Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Datasets Overview

Cluster Analysis

Gene Expression Analysis

Results

Part 1: Cluster Analysis

Diversity in GRID2 and CCDC26 Expression Between Clusters

GPNMB/IQGAP2+ Phagocytic Microglia

Ribosome-Enriched FTL/H1+ C1QA/B/C+ Microglia (REM-FT/C1Q)

Mitochondrial Genes Expressing Microglia (Mito-Microglia)

HSP Genes Expressing Microglia (HSP-Microglia)

Dividing Microglia

NRG3+ and ST18+ Microglia

SPP1, TMEM163, and Other Activation-Related Genes

Results from the Monkey Aging Dataset

Part 2: Gene Expression Analysis

Pseudobulk Results

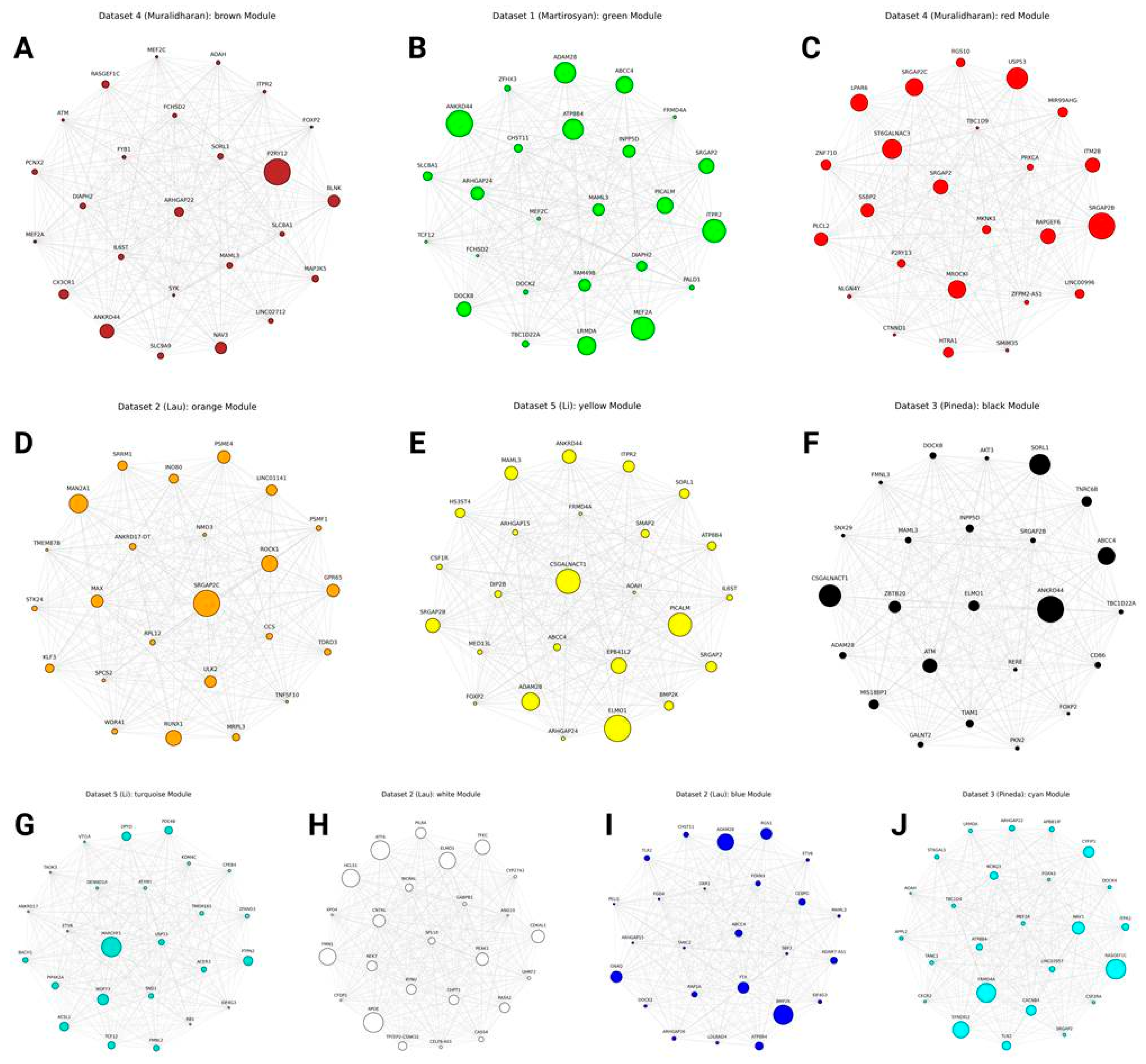

hdWGCNA Results

Translational Modules

Other Cluster-Specific and Activation-Related Modules

Other Highly Reproducible Genes

Monkey Modules

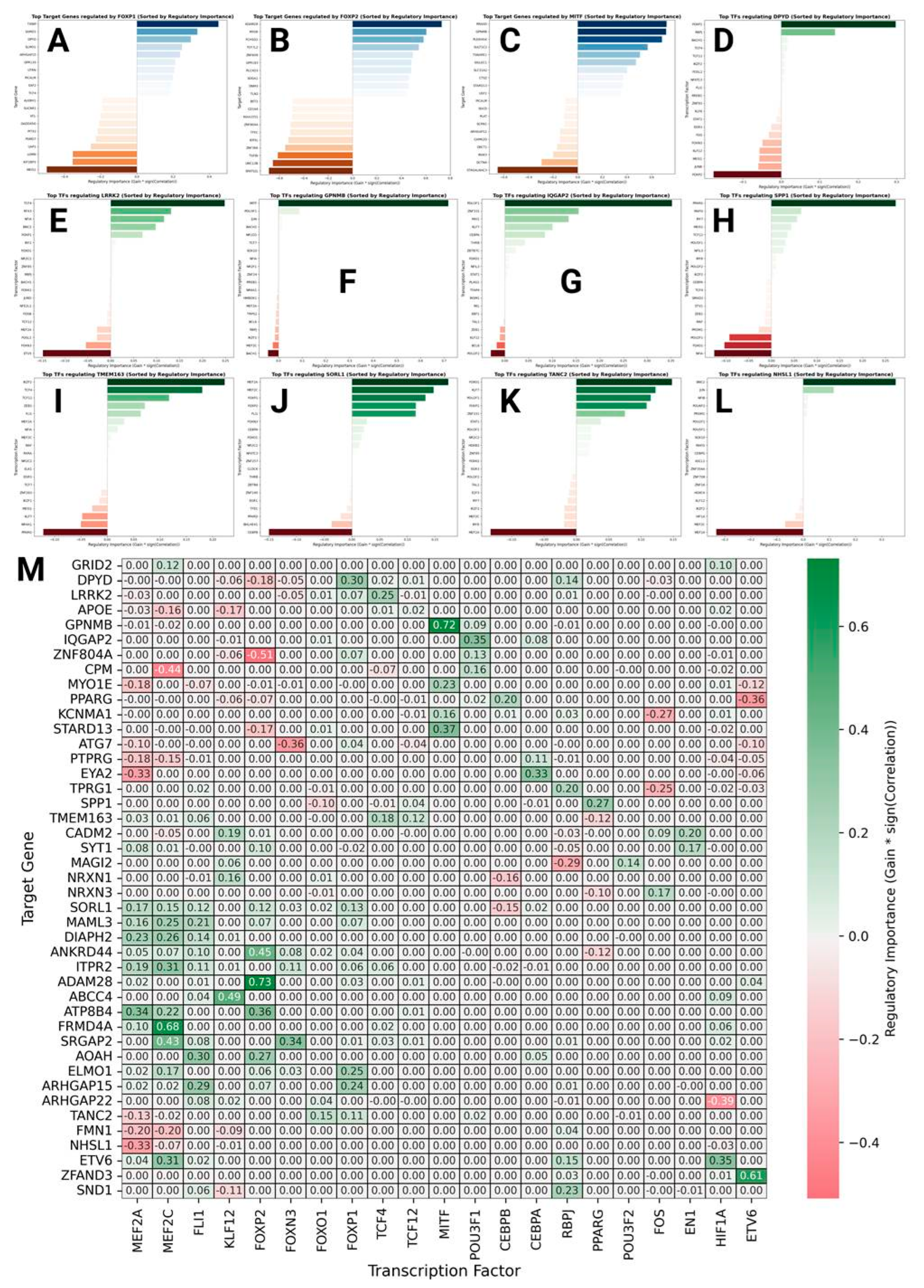

Transcriptional Factor Analysis

Discussion

ST18+ and NRG3+ Microglia: Artifact or Biology?

A Brief Inference About Key Genes Regulating Microglia Phenotypes

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Hou, Yujun, Xiuli Dan, Mansi Babbar, Yong Wei, Steen G. Hasselbalch, Deborah L. Croteau, and Vilhelm A. Bohr. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nature reviews neurology 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, David M. , Mark R. Cookson, Ludo Van Den Bosch, Henrik Zetterberg, David M. Holtzman, and Ilse Dewachter. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell 2023, 186, 693–714. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Chao, Jingwen Jiang, Yuyan Tan, and Shengdi Chen. