Introduction

Given the increasing demand for white meat and derived products, there is currently an intensification of animal production in general, particularly in the poultry sector. This growth in animal production has been accompanied by the development of farming techniques, which has led to an increase in pollutant emissions into the atmosphere (Roman et al., 2019). It is now estimated that nearly half of the mass of feed and water used in livestock farming is lost in gaseous form during animal production and effluent management (Robin et al., 2010).

Pollutant emissions from livestock farms have been the subject of numerous publications (Rokicki & Kolbuszewski, 1996; IPCC, 2007; Mosquera et al., 2012; ADEME, 2012; FAO, 2017; Wathes, 2019). They are characterized by temporal and spatial variability, which makes their estimation complex. The methods for quantifying these emissions depend on various objectives as well as the financial resources available to farmers (Li & Xin, 2010).

The measurement of pollutant concentrations can be carried out using physical methods (CORPEN, 2001), such as absorption spectroscopy, or chemical methods, such as gas chromatography or bubbling. These methods are generally used within well-defined processes, such as source emission measurements, remote source measurements, or mass balance calculations (Gac et al., 2007). Additionally, emission measurements often rely on observing concentration differences between the inside and outside of buildings (ADEME, 2010).

Many so-called "operational" measurement devices are used. However, they are often costly and/or complex to implement. The methodologies applied also influence the representativeness of the measurements. Indeed, they can lead to significant differences in results (Hassouna & Eglin, 2015). Proposing a set of reference measurement strategies adapted to the diversity of farming systems has therefore become a current concern, requiring a better understanding of emissions and the mechanisms behind their formation (ADEME, 2010). Exploring new research avenues is necessary to better understand these mechanisms. Modeling is an option for estimating emissions, but it must also excel in mastering knowledge related to the formation and emission of pollutants. Currently, the typologies used in emission inventory calculations are based on two types of effluents: solid or liquid, i.e., manure or slurry (Ponchant et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the development of regulations on gaseous emissions requires the acquisition of references regarding emissions at different stages of the farming system. In this bibliographic article, we will enumerate the different sources of pollution in poultry farming buildings and their consequences on agriculture.

