Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Storage

2.2. Nucleic Acids Extraction

2.3. Quantitative PCR and RT-qPCR

2.4. Statistical Analyses

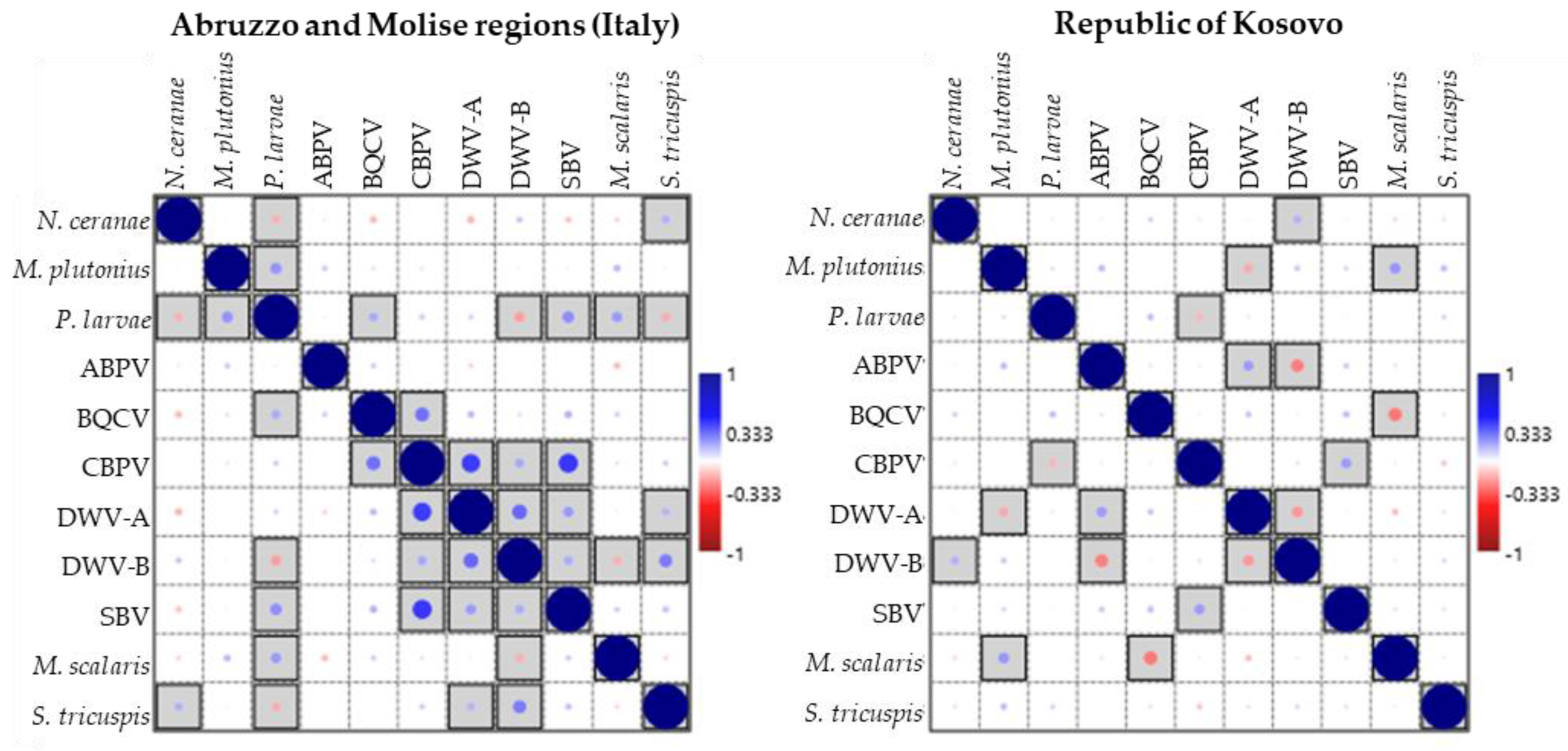

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABPV | Acute bee paralysis virus |

| AFB | American foulbrood |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variants |

| BQCV | Black queen cell virus |

| CBPV | Chronic bee paralysis virus |

| DWV-A | Deformed wings virus A |

| DWV-B | Deformed wings virus B |

| EFB | European foulbrood |

| IPA | Infectious or parasitic agent |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

