1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD), one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases, is particularly prevalent in people over the age of 65, and today more than 6 million people worldwide suffer from PD [

1]. Most cases of PD are not caused by changes in the human genome, and genetic mutations are found in less than 15% of patients; the etiology of the disease requires further research [

2,

3,

4]. According to the WHO, the prevalence of PD has doubled over the past 25 years. Global estimates suggest that more than 8.5 million people suffered from PD in 2019. Current estimates show that PD resulted in 5.8 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is 81% more than in 2000, and caused 329,000 deaths, which is more than 100% more than in 2000 [

5]. In recent years, studies have emerged on the impact of COVID-19 on the progression of Parkinson's disease through neuroinflammation caused by cytokine storms [

6]. PD leads to severe disability and requires significant treatment and rehabilitation costs, making it an important social problem [

7]. One of the key problems in the treatment of PD is its late diagnosis, due to the late onset of clinical symptoms and the lack of biomarkers that would allow PD to be identified at an early stage [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The clinical motor symptoms of PD include resting tremor, bradykinesia, muscle rigidity, and gait and balance disorders. These motor disorders occur in patients in the late stages of the disease, when the loss of dopamine neurons exceeds 50%. The clinical manifestations of PD are preceded by a prodromal stage of the disease, characterized by progressive functional changes in the autonomic nervous system, including dysfunction of the enteric nervous system (ENS), manifested by disturbances in the motility of the gastrointestinal tract and the accumulation of the PD-pathognomonic protein α-synuclein in the neurons of the ENS [

12]. According to one of the leading hypotheses [

13], the pathogenesis of PD involves the gradual spread of pathological forms of α-synuclein from the peripheral nervous system to structures of the central nervous system (CNS), including the substantia nigra. The etiological factor triggering the pathological process of α-synuclein accumulation in the CNS may be inflammation in the intestine [

14], as evidenced by increased α-synuclein expression and epithelial barrier permeability in the colon [

15,

16].

Lactacystin (LAC), a proteasome inhibitor, when administered to the substantia nigra, striatum, or medial forebrain bundle of experimental animals, caused increased α-synuclein expression and neurodegeneration in the nigrostriatal system [

17]. However, it is not known whether there are any changes in structures of the nervous system more distant from the site of lactacystin administration, including the peripheral nervous system (PNS). There are also no data on the combined effect of inflammation and suppression of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the CNS.

Classic toxic and neuroinflammatory models of PD do not reproduce one of the key features of PD in CNS neurons: the formation of Lewy bodies. However, according to the literature, the combined administration of neurotoxins with lactacystin caused the appearance of α-synuclein aggregates in the neurons of the substantia nigra [

18,

19]. In this regard, we hypothesized that the administration of lactacystin in a neuroinflammation model would also reproduce the formation of intraneuronal α-synuclein aggregates in neurons of the central and/or peripheral nervous system.

Thanks to the multifunctional connection between the enteric, central nervous, and immune systems, the gut can serve as a “point of application” for various therapeutic approaches to treating neurodegenerative diseases. The influence of functional bacteria and their metabolites on the processes of immune and nervous regulation of functions in the human body is currently being widely studied [

8,

20].

The development of drugs capable of effectively treating PD faces several challenges. The first is the presence of a large number of disorders (biomarkers of damage) in various organs and systems of the human body. Second, the inability of existing and developing synthetic and semi-synthetic drugs to correct disorders (damage) in several areas. Third, the low adequacy of existing animal models of Parkinson's disease and, as a result, problems with translating the data obtained to the human body. Fourth, the heterogeneity of the disease, its etiology, and the need for careful selection of patient cohorts for clinical trials. To a certain extent, these problems can be solved based on a new conceptual approach that we proposed in a recently published review [

8]. This involves the development of live biotherapeutic drugs based on commensal bacteria (Lactobacillus) from the intestines of healthy individuals with a potentially multifunctional (multi-target) effect on the patient's body; construction of a model of the functional architecture of PD, involving the identification of key signs of the disease: neurological, neuroendocrine, immune, neuroinflammatory, biochemical, genetic, epigenetic, and others; selection of animal models and their combinations aimed at simulating the early stages of PD; subsequent selection of a cohort of patients for clinical trials adequate for the multi-locus effect of the pharmabiotics drug.

In this study, the strain

Limosilactobacillus fermentum U-21 was investigated as a candidate for pharmabiotics. The strain was isolated from the feces of a healthy man (a astronaut after flight) living in the central European part of Russia. The strain is deposited in the All-Russian Collection of Industrial Microorganisms (VKPM) No. B-12075. Genome assembly in GenBank NCBI ASM286982v2.

L. fermentum U-21 is characterized by the presence of genes and products with potential neuromodulatory, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory activity [

21]. The studied strain

L. fermentum U-21 showed high antioxidant activity

in vitro and

in vivo studies using the oxidative stress inducer paraquat. In the

E. coli K-12 bioluminescence system, it was found that the culture fluid of the

L. fermentum U-21 strain inhibits paraquat activity by 25%. [

22]. In a model of the free-living nematode

Caenorhabditis elegans, the

L. fermentum U-21 strain increased the median lifespan of nematodes under oxidative stress conditions [

23]. In a model of induced Parkinsonism in rodents, the administration of

L. fermentum U-21 in parallel with paraquat injections prevented the degradation of dopaminergic neurons in the brain [

23] and pathological changes in internal organs [

24]. In parallel with studies of the strain's properties in various

in vitro and

in vivo models, an analysis and search for low-molecular-weight metabolites, proteins, and enzymes that potentially determine the identified properties of the

L. fermentum U-21 strain, the identification and characterization of pharmacologically active ingredients (PAIs) that determine the specific nosological properties of the pharmabiotics are among the key requirements for live biotherapeutic drugs being developed today. [

21,

25,

26]. Using genomic, metabolomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic analysis, candidates for pharmacologically active ingredients were identified: ATP-dependent Clp protease ClpL, Chaperone protein DnaK, Thioredoxin reductase, NAD(P)/FAD-dependent oxidoreductase, LysM peptidoglycan-binding domain-containing protein, NlpC/P60 domain-containing protein, tryptophan, and niacin. Understanding that under normal intestinal conditions and during inflammatory processes, the strain can alter gene expression and produce a shifted PAI profile, transcriptomic and proteomic analysis was performed under the action of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) [

27]. Groups of genes that significantly alter their expression were identified: genes of the putative urea carboxylase operon, transport genes, including Fe2+ and Cu2+ metal ions, as well as the synthesis and catabolism of certain amino acids. Genomic analysis of the strain allowed the identification of 29 genes, including genes of the thioredoxin complex, whose products may exhibit antioxidant properties. Taken together, the data obtained demonstrate the unique antioxidant properties of the strain, allowing it to be positioned as a promising candidate for the development of a live biotherapeutic drug for the therapy of certain forms of Parkinson's disease. [

24,

28,

29,

30,

31].

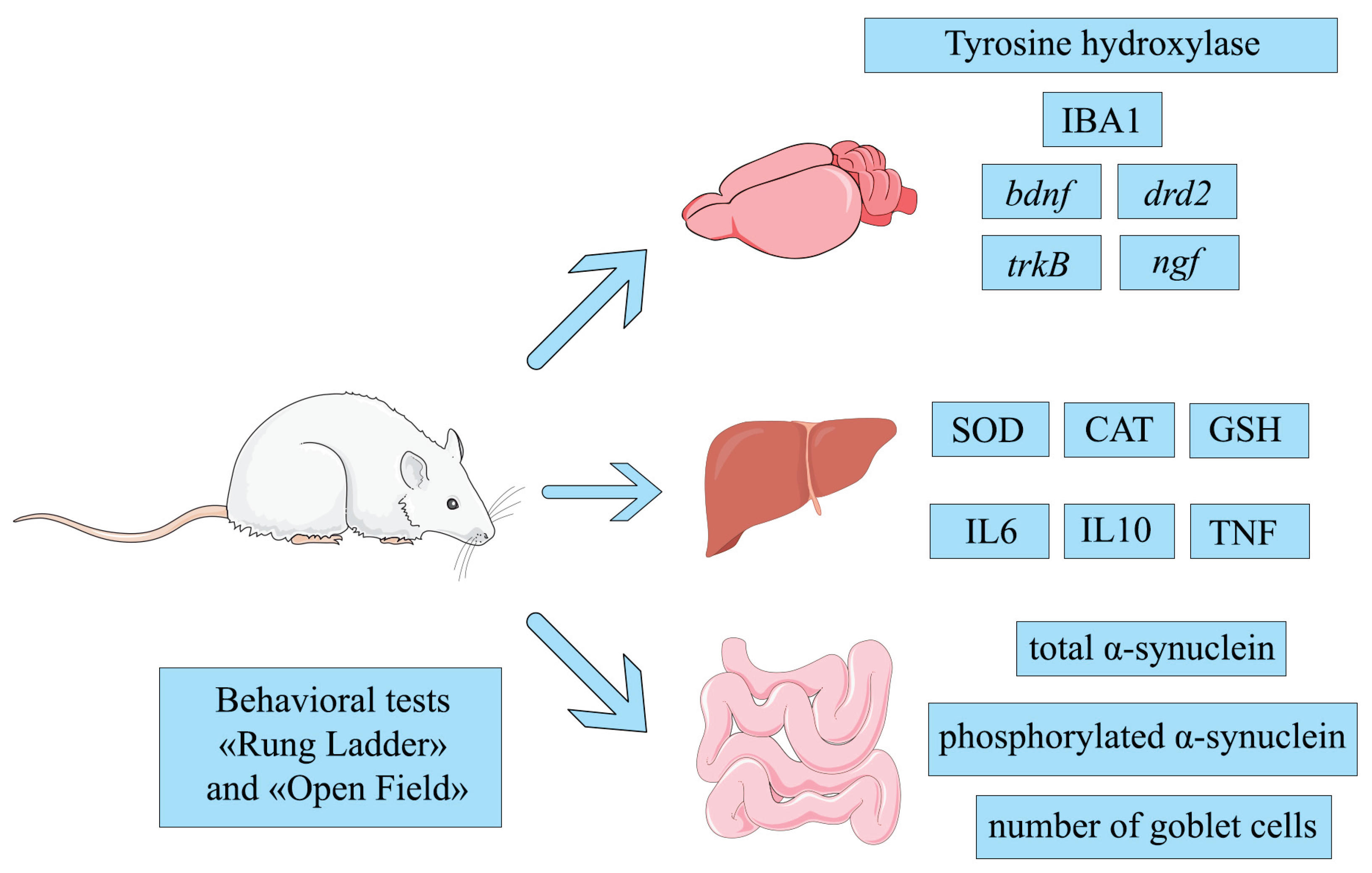

This study investigated various indicators associated with PD development: tyrosine hydroxylase, IBA1 protein in the brain, total and phosphorylated α-synuclein in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus in the intestine, expression of the genes

ngf, drd2, bdnf, trkB in the striatum, markers of redox potential in the liver - superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), reduced glutathione (GSH); levels of cytokines IL6, IL10, TNF in the liver; assessment of the condition using behavioral tests. Tyrosine hydroxylase is an enzyme that limits the rate of dopamine synthesis, so studying this biomarker is important for assessing the degree of neurodegeneration in the brain [

32]. IBA1 is considered a potential biomarker of microglial activation and early changes in PD [

33,

34]. Detection of α-synuclein and phosphorylated α-synuclein levels in the peripheral nervous system allows for the identification of earlier stages of PD [

35]. The binding of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) to its related receptor, TrkB, promotes the health of dopaminergic neurons by activating the receptor. BDNF gene expression is reduced in patients with PD [

36,

37]. NGF (nerve growth factor) has nerve growth-stimulating activity and is involved in the regulation of the growth and differentiation of sympathetic and sensory neurons [

38,

39]. The

drd2 gene encodes the D2 dopamine receptor, one of the most common types of dopamine receptors in the brain. D2 receptors ensure the functioning of the dopaminergic system [

40]. Oxidative stress plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of PD. The antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD) [

41], сatalase (CAT) and GSH level reflect the redox balance [

42]. Proinflammatory (IL6, TNF) and anti-inflammatory (IL10) cytokines reflect systemic inflammation, which is closely associated with neurodegeneration. Conducting “Open field” and “Rung ladder” tests in rats with a PD model is critical for an objective assessment of the motor and behavioral disorders characteristic of this disease. These tests allow us to judge the severity of neurodegenerative changes [

43].

Research objective: to evaluate the effect of the studied pharmabiotics LfU21 based on the L.fermentum U-21 strain on biochemical, immunomodulatory, and transcriptional biomarkers, as well as animal behavior in a combined LPS+LAC model of PD in Wistar rats; to use the signatures of selected biomarkers in the subsequent formation of a cohort of patients for clinical studies.

3. Discussion

Parkinson's disease is associated with functional disorders (damage) of many genes in various organs and systems of the body at different stages of its development. This was the reason for choosing

L.fermentum U-21 (LfU21) as a candidate for live biotherapeutic products. Previously, using omics technologies, it has been shown that it is capable of synthesizing a number of pharmacologically active substances with potential anti-Parkinson's properties [

21,

22,

23]. The multifunctionality of the synthesized ingredients suggests that the LfU21 drug candidate is capable of recovering (correcting) several impaired functions. The next important step was to select a combined PD model.

