1. Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have emerged as promising molecular tools for enhancing plant immunity. The SNAKIN/GASA family represents a well-characterized group of cysteine-rich AMPs with multiple members and proven activity against bacterial and fungal pathogens in various plant species [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Some authors consider them to be the type of AMPs with the greatest effect against phytopathogens of fungal and bacterial origin [

13]. These peptides exhibit broad-spectrum activity against bacterial and fungal pathogens and are implicated in diverse physiological processes, including growth regulation and stress responses [

5,

7,

11]. Recent genomic surveys have revealed a large repertoire of GASA genes in citrus, with at least 18 annotated members and additional variants such as GASA9-like [

14]. There are examples showing that the introduction of coding genes for antimicrobial peptides into citrus is a suitable alternative for the control of microorganisms [

8,

15,

16]. Yet, functional characterization in citrus remains scarce, and the extent to which these genes contribute to broad-spectrum or specific immunity is unclear. Given the urgent need for durable resistance and the complexity of citrus breeding, identifying and validating endogenous GASA genes with antimicrobial activity could provide a strategic advantage for both conventional and biotechnological improvement.

The aim of this work is to identify and characterize new candidate endogenous genes by exploring the pan-genomic diversity of defense mechanisms among GASA genes present in

Citrus rootstock germplasm, like

P. trifoliata. This could help genetic breeding efforts by introgression or genomic edition of new resistance genes or alleles (yet to be discovered) present in germplasm accessions. In potato (

Solanum tuberosum), members such as Snakin-1 and Snakin-3 have demonstrated strong antimicrobial effects and have been successfully deployed in transgenic strategies to reduce disease symptoms [

1,

7,

11]. However, despite their potential, the mechanisms of action of GASA proteins remain poorly understood, partly due to pleiotropic effects that complicate functional studies.

Conventional breeding for disease resistance in citrus is notoriously difficult because of biological constraints, including long juvenile phases, apomixis, partial sterility, and frequent interspecific hybridization difficulty [

17,

18]. These limitations have shifted breeding efforts toward rootstock improvement, as tolerant rootstocks can confer resilience to the grafted scion [

17,

19,

20]. However, different citru

s accessions used as rootstocks were shown to confer very contrasting resistance or tolerance against bacterial diseases. Among these, trifoliate orange

(Poncirus trifoliata) stands out as a key genetic resource due to its sexual compatibility with

Citrus species and its documented tolerance to Huanglongbing (HLB) and other diseases [

19,

21].

Here, we adopt a pan-genomic approach to explore the diversity of GASA genes in citrus rootstock germplasm and to identify candidates with potential antimicrobial roles. We report the cloning and classification of 67 new GASA genomic variants across eight Citrus and related species, confirm their conservation within three major subfamilies, and analyze their expression patterns in tissues relevant to defense and development. To bridge genomic discovery with functional evidence, we selected three candidates—PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10—from Poncirus trifoliata, a rootstock known for its disease tolerance, and evaluated their activity in a model pathosystem using Nicotiana benthamiana challenged with Xanthomonas citri (incompatible interaction) and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci (compatible interaction). Our findings provide new insights into the structural and functional diversity of citrus GASA proteins and highlight promising genetic targets for breeding and genome editing strategies aimed at improving bacterial disease resistance.

3. Discussion

Bacterial diseases such as Huanglongbing (HLB) and citrus canker continue to threaten the sustainability of citrus production worldwide, challenging conventional breeding and demanding robust genetic targets for improved resistance for breeding [

16,

19,

30]. To that end, identification of key genetic targets conferring such tolerance requires the screening of the wide

Citrus pangenome diversity stored in germplasm banks. We recently generated a comprehensive co-expression network analysis using RNA-seq data from 17 public datasets offering a molecular framework for understanding HLB pathogenesis and host response. Among these key genetic targets, different antimicrobial peptides (AMP) families have been profiled during the recent years in order to explore new immune pathways for the control of destructive bacterial diseases like HLB (see Younas et al. [

35], for a very recent example) in order to identify and introgress their encoding gene variants from resistant genotypes into the cultivated susceptible varieties. The SNAKIN/GASA gene family encodes small AMPs with such potential, since several studies have demonstrated their antimicrobial role against pathogenic agents of various origins, including bacteria and fungi [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

49]. However, their antimicrobial mechanisms of action are not yet understood, in part due to their pleiotropic effects, which severely affect the architectural phenotype in mutant plants [

1,

11,

49,

50].

Q1: The first question to answer here is if, within the citrus GASA family, are there any resistance genes in the citrus germplasm that could be used for breeding purposes against bacterial diseases?

To begin with, by leveraging a pan-genomic framework, our study expands the catalog of citrus GASA genes with 67 new curated variants across rootstock-enriched germplasm. Furthermore, we provide functional evidence that two members from

Poncirus trifoliata,

PtGASA6 (subfamily I) and

PtGASA10 (subfamily III), modulate plant defense

in vivo through distinct outcomes: specifically,

PtGASA6 accelerated hypersensitive response (HR) whereas

PtGASA10 delayed disease progression. Together with expression profiling, promoter cis-element prediction and structural/topological inference, these results position citrus GASA genes as candidates for further studies for their use in resistance breeding and biotechnology [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

14,

16].

Q2: Are these genes induced or constitutively expressed?

Initially, previous studies by Wu et al. [

14] demonstrated that several GASA genes exhibit basal expression in different tissues of

C. clementina. In agreement with these findings, our results across rootstock accessions show that juvenile leaves and floral tissues display higher GASA expression than mature leaves (see

Figure 5), a pattern coherent with developmental roles and defense priming in actively growing tissues [

10,

14]. Wu et al. [

14] also investigated the comparative expression of GASA genes after infections with

X. citri in detached leaf explants of

C. clementina. From these experiments, the authors conclude that 6 genes, including GASA8, presented a significant increase in expression. The induction of these genes could indicate that, although they have a good basal expression in the tissues where the

X. citri infection is produced, their expression increases after infection, so these genes could be playing some role against it [

14] or be a collateral effect of the infection process. Moreover, meta-analysis of HLB-related RNA-seq datasets revealed upregulation of GASA10-13 in infected

C. sinensis over extended time courses, as well as early induction of GASA6 and GASA14 upon psyllid feeding that transmits CLas [

34,

36,

37]. Conversely, GASA8 exhibited contrasting behavior—repression in some uninfected conditions, but induction in

C. clementina explants challenged with

X. citri—highlighting context dependence across host–pathogen settings [

14,

34]. A final indication of specific gene induction by pathogens comes from

Solanum tuberosum, where

StSN3 (a potato ortholog of GASA10) is upregulated by

Pseudomonas syringae pv.

tabaci [

5,

11]

. P. syringae is the very same pathogen that was used here to challenge GASA10 overexpression in

N. benthamiana (see

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9).

Q3: What regulatory logic underlies these expression patterns?

In addition. promoter mining provided a mechanistic bridge to these patterns. Specifically, all three selected genes contain light-responsive elements (consistent with leaf/flower expression), ABA/MeJA motifs (abiotic stress and defense). Most importantly,

PtGASA10 exhibited a unique salicylic acid (SA)–responsive TCA element among the analyzed promoters [

56,

57]. Given SA’s central role in biotrophic pathogen defense and HR signaling, this cis-signature plausibly could underpin

PtGASA10’s potential behavior under HLB-related contexts and its effect on delaying symptom development [

16,

34,

35]. In contrast,

PtGASA6 lacked a predicted membrane anchor and SA motif, pointing toward a different contribution mechanism to HR priming and signaling [

5,

7,

11,

14]. The fact that some of the members are induced by infection while others do not, show that some members adjust to the standard basic definition of acquired passive resistance (they are “just there”, passively waiting to prevent infection without any changes), while others are actively induced by the infection process. All together, these results suggest that among the wide pan-genomic diversity of GASA genes, more than one single mechanism of resistance may coexist within this large gene family.

Q4: Can we prove that any of the new genes/alleles really confer resistance to bacterial diseases, i.e. is there a functional validation available in a tractable pathosystem?

To address this, we performed transient expression assays in

Nicotiana benthamiana. As a result,

PtGASA6 and

PtGASA10 enhanced defense responses through distinct mechanisms.

PtGASA6 accelerated hypersensitive response (HR), while

PtGASA10 delayed necrosis caused by

Pseudomonas syringae pv

. tabaci. These complementary effects suggest subfamily-specific roles in pathogen resistance [33,35;

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12]. By contrast,

PtGASA8—despite expression evidence in tolerant rootstocks—did not yield consistent phenotypic benefits under our specific conditions, underscoring the gene and context- specificity of AMP-mediated defense [

11,

14,

34]. Therefore, these findings confirm that at least two GASA genes confer measurable resistance traits

in vivo. Together, these results echo and extend past findings in potato: some members of the snakin family are inducible by pathogens and can curtail disease spread, but their net outcome depends on subfamily identity, expression level, and subcellular localization [

1,

5,

7,

11]. SNAKIN/GASA genes enhance defense against pathogens by a variety of mechanisms. Enhancement of hypersensitive response and necrosis reduction are just two of them, and maybe, GASA8 has others. Importantly, in our hands

PtGASA10 delayed necrosis more robustly than

PtGASA6 despite lower expression, suggesting higher functional efficiency, distinct kinetics, or greater protein stability in the infection milieu.

Q5: Is the resistance mechanism expression-dependent i.e. is the observed upregulation of GASA genes necessary for a more effective resistance?

Furthermore, our agroinfiltration assays demonstrate that overexpression of PtGASA6 or PtGASA10 effectively triggered HR after X. citri infection and significantly reduced symptoms caused by P. syringae pv. tabaci. In contrast, these effects were absent at basal expression levels in the negative control. Consequently, the mechanism appears to be expression-dependent for these two genes.

Q6: Does the observed diversity reflect coevolution or neutral drift i.e. does this wide pan-genomic diversity responds, at least partially, to a coevolution process with specific pathogen species or strains (like in the gene-for-gene interaction) or if it is just due to neutral selection and redundancy?

Most of the evidence collected so far in the literature and in this paper suggests that both could be true.

