Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.2.1. Cool Executive Functions

2.2.2. Hot Executive Functions

2.2.3. Theory of Mind

2.3. The intervention

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Within-Group Differences (Before and After Intervention)

3.2. Baseline (Pre-Intervention) Group Comparisons

3.3. Post-Intervention Comparisons (Efficacy of the Training)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EF | Executive function |

| ToM | Theory of Mind |

| SLD | Specific learning disorders |

| UOT | Unstuck and On Target |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, L.A.; Bettenay, C. The assessment of executive functioning in children. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2010, 15, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Function in Education: From Theory to Practice; Meltzer, L., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P. The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Carlson, S.M. Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012, 6, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Getz, S.; Galván, A. The adolescent brain. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locascio, G.; Mahone, E.M.; Eason, S.H.; Cutting, L.E. Executive dysfunction among children with reading comprehension deficits. J. Learn. Disabil. 2010, 43, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, S.H.; Goldberg, L.F.; Young, K.M.; Geist, M.C.; Cutting, L.E. Integrating executive function and reading: A systematic review. J. Learn. Disabil. 2012, 45, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, H.L.; Zheng, X.; Jerman, O. Working memory, short-term memory, and reading disabilities: A selective meta-analysis of the literature. J. Learn. Disabil. 2009, 42, 260–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouklari, E.-C.; Tsermentseli, S.; Pavlidou, A. Hot and cool executive function and theory of mind in children with and without specific learning disorders. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S.M.; Moses, L.J.; Breton, C. How specific is the relation between executive function and theory of mind? Contributions of inhibitory control and working memory. Infant Child Dev. 2002, 11, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, J.; Lang, B. Development of theory of mind and executive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurz, M.; Radua, J.; Aichhorn, M.; Richlan, F.; Perner, J. Fractionating theory of mind: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 42, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, S.J.; Bailey, A.J. Are there theory of mind regions in the brain? A review of the neuroimaging literature. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009, 30, 2313–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Function in Education: From Theory to Practice, 2nd ed.; Meltzer, L., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A.; Ling, D.S. Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbach, J.; Unger, K. Executive control training from middle childhood to adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehler, C.; Joerns, C.; Schuchardt, K. Training working memory of children with and without dyslexia. Children 2019, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, J.; Gathercole, S.E. Taking working memory training from the laboratory into schools. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 34, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, T.P. Working memory, but not IQ, predicts subsequent learning in children with learning difficulties. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 25, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y. Working-memory training improves developmental dyslexia in Chinese children. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodieci, A.; Romano, M.; Castro, E.; Di Lieto, M.C.; Bonetti, S.; Spoglianti, S.; Pecini, C. Executive functions and rapid automatized naming: A new tele-rehabilitation approach in children with language and learning disorders. Children 2022, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassai, R.; Futo, J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Takacs, Z.K. A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence on the near- and far-transfer effects among children’s executive function skills. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez Arana, C.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Serrano-Juarez, C.A.; de Pauw, S.S.W.; Prinzie, P. Interventions to improve executive functions in children and adolescents with acquired brain injury: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Child Neuropsychol. 2024, 30, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giusto, V.; Purpura, G.; Zorzi, C.F.; Blonda, R.; Brazzoli, E.; Meriggi, P.; Reina, T.; Rezzonico, S.; Sala, R.; Olivieri, I.; Cavallini, A. Virtual reality rehabilitation program on executive functions of children with specific learning disorders: A pilot study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1241860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefaei, M.M. The effect of brain training video games on improving visuospatial working memory and executive function in children with dyscalculia. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappo, R.; et al. Computerized training of executive functions in a child with specific learning disorders: A descriptive study. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for Extended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE), Rome, Italy, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, Y.; Moradi, N. The effectiveness of working memory training on inhibition and reading performance of students with specific learning disabilities (dyslexia). Neuropsychology 2019, 4(15), 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derikvand, M.; Shehni Yailagh, M.; Hajiyakhchali, A. The effectiveness of a cognitive rehabilitation game on executive function and reading skills in students with dyslexia. Biquart. J. Cogn. Strateg. Learn. 2023, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Takacs, Z.K.; Kassai, R. The efficacy of different interventions to foster children’s executive function skills: A series of meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 653–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, R.; Dworetsky, A.; Coalson, R.S.; Petersen, S.E.; Schlaggar, B.L.; Rosch, K.S.; Horowitz-Kraus, T. An executive-functions-based reading training enhances sensory–motor systems integration during reading fluency in children with dyslexia. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhae166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouklari, E.C.; Tsermentseli, S.; Monks, C.P. Developmental trends of hot and cool executive function in school-aged children with and without autism spectrum disorder: Links with theory of mind. Dev. Psychopathol. 