Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

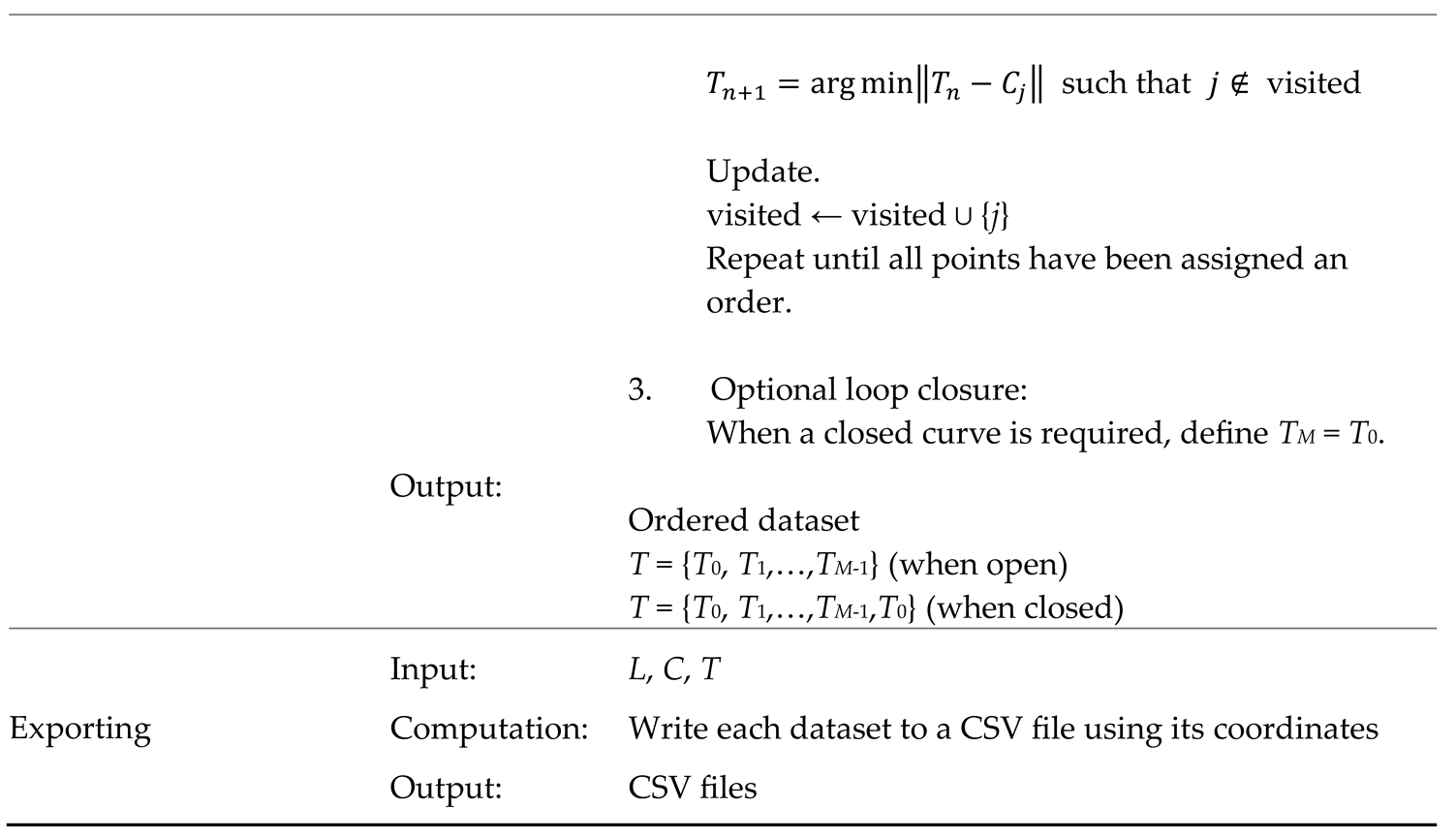

1. Introduction

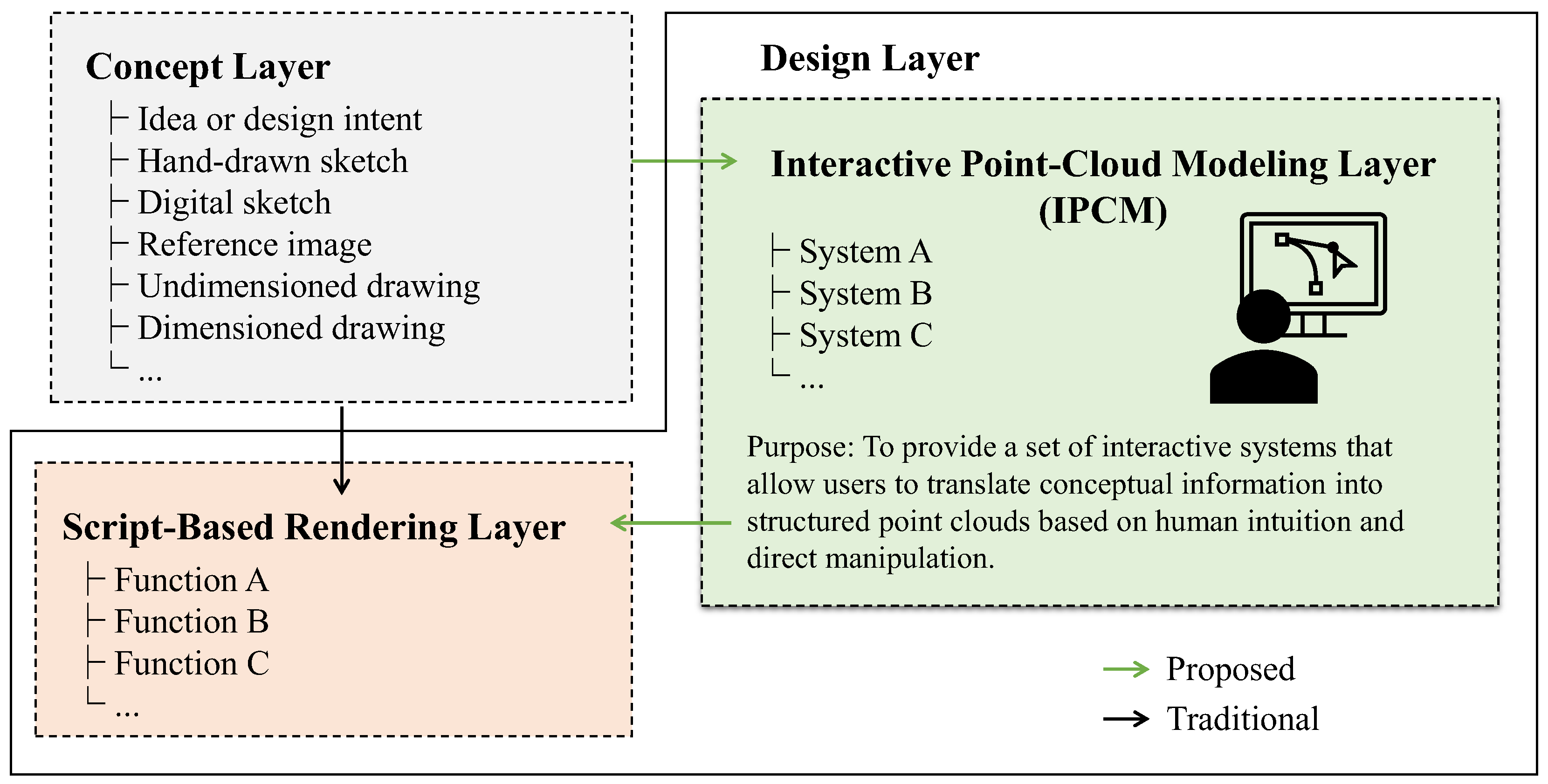

2. Proposed Framework

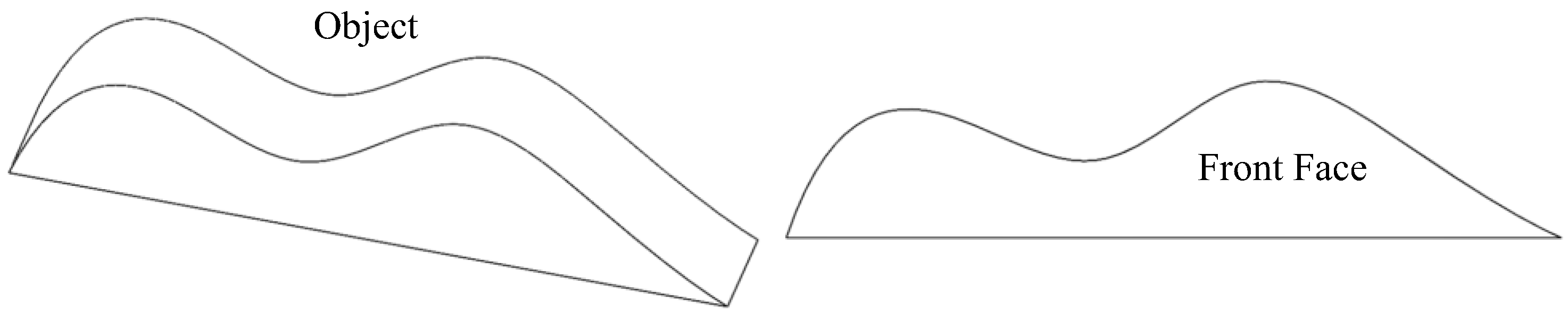

2.1. Problem Framing and Motivation

- parametric curves are essential for representing smooth or irregular boundaries,

- some environments provide native functions (e.g., splines in CQ) while others require user-implemented formulations,

- control-point coordinates must either be manually specified or mathematically deduced—both of which require users to understand how point placement influences the curve,

- developing or adapting the mathematical logic for parametric curves becomes increasingly demanding when irregularities increase, and

- number of steps grows substantially as the geometry becomes less regular.

