1. Introduction

Sphingomonas paucimobilis is a Gram-negative bacillus, strictly aerobic, non-fermentative, with catalase and oxidase activity, ubiquitously distributed and have been reported to be common inhabitant of water and soil [

1]. Virulence factors associated with the bacterium include: presence of pili, phospholipase C, protease, and a flagellum [

2]. The organism lacks the lipopolysaccharides (endotoxin), important outer membrane components of Gram-negative bacteria.

Sphingomonas spp. are bacteria that replace lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with glycosphingolipids (GSL), and can grow in a wide range of environments that are hostile to most other bacteria [

3]. The lack of endotoxin activity may explain the reduced virulence and the favourable prognosis in infections that do occur [

4].

S. paucimobilis is an heterro- and oligotrophic bacterium that can survive in low-nutrient environments and has the ability to form biofilm in water pipes, thus causing bioaccumulation and spreading in drinking water systems [

5]. The bacterium has also been isolated from hospital settings, such as hospital water systems, dialysis fluid, nebulizers, and equipment for mechanical ventilation [

6]. It is believed to be an opportunistic pathogen that has rarely been reported to cause clinical disease in humans and animals [

7]. In humans, it has been associated with cases of bacteraemia, catheter-related sepsis, diarrhoea, peritonitis, meningitis, skin diseases, lung empyema, and pneumonia, oral and visceral infections, endophthalmitis, urinary tract infections, etc. Due to the low virulence of

Sphingomonas spp., the mortality rate from this pathogen is very low [

8].

S. paucimobilis has been identified as a pathogen in animals, causing mastitis in dairy cows, chronic lung infections in goats and cows, joint infections in cows, septicaemia in ruminants, and polyarthritis in dogs [

3,

9,

10,

11].

2. Case History

Feed and Water

All cattle in the feedlot were fed a balanced total mixed ration (TMR) that included grain, corn silage, soybean meal, mineral salts, and straw, which was delivered once per day. In addition, large bales of coarse thorny hay (containing significant amount of foxtail and thistle plants) were available ad libitum. They had free access to water, with each pair of pens sharing a common trough that held approximately 200 litres.

Case Description

In early January 2024, a case of abnormal behaviour was identified in a group of seven bulls before slaughter. The entire batch of the oldest fattened calves consists of a total of fourteen animals, divided into two pens. The average age of the group was seventeen months, and their body weights varied heterogeneously, ranging from 450 to 530 kilograms. The smallest bull exhibited symptoms including drooling, tongue rolling, and a noticeable decrease in body weight relative to the rest of the group. However, no abnormalities in food and water intake were observed.