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deczkowska, Aleksandra, Hadas Keren-Shaul, Assaf Weiner, Marco Colonna, Michal Schwartz, and Ido Amit. Disease-associated microglia: a universal immune sensor of neurodegeneration. Cell 2018, 173, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Yingyue, Wilbur M. Song, Prabhakar S. Andhey, Amanda Swain, Tyler Levy, Kelly R. Miller, Pietro L. Poliani et al. Human and mouse single-nucleus transcriptomics reveal TREM2-dependent and TREM2-independent cellular responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature medicine 2020, 26, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, Jun-ichi, Yoshihiro Kino, Motoaki Yanaizu, Tsuyoshi Ishida, and Yuko Saito. Microglia express GPNMB in the brains of Alzheimer's disease and Nasu-Hakola disease. Intractable & Rare Diseases Research 2019, 8, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, Marina, Giovanna Araujo de Souza, Cristoforo Scavone, and Paula Fernanda Kinoshita. The role of GPNMB in inflammation. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 674739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Mei, Jianping Zhu, Jiawei Zheng, Xuan Han, Lijuan Jiang, Xiangzhen Tong, Yue Ke et al. GPNMB and ATP6V1A interact to mediate microglia phagocytosis of multiple types of pathological particles. Cell Reports 44, (2025).

- Sun, Na, Matheus B. Victor, Yongjin P. Park, Xushen Xiong, Aine Ni Scannail, Noelle Leary, Shaniah Prosper et al. Human microglial state dynamics in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell 2023, 186, 4386–4403. [Google Scholar]