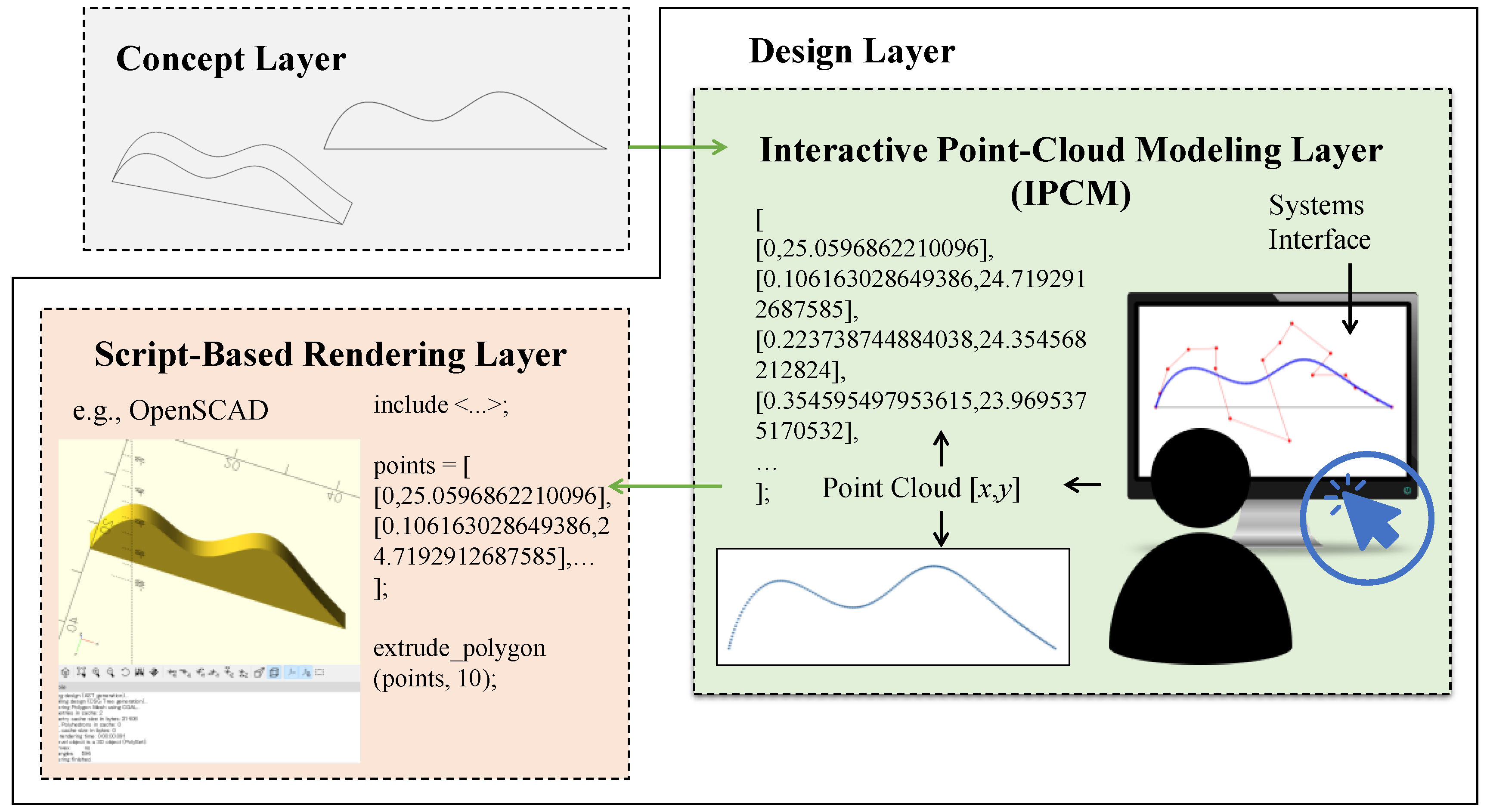

2.2. Conceptual Framework

3. Systems and Requirements

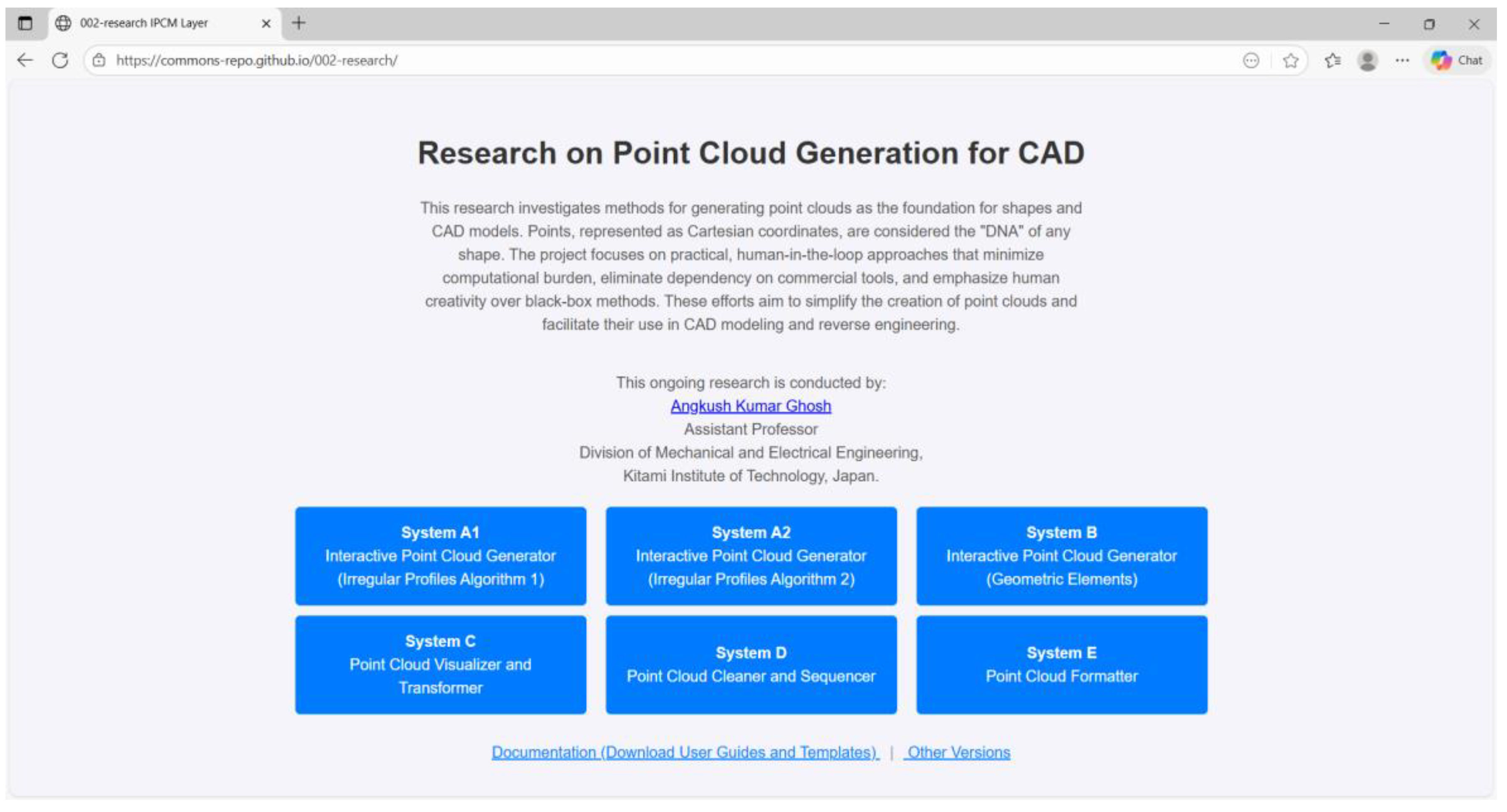

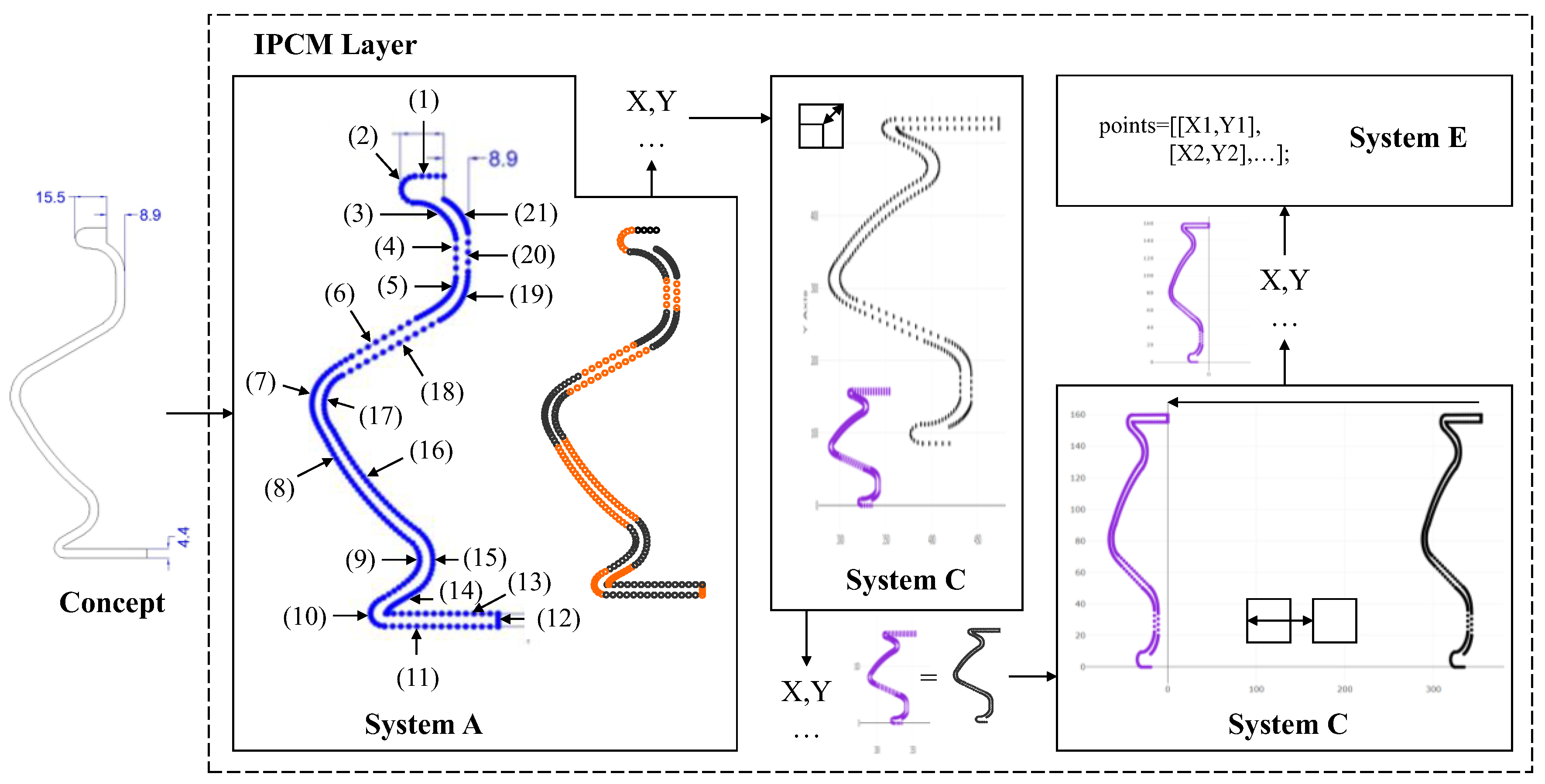

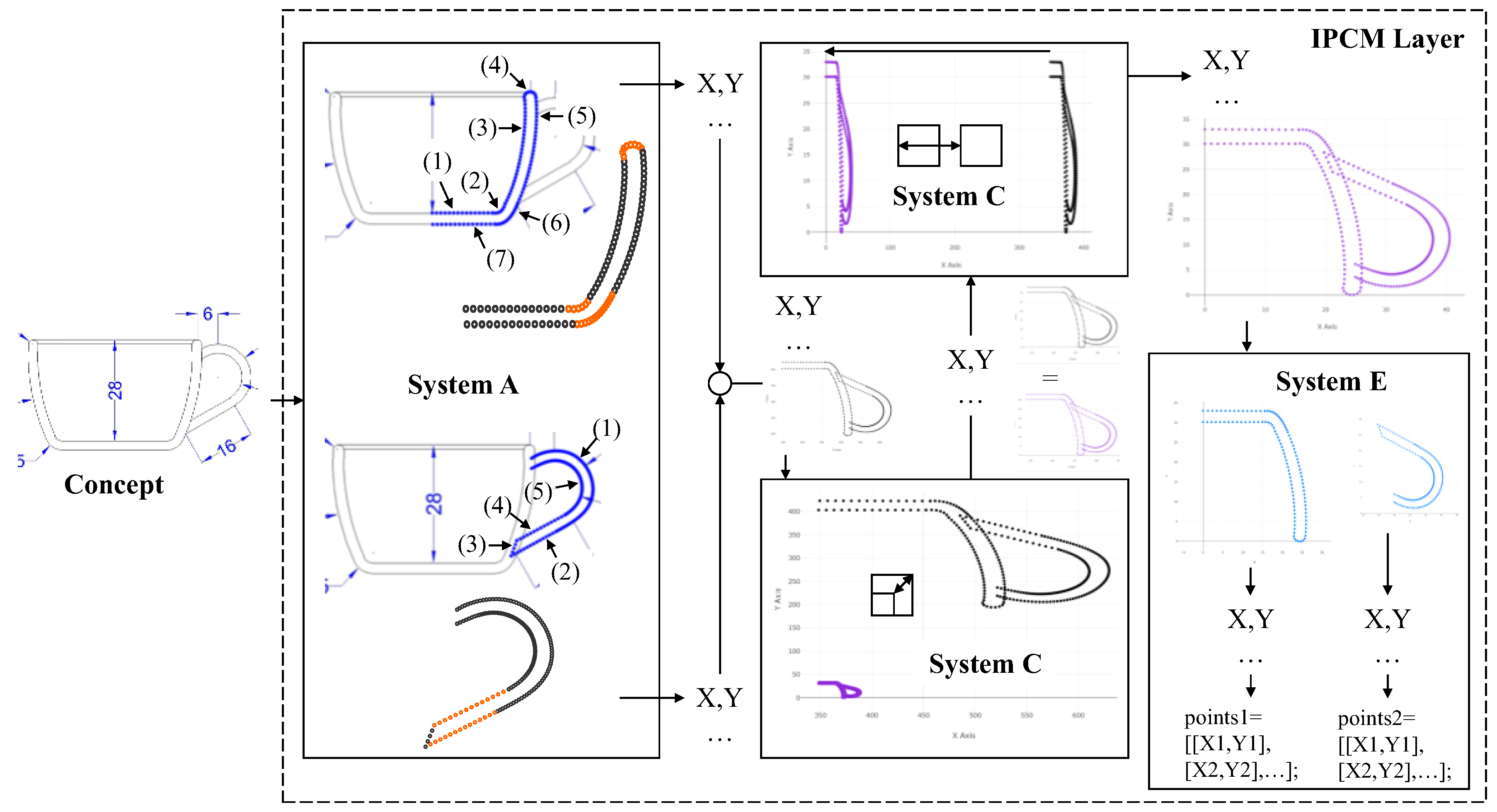

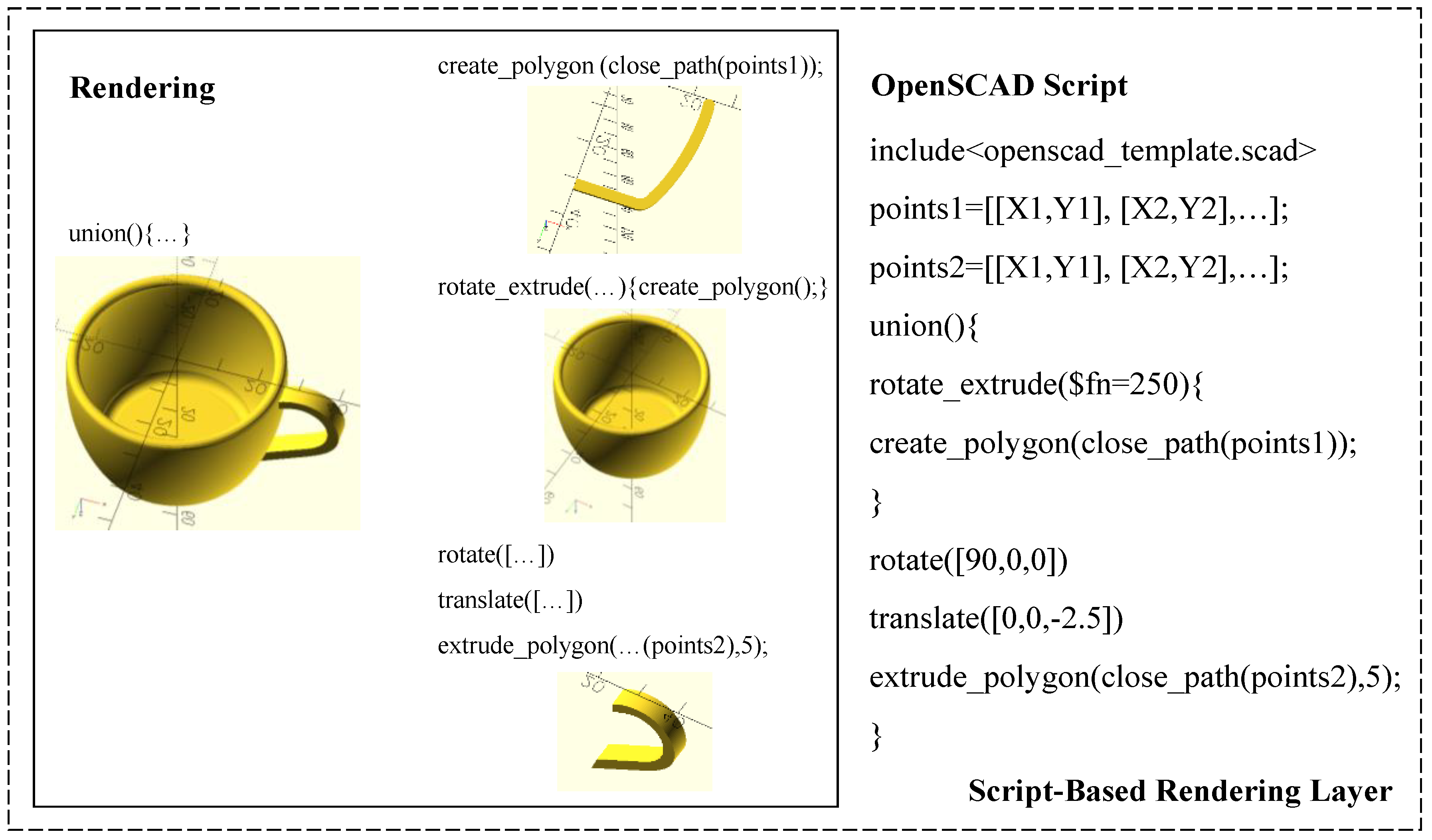

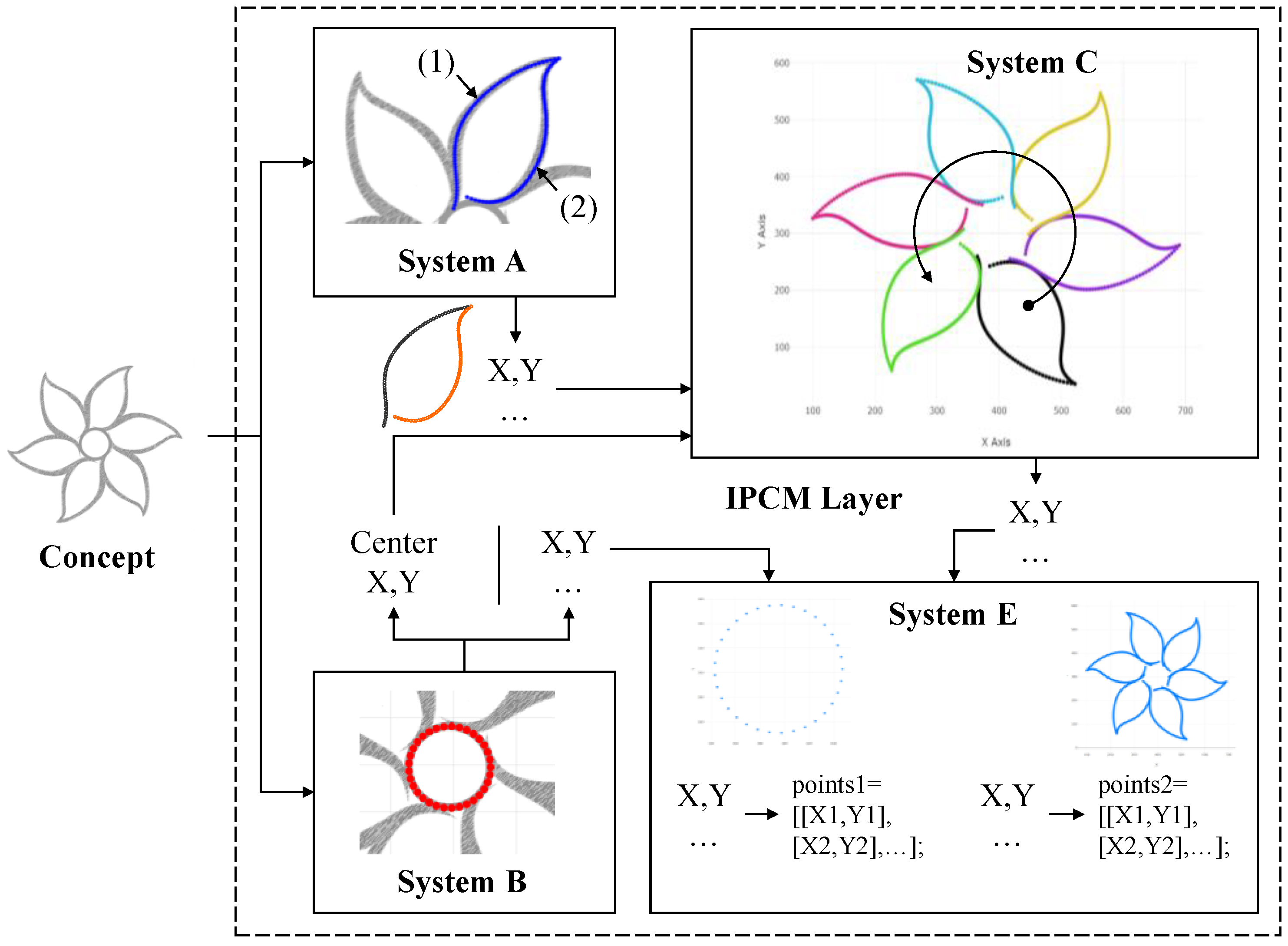

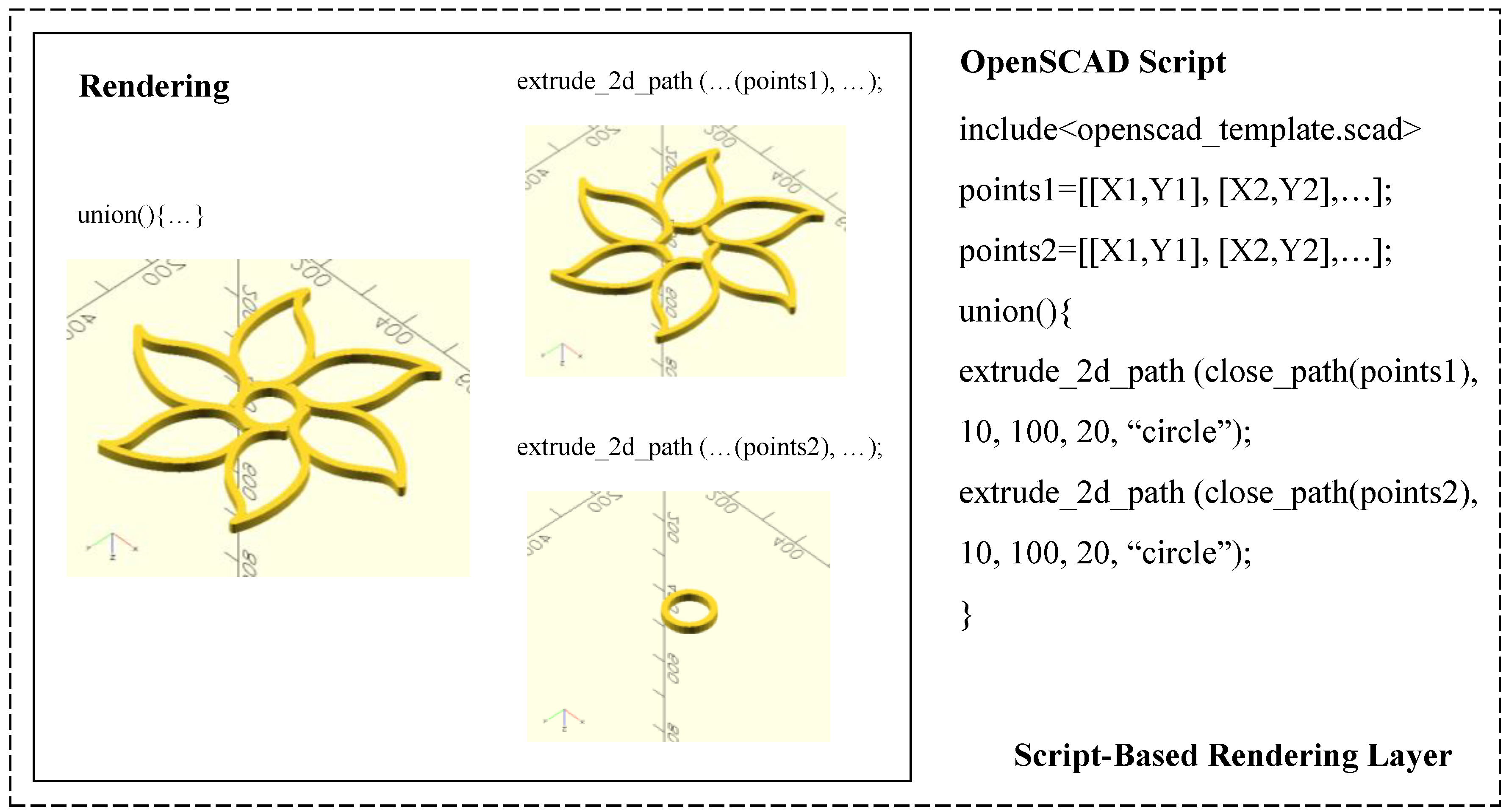

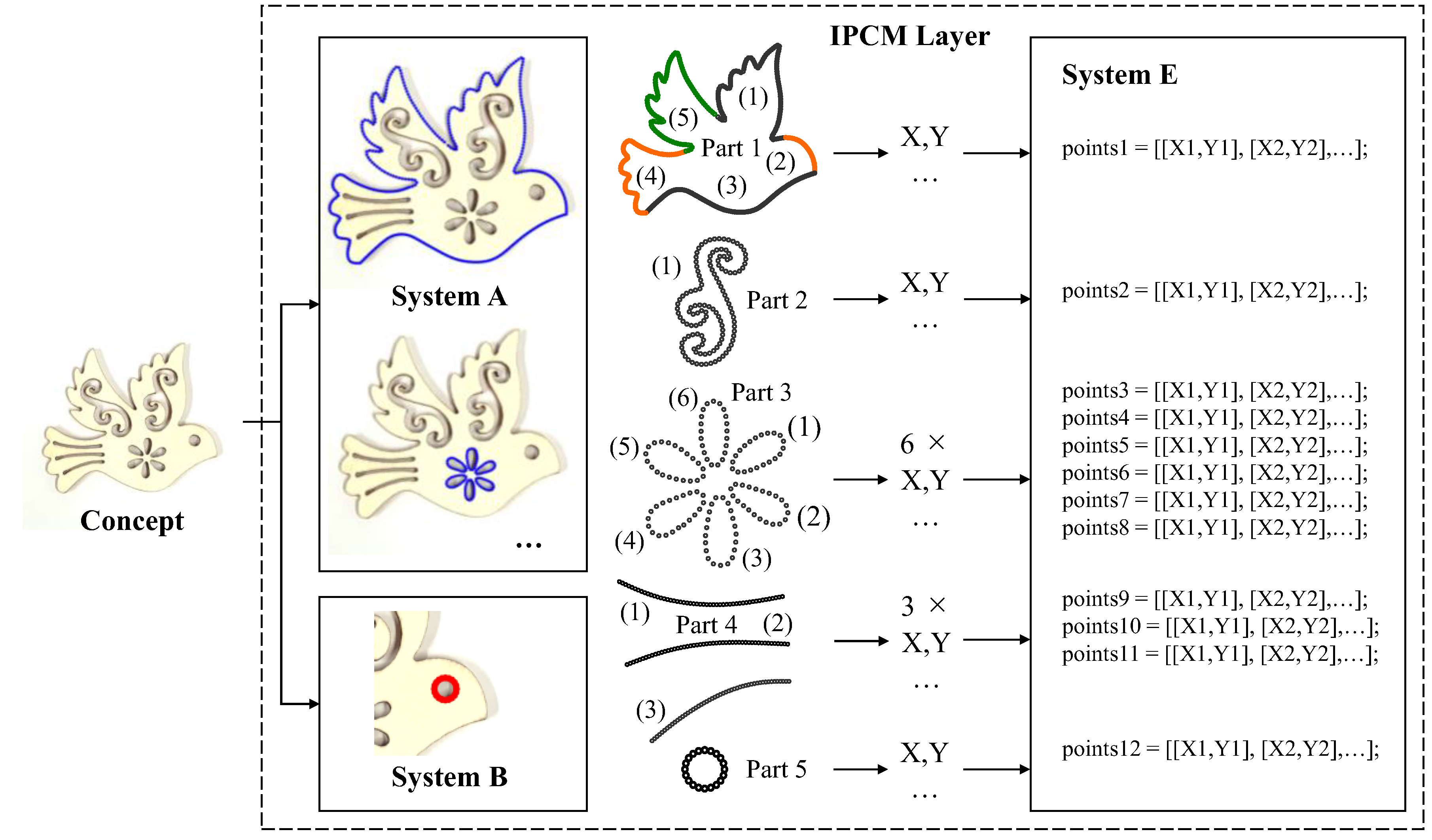

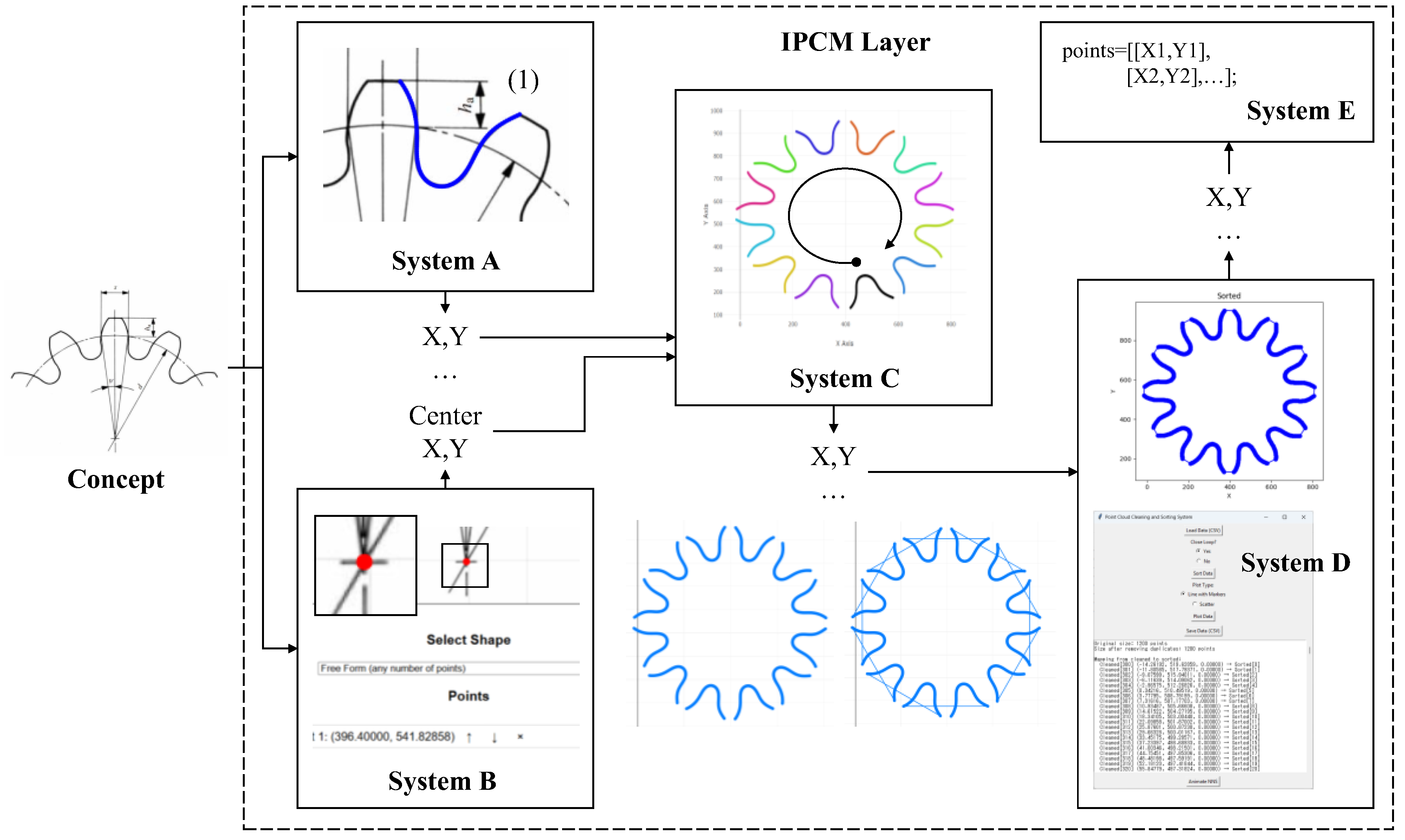

3.1. IPCM Layer