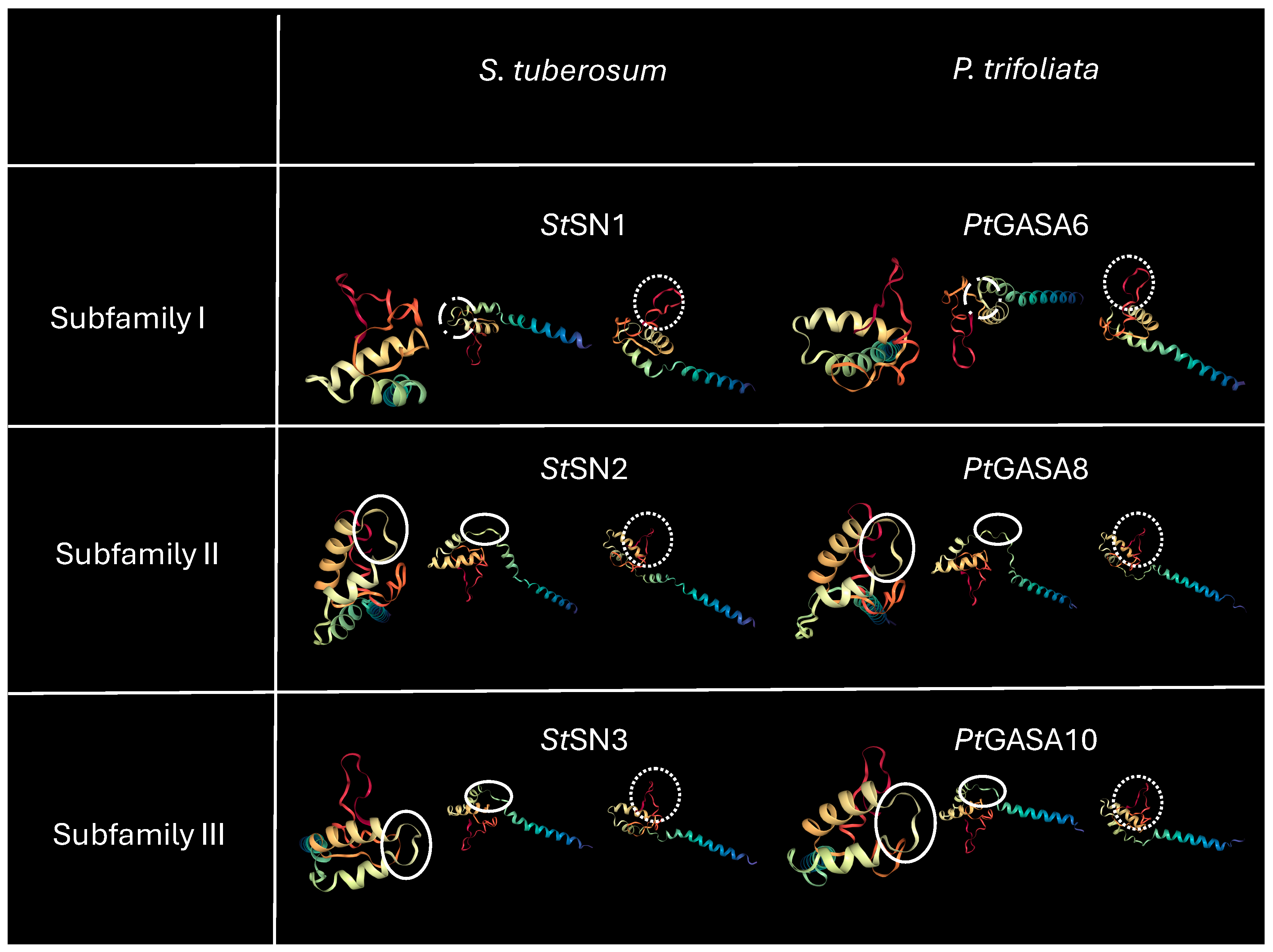

Figure 16 shows a comparison between potato and citrus predicted protein structure of the mentioned protein members representing subfamilies I, II and III in potato and citrus. Comparison to reference potato snakin proteins (

StSN1

, StSN2

, StSN3) evidenced a strong conservation of the tertiary structure despite the large phylogenetic distance between potatoes and citrus, consistently predicting the helix-turn-helix (HTH) fold with cysteine-rich motifs fundamental for antimicrobial peptide (AMP) stability and activity [

7,

39,

44]. However, while for

StSN1/GASA6 and

StSN3/GASA10 comparison, only minor differences were noticed, for

StGASA8 a novel signal peptide with predicted transmembrane properties is present when compared to

StSN2, suggesting a major change in subcellular destination and that significative evolutionary changes occurred even within the same gene orthologs of subfamily II. In other words, despite cross-species conservation, we observed subfamily-specific structural signatures (compact α-helices in subfamily I vs. looser arrangements in II/III), consistent with potential differences in target interaction and mode of action [

5,

11,

44] and suggests functional partitioning along evolutionary lines [

5,

11,

14,

27,

28]. Taken together, structural and phylogenetic evidence suggests that both processes may be involved. On one hand, orthologous pairing to reference potato snakin proteins revealed strong conservation of tertiary structure despite large phylogenetic distance, indicating selection for antimicrobial peptide stability. On the other hand, high allelic and paralog diversity—exemplified by GASA9/GASA9-like—points to neutral drift and sub-functionalization [

7,

39].

Q7: Do multiple defense mechanisms coexist within the GASA family?

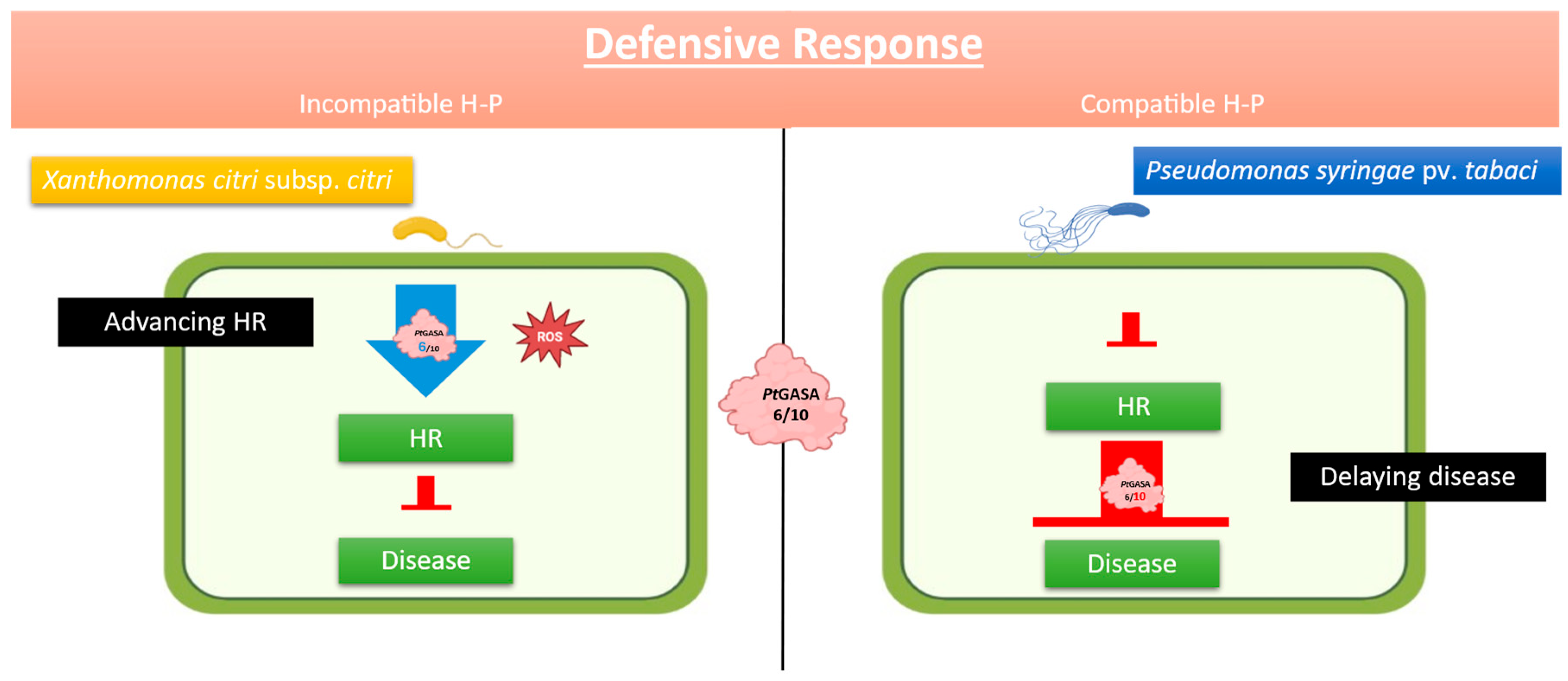

These differences are modeled in

Figure 13 and could indicate that the mechanisms of action are either different or that they are involved in alternative steps of metabolic pathways. Although specific dose-response studies are needed to draw conclusions, it is noteworthy that

PtGASA10 stronger effect in delaying disease necrosis occurred despite its lower expression level (twice as low as that of

PtGASA6). This suggests that

PtGASA10 possesses the remarkable ability to slow down the progression of the disease, even with reduced expression, which may indicate a high functional efficiency, a particularly effective mechanism of action or that it has a longer protein lifetime. In this context, it is noteworthy to mention that

Pseudomonas syringae pv.

tabaci induces the expression of

StSN3 [

5], which is an orthologue of

PtGASA10. This could be an indication that, during infection caused by bacteria, the plant may use this protein to prevent the systemic spread of bacteria in plant tissue.

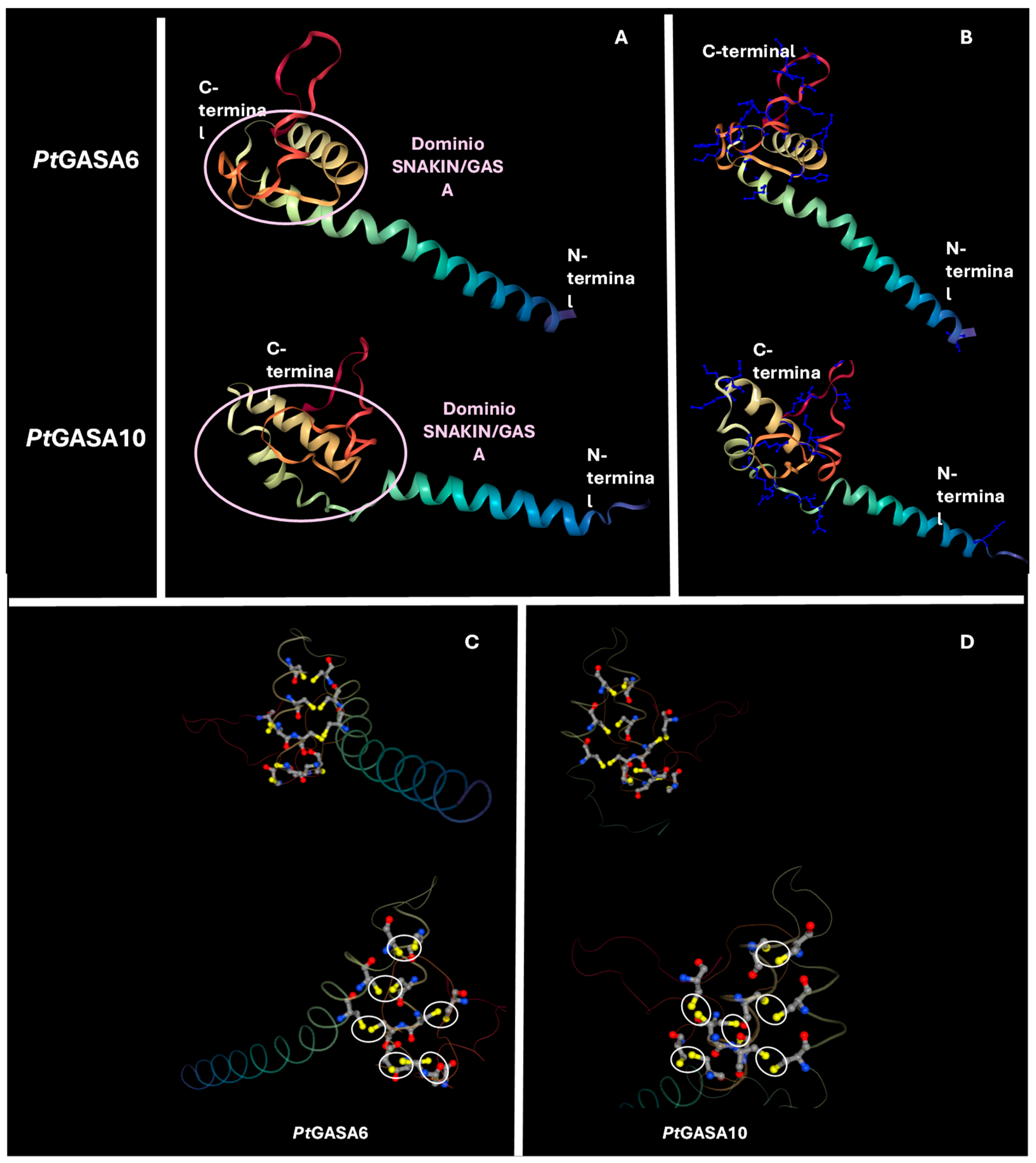

As mentioned before,

PtGASA6 lacks the membrane anchoring site observed for

PtGASA10 structure, suggesting that it could play its defensive role in a different cellular compartment, where it leads to the induction of a stronger HR compared to

