Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

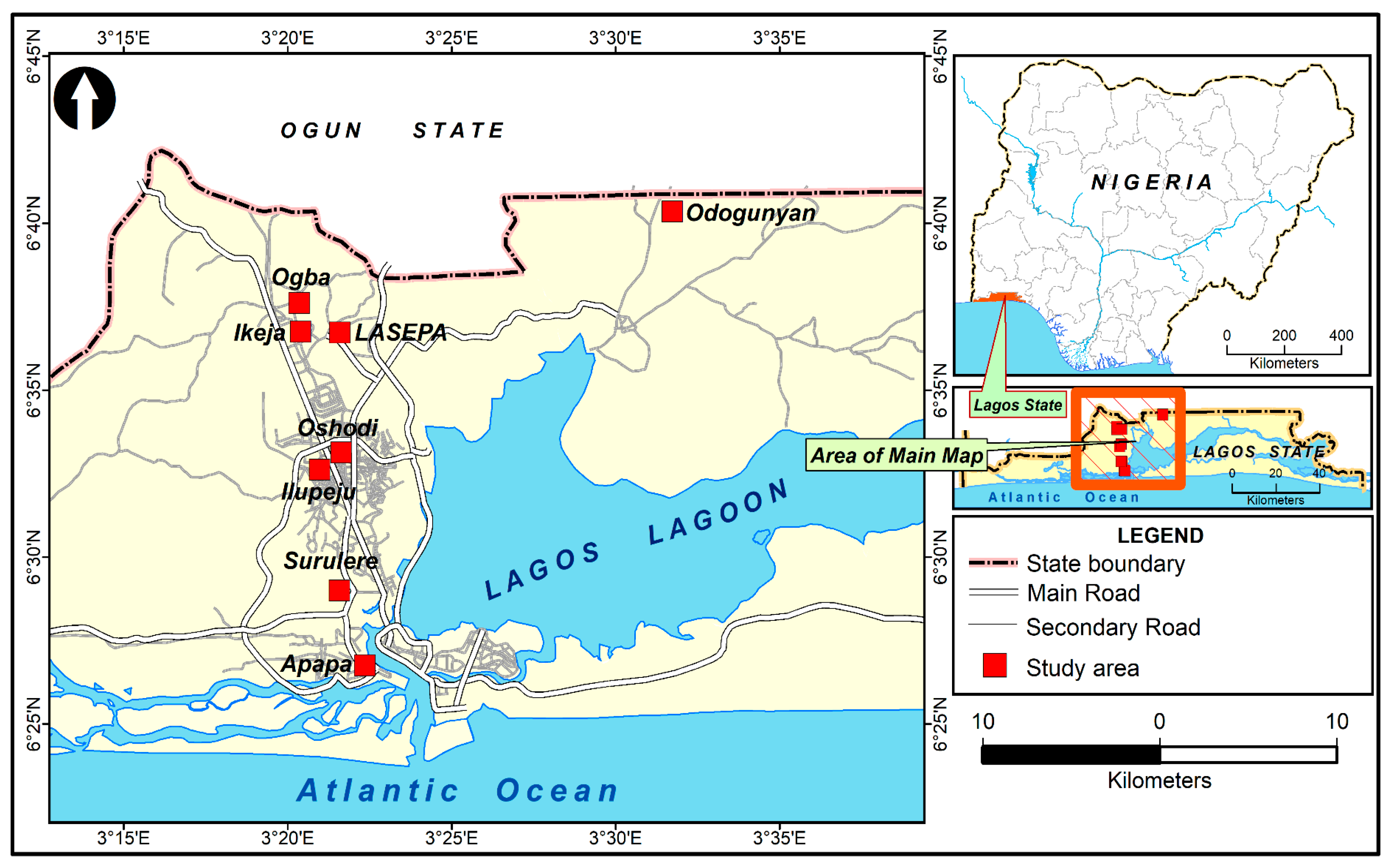

2.1. Study Area

| S/n | Industrial estate | Year of est. | Active industrial firm |

Size (Ha) |

Estate area | Estate type | Industrial nature |

| 1 | Ikeja/Ogba | 1959 | 75 | 180 | Mainland | IR | FBT, FM, C&P, DIP, PPP, TW, EE, WH WWG, MVP, CCT, EE, and P. |

| 2 | Oshodi/Ilupeju | 1962 | 57 | 330 | Mainland | IR | FBT, DIP, PPP, C&P, CP& IT, TW, WWG, MVP, WH and P. |

| 3 | Surulere | 1957 | 39 | 25 | Mainland | IR | FBT, WH, M&S, C, PPP, TW, DIP, E/P, EE, NMMP and MV |

| 4 | Apapa | 1957 | 31 | 100 | Coastal | IR | FBT, C&P, M&S, PPP, OMC, WH, CCT and TW |

| 5 | Odogunya | 1976 | 52 | 1582.27 | Mainland | IR | FBT, C&P, DIP, M&S, PPP, TW, EE, WH, FM, FW and E/P |

| 6 | Alausa (control) | 1996 | 0 | 1 | Mainland | GR | LASEPA premises, Government buildings, offices and residential areas |

