Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

Assessment of the Consumption of Fermented Foods

Demographic, Anthropometric and Health Data

Data Analysis

3. Results

Study Population Demographics

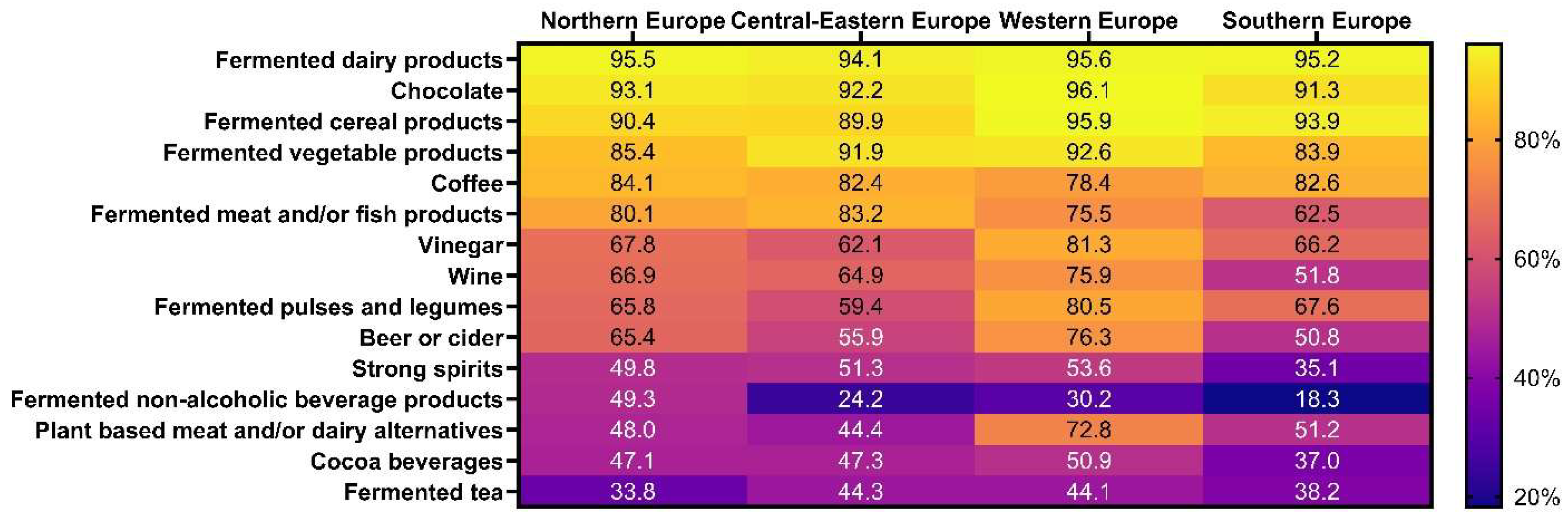

Prevalence of Fermented Foods Consumption by European Region

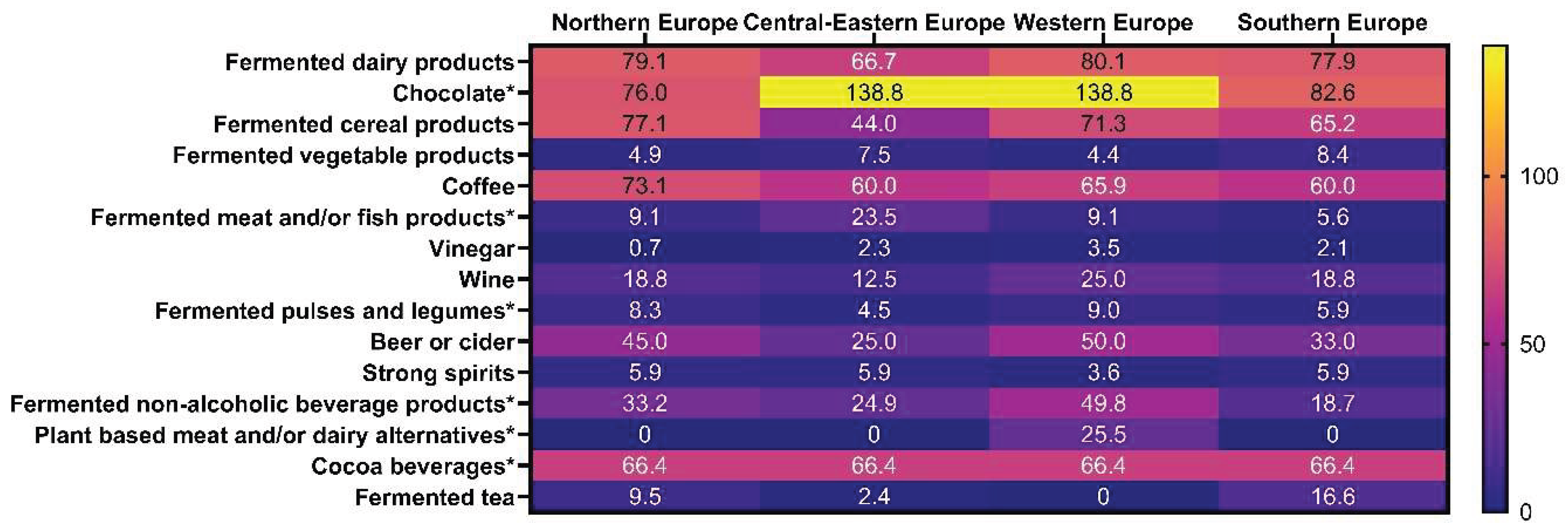

Intake Amounts of Fermented Foods Among Consumers

Relationship Between Consumption Prevalence and Intake Amounts

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tamang, J.P.; Cotter, P.D.; Endo, A.; Han, N.S.; Kort, R.; Liu, S.Q.; Mayo, B.; Westerik, N.; Hutkins, R. Fermented foods in a global age: East meets West. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 184-217. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, G.; Ali, S.A. Dairy-Based Probiotic-Fermented Functional Foods: An Update on Their Health-Promoting Properties. Fermentation 2022, 8, 425. [CrossRef]

- Valentino, V.; Magliulo, R.; Farsi, D.; Cotter, P.D.; O’Sullivan, O.; Ercolini, D.; Francesca. Fermented foods, their microbiome and its potential in boosting human health. Microbial Biotechnology 2024, 17. [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, S.; Akpinar, A.; Assunção, R.; Bär, C.; Bavaro, S.L.; Berkel Kasikci, M.; Domínguez-Soberanes, J.; Capozzi, V.; Cotter, P.D.; Doo, E.-H., et al. Health benefits and risks of fermented foods—the PIMENTO initiative. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Leeuwendaal, N.K.; Stanton, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Beresford, T.P. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1527. [CrossRef]

- Şanlier, N.; Gökcen, B.B.; Sezgin, A.C. Health benefits of fermented foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 506-527. [CrossRef]

- Keyvan, E.; Adesemoye, E.; Champomier-Vergès, M.-C.; Chanséaume-Bussiere, E.; Mardon, J.; Nikolovska Nedelkoska, D.; Palamutoglu, R.; Russo, P.; Sarand, I.; Songre-Ouattara, L., et al. Vitamins formed by microorganisms in fermented foods: effects on human vitamin status—a systematic narrative review. Frontiers in Nutrition 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, R.; Schneider, E.; Gunnigle, E.; Cotter, P.D.; Cryan, J.F. Fermented foods: Harnessing their potential to modulate the microbiota-gut-brain axis for mental health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2024, 158, 105562. [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligné, B.; Gänzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A., et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2017, 44, 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Rezac, S.; Kok, C.R.; Heermann, M.; Hutkins, R. Fermented Foods as a Dietary Source of Live Organisms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Tarfeen, N.; Mohamed, H.; Song, Y. Fermented Foods: Their Health-Promoting Components and Potential Effects on Gut Microbiota. Fermentation 2023, 9, 118. [CrossRef]

