Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

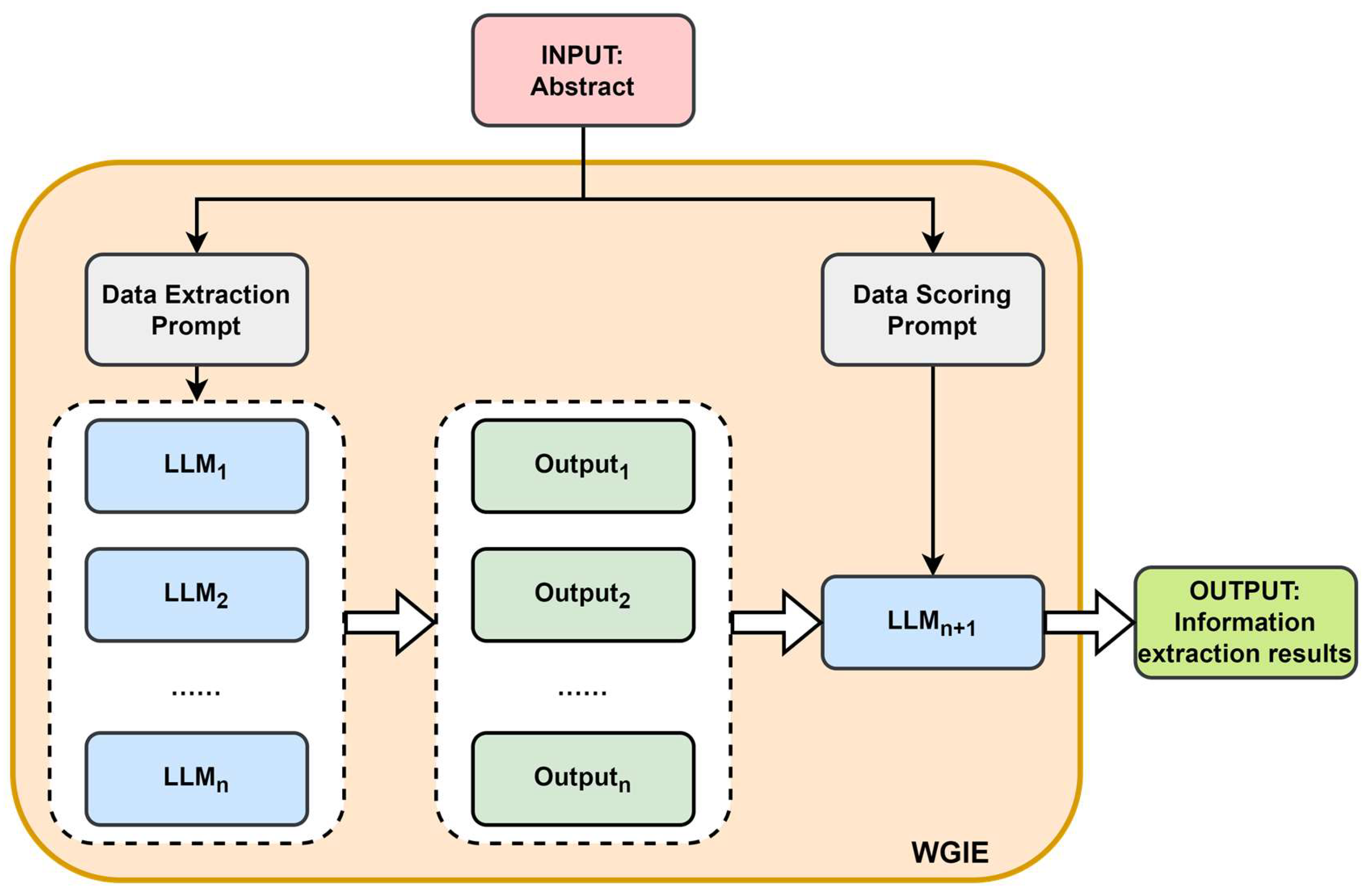

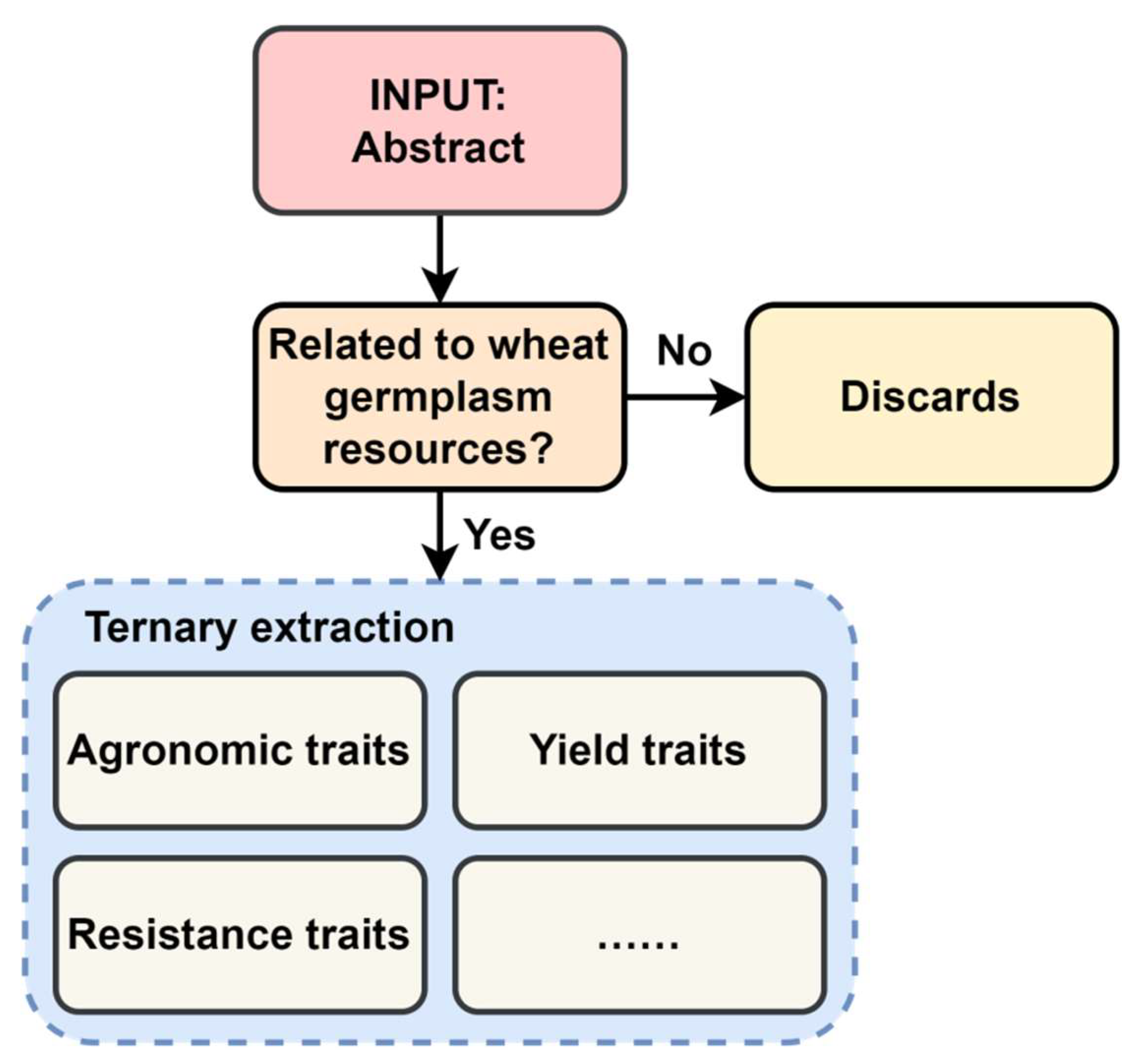

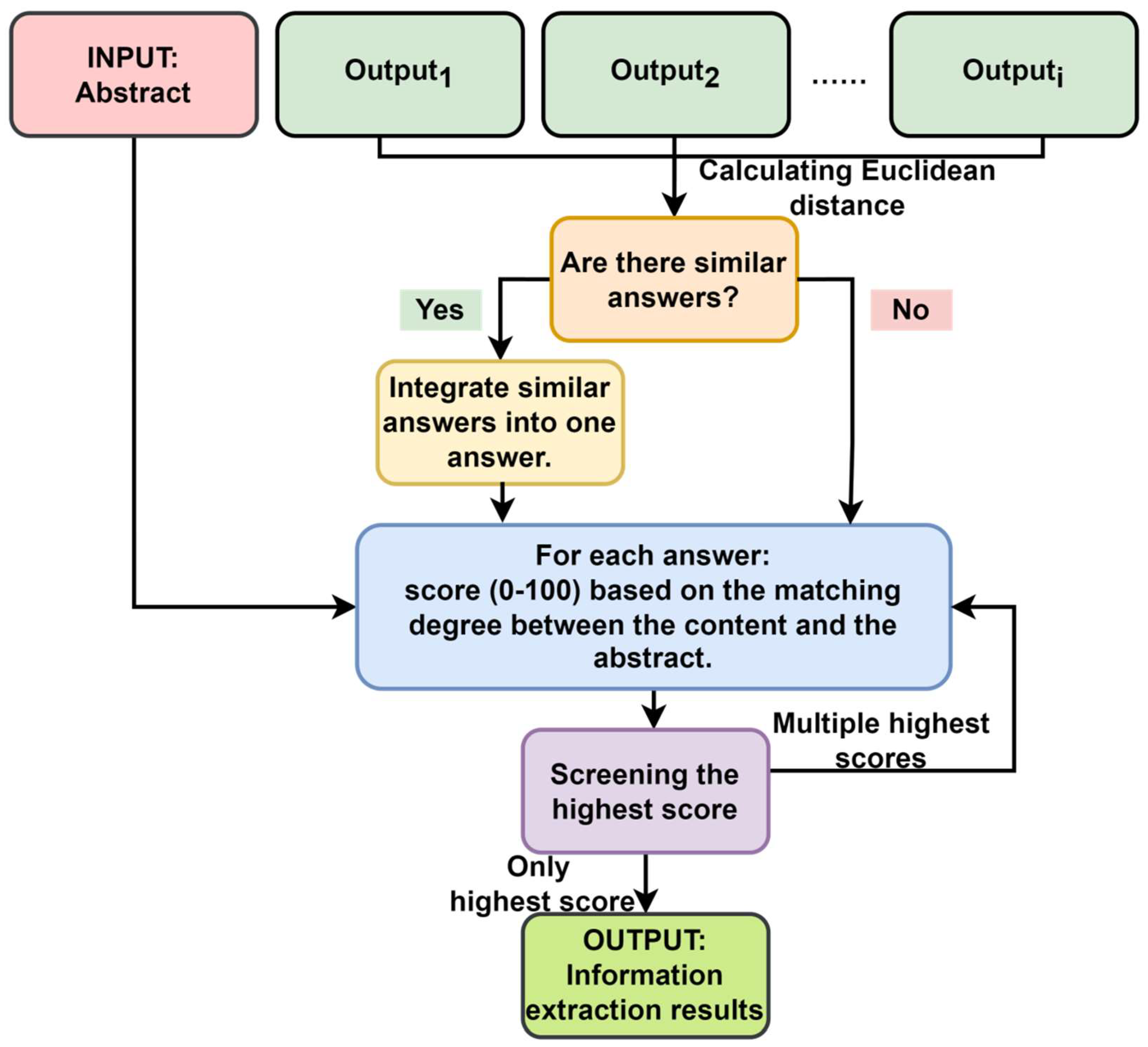

Increased wheat production is crucial for addressing food security concerns caused by limited resources, extreme weather, and population expansion. However, breeders have challenges due to fragmented information in multiple research articles, which slows progress in generating high-yield, stress-resistant, and high-quality wheat. This study presents WGIE (Wheat Germplasm Information Extraction), a wheat research article abstract-specific data extraction workflow based on conversational large language models (LLMs) and rapid engineering. WGIE employs zero-shot learning, multi-response polling to reduce hallucinations, and a calibration component to ensure optimal outcomes.Validation on 443 abstracts yielded 0.8010 Precision, 0.9969 Recall, 0.8883 F1 Score, and 0.8171 Accuracy, proving the ability to extract data with little human effort. Analysis found that irrelevant text increases the chance of hallucinations, emphasizing the necessity of matching prompts to input language. While WGIE efficiently harvests wheat germplasm information, its