In this study, we propose a combined model of Parkinsonism to simulate the multifactorial etiology of PD and reproduce the key features of the disease. The first “hit” is a neurotoxic effect of lactacystin on the substantia nigra pars compacta. This toxin acts as an inhibitor of proteasome activity through its derivative, clasto-lactacystin-β-lactone, which irreversibly blocks the 20S proteasome complex, contributing to the pathological accumulation of α-synuclein and its subsequent aggregation [

44]. The second “hit” was the systemic activation of the immune system caused by intraperitoneal administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from the bacterial wall of gram-negative bacteria. As shown, the endotoxin used, acting as a pathogen-associated pattern, is capable of activating pattern recognition receptors, which ultimately stimulates immune cells to activate the cytokine response. Synthesized peripheral cytokines can be actively transported to the CNS through the circumventricular organs, where the blood-brain barrier is more permeable, or transmit impulses through their receptors on the afferents of the vagus nerve. These events together may contribute to the development of neuroinflammation through local cytokine production by microglia and astrocytes, leading to the loss of dopaminergic neurons and exacerbating the course of the disease [

45].

In our work, we used various biomarkers covering different aspects involved in the development of PD. The brain, liver, and the intestine were selected as the main organs for analysis. In the brain, the following were analyzed: tyrosine hydroxylase and IBA1 protein levels and the expression of the drd2, ngf, bdnf, and trkB genes. In the liver, the redox potential and cytokine content were analyzed by measuring SOD, CAT, GSH, IL6, IL10, and TNF. In the intestine, the levels of total and phosphorylated α-synuclein were measured, as well as the number of goblet cells. In addition to functional biomarkers, the results of the “Rung ladder” and “Open Field” behavioral tests were recorded to assess the general condition of the body.

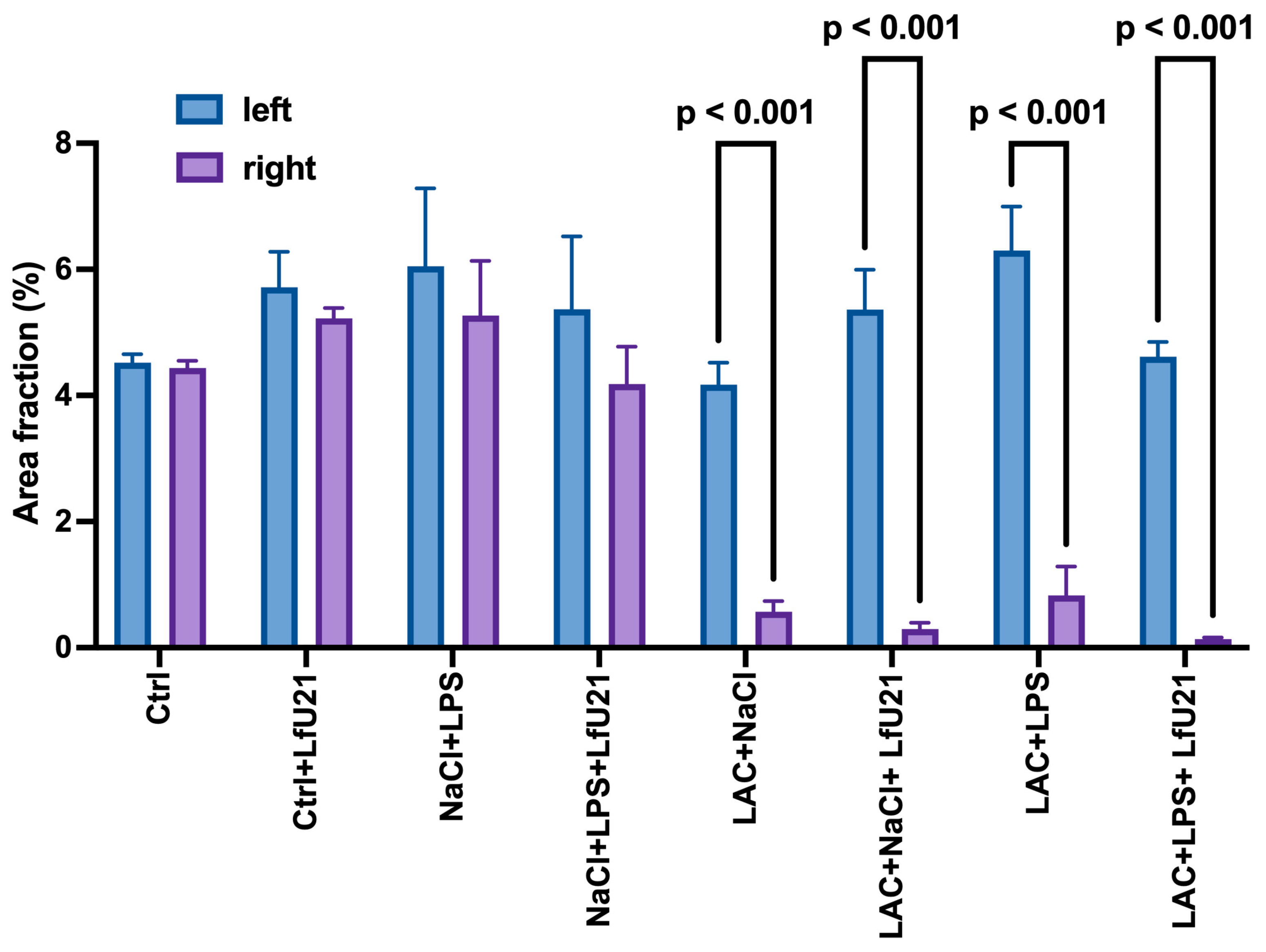

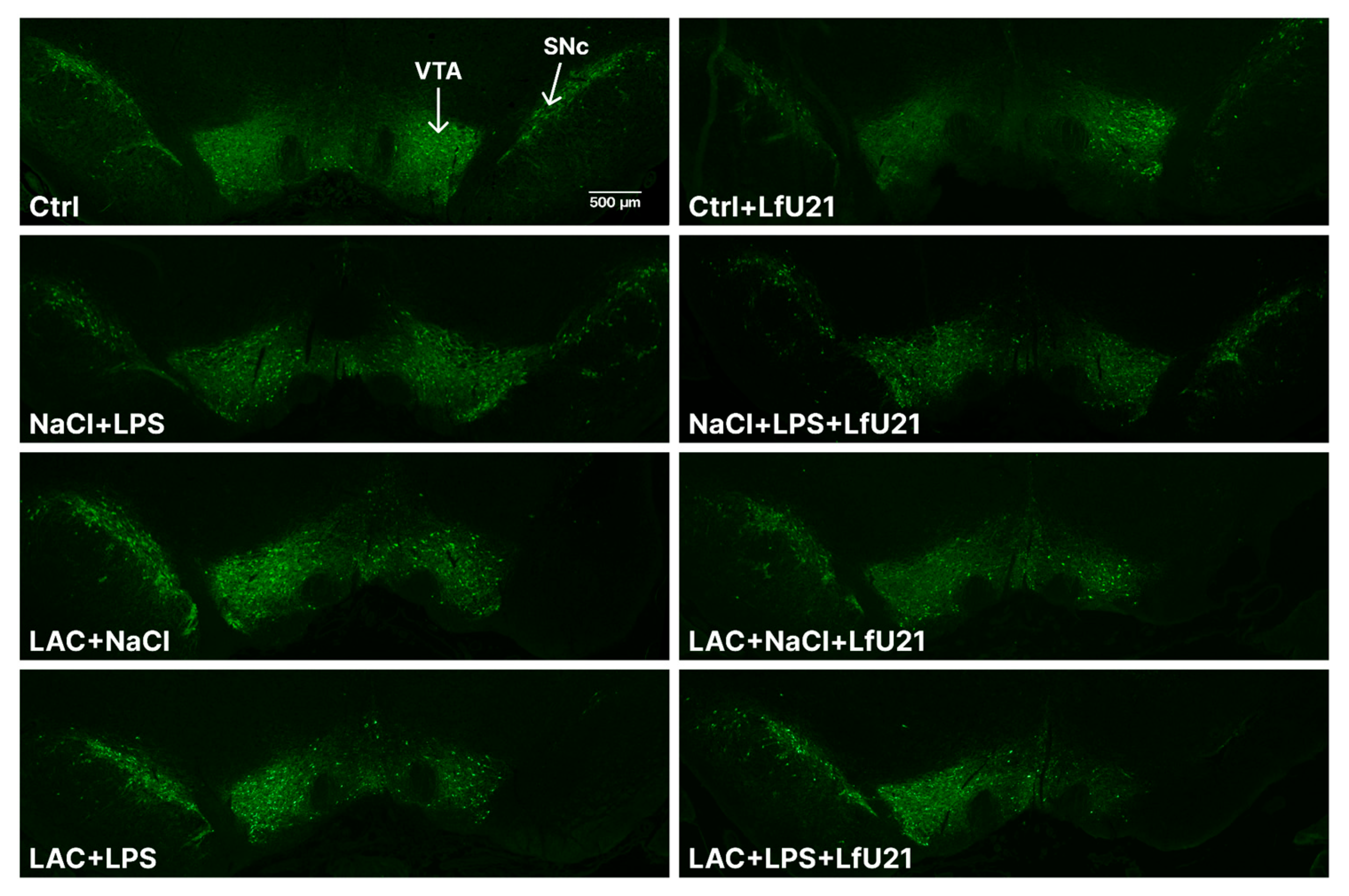

In our study, intranigral administration of lactacystin, both alone and in combination with lipopolysaccharide, caused marked degeneration of the dopaminergic system and activation of microglia in the substantia nigra pars compacta. The data obtained are consistent with the results of previous studies showing that the combined effect of a proteasome inhibitor and a systemic inflammatory stimulus (lipopolysaccharide) enhances the neurotoxic effect and reproduces key pathomorphological features of Parkinsonism, including the death of dopaminergic neurons and activation of microglia [

46]. Despite the antioxidant and potentially neuroprotective properties of LfU21, in this case, its use did not prevent the development of neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory changes. Previous studies have shown that oral administration of LfU21 can mitigate the glial response and reduce the accumulation of phosphorylated α-synuclein in a model of PD induced by the combined effects of intranigral LPS and systemic administration of paraquat, although it did not prevent the death of dopaminergic neurons [

31].