- Rul, F.; Béra-Maillet, C.; Champomier-Vergès, M.C.; El-Mecherfi, K.E.; Foligné, B.; Michalski, M.C.; Milenkovic, D.; Savary-Auzeloux, I. Underlying evidence for the health benefits of fermented foods in humans. Food & Function 2022, 13, 4804-4824. [CrossRef]

- Tamang, J.P.; Watanabe, K.; Holzapfel, W.H. Review: Diversity of Microorganisms in Global Fermented Foods and Beverages. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Cuamatzin-García, L.; Rodríguez-Rugarcía, P.; El-Kassis, E.G.; Galicia, G.; Meza-Jiménez, M.D.L.; Baños-Lara, M.D.R.; Zaragoza-Maldonado, D.S.; Pérez-Armendáriz, B. Traditional Fermented Foods and Beverages from around the World and Their Health Benefits. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1151. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Ahn, J.; Son, H.-S. Ethnic fermented foods of the world: an overview. Journal of Ethnic Foods 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Santa, D.; Huch, M.; Stoll, D.A.; Cunedioglu, H.; Priidik, R.; Karakaş-Budak, B.; Matalas, A.; Pennone, V.; Girija, A.; Arranz, E., et al. Health benefits of ethnic fermented foods. Frontiers in Nutrition 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Baschali, A.; Tsakalidou, E.; Kyriacou, A.; Karavasiloglou, N.; Matalas, A.-L. Traditional low-alcoholic and non-alcoholic fermented beverages consumed in European countries: a neglected food group. Nutrition Research Reviews 2017, 30, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Van Reckem, E.; Geeraerts, W.; Charmpi, C.; Van Der Veken, D.; De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Exploring the Link Between the Geographical Origin of European Fermented Foods and the Diversity of Their Bacterial Communities: The Case of Fermented Meats. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Varga, L.; Greff, B. Nutritional and functional aspects of European cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Food Res Int 2025, 209, 116221. [CrossRef]

- Praagman, J.; Dalmeijer, G.W.; Van Der Schouw, Y.T.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Monique Verschuren, W.M.; Bas Bueno-De-Mesquita, H.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Beulens, J.W.J. The relationship between fermented food intake and mortality risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Netherlands cohort. British Journal of Nutrition 2015, 113, 498-506. [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.; Reale, A. A Holistic Review on Euro-Asian Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermented Cereals and Vegetables. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1176. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.J.; Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; Burton, K.J.; Vergères, G.; Feskens, E.J.M. Prevalence of fermented foods in the Dutch adult diet and validation of a food frequency questionnaire for estimating their intake in the NQplus cohort. BMC nutrition 2020, 6. [CrossRef]

