1. Introduction

Couple satisfaction has long been framed as a central outcome in relationship science, integrating affective, communicative, and sexual dimensions into a global evaluation of the partnership’s quality and sustainability (Romeo V. M.., 2024). Contemporary models increasingly conceptualize couple satisfaction as a multidimensional construct that encompasses emotional intimacy, conflict management, shared meaning, and sexual well-being, rather than as a unidimensional “happiness” index (Funk & Rogge, 2007). Within this framework, sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction are not ancillary but constitute a key subsystem of relational adjustment, often used as proximal indicators of couple functioning in both research and clinical practice (Falzia, E. and Romeo, V.M, 2025). The Special Issue Psychological and Social Influences on Satisfaction in Couple Relationships of EJIHPE explicitly calls for contributions that illuminate how psychological processes, interpersonal dynamics, and socio-cultural contexts shape satisfaction trajectories in intimate partnerships; sexual dynamics represent a privileged lens through which such mechanisms can be examined.

A robust body of work has documented consistent positive associations between sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction across diverse samples and designs, suggesting that these constructs are dynamically intertwined rather than independent (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014; Fallis et al., 2016; Leavitt et al., 2021). Longitudinal data further indicate that changes in relationship and sexual satisfaction tend to co-evolve over time, and that high initial levels of sexual satisfaction can buffer against subsequent declines in relational satisfaction in long-term partnerships (Fallis et al., 2016; Leavitt et al., 2021). In parallel, systematic reviews of sexual satisfaction underscore its multifactorial nature, highlighting cognitive (e.g., expectations, scripts), relational (e.g., communication, perceived responsiveness), and socio-cultural (e.g., gender norms, double standards) determinants that extend beyond mere frequency of intercourse or orgasm (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2014). Within this landscape, orgasm—including its likelihood, timing, and subjective meaning—often appears as a central metric of “successful” sexual encounters, yet the ways in which orgasm is embedded in broader relational scripts remain insufficiently theorized.

A growing literature has identified what has been termed an “orgasm imperative” in many Western sexual cultures, whereby “good sex” is implicitly or explicitly equated with the reliable achievement of orgasm, especially penile–vaginal orgasm (Salisbury & Fisher, 2014; Armstrong et al., 2012). Quantitative research shows that orgasm frequency is cross-sectionally associated with higher sexual and relationship satisfaction; however, recent findings suggest that this association may be curvilinear, with both very low and very high levels of orgasm frequency linked to lower relational well-being, possibly due to performance pressures, rigid expectations, or compensatory sexual activity (Leavitt et al., 2021). Qualitative studies of orgasm experiences reveal that concerns about confirming one’s own sexual adequacy and protecting the partner’s ego often override attention to shared pleasure, leading, for example, to faked orgasms or scripted responses that prioritize external markers of success over internal attunement (Salisbury & Fisher, 2014). In other words, orgasm operates not only as a physiological event but also as a symbolically loaded achievement, deeply embedded in gendered scripts and relational power dynamics (Armstrong et al., 2012).

These findings open a conceptual paradox that is highly relevant for couple satisfaction: an intensified focus on orgasm and on having “good sex” does not necessarily translate into greater relational well-being and may, under certain configurations, undermine it. When sexual encounters are structured around the mandate to “deliver” orgasm—for oneself or for the partner—attention can shift from mutual subjectivity and affective co-regulation to self-monitoring, performance, and control. This shift resonates with clinical observations of orgasm-centered sexuality in which the partner is engaged primarily as an instrument to secure tension discharge or self-validation, rather than as a subject with whom meaning, vulnerability, and desire are co-constructed. Yet, despite the clinical salience of this phenomenon, the empirical literature rarely frames it explicitly as a continuum between using the partner as a masturbatory object and engaging in relationally co-constructed sexuality.

Several lines of research converge on constructs that approximate this masturbatory use of the partner. Work on sexual narcissism has shown that a pattern of exploitative, entitled, and empathy-deficient sexual relating is prospectively associated with lower sexual and marital satisfaction over the early years of marriage, even when global narcissism is not (McNulty & Widman, 2013). Here, the partner’s body and responsiveness are implicitly recruited to regulate fragile self-esteem and confirm a sense of sexual prowess, narrowing the relational field to the self’s needs. Similarly, studies on alexithymia and negative affect have linked difficulties in emotional awareness and regulation to disengaged and sometimes compulsive sexual behaviors that appear detached from authentic intimacy or mutual recognition, with associated distress for both partners (Scimeca et al., 2013). Parallel research on self- and partner-objectification in romantic relationships documents that perceiving oneself or one’s partner primarily as a sexual object is associated with lower relationship satisfaction and, in some cases, reduced sexual satisfaction, partly mediated by exposure to objectifying media and internalized appearance-focused norms (Zurbriggen et al., 2011). Together, these literatures suggest that when sexuality is organized around control of the body, confirmation of sexual competence, and the visual/functional use of the partner, relational outcomes are likely to be compromised.

Notwithstanding these convergences, the current evidence base remains fragmented. Research on orgasm scripts tends to focus on gendered expectations and orgasm frequency without systematically integrating constructs such as sexual narcissism or partner objectification. Conversely, studies on sexual narcissism or objectification typically examine global relationship and sexual satisfaction as distal outcomes but do not unpack how orgasm-centered practices, faked orgasms, or masturbatory use of the partner may mediate these associations. Moreover, psychodynamic distinctions between autoerotic sexuality and object-related sexuality—central to clinical theorizing about narcissistic configurations and difficulties in recognizing the partner as a separate subject—have rarely been explicitly connected to contemporary empirical work on sexual scripts and couple satisfaction. As a result, we lack an integrated conceptual framework that links orgasm-centered, partner-as-instrument sexual patterns with established psychosocial predictors of couple satisfaction.

The present conceptual paper aims to address this gap by proposing a theoretically grounded continuum that extends from autoerotic partner use—where the partner functions largely as a masturbatory device for orgasm regulation and narcissistic validation—to relationally co-constructed sexuality, in which orgasm is embedded within intersubjective attunement, affect sharing, and co-authored meaning. Drawing on empirical research on sexual satisfaction, orgasm scripts, sexual narcissism, alexithymia, and partner objectification, we synthesize current findings to delineate how different configurations along this continuum are likely to influence couple satisfaction. Specifically, our aims are: (a) to integrate scattered empirical evidence on orgasmic focus, sexual detachment, sexual narcissism, and partner objectification in couple relationships; (b) to articulate a conceptual model of orgasmic sexuality that distinguishes masturbatory use of the partner from relational co-construction; (c) to derive implications for assessment, couple therapy, and psychoeducational interventions aimed at fostering more mutual, subjectivity-recognizing sexual patterns; and (d) to generate testable hypotheses for future quantitative and qualitative studies that examine the impact of orgasm-centered versus relationally co-constructed sexuality on satisfaction trajectories in diverse couple configurations. In doing so, the paper aligns with the Special Issue’s emphasis on psychological and social influences on couple satisfaction, while introducing a novel lens on how the microdynamics of orgasm and sexual subjectivity may sustain or erode relational well-being over time.

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background: Orgasmic Sexuality and Couple Satisfaction

2.1. Orgasm as Outcome vs Orgasm as Relational Process

Across late-modern Western societies, orgasm has been progressively constructed as a privileged marker of “successful” sexual activity, giving rise to what feminist and sociological authors have termed the orgasm imperative and, more specifically, the coital imperative in heterosexual scripts: sex is considered “complete” only when it culminates in penile–vaginal penetration and orgasm, most often male. Potts, in a seminal deconstruction of heterosexual orgasm, showed how clinical, media and lay discourses converge in presenting orgasm as a compulsory endpoint, a sign of normality, health and relational adequacy, while rendering non-orgasmic or non-coital sexualities deviant or deficient (Potts, 2000). This goal-oriented framing supports a transactional, performance-based approach to sexual encounters, in which the partner is easily reduced to a means for delivering an outcome (orgasm), rather than a subject with whom meanings and affects are co-constructed.