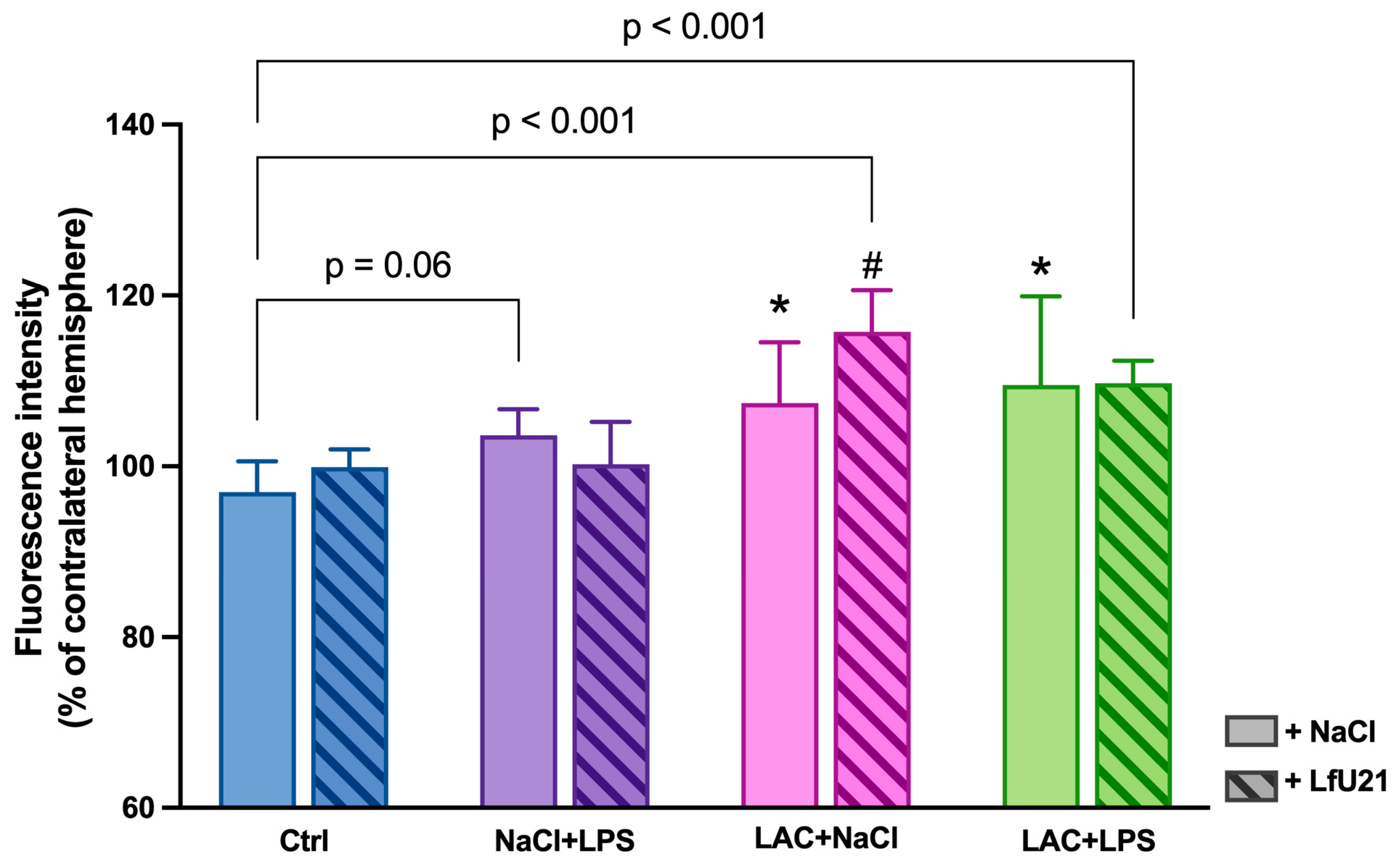

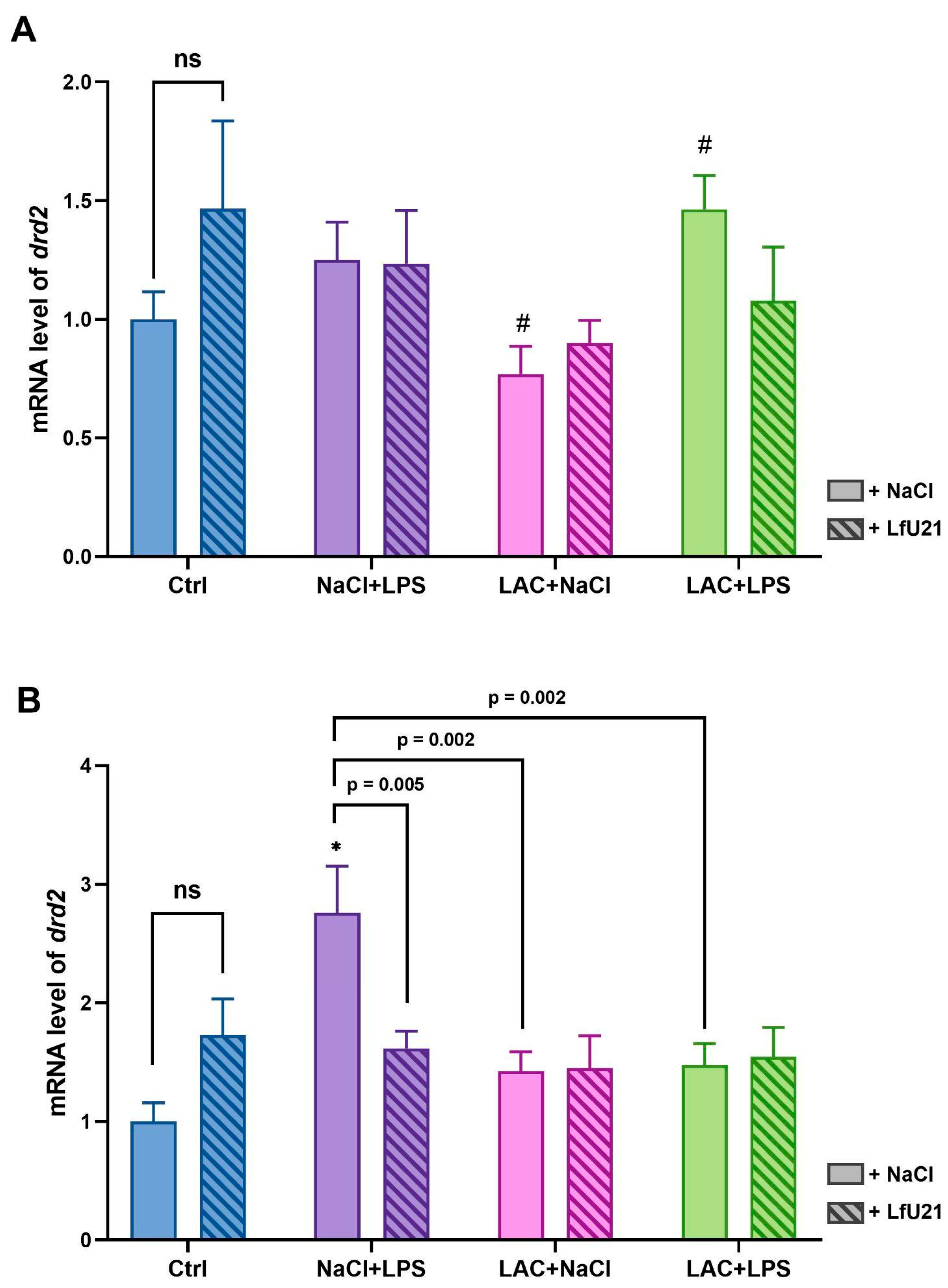

The dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) is one of five different dopamine receptors that have been identified in humans and shows high expression in both the pituitary gland and the central nervous system [

47]. DRD2 is involved in the regulation of dopaminergic signaling, motor control, and a number of cognitive processes. Mice with reduced DRD2 density show significant neuroinflammatory response and increased vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to MPTP-induced neurotoxicity [

48]. In rats with a significant deficit in dopamine release, D2 receptor levels are elevated. In addition, increased D2 receptor activity is observed in the human putamen in the early stages of sporadic PD [

49]. Thus,

drd2 gene expression may be a marker of dopamine deficiency and, importantly. As mentioned above,

drd2 receptor activation increases with dopamine deficiency in the early stages of PD, which we observe in our study: in the right hemisphere of rats receiving LPS, the level of

drd2 gene expression is higher compared to the control group, the combined PD model group, and the group receiving lactacystin. The effect of LPS was also noted in the left hemisphere, since the

drd2 expression level in the combined PD model group was higher compared to the group that received only lactacystin.

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a neurotrophic factor responsible for the development and survival of sympathetic, sensory, and cholinergic neurons [

39]. Degenerative diseases are almost always associated with the loss of neuronal structure and function, which may be related to insufficient synthesis and/or release of neurotrophic factors, including NGF [

50]. Studies show that NGF signaling is significantly affected in neurodegenerative brain diseases [

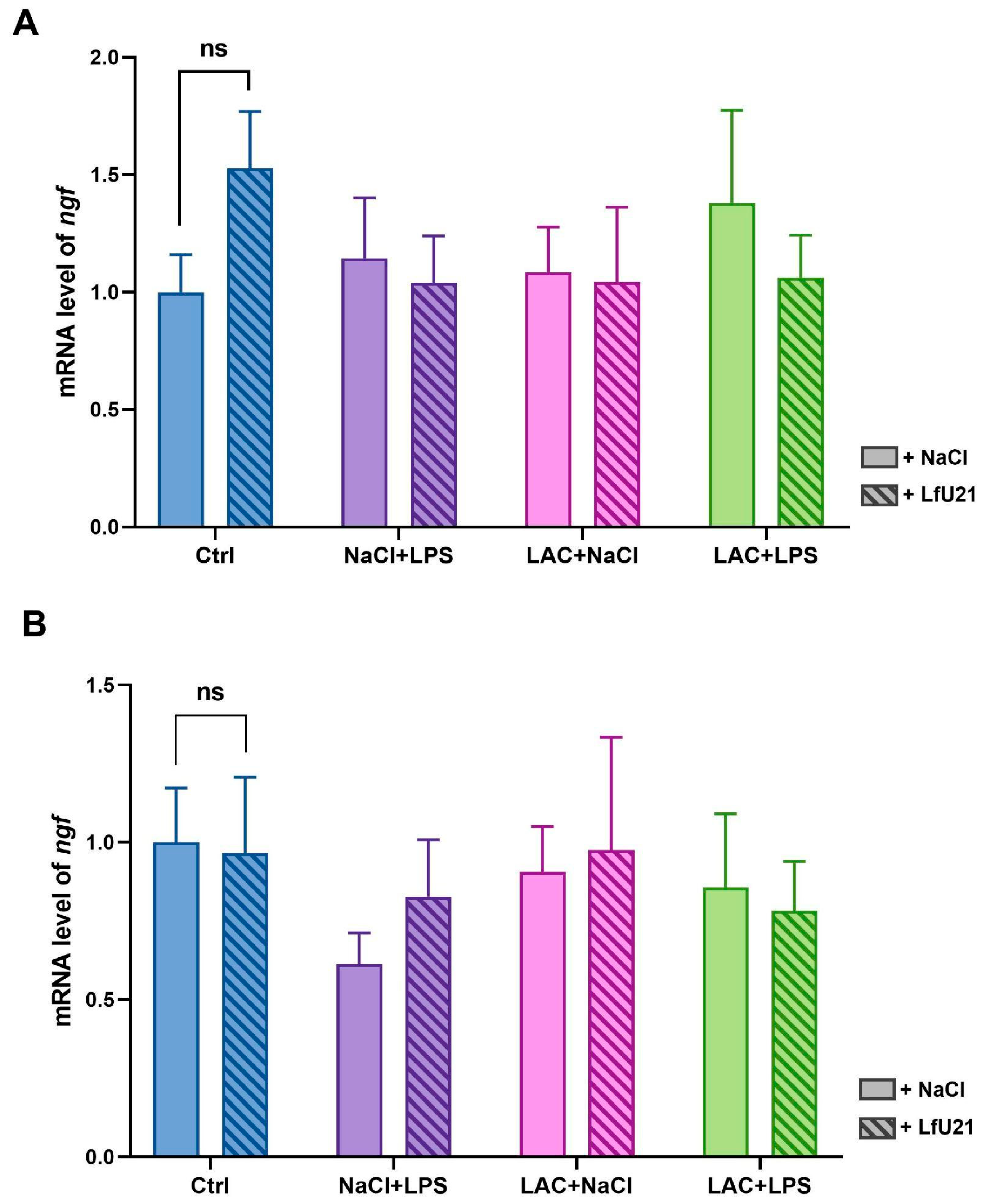

51]. However, in our study,

ngf gene expression was not altered in either hemisphere in all study groups, indicating a weak effect of the studied factors (LPS and lactacystin) on the expression of this gene.

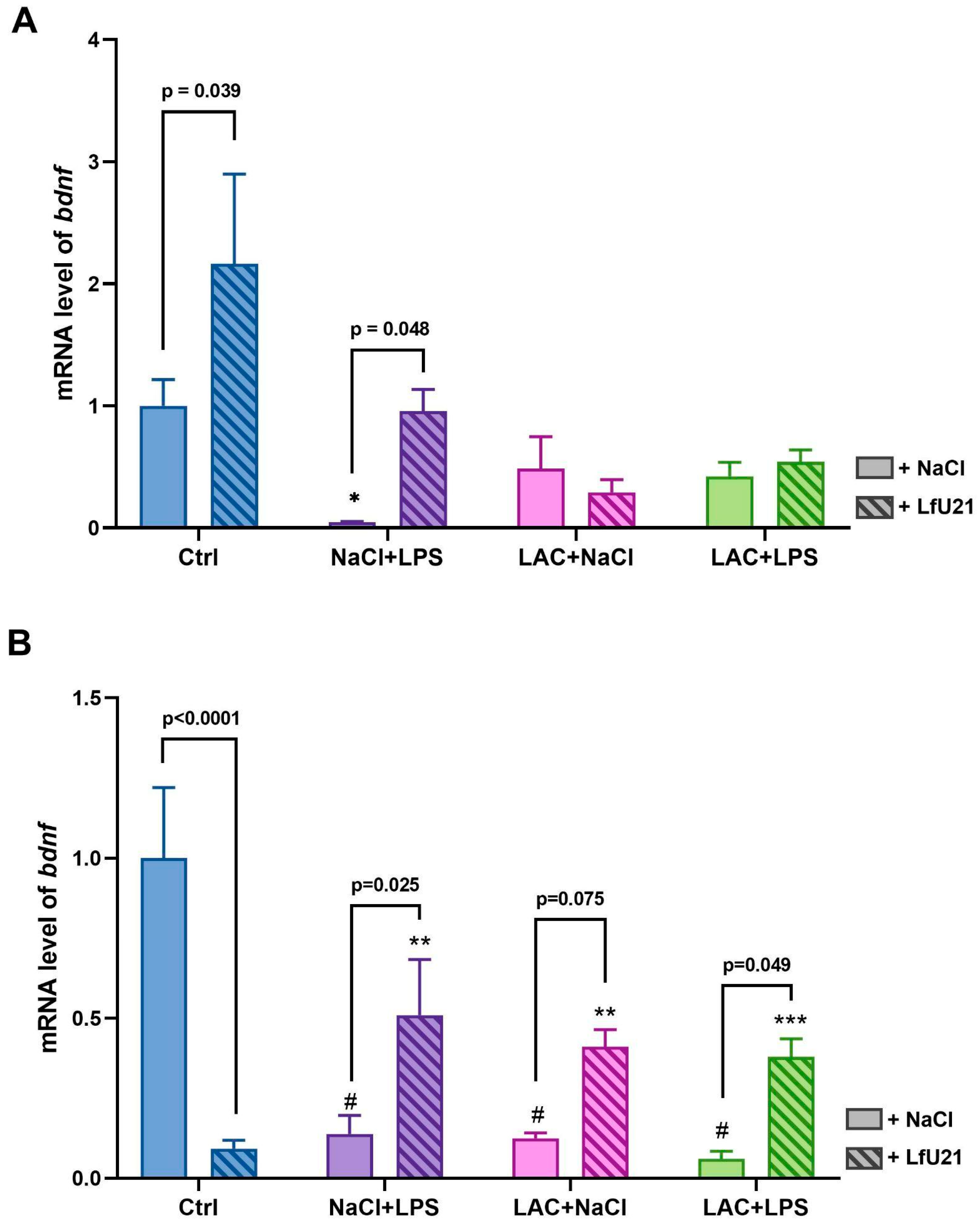

The second growth factor related to the neurotrophin family, like NGF, is BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). BDNF promotes neuron survival, maturation, synapse formation, synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis in the central nervous system [

52]. In PD, there is a decrease in BDNF levels in the nigrostriatal pathway, where the dopaminergic neurons affected by the disease are located. This decrease is associated with the progression of neurodegeneration and deterioration of motor and cognitive functions [

53]. BDNF, interacting with its receptor - neuronal receptor tyrosine kinase-2 (TrkB), contributes to the creation of the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway. This signaling pathway is reduced in neuropathology and PD [

54]. This reduction correlates positively with the severity and duration of the disease [

55]. Currently, drugs are being actively developed that activate the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway and can attenuate PD neuropathology [

37]. Thus, joint analysis of

bdnf and

trkB gene expression can contribute to the detection of the degree of pathology and, in our study, serve as an indicator of the model quality. In our work, we observe a decrease in

bdnf gene expression in both the combined PD model and when the rats were exposed to LPS and lactacystin separately, which indicates that both the combined model and separate exposure to LPS and lactacystin contribute to the simulation of the pathological condition. The drug LfU21 prevents such a strong decrease in

bdnf gene expression.