- Pertziger, E.; von Ah, U.; Bochud, M.; Chatelan, A.; Haldemann, J.; Hillesheim, E.; Kaiser, M.; Vergères, G.; Burton-Pimentel, K.J. Classification and Estimation of Dietary Live Microorganisms and Fermented Foods Intake in Swiss Adults. J Nutr 2025, 155, 2717-2728. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, E.B.; Perelman, D.; Ward, C.P.; Sonnenburg, E.D.; Gardner, C.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Unpacking Food Fermentation: Clinically Relevant Tools for Fermented Food Identification and Consumption. Advances in Nutrition 2025, 16, 100412. [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, I.; Forouhi, N.G.; Beulens, J.W.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Agnoli, C.; Arriola, L.; Balkau, B.; Barricarte, A.; Boeing, H.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B., et al. The amount and type of dairy product intake and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the EPIC-InterAct Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 96, 382-390. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Bae, J.H. Fermented food intake is associated with a reduced likelihood of atopic dermatitis in an adult population (Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2012-2013). Nutr Res 2016, 36, 125-133. [CrossRef]

- Fujihashi, H.; Sasaki, S. Identification and estimation of the intake of fermented foods and their contribution to energy and nutrients among Japanese adults. Public Health Nutrition 2024, 27, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- PIMENTO. Promoting Innovation of ferMENTed fOods (PIMENTO)-CA20128. Availabe online: https://www.cost.eu/actions/CA20128/ (accessed on October 15 2023).

- Magriplis, E.; Smiliotopoulos, T.; Myrintzou, N.; Burton-Pimentel, K.J.; Adamberg, S.; Adamberg, K.; Agagündüz, D.; Atanasova-Pancevska, N.; Beglaryan, M.; Brolsma, E.M.B., et al. Validation of the fermented food frequency questionnaire to assess consumption across four European regions: a study within the promoting innovation of fermented foods cost action. Frontiers in Nutrition 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Magriplis, E.; Kotopoulou, S.; Adamberg, S.; Burton-Pimentel, K.J.; Kitryte-Syrpa, V.; Laranjo, M.; Meslier, V.; Smiliotopoulos, T.; Vergères, G.; Vidovic, B., et al. Fermented Food Consumption Across European Regions: Protocol for the Development and Validation of the Web-Based Fermented Foods Frequency Questionnaire (3FQ). JMIR Res Protoc 2025, 14, e69212. [CrossRef]

- European Union. EuroVoc. Availabe online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/browse/eurovoc.html?params=72,7211#arrow_1088 (accessed on April 20).

- Shrestha, B.; Dunn, L. The Declaration of Helsinki on Medical Research involving Human Subjects: A Review of Seventh Revision. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2020, 17, 548-552. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Health Observatory. Availabe online: .http://www.who.int/gho. (accessed on November 6).

- Park, I.; Mannaa, M. Fermented Foods as Functional Systems: Microbial Communities and Metabolites Influencing Gut Health and Systemic Outcomes. Foods 2025, 14, 2292. [CrossRef]

- Thierry, A.; Madec, M.-N.; Chuat, V.; Bage, A.-S.; Picard, O.; Grondin, C.; Rué, O.; Mariadassou, M.; Marché, L.; Valence, F. Microbial communities of a variety of 75 homemade fermented vegetables. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.S.; El Sheikha, A.F.; Hammami, R.; Kumar, A. Traditionally fermented pickles: How the microbial diversity associated with their nutritional and health benefits? Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 70, 103971. [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D., et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on fermented foods. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021, 18, 196-208. [CrossRef]

- Mutoh, N.; Kakiuchi, I.; Kato, K.; Xu, C.; Iwabuchi, N.; Ayukawa, M.; Kiyosawa, K.; Igarashi, K.; Tanaka, M.; Nakamura, M., et al. Heat-Killed L. helveticus Enhances Positive Mood States: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Brain Sciences 2023, 13, 973. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H., et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021, 18, 649-667. [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Hutkins, R.; Hill, C.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Cifelli, C.J.; Gahche, J.; Slavin, J.L.; Merenstein, D.; Tancredi, D.J.; Sanders, M.E. A Classification System for Defining and Estimating Dietary Intake of Live Microbes in US Adults and Children. J Nutr 2022, 152, 1729-1736. [CrossRef]

- Henry, K.; Valliant, R. 1 Methods for Adjusting Survey Weights When Estimating a Total. 2012.

