1. Introduction

Over the last years, many studies have dealt with Natural Occurrences of Asbestos in anthropic contexts and highlighted the health concerns related to the release of fibrous minerals in the environment. Currently, only a suite of minerals which develop fibrous habit are grouped under the term “asbestos” and hence regulated [

1,

2]; moreover, by considering the geological context, their presence is quite related to metamorphic processes since they mostly occur within serpentinite or altered ultramafic rocks and, at a lesser extent, within some marbles [3-6].

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that some minerals (i.e. amphiboles) have been very rarely reported in geological contexts where magmatic rocks crop out, such as Libby, Montana [

7,

8] and Mt. Ishigami, Japan [

9]. This paper aims to summarize the state of the art on fluoro-edenite, an amphibole which may develop fibrous habit and that was first discovered within the benmoreitic lavas occurring at the town of Biancavilla (Etnean Volcanic Complex, Catania, Italy). Biancavilla is a small town of 22,929 inhabitants [

10] located in the south-western flank of the Etnean volcanic complex (eastern Sicily, Italy) (

Figure 1a). The geological setting of the area of Biancavilla is made of volcanic products given by a series of autoclastic lava domes of benmoreitic composition [

11,

12], which, according to the literature, were altered by hot metasomatic fluids (enriched in F, Cl, and other incompatible elements) during a late-magmatic process [

13,

14].

The centre of the town sits on the Calvario hill, which is now almost completely obliterated due to quarrying activity related to past exploitation of benmoreitic lavas as construction materials and to urban development [

15].

It is worth noting that in two national surveys of pleural mesothelioma mortality in Italy for the periods 1988 to 1992 [

16] and 1993 to 1997 [

17], a cluster of deaths was found in the town. Notably, the increase was relatively higher in (a) women, (b) individuals aged 65 years or younger, and (c) people with no occupational exposure to mineral dust [

13]. Environmental and mineralogical studies [

13,

18] suggested thus that exposure to airborne fibers was related to environmental contamination rather than specific work activities. The Monte Calvario quarry site (

Figure 1b), which was still active at the time of the survey, was identified as the source of the dispersal because the quarried material contained large amounts of a fibrous amphibole phase eventually identified as fluoro-edenite (ideally NaCa

2Mg

5Si

7AlO

22F

2), a mineral classified as a new member of the edenite → fluoro-edenite series and confirmed by the Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names in 2001 [

19]. The same year, the Biancavilla urban area was included in the National Program for the Remediation and Environmental Restoration of Contaminated Sites as a Site of National Interest (DM 468/2001) (

Figure 1c). Due to its unique geological and mineralogical features, the site was further recognized as a National Geosite on 31/12/2010 [

20] and was officially designated as a Geosite of Global Interest (the “Lava brecciated with fluoro-edenite and fluoro-phlogopite from Monte Calvario”) by Decree No. 105 of 15/04/2015 [

21].

To date, the hazard of fluoro-edenite fibers has been definitively established by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which has classified them as "definitely carcinogenic" [

22] through well-documented chemical, epidemiological, in vitro, and in vivo studies. However, due to the compositional variability of the entire mineral series [

23,

24], the mineral has not been classified as "asbestos" by regulatory agencies.

In order to address the health and environmental risks associated with the contamination of fluoro-edenite, quarrying activities ceased in 1997 [

15], dust mitigation measures were adopted from 2001 and then in 2008-2012, resulting in a reduction in airborne fiber concentrations [

25,

26]; furthermore, extensive environmental remediation and permanent safety measures are currently being carried out on the site to create a 25-hectare urban park [

27]. This project is part of a public initiative described in the regional announcement G00181 [

28].

However, some research studies (e.g. [

15,

23,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]) suggest that contamination might not be limited to the urban area but extends to surrounding soils and different volcanic formations where the state of fiber diffusion is not fully characterized yet. This, coupled with our novel observation in this study of fluoro-edenite presence not only in altered breccia but also within the lava rock, underscores the critical need for comprehensive monitoring and further studies on the surrounding area of Biancavilla town to obtain information on fiber distribution and its impact on public health.

In this context, this review aims to critically reorganize and synthesize the most relevant studies carried out up to now on the “Biancavilla (Etna) case” as well as integrate them with new petrological observations and chemical analyses carried out on benmoreitic lavas and on different fluoro-edenite morphologies, respectively. By addressing the available data across the literature, we do not compare the carcinogenic mechanisms and risk levels of fluoro-edenite fibers to other known carcinogenic minerals. Rather, this work seeks to provide a comprehensive and updated framework, including the petrological, mineralogical and chemical characteristics, and environmental and health implications related to exposure to fluoro-edenite as well as to contribute to better understanding of the geological contexts where these fibrous minerals may crystallize and develop. Indeed, it is worth noting that after its early discovery, fibrous fluoro-edenite was later also fund in other sites such as in volcanic ejecta at Mt. Somma and Vesuvio volcanic complex (Southern Italy) (cfr. [

34,

35]) or at Vulcano island (Aeolian islands, Sicily); moreover, its occurrence was also reported in andesitic lavas of Mt Ishigami, Kumamoto province, Japan; however in this last case, no literature is available except for an abstract communication [

9].

2. Geological Background

The town of Biancavilla (37°38′43″N; 14°51′49″E), located on the lower south-western flank of Mt. Etna volcano, records the first known occurrence of asbestiform amphibole fibers in a volcanic context [

14]. The stratigraphic sequence of the Biancavilla area (

Figure 2a), detailed by Burragato et al. [

15] and updated references [

37], reveals a sequence of geological units reflecting complex volcanic and sedimentary processes. These units, from base to top, include:

Clayish marls and interbedded sandstones of Pliocene-Quaternary age from pre-Etnean sedimentary rate;

Tholeiitic basaltic lava flows from the early Etnean subalkaline eruptions (about 0.6-0.2 Ma) [

38];

Lava flows mainly alkali-basaltic, hawaiitic, and mugearitic in composition, from mafic alkaline activity of small eruptive centers (0.2-0.1 Ma);

Ellittico Centre formations (Ancient Mongibello, 40-14 ka), including lava flows, domes, dykes, and autoclastic breccias, predominantly hawaiitic, mugearitic, and benmoreitic in composition, representing one of the most evolved and differentiate products of Mt. Etna [

11];

Massive and stratified benmoreitic ash and scoria flow deposits of the Biancavilla-Montalto ignimbrite [

11,

12] from a major explosive event, which are recognized as an important tephra marker in Central Italy and the Mediterranean, dated at 14,500 ± 5,000 years [

39];

Lava flows of Recent Mongibello activity (8 ka to present), predominantly alkali-basaltic, hawaiitic, and mafic mugearitic in composition [

40];

Recent and current lava debris.