PtGASA10. The evolutionary dichotomy is consistent with the subfamily-dependent structural constraints we observed (HTH packing differences) and with literature reports of pleiotropy, where SN/GASA proteins balance developmental roles with immune activation [

1,

7,

49,

50]. Regarding the mechanism involved, we propose a working model in which

PtGASA6 acts as an early amplifier of HR, likely through cellular pathways that escalate ROS bursts, ion fluxes, and localized cell death at infection foci—key components of incompatible responses [

7,

11,

39]. Conversely,

PtGASA10—harboring a predicted membrane targeting signature and a SA-responsive promoter element—appears to retard lesion expansion and limit tissue damage over time. It might operate at the cell wall–apoplast interface, attenuating bacterial colonization, neutralizing extracellular factors, or modulating cell wall integrity pathways; such localization would also enhance direct contact with pathogen cells during early invasion [

11,

14,

39]. However, these speculations based on predictive models (i.e. structural and consensus cis-elements discovery) deserve a note of caution before making conclusive arguments because they must be corroborated experimentally, since discrepancies could occur [

7].

Q8: Are there translational implications for citrus improvement?

From a breeding and biotech perspective,

PtGASA6 and

PtGASA10 emerge as complementary levers: one to reinforce HR priming (

PtGASA6), and another to suppress disease progression (

PtGASA10). Practical routes include: rootstock engineering (overexpression or promoter editing) to confer broad-spectrum protection versus scion modification [

17,

19,

20], CRISPR-based promoter modulation (CRISPR motif editing) to recreate SA/MeJA responsiveness and mobilize defense only under challenge, mitigating pleiotropy [

34,

35,

56,

57], allele mining to discover naturally optimized variants with favorable efficacy–growth trade-offs [

14,

23,

45]. Given the demonstrated sexual compatibility within

Citrus and the recognized HLB tolerance in

P. trifoliata, marker-assisted introgression or cisgenic approaches using

PtGASA alleles provide realistic avenues toward field-relevant resilience [

17,

19,

20,

21].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Bacterial Strains

Citrus plant material was collected from the experimental germplasm bank orchard at EEA INTA Bella Vista (Corrientes Province, Argentina) including Citrus sinensis (sweet orange), C. limon (lemon), Citrumelo (Citrus x paradisi × Poncirus trifoliata) and EEA INTA Concordia (Entre Ríos Province, Argentina) including C. jambhiri (rough lemon), C. limonia (Rangpur), C. warburgiana (New Guinea wild lime), C. aurantium (bitter orange), and P. trifoliata (trifoliate orange). Fully developed trees were used as the tissue source for gene cloning, gene expression analysis, and template origin for transient expression assays.

Nicotiana benthamiana model system was used for agroinfiltration and infection assays. Plants were grown in controlled growth chambers under 22–25 °C, with a 16 h light and 8 h dark photoperiod.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci and Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri strains were used for infection assays. Bacterial suspensions were prepared from 24–48 h cultures in King’s B medium (P. syringae) or nutrient agar (X. citri) and adjusted to OD₆₀₀ = 0.3 (~10⁸ cfu/mL) in 10 mM MgCl₂.

4.2. Identification of GASA Genes/Allelic Variants, PCR Cloning and DNA Sequencing

Genomic and coding sequences (CDS) of Citrus GASA genes were retrieved from the Citrus Genome Database [

36] and NBI [

37]. DNA was extracted from citrus leaf tissue using a standard CTAB method [

38]. DNA quality and concentration were measured using a NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

PCR amplifications were performed using oligonucleotides designed to amplify conserved GASA family sequences (listed in Supplementary

Table 1). PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA), transformed in

E. coli, and sequenced with universal M13F/M13R primers. Three independent clones were sequenced per product. In total, 67 curated genomic variants were obtained from 16 amplified loci and deposited in GenBank (accessions: OP728335 to OQ053292; complete list in

Table 1).

4.3. Structural and Phylogenetic Analyses of GASA Sequences

Protein sequences were aligned using Clustal Omega [

39]. The presence of conserved GASA domains was confirmed using JPred [

40]

, and signal peptides were predicted with SignalP 5.0.

A phylogenetic dendrogram was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method in MEGA11 [

41], with bootstrap support from 1000 replicates. Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Poisson correction model [

42], based on 83 amino acid sequences (194 aligned positions after pairwise deletion).

GASA gene chromosomal positions were mapped using genome data from

C. sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata and

C. limon of Citrus Genome database, and graphic represented using MapChart [

8]. For promoter region analysis, 1500 bp DNA sequences upstream of the ATG site were extracted from Citrus genome Database and the putative cis-regulatory elements were determined with plantCARE database [

43] and classified with TBTools [

44].

4.4. Expression Analysis by RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from citrus and N. benthamiana tissues using TransZol reagent (TransGen Biotech), following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity and purity were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000C, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Genomic DNA was removed by DNase I treatment (Thermo Scientific), and cDNA synthesis was carried out using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific) with random hexamer oligonucleotides and 1 µg of total RNA.

Quantitative PCR reactions were performed using Platinum™ Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen), dNTPs (200 µM each), 3 mM MgCl₂, ROX passive reference dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and SYBR Green I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a final volume of 10 µL. Reactions were run on a StepOnePlus PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

For the analysis of GASA gene expression in citrus tissues, an absolute quantification approach was employed. Gene-specific oligonucleotides were used for each GASA and CsGAPC2 (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatedehydrogenase 2) [

45] as reference for normalization. Standard curves were generated using serial dilutions of purified PCR amplicons cloned for each of the selected GASA genes. These curves were used to determine the absolute copy number of transcripts per ng of cDNA for each gene in floral, young leaf, and mature leaf tissues from five different citrus accessions.

To evaluate gene expression following transient agroinfiltration in

N. benthamiana, a relative quantification method was used. Gene expression levels of PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 were calculated using the comparative Ct method (ΔCt) [

46], normalized to an internal reference (Ubiquitin 3) and expressed as log-2 fold change relative to leaves infiltrated with an empty vector control. Three biological replicates were analyzed per gene construct, and results were represented as mean ± standard errors. Statistical analysis of overexpression was conducted using the FgStatistics package [

47] with paired technical replicates and 5,000 bootstrap resampling cycles. Heatmap was performed with ChiPlot online tool (

https://www.chiplot.online/heatmap.html).

4.5. Transcriptomic Meta-Analysis of Citrus GASA Gene Expression in Public RNA-seq Datasets

We retrieved ten publicly available BioProjects from the NCBI database that investigate gene expression in citrus under Huanglongbing (HLB) infection conditions: PRJNA348468, PRJNA417324, PRJNA574168, PRJNA629966, PRJNA640485, PRJNA645216, PRJNA739184, PRJNA739186, PRJNA755969, and PRJNA780217 (detailed in Supplementary

Table 1). These datasets include multiple tissues, genotypes and time-points post-infection and were selected following the meta-analytic framework described by Machado et al. [

48] for large-scale citrus HLB transcriptome integration.

FASTQ files were processed for quality control with FastQC and trimmed for adapters and low-quality sequences using Trimmomatic [

49]. Filtered reads were aligned to the Citrus clementina genome (v1.0) using STAR v2.7.8a [

50] and gene counts obtained with featureCounts v2.0.1 [

51]. Read counts per sample were normalized using DESeq2 v1.34.0 [

52] to correct for library size differences. Differential gene expression analyses (DESeq2) were run for each experimental comparison within each BioProject, and genes with adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed.

To focus on the SNAKIN/GASA family, we filtered count data by the following C. clementina loci identifiers: Ciclev10017244m.v1.0 (GASA 1), Ciclev10022925m.v1.0 (GASA 2), Ciclev10023012m.v1.0' (GASA 3), Ciclev10033135m.v1.0 (GASA 4), Ciclev10033115m.v1.0 (GASA 5), Ciclev10002979m.v1.0 (GASA 6), Ciclev10002796m.v1.0 (GASA 7), Ciclev10002927m.v1.0 (GASA 8), Ciclev10002984m.v1.0 (GASA 9), Ciclev10013200m.v1.0 (GASA 10), Ciclev10012786m.v1.0 (GASA 11), 'Ciclev10013454m.v1.0 (GASA 12), Ciclev10029695m.v1.0 (GASA 13), Ciclev10006931m.v1.0 (GASA 14), Ciclev10006668m.v1.0 (GASA 15), Ciclev10006310m.v1.0 (GASA 16), Ciclev10006347m.v1.0 (GASA 17), Ciclev10006243m.v1.0 (GASA 18). Normalized counts of these virtual genes were extracted and visualized across genotypes, tissues and time-points via heatmaps, enabling assessment of induction, repression or constitutive expression trends under HLB challenge.

4.6. Transient Overexpression and Infection Assays in N. benthamiana

For Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression, the genes PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 were cloned into the Gateway® binary vector pK2GW7, under the control of the CaMV 35S constitutive promoter. Constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing (UGB-INTA Castelar, Argentina) and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Cultures were grown overnight at 28 °C with shaking (200 rpm) in liquid LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (rifampicin 100 µg/mL, gentamicin 40 µg/mL, spectinomycin 100 µg/mL) and 100 µM acetosyringone. After centrifugation (10 min, 4,000 ×g), bacterial pellets were resuspended in MES buffer and adjusted to an optical density (OD₆₀₀) of 0.6. Fully expanded leaves of 2-month-old N. benthamiana plants were infiltrated using a needleless syringe. Infiltrations were performed in six marked positions per leaf to allow positional normalization of symptom development. For disease progression assay, the pathogenic strain Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci was used to challenge N. benthamiana plants. Bacterial cultures were grown overnight at 28 °C on King’s B solid medium (KBM), washed twice with 10 mM MgCl₂ and adjusted to a final OD₆₀₀ of 0.2, corresponding to approximately 2 × 10⁶ CFU/mL. A final inoculum mix was prepared by combining A. tumefaciens cultures (OD₆₀₀ = 0.6) with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci at the above concentration. This mixture was used to co-infiltrate single leaves (one per plant), always targeting the same six leaf positions. Disease symptoms (necrosis) were recorded from 4 days post-inoculation (dpi) up to 6 dpi, blind to treatment. A Disease Index (DI) was assigned per leaf by averaging scores from the six infiltrated spots. Disease progression was quantified using the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC).