| Characteristic | European region | p-value | |||||||

| Northern Europe | Central-Eastern Europe | Western Europe | Southern Europe | ||||||

| (n=2,315) | (n=5,185) | (n=2,577) | (n=2,569) | ||||||

| % | CI | % | CI | % | CI | % | CI | ||

| n2=12,646 | 4.2% | - | 22.1% | - | 35.3% | - | 38.5% | - | |

| Age 3 | 45 (34, 56) | - | 39 (26, 50) | - | 38 (28, 52) | - | 40 (27, 52) | - | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Female | 65.9% | (63.97 - 67.84) | 70.6% | (69.37 - 71.86) | 68.7% | (66.87 - 70.47) | 65.7% | (63.79 - 67.47) | |

| Male | 34.1% | (32.16 - 36.03) | 29.4% | (28.14 - 30.63) | 31.3% | (29.53 - 33.13) | 34.4% | (32.53 - 33.17) | |

| Age group | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age 18-50 | 61.5% | (59.53 - 63.50) | 75.8% | (74.64 - 76.97) | 73.2% | (71.43 - 74.86) | 71.9% | (70.07 - 73.57) | |

| Age 50+ | 38.5% | (36.50 - 40.47) | 24.2% | (23.03 - 25.36) | 26.8% | (25.14 - 28.57) | 28.1% | (26.43 - 29.93) | |

| BMI4 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Underweight | 3.5% | (2.72 - 4.37) | 3.3% | (2.76 - 3.84) | 5.2% | (4.32 - 6.23) | 4.5% | (3.72 - 5.53) | |

| Normal weight | 49.7% | (47.45 - 51.93) | 56.4% | (54.89 - 57.89) | 65.8% | (63.77 - 67.82) | 53.6% | (51.47 - 55.79) | |

| Overweight | 28.7% | (26.70 - 30.75) | 28.9% | (27.53 - 30.27) | 21.2% | (19.51 - 23.01) | 28.6% | (26.68 - 30.60) | |

| Obesity | 18.2% | (16.52 - 19.97) | 11.5% | (10.54 - 12.46) | 7.8% | (6.70 - 9.00) | 13.2% | (11.83 - 14.76) | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Primary level or less | 1.0% | (0.68 - 1.52) | 0.8% | (0.60 - 1.10) | 0.6% | (0.33 - 0.93) | 6.6% | (5.66 - 7.60) | |

| Secondary level | 30.5% | (28.61 - 32.41) | 31.4% | (30.14 - 32.70) | 15.6% | (14.24 - 17.07) | 21.7% | (20.17 - 23.39) | |

| Bachelor’s/University level | 31.0% | (29.09 - 32.90) | 37.5% | (36.21 - 38.88) | 29.2% | (27.50 - 31.04) | 31.8% | (29.99 - 33.62) | |

| Postgraduate (MSc/PhD) level | 37.5% | (35.57 - 39.56) | 30.3% | (29.00 - 31.54) | 54.6% | (52.67 - 56.54) | 39.9% | (38.03 - 41.84) | |

| Employment Status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Employed (full-time) | 65.4% | (63.44 - 67.38) | 67.1% | (65.82 - 68.43) | 58.1% | (56.19 - 60.02) | 59.2% | (57.26 - 61.10) | |

| Employed (part-time) | 12.5% | (11.15 - 13.89) | 5.1% | (4.52 - 5.75) | 22.9% | (21.30 - 24.57) | 7.3% | (6.37 - 8.41) | |

| Student | 6.9% | (5.96 - 8.07) | 16.2% | (15.15 - 17.20) | 12.1% | (10.9 - 13.46) | 18.8% | (17.31 - 20.37) | |

| Retired | 9.0% | (7.87 - 10.24) | 4.5% | (3.96 - 5.11) | 4.5% | (3.75 - 5.37) | 5.7% | (4.85 - 6.67) | |

| Unemployed | 4.4% | (3.63 - 5.34) | 5.5% | (4.92 - 6.19) | 1.8% | (1.33 - 2.37) | 2.6% | (2.03 - 3.29) | |

| Homemaker | 1.8% | (1.31 - 2.42) | 1.6% | (1.28 - 1.97) | 0.6% | (0.36 - 0.98) | 6.4% | (5.52 - 7.44) | |

| Marital Status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Single | 26.6% | (24.83 28.50) | 36.5% | (35.09 - 37.82) | 30.6% | (28.84 - 32.45) | 40.5% | (38.61 - 42.46) | |

| Married/Living with spouse | 63.4% | (61.38 - 65.38) | 56.1% | (54.70 - 57.51) | 64.2% | (62.28 - 66.03) | 55.1% | (53.11 - 57.01) | |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 10.0% | (8.79 - 11.28) | 7.4% | (6.73 - 8.22) | 5.2% | (4.41 - 6.15) | 4.4% | (3.67 - 5.29) | |

| Smoking Status | |||||||||

| Current smoker | 16.5% | (15.00 - 18.03) | 22.0% | (20.91 - 23.17) | 7.9% | (6.96 - 9.05) | 18.8% | (17.31 - 20.34) | <0.001 |

| E-cigarette/vaping only | 3.9% | (3.20 - 4.79) | 3.2% | (2.80 - 3.77) | 2.1% | (1.65 - 2.78) | 3.0% | (2.41 - 3.75) | |

| Ex-smoker | 13.0% | (11.70 - 14.46) | 8.7% | (7.99 - 9.53) | 11.9% | (10.71 - 13.22) | 9.2% | (8.10 - 10.34) | |

| Non-smoker | 66.6% | (64.65 - 68.51) | 66.0% | (64.70 - 67.29) | 78.0% | (76.36 - 79.57) | 69.1% | (67.23 - 70.82) | |

