Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Participants

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | Cystic Fibrosis |

| pwCF | Patients with Cystic Fibrosis |

| F508del | F508del mutant CFTR |

| AE | Adverse event |

| ETI | Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor |

| SOC | System Organ Class |

References

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. [CrossRef]

- Ratjen F, Bell SC, Rowe SM, Goss CH, Quittner AL, Bush A. Cystic fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15010. [CrossRef]

- Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, González J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, Joubran J, Knapp T, Makings LR, Miller M, Neuberger T, Olson E, Panchenko V, Rader J, Singh A, Stack JH, Tung R, Grootenhuis PD, Negulescu P. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006 Jun;290(6):L1117-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor-Cousar JL, Robinson PD, Shteinberg M, Downey DG. CFTR modulator therapy: transforming the landscape of clinical care in cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2023 Sep 30;402(10408):1171-1184. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijerman HGM, McKone EF, Downey DG, et al. Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regiment in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:1940–8.

- Keating D, Marigowda G, Burr L, et al. VX-445-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis and one or two Phe508del alleles. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1612–20.

- Middleton PG, Mall MA, Drevinek P, et al. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1809–19.

- Goralski JL, Hoppe JE, Mall MA, McColley SA, McKone E, Ramsey B, Rayment JH, Robinson P, Stehling F, Taylor-Cousar JL, Tullis E, Ahluwalia N, Chin A, Chu C, Lu M, Niu T, Weinstock T, Ratjen F, Rosenfeld M. Phase 3 Open-Label Clinical Trial of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Children Aged 2-5 Years with Cystic Fibrosis and at Least One F508del Allele. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 Jul 1;208(1):59-67. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McNally P, Lester K, Stone G, Elnazir B, Williamson M, Cox D, Linnane B, Kirwan L, Rea D, O'Regan P, Semple T, Saunders C, Tiddens HAWM, McKone E, Davies JC; RECOVER Study Group. Improvement in Lung Clearance Index and Chest Computed Tomography Scores with Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor Treatment in People with Cystic Fibrosis Aged 12 Years and Older - The RECOVER Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023 Nov 1;208(9):917-929. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daines CL, Tullis E, Costa S, Linnemann RW, Mall MA, McKone EF, Polineni D, Quon BS, Ringshausen FC, Rowe SM, Selvadurai H, Taylor-Cousar JL, Withers NJ, Ahluwalia N, Moskowitz SM, Prieto-Centurion V, Tan YV, Tian S, Weinstock T, Xuan F, Zhang Y, Ramsey B, Griese M; VX17-445-105 Study Group. Long-term safety and efficacy of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis and at least one F508del allele: 144-week interim results from a 192-week open-label extension study. Eur Respir J. 2023 Dec 7;62(6):2202029. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bower JK, Volkova N, Ahluwalia N, Sahota G, Xuan F, Chin A, Weinstock TG, Ostrenga J, Elbert A. Real-world safety and effectiveness of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis: Interim results of a long-term registry-based study. J Cyst Fibros. 2023 Jul;22(4):730-737. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo S, Young DC, Safirstein J, Bourque B, Antell MH, Diloreto S, Rotolo SM. Mental status changes during Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor /Ivacaftor therapy. J Cyst Fibros 2021.

- Spoletini G, Gillgrass L, Pollard K, Shaw N, Williams E, Etherington C, Clifton IJ, Peckham DG. Dose adjustments of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in response to mental health side effects in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2022 Nov;21(6):1061-1065. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis L, Stander T, Mombourquette J, Richards CJ, Yonker LM, Lawton B, Hardcastle M, Zweifach J, Sicilian L, Bringhurst L, Neuringer IP. Heterogeneity in Reported Side Effects Following Initiation of Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor: Experiences at a Quaternary CF Care Center. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2025 Jan;60(1):e27382. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlizzi V, Fevola C, Presti S, Castaldo A, Daccò V, Claut L, Sepe A, Majo F, Casciaro R, Esposito I, Vitullo P, Salvi M, Troiani P, Ficili F, Parisi GF, Pantano S, Costa S, Leonetti G, Palladino N, Taccetti G, Bonomi P, Salvatore D. Reported Adverse Events in a Multicenter Cohort of Patients Ages 6-18 Years with Cystic Fibrosis and at Least One F508del Allele Receiving Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor. J Pediatr. 2024 Nov;274:114176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2024.114176. Epub 2024 Jun 28. Erratum in: J Pediatr. 2024 Nov;274:114228. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, Barjaktarevic IZ, Cooper BG, Hall GL, Hallstrand TS, Kaminsky DA, McCarthy K, McCormack MC, Oropez CE, Rosenfeld M, Stanojevic S, Swanney MP, Thompson BR. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Oct 15;200(8):e70-e88. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- What is a serious adverse event? FDA. 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/reporting-serious-problems-fda/what-serious-adverse-event. (Accessed March 24, 2025).

