Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Predictive processing abnormalities offer a unifying account of perceptual and expressive disturbances in psychosis, yet classical predictive coding frameworks remain difficult to translate due to limited neurophysiological grounding. Emerging evidence positions beta-band oscillations and their transient burst dynamics as a biologically plausible mechanism for implementing top-down predictions that stabilize internal models. Study Design: This narrative review synthesizes evidence from electrophysiology, laminar physiology, computational modelling, language research, and clinical neuroimaging to evaluate beta oscillations as a mechanistic target for predictive processing deficits in psychosis. We integrate data from modified predictive routing frameworks and dendritic computation models to clarify how beta rhythms prepare cortical pathways for predicted inputs. Study Results: Across sensory, motor, cognitive, and language domains, schizophrenia features impaired generation, timing, and contextual deployment of beta activity. These include attenuated post-movement beta rebound, reduced or mistimed beta bursts during working memory and inhibition, abnormal beta-gamma interactions during perception, and weakened beta-mediated contextual guidance during language comprehension. Laminar and computational findings indicate that beta bursts arise from the integration of apical (contextual) and basal (sensory) dendritic inputs in layer 5 pyramidal neurons, providing a mechanistic substrate for top-down predictions. Beta disruptions, therefore, offer a parsimonious account of disorganization, psychomotor slowing, and failures of contextual maintenance. Early neuromodulation, pharmacologic, and neurofeedback studies suggest that beta dynamics are modifiable. Conclusions: Beta oscillations provide a tractable and mechanistically grounded target for predictive processing deficits in psychosis. Standardizing burst metrics and developing individualized, closed-loop approaches will be critical for advancing beta-based interventions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Implementation of Predictive Coding

- (1)

- The predictive coding framework usually assumes that precision (or reliability) weighted cortical feedback cancels expected input by subtracting it via inhibition, discarding the already predicted inputs, and transmitting only those activity ‘spikes’ that are not predicted. However, electrophysiological and laminar recordings show that feedback and feedforward activity often overlap in time, and feedback is often excitatory; not purely inhibitory or subtractive [10,11,12].

- (2)

- Predictive coding assumes prediction errors first originate in lower-level cortical areas and propagate upwards. However, empirical evidence does not consistently support this temporal order. Studies using laminar recordings and oscillatory markers infer prediction errors from superficial gamma-band activity and feedforward pathways, but these signals often appear simultaneously across levels or even earlier in higher-order cortices [10,13,14]. Moreover, the timescales required for multiple cycles of iterative feed-forward optimisation to converge are incompatible with most sensory processing timelines [15].

- (3)

- (4)

- Predictive coding framework mandates specialized ‘error units’ that handle the net difference between input and top-down predictions across the entire hierarchy of message passing (two types of these units described more recently by Nour Eddine et al. [18], with self-connections influencing precision computation [19]. Nonetheless, cellular data has not yet found evidence in support of such an architecture to hold residual information [11,20].