Sources of Pollutant Emissions in Poultry Houses

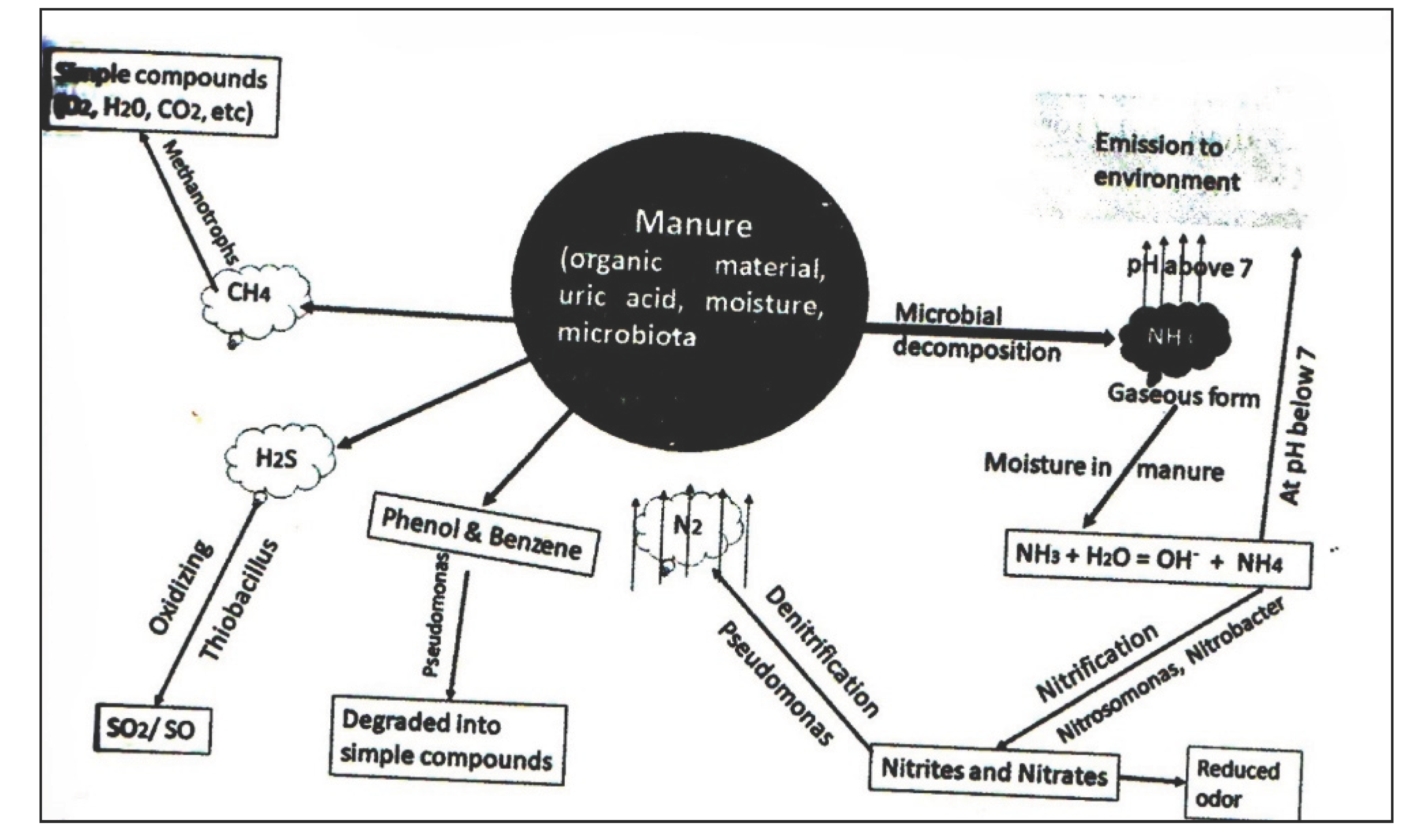

Figure 1.

Biochemical pathways for producing malodorous gases (Garda et al., 2024)

Figure 1.

Biochemical pathways for producing malodorous gases (Garda et al., 2024)

Poultry housing systems and their manure storage structures contribute significantly to the emission of gases, odors, and dust into the atmosphere. While poultry farming produces methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O) to a lesser extent, ammonia a volatile, polluting, and odorous compound is the primary gas emitted by the poultry industry (CITEPA, 2010). It is estimated to account for 9% of methane emissions, 6% of nitrous oxide emissions, and 15% of ammonia emissions related to livestock (CORPEN, 2006).

Poultry farming also generates fine particles called aerosols (Wathes et al., 1997; Carey et al., 2004; Roumeliotis & Heyst, 2008) and contributes significantly to secondary dust emissions (Aarnink & Ellen, 2007). Most particles are suspended inside poultry houses, and up to 50% of ammonia volatilizes there (ADEME, 2012). Ammonia is considered a precursor of secondary particles, which form after the condensation of various chemical compounds in the air (Carey et al., 2004; Roumeliotis & Heyst, 2008; ADEME, 2012). At high atmospheric concentrations, it causes respiratory diseases in poultry (Al Mashhadani & Beck, 1985; Alloui et al., 2013).

Feed

A study by Aarnink et al. (1999) suggested that feed contributes only minimally to airborne dust in poultry houses. However, Godbout (2008) attributed 80–90% of dust in caged layer facilities to feed sources. Handling, preparing, and distributing feed in closed poultry houses generate significant amounts of dust (Maghirang et al., 1995).

Dust primarily originates from seed coatings and depends on the feed’s moisture and fat content (Aarnink & Ellen, 2007). Dust emissions decrease with higher feed moisture levels (Cambra-Lopez et al., 2010; Méda et al., 2015). The form of feed (meal, crumbles, and pellets) also affects dust production (Picard et al., 2013). Birds fed with meal produce more dust than those fed pellets (Aarnink & Ellen, 2007).

Certain feed ingredients generate more dust than others. Corn-based feeds produce less dust than sorghum- or wheat-based feeds (Heber et al., 1988). Barley generates more dust than corn (Thaler et al., 2002).

Feeding Equipment

Feed distribution and handling equipment also contribute to dust formation. In automated feeding systems, large amounts of dust can become airborne when feed spills from troughs or feeders (Li et al., 2005). Wasted feed due to spillage is likely a major factor in dust generation (Aarnink & Ellen, 2007). Feed on the floor can be crushed into smaller particles by trampling and become airborne.

A significant increase in particle emissions occurs after feed distribution, with further spikes from repeated passes of feed carts or automated feeders along the cages (Rousset et al., 2014).