Physical Examination

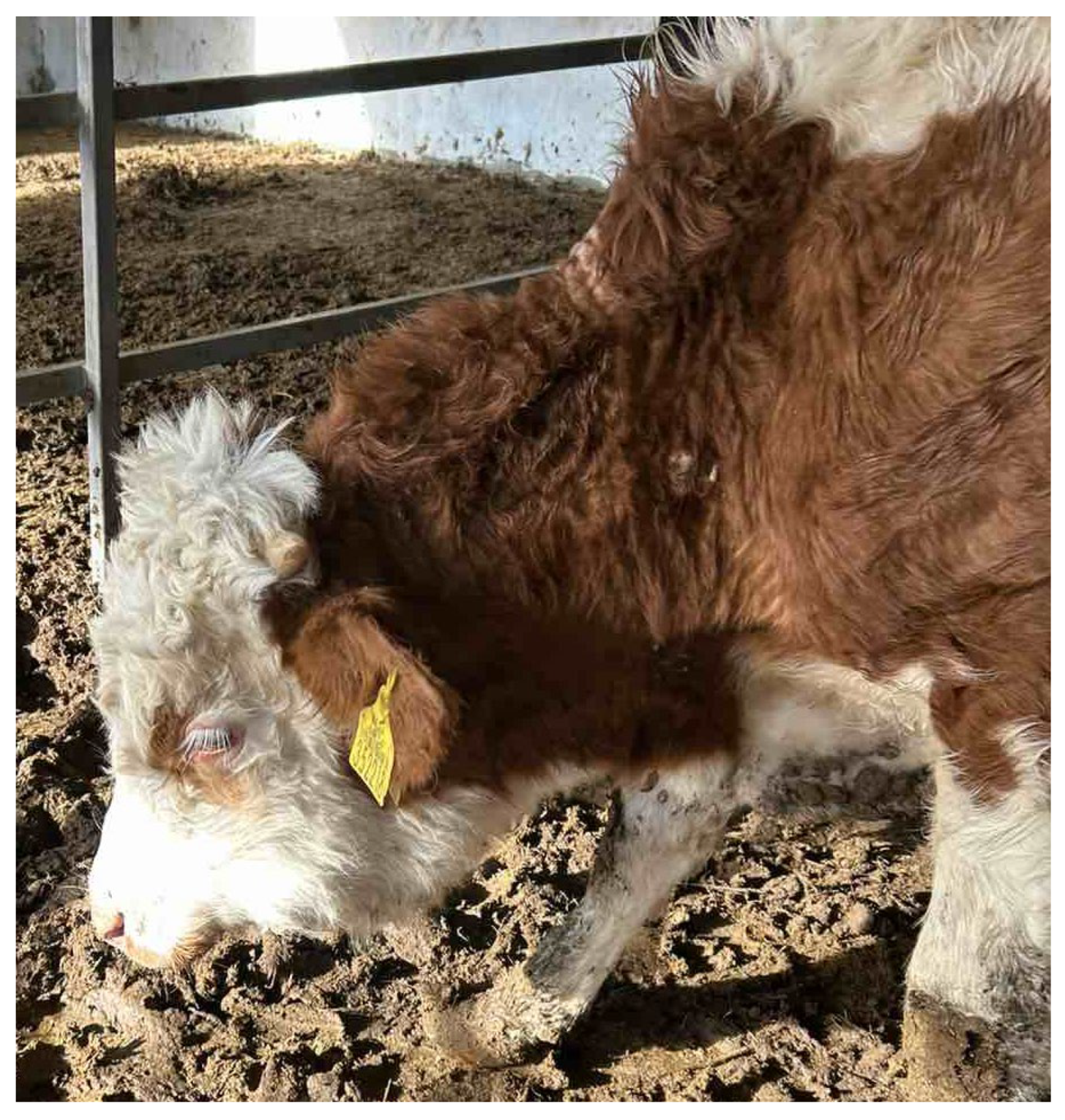

Three weeks later, a local oedema appeared in the pharyngeal region. The bull's attitude indicated that its head was bent, and the hair coat was coarse and dry, accompanied by a slight increase in the skin tent test (

Figure 1). The affected bull experienced difficulties while swallowing, both when drinking and eating. There were observations of reduced rumination and slight tympani. The body temperature was measured at a normal 38.2°C, with the pulse recorded at 78 beats per minute and the respiratory rate at 32 breaths per minute. Upon clinical examination of the oral cavity, a 3.5 cm non-bleeding, necrotising ulcerative lesion was identified on the dorsal surface of the tongue. Furthermore, the regional submandibular lymph nodes were swollen and tender upon palpation. The bull was treated solely with menbuton (Neobuton®, FM Pharm, Subotica, Serbia) at a dosage of 7.5 mg/kg, administered via intramuscular injection, along with a drench of mineral oil. Antibiotics were not utilized due to the imminent slaughter of the entire cattle batch. No disease-suspicious symptoms were observed in the other cattle, so they were not subjected to a physical examination.

3. Diagnostic Methods, and Laboratory Findings

At the time of slaughter, necrotic ulcers were found on the lateral and dorsal surfaces of the tongue. The bigger, deeper, and pus-containing lesion was located on the lateral surface, while the dorsal lesions were much smaller. The borders of the ulcers were raised and uneven, covered by slough (

Figure 2). During a routine inspection of the carcass, the official veterinarian found swollen submandibular and deep cervical lymph nodes. Out of the fourteen bulls in the batch, lesions were identified in thirteen (92.8%), while only one bull exhibited no lesions. The other individuals affected exhibited fewer and smaller lesions, primarily located on the lateral side of the tongue. During the inspection of the oral cavity, there is no severe thickening, swelling, or hardening of the tongue, nor is there any formation of abscesses detected. Additionally, no further macro-morphological changes are observed during the post-mortem inspection of the thoracic and abdominal cavity.