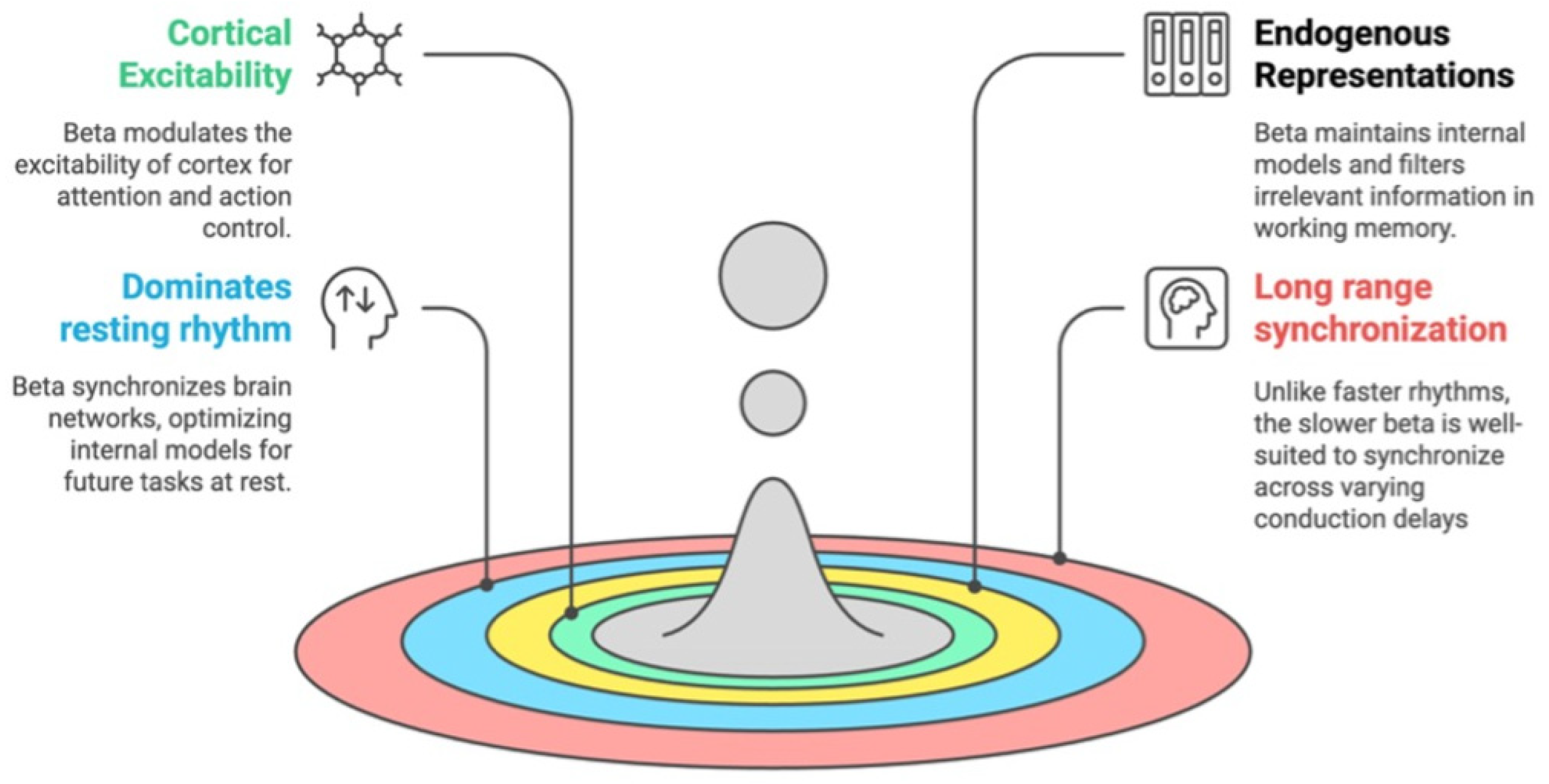

3. Oscillatory Rhythms and Predictive Routing

4. Why is Beta Central to Predictions?

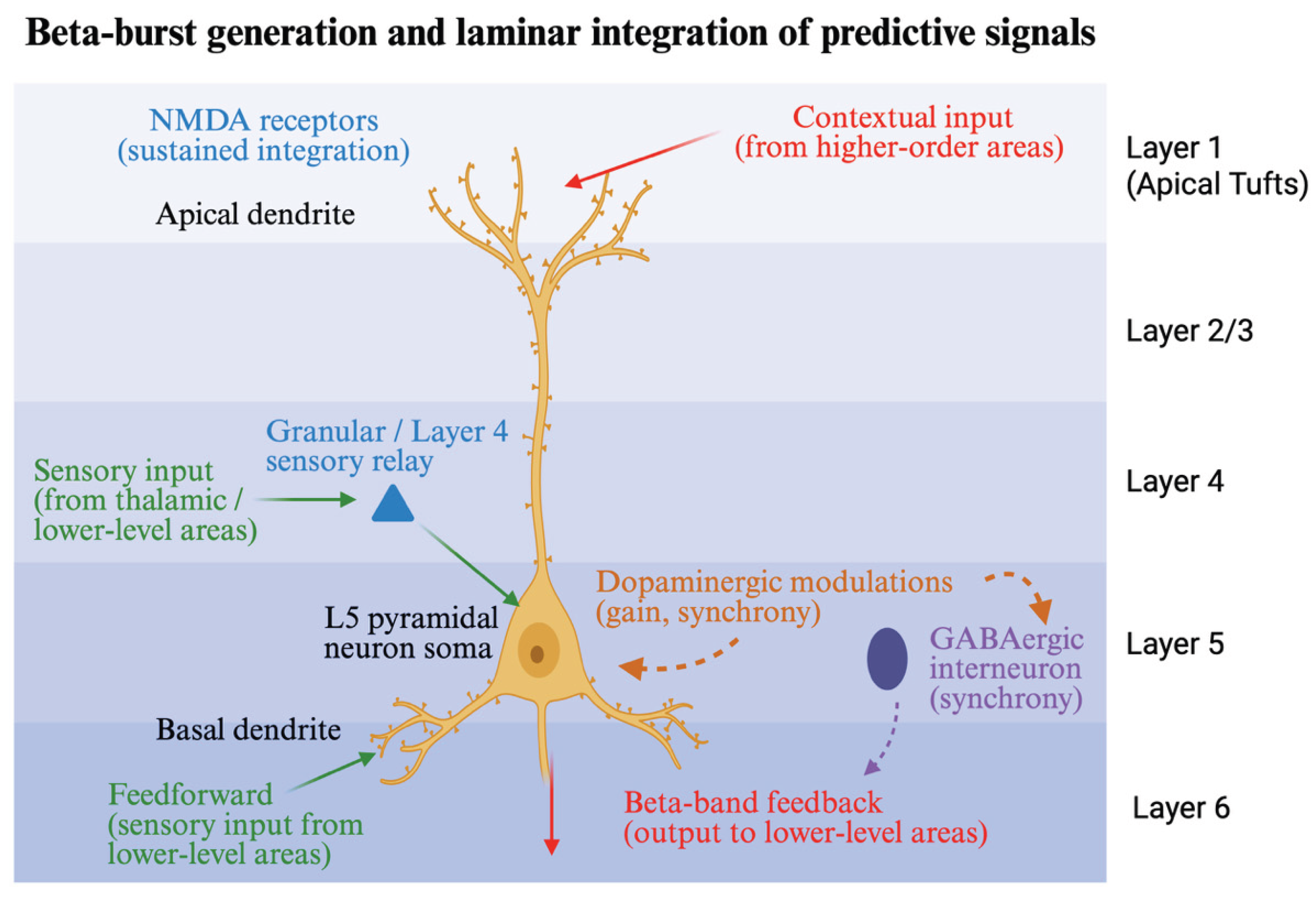

5. Generation of Beta Bursts

6. Beta, Language and Higher-Level Meaning

7. Clinical Implications of Beta Oscillations

8. Therapeutic Opportunities Targeting Beta

9. Limitations and Future Directions

10. Supplementary

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friston, K. Computational psychiatry: from synapses to sentience. Mol Psychiatry. 2023, 28, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams RA, Stephan KE, Brown HR, Frith CD, Friston KJ. The computational anatomy of psychosis. Front Psychiatry. 2013, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzer P, Adams RA, Fletcher P, et al. The Predictive Coding Account of Psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2018, 84, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav Brain Sci. 2013, 36, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao RP, Ballard DH. Predictive coding in the visual cortex: a functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nat Neurosci. 1999, 2, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo G, Parr T, Cisek P, Clark A, Friston K. Generating meaning: active inference and the scope and limits of passive AI. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2024, 28, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown M, Kuperberg GR. A Hierarchical Generative Framework of Language Processing: Linking Language Perception, Interpretation, and Production Abnormalities in Schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci 2015;9. [CrossRef]