- Serious adverse reaction. European medicines agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/glossary-terms/serious-adverse-reaction (Accessed March 24, 2025).

- Bousquet C, Lagier G, Lillo-Le Louët A, Le Beller C, Venot A, Jaulent MC. Appraisal of the MedDRA conceptual structure for describing and grouping adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf. 2005;28(1):19-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf (accessed on April 14th 2025).

- Zhu C, Cui Z, Liu T, Lou S, Zhou L, Chen J, Zhao R, Wang L, Ou Y and Zou F (2025) Realworld safety profile of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ ivacaftor: a disproportionality analysis using the U.S. FDA adverse event reporting system. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1531514. [CrossRef]

- Mangoni, A. A. , and Jackson, S. H. (2004). Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57 (1), 6–14. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor J, Nazareth D, Wat D, Southern KW, Frost F. Regulatory adverse drug reaction analyses support a temporal increase in psychiatric reactions after initiation of cystic fibrosis combination modulator therapies. J Cyst Fibros. 2025 Jan;24(1):30-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey B, Correll CU, DeMaso DR, McKone E, Tullis E, Taylor-Cousar JL, Chu C, Volkova N, Ahluwalia N, Waltz D, Tian S, Mall MA. Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor Treatment and Depression-related Events. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024 Feb 1;209(3):299-306. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kolski-Andreaco A, Taiclet S, Myerburg MM, Sembrat J, Bridges RJ, Straub AC, Wills ZP, Butterworth MB, Devor DC. Potentiation of BKCa channels by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator correctors VX-445 and VX-121. J Clin Invest. 2024 Jul 2;134(16):e176328. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Southern KW, Addy C, Bell SC, Bevan A, Borawska U, Brown C, Burgel PR, Button B, Castellani C, Chansard A, Chilvers MA, Davies G, Davies JC, De Boeck K, Declercq D, Doumit M, Drevinek P, Fajac I, Gartner S, Georgiopoulos AM, Gursli S, Gramegna A, Hansen CM, Hug MJ, Lammertyn E, Landau EEC, Langley R, Mayer- Hamblett N, Middleton A, Middleton PG, Mielus M, Morrison L, Munck A, Plant B, Ploeger M, Bertrand DP, Pressler T, Quon BS, Radtke T, Saynor ZL, Shufer I, Smyth AR, Smith C, van Koningsbruggen-Rietschel S. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis; establishing and maintaining health. J Cyst Fibros 2024;23(1):12–28.

- Baromeo SBC, van der Meer R, van Rossen RCJM, Wilms EB. Adverse events to elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis due to elevated drug exposure?: A case series. J Cyst Fibros. 2025 Mar 10:S1569-1993(25)00061-X. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewkesbury DH, Athwal V, Bright-Thomas RJ, Jones AM, Barry PJ. Longitudinal effects of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on liver tests at a large single adult cystic fibrosis centre. J Cyst Fibros. 2023 Mar;22(2):256-262. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overall population (N=414) |

pwCF not presenting AE (N=329) |

pwCF presenting at least 1 AE (N=85) (21%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 329 | 85 | 0.4 | |

| Median (Min, Max) | 27 (2, 68) | 27 (2, 59) | 28 (5, 68) | |

| Mean (SD) | 28 (13) | 28 (13) | 29 (14) | |

| Age | 0.7 | |||

| Adult | 310 (75%) | 245 (79%) | 65 (21%) | |

| Ped | 104 (25%) | 84 (81%) | 20 (19%) | |

| Sex | 0.6 | |||

| F | 222 (54%) | 174 (78%) | 48 (22%) | |

| M | 192 (46%) | 155 (81%) | 37 (19%) | |

| Baseline ppFEV1 (N=401) | 401 | 320 | 81 | 0.2 |

| Median (Min, Max) | 77 (19, 121) | 77 (19, 121) | 75 (25, 118) | |

| Mean (SD) | 74 (22) | 75 (22) | 71 (22) | |

| Baseline ppFEV1 (N=401) | 0.082 | |||

| <40 | 31 (7.7%) | 21 (68%) | 10 (32%) | |

| >40 | 370 (92%) | 299 (81%) | 71 (19%) | |

| Genotype | 0.4 | |||

| F508del/other | 274 (66%) | 221 (81%) | 53 (19%) | |

| F508del/ F508del | 140 (34%) | 108 (77%) | 32 (23%) | |

| Cl at sweat test in mmol/L (N=405) | 405 | 320 | 85 | 0.5 |

| Median (Min, Max) | 96 (12, 188) | 96 (12, 188) | 92 (47, 156) | |

| Mean (SD) | 93 (21) | 93 (22) | 93 (19) |

| AE (n) | ETI treatment days (n) | AE/1000 days ETI | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part A | Entire period of observation | |||||||