In addition, in the right hemisphere—the hemisphere where lactacystin was administered—there was a statistically significant decrease in BDNF gene expression in both the combined model and when LPS or lactacystin was administered separately. In the left hemisphere, a statistically significant decrease in BDNF gene expression was observed only in the group receiving LPS alone. Thus, we established different effects of the studied substances on the right and left hemispheres. The effect of the drug LfU21 also turned out to be multidirectional and different in the hemispheres: in the left hemisphere, the drug leads to a statistically significant increase in BDNF gene expression, while in the right hemisphere, a statistically significant decrease in this indicator is observed. Thus, LfU21 probably involves different PAIs and different mechanisms when acting on the right and left hemispheres of the brain. The identification of PAIs and their mechanisms of action is undoubtedly of significant fundamental interest. In addition, there is a difference between the expression of the

bdnf gene in the right and left hemispheres of control animals: gene expression is higher in the right hemisphere than in the left, which has been noted in other studies [

56]. BDNF is directly involved in BDNF/TrkB signaling, which, according to the literature, is reduced in PD [

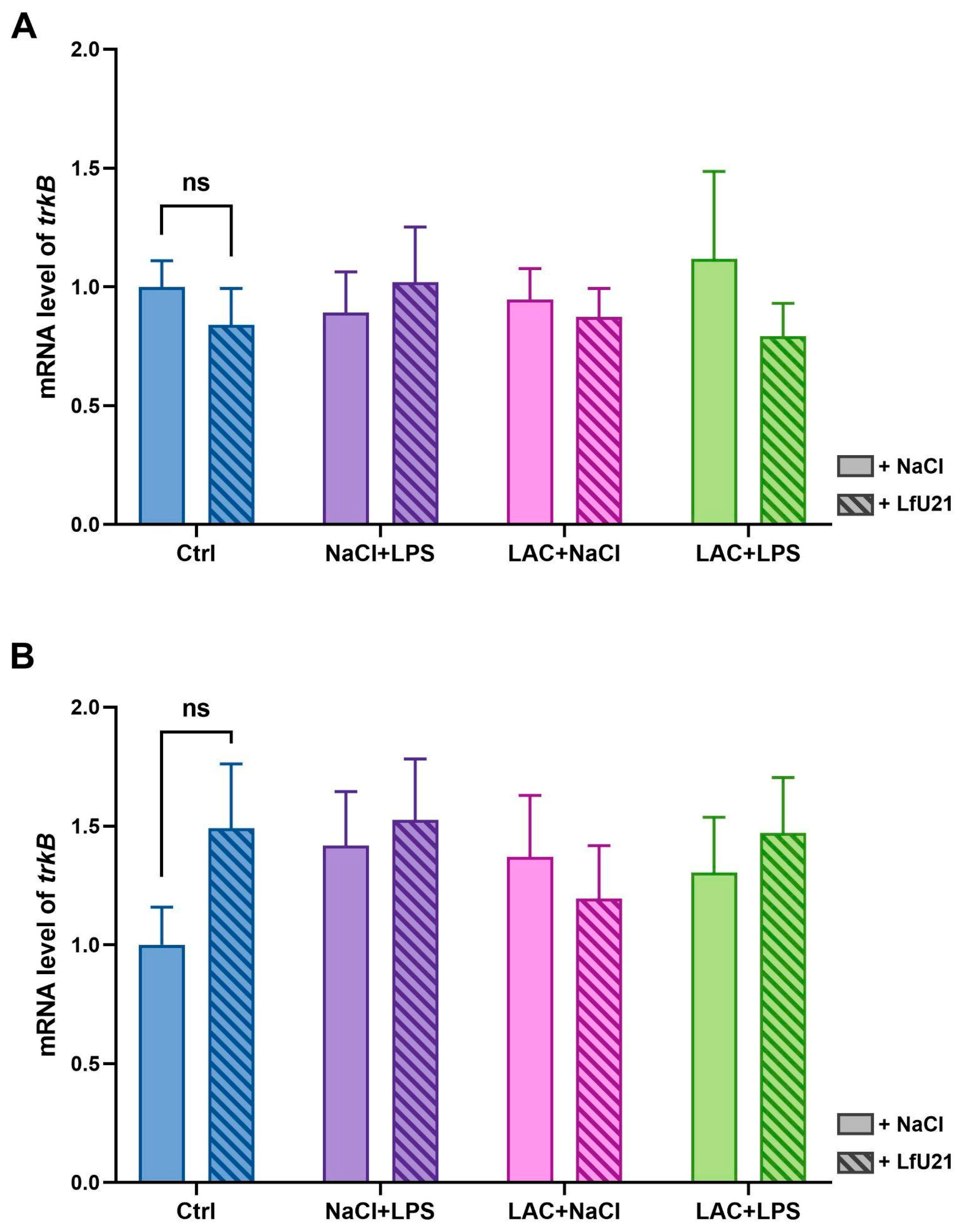

37]. In our study, we found that the expression level of the

trkB gene remained unchanged in all experimental groups. This suggests that in the combined PD model studied, BDNF/TrkB signaling is most likely limited by a decrease in

bdnf gene expression, but not

trkB.

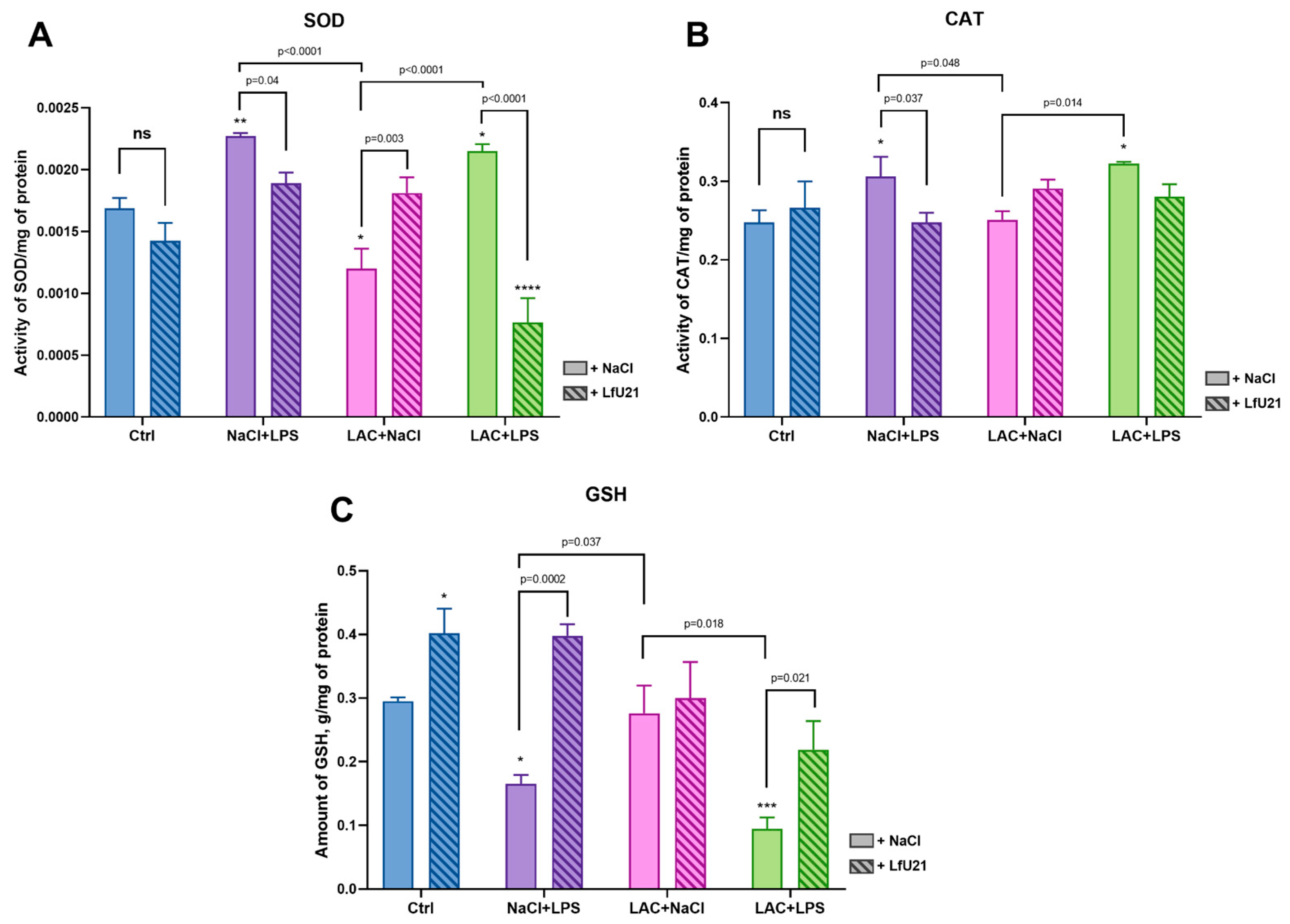

It is known that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are key mediators of various neurological disorders. LPS causes neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration mediated by LPS-induced reactive oxygen species and, consequently, oxidative stress [

57,

58]. Indicators of oxidative stress levels are oxidative stress markers, primarily superoxide dismutase (SOD), reduced glutathione (GSH), and catalase (CAT) [

59]. The presence of oxidative stress is expressed in increased levels of SOD and CAT activity and decreased GSH content.

Glutathione is an important antioxidant that exists in cells in two forms: reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG). The ratio of these forms is an important indicator of the redox state of the cell and plays a key role in protecting cells from oxidative stress by neutralizing free radicals and absorbing O

2, H

2O

2, and LOOH. GSH is a substrate for enzymes necessary for the degradation of hydrogen peroxide. Glutathione is involved in detoxification and metabolism, providing protection against damage caused by toxins and inflammation [

60]. According to various studies, GSH levels decrease during both short-term and long-term oxidative stress [

61,

62]. The experiments showed a significant decrease in GSH content in the NaCl+LPS and LAC+LPS groups. LfU21 prevented the decrease in GSH in the NaCl+LPS+LfU21 and LAC+LPS+LfU21 groups compared to the corresponding groups without the drug. The most significant positive effect of LfU21 was observed in the LAC+LPS+LfU21 group compared to LAC+LPS. The administration of LfU21 increases the GSH level relative to the control group, but no significant changes were found in the LAC+NaCl+LfU21 group compared to LAC+NaCl (where no decrease in GSH was observed).

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) plays an important role in the balance of oxidation and antioxidation in vivo. SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, which prevents damage to cells by superoxide anions. When oxidative stress occurs, SOD activity increases, but during prolonged oxidative stress, SOD activity decreases [

63]. In experiments, SOD levels were elevated in the NaCl+LPS and LAC+LPS groups, indicating a response to oxidative stress. The drug LfU21 prevents an increase in SOD activity in the NaCl+LPS+LfU21 and LAC+LPS+LfU21 groups without affecting enzyme activity in the control group.

Catalase (CAT) is an enzyme capable of effectively decomposing hydrogen peroxide and is a binding enzyme with iron porphyrin. Catalase activity increases with increased oxidative stress and decreases with decreased oxidative stress [

64]. The experiments showed an increase in CAT activity in the LAC+LPS and NaCl+LPS groups. In the NaCl+LPS+LfU21 group, the drug normalized CAT activity to the level of the control group, while in the LAC+LPS+LfU21 group, the effect was less expressed. The administration of LfU21 did not change CAT activity in the Ctr+LfU21 group compared to the control. According to the results of a study of biochemical markers in the liver of rats, the drug LfU21 contributes significantly to the normalization of antioxidant enzyme and glutathione levels in groups that received LPS intraperitoneally.