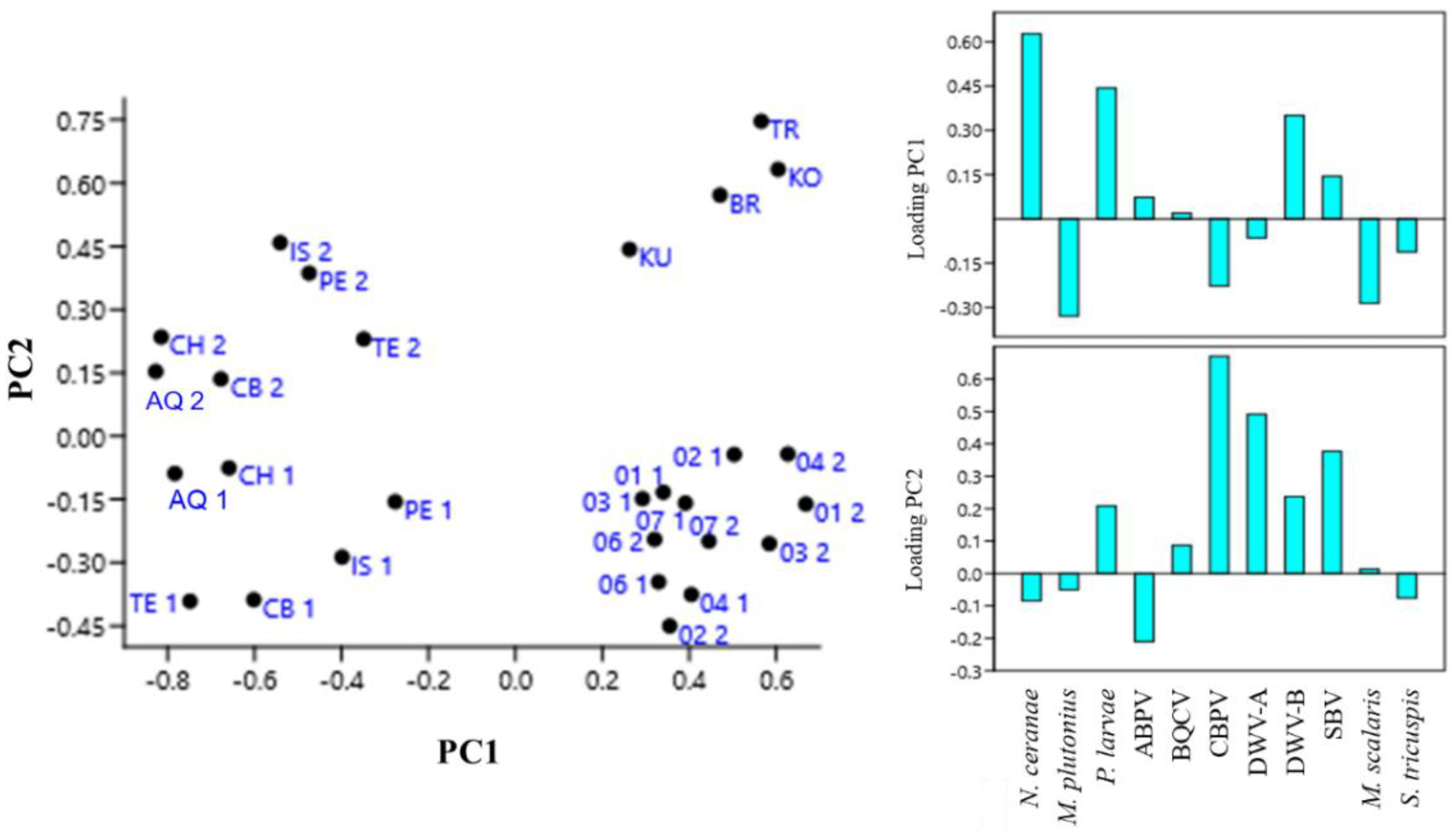

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PC1 | Principal component 1 |

| PC2 | Principal component 2 |

| qPCR | Quantitative PCR |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcriptase qPCR |

