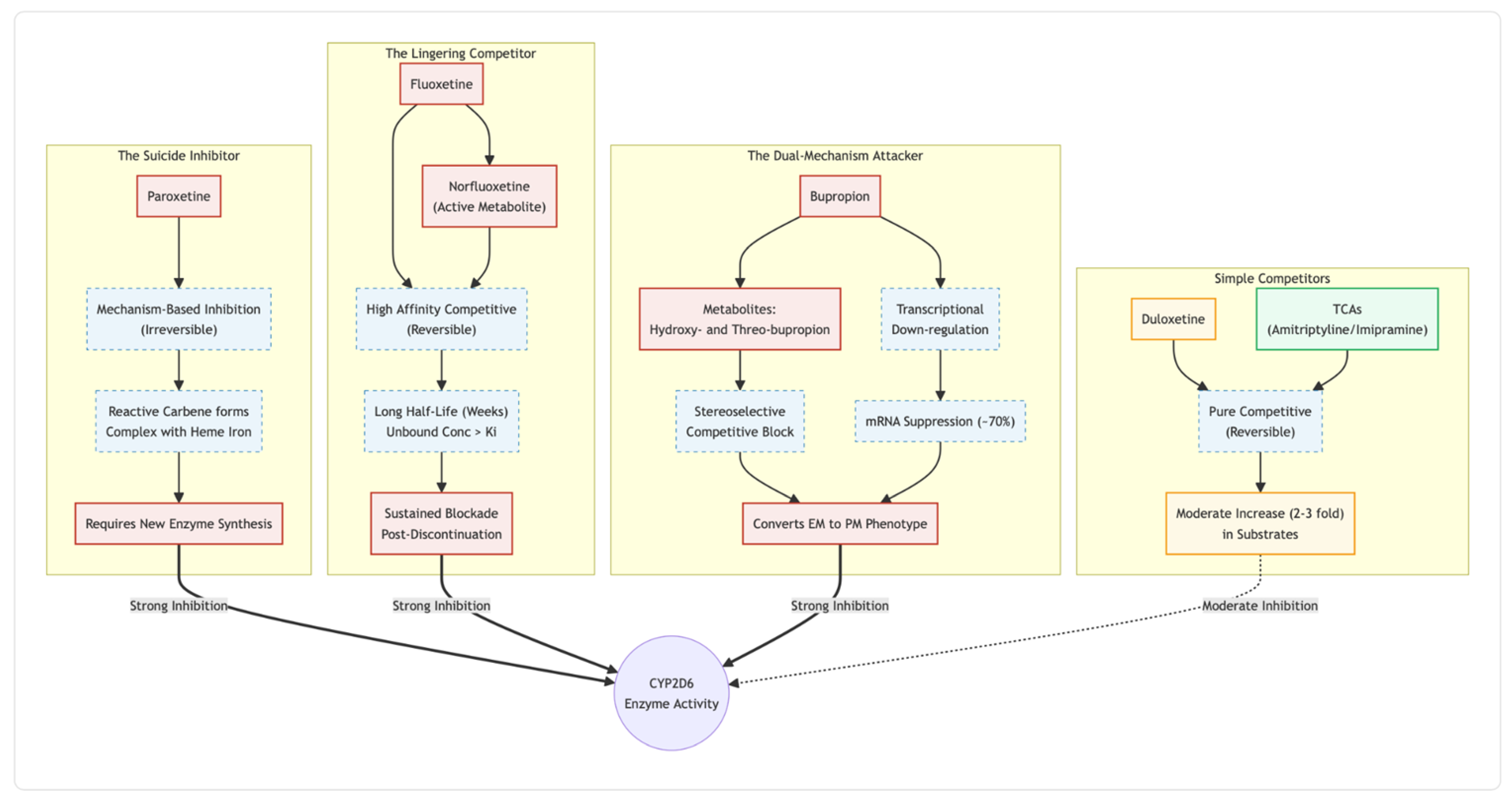

This review contrasts the main inhibitory options. Paroxetine’s suicide inhibition and fluoxetine’s weeks-long metabolite tail make both powerful but hard to govern. Bupropion, in contrast, delivers strong hepatic blockade while sparing the P-glycoprotein gate at the blood–brain barrier. Duloxetine offers a middle path: reversible, short-lived competition that fades within a day. Low-dose tricyclics supply the gentlest, most predictable brake—useful when manic switch risk or antipsychotic co-therapy narrows the safety margin. Drawing on enzyme kinetics, transporter data and bedside experience, we outline stepwise titration and timing tactics aimed at maximising antidepressant speed while steering clear of serotonin syndrome, agitation and drug-drug interactions. Thoughtful inhibitor selection and conservative, symptom-led dose adjustments appear central to translating this inexpensive oral stack into a reliable, broadly accessible alternative to ketamine infusions.

Background of the Novel Glutamatergic Stack

In recent years clinicians have started to look past the familiar monoamine-based antidepressants and toward treatments that act directly on glutamatergic signalling and synaptic plasticity. Intravenous ketamine has already proved that rapidly shifting cortical networks from an “NMDA-dominant” to an “AMPA-dominant” mode can lift even entrenched mood and anxiety disorders. Yet ketamine’s cost, the need for monitored infusions, and bothersome dissociative effects make it hard to roll out on a large scale.

Ngo Cheung [

1] has therefore outlined a fully oral alternative—quickly nicknamed the “Cheung glutamatergic regimen.” The protocol combines four off-patent agents: (i) dextromethorphan (DXM) supplies the NMDA antagonism; (ii) a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor slows DXM metabolism and keeps active levels in the ketamine range; (iii) piracetam acts as a positive allosteric modulator at AMPA receptors, boosting the downstream glutamate burst; and (iv) L-glutamine tops up presynaptic glutamate stores, potentially preventing depletion or excitotoxic rebound. Because every component is inexpensive and orally bioavailable, the regimen could in theory “democratize” ketamine-class efficacy.