| Total | 142 | 488889 | 0.290 | |||||

| Sex | M | 64 | 224985 | 0.284 | 0.9 | |||

| F | 78 | 263904 | 0.296 | |||||

| Genotype | F508del/F508del | 45 | 152652 | 0.295 | 0.9 | |||

| F508del/other | 97 | 336237 | 0.288 | |||||

| ppFEV1 | ppFEV1 <40 | 16 | 52932 | 0.302 | 0.8 | |||

| ppFEV1 ≥40 | 118 | 415512 | 0.284 | |||||

| Sweat test | Cl < median (95.5) | 76 | 232524 | 0.327 | 0.3 | |||

| Cl ≥ median (95.5) | 66 | 244858 | 0.270 | |||||

| Age | Age < 18 y | 30 | 93983 | 0.319 | 0.6 | |||

| Age ≥ 18 y | 112 | 394907 | 0.284 | |||||

| Part B | 0-30 days | |||||||

| Total | 62 | 14062 | 4.409 | |||||

| Sex | M | 24 | 6549 | 3.665 | 0.3 | |||

| F | 38 | 7513 | 5.058 | |||||

| Genotype | F508del/F508del | 19 | 4590 | 4.139 | 0.8 | |||

| F508del/other | 43 | 9472 | 4.540 | |||||

| ppFEV1 | ppFEV1 <40 | 11 | 1110 | 9.910 | 0.01 | |||

| ppFEV1 ≥40 | 49 | 12442 | 3.938 | |||||

| Sweat test | Cl < median (95.5) | 33 | 6772 | 4.873 | 0.5 | |||

| Cl ≥ median (95.5) | 29 | 7020 | 4.131 | |||||

| Age | Age < 18 y | 15 | 3363 | 4.460 | 1 | |||

| Age >= 18 y | 47 | 10699 | 4.393 | |||||

| SOC | AEs | |

| n | (%) | |

| Investigations | 24 | 16.90 |

| Liver function marker elevations | 22 | |

| Pancreatic enzyme elevation | 1 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1 | |

| Psychiatric disorders | 24 | 16.90 |

| Depression | 6 | |

| Anxiety | 3 | |

| Brain fog | 3 | |

| Insomnia | 3 | |

| Low mood | 3 | |

| Behavioral alterations | 3 | |

| Attention deficit | 2 | |

| Agitation | 1 | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 24 | 16.90 |

| Skin rash | 16 | |

| Itching | 3 | |

| Erythema | 2 | |

| Acne | 1 | |

| Mucosal dryness | 1 | |

| Desquamation of the palms | 1 | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 23 | 16.20 |

| Epigastric pain | 11 | |

| Diarrhea | 4 | |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | |

| Nausea | 2 | |

| Dyspeptic disorders | 2 | |

| Abdominal swelling | 1 | |

| Odontologic symptoms | 1 | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 13 | 9.15 |

| Myalgia | 6 | |

| Articular pain | 4 | |

| Muscle weakness | 2 | |

| Low back pain | 1 | |

| Nervous system disorders | 10 | 7.04 |

| Headache | 6 | |

| Drowsiness | 1 | |

| School difficulties | 1 | |

| Episodes of absence | 1 | |

| Tic | 1 | |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 9 | 6.34 |

| Asthenia | 4 | |

| Fever | 2 | |

| Generalized edema | 1 | |

| Hyperpyrexia | 1 | |

| Tiredness | 1 | |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 8 | 5.63 |

| Chest tightness | 3 | |

| Chest heaviness | 2 | |

| Blood in sputum | 2 | |

| Dysphonia | 1 | |

| Eye disorders | 4 | 2.82 |

| Dry eyes | 2 | |

| Decrease in visual acuity | 1 | |

| Eye swelling | 1 | |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 1 | 0.70 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 1 | 0.70 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 | 0.70 |