| SBV | Sacbrood virus |

| WGS | Whole genome sequencing |

References

- Babin, A.; Schurr, F.; Delannoy, S.; Fach, P.; Huyen Ton Nu Nguyet, M.; Bougeard, S.; de Miranda, J. R.; Rundlöf, M.; Wintermantel, D.; Albrecht, M.; Attridge, E.; Bottero, I.; Cini, E.; Costa, C.; De la Rúa, P.; Di Prisco, G.; Dominik, C.; Dzul, D.; Hodge, S.; Klein, A.-M.; Knapp, J.; Knauer, A. C.; Mänd, M.; Martínez-López, V.; Medrzycki, P.; Pereira-Peixoto, M. H.; Potts, S. G.; Raimets, R.; Schweiger, O.; Senapathi, D.; Serrano, J.; Stout, J. C.; Tamburini, G.; Brown, M. J. F.; Laurent, M.; Rivière, M.-P.; Chauzat, M.-P.; Dubois, E. Distribution of Infectious and Parasitic Agents among Three Sentinel Bee Species across European Agricultural Landscapes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertola, M.; Mutinelli, F. The Dilemma of Honey Bee Pest Management in European Union: Eradication or Coexistence? Insect Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, J. R.; Cordoni, G.; Budge, G. The Acute Bee Paralysis Virus-Kashmir Bee Virus-Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus Complex. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103 Suppl 1, S30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, C. I.; Luong, L. T.; Pernal, S. F. Effects of Nosema Ceranae and Lotmaria Passim Infections on Honey Bee Foraging Behaviour and Physiology. Int. J. Parasitol. 2025, 55, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevill, J. L.; de Souza, F. S.; Sharples, C.; Oliver, R.; Schroeder, D. C.; Martin, S. J. DWV-A Lethal to Honey Bees (Apis mellifera): A Colony Level Survey of DWV Variants (A, B, and C) in England, Wales, and 32 States across the US. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, T.; Evans, J. D.; Rose, R.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Heerman, M.; Rodríguez-García, C.; Banmekea, O.; Brister, J. R.; Hatcher, E. L.; Cao, L.; Hamilton, M.; Chen, Y. The Phylogeny and Pathogenesis of Sacbrood Virus (SBV) Infection in European Honey Bees, Apis Mellifera. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naggar, Y.; Paxton, R.J. Mode of Transmission Determines the Virulence of Black Queen Cell Virus in Adult Honey Bees, Posing a Future Threat to Bees and Apiculture. Viruses 2020, 12, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, G.E.; Simcock, N.K.; Holder, P.J.; Shirley, M.D.F.; Brown, M.A.; Van Weymers, P.S.M.; Evans, D.J.; Rushton, S.P. Chronic Bee Paralysis as a Serious Emerging Threat to Honey Bees. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittes, J.; Schäfer, M.O.; Aupperle-Lellbach, H.; Mülling, C.K.W.; Emmerich, I.U. Overt Infection with Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus (CBPV) in Two Honey Bee Colonies. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, F.; Iannitto, M.; Hulaj, B.; Manocchio, P.; Gentile, F.; Del Matto, I.; Paoletti, M.; Marino, L.; Ricchiuti, L. Megaselia scalaris and Senotainia tricuspis Infesting Apis mellifera: Detection by Quantitative PCR, Genotyping, and Involvement in the Transmission of Microbial Pathogens. Insects 2024, 15, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. 52010DC0714/COM/2010/0714 final/ Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on Honeybee Health. 2010 https://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:52010DC0714:EN:HTML. Accessed on. 10 September.

- 14 October 2025, World Organization for Animal Health. Chapter 3.2.1. Acarapisosis of honey bees; Chapter 3.2.2. American foulbrood of honey bees; Chapter 3.2.3. European foulbrood of honey bees; Chapter 3.2.4. Infestation of honey bees with Aethina tumida; Chapter 3.2.5. Infestation of honey bees with Tropilaelaps spp.; Chapter 3.2.6. Varroosis of honey bees. In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals, thirteenth ed. 2024, https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/A_summry.htm. Accessed on.

- Formato, G. Guidelines on sustainable management of honeybee diseases in Europe. BPRACTICES (ERA-NET SusAn) Project – towards a sustainable European beekeeping. 2020 https://www.izslt.it/bpractices/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2020/03/bpractices-guidelines.pdf. Accessed on. 14 October.