2019, 31, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, J.; Klesczewski, J.; Fischbach, A.; Schuchardt, K.; Büttner, G.; Hasselhorn, M. Working memory in children with learning disabilities in reading versus spelling: Searching for overlapping and specific cognitive factors. J. Learn. Disabil. 2015, 48, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopapas, A.; Skaloumbakas, C. Software for screening learning skills and difficulties (LAMDA). EPEAEK II Action 2008, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, J. Raven progressive matrices. In Handbook of Nonverbal Assessment; McCallum, R.S., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, S.M.; Moses, L.J. Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, S.A.; Espy, K.A.; Charak, D. Using confirmatory factor analysis to understand executive control in preschool children: I. Latent structure. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 44, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.T.; Piper, B.J. The psychology experiment building language (PEBL) and PEBL test battery. J. Neurosci. Methods 2014, 222, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, D.A.; Berg, E. A behavioral analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card-sorting problem. J. Exp. Psychol. 1948, 38, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, A.; Kopp, B.; Lange, F. The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Split-Half Reliability Estimates for a Self-Administered Computerized Variant. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallice, T. Specific impairments of planning. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1982, 298, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 5th ed.; Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara, A.; Damasio, A.R.; Damasio, H.; Anderson, S.W. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to prefrontal cortex. Cognition 1994, 50, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdejo-Garcia, A.; Bechara, A.; Recknor, E.C.; Perez-Garcia, M. Decision-making and the Iowa Gambling Task: Ecological validity in individuals with substance dependence. Psychol. Belg 2006, 46, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W.; Ebbesen, E.B.; Zeiss, A.R. Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 21, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begeer, S.; Bernstein, D.M.; van Wijhe, J.; Scheeren, A.M.; Koot, H.M. A continuous false belief task reveals egocentric biases in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2012, 16, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Scahill, V.; Lawson, J.; Spong, A. Are intuitive physics and intuitive psychology independent? A test with children with Asperger syndrome. J. Dev. Learn. Disord. 2001, 5, 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Abascal, E.G.; Cabello, R.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Baron-Cohen, S. Test–retest reliability of the ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ test: A one-year follow-up study. Mol. Autism 2013, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellante, M.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Melis, M.; Marrone, M.; Petretto, D.R.; Masala, C.; Preti, A. The ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ test: Systematic review of psychometric properties and a validation study in Italy. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 18, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, L.; Kenworthy, L.; Alexander, K.C.; Werner, M.A.; Anthony, L.G. Unstuck and on Target: An Executive Function Curriculum to Improve Flexibility for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders; Paul H. Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, L.; Kenworthy, L.; Alexander, K.; Werner, M.; Anthony, L.G. Unstuck and on Target!: An Executive Function Curriculum to Improve Flexibility, Planning, and Organization, 2nd ed.; Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, L.; Anthony, L.G.; Naiman, D.Q.; Cannon, L.; Wills, M.C.; Luong-Tran, C.; Werner, M.A.; Alexander, K.C.; Strang, J.; Bal, E.; Sokoloff, J.L.; Wallace, G.L. Randomized controlled effectiveness trial of executive function intervention for children on the autism spectrum. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, L.; Anthony, B.; Kenworthy, L. Improving Classroom Behaviors among Students with Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI): Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK615639/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Dimitrov, D.M.; Rumrill, P.D., Jr. Pretest-posttest designs and measurement of change. Work 2003, 20, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, G. Quade’s nonparametric analysis of covariance of matching. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1985, 17, 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, H.; Gray, K.; Ellis, K.; Taffe, J.; Cornish, K. Impact of attention training on academic achievement, executive functioning, and behavior: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 122, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R.; Miller, P.H. A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 1641–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D. Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain. Dev. Rev. 2015, 38, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Getz, S.; Galván, A. The adolescent brain. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, B.; Padmanabhan, A.; O’Hearn, K. What has fMRI told us about the development of cognitive control through adolescence? Brain Cogn. 2010, 72, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Müller, U. Executive function in typical and atypical development. In Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development; Goswami, U., Ed.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 445–469. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano, E. Links between theory of mind and executive function in young children with autism: Clues to developmental primacy. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perner, J.; Lang, B. Development of theory of mind and executive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, N.; Happé, F. A training study of theory of mind and executive function in children with autistic spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2005, 35, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S.M.; Moses, L.J. Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxe, R.; Carey, S.; Kanwisher, N. Understanding other minds: Linking developmental psychology and functional neuroimaging. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 87–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. Nativism versus neuroconstructivism: Rethinking the study of developmental disorders. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child Characteristic |