Qualitative and social-representation studies deepen this picture by examining the symbolic meanings attributed to orgasm. Lavie-Ajayi and Joffe, using social representations theory, found that female orgasm is simultaneously constructed as a biological reflex and as a signifier of intimacy, validation and “being loved”, with strong moral overtones about what “proper” heterosexual sex should look like (Lavie-Ajayi & Joffe, 2009). Séguin and Blais, in a mixed-methods study of partnered orgasm, identified multiple layers of meaning – from bodily pleasure to confirmation of desirability, proof of partner competence and relational barometer – and showed that discordance between personal meanings and normative scripts is associated with ambivalence, anxiety and faking (Séguin & Blais, 2019). These findings suggest that orgasm cannot be reduced to a discrete event or outcome; it functions as a dense symbolic node within the couple’s shared narrative.

Empirically, Mah and Binik’s psychometric work on the Orgasm Rating Scale demonstrated that orgasmic pleasure and satisfaction are more strongly associated with the cognitive–affective dimensions of the orgasm experience (relaxation, emotional intimacy, ecstasy) than with the sensory or anatomical characteristics of genital sensations (Mah & Binik, 2005). In both solitary and partnered contexts, orgasm was rated as more gratifying when embedded in feelings of closeness and psychological intensity, and when it occurred in the context of higher relationship satisfaction (Mah & Binik, 2005). These data empirically support the intuition that orgasm is not only the end-point of a physiological sequence, but a relationally and symbolically mediated process.

At the same time, work on sexual satisfaction has highlighted the normative and justice-laden dimensions of how “good sex” is evaluated. McClelland’s concept of intimate justice argues that sexual satisfaction ratings often reflect broader issues of equity, voice and power in relationships, and that simple frequency-based indices (including orgasm counts) may obscure structural inequalities in whose pleasure matters and whose does not (McClelland, 2010). From this vantage point, an orgasm-centred metric of sexual quality risks reinforcing asymmetries: a partner can report “high satisfaction” while instrumentalising the other as an object for self-confirmation, especially if the latter’s dissent or discomfort is muted.

Large-scale survey work has documented the persistence of an “orgasm gap”, with women less likely than men to reach orgasm in partnered heterosexual sex across the life span, even when controlling for age and health status. A recent life-course analysis using nationally representative samples showed that gendered differences in orgasm frequency remain robust from young adulthood into later life, with women consistently reporting lower rates of orgasm than men in comparable partnered encounters (Gesselman et al., 2024). Importantly, the gap is not uniform across sexual practices: acts that explicitly incorporate clitoral stimulation and responsive partner behaviour reduce the disparity, underlining the centrality of context and partner responsiveness rather than the mere occurrence of penetration (Gesselman et al., 2024).

More fine-grained dyadic research suggests that the association between orgasm and couple functioning is not strictly linear. Janssen and colleagues, in a community sample of women in Aotearoa/New Zealand, found that orgasmic pleasure was positively associated with sexual relationship satisfaction, but the relationship showed signs of diminishing returns at higher levels of orgasmic focus (Janssen et al., 2025). Women who reported very high pressure (self- or partner-imposed) to achieve orgasm, or who framed orgasm as an obligatory marker of “success”, were more likely to describe relational strain, performance anxiety and disconnection despite relatively frequent orgasms (Janssen et al., 2025). These findings point to a potential curvilinear pattern: insufficient orgasmic pleasure is linked to dissatisfaction, but an over-investment in orgasm as a performance metric can also erode intimacy.

Taken together, these strands of evidence support a conceptual distinction that is central for the present paper: (a) orgasm as an outcome—a quantifiable endpoint used as an indicator of sexual adequacy and relational success, and (b) orgasm as a relational process—a moment within an intersubjective field, whose quality depends on mutual recognition, affective attunement and shared meaning. The first configuration lends itself to partner-as-masturbatory-object dynamics: the other is primarily a vehicle for self-regulation and discharge. The second situates orgasm within a co-constructed narrative, where each partner’s subjectivity, vulnerability and responsiveness are integral to the experience.

2.2. Orgasmic Scripts in Late-Modern Sexuality

Late-modern sexual cultures, especially among younger cohorts, are increasingly shaped by pornography, mainstream media and hookup practices. These contexts disseminate highly standardised sexual scripts that are typically performance-oriented, genitocentric and outcome-driven. Garcia and colleagues’ review of hookup culture highlights how casual encounters, often structured around alcohol use and peer norms, prioritise rapid escalation from minimal intimacy to genital acts and intercourse, with limited space for negotiation of meaning or mutual vulnerability (Garcia et al., 2012). Within these scripts, orgasm—frequently male—is portrayed as the expected closure of the interaction, while emotional intimacy is bracketed or even framed as antithetical to the desired “no strings attached” format (Garcia et al., 2012).

Analyses of pornographic and sexualised media content converge on a similar pattern. Bridges and Morokoff, in a dyadic study of sexual media use, found that higher individual consumption of sexual media was associated with more performance-oriented attitudes and, for men in particular, with lower relationship satisfaction when use was discrepant between partners (Bridges & Morokoff, 2011). Although their design was correlational, the authors discuss how sexual media often present sex as a sequence of scripted acts culminating in male orgasm, with limited depiction of negotiation, aftercare or female pleasure beyond the visible orgasm event (Bridges & Morokoff, 2011).

From a critical gender perspective, Willis and colleagues have shown how phallocentric imperatives—norms that centre penis-in-vagina intercourse and male orgasm as the defining elements of “real sex”—shape women’s orgasm experiences and expectations (Willis et al., 2018). Women who endorsed stronger phallocentric beliefs reported more difficulty achieving orgasm, more faking and greater internal pressure to conform to the script, even when this implied silencing their own preferences and comfort (Willis et al., 2018). Combined with qualitative studies of social representations of orgasm, which show that both women and men often interpret orgasm as proof of desirability, sexual competence and relational worth (Lavie-Ajayi & Joffe, 2009; Séguin & Blais, 2019), these data suggest that orgasm is routinely mobilised as a social credential rather than a purely embodied experience.

In this media-saturated, hook-up-enabled landscape, orgasm is frequently framed as a metric: one should orgasm, preferably quickly and visibly; failure to do so risks being read as personal or relational failure. The sequence “foreplay–penetration–(male) orgasm” becomes naturalised as the default template, marginalising alternative erotic pathways and non-goal-oriented forms of sexual contact. Such scripts are fertile ground for partner-as-instrument configurations: if the main task is to produce (or display) orgasm, the partner’s interiority can be relegated to the background.

2.3. Link to Couple Satisfaction

Empirical work on couple satisfaction consistently shows that sexual functioning and relationship quality are moderately to strongly correlated. However, more nuanced analyses indicate that this association is mediated by variables such as sexual communication, emotional intimacy and perceived mutuality, rather than by orgasm frequency alone.

Meta-analytic evidence on couples’ sexual communication shows that open, responsive discussion of sexual needs, boundaries and pleasure is positively associated with multiple dimensions of sexual function (desire, arousal, orgasm) in both partners (Mallory et al., 2019). A second meta-analysis by the same group demonstrates that sexual communication is also linked to higher sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction, with effects that remain robust after controlling for sexual frequency and relationship length (Mallory, 2022). These findings suggest that it is not merely what couples do sexually, but how they talk about it and symbolically integrate it, that predicts satisfaction.

Dyadic path analyses further support this relational framing. Yoo and colleagues found that couple communication predicted both emotional and sexual intimacy, which in turn mediated the association between communication and relationship satisfaction in a sample of married and cohabiting couples (Yoo et al., 2014). Sexual satisfaction entered the model as a partially mediating variable, but its effect was largely channelled through perceived intimacy and responsiveness (Yoo et al., 2014). In other words, orgasm and other sexual outcomes contributed to satisfaction primarily when embedded in a context of mutual openness and emotional connection.

Roels and Janssen, studying young heterosexual couples, observed that sexual frequency and sexual communication were both associated with sexual satisfaction, but that only communication showed a robust, independent link with relationship satisfaction once other variables were controlled (Roels & Janssen, 2020). Their results align with Mah and Binik’s findings that orgasmic pleasure and satisfaction are more strongly tied to cognitive–affective dimensions and relationship quality than to sheer sensory intensity (Mah & Binik, 2005). Together, these data indicate that orgasm can be relationally bonding when it is part of a mutually responsive, communicatively rich sexual climate, but may have limited or even negative relational impact when pursued as an isolated performance goal.