To determine the possible etiological cause, samples from two bulls (with the most severe changes) were collected, frozen, and sent to the microbiology laboratory of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at Trakia University in Stara Zagora, Bulgaria. The tongues with lesions from the remaining animals were subjected to destruction.

Microbiological testing: Bacteriological examination of tongue specimens from two bulls were performed. Samples from lesions were obtained as aseptically as possible and cultured aerobically in liquid broth media (Soyabean Casein Digest Medium, HiMedia™), as well as on solid nutrient media (Blood Agar Base, supplemented with 5% defibrinated ovine blood and Mac-Conkey agar, HiMedia™). Samples were incubated at 37◦C for 5 days [

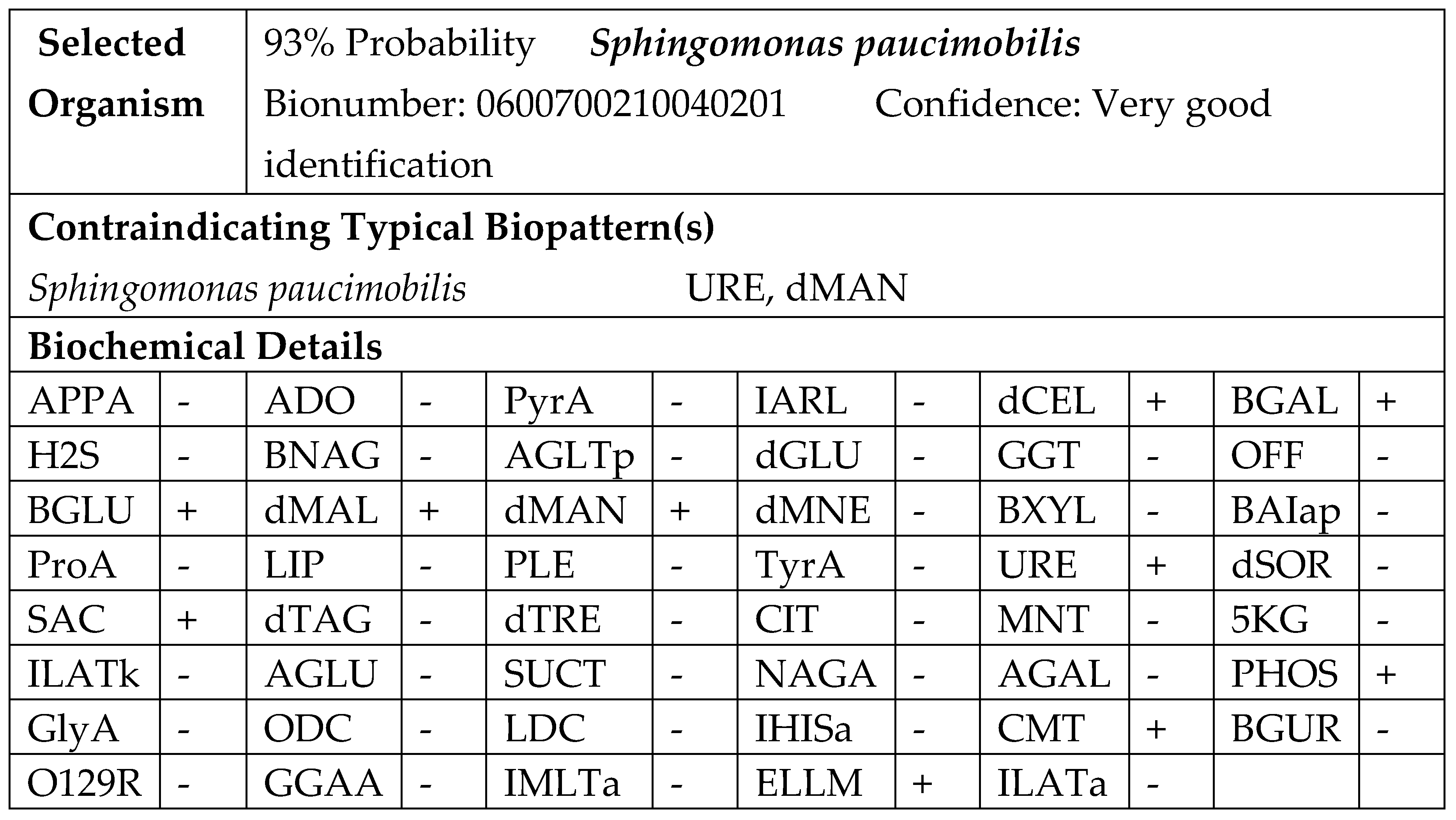

12]. The results of the cultivation showed that the bacterium is slow-growing; after 24 hours of aerobic incubation at 37 °C on blood agar, small, round, smooth, almost white, non-haemolytic colonies were visible. After 48 hours, these colonies turned yellow. No visible colonies were observed on MacConkey agar after 48 h of incubation. The organism was catalase-positive and oxidase-positive. It was identified as an aerobe with no fermentative capabilities. It grew slowly in broth media, producing weak turbidity. The cellular morphology observed in the Gram-stained microscopic preparations revealed medium-long Gram-negative rods. The isolate was subjected to phenotypic testing using the automated Vitek 2 system and software (bioMérieux). The identification was done on the colonies obtained from blood agar with 5% sheep blood after 24 h of incubation. The suspension was prepared in 3 ml of sterile saline (0.45% NaCl). A turbidity of 0.50–0.63 McFarland was measured with a Vitek 2 DensiCHEK, and a GN ID card was used for the automatic identification. The analysis time for the identification results was completed within approximately 6 hours (

Figure 3).

The laboratory analysis revealed that the lesions were caused by an

S. paucimobilis infection. Susceptibility testing of the isolate to antimicrobials was performed using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion technique on Mueller-Hinton medium (HiMedia®, India). Due to the absence of established standards for susceptibility testing of S. paucimobilis, the zone diameter interpretive standards that were used for glucose-nonfermenting bacilli, specifically

Acinetobacter spp., were applied in accordance with CLSI criteria [

1]. The isolates were found to be sensitive to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, gentamicin, cefquinome, enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin, tulathromycin, trimethoprim-sulphonamides and oxytetracycline. The strain demonstrated intermediate sensitivity to chloramphenicol and colistin. However, it was resistant to penicillin, cephalexin, and cephapirin.