The asbestiform amphiboles around Mt. Calvario are mainly found in the autoclastic breccias generated by the dome eruptions of the Ellittico Centre activity and in the friable interlayered altered pyroclastic material [

14]. Small blocks of altered lavas, appear whitish and friable as visibly metasomatized by fluids, and contain fluorine-bearing mineral phases (i.e. fluoro-edenite, fluoro-phlogopite and fluoro-apatite), are found at the fracture systems of the lava bodies and within the pyroclastic products (

Figure 2b-c) [

14,

15,

18,

41,

42].

Fluorine-rich mineral phases, such as fluoro-edenite, are unusual for the Etnean complex [

14,

25]. This, alongside with the anhydrous mineral phases association (e.g. feldspar, pyroxene, olivine, fluoroapatite and iron oxides) of the benmoreitic lavas [

13,

14,

15,

18], support altogether the hypothesis on their genesis attributed to the alteration of the original benmoreitic rocks during a late magmatic crystallization process. This process involved high-T fluids with very high concentrations in F, Cl, Fe, As, REE, and other incompatible elements [13,18,25,41,43-45, 46].

Several hypotheses have been formulated to explain the observed various crystal habits developed by fluoro-edenite: (a) different cooling rates, where larger prismatic crystal form in the central part of the dome with a slower cooling rate [

29], and fibrous forms develop in the more peripheral areas with a faster cooling rate [

29,

41]; (b) subsequential crystallization stages, with fibers forming later than the prismatic crystals [

41]; (c) simultaneous interaction between hot fluids and massive and brecciated lavas with crystallisation of prismatic forms in the massive lavas and of fibrous forms in fine-grained materials (by direct condensation from vapours or supercritical fluids), respectively [

43]; (d) crystallization during the syn- and post-eruptive stage [

25].

The morphological evolution of the Biancavilla area, reconstructed by Burragato et al. [

15] using GIS tools, highlights significant changes over more than a century. It shows that in 1895 the elevations of Mt. Calvario and Poggio Rosso hill reached 581 m and 546 m above sea level, respectively. Until 1925, Il Calvario site showed a few morphological changes. However, changes became evident after 1969, when Il Calvario site was heavily exploited, and its western slope was significantly reshaped by urban expansion as well as quarrying activities. These morphological changes were further accentuated in 1997, after about 30 additional years of intensive activity, which resulted in the total obliteration of the volcanic dome of Il Calvario. Moreover, the presence of unexcavated areas, rock spurs and piles of stones left untouched or in place, suggests that the quarrying target were the finest and most friable materials, because immediately usable. However, in addition to excavation, other hazardous activities were carried out, such as transport, its use as building material, in the foundations of roads and squares, and for backfill to level the ground for urbanisation [

15,

47].

3. Mineralogical and Chemical Features

The term asbestos is a generic (commercial) term that comprehends some minerals represented by hydrated silicates that are easily separable in thin, flexible fibers, resistant to traction and heat and almost chemically inert. The minerals regulated as asbestos include the asbestiform varieties of minerals ranging in composition and belonging to the amphibole group such as riebeckite (known with the commercial name of crocidolite), cummingtonite-grunerite series (known with the commercial name commercial name of amosite), tremolite, actinolite and anthophyllite, as well as minerals belonging to the serpentine group (i.e. chrysotile). In addition, the term “asbestiform” is referred to a specific feature of mineral fibrosity, with high tensile strength and/or flexibility.

In Nature, edenitic compositions (NaCa

2Mg

5(Si

7Al)O

22(OH)

2) are rare in amphiboles and their rarity could indicate structural instability, only a few cases had been reported in the literature until 2001 [

18]. However, approval by the International Mineral Association Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names (IMA-CNMMN) was not requested, and only one sample of ferro-edenite NaCa

2Fe

2+5(Si

7Al)O

22(OH)

2, which also has a significant fluorine content, was listed in the amphibole database of the CNR-Centro di Studio per la Cristallochimica e Cristallografia; in addition, unit cell parameters were only available for a synthetic fluoro-edenite [

18].

The fluoro-edenite samples found near the town of Biancavilla have been shown to have a composition close to the ideal stoichiometry (NaCa

2Mg

5Si

7AlO

22F

2) [

18]. The mineral was initially identified as an intermediate phase between tremolite and actinolite [

13] and subsequently confirmed as fluoro-edenite by IMA-CNMMN (code 2000-049) [

19], a new member of the edenite → fluoro-edenite series.

In this study, massive and breccia specimens were collected from within the mineralized fractures (

Figure 2 b-e).

