure 5.

Nvivo mapping codes from all stakeholders across the forest sites, showing perceived underlying drivers of forest change, as collected using KII and FGDs.

Figure 5.

Nvivo mapping codes from all stakeholders across the forest sites, showing perceived underlying drivers of forest change, as collected using KII and FGDs.

These codes represent the perceived underlying drivers of forest change identified during data collection. These drivers encapsulate the multifaceted and dynamic pressures contributing to forest degradation and alterations in surrounding communities. This analysis emphasizes the systemic nature of the challenges and provides a framework for understanding stakeholder perspectives on the underlying causes of forest changes.

3.5. Community Perceived Historical Drivers of Gazetted Forest Changes and Human Activities Around the Forest in Nasarawa State: Insights from Stakeholders (1966–2022) Across the Three Forests (Doma, Risha and Odu)

Understanding the variety of factors driving forest changes over time is critical for informed forest management and conservation strategies. This section examines stakeholders’ perceptions of the historical and contemporary drivers of forest change in Nasarawa State, Nigeria, between two distinct timeframes: 1966–2000 (the past) and 2001–2022 (the present) and the trajectories for the perceived drivers, and processes of change. This section also sheds light on the interplay of socio-economic, political, and environmental factors influencing forest cover, biodiversity and ecosystem change in the three gazetted forests.

Appendix B:

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 show relevant quotes from the key stakeholders’ KII identifying perceived drivers while section 3.5.1–3.5.4. show the FGD summaries of stakeholders’ perceptions of the historical drivers of forest change trajectories and processes of change for gazetted forest reserve change.

3.5.1. Summary of Stakeholder FGD Comparative Content Analysis on the Trajectories, Perceived Drivers, and Processes of Change in the Doma Gazetted Forest Reserve Community

The local people and leaders FGD revealed that from the 1960s to 2000, Doma forest reserves were dense, biodiverse ecosystems with tall trees, vital wildlife, and minimal degradation. Between 2000 and 2022, deforestation intensified, resulting in significant biodiversity loss, wildlife extinction, and reduced forest cover. By 2022, the reserves had nearly disappeared, leaving degraded ecosystems and diminished community benefits. Both groups highlighted population growth as a major driver, leading to forest encroachment. Logging and timber extraction were significant factors, fueled by urbanization and state revenue policies. Agricultural expansion took a large permanent portion of the forest reserve mentioned by the two stakeholder groups. Community leaders pointed to charcoal production and commercial logging as key contributors, while community people mentioned government-issued orders for timber extraction. Leaders noted bushfires and overgrazing as major contributors, less emphasized by the local community. Both FGDs acknowledged extensive wildlife and biodiversity loss due to habitat destruction and hunting and emphasized neglect of management including inadequate enforcement of forest policies. On change processes, both groups agreed that population pressure and economic activities directly fueled forest clearing without reforestation. Leaders added that unsustainable grazing practices introduced invasive species and degraded the ecosystem further. Lack of enforcement, combined with local and state policy gaps, allowed extensive degradation to continue. Overall, the Doma forest reserve's decline is rooted in population pressure, agriculture expansion, economic exploitation, and policy failures, with nuanced variations between the two groups. Both acknowledged the urgent need for sustainable management to reverse the trend in the study area.

3.5.2. Summary of Stakeholder FGD Comparative Content Analysis on the Trajectories, Perceived Drivers, and Processes of Change in the Risha Gazetted Forest Reserve

From the 1960s to 2000, the Risha gazetted forest had dense vegetation, abundant wildlife, and flowing streams. Agricultural activities and human settlement were minimal, with government control preserving biodiversity. Species included lions, baboons, crocodiles, pythons, and tree species like mahogany and Terminalia spp. By 2001 to 2022, rapid forest degradation occurred due to agricultural expansion, deforestation, and near-total loss of forest cover. Biodiversity significantly declined, with many species disappearing or retreating. Open spaces replaced dense vegetation, streams dried up, and ecosystems were disrupted. Local community and leaders FGD identified key drivers: population growth and increased settlement driven by agricultural expansion into forest reserves. Deforestation for crop production converted forests into farmland. Economic pressures led to timber extraction, charcoal production, and firewood harvesting. Bush burning contributed to hunting, land clearing, and farming, causing forest destruction. Overgrazing by Fulani herders caused soil compaction, tree damage, and loss of tree cover and grassland as revealed in the two FGDs. However, it is noteworthy that Fulani herders were not included as participants in these FGDs due to their inaccessibility, which precluded the opportunity to gain insights into their perspectives regarding the impact of their activities on forest degradation.

The local community FGD revealed deforestation from logging, agricultural expansion, and firewood/charcoal extraction led to habitat destruction and biodiversity loss. This displaced wildlife, with animals fleeing and species like crocodiles, pythons, and buffalo disappearing. Cultural and economic shifts transformed forests from traditional conservation areas to sources of short-term economic gains. The transformation of the Risha forest reserve is attributed to direct and indirect interconnections such as social, economic and environmental factors that have altered the forest reserve cover, ecosystem, and biodiversity.

3.5.3. Summary of Stakeholder FGD Comparative Content Analysis on the Trajectories, Perceived Drivers, and Processes of Change in the Odu Gazetted Forest Reserve

For Odu between 1960–2000, the local community FGD revealed that forests remained largely intact due to low population density, strict traditional laws, and minimal economic reliance on forests. Wildlife and valuable tree species thrived under traditional regulation. However, community leaders noted that forest size began to reduce gradually from logging for local and commercial use, additionally driven by agricultural expansion and bushfires, while fauna and flora species started depleting due to weak enforcement. 2001-2022, the local community explained that forest degradation accelerated due to economic pressures. Deforestation was driven by timber operations, agricultural expansion, charcoal production, and bush burning, leading to habitat loss, reduced wildlife, and insecurity. Community leaders attributed the change to rapid forest degradation from population growth, poverty, and weak forest management. Overexploitation for fuel, farming, and urbanisation led to forest cover and biodiversity loss, soil erosion, and a decline in forest resilience. The community revealed that processes of change between the 1960s and 2000 were characterised by traditional forest protection systems giving way to unsustainable practices, leading to significant forest cover change and biodiversity loss. Community leaders pointed out weak governance and lack of reforestation led to unsustainable exploitation, while rapid urbanisation and reliance on forest resources due to poverty further accelerated degradation. The local community focused on unregulated timber extraction (sawmills) and shifting cultivation as key drivers, while community leaders highlighted urbanisation and population growth, poverty, and lack of effective forest governance as critical causes, also noting climate change's influence on forest change.