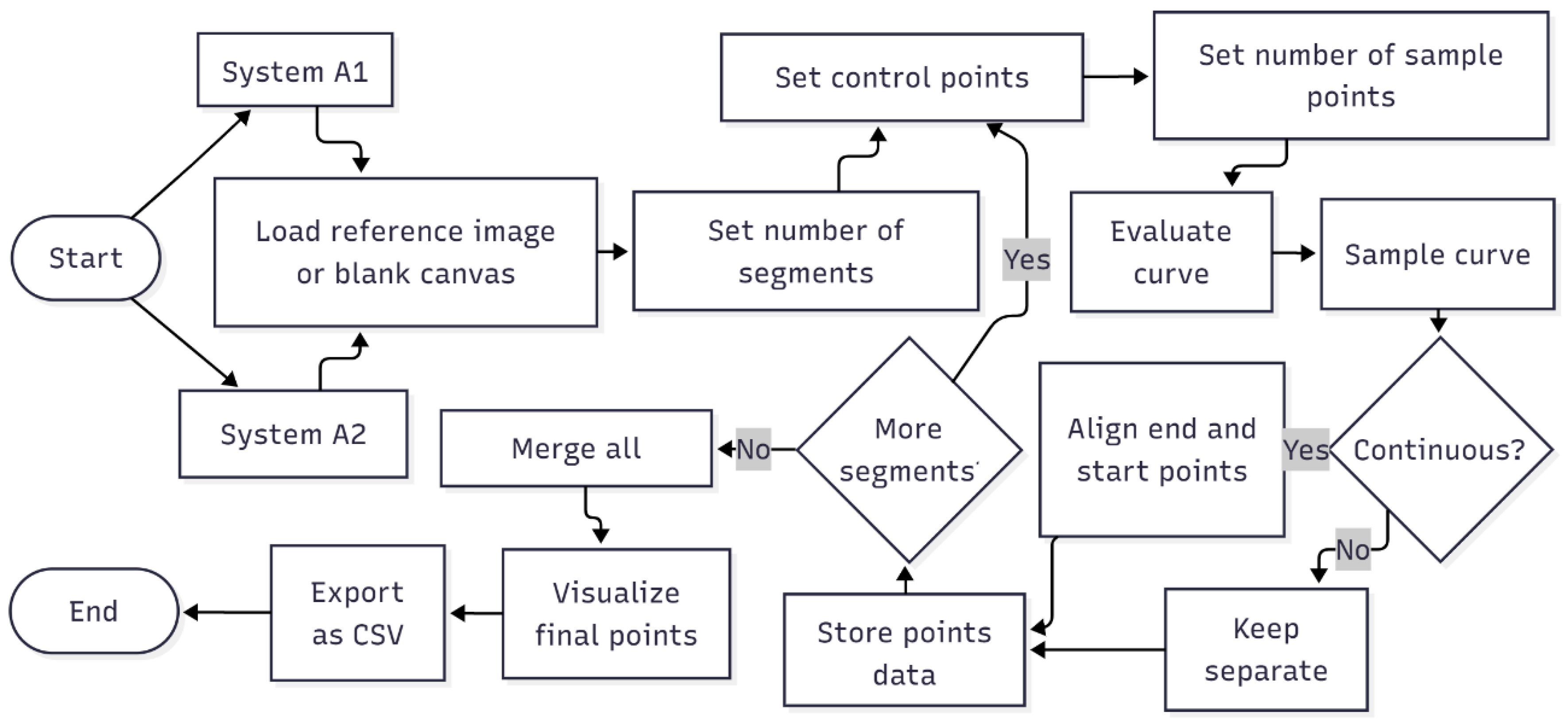

3.1.1. System A—Generating Point Cloud for Irregular Profiles

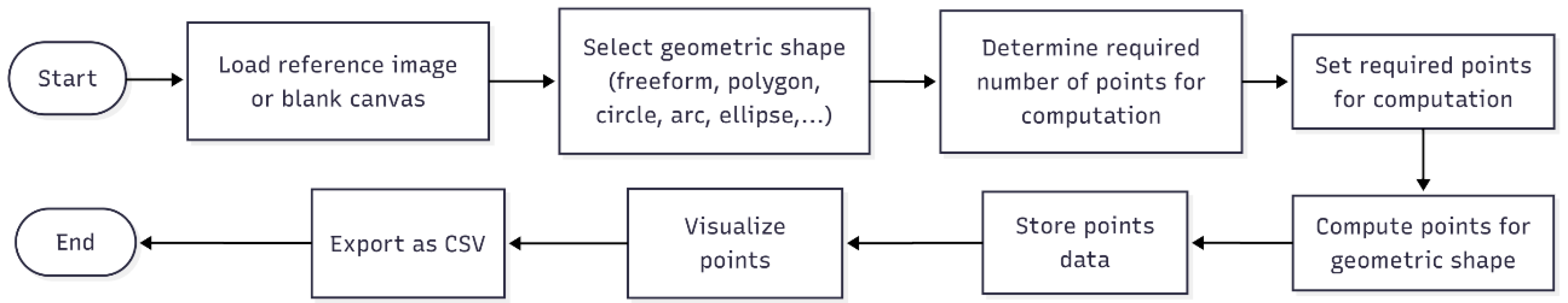

3.1.2. System B—Generating Point Cloud for Geometric Elements

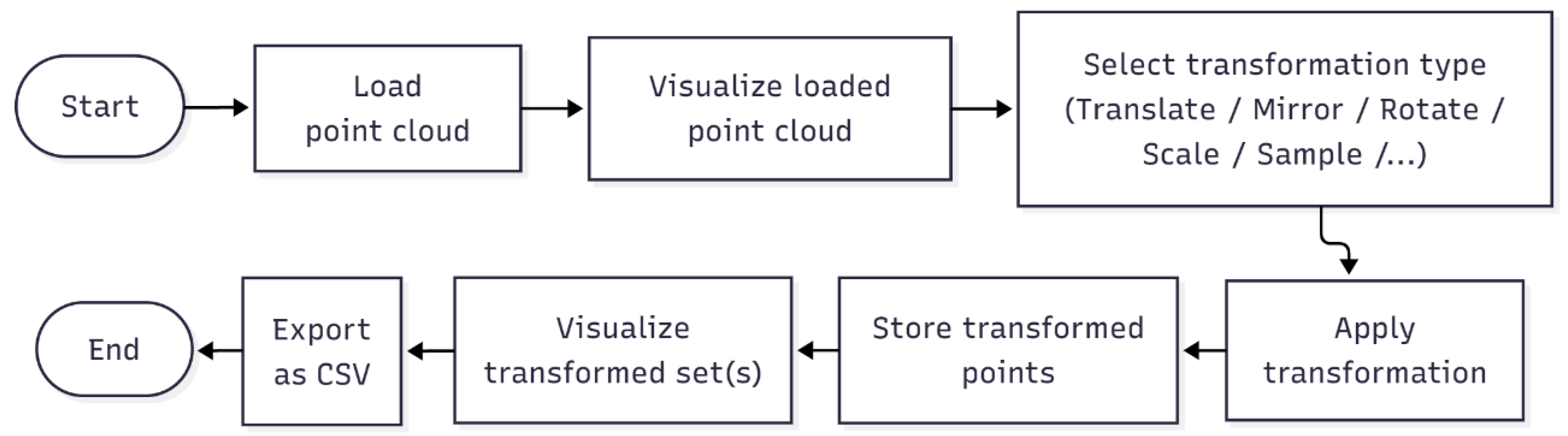

3.1.3. System C—Transforming Generated Point Clouds

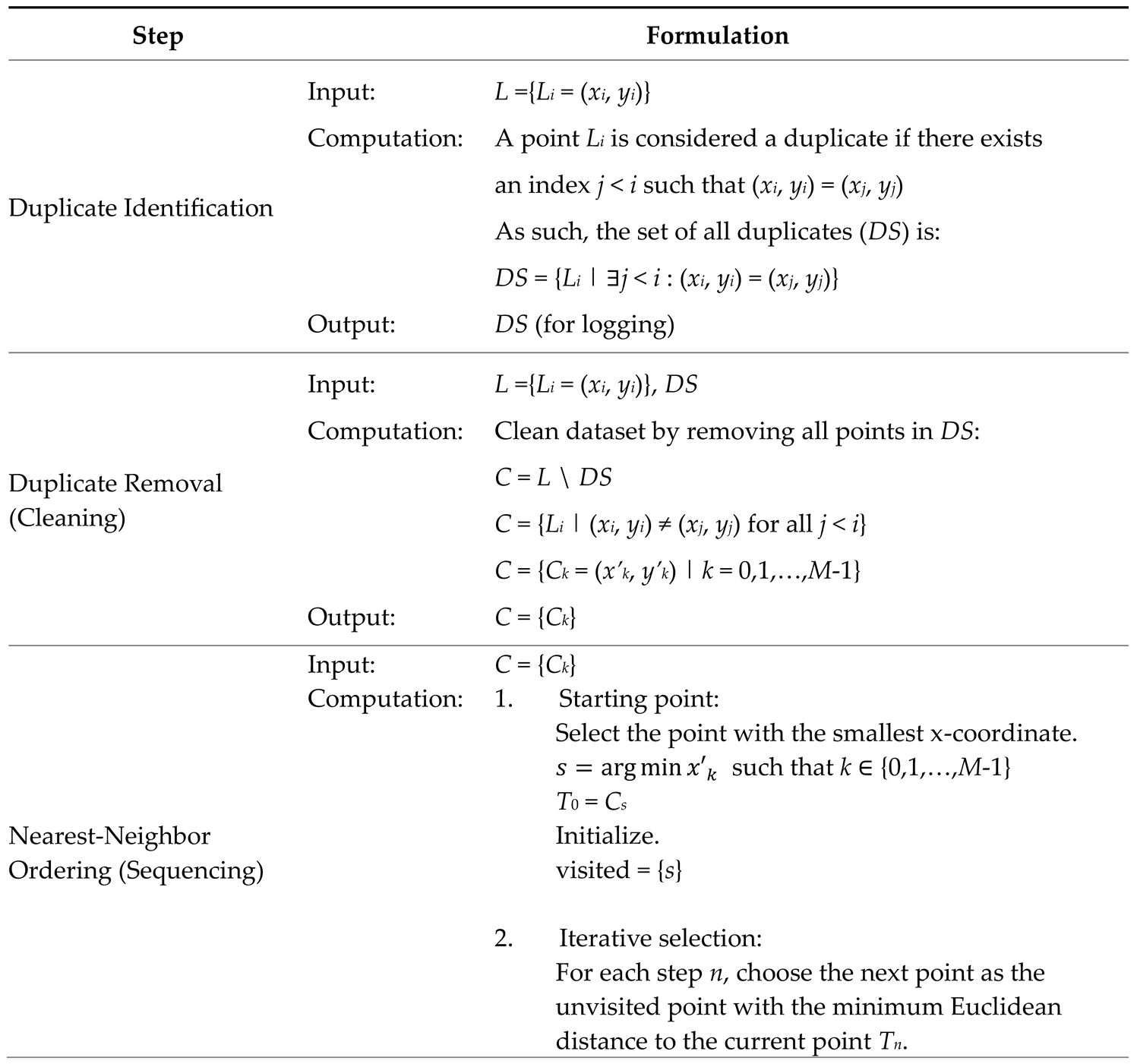

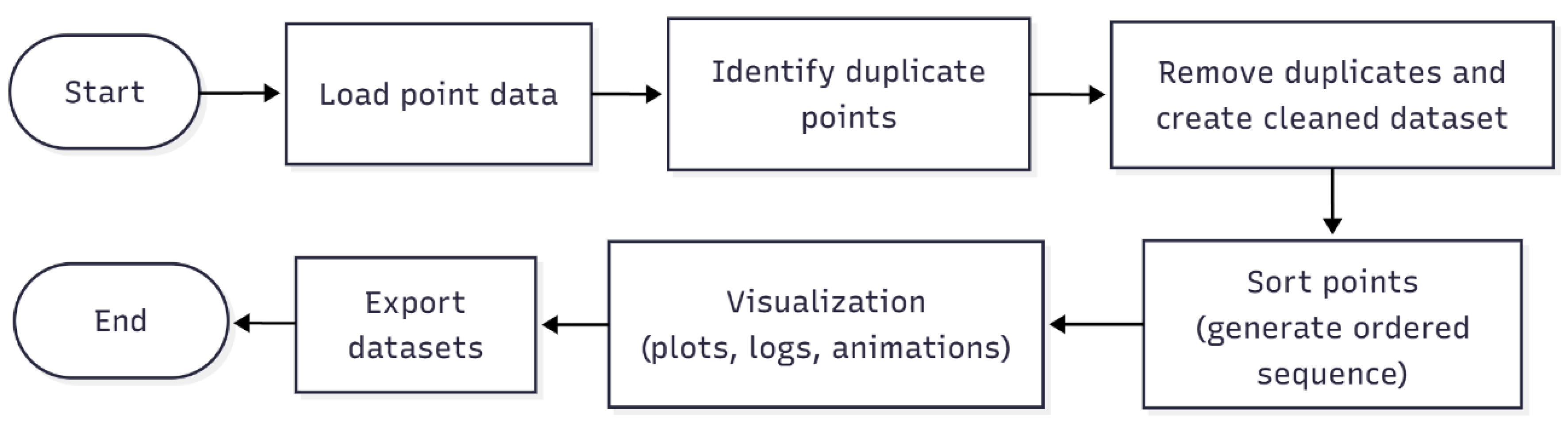

3.1.4. System D—Cleaning and Sequencing of Point Clouds

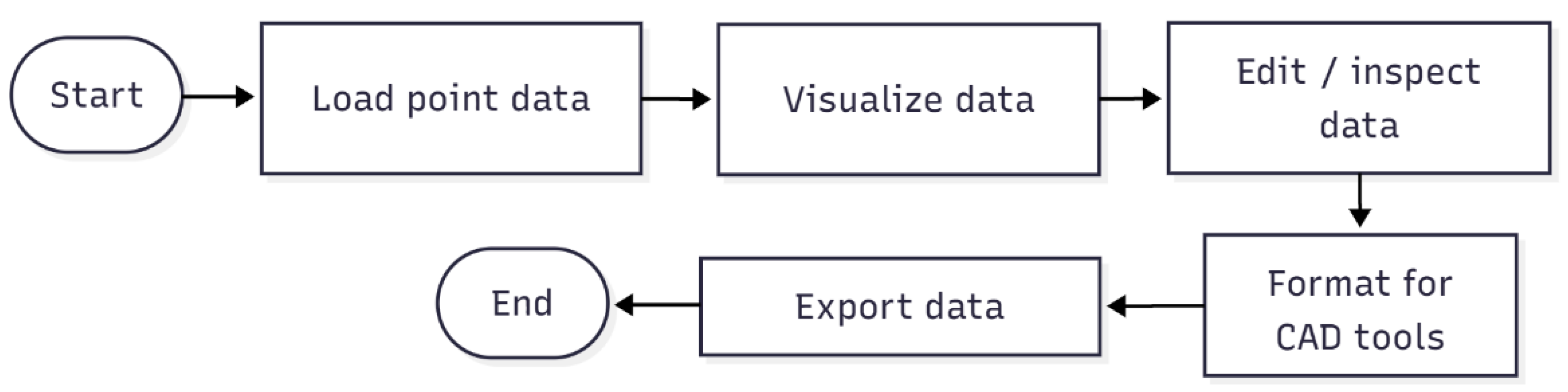

