Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

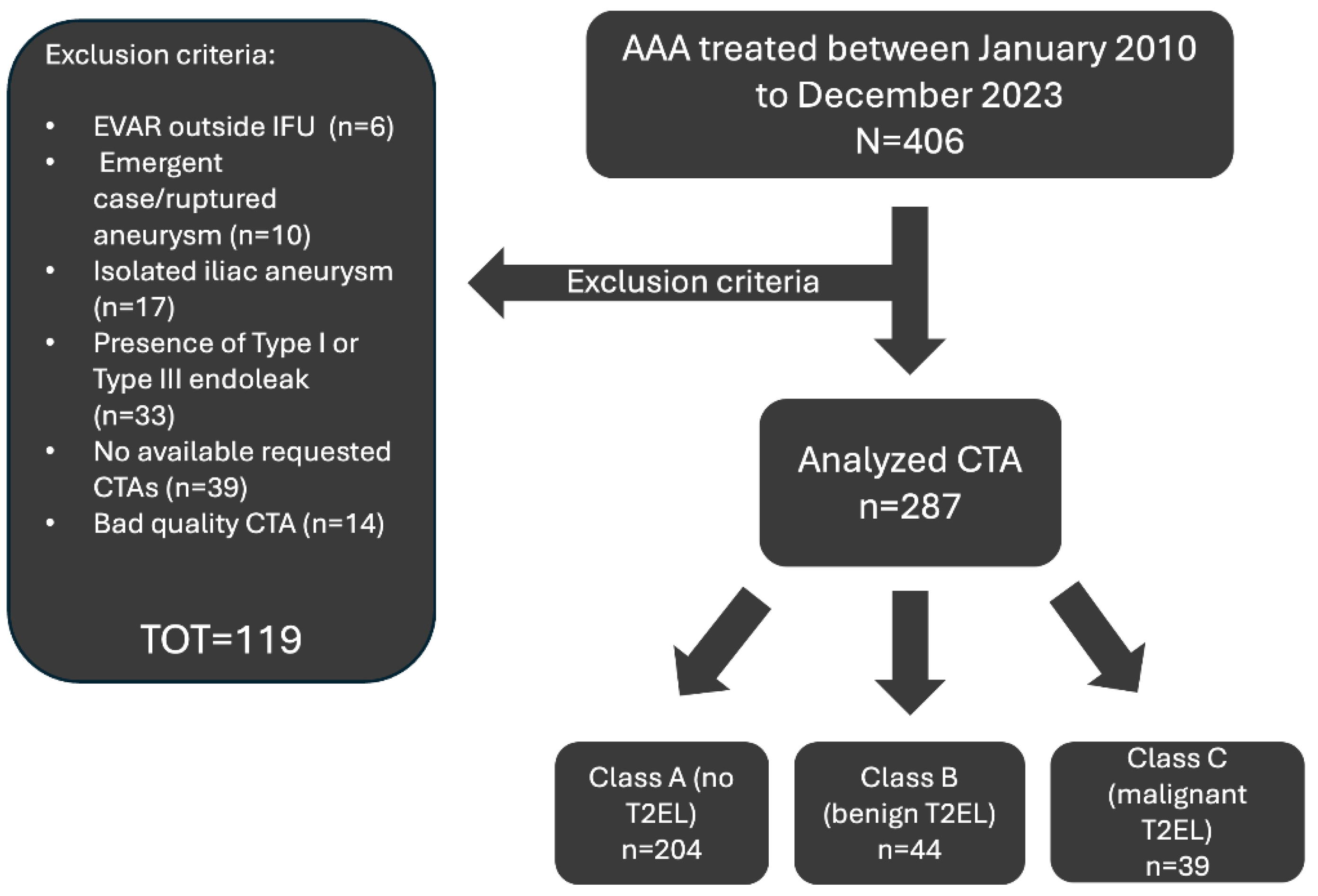

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Age >18 years.

- Treatment with standard EVAR performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions for use for AAA.

- Non-ruptured AAA.

- Minimum follow-up of 1 year.

- Availability of a 1–3-month postoperative computed tomography angiography (CTA).

- Availability of a preoperative CTA.

- For patients with T2EL at least one additional CTA at least 6 months after the detection.

- Adequate CTA image quality (slice thickness ≤2.5 mm), including coverage from the celiac trunk to the external iliac vessels.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. CT Angiography Protocol

- Helical scan from lung apices to small truncus.

- kV = 100; pitch = 1.50; acquisition (mm) = 64 x 0.60.

- Bolus tracking 2 cm below the tracheal bifurcation, with ROI in the ascending arch.