3.5.4. FGD Content Analysis for Government Officials and Expert Stakeholder Groups on the Trajectories, Drivers, and Processes of Change in Gazetted Forest Reserves in the Study Area

During the period from the 1960s to 2000, both Government and Expert Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) noted gradual deforestation, driven by population growth, agricultural expansion, and timber extraction. Infrastructure development contributed to forest degradation, albeit slower compared to subsequent years. Experts highlighted bushfires as a significant contributor. Biodiversity loss commenced, with declining flora (e.g., Parkia) and fauna (e.g., primates, elephants). From 2001 to 2022, both groups emphasised accelerated deforestation driven by rapid population growth, agricultural expansion, urbanisation, and economic pressures. Charcoal production, commercial timber harvesting, and mining were identified as major drivers. Experts highlighted rising energy costs leading to increased firewood and charcoal use. Both groups noted the impact of climate change, policy inconsistencies, and inadequate reforestation efforts. Faunal extinction became more pronounced, with large mammals and valuable tree species experiencing drastic declines. In summary, government officials and experts revealed that processes of change between the 1960s and 2000 were characterised by gradual degradation due to farming, timber harvesting, and infrastructure development, while 2001-2022 processes exhibited accelerated deforestation caused by expanded agricultural activities, unsustainable resource exploitation, and urbanisation. Both groups identified the interplay of population growth, economic need, and policy failures as primary drivers of forest degradation. Experts provided additional ecological insights and highlighted specific socio-economic factors as contributors to the change.

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the overview comparison, similarities and differences in stakeholder FGD insights and perspectives.

Table 3.

Overview of stakeholder perspectives for the FGD content analysis of findings on forest reserve changes and drivers.

Table 3.

Overview of stakeholder perspectives for the FGD content analysis of findings on forest reserve changes and drivers.

| Forest Reserve |

1960-2000 |

2001-2022 |

Key Drivers of Change |

Processes of Change |

| Doma |

Dense, biodiverse forests with tall trees and abundant wildlife. Minimal degradation. |

Significant deforestation, biodiversity loss, and near disappearance of reserves. |

Population growth, agricultural expansion, logging, charcoal production, bushfires, overgrazing, weak policy enforcement. |

Loss of vegetation cover, economic exploitation, lack of reforestation, Habitat destruction, invasive species, and inadequate enforcement. |

| Risha |

Rich vegetation, wildlife, and water bodies with strong government control. |

Near-total forest cover loss, ecosystem disruption, species extinction, water body depletion. |

Agricultural expansion, timber/charcoal extraction, firewood harvesting, and overgrazing. |

land clearing, Hunting, changing cultural attitudes towards conservation, and economic pressures. |

| Odu |

Intact forests with strong traditional laws limiting exploitation. |

Accelerated degradation, habitat loss, soil erosion, reduced resilience. |

Logging, agricultural expansion, urbanization, timber extraction, overgrazing, weak governance, climate change. |

Shift from traditional conservation to unsustainable exploitation, changing cultural attitudes towards conservation, population pressure, and economic reliance on forest resources |

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of the trajectories, drivers, and processes for the government and expert FGDs.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of the trajectories, drivers, and processes for the government and expert FGDs.

| Time Period |

Government and Expert Observations |

Key Drivers |

Processes of Change |

| 1960-2000 |

Gradual deforestation due to farming, timber harvesting, and infrastructure development. Biodiversity loss began. |

Population growth, agricultural expansion, timber extraction, charcoal/ fuelwood extraction, infrastructure projects, bushfires. |

Slow but steady degradation, early signs of habitat and species decline. |

| 2001-2022 |

Accelerated deforestation, faunal extinction, and significant ecological decline. |

Rapid population growth, agriculture expansion, urbanization, economic pressures, increased reliance on firewood/charcoal, mining, weak governance, and reforestation efforts. |

Unsustainable resource exploitation, policy failures, climate change impacts. |

Table 5.

Similarities and differences among stakeholders' FGDs on the perceived drivers, impacts and process of change of the gazetted reserves.

Table 5.

Similarities and differences among stakeholders' FGDs on the perceived drivers, impacts and process of change of the gazetted reserves.

| Aspect |

Similarities |

Differences |

| Time Period |

Government and Expert Observations |

Key Drivers |

| Perceived Drivers |

All stakeholders identify population growth and urbanization, agriculture, logging, and weak governance as primary drivers. |

Local communities emphasize immediate livelihood needs, while the government and experts highlight policy failures and economic exploitation. |

| Impact on Biodiversity |

All agree on significant biodiversity loss and ecosystem disruption. |

Experts provide detailed ecological insights, while local stakeholders focus on visible wildlife disappearances. |

| Processes of Change |

Generally, the consensus socio-economic (livelihood) activities accelerate deforestation. |

Government officials acknowledge policy gaps, whereas communities highlight economic survival needs. |

| Solutions & Management |

Recognition of the need for sustainable management, reforestation, and policy enforcement. |

Experts advocate scientific conservation approaches, while local leaders stress traditional conservation methods. |

The comparative stakeholder analysis highlights the stakeholder perspectives on forest reserve changes, and the narratives from FGDs across stakeholder groups underscore diverse perspectives on forest reserve trajectories, drivers of change, and processes shaping forest ecosystems across the three gazetted forest communities. Each group's viewpoint is rooted in their interaction with and reliance on the forests, as well as their capacity for control over forest resources.

Local communities and leaders depicted dense, biodiverse forests in the 1960s, gradually transforming into degraded landscapes due to population growth, economic pressures, and weak enforcement. Their perspectives blend personal experience and direct reliance on forest resources, emphasizing agricultural expansion, charcoal production, and timber extraction as primary drivers of deforestation. Community leaders also highlighted policy failures and urbanization as accelerants of forest loss, with nuanced variations in emphasis on issues like overgrazing and bushfires.

Government officials and experts provided a broader policy-oriented and ecological perspective. They aligned with local accounts of deforestation drivers but enriched the analysis with insights into the interplay between climate change, energy demand, and governance challenges. Experts, in addition, highlighted the ecological consequences of forest degradation, including biodiversity loss and species extinction, offering a systems-level understanding of socio-economic and environmental transformations.