Feces

Dried feces are a major source of particles in livestock buildings. The emission factors of particles, particularly PM10, in poultry buildings vary depending on the type of manure. They tend to be higher for manure than for droppings (GEREP, 2014). Dry droppings can emit up to 8% of dust particles in poultry housing.

The key factor lies in the dry matter content of the feces. It is closely linked to the internal environment of the building (temperature, humidity, and ventilation) as well as the frequency of manure removal (Mostafa, 2012). Aarnink et al. (1999) reported a significant contribution of crystalline dust to airborne dust in poultry houses, likely originating from mineral crystals formed from urinary components.

Animals

Animals themselves are a significant source of dust, with 2–12% of dust particles in poultry housing coming from the animals. This dust arises from skin flakes, down, or feathers (Djerou, 2006; Cambra-Lopez et al., 2010). The quantities released depend on both the number of animals and their weight (Armand, 2005; Mostafa, 2012). They are also related to animal activity, which itself depends on the poultry genotype (Ellen & Drost, 1997).

Moreover, dust becomes airborne primarily due to animal movement, which generates large amounts of dust from feed, feces, and litter (Aarnink & Ellen, 2007). The movement of animals creates air turbulence around them, dispersing settled particles and increasing particle concentration (Takai et al., 1998).

Similarly, stocking density has a major effect on dust production and emission, as it directly influences animal activity and also affects hen temperature, thereby increasing airborne microorganism concentrations (Sauter et al., 1981).

Dust production increases with the age and weight of birds (Redwine et al., 2002; Al-Homidan & Robertson, 2003). Up to the sixth week of growth, respirable aerosol concentrations in poultry houses increase with bird weight (Grub et al., 1965; Yoder & Van Wicklen, 1988). The main reason for this rise is likely the increased surface area of various dust sources—such as feed quantity, feces, or the skin surface of hens as animals grow (Gustafsson, 1999 ; Aarnink & Ellen, 2007).

Poultry House

The amount of dust in the air of livestock buildings is heavily influenced by the housing system (Seedorf et al., 1998; Ellen et al., 2000; Michel & Huonnic, 2003). Studies indicate that layer hens housed in aviaries consistently exhibit higher concentrations of airborne dust compared to cage systems, where hens have little or no access to litter (Takai et al., 1998). The type of building and manure management methods also affects particle emissions, particularly PM10 (Costa & Guarino, 2008).

The nature of the particles, which originate from the building structure, depends on the construction materials used. These materials are responsible for most of the mineral fraction of particles produced indoors, which can also come from the external environment. The exterior of the building can therefore be a source of dust when its air tightness is inadequate, particularly around air inlets. Dust then transfers from the outside to the inside of the building (Lim et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Table 1. Biological, physical and chemical pollutants removed from 1 m3 of poultry house ventilation air (Herbut, 1997)

Table 1.

Table 1. Biological, physical and chemical pollutants removed from 1 m3 of poultry house ventilation air (Herbut, 1997)

Season

|

Microflora

[colonies/m3 ] |

Dust

[mg/m3] |

Ammonia

[ppm] |

| Spring |

37600 |

4,7 |

7,0 |

| Summer |

22500 |

2,2 |

10,0 |

| Automn |

16500 |

7,4 |

9,0 |

| Winter |

59900 |

0,7 |

8,0 |

Factors Influencing Particle Formation in Poultry Farms

Several factors affect particle concentration in the air of poultry buildings: air temperature, relative humidity, ventilation rate, animal activity, stocking density, bird species and age, feed type and structure, and feeding method (Cambra-López et al., 2010). However, it is the combination of some of these factors that causes variations in dust levels (Wathes et al., 1997).

Studies conducted in poultry houses have shown that total temperature and relative humidity significantly influence total particle concentrations (Vucemilo et al., 2008). The evolution of emitted particle quantities reveals that increases in dust levels are accompanied by decreases in humidity (Grub et al., 1965). Indeed, a relative humidity of 70% or higher can contribute to low particle concentrations due to high equilibrium humidity (Takai et al., 1998). Conversely, relative humidity below 60%, especially in cold ambient temperatures, promotes an increase in airborne particles (Djerou, 2006).

This observation can be explained by the fact that any decrease in air humidity leads to drying, which raises dust levels in the ambient air of buildings. However, relative humidity can affect the ability to remove particles from surfaces where they settle, as well as the viability of airborne microorganisms.