- Liddle PF, Liddle EB. Imprecise Predictive Coding Is at the Core of Classical Schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci 2022;16. [CrossRef]

- Palaniyappan L, Venkatasubramanian G. The Bayesian brain and cooperative communication in schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2022, 47, E48–E54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos AM, Usrey WM, Adams RA, Mangun GR, Fries P, Friston KJ. Canonical Microcircuits for Predictive Coding. Neuron. 2012, 76, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulasch FA, Rudelt L, Wibral M, Priesemann V. Where is the error? Hierarchical predictive coding through dendritic error computation. Trends in Neurosciences. 2023, 46, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratling, M. A review of predictive coding algorithms. Brain and Cognition 2016;112. [CrossRef]

- Felleman DJ, Van Essen DC. Distributed Hierarchical Processing in the Primate Cerebral Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1991, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerberg JA, Xiong YS, Nejat H, et al. Adaptation, not prediction, drives neuronal spiking responses in mammalian sensory cortex. bioRxiv Published online January 9, 2025:2024.10.02.616378, January. [CrossRef]

- Millidge B, Tang M, Osanlouy M, Harper NS, Bogacz R. Predictive coding networks for temporal prediction. PLOS Computational Biology. 2024, 20, e1011183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos AM, Lundqvist M, Waite AS, Kopell N, Miller EK. Layer and rhythm specificity for predictive routing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020, 117, 31459–31469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabhart KM, Xiong YS, Bastos AM. Predictive coding: a more cognitive process than we thought? Trends Cogn Sci. 2025, 29, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour Eddine S, Brothers T, Wang L, Spratling M, Kuperberg GR. A predictive coding model of the N400. Cognition. 2024, 246, 105755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, KJ. Waves of prediction. PLOS Biology. 2019, 17, e3000426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratling, MW. Fitting predictive coding to the neurophysiological data. Brain Res. 2019, 1720, 146313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’dri AW, Barbier T, Teulière C, Triesch J. Predictive Coding Light. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 8880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviers G, Tang M, Bogacz R. Bidirectional predictive coding. arXiv Preprint posted online May 29, 29 May 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tscshantz A, Millidge B, Seth AK, Buckley CL. Hybrid predictive coding: Inferring, fast and slow. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023, 19, e1011280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerberg JA, Roelfsema PR. Hierarchical interactions between sensory cortices defy predictive coding. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20 October 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mansell W, Gulrez T, Landman M. The prediction illusion: perceptual control mechanisms that fool the observer. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2025, 62, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding JN, Wolpe N, Brugger SP, Navarro V, Teufel C, Fletcher PC. A new predictive coding model for a more comprehensive account of delusions. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2024, 11, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufel C, Fletcher PC. Forms of prediction in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020, 21, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinck M, Uran C, Dowdall JR, Rummell B, Canales-Johnson A. Large-scale interactions in predictive processing: oscillatory versus transient dynamics. Trends Cogn Sci. 2025, 29, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fişek M, Herrmann D, Egea-Weiss A, et al. Cortico-cortical feedback engages active dendrites in visual cortex. Nature. 2023, 617, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islah N, Etter G, Tugsbayar M, Gurbuz T, Richards B, Muller E. Learning to combine top-down context and feed-forward representations under ambiguity with apical and basal dendrites. arXiv, 26 October 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gabhart KM, Xiong Y (Sophy), Bastos AM. Predictive coding: a more cognitive process than we thought? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2025, 29, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos AM, Vezoli J, Bosman CA, et al. Visual areas exert feedforward and feedback influences through distinct frequency channels. Neuron. 2015, 85, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao ZC, Takaura K, Wang L, Fujii N, Dehaene S. Large-Scale Cortical Networks for Hierarchical Prediction and Prediction Error in the Primate Brain. Neuron. 2018, 100, 1252–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao ZC, Huang YT, Wu CT. A quantitative model reveals a frequency ordering of prediction and prediction-error signals in the human brain. Commun Biol. 2022, 5, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro D, van Kempen J, Boyd M, Panzeri S, Thiele A. Directed information exchange between cortical layers in macaque V1 and V4 and its modulation by selective attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021, 118, e2022097118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman CA, Schoffelen JM, Brunet N, et al. Attentional Stimulus Selection through Selective Synchronization between Monkey Visual Areas. Neuron. 2012, 75, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffalo EA, Fries P, Landman R, Buschman TJ, Desimone R. Laminar differences in gamma and alpha coherence in the ventral stream. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108, 11262–11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist M, Miller EK, Nordmark J, Liljefors J, Herman P. Beta: bursts of cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2024, 28, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Halliday D, Major AJ, Lee N, et al. A ubiquitous spectrolaminar motif of local field potential power across the primate cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2024, 27, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Pelt S, Heil L, Kwisthout J, Ondobaka S, van Rooij I, Bekkering H. Beta- and gamma-band activity reflect predictive coding in the processing of causal events. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016, 11, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinck M, Bosman CA. More Gamma More Predictions: Gamma-Synchronization as a Key Mechanism for Efficient Integration of Classical Receptive Field Inputs with Surround Predictions. Front Syst Neurosci 2016;10. [CrossRef]