Consistent themes emerged across all FGDs: population pressure, economic exploitation of forest resources, and governance failures were identified as central drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss. However, the analysis revealed the need for disaggregating perspectives. Local communities emphasized immediate livelihood challenges, while experts provided more long-term and systemic analyses of forest degradation. This divergence underscores the importance of considering each group's unique vantage point to design inclusive and sustainable forest management strategies. The findings emphasize the urgency of integrating local knowledge, expert insights, and governance reforms to reverse forest decline. Effective management must address underlying drivers such as poverty, urbanization, and policy gaps while promoting reforestation, agroforestry and sustainable resource use. An integrated approach that combines policy reform, community engagement, and scientific conservation is essential for the sustainable management of the Doma, Risha, and Odu forest reserves and beyond.

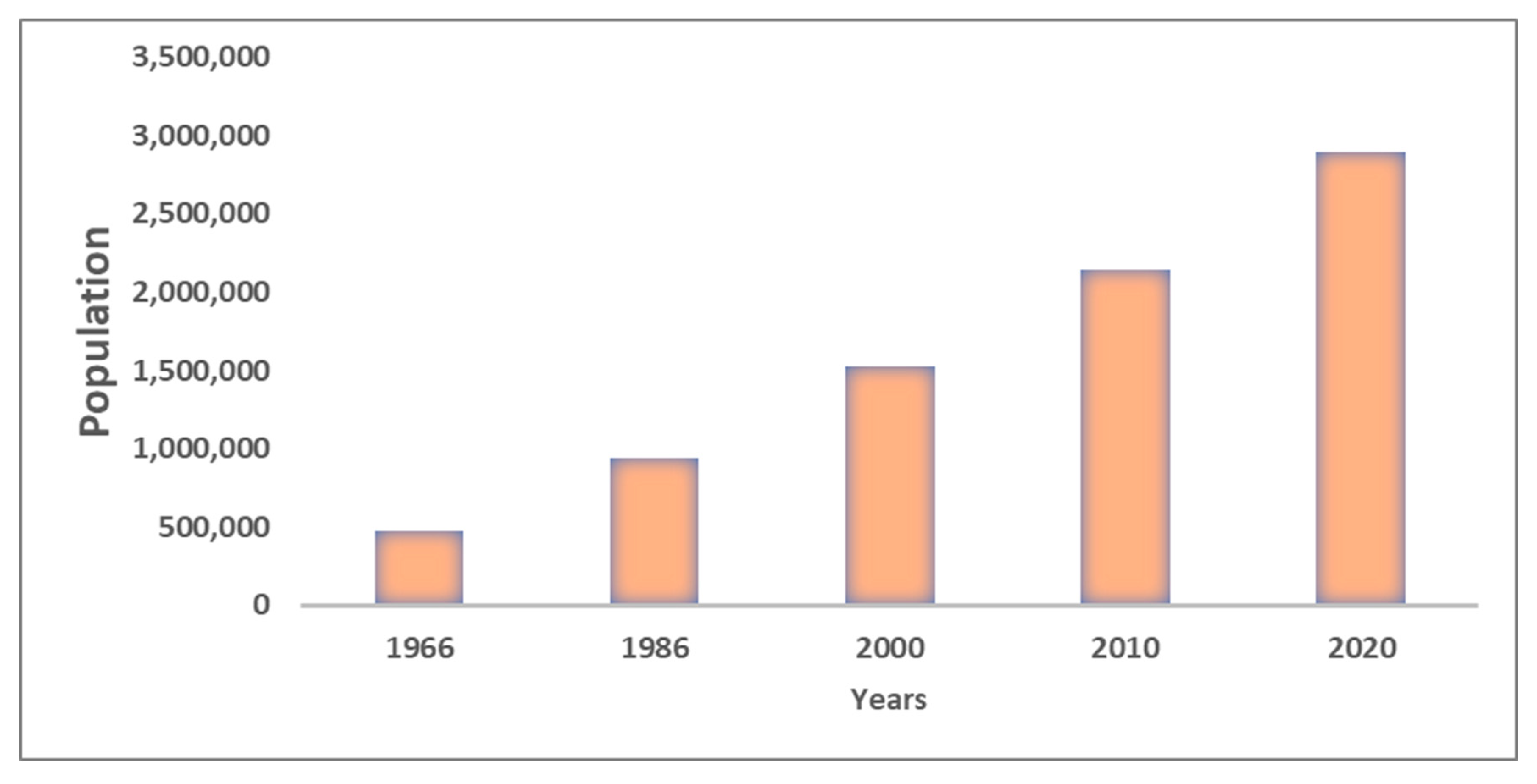

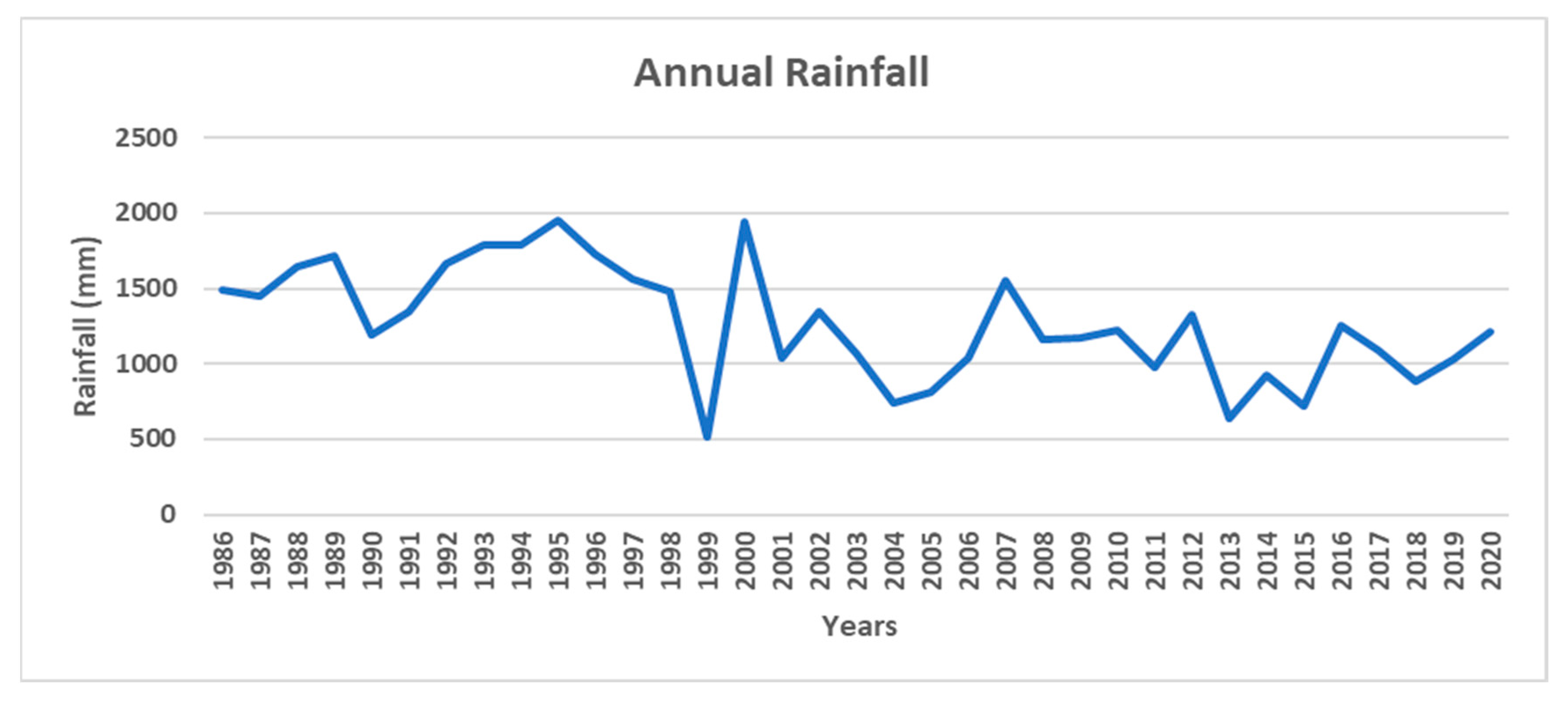

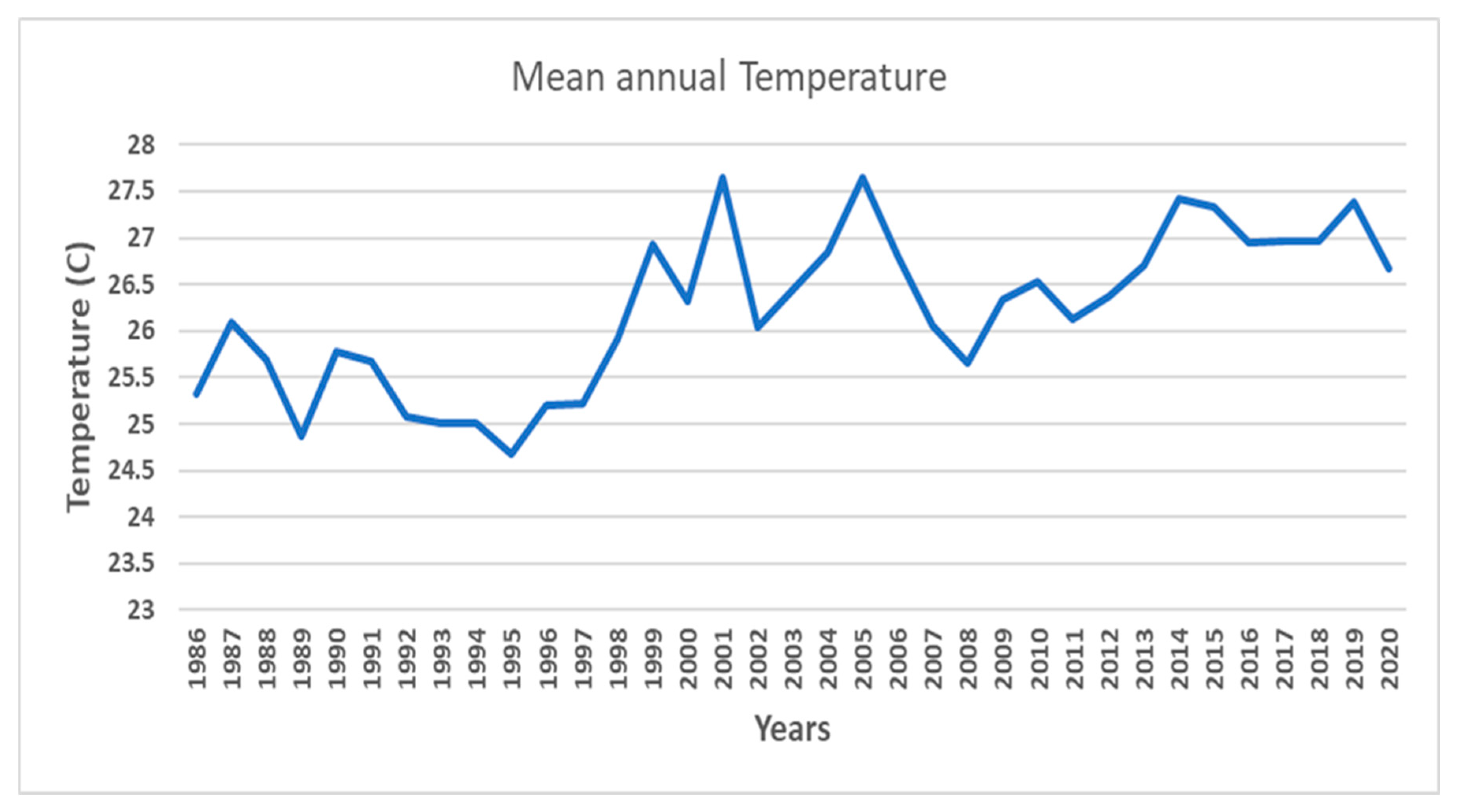

3.6. Population Growth and Climate Change Variable (Temperature and Precipitation) of Nasarawa State

To evaluate the population growth and climate variable of the study area as consistently revealed across stakeholder perceptions,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 indicate that over the years covered in this study (1986-2020), Nasarawa State has experienced significant climate variability with an overall trend of increasing temperatures and fluctuating rainfall. Simultaneously, the population has seen substantial growth, more than tripling from 1986 to 2020. These changes may have implications for the region's forest cover, agriculture activities, ecosystem services and overall sustainability of the gazetted forest reserve, and indeed, were noted by stakeholders.