For hypersensitive response (HR) assays, transiently infiltrated

N. benthamiana leaves were challenged with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri, a non-host pathogen. X. citri cultures were grown overnight at 28 °C on Dextrose Nutrient Agar (NAD), then transferred to 10 mM MgCl₂ and agitated for at least 2 h to disrupt biofilm and increase cell suspension homogeneity. The culture was washed twice (7000 rpm, 3 min) and adjusted to OD₆₀₀ = 0.218. For co-infiltration,

A. tumefaciens GV3101 (OD₆₀₀ = 0.6) and Xcc (OD₆₀₀ = 0.109) were mixed in equal volumes and infiltrated into

N. benthamiana leaves as described above. The HR response was scored 6–717 dpi using an HR index assigned to each of the six leaf positions and normalized per plant [

53].

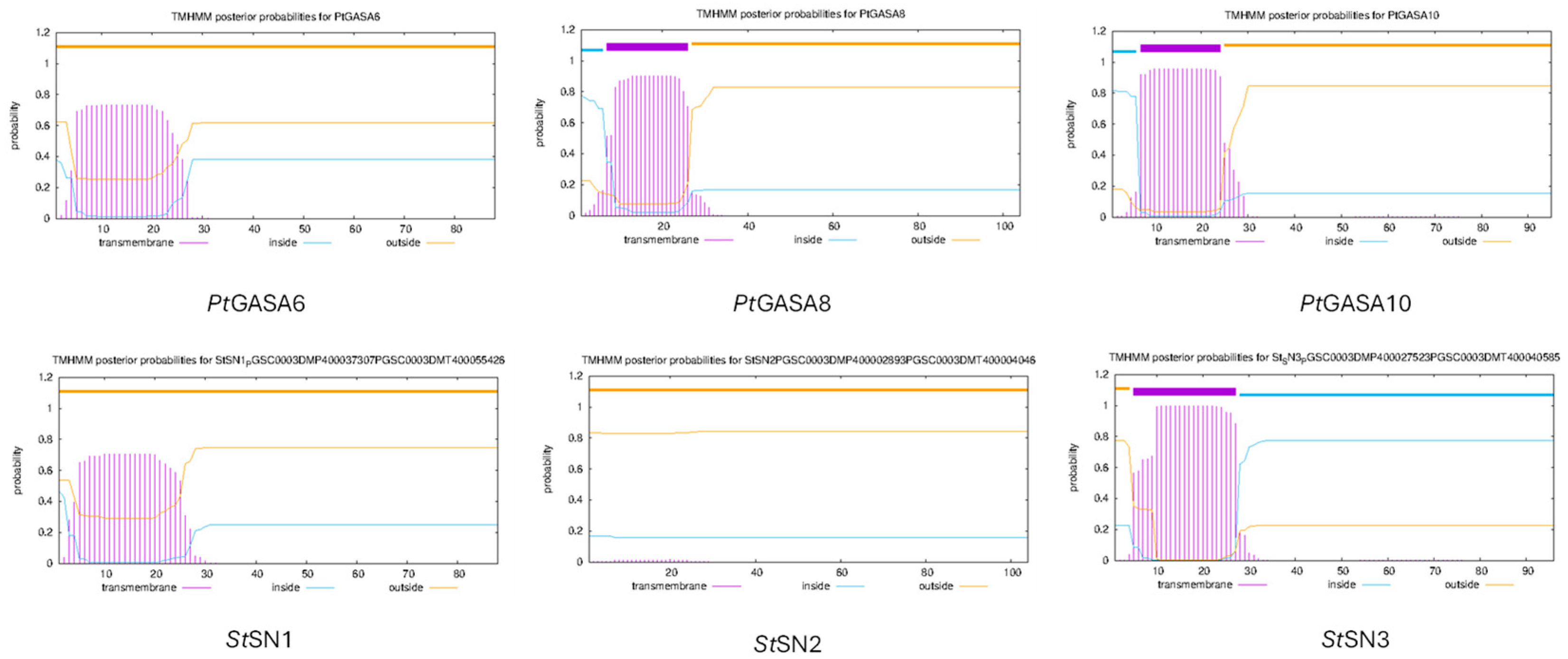

4.7. In Silico Protein Structure Prediction and Subcellular Targeting

Tertiary structures of

PtGASA6,

PtGASA8, and

PtGASA10 were predicted using AlphaFold2 [

54] implemented in ColabFold (v1.5.5) [

31,

32]. Models were visualized with NGL Viewer [

33].

Prediction of transmembrane domains was performed using DeepTMHMM [

55], and signal peptide structure was compared with Solanum tuberosum GASA orthologs (StSN1, StSN2, StSN3) for which subcellular localization is experimentally validated by confocal microscopy, except for StSN2 [

1,

10].

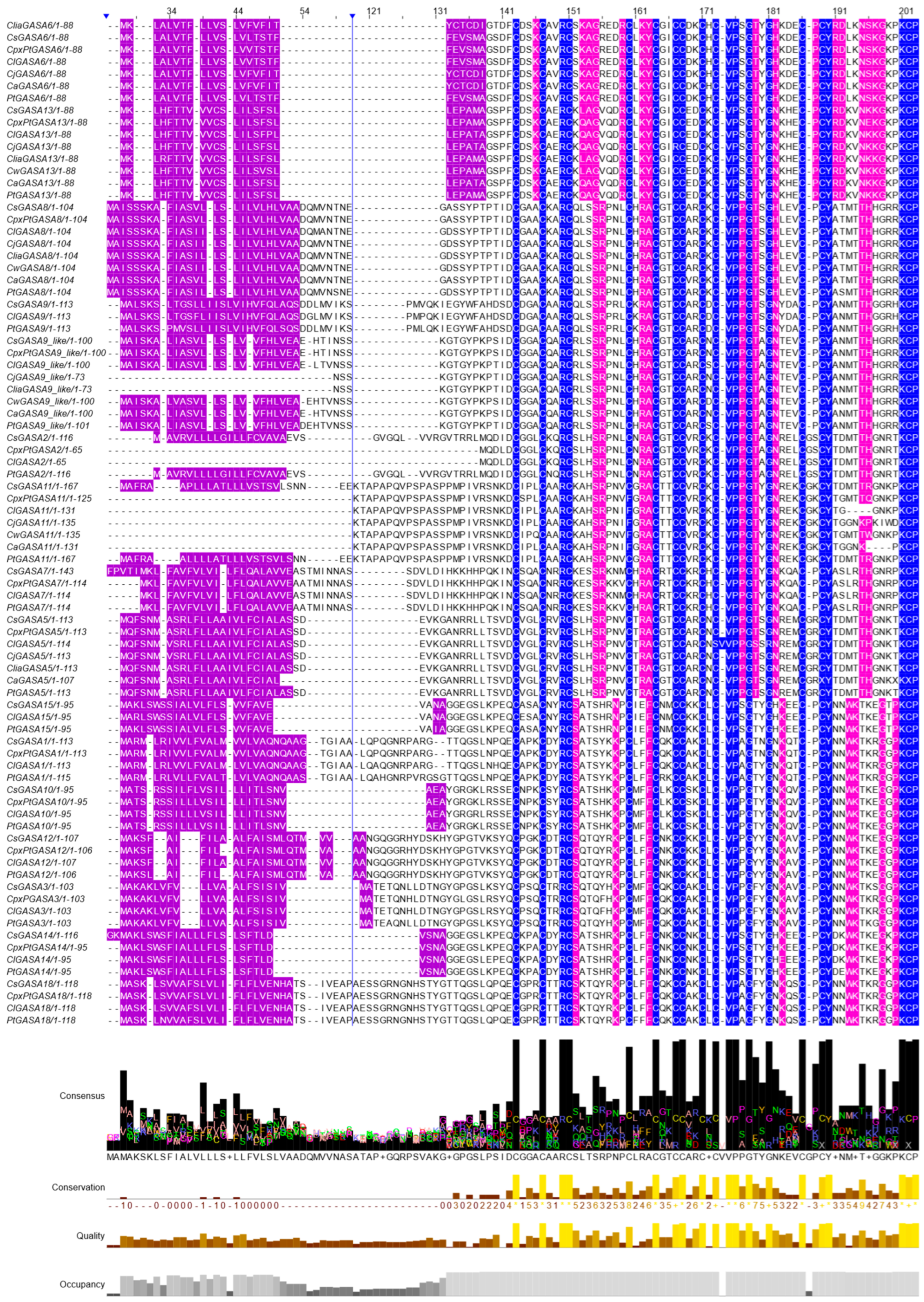

Figure 1.

Multiple alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of citrus GASA protein family performed using Clustal Omega and colored with Jalview software. (a) Conserved sequences of the SNAKIN/GASA domain are marked in blue and include the conserved characteristic array of 12 cysteines. Residues used to classify each member into a subfamily are shown in magenta, and putative signal peptide–associated sequences, according to Nahirñak et al. , are shown in violet. The vertical blue lines indicated with arrows represent variable regions that were hidden for illustrative purposes. (b) Highly conserved amino acids obtained from the ClustalO alignment in Jalview are shown and include the twelve cysteines, together with the final C-terminal KCP motif.

Figure 1.

Multiple alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of citrus GASA protein family performed using Clustal Omega and colored with Jalview software. (a) Conserved sequences of the SNAKIN/GASA domain are marked in blue and include the conserved characteristic array of 12 cysteines. Residues used to classify each member into a subfamily are shown in magenta, and putative signal peptide–associated sequences, according to Nahirñak et al. , are shown in violet. The vertical blue lines indicated with arrows represent variable regions that were hidden for illustrative purposes. (b) Highly conserved amino acids obtained from the ClustalO alignment in Jalview are shown and include the twelve cysteines, together with the final C-terminal KCP motif.