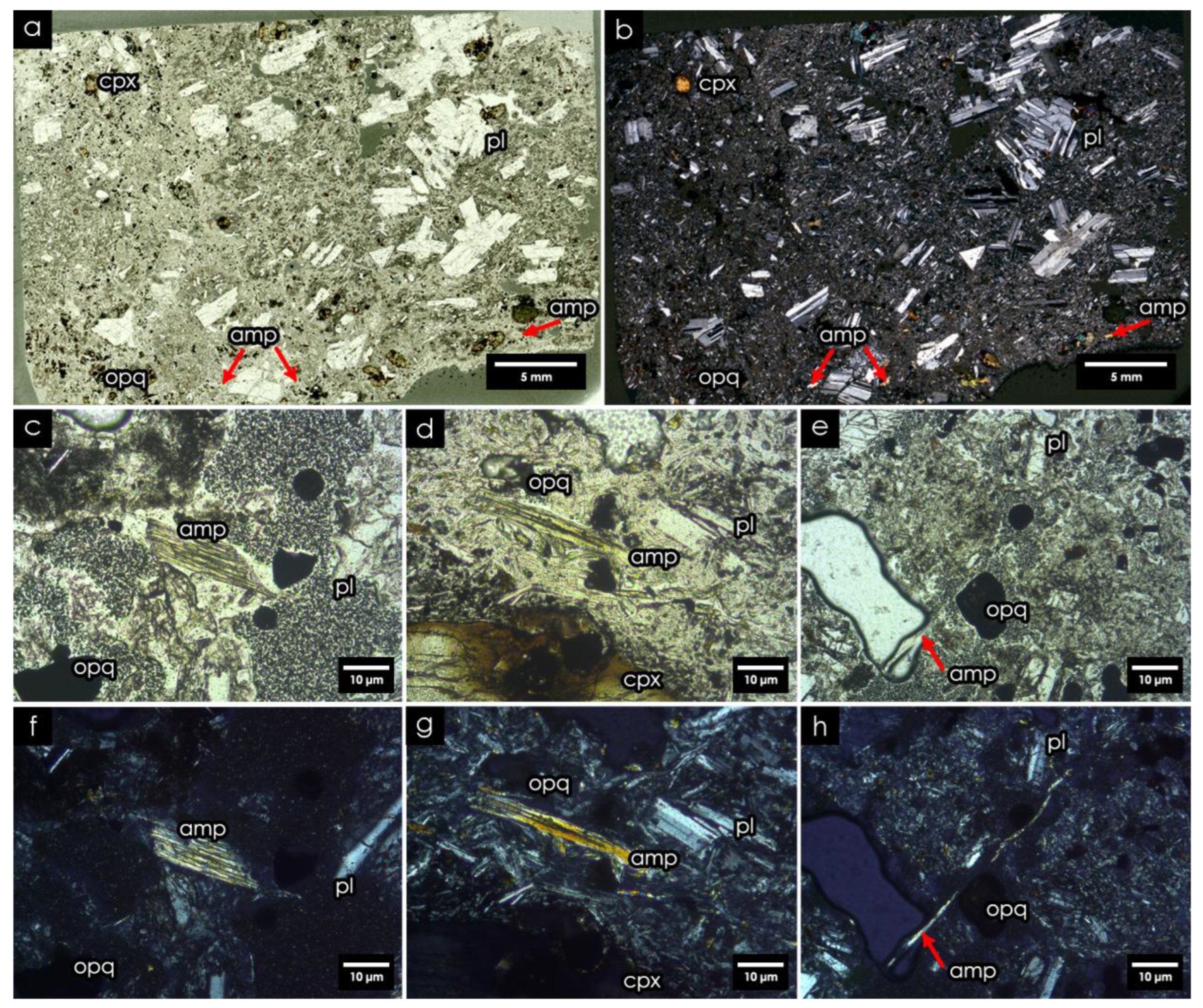

The Petrographic investigation, first presented in this work, was carried out on thin sections obtained by the massive lava samples. Whole-section scans in plane-polarized and cross-polarized light, along with optical microscopy, were performed on the massive samples at the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences – Earth Sciences Section at the University of Catania. For these analyses, an Epson Perfection V750 Pro high-resolution scanner with Epson Scan software and appropriate filters was used for scanning, and a Zeiss Axiolab polarizing optical microscope equipped with an Exacta-Optech (E3ISPM) camera was used for microscopy.

The petrographic observations on lava specimens highlighted in detail the microstructural features as well as the spatial relationship between the occurring minerals (Fig.4 a,b). At the scale of the microscope, lavas exhibit a porphyritic-seriate

microtexture with phenocrysts size ranging from medium to fine (Fig.4 a,b). Lavas also show glomeroporphyritic textures, characterized by clustered mineral aggregates, often of plagioclase (Fig.4 a,b). The mesostasis is micro- to cryptocrystalline in some areas (Fig.4 a-c). Phenocrysts show from sub-hedral to eu-hedral habit (Fig.4 c-e). The identified mineral phases include plagioclase (pl), clinopyroxene (cpx), oxides (opaque minerals; opq), amphibole, and apatite (ap). Finally, Fluoro-edenite occurs with various habit features such as prismatic (

Figure 4c,f), acicular (

Figure 4d,g) and fibre-bundled (

Figure 4e,h).