From the vantage point of the present conceptual paper, the literature can thus be read as pointing to a continuum. At one pole lies an autoerotic use of the partner, in which orgasm functions as a self-regulatory discharge, a confirmation of desirability or competence, and the partner’s subjectivity is only minimally engaged. At the other pole lies a relationally co-constructed sexuality, in which orgasm—whether frequent or not—is embedded in shared meanings, negotiated scripts, emotional intimacy and communicative mutuality. The same orgasm frequency may correspond to very different positions on this continuum, depending on how much the partner is treated as an object versus a co-author of the experience. Taken together, these findings can be organised into a set of key empirical contributions that map the links between orgasmic focus and couple satisfaction. These studies are summarised in

Table 1.

3. Psychodynamic Foundations: Autoerotism, Object Use, and Partner as Masturbatory Object

3.1. From Autoerotism to Object-Related Sexuality

Classical psychoanalytic theory has conceptualized sexuality as developing from an initial phase of autoerotic bodily excitation to later forms of object-related love. In the early Freudian metapsychology, infantile sexuality is understood as a constellation of polymorphous, non-objectal pleasures, organised around erogenous zones rather than around a love object. In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, Freud (1905/1953) describes infantile sexuality as primarily autoerotic, with the choice of an external object emerging only secondarily in development. More recent historical and systematic readings of Three Essays have highlighted how, in the 1905 version, sexuality is indeed primarily defined as autoerotic drive activity and only secondarily as object-seeking, thereby problematizing any linear, teleological transition from self-stimulation to mature genital love (Van Haute & Westerink, 2016). These readings emphasise that the question of how autoerotic enjoyment becomes woven into the recognition of another subject remains, in Freud, a partially unresolved theoretical problem (Freud, 1905/1953; Van Haute & Westerink, 2016).

Within this framework, Abraham’s libidinal phase theory can be reread not only as a developmental stratification of zones and functions, but also as a progressive reorganisation of the relation between self-pleasure and object-relatedness. His account of the shift from predominantly oral and anal forms of self-directed satisfaction to genital aims underscores that the emergence of “object love” does not abolish autoerotic trends but integrates them into increasingly complex relational configurations (Abraham, 1924/1948). The persistence of archaic, self-directed modes of pleasure in adult sexuality provides a metapsychological background for understanding orgasm-centred, masturbatory uses of the partner.

Winnicott’s contribution to object usage is crucial for thinking the partner’s position in sexual life. In “The Use of an Object”, he distinguishes between relating to an object as an extension or mirror of the self and using an object that survives the subject’s destructive impulses (Winnicott, 1969). Object usage entails a psychic process in which the other is experienced, attacked, and yet continues to exist as separate, thereby becoming “real” in the subject’s internal world. Ogden’s contemporary rereading stresses that destruction, in Winnicott’s sense, is not merely aggression but the testing of the object’s alterity: the other is no longer a fantasy derivative but an external centre of subjectivity, capable of resisting appropriation and of co-constructing meaning (Ogden, 1994).

If we transpose these ideas to the domain of orgasmic sexuality, the difference between autoerotism and object-related sexuality can be reformulated as a difference between using the partner as a sensual extension of the self and engaging with a subject whose independent experience reshapes the sexual encounter. In orgasm-centred scripts that treat the partner as a masturbatory surface, the other is not “used” in Winnicott’s sense (as a real object surviving destruction) but rather “relied upon” as a compliant apparatus for the discharge of tension. The partner’s experiential world—desire, hesitation, ambivalence, shame, pleasure—is minimally mentalised and may be registered only insofar as it facilitates or obstructs the individual’s autoerotic trajectory towards orgasm.

Conversely, in relationally co-constructed sexuality, orgasm is embedded in a field of mutual recognition. Autoerotic components persist but are modulated through ongoing negotiation with an object whose responses are affectively and symbolically meaningful. The partner’s enjoyment, vulnerability, and limits become part of the subject’s own erotic experience, in line with contemporary formulations of self psychology and intersubjective psychoanalysis that frame the self as constituted in and through selfobject relationships (Hartmann, 2009). From this angle, couple sexuality may be seen as a privileged arena where the long developmental trajectory from autoerotism to object love is continually replayed, potentially regressing towards self-centred orgasmic imperatives or progressing towards recognition of the partner as a co-author of desire.

3.2. The Partner as “Animated Sexual Prop”: Narcissistic and Borderline Organizations

In clinical practice, one frequently encounters configurations in which the partner is treated less as a subject and more as an “animated sexual prop”: a living body that can move, respond, and provide validation, yet is not fully acknowledged as having a complex internal world. In such orgasm-centred arrangements, the sexual act functions as a form of autoerotic discharge on or through the partner rather than with the partner. The orgasm becomes an index of self-confirmation—of potency, desirability, control—while the relational dimension is drastically underdeveloped.

Contemporary research on narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) offers a useful framework for understanding these patterns. Psychodynamic and dimensional models converge in depicting NPD as characterized by a fragile, dysregulated sense of self, dependent on external mirroring, and by pervasive disturbances of empathy and intimacy (Ronningstam, 2011; Weinberg & Ronningstam, 2022). In this context, sexual encounters are often mobilized as arenas for restoring self-esteem and defending against feelings of emptiness or insignificance. Weinberg and Ronningstam (2022) emphasise that individuals with pronounced narcissistic traits may use sexuality to achieve dominance, confirm superiority, or avoid dependency, thereby compromising mutuality and genuine erotic reciprocity.

Empirical work on empathy in NPD further clarifies how the partner can become an instrumentally used object. Baskin-Sommers and colleagues document selective impairments in affective and cognitive empathy: while individuals with narcissistic traits may understand others’ states at a cognitive level, they show reduced capacity or motivation to engage with the partner’s emotional experience (Baskin-Sommers et al., 2014). This pattern supports a mode of sexual relating in which the subject can read the partner’s signals well enough to secure orgasm or admiration but remains largely indifferent to their subjective meaning.

Borderline personality organization introduces a different, though related, dynamic. In borderline states, intense fears of abandonment and identity diffusion coexist with oscillations between idealisation and devaluation of the partner (Kernberg, 1975). Mentalization-based formulations describe how under affective load, the capacity to envisage the other’s mind collapses, leading to concrete, bodily enactments of attachment and aggression (Fonagy & Target, 1997; Bateman & Fonagy, 2004). In sexual encounters, this may manifest as clinging, intrusive, or controlling sexuality, in which orgasm functions both as proof of fusion (“we are one”) and as a defence against catastrophic anxieties about separateness. The partner’s body is then drafted into regulating unbearable internal states, again blurring the distinction between shared erotic experience and autoerotic use.

Psychoanalytic self psychology and its later developments offer a complementary lens. The partner can function as a selfobject, implicitly recruited to provide mirroring (“I am desirable”), idealisation (“I am connected to someone powerful”), or twinship (“we are the same”) (Kohut, 1971). When selfobject functions are fragile or chronically unmet, sexual activity may be over-invested as a channel for securing these experiences, so that the partner’s subjectivity is sacrificed to the self’s regulatory needs. Hartmann’s integrative review underlines how self-psychological concepts intersect with attachment and mentalization theories: failure to internalise reliable selfobject experiences and to develop reflective function predisposes to relational configurations where others are treated as regulatory devices rather than as co-constitutive subjects (Hartmann, 2009).

In such scenarios, the partner effectively becomes a “masturbatory tool with a mind ignored”: a body animated enough to provide contingent responses, but not sufficiently recognised to transform the subject’s internal drama. The orgasm, here, seals the closure of an autoerotic circuit rather than marking the culmination of a shared, mutually recognised erotic process.

3.3. Integrating Psychodynamic and Social-Psychological Views

The psychodynamic constructs outlined above—autoerotism, object usage, selfobject functions, narcissistic organisation—can be fruitfully integrated with social-psychological notions such as sexual objectification, sexual detachment and partner commodification. Social-psychological research has shown that objectifying attitudes reduce partners to their bodies or sexual functions, are associated with diminished empathy and perspective-taking, and correlate with lower relationship quality, especially when coupled with rigid gender norms and performance-oriented sexual scripts (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Ramsey & Hoyt, 2015). These findings converge with psychoanalytic descriptions of narcissistic and autoerotic sexuality, in which the other is primarily a vehicle for self-regulation and gratification.