- Betti V, Della Penna S, de Pasquale F, Corbetta M. Spontaneous Beta Band Rhythms in the Predictive Coding of Natural Stimuli. Neuroscientist. 2021, 27, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter CG, Coppola R, Bressler SL. Top-down beta oscillatory signaling conveys behavioral context in early visual cortex. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist M, Herman P, Miller EK. Working Memory: Delay Activity, Yes! Persistent Activity? Maybe Not. J Neurosci. 2018, 38, 7013–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan KK, D’Esposito M. The what, where and how of delay activity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019, 20, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold J, Gibson DJ, DePasquale B, Graybiel AM. Bursts of beta oscillation differentiate postperformance activity in the striatum and motor cortex of monkeys performing movement tasks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015, 112, 13687–13692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little S, Bonaiuto J, Barnes G, Bestmann S. Human motor cortical beta bursts relate to movement planning and response errors. PLOS Biology. 2019, 17, e3000479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman MA, Lee S, Law R, et al. Neural mechanisms of transient neocortical beta rhythms: Converging evidence from humans, computational modeling, monkeys, and mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016, 113, E4885–E4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ede F, Quinn AJ, Woolrich MW, Nobre AC. Neural Oscillations: Sustained Rhythms or Transient Burst-Events? Trends Neurosci. 2018, 41, 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010, 11, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigh ZJ, Tran H, Berger T, et al. Modulation of motor excitability reflects traveling waves of neural oscillations. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veniero D, Gross J, Morand S, Duecker F, Sack AT, Thut G. Top-down control of visual cortex by the frontal eye fields through oscillatory realignment. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt R, Ruiz MH, Kilavik BE, Lundqvist M, Starr PA, Aron AR. Beta Oscillations in Working Memory, Executive Control of Movement and Thought, and Sensorimotor Function. J Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8231–8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey A, Markowitz DA, Pesaran B. Top-down control of exogenous attentional selection is mediated by beta coherence in prefrontal cortex. bioRxiv Published online January 13, 2023:2023.01.11.523664, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xiao J, Adkinson JA, Myers J, et al. Beta activity in human anterior cingulate cortex mediates reward biases. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller G, Lopes da Silva FH. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: basic principles. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilavik BE, Zaepffel M, Brovelli A, MacKay WA, Riehle A. The ups and downs of beta oscillations in sensorimotor cortex. Exp Neurol 2012;245(Complete):15-26. [CrossRef]

- Tan H, Wade C, Brown P. Post-Movement Beta Activity in Sensorimotor Cortex Indexes Confidence in the Estimations from Internal Models. J Neurosci. 2016, 36, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel AK, Fries P. Beta-band oscillations--signalling the status quo? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin H, Law R, Tsutsui S, Moore CI, Jones SR. The rate of transient beta frequency events predicts behavior across tasks and species. Kajikawa Y, ed. eLife. 2017, 6, e29086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer B, Haegens S. Beyond the Status Quo: A Role for Beta Oscillations in Endogenous Content (Re)Activation. eNeuro 2017;4(4). [CrossRef]

- Langford ZD, Wilson CRE. Simulations reveal that beta burst detection may inappropriately characterize the beta band. Journal of Neurophysiology, 25 June 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arnal, LH. Predicting “When” Using the Motor System’s Beta-Band Oscillations. Front Hum Neurosci 2012;6. [CrossRef]

- Biau E, Kotz SA. Lower Beta: A Central Coordinator of Temporal Prediction in Multimodal Speech. Front Hum Neurosci 2018;12. [CrossRef]

- Morillon B, Baillet S. Motor origin of temporal predictions in auditory attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017, 114, E8913–E8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikermane M, Weerdmeester L, Rajamani N, et al. Cortical beta oscillations map to shared brain networks modulated by dopamine. eLife 2024;13. [CrossRef]

- de Pasquale F, Corbetta M, Betti V, Della Penna S. Cortical cores in network dynamics. NeuroImage. 2018, 180, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antzoulatos EG, Miller EK. Synchronous beta rhythms of frontoparietal networks support only behaviorally relevant representations. Pasternak T, ed. eLife. 2016, 5, e17822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogala J, Kublik E, Krauz R, Wróbel A. Resting-state EEG activity predicts frontoparietal network reconfiguration and improved attentional performance. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki R, Kojima S, Otsuru N, et al. Beta resting-state functional connectivity predicts tactile spatial acuity. Cereb Cortex. 2023, 33, 9514–9523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopell N, Ermentrout GB, Whittington MA, Traub RD. Gamma rhythms and beta rhythms have different synchronization properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97, 1867–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzulo G, Zorzi M, Corbetta M. The secret life of predictive brains: what’s spontaneous activity for? Trends Cogn Sci. 2021, 25, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto JJ, Little S, Neymotin SA, Jones SR, Barnes GR, Bestmann S. Laminar dynamics of high amplitude beta bursts in human motor cortex. NeuroImage. 2021, 242, 118479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grützner C, Wibral M, Sun L, et al. Deficits in high- (>60 Hz) gamma-band oscillations during visual processing in schizophrenia. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennesh E, Westerberg JA, Spencer-Smith J, Bastos A. Ubiquitous predictive processing in the spectral domain of sensory cortex. bioRxiv Preprint posted online August 1, 2025:2025.07.31.667946. [CrossRef]