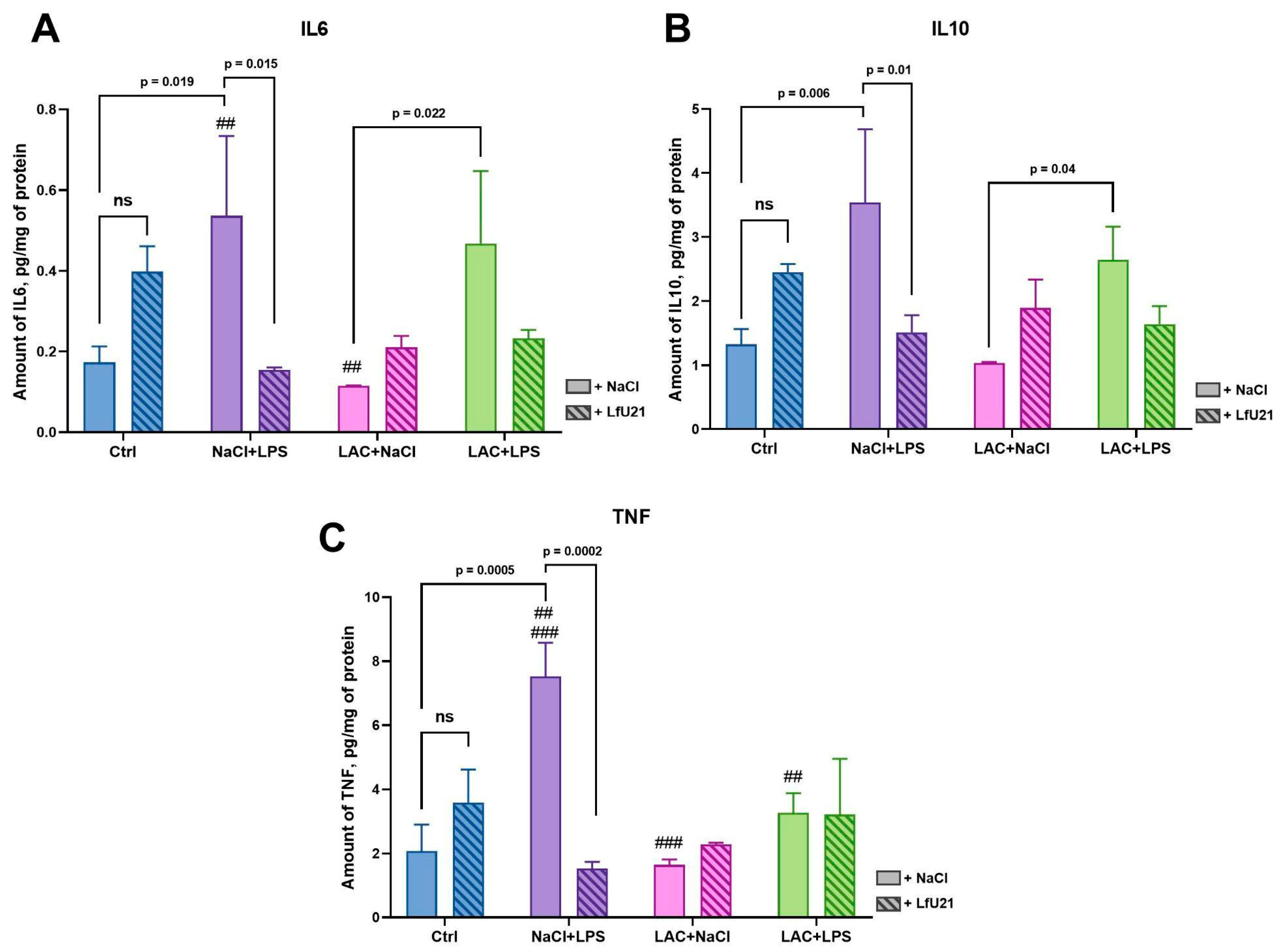

Balanced immune system function plays an important role in the pathogenesis of PD. Changes in innate and adaptive immunity underlie central and peripheral inflammation. Cytokines are key modulators of the immune response, controlling both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses [

65]. According to many studies, there is upregulation of both TNF and IL6 in the cerebrospinal fluid, brain tissue, and peripheral blood of patients with PD [

66,

67,

68]. Also, IL6 levels in the blood correlate with the severity of PD [

69]. The level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 is also elevated in the blood serum in PD and correlates with clinical indicators of gastrointestinal dysfunction in patients [

70]. Since the liver plays a central role in the perception of systemic inflammation and the response to it, in our study we investigated the content of cytokines specifically in the liver, which is explained by the more accurate level of detection in the ELISA method used [

71]. In our study, we found increased levels of both pro-inflammatory (TNF, IL6) and anti-inflammatory (IL10) cytokines in the livers of rats in the LPS-treated group, which correlates with existing studies [

72,

73]. The drug LfU21 prevents an increase in the expression of the cytokines studied in the group receiving LPS, which indicates its significant immunomodulatory properties. In addition, differences in IL6 and IL10 levels in the liver were observed between the combined model groups and the group receiving lactacystin, which also indicates a significant effect of LPS on the levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. LPS as a single substance leads to stronger TNF activation than in combination with lactacystin. The mechanisms of this antisynergism require further study.

It is believed that one of the triggers leading to the development of PD is a form of intestinal microbiome dysbiosis and the accumulation of pathogenic bacteria capable of producing various toxins and LPS [

8]. This leads to damage to the intestinal epithelial barrier and an increase in blood LPS levels [

74]. The effect of LPS on the tissues of the intestine itself leads to the development of inflammation in it, which, in turn, leads to an increase in the expression of α-synuclein in the structures of the enteric nervous system [

74].

One of the morphological signs of inflammation in the intestine is an increase in the number of goblet cells in the epithelium and an increase in the amount of mucus they produce. In our study, the number of goblet cells in the epithelium of intestinal villi increased in the groups treated with LPS, LAC, and LPS+LAC. The mucus produced by goblet cells creates a protective layer that prevents pathogens from penetrating the epithelium [

75]. The increase in the number of goblet cells reflects the response of the epithelium to stress associated with inflammation (with systemic administration of LPS) and damage to the nigrostriatal system of the brain (with intracerebral administration of lactacystin). Experimental studies show that neurodegeneration in the nigrostriatal system can lead to morphological signs of inflammation in the intestine, including an increase in the number of goblet cells in the epithelium [

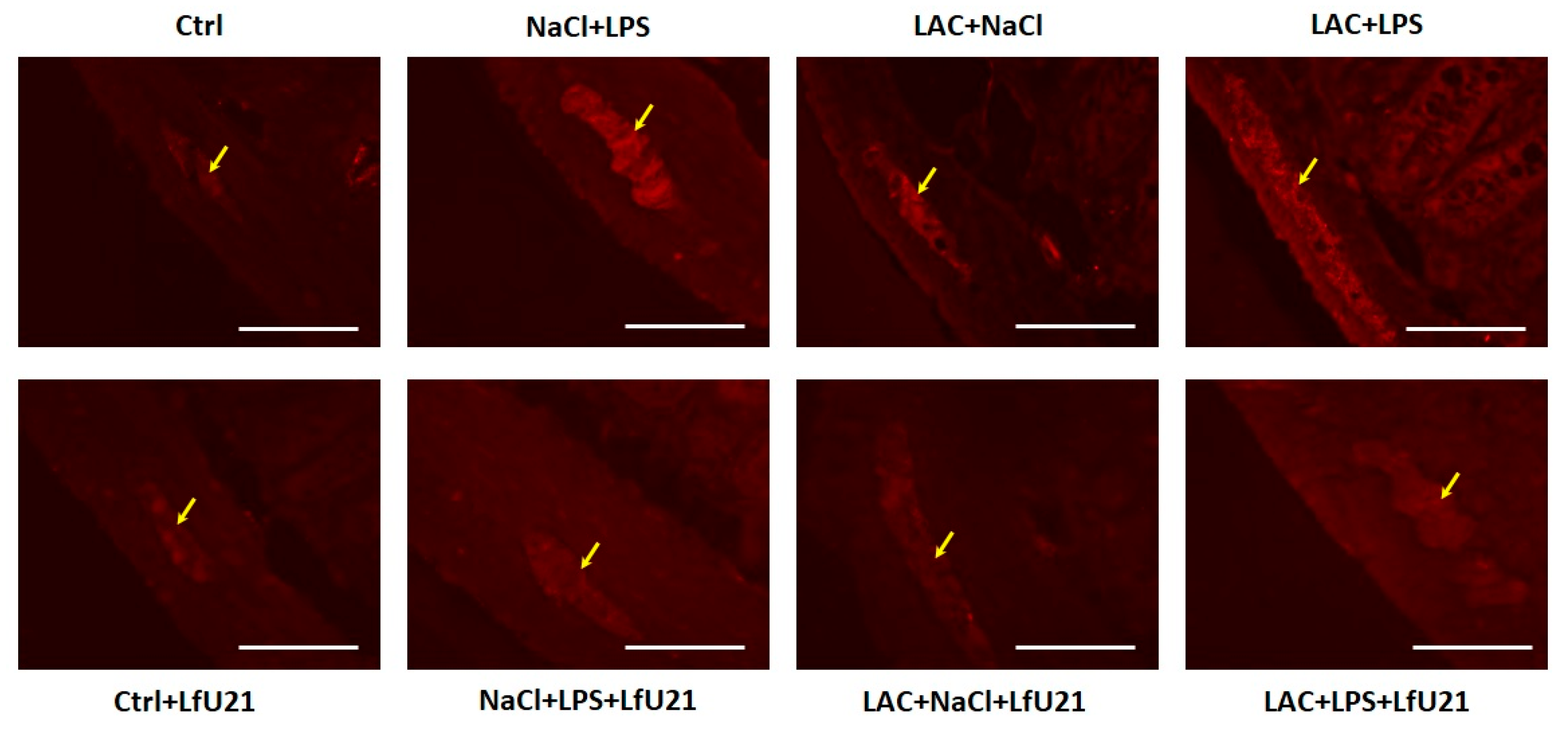

76]. In our study, an increase in the number of goblet cells in the epithelium was accompanied by an increase in the content of total and phosphorylated α-synuclein in the myenteric ganglia of the small intestine. Contrary to our expectations, the administration of LPS in combination with lactacystin did not lead to more significant phosphorylation of α-synuclein in the intestine.

Since the relationship between the gut microbiota and the development of various neurodegenerative diseases, including PD, is widely accepted and studied in the scientific community, the possibility of modulating the pathogenesis of these diseases by altering the microbiota is undoubtedly relevant [

77,

78,

79,

80]. According to the “gut-brain axis” hypothesis, the earliest changes associated with the accumulation of α-synuclein are observed in the nervous tissue of the intestine [

81]. These changes trigger the pathological process leading to neurodegeneration in the brain. According to this hypothesis, influencing the gut microbiota to reduce the accumulation of α-synuclein in the enteric nervous tissue can slow down or even stop the entire pathogenic process. In our study, we investigated the effect of the drug LfU21 on the dynamics of changes in the number of goblet cells in the epithelium and the accumulation of total and phosphorylated α-synuclein in rats treated with LPS, LAC, and LPS+LAC. Administration of LfU21 prevented an increase in the number of goblet cells in the LPS-treated rats. These results indicate a probable anti-inflammatory effect of strain U-21 in the intestine. Our results also showed the effectiveness of strain U-21 in reducing the accumulation of α-synuclein in the myenteric ganglia of the intestine, which supports its therapeutic potential in the early stages of PD.