3.1.5. System E—Formatting of Point Clouds for Rendering Environments

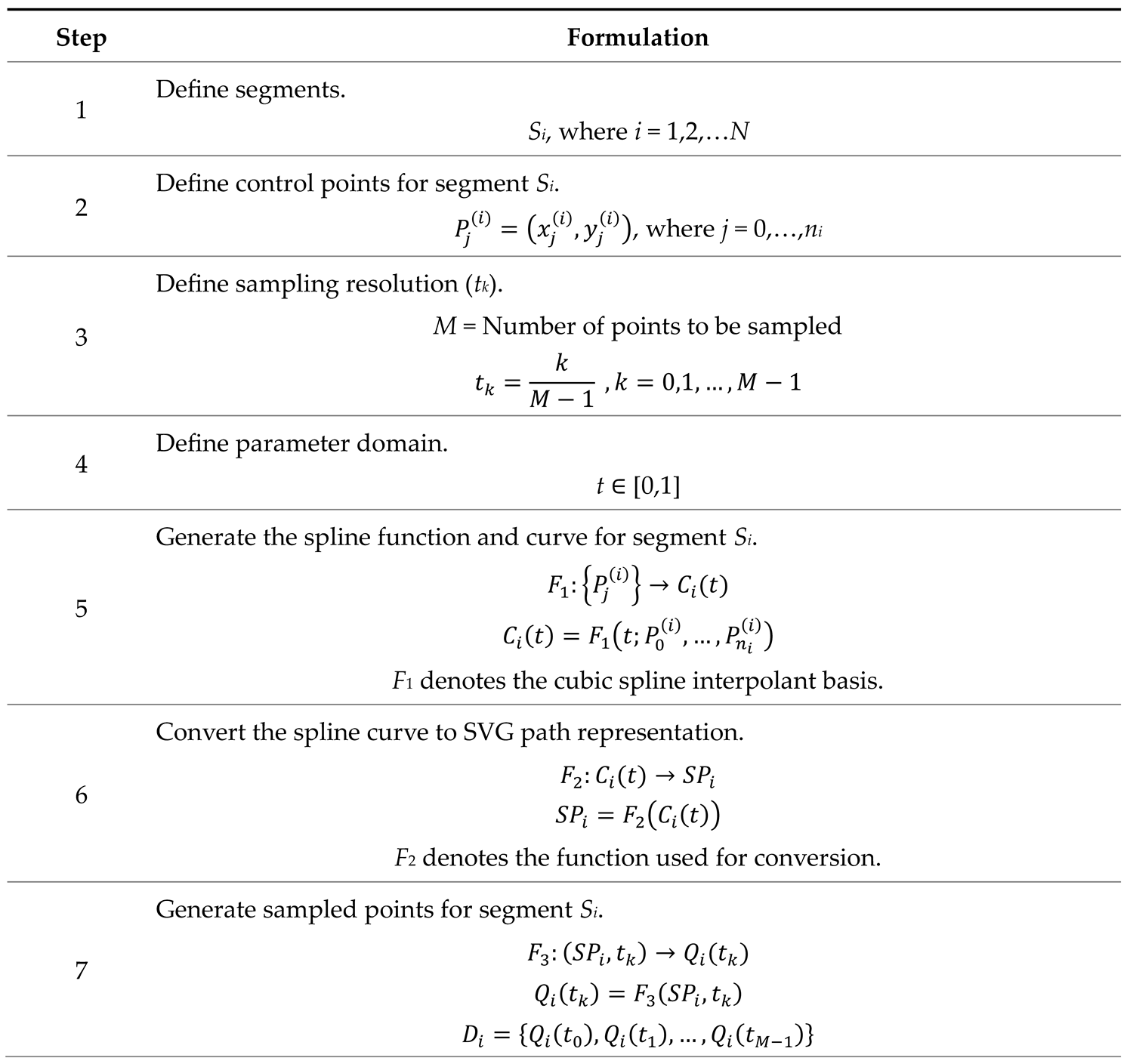

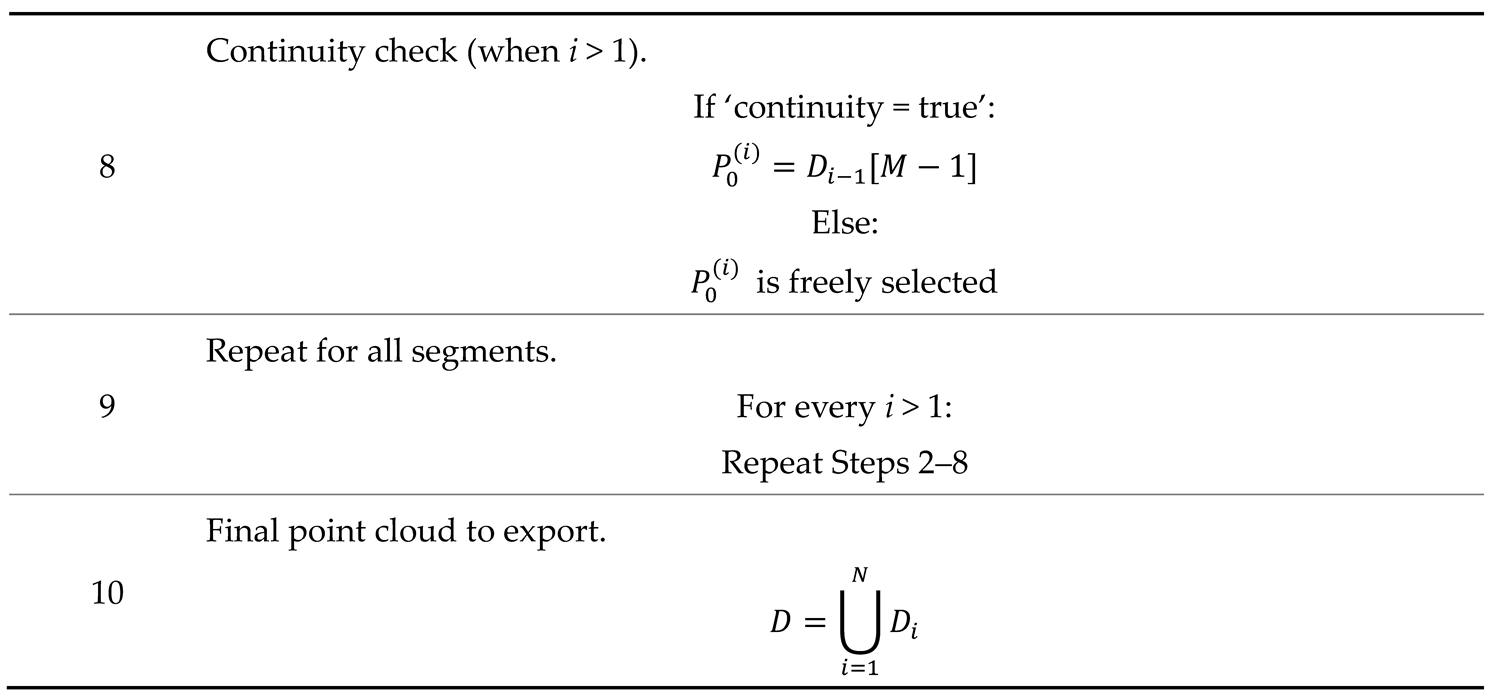

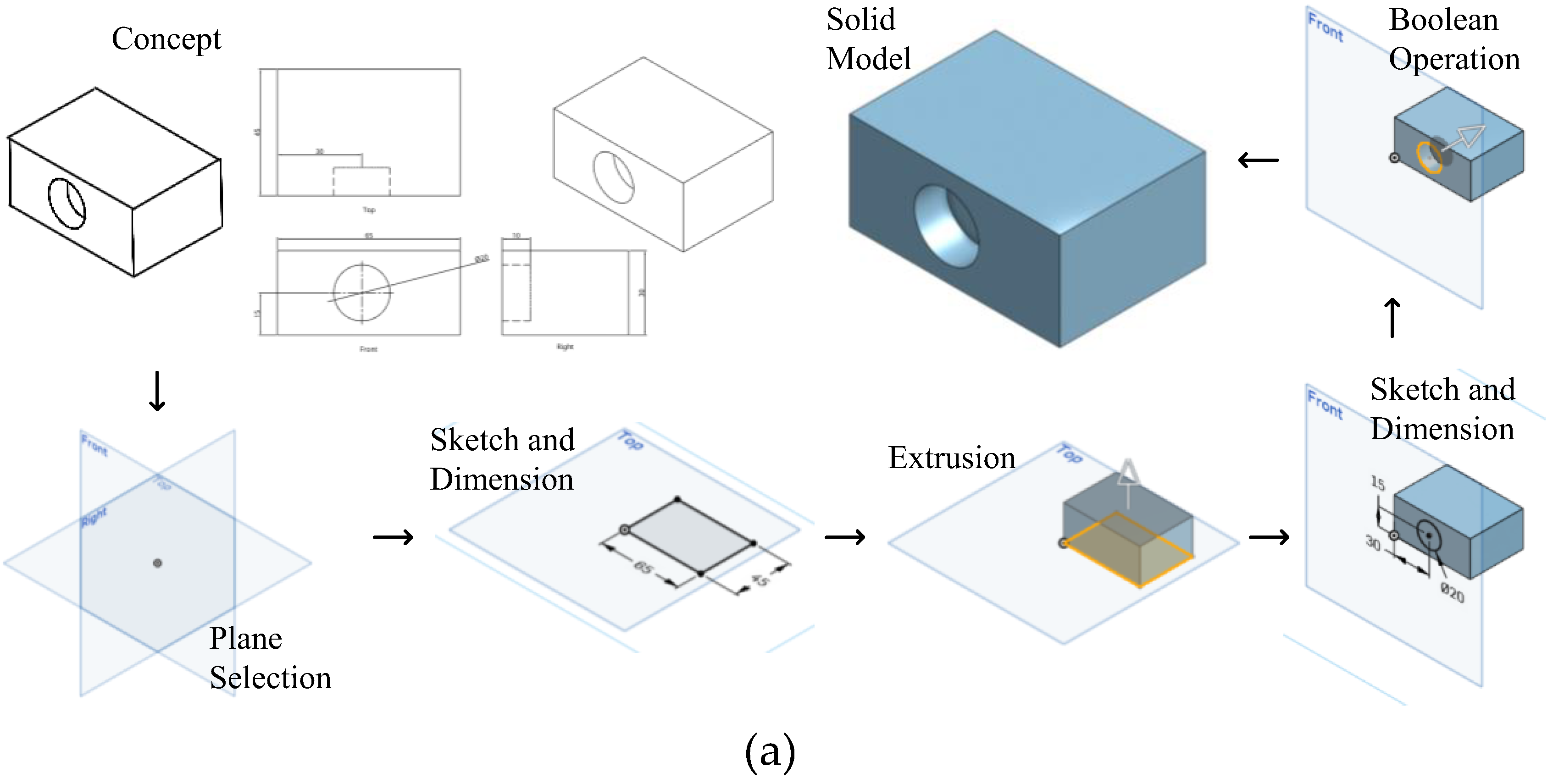

3.1.6. Systems Requirements

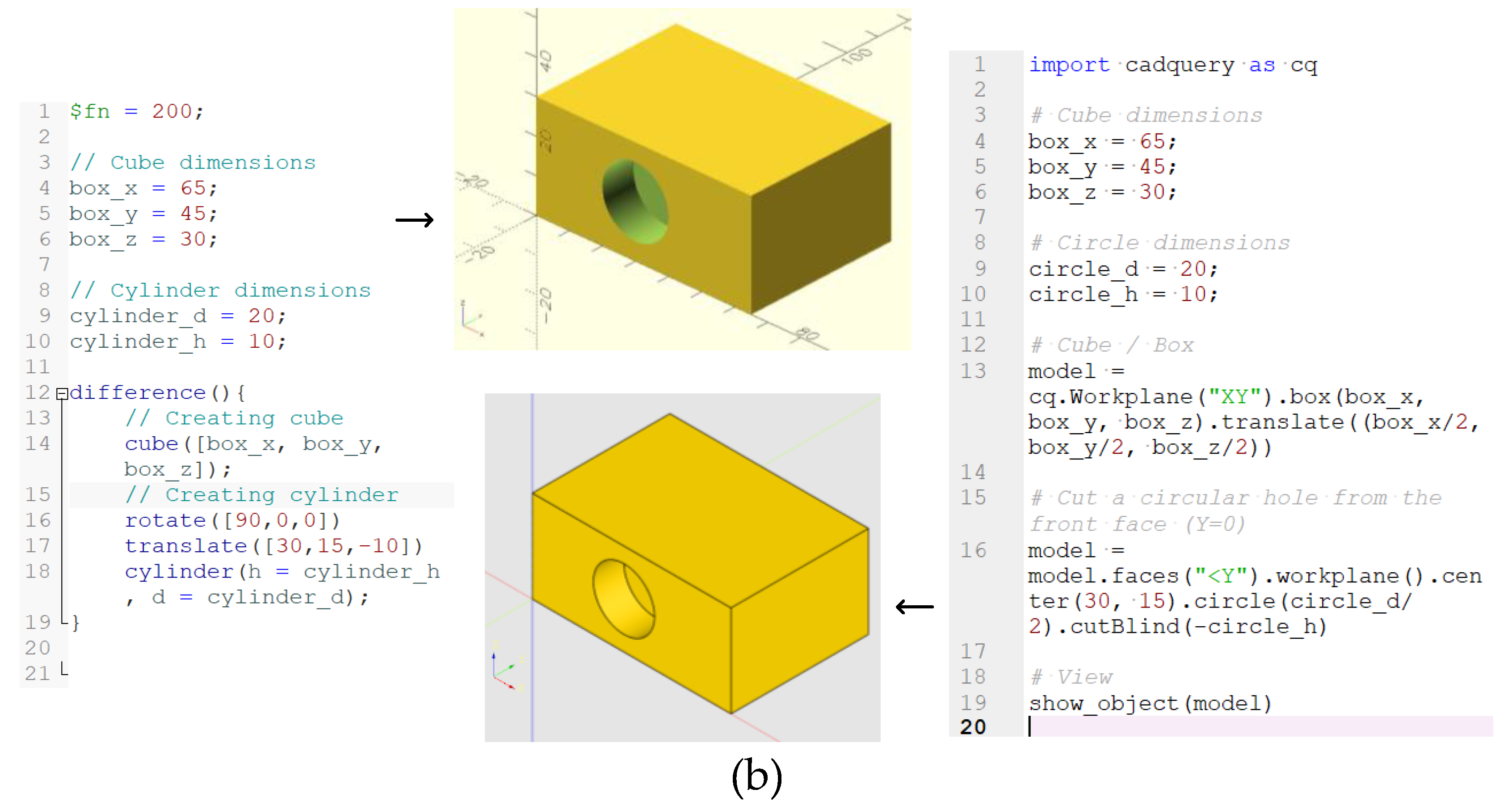

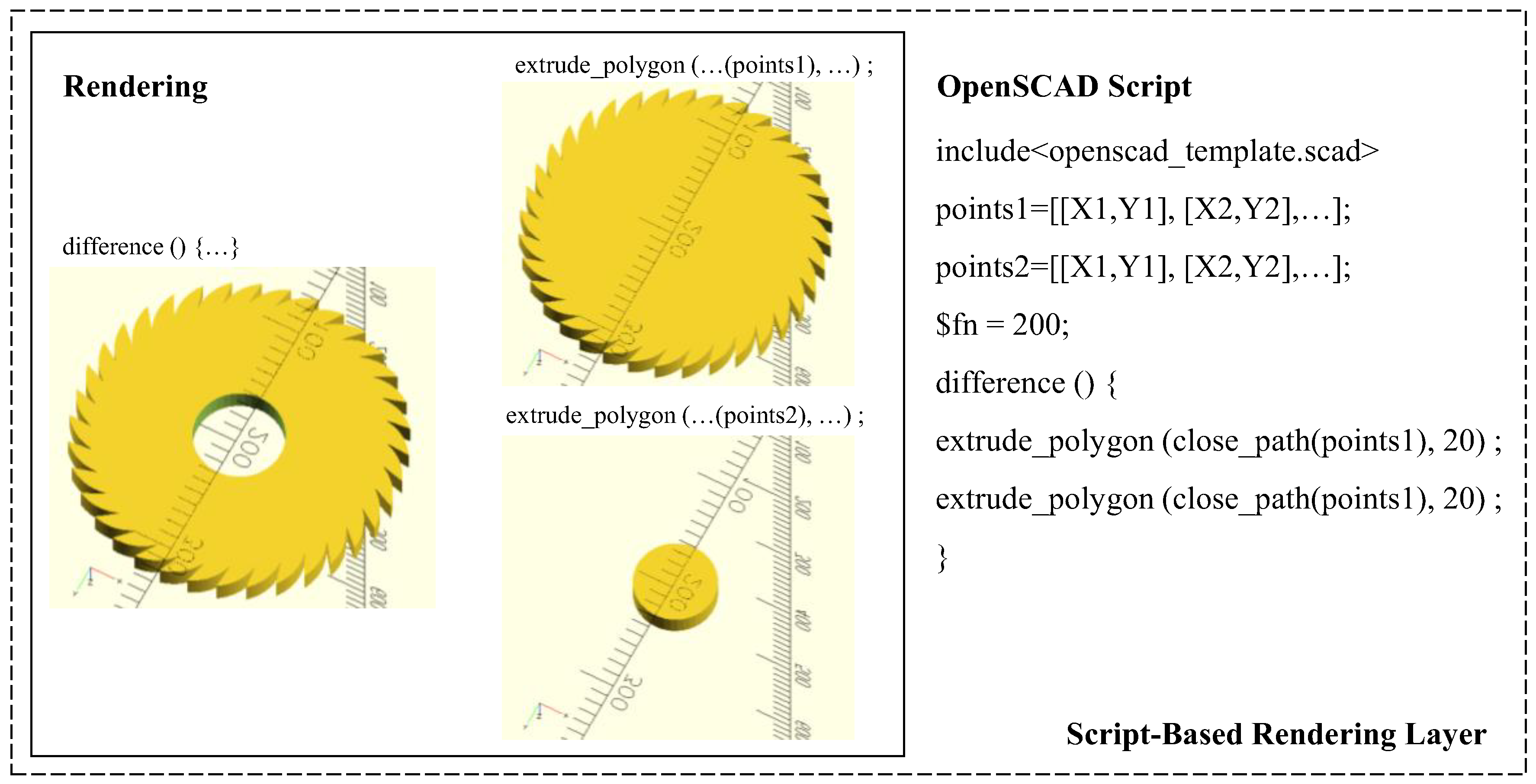

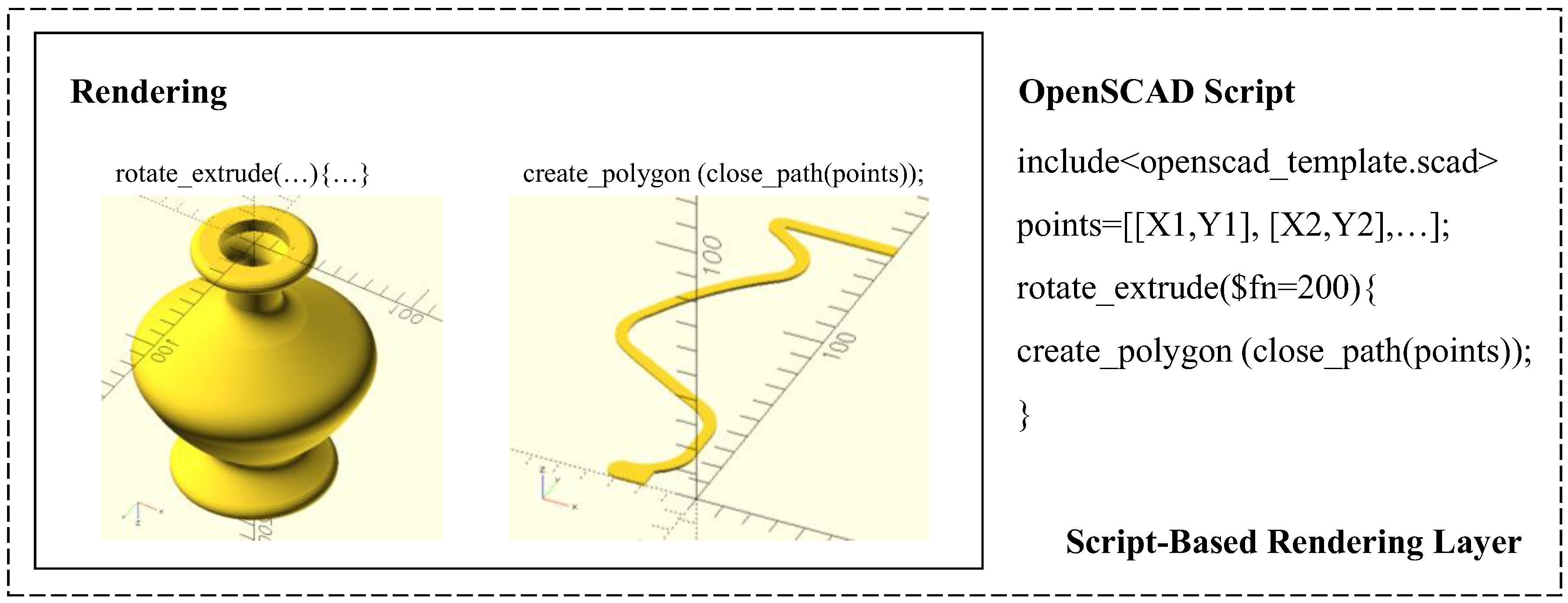

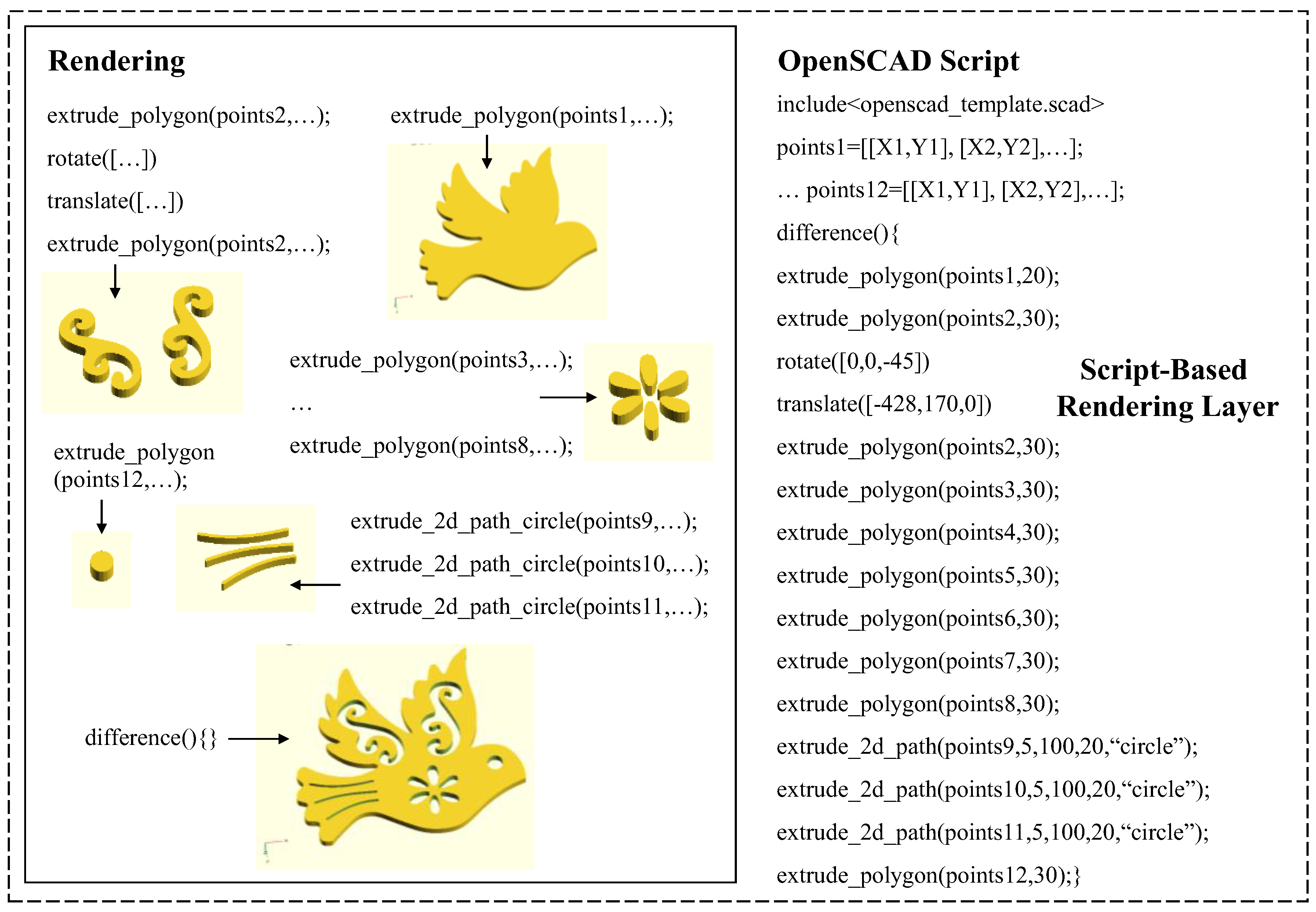

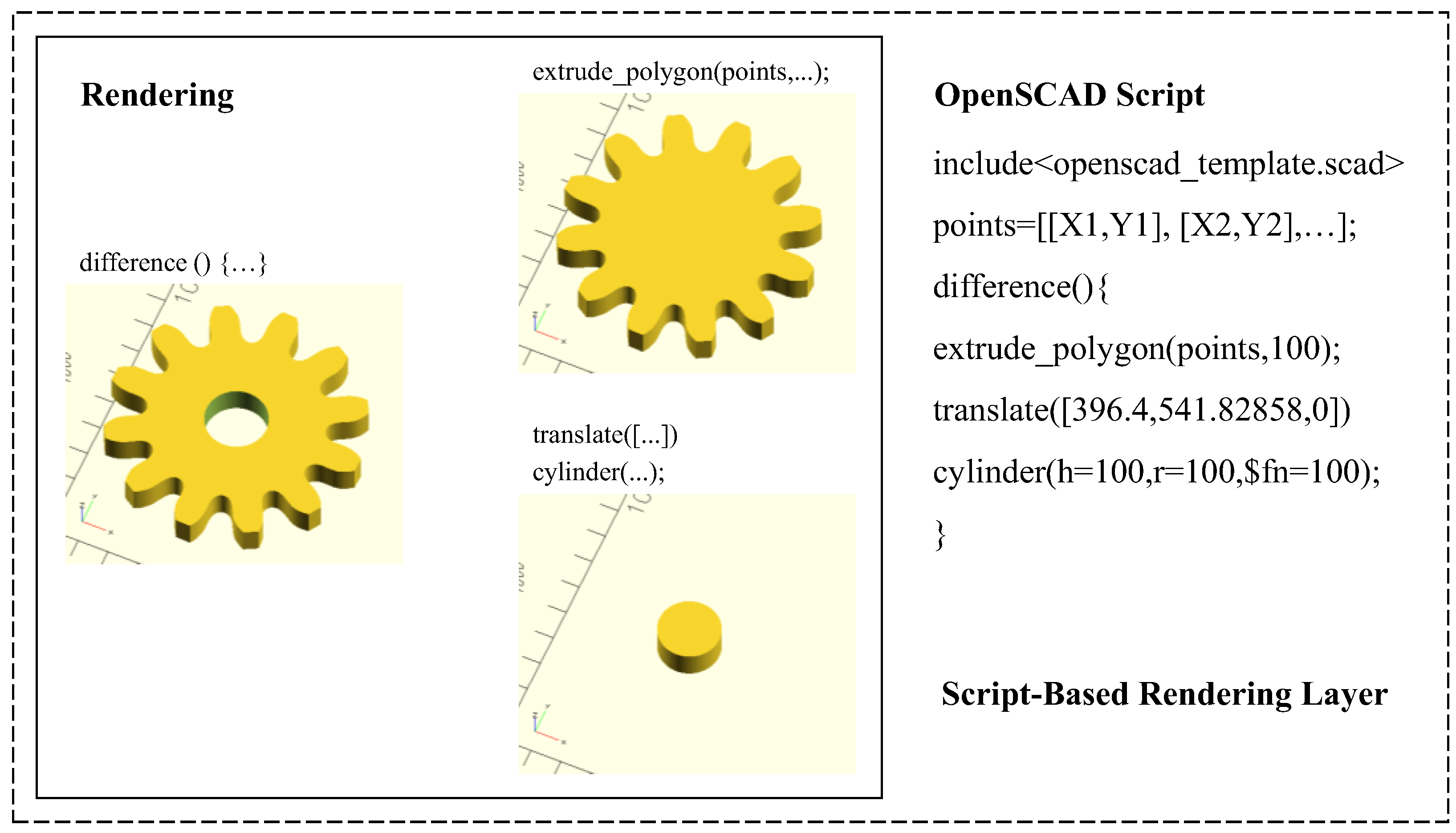

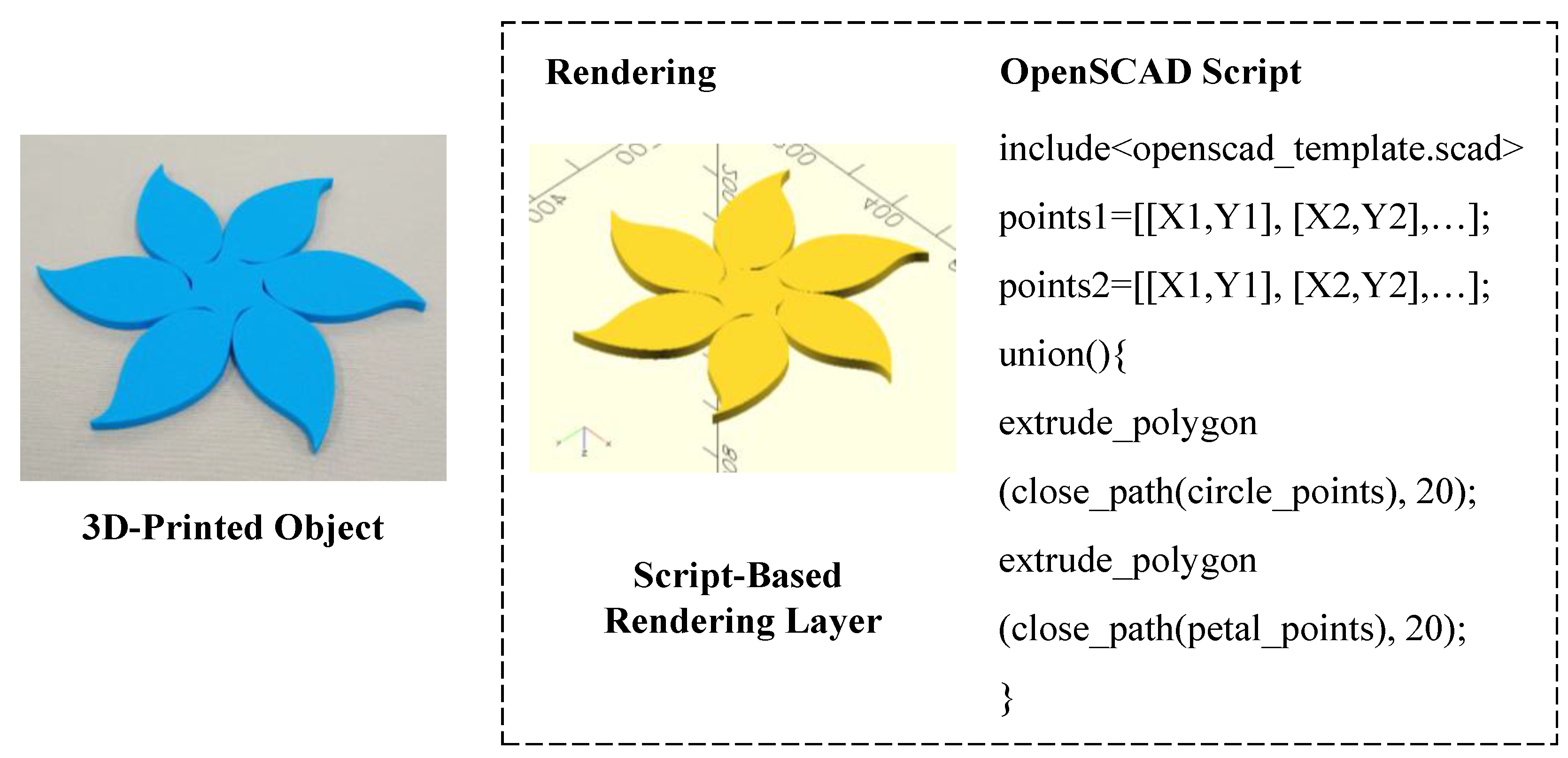

