Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

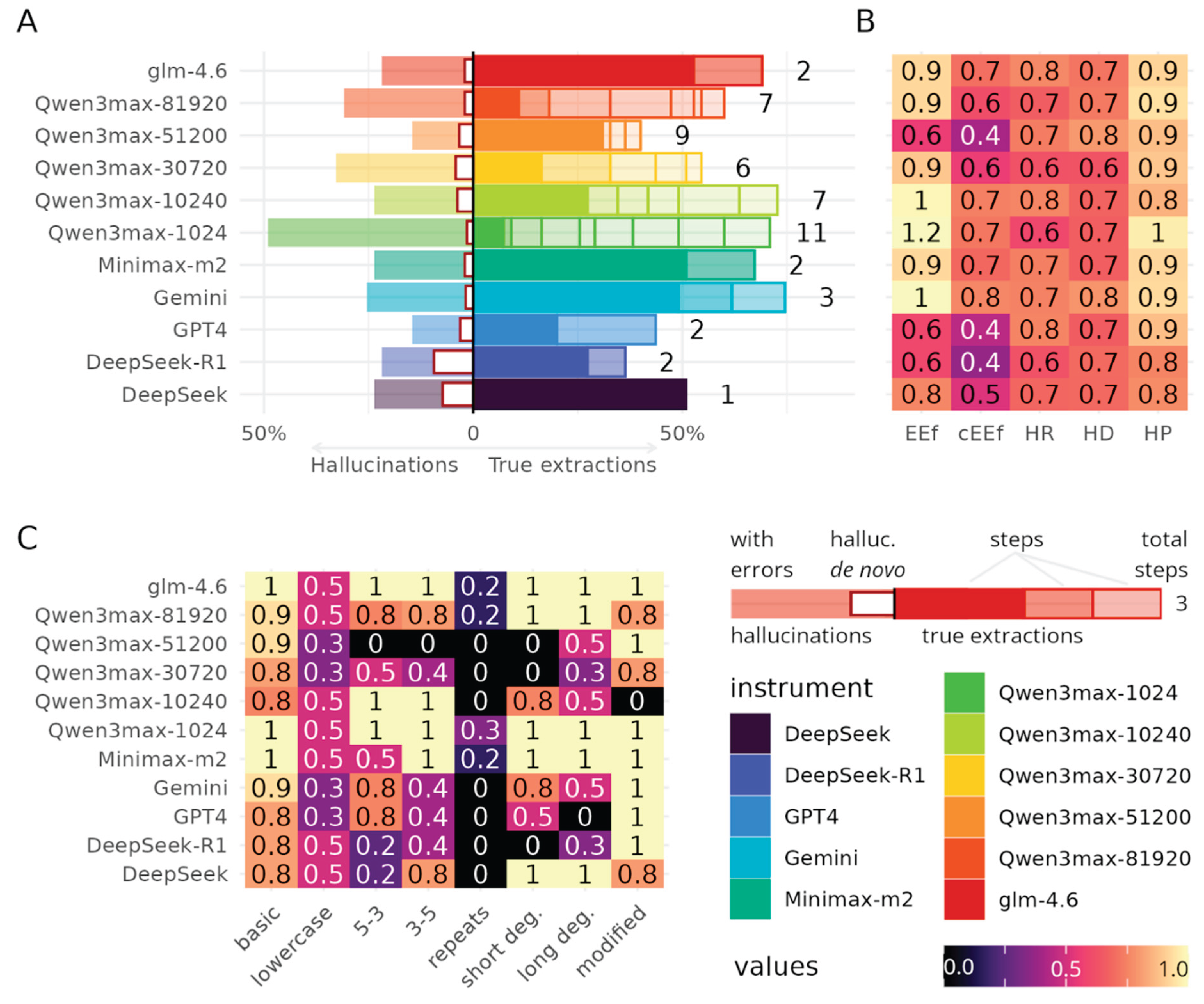

2.1. LLM Benchmarking

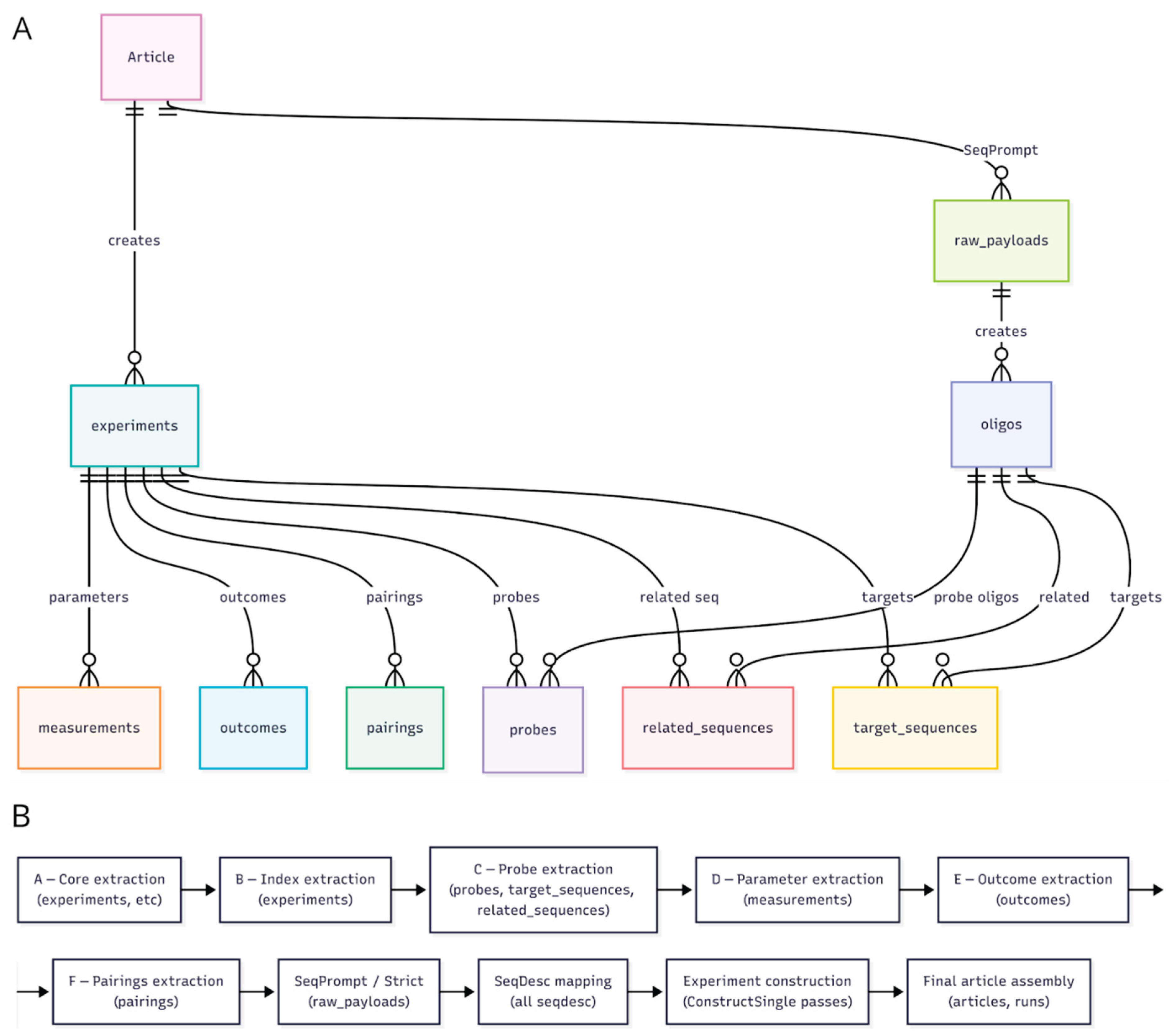

2.2. Data Extraction Pipeline

3. Results

3.1. Benchmarking

3.2. Tool Architecture

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Artificial Data |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| cEEf | Corrected Extraction Efficiency |

| EEf | Extraction Efficiency |

| EEr | Extraction Errors |

| ExEr | Experiment Errors |

| ggplot2 | Grammar of Graphics plotting library for R |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HD | Hallucination Distance |

| HR | Hallucination Rate |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LEr | Linking Errors |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| lme4 | Linear Mixed-Effects Models for R |

| OCR | Optical Character Recognition |

| Portable Document Format | |

| R | R programming language |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| RD | Real Data |

| SOTA | State of the Art |

| SQL | Structured Query Language |

| UML | Unified Modeling Language |

References

- Garcia, G.L.; Manesco, J.R.R.; Paiola, P.H.; Miranda, L.; de Salvo, M.P.; Papa, J.P. A Review on Scientific Knowledge Extraction Using Large Language Models in Biomedical Sciences 2024.