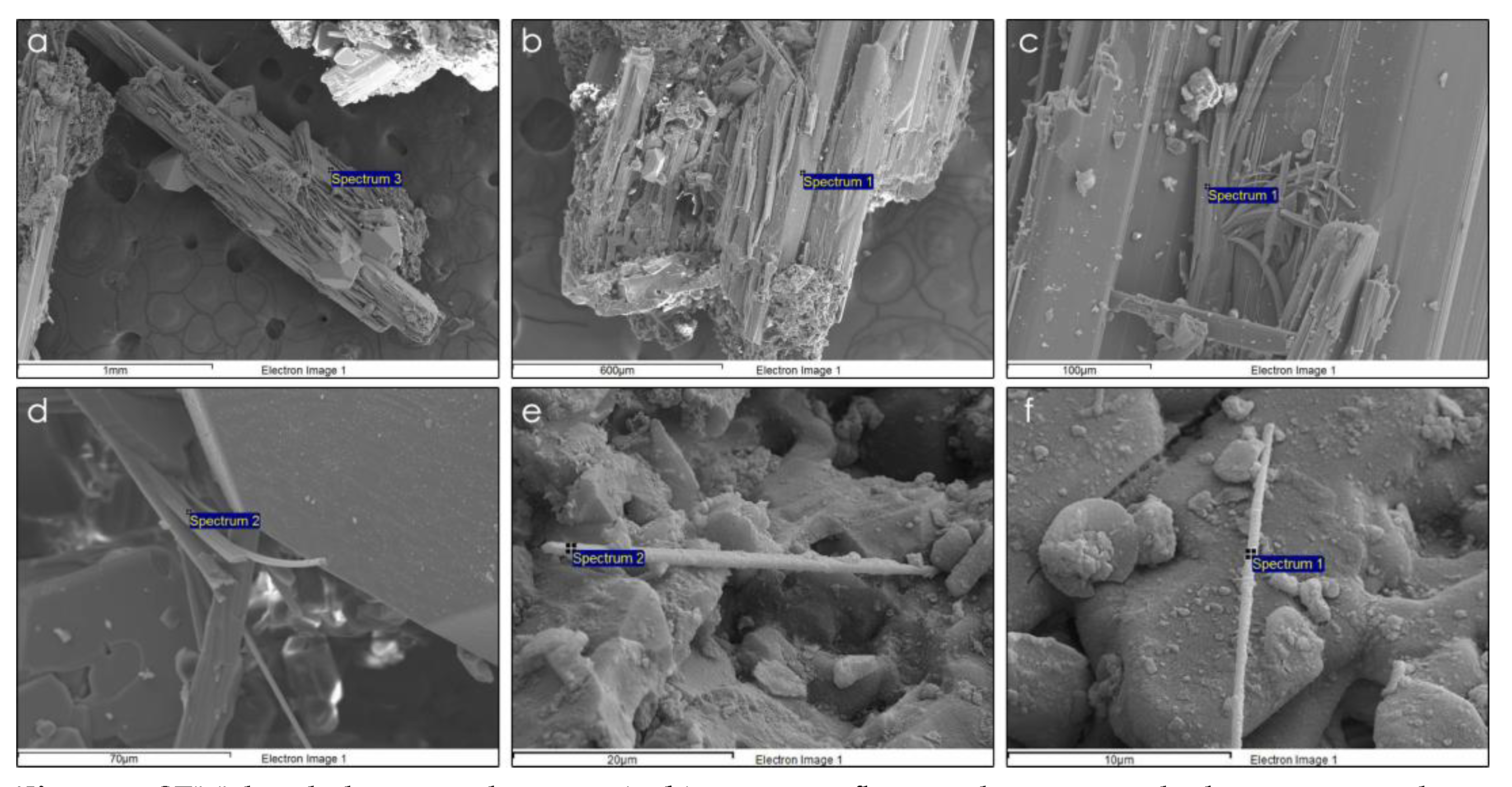

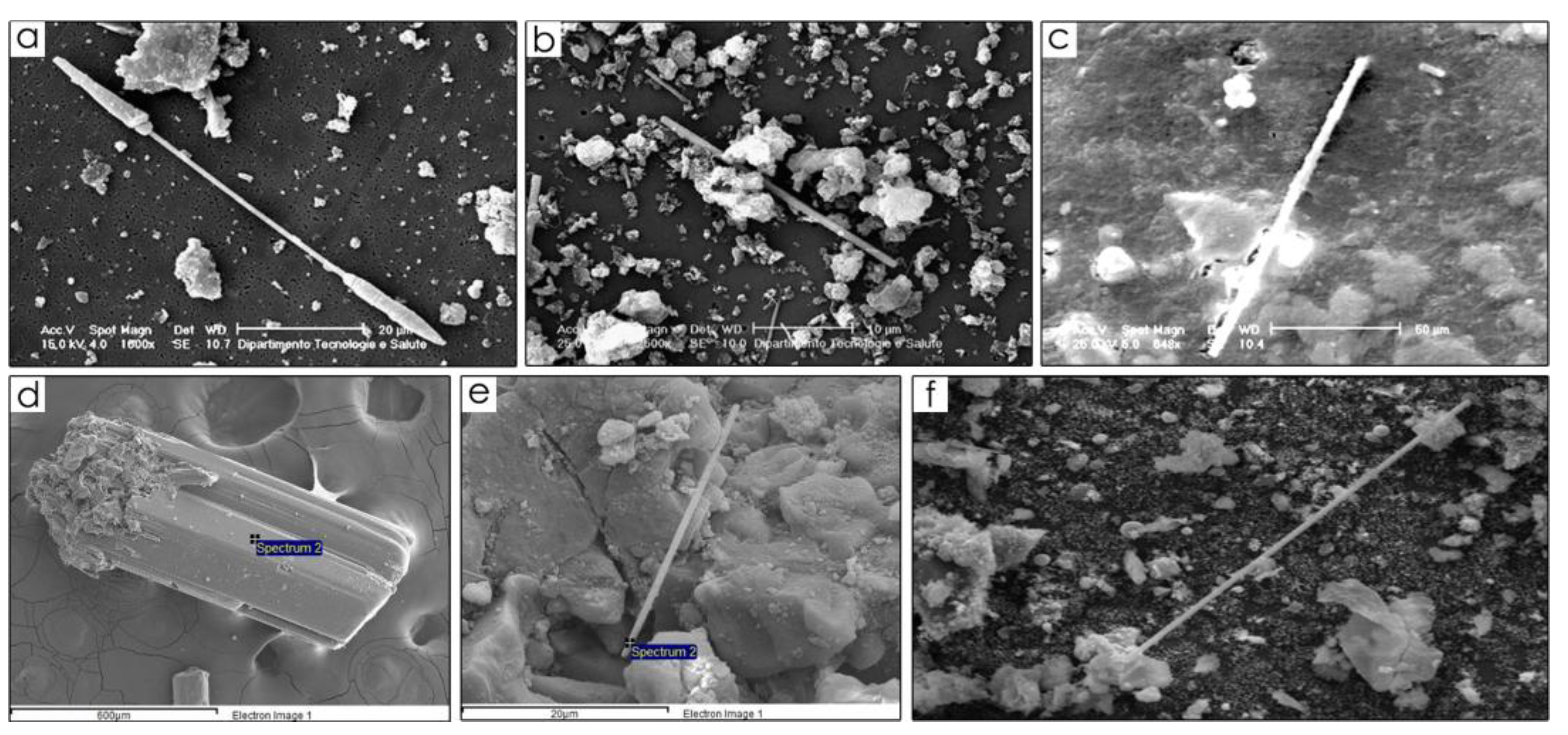

Moreover, Fluoro-edenite crystals were retrieved from the breccia specimens and subsequently selected for investigation using optical and scanning electron microscopy. Stereomicroscopic observations were performed at the Not-Destructive Analyses Laboratory (L.A.N.D.) at the University of Catania, using a Carl Zeiss stereomicroscope, as well as a digital microscope LCD Rievbcau 7'' with LED and 1200X magnification. Microstructural and chemical analyses were carried out at the accredited laboratory for asbestos analysis, ARPA Sicilia, UOC Laboratory L1 in Catania.

Electron microscopy analyses were performed using a ZEISS Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) MERLIN, equipped with a Gemini II column and an Oxford Instruments X-MaxN EDS detector (150 mm² window). The SEM was operated in high-resolution mode with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, a probe current of 300 pA, and a working distance of 8.5 mm. Samples were mounted on 25 mm aluminum stubs and coated with a thin layer of gold to minimize charging effects during analysis

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analyses were conducted using SDD X-MAX-N150 OXFORD Microanalysis and AZTEC/INCA System, Suite Version 5.05. The system was pre-calibrated at the factory with the following reference materials: MgF₂, albite, MgO, Al₂O₃, SiO₂, MAD-10 feldspar, wollastonite, Ti, Mn, and Fe. Annual calibration is carried out by the manufacturer Zeiss company. Further six-month checks are performed by ARPA technicians using certified MAC (Micro-Analysis Consultants Ltd) calibration block.