Early bedside experience is encouraging. Single-case and small-series reports describe brisk, sometimes dramatic responses in conditions that usually defy routine care. Examples include a teenager whose binge-eating stopped within days [

2]; another whose long-standing somatic symptom disorder resolved after stepwise addition of the four agents [

3]; and several patients with trauma-linked syndromes or refractory obsessive–compulsive symptoms who achieved meaningful, durable remission [

4,

5]. Even cognitive slowing in schizoaffective disorder appeared to lift under the same approach [

6]. Although these reports are uncontrolled, the speed, breadth, and persistence of benefit signal that the mechanism merits formal study.

A crucial practical question is which CYP2D6 inhibitor should serve as DXM’s “pharmacokinetic bodyguard.” Cheung’s original paper favoured high-affinity SSRIs such as fluoxetine or paroxetine [

1]. Those choices indeed prolong DXM exposure but at the price of stacking serotonergic effects onto a high-dose DXM backbone—raising the spectre of serotonin toxicity, QTc prolongation, and other burdens.

CYP2D6, P-gp and the Safety of Glutamatergic Regimen

Within the “Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen”—a stack that already includes dextromethorphan and one or more mood-stabilising agents—the choice of antidepressant can determine whether the regimen feels seamless or ends in a pharmacological pile-up. Much of that difference comes down to how each drug treats two gate-keepers of central-nervous-system exposure: cytochrome P450 2D6 in the liver and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) at the blood–brain barrier.

Paroxetine sits at the top of the risk ladder. After only a few doses it converts itself to a carbene that binds permanently to the haem iron of CYP2D6, a classic “suicide” reaction [

7]. Because new enzyme must be synthesised before normal clearance returns, co-administered substrates can spike five-fold or more for days—an effect documented with viloxazine and several tricyclics [

8]. Inside a glutamatergic stack that already drives serotonin and glutamate, that surge can tip the patient into serotonin toxicity or manic agitation.

