Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

-

MOND (alternatively seen as a modified inertia or gravity modified theory) of Mordehai Milgrom [9,10]and

- -

- MOG (modified gravity) of John Moffat [11].

- -

- According to the approach of Verlinde [13], gravity is an emergent phenomenon, starting from a network of qubits which supposedly encode the Universe. Space-time and matter are then treated as a hologram. Dark energy, seen as a property of the network of qubits, interacts with matter to create the illusion of gravity.

- -

- In his approach, Maeder [14,15] wonders whether a part of the difference between the total gravitational mass and the baryonic mass could possibly be explained by exploiting the idea of scale invariance of the empty space.

- -

- A totally different way to eliminate dark matter has been also proposed by Gupta [16]. Unfortunately, the latter model exclusively concerns cosmological items, important questions such as flatness of the galaxy rotation profiles or the mass of galaxy clusters are not considered.

2. Some Observational Facts

- i.

-

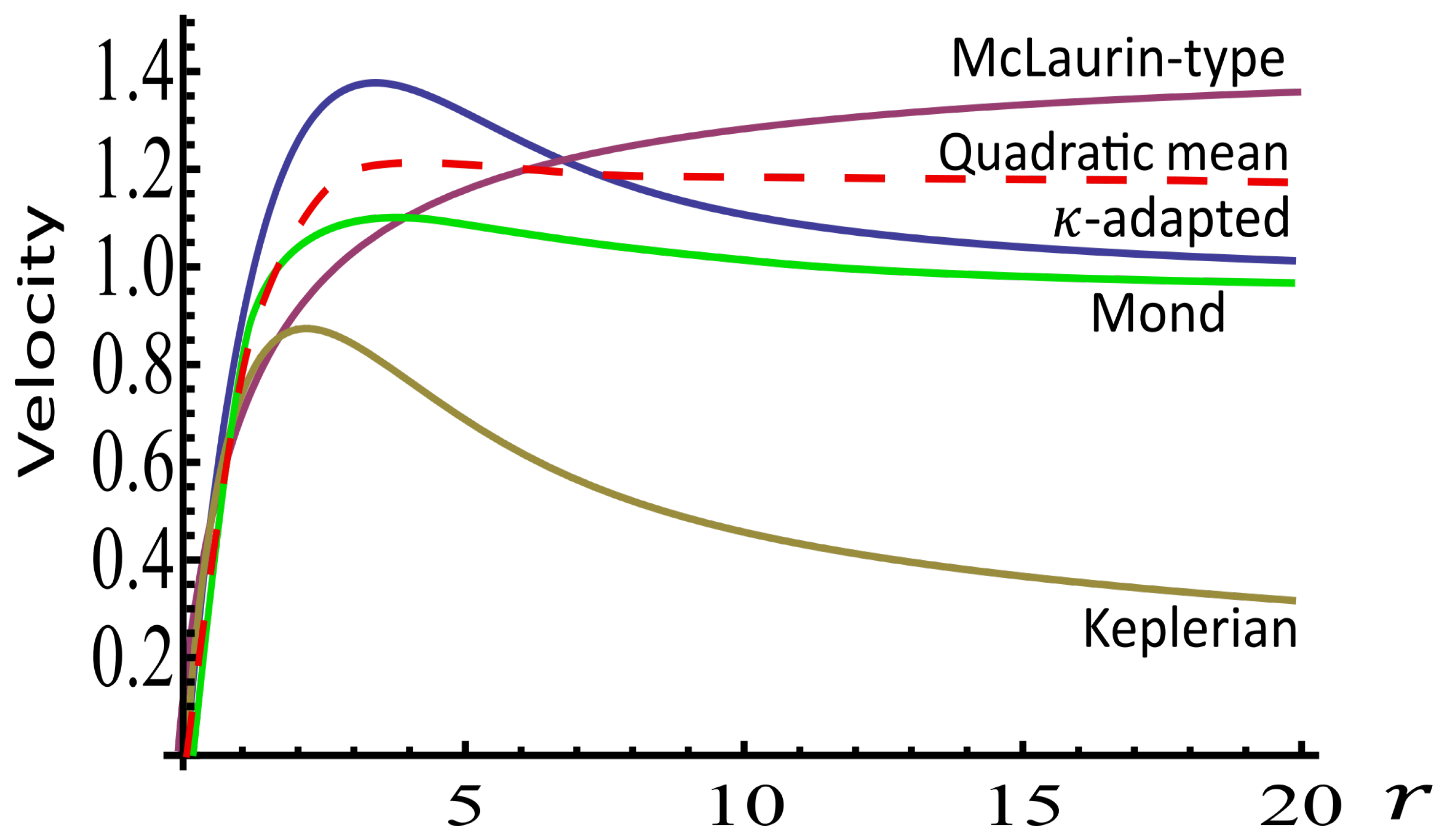

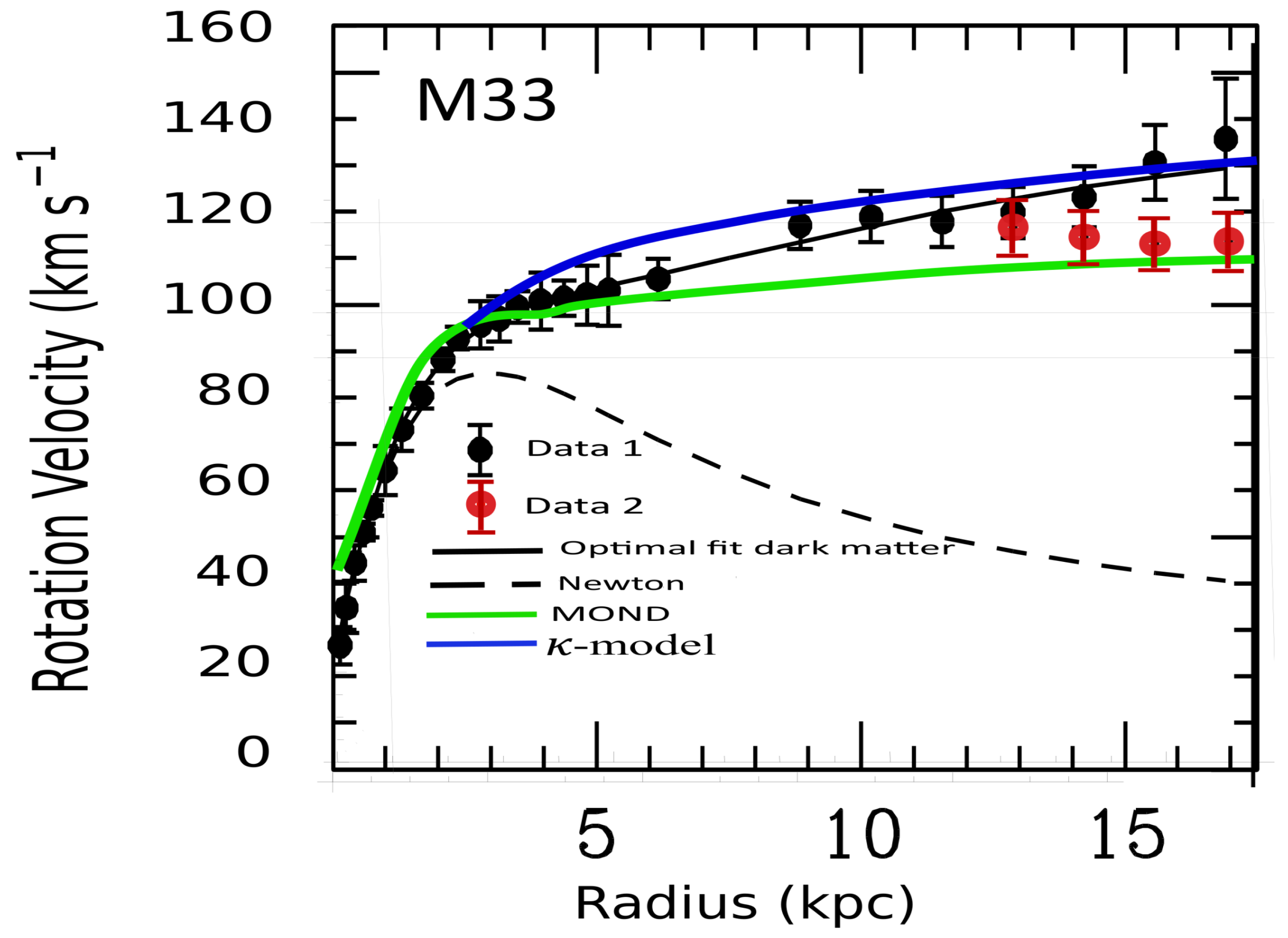

The galaxy rotation profiles :At a large distance from the centre, the rotation profile of a typical spiral galaxy does not decrease as predicted by the newtonian mechanics. The addition of a gigantic spherical halo of dark matter [23], or a modification of the inertia or of the gravity law solves the problem [9–11,24].

- ii.

-

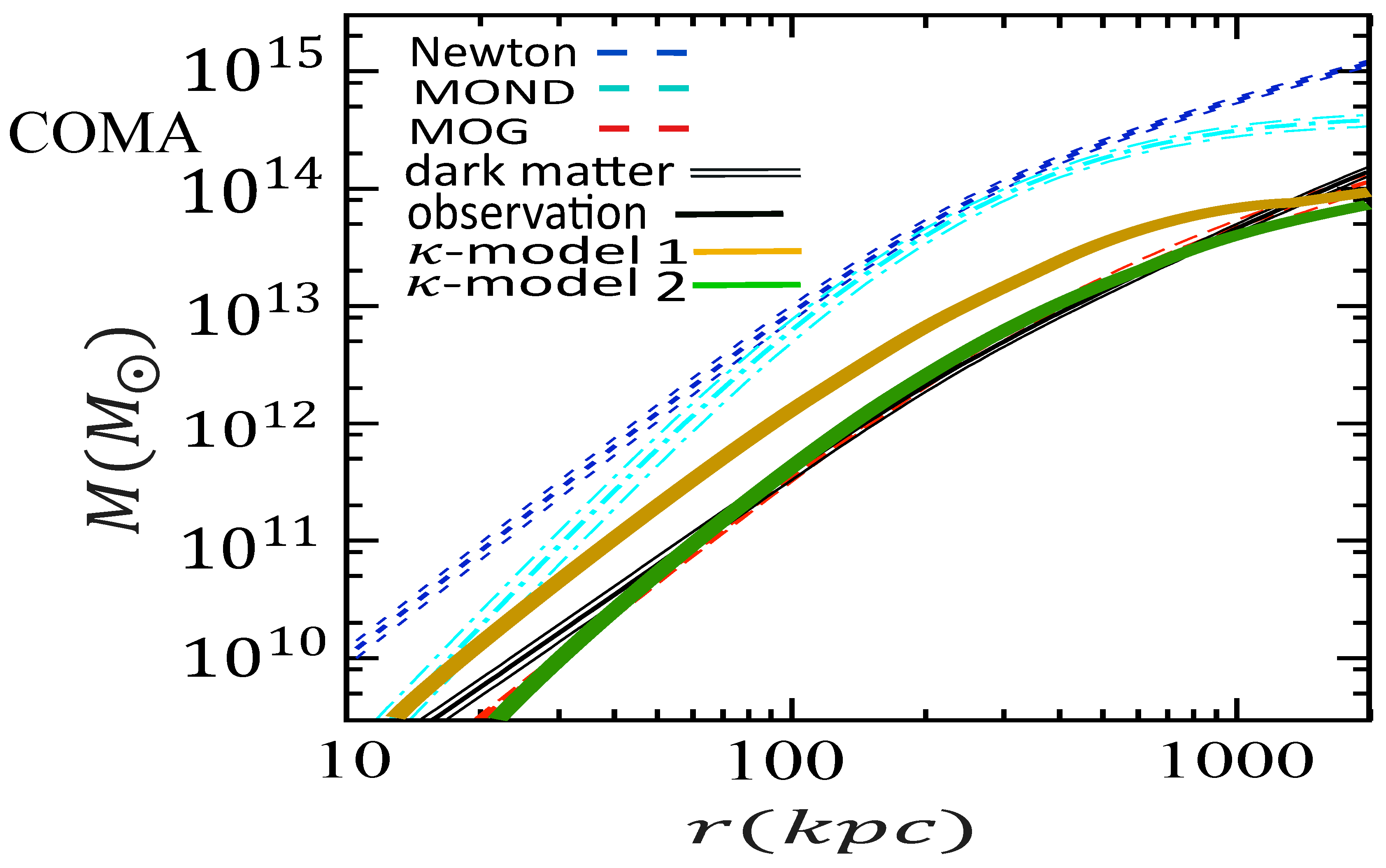

The mass of the galaxy clusters :The mass of galaxy clusters appears generally very high, of an order of about 10 times the visible baryonic mass. Once again, the addition of a halo of dark matter solves the problem, but an adequate modification of the gravity does the job too [25].