- Ministero della Salute. Anagrafe Apistica, BDN, 2023 https://www.vetinfo.it/j6_bdn/common/public/?applCodice=API. Accessed on. 8 September.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development – Republic of Kosovo. Bujqësia e Kosovës në Numra. https://www.mbpzhr-ks.net/repository/docs/Bujqesia_e_Kosoves_ne_Numra_2023.pdf. 2023. https://www.instat.gov.al/en/themes/agriculture-and-fishery/livestock/#tab2. Accessed on. 10 June.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development – Republic of Kosovo. Administrative Instruction N0. 15/2008 for prevention, combating and eradication of contagious bee diseases. 2008, https://www.mbpzhr-ks.net/repository/docs. Accessed on. 10 June.

- Babin, A.; Schurr, F.; Rivière, M.-P.; Chauzat, M.-P.; Dubois, E. Specific Detection and Quantification of Three Microsporidia Infecting Bees, Nosema Apis, Nosema Ceranae, and Nosema Bombi, Using Probe-Based Real-Time PCR. Eur. J. Protistol. 2022, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, J.; Reinecke, A.; Sibum, N.; Fünfhaus, A.; Aumeier, P.; Otten, C.; Genersch, E. A Comparison of Different Matrices for the Laboratory Diagnosis of the Epizootic American Foulbrood of Honey Bees. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10(2), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biová, J.; Charrière, J.-D.; Dostálková, S.; Škrabišová, M.; Petřivalský, M.; Bzdil, J.; Danihlík, J. Melissococcus plutonius Can Be Effectively and Economically Detected Using Hive Debris and Conventional PCR. Insects 2021, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biganski, S.; Lester, T.; Obshta, O.; Jose, M. S.; Thebeau, J. M.; Masood, F.; Silva, M. C. B.; Camilli, M. P.; Raza, M. F.; Zabrodski, M. W.; Kozii, I.; Koziy, R.; Moshynskyy, I.; Simko, E.; Wood, S. C. Comparison of Individual and Pooled Sampling Methods for Estimation of Vairimorpha (Nosema) Spp. Levels in Experimentally Infected Honey Bee Colonies. Levels in Experimentally Infected Honey Bee Colonies. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2023, 35(6), 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudi, S.; Rossi, F.; Ricchiuti, L.; Manocchio, P.; Del Matto, I.; Jürison, M.; Pent, K.; Mänd, M.; Karise, R.; Viinalass, H.; Raimets, R. Could Hive Debris Samples and qPCR Ease the Investigation of Factors Influencing Paenibacillus Larvae Spore Loads? J. Apic. Res. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Del Matto, I.; Ricchiuti, L.; Marino, L. Selection and Multiplexing of Reverse Transcription–Quantitative PCR Tests Targeting Relevant Honeybee Viral Pathogens. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roetschi, A.; Berthoud, H.; Kuhn, R.; Imdorf, A. Infection Rate Based on Quantitative Real-Time PCR of Melissococcus Plutonius, the Causal Agent of European Foulbrood, in Honeybee Colonies before and after Apiary Sanitation. Apidologie (Celle) 2008, 39, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Amadoro, C.; Ruberto, A.; Ricchiuti, L. Evaluation of Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Paenibacillus larvae Targeted Assays and Definition of Optimal Conditions for Its Detection/Quantification in Honey and Hive Debris. Insects 2018, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, D.M.T.; Madden, R.H.; Sattler, A. An improved method for the detection and presumptive identification of Paenibacillus larvae subsp. larvae spores in honey. J. Apic. Res. 2001, 40, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alvise, P.; Seeburger, V.; Gihring, K.; Kieboom, M.; Hasselmann, M. Seasonal Dynamics and Co-Occurrence Patterns of Honey Bee Pathogens Revealed by High-Throughput RT-qPCR Analysis. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 10241–10252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Rural Development - Republic of Kosovo. Administrative instruction n. 13/2024 for evaluation and compensation of eliminated animal due to infectious diseases. 2024, https://www.mbpzhr-ks.net/repository/docs/UDHEZIM_ADMINISTRATIV_MBPZHR_NR.132024.pdf. Accessed on. 25 June.