3. Results and Discussion

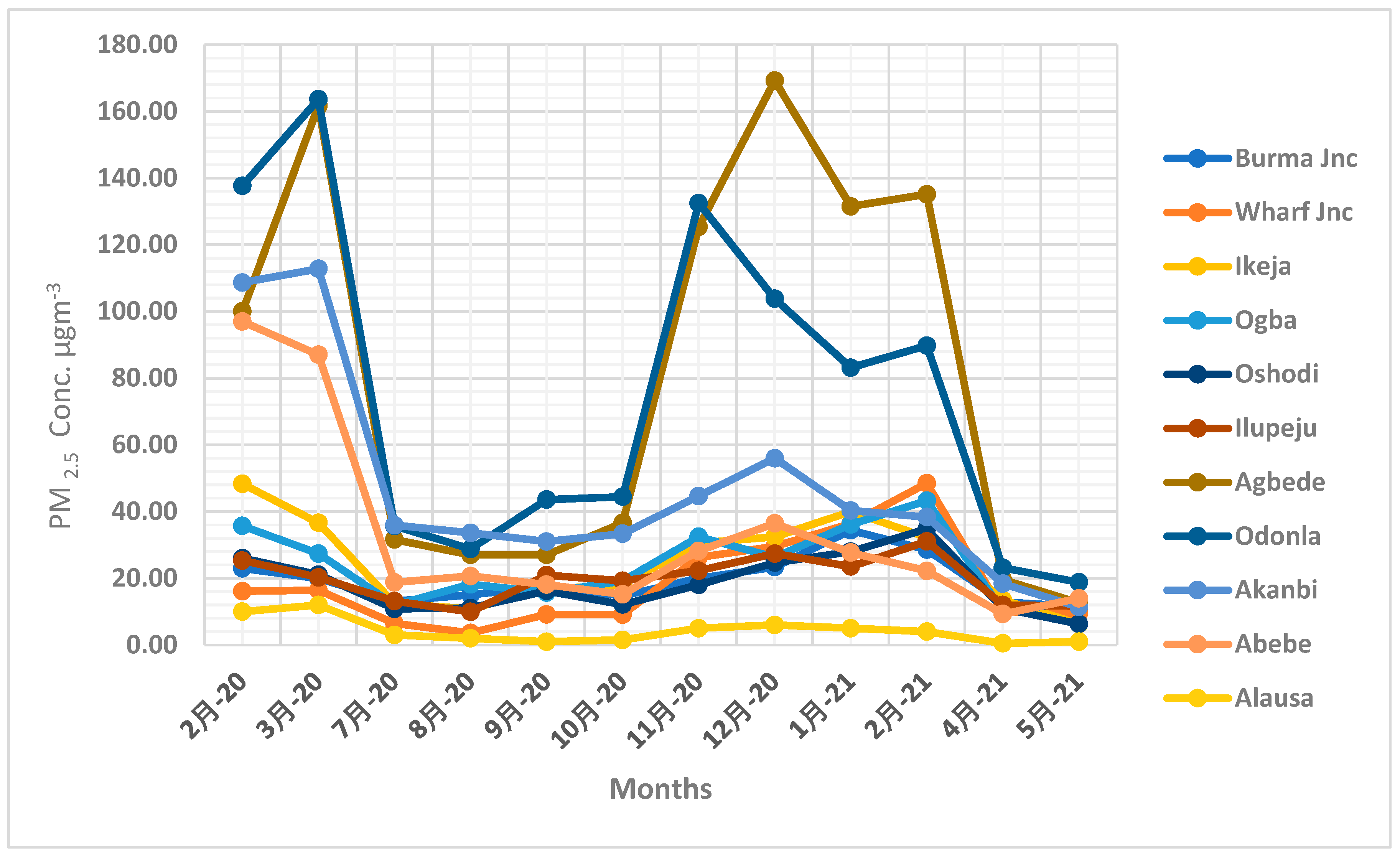

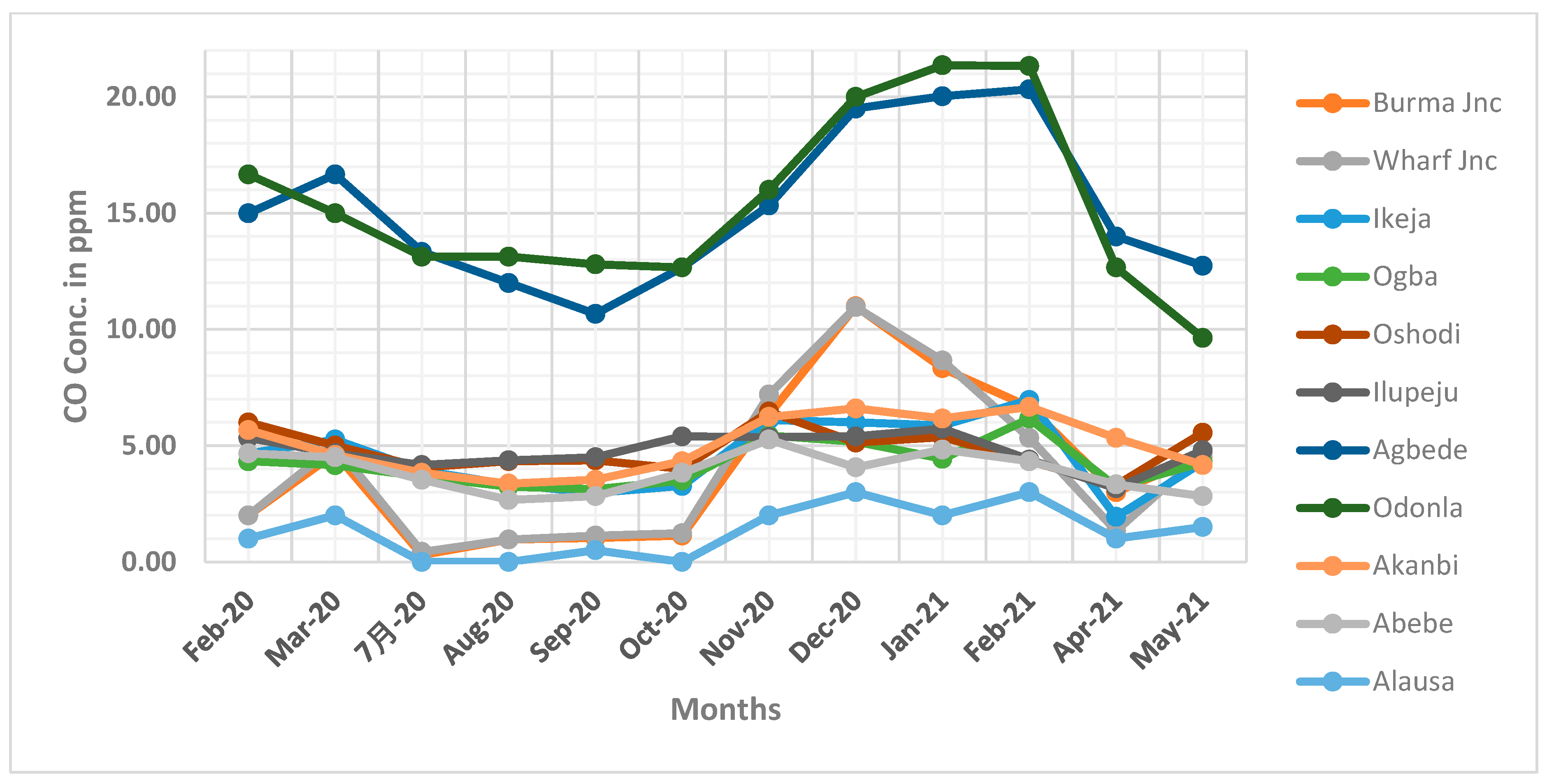

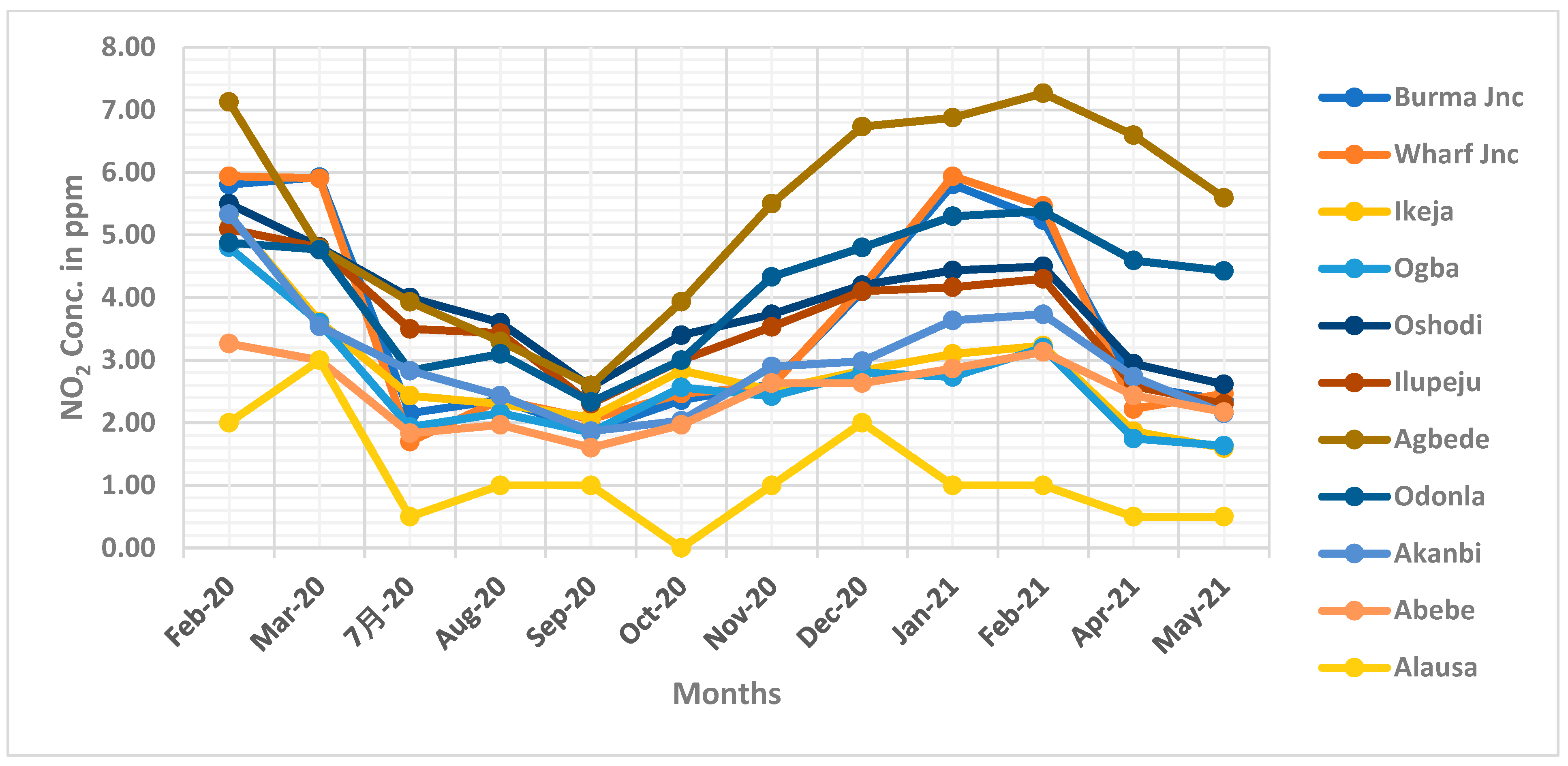

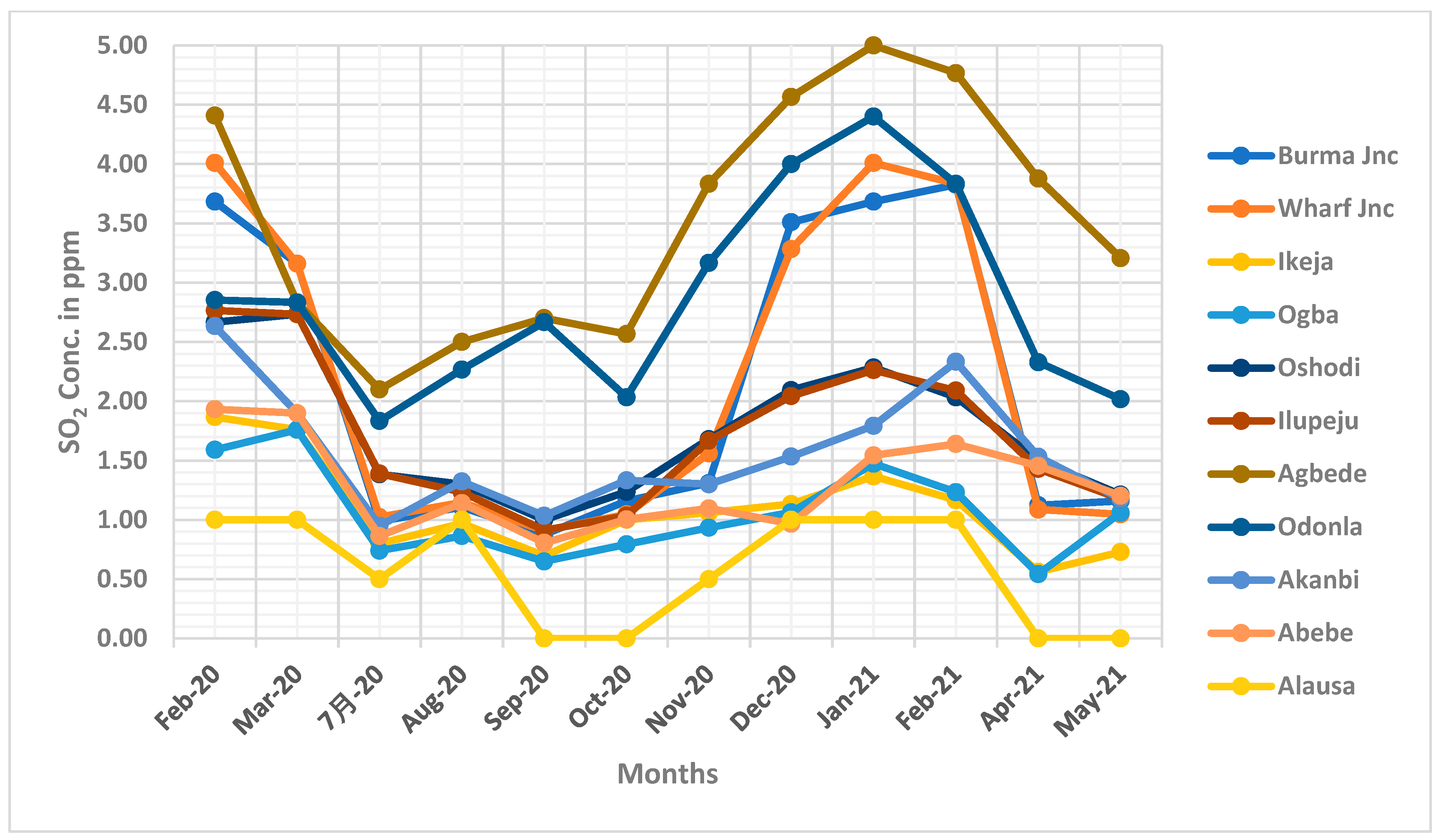

3.1. Variation in Ambient Monthly Gaseous and Particulate Pollutant Levels

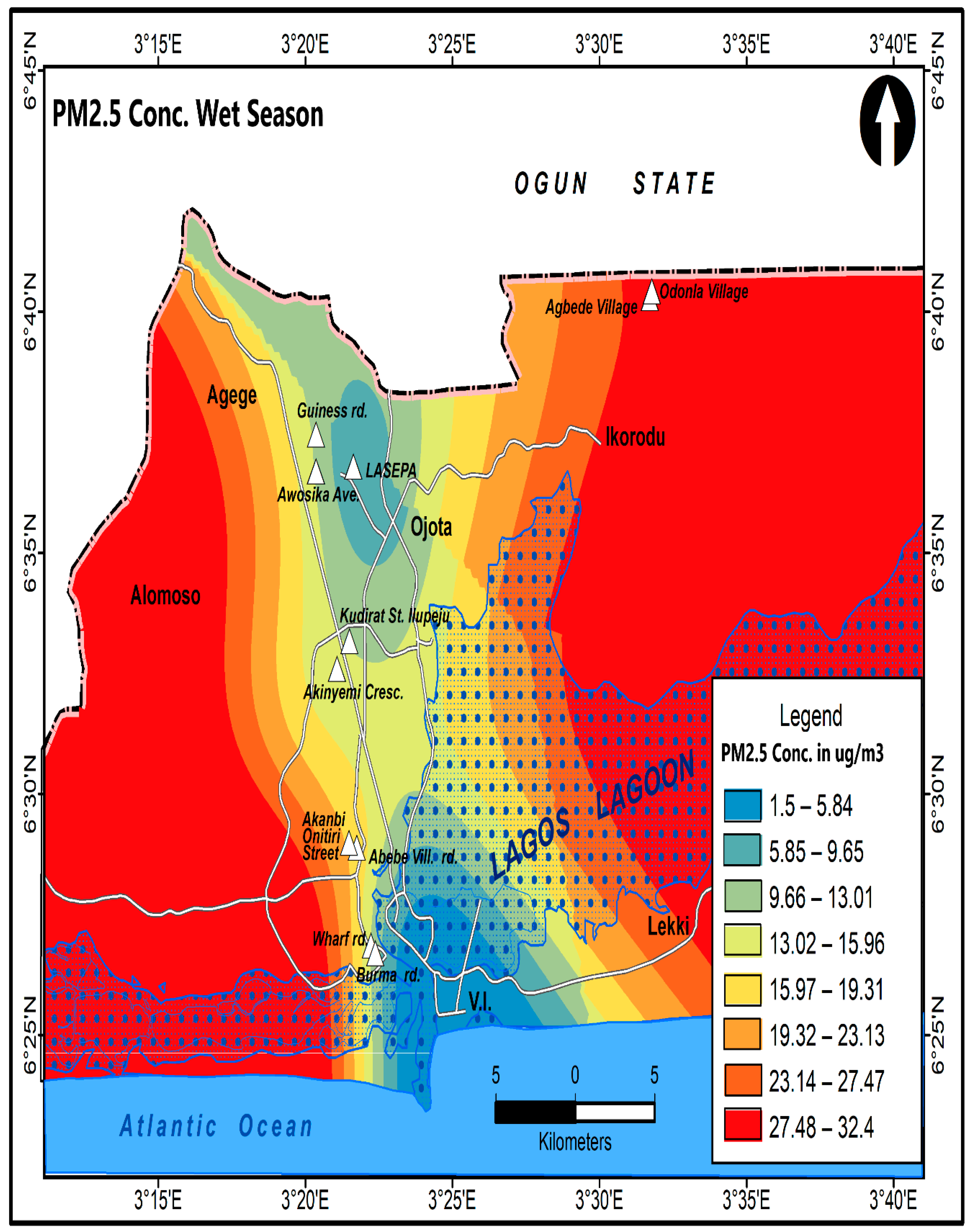

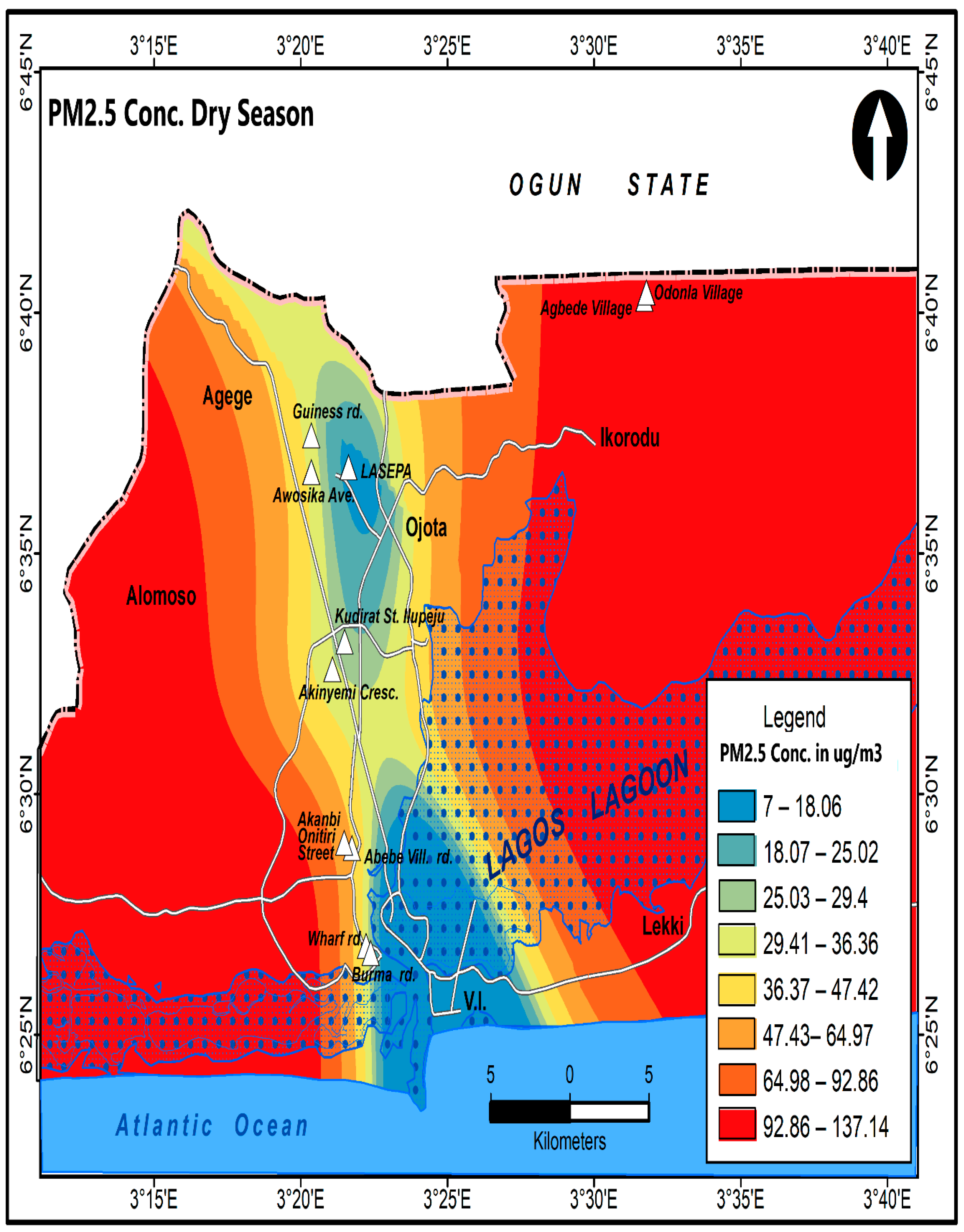

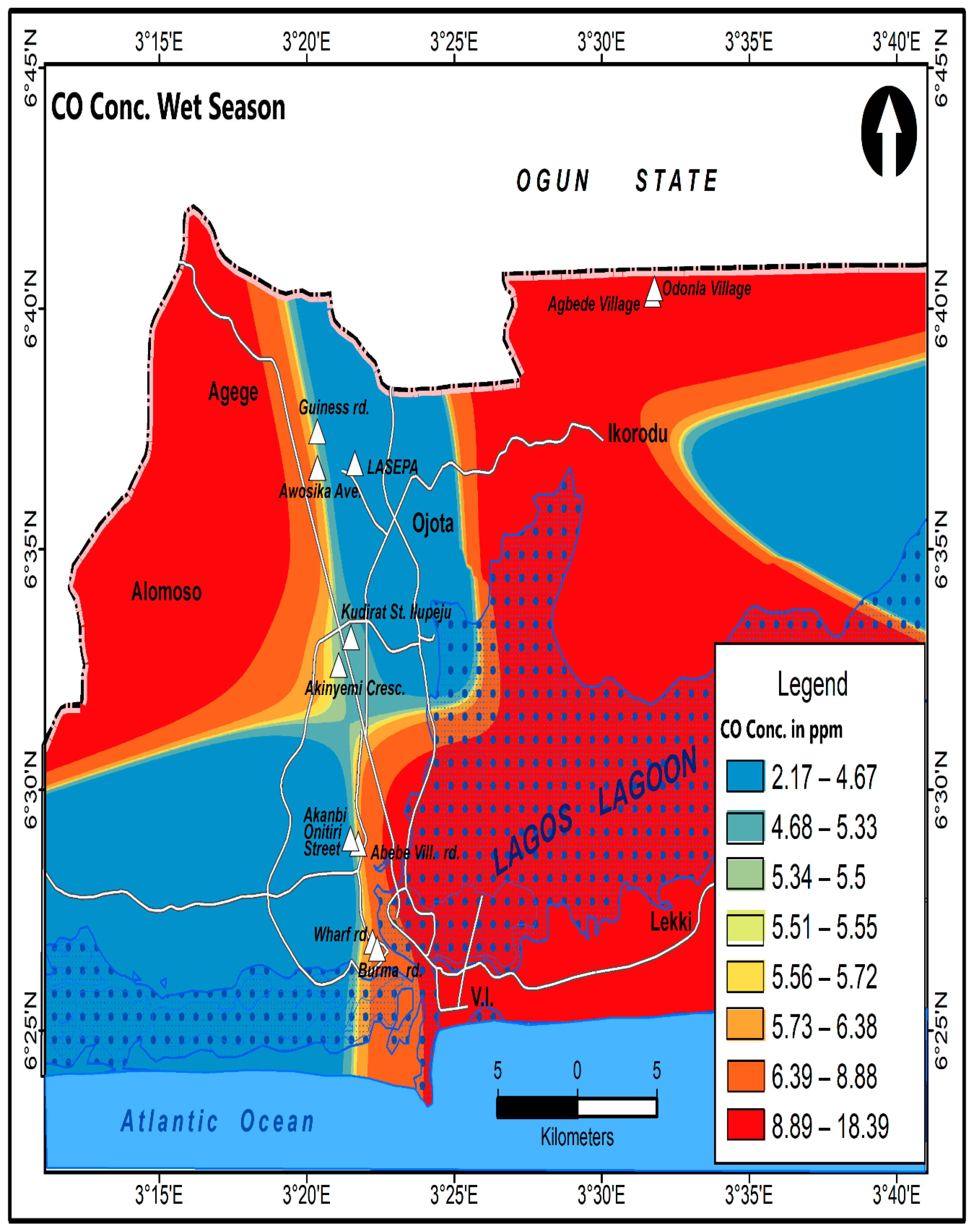

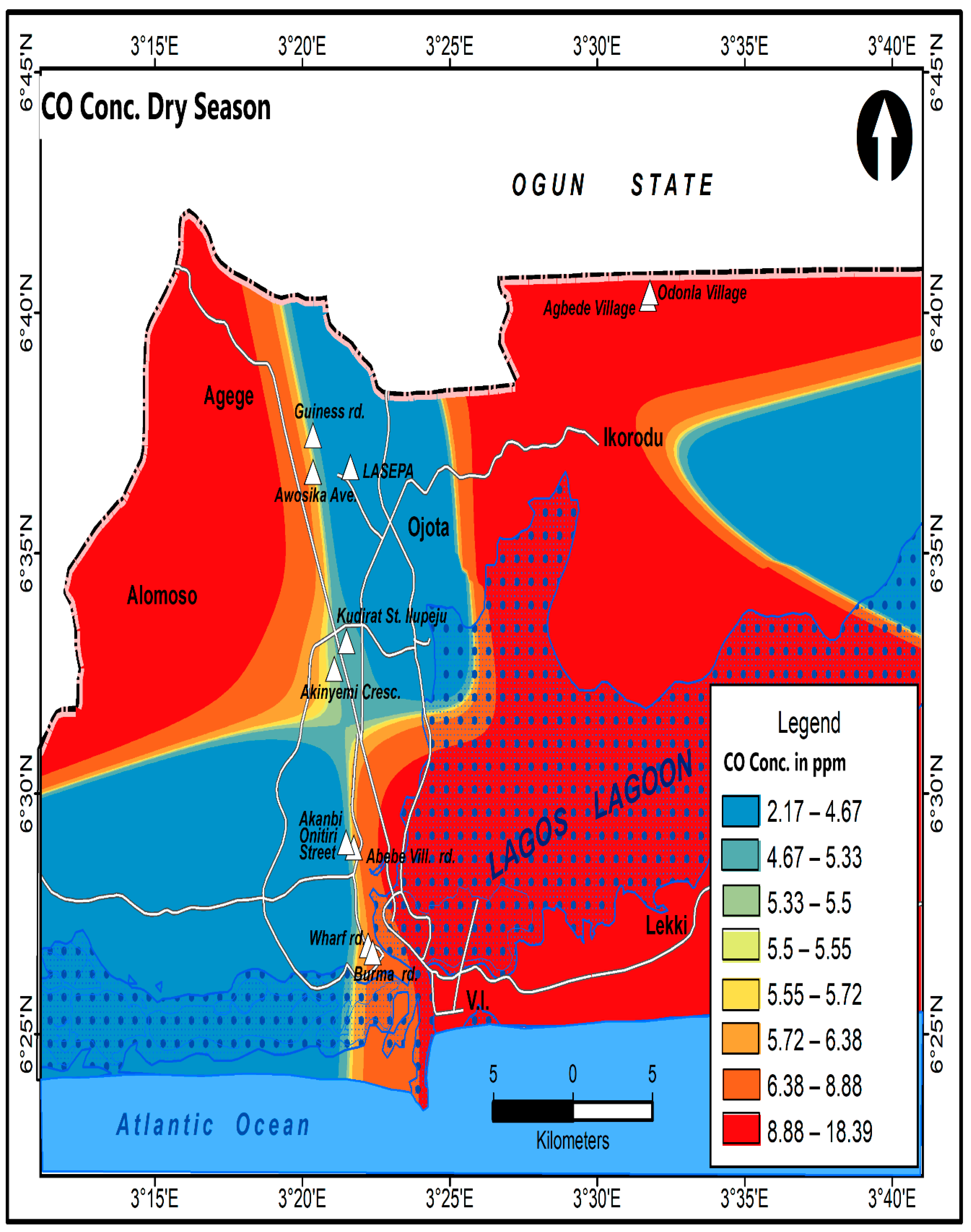

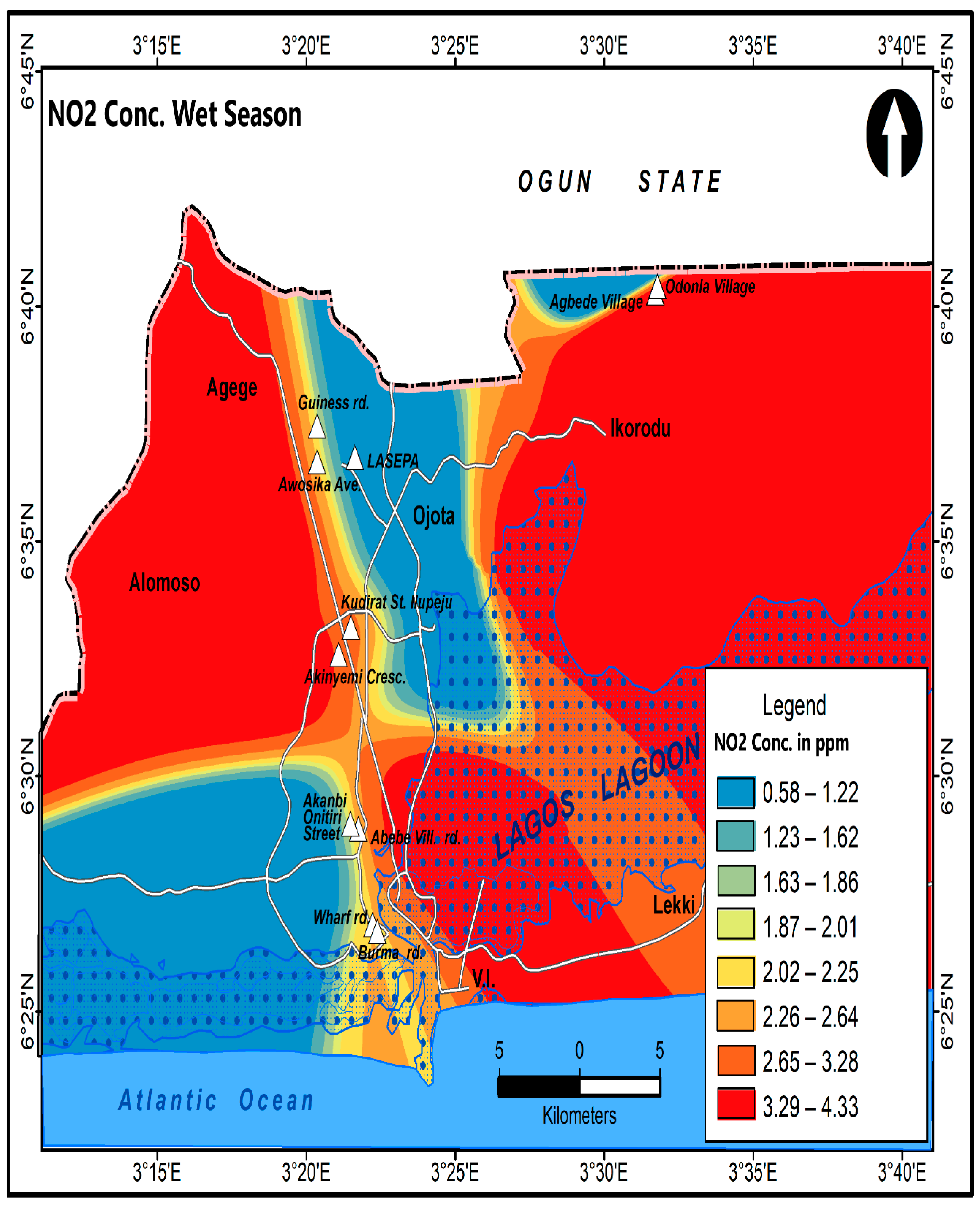

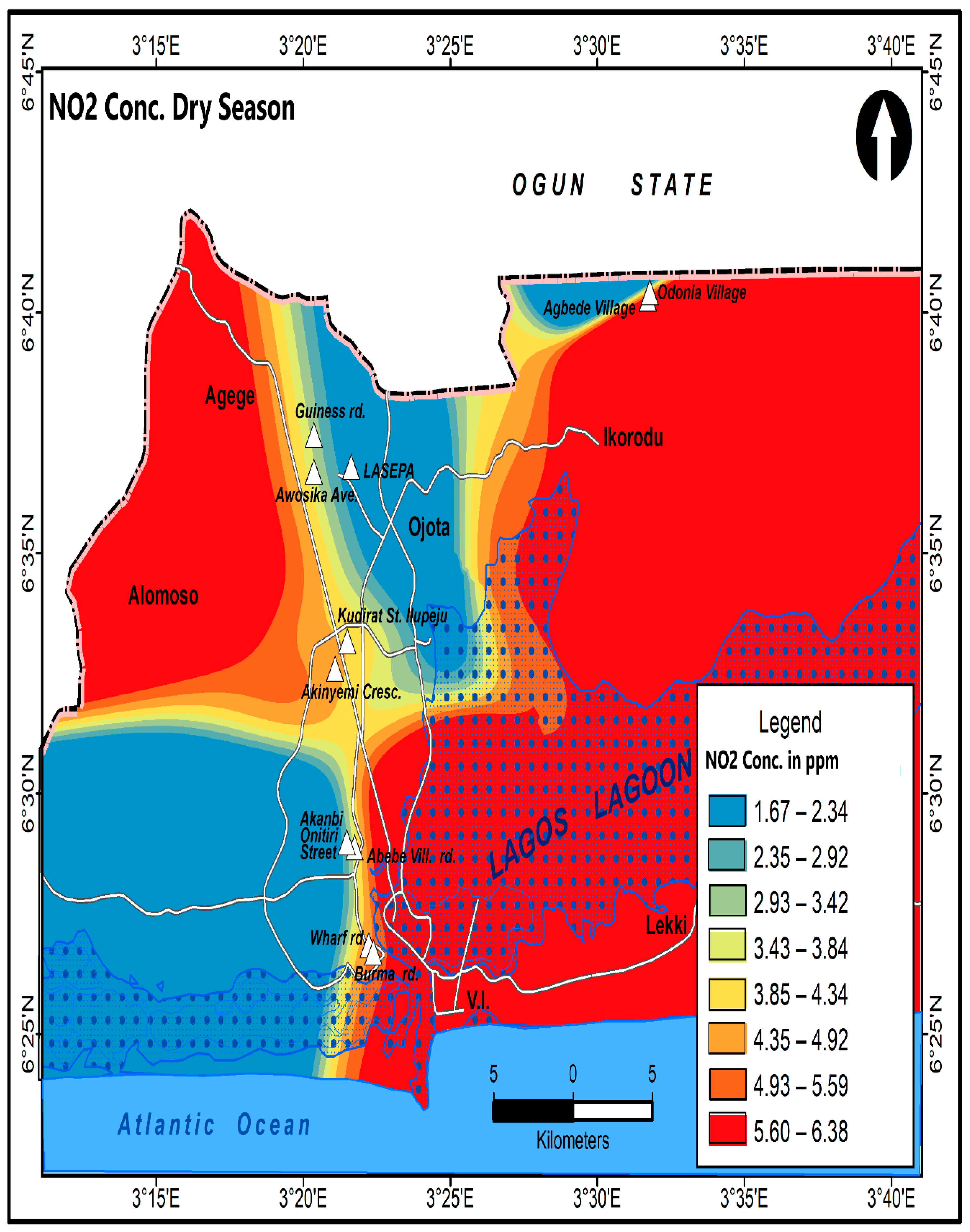

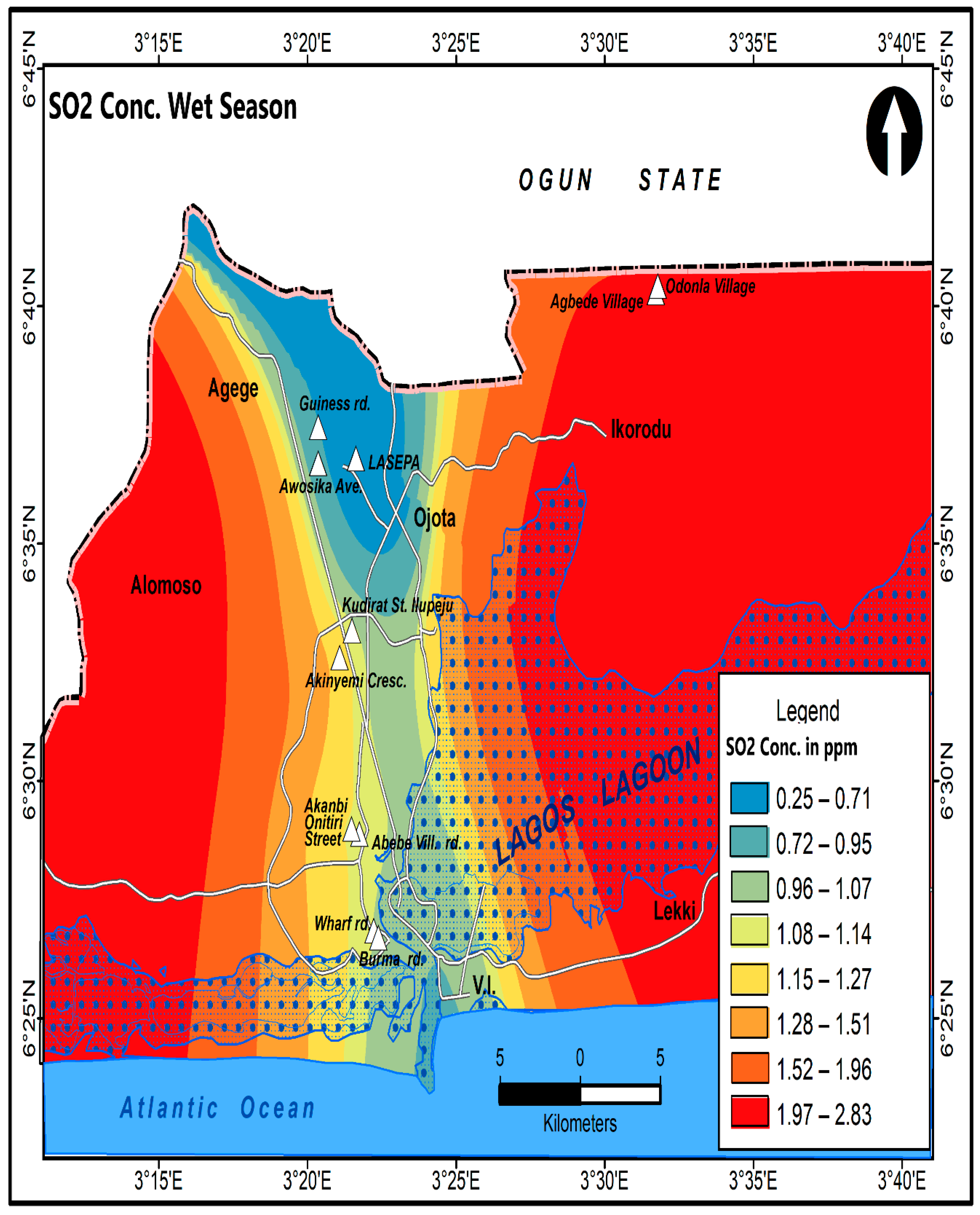

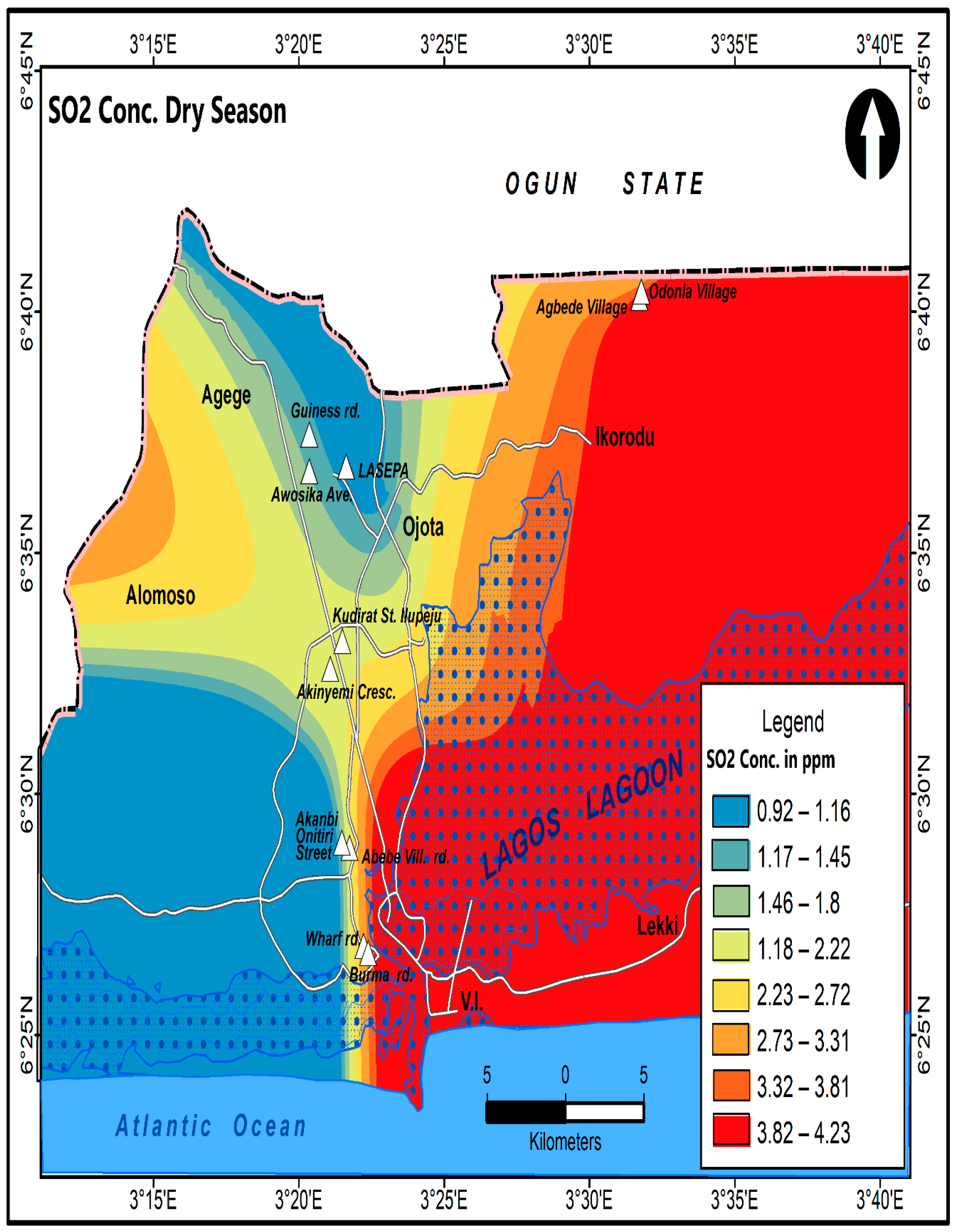

3.2. Spatial and Seasonal Variation in Gaseous and PM2.5 Levels

3.3. Monthly and Seasonal Variation in Gaseous and Particulate Pollutants

4. Conclusion