- Bolus tracking scan delay plus 7 seconds.

- No ECG synchronization and no patient apnea during the scan.

- Contrast medium injection: 15 ml NaCl at 5.0 ml/s followed by 100 ml Accupaque 350 at 5.0 ml/s and followed by 50 ml NaCl at 5.0 ml/s.

2.5. Endoleak Evaluation

2.6. Patient Stratification

- A training set consisting of 185 cases, 150 Class A, 20 class B and 15 class C.

- A validation set consisting of 52 cases, 44 class A, 4 class B and 4 class C.

- A test set consisting of 30 cases, 10 class A, 10 class B and 10 class C.

2.7. Data Augmentation

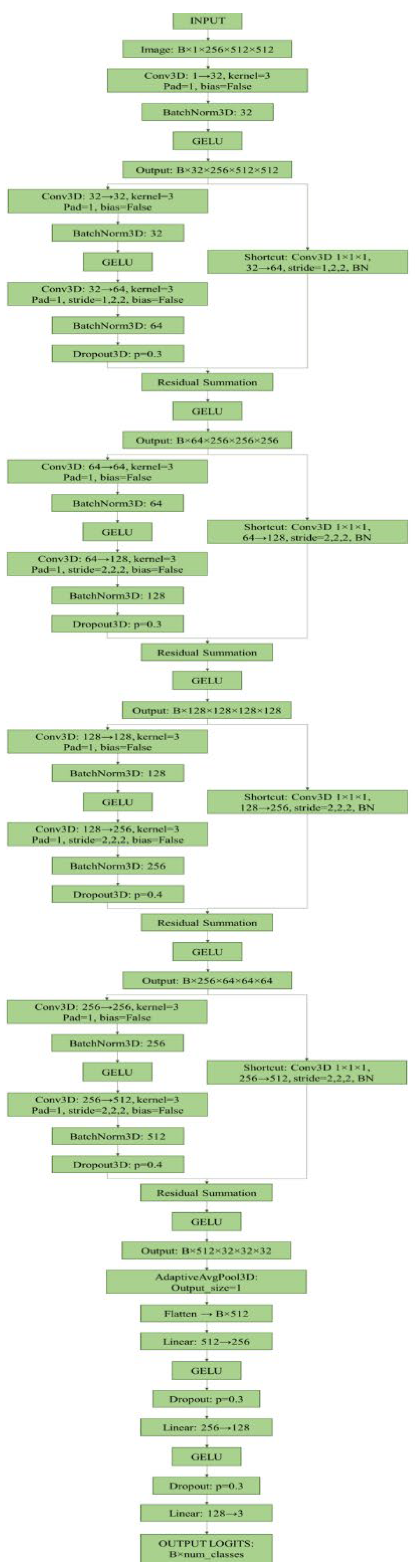

2.8. Model Architecture

- Initial Block (1→32 channels): a single 3D convolutional layer (3x3x3 kernel, padding=1) followed by batch normalisation and GELU activation. The spatial output dimensions remain 256×512×512.

- Residual Block 1 (32→64 channels): introduces the first dimensional reduction. It consists of two convolutional layers (32→32 and 32→64) and a 1x1x1 shortcut connection (32→64). Downsampling is achieved via an anisotropic stride (1, 2, 2) in both the main convolution and the shortcut. Includes batch normalisation, GELU and 3D dropout (p=0.3). Output dimensions: 256×256×256.

- Residual Block 2 (64→128 channels): follows a similar residual structure (conv 64→64 and 64→128; shortcut 64→128) using a stride (2, 2, 2) for downsampling. Includes batch normalisation, GELU, and 3D dropout (p=0.3). Output dimensions: 128×128×128.

- Residual Block 3 (128→256 channels): expands channels to 256 (conv 128→128 and 128→256; shortcut 128→256) with stride (2, 2, 2). Dropout is increased to p=0.4. Output dimensions: 64×64×64.

- Residual Block 4 (256→512 channels): final block (conv 256→256 and 256→512; shortcut 256→512) with stride (2, 2, 2) and dropout (p=0.4). Output dimensions: 32×32×32.

- Pooling: the final feature maps (512 channels) are processed by an Adaptive Average Pooling 3D layer that reduces the output to a single 512-dimensional vector.

- The extracted features are then processed through a fully connected classifier (MLP) consisting of three dense layers (512→256→128→3) with GELU activation functions and dropout regularisation (p=0.4 for the first layer, p=0.3 for the second). The output layer uses softmax activation for multi-class probabilistic prediction.

2.9. Hardware and Software Configuration

2.10. Statistical Analysis and Model Evaluation

- Overall accuracy: the proportion of correct predictions out of the total.