effectiveness is dependent on the consistency of prompts and text. Managing conflicts and enhancing prompt design can improve LLM performance in subsequent jobs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Large Language Model

2.2. Prompt Engineering

3. Methodology

3.1. Data sources

3.2. Information Extraction Program

3.3. Experimental Setup

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

4. Result

4.1. Result of Performance Evaluation

4.2. An Analysis of LLM Experiments with Contradictory Inputs

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

References

- Blake, V.C.; Woodhouse, M.R.; Lazo, G.R. GrainGenes: Centralized Small Grain Resources and Digital Platform for Geneticists and Breeders. Database 2019, 2019, baz065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khaki, S.; Safaei, N.; Pham, H.; Wang, L. WheatNet: A lightweight convolutional neural network for high-throughput image-based wheat head detection and counting. Neurocomputing 2022, 489, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lian, S.; Guo, F.; Wang, Z. A Survey of Information Extraction Based on Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Dunn, J. A. Dunn, J. Dagdelen, N. Walker, S. Lee, A. S. Rosen, G. Ceder, K. Persson, A. Jain, Structured information extraction from complex scientific text with fine-tuned large language models. arXiv:2212.05238.

- M. P. Polak, S. Modi, A. Latosinska, J. Zhang, C.-W. Wang, S. Wang, A. D. Hazra, D. Morgan, Flexible, model-agnostic method for materials data extraction from text using general purpose language models. Digital Discovery 2024, 3, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, M.P.; Morgan, D. Extracting accurate materials data from research papers with conversational language models and prompt engineering. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Y. Y. Zhang, Y. Li, L. Cui, D. Cai, L. Liu, T. Fu, X. Huang, E. Zhao, Y. Zhang, Y. Chen, et al., Siren’s song in the ai ocean: a survey on hallucination in large language model. arXiv:2309.01219.

- N. F. Liu, K. Lin, J. Hewitt, A. Paranjape, M. Bevilacqua, F. Petroni, P. Liang, Lost in the middle: How language models use long contexts. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2024, 12, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Luo, Z. Y. Luo, Z. Yang, F. Meng, Y. Li, J. Zhou, Y. Zhang, An empirical study of catastrophic forgetting in large language models during continual fine-tuning. arXiv:2308.08747.

- J. Achiam, S. J. Achiam, S. Adler, S. Agarwal, L. Ahmad, I. Akkaya, F. L. Aleman, D. Almeida, J. Altenschmidt, S. Altman, S. Anadkat, et al., Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv:2303.08774.

- Hajikhani, A.; Cole, C. Author response for "A Critical Review of Large Language Models: Sensitivity, Bias, and the Path Toward Specialized AI". 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Bolton, D. E. Bolton, D. Hall, M. Yasunaga, T. Lee, C. Manning, P. Liang, Biomedlm: a domain-specific large language model for biomedical text, Stanford CRFM Blog.

- Luo, R.; Sun, L.; Xia, Y.; Qin, T.; Zhang, S.; Poon, H.; Liu, T.-Y. BioGPT: generative pre-trained transformer for biomedical text generation and mining. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Wu, X. Zhang, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, W. Xie, Pmc-llama: Further finetun-ing llama on medical papers, arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.14454 2023, arXiv:2304.14454 2023, 2, 62, 6.

- H. Touvron, T. H. Touvron, T. Lavril, G. Izacard, X. Martinet, M.-A. Lachaux, T. Lacroix, B. Rozi`ere, N. Goyal, E. Hambro, F. Azhar, et al., Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971.