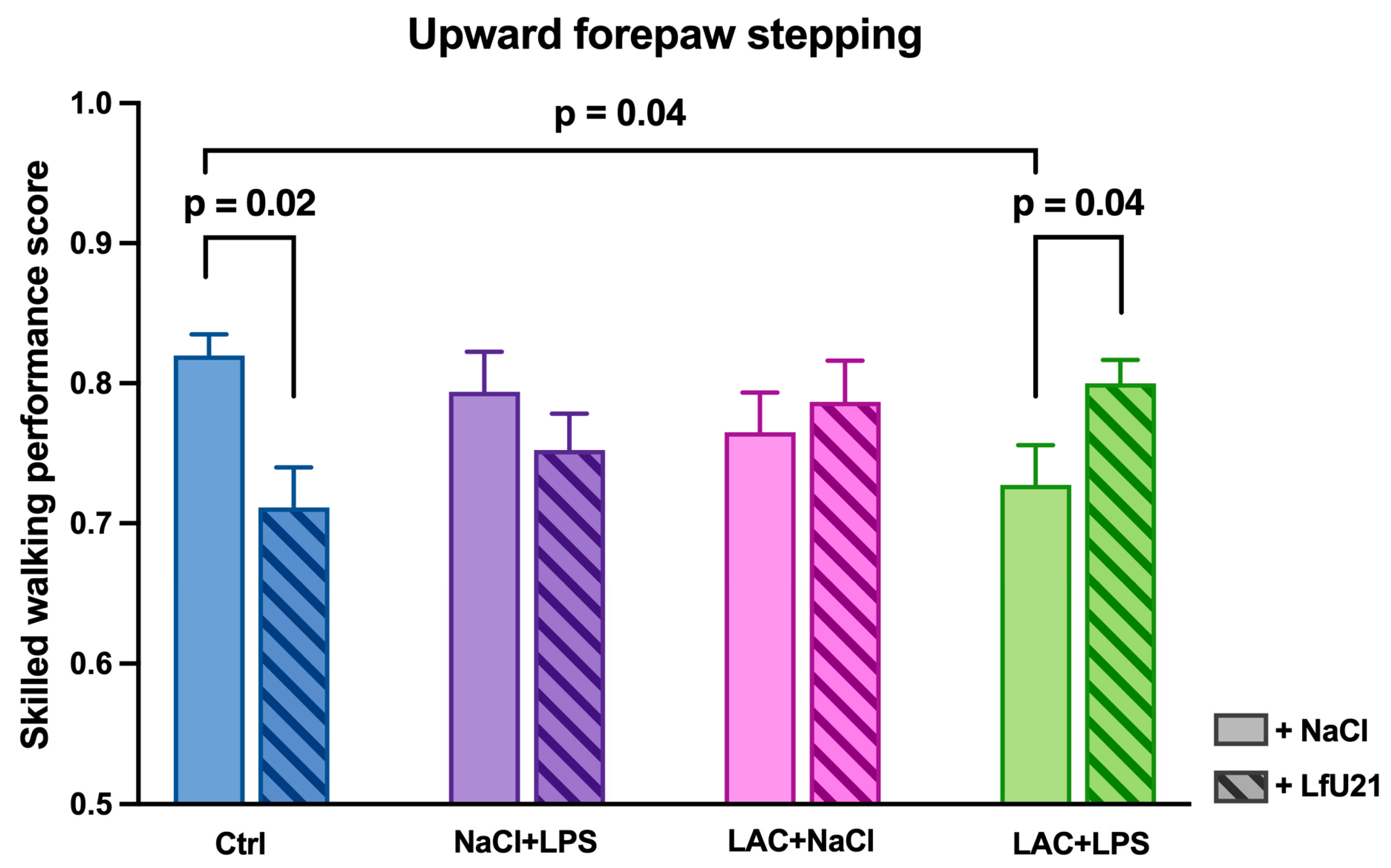

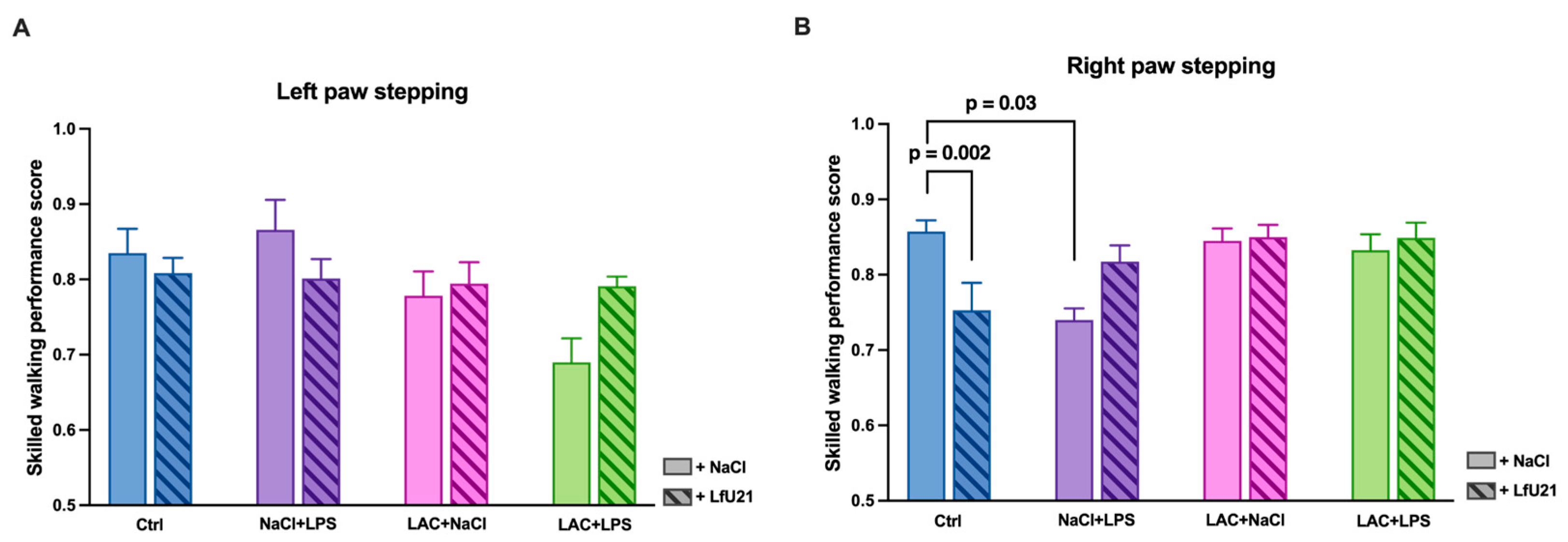

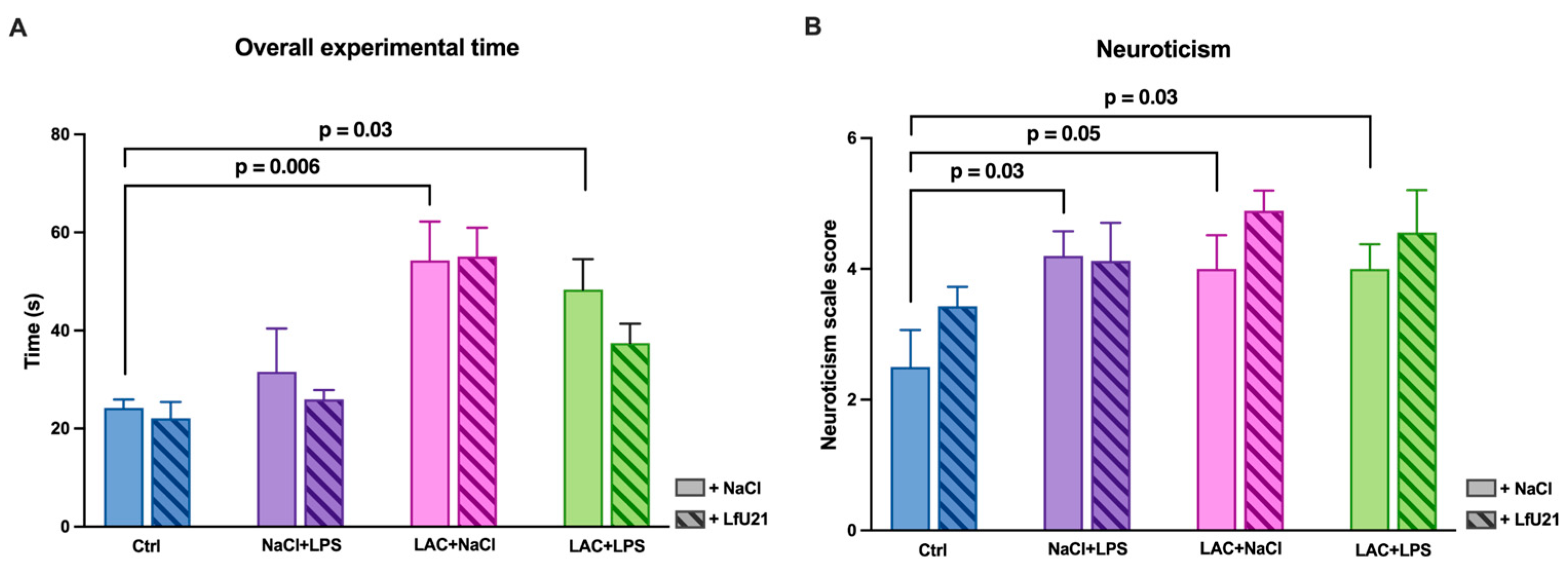

In our study, the combined effect of LPS and LAC led to motor dysfunction in the “Rung Ladder” test, manifested in a decrease in step quality and an increase in test completion time. Similar results in a similar model were previously demonstrated by Deneyer et al. [

46], who showed a decrease in the time animals remained on a rotating drum in the “Rotarod” test. At the same time, motor disorders, both with combined exposure to toxins and each component separately, were accompanied by the development of non-motor disorders, which manifested itself in the intensification of a neurosis-like state. The neuroticism of the animals was assessed on a corresponding scale. Our data are consistent with the results of other studies in which the administration of 6-OHDA caused anxiety-like behavior in rats in the elevated plus maze test [

82].

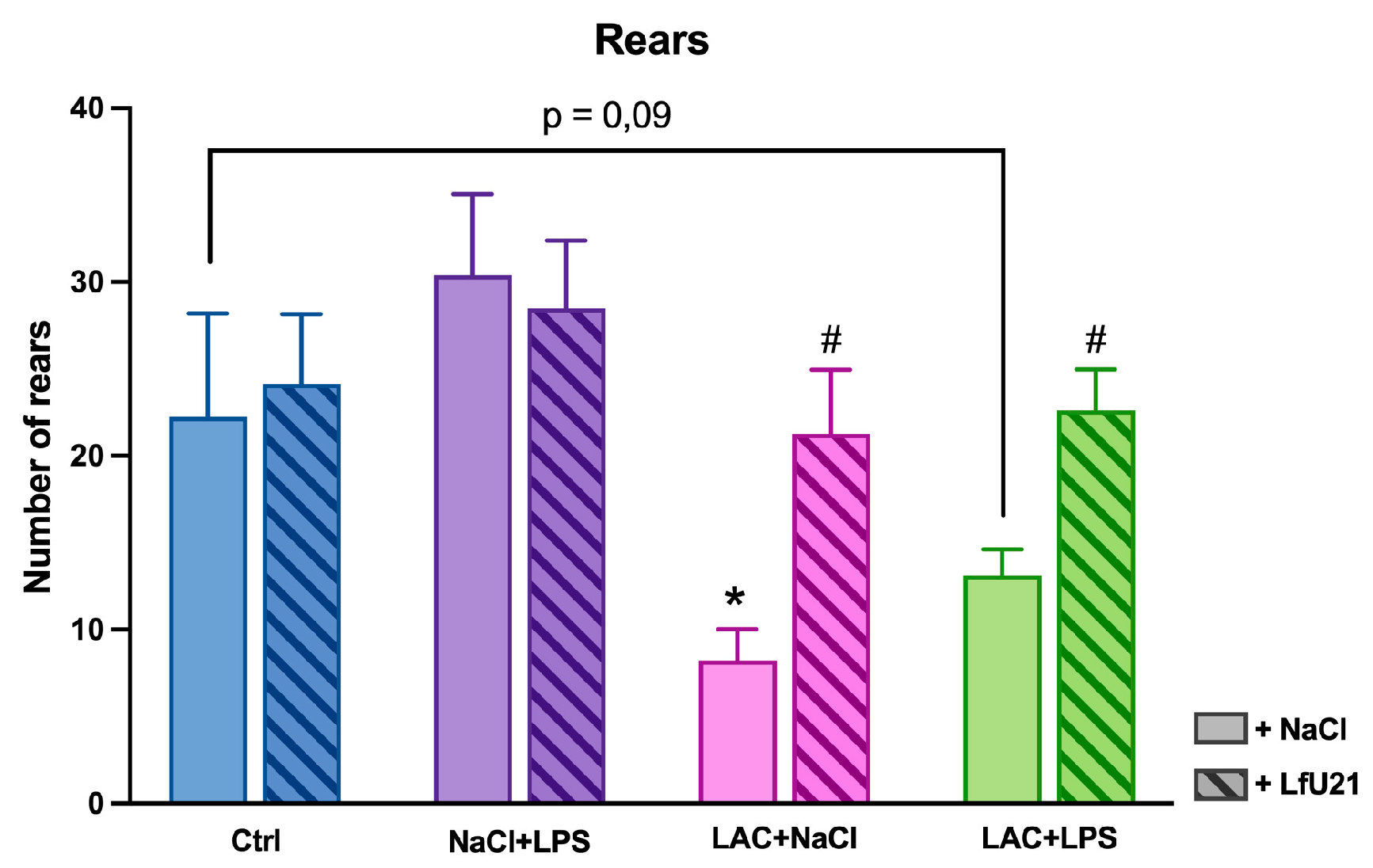

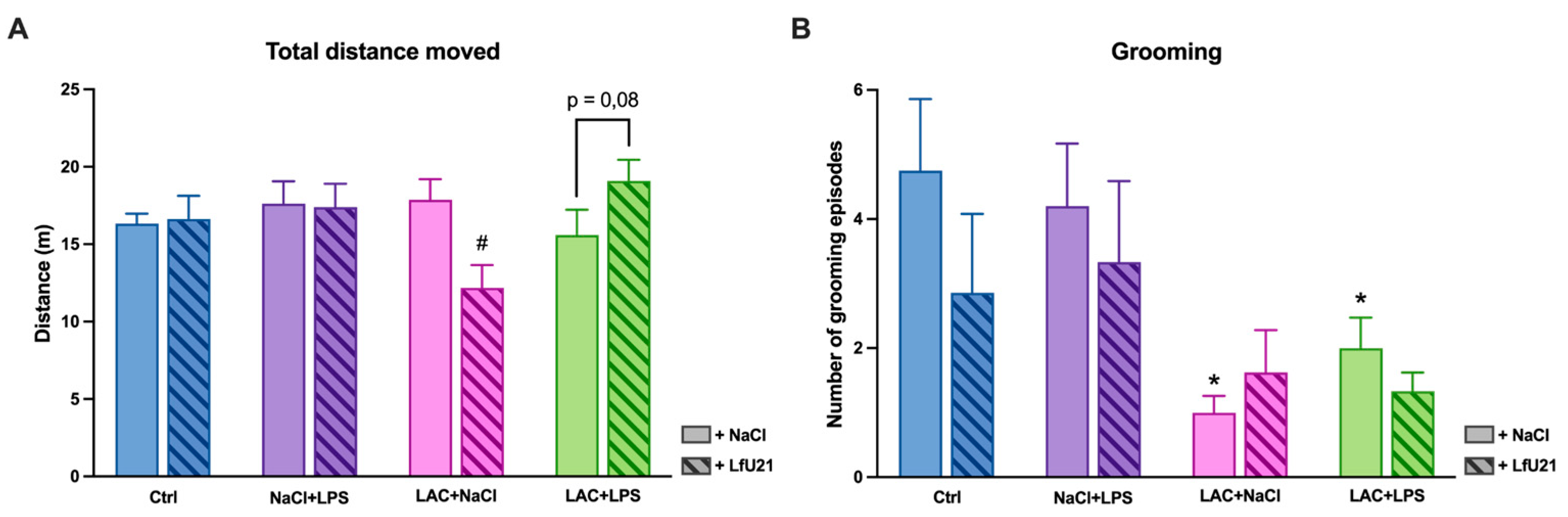

The results of the “Open field” test showed that the administration of lactacystin had the most significant effect on the manifestation of motor symptoms of PD. Animals that received only lactacystin showed a decrease in vertical motor activity and the number of grooming acts, which was apparently caused by a disruption in the nigrostriatal pathway that regulates the execution of coordinated motor patterns [

83].