Fonagy and Target’s model of reflective function provides a bridge: where mentalization is intact, the partner is experienced as a mind with its own intentions and affects; where mentalization collapses, the partner regresses to a thing-like status, even if consciously cherished (Fonagy & Target, 1997). Bateman and Fonagy’s work on mentalization-based treatment for borderline personality disorder demonstrates that enhancing reflective function not only reduces impulsive and self-destructive behaviour but also improves the capacity for stable, mutually attuned relationships (Bateman & Fonagy, 2004, 2010). Extrapolated to sexuality, this suggests that therapeutic work which restores the ability to imagine the partner’s mind can shift orgasm-centred, masturbatory use of the other towards more co-constructed, dialogical sexual scripts.

Rowe’s extension of self-psychological theory with the concept of the “undifferentiated selfobject” further nuances this integration. He describes patients whose internal world is organised around a diffuse expectation that “something more” should be provided by others, yet without clear differentiation of what that “more” entails; others are recruited to sustain a sense of vitality and possibility but are not fully recognised as separate centres of subjectivity (Rowe, 2012). In orgasm-centred couple sexuality, this undifferentiated selfobject dynamic may translate into an insatiable, repetitive pursuit of ever more intense sexual experiences, with partners functioning as interchangeable conduits for an inchoate need that cannot be symbolised.

Taken together, these perspectives support the central conceptual move of the present paper: to frame orgasmic couple sexuality along a continuum from autoerotic partner use to relational co-construction. At one pole, orgasm is pursued as an almost solitary event, with the partner instrumentalised as a masturbatory apparatus. At the other, orgasm emerges within a process of mutual recognition, where each subject’s mind and body actively shape the shared erotic space. The position of a given couple along this continuum is hypothesised to depend on the interplay between personality organisation (especially narcissistic and borderline traits), developmental history of selfobject experiences, and current levels of reflective function and mentalization (Fonagy & Target, 1997; Hartmann, 2009; Bateman & Fonagy, 2010).

Text Box 1. Clinical vignette of orgasm-centred “masturbatory” couple sexuality

Luca (38) and Marta (35), a heterosexual couple in a stable relationship of seven years, seek therapy reporting “sexual incompatibility” and “growing distance”. They describe a high frequency of intercourse—on average four to five times per week—with almost invariable orgasms for Luca and more variable, often absent orgasms for Marta. Luca presents their sexual life as “objectively very good”, emphasizing his ability to maintain erections, delay ejaculation and “make things exciting”. He assumes that Marta’s difficulty climaxing is “mostly psychological” and interprets her refusals as “moodiness” or “hormonal issues”.

In individual sessions, Marta reports feeling “used” and “pressed” during sex. She notes that foreplay is brief and focused on her breasts and genitals, that Luca rarely inquires about what she would like, and that attempts to slow down or change the script are met with irritation or jokes about “overthinking”. She often dissociates during intercourse, focusing on “getting it over with” to avoid conflict, and experiences increasing resentment and detachment. Outside the bedroom, she describes Luca as generally kind but emotionally unavailable, especially in moments when she feels vulnerable or distressed.

From a psychodynamic perspective, Luca’s sexuality appears organised around autoerotic confirmation: orgasm functions as proof of potency and desirability, while Marta’s body serves as the primary stage on which these self-states are enacted. His capacity to mentalise Marta’s subjectivity is limited; he anticipates her reactions in terms of compliance or resistance rather than curiosity about her experience. Marta, in turn, enacts a compliant position that protects the bond at the cost of her own desire, reinforcing the masturbatory character of the sexual encounters. The couple’s high sexual frequency thus coexists with profound relational dissatisfaction, illustrating how orgasm-centred sexuality can operate as a form of mutual alienation rather than intimacy.

4. Empirical Constructs Converging on Partner-as-Instrument: Sexual Detachment, Sexual Narcissism, and Objectification

4.1. Sexual Detachment: Partner as Predominantly Sexual Object

Within the empirical literature, sexual detachment generally designates a pattern of sexual engagement characterized by attenuated affective involvement, a sense of emotional distance from one’s partner, and the use of sexual activity primarily as an instrument for tension discharge, self-regulation, or self-confirmation. In Italian research using the Sex and the Average Woman (or Man) Scale (SAWM), factor-analytic work has consistently identified a sexual detachmentdimension capturing attitudes such as “sex without feelings”, emotional coldness, and avoidance of intimacy during sex in community samples of young adults (Chisari et al., 2017).

Scimeca and colleagues, in a sample of heterosexual university students, showed that higher alexithymia scores were associated with lower sexual satisfaction and higher levels of sexual detachment in women, and with sexual shyness and nervousness in both genders (Scimeca et al., 2013). Importantly, sexual detachment in this work is not merely a cognitive stance, but part of a broader interpersonal style marked by difficulty in experiencing and expressing emotions, negative affectivity, and relational discomfort. In parallel, a second study using the SAWM in an Italian university sample found that higher Internet addiction scores were associated with low sexual satisfaction and high sexual detachment, suggesting that emotionally disconnected sexual attitudes may form part of a broader pattern of dysregulated, compulsive behaviours (Chisari et al., 2017).

More broadly, work on alexithymia and sexual risk-taking indicates that difficulty identifying and describing feelings partially mediates the association between childhood maltreatment and risky sexual behaviour in young adults (Hahn et al., 2016). In Hahn et al.’s structural equation model, alexithymia channelled the impact of early adversity on risky sexual practices via heightened negative urgency, problematic alcohol use, and a needy interpersonal style, suggesting that sexual encounters can become arenas for the evacuation or modulation of poorly mentalised affects. Although sexual detachment is not always explicitly measured, this cluster of findings converges on a picture in which impaired emotional awareness and regulation favour sexual exchanges that are instrumentally motivated, low in intimacy, and focused on immediate relief or self-confirmation.

Taken together, these data support a working definition of sexual detachment as:

statistically associated with alexithymia, negative affect, and interpersonal problems;

behaviourally expressed as emotionally cold, low-intimacy sexual activity, often combined with elevated risk-taking (multiple partners, pornography-related compulsivity);

phenomenologically compatible with experiencing the partner primarily as a sexual object or regulator of internal tension, rather than as a co-constructing relational subject.

In psychodynamic terms, this empirical pattern is congruent with an autoerotic mode of functioning in which the other’s body is recruited as a “surface” for the evacuation or modulation of affects, rather than recognised as a mind-bearing subject whose experience could transform the encounter.

4.2. Sexual Narcissism and Autoerotic Focus

Sexual narcissism has been conceptualised as a domain-specific constellation of grandiosity, entitlement, lack of empathy, and exploitative attitudes in the sexual sphere, including preoccupation with one’s own pleasure, desirability, and performance, and diminished concern for the partner’s satisfaction and subjectivity. The Sexual Narcissism Scale (SNS) developed by McNulty and Widman assesses four components—sexual exploitation, sexual entitlement, low sexual empathy, and inflated sense of sexual skill—each capturing a specific facet of self-focused, partner-disregarding sexuality (McNulty & Widman, 2013).

In a longitudinal study of newlyweds, sexual narcissism at baseline predicted lower initial levels and steeper declines in both sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction over the first years of marriage, even after controlling for global narcissism and other personality traits (McNulty & Widman, 2013). Individuals high in sexual narcissism tended to report relatively high initial sexual excitement and performance orientation, but their partners’ dissatisfaction increased over time, and couple-level trajectories of satisfaction deteriorated. These findings strongly support the conceptualisation of sexual narcissism as a relational risk factor, despite an apparent early “advantage” in erotic intensity.

A second longitudinal analysis drawing on the same newlywed samples showed that sexual narcissism predicted a higher likelihood of extradyadic sex during the first years of marriage, independent of baseline levels of marital and sexual satisfaction and global narcissism (McNulty & Widman, 2014). The association was driven by all four facets of sexual narcissism—sexual exploitation, entitlement, lack of sexual empathy, and grandiose sexual skill—indicating that a broadly self-serving sexual motivational structure predisposes to boundary violations when relational constraints collide with self-focused goals.

From the vantage point of the present conceptual paper, sexual narcissism can be read as an empirically grounded embodiment of autoerotic partner use:

the sexual encounter is structured around the self (own pleasure, own image as skilled and desirable);

the partner’s experience is instrumental and secondary;

relational boundaries (e.g., fidelity, responsiveness) are more readily transgressed when they conflict with self-enhancing aims.