- A. Toma, P. R. A. Toma, P. R. Lawler, J. Ba, R. G. Krishnan, B. B. Rubin, B. Wang, Clinical camel: An open expert-level medical language model with dialoguebased knowledge encoding. arXiv:2305.12031.

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Dan, R.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y. ChatDoctor: A Medical Chat Model Fine-Tuned on a Large Language Model Meta-AI (LLaMA) Using Medical Domain Knowledge. Cureus 2023, 15, e40895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Han, L. C. T. Han, L. C. Adams, J.-M. Papaioannou, P. Grundmann, T. Oberhauser, A. L¨oser, D. Truhn, K. K. Bressem, Medalpaca – an open-source collection of medical conversational ai models and training data (2023). 0824; arXiv:2304.08247.URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2304. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, S.; Jin, Q.; Yeganova, L.; Lai, P.-T.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Kim, W.; Comeau, D.C.; et al. Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; Payne, P.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z. How to write effective prompts for large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hayashi, H.; Neubig, G. Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Floridi, M. Chiriatti, Gpt-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Minds and Machines 2020, 30, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Mann, N. B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell, S. Agarwal, et al., Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv:2005.14165.

- H. Touvron, L. H. Touvron, L. Martin, K. Stone, P. Albert, A. Almahairi, Y. Babaei, N. Bashlykov, S. Batra, P. Bhargava, S. Bhosale, et al., Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv:2307.09288.

- Min, B.; Ross, H.; Sulem, E.; Ben Veyseh, A.P.; Nguyen, T.H.; Sainz, O.; Agirre, E.; Heintz, I.; Roth, D. Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing via Large Pre-trained Language Models: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.M.; Park, D.; Kang, J.; Lee, S.-W.; Park, W. GPT3Mix: Leveraging Large-scale Language Models for Text Augmentation. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, Dominican RepublicDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 2225–2239.

- Albrecht, J. A.; Kitanidis, E. C.; Fetterman, A. J. Despite "super-human" performance, current LLMs are unsuited for decisions about ethics and safety. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.06295. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P.P.; Wu, C.; Morency, L.P. Towards understanding and mitigating social biases in language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR: 2021; 6565-6576. [Google Scholar]

- Alvi, M.; Zisserman, A.; Nellåker, C. Turning a blind eye: Explicit removal of biases and variation from deep neural network embeddings. Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. (ECCV) Workshops 2018, 0-0.

- Zhang, J.; Verma, V. Discover Discriminatory Bias in High Accuracy Models Embedded in Machine Learning Algorithms. In The International Conference on Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020, pp. 1537–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Hilton, J.; Evans, O. TruthfulQA: Measuring How Models Mimic Human Falsehoods. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, IrelandDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 3214–3252.

- X. Liu, Y. X. Liu, Y. Zheng, Z. Du, M. Ding, Y. Qian, Z. Yang, J. Tang, Gpt understands, too, AI Open.

- J. Wei, X. Wang, D. Schuurmans, M. Bosma, F. Xia, E. Chi, Q. V. Le, D. Zhou, et al., Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- S. Yao, D. S. Yao, D. Yu, J. Zhao, I. Shafran, T. Griffiths, Y. Cao, K. Narasimhan, Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36.

- Besta, M.; Blach, N.; Kubicek, A.; Gerstenberger, R.; Podstawski, M.; Gianinazzi, L.; Gajda, J.; Lehmann, T.; Niewiadomski, H.; Nyczyk, P.; et al. Graph of Thoughts: Solving Elaborate Problems with Large Language Models. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 17682–17690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Yao, J. S. Yao, J. Zhao, D. Yu, N. Du, I. Shafran, K. Narasimhan, Y. Cao, React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. arXiv:2210.03629.

- X. Wang, J. X. Wang, J. Wei, D. Schuurmans, Q. Le, E. Chi, S. Narang, A. Chowdhery, D. Zhou, Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv:2203.11171.