- Prater, Katherine E. , Kevin J. Green, Sainath Mamde, Wei Sun, Alexandra Cochoit, Carole L. Smith, Kenneth L. Chiou et al. Human microglia show unique transcriptional changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Aging 2023, 3, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins-Ferreira, Ricardo, Josep Calafell-Segura, Bárbara Leal, Javier Rodríguez-Ubreva, Elena Martínez-Saez, Elisabetta Mereu, Paulo Pinho E Costa, Ariadna Laguna, and Esteban Ballestar. The Human Microglia Atlas (HuMicA) unravels changes in disease-associated microglia subsets across neurodegenerative conditions. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, Araks, Rizwan Ansari, Francisco Pestana, Katja Hebestreit, Hayk Gasparyan, Razmik Aleksanyan, Silvia Hnatova et al. Unravelling cell type-specific responses to Parkinson’s Disease at single cell resolution. Molecular neurodegeneration 2024, 19, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Shun-Fat, Han Cao, Amy KY Fu, and Nancy Y. Ip. Single-nucleus transcriptome analysis reveals dysregulation of angiogenic endothelial cells and neuroprotective glia in Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 25800–25809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, S. Sebastian, Hyeseung Lee, Maria J. Ulloa-Navas, Raleigh M. Linville, Francisco J. Garcia, Kyriakitsa Galani, Erica Engelberg-Cook et al. Single-cell dissection of the human motor and prefrontal cortices in ALS and FTLD. Cell 2024, 187, 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, Chandramouli, Enikő Zakar-Polyák, Anita Adami, Anna A. Abbas, Yogita Sharma, Raquel Garza, Jenny G. Johansson et al. Human Brain Cell-Type-Specific Aging Clocks Based on Single-Nuclei Transcriptomics. Advanced Science 2025, e06109.

- Li, Zonghua, Yuka A. Martens, Yingxue Ren, Yunjung Jin, Hiroaki Sekiya, Sydney V. Doss, Naomi Kouri et al. APOE genotype determines cell-type-specific pathological landscape of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2025, 113, 1380–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Hui, Jiaming Li, Jie Ren, Shuhui Sun, Shuai Ma, Weiqi Zhang, Yang Yu et al. Single-nucleus transcriptomic landscape of primate hippocampal aging. Protein & Cell 2021, 12, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F. Alexander, Philipp Angerer, and Fabian J. Theis. SCANPY: large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome biology 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolock, Samuel L. , Romain Lopez, and Allon M. Klein. Scrublet: computational identification of cell doublets in single-cell transcriptomic data. Cell systems 2019, 8, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Conde, C. , Chao Xu, Louie B. Jarvis, Daniel B. Rainbow, Sara B. Wells, Tamir Gomes, S. K. Howlett et al. Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Science 2022, 376, eabl5197. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Chuan, Martin Prete, Simone Webb, Laura Jardine, Benjamin J. Stewart, Regina Hoo, Peng He, Kerstin B. Meyer, and Sarah A. Teichmann. Automatic cell-type harmonization and integration across Human Cell Atlas datasets. Cell 2023, 186, 5876–5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafemeister, Christoph, and Rahul Satija. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome biology 2019, 20, 296. [Google Scholar]

- Polański, Krzysztof, Matthew D. Young, Zhichao Miao, Kerstin B. Meyer, Sarah A. Teichmann, and Jong-Eun Park. BBKNN: fast batch alignment of single cell transcriptomes. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 964–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traag, Vincent A. , Ludo Waltman, and Nees Jan Van Eck. From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, Leland, John Healy, and James Melville. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1802.03426.

- Wu, Tianzhi, Erqiang Hu, Shuangbin Xu, Meijun Chen, Pingfan Guo, Zehan Dai, Tingze Feng et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. The innovation 2021, 2.

- Benjamini, Yoav, and Yosef Hochberg. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzellec, Boris, Maria Teleńczuk, Vincent Cabeli, and Mathieu Andreux. PyDESeq2: a python package for bulk RNA-seq differential expression analysis. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad547. [Google Scholar]

- Morabito, Samuel, Fairlie Reese, Negin Rahimzadeh, Emily Miyoshi, and Vivek Swarup. hdWGCNA identifies co-expression networks in high-dimensional transcriptomics data. Cell reports methods 2023, 3.

- Childs, Jessica E., Samuel Morabito, Sudeshna Das, Caterina Santelli, Victoria Pham, Kelly Kusche, Vanessa Alizo Vera et al. Relapse to cocaine seeking is regulated by medial habenula NR4A2/NURR1 in mice. Cell reports 43, (2024).

- Huang, Shengzhu, Chenqi Zhang, Xing Xie, Yuanyuan Zhu, Qiong Song, Li Ye, and Yanling Hu. GRID2 aberration leads to disturbance in neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions via changes to the species richness and composition of gut microbes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2022, 631, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet-der Garabedian, Béatrice, Paul Derer, Yannick Bailly, and Jean Mariani. Innate immunity in the Grid2 Lc/+ mouse model of cerebellar neurodegeneration: glial CD95/CD95L plays a non-apoptotic role in persistent neuron loss-associated inflammatory reactions in the cerebellum. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrits, Emma, Nieske Brouwer, Susanne M. Kooistra, Maya E. Woodbury, Yannick Vermeiren, Mirjam Lambourne, Jan Mulder et al. Distinct amyloid-β and tau-associated microglia profiles in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica 2021, 141, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Yuka, Atsuhiko Ishida, Hironori Harada, and Tetsuo Hirano. Long Noncoding RNA CCDC26 Interacts With Vimentin, HNRNPC, CBX1, and CBX5 Proteins in Multiple Intracellular Compartments of Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Genes to Cells 2025, 30, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, Christiana C. , Anna Onisiforou, Panos Zanos, and Eleni Zamba Papanicolaou. Unraveling the transcriptomic signatures of Parkinson’s disease and major depression using single-cell and bulk data. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2023, 15, 1273855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuron23. Neuron23. Accessed , 2025. https://neuron23.com/neuron23-announces-96-5-million-series-d-financing-and-first-patient-dosed-in-global-phase-2-neulark-clinical%20-trial-of-neu-411-for-early-parkinsons-disease/. 28 October.