Even when orgasm is shared, the underlying motivational structure remains essentially autoerotic: orgasm becomes proof of one’s sexual worth or power, and the partner’s subjectivity is recruited as a means of stabilising fragile self-esteem rather than as a co-authored locus of pleasure and meaning.

4.3. Partner Sexual Objectification and Power/Control

Objectification theory has documented how perceiving individuals primarily as bodies or body parts, reducible to their sexual utility, is associated with a wide range of negative psychological outcomes. When this process occurs within romantic relationships—partner sexual objectification—the partner is predominantly seen as a sexual body to be evaluated, monitored, and used, rather than as a subject with thoughts, desires and vulnerabilities.

In a seminal study, Zurbriggen and colleagues examined self- and partner-objectification in young adults in committed relationships, showing that partner objectification was associated with lower relationship satisfaction and lower sexual satisfaction (Zurbriggen et al., 2011). Structural equation modelling suggested that consumption of sexually objectifying media predicted partner objectification, which in turn predicted reduced relationship satisfaction, identifying partner objectification as a mechanism through which cultural objectifying scripts penetrate the couple system.

More recently, Brock and co-authors developed the Inventory of Partner Sexual Objectification (IPSO), a multidimensional measure assessing the extent to which individuals feel reduced to their appearance and sexual attributes for their partner’s use (Brock et al., 2025). The IPSO comprises a higher-order factor of global partner objectification and specific subscales (e.g., body autonomy denial, body neglect, reduced unconditional body appreciation), and demonstrates robust psychometric properties in community samples of adults in committed relationships. Higher IPSO scores are associated with lower relationship satisfaction, more sexual pressure, and greater conflict around sexual frequency and practices, even after controlling for general relationship conflict and self-objectification (Brock et al., 2025).

Across these studies, partner sexual objectification is typically associated with:

asymmetries of power and control (the objectifying partner disproportionately defining sexual timing, practices, and acceptability);

diminished mutuality and self-disclosure in the sexual sphere;

increased vulnerability to negative body-related emotions (shame, self-surveillance) in the objectified partner, which in turn undermine sexual and relational well-being.

From the perspective advanced here, partner sexual objectification maps onto the more extreme end of the partner-as-instrument pattern: the partner is literally treated as an “animated sexual prop”, whose primary relevance lies in providing sexual gratification and external validation, while their subjective experience is marginalised.

4.4. A Convergent Empirical Phenotype: Orgasm-Centred, Detached, Objectifying Sexuality

Bringing together the constructs reviewed above—sexual detachment, sexual narcissism, and partner objectification—allows us to delineate a convergent empirical phenotype of relational sexuality that is orgasm-centred, emotionally detached, and instrumentally objectifying.

First, sexual detachment captures the affective tone of the sexual relationship: low emotional involvement, limited empathy, and a tendency to keep the partner at psychological distance during sexual encounters (Scimeca et al., 2013; Chisari et al., 2017). Sexual activity is pursued, but emotional intimacy is actively minimised; sex functions primarily as an affect-regulation strategy or as a habitual routine that does not significantly engage the self in relational terms.

Second, sexual narcissism specifies the motivational structure: orgasm and sexual performance are central as sources of self-enhancement, self-soothing, and self-confirmation (McNulty & Widman, 2013, 2014). In this configuration, the partner’s body becomes a stage on which the sexually narcissistic individual enacts scripts of conquest, desirability, and control; the other’s inner experience is not so much explicitly denied as rendered largely irrelevant to the meaning of the encounter.

Third, partner sexual objectification describes the perceptual frame through which the partner is apprehended: the partner is primarily a sexual body or assemblage of sexually relevant parts and functions, valued for compliance, appearance, and performance rather than for subjectivity, reciprocity, or co-authored meaning (Zurbriggen et al., 2011; Brock et al., 2025).

When these three dimensions co-occur with high orgasm goal focus (the “orgasm imperative” discussed in

Section 2), the resulting sexual pattern displays several characteristic features:

-

High emphasis on orgasm and technique.

Sexual encounters are structured around the achievement of orgasm—often the orgasm of the more powerful or narcissistic partner—as the central criterion of “success”. Performance orientation is strong, frequently informed by pornographic scripts and media representations.

-

Low recognition of the partner’s inner world.

The partner’s feelings, fantasies, and limits are marginal in the subjective organisation of the encounter. Communicative processes (negotiation of boundaries, exploration of mutual desires) are minimal, and the partner is implicitly positioned as an instrument of gratification.

-

Ambivalent or poor couple outcomes over time.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal data indicate that such a configuration can be associated initially with high sexual excitement, but over time predicts lower sexual satisfaction, lower relationship satisfaction, and increased relational instability, including infidelity (McNulty & Widman, 2013, 2014).

In the context of the present Special Issue, this convergence suggests that it is not orgasm frequency per se that matters for couple satisfaction, but the relational organisation within which orgasm occurs. Orgasm-centred sexuality can be bonding and protective when embedded in mutual recognition, responsiveness, and shared meaning. Conversely, when orgasm is pursued within a pattern of detachment, narcissism, and objectification, the couple is exposed to erosion of satisfaction, heightened conflict, and vulnerability to behaviours that undermine trust (e.g., coercive practices, chronic infidelity). In order to operationalize the “partner-as-instrument” pattern for empirical research,

Table 2 summarizes the main constructs and validated self-report measures, together with their key correlates and documented links with sexual and couple satisfaction (

Table 2).

The table summarizes key constructs and psychometric tools relevant for operationalizing partner instrumentalization in orgasm-centered sexuality. For each construct, the table reports a brief definition, the main validated self-report scales (including example content), typical personality and affective correlates (e.g., narcissistic traits, alexithymia, insecure attachment, dark traits), and documented associations with sexual and couple satisfaction and relationship stability.

As summarised in

Table 2, these constructs can be organised into an empirical convergence model in which traits and dispositions influence sexual cognitive–affective patterns, which then predict sexual and relational outcomes and, ultimately, autoerotic versus relational patterns of couple sexuality (

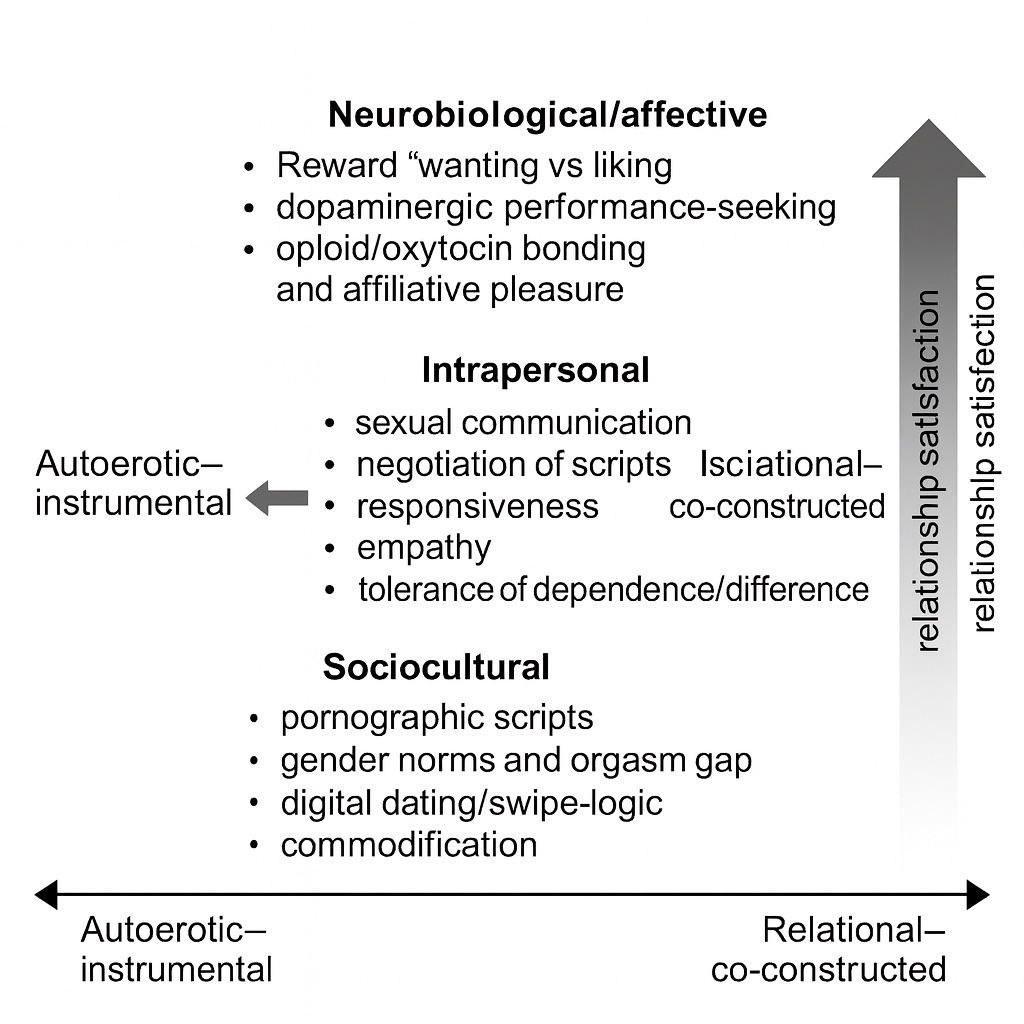

Figure 1).