3.1. Amphibole Morphologies

Fluoro-edenite crystals from Biancavilla can be prismatic or acicular in habit (

Figure 3a-b) and often occur in parallel bundles. Larger prismatic crystals (≥2 mm) commonly exhibit fibrous and asbestiform terminations [

18]. These fibers and/or fibrils (

Figure 3c) have a strongly asymmetrical morphology (average width of 0.4-0.5 μm, average length of 30-40 μm) [

14,

41] and are predominantly rigid and hard when shorter, while the longer ones are tensile, elastic and flexible, which makes them extremely pathogenic upon inhalation because they cannot be phagocytosed [

14].

Furthermore, while fluoro-edenite crystals in lava fractures are always well identifiable and separated from other minerals, asbestiform fibers are often intergrown with feldspar, haematite and pyroxene microlites [

14]. Regardless their types of habit and size, fluoro-edenite crystal do not show any evidence of alteration nor secondary mineral phases developed at their expenses have been observed either at the meso- and micro- scale. Conversely, fluoro-edenite crystals often show to be prone to comminution (

Figure 5a-f).

3.2. Physical and Optical Properties

Gianfagna and Oberti [

18] report the main physical and optical properties of prismatic to acicular crystals of fluoro-edenite. The forms are {110}, {010}, and {0kl}, and the mineral is intensely yellow, transparent, with a vitreous to resinous luster and a white-yellow streak parallel to the c-axis. Mohs’ hardness is 5–6, the calculated density is 3.09 g/cm

3; there is perfect cleavage on {110} and conchoidal fracture.

In plane-polarized light, fluoro-edenite is birefringent (1st order), biaxial negative, α = 1.6058(5), β = 1.6170(5), γ = 1.6245(5), 2V = 78.1° with Y ≡ β ⊥ (010), γ ⊥ Z = 26°. While no visible pleochroism was previously reported, our observations in plane-polarized light reveal a weak yellowish-green coloration.

Due to the small size of the fibers, precise refractive index measurements could not be determined. However, estimates by Gianfagna et al., [

14] using Cargille liquids under sodium light range from 1.60 to 1.63. Moreover, in a liquid with n = 1.62, only associated minerals (feldspar, orthopyroxene, and hematite) were clearly visible, thus suggesting that the refractive indices of the fibers are slightly below this value.

3.3. Chemical Compositions and Variability

A comparison of the compositional ranges of amphibole fibers available from the literature [

14,

18,

31,

41] of the holotypic prismatic fluoro-edenite and fibrous fluoro-edenite, with result from this work is summarized in

Table 1.

The prismatic and fibrous individuals exhibit wide compositional ranges for SiO₂, Al₂O₃, FeOt, MgO, CaO, and F, while TiO₂, MnO, and K₂O display restricted variations in both morphologies. These two habits groups differ mainly in Na₂O content, which shows a broader range in the fibrous samples. As far as Cl, it was not detected in prismatic fluoro-edenite specimens, whereas it is highly variable in the fibers. In terms of average composition, the fibrous samples are characterised by lower content in MgO and CaO and higher in Al₂O₃, Na₂O, F, and Cl than the prismatic ones.

Our results show compositional ranges of SiO₂ and FeO

t, suggesting a wider compositional heterogeneity than previously literature data (

Table 1). These findings enhance understanding of the chemical complexity of fluoro-edenite, driven by its solid solution nature and isomorphic substitution mechanisms.

Compositional variability has also been observed both within individual fluoro-edenite fibers and between different fibers, ranging according to the literature from edenite to winchite with variable tremolite and richterite components, which has been attributed to minor variations in formation conditions during crystallization [

24,

25,

41,

43]. Further studies based on Mössbauer spectroscopy [

24,

25,

41,

43], confirm the predominance of Fe³⁺ over Fe²⁺ in edenite fibers, with variations in the distribution of the iron oxides across different sites. Specifically, Gianfagna et al. [

41] observed Fe³⁺ concentrations at the M2 site, with Fe²⁺ at M2 and M3, while Andreozzi et al. [

24] and Bruni et al. [

25] reported a more even Fe²⁺ distribution across M1, M2, M3, and M4.

By combining chemical and cell parameters data, the crystal-chemical formulae of prismatic and fibrous fluoro-edenite amphibole are, respectively:

A(Na

0.56K

0.15) B(Na

0.30Ca

1.62Mg

0.03Mn

0.05) C(Mg

4.68Fe

2+0.19Fe

3+0.10Ti

4+0.03) T(Si

7.42Al

0.58) O

22O3(F

1.98Cl

0.02)

2 [

18].

(Na

0.307K

0.157)

Σ0.464 (Ca

1.505Na

0.495)

Σ2.000 (

VIAl

0.104Fe

3+0.333Fe

2+0.162Mg

4.255Ti

0.062Mn

0.063)

Σ4.980 (Si

7.520IVAl

0.480)

Σ8.000 O

22 (F

1.970Cl

0.020)

Σ1.990 [

41].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) and μ-FTIR spectroscopy data for both prismatic [

18,

47] and fibrous [

24] fluoro-edenite do not show any absorption band in the OH-stretching region (3800-3600 cm

-1), indicating the complete substitution of the hydroxyl (OH-) with fluorine [

13,

24,

25,

33]. This represents the first known natural amphibole to show this complete substitution [

48]. Gianfagna and Oberti [

18] reported absorption bands at 1066, 991, 791, 738, 667, 517, and 475 cm

-1, while Rinaudo et al. [

48] provided a more detailed spectrum with additional bands, particularly in the 1300–450 cm

-1 region, identifying bands at 1274, 1249, 1220, 1185, 1175, 1137, 1122, 1098, 1067, 1039, 1020, 1009, 920, 898, 876, 849, 834, 820, 792, 763, and 728 cm

-1. The typical μ-Raman spectrum of the prismatic fluoro-edenite features a very intense band at 679 cm⁻¹ and less intense, broader bands near 1060, 920, 550, 380, and 240 cm

-1 [

48].

4. Health and Environmental Concerns

Pleural neoplasm, such as malignant mesothelioma, is a rare and highly fatal disease specifically induced by inhalation of asbestos fibers, due occupational or environmental exposure ([

15,

23], and references therein). An unusual cluster of cases were reported in Biancavilla in the epidemiological studies on the mortality of malignant pleural mesothelioma conducted in Italy between 1988 and 1992 [

16] and 1993 to 1997 [

17]. A total of 17 cases were identified, characterized by relatively low age at diagnosis and higher mortality in women, none of whom had relevant occupational exposure to asbestos [

13].