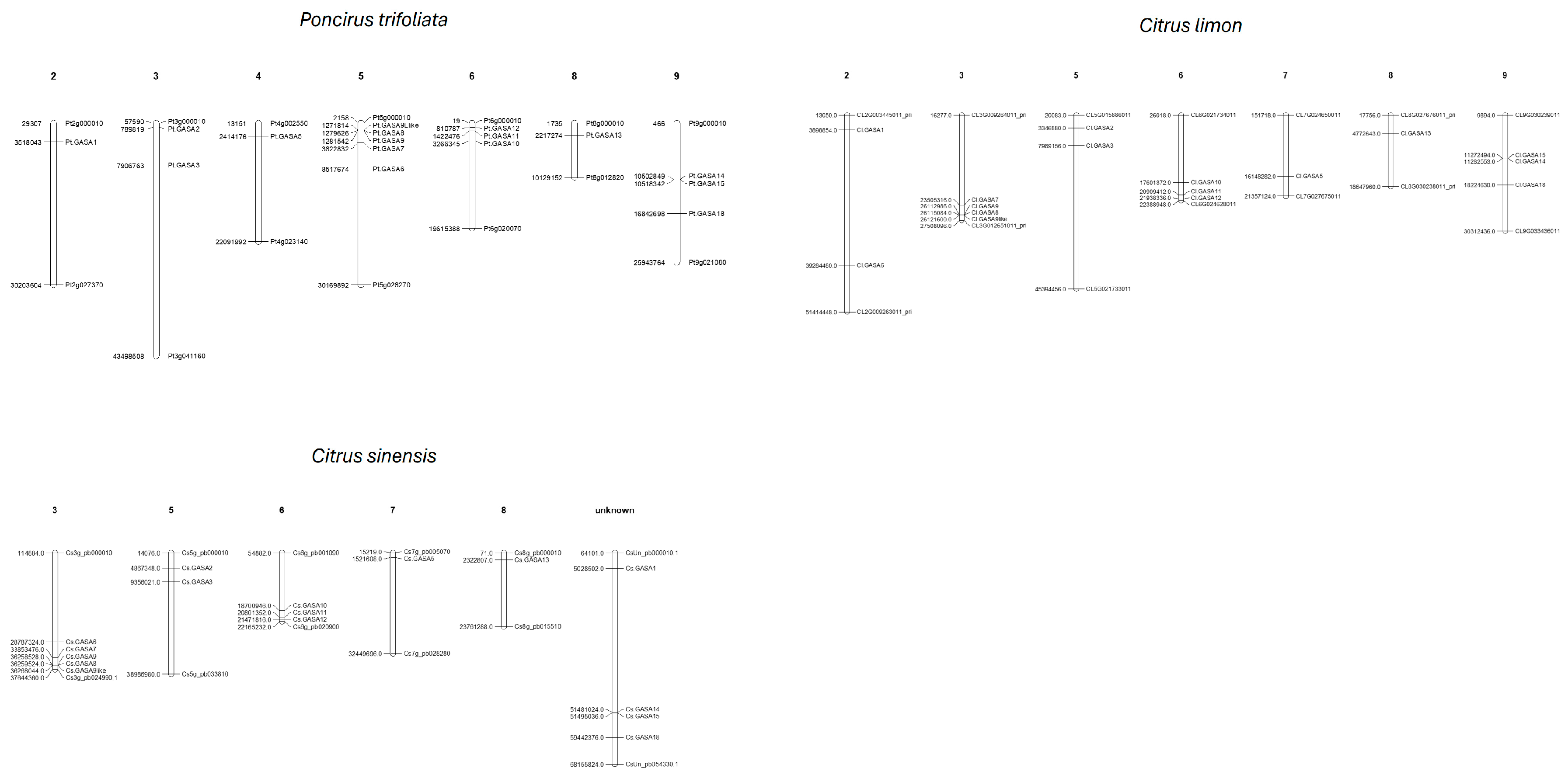

Figure 2.

Genomic distribution of GASA genes in chromosomes from P. trifoliata, C. limon and C. sinensis were performed using MapChart .

Figure 2.

Genomic distribution of GASA genes in chromosomes from P. trifoliata, C. limon and C. sinensis were performed using MapChart .

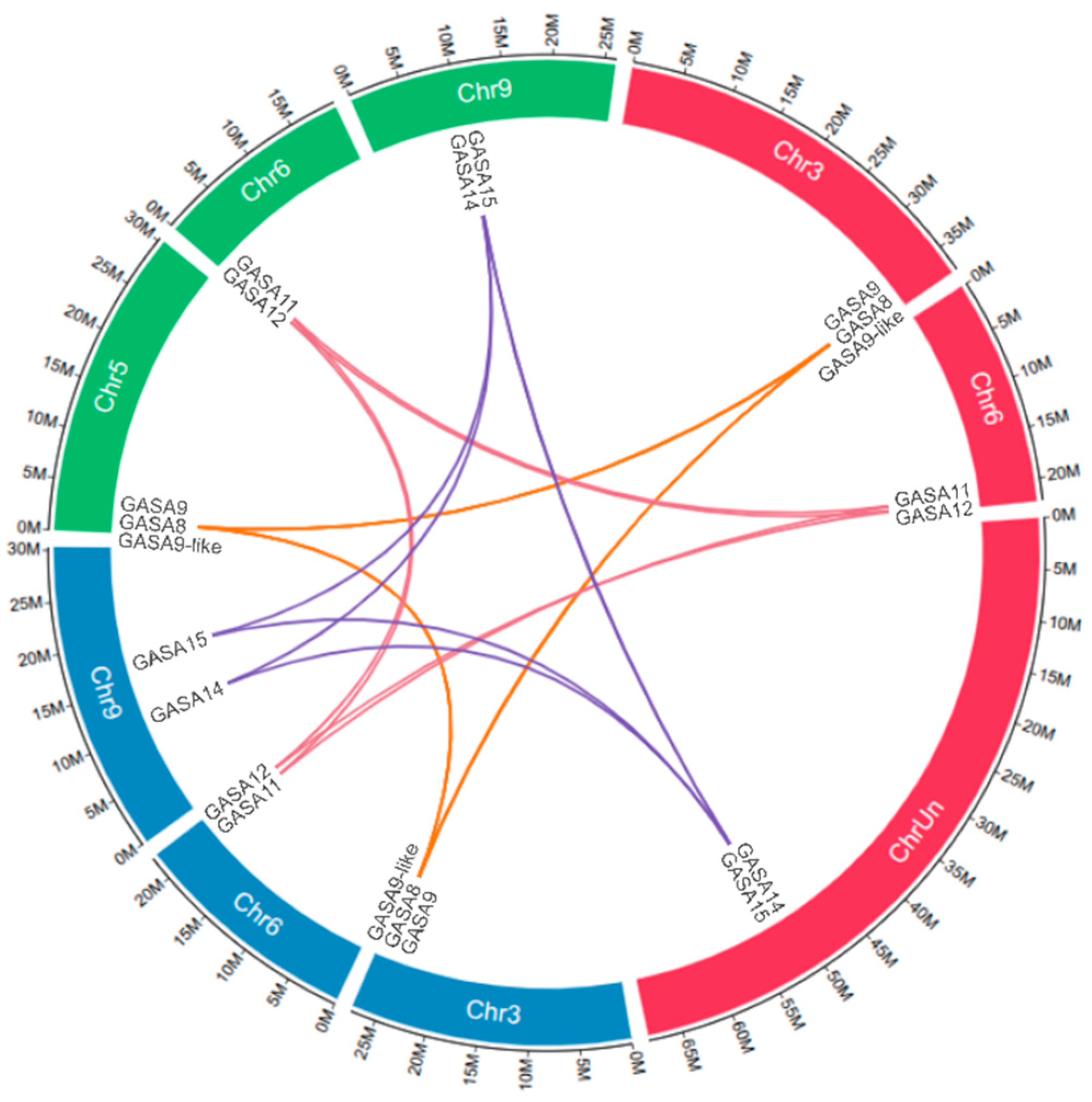

Figure 3.

Syntenic analysis of GASA family genes in Citrus sinensis, Citrus limon and Poncirus trifoliata. Genes displayed on circular bar-blocks indicate the chromosomal position: Citrus sinensis (red), Poncirus trifoliata (green), and Citrus limon (blue) chromosomes. Violet, yellow, and red color lines represent duplicated pairs.

Figure 3.

Syntenic analysis of GASA family genes in Citrus sinensis, Citrus limon and Poncirus trifoliata. Genes displayed on circular bar-blocks indicate the chromosomal position: Citrus sinensis (red), Poncirus trifoliata (green), and Citrus limon (blue) chromosomes. Violet, yellow, and red color lines represent duplicated pairs.

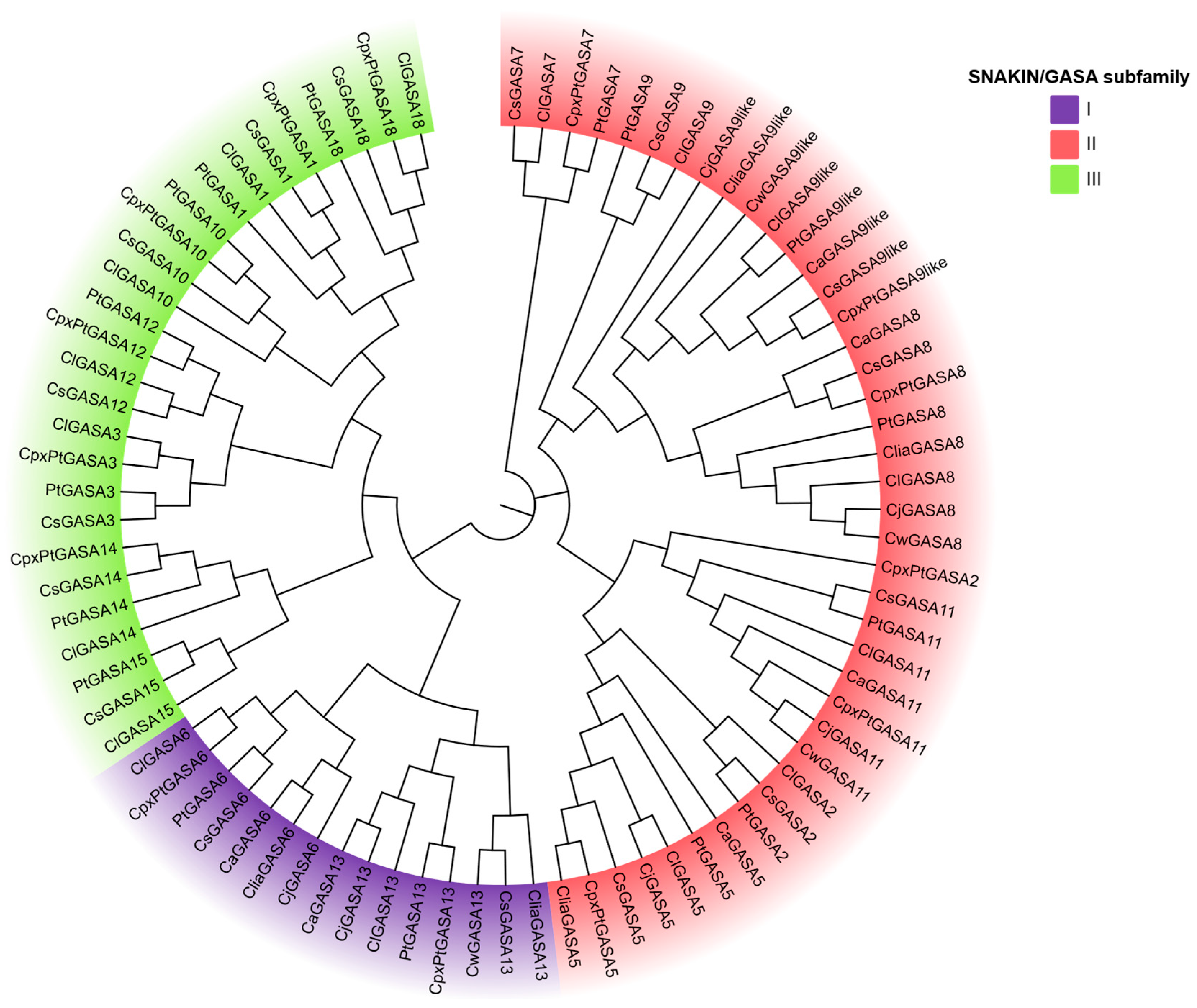

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of citrus GASA proteins generated using MEGA 11 with the Neighbor-Joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates. A colored version was produced using the online tool ChiPlot tool. Subfamilies are indicated with colors: subfamily I in violet, subfamily II in magenta, and subfamily III in green. The varieties included in this analysis are: Cs, Citrus sinensis; Cp × Pt, Citrumelo (Citrus × paradisi × Citrus trifoliata); Cl, Citrus limon; Pt, Poncirus trifoliata; Cj, Citrus jhambiri; Clia, Citrus limonia; Cw, Citrus warburgiana; Ca, Citrus aurantium.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of citrus GASA proteins generated using MEGA 11 with the Neighbor-Joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates. A colored version was produced using the online tool ChiPlot tool. Subfamilies are indicated with colors: subfamily I in violet, subfamily II in magenta, and subfamily III in green. The varieties included in this analysis are: Cs, Citrus sinensis; Cp × Pt, Citrumelo (Citrus × paradisi × Citrus trifoliata); Cl, Citrus limon; Pt, Poncirus trifoliata; Cj, Citrus jhambiri; Clia, Citrus limonia; Cw, Citrus warburgiana; Ca, Citrus aurantium.

