Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Case Report

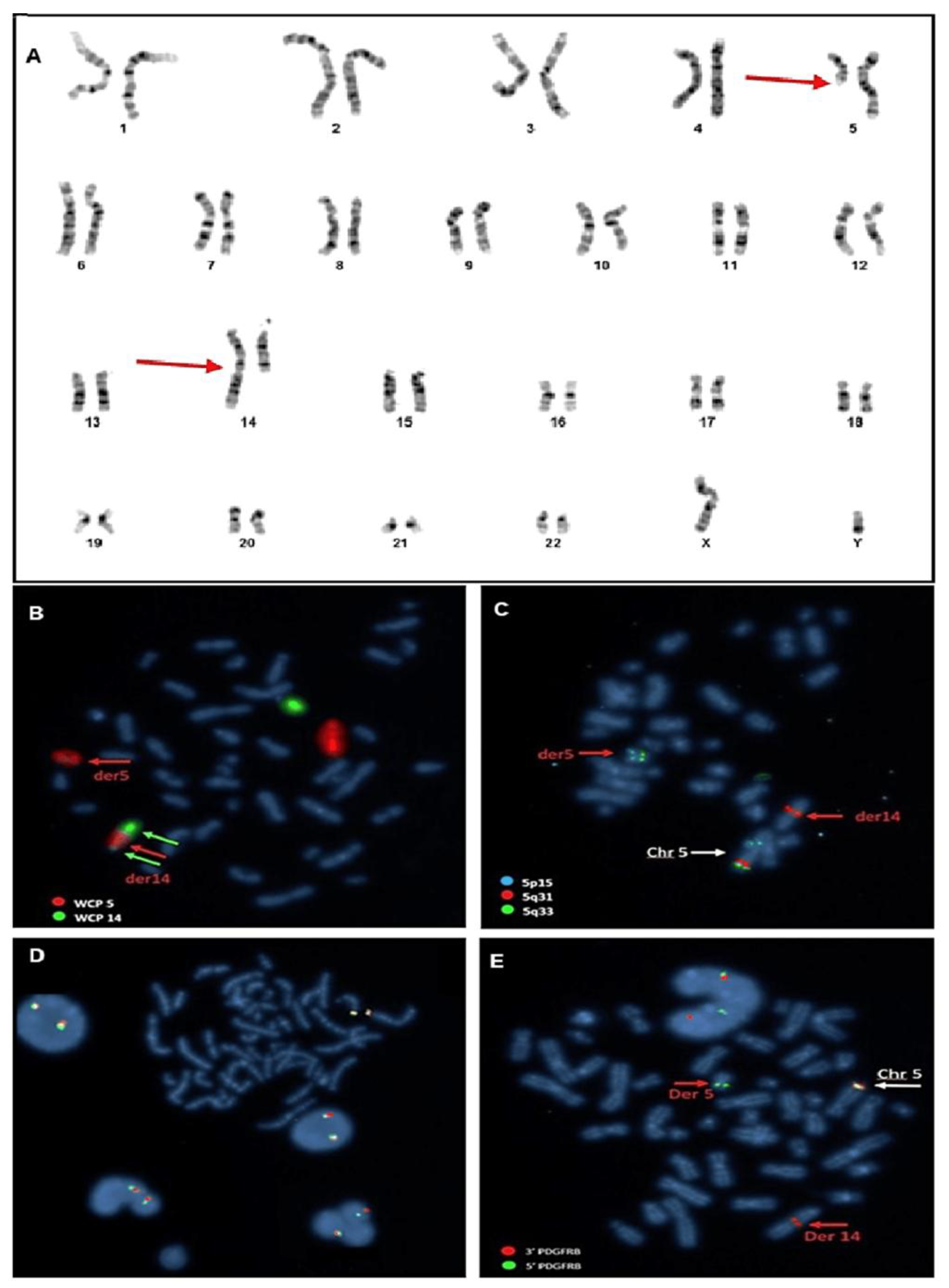

2.2. Cytogenetic Analysis

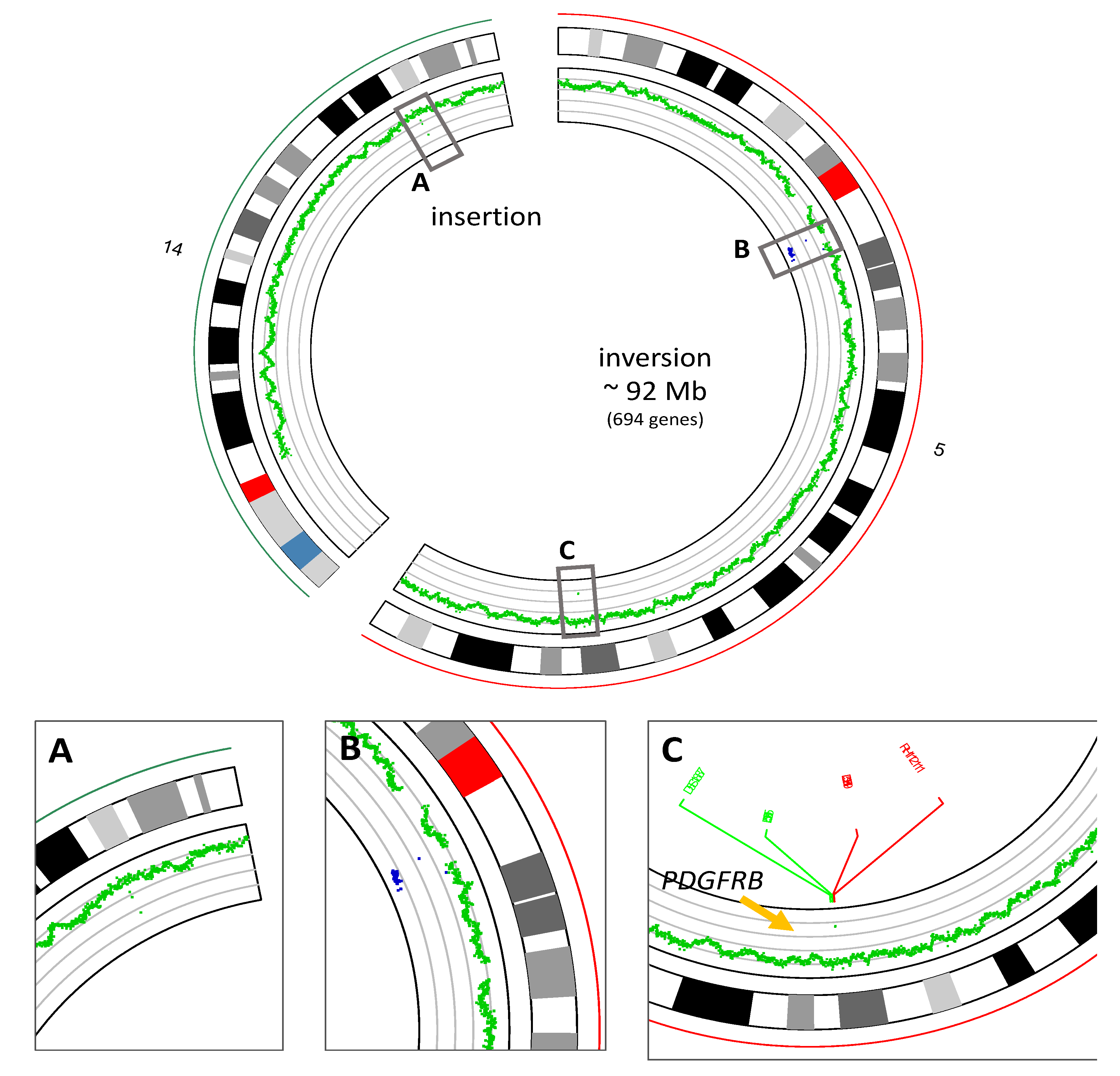

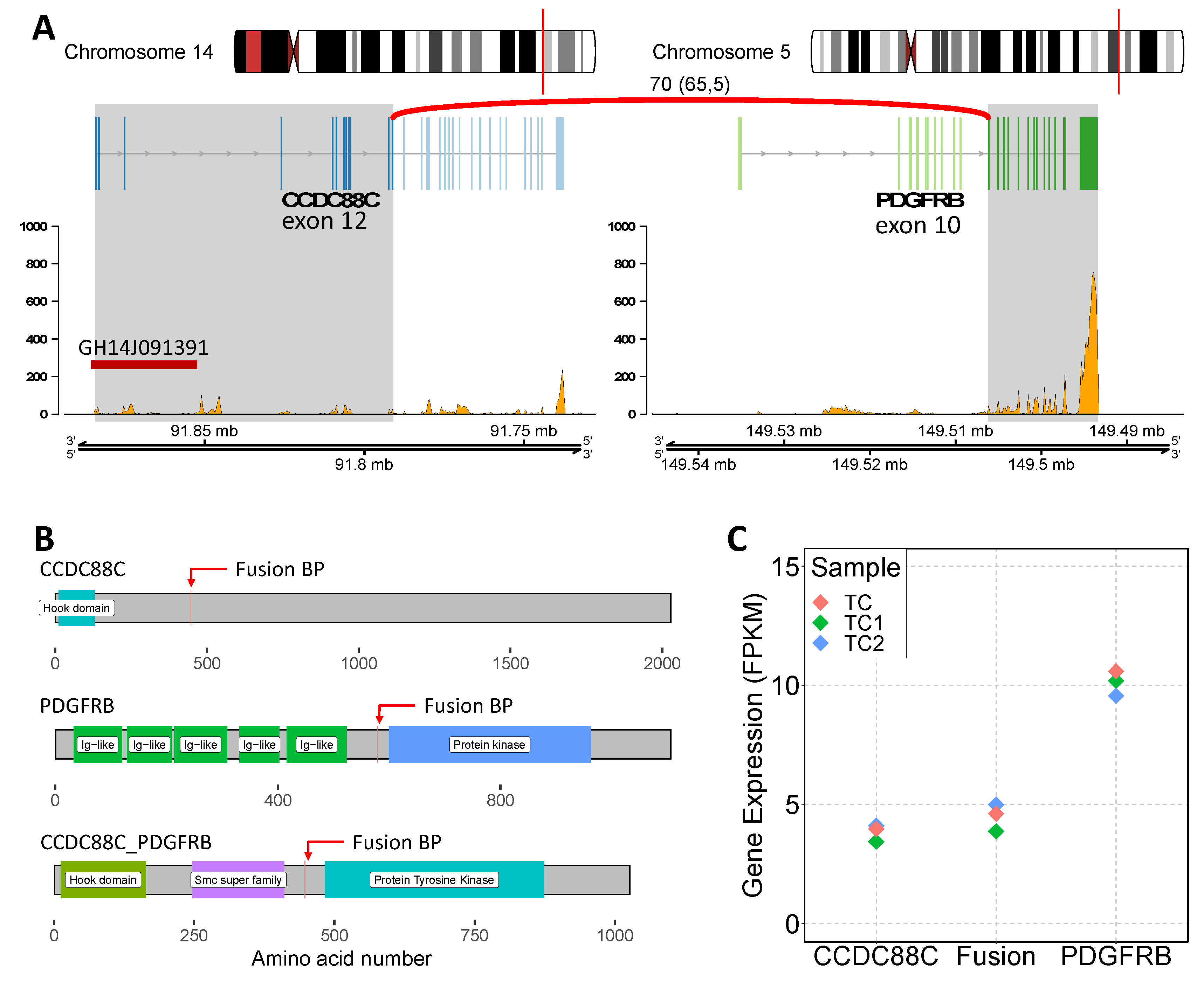

2.3. Whole Genome Sequencing and RNA Sequencing Analysis

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Etichs Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heldin CH, Lennartsson J. Structural and functional properties of platelet-derived growth factor and stem cell factor receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013 Aug 1;5(8):a009100. PMID: 23906712; PMCID: PMC3721287. [CrossRef]

- Florence A. Arts, Raf Sciot, Bénédicte Brichard, Marleen Renard, Audrey de Rocca Serra, Guillaume Dachy, Laura A. Noël, Amélie I. Velghe, Christine Galant, Maria Debiec-Rychter, An Van Damme, Miikka Vikkula, Raphaël Helaers, Nisha Limaye, Hélène A. Poirel, Jean-Baptiste Demoulin, PDGFRB gain-of-function mutations in sporadic infantile myofibromatosis, Human Molecular Genetics, Volume 26, Issue 10, 15 May 2017, Pages 1801–1810, . [CrossRef]

- Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022;36(7):1703–1719.

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022;140(11):1200–1228.

- Oya S, Morishige S, Ozawa H, et al. Beneficial tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in a patient with relapsed BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia with CCDC88C-PDGFRB fusion. Int J Hematol 2021;113(2):285–289.

- Coutré S, Gotlib J. Targeted treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes and chronic eosinophilic leukemias with imatinib mesylate. Semin Cancer Biol 2004;14(4):307–315.

- Di Giacomo D, Quintini M, Pierini V, et al. Genomic and clinical findings in myeloid neoplasms with PDGFRB rearrangement. Ann Hematol 2022;101(2):297–307.

- Gosenca D, Kellert B, Metzgeroth G, et al. Identification and functional characterization of imatinib-sensitive DTD1-PDGFRB and CCDC88C-PDGFRB fusion genes in eosinophilia-associated myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2014;53(5):411–421.

| Gene | Exons Tested | Gene | Exons Tested |

| WT1 | 6-10 | PTPN11 | 3,7-13 |

| SETBP1 | 4 | HRAS | 2,3 |

| FLT3 | 13-15,20 | CALR | 9 |

| CBL | 8,9 | IDH2 | 4 |

| CEBPA | All | KRAS | 2,3 |

| TP53 | 2-11 | NRAS | 2,3 |

| ETV6 | All | SRSF2 | 1 |

| MPL | 10 | SF3B1 | 10-16 |

| BRAF | 15 | CSF3R | All |

| IDH1 | 4 | EZH2 | All |

| ASXL1 | 9,11,12,14 | KIT | 2,8-11,13,17,18 |

| JAK2 | All | RUNX1 | All |

| TET2 | All | ABL1 | 4-9 |

| U2AF1 | 2,6 | NPM1 | 10,11 |

| ZRSR2 | All | DNMT3A | All |

| Gene | Type | Description | VAF (%) |

| ZRSR2 | Inframe insertion | c.1338_1343dup | 97.8 |

| SETBP1 | Missense mutation | c.691G>C | 49.2 |

| KIT | Missense mutation | c.1621A>C | 99.7 |

| Primer/Probe | Sequence | Tm (°C) |

| FW (Forward) | GAGATTGCACAGAAGCAGAG | 47.8 |

| RV (Reverse) | AGGATGATAAGGGAGATGATGG | 47.6 |

| Probe | FAM-5’ ACGCAGACTTGTCAGACGCCTTGCC 3’-TAMRA | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).