- Marvan T, Phillips WA. Cellular mechanisms of cooperative context-sensitive predictive inference. Curr Res Neurobiol. 2024, 6, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips WA, Clark A, Silverstein SM. On the functions, mechanisms, and malfunctions of intracortical contextual modulation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham BP, Kay JW, Phillips WA. Context-Sensitive Processing in a Model Neocortical Pyramidal Cell With Two Sites of Input Integration. Neural Comput. 2025, 37, 588–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William P, Silverstein S. Convergence of biological and psychological perspectives on cognitive coordination in schizophrenia. The Behavioral and brain sciences. 2003, 26, 65–82; discussion 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neymotin SA, Daniels DS, Caldwell B, et al. Human Neocortical Neurosolver (HNN), a new software tool for interpreting the cellular and network origin of human MEG/EEG data. Ivry RB, Stolk A, Stolk A, Dalal SS, eds. eLife. 2020, 9, e51214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah R, Muralidharan V, Sundby KK, Aron AR. Temporally-precise disruption of prefrontal cortex informed by the timing of beta bursts impairs human action-stopping. Neuroimage. 2020, 222, 117222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana S, Hannah R, Muralidharan V, Aron AR. Temporal cascade of frontal, motor and muscle processes underlying human action-stopping. van den Wildenberg W, Ivry RB, van den Wildenberg W, Huster R, Bissett PG, eds. eLife. 2020, 9, e50371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporn S, Hein T, Herrojo Ruiz M. Alterations in the amplitude and burst rate of beta oscillations impair reward-dependent motor learning in anxiety. Swann NC, Colgin LL, Khanna P, Swann NC, eds. eLife. 2020, 9, e50654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, JR. β-Bursts Reveal the Trial-to-Trial Dynamics of Movement Initiation and Cancellation. J Neurosci. 2020, 40, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen M, Hagoort P. Frequency-based Segregation of Syntactic and Semantic Unification during Online Sentence Level Language Comprehension. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015, 27, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caucheteux C, Gramfort A, King JR. Evidence of a predictive coding hierarchy in the human brain listening to speech. Nat Hum Behav. 2023, 7, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperberg GR, Jaeger TF. What do we mean by prediction in language comprehension? Lang Cogn Neurosci. 2016, 31, 32–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskin R, Nieuwland MS. Prediction during language comprehension: what is next? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2023, 27, 1032–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Schoot L, Brothers T, et al. Predictive coding across the left fronto-temporal hierarchy during language comprehension. Cereb Cortex. 2023, 33, 4478–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovsepyan S, Olasagasti I, Giraud AL. Rhythmic modulation of prediction errors: A top-down gating role for the beta-range in speech processing. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023, 19, e1011595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis AG, Schoffelen JM, Schriefers H, Bastiaansen M. A Predictive Coding Perspective on Beta Oscillations during Sentence-Level Language Comprehension. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam NHL, Schoffelen JM, Udden J, Hulten A, Hagoort P. Neural activity during sentence processing as reflected in theta, alpha, beta, and gamma oscillations. Neuroimage. 2016, 142, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai G, Minett JW, Wang WSY. Delta, theta, beta, and gamma brain oscillations index levels of auditory sentence processing. Neuroimage. 2016, 133, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Hagoort P, Jensen O. Gamma Oscillatory Activity Related to Language Prediction. J Cogn Neurosci. 2018, 30, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford TJ, Spencer KM, Godwin M, et al. Gamma and Theta/Alpha-Band Oscillations in the Electroencephalogram Distinguish the Content of Inner Speech. eNeuro 2025;12(2). [CrossRef]

- Fontolan L, Morillon B, Liegeois-Chauvel C, Giraud AL. The contribution of frequency-specific activity to hierarchical information processing in the human auditory cortex. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaansen M, Magyari L, Hagoort P. Syntactic unification operations are reflected in oscillatory dynamics during on-line sentence comprehension. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010, 22, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss S, Mueller HM, Schack B, King JW, Kutas M, Rappelsberger P. Increased neuronal communication accompanying sentence comprehension. Int J Psychophysiol. 2005, 57, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Jensen O, van den Brink D, et al. Beta oscillations relate to the N400m during language comprehension. Hum Brain Mapp, 5 April 2012. [CrossRef]