3.7. Community Evaluation of Key Drivers and Human Activities Behind Changes in the Gazetted Forest Reserves Across the Three Study Areas

This section examines and evaluates the perceived primary factors (key drivers and human activities) identified and recognised by local communities and stakeholder participants across the three (Doma, Risha and Odu) forest reserves (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Data from KIIs are in

Appendix A Table 1–5; FGD Section 3.6.1–3.6.3 and

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5.

3.7.1. Doma Forest Reserve

a) Agricultural Expansion

In Doma forest reserve’s household survey, agricultural expansion was perceived by most of the respondents as the largest driver of forest cover changes. Qualitative insight from content analysis of Doma stakeholder KIIs (

Appendix B Table 1 and section 3.5.1) revealed that farming activities, initiated in the 1970s, have led to widespread deforestation, with trees felled to create farmland for crops like yam, maize, guinea corn and beans (

Appendix B Table 1 and section 3.5.1). FGDs and KIIs confirmed this trend, with participants noting that the increasing demand for farmland and settlements has driven deforestation in Doma (

Table 3, 4). Moreover, field observations in 2022 by the researcher further revealed ongoing agricultural activities in and around the reserve, contributing to deforestation (plate 1).

Overall, household survey data support the qualitative findings, indicating that agricultural expansion is the principal driver of forest loss in Doma as perceived by the community. The community describes a situation where people on the agricultural frontier actively clear land to make room for farming.

Stakeholders also observed that land is initially cleared because of valuable resources, particularly timber. Agriculture then gradually follows, degrading the forest over time. Eventually, agricultural activities rapidly occupied the cleared space permanently.

Stakeholders also noted that land is first cleared because it contains a valuable resource (timber) and the agriculture moves in behind on the processes gradually degrade the forest and agriculture moves in rapidly to occupied permanent space on the reserve between 2001 and 2020, indicating that agricultural activities influence the substantial change to the reserve area.

b) Lumbering

Lumbering is another key driver and human activity of the gazetted forest change in Doma, as shown in the household survey (

Figure 3,

Appendix B Table 1 and section 3.5.1). The KII and FGD revealed that the primary activity of lumbering is timber extraction, which is carried out through non-commercial and commercial logging by the community people and the government. The extraction of selected important tree species for both commercial and non-commercial timber purposes has targeted species such as Iroko, Obeche, and mahoganies found in the forest reserves. This could impact forest quality, composition, and size, leading to a decrease in forest cover.

Clear-cutting practices contribute directly to forest degradation, with agricultural expansion taking over areas previously degraded by timber extraction. Qualitative data (

Appendix B Table 1-4) and sections 3.5.1-3.5.4. reveal this trend.

KIIs and FGDs noted that increasing population pressures have led to higher demand for timber for construction purposes, further exacerbating deforestation within the reserve. Participants reported that clear-cutting practices and selective logging of valuable tree species have significantly altered the forest composition in Doma. For example, within the KII, a participant explained that; “The practice of timber extraction has persisted for decades of years, focusing on economically valuable tree species like Iroko, mahogany, obeche, shear butter trees. These trees have been harvested to meet the substantial demand for timber exports, serving diverse applications abroad and within local communities. This industry includes forest-dwelling individuals and private commercial enterprises, generating revenue for governmental bodies. Consequently, these logging operations have significantly altered the designated forest reserve” (Doma Local People KII 003, June 2022).

c) Fuelwood/Charcoal Production

Fuelwood/charcoal production was identified and perceived as one of the primary drivers and anthropogenic activities contributing to forest change and degradation in Doma, according to 94% of survey respondents. These activities are essential for household energy and income generation. In the qualitative results from FGD, the local people confirmed that specific tree species are harvested for fuelwood and to produce charcoal, resulting in a reduction of forest cover over time (

Appendix B Table 1 and section 3.5.1). One of the leader participants from Doma KII further elaborated:

"Local communities frequently harvest trees, such as Vitellaria paradoxa (shea tree),

Daniellia oliveri (African Copaiba balsam tree)

, and Prosopis africana, for firewood and high-quality charcoal due to their dense wood and high calorific value. This targeted harvesting has significantly contributed to the depletion of forest cover and resources in the reserve, driven by domestic use and economic necessities" (Doma, local community leader KII 004, June 2022). Observations during fieldwork confirmed the ongoing exploitation of the forest for fuelwood, which aligns with household survey, KII and FGD findings (Plate 1).

d) Grazing

Grazing by livestock, particularly cattle and cows was perceived to be a driver that contributed to forest degradation in Doma as identified by 81% of respondents (

Figure 3, 4). FGDs revealed that herdsmen allow livestock to graze on croplands and grasslands and cut some specific tree species to feed their livestock within the reserve, which reduces forest cover and grassland composition. Cattle trampling and cutting of branches for fodder further exacerbate the problem. Additionally, herders have been reported to clear forested areas to build camps, adding to deforestation pressures noted by both the local people and leader stakeholders (

Appendix B Table 1 and section 3.5.1). The KII participants from the local community in Doma elaborated and further confirmed that

"Grazing by herdsmen contributes to the destruction of the forest reserve; they move into the forestry area and cut down the trees and grasses to feed their animals', this reduces the composition and size of the forest reserves; their activities affect forest growth and cover" (Doma, Community people KII 003, June 2022),

Appendix B Table 1.

3.7.2. Risha Forest Reserve

The results of the household survey in Risha considering perceptions of the drivers and human activities that contribute to the gazetted forest reserve change in their community are presented in

Figure 3,4.

a) Agricultural Expansion

In Risha forest reserve, agricultural expansion was perceived by most of the respondents as one of the substantial drivers that influence the forest cover change in the area. This was cropland expansion observed to expand and cover permanent areas of the reserve (fieldwork, 2022). Qualitative insight from the stakeholders (

Appendix B Table 2 and section 3.5.2) revealed that by 2001 to 2022, rapid forest degradation had occurred due to agricultural expansion and near-total loss of forest cover in this forest reserve, as observed during the fieldwork.