Control (n = 16) M (SD) |

Intervention (n = 24) M(SD) |

Statistic | p | |

| Gender | Boy Girl |

62.5% (10) 37.5% (6) |

62.5% (15) 37.5% (9) |

χ²(1) = 0.000 | 0.99 |

| Age¹ | – | 9.28 (0.73) | 8.86 (0.62) | t(38) = 1.947 | .059 |

| Grade | 3rd 4th |

50.0% (8) 50.0% (8) |

58.3% (14) 41.7% (10) |

χ²(1) = 0.269 | .604 |

| IQ¹ | – | 94.69 (11.76) | 100.21 (13.23) | Z = −1.329 | .184 |

|

Pre M(SD) |

Post M(SD) |

Statistic | p | |

| Cool Executive Functions | ||||

| Inhibition errors | 238.06 (14.60) | 243.13 (15.57) | Z = –1.009 | .313 |

| Working memory | 13.13 (3.54) | 12.13 (3.72) | t(15) = 1.426 | .174 |

| Planning | 6.25 (1.44) | 6.88 (1.82) | t(15) = –1.373 | .190 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 67.75 (20.15) | 70.19 (21.43) | t(15) = –0.689 | .469 |

| Hot Executive Functions | ||||

| Affective decision-making | –0.050 (0.13) | –0.023 (0.19) | t(15) = –0.734 | .459 |

| Delay of gratification | 915.25 (415.62) | 960.13 (347.00) | Z = –0.357 | .721 |

| Theory of Mind (ToM) | ||||

| False belief understanding | 2.98 (2.73) | 1.96 (3.15) | Z = –1.643 | .100 |

| Mental state/emotion recognition | 14.00 (4.16) | 12.31 (3.11) | t(15) = 2.097 | .053 |

| Variable |

Pre M(SD) |

Post M(SD) |

Statistic | p |

| Cool Executive Functions | ||||

| Inhibition errors | 253.92 (23.20) | 256.58 (17.98) | Z = –0.686 | .493 |

| Working memory | 12.79 (2.78) | 13.63 (2.24) | t(23) = –2.145 | .043* |

| Planning | 7.13 (1.70) | 8.38 (1.91) | t(23) = –2.571 | .017* |

| Cognitive flexibility | 79.21 (12.69) | 85.79 (13.13) | t(23) = –3.168 | .004** |

| Hot Executive Functions | ||||

| Affective decision-making | –0.060 (0.30) | –0.086 (0.22) | Z = –0.167 | .867 |

| Delay of gratification | 939.79 (344.10) | 951.63 (369.51) | Z = –0.454 | .650 |

| Theory of Mind (ToM) | ||||

| False belief understanding | 1.04 (2.61) | 1.47 (2.58) | Z = –0.601 | .548 |

| Mental state/ emotion recognition | 13.58 (4.83) | 14.83 (4.19) | t(23) = –1.978 | .060 |

| Variable |

Control M(SD) |

Intervention M(SD) |

Statistic | p |

| Cool Executive Functions | ||||

| Inhibition errors | 238.06 (14.60) | 253.92 (23.20) | Z = –2.748 | .006** |

| Working memory | 13.13 (3.54) | 12.79 (2.78) | t(38) = 0.333 | .741 |

| Planning | 6.25 (1.44) | 7.13 (1.70) | t(38) = –1.691 | .099 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 67.75 (20.15) | 79.21 (12.69) | t(22.93) = –2.022 | .055 |

| Hot Executive Functions | ||||

| Affective decision-making | –0.05 (0.13) | –0.06 (0.30) | Z = –0.277 | .782 |

| Delay of gratification | 915.25 (415.62) | 939.79 (344.10) | Z = –0.090 | .929 |

| Theory of Mind (ToM) | ||||

| False belief understanding | 2.98 (2.73) | 1.04 (2.61) | Z = –2.988 | .003** |

| Mental state/ emotion recognition | 14.00 (4.16) | 13.58 (4.83) | t(38) = 0.282 | .779 |