- Zhao, B.; Jin, W.; Del Ser, J.; Yang, G. ChatAgri: Exploring potentials of ChatGPT on cross-linguistic agricultural text classification. Neurocomputing 2023, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Liu, K.; Yang, P. Embedding-based Retrieval with LLM for Effective Agriculture Information Extracting from Unstructured Data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.0 3107, arXiv:2308.03107, 2023, 1-12023, 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, J.; Deng, X.; Lan, Y.; Li, Z. GPT-aided diagnosis on agricultural image based on a new light YOLOPC. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Hendrycks, C. D. Hendrycks, C. Burns, S. Basart, A. Zou, M. Mazeika, D. Song, J. Steinhardt, Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv:2009.03300.

- Zellers, R.; Holtzman, A.; Bisk, Y.; Farhadi, A.; Choi, Y. HellaSwag: Can a Machine Really Finish Your Sentence?. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ItalyDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- M. Suzgun, N. M. Suzgun, N. Scales, N. Sch¨arli, S. Gehrmann, Y. Tay, H. W. Chung, A. Chowdhery, Q. V. Le, E. H. Chi, D. Zhou, et all., Challenging bigbench tasks and whether chain-of-thought can solve them. arXiv:2210.09261.

- K. Cobbe, V. K. Cobbe, V. Kosaraju, M. Bavarian, M. Chen, H. Jun, L. Kaiser, M. Plappert, J. Tworek, J. Hilton, R. Nakano, et al., Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv:2110.14168.

- D. Hendrycks, C. D. Hendrycks, C. Burns, S. Kadavath, A. Arora, S. Basart, E. Tang, D. Song, J. Steinhardt, Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. arXiv:2103.03874.

- J. Bai, S. J. Bai, S. Bai, Y. Chu, Z. Cui, K. Dang, X. Deng, Y. Fan, W. Ge, Y. Han, F. Huang, et al., Qwen technical report. arXiv:2309.16609.

- A. Young, B. A. Young, B. Chen, C. Li, C. Huang, G. Zhang, G. Zhang, H. Li, J. Zhu, J. Chen, J. Chang, et al., Yi: Open foundation models by 01. arXiv:2403.04652.

- Dubey, A. Jauhri, A. Pandey, A. Kadian, A. Al-Dahle, A. Letman, A. Mathur, A. Schelten, A. Yang, A. Fan, et al., The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv:2407.21783.

- Liu, B. Feng, B. Wang, B. Wang, B. Liu, C. Zhao, C. Dengr, C. Ruan, D. Dai, D. Guo, et al., Deepseek-v2: A strong, economical, and efficient mixture-of-experts language model. A: Deepseek-v2; arXiv:2405.04434.

| Domain | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Domain 1 | Wheat OR Triticum OR Triticum aestivum OR Triticum vulgare |

| Domain 1 | germplasm OR gene OR germ OR germplasm OR plasm |

| Domain 1 | heat OR salt OR high-temperature OR drought OR waterlogging yield OR Phenotype Mutant OR QTL |

| Ingredients | Data Extraction Prompt | Data Scoring Prompt |

|---|---|---|

| General instructions | #01 You're an expert in the field of wheat germplasm. #02 Your task is to identify the answer corresponding to the question from the content based on my question and the content I gave. #03 Answers should be concise, use more of my information, and have content that matches my information. |

|

| Format instructions | #01 Not all questions can be answered from the information I have given, if you can't find the answer, just return “Not in Detail”. #02 Each question is returned as a "xxx" triad.(In the case of different types of data, xxx will be replaced with an example of the desired form of output.) |

|

| Task Prompt | question 0 ,What is the main wheat on which research is being carried out in the information given? Direct answer wheat germplasm name. | step 0 ,Calculate the Euclidean distance between all the answers to determine whether most or all the answers are similar. Identify the category with the largest number of answers as 1, identify other categories as 1, and return the results only containing 0 and 1. Example of format: 00110 |

| Typology | Character |

|---|---|

| Agronomic Traits | Coleoptile Color, Seedling Morphology, Plant Height, Plant Type, Panicle Shape, Panicle Length, Panicle Density, Grain Number per Panicle, Thousand Grain Weight, Grain Color, Grain Morphology, Grain Size, Maturity, Growth Period, Tillering Ability, etc. |