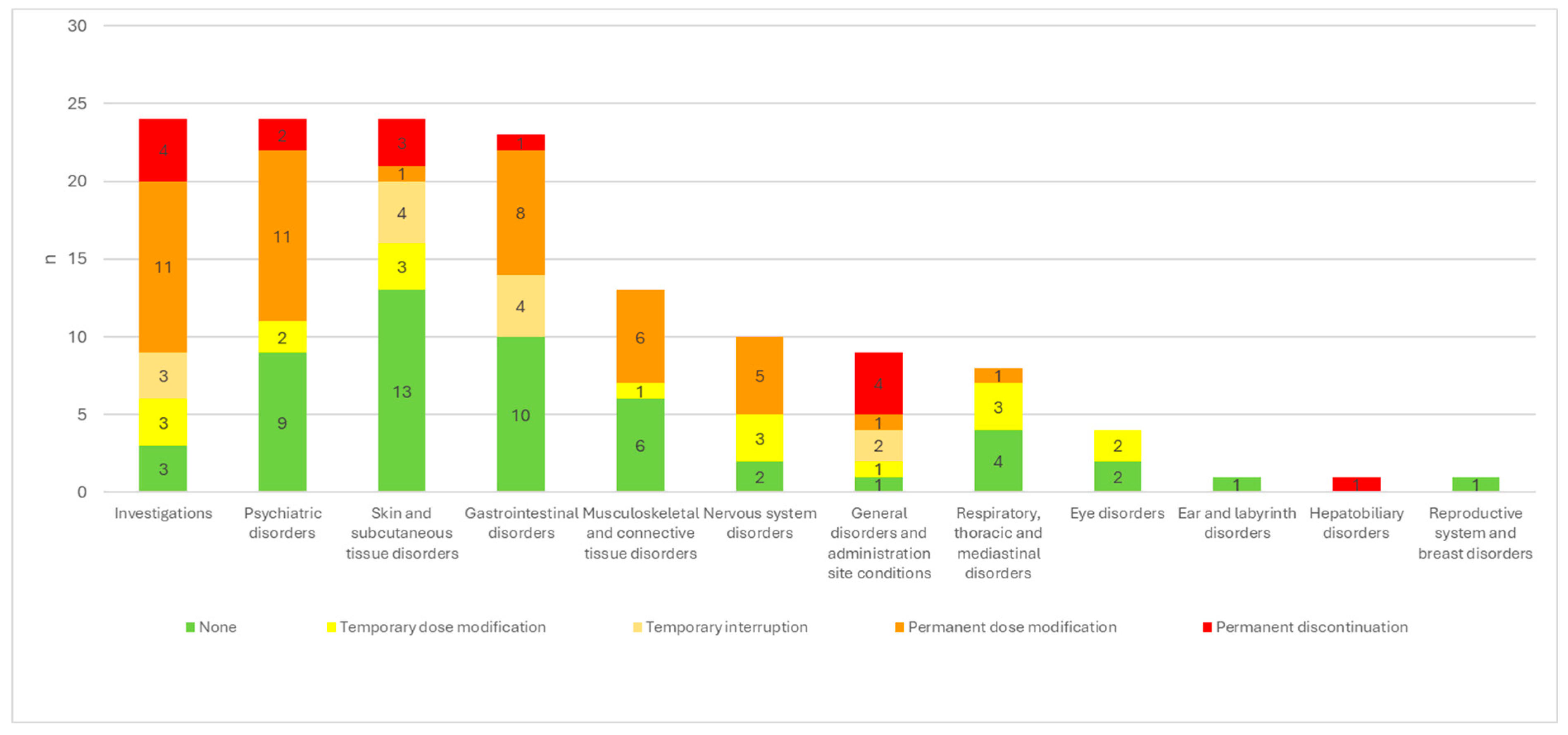

| None | Temporary dosage modification | Temporary interruption | Permanent dosage modification | Permanent discontinuation |

||

| Investigations | 24 | 3/24 (12.5%) | 3/24 (12.5%) | 3/24 (12.5%) | 11/24 (45.8%) | 4/24 (16.7%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 24 | 9/24 (37.5%) | 2/24 (8.3%) | 11/24 (45.8%) | 2/24 (8.3%) | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 24 | 13/24 (54.2%) | 3/24 (12.5%) | 4/24 (16.7%) | 1/24 (4.2%) | 3/24 (12.5%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 23 | 10/23 (43.5%) | 4/23 (17.4%) | 8/23 (34.8%) | 1/23 (4.3%) | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 13 | 6/13 (46.2%) | 1/13 (7.7%) | 6/13 (46.2%) | ||

| Nervous system disorders | 10 | 2/10 (20.0%) | 3/10 (30.0%) | 5/10 (50.0%) | ||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 9 | 1/9 (11.1%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | 4/9 (44.4%) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 8 | 4/8 (50.0%) | 3/8 (37.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) | ||

| Eye disorders | 4 | 2/4 (50.0%) | 2/4 (50.0%) | |||

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 1 | 1/1 | ||||

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 1 | 1/1 | ||||

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 1 | 1/1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).