| Scientific Background on Food Science, Nutrition | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 72.4% | (70.50 - 74.17) | 72.2% | (70.96 - 73.45) | 64.3% | (62.46 - 66.18) | 62.3% | (60.40 - 64.18) | |

| Yes | 27.6% | (25.83- 29.50) | 27.8% | (26.55 - 29.04) | 35.7% | (33.82 - 37.54) | 37.7% | (35.82 - 39.60) | |

| Any Chronic Condition Diagnosed | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 58.4% | (56.35 - 60.41) | 73. 0% | (71.74- 74.19) | 74.0% | (72.24 - 75.66) | 66.3% | (64.39 - 68.08) | |

| Yes | 41.6% | (39.59- 43.65) | 27.0% | (25.81 - 28.26) | 26.0% | (24.34 - 27.76) | 33.7% | (31.92 - 35.61) | |

| Multimorbidity Status | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No chronic conditions | 58.4% | (56.35- 60.41) | 73.0% | (71.74 - 74.19) | 74.0% | (72.24 - 75.66) | 66.3% | (64.39 - 68.08) | |

| One chronic condition | 28.1% | (26.23 - 29.94) | 21.2% | (20.07 - 22.32) | 20.3% | (18.76 - 21.90) | 25.1% | (23.47 - 26.85) | |

| Two chronic conditions | 9.1% | (7.94 - 10.31) | 4.4% | (3.89 - 5.03) | 4.5% | (3.72 - 5.34) | 6.3% | (5.44 - 7.35) | |

| Three or more chronic conditions | 4.5% | (3.72 - 5.44) | 1.4% | (1.13 - 1.79) | 1.3% | (0.90 - 1.78) | 2.3% | (1.78 - 2.96) | |

| Any Cardiometabolic Condition Diagnosed | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 72.9% | (71.01 - 74.67) | 81. 8% | (80.70 - 82.83) | 88.1% | (86.82 - 89.34) | 78.6% | (76.96 - 80.16) | |

| Yes | 27.1% | (25.33 - 28.99) | 18.2% | (17.17 - 19.30) | 11.9% | (10.66 - 13.18) | 21.4% | (19.84 - 23.04) | |

| European region | ||||||||||

| Northern Europe | Central-Eastern Europe | Western Europe | Southern Europe | |||||||

| Characteristic | (n=2,315) | (n=5,185) | (n=2,577) | (n=2,569) | p-value | p-value* | p-value1 | p-value2 | p-value3 | p-value4 |

| Plant-based cheese (g/week) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 5.7 ) | 0 ( 0, 10.5 ) | 0 ( 0, 5.7 ) | 0.019 | 0.009 | 0.565 | <0.001 | 0.062 | 0.009 |

| Plant-based meat (g/week) | 0 ( 0, 5.8 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 10.5 ( 0, 37.5 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.474 | 0.029 | 0.048 | 0.744 |

| Plant-based yoghurt (g/week) | 0 ( 0, 14 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 28 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.393 | 0.003 | 0.170 | 0.104 |

| Total Plant-based meat or dairy products (g/week) | 0 ( 0, 28 ) | 0 ( 0, 10.5 ) | 25.5 ( 0, 110.3 ) | 0 ( 0, 19.4 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.287 | <0.001 | 0.028 | 0.032 |

| Hard Cheese (g/day) | 1 ( 0.4, 4.2 ) | 1 ( 0.4, 4.2 ) | 4.2 ( 1, 12.8 ) | 1 ( 0, 8.2 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.025 | 0.056 | 0.130 | 0.051 |

| Semi-hard cheese (g/day) | 8.2 ( 1, 20 ) | 2 ( 0.4, 8.2 ) | 4.2 ( 1, 12.8 ) | 1 ( 0, 8.2 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.976 | <0.001 | 0.324 | <0.001 |

| Semi-hard cheese (g/day) | 1 ( 0, 4.2 ) | 0.4 ( 0, 1 ) | 0.4 ( 0, 1 ) | 0 ( 0, 0.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0285 | 0.361 | 0.019 |

| Soft and/or Fresh cheese (g/day) | 1 ( 0.4, 4.2 ) | 1 ( 0.4, 8.2 ) | 4.2( 1 , 8.2 ) | 4.2 ( 0.4, 20 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.044 | <0.001 | 0.044 | 0.094 |

| Soft and/or Fresh cheese (g/day) | 0.4 ( 0, 1 ) | 0.4 ( 0, 1 ) | 1 ( 0.4, 4.2 ) | 0.4 ( 0, 1 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.685 | 0.007 | 0.659 | 0.393 |

| Total Fermented cheese (g/day) | 10.2 ( 1.6, 28.1 ) | 5 ( 1, 19.4 ) | 20 ( 6.9, 41 ) | 12.8 ( 2.6, 26 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.073 | <0.001 |

| Fermented Yoghurt (g/day) | 42 ( 5, 128 ) | 42 ( 5, 128 ) | 42 ( 10, 128 ) | 42 ( 10, 128 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.233 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| Fermented milk (ml/day) | 9.4 ( 0.7, 69.3 ) | 5 ( 0, 23.1 ) | 0 ( 0, 3.3 ) | 2 ( 0, 21 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.721 | 0.770 |