- Hulaj, B.; Granato, A.; Bordin, F.; Goga, I.; Merovci, X.; Caldon, M.; Cana, A.; Zulian, L.; Colamonico, R.; Mutinelli, F. Emergent and Known Honey Bee Pathogens through Passive Surveillance in the Republic of Kosovo. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuliçi, M.; Kokthi, E.; Hasani, A.; Zoto, O.; Marcelino, J. A. P.; Giordano, R. Threats and drivers of change in populations of managed honey bees (Apis mellifera) in the Balkan countries of Albania and Kosovo 2023. Bull. Insectol. 2023, 76, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Cilia, G.; Garrido, C.; Bonetto, M.; Tesoriero, D.; Nanetti, A. Effect of Api-Bioxal® and ApiHerb® Treatments against Nosema ceranae Infection in Apis mellifera Investigated by Two qPCR Methods. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, R.; Mancianti, F.; Canovai, R.; Cosci, F.; Rocchigiani, G.; Benelli, G.; Canale, A. Prevalence of the Microsporidian Nosema Ceranae in Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) Apiaries in Central Italy. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, F.; Zulian, L.; Granato, A.; Caldon, M.; Colamonico, R.; Toson, M.; Trevisan, L.; Biasion, L.; Mutinelli, F. Presence of Known and Emerging Honey Bee Pathogens in Apiaries of Veneto Region (Northeast of Italy) during Spring 2020 and 2021. Appl. Sci. (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudele, S.; Ricchiuti, L.; Ruberto, A.; Rossi, F. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) vs Culture-Dependent Detection to Assess Honey Contamination by Paenibacillus Larvae. J. Apic. Res. 2020, 59, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A.; Alavi-Shoushtari, N.; Tran, L.; Labuschagne, R.; Cunningham, M.; Tsvetkov, N.; Common, J.; Higo, H.; Pernal, S. F.; Giovenazzo, P.; Hoover, S. E.; Guzman-Novoa, E.; Currie, R. W.; Veiga, P. W.; French, S. K.; Conflitti, I. M.; Pepinelli, M.; Borges, D.; Walsh, E. M.; Bishop, C. A.; Zayed, A.; Duffe, J.; Foster, L. J.; Guarna, M. M. Climatic Predictors of Prominent Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera) Disease Agents: Varroa Destructor, Melissococcus Plutonius, and Vairimorpha Spp. PLOS Clim. PLOS Clim. 2024, 3(8), e0000485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shaara, H. F.; Darwish, A. A. E. Expected Prevalence of the Facultative Parasitoid Megaselia Scalaris of Honey Bees in Africa and the Mediterranean Region under Climate Change Conditions. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2021, 41, 3137–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shaara, H.; Al-Khalaf, A. A. Potential Alterations in the Spread of the Honey Bee Pest, Senotainia Tricuspis, across the Mediterranean Region and Africa in Response to Shifting Climatic Conditions. J. Entomol. Res. Soc.