Air temperature is the factor with the greatest impact on air quality. Indeed, it directly influences, through ventilation, the dry matter content of manure, which promotes increased dust emissions (CORPEN, 2006). Grub et al. (1965) described low dust production at 10°C, with quantities peaking between 15.6°C and 21°C and decreasing as temperatures approached 37.3°C. Small differences between outdoor and indoor temperatures are normally associated with higher ventilation rates, further demonstrating the strong influence of ventilation speeds on dust concentrations (Al-Homidan et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2009).

Ventilation

One of the factors that largely determines the concentrations and emissions of particles in livestock buildings is the ventilation rate. Positively linked to temperature and negatively to relative humidity, ventilation influences the distribution of particles in the airspace of livestock buildings (Cambra-López et al., 2010). Primarily designed to control temperature and humidity, ventilation systems, through these two parameters, affect particle concentrations, especially in winter, when they are higher due to low ventilation rates (Zhang, 2004). However, an increase in the ventilation rate does not necessarily lead to a proportional reduction in dust concentration in livestock buildings (Gustafsson, 1999). This seems to be primarily caused by a low sedimentation rate of particles when associated with high ventilation rates. Sedimentation is effective for larger particles.

Microclimate

Weather conditions are one of the parameters influencing the variability of particle emission factors in poultry buildings. These include daily variations as well as seasonal variations (Sun et al., 2010), where the ventilation rate is closely linked to the climate or season. Due to higher ventilation rates in summer compared to winter, lower concentrations and higher emission rates can be expected in summer, while higher concentrations and lower emission rates can be expected in winter (Redwine et al., 2002). Several studies have demonstrated higher mass concentrations of dust in winter than in summer (Hinz & Linke, 1998; Takai et al., 1998; Al-homidan et al., 2003). In contrast, Costa and Guarino (2008) report that PM10 emission factors are higher in warm periods (spring-summer) than in cold periods (autumn-winter). In the same context, Qi et al. (1992) attribute PM formation rates to enhanced ventilation in warm periods, which creates increased turbulence and raises the suspension of particles in the building's air.

Activities Conducted in the Poultry House

Daily tasks carried out in poultry buildings, such as feed distribution, egg collection, cleaning activities, or simply the intervention of the farmer or workers in manure removal, are likely to generate significant amounts of dust, as they influence bird activity and promote the formation and suspension of particles (Lim et al., 2003; Mostafa, 2012). It is important to note that the smaller the particles, the more they adhere to surfaces, and it is the airflows created by animal activity and human activity that are likely to suspend these particles in the air and keep them in that state (Pedersen & Takai, 1999).

Ammonia Emission Sources in Poultry Farming

Ammonia (NH₃) emissions from poultry farming facilities have become a major concern due to the negative effects of excessive release into the atmosphere (Liang et al., 2005; Coufal et al., 2006). These emissions are linked to livestock manure and contain nitrogen (N) excreted by the animals (Gac et al., 2007). This nitrogen may be mineral nitrogen contained in the organic matter of the manure before any decomposition, or it may result from the secondary decomposition of moistened organic matter (Peigne, 2003).

Ammonia emissions are therefore dependent on the management and fate of animal manure at different stages of a farm. They occur inside the poultry house and depend on factors such as housing systems, indoor climate control, and animal activity (Robin et al., 1999; CORPEN, 2003; ADEME, 2012; Hassouna & Eglin, 2015). Emissions also occur during manure storage, where nitrogen and carbon content depends on storage duration and treatment type (Steinfeld & Pandis, 2006; ADEME, 2012; Hassouna & Eglin, 2015; CORPEN, 2006). Additionally, ammonia is emitted during manure spreading and is influenced by the nature of organic matter, as well as manure redistribution during grazing (Peigne, 2003). Emission estimates for a given situation must also account for local environmental conditions (Hartung & Philips, 1994; Miola et al., 2014).

Effects of Poultry Houses Characteristics and Environmental Conditions on Pollutant Emissions

In laying hen houses, indoor air quality is essential for maintaining a healthy environment for workers and plays a crucial role in egg production (Choinière & Munroe, 1993; Rousset et al., 2016). Key indoor environmental factors include pollutant gas concentrations, temperature, relative humidity, light intensity, and airflow (Kilic & Yaslioglu, 2014).

Environmental parameters in poultry houses, such as temperature and humidity, vary with the age of the birds (ITAVI, 1997). To maintain an optimal indoor temperature at minimal energy cost, humidity levels should be kept between 55% and 75% (Boita & Verger, 1983). However, high humidity levels can contribute to pathogen spread and the release of harmful gases like ammonia.