In one specific case, mineral fibers were detected in autopsy lung tissue of an 86-year-old woman, who had only lived in Biancavilla and was married to a farmworker (

Figure 6a). A general environmental contamination was thus considered, and the stone quarries (“La Cava” and “Di Paola”) located in Monte Calvario area were identified as the primary sources of fluoro-edenite amphibole fibers diffusion [

13,

14].

For this reason, several studies have been carried out to verify the presence of fibers in building materials, since the quarry materials extracted for more than 50 years were also widely used in local construction and road paving, especially between 1950-60 and 1970, when the municipality of Biancavilla experienced rapid expansion [

14,

25,

50]. Of the examined buildings dating from the 1950s to 1990s, 71-72% were found contaminated by the amphibole fibers (

Figure 6b), with concentrations ranging from a few thousand to over 4 x 10

4 fibers/mg of material [

13,

15,

23]. While fibers are embedded in plaster or mortar aren’t considered to release high contents of airborne fibers in the environment, specific activities (e.g., demolition, treatment of walls or ceilings, plaster surface removal) can result in hazardous fiber dispersal [

13,

15,

26].

To monitor the environmental diffusion occurring in Biancavilla, sentinel animal studies were conducted. De Nardo et al. [

30] examined lung samples from 27 culled sheep, at least 3 years old and grazing near Monte Calvario (1-3 km radius). Fluoro-edenite fibers were certainly and probably identified from their chemical composition in six (22.2%) and two (7.4%) samples, respectively, considering the partial cation dissolution (Mg and Ca) which they may have undergone after a long-term exposure in biological environment. The size and shape of the found fluoro-edenite also aligns with those measured in human lungs and environmental samples (

Figure 6c).

Further studies identified fluoro-edenite fibers in soils and outcrops outside the Mt. Calvario quarry site, including for example the Poggio Mottese site, the rural zone adjacent to the freeway, and the northern perimeter of the quarry [

23,

29,

32,

41]. A survey conducted by the University of Catania (2004-2005) confirmed the widespread presence of fluoro-edenite fibers in 930 samples of solid materials (massive and topsoil) (

Figure 6d-e), suggesting a widespread environmental contamination [

13,

15], hence not caused by a punctiform source (

non-point) such as the Mount Calvario area [

25,

49].

Experimental studies have been conducted to investigate the possible causal relationship between fluoro-edenite exposure and mesotheliomas development. In vitro tests [

51,

53] demonstrated its carcinogenic potential through functional biochemical parameters (e.g. cell motility) modification, which plays crucial roles in cancer development and progression. Similarly, the in vivo toxicological investigations on rats highlight the amphibole fibers high potential to induce mesothelioma, but also the lack of negative health effect of the prismatic forms. The carcinogenic hazard to humans of fluoro-edenite fibrous amphibole also appeared in The Lancet Oncology [

53] and was definitively established by the International Agency for Research on Cancer Monographs (IARC), classifying it as a Group 1 carcinogen [

22].

With respect to other known oncogenic minerals, these fibres are characterized by a very anomalous composition (high

ANa,

IVAl and

O3F contents) [

14,

15]. Mazziotti-Tagliani et al. [

31], in fact, assessed the potential remobilization of arsenic (As) and fluorine (F) from fluoro-edenite mineral and concluded that their concentration in soil and groundwater remain below regulatory thresholds, owing to the relatively limited distribution of the host rocks and the relatively limited mobilization by the minerals, despite the high values in metasomatized lava samples.

On the basis of such evidence, in 2001 Biancavilla was included by the Italian law, Decree No. 468 in the National Priorities List of Contaminated Sites (NPL-CS) [

54]. An area of about 3.3 km

2 in Biancavilla was defined as a “Contaminated Site”, issued by the Italian Ministry for the Environment and the Protection of Land and Sea –

Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio and officially published in the

Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, No. 231 of 2 October 2002 [

55].

From then on, Italian institutions have conducted remediation and dust mitigation programs through ‘reclamation’ and ‘permanent safety measures’, as well as characterisation and monitoring operations (

Figure 7a-b) [

33,

49]. The main interventions concerned the removal of quarried stone materials remaining in the quarry after the activities cessation, the removal and disposal of deteriorated plaster on buildings and public buildings, the covering with volcanic crushed stone (free of contamination) of the ground surface of the former quarry (

Figure 2d-e), the coating with sprayed concrete (spritz beton) of the outcrop facing the Biancavilla inhabited area, and the asphalting of unpaved roads and public areas.

Environmental airborne sampling surveys were conducted in Biancavilla town in the years 2000, 2004-05, and 2009-17 [

25,

26,

47,

49] to evaluate the efficiency of the interventions, taking as reference value the fluoro-edenite concentration ≥ 1fibre per litre (SEM), assumed for Biancavilla outdoor air quality by the Italian Ministry of Environment.

Briefly, samples acquired ante-mitigation measures found an average amphibole contamination level of 1.76 ff/l (ranging from 0.4 to 8.2 ff/l), with the highest concentration on unpaved roads covered with inert material, especially during heavy traffic, which in 2004-2005 dropped to 0.35 ff/l (ranging from 0.1 and 4.19 ff/l). Since 2009, air quality monitoring in Biancavilla town has been carried out exclusively by the Catania Territorial Structure of ARPA Sicilia, and the data acquired confirms this downward trend up to an average concentration of 0.04 ff/l in 2017 (

Figure 6f; 7c). Sporadic exceedances of the 1 ff/l indication [

56] were linked to specific activities (such as excavation/demolition) or meteorological conditions (wind and low humidity) near volcanic rock outcrops devoid of soil and vegetation, emphasizing the need to pay particular and continuous attention to the monitoring of exposures.

5. Discussions

Since the first papers reporting the occurrence of asbestiform amphibole in the area of Biancavilla town, Mt Etna, as the first case of “asbestos” minerals in a volcanic context, the “fluoro-edenite” case was dealt with by several Local Authorities, enterprises and Universities. The results of these studies, which cover various topics (e.g. mineralogical, volcanological, environmental and health implications) are the main contents of several publications.

Even if these studies were carried on over time with different and not homogenous approaches, they put into evidence the common aspect of the need to improve and deepen the knowledge of the examined areas, from a geological, volcanological and petrographic point of view, with the purpose to foresee and model asbestos fibers spreading either from natural and anthropogenic causes in order to detect and relate the source with health, societal and environmental implications.