Local community and community leaders participating in KIIs and FGDs reported that agricultural expansion began several decades ago and remains a critical driver of deforestation and the forest cover change in Risha. Agricultural expansion is a primary driver of major changes in forest areas, directly leading to the permanent conversion of forests into agricultural land. This process involves communities clearing forests to create new cropland and expand settlements, with cropland almost entirely replacing the reserve's original forest cover before other factors contributed to further changes. For example, one of the participants further reiterated that

“The forest reserve has changed due to agriculture expansion because we are farming there. We farm crops like yam, groundnut, melon, maize, guinea corn, beans, and soya beans and so on” (Risha Local leaders KII 001, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 2 and section 3.5.2). The local community stakeholders' insights from the FGD further elaborated on how cropland expansion on the forest reserve was observed from the initial stage and the characteristics behind the change (

Section 3.5.2).

b) Lumbering

The household survey identified lumbering as a major contributor to forest decline in Risha (

Figure 3). The qualitative data from the content analysis revealed that a large number of trees were degraded for timber extraction for construction and other uses, leading to significant forest loss in Risha. Selective logging of valuable species like Gmelina, Obeche, Mahogany and Iroko has reduced forest quality and composition. These species are selectively logged due to their economic and commercial value, though they cause excessive exploitation that leads to deforestation and loss of biodiversity in the reserve. FGD participants (

Table 3 and section 3.5.2) further noted that as the population grows, the demand for timber increases, driving unsustainable logging practices in the reserve, one of the key contributors to forest decline in Risha. One of the local stakeholders reiterated that:

"Lumbering is one of the key contributors to human activities that lead to the degradation of the forest reserve in this area. People are often felling or cut down trees in and around protected forest areas, particularly to obtain timber for construction materials such as roofing houses. Over time, this persistent practice not only depletes tree populations but also undermines efforts to maintain the ecological balance and biodiversity within this reserve” (Risha, Local people KII 004, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 2 and section 3.5.2)

c) Fuelwood/Charcoal Production

Fuelwood/charcoal production was perceived as one of the critical drivers and human activities for livelihoods in Risha, with 90% of household survey respondents acknowledging their role in forest cover change and degradation. The qualitative results from FGD elaborated that the communities cut down trees from the reserves which are the sources of their energy use at home and also they sell them for their economic gain as a source of income for their families. Community leaders confirmed that tree cutting for fuelwood/charcoal production is a common practice, reducing the forest’s ecological integrity (

Table 3 and section 3.5.2). A KII participant reiterated this perspective, stating;

“Most of our people “indigenes” cut down trees to produce charcoal and firewood; also, the trees provide us with construction materials which we construct our houses and also sell to generate income for ourselves and our families, and I think it could be a crucial driver for the gazetted forest reserve changes” (Risha Community Leader KII 004, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 2 and section 3.5.2). Observations during fieldwork in 2022 revealed active woodlot and charcoal production sites around the reserve (Plate 1).

d) Grazing

Grazing activities in Risha were perceived to have notably impacted the forest reserve as identified by a large proportion (90%) of the respondents (

Figure 3, 4). Qualitative insight from the FGDs for both the local people and the community leaders highlighted that cattle graze on remaining cropland stalks and grasslands within the reserve, which diminishes forest cover, trees and grassland cover. Livestock overgrazing causes new trees not to regenerate and compacts the soil, while tree cutting for fodder further reduces forest composition. Both the stakeholder groups emphasized the challenges posed by herdsmen clearing trees for grazing purposes and building camps within the reserve, which trigger the fast loss of forest cover within the reserve areas. For example, one of the stakeholders from the community in Risha KII further added that

: “Fulani herdsmen's livestock grazing practices, including overgrazing causes overgrazing on grasslands and damages regenerated trees, trampling on soil by compaction and destruction of tree roots by trampling and cutting down trees for fodder and camp construction, significantly contribute to forest degradation within this forest reserve” (Risha, Local people KII 002, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 2 and section 3.5.2)

3.7.3. Odu Forest Reserve

The results of the household survey for Odu gazetted forest community perceptions for the drivers and human activities that contribute to the gazetted forest reserve change are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 and the qualitative results are presented in (

Appendix B Table and section 3.5.3). The respondents perceived agricultural expansion, lumbering, and fuelwood/charcoal production as higher among the other drivers (100%, 90% and 80%) respectively, however they also perceived natural disasters/ climate change, grazing, settlement, and construction to contribute to the change (

Figure 3, 4).

a) Agricultural Expansion

Agricultural expansion was perceived as the prevalent driver influencing forest change in the Odu forest reserve by most respondents from the surrounding forest communities (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). According to qualitative information from FGD (

Table 3 and

Section 3.5.3) farmers were practising shifting agriculture as a traditional way of agriculture by increasing farmland on existing established farms left over the years that followed, cultivating crops such as yam, maize, beans, and cassava, contributing to forest clearing and change in the reserve. Furthermore, the FGDs for both the local community and local leaders revealed that agricultural land expansion, with shifting cultivation (agriculture) driven by population growth and livelihood needs, influences changes in the reserves, including biodiversity loss (

Table 3, section 3.5.3). More also, in a KII, one of the participants further that:

"Agriculture has contributed to forest changes here since 1970s, as we depend on farming and forest resources for income and survival, with no alternative livelihoods" (Odu, Local Community People, KII 003, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 3)

b) Lumbering

Timber extraction and logging has also contributed to deforestation and forest cover loss in Odu as a driver (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The qualitative data revealed the trend, with participants reporting extensive logging of species like Obeche, opepe, African Copaiba, Iroko and Mahogany for construction and furniture making (

Appendix B Table 3 and

Section 3.5.3). KIIs and FGDs highlighted that increased demand for timber in the growing population has intensified forest exploitation. This has reduced the availability of valuable tree species and altered the reserve’s ecological balance. Community leaders in FGDs (

Table 3 and

Section 3.5.3) noted that the forest size began to reduce gradually from logging for local and commercial use, additionally driven by agricultural expansion and other drivers. In a KII, another participant from the local community added that “

Trees like mahogany, iroko and so on, I don’t know their names, were selected and massively cut out for timbers for houses, roofing and other constructions, affecting tree cover in the forest and even wild animals and other valuable trees, now hardly you seem them in the forest” (Odu, Community People, KII 002, June 2022).

c) Fuelwood/Charcoal Production

Fuelwood/charcoal production contributed a considerable role in the gazetted forest degradation and change perceived by a substantial numbers of household survey respondents in Odu (

Table 3, 4). Community leaders in FGD confirmed that many residents rely on these activities for energy and income generation. Specific tree species are targeted for charcoal production, which has further reduced the forest’s size and composition (

Table 3 Section 3.5.3). In a KII, one of the participants further elaborated that:

“Some of our people cut down trees for firewood and charcoal, targeting specific trees, which has depleted forest covers and resources from this reserve. For instance, tree species such as Vitellaria paradoxa