- Gutknecht, Michael, Julian Geiger, Simone Joas, Daniela Dörfel, Helmut R. Salih, Martin R. Müller, Frank Grünebach, and Susanne M. Rittig. The transcription factor MITF is a critical regulator of GPNMB expression in dendritic cells. Cell Communication and Signaling 2015, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, Lucas, Dmitry Velmeshev, Staffan Holmqvist, Max Kaufmann, Sebastian Werneburg, Diane Jung, Stephanie Vistnes et al. Neuronal vulnerability and multilineage diversity in multiple sclerosis. Nature 2019, 573, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, Sook-Yoong, Mengwei Li, Zhihong Li, Haitao Tu, Jolene Wei Ling Lee, Lifeng Qiu, Jingjing Ling et al. Single-nucleus transcriptomics reveals a distinct microglial state and increased MSR1-mediated phagocytosis as common features across dementia subtypes. Genome medicine 2025, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xinyue, Yin Huang, Liangfeng Huang, Ziliang Huang, Zhao-Zhe Hao, Lahong Xu, Nana Xu et al. A brain cell atlas integrating single-cell transcriptomes across human brain regions. Nature medicine 2024, 30, 2679–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jiaojiao, Maoxiang Xu, Boyu Cai, Xiangyu Li, Zhanping Liang, Xiaohuan Xia, Haitao Zhang, Zhiwen Zhang, Fei Tan, and Jialin Charlie Zheng. Clinically Inspired Multimodal Treatment Using Induced Neural Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Promotes Recovery of Traumatic Brain Injury through Microglial Modulation. Advanced Science 2025, e08574.

- Zang, Dongdong, Zilong Dong, Yuecheng Liu, and Qian Chen. Single-cell RNA sequencing of anaplastic ependymoma and H3K27M-mutant diffuse midline glioma. BMC neurology 2024, 24, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Bhavina B. , Karan Rai, Heather Blunt, Wenyan Zhao, Tor D. Tosteson, and Gabriel A. Brooks. Pathogenic DPYD variants and treatment-related mortality in patients receiving fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Oncologist 2021, 26, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- “Teysuno | European Medicines Agency (EMA),” , 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/teysuno. 7 March.

- Guvenek, Aysegul, Neelroop Parikshak, Daria Zamolodchikov, Sahar Gelfman, Arden Moscati, Lee Dobbyn, Eli Stahl, Alan Shuldiner, and Giovanni Coppola. Transcriptional profiling in microglia across physiological and pathological states identifies a transcriptional module associated with neurodegeneration. Communications Biology 2024, 7, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Meng, Xiwen Ma, Xiaochuan Wang, and Jianping Ye. Microglial APOE4 promotes neuron degeneration in Alzheimer's disease through inhibition of lipid droplet autophagy. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. B 2024, 15, 657. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Yangning, Xiaoxuan Zhang, Shaorui Liu, Chen Guo, Yuxiao Jin, Hui Li, Linyixiao Wang et al. Fate mapping of Spp1 expression reveals age-dependent plasticity of disease-associated microglia-like cells after brain injury. Immunity 2024, 57, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Shizhen, Mang Hu, and Zhongtao Wei. Single-cell sequencing reveals an important role of SPP1 and microglial activation in age-related macular degeneration. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2024, 17, 1322451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Jun, Hong Wu, Cheng Xie, Yangyan He, Rong Mou, Hongkun Zhang, Yan Yang, and Qingbo Xu. Single-cell mapping of large and small arteries during hypertensive aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2024, 79, glad188. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ling, Soochi Kim, Matthew T. Buckley, Jaime M. Reyes, Jengmin Kang, Lei Tian, Mingqiang Wang et al. Exercise reprograms the inflammatory landscape of multiple stem cell compartments during mammalian aging. Cell stem cell 2023, 30, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, John D. , Dakota B. Poschel, Chunwan Lu, Alyssa D. Merting, Dafeng Yang, Priscilla S. Redd, and Kebin Liu. Osteopontin blockade immunotherapy increases cytotoxic T lymphocyte lytic activity and suppresses colon tumor progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styrpejko, Daniel J. , and Math P. Cuajungco. Transmembrane 163 (TMEM163) protein: a new member of the zinc efflux transporter family. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Do Rosario, Michelle C. , Guillermo Rodriguez Bey, Bruce Nmezi, Fang Liu, Talia Oranburg, Ana SA Cohen, Keith A. Coffman et al. Variants in the zinc transporter TMEM163 cause a hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Brain 2022, 145, 4202–4209. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzentruber, Jeremy, Sarah Cooper, Jimmy Z. Liu, Inigo Barrio-Hernandez, Erica Bello, Natsuhiko Kumasaka, Adam MH Young et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis, fine-mapping and integrative prioritization implicate new Alzheimer’s disease risk genes. Nature genetics 2021, 53, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brase, Logan, Shih-Feng You, Ricardo D’Oliveira Albanus, Jorge L. Del-Aguila, Yaoyi Dai, Brenna C. Novotny, Carolina Soriano-Tarraga et al. Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing of autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease and risk variant carriers. Nature communications 2023, 14, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Donghoon, James M. Vicari, Christian Porras, Collin Spencer, Milos Pjanic, Xinyi Wang, Seon Kinrot et al. Plasticity of human microglia and brain perivascular macrophages in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. medRxiv 2024.