- Gartlehner, G.; Kugley, S.; Crotty, K.; Viswanathan, M.; Dobrescu, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Booth, G.; Treadwell, J.R.; Han, J.M.; Wagner, J.; et al. AI-Assisted Data Extraction with a Large Language Model: A Study Within Reviews 2025.

- Schmidt, L.; Hair, K.; Graziosi, S.; Campbell, F.; Kapp, C.; Khanteymoori, A.; Craig, D.; Engelbert, M.; Thomas, J. Exploring the Use of a Large Language Model for Data Extraction in Systematic Reviews: A Rapid Feasibility Study. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rettenberger, L.; Münker, M.F.; Schutera, M.; Niemeyer, C.M.; Rabe, K.S.; Reischl, M. Using Large Language Models for Extracting Structured Information From Scientific Texts. Curr. Dir. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 10, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, D.; Kliegr, T. Traceable LLM-Based Validation of Statements in Knowledge Graphs. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougherty, A.V.; Clipp, H.L. Testing the Reliability of an AI-Based Large Language Model to Extract Ecological Information from the Scientific Literature. Npj Biodivers. 2024, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keck, F.; Broadbent, H.; Altermatt, F. Extracting Massive Ecological Data on State and Interactions of Species Using Large Language Models 2025, 2025. 01.24.63 4685.