- iii.

-

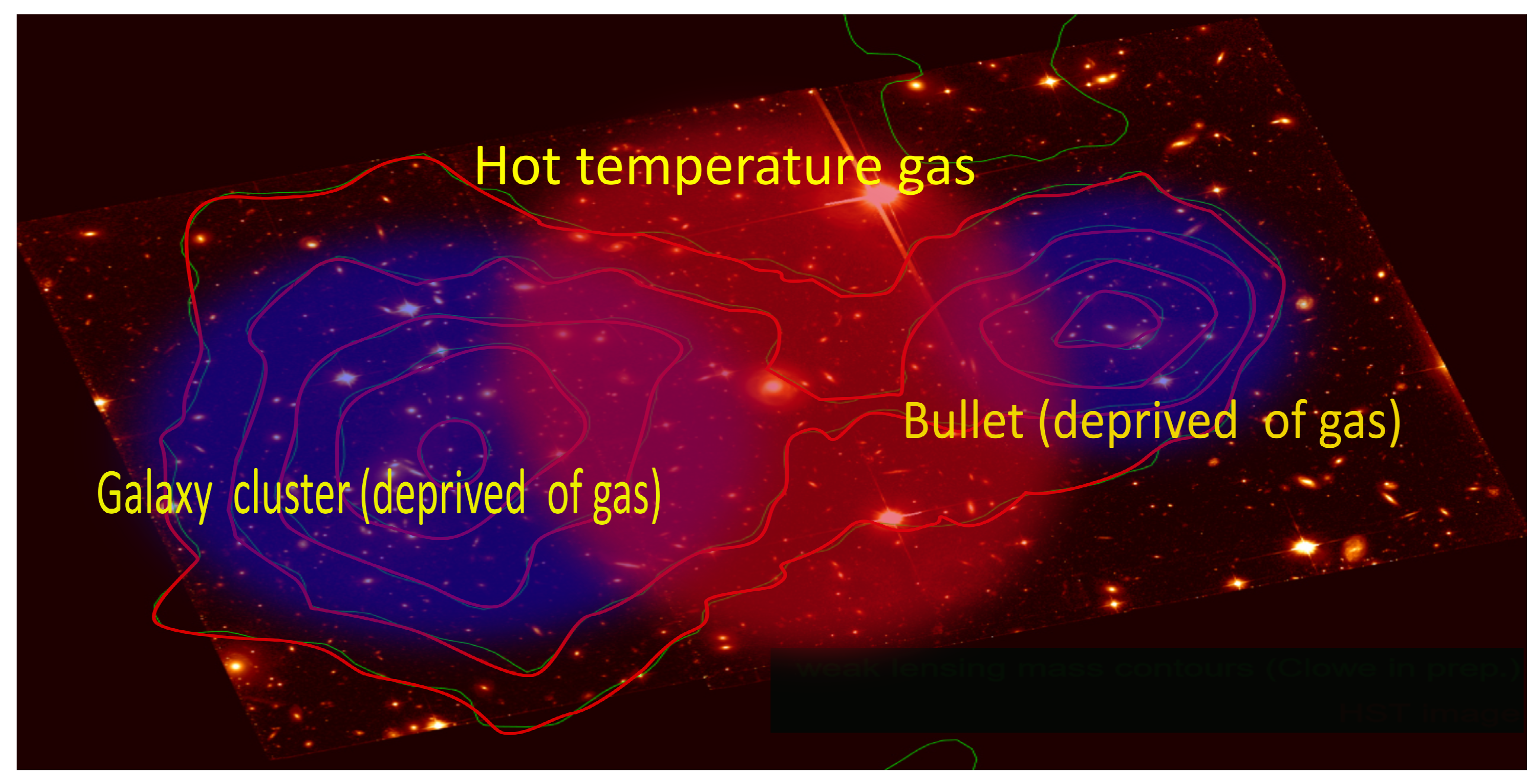

The Bullet cluster :The bullet cluster apparently represents a very rare situation, the lensing diagram is surprinsingly not centered on the baryonic mass (hot temperature gas). The dark matter once again successfully passes the test. By constrast this observation is uneasy to explain in the framework of MOND, whereas MOG manages to do it [26].

- iv.

-

The cosmic microwave background.At the present time : all these observational facts appear definitively understood in the framework of the dark matter paradigm, and not at all by other models, according to the peremptory assertions of dark matter supporters. How is that so certain? Eventually there is the so famous determining test of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies. However, it has to be said that both MOG [27] and relativistic MOND [28] easily pass also the latter test.

3. Mathematical Background

4. Applications

- (1)