After establishing the etiological role of S. paucimobilis, several control and prevention measures were implemented, including cleaning and disinfecting the water troughs and chlorinating the water source. Traumatic injuries were minimised by removing sharp edges, coarse hay was discontinued, and mineral lick blocks were provided to support overall health.

Following the introduction of these measures, no similar ulcerative-necrotic lesions were observed in subsequent batches of bulls.

4. Discussion

In animals,

Sphingomonas paucimobilis is reported as a bacterial agent responsible for sporadic infections, including mastitis, arthritis, pneumonia, and septicaemia. Due to its opportunistic nature, these conditions are often attributed to factors that can influence overall resistance [

9,

10]. In this case, the bacterium is isolated from tongue samples of only two slaughtered bulls. While other affected bulls exhibit similar ulcers in the same parts of the tongue, it is speculative to assert that the same agent causes them.

S. paucimobilis is ubiquitously distributed and often isolated from soil and water samples. Its nutritional facility allows it to survive in nutrient-poor substrates. In addition, the bacterium forms a biofilm by depositing strong, adhesive exopolymers that promote bacterial cell attachment, thereby producing and reinforcing the biofilm structure on colonized surfaces [

7,

13]. The potential for bacterial growth and accumulation in the feedlot watering troughs represented a significant and constant source contributing to the occurrence of various local infections. However, the possible causes of clinical manifestations are influenced by several factors, including exposure to a high bacterial load, and the combined impact of various risk factors, such as dietary errors, environmental factors and management practices [

14].

S. paucimobilis is associated with infections in bones and soft tissues, often entering the body through traumatic injuries [

7]. Possible damage to the surface of the tongue in our case can result from the sharp edges of the water trough, licking sharp objects, or consuming rough, thorny hay. The observed lesions are probably caused by superficial mucosal injuries or penetrating traumas, creating an entry point for the bacteria. Probably due to the lower virulence of

S. paucimobilis, more serious local damage or septicaemia does not occur. The detection of a significant number of affected bulls within the batch may indicate a possible bioadaptation of the strain to the bovine host. This could indicate a potential transition from being primarily opportunistic to exhibiting more pathogenic behaviour. Recent studies indicate a shift in the perception of the pathogenic potential of