3.2. Script-Based Rendering Layer

4. Developing Systems and Functions

4.1. Developing Systems for IPCM Layer

4.1.1. System A—Generating Point Cloud for Irregular Profiles

4.1.2. System B—Generating Point Cloud for Geometric Elements

4.1.3. System C—Transforming Generated Point Clouds

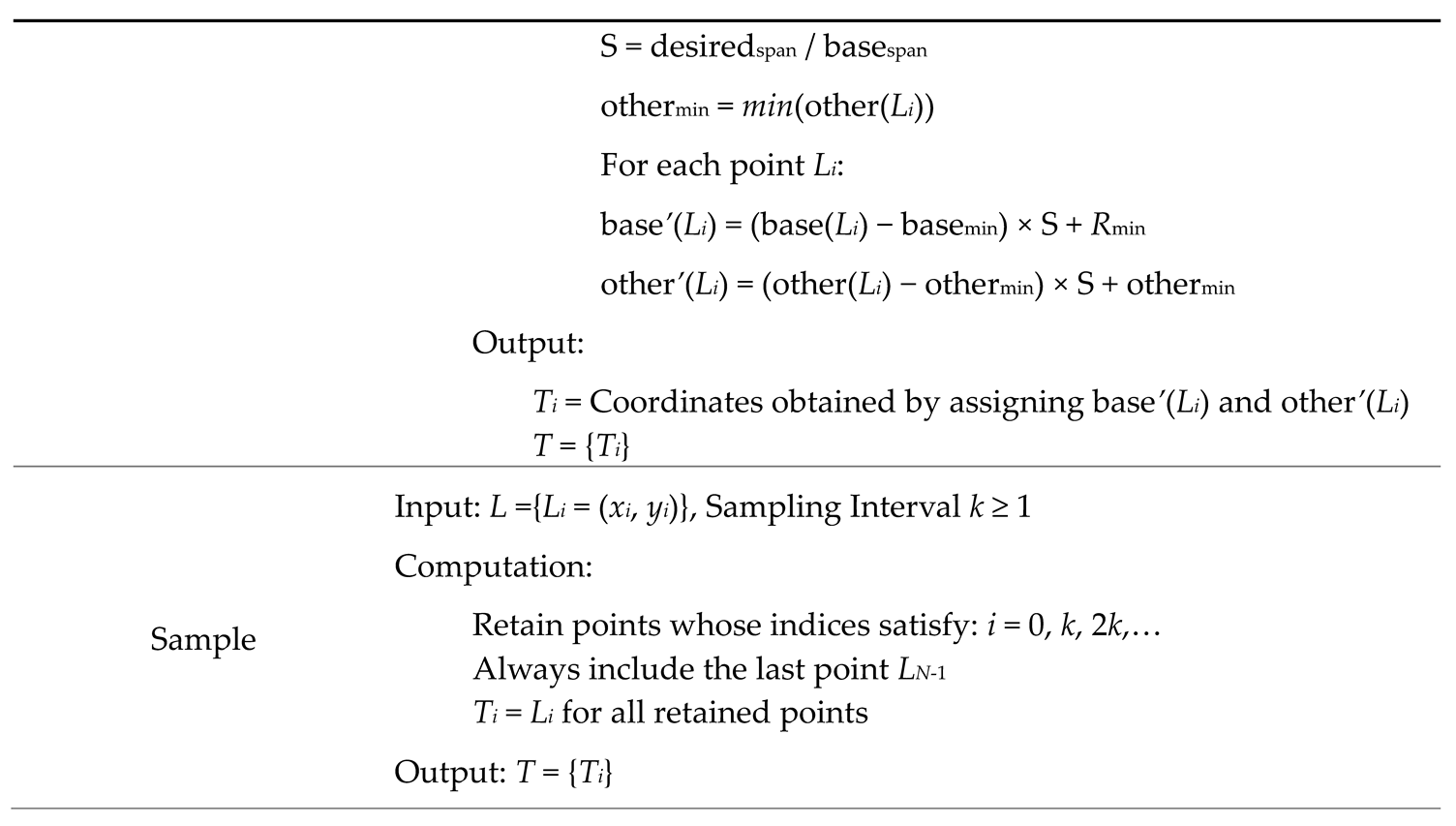

4.1.4. System D—Cleaning and Sequencing of Point Clouds

4.1.5. System E—Formatting of Point Clouds for Rendering Environments

