Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Police Officers’ Responses to Stress

2.1.1. Stimulus-Based Approach

2.1.2. Response-Based Approach

2.1.3. Interaction-Based Approach

2.2. Secondary Traumatic Stress on Police Officers

2.3. Aggressive Behavior-Related Neural Mechanisms

2.3.1. Proactive Aggressive Behavior

2.3.2. Reactive Aggressive Behavior

2.3.3. Neurological Distinctions between Aggression Types

2.3.4. Psychological and Neurological Features of Reactive Aggression

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. Semi-structured Interview Design and Procedure

3.1.1. Conceptual Framework

- Sources of stress: Psychological reactions and secondary traumatic stress

- 2.

- Physical and mental health risks

- 3.

- Aggressive behavior and neural mechanisms

3.1.2. Data Analysis Method: Thematic Analysis

- Familiarization with the data: The research team repeatedly read the interview transcripts to understand the context and meanings conveyed by the participants.

- Generating initial codes: Open coding was conducted based on the interview content, marking recurring phrases and key semantic elements.

- Searching for initial themes: Similar codes were grouped into thematic categories to develop an initial thematic structure.

- Reviewing themes: The relationship between themes and the original data was cross-checked to ensure consistency; duplicate themes were merged or refined.

- Defining and naming themes: Core concepts and boundaries of each theme were clarified and appropriately named to reflect their essence.

- Producing the report: The results were synthesized; representative quotes are included for interpretive analysis and discussion.

3.1.3. Research Tools

- What are the common practical difficulties and challenges police officers face when handling cases?

- What are the primary sources of stress experienced during emergency responses or routine duties?

- What behavioral responses commonly occur when emotional regulation fails?

- What mechanisms or support strategies does the organization adopt to handle or prevent violence-related incidents involving officers?

- How do officers typically relieve stress in their daily duties? What are common coping methods?

- What are the attitudes and actual practices of supervisors and organizational culture regarding “emotional regulation and stress coping among police officers”?

- What are the specific observations and recommendations regarding inter-agency coordination, personnel training, staffing, and legal frameworks related to stress management and emotional regulation for police officers?

3.1.4. Strategies for Ensuring Trustworthiness

- Triangulation: Cross-verification using data from participants with diverse service years, genders, and ranks, as well as through collaboration among multiple researchers, enhances data richness and consistency.

- Peer review: Regular discussions among team members were conducted to verify the logic of coding and theme development.

- Reflexivity: The lead researcher maintained reflective journals to assess the potential impact of personal roles, values, and interpretive positions on data comprehension.

- Member checking: Portions of the interview transcripts were reviewed and confirmed by participants to ensure that the narratives accurately reflected their original intentions, thereby enhancing data accuracy and representativeness.

3.1.5. Research Limitations

- Limited sample size: Only seven participants were interviewed, which restricts the generalizability of the findings and makes it challenging to represent the full spectrum of experiences among police personnel.

- Geographically concentrated sample: Participants were recruited from police departments in specific counties/cities. Regional factors may have influenced the participants’ experiences, limiting the ability to account for nationwide institutional variations.

- Risk of subjective interpretation: Qualitative analysis involves the researcher’s interpretation. Although triangulation and peer review were employed to enhance analytical validity, interpretations may still be influenced by the researcher’s positionality and cognitive biases.

- Lack of longitudinal data: The study was based on a single round of interviews and did not track the dynamic changes in stress responses or coping mechanisms over time.