S. paucimobilis in humans. Once considered primarily a contaminant or commensal organism, it is now increasingly recognised as an emerging pathogen linked to significant morbidity and mortality. This changing perspective highlights the need for greater awareness and understanding of

S. paucimobilis in clinical settings. In humans,

S. paucimobilis is associated with both hospital-acquired and community-acquired infections. It causes a range of illnesses, including bacteraemia, sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis, peritonitis, and infections of the skin or urinary tract. The bacterium is considered an opportunistic pathogen, responsible for health issues in individuals with weakened immune systems or other underlying comorbidities, such as diabetes, alcoholism, cancer, or other chronic diseases [

8].

Various studies on the susceptibility of

S. paucimobilis and other Gram-negative bacteria have reported an alarming increase in colistin resistance [

1,

15]. In our case, the isolate's intermediate response to chloramphenicol and colistin indicates reduced susceptibility to these antibiotics. This is of particular concern, as intermediate results are typically the most selective for the development of resistance, warranting continued surveillance given the importance of both drugs in antimicrobial stewardship [

16]. Colistin is usually reserved as a last-line agent, so reduced susceptibility is particularly worrying [

17]. Resistance to penicillin, cephalexin, and cefapirin is consistent with a widespread decline in the effectiveness of β-lactams, likely due to intrinsic or acquired β-lactamase activity. This pattern of resistance to first-generation β-lactams while maintaining susceptibility to later-generation or combination agents reflects commonly reported resistance trajectories [

18]. Earlier research conducted in our country on antimicrobial resistance of heterotrophic bacteria in drinking water, including

S. paucimobilis, has established resistance to beta-lactams and nitrofurantoin [

13].

Currently, there is no evidence in the literature supporting direct transmission of

S. paucimobilis from animals to humans. The route of infection and associated risk factors remain poorly understood, highlighting the need for further research. Within the One Health framework, however, animals can function as intermediate hosts and carriers of microorganisms originating from shared environmental sources. More importantly, the close interactions between animals, humans, and the environment—particularly through common water supplies, soil, or contaminated surfaces—create opportunities for parallel exposure rather than true zoonotic transmission. These shared pathways are also critical for the transfer and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance, which may move between microbial communities in animals, humans, and the environment, even in the absence of direct pathogen exchange. Recognising these connections highlights the broader ecological context in which

S. paucimobilis and similar opportunistic pathogens emerge as threats to human health [

19].

5. Conclusions

S. paucimobilis is an opportunistic bacterium that affects a variety of hosts, including humans. The low detection of this bacterium in veterinary practice is likely due to its low virulence, which often goes unnoticed in most cases. Despite its low virulence, cases involving a large number of individuals can have a negative impact on productivity, health, and overall welfare on farms. These infections also raise concerns about the potential transfer of antibiotic-resistant strains from animals to humans, emphasizing the need for careful monitoring and responsible antimicrobial use. This report marks the first observation of high levels of oligosymptomatic and asymptomatic infections in cattle caused by S. paucimobilis, confirming soft tissue infection in animals in Bulgaria for the first time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B. B-M., P.M..; methodology: P.M., B.B-M; resources: B.B-M., P.M.; writing—original draft preparation: B.B-M., P.M.; writing—review and editing: B.B-M., P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this case are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TMR |

Total mixed ratio |

| LPS |

Lipopolysacharidae |

| GSL |

Glycosphingolipides |

References

- Ionescu, M. I., Neagoe, D. Ș., Crăciun, A. M., & Moldovan, O. T. (2022). The Gram-negative bacilli isolated from caves—Sphingomonas paucimobilis and Hafnia alvei and a review of their involvement in human infections. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(4), 2324. [CrossRef]

- Laupland, K. B., Paterson, D. L., Stewart, A. G., Edwards, F., & Harris, P. N. (2022). Sphingomonas paucimobilis bloodstream infection is a predominantly community-onset disease with significant lethality. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 119, 172-177. [CrossRef]