- Kim, Hyojin, Noah C. Berens, Nicole E. Ochandarena, and Benjamin D. Philpot. Region and cell type distribution of TCF4 in the postnatal mouse brain. Frontiers in neuroanatomy 2020, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, Andrew J. , Elizabeth J. Rahn, Brynna S. Paulukaitis, Katherine E. Savell, Holly B. Kordasiewicz, Jing Wang, John W. Lewis et al. Tcf4 regulates synaptic plasticity, DNA methylation, and memory function. Cell reports 2016, 16, 2666–2685. [Google Scholar]

- Shariq, Mohammad, Vinaya Sahasrabuddhe, Sreevatsan Krishna, Swathi Radha, null Nruthyathi, Ravishankara Bellampalli, Anukriti Dwivedi et al. Adult neural stem cells have latent inflammatory potential that is kept suppressed by Tcf4 to facilitate adult neurogenesis. Science Advances 2021, 7, eabf5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vikram P. , Aimée L. Fenwick, Mia S. Brockop, Simon J. McGowan, Jacqueline AC Goos, A. Jeannette M. Hoogeboom, Angela F. Brady et al. Mutations of TCF12, encoding a basic-helix-loop-helix partner of TWIST1, are a frequent cause of coronal craniosynostosis. The Lancet 2013, 381, S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chuankun, Ruichun Li, Yuan Wang, and Haitao Jiang. Inhibition of the TCF12/VSIG4 axis by palbociclib diminishes the proliferation and migration of glioma cells and decreases the M2 polarization of glioma-associated microglia. Drug Development Research 2024, 85, e22230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Bin, Kristina Becanovic, Paula A. Desplats, Brian Spencer, Austin M. Hill, Colum Connolly, Eliezer Masliah, Blair R. Leavitt, and Elizabeth A. Thomas. Forkhead box protein p1 is a transcriptional repressor of immune signaling in the CNS: implications for transcriptional dysregulation in Huntington disease. Human molecular genetics 2012, 21, 3097–3111. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Xiaofeng, Shuiyue Quan, Wenping Liang, Yu Li, Huimin Cai, Ziye Ren, Yinghao Xu, Zhe Wang, and Longfei Jia. FOXP1 is a Transcription Factor for the Alzheimer's Disease Risk Gene SORL1. Journal of Neurochemistry 2025, 169, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, Irene, Andre Palmeira, Ester Aso, Margarita Carmona, Liana Fernandez, and Isidro Ferrer. FOXP2 expression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration-Tau. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2016, 54, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, Franz, Patricia Klöble, André Ruland, David Rosenkranz, Bastian Hinz, Falk Butter, Sanja Ramljak, Ulrich Zechner, and Holger Herlyn. The FOXP2-driven network in developmental disorders and neurodegeneration. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience 2017, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Lei, Nana Xu, Mengyao Huang, Wei Yi, Xuan Sang, Mingting Shao, Ye Li et al. A primate nigrostriatal atlas of neuronal vulnerability and resilience in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butovsky, Oleg, and Howard L. Weiner. Microglial signatures and their role in health and disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2018, 19, 622–635. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Celina, Emily H. Broersma, Anna S. Warden, Cristina Mora, Claudia Z. Han, Zahara Keulen, Nathanael Spann et al. Transcriptional and epigenetic targets of MEF2C in human microglia contribute to cellular functions related to autism risk and age-related disease. Nature Immunology 2025, 1–15.

- Xue, Feng, Jing Tian, Chunxiao Yu, Heng Du, and Lan Guo. Type I interferon response-related microglial Mef2c deregulation at the onset of Alzheimer's pathology in 5× FAD mice. Neurobiology of disease 2021, 152, 105272. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiangnan, Yanjing Guo, Wei Li, Zihao Zhang, Xinlei Li, Qidi Zhang, Qihang Du, Xinhuan Niu, Xijiang Liu, and Gongming Wang. Microglial priming induced by loss of Mef2C contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction in aged mice. Experimental neurology 2023, 365, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Swati, Nader Morshed, Sonia Beant Sidhu, Chizuru Kinoshita, Beth Stevens, Suman Jayadev, and Jessica E. Young. The Alzheimer's Disease Gene SORL1 Regulates Lysosome Function in Human Microglia. Glia 2025.

- Barthelson, Karissa, Morgan Newman, and Michael Lardelli. Sorting out the role of the sortilin-related receptor 1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease reports 2020, 4, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovesen, Peter Lund, Kristian Juul-Madsen, Narasimha S. Telugu, Vanessa Schmidt, Silke Frahm, Helena Radbruch, Emma Louise Louth et al. Alzheimer's Disease Risk Gene SORL1 Promotes Receptiveness of Human Microglia to Pro-Inflammatory Stimuli. Glia 2025, 73, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Swati, Allison Knupp, Jessica E. Young, and Suman Jayadev. Depletion of the AD risk gene SORL1 causes endo-lysosomal dysfunction in human microglia. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2022, 18, e068943. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, Toshinao, Kenichi Harigaya, Nobuo Sasaki, Yoshiaki Okamura, Hiroki Kokubo, Yumiko Saga, Katsuto Hozumi et al. Mastermind-like 1 (MamL1) and mastermind-like 3 (MamL3) are essential for Notch signaling in vivo. Development 2011, 138, 5235–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzofon, Nathaniel, Katrina Koc, Kristin Panwell, Nikita Pozdeyev, Carrie B. Marshall, Maria Albuja-Cruz, Christopher D. Raeburn et al. Mastermind like transcriptional coactivator 3 (MAML3) drives neuroendocrine tumor progression. Molecular Cancer Research 2021, 19, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintamen, Sana, Pallavi Gaur, Nicole Vo, Elizabeth M. Bradshaw, Vilas Menon, and Steven G. Kernie. Unique Microglial Transcriptomic Signature within the Hippocampal Neurogenic Niche. bioRxiv 2021.