5. Recommendation

5.1. Limitation of the Study

5.2. Ethical Approval

Authors Contribution

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability declaration

References

- AbdRahman, N. H., Lee, M. H.S., and Latif, M. T. (2016) Evaluation Performance of Time Series Approach for Forecasting Air Pollution Index in Johor, Malaysia. Journal of Sains Malaysiana Vol. 45, No. 11, Pp.1625–1633.

- Adelana, S.M.A., Bale R.B., Olasehinde P.I., and Wu M. (2005) The impact of anthropogenic activities over groundwater quality of a coastal aquifer in Southwestern Nigeria. Aquifer Vulnerability and Risk, 2nd International Workshop 4th Congress on the Protection and Management of Groundwater Reggia di Colorno - Parma, 21-23 Settembre 2005.

- Agarwal, A. L. (1988). Air Pollution Control Studies and Impact Assessment of Stack and Fugitive Emission from CCI Akaltara Cement Factory, Project Sponsored by M/S CCI Akaltara Cement Factory, NEERI, Nagpur.

- Agbaire, PO and Esiefarienrhe E. (2009). Air Pollution Tolerance Indices of Some Plants around Otorogun Gas Plant in Delta State, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management; 13.1.:11-14.

- Ajayi, D.D. (2007) Recent Trends and Patterns in Nigeria’s Industrial Development, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, Africa Development, Vol. XXXII, No. 2, Pp. 139–155.

- Ajayi, D.D. (2011) Nigeria’s Industrial Development; Issues and Challenges in the New Millennium, Transaction on Ecology and the Environment Vol. 150, Pp.1-13.