4.2. Developing Functions for Rendering Layer

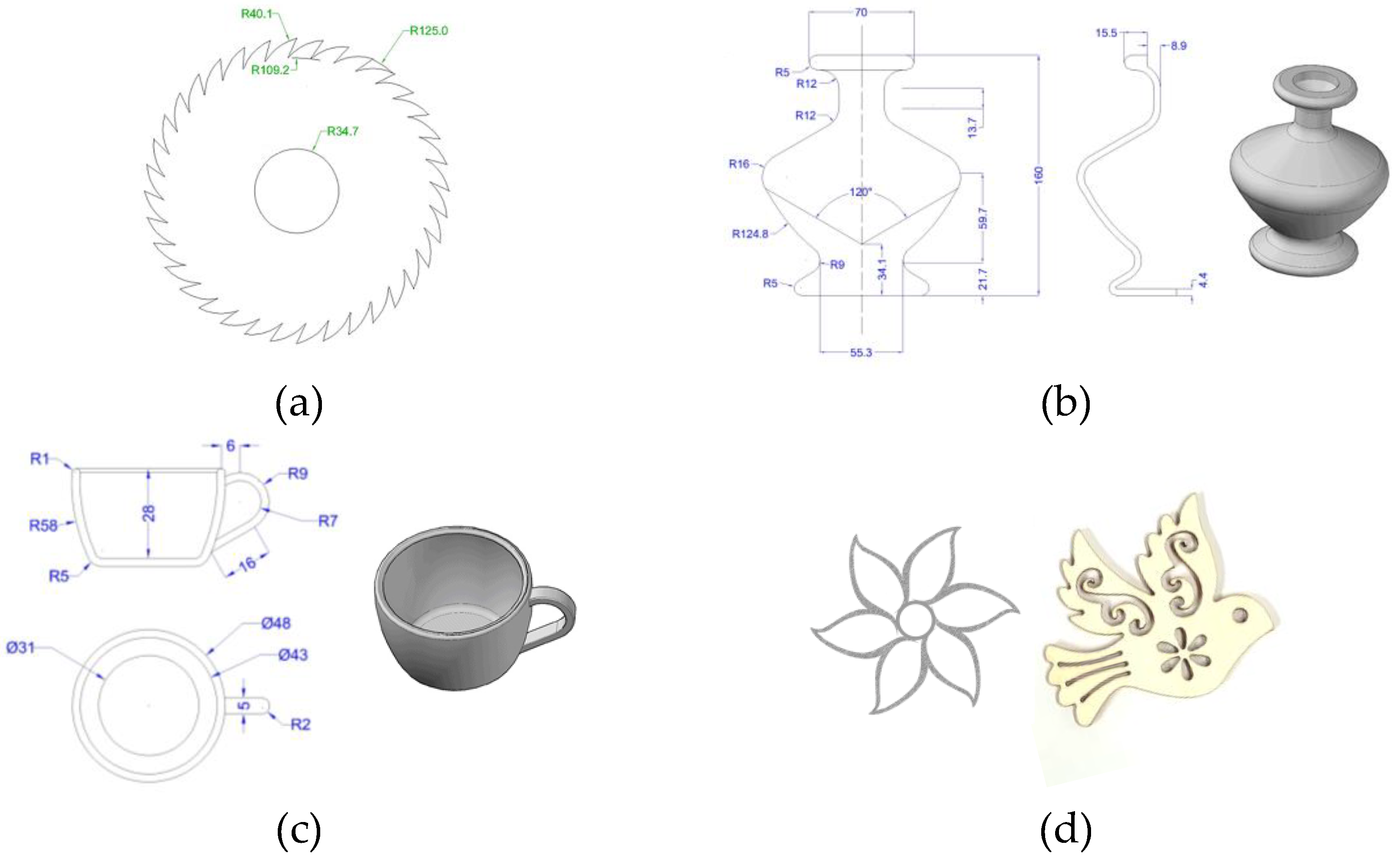

5. Application

5.1. Case 1

5.2. Case 2

5.3. Case 3

5.4. Case 4

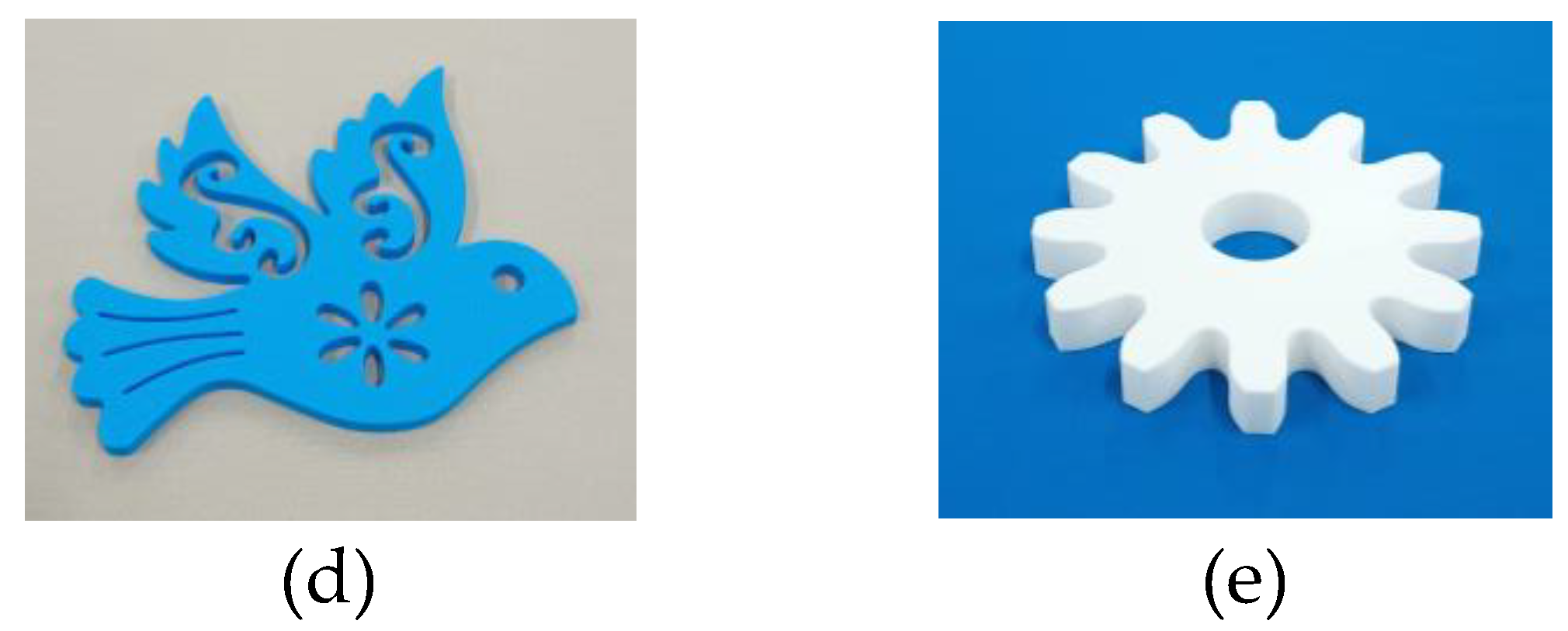

5.5. Case 5

5.6. Case 6

5.6. Broader Applications and Flexibility

6. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

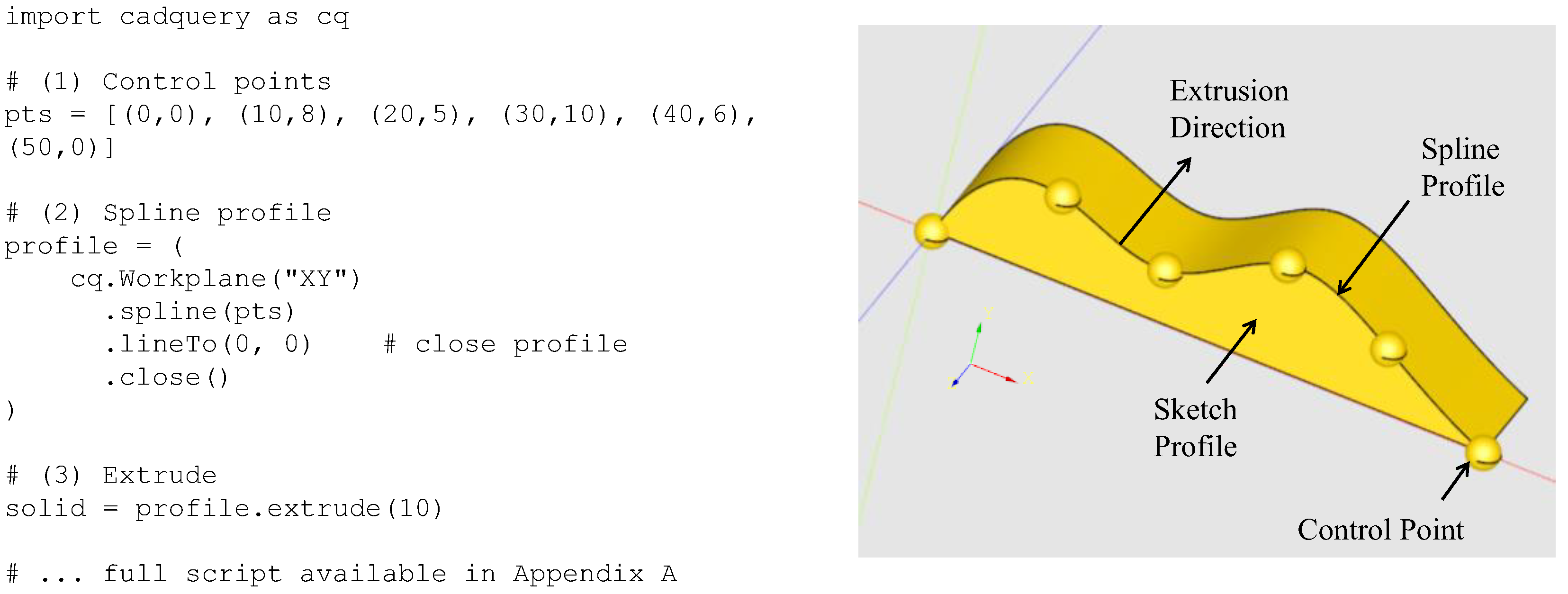

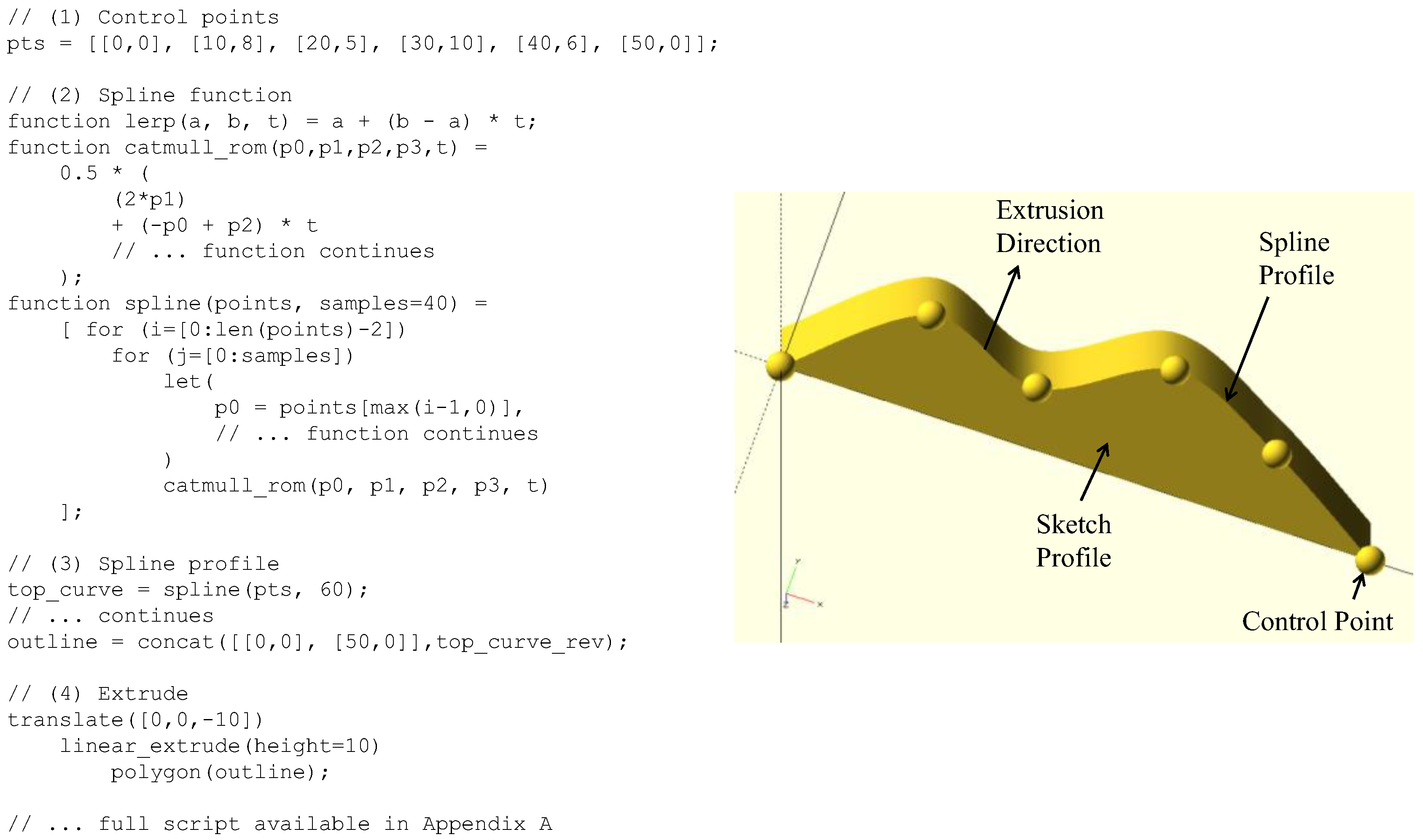

Appendix A. CAD Scripts Related to Section 2.