Fluoxetine is almost as disruptive, but for a different reason. Both the parent drug and its active metabolite norfluoxetine cling tightly yet reversibly to the CYP2D6 active site; what makes them troublesome is their longevity. Norfluoxetine’s half-life stretches past two weeks [

9], so patients remain functionally “poor metabolisers” long after tablets stop. Case reports and kinetic studies show that the phenotype can persist for a month, particularly in CYP2D6 poor-metaboliser genotypes where S-norfluoxetine accumulates [

10].

Bupropion adds another layer. Its hydroxy-metabolites are competitive CYP2D6 inhibitors, and chronic dosing turns down CYP2D6 gene expression, producing a five-fold rise in atomoxetine exposure [

11,

12]. Yet bupropion barely interacts with P-gp, whereas sertraline and desmethylsertraline are avid P-gp substrates [

13]. The result is a drug that powerfully alters hepatic clearance but does not crowd the transporter that controls brain entry—potentially useful if the aim is to raise cortical norepinephrine without further squeezing the BBB.

Duloxetine looks tame by comparison. It is a moderate, fully reversible CYP2D6 inhibitor; typical studies show a two- to three-fold rise in desipramine exposure and a quick return to baseline once duloxetine is stopped [

14,

15]. Because it neither forms a reactive metabolite nor suppresses enzyme synthesis, metabolic capacity can rebound within days, making dose adjustments straightforward if akathisia or blood-level creep appears.

Taken together, these data argue for a graded hierarchy of metabolic liability when building a Cheung-style polypharmacy: paroxetine as the clear outlier for irreversible blockade, fluoxetine for prolonged competitive inhibition, bupropion for potent but transporter-sparing phenoconversion, and duloxetine as the comparatively forgiving choice. Matching that hierarchy to a patient’s existing mood stabilisers and risk factors may spell the difference between rapid relief and a destabilising storm of drug–drug interactions.

Anecdotal Dosing Guidelines for the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen

People who layer dextromethorphan (DXM) with an SSRI in the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen learn quickly that “standard” antidepressant doses are anything but standard here. A full 20-milligram capsule of fluoxetine or paroxetine, harmless enough in routine depression care, slams the brakes on CYP2D6 so hard that DXM hangs around far longer than expected. Blood-levels climb, serotonin surges and, within a few days or 1-2 weeks, the patient may start to tremble, sweat and pace the room in a fog of early serotonin toxicity. For that reason many prescribers treat 20 mg as a red line, beginning instead with a sliver of a tablet—just enough to clip the enzyme without flooding the system.

Even the most careful titration can misfire. When overstimulation shows up, the unwritten rule is a three-day holiday from the SSRI. In practical terms it means stopping the inhibitor, waiting until the shakiness and sweating settle, then returning at half the previous dose. Paroxetine, with its short half-life, rarely needs more than those three days for CYP2D6 activity to rebound; fluoxetine lingers, yet a brief pause still lets plasma peaks fall far enough to calm the storm.

Frustrated patients sometimes assume the answer to a dull response is more antidepressant. In this protocol that logic backfires. Once CYP2D6 is thoroughly blocked, piling on extra SSRI is like pressing harder on a brake that’s already to the floorboards; the car doesn’t go faster—you only overheat the pads. If the stack feels underpowered, the fix is to feed the engine, not the brakes: inch up the DXM, add a little piracetam, bump glutamine. Those agents drive the glutamatergic and sigma-1 effects the regimen is built around, while the SSRI’s job remains what it was on day one—quietly keeping the metabolic door shut.

Timing the Inhibitor: Crafting AM–PM Schedules for the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen

Choosing when to give each antidepressant in the “Cheung Glutamatergic Regime” is almost as important as choosing the drug itself. Because dextromethorphan (DXM) is taken at night to minimise daytime dissociation and sedation, the CYP2D6 inhibitor has to keep the enzyme quiet until that evening dose arrives. How long the inhibition lasts—and whether the drug is calming or activating—drives the clock.

Paroxetine is the easiest to schedule. Once the molecule has formed its reactive carbene, it welds itself to the CYP2D6 haem iron and the enzyme is gone until the liver builds fresh protein [

7]. That round-the-clock blockade means the tablet can sit wherever the patient prefers. If paroxetine makes someone drowsy, they swallow it with the bedtime DXM; if it causes restlessness, they move it to breakfast without losing any metabolic punch.