- von Büren, R. S.; Oehen, B.; Kuhn, N. J.; Erler, S. High-Resolution Maps of Swiss Apiaries and Their Applicability to Study Spatial Distribution of Bacterial Honey Bee Brood Diseases. Peer J. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, P. D.; Dhakal, U.; Chang, J. H.; Milbrath, M. O. Everything, Everywhere, All at Once - Surveillance and Molecular Epidemiology Reveal Melissococcus Plutonius Is Endemic among Michigan, US Beekeeping Operations. PLoS One 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Pang, C.; Zhuo, F.; Hu, B.; Huang, X.; Huang, J.; Lu, Y. High Prevalence and Strain Diversity of Melissococcus Plutonius in Apis Cerana in Guangxi, China. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2025, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, É. W.; Viana, T. A.; Lima, M. A. P.; Martins, G. F.; Lourenço, A. P. Detection and Identification of Melissococcus Plutonius in Stingless Bees (Apidae: Meliponini) from Brazil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2025, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossar, D.; Haynes, E.; Budge, G. E.; Parejo, M.; Gauthier, L.; Charrière, J.-D.; Chapuisat, M.; Dietemann, V. Population Genetic Diversity and Dynamics of the Honey Bee Brood Pathogen Melissococcus Plutonius in a Region with High Prevalence. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2023, 196(107867), 107867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddie, M. A. Y.; Lanz, S.; Dahle, B.; Yañez, O.; Neumann, P. Virus Infections in Honeybee Colonies Naturally Surviving Ectoparasitic Mite Vectors. PLoS One 2023, 18(12), e0289883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doublet, V.; Oddie, M. A. Y.; Mondet, F.; Forsgren, E.; Dahle, B.; Furuseth-Hansen, E.; Williams, G. R.; De Smet, L.; Natsopoulou, M. E.; Murray, T. E.; Semberg, E.; Yañez, O.; de Graaf, D. C.; Le Conte, Y.; Neumann, P.; Rimstad, E.; Paxton, R. J.; de Miranda, J. R. Shift in Virus Composition in Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) Following Worldwide Invasion by the Parasitic Mite and Virus Vector Varroa Destructor. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, R. J.; Schäfer, M. O.; Nazzi, F.; Zanni, V.; Annoscia, D.; Marroni, F.; Bigot, D.; Laws-Quinn, E. R.; Panziera, D.; Jenkins, C.; Shafiey, H. Epidemiology of a Major Honey Bee Pathogen, Deformed Wing Virus: Potential Worldwide Replacement of Genotype A by Genotype B. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2022, 18, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircoulomb, F.; Dubois, E.; Schurr, F.; Lucas, P.; Meixner, M.; Bertolotti, A.; Blanchard, Y.; Thiéry, R. Genotype B of Deformed Wing Virus and Related Recombinant Viruses Become Dominant in European Honey Bee Colonies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, Z.S.; Chen, Y.; Evans, J.D. Case Report: Emerging Losses of Managed Honey Bee Colonies. Biology 2024, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A. R.; Low, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Pinto, M. A.; De Miranda, J. R. Origins, Diversity, and Adaptive Evolution of DWV in the Honey Bees of the Azores: The Impact of the Invasive Mite Varroa Destructor. Virus Evol. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavatta, L.; Bortolotti, L.; Catelan, D.; Granato, A.; Guerra, I.; Medrzycki, P.; Mutinelli, F.; Nanetti, A.; Porrini, C.; Sgolastra, F.; Tafi, E.; Cilia, G. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Distribution of Chronic Bee Paralysis Virus (CBPV) in Honey Bee Colonies. Virology 2024, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinatto, G.; Mondet, F.; Marzachi, C.; Alaux, C.; Bassi, E.; Dievart, V.; Gotti, M.; Guido, G.; Jourdan, P.; Kairo, G.; Maisonnasse, A.; Michel, L.; Peruzzi, M.; Porporato, M.; Tagliabue, M.; Kretzschmar, A.; Bosco, D.; Manino, A. Seasonal Variations of the Five Main Honey Bee Viruses in a Three-Year Longitudinal Survey. Apidologie (Celle) 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilia, G.; Tafi, E.; Zavatta, L.; Dettori, A.; Bortolotti, L.; Nanetti, A. Seasonal Trends of the ABPV, KBV, and IAPV Complex in Italian Managed Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera L.) Colonies. Arch. Virol.

|

Province/ district |

Year | N. samples | N. apis | N. ceranae | M. plutonius | P. larvae | ABPV | BQCV | CBPV | DWV-A | DWV-B | SBV | M. scalaris | S. tricuspis | ||

| Abruzzo and Molise regions (Italy) | ||||||||||||||||

| N. positive samples | ||||||||||||||||

| Campobasso | 2022 | 26 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 21 | 11 | 15 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 4 | ||

| 2023 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Chieti | 2022 | 26 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 16 | 22 | 17 | 12 | 8 | 11 | ||

| 2023 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | |||

| Isernia | 2022 | 18 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 2 | ||

| 2023 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 | |||

| L’Aquila | 2022 | 25 | 0 | 4 | 18 | 15 | 2 | 23 | 16 | 15 | 4 | 17 | 14 | 4 | ||

| 2023 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Pescara | 2022 | 17 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 4 | ||

| 2023 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Teramo | 2022 | 19 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 19 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | ||

| 2023 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Republic of Kosovo | ||||||||||||||||

| N. positive samples | ||||||||||||||||

| Gjakova | 2022 | 45 | 0 | 41 | 2 | 32 | 07 | 36 | 17 | 27 | 38 | 28 | 6 | 2 | ||

| 2023 | 19 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 16 | 30 | 18 | 3 | 11 | 16 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gjilane | 2022 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 2023 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Mitrovica | 2022 | 13 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 2023 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Peja | 2022 | 29 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 18 | 4 | 23 | 13 | 16 | 26 | 16 | 5 | 0 | ||

| 2023 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Pristina | 2022 | 14 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 13 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 2023 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Prizren | 2022 | 26 | 0 | 21 | 2 | 21 | 5 | 24 | 6 | 12 | 21 | 11 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2023 | 11 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 0 | 1 | |||