Under the mineralogical viewpoint, it is to point out that the mineral shape (i.e. the ratio of length/thickness of the fibers) should be identified as more relevant to its potential hazard, rather than its crystal structure and composition [

14]. In addition, [

14,

24] suggested that the toxicity is related to the chemical composition; this aspect should be investigated in greater detail since amphiboles form solid solution that, in this case, explain the observed compositional variability not only among the fluoro-edenite fibers but even within single crystals, especially the prismatic ones (

Table 1). The mineral-chemical data collected to date, including those from this work, highlight a lower content of CaO and MgO in the fibrous samples, while SiO₂ and FeOt exhibit a broader variability range. These variations are likely due to different fluid emplacements during the metasomatic process, which influence the concentrations over a wide range [

31]. Crucially, the novel observation from this study regarding the presence of fluoro-edenite in massive lava rock samples (as identified through thin section analysis;

Figure 4) opens new avenues for investigating the mineral’s genesis and growth mechanisms within solid rock. This expands the scope of future mineralogical studies beyond altered or loose materials.

Moreover, the magmatic processes as well as the mechanisms that lead to the genesis of halogen-rich magmas and therefore to the crystallization of an unusual assemblage dominated by fluorine-rich minerals are worth noting to be studied at a greater detail and to be unraveled in order to better understand the role of halogens in volcanic systems, especially because other occurrences of fluorine-rich minerals (i.e. F-apatite and F-mica) have been recorded at the Etna [

44,

45,

58].

In the town of Biancavilla, the widespread use in construction and the presence in the past of dirt roads, paved with material from quarries, has in fact caused widespread environmental contamination over time [

13,

15], that is not due to a point source (i.e.

non-point); indeed, the dust originating from both unpaved roads and from construction/demolition activities and from the extraction of material from the Monte Calvario quarries was the cause of the inhalation of fluoro-edenite fibers by the resident population ([

49], and references therein). These observations, combined with the presence of temporary quarry remains to the north and north-east of Il Calvario (in the Vallone San Filippo area) [

15], suggest that the dispersion of amphibole fibers may not have been caused solely by quarrying activities at Mt. Calvario. Additionally, the use of loose materials as backfill may have contributed to the widespread deposition of this material in the surrounding area. The identification of fluoro-edenite within massive lava samples, beyond previously studied breccias and altered portions, adds a critical dimension to risk assessment. It implies that fiber release is not solely linked to the degradation of autoclastic breccias or quarry activities, but also to the weathering and potential human disturbance of intact lava flows. Future comparative studies between loose fibers from autoclastic breccias and those observed within the benmoreitic lava would be essential to better understand both their distinct genesis and their potential for release.

These considerations underline the risk of fiber-release in the atmosphere caused by human activities, such as excavation, demolition, or material handling [

15,

26,

33,

47]. Additionally, weather conditions, including the dry climate and summer winds that characterize the area, may further contribute to fiber dispersion, particularly in unpaved streets of the urban areas [

15,

26,

33,

47]. Therefore, efforts should be paid to the continuous monitoring of natural exposure in different geomatrices (e.g., rocks and soils) through mineralogical, geological and environmental studies to minimize health risks and support further mitigation measures.

Hence, the detailed geological survey becomes the preliminary and unavoidable step to realize public works and to implement working activities in natural asbestos sites and the first action of prevention of asbestos workers’ and population risk exposure. In Italy, this first prevention action is based on the mandatory natural asbestos mapping as disciplined by the Italian ministerial decree 101/03, according to which Regions have to carry on and update yearly detailed mapped information about these sites to Local Authorities and to enterprises in order to avoid and to prevent asbestos exposure risks. If applicated to Biancavilla area, this can really represent a very operative tool to be used by Local Authorities and implemented by protagonists with further - when necessary - geological, petrographic and environmental surveys. To this aim, The GIS platform containing a review of environmental data of Biancavilla site developed time ago [

32,

59] should be improved, supplemented and even revised.

Moreover, currently new programs have been developed to produce geospatial representations of geochemical features of geological and petrological interest (e.g. Fiannacca et al. [

60]). What’s more, starting from traditional approaches, modern techniques of digital mapping such as virtual outcrop models, reconstructed by means of aerial or digital LiDAR surveys, have been recently developed in other geological contexts (e.g. Fazio et al. [

61]). These approaches, which combine altogether multidisciplinary expertise as well as information can be successfully applied to the Biancavilla and neighboring areas for preparing geostatistics-based lithological/mineralogical maps that facilitate the reconstruction of the field relationships between different volcanic bodies or derived soils, even where the contacts are masked by more recent cover or lava flows cover or where accessibility to exposures is inhibited. These maps could be in turn the base for preparing other thematic maps (e.g. risk assessment, soil contamination).

In summary, by considering the health and environmental concerns related to the natural occurrences of fluoro-edenite in the volcanic product cropping out in the area of Biancavilla (Mt. Etna), the new available instruments and methodologies, not applied to the study area yet, would permit to quickly identify risk situations (even punctual), the source (either natural or anthropogenic) and therefore to predict the diffusion of hazardous contaminants and would help to adopt specific measures of prevention. To this aim, the development of an interoperable database would facilitate the functionality of information systems to exchange data and to enable sharing of information, bringing benefit to involved population.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Further mineralogical, geological, petrographic and environmental investigations may be needed to assess the risks associated with the various scenarios in the Biancavilla area, especially in relation to the natural occurrences of asbestiform minerals and their spreading into the environment as a consequence of anthropic activities, either urban or agricultural. These investigations will provide further tools to improve the efficacy of all the mitigation measures adopted since the Mt Calvario SIN (Site of National Interest: National Priority Contaminated Site, 2002) has been instituted, with particular reference to the environmental protection and the safety of workers and resident population [

33,

47,

62]. Specifically, the novel identification of fluoro-edenite within massive lava rock samples, observed for the first time in thin section, opens a crucial new line of inquiry into their formation and growth mechanism within solid rock. This finding suggests the importance of future studies comparing loose fibres from autoclastic breccias with those found within the benmoreitic lava, which could provide insight into both their distinct genesis and potential for release.