- Jung, S.J.; Kim, H.; Jang, K.S. LLM Based Biological Named Entity Recognition from Scientific Literature. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp); IEEE: Bangkok, Thailand, 18 February 2024; pp. 433–435. [Google Scholar]

- Konet, A.; Thomas, I.; Gartlehner, G.; Kahwati, L.; Hilscher, R.; Kugley, S.; Crotty, K.; Viswanathan, M.; Chew, R. Performance of Two Large Language Models for Data Extraction in Evidence Synthesis. Res. Synth. Methods 2024, 15, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartlehner, G.; Kahwati, L.; Hilscher, R.; Thomas, I.; Kugley, S.; Crotty, K.; Viswanathan, M.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Booth, G.; Erskine, N.; et al. Data Extraction for Evidence Synthesis Using a Large Language Model: A Proof-of-concept Study. Res. Synth. Methods 2024, 15, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, S.; Zou, Z.; Bono, H.; Moriya, Y.; Kawashima, S.; Katayama, T.; Oki, S.; Ohta, T. Extraction of Biological Terms Using Large Language Models Enhances the Usability of Metadata in the BioSample Database. GigaScience 2025, 14, giaf070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Peng, X.; Xie, Q.; Jin, Q.; Gilson, A.; Singer, M.B.; Ai, X.; Lai, P.-T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Benchmarking Large Language Models for Biomedical Natural Language Processing Applications and Recommendations. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konet, A.; Thomas, I.; Gartlehner, G.; Kahwati, L.; Hilscher, R.; Kugley, S.; Crotty, K.; Viswanathan, M.; Chew, R. Performance of Two Large Language Models for Data Extraction in Evidence Synthesis. Res. Synth. Methods 2024, 15, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanisenko, T.V.; Demenkov, P.S.; Ivanisenko, V.A. An Accurate and Efficient Approach to Knowledge Extraction from Scientific Publications Using Structured Ontology Models, Graph Neural Networks, and Large Language Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.; Chen, D.; Dai, W.; et al. Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, R.; Tian, Y.; Li, J. Towards Instruction-Tuned Verification for Improving Biomedical Information Extraction with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); IEEE: Lisbon, Portugal, December 3, 2024; pp. 6685–6692. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Ayub, U.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Khakwani, K.Z.R.; Sipra, Z.B.R.; Raina, A.; Zhou, S.; He, H.; Saeidi, A.; Hasan, B.; et al. Collaborative Large Language Models for Automated Data Extraction in Living Systematic Reviews. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keck, F.; Broadbent, H.; Altermatt, F. Extracting Massive Ecological Data on State and Interactions of Species Using Large Language Models 2025.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooms, J. The Jsonlite Package: A Practical and Consistent Mapping Between JSON Data and R Objects. ArXiv14032805 StatCO 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, M.P.J. van der The Stringdist Package for Approximate String Matching. R J. 2014, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A. Ggpubr: “ggplot2” Based Publication Ready Plots; 2023.

- Yu, G. Aplot: Decorate a “ggplot” with Associated Information; 2025.

- Smutin, D. Ggviolinbox: Half-Violin and Half-Boxplot Geoms for Ggplot2 2025.

- Wilke, C.O. Ggridges: Ridgeline Plots in “Ggplot2”; 2025.

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datalab-to/Marker 2025.

- Willard, B.T.; Louf, R. Efficient Guided Generation for Large Language Models 2023.

- Wright, A.; Andrews, H.; Hutton, B.; Dennis, G. JSON Schema: A Media Type for Describing JSON Documents; JSON Schema, 2020.

- Hipp, R.D. SQLite 2020.

- Yang, A.; Yu, B.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, F.; Huang, H.; Jiang, J.; Tu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; et al. Qwen2.5-1M Technical Report 2025.

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 Technical Report 2025.

- Kwon, W.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, S.; Sheng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yu, C.H.; Gonzalez, J.; Zhang, H.; Stoica, I. Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles; ACM: Koblenz Germany, October 23, 2023; pp. 611–626. [Google Scholar]

- Gemma Team; Kamath, A.; Ferret, J.; Pathak, S.; Vieillard, N.; Merhej, R.; Perrin, S.; Matejovicova, T.; Ramé, A.; Rivière, M.; et al. Gemma 3 Technical Report 2025.

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Behl, H.; Bubeck, S.; Eldan, R.; Gunasekar, S.; Harrison, M.; Hewett, R.J.; Javaheripi, M.; Kauffmann, P.; et al. Phi-4 Technical Report 2024.

- Ollama/Ollama 2025.

- Yin, Z. A Review of Methods for Alleviating Hallucination Issues in Large Language Models. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 76, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhasani, M.; Pan, R. Leveraging LLM for Automated Ontology Extraction and Knowledge Graph Generation; 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).