(commonly known as shea tree), Daniellia oliveri

(African Copaiba balsam tree), and Prosopis africana

are frequently harvested for high-quality charcoal due to their dense wood and high calorific value. The widespread cutting and burning of these trees for charcoal for domestic use and economic gain” (Odu, Local Community People K II 005, June 2022)

Appendix B Table 3.

d) Grazing

Grazing was perceived as one of the key drivers and human activities that affected change in forest cover in the Odu forest by over 69% of household survey respondents (

Table 3), although the impact appears less severe compared to Doma and Risha from the community stakeholders' narrative. FGDs reported that Fulani herdsmen rearing livestock such as cattle and cows overgraze the land, trampling of soil and young regenerating trees, and the cutting of trees for fodder contribute to forest degradation. Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) reported that Fulani herdsmen, while rearing livestock such as cattle, contribute to forest degradation through overgrazing, trampling of soil and young regenerating trees, and the cutting of trees for fodder. One of the participants from the KII (

Appendix B Table 3) further revealed that

“Animals have been grazing around the reserve by Fulani [Herdsmen]

over the parcel of land within the forest reserve area. The cattle and cows’ footsteps are overstepping the forest by feeding on the grass within the reserve area and cutting down branches of trees for their animals to feed on, and at times they even cut down the trunks for grazing purposes. Again, they cut down the trees to build their camps (houses), and now they are even going to the roots to uproot the trees (Odu, Local people KII 001, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 3 and section 3.5.3)

3.8. Evaluation of Underlying (Indirect) Drivers of the Gazetted Forest Change in Nasarawa State

In addition to direct drivers that lead to the forest change, the KII and FGD revealed underlying (indirect) drivers of land use and gazetted forest reserves change in the study area, identifying population growth, poverty, government policies, poor governance, and corruption which are similar across the three forest reserves (

Figure 5,

Appendix B Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–4). Other indirect drivers are climate change and disasters (unreliable rainfall and temperature). The results are shown in

Figure 5, from the NVivo mapping across the themes and

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The details of some of the key indirect drivers are discussed as follows.

a) Population growth

The majority of the KII and FGD participants from the local people, leaders, government officials and experts perceived the population of the area had increased over the studied period, thereby influencing human activities, particularly agricultural land expansion on the reserves, with the interaction of other drivers such as settlement which led to high demand for timber and other forest resources in the area. The population trend of the state had shown a significant increase for the period covered by this study (

Figure 6). The increasing population pressure leads to increased demand for farmland, placing increasing demands on forest resources and increasing activities that lead to forest change. FGDs and KIIs confirmed that population increase in the area influences the direct drivers that led to a significant change in the forest reserves (

Appendix B Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–3.5.4). For example, a stakeholder participant stated that “

Population growth has significantly impacted forest cover and ecosystem change, interacting with other environmental pressures and direct drivers. For example, the demand for livelihood sources is influenced by population growth. Prior to 1960, the population that led to extraction and degradation remained low. However, since 2000, deforestation has escalated, largely driven by rapid population growth within the state and local communities” (Doma Local people, KII 002, July 2022). Another participant further explained in Risha that

“Due to population increase around this area, people started claiming ownership and open agricultural land for farming purposes around 1998 to date that led to significant forest cover change of the forest reserves area” (Risha forest, Local person 003, (Female) KII July 2022). One of the expert stakeholder participants added that “

Due to the consistent ever-increasing human population in this area, it results in increasing demand from people for other land use and human activities for livelihood, which is the key driving force of the forest change" (Expert KII 004, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–3.5.4)

To confirm the community’s perception of population growth, the study area population data from 1986 to 2020 was analysed (

Figure 6). The population experienced a substantial growth of 75% between the years 1986 and 2020, rising from 939,471 to 2,895,432 individuals, with this rapid growth driven by birth rate trends and migration. During this period, the average annual increase was 2.5 % (

https://www.nationalpopulation.gov.ng). The consistent rise in the population depicted in

Figure 6 over time demonstrates this growth trend, remaining apparent despite the unavailability of precise statistical population data for the gazetted forest community.

b) Poverty

Poverty was one of the underlying drivers mentioned in the study area that influenced the land use and forest change in both the KII and FGDs across the three forest reserve areas. This was corroborated with demographic characteristics from the household survey (

Appendix A,

Figure 1,

Table 1–4). Many of the gazetted forest communities are farmers and villagers living in low socioeconomic conditions, which made them dependent on forest resource as a means of attaining a livelihood, which in turn, exerts pressure on the resource and leads to changes in the forest reserves. The KII and FGD participants explained this underlying driver in detail (

Appendix B:

Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–5.4). For example, in Risha forest reserve, one of the participants stated that

“Poverty is one of the major drivers that led to changes in the forest reserves: we expand our agricultural land in the forest to get our livelihood since we have no good way of getting food or money to survive” (KII Risha Local person 005, June 2022). Moreover, a community leader in Doma emphasised that

“Poverty is a significant driver of changes in the forest reserve. People exploit this forest to sustain their livelihoods and meet economic needs, with community members often clearing parts of the forest to access and utilize its resources” (KII Doma Local person 005, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–5.4). One of the participants further explained the government's understanding:

" One of the main reasons for changes to the forest reserve is poverty and this is a fact. The fact is that community members need money for their livelihoods and economic survival, which leads them to clear the forest around them for resources access and use” (KII Government official 005, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 4 and section 3.5.1–5.4). In addition, the household survey (

Section 3.1,

Appendix A,

Figure 1) showed that the individual households in the study communities rely predominantly on non-salaried sources of income, with a substantial proportion earning insufficient income. The study's findings indicated that many of the respondents were farmers who did not have reliable sources of income to supplement their monthly earnings and sustain their livelihoods. This is consistent with the participants' statements, who highlighted that poverty in the study area is a contributing factor to the overexploitation of forest resources in the absence of alternative means of subsistence. This conclusion is supported by the KII and FGD content analysis presented in (

Appendix B Table 1–4 and sections 3.5.1–5.4). Poverty has also increased the rate of deforestation and forest degradation in the study area due to increased demand for fuelwood and other domestic uses in the study area as reported by the local community findings in this study. This is because these communities are heavily dependent on natural resources to meet their daily needs. The forest is therefore frequently subject to unsustainable exploitation due to the heightened demand for woodfuel for use and generating income and other forest resources that are essential for their immediate survival and economic stability.

c) Poor Governance/policies and corruption

Poor governance was among the hurdles limiting the success of conserving forests and their associated biological diversity in the study area and contributed to the decline in forest reserves as identified by many participants from the KII and FGD across the three forest communities (

Appendix B Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–5.4). Poor governance includes issues such as corruption and embezzlement of funds, which have adversely affected the performance of the forest conservation sector. This is exemplified by the detrimental consequences of management and monetary issues, as well as the accelerating violation of natural resource conservation laws among others, which greatly influence the changes in the forest reserves of the area. This was particularly the case in Doma where community leaders reiterated this problem. For example, one of the stakeholders revealed that

“Before now, government do take good care of the reserves but now less attention is given, so people go into the reserves and cut down trees in the reserve any time without any taken proper permission” (Doma local people KII 005, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 1).