- Precision, Recall and F1-Score: these metrics were calculated both for each individual class and as a weighted average (macro-averaged) to provide a balanced assessment of performance across classes, especially in the presence of imbalance in the training dataset.

- Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC): the AUC was calculated for each class (one-vs-rest) to measure the model’s discriminatory power.

- Confusion Matrix: a confusion matrix was generated to analyse classification errors (e.g. false positives and false negatives) between different classes in detail.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline

3.2. Overall Model Performance

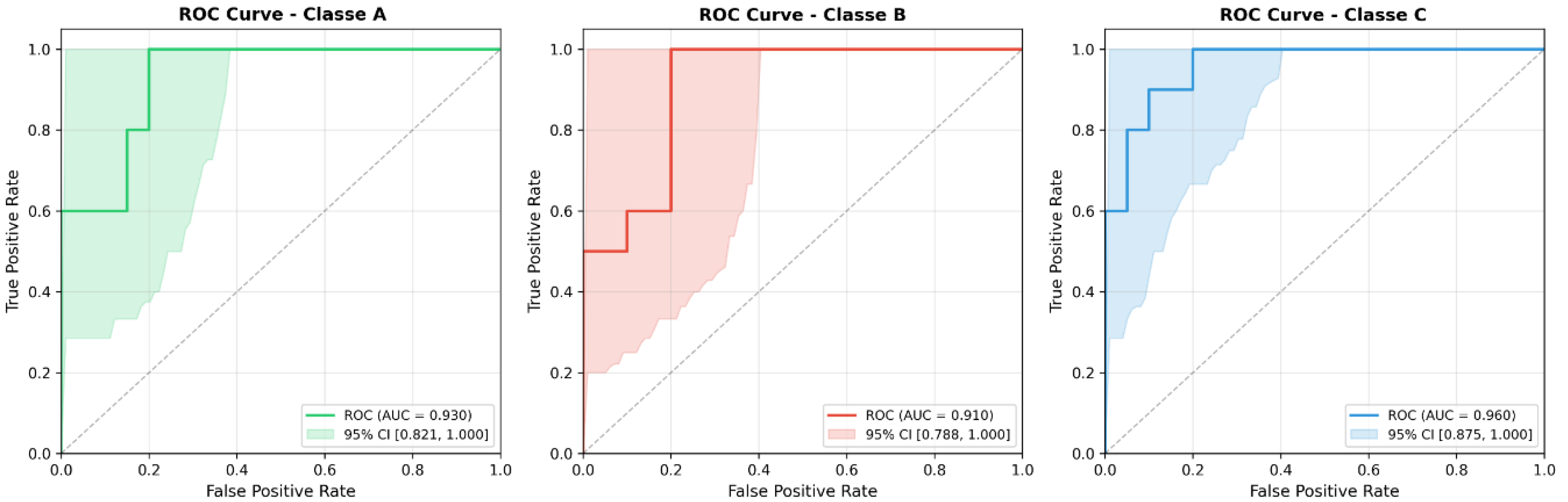

3.3. Performance per class

- Class A (No Endoleak): The Precision was 0.692 and the F1 Score was 0.783. Only one patient in this class was a False Negative (FN), while there were 4 False Positives (FP). The ROC AUC was 0.930.

- Class B (Benign T2EL): The classification of T2ELs showed an Accuracy of 0.778, a Recall of 0.700 and an F1 Score of 0.737. The model correctly identified 7 out of 10 patients. Class B was the only one with 3 false negatives and 2 false positives. The ROC AUC was 0.910.

- Class C (Malignant T2EL): The prediction of malignant T2ELs, often considered ‘malignant’ in the follow-up context, achieved the highest accuracy among all classes at 0.875. The recall was 0.700 and the F1 score 0.778. Seven out of ten patients were correctly identified, with only one false positive and three false negatives. This class also had the best ROC AUC at 0.960.

3.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis

- 9 were correctly identified (TP), 90%.

- 1 was misclassified as Class B, 10%.

- 7 were correctly identified (TP), 70%.

- 2 were misclassified as Class A, 20%.

- 1 was misclassified as Class C, 10%.

- 7 were correctly identified (TP), 70%.

- 2 were classified as Class A, 20%.