-

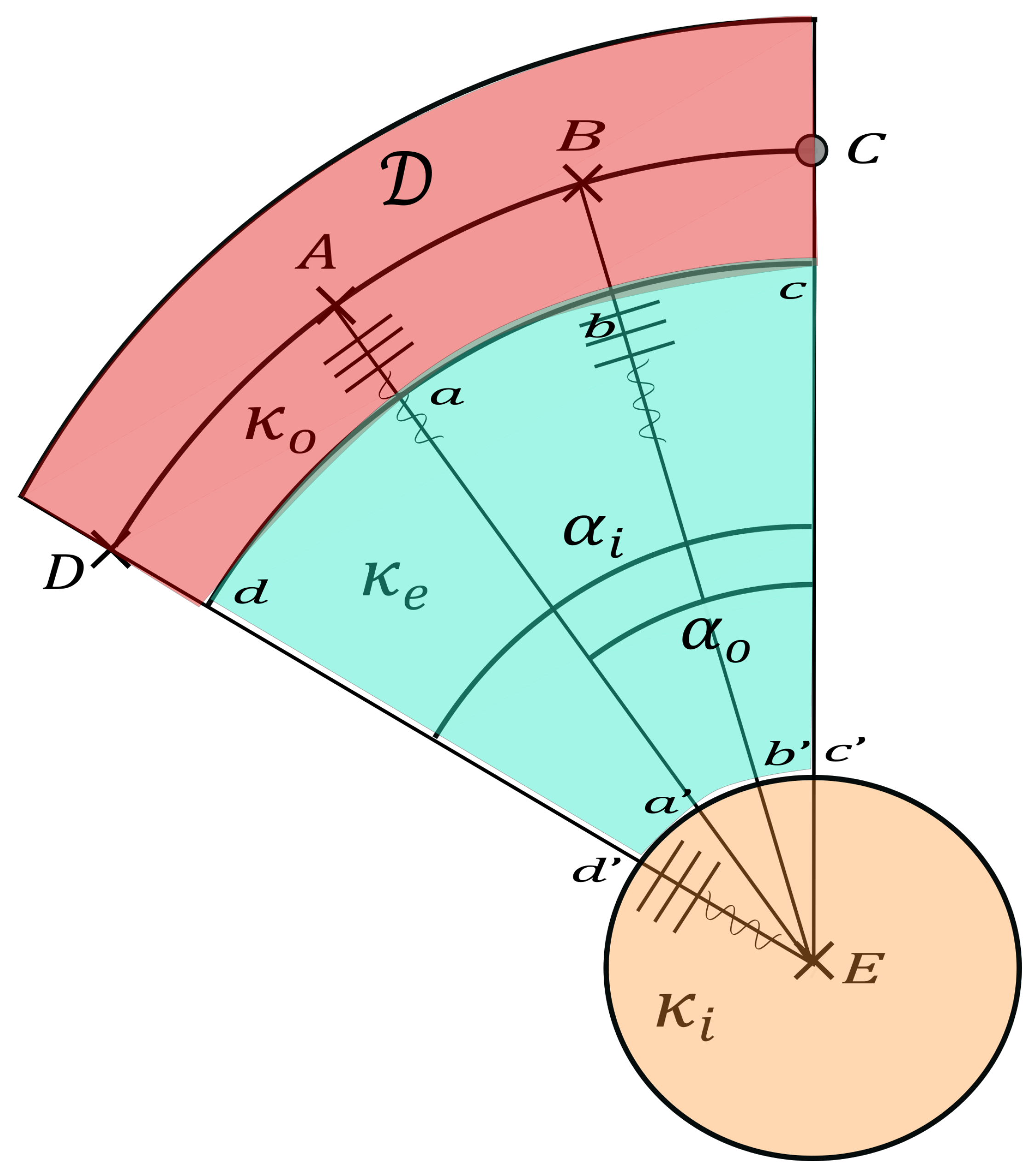

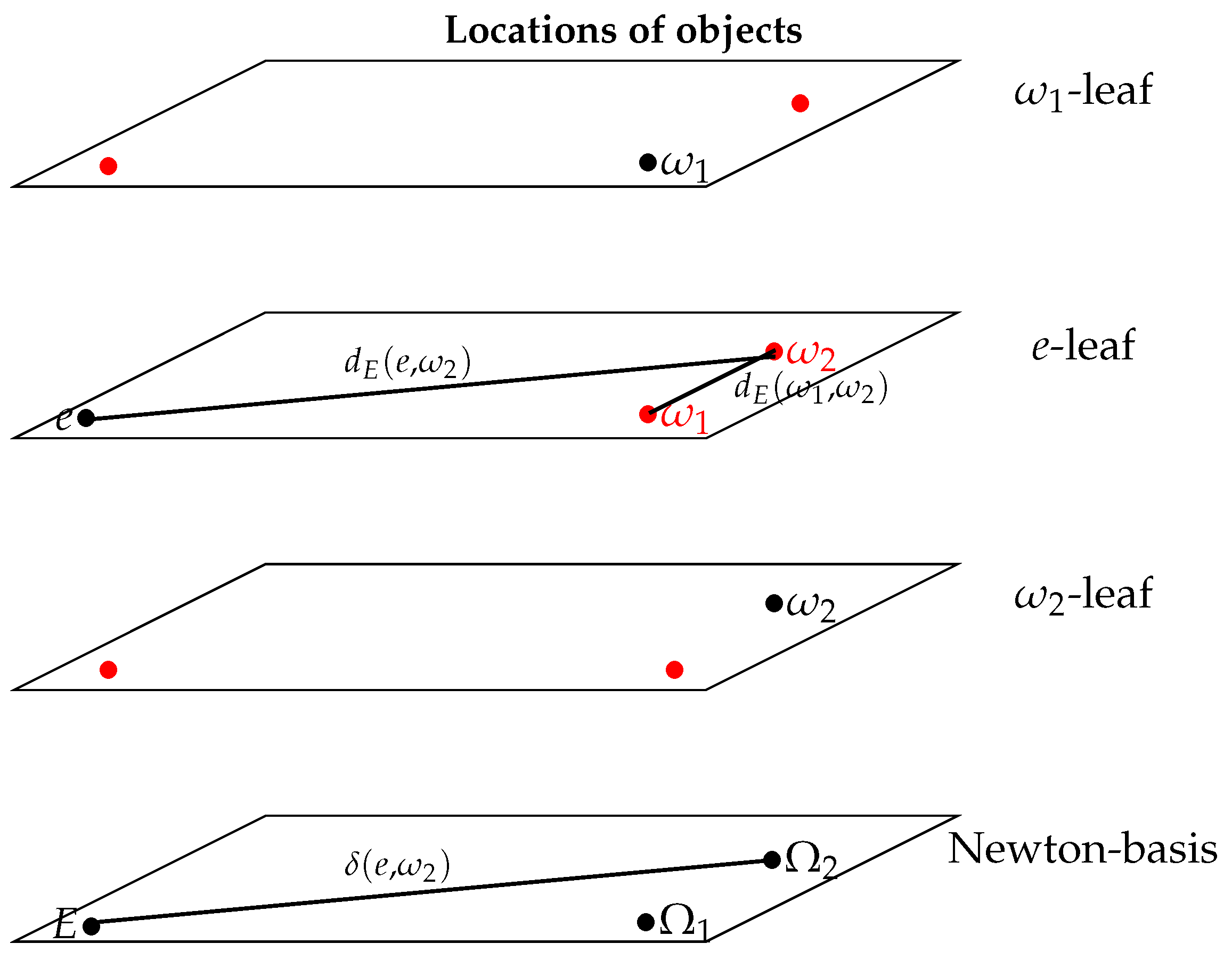

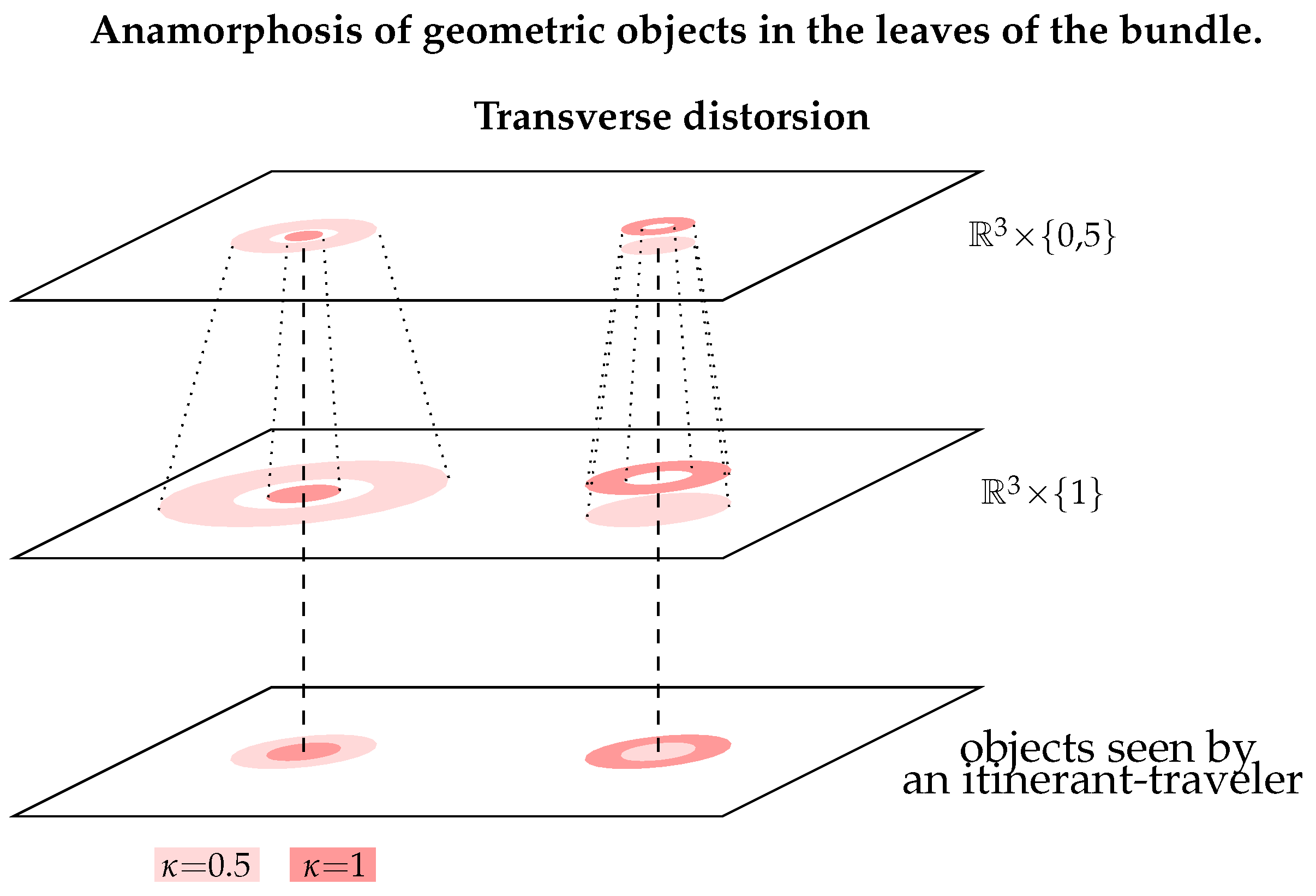

Each trivial cross-sections of the trivial bundleis equipped with the flat Riemannian metrics .For we call o-leaf the trivial cross-section equipped with the metric .

- (2)

- We also get a a priorinon-flat Riemannian metric on

4.1. Postulate of the Kappa-Model

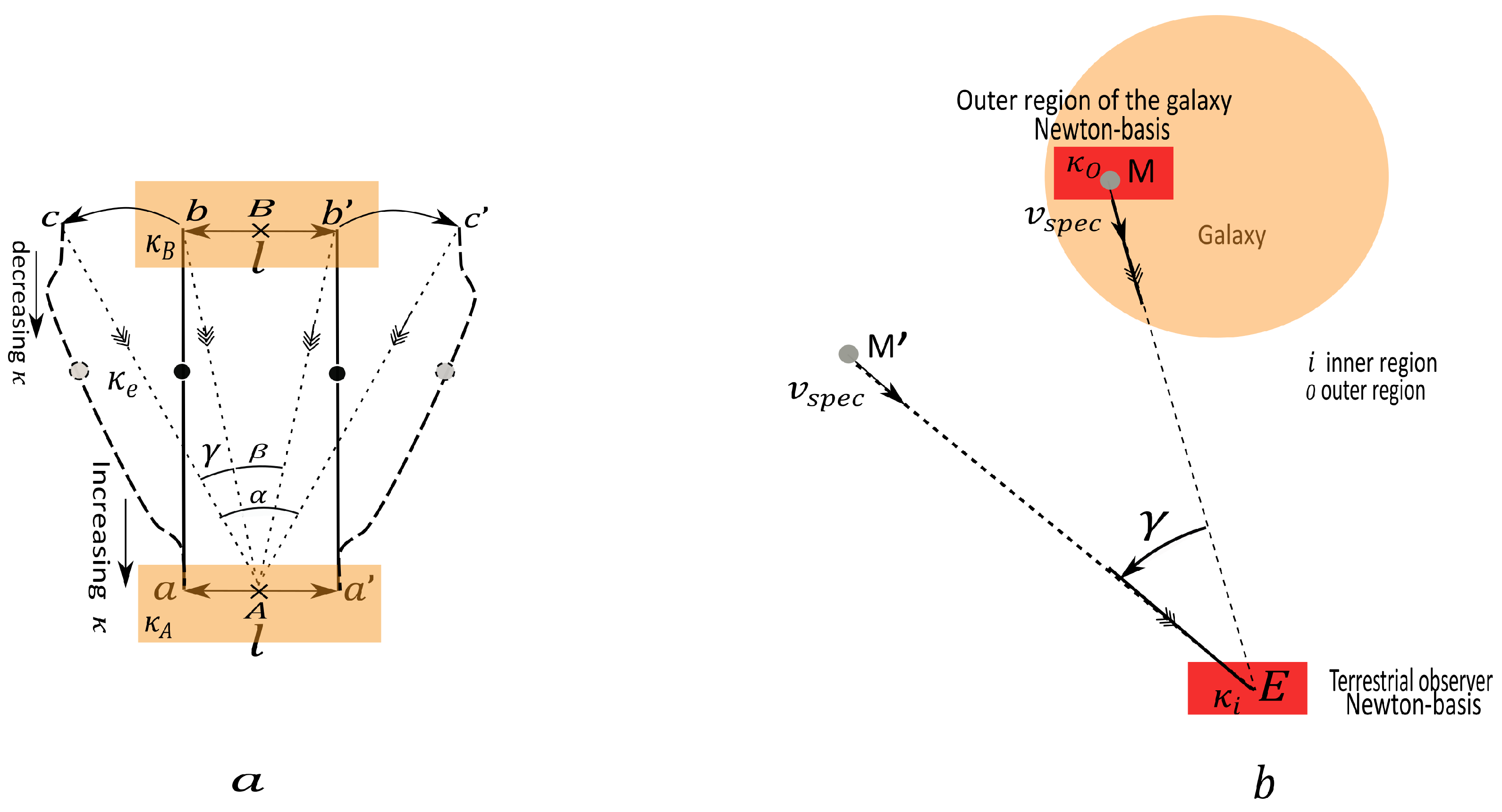

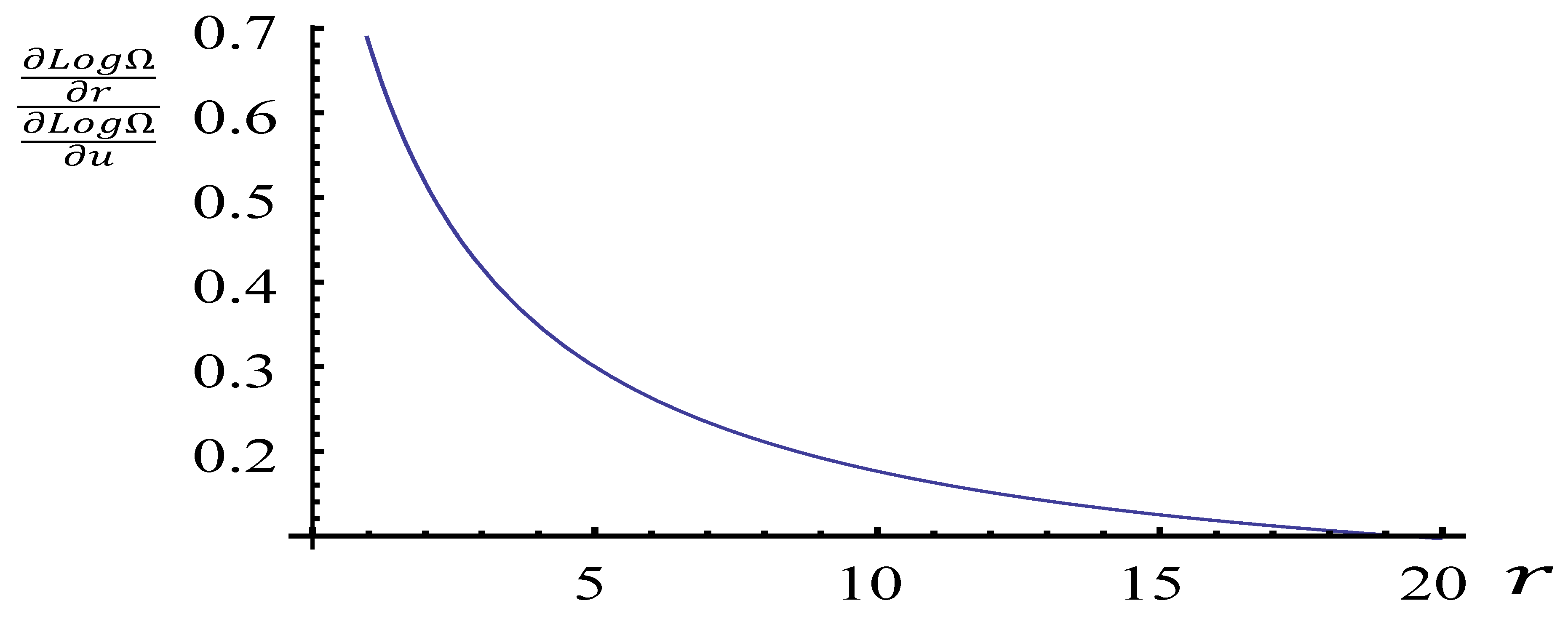

A -effect appears when a sitting-observer uses its local tools of measurement to measure distances between objects located in a region R where the rescaling coefficients is different from its own.