- Bornkessel-Schlesewsky I, Schlesewsky M. Toward a Neurobiologically Plausible Model of Language-Related, Negative Event-Related Potentials. Front Psychol. 2019, 10, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederici AD, Steinhauer K, Frisch S. Lexical integration: Sequential effects of syntactic and semantic information. Memory & Cognition. 1999, 27, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis AG, Lemhӧfer K, Schoffelen JM, Schriefers H. Gender agreement violations modulate beta oscillatory dynamics during sentence comprehension: A comparison of second language learners and native speakers. Neuropsychologia. 2016, 89, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer L, Sun Y, Martin AE. “Entraining” to speech, generating language? Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. 2020, 35, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zioga I, Weissbart H, Lewis AG, Haegens S, Martin AE. Naturalistic Spoken Language Comprehension Is Supported by Alpha and Beta Oscillations. J Neurosci. 2023, 43, 3718–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang W, Zhao X, Wang L, Zhou X. Causal role of frontocentral beta oscillation in comprehending linguistic communicative functions. NeuroImage. 2024, 300, 120853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolen T, Mihai Dumitrescu A, Wens V, et al. Spectrotemporal cortical dynamics and semantic control during sentence completion. Clin Neurophysiol. 2024, 163, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradkin I, Nour MM, Dolan RJ. Theory-Driven Analysis of Natural Language Processing Measures of Thought Disorder Using Generative Language Modeling. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2023, 8, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe V, Mackinley M, Nour Eddine S, Wang L, Palaniyappan L, Kuperberg GR. Selective Insensitivity to Global Versus Local Linguistic Context in Speech Produced by Patients With Untreated Psychosis and Positive Thought Disorder. Biol Psychiatry, S: online , 2025, 10 June 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wang YL, Sharpe V, Mackinley M, et al. Glutamate, Contextual Insensitivity, and Disorganized Speech in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A 7T Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2025, 5, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoyne LE, Brookes MJ, Rathnaiah M, et al. Motor-related oscillatory activity in schizophrenia according to phase of illness and clinical symptom severity. Neuroimage Clin. 2020, 29, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt BAE, Liddle EB, Gascoyne LE, et al. Attenuated Post-Movement Beta Rebound Associated With Schizotypal Features in Healthy People. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2019, 45, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson SE, Brookes MJ, Hall EL, et al. Abnormal visuomotor processing in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 2015, 12, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briley PM, Liddle EB, Simmonite M, et al. Regional Brain Correlates of Beta Bursts in Health and Psychosis: A Concurrent Electroencephalography and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021, 6, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnaiah M, Liddle EB, Gascoyne L, et al. Quantifying the Core Deficit in Classical Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull Open. 2020, 1, sgaa031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Hua L, Xia Y, et al. Neural correlates of behavioral control and impulsivity in first-episode schizophrenia: A MEG-Based beta oscillation analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2025, 189, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig S, Spitzer B, Jacobs AM, Sekutowicz M, Sterzer P, Blankenburg F. Spectral EEG abnormalities during vibrotactile encoding and quantitative working memory processing in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 2016, 11, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson MA, Albrecht MA, Robinson B, Luck SJ, Gold JM. Impaired suppression of delay-period alpha and beta is associated with impaired working memory in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2017, 2, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang SS, MacDonald AW, Chafee MV, et al. Abnormal cortical neural synchrony during working memory in schizophrenia. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2018, 129, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein DY, Eisenberg DP, Carver FW, et al. Spatiotemporal Alterations in Working Memory-Related Beta Band Neuromagnetic Activity of Patients With Schizophrenia On and Off Antipsychotic Medication: Investigation With MEG. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2023, 49, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniyappan, L. Dissecting the neurobiology of linguistic disorganisation and impoverishment in schizophrenia. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022, 129, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Linden DEJ, Singer W, et al. Dysfunctional long-range coordination of neural activity during Gestalt perception in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2006, 26, 8168–8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Singer W. High-frequency oscillations and the neurobiology of schizophrenia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2013, 15, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Phillips WA, Silverstein SM. The course and clinical correlates of dysfunctions in visual perceptual organization in schizophrenia during the remission of psychotic symptoms. Schizophr Res 2005;75(2-3):183-192. [CrossRef]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Phillips WA, Mitchell G, Silverstein SM. Perceptual grouping in disorganized schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2006;145(2-3):105-117. [CrossRef]

- Sauer A, Grent-’t-Jong T, Wibral M, Grube M, Singer W, Uhlhaas PJ. A MEG Study of Visual Repetition Priming in Schizophrenia: Evidence for Impaired High-Frequency Oscillations and Event-Related Fields in Thalamo-Occipital Cortices. Front Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 561973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balz J, Roa Romero Y, Keil J, et al. Beta/Gamma Oscillations and Event-Related Potentials Indicate Aberrant Multisensory Processing in Schizophrenia. Front Psychol. 2016, 7, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson KR, Pokorny VJ, Rawls E, Olman CA, Sponheim SR. Seeing things in psychosis: Reduced theta power in early neural responses to ambiguous visual stimuli predicts perceptual distortions. Clin Neurophysiol. 2025, 176, 2110782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun L, Castellanos N, Grützner C, et al. Evidence for dysregulated high-frequency oscillations during sensory processing in medication-naïve, first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2013;150(2-3):519-525. [CrossRef]

- Garakh Z, Zaytseva Y, Kapranova A, et al. EEG correlates of a mental arithmetic task in patients with first episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 2090–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjini K, Bowyer SM, Wang F, Boutros NN. Deficit Versus Nondeficit Schizophrenia: An MEG-EEG Investigation of Resting State and Source Coherence—Preliminary Data. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2020, 51, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignapiano A, Koenig T, Mucci A, et al. Disorganization and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: New insights from electrophysiological findings. Int J Psychophysiol. 2019, 145, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati FL, Mayeli A, Nascimento Couto BA, et al. Prefrontal Oscillatory Slowing in Early-Course Schizophrenia Is Associated With Worse Cognitive Performance and Negative Symptoms: A Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation-Electroencephalography Study. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2025, 10, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeev-Wolf M, Levy J, Jahshan C, et al. MEG resting-state oscillations and their relationship to clinical symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 2018, 20, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo MCG, Kleinlogel H, Koukkou M. Differences in the EEG profiles of early and late responders to antipsychotic treatment in first-episode, drug-naive psychotic patients. Schizophrenia Research. 1998, 30, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett PR, Mohanty A, MacDonald AW. What we think about when we think about predictive processing. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020, 129, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe V, Mackinley M, Eddine SN, Wang L, Palaniyappan L, Kuperberg GR. GPT-3 reveals selective insensitivity to global vs. local linguistic context in speech produced by treatment-naïve patients with positive thought disorder. bioRxiv, 6: online , 2024, 8 July 2024.

