Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

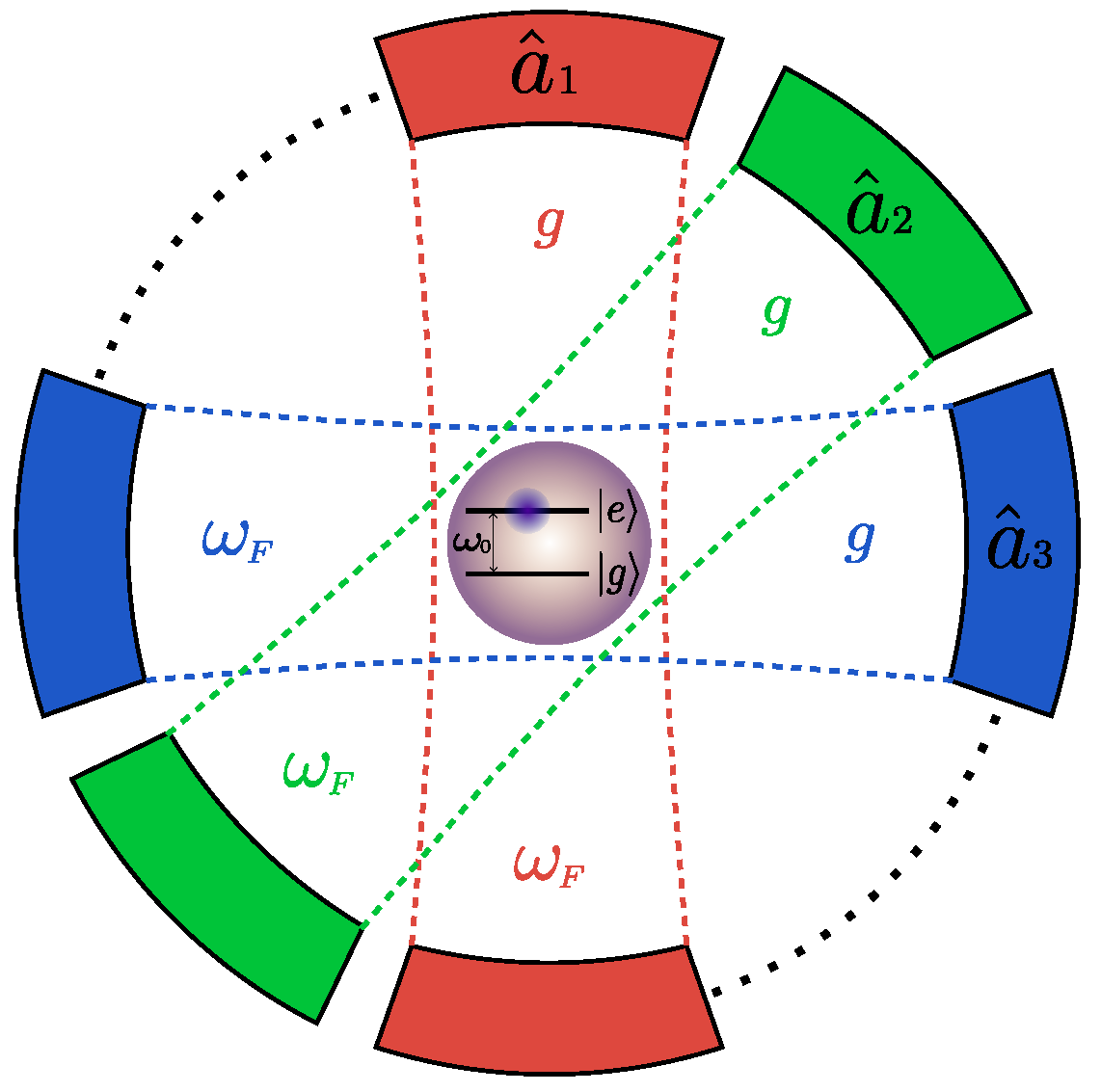

2. A Two–Level Atom Interacting with N Quantized Fields

2.1. Invariant approach

3. Two Quantized Fields Interacting with the Atom

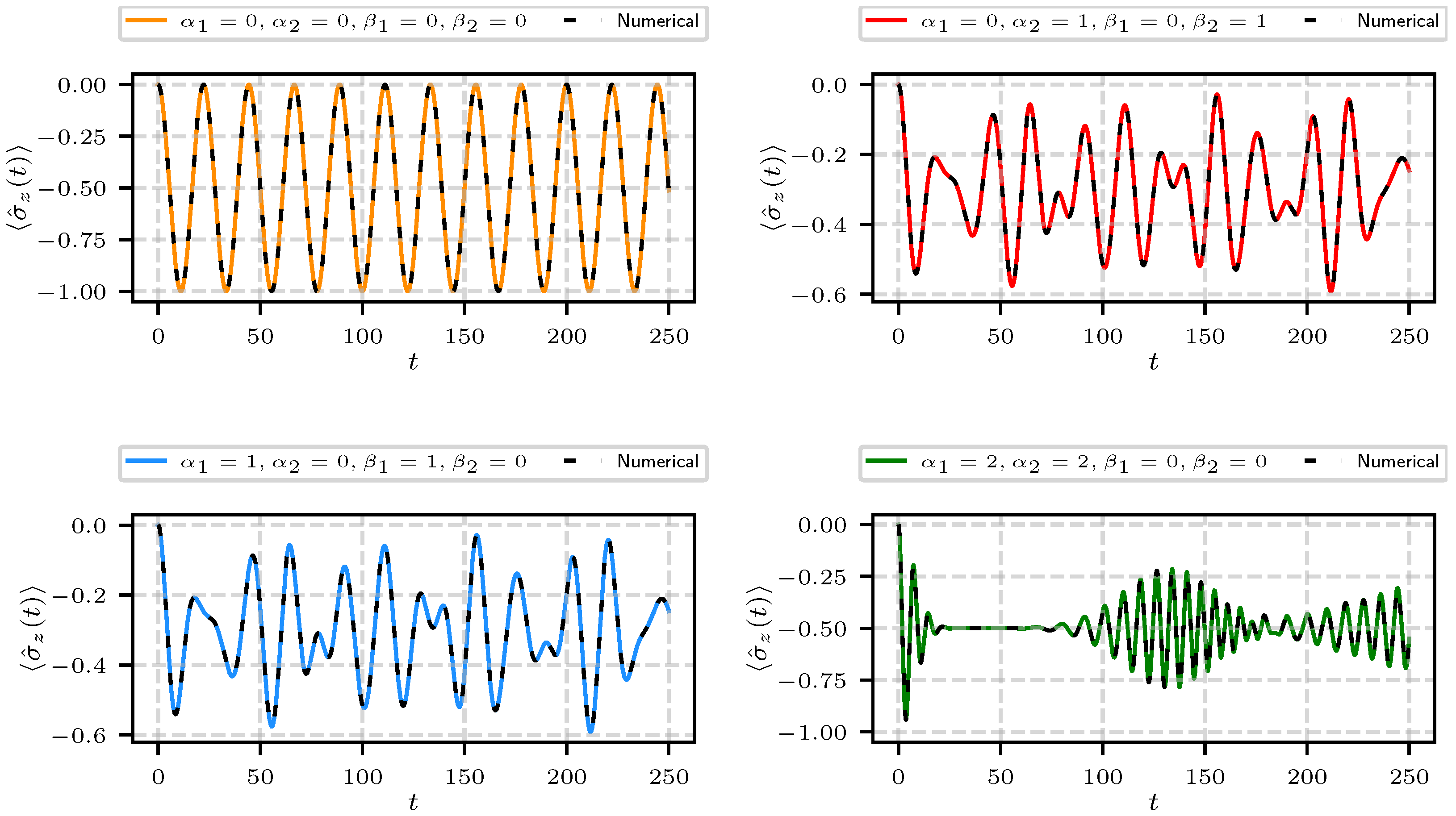

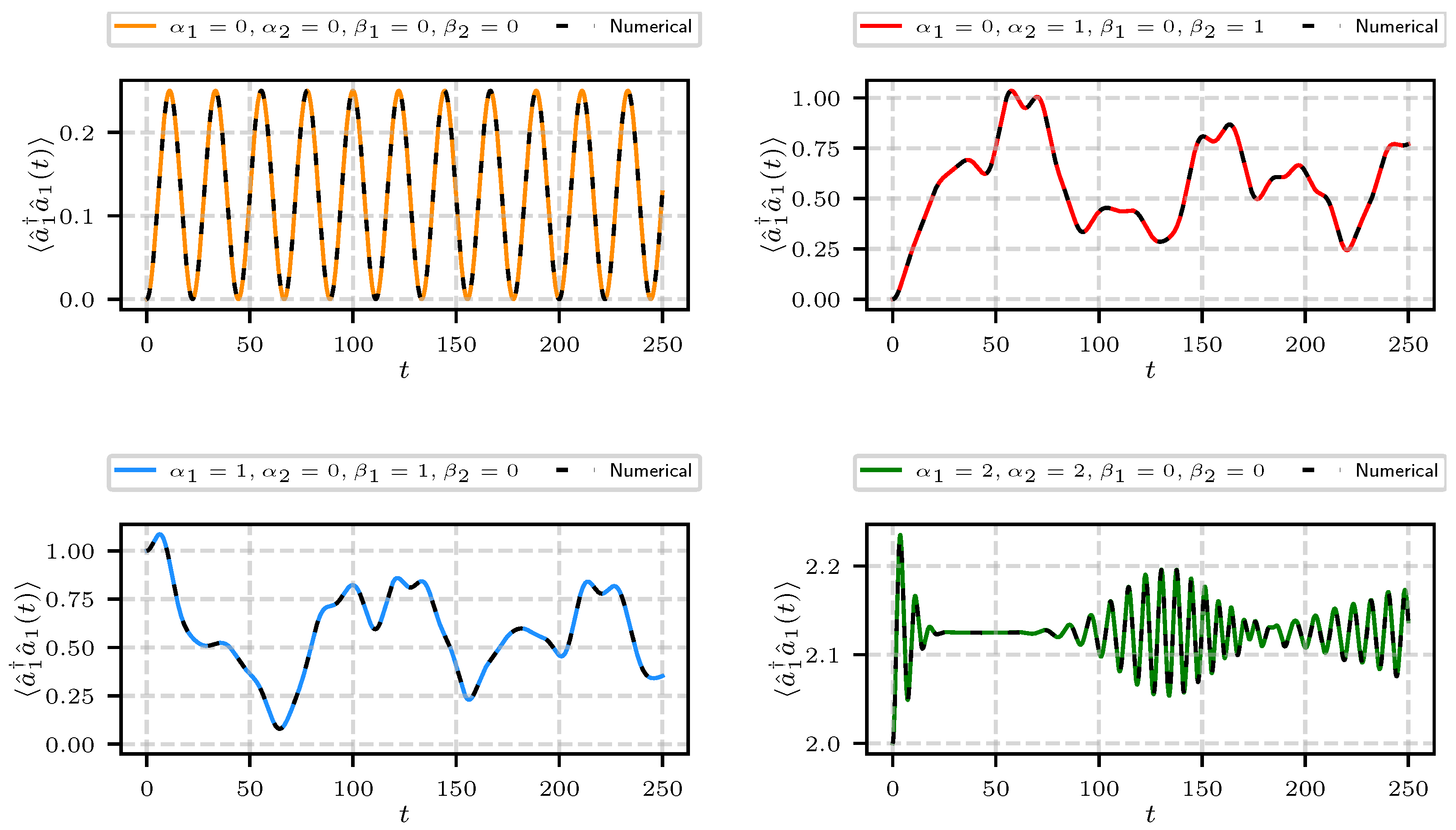

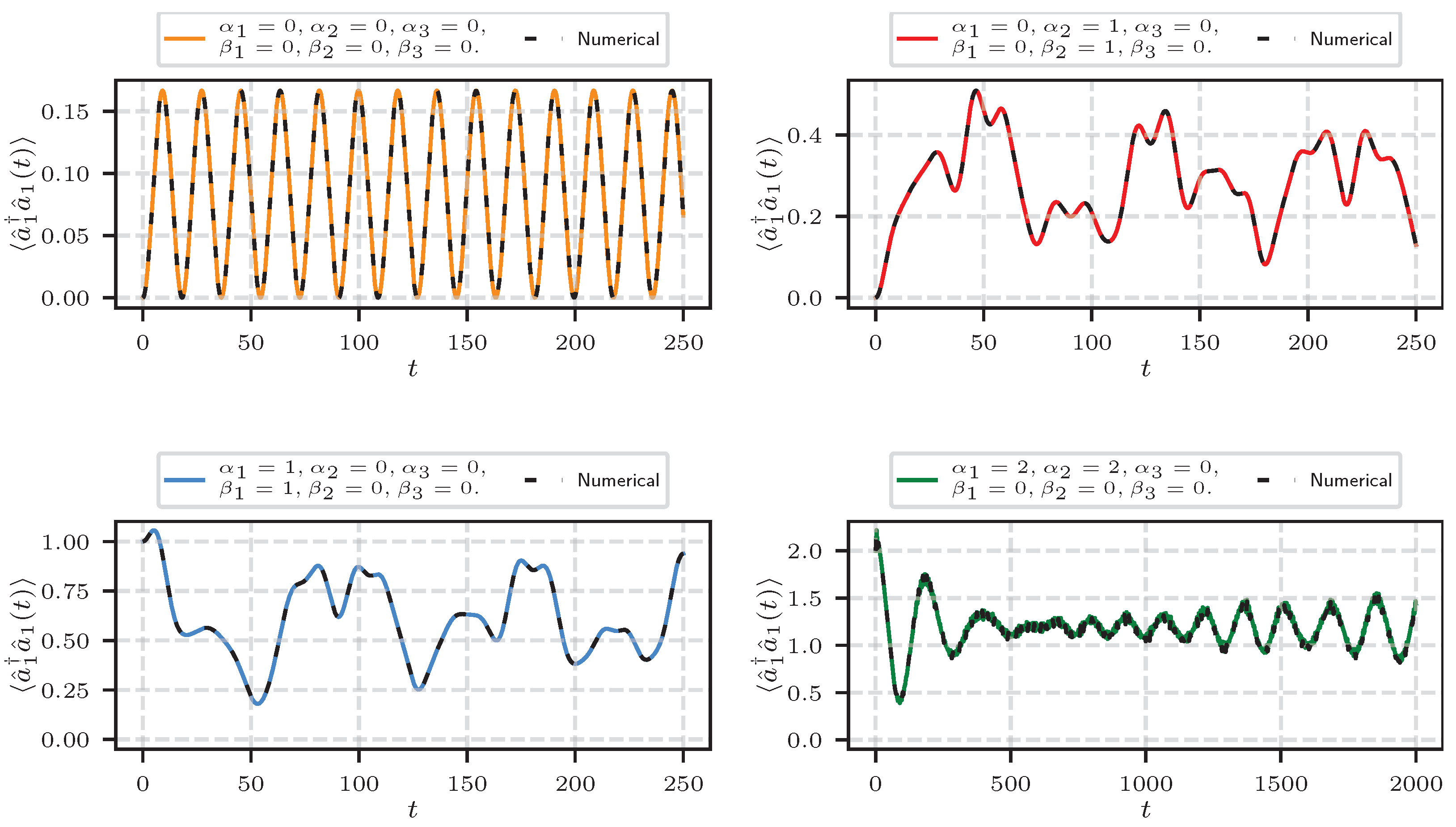

3.1. Atomic Inversion and Average Photon Number

4. Three Quantized Fields Interacting with the Atom

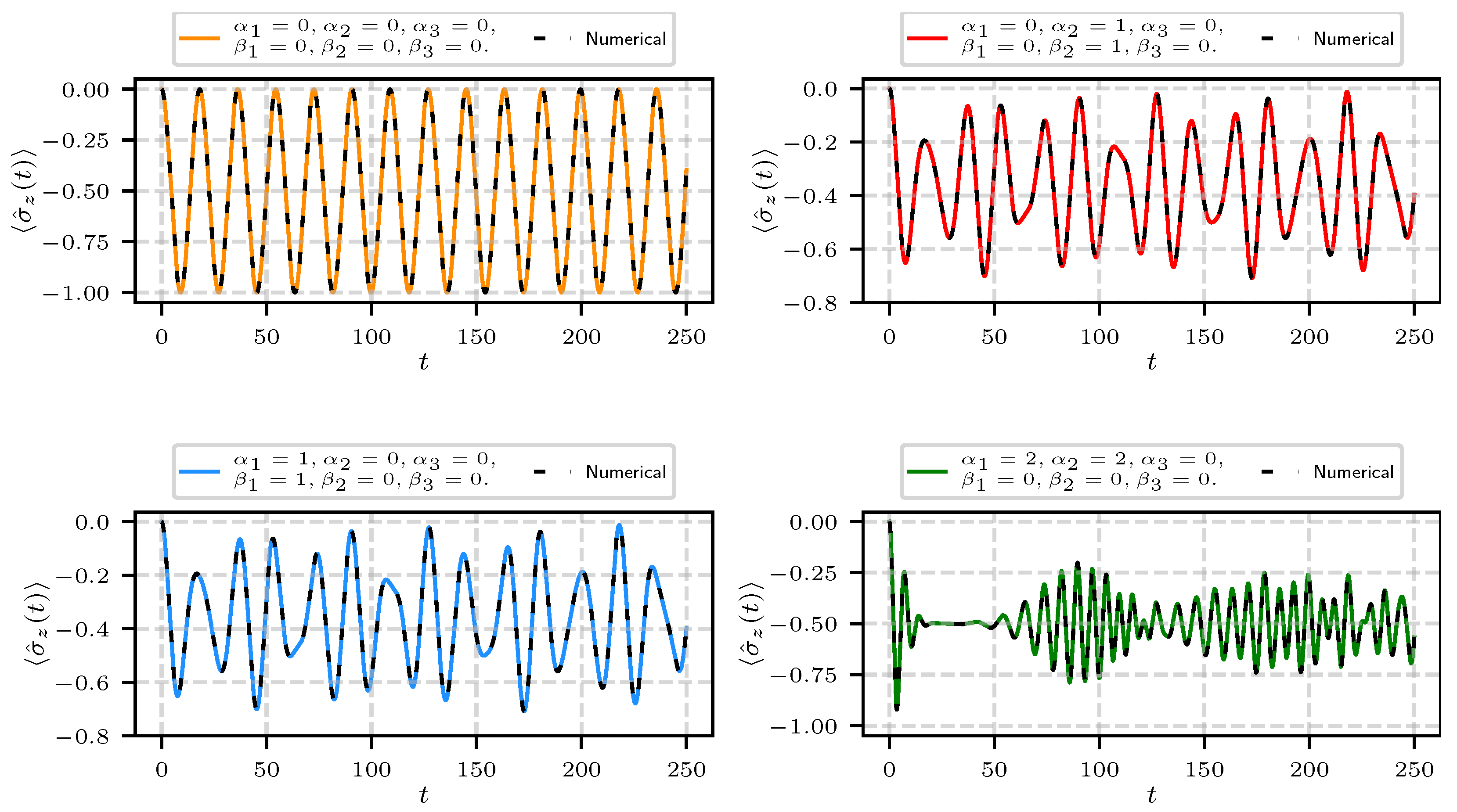