| Total Fermented milk and yoghurt (g/day) | 55.7 ( 10.6, 160 ) | 45.3 ( 10, 136.3 ) | 44 ( 10, 128 ) | 55.7 ( 10, 130.2 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| Total Fermented dairy products (g/day) | 79.1 ( 24.1, 200.4 ) | 66.7 ( 20.3, 168.7 ) | 80.1 ( 32.2, 174.2 ) | 77.9 ( 27, 163.4 ) | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Fermented chickpeas (g/week) | 3.1 ( 0, 7.7 ) | 3.08 ( 0, 7.7 ) | 0 ( 0, 4.3 ) | 0 ( 0, 14.9 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.025 | 0.039 | 0.206 | 0.005 |

| Fermented beans (g/week) | 0.7 ( 0, 2.1 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 2.1 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 2.1 ) | 0 ( 0, 1.7 ) | 0.501 | 0.22 | 0.723 | 0.643 | 0.006 | 0.001 |

| Fermented pulses-legumes sauce (g/week) | 5.2 ( 0.7, 10.4 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 5.2 ) | 5.2 ( 1.7, 21.7 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 5.2 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.094 | 0.145 | 0.119 | 0.605 |

| Total Fermented pulses and legumes (g/week) | 8.3 ( 3.1, 23.5 ) | 4.5 ( 0.7, 14.9 ) | 9 ( 2.1, 26.2 ) | 5.9 ( 0.7, 26.2 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.029 | 0.026 |

| Fermented meat (g/week) | 5.6( 2.2 , 23.5 ) | 23.5 ( 5.6, 71.7 ) | 5.6 ( 5.6, 23.5 ) | 5.6 ( 2.2, 23.5 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.187 | 0.297 | 0.361 | 0.461 |

| Fermented fish (g/week) | 11.3 ( 11.3, 11.3 ) | 11.3 ( 11.3, 11.3 ) | 11.3 ( 0, 11.3 ) | 11.3 ( 0, 11.3 ) | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.283 | 0.299 | 0.973 | 0.069 |

| Fermented meat or fish sauce (g/week) | 0.7 ( 0, 1.7 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 1.7 ) | 0 ( 0, 0.7 ) | <0.001 | 0.043 | 0.270 | 0.452 | 0.960 | 0.150 |

| Total Fermented meat or fish (g/week) | 9.1 ( 5.2, 29.8 ) | 23.5 ( 5.6, 71.7 ) | 9.1 ( 5.6, 25.6 ) | 5.6 ( 2.2, 23.5 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.547 | 0.354 | 0.390 | 0.259 |

| Olives (g/day) | 1 ( 0.4, 3.5 ) | 2 ( 0.8, 8.4 ) | 2 ( 0.8, 4.2 ) | 6.3 ( 1.4, 20 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.325 | <0.001 | 0.119 | 0.001 |

| Fermented cabbage (i.e., Sauerkraut) (g/day) | 1.4 ( 0.3, 3.5 ) | 1.4 ( 0.3, 3.5 ) | 0.7 ( 0.3, 1.4 ) | 0.3 ( 0, 0.7 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.882 | 0.439 | 0.126 |

| Other fermented vegetables (g/day) | 2.1 ( 0.3, 6.4 ) | 2.92 ( 0.7, 10 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 2.9 ) | 0.28 ( 0, 2.1 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.092 | 0.382 | 0.799 | 0.040 |

| Total Fermented vegetables (g/day) | 4.9 ( 1.6, 18 ) | 7.5 ( 2, 20.4 ) | 4.4 ( 2, 9.6 ) | 8.4 ( 2, 22.3 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.538 | <0.001 |

| White bread (g/day) | 16.7 ( 3.2, 62.1 ) | 25 ( 2, 72.2 ) | 8.3 ( 1.8, 48.3 ) | 27.5 ( 3.8, 79.4 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.618 | 0.974 | 0.059 | 0.001 |

| White sourdough bread (g/day) | 7.9 ( 1.8, 32.6 ) | 1 ( 0, 4.6 ) | 2.6 ( 0.6, 11.3 ) | 1.8 ( 0, 8.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.058 | 0.323 | 0.302 | <0.001 |

| Total White or white sourdough bread (g/day) | 30.1 ( 6.9, 79.4 ) | 25.4 ( 3.2, 76.3 ) | 16.7 ( 3.2, 64.5 ) | 35.9 ( 7.3, 94 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.639 | 0.777 | 0.043 | 0.176 |

| Whole grain bread (g/day) | 16.7 ( 4, 61.3 ) | 4 ( 0.8, 25.4 ) | 19.7 ( 4, 72.2 ) | 5.3 ( 0.8, 30.1 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.192 | 0.005 | 0.694 | <0.001 |

| Whole grain sourdough bread (g/day) | 6.1 ( 1.8, 28.1 ) | 0.4 ( 0, 3.4 ) | 2.9 ( 0.7, 13.9 ) | 0.7 ( 0, 3.5 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.447 | 0.137 | 0.850 | <0.001 |

| Total Whole grain,whole grain sourdough bread (g/day) | 26.5 ( 6.4, 79.7 ) | 5.9 ( 0.8, 25.9 ) | 28.8 ( 6.7, 91.3 ) | 7.7 ( 0.9, 35.7 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.096 | 0.005 | 0.793 | <0.001 |