- Ma L, Skoblenick K, Johnston K, Everling S. Ketamine Alters Lateral Prefrontal Oscillations in a Rule-Based Working Memory Task. J Neurosci. 2018, 38, 2482–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaraswamy SD, Shaw AD, Jackson LE, Hall J, Moran R, Saxena N. Evidence that Subanesthetic Doses of Ketamine Cause Sustained Disruptions of NMDA and AMPA-Mediated Frontoparietal Connectivity in Humans. J Neurosci. 2015, 35, 11694–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plataki ME, Diskos K, Sougklakos C, et al. Effect of Neonatal Treatment With the NMDA Receptor Antagonist, MK-801, During Different Temporal Windows of Postnatal Period in Adult Prefrontal Cortical and Hippocampal Function. Front Behav Neurosci 2021;15. [CrossRef]

- Rivolta D, Heidegger T, Scheller B, et al. Ketamine Dysregulates the Amplitude and Connectivity of High-Frequency Oscillations in Cortical–Subcortical Networks in Humans: Evidence From Resting-State Magnetoencephalography-Recordings. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2015, 41, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlén M, Meletis K, Siegle JH, et al. A critical role for NMDA receptors in parvalbumin interneurons for gamma rhythm induction and behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2012, 17, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio S, Aljohani YM, Olson TT, Forcelli PA, Dezfuli G, Kellar KJ. Restoration of norepinephrine release, cognitive performance, and dendritic spines by amphetamine in aged rat brain. Aging Cell. 2024, 23, e14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupre KB, Cruz AV, McCoy AJ, et al. Effects of L-dopa priming on cortical high beta and high gamma oscillatory activity in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2016, 86, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray NJ, Jenkinson N, Wang S, et al. Local field potential beta activity in the subthalamic nucleus of patients with Parkinson’s disease is associated with improvements in bradykinesia after dopamine and deep brain stimulation. Experimental Neurology. 2008, 213, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinkhauser G, Pogosyan A, Tan H, Herz DM, Kühn AA, Brown P. Beta burst dynamics in Parkinson’s disease OFF and ON dopaminergic medication. Brain. 2017, 140, 2968–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian D, Li W, Xue J, et al. A striatal SOM-driven ChAT-iMSN loop generates beta oscillations and produces motor deficits. Cell Reports 2022;40(3). [CrossRef]

- Bauer M, Kluge C, Bach D, et al. Cholinergic enhancement of visual attention and neural oscillations in the human brain. Curr Biol. 2012, 22, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondabolu K, Roberts EA, Bucklin M, McCarthy MM, Kopell N, Han X. Striatal cholinergic interneurons generate beta and gamma oscillations in the corticostriatal circuit and produce motor deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016, 113, E3159–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung LS, Gill RS, Shen B, Chu L. Cholinergic and behavior-dependent beta and gamma waves are coupled between olfactory bulb and hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2024, 34, 464–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi R, Novella JL, Laurent-Badr S, et al. Cholinergic Antagonists and Behavioral Disturbances in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy MM, Moore-Kochlacs C, Gu X, Boyden ES, Han X, Kopell N. Striatal origin of the pathologic beta oscillations in Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108, 11620–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman-Polletta BR, Quach A, Mohammed AI, et al. Striatal cholinergic receptor activation causes a rapid, selective and state-dependent rise in cortico-striatal β activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2018, 48, 2857–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtle A, Mohrbutter C, Hils J, et al. Cholinergic modulation of motor sequence learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2024, 60, 3706–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang H, Yang X, Yan S, Sun Z. Effect of acetylcholine deficiency on neural oscillation in a brainstem-thalamus-cortex neurocomputational model related with Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 14961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi YB, Thomas ML, Braff DL, et al. Anticholinergic Medication Burden-Associated Cognitive Impairment in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2021, 178, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leicht G, Andreou C, Nafe T, et al. Alterations of oscillatory neuronal activity during reward processing in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020, 129, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg TE, Dodge M, Aloia M, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Effects of neuroleptic medications on speech disorganization in schizophrenia: biasing associative networks towards meaning. Psychol Med. 2000, 30, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman C, Richter U, Jones CR, Agerskov C, Herrik KF. Activity-State Dependent Reversal of Ketamine-Induced Resting State EEG Effects by Clozapine and Naltrexone in the Freely Moving Rat. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 737295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebollo B, Perez-Zabalza M, Ruiz-Mejias M, Perez-Mendez L, Sanchez-Vives MV. Beta and Gamma Oscillations in Prefrontal Cortex During NMDA Hypofunction: An In Vitro Model of Schizophrenia Features. Neuroscience. 2018, 383, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth SH, Cruz Bosch C, Raffoul JJ, et al. Safety of rTMS for Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2025, 51, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tervo AE, Nieminen JO, Lioumis P, et al. Closed-loop optimization of transcranial magnetic stimulation with electroencephalography feedback. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischnewski M, Haigh ZJ, Shirinpour S, Alekseichuk I, Opitz A. The phase of sensorimotor mu and beta oscillations has the opposite effect on corticospinal excitability. Brain Stimulation. 2022, 15, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrenner C, Desideri D, Belardinelli P, Ziemann U. Real-time EEG-defined excitability states determine efficacy of TMS-induced plasticity in human motor cortex. Brain Stimulation. 2018, 11, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang Z, Sack AT, Leunissen I. The phase of tACS-entrained pre-SMA beta oscillations modulates motor inhibition. Neuroimage. 2024, 290, 120572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittain JS, Probert-Smith P, Aziz TZ, Brown P. Tremor Suppression by Rhythmic Transcranial Current Stimulation. Current Biology. 2013, 23, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan R, Ye S, Zhong Y, Chen Q, Cai Y. Transcranial alternating current stimulation for the treatment of major depressive disorder: from basic mechanisms toward clinical applications. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1197393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt AB, Kormann E, Gulberti A, et al. Phase-Dependent Suppression of Beta Oscillations in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. J Neurosci. 2019, 39, 1119–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwippel T, Pupillo F, Feldman Z, et al. Closed-Loop Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder: An Open-Label Pilot Study. AJP. 2024, 181, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamali Nezhad F, Martin J, Tassone VK, et al. Transcranial alternating current stimulation for neuropsychiatric disorders: a systematic review of treatment parameters and outcomes. Front Psychiatry. 2024, 15, 1419243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak H, Sreeraj VS, Venkatasubramanian G. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) and Its Role in Schizophrenia: A Scoping Review. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2023, 21, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raco V, Bauer R, Tharsan S, Gharabaghi A. Combining TMS and tACS for Closed-Loop Phase-Dependent Modulation of Corticospinal Excitability: A Feasibility Study. Front Cell Neurosci 2016;10. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Xu Z, Fleming MK, et al. Closed-loop beta stimulation enhances beta activity and motor behaviour. bioRxiv Preprint posted online October 8, 2025:2025.10.07.680961. [CrossRef]