Figure 1 Empirical convergence model linking traits, sexual cognitive–affective constructs and relational outcomes.

This integrative, empirically anchored model provides the bridge to the subsequent sections, which will formalise the autoerotic–relational continuum, articulate a multi-level conceptual framework, and derive clinically and psychoeducationally relevant implications for assessment and intervention in couples presenting with orgasm-centred, partner-as-instrument sexual patterns.

5. A multi-Level Conceptual Model: from Masturbatory Partner Use to Co-constructed Relational Sexuality

5.1. The Autoerotic–Relational Continuum

The material developed in the previous sections can be formalised as a continuum of couple sexuality that runs from autoerotic partner use to relationally co-constructed sexuality. At the autoerotic pole, the partner is experienced predominantly as an instrument for discharge and self-confirmation: a “masturbatory object” endowed with minimal subjective depth. Sexual interaction is organised around tension reduction, orgasm achievement and performance validation; the other’s mind is only weakly represented and rarely becomes a focus of curiosity or concern.

At the relational pole, sexual activity is embedded in an intersubjective field: the partner is mentally represented as a separate subject, with their own needs, vulnerabilities and erotic imaginaries. Here, orgasm is not abolished or devalued, but relocated—from being the primary endpoint of the act to being one component of a broader process of mutual recognition, affect regulation and meaning-making. Pleasure is not only genital but also relational, linked to feeling desired, seen and emotionally held. Longitudinal and dyadic studies grounded in attachment theory suggest that sexual exchanges integrated with proximity-seeking, responsiveness and secure-base processes show stronger and more stable associations with relationship quality and stability than sexual activity considered in isolation (Conradi et al., 2021; Freeman et al., 2023).

Empirical work on sexual motives helps clarify how couples move along this continuum. Across multiple samples, approach-oriented sexual goals (e.g., seeking intimacy, expressing affection, fostering closeness) are associated with higher sexual and relationship satisfaction for both partners, whereas avoidance-oriented goals (e.g., preventing conflict, avoiding rejection, reducing guilt) predict lower satisfaction and more distress (Impett et al., 2005; Muise et al., 2013). In our framework, approach-based motives tend to pull the dyad toward the relational co-construction pole because they presuppose a minimal level of mentalization of the partner and an investment in the quality of the shared emotional field. Avoidance-based motives, in contrast, easily drift toward an instrumental, compliance-driven sexuality, where the act is performed to neutralise anxiety, anger or abandonment fears rather than to engage with the other’s subjectivity.

Crucially, the continuum is not conceived as a categorical distinction between “healthy” versus “pathological” sex. All couples oscillate along this axis over time and across contexts: moments of more autoerotic, self-focused sexuality coexist with moments of high mutuality and co-regulation. What differentiates couples clinically is the degree of rigidity with which they remain anchored near the autoerotic pole, and the extent to which their sexual scripts allow—or actively inhibit—movement toward relational co-construction. The present model therefore frames orgasm-centred, partner-as-instrument sexuality not as a discrete syndrome but as a phenotypic configuration emerging from the interaction of intrapsychic organisation, dyadic negotiation and sociocultural scripts.

5.2. Levels of Analysis

To render this continuum empirically tractable and clinically useful, we articulate it across four nested levels of analysis: intrapersonal, interpersonal, sociocultural and neurobiological/affective. These levels are analytically distinct but dynamically interwoven; each provides specific entry points for assessment, research and intervention.

Intrapersonal level. At this level, the continuum is shaped by personality traits, attachment patterns, emotion-regulation capacities and internalised object relations. Individual differences in attachment anxiety and avoidance, as well as in the ability to integrate self-focused and other-focused concerns, are robustly associated with sexual desire, sexual satisfaction and overall couple functioning (Hughes, 2014; Conradi et al., 2021; Freeman et al., 2023).

Sexual desire discrepancy provides a particularly informative window. Studies with community and new-parent couples consistently show that mismatches in partners’ sexual desire are common and frequently associated with lower sexual and relationship satisfaction, although effect sizes and directions vary depending on who is the higher-desire partner and on contextual factors (Davies et al., 1999; Sutherland et al., 2015; Rosen et al., 2018). From the perspective of the present model, desire discrepancy is not merely a quantitative gap in libido; it often indexes qualitative differences in where each partner sits along the autoerotic–relational axis. One partner may primarily seek sex as self-regulatory discharge, while the other seeks sex as relational co-construction, generating chronic misunderstandings.

Strategies used to cope with such discrepancies further reveal the intrapersonal orientation of the sexual script. When partners resort predominantly to solitary or avoidant strategies (withdrawal, secret masturbation, sexual shutdown), desire discrepancies tend to co-occur with lower sexual and relationship satisfaction. In contrast, collaborative strategies that involve negotiation, disclosure and creative adjustment—such as varying activities, integrating masturbation into shared erotic play, or explicitly re-negotiating frequency—are associated with better outcomes, partly via enhanced sexual communication and satisfaction (Mallory et al., 2019; Mallory, 2022; Galizia et al., 2023). These patterns dovetail with our notion that movement toward the relational pole requires an internal capacity to tolerate dependence, difference and frustration without collapsing into autoerotic retreat or devaluation of the other.

Interpersonal level. At the dyadic level, the continuum is expressed through patterns of communication, responsiveness and script negotiation. Meta-analytic evidence indicates that sexual communication—particularly its quality—is positively associated with both sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction, with small-to-moderate effect sizes that remain robust after controlling for sexual frequency and relationship length (Mallory, 2019; Mallory, 2022; Falgares et al., 2024). Sexual interactions in which partners can verbalise preferences, boundaries and vulnerabilities, and in which they feel safe to signal dissatisfaction or asymmetry, are more likely to be experienced as “good sex” and as confirmatory of the relationship. Conversely, relationships characterised by inhibited communication, rigid gendered roles and implicit obligations to “perform” orgasms frequently foster climates in which sex becomes a test of adequacy rather than a shared exploration.

In our conceptualisation, autoerotic partner use at the interpersonal level appears as: (a) marked asymmetry in who defines the sexual script; (b) persistent focus on one partner’s arousal and orgasm; (c) limited curiosity about the other’s experience; and (d) rapid, non-reflective disengagement after orgasm, with minimal space for aftercare or symbolic elaboration. By contrast, relationally co-constructed sexuality is characterised by flexible turn-taking, mutual initiation, explicit negotiation of pace and practices, and a capacity to tolerate and symbolise moments of non-synchrony (e.g., when one partner does not reach orgasm) without resorting to blame or self-attack.

Sociocultural level. The couple’s sexual field is further shaped by cultural narratives and technological affordances that define what counts as desirable, normal or successful sex. Contemporary dating environments—particularly app-based matching systems—encourage an objectifying, market-like stance toward partners, emphasising rapid visual scanning, perceived abundance of alternatives and gamified feedback. Cross-sectional work on dating apps suggests that perceived success on these platforms can increase intentions to commit infidelity, especially when individuals report high availability of potential partners and low investment in their current relationship (Alexopoulos et al., 2020).