4. Research Findings and Discussion

4.1. Research Results and Analysis

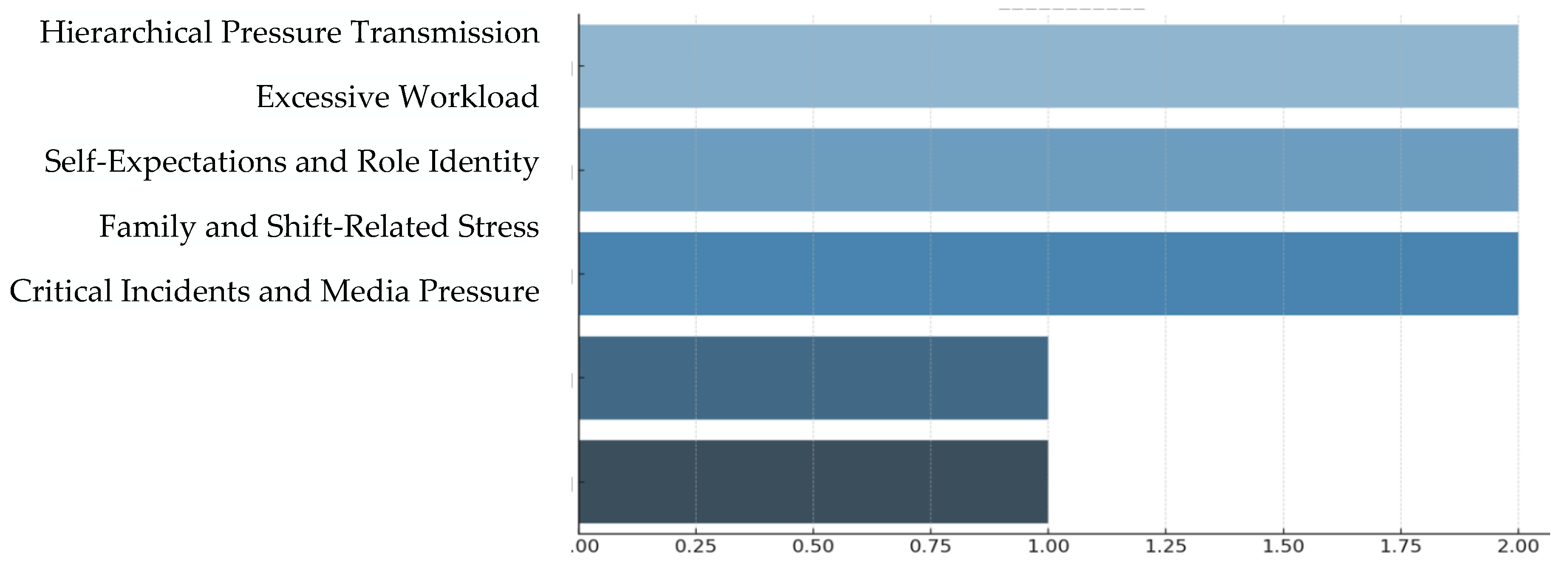

4.1.1. Facing Stress Challenges

- Stress faced on duty

| Interviewee ID | Summary from a stress perspective | Verbatim quote |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Stress exhibits a clear pattern of “hierarchical transmission,” flowing downward from senior officials and elected representatives, with frontline officers bearing the ultimate burden. | “If the station chief is under pressure, then we’re all under pressure ... Once the precinct head feels pressure from a legislator, the command passes down layer-by-layer until the frontline officer takes it all.” |

| 02 | Participant feels that stress is concentrated at the “supervisory level,” acting as both the origin and turning point of pressure within the unit. | “Under the current circumstances, all the pressure is on the supervisors.” |

| 03 | Participant identifies “self-expectations and level of personal involvement” as key sources of stress—detachment reduces perceived stress. | “If you’re committed to serving the public wholeheartedly, you’ll feel the pressure. But if you’re indifferent, then honestly, you won’t feel any pressure at all.” |

| 04 | Participant considers “self-identity and role perception” as central to how stress is experienced. | “I think the pressure depends on what type of police officer you want to be.” |

| 05 | Participant cites “excessive workload and multitasking” as major stressors in daily duties. | “There are always so many incident reports, official documents, and assignments to handle. Sometimes I even prepare presentations—I’m just overwhelmed and physically exhausted.” (Simulated supplement) |

| 06 | Participant indicates a “lack of flexible shifts and family support” as contributors to accumulating stress, particularly under a rotating shift system. (Inferred case expansion) | “Sometimes I work the graveyard shift and still have to rush to court or write reports after. My family doesn’t really understand, and over time, I start to wonder if I can keep going.” |

| 07 | Participant emphasizes pressure peaks during “major emergencies,” and the aftermath, including media scrutiny, creates a sustained psychological burden. (Derived from organizational stress hierarchy) | “When a major case occurs, the entire unit is on edge. Then, the media calls to ask for updates. Often the real stress doesn’t come from solving the case, but from facing the public eye.” |

- Discrepancy between public expectations and reality

- Public interaction pressure

- 2.