Poor governance for instance can affect the policy implementation that contributed to the change of the gazetted forest in the study area. Government policies governed the establishment of the PAs and forest reserves which were intended to help reduce the overall forest loss and degradation, limiting the areas in which concessions could be granted. However, many of the PAs and reserves were poorly managed and limited in resources and capacity due to the policy's failure in terms of implementation. This affects other drivers that interplay and that contribute significantly to the gazetted forest reserves in the study area, as explained by the participants in the KII and FGD (

Appendix B:

Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–5.4) across the stakeholder groups. For example, a government participant stated: “

Government policies are often contributing to deforestation in forest reserves. This is because these policies are not always implemented in a manner that aligns with the needs of the people for conservation. For instance, Nigeria's high cost of natural gas, cooking gas, and kerosene has led to a situation where poor residents in forest communities are forced to resort to forests for their energy needs. This has resulted in the degradation of the ecosystem and a change in the forest cover” (Government official KII 002, June 2022). (

Appendix B Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–5.4) gives other details of some of the KII and FGD insights on policy as a driver for the forest change.

Poor governance and policies were also perceived to influence corruption by some of the forest officials in the study area. For instance, when it comes to obtaining permits or documents, bribes were reportedly necessary. This includes using bribes to secure access to forest reserves for farming, timber, and other uses, as well as to obtain agricultural concessions in these reserves. In some cases, domestic companies may even pay bribes to subcontract and overharvest logging concessions, and members of local communities and government officials are involved affecting the governance for the protection of the forest particularly noted in the Risha forest community (

Appendix B Table 4). A participant in one of the forest communities, the Risha revealed that:

“The government forest officers assigned to monitor, manage, and enforce the forest laws against encroachments in this forest reserve encourage the community and even foreigners by collecting small bribes from them and then allowing them to enter the forest and degrade it for timber extraction, agricultural, and other uses, which leads to a high rate of cutting forest trees and a change in the forest reserves” (Risha local people KII 004, June 2022) (

Appendix B Table 2).

Furthermore, the stakeholders for both the KII and FGD expert and government official groups perceived similarly driver emphasised accelerated deforestation to change around this gazetted forest driven by rapid population growth, urbanisation, and economic pressures such as agricultural expansion, lumbering and fuelwood/fuel across around the forest reserve. Additional underlying (indirect) factors contributing to changes in the forest reserve in the area, as identified in the KII, include migration and insecurity (terrorism threats). However, they do not seem to have as much impact as other drivers on the gazetted forest change according to the stakeholders’ perceptions.

3.9. Correlation of the Key Insights for the Household Survey KIIs and FGD for the Study

In Doma Forest, a significant number of local community members and leaders identified agricultural expansion, lumbering, fuelwood collection/charcoal production, and grazing as the primary direct drivers of forest change. Similarly, in Risha, local households, community members, and leaders perceived these same direct drivers as being closely linked to livelihood needs (

Appendix B Table 1–4). In contrast, in Odu, while similar direct drivers were identified, lumbering was perceived as the first most influential driver, followed by agriculture, fuelwood/charcoal collection, and grazing.

Across all three forests, a substantial number of participants and stakeholders recognized human population growth, poor forest governance, and poverty as the key underlying drivers of forest degradation. These factors emerged as dominant concerns among local community members including the government and experts KIIs, and FGDs.

Notably, while most respondents from Doma, Risha, and Odu were farmers, they primarily linked forest change to economic necessity. On the other hand, stakeholders with higher education, including government officials and experts, shared a similar perception of the drivers but also emphasised policy failures and weak enforcement as critical factors influencing forest degradation.

In summary, the analysis reveals that while all three forest reserves in Nasarawa State face similar drivers of forest change, the qualitative data shows that their perceived intensity, trajectories and scale vary. Risha and Doma were perceived to exhibit the highest levels of agricultural expansion and forest degradation in the reserve, as evidenced by all data sources, while Odu's forest community perceived cultural controls of the traditional land use pattern of shifting cultivation. In Risha and Doma reserves, individuals on the agricultural frontier actively cleared land for permanent agriculture, as perceived by the community. In Odu reserve, the community revealed that land was initially cleared for valuable timber, with agriculture subsequently encroaching, later, while various drivers and processes (e.g., population growth, poverty, and grazing) gradually contributed to the change in the degraded forest, leading to rapid agricultural expansion in some decades. However, Odu is currently experiencing a gradual to rapid recovery as observed from the fieldwork by the researcher, also reported by the stakeholder, attributed to a shift in traditional agriculture.

Stakeholders from expert and government officials KII and FGD perceived similar drivers and human activities, noting agricultural expansion driven by population growth and timber extraction as gradual or fast causes of deforestation and forest cover change around the reserves. Underlying drivers such as population growth, poverty, poor governance, and corruption are perceived to be common across all reserves. Population growth has increased pressure on forest resources, while poverty has driven communities to exploit forests for livelihoods. Poor governance and weak policy implementation have exacerbated deforestation in all reserves. However, these underlying drivers are perceived more widely in Risha and Doma, where forest degradation is more extensive compared to Odu from the revealed perception of these areas (

Table 1–4 and section 3.5.1–5.4). Addressing these drivers requires targeted interventions for conservation and management, including improving governance, providing alternative livelihoods, and promoting sustainable land use practices.

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Interplay Between Social and Biophysical Drivers of Forest Change

The intricate relationship between social and biophysical processes that drive land-use changes, particularly those impacting forest cover, is influenced by a combination of direct and underlying factors, often stemming from human activities [

8,