| Total Bread (g/day) | 75.9 ( 26.1, 168.2 ) | 42 ( 15.8, 106.1 ) | 71.9 ( 25.4, 164.6 ) | 60.9 ( 25, 129.7 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.189 | 0.086 | 0.299 | 0.091 |

| Trahana (g/day) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0.7 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 2.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.220 | 0.166 | 0.711 | <0.001 |

| Total Fermented cereals (g/day) | 77.1 ( 27.3, 169.3 ) | 44 ( 16.2, 111.3 ) | 71.3 ( 25, 164.3 ) | 65.2 ( 25.7, 133.9 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.140 | 0.061 | 0.311 | 0.191 |

| Milk chocolate (g/week) | 33 ( 6.6, 138.8 ) | 69.4 ( 16.5, 211.5 ) | 33 ( 6.6, 138.8 ) | 33 ( 6.6, 138.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.370 | 0.342 | 0.246 | <0.001 |

| Dark chocolate (g/week) | 16.5 ( 6.6, 69.4 ) | 16.5 ( 6.6, 69.4 ) | 69.4 ( 16.5, 208.2 ) | 16.5 ( 6.6,138.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.029 | 0.297 | 0.190 | 0.066 |

| White chocolate (g/week) | 6.6 ( 0, 13.2 ) | 6.6 ( 0, 16.5 ) | 6.6 ( 0, 6.6 ) | 0 ( 0, 6.6 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.411 | 0.282 | 0.208 | 0.564 |

| Total Chocolate (g/week) | 76 ( 33, 211.5 ) | 138.8 ( 39.7, 422.9 ) | 138.8 ( 46.3, 330.4 ) | 82.6 ( 33, 257.7 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.804 | 0.150 | 0.730 | 0.089 |

| Kombucha (ml/week) | 12.5 ( 0, 31.2 ) | 0 ( 0, 24.9 ) | 24.9 ( 12.5, 62.3 ) | 8.3 ( 0, 31.2 ) | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.925 | 0.158 | 0.048 | 0.925 |

| Cereal drinks (i.e., Amazake) (ml/week) | 24.9 ( 0, 62.3 ) | 12.5 ( 0, 24.9 ) | 0 ( 0, 8.3 ) | 0 ( 0, 12.5 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.253 | 0.003 | 0.042 | 0.512 |

| Water kefir (ml/week) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 8.3 ) | 0 ( 0, 24.9 ) | 0 ( 0, 8.3 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.645 | 0.694 | 0.031 | 0.258 |

| Total Fermented non-alcoholic beverages (ml/week) | 33.2 ( 20.8, 87.2 ) | 24.9 ( 8.3, 62.3 ) | 49.8 ( 24.9, 130.8 ) | 18.7 ( 0, 62.3 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.871 | 0.708 | 0.002 | 0.616 |

| Apple vinegar (g/day) | 0.3 ( 0.1, 1 ) | 0.7 ( 0.1, 3.2 ) | 0.3 ( 0.1, 1.5 ) | 0.3 ( 0.1, 1 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.246 | 0.085 | 0.537 | 0.054 |

| Grape vinegar (g/day) | 0.1 ( 0, 0.3 ) | 0.1 ( 0, 1 ) | 0.3 ( 0, 1 ) | 0.3 ( 0.1, 1.5 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.814 | 0.084 | 0.411 | 0.250 |

| Balsamic vinegar (g/day) | 0.3 ( 0.1, 0.74 ) | 0.1 ( 0, 1 ) | 1 ( 0.3, 3.2 ) | 0.3 ( 0.1, 3.1 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.214 | 0.116 | 0.040 | 0.580 |

| Other vinegar (g/day) | 0.1 ( 0, 0.3 ) | 0 ( 0, 0.3 ) | 0.1 ( 0, 0.6 ) | 0 ( 0, 0.1 ) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.923 | 0.366 | 0.322 | 0.213 |

| Total Vinegar-all types (g/day) | 0.7 ( 0.3, 3.1 ) | 2.3 ( 0.4, 9.5 ) | 3.5 ( 1, 9.9 ) | 2.1 ( 0.5, 6.3 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.135 | 0.312 | 0.171 | 0.085 |

| Espresso coffee (ml/day) | 1.2 ( 0, 31.5 ) | 12.8 ( 1.2, 38.4 ) | 19.2 ( 0.6, 60 ) | 12.6 ( 0, 60 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.171 | 0.58 | 0.002 |

| Arabic coffee (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 1.2 ) | 6.3 ( 0, 60 ) | 0 ( 0, 0.6 ) | 1.2 ( 0, 12.6 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.170 | 0.005 | 0.373 | 0.038 |

| Filter coffee (ml/day) | 49.8 ( 2.4, 379.2 ) | 0 ( 0, 4.7 ) | 4.7 ( 0, 151.7 ) | 2.4 ( 0, 49.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.014 | 0.228 |

| Instant coffee (ml/day) | 1.6 ( 0, 11.9 ) | 4.7 ( 0, 75.8 ) | 0 ( 0, 4.7 ) | 4.7 ( 0, 49.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.160 | 0.069 | 0.884 | 0.302 |