- Bendavid, Guillaume, Céline Hubeau, Fabienne Perin, Alison Gillard, Marie-Julie Nokin, Oriane Carnet, Catherine Gerard et al. Role for the metalloproteinase ADAM28 in the control of airway inflammation, remodelling and responsiveness in asthma. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 13, 1067779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Lanlan, Wei Liu, and Fei Wang. Research progress on ADAM28 in malignant tumors. Discover Oncology 2025, 16, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, Maria, Jingyun Wu, Stefanie Hansen, and Jens Pahnke. Emerging role of ABC transporters in glia cells in health and diseases of the central nervous system. Cells 2024, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, Soumita, Arup Sarkar, Sarmistha Sinha Choudhury, Katherine A. Owen, Victoria L. Derr-Castillo, Sarah Fox, Lars Eckmann, Michael R. Elliott, James E. Casanova, and Peter B. Ernst. Engulfment and cell motility protein 1 (ELMO1) has an essential role in the internalization of Salmonella Typhimurium into enteric macrophages that impact disease outcome. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2015, 1, 311–324. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Hu, Zhenzhen Chen, Jie Zhao, Wei Li, and Shun Zhang. TNF-α/ENO1 signaling facilitates testicular phagocytosis by directly activating Elmo1 gene expression in mouse Sertoli cells. The FEBS Journal 2022, 289, 2809–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Di, Xiaoxiao Liu, Jinyu Li, Hanxin Wu, Jiaxuan Ma, and Wenlin Tai. ELMO1 regulates macrophage directed migration and attenuates inflammation via NF-κB signaling pathway in primary biliary cholangitis. Digestive and Liver Disease 2024, 56, 1897–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikdache, Aya, Laura Fontenas, Shahad Albadri, Celine Revenu, Julien Loisel-Duwattez, Emilie Lesport, Cindy Degerny, Filippo Del Bene, and Marcel Tawk. Elmo1 function, linked to Rac1 activity, regulates peripheral neuronal numbers and myelination in zebrafish. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2020, 77, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Hui, Elisa Bettella, Paul C. Marcogliese, Rongjuan Zhao, Jonathan C. Andrews, Tomasz J. Nowakowski, Madelyn A. Gillentine et al. Disruptive mutations in TANC2 define a neurodevelopmental syndrome associated with psychiatric disorders. Nature communications 2019, 10, 4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Yong, Changjun Yang, Mojgan Zadeh, Shane M. Sprague, Yang-Ding Lin, Heetanshi Sanjay Jain, Brenden Fitzgerald Determann et al. Functional regulation of microglia by vitamin B12 alleviates ischemic stroke-induced neuroinflammation in mice. Iscience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Gibieža, Paulius, and Vilma Petrikaitė. The regulation of actin dynamics during cell division and malignancy. American journal of cancer research 2021, 11, 4050. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Scott B. , Adam M. Sandor, Victor Lui, Jeffrey W. Chung, Monique M. Waldman, Robert A. Long, Miriam L. Estin, Jennifer L. Matsuda, Rachel S. Friedman, and Jordan Jacobelli. Formin-like 1 mediates effector T cell trafficking to inflammatory sites to enable T cell-mediated autoimmunity. elife 2020, 9, e58046. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Matthew R. , and Scott D. Blystone. Human macrophages utilize the podosome formin FMNL1 for adhesion and migration. CellBio 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Ah-Lai, Shamsinar Jalal, Tommy Pallett, Fuad Mosis, Ahmad Guni, Simon Brayford, Lawrence Yolland et al. Nance-Horan Syndrome-like 1 protein negatively regulates Scar/WAVE-Arp2/3 activity and inhibits lamellipodia stability and cell migration. Nature communications 2021, 12, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrori, Pegah, Baukje Bijnens, Laura Fumagalli, Kristofer Davie, Suresh Kumar Poovathingal, Tim Meese, Annet Storm et al. C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions impair microglial response in ALS. Nature Neuroscience 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, Hanno, and Akiko Shimamura. ETV6 in hematopoiesis and leukemia predisposition. In Seminars in hematology, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 98–104. WB Saunders, 2017.

- Villar, Javiera, Adeline Cros, Alba De Juan, Lamine Alaoui, Pierre-Emmanuel Bonte, Colleen M. Lau, Ioanna Tiniakou, Boris Reizis, and Elodie Segura. ETV3 and ETV6 enable monocyte differentiation into dendritic cells by repressing macrophage fate commitment. Nature immunology 2023, 24, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Xiaofang, Zheng Yan, Wei Jiang, and Xuejun Jiang. ETS variant transcription factor 6 enhances oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced inflammatory response in atherosclerotic macrophages via activating NF-κB signaling. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2022, 36, 20587384221076472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dataset | First author (Year) | Species | Condition(s) | Brain region(s) | Sample count | Microglia nuclei count | Reference |

| Dataset 1 | Martirosyan (2024) | Homo sapiens | PD vs Control | Midbrain | 29 | 18,149 | [12] |

| Dataset 2 | Lau (2020) | Homo sapiens | AD vs Control | Prefrontal cortex | 21 | 6,702 | [13] |

| Dataset 3 | Pineda (2024) | Homo sapiens | ALS vs FTLD vs Control | Prefrontal cortex + Motor cortex | 145 (73 donors) | 27,735 | [14] |

| Dataset 4 | Muralidharan (2025) | Homo sapiens | Old vs Young | Prefrontal cortex | 31 | 7,739 | [15] |

| Dataset 5 | Li (2025) | Homo sapiens | AD vs Control | Temporal cortex | 56 | 22,865 | [16] |

| Dataset 6 | Zhang (2021) | Macaca fascicularis | Old vs Young | Hippocampus | 15 | 39,589 | [17] |

| Dataset | Module (position among hub genes) |

Module GO enrichment (first term) |

Module enrichment (logFC, p-value) |

| SORL1 | |||

| Dataset 1 | greenyellow (5) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | PD (0.003, 8.96E-06) |

| Dataset 2 | lightyellow (3) | Positive Regulation Of Supramolecular Fiber Organization (GO:1902905) | AD (0.483, 0.0062) |

| Dataset 3 | black (3) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (12) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (11) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| MAML3 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (14) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (18) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | black (14) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (10) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (8) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| ARHGAP15 | |||