| import cadquery as cq # (1) Control points pts = [ (0, 0), # start on left (10, 8), (20, 5), (30, 10), (40, 6), (50, 0) # end on right ] # (2) Spline profile profile = ( cq.Workplane(“XY”) .spline(pts) .lineTo(0, 0) # close profile .close() ) # (3) Extrude solid = profile.extrude(-10) # negative = reverse direction # (4) Show control points spheres = [] for x, y in pts: spheres.append( cq.Workplane(“XY”) .center(x, y) .sphere(1.5) ) spheres_obj = spheres [0] for s in spheres [1:]: spheres_obj = spheres_obj.union(s) |

| // (1) Control points pts = [ [0,0], [10,8], [20,5], [30,10], [40,6], [50,0] ]; // (2) Spline function function lerp(a, b, t) = a + (b − a) * t; function catmull_rom(p0, p1, p2, p3, t) = 0.5 * ( 2*p1 + (-p0 + p2) * t + (2*p0 − 5*p1 + 4*p2 − p3) * t*t + (-p0 + 3*p1 − 3*p2 + p3) * t*t*t ); function spline(points, samples=40) = [ for (i=[0:len(points)-2]) for (j=[0:samples]) let( p0 = points[max(i-1,0)], p1 = points[i], p2 = points[i+1], p3 = points[min(i+2,len(points)-1)], t = j/samples ) catmull_rom(p0, p1, p2, p3, t) ]; // (3) Spline profile top_curve = spline(pts, 60); // build spline from control points top_curve_rev = [ for(i=[len(top_curve)-1:-1:0]) top_curve[i] ]; // reverse spline toward the start outline = concat([[0,0], [50,0]], top_curve_rev); // create closed profile // (4) Extrude translate([0,0,-10]) linear_extrude(height=10) polygon(outline); // (5) Show control points for (p = pts) translate([p [0], p [1], 0]) sphere(r=1.2, $fn=60); |

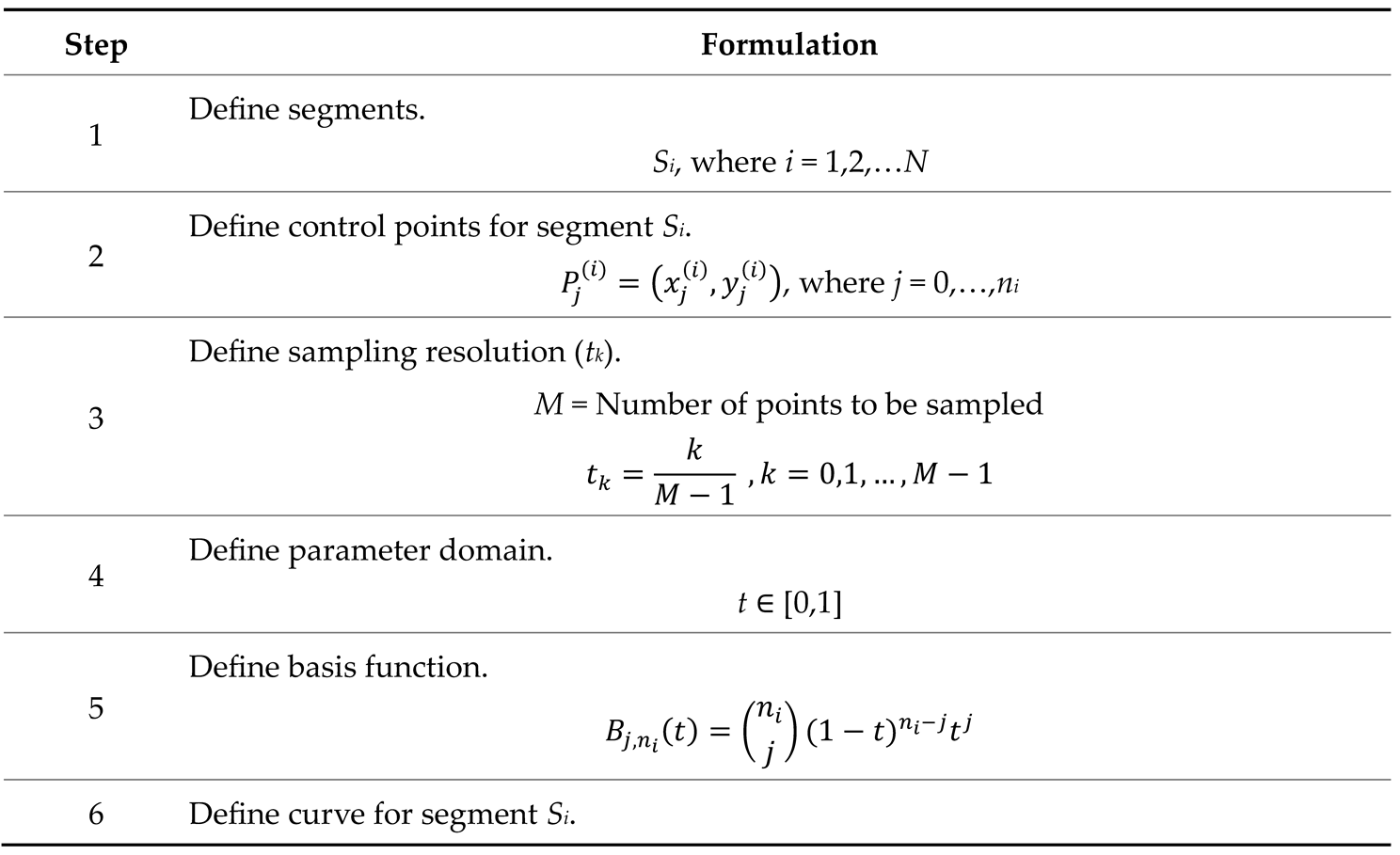

Appendix B. Formulations Related to System A (Section 4.1.1).

|

|

|

|

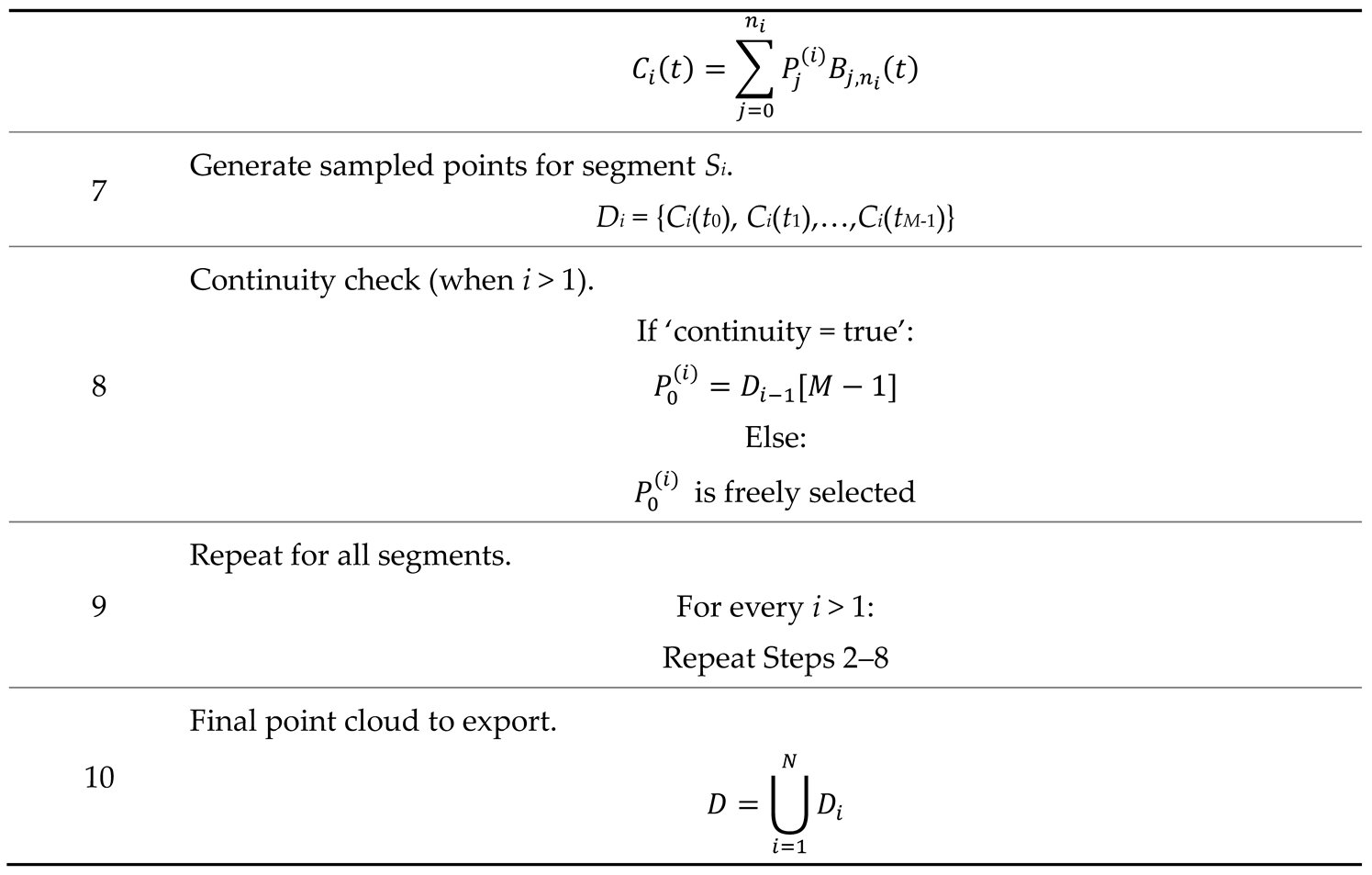

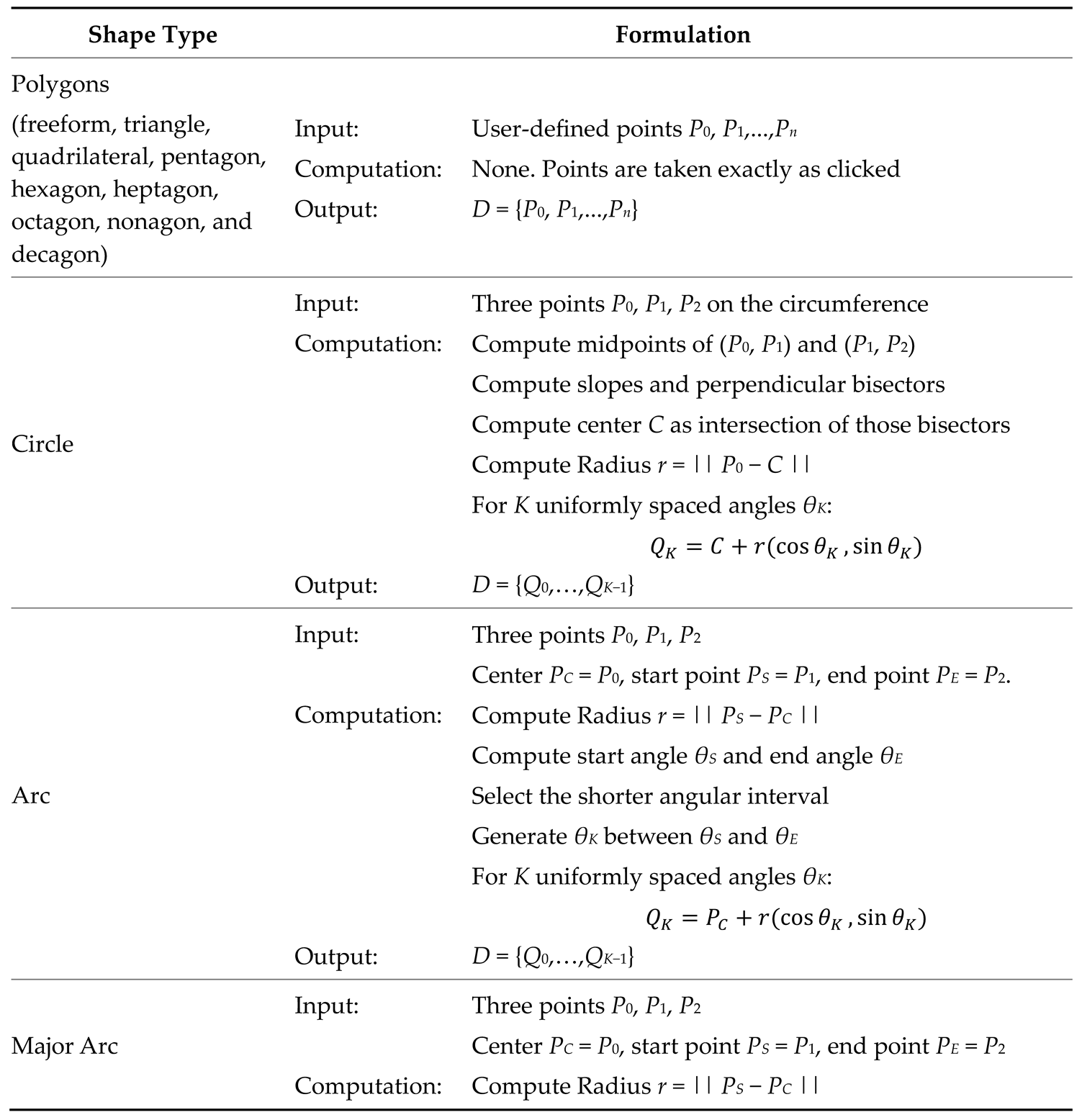

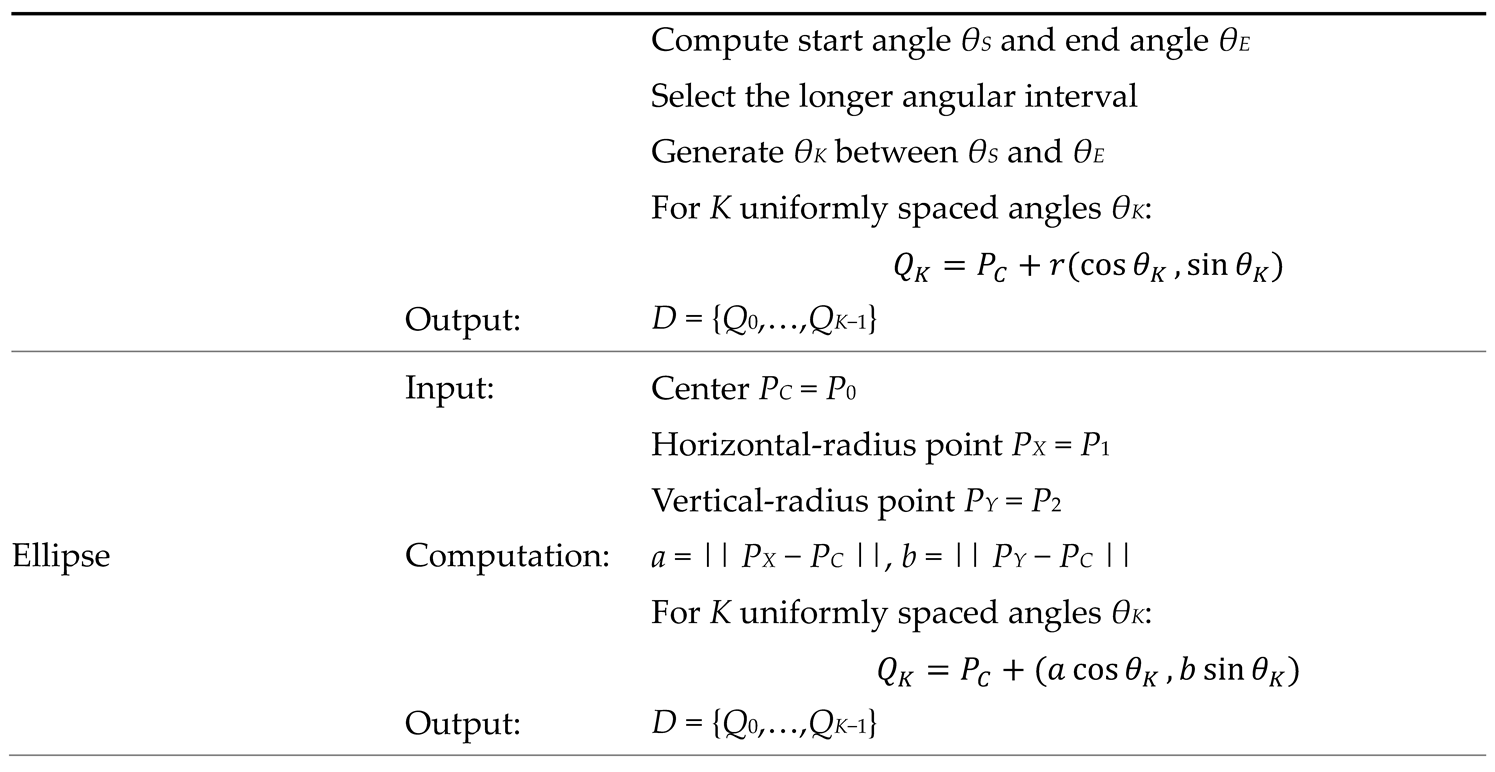

Appendix C. Formulations Related to System B (Section 4.1.2).