- Role of CCTV in police investigations and the pressure on police officers

| Thematic Category | Subcategory | Interview Data Reference | Thematic Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Heavy Dependence on CCTV | Case reconstruction and suspect identification rely on video footage. | Police officer 01; 02 | CCTV serves as the core of the evidentiary chain and is one of the most critical tools in the early stages of an investigation. |

| 2. Inadequate System Coverage | CCTV blind spots or a lack of footage lead to investigative dead ends. | Police officer 03 | When no footage is available and there are no witnesses or physical evidence, the investigation stalls, increasing the risk of misjudgment. |

| 3. Delay in Reporting Affects Access | Late reporting results in footage overwritten automatically. | Police officer 04; 05 | Victims often delay reporting, causing critical footage to be lost due to system overwriting, resulting in disrupted evidence chains. |

| 4. Time-Consuming Retrieval Process | Complex procedures and fragmented footage across zones. | When a case involves multiple locations, officers spend extensive time cross-referencing clips, increasing the investigative workload. | |

| 5. Lack of Public Awareness | Victims underestimate the time sensitivity of video data. | Police officer 07 | Citizens often overlook the retention limits of surveillance systems, failing to preserve footage critical for successful case resolution. |

- 3.

- Stress management patterns

- Stress control and emotional dysregulation behaviors

| Thematic Category | Subcategory | Interview Insights | Thematic Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internalization and Personality Traits | Reserved personality, self-suppression, poor communication. | Police officer 02; 03 | Officers who struggle with expression or adjustment tend to accumulate stress internally, which may result in behavioral outbursts when triggered. |

| 2. Externalized Conflict Behaviors | Throwing objects, issuing tickets aggressively, and direct confrontation with citizens. | Police officer 01; 02; 03 | Officers with low emotional regulation tend to release stress and anger through verbal or physical aggression. |

| 3. Retaliatory Workplace Behaviors | Sabotaging superiors, setting up situations to cause blame. | Police officer 04 | When emotions cannot be voiced upward, they may manifest as passive-aggressive or retaliatory behavior, reflecting a breakdown in communication and trust within the organization. |

| 4. Anonymous Online Venting | Posts in anonymous forums, such as anti-police pages. | Police officer 06; 07 | Officers reported turning to anonymous platforms to express dissatisfaction when internal communication channels are ineffective. |

| 5. Emotionally Repressive Organizational Culture | Pressure to “silently endure” and a lack of formal complaint mechanisms. | Police officer 06 | Many respondents noted that the organizational culture discourages emotional expression and lacks sufficient psychological support or communication feedback systems. |