A -effect appears when a sitting-observer uses its local tools of measurement to measure distances between objects located in a region R where the rescaling coefficients is different from its own.4.1.1. Consequences of the Postulate on Metrology

- -

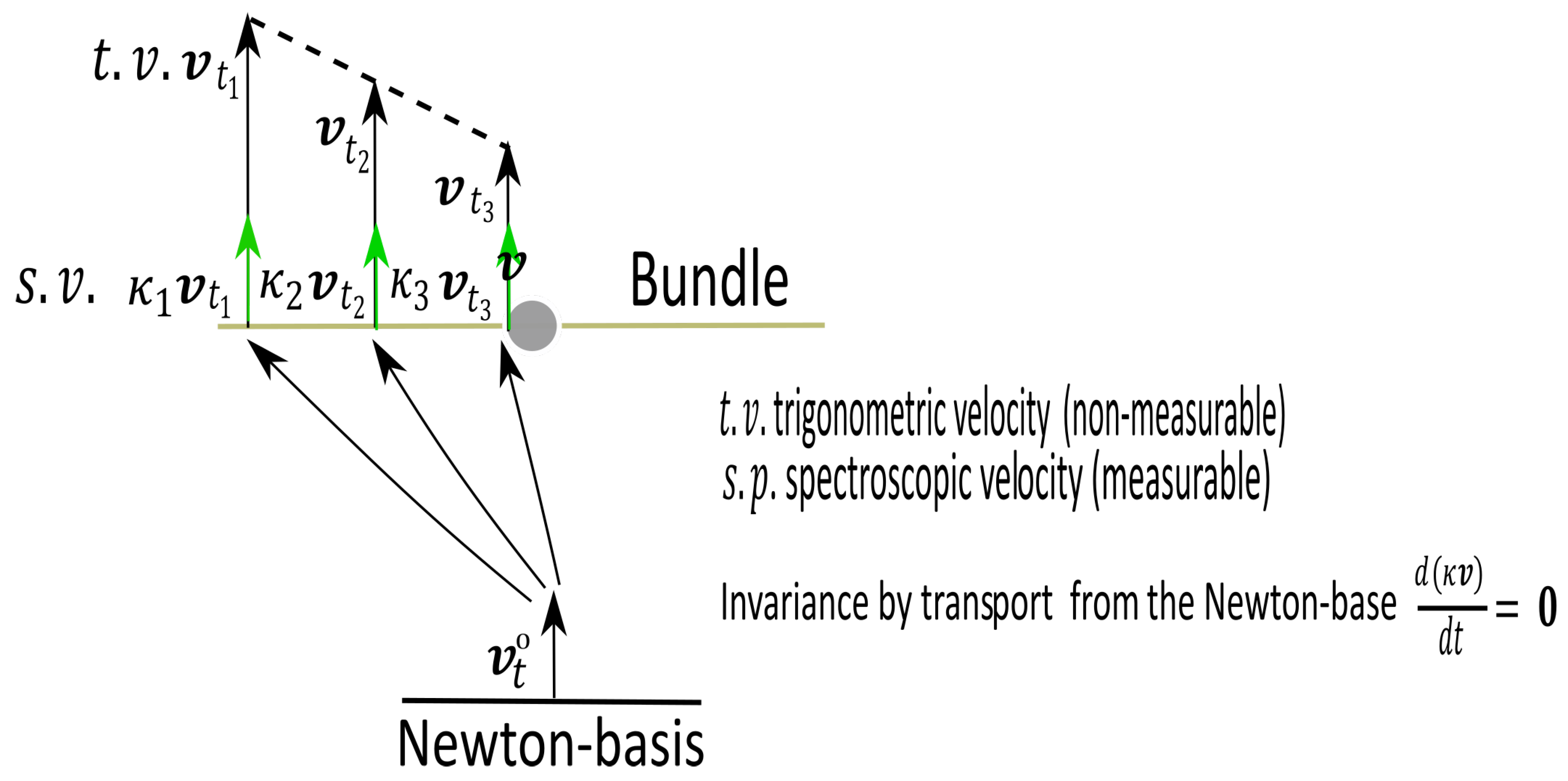

- For close objects (up to about 1 ), the sitting-observer E uses trigonometric parallax methods to estimate radial distances, in other words he uses its local tools and obtains . If and are close enough to e some trigonometry gives the distance i.e the distance in the e-leaf between the "replicas" of and seen by E.