- Kuehn, J. S., Gorden, P. J., Munro, D., Rong, R., Dong, Q., Plummer, P. J., ... & Phillips, G. J. (2013). Bacterial community profiling of milk samples as a means to understand culture-negative bovine clinical mastitis. PloS one, 8(4), e61959. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. N., Lai, C. H., Chen, Y. H., Lin, H. L., Huang, C. K., Chen, W. F., ... & Lin, H. H. (2010). Sphingomonas paucimobilis bacteremia in humans: 16 case reports and a literature review. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 43(1), 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Güneş, Ö., Parlakay, A. Ö., Güney, A. Y., Coşkun, Z. N., Üçkardeş, F., Yahşi, A., ... & Bayhan, G. İ. (2025). Clinical characteristics, antibiotic susceptibilities, treatment characteristics and outcomes in pediatric patients with Sphingomonas paucimobilis bacteremia. Journal of Pediatric Disease/Türkiye Çocuk Hastalıkları Dergisi, 19(4). [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, A., Mascitti, M., Galeazzi, R., Marziali, A., Busco, F., & Procaccini, M. (2016). Oral ulcer by Sphingomonas paucimobilis: first report. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 45(10), 1280-1282. [CrossRef]

- El Beaino, M., Fares, J., Malek, A., & Hachem, R. (2018). Sphingomonas paucimobilis-related bone and soft-tissue infections: A systematic review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 77, 68-73. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S., Naushab, M., & Srinivasan, L. (2025). Unveiling a Hidden Pathogen: The Role of Sphingomonas paucimobilis Beyond the Hospital Walls. Cureus, 17(5). [CrossRef]

- Davenport, A. C., Mascarelli, P. E., Maggi, R. G., & Breitschwerdt, E. B. (2013). Phylogenetic diversity of bacteria isolated from sick dogs using the BAPGM enrichment culture platform. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 27(4), 854-861. [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, S., Seyitoglu, S., Altun, S. K., & Dinler, U. (2015). Detection of Sphingomonas paucimobilis infections in domestic animals by VITEK® Compaq 2 and Polymerase Chain Reaction. Archivos de medicina veterinaria, 47(1), 117-119. [CrossRef]

- Kenar, B., Aksoy, A., & Köse, Z. (2019). The new mastitis agents emerged in cattle in Turkey and an investigation of their antimicrobial susceptibility. Kocatepe Veterinary Journal, 12(4), 400-406. [CrossRef]

- Zeynali Kelishomi, F., Mohammadi, F., Khakpoor, M., Malekmohammadi, R., & Nikkhahi, F. (2023). Isolation of Sphingomonas paucimobilis from an ocular infection and identification using ribosomal RNA gene: First case report from Iran. Clinical Case Reports, 11(7), e7715. [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanova, Z., Tsvetkova, I., & Najdenski, H. (2022). Antimicrobial resistance of heterotrophic bacteria in drinking water-associated biofilms. Water, 14(6), 944. [CrossRef]

- Licitra, F., Perillo, L., Antoci, F., Piccione, G., Giannetto, C., Salonia, R., Giudice, E., Monteverde, V., & Cascone, G. (2021). Management Factors Influence Animal Welfare and the Correlation to Infectious Diseases in Dairy Cows. Animals, 11(11), 3321. [CrossRef]

- Aboelnasr, N. M., Abu-Elghait, M., Gebreel, H., & Youssef, H. I. (2024). Prevalence of Colistin resistance among difficult-to-treat Gram-negative nosocomial pathogens: An emerging clinical challenge. Microbial Biosystems, 9(2), 166-178. [CrossRef]

- Urban-Chmiel, R., Marek, A., Stępień-Pyśniak, D., Wieczorek, K., Dec, M., Nowaczek, A., & Osek, J. (2022). Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—A review. Antibiotics, 11(8), 1079.

- Singh, S., Sahoo, R. K., & Sahu, M. C. (2025). Understanding Recent Developments in Colistin Resistance: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics, 14(10), 958. [CrossRef]

- LaPlante, K. L., Dhand, A., Wright, K., & Lauterio, M. (2022). Re-establishing the utility of tetracycline-class antibiotics for current challenges with antibiotic resistance. Annals of Medicine, 54(1), 1686-1700. [CrossRef]

- Meier, H., Spinner, K., Crump, L., Kuenzli, E., Schuepbach, G., & Zinsstag, J. (2022). State of knowledge on the acquisition, diversity, interspecies attribution and spread of antimicrobial resistance between humans, animals and the environment: a systematic review. Antibiotics, 12(1), 73. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).