- Clear privacy policies

- Anonymous participation mechanisms

- Secure data handling

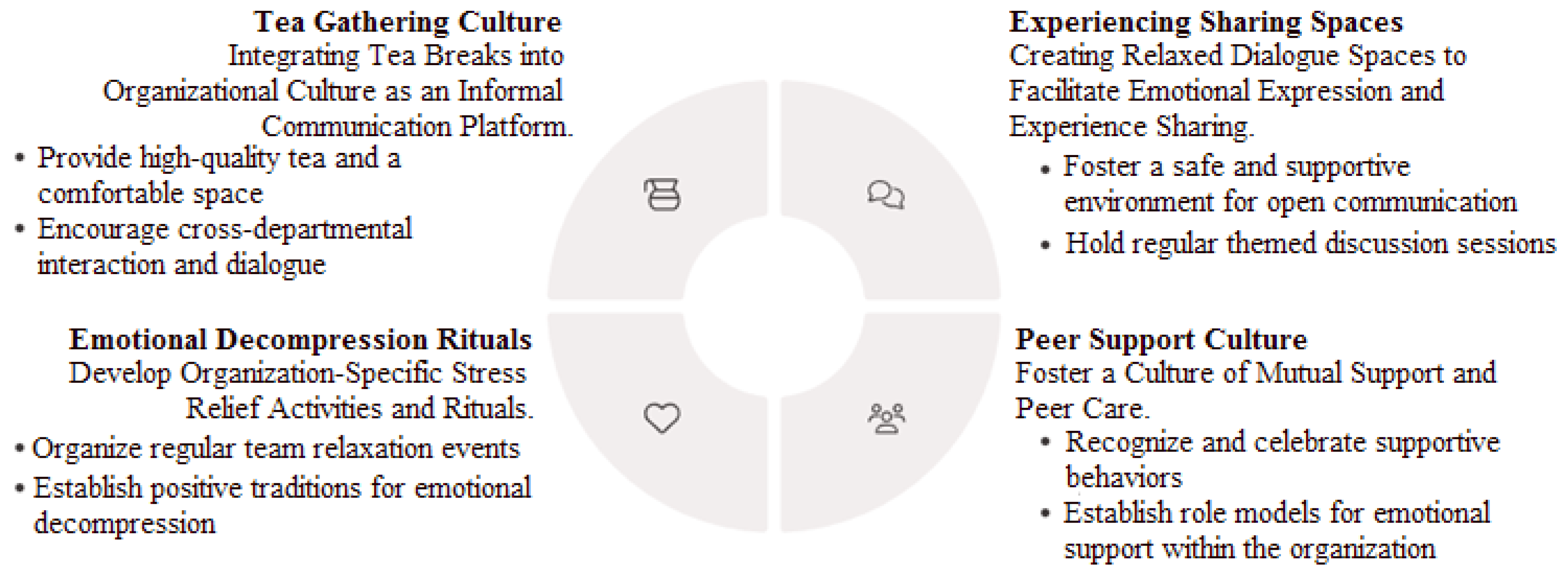

- Coping strategies employed by police officers

| Thematic Category | Subcategory | Interview Insights | Thematic Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Support | 1.1 Peer reassurance and guidance 1.2 Emotional support from family and friends 1.3 Duty adjustment by supervisors |

Police officer 01; 02; 03 | Peer support provides a crucial outlet for emotion; family and friends provide everyday emotional sharing; supervisory adjustment of duties is an effective stress relief strategy. |

| 2. Professional Support | 2.1 Distrust in internal counseling and fear of stigmatization 2.2 Need for contextualized psychological training |

Police officer 01; 04; 05; 06 | Although most officers acknowledged the need for psychological support systems, concerns about stigma, career impact, and the relevance of training content to real-life police duties were prevalent. |

| 3. Individual Coping | 3.1 Emotional intelligence and self-guided regulation 3.2 Relaxation methods such as exercise or tea breaks 3.3 Practical skills development and mindset shift 3.4 Experience-sharing and cultural adaptation |

Police officer 03; 05; 07 | Emotional intelligence and self-regulation are viewed as key coping mechanisms. Cultural practices such as tea gatherings and mentorship from experienced officers help younger officers adapt and grow. |

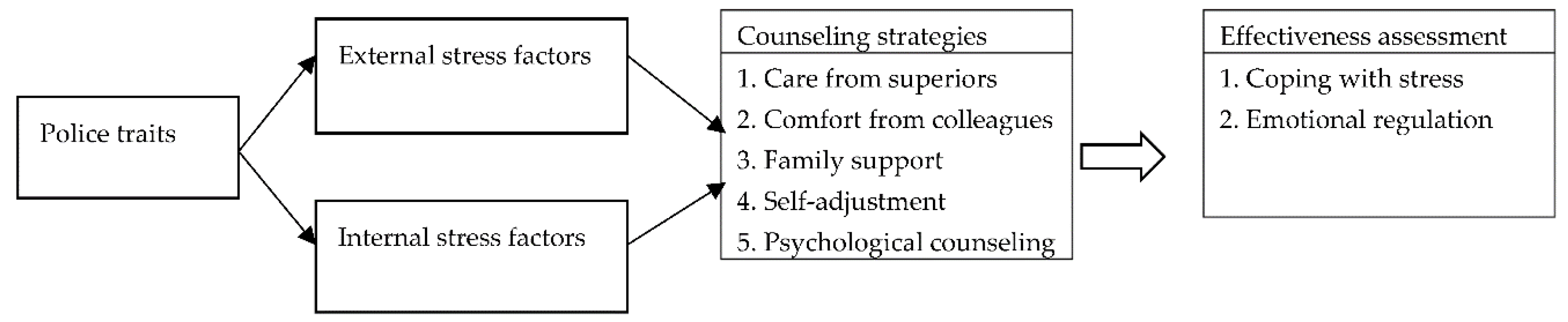

5. Conclusion and Suggestions

5.1. Research Conclusion

- Screening mechanism for new recruits: We recommend the incorporating the assessments of emotional regulation abilities into the recruitment process to identify individuals prone to emotional dysregulation early while offering adequate psychological counseling and training resources.

- Intervention for officers exhibiting aggressive behavior: For officers who have exhibited violent or emotionally dysregulated behavior during duty, we recommend the use of EEG testing and psychological evaluations to implement follow-up counseling and behavioral adjustment training.