Environmental conditions depend on farming systems and their management. Thus, emissions of certain gases vary significantly depending on farm type, design, and building management (Roumeliotis & Heyst, 2008). Ammonia emissions factors tend to increase with aviary systems and decrease in conventional cage systems (Shepherd et al., 2015). According to Rousset et al., (2016), dust levels in floor-raised systems are higher than in cage systems and exhibit greater variability. Among cage systems, furnished cages have higher dust levels than conventional cages, with the highest levels found in aviary systems.

Ventilation, used to dilute pollutant concentrations by supplying fresh air, plays a major role in ammonia emissions. In hot conditions, increased ventilation rates due to rising temperatures enhance airspeed over manure surfaces, which can temporarily increase NH₃ emissions (Méda, 2011). Ammonia volatilization depends on air movement near the emitting surface. However, in the long term, ventilation reduces NH₃ emissions by drying out manure (Groot Koerkamp, 1994; Hartung & Philips, 1994).

High ammonia levels (above 25 ppm) in poultry houses can negatively affect production performance and bird health, leading to respiratory issues, poor weight gain, reduced egg production, and higher feed conversion ratios (Alloui et al., 2013; Cavalchini et al., 1990; Kenneth et al., 2003).

Conclusions

The design and equipment of a poultry house must ensure the well-being of the animals and optimal production while minimizing the emission of gases and dust into the atmosphere. These polluting emissions are closely linked to farming practices that influence their formation and release. Therefore, for emission estimates to reflect reality and for progress in reduction to be effective, it is necessary to specify the typology of farming systems, hence the importance of distinguishing their specificities in terms of structural characteristics and farming management. Gaseous emissions are automatically linked to manure, while dust is primarily related to feed, though this does not mean they are the only sources of emissions in poultry farming. The modernization of farming buildings has led to improved living conditions for the animals. Pollutants emitted by the poultry industry are harmful not only to the animals but also to the human environment. They can lead to ecological disasters, especially in the field of agriculture.

The application of dietary interventions (enzymes, probiotics, prebiotics, plant extracts, herbs, spices, and essential oils) could be a promising strategy for mitigating the emission of noxious gases. In addition to improving sustainability, it would also improve the production performance and health of the poultry.

Ethical considerations

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no know competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Roelofs, P. F. M. M.; Ellen, H. H.; Gunnink, H. Dust sources in animal houses. Proceedings International Symposium on Dust Control in Animal Production Facilities, Aarhus, Denmark; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aarnink, A.J.A.; Ellen, H.H. Processes and factors affecting dust emissions from livestock production, paper presented at how to improve air quality. International Conference Maastricht, Netherlands; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ADEME. Reference procedures for measuring gaseous pollutant emissions from livestock buildings and livestock effluent storage. 2010. Available online: https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-02602954.

- ADEME. Agricultural particle emissions into the air: Current situation and levers for action. 2012. Available online: https://www.cancer-environment.fr/app/uploads/2023/ADEM-2012_Emissions_agricoles_PM.pdf.

- Al Homidan, A.; Robertson, J.F. Effect of litter type and stocking density on ammonia, dust concentrations and broiler performance. British Poultry Science 2003, 44, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alloui, N.; Alloui, M.N; Bennoune, O.; Bouhentala, S. Effect of ventilation and atmospheric ammonia on the health and performance of broiler chickens in summer. Journal World's Poultry Research 2013, 3(2), 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Al Mashhadani, H.E.; Beeck, M.M. Effect of atmospheric ammonia on the surface ultrastructure of the lung and trachea of broiler chicks. Poultry Science 1985, 64(11), 2056–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, E.C. Study of the carriage of respiratory pathogens in mulard ducks and clinical consequences. Thesis, Toulouse (in French). National Veterinary School, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boita, A.; Verger, M.; Lecere, Y. Practical guide for breeding farmyard birds and rabbits; in French; Ed. Solar: Paris, 1983; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalchini, L.G.; Cerolini, S.; Mariani, R. Environmental influences on laying hens production. In Poultry farming in the Mediterranean; in French; Sauveur, B., Ed.; Montpellier, 1990; Volume CIHEAM (7), pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cambra-López, M.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Zhao, Y.; Calvet, S.; Torres, A.G. Airborne particulate matter from livestock production systems: A review of an air pollution problem. Environmental Pollution 2010, 158, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.B.; Lacey, R.E.; Mukhtar, S. A review of literature concerning odors, ammonia, and dust from broiler production facilities: 2. Flock and house management factors. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2004, 13, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choinière, Y; Munroe, J.A. Impact of air quality on the health of people working in livestock buildings; Ontario, Canada, 1993; Available online: https://www.agrireseau.net/documents/Document_93238.pdf.