- Jurewicz K, Paluch K, Kublik E, Rogala J, Mikicin M, Wróbel A. EEG-neurofeedback training of beta band (12-22Hz) affects alpha and beta frequencies—A controlled study of a healthy population. Neuropsychologia. 2018, 108, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluschke A, Broschwitz F, Kohl S, Roessner V, Beste C. The neuronal mechanisms underlying improvement of impulsivity in ADHD by theta/beta neurofeedback. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 31178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang J, Lv S, Li Y, Hao P, Li X, Gao C. The effects of neurofeedback training on behavior and brain functional networks in children with autism spectrum disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2025, 481, 115425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhäußer AM, Bluschke A, Roessner V, Beste C. Distinct effects of different neurofeedback protocols on the neural mechanisms of response inhibition in ADHD. Clin Neurophysiol. 2023, 153, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Sokhadze EM, El-Baz AS, et al. Relative Power of Specific EEG Bands and Their Ratios during Neurofeedback Training in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi SM, Mirzaei A, Valizadeh A, Ebrahimpour R. Excitatory deep brain stimulation quenches beta oscillations arising in a computational model of the subthalamo-pallidal loop. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little S, Pogosyan A, Kuhn AA, Brown P. Beta band stability over time correlates with Parkinsonian rigidity and bradykinesia. Exp Neurol. 2012, 236, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang DD, Hemptinne C de, Miocinovic S, et al. Pallidal Deep-Brain Stimulation Disrupts Pallidal Beta Oscillations and Coherence with Primary Motor Cortex in Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2018, 38, 4556–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu Y, Escobar Sanabria D, Wang J, et al. Parkinsonism Alters Beta Burst Dynamics across the Basal Ganglia–Motor Cortical Network. J Neurosci. 2021, 41, 2274–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia Y, Hua L, Dai Z, et al. Attenuated post-movement beta rebound reflects psychomotor alterations in major depressive disorder during a simple visuomotor task: a MEG study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia Y, Sun H, Hua L, et al. Spontaneous beta power, motor-related beta power and cortical thickness in major depressive disorder with psychomotor disturbance. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 38, 103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun CF, Arnbjerg CJ, Kessing LV. Electroencephalographic Parameters Differentiating Melancholic Depression, Non-melancholic Depression, and Healthy Controls. A Systematic Review. Front Psychiatry 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh BC, Fukuda AM, Gemelli ZT, et al. Pre-treatment frontal beta events are associated with executive dysfunction improvement after repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 2023, 168, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle CE, Fonzo GA, Wu W, et al. Cortical Connectivity Moderators of Antidepressant vs Placebo Treatment Response in Major Depressive Disorder: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020, 77, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo SK, Hale TS, Macion J, et al. Cortical activity patterns in ADHD during arousal, activation and sustained attention. Neuropsychologia. 2009, 47, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh BC, Vigne MM, Gamble I, et al. Dysfunctional oscillatory bursting patterns underlie working memory deficits in adolescents with ADHD. bioRxiv Published online December 10, 2024:2024.12.09.627520. [CrossRef]

- Torrecillos F, Tinkhauser G, Fischer P, et al. Modulation of Beta Bursts in the Subthalamic Nucleus Predicts Motor Performance. J Neurosci. 2018, 38, 8905–8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solway A, Schneider I, Lei Y. The relationships between subclinical OCD symptoms, beta/gamma-band power, and the rate of evidence integration during perceptual decision making. Neuroimage Clin. 2022, 34, 102975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Predictive Coding | Modified Predictive Routing |

| Prediction Error (PE) Mechanism | Prediction error is generated by dedicated canonical circuitry. | Prediction error occurs when sensory inputs reach an unprepared (uninhibited) cortex. |

| Nature of Predictive Signal | Predictions (priors) are thought to be subtractive, generally suppressing overall neuronal activity. | Predictions are sparse, selective preparatory signals issued by higher-order cortex that influence the constraints carried by the lower-order cortex. |

| Scope of Predictions | Predictions are widespread and canonical across the entire cortex. | Predictions are mediated by beta rhythms as selective and sparse top-down signals. |

| Prediction Signal Carrier (Feedback) | Predictions feedback down the hierarchy via deep layers (L5/6). | Predictions feedback via deep layers utilizing alpha/beta rhythms. |

| Error Signal (Feedforward) | PE signals feed forward up the hierarchy via superficial layers (L2/3). | Enhanced processing at lower levels carried by gamma frequency (40–90 Hz) and associated spiking via superficial layers. |

| Primary Implementation Mechanism | Canonical microcircuit with dedicated error units; self-connections on error units modulating precision. | Spectrolaminar mechanisms that flexibly route information; no dedicated error units. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).