| Total Coffee (ml/day) | 73.1 ( 12.6, 241.7 ) | 60 ( 20, 150 ) | 65.9 ( 29.6, 240 ) | 60 ( 13.8, 156.2 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.388 | 0.008 | 0.079 | 0.018 |

| Puer tea (ml/day) | 4.7 ( 0, 24.9 ) | 0 ( 0, 11.9 ) | 0 ( 0, 4.7 ) | 11.9 ( 0, 237 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.969 | 0.592 | 0.833 | <0.001 |

| Anhui tea (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0.423 | 0.804 | 0.145 | 0.461 | 0.343 | 0.094 |

| Guangxi tea (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0.009 | 0.124 | <0.001 | 0.372 | 0.442 | 0.788 |

| Hubei tea (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 2.4 ) | 0 ( 0, 2.4 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0.015 | 0.101 | 0.032 | 0.246 | 0.818 | 0.431 |

| Fuzhuan tea (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0.382 | 0.602 | 0.020 | 0.340 | 0.940 | 0.127 |

| Sichuan tea (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 4.7 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.067 | 0.289 | 0.518 | 0.122 |

| Total Fermented Tea (ml/day) | 9.5 ( 1.6, 39.3 ) | 2.4 ( 0, 21.3 ) | 0 ( 0, 14.2 ) | 16.59 ( 0, 237 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.298 | 0.506 | 0.843 | <0.001 |

| Sweetened cocoa beverages (ml/week) | 33.2 ( 33.2, 83 ) | 33.2 ( 16.6, 83 ) | 33.2 ( 33.2, 83 ) | 33.2 ( 16.6, 83 ) | 0.511 | 0.662 | 0.729 | 0.046 | 0.261 | 0.236 |

| Unsweetened cocoa beverages (ml/week) | 33.2 ( 0, 33.2 ) | 33.2 ( 0, 41.5 ) | 16.6 ( 0, 33.2 ) | 33.2 ( 0, 83 ) | 0.053 | 0.092 | 0.103 | 0.993 | 0.164 | 0.888 |

| Total Cocoa beverages (ml/week) | 66.4 ( 33.2, 116.1 ) | 66.4 ( 33.2, 174.2 ) | 66.4 ( 33.2, 116.1 ) | 66.4 ( 33.2, 165.9 ) | 0.508 | 0.439 | 0.444 | 0.099 | 0.076 | 0.454 |

| Beer (ml/day) | 16.5 ( 6.6, 69.3 ) | 16.5 ( 6.6, 69.3 ) | 25 ( 10, 105 ) | 23.1 (8.25, 69.3 ) | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.070 | 0.054 | 0.139 |

| Alcohol-free beer (ml/day) | 6.6 ( 0, 16.5 ) | 0 ( 0, 6.6 ) | 5.67 ( 0, 16.5 ) | 0 ( 0, 6.6 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.041 | 0.540 | 0.004 | 0.338 |

| Cider (ml/day) | 10 ( 3.3, 25 ) | 3.3 ( 0, 10 ) | 10 ( 3.3, 16.5 ) | 0 ( 0, 10 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.230 | 0.447 | 0.47 |

| Alcohol-free cider (ml/day) | 0 ( 0, 10 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | 0 ( 0, 0 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.096 | 0.046 | 0.235 | 0.832 |

| Total Beer or cider (ml/day) | 45 (16.5, 115.5 ) | 25 ( 10, 75.9 ) | 50 ( 23.1, 130 ) | 33 ( 16.5, 102.3 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.056 | 0.049 | 0.168 |

| White wine (ml/day) | 6.3 ( 2.5, 26.3 ) | 6.3 ( 2.5, 17.5 ) | 6.3 ( 2.5, 26.3 ) | 6.3 ( 2.5, 26.3 ) | 0.473 | 0.348 | 0.781 | 0.840 | 0.002 | 0.782 |

| Red wine (ml/day) | 6.3 ( 4.2, 26.3 ) | 6.3 ( 2.5, 12.5 ) | 12.5 ( 5, 31.3 ) | 6.3 ( 4.2, 31.3 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.427 | 0.054 | 0.030 | 0.830 |

| Rose wine (ml/day) | 5 ( 2.5, 12.5 ) | 2.5 ( 2.5, 6.3 ) | 5 ( 2.5, 6.3 ) | 5 ( 2.5, 12.5 ) | 0.066 | 0.099 | 0.876 | 0.033 | 0.156 | 0.270 |

| Alcohol free wine (ml/day) | 5 ( 2.5, 5 ) | 2.5 ( 1.7, 5 ) | 2.5 ( 2.5, 5 ) | 2.5 ( 0, 2.5 ) | 0.772 | 0.592 | 0.695 | 0.147 | 0.491 | 0.342 |

| Total Wine-all types (ml/day) | 18.8 ( 7.5, 52.5 ) | 12.5 ( 5.8, 31.3 ) | 25 ( 10.4, 61.3 ) | 18.8 ( 7.5, 55.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.704 | 0.446 | 0.002 | 0.708 |

| Strong spirits (ml/day) | 5.9 ( 2.4, 17.8 ) | 5.9 ( 2.4, 24.9 ) | 3.6 ( 2.4, 8.9 ) | 5.9 ( 2.4, 17.8 ) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.344 | 0.081 | 0.295 | 0.032 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).