- Akanni, C. O. (2008) Analysis of Street Level Air Quality Along Traffic Corridors in Lagos Metropolis. PhD Thesis. Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

- Akanni, C. O. (2010) Spatial and Seasonal analyses of traffic-related pollutant concentrations in Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria, African Journal of Agricultural Research Vol. 5. No.11, Pp. 1264-1272.

- Akeredolu, F.A., Olaniyi, H.B., Adejumo, J.A., Obioh, I.B., Ogunsola, O.J., Asubiojo, O.I., and Oluwole, A.F. (1994). Determination of elemental composition of TSP from cement industries in Nigeria using EDXRF technique. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research, A., 353, Pp. 542-545.

- Akinfolarin, O.M, Boisa N, and Obunwo C.C. (2017) Assessment of Particulate Matter-Based Air Quality Index in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. J Environ Anal Chem 4: 224. [CrossRef]

- Alfred, J. and Hyeladi, A. (2013). Assessment of Vehicular Emissions and Health Impacts in Jos, Plateau State. Journal of Research in Environmental Science and Toxicology Vol. 2.4. Pp. 80-86, www.interesjournals.org/jrest.

- Alkhdhairi, S.A., Abdel-Hameed, U.K., Morsy, A. A., and Tantawy, M.E. (2018) Air Pollution and its Impact on the Elements of Soil and Plants in Helwan Area. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 5.6.: 38-59. [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J. A., McVey A. E., Hegarty, J. D., Cross, E. B., Hasenkopf C. A., Lynch, R., Kennelly, E., Onasch, T., Awe, Y., Sanchez-Triana, E., and Kleiman, G. (2019). Evaluating the use of satellite observations to supplement ground-level air quality data in selected cities in low- and middle-income countries. Atmospheric Environment, 218, 1–14.

- Alvarez, C.M, Hourcade, R., Lefebvre, B., and Eva P. (2020). A Scoping Review on Air Quality Monitoring, Policy and Health in West African Cities, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 17, 9151. [CrossRef]

- Amato, F., Pandolfi, M., Escrig, A., Querol, X., Alastuey, A., Pey, J., Perez, N., Hopke, P.K. (2009). Quantifying road dust resuspension in urban environment by multilinear engine: a comparison with PMF2. Atmos. Environ. 43, 2770 to 2780.

- Amit, K.G., Tuluri, F. Tchounwou, P.B. Shaw, N., and Jain, K. G. (2015). Establishing the Association between Quarterly/Seasonal Air Pollution Exposure and Asthma Using Geospatial Approach. Aerosol and Air Quality Research, Vol.15: Pp.1525–1544. [CrossRef]

- Ana, G. R.E.E. (2011) Air Pollution in the Niger Delta Area: Scope, Challenges and Remedies, the Impact of Air Pollution on Health, Economy, Environment and Agricultural Sources. In Tech, www.intechopen.com/books/the-impact-of-air pollution-on-health-economy-environment-and-agricultural-sources/air-pollution-in-the-niger-delta-area-scopechallenges-and-remedies.

- Anake, W. U. (2016). Spatio-Temporal Variability of Trace Metals in Atmospheric Fine Particulate Matter from Selected Industrial Sites in Ogun State, Nigeria. A Published Thesis Submitted to The School of Postgraduate Studies of Covenant University, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria, https:// scholar. google. com/ citations? view_op =view_citation &hl=en&user=ztwqXYIAAAAJ&cstart=20&pagesize=80&citation_for_view=ztwqXYIAAAAJ:jgBuDB5drN8C. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/85162242.pdf.

- Anake, W.U., Eimanehi, J.E., Riman, H.S., and Omonhinmin, C.A. (2018). Tree Species for bio-monitoring and Green Belt Design: A Case Study of Ota Industrial Estate, Nigeria. 2nd International Conference on Science and Sustainable Development, IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 173, 012022. [CrossRef]

- Anil, I., and Alagha, O. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on the Air Quality of Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health. [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ortiz, N.E., Icaza-Noguera, G., and Ruiz-Rudolph, P. (2018). Thyroid Cancer Incidence in Women and Proximity to Industrial Air Pollution Sources: A Spatial Analysis in a Middle Size City in Colombia. Journal of Atmospheric Pollution Research, Science Direct. Vol. 9, Issue 3, Pp. 464-475.

- Asubiojo, O. I. (2016) Pollution Sources in the Nigerian Environment and their Health Implications, Ife Journal of Science Vol. 18, No. 4, Pp.1-8, Ile Ife.

- Asubioju, O.I, Obioh, I.B., Oluyemi, E.A., Oluwole, A.F., Spyrou, N, M., Faroooi, A.S., Arshed, W., and Akanle, O.A. (1993). Elemental Characterization of Airborne Particulates at Two Nigerian Locations During the Harmattan Season. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, Articles, Vol. 167, No. 2, Pp. 283-293.

- Asuoha, A. N and Osu, C. I. (2015) Seasonal Variation of Meteorological Factors on Air Parameters and the Impacts of Gas Flaring on Air Quality of Some Cities in Niger delta, Ibeno and its Environs, African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. Vol. 9 No.3 Pp.218-227, River state Nigeria.

- Atkinson, RW, Fuller GW, Anderson HR, Harrison RM, Armstrong B. (2010). Urban ambient particle metrics and health. A time series analysis. Epidemiology; 21:501–11.

- Bagherian, M., Alizadeh, T., and Rezaei, M. (2016). A comparison of health impacts assessment for PM10 during two successive years in the ambient air of Kermanshah, Iran. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bakiyaraj, R., and Ayyappan, D. (2014). Air Pollution Tolerance Index of Some Terrestrial Plants Around an Industrial Area, International Journal of Modern Research and Review, Vol. 2, Issue 1, Pp 1-7.

- Bang, KM. (2015). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in nonsmokers by occupation and exposure: a brief review. Curr Opin Pulm Med; 21:149–154.

- Baowen, L., Diego M. B., Marco P., Cang H., Akshay G., Inge H., Daniela A. L., Gaurav, S., Kevin C., Kevin F., Louisa L., Maharaj, B., Navid G., Yaning Q., Solomon A., Ali F. M., Bhaven N., Arunabha B., Fusong W., Andrew T., Zhuangzhuang L., Kasun W., Sahra N., Lei Y., Hao C., Benan S., Shubham G., Prince P., Amir H., Montasir A., and Nithin A. (2021). Air pollution perception in ten countries during the COVID-19 pandemic; Ambio. [CrossRef]

- Belis, C., Karagulian, F., Bo, L., Hopke, P. (2013). Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of Ambient Particulate Matter Source Apportionment Using Receptor Models in Europe. Atmos. Environ. 69, 94-108.

- Bhaskar, B. V. and Mehta, V. M. (2010) Atmospheric Particulate Pollutants and their Relationship with Meteorology in Ahmedabad. Journal of Aerosol and Air Quality Research, Vol. 10: Pp.301–315. [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M, Amann M, Burnett RT, Cohen A, Dentener, F, and Ezzati M. (2012). Exposure assessment for estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to outdoor air pollution Environ. Sci Technol; 46:652–60.

- Brimblecombe, P. (2021). Visibility Driven Perception and Regulation of Air Pollution in Hong Kong, 1968–2020. Environments, 8, 51. [CrossRef]

- Brown, JS, Gordon T, Price O, Asgharian B. (2013). Thoracic and respirable particle definitions for human health risk assessment. Part Fibre Toxicol;12. [CrossRef]

- Cadelis, G, Tourres R, Molinie J. (2014). Short-term effects of the particulate pollutants contained in Saharan dust on the visits of children to the emergency department due to asthmatic conditions in Guadeloupe, French Archipelago of the Caribbean, PLoS ONE;9.3.: e91136. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J., Lee S. C., Ho, K. F., Zou, S. C., Kochi F., Li, Y., Watson, J.G., and Chow, J.C. (2004). Spatial and Seasonal Variations of Atmospheric Organic Carbon and Elemental Carbon in Pearl River Delta Region, China. Elsevier Journal of Atmospheric Environment, Science Direct., Vol. 38, Issue 27, September 2004, Pp. 4447-4456. [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M., and Sevik, H. (2016). Change of Air Quality in Kastamonu City in Terms of Particulate Matter and CO2 Amount. 3401.4., 3394–3401.

- Chen, P., Bi, X., Zhang, J., Wu, J., and Feng, Y. (2014). Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution Characteristics and Human Health Risk of Exposure to Ambient PM2.5 in Tianjin, China. Particuology. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H. Xu, Q.S. Park, S.Y. Kim, J.H. Hwang, S.S. Lee, K.H., Lee, H.J and Hong Y.C. (2007). Seasonal variation of effect of air pollution on blood pressure, Journal of Epidemiology Community Health; Vol.61, Pp.314–318. Correspondence to: Professor Y-C Hong, Department of Preventive Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 28 Yongon-Dong, Chongno-Gu, Seoul 110- 799, South Korea. [CrossRef]

- Chuanglin, F., Haimeng L., Guangdong L., Dongqi S., and Zhuang, M. (2015). Estimating the Impact of Urbanization on Air Quality in China Using Spatial Regression Models. Journal of Sustainability, Vol.7, Pp.15570-15592. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. J, Brauer M., Burnett, R., Anderson, H R. Frostad, J. Estep, K. Balakrishnan, K. Brunekreef, B. Dandona, L. Dandona, R. Feigin, V. Freedman, G. Hubbell, B. Jobling, A. Kan, H. Knibbs, L. Liu, Y. Randall M., Morawska, L. Pope III, C. Shin, H. Straif, K. Shaddick, G. Thomas, M. Dingenen, R. V. Donkelaar, A. V. Vos, T. Murray, C. J L and Forouzanfar, M. H. (2017). Estimates and 25-Year Trends of The Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Ambient Air Pollution: An Analysis of Data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015.The Lancet, Vol. 389, Pp.1907–18.

- Currie, B. A., and Bass, B. (2008). Estimates of Air Pollution Mitigation with Green Plants and Green Roofs using the UFORE Model. 409–422. [CrossRef]

- Dappe, V., Uzu, G., Schreck, E., Wu, L., Li, X., Dumat, C., Moreau, M., Hanoune, B., Chul-Un R., and Sobanska, S. (2018). Single-Particle Analysis of Industrial Emissions Brings New Insights for Health Risk Assessment of PM. Journal of Atmospheric Pollution Research, Science Direct., Vol. 9, Issue 4, Pp.697-704. [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, C.A., and Vineis, P. (2015) Carcinogenicity of Ambient Air Pollution: Use of Biomarkers, Lessons Learnt and Future Directions. J Thorac Dis.; 7.1.: 67–95. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q., Lu, C., Norbäck, D., Bornehag, C., Zhang, Y., Liu, W., Yuan, H., Sundell, J. (2015). Early Life Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Childhood Asthma in China, Environmental Research 143, 83–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, K. and Kassomenos, P. (2018). Quantifying Daily Contributions of Source Regions to PM Concentrations in Marseille based on the trails of Incoming Air Masses. Journal of Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health, Vol. 11, Issue 5, Pp. 571–580.

- Ediagbonya, T. F, Tobin, A. E, Olumayede, E. G, Okungbwa, G. E, and Iyekowa, O. (2016) the Determination of Exposure to Total, Inhalable and Respirable Particles in Welders in Benin City, Edo State. Journal of Pollution Effluent Contamination 4:152. [CrossRef]

- Ediagbonya, T.F and Tobin, A.E. (2013). Air Pollution and Respiratory Morbidity in an Urban Area of Nigeria, Greener Journal of Environmental Management and Public Safety, Vol. 2 .1., Pp. 10-15.www.gjournals.org.

- Ekpenyong, C. E., Ettebong, E. O., Akpan, E E., Samson, T K., and Nyebuk, E. D. (2012). Urban City Transportation Mode and Respiratory Health Effect of Air Pollution: A Cross-Sectional Study among Transit and Non-Transit Workers in Uyo City. Nigeria. BMJ. [CrossRef]

- Eludoyin, O. M. (2013) Some Aspects of Physiologic Climatology in Nigeria Interdisciplinary Environmental Review, Vol. 14, No. 2, Pp.150–185.

- Escobedo, F. J, Wanger J. E, and Nowak D. J. (2008). Analyzing the cost-effectiveness of Santiago, Chile’s policy of using urban forests to improve air quality. Journal of Environmental Management; 86.1:148-157.

- Ezeugoh, R.I., Puett, R., Payne-Sturges, D., Cruz-Cano, R and Wilson, S.M. (2020) Air Quality Assessment of Particulate Matter Near a Concrete Block Plant and Traffic in Bladensburg, Maryland. 13 .3., 1009–1015. [CrossRef]

- Fagbohunka, A. (2014) Firms Location and Relative Importance of Location Factors among Firms in the Lagos Region, Nigeria, Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, Vol.4, No. 8, 73,. https:// d1wqtxts1xzle7. cloudfront. net/34228795/ Firms_ Location_and_Relative_Importance_of_Location_Factors_amongst_Firms_in_the_Lagos_Region__Nigeria-libre.pdf?1405649065.