Figure 5.

Representative heatmap of gene expression obtained through absolute RT-qPCR from floral tissue (purple), juvenile (magenta), and mature leaf (green) of citrus cultivars C. reticulata var ‘Clemenule’, Citrus limon var. ‘Eureka’, Citrus limonia (Rangpur), Citrange Troyer, Poncirus trifoliata. The heatmap, generated using the Chiplot tool, employs a color scale ranging from dark blue, representing minimum expression, to dark red, representing maximum expression. On the left, the analyzed GASA genes are shown along with their corresponding subfamily classification (I, II, or III).

Figure 5.

Representative heatmap of gene expression obtained through absolute RT-qPCR from floral tissue (purple), juvenile (magenta), and mature leaf (green) of citrus cultivars C. reticulata var ‘Clemenule’, Citrus limon var. ‘Eureka’, Citrus limonia (Rangpur), Citrange Troyer, Poncirus trifoliata. The heatmap, generated using the Chiplot tool, employs a color scale ranging from dark blue, representing minimum expression, to dark red, representing maximum expression. On the left, the analyzed GASA genes are shown along with their corresponding subfamily classification (I, II, or III).

Figure 6.

Heatmap showing the log2 fold change of 18 citrus GASA genes across public HLB-related RNA-seq BioProjects. Each cell represents the log₂ fold change of a given GASA gene in a specific contrast. Red shades indicate GASA overexpression (positive log₂FC), blue shades indicate under-expression (negative log₂FC) and near-white cells correspond to little or no change. Empty cells reflect cases where the corresponding GASA gene was not detected in that dataset or lacked sufficient read support to generate a reliable log₂FC estimate. In

Supplementary Table S1 there is a description of the experimental approach of each BioProject and their specific references. In

Supplementary Figure S1, some specific methodological issues regarding bioinformatic gene annotations performed by individual Bioprojects for GASA16-18 are shown.

Figure 6.

Heatmap showing the log2 fold change of 18 citrus GASA genes across public HLB-related RNA-seq BioProjects. Each cell represents the log₂ fold change of a given GASA gene in a specific contrast. Red shades indicate GASA overexpression (positive log₂FC), blue shades indicate under-expression (negative log₂FC) and near-white cells correspond to little or no change. Empty cells reflect cases where the corresponding GASA gene was not detected in that dataset or lacked sufficient read support to generate a reliable log₂FC estimate. In

Supplementary Table S1 there is a description of the experimental approach of each BioProject and their specific references. In

Supplementary Figure S1, some specific methodological issues regarding bioinformatic gene annotations performed by individual Bioprojects for GASA16-18 are shown.

Figure 7.

Illustrative photo ensembles of individual representative leaves of N. benthamiana infected with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci transiently overexpressing PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or the control at 6 (A), 8 (B), and 11 (C) post-infection. Each leaf was co-infiltrated in the same six positions with A. tumefaciens GV3101 expressing the indicated genes and the pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci.

Figure 7.

Illustrative photo ensembles of individual representative leaves of N. benthamiana infected with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci transiently overexpressing PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or the control at 6 (A), 8 (B), and 11 (C) post-infection. Each leaf was co-infiltrated in the same six positions with A. tumefaciens GV3101 expressing the indicated genes and the pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci.

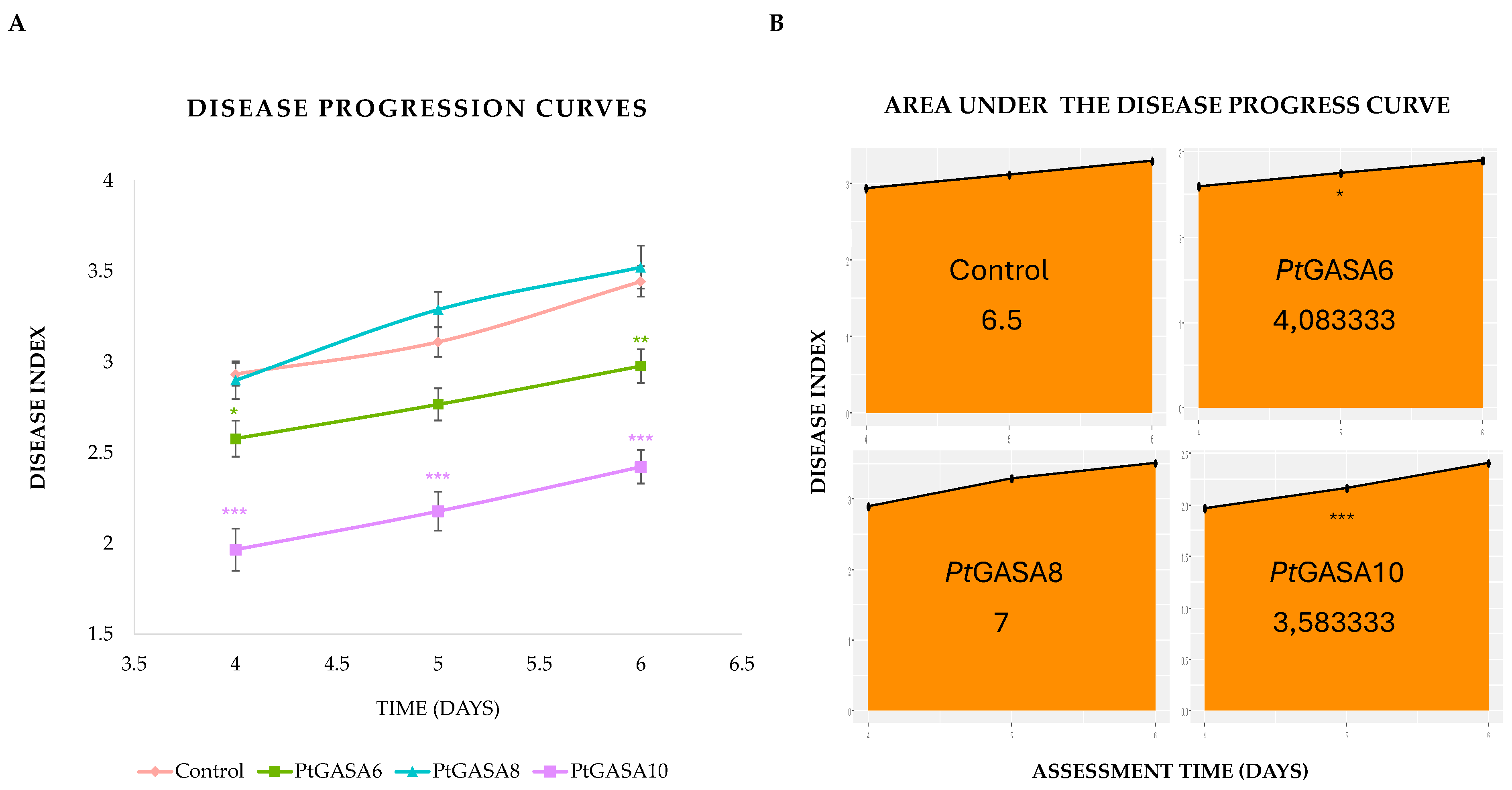

Figure 8.

Time course of disease index progression. Evaluation of disease development on days 4, 5, and 6 post-challenge with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in leaves overexpressing the genes PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10, or control. The non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction, adjusting p-values by the Bonferroni method relative to the control. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 8.

Time course of disease index progression. Evaluation of disease development on days 4, 5, and 6 post-challenge with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in leaves overexpressing the genes PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10, or control. The non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction, adjusting p-values by the Bonferroni method relative to the control. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 9.

Time course of disease AUDPC progression. Evaluation of disease development caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in leaves overexpressing PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or control. (A) Disease progression curves showing the disease index over time for PtGASA6, PtGASA8, PtGASA10 and control. It is represented in green, light blue, purple, and magenta, respectively. (B) Area Under the Disease Progress Curve for the control and PtGASA6 (upper panel), PtGASA8 and PtGASA10 (lower panel), respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction and Bonferroni adjustment relative to the control. Significance levels are indicated by asterisks: * p < 0.05; *** * p < 0.001.

Figure 9.

Time course of disease AUDPC progression. Evaluation of disease development caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci in leaves overexpressing PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or control. (A) Disease progression curves showing the disease index over time for PtGASA6, PtGASA8, PtGASA10 and control. It is represented in green, light blue, purple, and magenta, respectively. (B) Area Under the Disease Progress Curve for the control and PtGASA6 (upper panel), PtGASA8 and PtGASA10 (lower panel), respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction and Bonferroni adjustment relative to the control. Significance levels are indicated by asterisks: * p < 0.05; *** * p < 0.001.

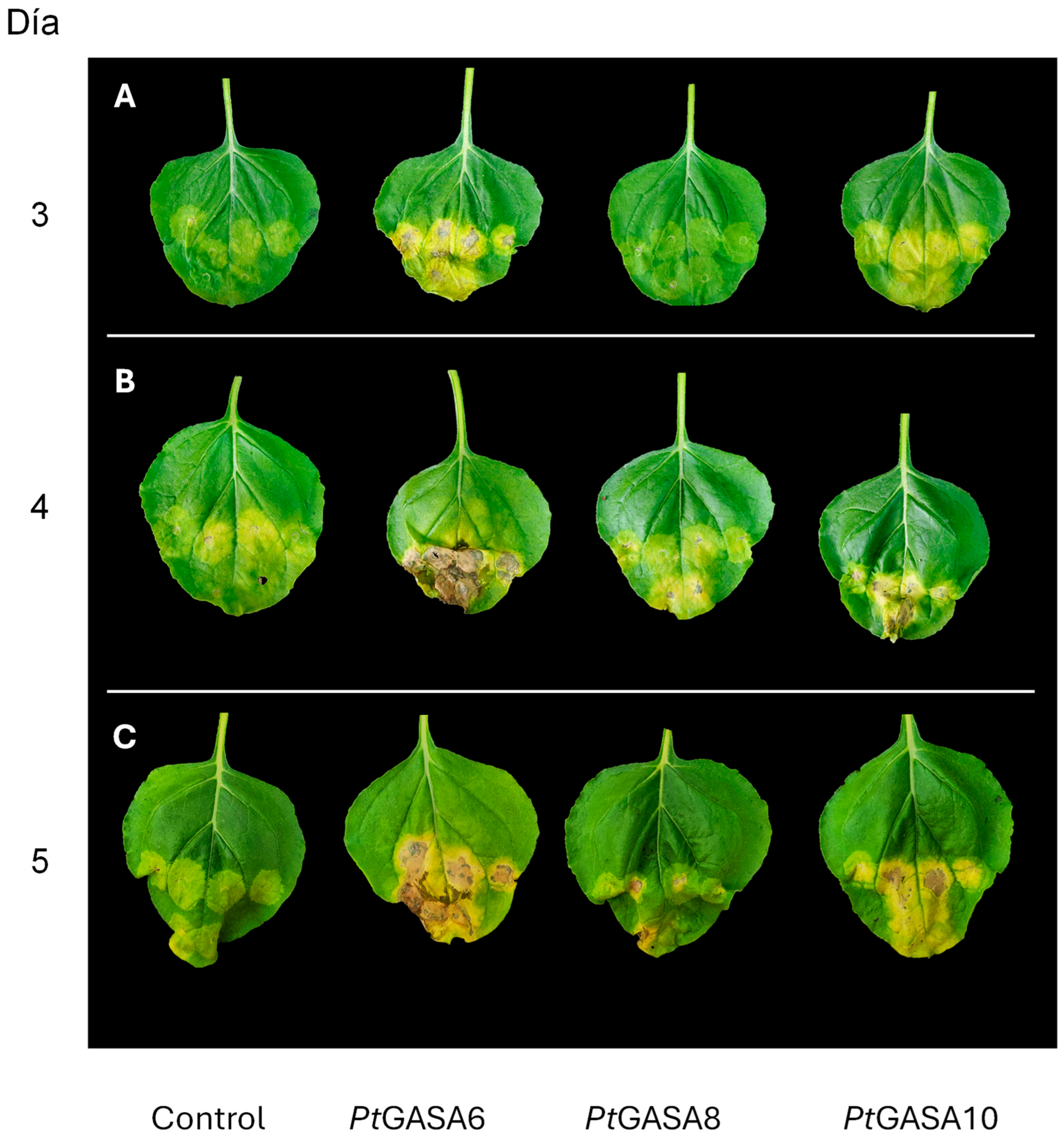

Figure 10.