- Monitoring and preventive measures for general officers: To understand the mental and emotional states of general officers, institutions should periodically conduct stress sampling and psychological stability assessments. This allows for timely support measures to strengthen resilience and workplace adaptability.

5.2. Research Suggestions

5.2.1. Enhancing Officer Selection and Impulse Control Prevention Mechanisms

- Application Model Aligned with the Research Hypotheses

- 2.

- Strategies for Preventing Impulsive and Aggressive Behavior

5.2.2. Establishing a Stress Reduction and Psychological Support System for Officers

- Institutional Care Mechanism

- 2.

- Tiered Psychological Support Services

- 3.

- Strengthening Supervisors’ Proactive Support Role

- 4.

- Improving Leave Policies and Stress-Relief Facilities

| Policy Dimension | Specific Recommendation | Application Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Screening and Prevention Mechanisms | Introduce behavioral and physiological screening tools for emotional and impulse control. | Conduct timely assessments during the recruitment phase to identify candidates with higher emotional risk. |

| 2 | Preventing Impulsive and Aggressive Behavior | Develop training programs on emotional regulation and aggression inhibition for officers. | Incorporate pre-service education and training to enhance self-regulation under provocation. |

| 3 | Organizational Psychological Support System | Establish a Mental Health Task Force led by senior management. | Facilitate cross-departmental collaboration to implement mental health promotion and crisis response. |

| 4 | Tiered Psychological Care Services | Offer a range of services: physical and mental screenings, supervisor care, and individual/group support. | Tailor the intensity of services based on officers’ stress risk level to enhance effectiveness and relevance. |

| 5 | Leadership Support and On-Site Care | Supervisors should conduct regular visits and respond to officers’ emotional and physical needs. | Demonstrates organizational care and backup, reducing burnout and turnover risks. |

| 6 | Leave Policy and Facility Enhancement | Improve access to fitness facilities and design flexible leave policies. | Provide stress relief resources to help officers maintain mental-physical balance and duty stability. |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ELS | Early life stress |

| PFC | Prefrontal cortex |

| OFC | orbitofrontal cortex |

| CCTV | closed-circuit television |

| EQ | emotional quotient |

References

- Juang, Y.S.; Lo, S.C. Impact of leadership styles and working stress on job satisfaction - a case study of police divisions in Hsinchu county. Ling Tung J 2020, 46, 85–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.C.; Wu, T.C.; Huang, C.Y. Research on the relationship between police work stress and leisure involvement, health status and quality of life - take Madou police precinct of Tainan City as example. J Sport Health Leis 2018, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, S.C.; Chou, C.W. The Study on job burnout, personal accomplishment and job satisfaction of police officers during the period of Covid-19. J Police Manag 2022, 18, 217–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.S.; Hong, Y.H. A Research on work-family conflict of criminal investigation police officers. J Police Manag 2017, 13, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.H.; Chen, C.C. Policeman stressors and coping strategies. J Police Manag 2015, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; Tan, H.; Kang, L.; Yao, L.; Huang, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Hu, S. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Q.-H.; Wang, C.-M.; Wang, J. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res 2020, 288, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Du, H.; Li, R.; Kang, L.; Su, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, B. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.W.; Lee, G.K.; Tan, B.Y.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Ngiam, N.J.; Yeo, L.L.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A.; Napolean Shanmugam, G.; Sharma, A.K.; Komalkumar, R.N.; Meenakshi, P.V.; Shah, K.; Patel, B.; Chan, B.P.L.; Sunny, S.; Chandra, B.; Ong, J.J.Y.; Paliwal, P.R.; Wong, L.Y.H.; Sagayanathan, R.; Chen, J.T.; Ying Ng, A.Y.; Teoh, H.L.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C.; Sharma, V.K. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.L. My Pet Stress Monster: An Illustrated Commentary. Master’s thesis, Department of Visual Communication Design, Ming Chi University of Technology, New Taipei City, 2019.