The effect of LfU21 on motor disorders is multidirectional: for example, administration of the drug prevents a decline in step quality in experimental animals, whereas in control animals it worsens this indicator. These effects may be caused, in the first case, by the protective action of prolonged exposure through the modulation of inflammatory processes during the development of neurodegeneration [

84,

85,

86], and in the second case, by the induction of systemic low-grade inflammation [

87]. Thus, the modulatory effect of the drug is manifested mainly in pathological conditions and also depends on the physiological status of the host organism.

These results are consistent with previously published data. Thus, the use of various probiotics, prebiotics, or combinations thereof (

Lactobacillus salivarius AP-32,

Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis Bb12, and

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) alleviated motor impairments in rats with PD models induced by intracerebral administration of 6-OHDA or LPS in tests such as the “rotarod”, “apomorphine test”, “cylinder”, and “narrowing beam” [

88,

89].

LfU21 did not have a significant effect on the time taken to complete the “Rung Ladder” test. This may indicate that the protective effect is manifested primarily in the quality of the steps performed, rather than in the speed of task completion.

Thus, our results demonstrate that LfU21 has a protective effect on motor function in rats with a combined model of PD induced by LAC and LPS, presumably through antioxidant mechanisms and a reduction in the accumulation of α-synuclein in the intestine.

Table 1 summarizes the results of changes in the studied biomarkers obtained on the combined PD model, its components, and their correction with LfU21.

Table S1 lists the genes and proteins of the

Limosilactobacillus fermentum U-21 strain that could potentially determine its pharmacological properties, characterizing the potential anti-Parkinson's properties of the drug. The action of the substances produced by these genes can be realized in several ways: 1) by interacting with TLR epithelial cells of the intestine [

90]; 2) by directly entering the bloodstream [

91,

92,

93]; 3 3) by packaging into vesicles and transporting them [

94]. The drug LfU21 produces a number of amino acids: histidine, glycine, and arginine, which, through metabolism in the intestine, can influence processes in the brain [

95,

96,

97]. In addition, the drug produces ATP-dependent Clp protease, which has proven disaggregating properties, and a number of proteasomes (Zinc metalloprotease HtpX, ATP-dependent zinc metalloprotease FtsH), which may be involved in the processes of reducing α-synuclein content in the intestine [

98]. LfU21 produces proteins of the thioredoxin complex, which is responsible for antioxidant potential [

99].

Identifying and refining the mechanisms of PAIs presented in

Table S1 that cause the correction of specific PD biomarkers at various stages of the disease is a necessary and difficult process for the advancement of any LBP aimed at treating a specific nosology, in this case PD.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain

The strain Limosilactobacillus fermentum U-21 (NCBI Reference Sequence NZ_CP103293.1), belonging to the collection of the Laboratory of Bacterial Genetics of the Vavilov Institute of General Genetics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, was isolated from the feces of an astronaut. The strain was deposited in the All-Russian Collection of Industrial Microorganisms under the number B-12075.

4.2. Culture Media, Growth Conditions and Lyophilization

Limosilactobacillus fermentum U-21 was cultivated in an industrial-type culture medium developed by our laboratory under controlled fermentation conditions. The production medium contained: 75% whey obtained from 12% skimmed milk powder, 7% lactopeptone, 2% yeast extract, 2% inulin, 0.002% ascorbic acid, 0.05% sodium chloride, 0.005% manganese sulfate, and 0.02% magnesium sulfate. Cultivation was carried out in laboratory fermenters (Prointech, Russia) at a temperature of 37 °C and a stirring speed of 100 rpm, without aeration; the initial pH of the medium was 6.8. The production medium was inoculated with 2% (v/v) of the seed material obtained after sequential cultivation of the strain on MRS agar medium (HiMedia, India) and subsequent growth in MRS liquid medium. MRS liquid medium contains proteose peptone 10 g/L, beaf extract 10 g/L, yeast extract 5 g/L, dextrose 20 g/L, tween-80 1 g/L, ammonium citrate 2 g/L, sodium acetate 5 g/L, magnesium sulfate 0.1 g/L, manganese sulfate 0.05 g/L, sodium hydrophosphate 2 g/L. In MRS solid agar medium, the composition is identical to the liquid medium except for the replacement of sodium hydrophosphate with potassium hydrophosphate 2 g/L, and the addition of agar-agar 12 g/L.

For lyophilisation, the 20-h culture (3х109 CFU/mL) was centrifuged at 7000g at 4 °C for 10 min, then washed with PBS buffer (potassium dihydrophosphate 1.7 mM, sodium dihydrophosphate 5.2 mM, sodium chloride 150 mM, pH = 7.4), resuspended in lyophilisation medium (10% sucrose, 1% gelatin). The mixture was kept at -20 °C for 24 hours and then dried at -52 °C and 0.42 mbar pressure for 72 hours on a Labconco 2.5 lyophilic dryer (Labconco, USA). The obtained lyophilisates were stored at 4 °C. Their viability and titre were checked before use in the experiment.

4.3. Animal Collection and Maintenance

All experiments were conducted in compliance with appropriate bioethical standards for working with laboratory animals, including the possible reduction in the number of animals used. The studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Russian Center of Neurology and Neurosciences (protocol No. 2-4/25 dated February 17, 2025).

The study was conducted on male Wistar rats (n=82) at the age of 3.5 months, with a body weight of 300-350 g at the start of the experiment.

Manipulations with animals were carried out in accordance with Recommendation No. 33 of the Board of the Eurasian Economic Commission dated November 14, 2023 “On Guidelines for Working with Laboratory (Experimental) Animals in Preclinical (Non-Clinical) Studies,” as well as guided by the “Rules for Working with Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits” (GOST 33216-2014). The animals were kept in standard vivarium conditions, with free access to food and water, under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Prior to the start of the experiment, the animals were kept in quarantine for 14 days.

4.4. Surgical Operations and Experimental Design

For stereotactic operations, animals were placed on a laboratory stereotaxis frame (RWD, PRC), the scalp was incised, and trepanation holes were drilled in the skull using a portable drill to access specific brain structures according to the coordinates of the rat brain atlas [

100]. When placing animals in stereotaxis, a cotton-gauze mattress was placed between the animal and the work surface to prevent hypothermia during the operation.

The lactacystin (LAC) solution (ENZO, Switzerland) (4 μg in 3 μl of saline solution) was administered once into the substantia nigra pars compacta of the brain of rats on the right side (n=43) in accordance with the coordinates of the Paxinos rat brain atlas: (AP = –4.8; L = 2.2; V = 8.0). The same volume of saline was injected into the left side. Sham-operated (control) animals (n=39) received bilateral injections of 3 μl of saline. Intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of LPS solution from Escherichia coli O111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at a dose of 1 mg/kg was started 3 days after the administration of lactacystin and was performed twice a week for 4 weeks, for a total of 8 injections, with a volume of 0.25 ml. The pharmabiotics

L. fermentum U-21 (1.5x10

10 CFU) were diluted in 3 ml of saline solution and administered orally (per os), starting 2 days after surgery, at a daily dose of 0.3 ml of solution [

24].

The experimental animals were divided into 8 groups: 1) sham-operated animals with i.p. and per os administration of saline solution (“Ctrl”, n=9), 2) sham-operated animals with i.p. administration of saline and per os administration of pharmabiotic (“Ctrl+LfU21”, n=9), 3) rats with lactacystin injection and i.p. and per os administration of saline (“LAC+NaCl+NaCl”, n=11), 4) rats with lactacystin injection, i.p. administration of saline, and per os administration of LfU21 (“LAC+NaCl+LfU21”, n=10), 5) sham-operated rats with i.p. administration of LPS and per os administration of saline (NaCl+LPS+NaCl, n=11), 6) sham-operated rats with i.p. administration of LPS and per os administration of LfU21 (NaCl+LPS+LfU21, n=10), 7) rats with lactacystin injection, i.p. administration of LPS, and per os administration of saline (“LAC+LPS+NaCl,” n=11), 8) rats with lactacystin injection, i.p. administration of LPS, and per os administration of LfU21 (“LAC+LPS+LfU21”, n=11).

The animals were removed from the experiment two months after stereotactic surgery to measure the studied parameters (

Figure 20).

4.4. Analysis of Behavioral Activity

In order to identify the development of neurotoxins (lactacystin and LPS), the behavior of animal biomodels was tested at intervals determined by the experimental design (8 weeks after stereotactic surgery). The tests used in the study were the “Rung Ladder” test [

101] and the “Open Field” test [

102].

The “Rung Ladder” test is used to assess motor function and coordination in rats and mice. The test evaluates the number of correct paw placements on the rungs and the number of slips and misses when placing the paw (in points), followed by the calculation of the Skilled walking performance score (SWPS), as well as neuroticism [

103] and test completion time [

104]. A more complex version of the test involves gaps in the bars, which are used to assess coordination between the front and hind limbs (OpenScience, Russia).

Motor disorders were assessed in the “Open Field” test. The setup consists of a 78x78x40 box made of rigid PVC, and the test lasts 3 minutes.

Recording and subsequent analysis of behavioral indicators were performed using the Any-Maze video surveillance system (Stoelting Inc., USA) with software.

4.5. Transcription Analysis

4.5.1. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription Reaction

After the end of the experiment, three individuals were taken from each experimental group. The rats were decapitated using a guillotine, and the striatum samples on ice were placed in IntactRNA (Eurogen, Russia) and subsequently stored according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was isolated from striatum tissue using ExtractRNA reagent (Eurogen, Russia) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Extracted RNA was dissolved in water without nucleases (Eurogen, Russia). To analyze the quality of the isolated RNA, gel electrophoresis was performed. After the RNA was isolated and its quality was checked, additional processing was carried out. The samples were processed with DNase I (diaGene, Russia) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The reverse transcription reaction was performed using the MMLV RT kit (Eurogen, Russia) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

4.5.2. Real-Time qPCR

The reaction mixture was prepared using the qPCRmix-HS SYBR kit (Eurogen, Russia) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. qPCR was performed on a CFX96 device (Bio-Rad, USA). The amplification program was carried out as follows: melting – 5 minutes, 95 °C, denaturation – 30 seconds, 95 °C, annealing – 30 seconds, 57,6 °C (for

drd2 gene), 64 °C (for

ngf gene), 54,7 °C (for

bdnf gene), or 62°C (for

trkB gene) elongation – 30 seconds, 72 °C. The last three steps were repeated cyclically 40 times, then a DNA melting curve was obtained. To analyze the qPCR data, the CFX Manager V 3.1 program (Bio-Rad, USA) was used. The relative normalized expressions in three biological replicates (three independent individuals per point) were calculated as ∆∆Cq, the

actb household gene was taken as the reference [

105]. The primers were selected using primer-BLAST [

106] (

Table A1).

4.6. Markers of Redox Potential Analysis

A rat liver sample was homogenized in liquid nitrogen and placed in a PBS (0.01M pH7.4) 1v/10v buffer cooled to +4 °C, vortexed and centrifuged at 10000g for 10 minutes to remove undissolved particles. An undiluted solution was used to measure the GSH content, and to determine the activity of CAT and SOD, the solution was diluted 10 times. The SOD activity, CAT activity, the content of reduced glutathione (GSH) were measured using a colorimetric method using a commercial kits (E-BC-K031-S, Elabscience, China; IS104(A001-1-2), Cloud-Clone Corp., China; E-BC-K030-S, Elabscience, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.7. The Study of the Immunomodulatory Activity of the Strain Using ELISA

Rat liver samples were homogenized in a fresh lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1% NP-40) with a glass homogenizer on ice. Then, ultrasound treatment with the Vibra Cell device (Sonics, Newtown, CT, USA) was performed. The program was set as follows: amplitude 40%, 5 s working mode, 10 s rest, 15 cycles. Then, centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C was performed. The supernatant was collected into new tubes, and the protein concentration in the samples was measured using a Qubit fluorimeter (Invitrogen, USA). Commercial ELISA kits were used to determine the quantitative content of cytokines in rat liver (HEA133Ra, HEA079Ra, HEA056Ra, Cloud-Clone Corp., China). Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a Multimode Detector DTX 880 reader (Beckman Coulter, USA).