Demonstrative photograph ensemble of representative individual leaves of N. benthamiana after transient overexpression of PtGASA6, PtGASA8, PtGASA10 (or the control) showing the hypersensitive response generated by challenging with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri at (A), 4 (B), and 5 (C) days post-infection.

Figure 10.

Demonstrative photograph ensemble of representative individual leaves of N. benthamiana after transient overexpression of PtGASA6, PtGASA8, PtGASA10 (or the control) showing the hypersensitive response generated by challenging with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri at (A), 4 (B), and 5 (C) days post-infection.

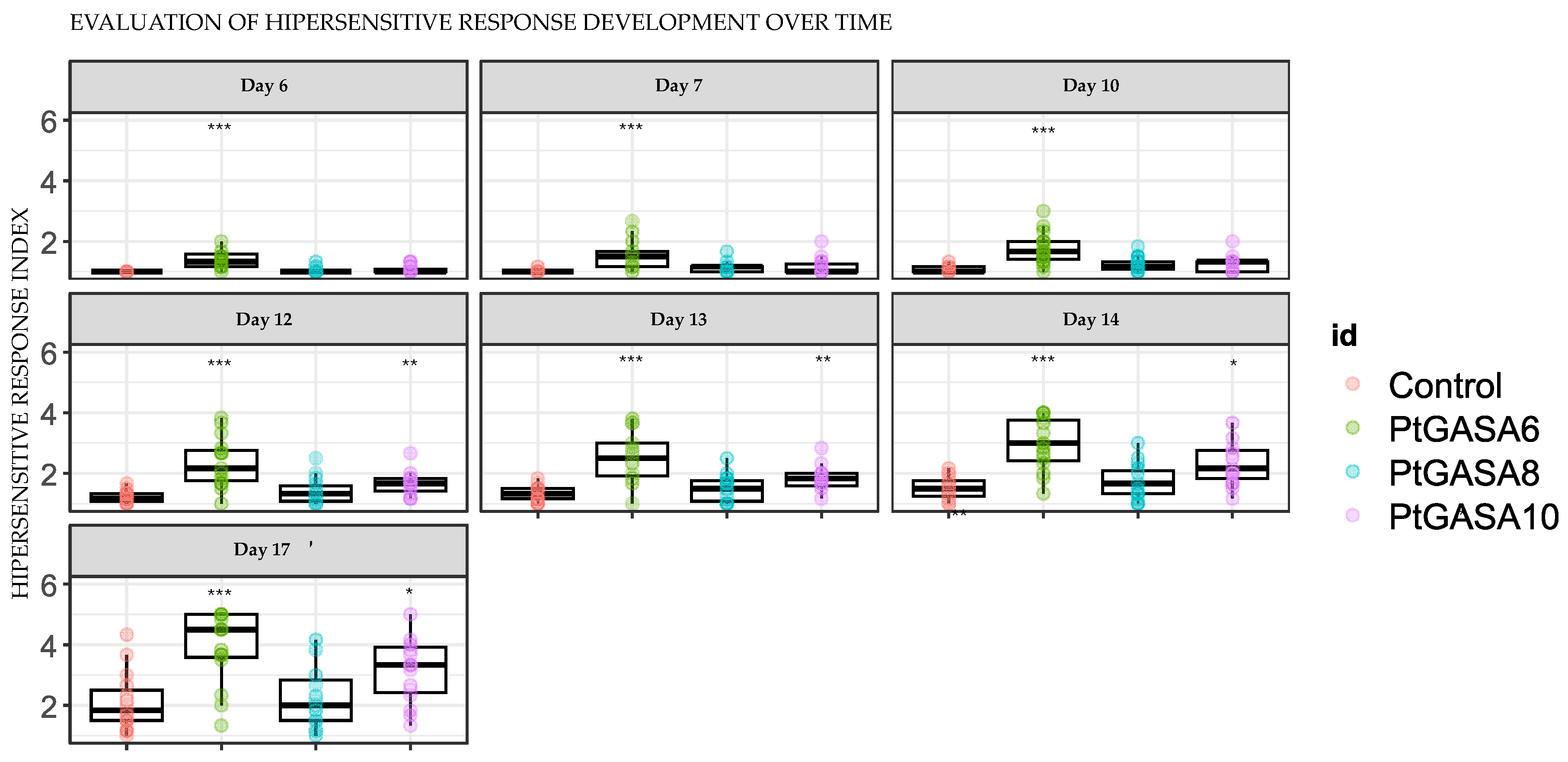

Figure 11.

Time course development of hypersensitive response, from days 6 to 17, post-challenge. The leaves overexpressing the genes PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or the control were inoculated with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. The overexpressing leaves and control are represented in green, light blue, purple, and magenta, respectively. The non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction, adjusting p-values by the Bonferroni method relative to the control. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 11.

Time course development of hypersensitive response, from days 6 to 17, post-challenge. The leaves overexpressing the genes PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or the control were inoculated with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. The overexpressing leaves and control are represented in green, light blue, purple, and magenta, respectively. The non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction, adjusting p-values by the Bonferroni method relative to the control. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

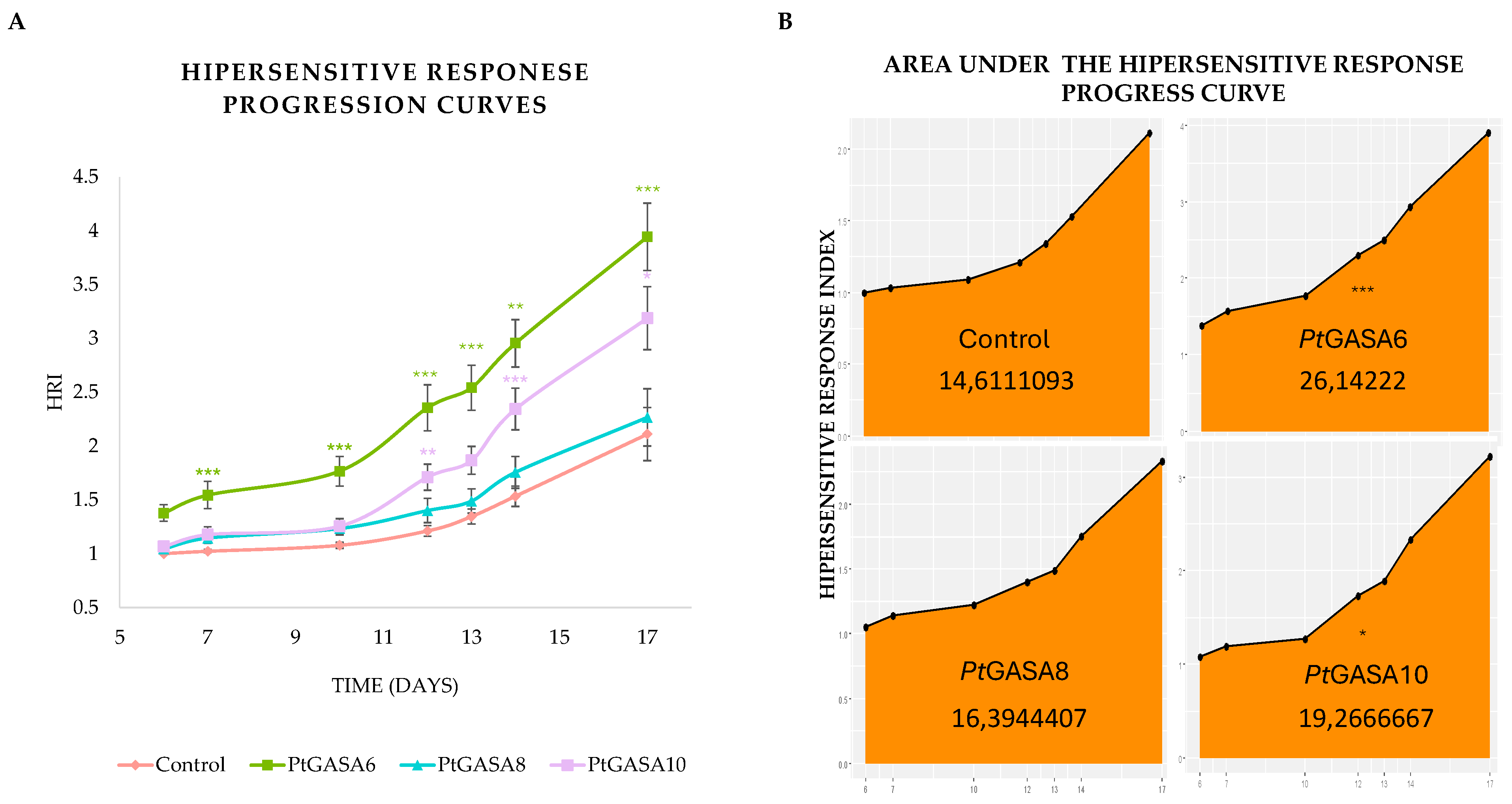

Figure 12.

Evaluation of hypersensitive response (HR) development caused by Xanthomonas citri susp citri in leaves overexpressing PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or control infected with (A) Hypersensitive response progression curve using the HR index (HRI) as a function of time. The overexpressing leaves and control are represented in green, light blue, purple, and pink, respectively. (B) Area Under the hypersensitive response progress curve (AUHRPC). Non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction, and p-values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method relative to the control. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 12.

Evaluation of hypersensitive response (HR) development caused by Xanthomonas citri susp citri in leaves overexpressing PtGASA6, PtGASA8, and PtGASA10 or control infected with (A) Hypersensitive response progression curve using the HR index (HRI) as a function of time. The overexpressing leaves and control are represented in green, light blue, purple, and pink, respectively. (B) Area Under the hypersensitive response progress curve (AUHRPC). Non-parametric statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with continuity correction, and p-values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method relative to the control. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 13.

An illustrative model representing the events observed during infections in which PtGASA6 and PtGASA10 were overexpressed under incompatible pathosystem with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (left panel) and compatible interaction with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci (right panel). For both genes, an earlier hypersensitive response was observed, as well as a delayed onset of necrosis development because of the disease. A stronger enhancement was observed for PtGASA6 in advancing hypersensitive response and PtGASA10 in delaying disease.

Figure 13.