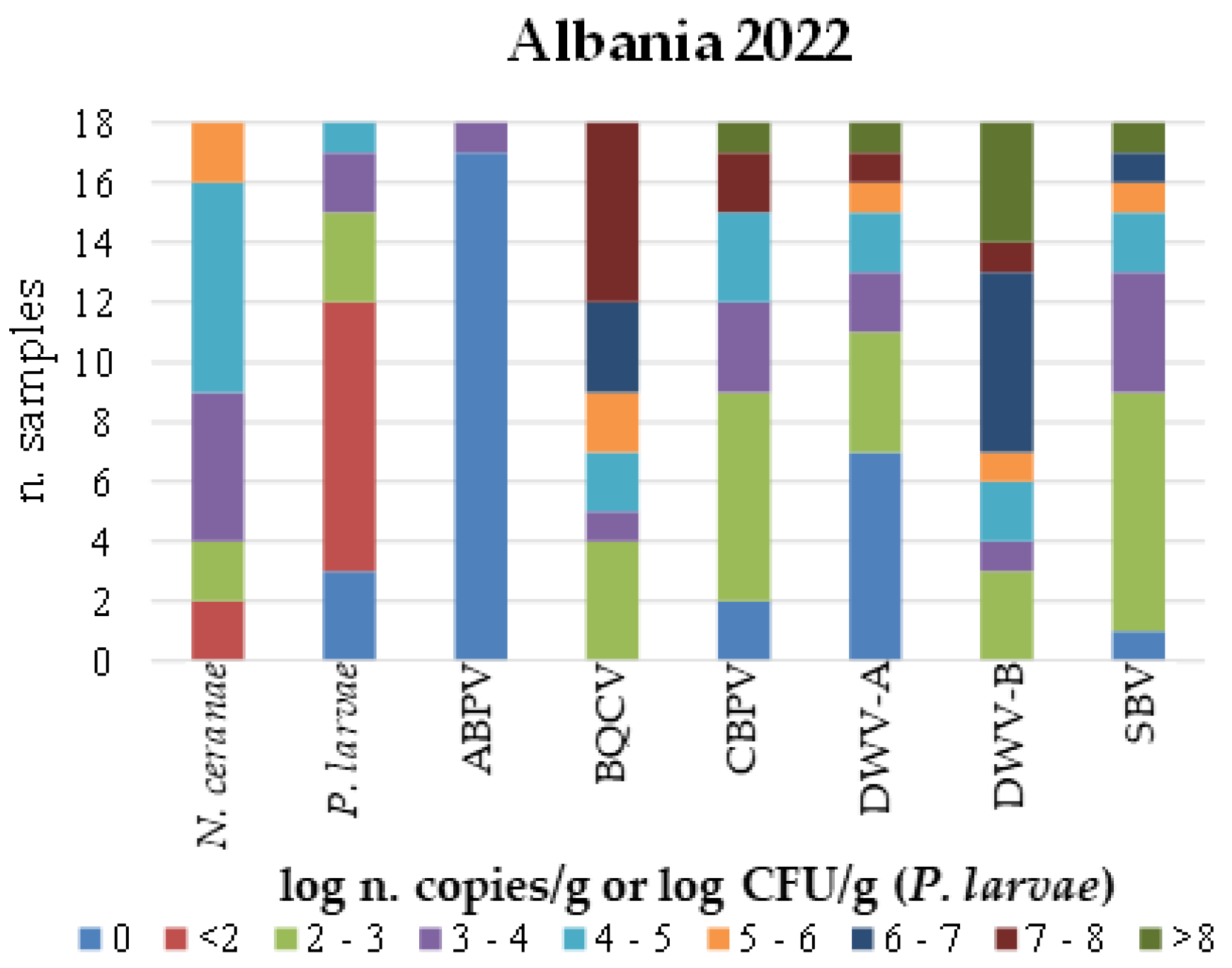

| Albania | ||||||||||||||||

| N. positive samples | ||||||||||||||||

| Kukës | 2022 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Berat | 2022 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Tiranë | 2022 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Korçë | 2022 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).