4.1. Atomic Inversion and Average Number of Photons

5. Generalization to N Fields

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rabi, I.I. Space Quantization in a Gyrating Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. 1937, 51, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, D. Integrability of the Rabi Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaynes, E.; Cummings, F. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proceedings of the IEEE 1963, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, B.W.; Knight, P.L. The jaynes-cummings model. Journal of Modern Optics 1993, 40, 1195–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J.; Mavrogordatos, T. The Jaynes–Cummings Model and Its Descendants; 2053-2563, IOP Publishing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Eberly, J.H.; Narozhny, N.B.; Sanchez-Mondragon, J.J. Periodic Spontaneous Collapse and Revival in a Simple Quantum Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 1323–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narozhny, N.B.; Sanchez-Mondragon, J.J.; Eberly, J.H. Coherence versus incoherence: Collapse and revival in a simple quantum model. Phys. Rev. A 1981, 23, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meystre, P.; Zubairy, M. Squeezed states in the Jaynes-Cummings model. Physics Letters A 1982, 89, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.C.; Zheng, S.B. Generation of Schrödinger cat states via the Jaynes-Cummings model with large detuning. Physics Letters A 1996, 223, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Contreras, J.A.; Ramos-Prieto, I.; Zúñiga-Segundo, A.; Moya-Cessa, H.M. The anisotropic quantum Rabi model with diamagnetic term. Frontiers in Physics 2025, Volume 13 - 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Uscanga, A.; Rodríguez, E.B.; Martínez, E.P.; Bastarrachea-Magnani, M.A. Magic States in the Asymmetric Quantum Rabi Model. arXiv, 2025; arXiv:quant-ph/2508.00765. [Google Scholar]