| Dataset 1 | brown (4) | Regulation Of Small GTPase Mediated Signal Transduction (GO:0051056) | NS PD (0.032, 0.055) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (23) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | magenta (12) | Peptidyl-Serine Phosphorylation (GO:0018105) | ALS > Control (0.407, 0.029); FTLD > Control (1.991, 1.35E-270); FTLD > ALS (-1.584, 0.00) |

| Dataset 4 | yellow (2) | Positive Regulation Of Axon Extension (GO:0045773) | Old (2.293, 3.67E-05) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (19) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| ETV6 | |||

| Dataset 1 | brown (22) | Regulation Of Small GTPase Mediated Signal Transduction (GO:0051056) | NS PD (0.032, 0.055) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (16) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | green (12) | Growth Hormone Receptor Signaling Pathway Via JAK-STAT (GO:0060397) | NS ALS > Control (0.069, 1.00); FTLD > Control (0.173, 3.02E-04); NS FTLD > ALS (-0.104, 0.083) |

| Dataset 4 | turquoise (8) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | Old (5.685, 1.72E-12) |

| Dataset 5 | turquoise (21) | Regulation Of Protein Kinase Activity (GO:0045859) | AD (0.323, 1.05E-20) |

| FMNL2 | |||

| Dataset 1 | blue (4) | Positive Regulation Of Pinocytosis (GO:0048549) | Control (-0.264, 0.0048) |

| Dataset 2 | yellow (20) | Detection Of Muscle Stretch (GO:0035995) | NS AD (1.184, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | royalblue (10) | Negative Regulation Of Autophagosome Assembly (GO:1902902) | NS ALS > Control (0.177, 1.00); FTLD > Control (1.500, 1.38E-102); FTLD > ALS (-1.323, 2.44E-145) |

| Dataset 4 | turquoise (24) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | Old (5.685, 1.72E-12) |

| Dataset 5 | turquoise (9) | Regulation Of Protein Kinase Activity (GO:0045859) | AD (0.323, 1.05E-20) |

| ELMO1 | |||

| Dataset 1 | brown (5) | Regulation Of Small GTPase Mediated Signal Transduction (GO:0051056) | NS PD (0.032, 0.055) |

| Dataset 2 | white (5) | Sterol Catabolic Process (GO:0016127) | NS AD (0.008, 0.617) |

| Dataset 3 | black (8) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 5 | yellow (1) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| ZFAND3 | |||

| Dataset 1 | brown (6) | Regulation Of Small GTPase Mediated Signal Transduction (GO:0051056) | NS PD (0.032, 0.055) |

| Dataset 2 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 3 | midnightblue (9) | Response To Lipopolysaccharide (GO:0032496) | NS ALS > Control (0.160, 1.00); NS Control > FTLD (-0.576, 1.00); NS ALS > FTLD (0.736, 1.00) |

| Dataset 4 | turquoise (2) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | Old (5.685, 1.72E-12) |

| Dataset 5 | turquoise (14) | Regulation Of Protein Kinase Activity (GO:0045859) | AD (0.323, 1.05E-20) |

| MEF2A | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (2) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | yellow (2) | Detection Of Muscle Stretch (GO:0035995) | NS AD (1.184, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | cyan (19) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (21) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| ITPR2 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (3) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 3 | cyan (9) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (21) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (9) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| ADAM28 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (4) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (2) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | black (13) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 5 | yellow (4) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| ABCC4 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (7) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (7) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | black (5) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 5 | yellow (16) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| ATP8B4 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (5) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (6) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | cyan (10) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 5 | yellow (14) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| SRGAP2 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (9) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 3 | cyan (21) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | red (8) | Positive Regulation Of Ras Protein Signal Transduction (GO:0046579) | Young (-3.523, 0.00) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (10) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| SRGAP2B | |||

| Dataset 1 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 2 | cyan (1) | Regulation Of Postsynapse Organization (GO:0099175) | NS Control (-0.948, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | black (18) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | red (1) | Positive Regulation Of Ras Protein Signal Transduction (GO:0046579) | Young (-3.523, 0.00) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (6) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| FRMD4A | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (23) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | yellow (19) | Detection Of Muscle Stretch (GO:0035995) | NS AD (1.184, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | cyan (2) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 5 | yellow (22) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| SND1 | |||

| Dataset 1 | red (2) | ERAD Pathway (GO:0036503) | PD (0.139, 4.09E-12) |

| Dataset 2 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 3 | red (1) | Response To Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress (GO:0034976) | NS ALS > Control (2.594, 1.00); NS FTLD > Control (0.137, 1.00); NS ALS > FTLD (2.456, 1.00) |

| Dataset 4 | magenta (5) | Innate Immune Response-Activating Signaling Pathway (GO:0002758) | Old (3.250, 3.03E-12) |

| Dataset 5 | turquoise (13) | Regulation Of Protein Kinase Activity (GO:0045859) | AD (0.323, 1.05E-20) |

| ARHGAP22 | |||

| Dataset 1 | greenyellow (3) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | PD (0.003, 8.96E-06) |

| Dataset 2 | cyan (14) | Regulation Of Postsynapse Organization (GO:0099175) | NS Control (-0.948, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | cyan (12) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (6) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| ANKRD44 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (1) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 3 | black (1) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (2) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (7) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| TCF12 | |||

| Dataset 1 | green (24) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Control (-0.302, 3.5E-10) |

| Dataset 2 | darkturquoise (6) | Mitochondrial Membrane Organization (GO:0007006) | Control (-0.552, 3.23E-04) |

| Dataset 3 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 4 | turquoise (4) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | Old (5.685, 1.72E-12) |

| Dataset 5 | turquoise (7) | Regulation Of Protein Kinase Activity (GO:0045859) | AD (0.323, 1.05E-20) |

| FMN1 | |||

| Dataset 1 | yellow (4) | Cellular Response To Epidermal Growth Factor Stimulus (GO:0071364) | PD (1.168, 5.51E-81) |