An illustrative model representing the events observed during infections in which PtGASA6 and PtGASA10 were overexpressed under incompatible pathosystem with Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (left panel) and compatible interaction with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tabaci (right panel). For both genes, an earlier hypersensitive response was observed, as well as a delayed onset of necrosis development because of the disease. A stronger enhancement was observed for PtGASA6 in advancing hypersensitive response and PtGASA10 in delaying disease.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation of conserved motifs in subfamilies I, II, and III of the SNAKIN/GASA family from S. tuberosum (left) and P. trifoliata (right). The first row corresponds to subfamily I, comprising StSN1 and PtGASA6; the second to subfamily II, including StSN2 and PtGASA8; and the third to subfamily III, with StSN3 and PtGASA10. The motif common to all subfamilies and species (P. trifoliata and S. tuberosum) is indicated by a dotted line (·······). The motif characteristic of subfamily I, shown with a dash-dot line (--·--), confers a more compact arrangement with condensed α-helices. In contrast, the motifs present in subfamilies II and III, represented by a solid line (──), promote a looser structure with more separated α-helices.

Figure 14.

Schematic representation of conserved motifs in subfamilies I, II, and III of the SNAKIN/GASA family from S. tuberosum (left) and P. trifoliata (right). The first row corresponds to subfamily I, comprising StSN1 and PtGASA6; the second to subfamily II, including StSN2 and PtGASA8; and the third to subfamily III, with StSN3 and PtGASA10. The motif common to all subfamilies and species (P. trifoliata and S. tuberosum) is indicated by a dotted line (·······). The motif characteristic of subfamily I, shown with a dash-dot line (--·--), confers a more compact arrangement with condensed α-helices. In contrast, the motifs present in subfamilies II and III, represented by a solid line (──), promote a looser structure with more separated α-helices.

Figure 15.

Three-dimensional structure of PtGASA6 and PtGASA10. (A) The C-terminus and N-terminus and the location of the SNAKIN/GASA domain are indicated. (B) Positively charged amino acids (arginine, lysine or histidine) are shown in blue, mainly located within the HTH region. (C) Three-dimensional structure of PtGASA6 and (D) PtGASA10 showing the 6 in silico–disulfide bonds predicted. Cysteine residues are highlighted in yellow. The predicted bonds are indicated by white circles.

Figure 15.

Three-dimensional structure of PtGASA6 and PtGASA10. (A) The C-terminus and N-terminus and the location of the SNAKIN/GASA domain are indicated. (B) Positively charged amino acids (arginine, lysine or histidine) are shown in blue, mainly located within the HTH region. (C) Three-dimensional structure of PtGASA6 and (D) PtGASA10 showing the 6 in silico–disulfide bonds predicted. Cysteine residues are highlighted in yellow. The predicted bonds are indicated by white circles.

Figure 16.

Topology of proteins PtGASA6, PtGASA8, PtGASA10, StSN1, StSN2 and StSN3. The purple line indicates the probability that a segment corresponds to a transmembrane affinity region. The light blue line at the top of the plot represents the probability regions are oriented toward the cell interior (cytoplasmic). The yellow line marks the regions probably located on the outer side of the cell (extracellular). The predicted topology suggests that PtGASA8 and PtGASA10 may contain a membrane-anchoring site (transmembrane region).

Figure 16.

Topology of proteins PtGASA6, PtGASA8, PtGASA10, StSN1, StSN2 and StSN3. The purple line indicates the probability that a segment corresponds to a transmembrane affinity region. The light blue line at the top of the plot represents the probability regions are oriented toward the cell interior (cytoplasmic). The yellow line marks the regions probably located on the outer side of the cell (extracellular). The predicted topology suggests that PtGASA8 and PtGASA10 may contain a membrane-anchoring site (transmembrane region).

Table 1.

Identification and characterization of citrus GASA genes in 8 different citrus species: Cs (Citrus sinensis), CpxPt (Citrus paradisi x Poncirus trifoliata), Cl (Citrus limon), Cj (Citrus jambhiri), Clia (Citrus limonia), Cw (Citrus warburgiana), Ca (Citrus aurantium) and Pt (Poncirus trifoliata). CDS: coding sequence.

Table 1.

Identification and characterization of citrus GASA genes in 8 different citrus species: Cs (Citrus sinensis), CpxPt (Citrus paradisi x Poncirus trifoliata), Cl (Citrus limon), Cj (Citrus jambhiri), Clia (Citrus limonia), Cw (Citrus warburgiana), Ca (Citrus aurantium) and Pt (Poncirus trifoliata). CDS: coding sequence.

| |

Sequence Name |

Gene ID |

Exons |

CDS

(bp) |

Protein (aa) |

| Subfamily I |

CsGASA6 |

LOC102614811 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CpxPtGASA6 |

OP728331 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

ClGASA6 |

OP728332 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CjGASA6 |

OP728333 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CliaGASA6 |

OP728334 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CaGASA6 |

OP728335 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

PtGASA6 |

OP728336 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CsGASA13 |

LOC102619143 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CpxPtGASA13 |

OP791894 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

ClGASA13 |

OP791895 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CjGASA13 |

OP791896 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CliaGASA13 |

OP791897 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CwGASA13 |

OP791898 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

CaGASA13 |

OP791899 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| |

PtGASA13 |

OP791900 |

2 |

267 |

88 |

| Subfamily II |

CsGASA8

|

LOC102628220 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

CpxPtGASA8 |

OP947003 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

ClGASA8 |

OP947004 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

CjGASA8 |

OP947005 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

CliaGASA8 |

OP947006 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

CwGASA8 |

OP947007 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

CaGASA8 |

OP947008 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

PtGASA8 |

OP947009 |

3 |

315 |

104 |

| |

CsGASA9 |

LOC102627925 |

3 |

342 |

113 |

| |

ClGASA9 |

OP946990 |

3 |

342 |

113 |

| |

PtGASA9 |

OP946991 |

3 |

342 |

113 |

| |

CsGASA9-like

|

LOC102628717 |

3 |

303 |

100 |

| |

CpxPtGASA9-like |

OQ053283 |

3 |

303 |

100 |

| |

ClGASA9-like |

OQ053284 |

3 |

303 |

100 |

| |

CjGASA9-like |

OQ053285 |

3 |

226 |

73 (partial CDS) |

| |

CliaGASA9-like |

OQ053286 |

3 |

226 |

73 (partial CDS) |

| |

CwGASA9-like |

OQ053287 |

3 |

303 |

100 |

| |

CaGASA9-like |

OQ053288 |

3 |

303 |

100 |

| |

PtGASA9-like |

OQ053289 |

3 |

306 |

101 |

| |

CsGASA2

|

LOC102628910 |

4 |

351 |

116 |

| |

CpxPtGASA2 |

OP946981 |

2 |

213 |

65 (partial CDS) |

| |

ClGASA2 |

OP946982 |

4 |

213 |

65 (partial CDS) |

| |

PtGASA2 |

OP946983 |

|

351 |

116 |

| |

CsGASA11 |

LOC102631482 |

4 |

504 |

167 |

| |

CpxPtGASA11 |

OP946975 |

2 |

408 |

125 (partial CDS) |

| |

ClGASA11 |

OP946976 |

2 |

396 |

130 (partial CDS) |

| |

CliaGASA11 |

OP946977 |

2 |

396 |

135 (partial CDS) |

| |

CwGASA11 |

OP946978 |

2 |

408 |

135 (partial CDS) |

| |

CaGASA11 |

OP946979 |

2 |

396 |

130 (partial CDS) |

| |

PtGASA11 |

OP946980 |

4 |

504 |

167 |

| |

CsGASA7 |

LOC102625142 |

4 |

432 |

143 |

| |

CpxPtGASA7 |

OP947000 |

4 |

345 |

114 |

| |

ClGASA7 |

OP947001 |

4 |

345 |

114 |

| |

PtGASA7 |

OP947002 |

4 |

345 |

114 |

| |

CsGASA5 |

LOC102625142 |

3 |

324 |

113 |

| |

CpxPtGASA5 |

OP946984 |

3 |

324 |

113 |

| |

ClGASA5 |

OP946985 |

3 |

327 |

114 |

| |

CjGASA5 |

OP946986 |

3 |

324 |

113 |

| |

CliaGASA5 |

OP946987 |

3 |

324 |

113 |

| |

CaGASA5 |

OP946988 |

3 |

324 |

113 |

| |

PtGASA5 |

OP946989 |

3 |

324 |

113 |

| Subfamily III |

CsGASA15

|

LOC102625588 |

3 |

286 |

95 |

|

ClGASA15 |

OP946995 |

3 |

285 |

95 |

|

PtGASA15 |

OP946996 |

3 |

285 |

95 |

|

CsGASA1 |

LOC102629636 |

4 |

342 |

113 |

|

CpxPtGASA1 |

OQ053290 |

4 |

342 |

113 |

|

ClGASA1 |

OQ053291 |

4 |

342 |

113 |

|

PtGASA1 |

OQ053292 |

4 |

348 |

115 |

|

CsGASA10 |

LOC102618255 |

3 |

288 |

95 |

|

CpxPtGASA10 |

OP830506 |

3 |

288 |

95 |

|

ClGASA10 |

OP830507 |

3 |

288 |

95 |

|

PtGASA10 |

OP830508 |

3 |

288 |

95 |

|

CsGASA12 |

LOC102611788 |

4 |

324 |

107 |

|

CpxPtGASA12 |

OQ053280 |

4 |

321 |

106 |

|

ClGASA12 |

OQ053281 |

4 |

324 |

107 |

|

PtGASA12 |

OQ053282 |

4 |

321 |

106 |

|

CsGASA3 |

LOC102626694 |

3 |

312 |

103 |

|

CpxPtGASA3 |

OP946997 |

3 |

312 |

103 |

|

ClGASA3 |

OP946998 |

3 |

312 |

103 |

|

PtGASA3 |

OP946999 |

2 |

312 |

103 |

|

CsGASA14 |

LOC102625321 |

3 |

351 |

116 |

|

CpxPtGASA14 |

OP946992 |

3 |

286 |

95 |

|

ClGASA14 |

OP946993 |

3 |

285 |

95 |

|

PtGASA14 |

OP946994 |

3 |

285 |

95 |

|

CsGASA18 |

LOC102630614 |

4 |

357 |

118 |

|

CpxPtGASA18 |

OP830509 |

4 |

357 |

118 |

|

ClGASA18 |

OP830510 |

4 |

357 |

118 |

|

PtGASA18 |

OP830511 |

4 |

357 |

118 |

Table 2.

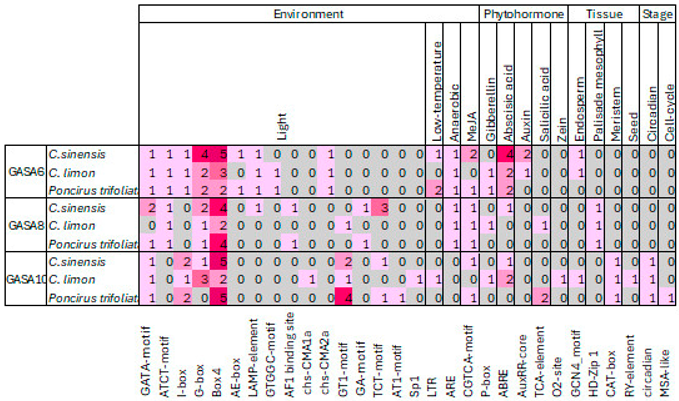

Predicted cis-regulatory elements in GASA6, 8 and 10 predicted promoter sequences from C. sinensis, C. limon and P. trifoliata.

Table 2.

Predicted cis-regulatory elements in GASA6, 8 and 10 predicted promoter sequences from C. sinensis, C. limon and P. trifoliata.