Fluoxetine behaves differently but ends up offering similar freedom. Parent drug and norfluoxetine cling competitively to CYP2D6, yet their combined half-lives stretch into weeks, so enzyme occupancy hardly fluctuates over 24 hours [

9]. Because the compound is mildly stimulating, most people feel better taking it after they wake up; by the time night falls, plenty of inhibitor is still on board to protect DXM.

Bupropion, another morning-friendly option, suppresses the enzyme on two fronts. Hydroxy- and hydrobupropion compete at the active site, while longer-term dosing turns down CYP2D6 gene transcription [

12]. Clinical work shows that combination can push atomoxetine exposure five-fold even when bupropion is taken once a day at sunrise [

11]. The drug’s lack of affinity for P-glycoprotein [

13] also means it won’t crowd the transporter that governs DXM’s brain entry.

Duloxetine is the awkward cousin. Its CYP2D6 block is moderate and completely reversible, tracking its 12-hour plasma curve [

16]. A morning dose fits the drug’s energising profile, yet by evening the inhibition has already begun to fade, which can let more DXM slip through to dextrorphan. Patients who tolerate a late-afternoon capsule may regain some coverage, but duloxetine still offers the least reliable metabolic shield in a split AM/PM schedule.

Put simply, permanent or very prolonged inhibitors—paroxetine first, fluoxetine close behind, and transcription-suppressing bupropion—mesh smoothly with a nightly DXM pulse. Duloxetine can work, but only if clinicians accept a little pharmacokinetic wiggle room and watch for drifting DXM levels.

Tricyclics Inside the Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen

“Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen”—dextromethorphan paired with a CYP2D6 inhibitor to mimic ketamine’s antidepressant punch—works beautifully on paper, yet in real clinics it often lands on patients who already juggle mood stabilisers, antipsychotics, or both. For those vulnerable to manic swings, adding another strong CYP2D6 blocker such as bupropion, fluoxetine, or paroxetine can tip the balance from help to harm. In this setting the old-fashioned tricyclics—amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine—deserve a second look.

Unlike the modern boosters, TCAs behave like courteous house-guests in the liver. They bind to CYP2D6 only weakly and only while they remain in circulation; once the plasma level falls, the enzyme is free again [

17]. Bupropion, by contrast, silences the gene and clogs the active site simultaneously [

12]. Paroxetine forms an irreversible “suicide” complex with the heme iron [

7], and fluoxetine’s metabolite sticks around for weeks, prolonging inhibition long after the capsule is stopped [

9]. These hard stops can raise risperidone or aripiprazole exposures several-fold [

18], provoking akathisia, dysphoria, and ultimately non-adherence—the perfect storm for a manic break.

Because TCA-mediated inhibition is mild and fully reversible, serum concentrations of the companion mood stabiliser stay where the prescriber expects them. Clinicians gain room to titrate dextromethorphan upward in the Cheung stack without guessing how much the antipsychotic level will climb tomorrow. Predictability also shortens wash-out periods; if the patient destabilises or develops anticholinergic side-effects, the TCA can be tapered and CYP2D6 function rebounds within a day or two.

Tricyclics are not benign—orthostatic hypotension, weight gain, and QTc prolongation still matter [

19]. Yet when the therapeutic target is rapid relief of refractory depression inside a multi-drug regimen, their metabolic modesty can outweigh those liabilities. In short, TCAs keep the glutamatergic door open while leaving the enzyme machinery that clears mood stabilisers largely untouched, making them a pragmatic, “clean” option for the Cheung glutamatergic regime.

Conclusions

The Cheung Glutamatergic Regimen may be the first real attempt to give everyday clinics some of the speed and depth of ketamine without an infusion pump in sight. Early field reports are hard to ignore: people who had cycled through every SSRI and mood stabiliser sometimes brighten within days once DXM, piracetam and a little glutamine are on board. Still, the recipe is far from fool-proof. The same trick that keeps dextromethorphan in the bloodstream—shutting down CYP2D6—can just as easily turn friend to foe, pushing serotonin or co-prescribed antipsychotics into the danger zone.