- -

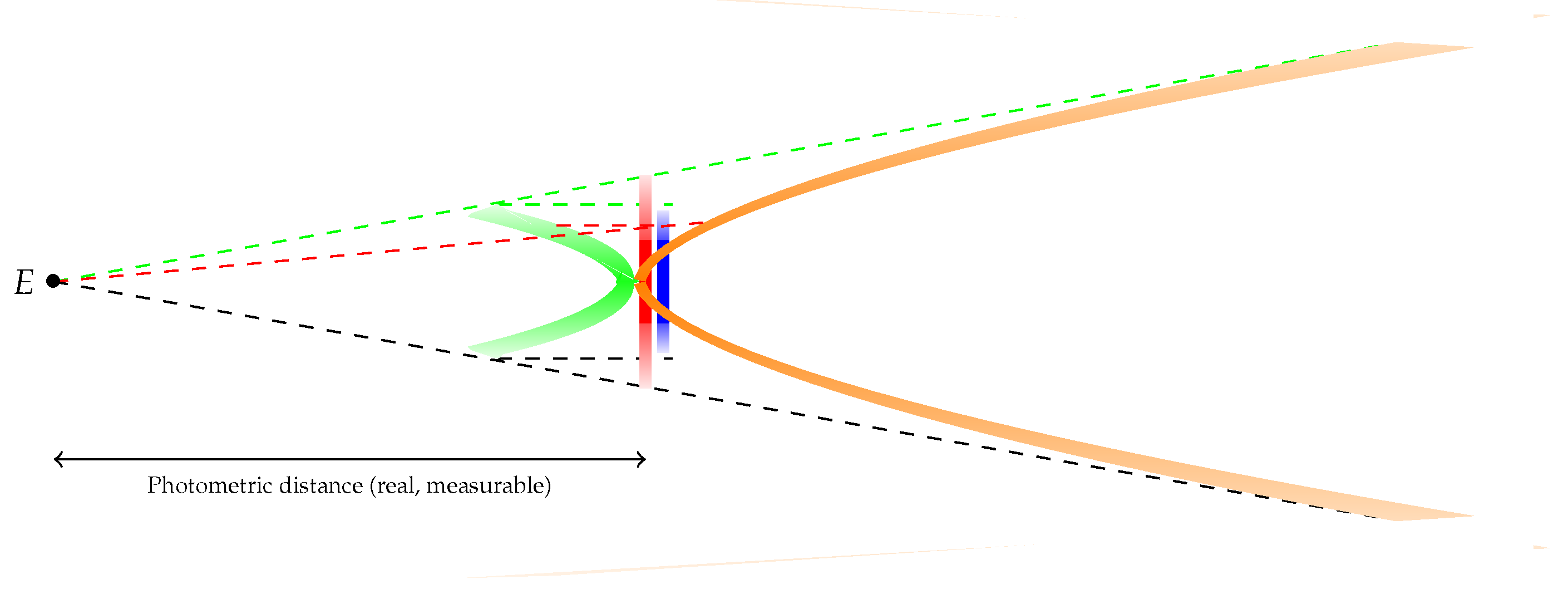

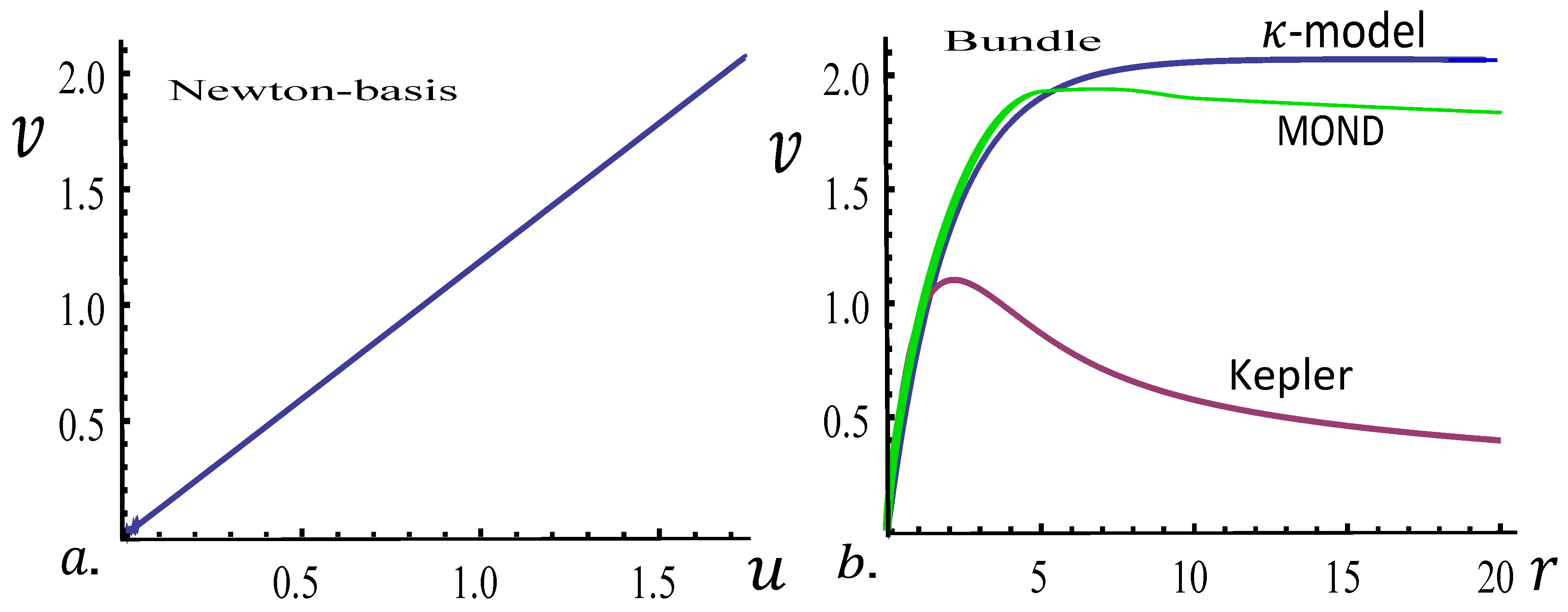

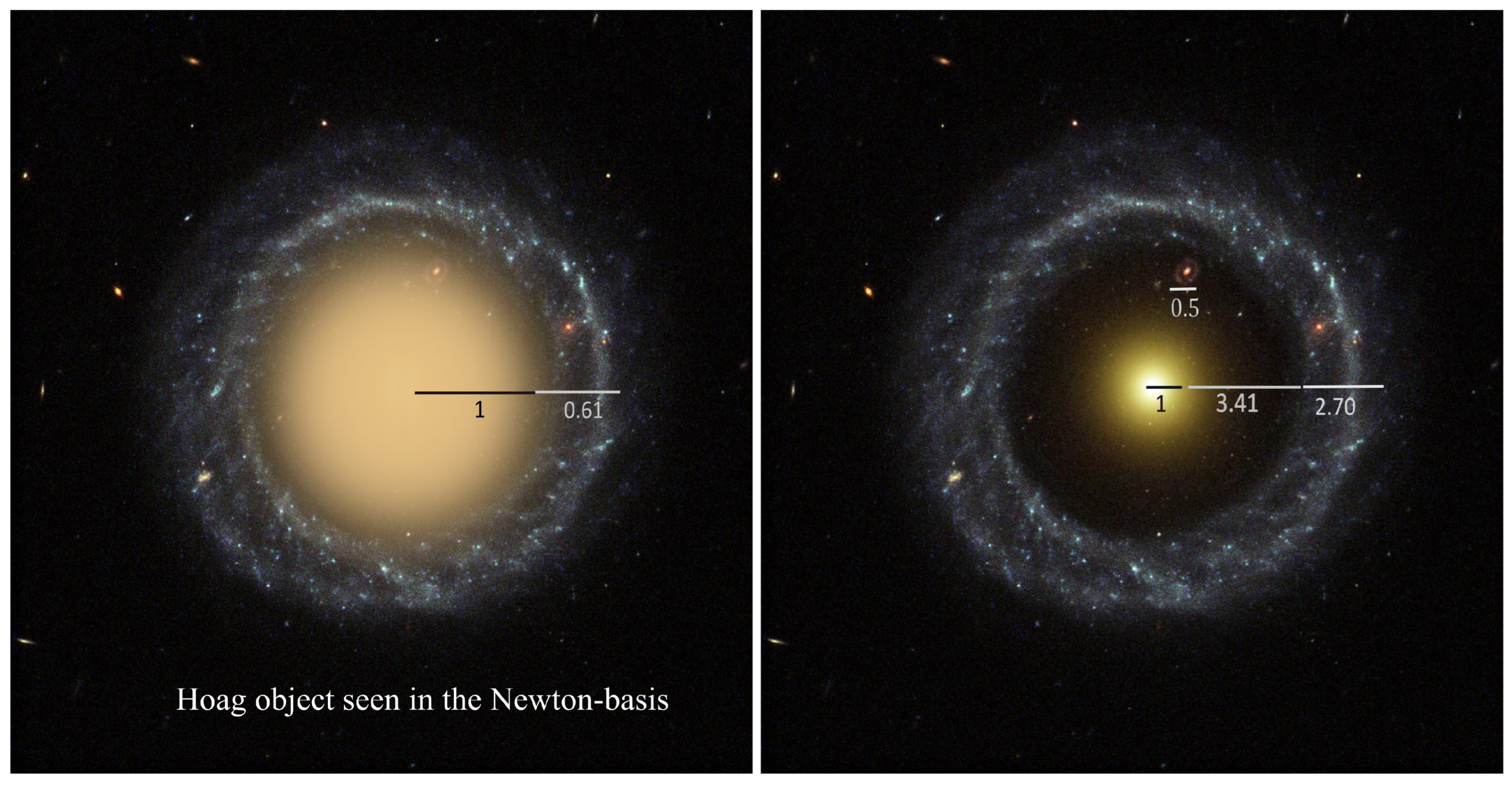

- When an object is located too far away to use parallax methods to evaluate its distance to earth, metric informations are retreived from informations carried by light such as ratios between intrinsic magnitude and observed magnitude (cepheid-method) ; furthermore the number of stars in a given region is not submitted to -effect. In other words the luminosity is not affected by the -effect. Distances measured by those kinds of methods are the distances that an itinerant-observer would get, we denote it and call it photometric distance, they are valid for close galaxies and are distances in the Newton-basis, cfFigure 1. To get an estimate of the distance between two distant objects and , the sitting-observer E has no choice but to use the -effect independant angle and the photometric distances and obtaining that way an "apparent" distance proportional to .

4.1.2. Consequences on the Dynamics

- -

- The usual dynamic equation is changed :

- -

- For a free motion constant we get .

- -

- During a displacement the invariant reference length is . However, a terrestrial observer measures and, if this measurement could be made, he would conclude that the reference length varies in the Universe! (-effect). Obviously this effect is an illusion, the true reference length does not vary (the displacement of an atom does not modify its size).

| measurable | non-measurable |

| Photometric measurement | (fictitious) |

| Spectroscopic velocity measurement | (fictitious) |

| proper motion measurement |

4.2. Calibration of the Kappa-Effect

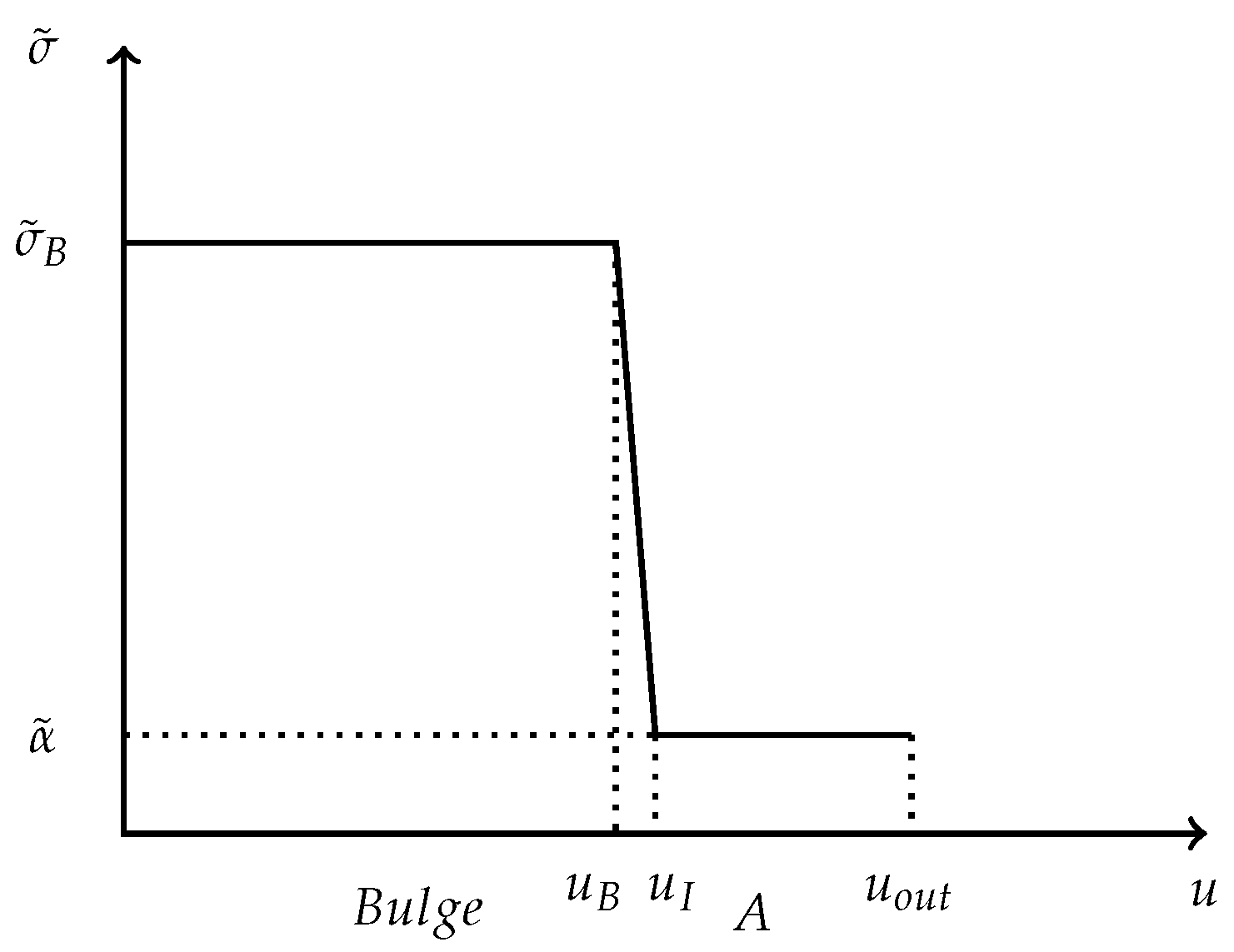

4.2.1. Mass Distribution and Velocity Profile in a Spiral Galaxy

- -

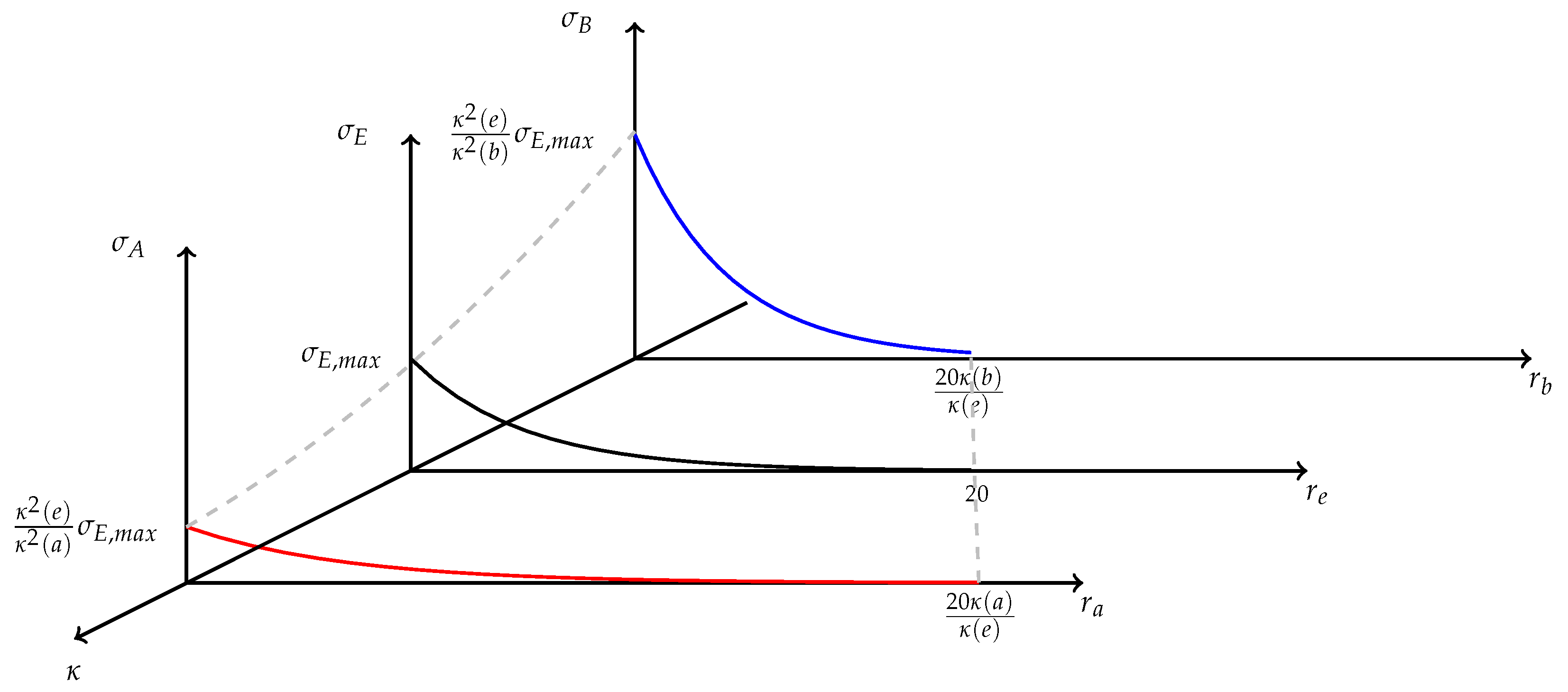

- Let denote the distance in the e-leaf between and the center C of .

- -

- Let be the areal mass density profile apparent to E.

- -

- Let the velocity profile predicted by the Newtonian me-chanics according to the density profile (which is problematically not observed)

- -

- The distance between and C would be

- -

- Assuming conservation of local mass : The mass of a given region does not depend on wether it is measured by a sitting-observer or an itinerant- observer : The areal mass density2 would be

- -

- A velocity profile predicted by the Newtonian mechanics accor- ding to the profile .

- -

- The distribution must be stable to gravitational perturbations.

- -

- The distribution and the rescaling should produce the observed velocity profiles.

- i.

- and (for and )

- ii.