|

|

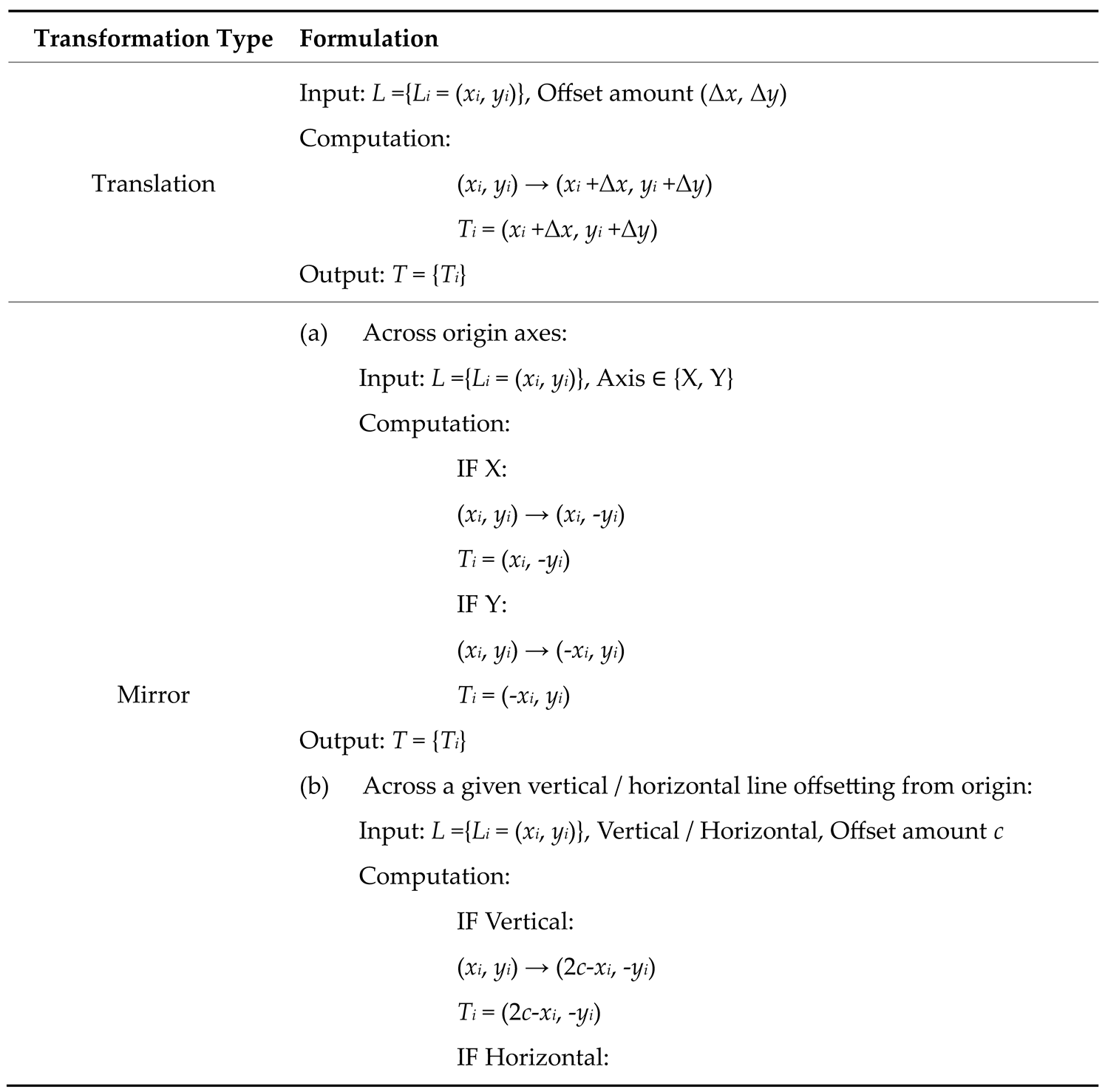

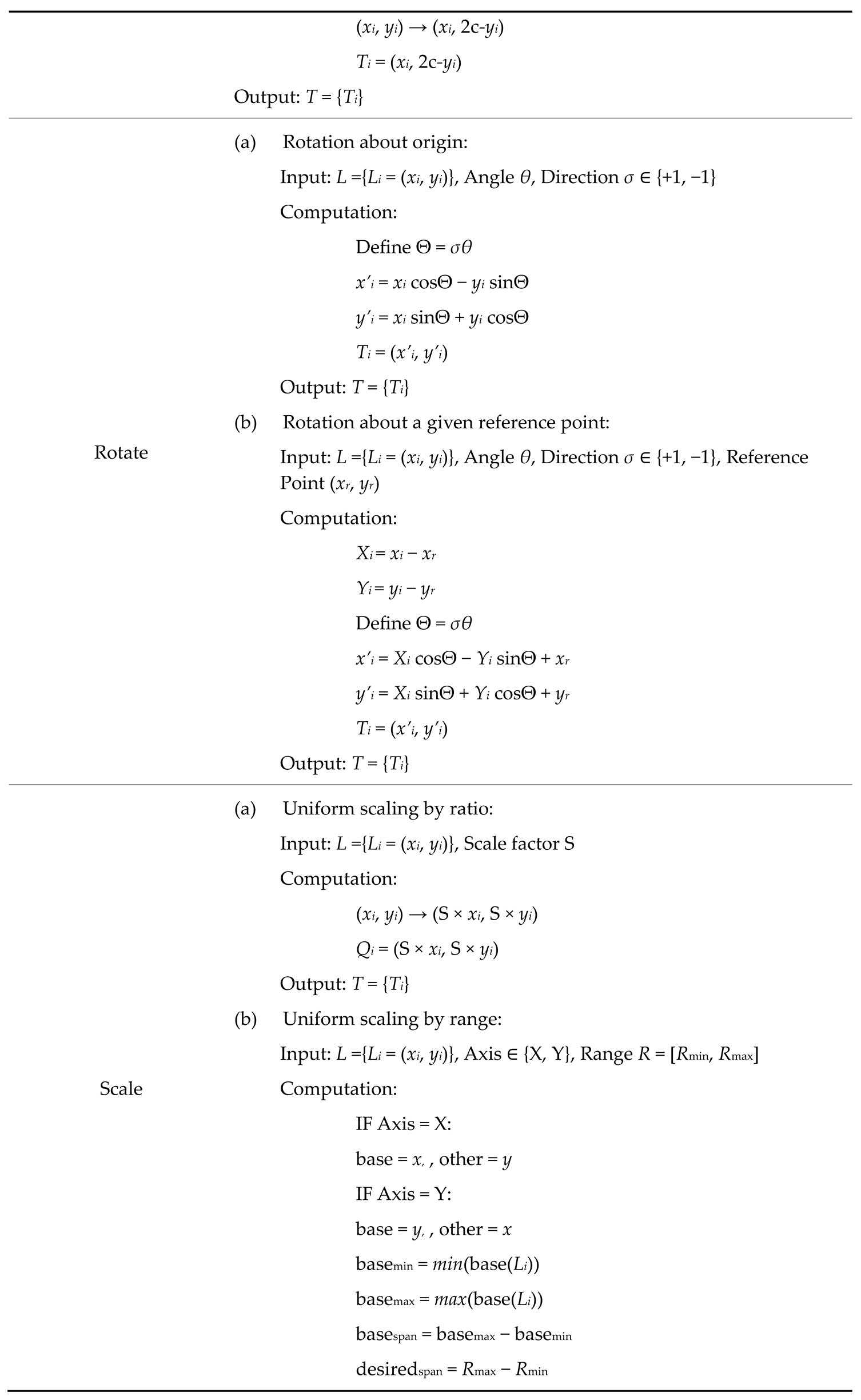

Appendix D. Formulations Related to System C (Section 4.1.3).

|

|

|

Appendix E. Formulations Related to System D (Section 4.1.4).

|

|

Appendix F. Developed Functions Related to OpenSCAD (Section 4.2).

| SN | Syntax | Input Arguments | Purpose (or Outcome) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | close_path (points_set) | points_set: A list of 2D points [[x, y], [x, y],...] |

Returns a new point set with the first point appended to the end. |

| 2 | show_points (points_set, radius, fragments, col) | points_set: A list of 2D points. radius: Radius of the sphere at each point. fragments: Controls smoothness of the sphere (number of fragments). col: Color of the spheres (string name or RGB list). |

Displays each point as a sphere. |

| 3 | create_polygon (points_set) | points_set: A list of 2D points in the order of polygon vertices. |

Draws a filled 2D polygon using the provided point set. |

| 4 | extrude_polygon (points_set, height) | points_set: A list of 2D points in the order of polygon vertices. height: Extrusion height. |

Extrudes a 2D polygon. |

| 5 | create_2d_path (points_set, width, fragments, shape) | points_set: A list of 2D points. width: Diameter (for circle) or side length (for square). fragments: Controls smoothness (used only if shape is “circle”). shape: Shape type for drawing hull — “circle” or “square”. |

Creates a 2D path using hulls between either circles or squares. |

| 6 | extrude_2d_path (points_set, width, fragments, height, shape) | points_set: A list of 2D points. width: Diameter (for circle) or side length (for square). fragments: Controls smoothness (used only if shape is “circle”). height: Extrusion height. shape: Shape type for drawing hull — “circle” or “square”. |

Extrudes a 2D path based on either circles or squares. |

References

- Dym, C.L.; Agogino, A.M.; Eris, O.; Frey, D.D.; Leifer, L.J. Engineering Design Thinking, Teaching, and Learning. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, C.; Browne, J. CADCAM: principles, practice and manufacturing management, 2. ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, England, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Groover, M.P. Automation, production systems, and computer-integrated manufacturing, Fifth edition; Pearson: New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Sato, M.; Watanabe, M.; Rashid, M. ; Bangladesh Institute of Management Integrating CAD, TRIZ, and Customer Needs. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2016, 10, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, I. Back to the future with CAD: its impact on product design and development. Des. Stud. 1990, 11, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, D.; Fritz, W. CAD in engineering education: Getting the balance right. in 2009 3rd IEEE International Conference on E-Learning in Industrial Electronics (ICELIE), Porto: IEEE, Nov. 2009, pp. 36–39. [CrossRef]

- Brink, H.; Kilbrink, N.; Gericke, N. Teach to use CAD or through using CAD: An interview study with technology teachers. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2022, 33, 957–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, D. The Maker Movement. Innov. Technol. Governance, Glob. 2012, 7, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Lab; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. Can. J. Commun. 2008, 33, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenfeld, N.A. Fab: the coming revolution on your desktop—from personal computers to personal fabrication, 1. ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund, M.; Leminen, S.; Rajahonka, M. Designing Business Models for the Internet of Things. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2014, 4, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, Y. The global manufacturing revolution: product-process-business integration and reconfigurable systems; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kutari, L.D.; Ura, S. Analyzing Customer-Producer Interaction System Using Axiomatic Design Theory. Proc. Int. Conf. Des. Concurr. Eng. Manuf. Syst. Conf. 2023, 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Rentzsch, M.; Ura, S. Fostering Empathy in AI-Driven Co-Creation of CAD Models. Procedia CIRP 2025, 134, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayna, T.; Striukova, L. The Impact of 3D Printing Technologies on Business Model Innovation. in Digital Enterprise Design & Management, vol. 261, P. Benghozi, D. Krob, A. Lonjon, and H. Panetto, Eds., in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol. 261. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp. 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, F.; Ghosh, A.K.; Ura, S. On the effective co-creation of CAD models by leveraging generative artificial intelligence. Procedia CIRP 2025, 134, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenSCAD — The Programmers’ Solid 3D CAD Modeller. [Online]. Available: https://openscad.org/.

- CadQuery contributors, CadQuery. (Oct. 28, 2025). Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Kopowski, J.; Mreła, A.; Mikołajewski, D.; Rojek, I. Enhancing 3D Printing with Procedural Generation and STL Formatting Using Python. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ju, F. Text-to-CadQuery: A New Paradigm for CAD Generation with Scalable Large Model Capabilities. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-De-Gabriel, J.M.; Muñoz-Ramírez, A.J.; Palacios, M.; Parras, L. Rapid end-of-arm-tooling manufacturing of vacuum grippers. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2019, 32, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Khan, S.; Erkoyuncu, J.A. An Investigation on Utilizing Large Language Model for Industrial Computer-Aided Design Automation. Procedia CIRP 2024, 128, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.; Malpica, N.; Borromeo, S. Parametric CAD modeling for open source scientific hardware: Comparing OpenSCAD and FreeCAD Python scripts. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0225795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.F.; Pietrzak, T.; Girouard, A.; Casiez, G. Facilitating the Parametric Definition of Geometric Properties in Programming-Based CAD. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Oct. 2024, Pittsburgh PA USA: ACM; pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Makatura, L.; et al. How Can Large Language Models Help Humans in Design and Manufacturing? arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makatura, L.; Foshey, M.; Wang, B.; Hähnlein, F.; Ma, P.; Deng, B.; Tjandrasuwita, M.; Spielberg, A.; Owens, C.; Chen, P.Y.; et al. How Can Large Language Models Help Humans in Design and Manufacturing? Part 1: Elements of the LLM-Enabled Computational Design and Manufacturing Pipeline. Harvard Data Science Review 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makatura, L.; Foshey, M.; Wang, B.; Hähnlein, F.; Ma, P.; Deng, B.; Tjandrasuwita, M.; Spielberg, A.; Owens, C.; Chen, P.Y.; et al. How Can Large Language Models Help Humans in Design And Manufacturing? Part 2: Synthesizing an End-to-End LLM-Enabled Design and Manufacturing Workflow. Harvard Data Science Review 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filz, M.-A.; Thiede, S. Generative AI in Manufacturing Systems: Reference Framework and Use Cases. Procedia CIRP 2024, 130, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.D.; Goenner, B.L.; Gale, B.K. Utilizing ChatGPT to assist CAD design for microfluidic devices. Lab a Chip 2023, 23, 3778–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.F.G.; Pietrzak, T.; Girouard, A.; Casiez, G. Understanding the Challenges of OpenSCAD Users for 3D Printing. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu HI USA, May 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, C.; Jensen, J.K.; McQuaid, M.; Ashbrook, D. Barriers to End-User Designers of Augmented Fabrication. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow Scotland Uk: ACM, May 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Double Diamond—Design Council.” Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/.

- Hatchuel, A.; Weil, B. C-K design theory: an advanced formulation. Res. Eng. Des. 2008, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutari, L.D.; Ura, S. Improving reverse engineering processes using C-K theory of design. Res. Eng. Des. 2025, 36, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashi; Ullah, A.S.; Watanabe, M.; Kubo, A. Analytical Point-Cloud Based Geometric Modeling for Additive Manufacturing and Its Application to Cultural Heritage Preservation. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 656. [CrossRef]

- Tashi; Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Kubo, A.; Tashi, T. Developing a Human-Cognition-Based Reverse Engineering Approach. In Proceedings of the JSME 2020 Conference on Leading Edge Manufacturing/Materials and Processing, Virtual, Online, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Farin, G. The Bernstein Form of a Bézier Curve. In Curves and Surfaces for CAGD, Elsevier, 2002; pp. 57–79. [CrossRef]

- Computer graphics: principles and practice, 2. ed.; in C, Reprinted with corr., 25. print. in The systems programming series; Foley, J.D., Ed.; Addison-Wesley: Bosto, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bostock, M.; Ogievetsky, V.; Heer, J. D³ Data-Driven Documents. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2011, 17, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What is D3?” Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://d3js.org/what-is-d3.

- D3.js: Data-Driven Documents. Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://d3js.org/.

- Plotly.js: Open-Source JavaScript Graphing Library. Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://plotly.com/javascript/.

- Welcome to Python.org. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; Volume 445, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- jExcel: Lightweight JavaScript Data Grid (Community Edition, MIT License). Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/jspreadsheet/ce.

- jSuites UI Library. jSuites — JavaScript UI Components. Accessed: Nov. 23, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://jsuites.net/.

| Functional Requirements | System A | System B | System C | System D | System E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User Interface (UI) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Direct UI Manipulation | ○ | ○ | |||

| Indirect UI Manipulation | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Data Importing | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Parametric Curve Evaluation | ○ | ||||

| Geometric Primitive Generation | ○ | ||||

| Piecewise Construction | ○ | ||||

| Piecewise Point Sampling | ○ | ||||

| Piecewise Continuity | ○ | ||||

|

Transformation

(Rotation, Mirror, Scale…) |

○ | ○ | |||

| Cleaning and Sequencing | ○ | ||||

| Data Formatting | ○ | ||||

| Data Exporting | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).