From the vantage point of our continuum, such environments normalise an instrumental relationship to others’ bodies and availability, reinforcing short-term, performance-driven sexual scripts. Pornographic templates, rating logics (“likes”, matches) and swipe-based interfaces collectively foster representations of partners as replaceable objects whose primary function is to validate desirability and provide intense but brief reward. This sociocultural pressure can consolidate autoerotic, masturbatory use of the partner even in individuals who might otherwise be capable of more mutual, co-constructed eroticism. Conversely, emergent discourses that valorise emotional literacy, consent, diversity of erotic practices and mutual pleasure—when effectively incorporated into sex education and public health messaging—may facilitate movement toward the relational pole by legitimising subjectivity-recognising sexual scripts.

Neurobiological/affective level. Finally, the continuum is underpinned by interacting motivational and bonding systems. Functional neuroimaging of the human sexual response cycle has demonstrated that orgasm recruits not only canonical reward regions (ventral striatum, medial prefrontal cortex) but also areas implicated in bodily self-awareness, emotion regulation and social cognition, particularly when sexual activity occurs in the context of an affectionate bond (Georgiadis et al., 2006; Georgiadis & Kringelbach, 2012). These findings support the idea that sexual climax can serve both as a reward signal and as a bonding event, depending on how it is embedded in relational context.

The distinction between “wanting” and “liking” components of reward provides a useful organising principle. “Wanting” refers to incentive salience—dopaminergically mediated, cue-driven motivation to seek reward—whereas “liking” concerns the hedonic impact of the reward itself, linked to more localised opioid hotspots (Berridge & Kringelbach, 2015). Autoerotic, partner-as-instrument sexuality can be conceptualised as a configuration in which “wanting”-dominant processes (performance striving, novelty seeking, tension discharge) are relatively decoupled from “liking” understood as shared, affiliative pleasure, and only weakly integrated with longer-term attachment and meaning systems. By contrast, relationally co-constructed sexuality is characterised by a tighter coupling of wanting and liking with oxytocin- and opioid-mediated bonding, such that orgasm reinforces not only the pursuit of pleasure but also the maintenance of the relational bond and the sense of mutual recognition.

Together, these intrapersonal, interpersonal, sociocultural and neurobiological/affective factors can be integrated into a multi-level framework that specifies how different configurations push couples toward predominantly masturbatory partner use or toward relationally co-constructed sexuality (

Figure 2).

5.3. Predicting Couple Satisfaction and Clinical Outcomes

Mapping couples along this multi-level continuum allows for specific, testable predictions regarding sexual satisfaction, couple satisfaction and relational stability. At a descriptive level, we hypothesise that positions closer to the autoerotic partner-use pole will be associated with: (a) higher emphasis on orgasm frequency and performance metrics; (b) potentially high self-reported sexual satisfaction for the more dominant partner; but (c) lower partner-reported satisfaction, lower perceived intimacy and more ambivalence about the relationship. Positions closer to the relational co-construction pole are expected to be associated with moderate to high levels of dyadic sexual satisfaction even when orgasm is not always achieved, higher global couple satisfaction and perceived security, and greater resilience to life-cycle stressors (illness, ageing, parenting) that temporarily modify sexual functioning.

From these patterns, we derive several hypotheses:

H1 (Asymmetry hypothesis). Higher scores on sexual detachment and sexual narcissism, combined with stronger endorsement of orgasm-goal-focused scripts, will predict higher self-reported orgasm frequency but lower partner-reported sexual and relationship satisfaction, controlling for demographic variables and relationship length.

H2 (Congruence hypothesis). Dyadic congruence in position along the autoerotic–relational continuum (both partners relatively autoerotic, or both relatively relational) will be less destabilising than marked incongruence (one predominantly autoerotic, the other predominantly relational). Incongruence will predict higher conflict, more frequent perceptions of rejection or coercion and greater instability (e.g., breakup intentions, infidelity).

H3 (Mediational hypothesis). The association between intrapersonal traits (e.g., narcissism, attachment avoidance, alexithymia) and couple satisfaction will be partially mediated by the degree of autoerotic partner use versus relational co-construction in sexual interactions, as assessed by combined behavioural and self-report indicators.

Clinically, this model implies that interventions should not focus exclusively on increasing orgasm frequency or adding techniques, but on shifting the couple’s position along the continuum: enhancing mutual mentalization, fostering embodied curiosity about the partner’s experience and explicitly renegotiating scripts that currently encode the partner as instrument rather than subject.

6. Clinical, Psychoeducational and Research Implications

6.1. Assessment and Case Formulation

Translating the autoerotic–relational continuum into clinical practice requires that assessment move beyond generic “sexual satisfaction” items and explore how sexuality is mentally represented and enacted in the couple. A first level concerns standardized measures of sexual functioning and satisfaction. Grover and Shouan’s review of assessment scales for sexual disorders highlights the richness—but also the fragmentation—of available tools, ranging from global indices of sexual satisfaction to condition-specific scales for desire, arousal, orgasm and pain (Grover & Shouan, 2020). Within our framework, such instruments provide a necessary but insufficient basis: they quantify frequency, difficulty and distress, but do not directly capture partner instrumentalization, orgasm goal-focus or sexual detachment.

Clinical interviewing therefore becomes central. Althof and Parish, in their discussion of interviewing versus questionnaires in the context of sexual dysfunction among cancer patients, stress that narrative and contextual information often reveal discrepancies between reported “function” and lived experience, allowing the clinician to detect performance-driven scripts, shame and relational avoidance that remain invisible in brief scales (Althof & Parish, 2013). Within the present model, a semi-structured assessment should systematically include: (a) the degree of orgasm centrality (e.g., whether the “success” of the encounter is equated with orgasm occurrence and intensity); (b) the extent of partner subjectivization (capacity to imagine the partner’s inner world during sex); (c) the presence of detached or instrumental motives for sex (regulation of self-esteem, tension discharge, proof of desirability); and (d) perceived reciprocity and fairness in giving/receiving pleasure.

Mixed-method approaches offer promising templates. Van de Bongardt and Verbeek’s Relational and Sexual History (RSH) interview illustrates how visual and narrative tools can be used to co-construct with the patient a diachronic map of intimate relationships, linking sexual patterns to attachment experiences and learning processes (van de Bongardt & Verbeek, 2021). Such procedures are highly compatible with our continuum: clinicians can invite individuals or couples to position their current relationship—and previous ones—along the axis from “sex mainly for self-confirmation and release” to “sex as shared experience of mutual subjectivity.”

Qualitative work on sexual scripting further underlines the need to listen to how patients tell their sexual life. Mitchell and colleagues show that many adults orient their narratives around normative scripts of “proper” sexual functioning (desire–erection/lubrication–penetration–orgasm), with strong self-monitoring and anxiety when they deviate from these scripts (Mitchell et al., 2011). In orgasm-centred, masturbatory use of the partner, these scripts are often rigidly endorsed and saturated with performance language (“I must make them come”, “I have to last”), whereas in more relational patterns they are narrated with greater flexibility, humour and attention to context. From an assessment standpoint, this suggests the clinical utility of: (a) eliciting detailed accounts of a typical sexual encounter (“walk me through what usually happens, step by step”); (b) exploring inner dialogue during sex (“what do you say to yourself while it is happening?”); and (c) examining perceived mismatches between one’s own script and that of the partner.

Planned

Table 3 is designed precisely to synthesize these dimensions into a clinically usable grid, distinguishing cognitive, affective, behavioural/relational and narrative indicators of predominantly autoerotic versus predominantly co-constructed sexual functioning. This table can guide both diagnostic formulation and treatment planning, helping the clinician to identify when orgasm-centred sexuality has crystallized into a masturbatory use of the partner with likely negative implications for couple satisfaction.

6.2. Couple Therapy and Individual Psychotherapy

On the therapeutic plane, the model argues for interventions that explicitly target the shift from “doing sex to the partner” to “experiencing sex with the partner.” Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy (EFT) offers a particularly powerful framework, given its focus on attachment, emotional engagement and the restructuring of interactional cycles. Johnson and Zuccarini’s integration of sex and attachment in EFT conceptualizes sexual problems as expressions of attachment injuries, protest or withdrawal, rather than isolated “symptoms”; their proposal to work simultaneously on emotional bonding and sexual encounters resonates strongly with the movement from autoerotic discharge to relational co-construction described in this paper (Johnson & Zuccarini, 2010).