- Fakayode, S.O. and Onianwa, P.C. (2002) Heavy Metal Contamination of Soil, and Bioaccumulation in Guinea grass. Panicum maximum. around Ikeja Industrial Estate, Lagos, Nigeria. Environmental Geology, 2002. 43:145–150. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-F., Ling, D.-L. (2003). Investigation of the noise reduction provided by tree belts. Landscape Urban Plan 63, 187–195.

- Fang, Y, Naik V, Horowitz LW, Mauzerall DL. (2013). Air pollution and associated human mortality: the role of air pollutant emissions, climate change and methane concentration increase from the preindustrial period to present. Atmos Chem Phys;13: 1377–94.

- Filho, M.A. P., Pereira, L.A.A., Arbex, F.F., Arbex, M., Conceição, G.M., Santos, U.P., Lopes, A.C., Saldiva, P.H.N., Braga, A.L.F. and Cendon, S. (2008). Effect of Air Pollution on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases in São Paulo, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, Vol. 41, No. 6, Pp. 526-532, www.bjournal.com.br.

- Gang, W., Shuiyuan C., Jianbing L., Jianlei L., Wei W., Xiaowen Y., and Liang T. (2015). Source Apportionment and Seasonal Variation of PM2.5 Carbonaceous Aerosol in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region of China. Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, Vol.187, Pp.143.

- Gang, Xu, Limin J., Suli Z., Man, Y., Xiaoming, Li, Yuyao, H., Boen, Z. and Ting, D. (2016). Examining the Impacts of Land Use on Air Quality from a Spatio-Temporal Perspective in Wuhan, China. Atmosphere, Vol.7, Pp.62.

- Gawronski, S. W., Gawronska, H., and Lomnicki, S. (2017). Plants in Air Phytoremediation. 83, 319–346. [CrossRef]

- Ghorani-Azam, A., Riahi-Zanjani, B. and Balali-Mood, M. (2016). Effects of Air Pollution on Human Health and Practical Measures for Prevention in Iran. Journal Research on Medical Sciences; Vol.21: Pp.65. [CrossRef]

- Gobo, A. E; Ideriah, T. J. K., Francis, T. E., Stanley, H. O. (2012). Assessment of Air Quality and Noise around Okrika Communities, Rivers State, Nigeria, J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage, Vol. 16 No.1 Pp.75 – 83.

- Golani-Azam, A., Riahi-Zanjani, B. and Balali-Mood, M. (2016) Effects of Air Pollution on Human Health and Practical Measures for Prevention in Iran. Journal Research on Medical Sciences; Vol.21: Pp.65. [CrossRef]

- Guaita, R, Pichiule M, Mate T, Linares C, and Diaz, J. (2011). Short-term impact of particulate matter PM2.5. on respiratory mortality in Madrid. Int J Environ Health Res; 21:260–74.

- Guillerm, N., and Cesari, G. (2015) State of the Art; Fighting Ambient Air Pollution and Its Impact on Health: From Human Rights to the Right to A Clean Environment. 19.8., 887–897.

- Guttikunda, S. K. and Gurjar, B. R. (2012). Role of Meteorology in Seasonality of Air Pollution in Megacity Delhi, India. Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, Vol. 184, Issue 5, Pp. 3199–3211.

- Hind, S. Y., Enaam, J. A, and Maitham A. S. (2021). Risk Assessment of Occupational Exposure to Air Pollution in Baghdad City. Annals of R.S.C.B., ISSN:1583-6258, Vol. 25, Issue 2, Pp. 686 - 700.

- Hongliang, Z., Yungang, W., Jianlin, H., Qi Y., and Xiao-Ming, H. (2016). Relationships between Meteorological Parameters and Criteria Air Pollutants in Three Megacities in China, United State of America. Corresponding author: Dr. Yungang Wang, carl.wang@erm.com.

- Hsu, C., Chiang, H., Chen, M., Chuang, C., Tsen, C., Fang, G., Tsai, Y., Chen, N., Lin, T., Lin, S., and Chen, Y. (2017). Ambient PM2.5 in the residential area near industrial complexes: Spatiotemporal variation, source apportionment, and health impact: spatiotemporal variation, source apportionment, and health impact. Science of the total environment, 590–591, 204–214. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Shaofei K.,; Mingming Z.,; Yingying Y.,; Liquan Y.,; Shurui Z.,; Qin Y., Jian W., Yi C.,; Nan C.,; Yongqing B., ;Tianliang Z.,; Dantong L.,; Delong Z; and Shihua Q. (2020). A 5.5-year observations of black carbon aerosol at a megacity in Central China: Levels, sources, and variation trends, Atmospheric Environment, Vol. 232. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Xie, R., and Yang, G. (2021). The impact of lockdown on air pollution: Evidence from an instrument; China Economic Review. [CrossRef]

- Hutton, G. (2011). Air Pollution-Global Damage Costs of Air Pollution from 1900 to 2050.Assessment Paper Copenhagen Consensus on Human Challenge.

- Ikamaise, V.C., Obioh, I. B., Ofoezie, I. E., and Akeredolu, F. A. (2001). Monitoring of total suspended air particulate in the ambient air of welding, car painting and battery charging workshops in Ile- Ife Nigeria. Global journal of pure and applied sciences, Vol. 7, No. 4, Pp. 743-748.

- Ileoje, NP. (2001) A New Geography of Nigeria, New Revised Edition. Longman Publishers: Ibadan, Nigeria.

- Ipeaiyeda, A. R., and Adegboyega, D.A. (2017) Assessment of Air Pollutant Concentrations Near Major Roads in Residential, Commercial and Industrial Areas in Ibadan City, Nigeria, Journal of Health and Pollution. Vol. 7, No. 13, JAMA Vol. 312 .15.: Pp. 1565-1580.

- Jafari, N, Ebrahimi, AA, Mohammadi, A, Hajizadeh, Y. and Abdolahnejad, A. (2017) Evaluation of Seasonal and Spatial Variations of Air Quality Index and Ambient Air Pollutants in Isfahan using Geographic Information System. Journal of Environmental Health Sustainable Development, Vol. 2, No. 2, Pp. 263-72.

- Jenq-Hwan, O., Shihn-Sheng, W., Chun-Hung, R.L., Tzu-Ying, W., and Yen-Hsia, W. (2017). Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Tuberculosis: Exploring the Optimal Exposure Assessment Taipei City Taiwan. Proceedings of ISER 64th International Conference, Nagoya, Japan, 7th -8th July 2017.

- Jian, H., Wei-ping, C., Zhi-Qi, Z., Ran, L., Meng, C., Wen-Jing, D., Wen-min, M., Xue, F., Xiao-Ming, W., and Ning, W. (2022) Source Tracing of Potentially Toxic Elements in Soils around a Typical Coking Plant in an Industrial Area in Northern China. Science of The Total Environment, Vol. 807, Part 2. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, PC and Swami A. (2007). Physiological Responses of Some Tree Species Under Roadside Automobile Pollution Stress Around City of Haridwar, India. Environmentalist; 27:365- 374.

- Juřík, R., and Braathen, N. A. (2021) Assessment of the Air Pollution Tax and Emission Concentration Limits in the Czech Republic. Environment Working Paper N° 174, OCED environment working papers are available at www.oecd.org/environment/workingpapers.htm.

- Kakoli, K., and Gupta, A.K. (2005). Seasonal Variations and Chemical Characterization of Ambient PM10 at Residential and Industrial Sites of an Urban Region of Kolkata, Calcutta., India, Journal of Atmospheric Research, Vol. 81, Issues 1, Pp.36-53. [CrossRef]

- Kaler, NS., Bhardwaj SK, Pant KS and Rai TS. (2016). Determination of Leaf Dust Accumulation on Certain Plant Species Grown Alongside National Highway 22, India. Current World Environment; 11.1.:77-82.

- Kanee, R.B., Ede, P.N., Adeyemi, A.J., Ojimah, C., Gobo, A.E., Edokpa, D.O., Owhonda, G., and Maduka, O. (2021). Perception of Port Harcourt Residents on Governments’ Interventions towards Air Quality: The Implication for Air Pollution Policy Accountability Framework, International Journal of Science and Research, IJSR. ISSN: 2319-7064, Vol. 10 Issue 2. [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F., Belis, C. A., Francisco, C., Dora, C., Prüss-ustün, A. M., Bonjour, S., Adair-Rohani, H., and Amann, M. (2015). Contributions to cities' ambient particulate matter, PM.: A Systematic Review of Local Source Contributions at Global Level. Atmospheric Environment, 120, 475–483. [CrossRef]

- Katarzyna, R., Grzegorz M. and Tomasz, R. (2014). Seasonal Variation of Air Pollution in Warsaw Conurbation, Journal of Meteorologische Zeitschrift, Vol. 23, No. 2, Pp.175–179.

- Kaza, N. (2020). Urban Form and Transportation Energy Consumption, Energy Policy, Vol. 136, No. 111049. [CrossRef]

- Kebe, M.; Traore, A.; Manousakas, M.I.; Vasilatou, V.; Ndao, A.S.; Wague, A.; and Eleftheriadis, K. (2021) Source Apportionment and Assessment of Air Quality Index of PM 2.5–10 and PM2.5 in at Two Different Sites in Urban Background Area in Senegal. Atmosphere, 12, 182. [CrossRef]

- Khaniabadi, Y.O., Polosa, R., Chuturkova, R.Z, Daryanoosh, S.M, Goudarzi, G, Borgini, A., Tittarelli, A., Basiri, H., Armin, H., Nourmoradi, H., Babaei, A.A., and Naserian, P. (2017). Air Pollution Health Impact Assessment on Total, Cardiovascular, and Respiratory Mortality in Khorramabad, Iran, the Air Approach., Journal of Process Safety and Environment Protection. [CrossRef]

- Ki-Hyun, K., Ehsanul K., and Shamin K. (2015). A Review on The Human Health Impact of Airborne Particulate Matter, Environment International 74, 136–143. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, T., Horvath, M., Csordas, A., Bator, G., and Toth-Bodrogi, E. (2020). Heliyon Tobacco Plant as Possible Biomonitoring Tool of Red Mud Dust Fallout and Increased Natural Radioactivity aria Horv. [CrossRef]

- Krewski, D. (2009). Evaluating the effects of ambient air pollution on life expectancy;360: 413–5.

- Kuang, X., Yuku W., Guang, W., Bin F., and Yuanyuan, Z. (2018). Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Air Pollutants .PM10, PM 2.5, SO2, NO2, O3, and CO. in the Inland Basin City of Chengdu, Southwest China. Journal of Atmosphere, Vol. 9, No. 74, Pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M., and Nandini, N. (2013). Identification and Evaluation of Air Pollution Tolerance Index of Selected Avenue Tree Species of Urban Bangalore India. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Computational and Applied Sciences; 13:388-390.

- Landrigan, P.J. (2017) Air Pollution and Health, Preventive Medicine and Global Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, Vol. 2, www.thelancet.com/public-health. [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.L., Smith, V.A. and Kahler, D.M. (2021). Pittsburgh Air Pollution Changes During the COVID-19 Lockdown, Environmental Advances. [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, F. and Rao, D.N. (1975). Effects of Air Pollutants on Lichen Bryophytes. In: Response of Air Pollution. Eds: J.B. Mudd and T. T. Kozlowski. Academic Press. New York, Pp. 237-272.

- Lelieveld, J, Evans JS, and Fnais M. (2015). The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature; 525:367–371.

- Londahl, J., Pagels J, Swietlicki E, Zhou JC, Ketzel M, and Massling A. (2006). A set-up for field studies of respiratory tract deposition of fine and ultrafine particles in humans. J Aerosol Sci;37.9:1152–63.

- Lorenzo, J. S. L., Tam, W. W. S., and Seow, W. J. (2021). Association between air quality, meteorological factors and COVID-19 infection case numbers, Environmental Research 197 .2021. 111024. [CrossRef]

- Manju, A., Kalaiselvi, K., Dhananjayan, V., Ravichandran, B., Palanivel, M., Banupriya, G.S., Vidhya, M.H., and Panjakumar, K. (2018). Spatio-seasonal Variation in Ambient Air Pollutants and Influence of Meteorological Factors in Coimbatore, Southern India. Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health. [CrossRef]

- Manochehrneya, S., Mohammadi, M., Esmaeili, R., and Vahdani, A. (2021). A time series approach to estimate the association between health effects, climate factors and air pollution, Mashhad, Iran, Iranian Journal of Health and Environment.

- Marinello, S., Butturi MA, and Gamberini R. (2021). How changes in human activities during the lockdown impacted air quality parameters: A review. Environ Prog Sustainable Energy, 40.4.: e13672. [CrossRef]

- Mashi, S.A., El-Ladan, I.Y., and Yaro, A. (2014) Atmospheric Contamination by Heavy Metals in Ilupeju Industrial Area of Lagos, International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Science, Vol. 3, No.2, Pp. 833-840.

- Mba, E. (2015). Problems and Prospects of Industrialization in Nigeria, infoguidenigeria.com.