| Variable |

Control M(SD) |

Intervention M (SD) |

F(1, 38) | p | η² |

| Cool Executive Functions | |||||

| Inhibition errors | 243.13 (15.57) | 256.58 (17.98) | 1.924 | .173 | .048 |

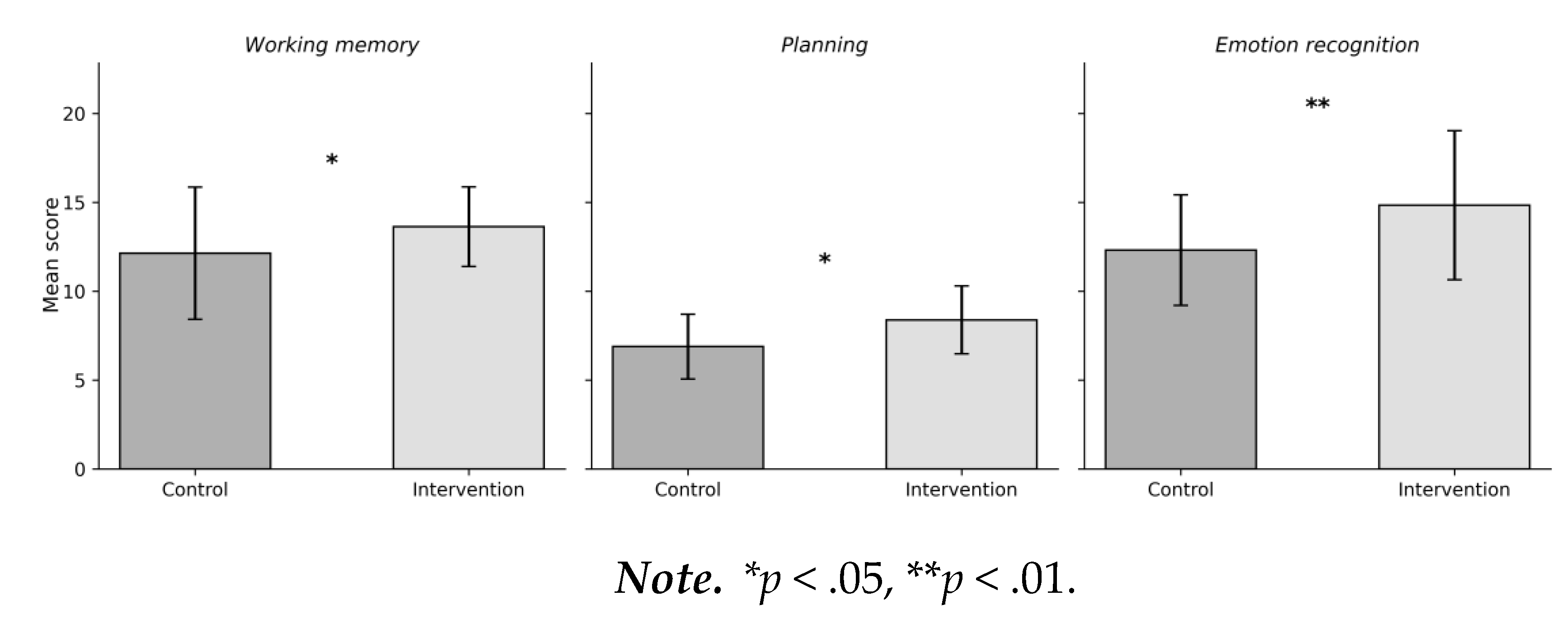

| Working memory | 12.13 (3.72) | 13.63 (2.24) | 5.620 | .023* | .129 |

| Planning | 6.88 (1.82) | 8.38 (1.91) | 4.626 | .038* | .109 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 70.19 (21.43) | 85.79 (13.13) | 2.368 | .132 | .059 |

| Hot Executive Functions | |||||

| Affective decision-making | –0.023 (0.19) | –0.086 (0.22) | 1.034 | .316 | .026 |

| Delay of gratification | 960.13 (347.00) | 951.63 (369.51) | 0.007 | .933 | <.001 |

| Theory of Mind (ToM) | |||||

| False belief understanding | 1.96 (3.15) | 1.47 (2.58) | 1.062 | .309 | .027 |

| Mental state/emotion recognition | 12.31 (3.11) | 14.83 (4.19) | 9.716 | .003** | .204 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).