- and (for and )

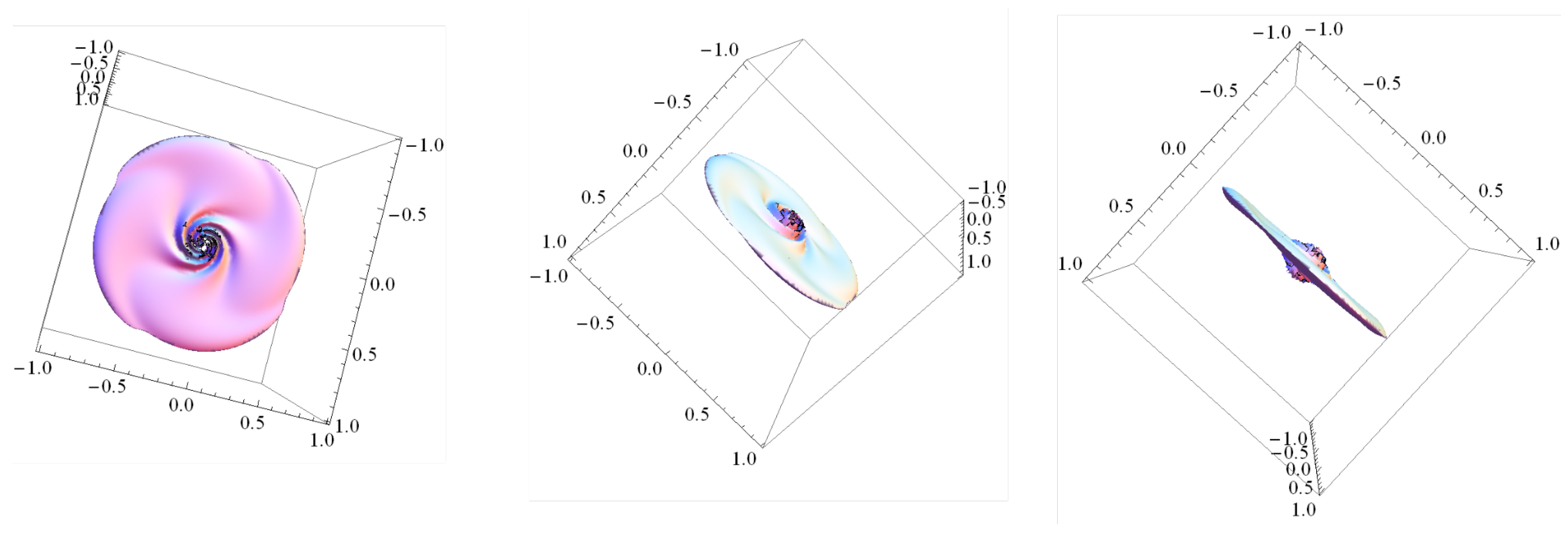

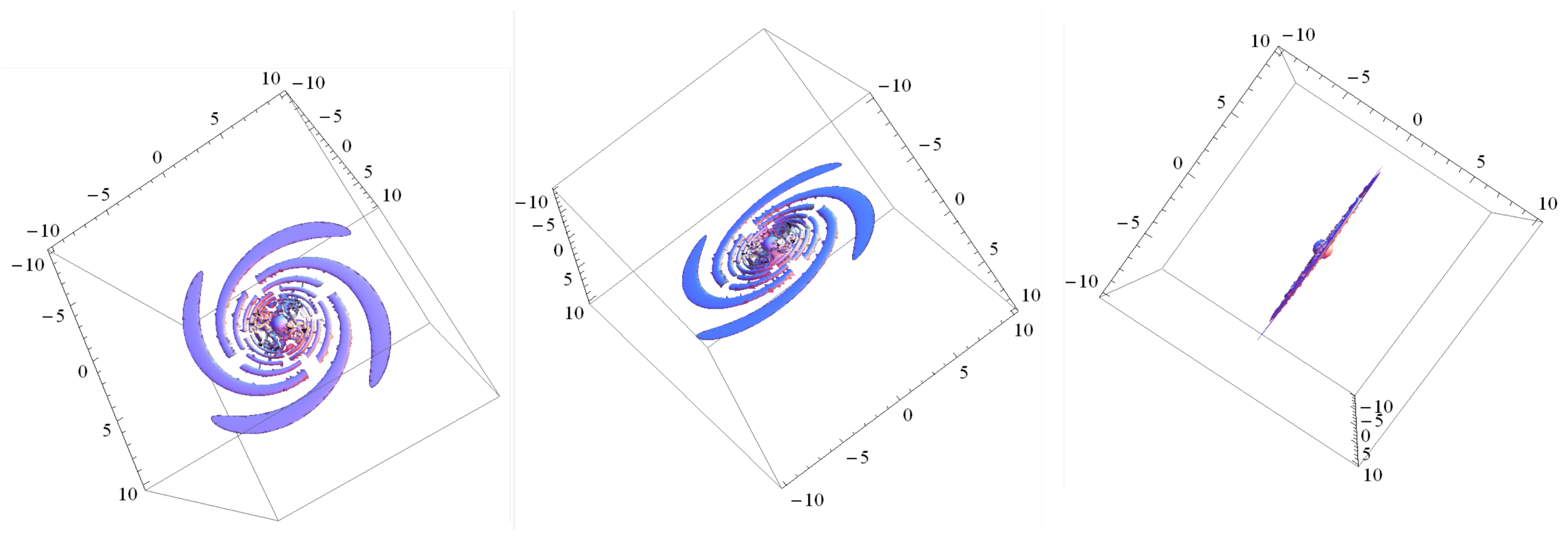

4.2.2. Shape of a Spiral Galaxy and Winding Problem.

4.3. Other Phenomena Interpreted in the Framework of the Kappa-Effect

4.3.1. The Mass of the Galaxy Clusters

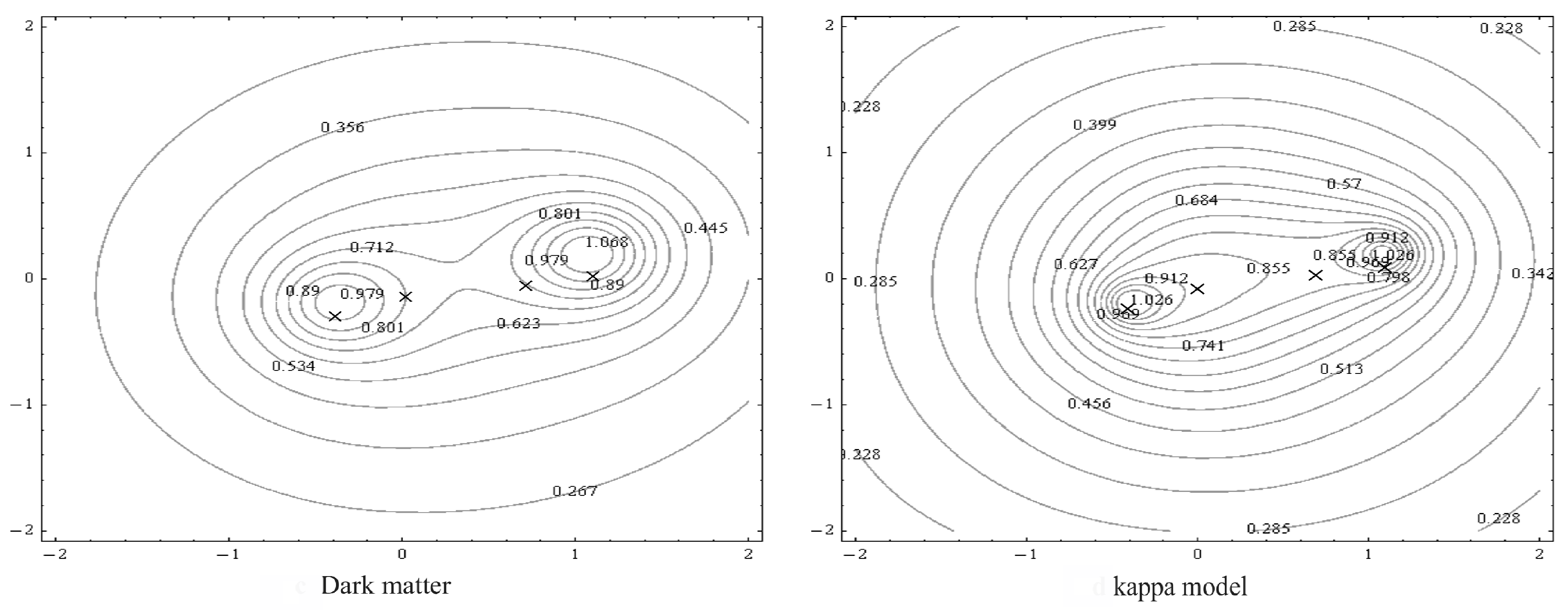

4.3.2. The Bullet Cluster

- We apply the -transform (or corresponding principle) on this quadratic form

- (the time is left unchanged by the -transform), ().

- and

- , ).

- and do not reside in the same space ( is in the tangent space), and are independant. Thus, more generally, they can even be multiplied by a different factor. Then we obtain the true , that is to say the one expressed in the Einstein-basis