- CITEPA. Inventory of atmospheric pollutant emissions in France - Sectoral series and extended analyses - SECTEN format; (in French). Interprofessional Technical Center for the Study of Atmospheric Pollution: Paris, 2010; p. 642p. [Google Scholar]

- CORPEN. Ammonia emissions from agricultural sources into the atmosphere. State of knowledge and prospects for reducing emissions; Paris (in French). Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- CORPEN. Ammonia and nitrogen greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture; Paris (in French). Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- CORPEN. Estimation of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, copper, and zinc emissions from pigs. In fluence of feeding practices and animal housing on the nature and management of the excrement produced; Paris (in French). Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Guarino, M. PM10 and fine particulate matter concentration and emission from three different type of laying hens houses. International Conference, Ragusa-Italy, September 15-17; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coufal, C.D.; Chavez, C.; Niemyerand, P.R.; Carey, J.B. Nitrogen emissions from broilers measured by mass balance over eighteen consecutive flocks. World's Poultry Science Journal 2006, 85, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djerou, Z. Influence of rearing conditions on performance in broiler chickens. Thesis, 140 p (in French). Mentouri Constantine University, Algeria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, H.H.; Drost, H. Technical possibilities for reducing dust concentrations in poultry houses. Report R9703, Practical Research into Poultry Farming; (in Duch). Beekbergen, 1997; p. 28 p. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, H.H.; Bottcher, R.W.; Von Wachenfelt, E.; Takai, H. Dust levels and control methods in poultry houses. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health 2000, 6(4), 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global livestock environmental model (GLEAM); Rome, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/gleam/en/.

- Gac, A.; Deline, F.; Bloteau, T. National inventory of gaseous emissions [CH4, N202, NH3] linked to the management of animal waste: bibliographic data and results for poultry farming; (in French). 7th poultry research day: Tours, 2007; pp. 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Garda, A; Hasliza, A.H.; Pavan, K.; Awis, Q.S.; Mohd, H M.Z. Controlling odour emissions in poultry production through dietary interventions: prospects and challenges. World Poultry Science Journal 2024, 80((4)), 1101–1122. [Google Scholar]

- GEREP. Guide for the assessment of air emissions of ammonia, methane, and particulate matter (PM10) and nitrous oxide for french pig and poultry farming. Ministry of Ecological and Inclusive Transition; Paris (in French). 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout, S. Emerging environmental issues in animal production. Agro-environmental conference, Drummondville. Final report. IRDA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Grub, W; Rouo, CA; Howes, JR. Dust problems in poultry environnements; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 1965; Volume 8, pp. 338–339. [Google Scholar]

- Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G. Review of emissions of ammonia from housing systems for laying hens in relation to sources, processes, building design and manure handling. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1994, 59, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, G. Factors affecting the release and concentration of dust in pig houses. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1999, 74(4), 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, M.; Eglin, T. Measuring gas emissions in livestock farming: greenhouse gases, ammonia and nitrogen oxides. In Diffusion INRA-ADEME; (in French). 2015; p. 314p. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, J.; Philips, V.R. Control of gaseous emissions from livestock building and manure stores. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1994, 57, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heber, A.J.; Stroik, M.; Faubion, J.M.; Willard, L.H. Size distribution and identification of aerial dust particles in swine finishing buildings. Transactions of the ASAE 1988, 31(3), 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbut, E. Ecological problems in poultry production. Symposium of the Department of Animal Hygiene, Warsaw University of Life Sciences (SGGW), (in Polish). Warsaw, June 11/12; 1997; pp. 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, T.; Linke, S. A comprehensive experimental study of aerial pollutants in and emissions from livestock buildings. Part 2. Results. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1998, 70(1), 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Repport of the IPCC Expert Meeting on Emission Estimation of Aerosols Relevant to Climate Change, 2-4 may; Genea, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 34. [Google Scholar]