| Dataset 2 | white (4) | Sterol Catabolic Process (GO:0016127) | NS AD (0.008, 0.617) |

| Dataset 3 | blue (6) | Response To Unfolded Protein (GO:0006986) | Control > ALS (-8.516, 1.48E-08); FTLD > Control (2.746, 9.93E-267); FTLD > ALS (-11.262, 0.00) |

| Dataset 4 | turquoise (23) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | Old (5.685, 1.72E-12) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| ATM | |||

| Dataset 1 | greenyellow (2) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | PD (0.003, 8.96E-06) |

| Dataset 2 | lightyellow (1) | Positive Regulation Of Supramolecular Fiber Organization (GO:1902905) | AD (0.483, 0.00623) |

| Dataset 3 | black (8) | Positive Regulation Of T Cell Proliferation (GO:0042102) | ALS > Control (0.730, 9.46E-33); FTLD > Control (0.768, 1.01E-95); FTLD > ALS (-0.038, 2.83E-30) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (22) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| FAM135A | |||

| Dataset 1 | greenyellow (9) | Protein Phosphorylation (GO:0006468) | PD (0.003, 8.96E-06) |

| Dataset 2 | magenta (2) | mRNA Splicing, Via Spliceosome (GO:0000398) | NS AD (0.493, 0.068) |

| Dataset 3 | darkturquoise (3) | Immunoglobulin Mediated Immune Response (GO:0016064) | NS Control > ALS (-0.225, 1.00); FTLD > Control (0.632, 4.20E-54); FTLD > ALS (-0.856, 1.69E-110) |

| Dataset 4 | yellow (18) | Positive Regulation Of Axon Extension (GO:0045773) | Old (2.293, 3.67E-05) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| SPTLC2 | |||

| Dataset 1 | grey60 (11) | Plasma Membrane Bounded Cell Projection Assembly (GO:0120031) | NS PD (0.038, 1.00) |

| Dataset 2 | cyan (22) | Regulation Of Postsynapse Organization (GO:0099175) | NS Control (-0.948, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | greenyellow (8) | N-glycan Processing (GO:0006491) | ALS > Control (0.165, 1.05E-07); NS Control > FTLD (-0.238, 1.00); ALS > FTLD (0.403, 1.82E-06) |

| Dataset 4 | pink (17) | Sphingosine Metabolic Process (GO:0006670) | Old (4.156, 1.57E-179) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| ACER3 | |||

| Dataset 1 | grey60 (19) | Plasma Membrane Bounded Cell Projection Assembly (GO:0120031) | NS PD (0.038, 1.00) |

| Dataset 2 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 3 | green (11) | Growth Hormone Receptor Signaling Pathway Via JAK-STAT (GO:0060397) | NS ALS > Control (0.069, 1.00); FTLD > Control (0.173, 3.02E-04); NS FTLD > ALS (-0.104, 0.083) |

| Dataset 4 | pink (23) | Sphingosine Metabolic Process (GO:0006670) | Old (4.156, 1.57E-179) |

| Dataset 5 | turquoise (12) | Regulation Of Protein Kinase Activity (GO:0045859) | AD (0.323, 1.05E-20) |

| TANC2 | |||

| Dataset 1 | lightgreen (5) | Regulation Of Lipid Biosynthetic Process (GO:0046890) | PD (0.350, 1.06E-08) |

| Dataset 2 | blue (21) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | magenta (8) | Peptidyl-Serine Phosphorylation (GO:0018105) | ALS > Control (0.407, 0.029); FTLD > Control (1.991, 1.35E-270); FTLD > ALS (-1.584, 0.00) |

| Dataset 4 | pink (12) | Sphingosine Metabolic Process (GO:0006670) | Old (4.156, 1.57E-179) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| NHSL1 | |||

| Dataset 1 | lightgreen (17) | Regulation Of Lipid Biosynthetic Process (GO:0046890) | PD (0.350, 1.06E-08) |

| Dataset 2 | cyan (15) | Regulation Of Postsynapse Organization (GO:0099175) | NS Control (-0.948, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | lightyellow (11) | Humoral Immune Response Mediated By Circulating Immunoglobulin (GO:0002455) | Control > ALS (-1.103, 1.41E-12); FTLD > Control (1.604, 6.71E-74); FTLD > ALS (-2.708, 9.42E-246) |

| Dataset 4 | pink (9) | Sphingosine Metabolic Process (GO:0006670) | Old (4.156, 1.57E-179) |

| Dataset 5 | Not included | ||

| BMP2K | |||

| Dataset 1 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 2 | blue (1) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | NS AD (0.777, 1.00) |

| Dataset 3 | greenyellow (9) | N-glycan Processing (GO:0006491) | ALS > Control (0.165, 1.05E-07); NS Control > FTLD (-0.238, 1.00); ALS > FTLD (0.403, 1.82E-06) |

| Dataset 4 | yellow (1) | Positive Regulation Of Axon Extension (GO:0045773) | Old (2.293, 3.67E-05) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (13) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

| AOAH | |||

| Dataset 1 | Not included | ||

| Dataset 2 | darkred (8) | Positive Regulation Of Mast Cell Degranulation (GO:0043306) | NS Control (-0.485, 0.403) |

| Dataset 3 | cyan (25) | Positive Regulation Of Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Nucleation (GO:2000601) | ALS > Control (0.561, 1.41E-27); NS Control > FTLD (-0.024, 1); ALS > FTLD (0.585, 5.58E-32) |

| Dataset 4 | brown (18) | Positive Regulation Of GTPase Activity (GO:0043547) | Young (-1.689, 1.23E-112) |

| Dataset 5 | yellow (25) | Regulation Of Intracellular Signal Transduction (GO:1902531) | Control (-0.473, 5.78E-14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).