- Greenberg, M.A.; Wortman, C.B.; Stone, A.A. Emotional expression and physical health: Revising traumatic memories or fostering self-regulation? J Pers Soc Psychol 1996, 71, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Croft, J.B.; Felitti, V.J.; Nordenberg, D.; Giles, W.H.; Williamson, D.F.; Giovino, G.A. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA 1999, 282, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Walker, J.; Whitfield, C.; Bremner, J.D.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health, well-being, social function, and health care. In The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic, Lanius, R., Vermetten, E., Pain C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K, 2007; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D.P.; Whitfield, C.L.; Felitti, V.J.; Dube, S.R.; Edwards, V.J.; Anda, R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord 2004, 82, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrona, C.E.; Wallace, G.; Wesner, K.A. Neighborhood characteristics and depression: An examination of stress processes. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2006, 15, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Dube, S.R.; Williamson, D.F.; Thompson, T.J.; Loo, C.M.; Giles, W.H. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl 2004, 28, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, V.J.; Holden, G.W.; Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am J Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkola, S.; Isometsä, E.; Aro, H.; Kestilä, L.; Hamalainen, J.; Veijola, J.; Kiviruusu, O.; Lönnqvist, J. Childhood adversities as risk factors for adult mental disorders: Results from the Health 2000 Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005, 40, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Williamson, D.F.; Giles, W.H. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA 2001, 286, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anda, R.F.; Butchart, A.; Felitti, V.J.; Brown, D.W. Building a Framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experience. Am J Prev Med 2010, 39, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.W.; Anda, R.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Felitti, V.J.; Edwards, V.J.; Croft, J.B.; Giles, W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med 2009, 37, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancevich, T.M.; Matteson, M.T. Stress and Work: A Managerial Perspective, Scott, Foresman & Cony: Glenview. IL, U.S.A., 1980.

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping, Springer: New York, U.S.A., 1984.

- Compas, B.E.; Connor-Smith, J.K.; Saltzman, H.; Thomsen, A.H.; Wadsworth, M.E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull 2001, 127, 87–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vîrgă, D.M.; Baciu, E.-L.; Lazăr, T.-A.; Lupșa, D. Psychological capital protects social workers from burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secosan, I.; Bredicean, C.; Crainiceanu, Z.P.; Virga, D.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Bratu, T. Mental health in emergency medical clinicians: burnout, STS, sleep disorders. A cross-sectional descriptive multicentric study. Central Eur Ann Clin Res 2019, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E. Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc Work 2007, 52, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L.; Emanuel, F.; Zito, M. Secondary traumatic stress: Relationship with symptoms, exhaustion, and emotions among cemetery workers. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout of North Korean refugees service providers. Psychiatry Investig 2017, 14, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollf, H.G. Stress and Disease, Charles C. Thomas., Ed.; Charles C. Thomas, Publisher: Springfield, IL., U.S.A, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. Studies of ulcerative colitis. III. The nature of the psychologic processes. Am J Med 1955, 19, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshan, L. An emotional life-history pattern associated with neoplastic disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1966, 125, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Rosenman, R.H. Type A behavior and your heart. Knopf: New York, U.S.A., 1974.

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.E.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlund, K.; Kristiansson, M. Aggression and the brain: The role of the frontal lobes. Int J Law Psychiatry 2009, 32, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, G.; Strüber, D. Neurobiological aspects of reactive and proactive violence in antisocial individuals. Praxis der Rechtspsychologie 2008, 58, 587–600. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, S.L.; Blair, R.J.R. The development of antisocial behavior: What can we learn from functional neuroimaging studies? Dev Psychopathol 2008, 20, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.J.; Trainor, B.C. Neural mechanisms of aggression. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007, 8, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.J.R.; Peschardt, K.S.; Budhani, S.; Mitchell, D.G.V.; Pine, D.S. The development of psychopathy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006, 47, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, A.; Victoroff, J. Understanding human aggression: New insights from neuroscience. Int J Law Psychiatry 2009, 32, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, J.A.; Smithmyer, C.M.; Ramsden, S.R.; Parker, E.H.; Flanagan, K.D.; Dearing, K.F.; Relyea, N.; Simons, R.F. Observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children’s anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child Dev 2002, 73, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Houston, R.J. The utility of forms and functions of aggression in emerging adulthood: Association with personality disorder symptomatology. J Youth Adolesc 2008, 37, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Sansone, L.A. Borderline personality and externalized aggression. Innov Clin Neurosci 2009, 6, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mancke, F.; Herpertz, S.C.; Bertsch, K. Aggression in borderline personality disorder: A multidimensional model. Personal Disord 2015, 6, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).