Girard and Woolley’s application of EFT to sexual desire discrepancy demonstrates how reframing sexual issues as relational and attachment-based—rather than as deficits in drive or technique—can lead to improved desire and satisfaction for both partners (Girard & Woolley, 2017). Within our continuum, this corresponds to helping couples move away from orgasm as a solitary achievement enacted through the other, towards orgasm as the embodied culmination of moments of felt safety, responsiveness and recognition. Core EFT interventions such as heightening, enactments and choreographing new emotional experiences can be complemented by explicit exploration of sexual scripts, inviting partners to mentalize not only their own emotions but also their erotic representations of self and other.

Integrative sex therapy models also offer clinically relevant tools. Schwartz and Southern’s contemporary update of the Masters and Johnson approach stresses the importance of combining behavioural exercises (e.g., sensate focus) with exploration of meaning, body image, shame and couple dynamics in desire disorders (Schwartz & Southern, 2000). In our perspective, sensate focus and other non-goal-oriented exercises become opportunities to suspend orgasm imperatives, to invite curiosity about the partner’s bodily and affective responses, and to confront anxieties around dependence and loss of control that often underpin masturbatory partner use.

A further layer involves working with patients whose personality organization is markedly narcissistic. Here the therapist may need to address defensive contempt towards vulnerability, chronic fear of being used or humiliated, and the tendency to equate relational value with sexual performance. Treatment tasks include fostering the capacity to recognize the partner as a separate subject with an independent erotic life, tolerating experiences of “not being the centre” of the sexual scene, and integrating sexual excitement with tenderness and concern. Such work can be carried out in individual psychodynamic psychotherapy as well as in couple formats, where the mutual enactment of autoerotic scripts becomes an explicit focus of interpretation and restructuring.

6.3. Psychoeducation, Prevention and Digital Culture

Beyond clinical settings, the model has implications for sexual education and prevention. Recent sexological proposals argue for a biopsychosocial, sex-positive framework that explicitly values pleasure, diversity and relational meaning rather than centring solely on pathology or risk (Brotto & Luria, 2014). In this perspective, our continuum can be presented to adolescents and young adults as a reflective tool, helping them to distinguish between encounters that are mainly self-regulatory, performance-driven and disconnected, and experiences in which erotic pleasure is intertwined with mutual recognition, consent and care.

Network-analytic work on positive sexuality shows that indicators such as sexual pleasure, sexual communication and positive sexual self-concept form a tightly interconnected cluster, with specific links to relationship satisfaction and well-being (e.g., Štulhofer et al., 2019). These findings support psychoeducational programmes that prioritize not only knowledge about contraception and consent, but also skills in communicating desires, negotiating scripts and attending to the partner’s experience. In our terms, they point towards interventions that strengthen the “relational” pole of the continuum—without pathologizing solitary or non-relational sexual practices, but inviting critical reflection when orgasm becomes the sole metric of success and the partner is reduced to an instrument.

Crowe’s therapeutic guidelines on couple relationship problems and sexual dysfunction underscore how often sexual and relational difficulties are intertwined, with sexual dysfunctions both reflecting and exacerbating dissatisfaction, power struggles and communication failures (Crowe, 2017). Translating this insight into digital-era prevention suggests at least three priorities.

First, media literacy about pornographic and dating-app scripts. Young people can be helped to recognize how repetitive exposure to orgasm-focused, performance-based sexual scenes—often detached from tenderness, negotiation or aftercare—may shape expectations and self-evaluations, making masturbatory partner use seem “normal” or even desirable.

Second, relational script work in educational contexts. Rather than limiting curricula to “what not to do” (avoid pregnancy, avoid infections, avoid coercion), programmes can include guided discussions of what it means to co-create a sexual encounter, to remain emotionally present, and to integrate one’s own pleasure with responsiveness to the other. Exercises can invite students to imagine “a good sexual memory” from both partners’ perspectives, making subjectivity and reciprocity salient.

Third, early identification of risk markers. As outlined in

Table 3, cognitive, affective, behavioural and narrative indicators of predominantly autoerotic functioning (e.g., exclusive focus on orgasm and technique; affective neutrality or irritability when sexual goals are not met; avoidance of eye contact or tender gestures; narratives emphasizing conquest, control or “discharge”) can be contrasted with indicators of predominantly relational functioning (e.g., curiosity about the partner’s pleasure; comfort with non-orgasmic intimacy; behavioural flexibility; narratives of shared discovery). Such a grid may be used in counselling services, university clinics and online interventions to identify individuals and couples at higher risk of chronic relational dissatisfaction, coercive dynamics or intimate partner violence.

For clinical and psychoeducational purposes, these indicators can be organised into a concise grid that contrasts predominantly autoerotic/partner-instrumental patterns with predominantly relational/co-constructed patterns. This framework is summarised in

Table 3.

7. Future Directions and Conclusion

7.1. Methodological and Conceptual Challenges

The model proposed in this paper intentionally goes beyond the predominant empirical paradigm in research on sexuality and couple satisfaction, which has relied largely on cross-sectional, mono-informant designs and global self-report indices. A dynamic understanding of movement along the autoerotic–relational continuum requires intensive, time-sensitive and dyadic approaches. Diary and other intensive longitudinal methods are particularly well suited to capture micro-fluctuations in orgasmic experience, sexual detachment and perceived partner subjectivity in everyday life and across developmental phases of the relationship (Bolger et al., 2003). These designs would allow the examination of within-person and within-dyad variability as couples navigate stressors, life-cycle transitions and changing sexual scripts.

Analytically, dyadic frameworks such as the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) are indispensable for estimating how one partner’s position on the continuum affects both their own outcomes (actor effects) and those of the partner (partner effects) (Kenny et al., 2006). Longitudinal APIM studies already demonstrate that sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction are distinct yet intertwined constructs, with sexual satisfaction often predicting later relationship satisfaction more strongly than the reverse (Fallis et al., 2016; Vowels & Mark, 2020). The present model invites a further step: using latent profiles or structural models that combine indicators of sexual detachment, sexual narcissism, partner objectification and orgasm goal-focus to operationalize “partner-as-masturbatory-object” configurations and to test their incremental predictive value over and above global sexual satisfaction.

From a measurement standpoint, “partner as masturbatory object” cannot be reduced to a single scale. It is better conceptualized as a latent phenotype emerging from the co-occurrence of specific dispositions (e.g., narcissistic traits), sexual cognitions (e.g., orgasm imperative, instrumental motives), and behavioural patterns (e.g., low communication, high performance pressure, asymmetrical orgasm concern). Multimethod strategies – integrating standardized self-report instruments (as summarized in

Table 2), behavioural observations of couple interaction, and qualitative or narrative data – are therefore essential. Mixed-methods designs, in which qualitative interviews about orgasmic scripts and lived sexual experience are explicitly integrated with quantitative indicators, are particularly appropriate to capture the subtle ways in which the partner’s subjectivity is erased or recognized within sexual encounters.

A further challenge concerns the pervasive gender-, hetero- and couple-normativity of the current evidence base. Many dyadic and longitudinal studies still focus on cisgender, different-sex, cohabiting couples, limiting generalizability. Existing APIM work already suggests that the direction and strength of associations between sexual and relationship satisfaction can vary across gender and cultural context (Fallis et al., 2016; Vowels & Mark, 2020). Testing the autoerotic–relational model therefore requires samples diverse in gender identity, sexual orientation, relationship structure and cultural background, together with measurement-invariance analyses to ensure that constructs such as sexual detachment or partner objectification are comparable across groups.

Finally, sociocultural and digital-context variables must be treated as central, not peripheral. Pornographic scripts, dating-app practices and social media norms of performance constitute powerful environmental pressures toward orgasm-focused, instrumental sexuality. Meta-analytic evidence indicates that pornography consumption is, on average, associated with lower interpersonal satisfaction (sexual and relational), particularly among men (Wright et al., 2017), while more recent work reveals curvilinear patterns in which higher-frequency use is linked to more negative relational outcomes (Willoughby et al., 2021). Embedding such variables in longitudinal, dyadic designs will be crucial to determine under which intrapsychic and relational conditions these sociocultural forces push couples toward the autoerotic, partner-as-instrument pole, and when they can be buffered or transformed.

7.2. Key Research Questions