- 1 was classified as Class B, 10%.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 95CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

| AAA | Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CTA | Computed Tomography Angiography |

| 3D CNN | 3D Convolutional Neural Network |

| ESVS | European Society for Vascular Surgery |

| EVAR | EndoVascular Aneurysm Repair |

| EOC | Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale |

| GELU | Gaussian Error Linear Unit |

| IIMSI | Imaging Institute of Southern Switzerland |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| T2EL | Type II Endoleak |

References

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D’Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karkos, C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice -- European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.T.; Sweeting, M.J.; Ulug, P.; Blankensteijn, J.D.; Lederle, F.A.; Becquemin, J.-P.; Greenhalgh, R.M. EVAR-1, DREAM, OVER and ACE Trialists Meta-Analysis of Individual-Patient Data from EVAR-1, DREAM, OVER and ACE Trials Comparing Outcomes of Endovascular or Open Repair for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm over 5 Years. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, G.H.; Yu, W.; May, J.; Chaufour, X.; Stephen, M.S. Endoleak as a Complication of Endoluminal Grafting of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Classification, Incidence, Diagnosis, and Management. J. Endovasc. Surg. Off. J. Int. Soc. Endovasc. Surg. 1997, 4, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennai, S.; Andreoli, F.; Leone, N.; Bartolotti, L.A.M.; Maleti, G.; Silingardi, R. Incidence, Long Term Clinical Outcomes, and Risk Factor Analysis of Type III Endoleaks Following Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 66, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaikof, E.L.; Dalman, R.L.; Eskandari, M.K.; Jackson, B.M.; Lee, W.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Mastracci, T.M.; Mell, M.; Murad, M.H.; Nguyen, L.L.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Practice Guidelines on the Care of Patients with an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 2–77.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.H.; Lindström, D.; Wanhainen, A.; Tegler, G.; Hassan, B.; Mani, K. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prophylactic Aortic Side Branch Embolization to Prevent Type II Endoleaks. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 72, 1783–1792.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.H.; Lindström, D.; Wanhainen, A.; Tegler, G.; Asciutto, G.; Mani, K. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Pre-Emptive Aortic Side Branch Embolization to Prevent Type II Endoleaks after Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 77, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihashi, S.; Takahara, M.; Fujimura, N.; Banno, H.; Onitsuka, S.; Shingaki, M.; Yamaoka, T.; Sumi, M.; Iida, O.; Iwakoshi, S.; et al. Editor’s Choice - Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of Pre-Emptive Inferior Mesenteric Artery Embolisation during Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair on Aneurysm Sac Change. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 70, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Timmeren, J.E.; Cester, D.; Tanadini-Lang, S.; Alkadhi, H.; Baessler, B. Radiomics in Medical Imaging-”how-to” Guide and Critical Reflection. Insights Imaging 2020, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.; Beichel, R.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Finet, J.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pujol, S.; Bauer, C.; Jennings, D.; Fennessy, F.; Sonka, M.; et al. 3D Slicer as an Image Computing Platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalambous, S.; Klontzas, M.E.; Kontopodis, N.; Ioannou, C.V.; Perisinakis, K.; Maris, T.G.; Damilakis, J.; Karantanas, A.; Tsetis, D. Radiomics and Machine Learning to Predict Aggressive Type 2 Endoleaks after Endovascular Aneurysm Repair: A Proof of Concept. Acta Radiol. Stockh. Swed. 1987 2022, 63, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javor, D.; Wressnegger, A.; Unterhumer, S.; Kollndorfer, K.; Nolz, R.; Beitzke, D.; Loewe, C. Endoleak Detection Using Single-Acquisition Split-Bolus Dual-Energy Computer Tomography (DECT). Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 1622–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prouse, G.; Robaldo, A.; van den Berg, J.C.; Ettorre, L.; Mongelli, F.; Giovannacci, L. Impact of Multidisciplinary Team Meetings on Decision Making in Vascular Surgery: A Prospective Observational Study. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 66, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Cowled, P.; Boult, M.; Howell, S.; Fitridge, R. Type II Endoleak after Endovascular Aneurysm Repair: Natural History and Treatment Outcomes. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 44, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Batti, S.; Cochennec, F.; Roudot-Thoraval, F.; Becquemin, J.-P. Type II Endoleaks after Endovascular Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Are Not Always a Benign Condition. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Gimpel, K. Gaussian Error Linear Units (GELUs) 2023.

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift 2015.