Experience now sketches a rough safety ladder. Paroxetine sits at the top, potent but volatile; fluoxetine follows close behind with its long metabolic tail. Bupropion is steadier, duloxetine steadier still, while low-dose tricyclics are the gentlest handbrake of all. Choosing the right rung depends on the patient’s genetics, their current drug list and their sensitivity to mood swings or serotonergic side-effects. Start low, watch closely, back off the inhibitor at the first hint of overstimulation, and let the glutamatergic “engine” carry the therapeutic load. Done that way, the regimen can be both powerful and polite. Randomised trials will tell us whether the promise holds under scrutiny, but until then, careful pharmacokinetic thinking offers clinicians a sensible map through this exciting new territory.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Cheung N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: Proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints.org. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. Case report: Rapid remission of adolescent binge-eating disorder after over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentations to bupropion. Preprints.org. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. OTC glutamatergic augmentation resolves adolescent refractory somatic symptoms. Preprints.org. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. Case series: Marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprints.org. 2025. [Preprint ID 186969].

- Cheung N. Oral glutamatergic augmentation for trauma-related disorders with fluoxetine-/bupropion-potentiated dextromethorphan ± piracetam: A four-patient case series. Preprints.org. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cheung N. An oral “ketamine-like” NMDA/AMPA modulation stack restores cognitive capacity in a young man with schizoaffective disorder—Case report. Preprints.org. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen KM, Venkatakrishnan K, Von Moltke LL, et al. Apparent mechanism-based inhibition of human CYP2D6 in vitro by paroxetine: Comparison with fluoxetine and quinidine. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2003;31(3):289-293.

- Wang Z, Kosheleff AR, Adeojo LW, et al. Impact of paroxetine, a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, on SPN-812 (viloxazine extended-release) pharmacokinetics in healthy adults. Clinical Pharmacology in Drug Development. 2021;10(11):1365-1374.

- Deodhar M, Rihani SBA, Darakjian L, et al. Assessing the mechanism of fluoxetine-mediated CYP2D6 inhibition. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(2):148.

- Fjordside L, Jeppesen U, Eap CB, et al. The stereoselective metabolism of fluoxetine in poor and extensive metabolisers of sparteine. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9(1):55-60.

- Todor I, Popa A, Neag M, et al. Evaluation of a potential metabolism-mediated drug-drug interaction between atomoxetine and bupropion in healthy volunteers. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2016;19(2):198-207.

- Sager JE, Tripathy S, Price LS, et al. In vitro to in vivo extrapolation of the complex drug-drug interaction of bupropion and its metabolites with CYP2D6: Simultaneous reversible inhibition and CYP2D6 down-regulation. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2017;123:85-96.

- Wang JS, Zhu HJ, Gibson BB, et al. Sertraline and its metabolite desmethylsertraline, but not bupropion or its three major metabolites, have high affinity for P-glycoprotein. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2008;31(2):231-234.

- Patroneva A, Connolly SM, Fatato P, et al. An assessment of drug-drug interactions: The effect of desvenlafaxine and duloxetine on the pharmacokinetics of the CYP2D6 probe desipramine in healthy subjects. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2008;36(12):2484-2491.

- Skinner MH, Kuan HY, Pan A, et al. Duloxetine is both an inhibitor and a substrate of cytochrome P450 2D6 in healthy volunteers. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2003;73(3):170-177.

- Chan CY, New LS, Ho HK, et al. Reversible time-dependent inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes by duloxetine and inertness of its thiophene ring towards bioactivation. Toxicology Letters. 2011;206(3):314-324.

- Polasek TM, Miners JO. Time-dependent inhibition of human drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450 by tricyclic antidepressants. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2008;65(1):87-97.

- Cicali EJ, Smith DM, Duong BQ, et al. A scoping review of the evidence behind cytochrome P450 2D6 isoenzyme inhibitor classifications. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2020;108(1):116-125.

- Gillman PK. Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;151(6):737-748.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).