- Asbóth, J.K.; Domokos, P.; Ritsch, H. Correlated motion of two atoms trapped in a single-mode cavity field. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 013414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roversi, J.A.; Vidiella-Barranco, A.; Moya-Cessa, H. Dynamics of two atoms coupled to a cavity field. Modern Physics Letters B 2003, 17, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, R.H. Coherence in Spontaneous Radiation Processes. Phys. Rev. 1954, 93, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, D. Solution of the Dicke model for N = 3. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2013, 46, 224007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavis, M.; Cummings, F.W. Exact Solution for an N-Molecule—Radiation-Field Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. 1968, 170, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafez, A.M.; Obada, A.S.F.; Ahmad, M.M.A. N-level atom and (N-1) modes: an exactly solvable model with detuning and multiphotons. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 1987, 20, L359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochetov, E. A generalized N-level single-mode Jaynes-Cummings model. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1988, 150, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bužek, V. N-level Atom Interacting with Single-mode Radiation Field: An Exactly Solvable Model with Multiphoton Transitions and Intensity-dependent Coupling. Journal of Modern Optics 1990, 37, 1033–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Chatterjee, A. Nonclassicality in a dispersive atom–cavity field interaction in presence of an external driving field. International Journal of Modern Physics B 2024, 38, 2450415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidiella-Barranco, A.; Magalhães de Castro, A.S.; Sergi, A.; Roversi, J.A.; Messina, A.; Migliore, A. Analytical Solutions of the Driven Time-Dependent Jaynes–Cummings Model. Annalen der Physik 2025, 537, e00148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocanegra-Garay, I.A.; Hernández-Sánchez, L.; Ramos-Prieto, I.; Soto-Eguibar, F.; Moya-Cessa, H.M. Invariant approach to the driven Jaynes-Cummings model. SciPost Physics 2024, 16, 007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, B.; Sukumar, C. Exactly soluble model of atom-phonon coupling showing periodic decay and revival. Physics Letters A 1981, 81, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, C.; Buck, B. Multi-phonon generalisation of the Jaynes-Cummings model. Physics Letters A 1981, 83, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Field statistics in some generalized Jaynes-Cummings models. Phys. Rev. A 1982, 25, 3206–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, G.J. Energetics of radiation and a two-level atom in an ideal resonant cavity. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 37, 2482–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, M.; Ahmed, M.; Obada, A.S. Multimode and multiphoton processes in a non-linear Jaynes-Cummings model. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1991, 170, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildfeuer, C.; Schiller, D.H. Generation of entangled N-photon states in a two-mode Jaynes-Cummings model. Phys. Rev. A 2003, 67, 053801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.S.; Ahmed, M.M.A.; Obada, A.S.F. Some statistical properties of the interaction between a two-level atom and three field modes. Laser Physics 2015, 25, 065204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seke, J. Extended Jaynes–Cummings model. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1985, 2, 968–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, S.M.; Knight, P.L.; Moya-Cessa, H. Discriminating field mixtures from macroscopic superpositions. Phys. Rev. A 1993, 48, 3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benivegna, G. Quantum effects in the transient dynamics of a many mode Jaynes-Cummings model. Journal of Modern Optics 1996, 43, 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J. Scheme for generating entangled states of two field modes in a cavity. Journal of Modern Optics 2006, 53, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benivegna, G.; Messina, A. New Quantum Effects in the Dynamics of a Two-mode Field Coupled to a Two-level Atom. Journal of Modern Optics 1994, 41, 907–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J. Modern Quantum Mechanics, 3 ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Wei, J.; Norman, E. On global representations of the solutions of linear differential equations as a product of exponentials. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1964, 15, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerry, C.; Knight, P. Introductory Quantum Optics; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).