4.8. Histological Preparations and Analysis

4.8.1. Morphometric Study of the Substantia nigra pars compacta

For morphological examination, decapitation was performed using a guillotine, the brain was removed and fixed for 24 hours in 10% formalin. Frontal sections 10 μm thick were prepared using a Tissue-Tek Cryo3 Flex cryostat (manufactured by Sakura FineTek®, USA). Thermal unmasking of antigens was performed in a steam cooker for 15 min (citrate buffer, pH 6.0). The sections were incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies in a humid chamber for 18 h at room temperature.

To detect tyrosine hydroxylase, monoclonal rabbit antibodies (1:250, ab137869, Abcam, UK) and secondary polyclonal antibodies to rabbit immunoglobulins (1:250, goat, Anti-Rb, CF488, SAB4600045-250UL (Sigma)). To detect microglia, monoclonal rabbit antibodies to the IBA1 (ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1) protein (1:300, ab178847, Anti-IBA1 Rb (abcam)) and secondary polyclonal antibodies to rabbit immunoglobulins (1:250, goat, Anti-Rb, CF488, SAB4600045-250UL (Sigma)). The sections were counterstained with DAPI. For the study, 5-6 consecutive sections (selected approximately every 50 μm) of substantia nigra were selected in the area of intranigral lactacystin administration. For quantitative assessment, the region of interest (the compact and reticular parts of the substantia nigra on the left and right) was manually selected in ImageJ ver. 1.54p (NIH) from images obtained with the same microscope lighting settings (Nikon SMZ-18). The staining intensity of IBA1 was evaluated in the selected area. Similarly, by selecting the area of interest and using the Bernsen threshold segmentation algorithm, the areas stained for tyrosine hydroxylase (neuron bodies and their processes) were segmented in the substantia nigra, and the area fraction of immunostained tissue was evaluated.

4.8.2. Morphometric Study of the Small Intestine

4.8.2.1. Immunofluorescence Staining for Total and Phosphorylated α-Synuclein in the Ganglia of the Myenteric Plexus of the Small Intestine of Rats Wistar

For immunomorphometric analysis, six animals were selected from each group. Sections of the small intestine approximately 10 cm long were excised at a distance of 30-40 cm from the pylorus and fixed in formalin for 24 hours. They were then cut crosswise into 3 mm thick pieces, impregnated with a 30% sucrose solution, then with Tissue-Tek O.C.T. (“Optimal cutting temperature”) Compound (Sakura Finetek, Japan) cryoblock reagent, and cut on a cryostat into 10 μm thick sections. Immunofluorescence reactions were performed using an indirect method, with primary antibodies to total α-synuclein (Rb, Sigma, 1:300) and α-synuclein phosphorylated at serine-129 (Ms, Abcam, 1:250) and secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse CF488, Sigma, 1:250 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa fluor 594, Abcam, 1:250). The preparations were examined and photographed under a Nikon Eclipse NiU microscope with a Nikon DS-Qi digital camera at 40x magnification with the same microscope lighting system settings. Morphometry was performed using ImageJ software on photographs, with at least 30 fields of view per animal examined. The content of total and phosphorylated α-synuclein in the myenteric (intermuscular) ganglia was assessed indirectly by measuring the average intensity of fluorescent staining for these markers in the myenteric ganglia, the area of which was manually selected in the photographs, with correction for background staining.

4.8.2.2. Goblet Cells Count

To estimate the number of goblet cells in the epithelium, cryostat sections of the small intestine were stained with Alcian blue and counterstained with hematoxylin, then photographed at 25x magnification. The number of goblet cells per 100 μm of intestinal villi length was estimated from the photographs.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical processing of the results was carried out using GraphPad Prism 10.3.1 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). To determine the statistical significance of the differences, a three-way ANOVA was used, a posteriori Fisher’s LSD test was used for comparison between groups, the results are presented as (mean ± SEM). The differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.S., S.N.I. and V.N.D.; methodology, D.A.R., O.B.B., A.V.S., D.N.V., A.A.V.; formal analysis, D.A.R., A.A.G., A.K.P., M.V.I.; investigation, D.A.R., O.B.B., A.V.S., D.N.V., A.A.G., A.K.P., I.A.P., V.S.L., M.V.O., D.A.M.; resources, S.N.I., V.N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.R., O.B.B., A.V.S., D.N.V., A.A.G., A.K.P., V.N.D.; writing—review and editing, D.A.R., O.B.B., A.V.S., A.K.P., V.S.L., M.V.O., D.A.M., A.A.V., S.N.I., V.N.D.; visualization, D.A.R., A.A.G., A.K.P.; supervision, O.O.B., A.V.S., A.A.V.; project administration, S.N.I., V.N.D.; funding acquisition, S.N.I., V.N.D.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Results of the assessment of the area of tissue stained for tyrosine hydroxylase in the substantia nigra. Left hemisphere - control; right hemisphere - damaged. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 1.

Results of the assessment of the area of tissue stained for tyrosine hydroxylase in the substantia nigra. Left hemisphere - control; right hemisphere - damaged. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 2.

Changes in the intensity of staining for tyrosine hydroxylase in the substantia nigra pars compacta.

Figure 2.

Changes in the intensity of staining for tyrosine hydroxylase in the substantia nigra pars compacta.

Figure 3.

The effect of LfU21 on microglial activation following separate administration of LAC or LPS, or a combination of both. IBA1 staining intensity is given as a percentage of the left black substance (contralateral to LAC or NaCl administration). Significant differences are indicated on the graphs. * - p<0.05 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 3.

The effect of LfU21 on microglial activation following separate administration of LAC or LPS, or a combination of both. IBA1 staining intensity is given as a percentage of the left black substance (contralateral to LAC or NaCl administration). Significant differences are indicated on the graphs. * - p<0.05 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 4.

A.drd2 mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. drd2 mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05, * - p<0.001 compared to Ctrl, # - p<0.05 compared to the group with the corresponding designation.

Figure 4.

A.drd2 mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. drd2 mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05, * - p<0.001 compared to Ctrl, # - p<0.05 compared to the group with the corresponding designation.

Figure 5.

A.ngf mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. ngf mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05.

Figure 5.

A.ngf mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. ngf mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05.

Figure 6.

A.bdnf mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. bdnf mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, * - p<0.05, ** - p<0.01, *** - p<0.001, # - p<0.0001 compared to Ctrl.

Figure 6.

A.bdnf mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. bdnf mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, * - p<0.05, ** - p<0.01, *** - p<0.001, # - p<0.0001 compared to Ctrl.

Figure 7.

A.trkB mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. trkB mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05.

Figure 7.

A.trkB mRNA level in the striatum in the left hemisphere. B. trkB mRNA level in the striatum in the right hemisphere. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Gene-specific signals were normalized on actb cDNA. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mRNA levels in the untreated group were taken as 1. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05.

Figure 8.

Immunofluorescence staining for total α-synuclein in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus following administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Scale: 100 μm.

Figure 8.

Immunofluorescence staining for total α-synuclein in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus following administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Scale: 100 μm.

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence staining (arrows) for phosphorylated α-synuclein in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus following administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Scale: 50 μm.

Figure 9.

Immunofluorescence staining (arrows) for phosphorylated α-synuclein in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus following administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Scale: 50 μm.

Figure 10.

Intensity of immunofluorescence staining for total α-synuclein (A) and phosphorylated α-synuclein (B) in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus after administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.001 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). The data is presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 10.

Intensity of immunofluorescence staining for total α-synuclein (A) and phosphorylated α-synuclein (B) in the ganglia of the myenteric plexus after administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.001 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). The data is presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 11.

Goblet cells in the epithelium of the small intestine after administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Stained with Alcian blue. Scale: 100 μm.

Figure 11.

Goblet cells in the epithelium of the small intestine after administration of LfU21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Stained with Alcian blue. Scale: 100 μm.

Figure 12.

Number of goblet cells per 100 μm of intestinal villus length after administration of strain U-21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.001 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). The data is presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 12.

Number of goblet cells per 100 μm of intestinal villus length after administration of strain U-21 to groups receiving LAC, LPS, and LAC+LPS. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.001 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). The data is presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 13.

A. Total superoxide dismutase activity in the liver of rats. B. Catalase activity in the liver of rats. C. The amount of GSH in the liver of rats. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05, asterisks, * - p<0.05, ** - p<0.01, *** - p<0.001, **** - p<0.0001 compared to Ctrl.

Figure 13.

A. Total superoxide dismutase activity in the liver of rats. B. Catalase activity in the liver of rats. C. The amount of GSH in the liver of rats. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05, asterisks, * - p<0.05, ** - p<0.01, *** - p<0.001, **** - p<0.0001 compared to Ctrl.

Figure 14.

A. IL6 content in the liver of rats. B. IL10 content in the liver of rats. C. TNF content in the liver of rats. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05. Comparison of group with # is with the corresponding group with the same designation, the number of # indicates the p-value, p<0.05 (#), p<0.01 (##) or p<0.001 (###).

Figure 14.

A. IL6 content in the liver of rats. B. IL10 content in the liver of rats. C. TNF content in the liver of rats. The data is presented as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, ns - p≥0.05. Comparison of group with # is with the corresponding group with the same designation, the number of # indicates the p-value, p<0.05 (#), p<0.01 (##) or p<0.001 (###).

Figure 15.

Effect of LfU21 on the quality of the front limb step in the “Rung ladder” test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Significant differences are indicated in the graphs. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 15.

Effect of LfU21 on the quality of the front limb step in the “Rung ladder” test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Significant differences are indicated in the graphs. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 16.

The effect of LfU21 on the quality of step performance with the left (A) and right (B) limbs in the “Rung ladder” test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Significant differences are indicated in the graphs. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 16.

The effect of LfU21 on the quality of step performance with the left (A) and right (B) limbs in the “Rung ladder” test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Significant differences are indicated in the graphs. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 17.

The effect of LfU21 on the neuroticism score (B) and total testing time (A) in the “Rung ladder” test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Significant differences are indicated in the graphs. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 17.

The effect of LfU21 on the neuroticism score (B) and total testing time (A) in the “Rung ladder” test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Significant differences are indicated in the graphs. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 18.

The effect of LfU21 on vertical motor activity in the Open Field test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.05 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 18.

The effect of LfU21 on vertical motor activity in the Open Field test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.05 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 19.

The effect of LfU21 on horizontal motor activity (A) and the number of grooming acts (B) in the Open Field test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.05 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 19.

The effect of LfU21 on horizontal motor activity (A) and the number of grooming acts (B) in the Open Field test against the background of both separate administration of LAC or LPS and their combination. Three-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. Significant differences are indicated on the graphs (* - p<0.05 compared to Ctrl, # - p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding groups without strain administration). Data are presented as mean + SEM.

Figure 20.

General diagram of measured biomarkers.

Figure 20.

General diagram of measured biomarkers.

Table 1.

Effect of exposure to two factors—LPS and lactacystin (LAC)—with clarification of the effect of each toxin separately on the studied biomarkers in rats. Arrows indicate a decrease/increase in indicators relative to the control group. r - right hemisphere, l - left hemisphere.

Table 1.

Effect of exposure to two factors—LPS and lactacystin (LAC)—with clarification of the effect of each toxin separately on the studied biomarkers in rats. Arrows indicate a decrease/increase in indicators relative to the control group. r - right hemisphere, l - left hemisphere.

| Experimental group |

Without L. fermentum U-21 |

L. fermentum U-21 |

Indicators normalized by L. fermentum U-21 |

| Ctrl |

|

bdnf(l)↑, bdnf(r)↓, total α-synuclein↓, GSH↑,

upward forepaw stepping↓ in the “Rung Ladder” test, quality of stepping with right limbs in the “Rung Ladder” test↓ |

|

| NaCl+LPS |

drd2(r)↑, bdnf(l)↓, bdnf(r)↓, total α-synuclein↑, phosphorylated α-synuclein↑, number of goblet cells↑,

SOD↑, CAT↑, GSH↓, IL6↑, IL10↑, TNF↑, quality of right limb stepping in the “Rung Ladder” test↓, level of neuroticism in the “Rung Ladder” test↑ |

bdnf(r)↓, total α-synuclein↑, phosphorylated α-synuclein↑, |

drd2(r), bdnf(l), number of goblet cells, SOD, CAT,

GSH, IL6, IL10, TNF |

| LAC+NaCl |

Tyrosine hydroxylase (r)↓, IBA1↑, bdnf(r)↓, total α-synuclein↑, phosphorylated α-synuclein↑, number of goblet cells↑, SOD↓,

testing time in the “Rung Ladder” test↑, neuroticism level in the “Rung Ladder” test↑,

vertical motor activity in the “Open Field” test↓, number of grooming acts in the “Open Field” test↓ |

Tyrosine hydroxylase (r)↓, IBA1↑, bdnf(r)↓, phosphorylated α-synuclein↑ |

total α-synuclein, SOD, vertical motor activity in the “Open Field” test |

| LAC+LPS |

Tyrosine hydroxylase (r)↓, IBA1↑, bdnf(r)↓, total α-synuclein↑, phosphorylated α-synuclein↑, number of goblet cells↑, SOD↑, CAT↑, GSH↓,

upward forepaw stepping↓ in the “Rung Ladder” test, testing time in the “Rung Ladder” test↑, neuroticism level in the “Rung ladder” test↑, number of grooming acts in the “Open field” test↓ |

Tyrosine hydroxylase (r)↓, IBA1↑, bdnf(r)↓, phosphorylated α-synuclein↑, SOD↓

|

total α-synuclein, GSH, upward forepaw stepping in the “Rung Ladder” test |