- Mehmood, U., Azhar, A., Qayyum, F., Nawaz, H., Tariq, S., and Haq, Z. (2021). Air pollution and hospitalization in megacities: empirical evidence from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.L., Benney, T.M., Bares, R., Crosman, E.T. (2021). Intra-city variability of fine particulate matter during COVID-19 lockdown: A case study from Park City, Utah. Environmental Research 201 .2021. 111471. [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, D.J. (2005). Hedera helix L. J. Ecol. 93, 632e648. [CrossRef]

- Mir, QA., Yazdani T, Kumar A, Narain K, and Yunus M. (2008). Vehicular Population and Pigment Content of Certain Avenue Trees. Pollution Research; 27:59-63.

- Mirsanjari, M.M., Zarandian, A., Mohammadyari, F., and Visockiene, S.J. (2020). Investigation of the impacts of urban vegetation loss on the ecosystem service of air pollution mitigation in Karaj metropolis, Iran. Environ Monit Assess 192, 501. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. W. K., & Semple, J. L. (2021). Himalaya air quality impacts from the COVID-19 lockdown across the Indo-Gangetic Plain. GeoHealth, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, A.; Amegah, A.K.; Coker, E.S. (2022) Harmonization of Epidemiological Research Methods to Address the Environmental and Social Determinants of Urban Slum Health Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19, 11273. [CrossRef]

- Nabanita, G., Abhisek, R., Devdyuti, B., Nandini, D., Anupam, D., and Joyashree, R. (2020). COVID-19 Lockdown: Lessons Learnt Using Multiple Air Quality Monitoring Station Data from Kolkata City in India, Pp. 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S and Rajashree, V.B. (2017). Application of Wireless Sensor Networks in The Real Time Ambient Air Pollution Monitoring and Air Quality in Metropolitan Cities- A survey. 2017 International Conference on Smart Technology for Smart Nation, Pp. 1393-1398.

- National Bureau of Statistics Report, (2011) Population, Education, Economy, Health and Climate of Nigeria. Federal Republic of Nigeria, Pp.1 -698.

- National Population Census and Housing Census (2006) National Population Commission Bab Animashau, Surulere Lagos.

- Ninavenave, SY., Chaudhary PR, Gajghate DG, and Tarar JL. (2001). Foliar Biochemical Features of Plants as Indicators of Air Pollution. The Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; 67.1.:133-140.

- Njoku, K. L., Akinola M. O. and Zighadina T. M. (2013) A study on the spatial distribution of heavy metal in the industrial area of Ikorodu, Lagos State, Nigeria. Journal of Research in Environmental Science and Toxicology. ISSN: 2315-5698. Vol. 2. 3. pp.64-70, available online http://www.interesjournals.org/JREST.

- Nowak, D. J. (1994). Air pollution removal by Chicago’s urban forest,” In: Mc Pherson, E., Nowak, D.J., Rowntree, R.A, Eds, Results of the Chicago Urban Forest Climate Project, USDA Forest Service General Technical Report NE, Chicago’s Urban Forest Ecosystem, 186: 63–81.

- Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., Bodine, A., and Greenfield, E. (2014). Tree and Forest Effects on Air Quality and Human Health in The United States. Environmental Pollution, 193, 119e129.

- Nowak, D.J., Crane, D.E., Stevens, J.C. (2006). Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban For. Urban Green 4, 115–123.

- Nwachukwu, A. N., Chukwuocha E. O., and Igbudu O. (2012). A Survey on the Effects of Air Pollution on Diseases of the People of Rivers State, Nigeria. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology Vol. 6.10., pp. 371-379. http: //www. academicjournals.org/AJEST. [CrossRef]

- Obioh, I.B., Oluwole, A.F., Akeredolu, F.A., and Ogunsola, O. J. (1994). Inventory and Emission Projections in Relation to Various Transport Modes in Nigeria, 3rd International Symposium “Transport and Air Pollution” /3c Colloque Intern, 6th to 7th June Poster Proceedings/Actes posters 37, Bron, France.

- Odjugo, P. A. O. (2010) General Overview of Climate Change Impacts in Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology, Vol. 29, No. 1, Pp. 47-55.

- Offor, I. F., Adie, G. U., and Ana, G. R. E.E. (2016). Review of Particulate Matter and Elemental Composition of Aerosols at Selected Locations in Nigeria from 1985-2015.Journal of Health and Pollution Vol. 6, No. 10 Pp.1-18.

- Oghenetega, O. B., Ojengbede, O. A., Okunlola, M. A and Ana, GREE. (2021) Oil pollution and its impact on communities in the Niger Delta: a qualitative research approach; African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 50, No. 1.

- Ogolo, N.A., Ugwu, P., Ukut, I., Otokpa, M., and Onyekonwu, M. (2018) Rain Water Quality Evaluation in a Typical Gas Flaring Environment in the Niger Delta. Paper presented at the SPE Nigeria Annual International Conference and Exhibition, Lagos, Nigeria, August 2018, Paper Number: SPE-193398-MS. [CrossRef]

- Ogwu, F. A., Ajayi A.P., Aliyu, H. B., and Nuzhat, A. (2015) An Investigative Approach on the Effect of Air Pollution on Climate Change and Human Health in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology Vol. 2 No. 5; Pp.1-13.

- Ojekunle, Z. O., Jinadu O. O. E., Afolabi, T. A. and Taiwo, A. M. (2018) Environmental Pollution and Related Hazards at Agbara Industrial Area, Ogun State. Nature Scientific Report, Vol. 8, Issue 6482, www.nature.com/scientificreports. [CrossRef]

- Ojiodu, C. C. Okuo, J. M and Olumayede, E. G. (2013) Volatile organic compounds. VOCs. pollution in Iganmu industrial area, Lagos State, Southwestern – Nigeria. Scholarly Journals of Biotechnology Vol. 2.4., Pp. 43-49, http://www.scholarly-journals.com/SJB ISSN 2315-6171.

- Ojo, O.O. S. and Awokola, O.S. (2012) Investigation of Air Pollution from Automobiles at Intersections on Some Selected Major Roads in Ogbomosho, South Western, Nigeria. Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering Volume 1, Pp. 31-35, www.iosrjournals.org.

- Okolo, V.N., Olowolafe, E. A., Akawu, I., and Okoduwa, S.I.R. (2016) Effects of Industrial Effluents on Soil Resource in Challawa Industrial Area, Kano, Nigeria. Journal of Global Ecology and Environment 5.1.: 1-10, International Knowledge Press.

- Oksanen, E., and Kontunen-soppela, S. (2020). Plants have Different Strategies to Defend Against Air Pollutants, Current Opinion in Environmental Science and Health. [CrossRef]

- Olusola, J.A, Shote AA, Ouigmane A, and Isaifan RJ. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on nitrogen dioxide levels in Nigeria. PeerJ 9: e11387. [CrossRef]

- Oluwole, A.F., Akeredolu, F.A., Ogunsola, O.J., Obioh, I.B., Asubiojo, I.O., Baumbach, G., and Vogt, U. (1994). Measurement of Traffic Related Air Pollutants at Urban Location in Nigeria. 3rd International Symposium “Transport and Air Pollution” /3c Colloque Intern, 6th to 10th June 1994 Poster Proceedings/Actes posters 37, Bron, France.

- Oudin, A., Aström, D. O., Asplund, P., Steingrimsson, S., Szabo, Z., and Carlsen, H. K. (2018). The Association between Daily Concentrations of Air Pollution and Visits to a Psychiatric Emergency Unit: A Case-Crossover Study. Journal of Environmental Health, Vol. 17, Issue 4, Pp. 2-9. [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, A.R., Ouedraogo, J. R. P. Ouoba, S., Ozoh, O.B., Traoré, A.N., Sourabié, A., Boncoungou, K., Ouédraogo, G., Badoum, G., and Ouedraogo, M. (2021). Short-Term Effects of Ambient air Pollution on Pediatric Hospital Visits for Respiratory Diseases in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. [CrossRef]

- Oyebanji, F., Ana, G.R.E.E., Tope-Ajayi, O., Sadiq, A., and Mijinyawa, Y. (2021) Air Quality Indexing, Mapping and Principal Components Analysis of Ambient Air Pollutants around Farm Settlements across Ogun State, Nigeria. Applied Environmental Research 43.2., 93-105. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, J., and Sharma, A. K. (2020). A Review of Effects of Air Pollution on Physical and Biochemical Characteristics of Plants. 8.3., 1684–1688.

- Papazian, S., and Blande, J.D. (2018). Dynamics of Plant Responses to Combinations of Air Pollutants, Plant Biology, Review Article. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, V., Tripathi, B.D., and Mishra, V.K. (2008). Dynamics of traffic noise in a tropical city Varanasi and its abatement through vegetation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 146, 67–75.

- Paul, L. A., Burnett, R.T., Kwong, J.C. Hystad, P., Donkelaar, A., Bai, L., Goldberg, M. S., Lavigne, E., Copes, R. Martin, R. V., Kopp, A., and Chen, H. (2020). The Impact of Air Pollution on the Incidence of Diabetes and Survival among Prevalent Diabetes Cases. 134. [CrossRef]

- Popek, R., Gawro_nska, H., Wrochna, M., Gawronski, S.W., and Sæbø, A. (2013). Particulate Matter on Foliage of 13 Woody Species: Deposition on Surfaces and Phytostabilisation in Waxes - A 3-year Study. Int. J. Phytoremediation 15, 245e256. [CrossRef]

- Price Water Copper, (2015) Report on Lagos: City of Opportunities an Investor's Guide.

- Pu, H., Luo, K., Wang, P., Wang, S., and Kang, S. (2016) Spatial variation of air quality index and urban driving factors linkages: evidence from Chinese cities. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.A.M., MacKenzie, A.R., Whyatt, J.D., Hewitt, C.N. (2012). Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure for Improvement of Air Quality in Urban Street Canyons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 7692e7699. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.,Yang, L., Xixi, F., Pan, M., Ang, S., Mingya, W., and Mingshi, W. (2021) Pollution Effect Assessment of Industrial Activities on Potentially Toxic Metal Distribution in Windowsill Dust and Surface Soil in Central China. Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 759, 144023. [CrossRef]

- Rai, PK., and Panda LLS. (2014). Leaf Dust Deposition and Its Impact on Biochemical Aspect of Some Roadside Plants of Aizawl, Mizoram. International Research Journal of Environment Science; 3.11.:14-19.

- Ramanathan, V.; Crutzen, P. J.; Kiehl, J.T.; Rosenfeld, D. (2001). Aerosols Science, 294, 2119-2124.

- Ranjan, O.; Menon J.S; and Nagendra, S.M.S. (2016). Assessment of Air Quality Impacts on Human Health and Vegetation at an Industrial Area. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste, Vol. 20, Issue 4. [CrossRef]

- Requia, W. J., and Koutrakis, P. (2018). Mapping distance-decay of premature mortality attributable to PM2.5 - related traffic congestion. Environmental Pollution, 243, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Richards, D. R., Fung T. K., Belcher, R. N., and Edwards P. J. (2020). Differential Air Temperature Cooling Performance of Urban Vegetation Types in The Tropics, Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, Vol. 50, 126651. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Alvarez, A. (2021) Air pollution and life expectancy in Europe: Does investment in renewable energy matter? Science of the Total Environment 792. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C. D. (2017) How Do Factories Pollute the Air, livestrong.com.

- Roy, A., Bhattacharya, T., and Kumari, M. (2020). Air pollution tolerance, metal accumulation and dust capturing capacity of common tropical trees in commercial and industrial sites. Science of the Total Environment, 722. [CrossRef]

- Saadat, M.N., Das, S., Nandy, S., Pandey, D., Chakraborty, M., Mina, U., and Sarkar, A. (2021). Can the nation-wide COVID-19 lockdown help India identify region-specific strategies for air pollution? Spat. Inf. Res. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R., Taneja, A., and Singh, P. (2017). Surface ozone scenario and air quality in the north-central part of India. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 59, 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Salau, O. R. (2016) The Changes in Temperature and Relative Humidity in Lagos State, Nigeria. World Scientific News, Vol. 49, No. 2, Pp. 295-306, available at worldscientificnews.com.

- Salvador, S., and Salvador, E. (2012) Air Quality Communication Workshop https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-05/documents/zell-aqi.pdf.

- Samek, L., Stegowski, Z., and Furman, L. (2017). Quantitative Assessment of PM2.5 Sources and Their Seasonal Variation in Krakow. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Triana, E., Enriquez, S., Afzal, J., Nakagawa, A., and Khan, A. S. (2014). Cleaning Pakistan’s Air- Policy Options to Address the Cost of Outdoor Air Pollution. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. [CrossRef]

- Saud, B., and Paudel, G. (2018). The Threat of Ambient Air Pollution in Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Senaul, H. and Singh, R.B. (2017). Air Pollution and Human Health in Kolkata, India: Department of Geography, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, Delhi 110007.

- She, Q., Peng, X., Xu, Q., Long, L., Wei, N., Liu, M., and Jia, W. (2017). Air quality and its response to satellite-derived urban form in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Ecological Indicators, 75, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, K., Xiaoxing, L., Ahmad, M., Majeed, A., Tariq, F., and Wahab, S. (2021). Does air pollution upsurge in megacities after Covid-19 lockdown? A spatial approach, Environmental Research 197. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. (2020). Impact of Air Pollutants on Plant Metabolism and Antioxidant Machinery. In: Saxena P., Srivastava A., eds. Air Pollution and Environmental Health. Environmental Chemistry for a Sustainable World, Vol 20. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B., Das, U. C., Prasad, B.B. and Jha, S.K. (2002). Monitoring of dust pollution by leaves,”Pollution Research 21: 13 – 16.