4.3.3. The Anisotropies of the Cosmic Background (CMB)

4.3.4. The Hoag’s Object

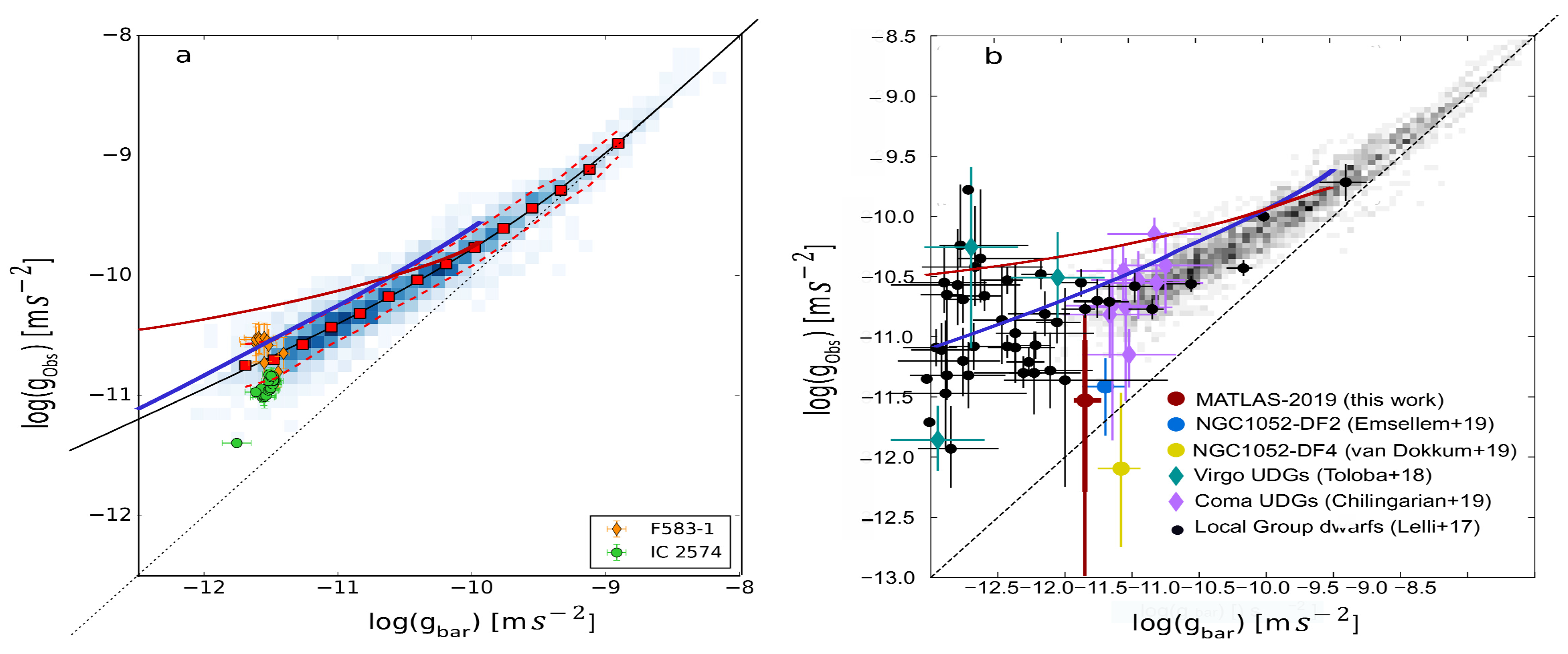

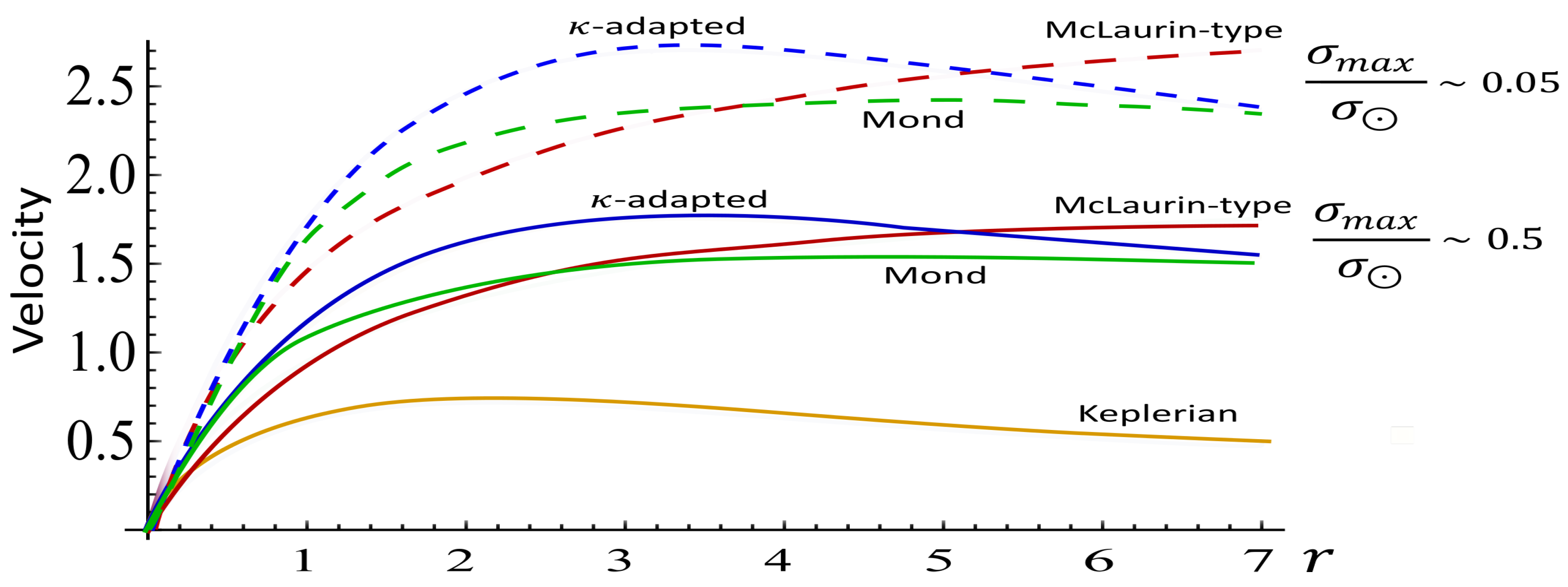

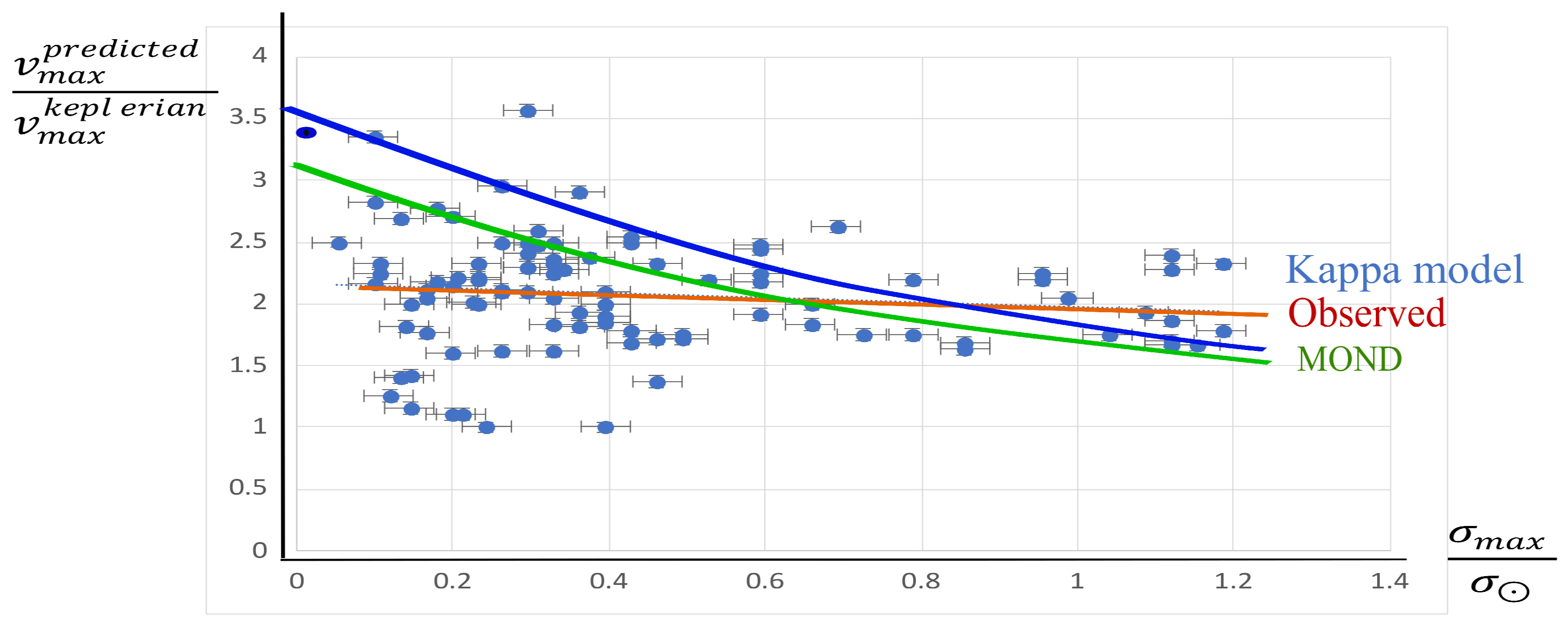

4.4. MOND Versus MOG Versus Kappa-Model

5. Conclusion

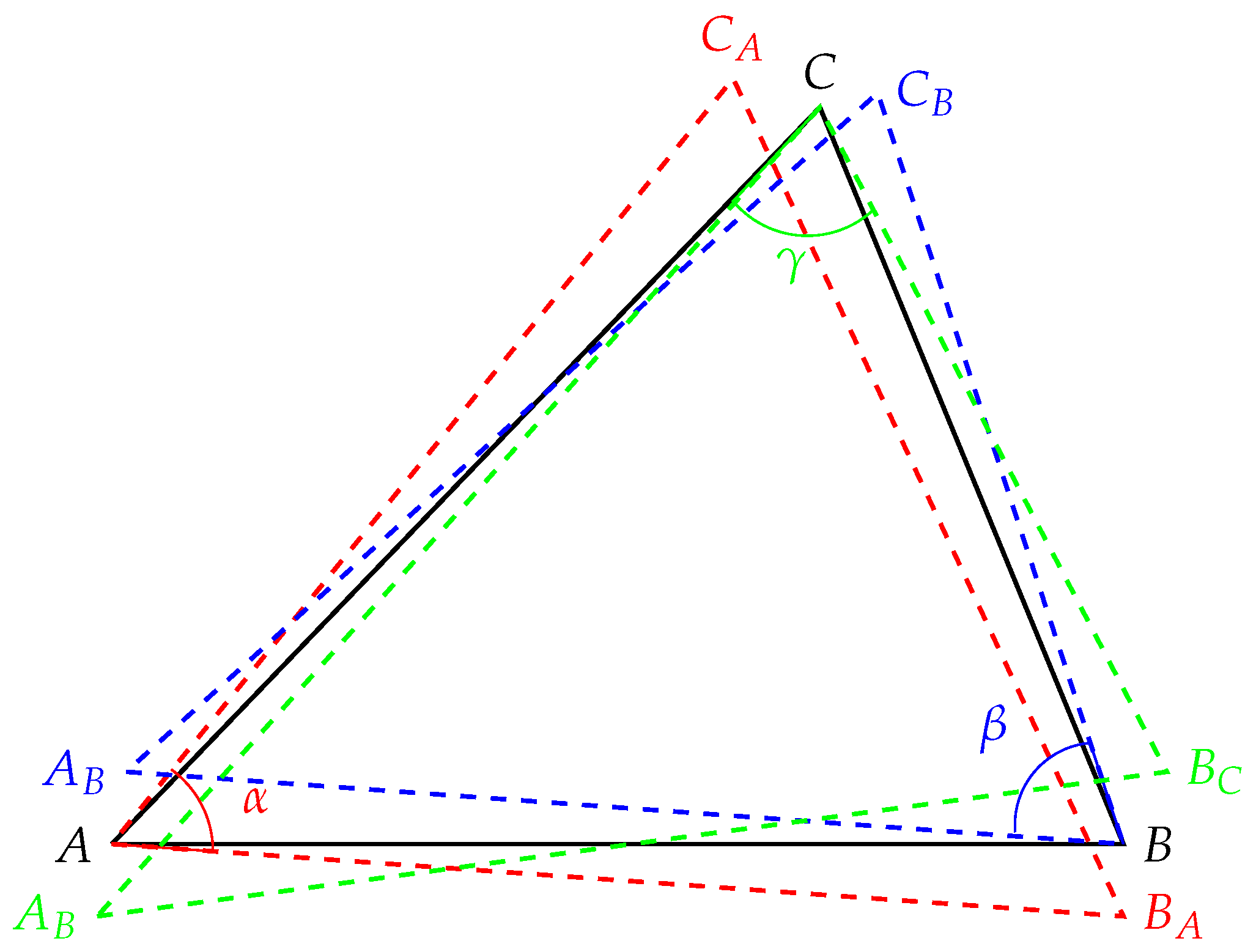

Appendix A. Trigonometric Distances and κ-Curvature

Appendix B. The Origin of the κ-Aberration

Appendix C. The Translation of an Extended Object (Galaxy) Within the Framework of the Kappa-Model

References

- Beordo, W., Crosta, M. and Lattanzi, M.G. Exploring Milky Way rotation curves with Gaia DR3: a comparison between ΛCDM, MOND, and general relativistic approaches. JCAP 2024, 12, 024. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, O., Hammer, F., Wang, H., Wang, J., Amram, P., Chemin, L. and Yang, Y. Detection of the Keplerian Decline in the Milky Way Rotation Curve. A&A 2023, 678, A208. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, G.; Pernas, L. Some Considerations about a Potential Application of the Abstract Concept of Asymmetric Distance in the Field of Astrophysics. 2020. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02530737.

- Pascoli, G. The κ-model, a minimal model alternative to dark matter: Application to the galactic rotation problem. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2022, 367, 62. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, G. arXiv: 2205.03062 2022b. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, G. The κ-Model under the Test of the SPARC Database. Universe 2024, 10, 151. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, G. A comparative study of MOND and MOG theories versus the κ-model: An application to galaxy clusters. Can. J. Phys. 2023, 101, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pascoli, G., Pernas L. Is Dark Matter a Misinterpretation of a Perspective Effect? Symmetry 2024,16, 7, 937. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the newtonian dynamics : implications for galaxy systems. ApJ. 1983, 270, 384. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. MOND theory. Can. J. Phys. 2015, 93, 107. [CrossRef]

- Moffat, J. Scalar–tensor–vector gravity theory. JCAP 2006, 03, 004. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S-Q., Zhan, BG., Wang, QL., Shao, CG., Tu, LC., Tan, WH., and Luo. J. Test of the Gravitational Inverse Square Law at Millimeter Ranges. Phys.Rev.Lett.2012, 108, 081101. [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E.P. Emergent Gravity and the Dark Universe SciPost Phys. 2017, 2, 016. [CrossRef]

- Maeder A. Dynamical Effects of the Scale Invariance of the Empty Space: The Fall of Dark Matter? Apj 2017, 849, 158. [CrossRef]

- Gueorguiev, V.G. and Maeder, A. The Scale-Invariant Vacuum Paradigm: Main Results and Current Progress Review. Symmetry 2024, 16, 657. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. Testing CCC+TL Cosmology with Observed Baryon Acoustic Oscillation Features. ApJ 2024, 964, 55. [CrossRef]

- Famey, B., and McGaugh, SS. Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND): Observational Phenomenology and Relativistic Extensions. Living Astronomy 2012, 15, 10. [CrossRef]

- Varieschi, G.U. Relativistic Fractional-Dimension Gravity. Universe 2021, 7, 387. [CrossRef]

- Varieschi, G.U. Newtonian fractional-dimension gravity and the external field effect. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Cesare, V., Diaferio, A., Matsakos, T., Angus G. Dynamics of DiskMass Survey galaxies in refracted gravity. A&A 2020, 637, A70. [CrossRef]

- Cesare, V., Diaferio, A., Matsakos, T. The dynamics of three nearby E0 galaxies in refracted gravity. A&A 2022, 657, A133. [CrossRef]

- Cesare, V. Dark Coincidences: Small-Scale Solutions with Refracted Gravity and MOND. Universe 2023, 9(1), 56. [CrossRef]

- Li P. The Dark Matter Problem in Rotationally Supported Galaxies. Thesis, Case Reserve Western University 2020.