- Lo, R.C.; Buck, D.B.; Herrmann, J.; Hamdan, A.D.; Wyers, M.; Patel, V.I.; Fillinger, M.; Schermerhorn, M.L. Risk Factors and Consequences of Persistent Type II Endoleaks. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 63, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmal, M.M.; Pabittei, D.R.; Prapassaro, T.; Suhartono, R.; Moll, F.L.; Van Herwaarden, J.A. A Systematic Review of the Current Status of Interventions for Type II Endoleak after EVAR for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 95, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultee, K.H.J.; Büttner, S.; Huurman, R.; Bastos Gonçalves, F.; Hoeks, S.E.; Bramer, W.M.; Schermerhorn, M.L.; Verhagen, H.J.M. Editor’s Choice – Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Outcome of Treatment for Type II Endoleak Following Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 56, 794–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulay, S.; Geraedts, A.C.M.; Koelemay, M.J.W.; Balm, R.; Mulay, S.; Balm, R.; Elshof, J.W.; Elsman, B.H.P.; Hamming, J.F.; Koelemay, M.J.W.; et al. Type 2 Endoleak With or Without Intervention and Survival After Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 61, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascoli, C.; Faggioli, G.; Gallitto, E.; Pini, R.; Fenelli, C.; Cercenelli, L.; Marcelli, E.; Gargiulo, M. Tailored Sac Embolization During EVAR for Preventing Persistent Type II Endoleak. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 76, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchiori, A.; von Ristow, A.; Guimaraes, M.; Schönholz, C.; Uflacker, R. Predictive Factors for the Development of Type II Endoleaks. J. Endovasc. Ther. Off. J. Int. Soc. Endovasc. Spec. 2011, 18, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, M.; Ishizaka, T.; Watanabe, M.; Hori, T.; Kohno, H.; Ishida, K.; Nakaya, M.; Matsumiya, G. Analysis of Anatomical Risk Factors for Persistent Type II Endoleaks Following Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair Using CT Angiography. Surg. Today 2016, 46, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, K.; Huang, L.; Yao, C. Prediction of Persistent Type II Endoleak after Endovascular Aortic Repair Using Machine Learning Based on Preoperative Clinical Data and Radiomic. Vasc. Investig. Ther. 2025, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.; Perry, M.; Morris, C.S.; Wshah, S.; Bertges, D.J. Machine Deep Learning Accurately Detects Endoleak after Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. JVS-Vasc. Sci. 2020, 1, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, S.; Madani, M.H.; Madani, A.; Chien, A.; Shen, J.; Mastrodicasa, D.; Fleischmann, D.; Chan, F.P.; Mofrad, M.R.K. Machine Learning for Endoleak Detection after Endovascular Aortic Repair. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, L.; De Angelis, S.P.; Raimondi, S.; Rizzo, S.; Fanciullo, C.; Rampinelli, C.; Mariani, M.; Lascialfari, A.; Cremonesi, M.; Orecchia, R.; et al. Reproducibility of Radiomic Features in CT Images of NSCLC Patients: An Integrative Analysis on the Impact of Acquisition and Reconstruction Parameters. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2022, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorsak, A.R.; Rava, R.A.; Shiraz Bhurwani, M.M.; Chandra, A.R.; Davies, J.M.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Ionita, C.N. Automatic Radiomic Feature Extraction Using Deep Learning for Angiographic Parametric Imaging of Intracranial Aneurysms. J. Neurointerventional Surg. 2020, 12, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Oliver, J.; Tenezaca-Sari, X.; Faner Capo, X.; Ribeiro, T.; Dux-Santoy, L.; Ferrer-Cornet, M.; Bragulat-Arevalo, M.; Catala-Santarrufina, A.; Morales-Galan, A.; Lopez-Gutierrez, P.; et al. Deep Learning for Segmentation and Endoleak Detection in Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography in Endovascular Aortic Repair Patients. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorenburg, S.P.M.; Hoksbergen, A.W.J.; Yeung, K.K.; Wolterink, J.M. Multitask Deep Learning for Automated Detection of Endoleak at Digital Subtraction Angiography during Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2025, 7, e240392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Result | 95CI |

| Accuracy | 0.766 | 0.633-0.900 |

| F1-Score | 0.765 | 0.594-0.904 |

| Precision | 0.781 | 0.631-0.926 |

| Recall | 0.766 | 0.611-0.915 |

| AUC ROC | 0.933 | 0.871-0.980 |

| Class Name |

Precision (95% CI) |

Recall (95% CI) |

F1-score (95% CI) |

AUC ROC (95% CI) |

| No T2EL | 0.692 (0.428-0.937) |

0.900 (0.699-1.000) |

0.7826 (0.545-0.947) |

0.930 (0.821-1.000) |

| Benign T2EL | 0.7778 (0.500-1.000) |

0.700 (0.400-1.000) |

0.7368 (0.470-0.933) |

0.910 (0.788-1.000) |

| Malignant T2EL | 0.8750 (0.600-1.000) |

0.700 (0.375-1.000) |

0.777 (0.500-0.960) |

0.960 (0.875-1.000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).