- Siti, N. F. A, Azimah, I., Hafizan, J., Badlishah, A., Fathurrahman, L., Noor, M. H., Nadiana, A., Munirah, A. Z., Tengku, A. T. M., Hafriz, F. H., Raja, I. S. R. M., Jef, R. A. J., and Safari, M.D. (2022) Chemical composition of rainwater harvested in East Malaysia. Environ. Eng. Res. 2022 Research Article. [CrossRef]

- Siudek, P. (2018). Total Carbon and Benzo, A. Pyrene in Particulate Matter Over a Polish Urban Site – A Combined Effect of Major Anthropogenic Sources and Air Mass Transport. Journal of Atmospheric Pollution Research. Science Direct., Vol. 9, Issue 4, Pp. 764-773. [CrossRef]

- Sokan-Adeaga, A.A. and Ana, GR.E.E. (2015) A comprehensive review of biomass resources and biofuel production in Nigeria: potential and prospects; Journal Reviews on Environmental Health; De Gruyter. [CrossRef]

- South West Investment Exhibition and Summit, (2017) Report, Fodion Consultants.

- Srimuruganandam, B, and Nagendra S. (2012). Source characterization of PM10 and PM2.5 mass using a chemical mass balance model at urban roadside. Sci Total Environ; 433:8–19.

- State of Global Air, (2018). The Health Effects Institute. HEI, www.stateofglobalair.org.

- Sternberg, T., Viles, H., Cathersides, A., and Edwards, M. (2010). Dust Particulate Absorption by Ivy. Hedera helix L. on Historic Walls in Urban Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 162e168. [CrossRef]

- Subramani, S, and Devaanandan, S. (2015). Application of Air Pollution Tolerance Index in Assessing the Air Quality. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; 7.7.:216-221.

- Surinder, D. and Verma, V. (2016). Annual and Seasonal Variations in Air Quality Index of The National Capital Region, India. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. International Journal of Environmental and Ecological Engineering Vol. 10, No. 10, Pp. 1-6.

- Swami, A. and Chauhan, D. (2015). Impact of Air Pollution Induced by Automobile Exhaust Pollution on Air Pollution Tolerance Index on Few Species of Plants. International Journal of Scientific Research; 4.3.:342-343.

- Taiwo, A.M, Arowolo T.A., Abdullahi K.L. and Taiwo O.T. (2015). Particulate Matter Pollution in Nigeria, A Review, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology Rhodes, Greece, 3-5.

- Tao, Y., Zhang, Z., Ou, W., Guo, J., and Pueppke, S.G. (2020). How Does Urban Form Influence PM2.5 Concentrations: Insights From 350 Different-Sized Cities in The Rapidly Urbanizing Yangtze River Delta Region of China, 1998–2015, Vol. 98, 102581. [CrossRef]

- Tawari, C.C and Abowei, J.F.N. (2012) Air Pollution in the Niger Delta Area of Nigeria. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Vol.1, No.2, Pp.94-117.

- Thakur, A. (2017). Study of Ambient Air Quality Trends and Analysis of Contributing Factors in Study of Ambient Air Quality Trends and Analysis of Contributing Factors in Bengaluru, India. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. N.; Tran, N. B.; Tran, H. M. T.; Tang, H. K.; Ngo, X. M.; Godin, I.; Michel, O.; and Bouland, C. (2020). Influence of type of dwelling on the prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Vol.24, No. 3, Pp. 316-320.5. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K and Gautam, M. (2007). Biochemical Parameters of Plants as Indicators of Air Pollution. Journal of Environmental Biology; 28.1:127-132.

- Uka, U. N., Hogarh, J., and Belford, E. J. D. (2017). Morpho-Anatomical and Biochemical Responses of Plants to Air Pollution. 7.1., 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Umoh, V., Peters, E., Erhabor, G., Ekpe, E., and Ibok, A. (2013) Indoor Air pollution and Respiratory Symptoms among Fishermen in the Niger delta of Nigeria, African Journal of Respiratory Medicine, Vol. 9 No. 1. Pp.1-5.

- Umoh, V., Peters, E., Erhabor, G., Ekpe, E., and Ibok, A. (2013). Indoor Air pollution and Respiratory Symptoms among Fishermen in the Niger delta of Nigeria, African Journal of Respiratory Medicine, Vol. 9 No. 1. Pp.1-5.

- UNEP (2016). The Emissions Gap Report United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP., Nairobi.

- Valavanidis, A, Fiotakis K, Vlachogianni, T. (2008). Airborne particulate matter and human health: toxicological assessment and importance of size and composition of particles for oxidative damage and carcinogenic mechanisms. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev; 26.4.:339–62.

- Wagh, N. D., Shukla, P. V, and Ingle, S. T. (2006). Biological monitoring of roadside plants exposed to vehicular pollution in Jalgaon city Biological monitoring of roadside plants exposed to vehicular pollution in Jalgaon city. Journal of Environmental Biology, 27.2.419-421.

- Wang, B., Sun, S., and Duan, M. (2015). Impacts of Building Form on The Wake Flow Wind Potential. Energy Procedia, 153, 383-388.

- Wei, C., Lei Y., and Haimeng, Z. (2015). Seasonal Variations of Atmospheric Pollution and Air Quality in Beijing.

- WeiJian, L., YunSong X., WenXin L., QingYang L., ShuangYu, Y., Yang L., Xin W., and Shu T. (2018). Oxidative Potential of Ambient PM2.5 in the Coastal Cities of the Bohai Sea, Northern China: Seasonal Variation and Source Apportionment. Environmental Pollution 236, 514-528. [CrossRef]

- Weli, V. E and Adegoke, J. O. (2016) the Influence of Meteorological Parameters and Land use on the Seasonal Concentration of Carbon Monoxide CO, in the Industrial Coastal City of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Journal of Pollution Effluent Control Vol.4, Pp. 171. [CrossRef]

- Weli, V. E. (2014). Spatial and Seasonal Variations in Atmospheric Pollutants Concentrations in Port Harcourt Nigeria. PhD Thesis. Department of Geography, Faculty of Science, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

- West, J. J., Cohen, A. Dentener, F., Brunekreef, B. Zhu, T., Armstrong, B., Bell, M.L, Brauer, M., Carmichael, G., Costa, D.L, Dockery, D. W., Kleeman, M., Krzyzanowski, M., Künzli, N. C., Lung, S.C, Randall V. M, Pöschl, U., Arden C., P, Roberts, J.M, Russell, A.G and Wiedinmyer, C. (2016) What We Breathe Impacts Our Health: Improving Understanding of the Link between Air Pollution and Health. Environ. Sci. Technol., Vol. 50, No. 10, Pp. 4895–4904. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2021) Global Air Quality Guidelines. Particulate matter .PM2.5 and PM10., ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. Geneva: World Health Organization .CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo.

- Witters, K., Plusquin, M., Slenders, E., Aslam, I., and Ameloot, M. (2020). Monitoring Indoor Exposure to Combustion-Derived Particles Using. 266. [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group (2016) The Cost of Air Pollution, Strengthening the Economic Case for Action, English, Washington, D.C: Working Paper, 108141. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/781521473177013155/ The-cost-of-air-pollution-strengthening-the-economic-case-for-action.

- World Health Organization (2016) Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease.

- World Health Organization (2018) CCAC Report, http://www.who.int/airpollution/data/household-energy-database/en/.

- World Health Organization Report (2010) Preventing Disease through Healthy Environments, Exposure to Air Pollution, A Major Public Health Concern.

- Xianghua, W. (2010). Industrial Pollution, Point Sources of Pollution: Local Effects and its Control, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, EOLSS., Vol. I. Beijing, China.

- Xiaoguo, W., Yueyue, D., Shoubiao, Z., and Ye, T. (2018). Temporal Characteristic and Source Analysis of PM 2.5 in the Most Polluted City Agglomeration of China, Journal of Research, Turkish National Committee for Air Pollution Research and Control, Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.

- Xiaolin, X., Zhang, A., Liang, S., Qingwen, Qi, Jiang, L., and Yanjun, Ye. (2017). The Association between Air Pollution and Population Health Risk for Respiratory Infection: A Case Study of Shenzhen, China, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, Vol.14, and Pp.950. [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Jun, X.; Xiao-Hui D.; QianQian, G., RuiQing, Z., Jun, T., BoFeng, C., LongFei, W., Ma FangShu, M., and BeiHai, Z. (2017). Impacts Assessment of Steel Plants on Air Quality over Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Area, China Environmental Science 2017 Vol. 37, No.5 pp.1684-1692.

- Xing L; Zhi G; Hub J; Hua C; and Xing, X. (2022) The impact of environmental accountability on air pollution: A public attention perspective; Energy Policy, Vol. 161, 112733. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Fu, Q., Guo, X., and Wang, Y. (2015). Concentrations and Seasonal Variation of Ambient PM2.5 and Associated Metals at a Typical Residential Area in Beijing, 232–239. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Shi, B., Shi, Y., Marvin, S., Zheng, Y., and Xia, G. (2019). Air Pollution Dispersal in High Density Urban Areas: Research on the Triadic Relation of Wind, Air Pollution, and Urban Form. Sustainable Cities and Society, 101941. [CrossRef]

- Yan-ju, L and Hui, D. (2008). Variation in air pollution tolerance index of plant near a steel factory: implications for landscape plant species selection for industrial areas. Environment, Development; 1:24-30.

- Yusuf, M. A., and Abiye, T. A. (2019) Groundwater for Sustainable Development Risks of groundwater pollution in the coastal areas of Lagos, South Western Nigeria. Groundwater for Sustainable Development, 100222. https://doi.org /10.1016/ j.gsd.2019.100222.

- Zagha, O. and Nwaogazie, I. L. (2015) Roadside Air Pollution Assessment in Port-Harcourt, Nigeria, Standard Scientific Research and Essays Vol. 3, No. 3: Pp.066-074.ISSN: 2310-7502 http://www.standresjournals.org/journals/SSRE.

- Zhang, Y., Ding, A., Mao, H., Nie, W., and Zhou, D. (2015). Impact of synoptic weather patterns and inter-decadal climate variability on air quality in the North China Plain during 1980 e 2013. Atmospheric Environment, 1–10. [CrossRef]

| ANOVA | ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| SO2 | Between Groups | 47.897 | 11 | 4.354 | 5.103 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 92.157 | 108 | .853 | |||

| Total | 140.054 | 119 | ||||

| NO2 | Between Groups | 110.649 | 11 | 10.059 | 8.805 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 123.388 | 108 | 1.142 | |||

| Total | 234.036 | 119 | ||||

| CO | Between Groups | 341.300 | 11 | 31.027 | 1.320 | .223 |

| Within Groups | 2538.233 | 108 | 23.502 | |||

| Total | 2879.533 | 119 | ||||

| PM2.5 | Between Groups | 44891.032 | 11 | 4081.003 | 3.897 | .000 |

| Within Groups | 113088.662 | 108 | 1047.117 | |||

| Total | 157979.695 | 119 | ||||

| t-test for Equality of Means | ||||||||

| t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| SO2 Season | Equal variances assumed | 3.013 | 18 | .007 | 1.14500 | .38006 | .34652 | 1.94348 |

| NO2 Season | Equal variances assumed | 4.042 | 18 | .001 | 1.65200 | .40866 | .79344 | 2.51056 |

| CO Season | Equal variances assumed | 1.432 | 18 | .169 | 3.00300 | 2.09720 | -1.40304 | 7.40904 |

| PM2.5 Season | Equal variances assumed | 2.798 | 18 | .012 | 36.91900 | 13.19497 | 9.19741 | 64.64059 |

| Predictors | β | t | ρ- value | Results |

| SO2 | 140.13 | .309 | .763 | Not supported |

| NO2 | -303.07 | -.929 | .373 | Not supported |

| CO | 217.83 | 2.568 | .026* | Supported |

| PM2.5 | -2.577 | -.293 | .775 | Not supported |

| Temperature | -318.47 | -1.629 | .132 | Not supported |

| Relative Humidity | -11.308 | -2.220 | .048* | Supported |

| Precipitation | 65.217 | 1.478 | .167 | Not supported |

| Wind Speed | 33.584 | .186 | .856 | Not supported |

| ANOVA | F (8,11) | 3.652 | 0.025* | |

| R2 | 0.726 |

| Predictors | β | t | ρ- value* | Results |

| SO2 | 25.777 | 1.049 | .297 | Not supported |

| NO2 | -48.874 | -2.835 | .005* | Supported |

| CO | 6.045 | 1.627 | .107 | Not supported |

| PM2.5 | 1.361 | 2.998 | .003* | Supported |

| Temperature | 7.036 | 1.128 | .262 | Not supported |

| Relative Humidity | 6.214 | 4.359 | .000* | Supported |

| Precipitation | -.082 | -.730 | .467 | Not supported |

| Wind Speed | -21.379 | -2.384 | .019* | Supported |

| ANOVA | F (8,111) | 8.315 | 0.000* | |

| R2 | 0.375 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).