- Moffat J.W., Rahvar S. The MOG weak field approximation and observational test of galaxy rotation curves. Mon Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 436, 1439. [CrossRef]

- Browstein J.R., Moffat J.W. Galaxy cluster masses without non-baryonic dark matter. MNRAS 2006, 367, 527. [CrossRef]

- Browstein J.R., Moffat J.W. The Bullet Cluster 1E0657-558 evidence shows modified gravity in the absence of dark matter. MNRAS 2007, 382, 29. [CrossRef]

- Moffat J.W., Toth V.T. Cosmological Observations in a Modified Theory of Gravity (MOG). Galaxies 2013, 1, 65. [CrossRef]

- Skordis C., Zlosnik T. New Relativistic Theory for Modified Newtonian Dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 161302. [CrossRef]

- Ostriker J.P., Peebles P.J.E. A Numerical Study of the Stability of Flattened Galaxies: or, can Cold Galaxies Survive?. ApJ 1973, 186, 467. [CrossRef]

- Lelli F., McGaugh S.S., Schombert J.M. and Pawlowski M.S. One Law to Rule Them All: The Radial Acceleration Relation of Galaxies. ApJ. 2017, 836, 152. [CrossRef]

- Mülller, O. et al. Spectroscopic study of MATLAS-2019 with MUSE: An ultra-diffuse galaxy with an excess of old globular clusters. A&A 2020, 640, A 106. [CrossRef]

- Lelli, F., McGaugh, SS., Schombert, J. M. VizieR Online Data Catalog: Mass models for 175 disk galaxies with SPARC. AJ 2016, 152, 157L. [CrossRef]

- Mistele, T., McGaugh, SS., Lelli, F., Schombert, J.M., and Li P. Indefinitely Flat Circular Velocities and the Baryonic Tully-Fisher Relation from Weak Lensing. ApJL 2024, 969, L3. [CrossRef]

- Chan M.H., Zhang Y., Del Popolo A. Are the Galaxies with Indefinitely Flat Circular Velocities Located Inside Large Dark Matter Haloes? Universe 2025, 11, 4. [CrossRef]

- Corbelli E. and Salucci P. Testing modified Newtonian dynamics with Local Group spiral galaxies. MNRAS 2007, 374, 1051. [CrossRef]

- Banik I., Thies I., Famaey B., Candlish G., Kroupa P. and Ibata R. The Global Stability of M33 in MOND. ApJ 2020, 905, 135. [CrossRef]

- Corbelli E., Thilker D., Zibetti S., Giovanardi C., and P. Salucci. Dynamical signatures of a ΛCDM-halo and the distribution of the baryons in M33. A&A 2014, 572, A23. [CrossRef]

- Kam S.Z., C. Carignan, Chemin L., Foster T., Elson E. and Jarrett T.H. H i Kinematics and Mass Distribution of Messier 33. AJ 2017, 154,41. [CrossRef]

- Reiprich; T.H, Cosmological Implications and Physical Properties of an X-Ray Flux-Limited Sample of Galaxy Clusters. Ph.D.Dissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München 2001.

- Reiprich, T.H., Böhringer, H. The Mass Function of an X-Ray Flux-limited Sample of Galaxy Clusters. ApJ 2002, 567, 716. [CrossRef]

- Bradač, M., Schneider, P., Lombardi, M., Erben, T. Strong and weak lensing united. I. The combined strong and weak lensing cluster mass reconstruction method. A&A 2005, 437, 39. [CrossRef]

- Bradač, M., Clowe, D., Gonzalez, A.H., Marshall, P., Forman, W., Jones, C., Markevitch, M., Randall, S., Schrabback, T. and Zaritsky, D. Strong and Weak Lensing United. III. Measuring the Mass Distribution of the Merging Galaxy Cluster 1ES 0657–558. ApJ 2006, 652, 937. [CrossRef]

- Finkelman, I., Moiseev, A., Brosch, N., Katkov, I. Hoag’s Object: evidence for cold accretion on to an elliptical galaxy. MNRAS 2011, 418, 1834. [CrossRef]

- Brosch, N. Finkelman, I., Tom Oosterloo, T., Gyula Jozsa, G.,and Alexei Moiseev. HI in HO: Hoag’s object revisited. MNRAS 2013, 435, 475. [CrossRef]

- Bannikova, E.Y. The structure and stability of orbits in Hoag-like ring systems. MNRAS 2018, 476, 3269. [CrossRef]

- Hoag, A. A peculiar object in Serpens. AJ 1950, 55, 170. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, X., Cookson, S. Cortés, R.A.M. Internal kinematics of Gaia eDR3 wide binaries. MNRAS 2022, 509, 2304. [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.H. Breakdown of the Newton–Einstein Standard Gravity at Low Acceleration in Internal Dynamics of Wide Binary Stars. Astrophys. L. 2023, 952, 128. [CrossRef]

- Banik, I., Pittordis, C., Sutherland, W., Famaey, B., Ibata, R., Mieske, S. Zhao, HS. Strong constraints on the gravitational law from Gaia DR3 wide binaries. MNRAS 2024, 527, 3, 4573. [CrossRef]

| 1 | As a matter of fact the estimate of the content in dark matter strongly varies following the method used [1, 2]. On the contrary, in the -model the proper motions (tangential motions) and the radial motions estimated from the Earth have to be differently treated. In the framework of this model the proper motions which are seen are fictitious (considerably magnified in the region where the mean density is weak), while the measured-by-spectroscopy radial motions are real quantities (even though the line of sight can be displaced, see Appendix B). However, this suggestion remains difficult to verify, as it would require a very good understanding of the average surface density in the Milky Way along a galactic radius. However we can think that the rotation curve determined by using the -model will probably be a compromise between a flat curve (such as that predicted by the dark matter paradigm, MOND or MOG) and a purely Keplerian curve. But in order to validate this, however, a lot of work also remains to be undertaken, requiring a reinterpretation of satellite data from GAIA, in particular the proper motions, the evaluation of which now depends on the mean density. In other words, the rotation profile of a galaxy is not seen in the same manner depending on whether you are inside the galaxy or outside. The great interest of this work would thus be to be able to discriminate between MOND and the -model, which both give fairly similar rotation curves with regard to other galaxies [6], while producing a different rotation curve in the special case of the Milky Way . |

| 2 | This relationship univocally links and . |

| 3 | This value is the reference value chosen in [6]. |

| 4 | More rigorously this value is not equal, but relatively close (within a factor two) to the galactic surface mass density estimated in the solar region, more exactly (in comparison with the high range of surface densities seen in a disk galaxy, varying from in the inner regions, from the center, to in the outskirts, from the centre). |

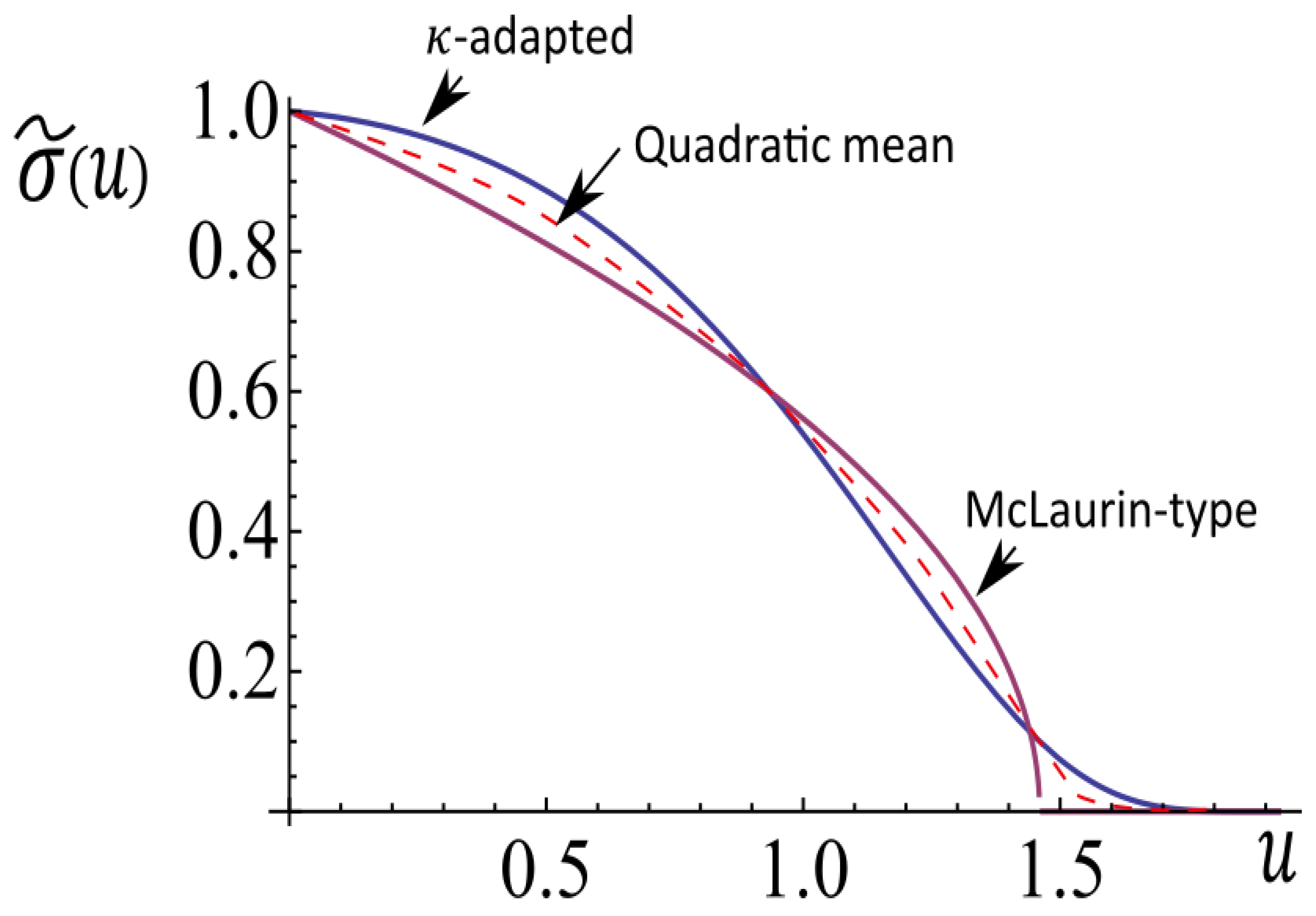

| 5 | A McLaurin profile (quadratic in u) slightly differs from the McLaurin-type (linear in u) profiles used above. |

| 6 | In some cass this flatness can be followed up to very huge distances from the galaxy center, by weak gravitational lensing measurement [33,34]. This type of obervational data is uneasy to explain with dark matter because a very huge quantity of this exotic matter would be needed for that. On the other hand it is very easy to explain it with MOND or -model. In the framework of the -model the phenomenon is located beyond the mass density galaxy cut-off (very well determined in the Newton-basis, but not in the bundle). In this region the mass density is very weak and the (fictitious) stretching of space very strong. An extended and flat weak gravitational lensing appears in the bundle. |

| 7 | A couple of -values is indeed associated to each galaxy, (inner and outer [8]). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).