- ITAVI. Litter. In Poultry Science and Technology - Technical management of poultry buildings; (in French). 1997; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth, DC; Gates, RS; Wheeler, EF; Zajaczkowski, JS; Topper, PA; Xin, H; LiangYI. Ammonia Emissions from broiler houses in Kentucky during winter. International Symposium on Gaseous and Odor Emissions from Animal Production Facilities, Horsens, Jutland, Denmark; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic, I.; Yaslioglu, E. Ammonia and Carbon Dioxide Concentrations in a Layer house, Asian Australasian Journal. Animal Science 2014, 27(8), 1211–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xin, H.; Liang, Y.; Gates, R.S; Wheeler, E.F.; Heber, A.J. Comparison of direct vs. indirect ventilation rate determinations in layer barns using manure belts. Transactions of the ASABE 2005, 48(1), 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H; Xin, H. Lab-scale assessment of gaseous emission from laying-hen manure storage as affected by physical and environmental factors. Transactions of the ASABE 2010, 53(2), 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y; Xin, H; Wheeler, E.F; Gates, R.S; Li, H; Zajaczkowski, P; Topper, A; Casey, K.D; Behrends, B.R; Zajaczkowski, F.J. Ammonia Emissions from U.S. Laying Hen Houses in Iowa and Pennsylvania. Transactions of the ASAE 2005, 48(5), 1927–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.T.; Heber, A.J; J-Qin, N.I; Gallien, J.X; Hongwei, X. Air quality measurements at a laying hen house: particulate matter concentrations and emissios. In Air Pollution from Agricultural Operations III, Proceedings of the 12-15 October 2003 Conference, Ed. H. Keener; 2003; pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Maghirang, R. G.; Riskowski, G. L.; Christianson, L. L.; Manbeck, H. B. Dust control strategies for livestock buildings - a review. ASHRAE Transactions 1995, 101 Pt 2, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Meda, B.; Hassouna, M.; Aubert, C.; Robin, P.; Dourma, J.Y. Influence of rearing conditions and manure management on ammonia and greenhouse gas emmisions from poultry houses. World's Poultry Science Journal 2015, 67, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, B. A dynamic approach to the flow of elements and energy in poultry production workshops with or without a pathway: Design and application of the Moldova model. Thesis, (In French). Agrocampus Ouest, France, 2011; p. 238p. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, V.; Huonnic, D.A. Comparison of welfare, health and production performance of laying hens reared in cages or in aviaries. British Poultry Science 2003, 44(5), 775–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miola, E.C.C.; Rochette, P.; Chantigny, M.H.; Angers, D.A.; Aita, C; Gasser, M.O.; Pelster, D.E.; Bertrand, N. Ammonia volatilization after surface application of laying-hen and broiler-chicken manures. Journal of Environment Quality 2014, 4(6), 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, J.; Winkek, A.; Groenestein, C.M.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Ogink, N.W.M. Greehouse gas emission from animal housing in the Netherland. In Biosystem Engineering; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, E. Air-polluted with particulate matters from livestock buildings. In book: Air quality new perspective. Ed. Tech Janeza Trdine 2012, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, S.; Takai, H. Dust response to animal activity. Proceedings Int. Symposium on Dust Control in Animal Production Facilities, Aarhus, Denmark, 30 May - 2 June; 1999; pp. 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Peigne, J. Method for evaluating agri-biological practices on air quality using agri-environmental indicators. Thesis, (in French). INRA, 2003; p. 155p. [Google Scholar]

- Picard, M.; Le Fur, C.; Melcion, J.P.; Bouchot, C. Granulometric characteristics of feed: the “point of view” of poultry. In INRA Animal Production; (in French). 2013; pp. p117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ponchant, P.; Robin, P.; Hassouna, M. Issues and assessment of gas emissions in poultry farms. 10th Poultry and Palmiped Research Days in Foie Gras, in French. La Rochelle, France; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, R.; Manbeck, H.B.; Maghirang, R.G. Dust net generation rate in a poultry layer house. Transactions of the ASAE 1992, 35(5), 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwine, J. S.; Lacey, R. E.; Mukhtar, S.; Carey, J. B. Concentration and emissions of ammonia and particulate matter in tunnel-ventilated broiler houses under summer conditions in Texas. Transactions of the ASAE 2002, 45(4), 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, P.; De Oliveira, P.A.; Kermarrec, C. Production of ammonia, nitrous oxide, and water by different pig litters during the growth phase. In Porcine Research Days in France; (in French). 1999; pp. 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, P.; Amand, G.; Aubert, C.; Babela, N.; Brachet, A. Reference procedures for measuring gaseous pollutant emissions from livestock buildings and livestock effluent storage. Final report. INRA Contrat n° 06 74 C0018, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, M.; Roman, K.; Roman, M. Methods of estimating particulates emission in agriculture exemplified by animal husbrandy. Proceeding of the ISC Hradec, Kralov 2019, 9(2), 260–268. [Google Scholar]