| Resistance Traits | Leaf Rust Resistance, Stem Rust Resistance, Root Rot Resistance, Ergot Resistance, Powdery Mildew Resistance, Stripe Rust Resistance, Root Rot and Leaf Blight Resistance, etc. |

| Yield Traits | Yield per Unit Area, Yield per Mu, etc. |

| Other traits | ...... |

| Model | Benchmark(Metric) | Context | ||||

| MMLU | HellaSwag | BBH | GSM8K | MATH | ||

| Command-r-plus-104b | 75.7 | 88.6 | - | 70.7 | - | 128k |

| Qwen1.5-110B | 80.4 | 87.5 | 74.8 | 85.4 | 49.6 | 32k |

| Yi-34B | 76.3 | 87.19 | 54.3 | 67.2 | 14.4 | 200k |

| LLaMA3-70B | 79.5 | 88.0 | 76.6 | 79.2 | 41.0 | 8k |

| Deepseek-v2-236B | 78.5 | 84.2 | 78.9 | 79.2 | 43.6 | 128k |

| Qwen2-70B-instruct | 82.3 | 87.6 | 82.4 | 91.1 | 59.7 | 128k |

| Stage | Large Language Model | temperature |

|---|---|---|

| RGIE block | Command-r-plus-104b | 0.7 |

| Qwen1.5-110b | ||

| Yi-34b | ||

| Llama3-70b | ||

| Deepseek-v2-236b | ||

| Verify block | qwen2-72b-instruct | 0.7 |

| Hardware | Configurations |

|---|---|

| Processors | Intel Xeon*2 |

| Chipsets | Intel C741 |

| Graphics Card | NVIDIA RTX A6000 48G*4 |

| Total Memory | 256GB |

| Storage Type Capacity | 2TB+8TB |

| Frame | Ollama |

| Predicted Value | |||

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Real Value | Positive | TP | FN |

| Negative | FP | TN | |

| Value | Real Situation | Predicted Results |

|---|---|---|

| TP | Abstracts contain the requested extracts | All entities and relationships are extracted correctly |

| TN | Abstracts do not contain the content requested to be extracted | “Not in Detail” |

| FP | Abstracts contain the requested extracts | The amount of data extracted is greater than the amount of data that actually exists |

| Abstracts do not contain the content requested to be extracted | The answer is not “Not in Detail”. | |

| FN | Abstracts contain the requested extracts | “Not in Detail” |

| Evaluation Metrics | Value |

|---|---|

| Precision | 0.8010 |

| Recall | 0.9969 |

| F1 Score | 0.8883 |

| Accuracy | 0.8171 |

| Answer situation | Content of the answer |

|---|---|

| Good | Kazakhstan wheat cultivars/Jimai20, Shannong12/Neimai 8 and II469/…… |

| Bad | The germplasm name is not specified in the text. However, based on your initial statement that I am an expert in the field of wheat germplasm, the wheat germplasm being studied can be referred to as the "Expert's Focused Wheat Germplasm." |

| Types of Text Provided | Wheat and Parental Name Extraction Problems | Trait Extraction Problems | Common Error Types | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Research Subjects | Wheat Germplasm and Parentage Name | Trait Information | |||

| 1 | YES | YES | Correct extraction | Correct extraction | - |

| NO | YES | Extracting the actual research object | Unable to distinguish between trait types | False Positive OR False Negative | |

| YES | NO | correct extraction | Repeatedly extract all triples | False Positive OR False Negative | |

| NO | NO | “Triticum aestivum L.” | Repeatedly extract all triples | Hallucination | |

| 2+ | YES | YES | Unable to judge the most important research subjects | correct extraction | False Positive |

| NO | YES | Extracting the actual research object | Unable to distinguish between trait types | False Positive OR False Negative | |

| YES | NO | Unable to judge the most important research subjects | Repeatedly extract all triples | False Positive OR False Negative | |

| NO | NO | “Triticum aestivum L.” | Repeatedly extract all triples | Hallucination | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).