- Roumeliotis, T.S.; Heyst, B.J. Summary of ammonia and particulate matter emission factors for poultry operations. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2008, 17, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, E.; Kolbuszewski, T. Animal Hygiene. In Warsaw University of Life Sciences (SGGW); (in Polish). Development Foundation. Poland, 1996; pp. 5–151. [Google Scholar]

- Rousset, N.; Guingand, N.; Dezat, E.; Lagadec, S.; Jegou, J.Y.; Dennery, G.; Chevalier, D.; Boulestreau-Boulay, A.L.; Dabert, P.; Berraute, Y.; Allain, E.; Maillard, P.; Adji, K.; Hassouna, M.; Robin, P.; Ponchant, P.; Aubert, C. Bedding in livestock farming: identification, testing and evaluation of techniques or practices for better management of bedding with less material. Innovations Agronomiques (in French). 2014, 34, 403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Rousset, N.; Huneau-Salaün, A.; Guillam, M.T.; Ségala, C.; Le Bouquin, S. Qualité de l’air en élevage des poules pondeuses et impact sur l’environnement et la santé des éleveurs. Innovations Agronomiques (in French). 2016, 49, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Sauter, E.E.A.; Petersen, C.C.F.; Steele, E.E.E.; Parkinson, J.J.F.; Dixon, J.J.E.; Stroh, R.R.C. The airborne microflora of poultry houses. Poultry Science 1981, 60(3), 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedorf, J.; Hartung, J.; Schroder, M.; Linkert, K.H; Phillips, V.R; Holden, M.R; Sneath, R.W; Short, J.L; White, R.P; Pedersen, S.; Takai, H; Johnsen, J.O; Metz, J.H.M.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G.; Uenk, G.H.; Wathes, C.M. Concentrations and emissions of airborne endotoxins and microorganisms in livestock buildings in Northern Europe. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1998, 70(1), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric chemistry and physics: From air pollution to climate change, 2nd Edition; J. Wiley: New York, 2006; p. 1232 p. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, T.A.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Stinn, J.P.; Hayes, M.D.; Xin, H. Environmental assessment of three egg production systems-Part II. Ammonia, greenhouse gas, and particulate matter emissions. Poultry Science 2015, 94(3), 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Guo, H.Q.; Peterson, J. Seasonal odour, ammonia, hydrogen sulphide, and carb on dioxide concentrations and emissions from swine grower-finisher rooms. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2010, 60(4), 471–480. [Google Scholar]

- Takai, H; Pedersen, S; Johnsen, JO; Metz, JHM; Groot Koerkamp, PWG; Uenk, GH; Phillips, VR; Holden, MR; Sneath, RW; Short, JL; White, RP; Hartung, J; Seedorf, J; Schroder, M; Linkert, KH; Wathes, CM. Concentrations and emissions of airborne dust in livestock buildings in Northern Europe. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 1998, 70(1), 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.C.; Aarnink, A. J. A.; Koch, K.; Sauber, T.E. Effect of grain type, milling method, and diet form on dust production in a laboratory dust generator. Journal Animal Science 2002, Vol. 80 Suppl. 1, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Vucemilo, M; Matkovic, K; Vinkovic, B; Macan, J; Varnai, V.M; Prester, L.J; Granic, K; Orct, T. Effect of microclimate on the airborne dust and endotoxin concentration in a broiler house. Czech Journal of Animal Science 2008, 53(2), 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathes, C.M; Holden, M.R; Sneath, R.W; White, R.P; Phillips, V.R. Concentrations and emission rates of aerial ammonia, nitrous oxide, methane, carbon dioxide, dust and endotoxin in UK broiler and layer houses. British Poultry Science 1997, 38(1), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathes, C.M. Aerial emissions from poultry production. World Poultry Science Journal 2019, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, M.F.; Van Wicklen, G.L. Respirable aerosol generation by broiler chicken. Transactions of the ASAE 1988, 31, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Indoor Air Quality Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, Florida, 2004; p. 618 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Hofschreuder, P.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G. Evaluation of an impaction and a cyclone pre-separator for sampling high PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in livestock houses. Journal of Aerosol Science 2009, 40(10), 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).