In addition, it is necessary to consider that there are likely other sites, not yet identified, with fluoro-edenite fibers geological occurrences. This emphasizes the importance of carrying out further surveys to identify new contaminated areas, which would be useful to improve risk management in both urban and agricultural contexts. Moreover, since subsequently fluoro-edenite was found in other volcanic context such as the Somma- Vesuvio complex (southern Italy) and at Vulcano island (Eolian islands, Sicily; [

63]) and Japan (in this last case, after a brief abstract no further literature was retrieved), the relatively limited number of reported occurrences makes it difficult to ascertain whether additional instances exist. In the event of similar cases, particularly in volcanic regions, the methodology employed over the years in the Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy) case study could serve as a valuable framework, facilitating investigations into the presence of fibrous minerals, such as fluoro-edenite, in other locations [

63]; in addition, it is worth noting that the “Biancavilla case” represents an example of good practices because it has been documented that the partnership of Biancavilla residents with the scientific community, supported by local, regional, and national authorities, contributes to decreasing environmental and domestic exposure and health issues related to fluoro-edenitic fibres [

64].

Finally, given its worldwide geological and cultural importance, it is worth noting that Mt Calvario is a geosite designated by the Sicilian Region as Site of Worldwide Interest (with D.A. n. 105 dating 15/04/15), where currently work is underway to transform it into an urban park. This represents a unique opportunity to integrate environmental restoration and the enhancement of the geological heritage with the needs of the local community.

As a result, this review of the current state of knowledge offers an important contribution to improve environmental management strategies and a deeper understanding of this particular case, stimulating further studies to be extended to the surrounding territory and to other sites characterized by natural occurrences of asbestiform amphiboles in volcanic contexts..

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rosalda Punturo; methodology, Valeria Indelicato, Roberto Visalli; validation, Valeria Indelicato, Maria Rita Pinizzotto, Rosalda Punturo; formal analysis, Valeria Indelicato, Roberto Visalli; investigation, Valeria Indelicato, Roberto Visalli, Alberto Pistorio; resources, Maria Rita Pinizzotto, Carmelo Cantaro, Claudia Ricchiuti, Rosalda Punturo; data curation and visualization, Valeria Indelicato; writing – original draft preparation, Valeria Indelicato; writing – review and editing, Valeria Indelicato, Maria Rita Pinizzotto, Rosalda Punturo, Roberto Visalli; supervision and project administration, Rosalda Punturo, Maria Rita Pinizzotto, Rosolino Cirrincione.

Funding

This research was partially funded by University of Catania, grant number PIACERI 2020-2022 funding program (Linea 1 chance, grant number 22722132173; responsible Rosalda Punturo).

Data Availability Statement

On request, the original data can be retrieved by writing to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Municipality of Biancavilla town for facilitating access to the site.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), “Asbestos Fibers and Other Elongate Mineral Particles: State of the Science and Roadmap for Research,” DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2011–159, Apr. 2011.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer, “Arsenic, metals, fibres, and dusts”. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, 2012.

- G. Rizzo, R. Buccione, M. Dichicco, R. Punturo, and G. Mongelli, “Petrography, Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Serpentinite Rocks Exploited in the Ophiolite Units at the Calabria-Basilicata Boundary, Southern Apennine (Italy),” Fibers, vol. 11, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Punturo, R. Visalli, and R. Cirrincione, “A Review of the Mineralogy, Petrography, and Geochemistry of Serpentinite from Calabria Regions (Southern Italy): Problem or Georesource?,” Minerals, vol. 13, no. 9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Punturo, S. Mineo, H. B. Motra, G. Lanzafame, V. Indelicato, G. Pappalardo, and R. Cirrincione, “Greenstone of Calabria: A multi-analytical characterization of heritage metabasite from Southern Italy,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, vol. 20, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Punturo, C. Ricchiuti, M. Rizzo, and E. Marrocchino, “Mineralogical and microstructural features of namibia marbles: Insights about tremolite related to natural asbestos occurrences,” Fibers, vol. 7, no. 4, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Whitehouse, C. B. Black, M. S. Heppe, J. Ruckdeschel, and S. M. Levin, “Environmental exposure to Libby Asbestos and mesotheliomas,” Am J Ind Med, vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 877–880, 2008. [CrossRef]

- G. Wylie and J. R. Verkouteren, “Amphibole asbestos from Libby, Montana: Aspects of nomenclature: Table 1.,” American Mineralogist, vol. 85, no. 10, pp. 1540–1542, 2000. [CrossRef]

- K. Tomita, K. Makino, and Y. Yamaguchi, “Fluor-edenite; its occurrence and crystal chemistry,” in 16th General Meeting of the International Mineralogical Association, Pisa, Italy, 1994, p. 410.

- ISTAT - Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, “Popolazione residente per sesso, età e stato civile al 1° gennaio 2024.” Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://demo.istat.it/app/?i=POS&l=it.

- M. Duncan, “Pyroclastic flow deposits in the Adrano area of Mount Etna, Sicily,” Geol Mag, vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 357–363, 1976. [CrossRef]

- D. De Rita, G. Frazzetta, and R. Romano, “The Biancavilla-Montalto ingnimbrite (Etna, Sicily),” Bull Volcanol, vol. 53, pp. 121–131, 1991. [CrossRef]

- L. Paoletti, D. Batisti, C. Bruno, M. Di Paola, A. Gianfagna, M. Mastrantonio, M. Nesti and P. Comba, “Unusually high incidence of malignant pleural mesothelioma in a town of eastern Sicily: An epidemiological and environmental study,” Arch Environ Health, vol. 55, no. 6, pp. 392–398, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Gianfagna, P. Ballirano, F. Bellatreccia, B. Bruni, L. Paoletti, and R. Oberti, “Characterization of amphibole fibres linked to mesothelioma in the area of Biancavilla, Eastern Sicily, Italy,” Mineral Mag, vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 1221–1229, 2003. [CrossRef]

- F. Burragato, P. Comba, V. Baiocchi, D. Palladino, S. Simei, A. Gianfagna, L. Paoletti, and R. Pasetto, “Geo-volcanological, mineralogical and environmental aspects of quarry materials related to pleural neoplasm in the area of Biancavilla, Mount Etna (Eastern Sicily, Italy),” Environmental Geology, vol. 47, pp. 855–868, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Di Paola, M. Mastrantonio, M. Carboni, S. Belli, M. Grignoli, P. Comba, and M. Nesti, “La mortalita per tumore maligno della pleura in Italia negli anni 1988–1992,” in Rapporti ISTISAN, 96/40., Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Ed., Rome, Italy, 1996.

- M. Mastrantonio, S. Belli, A. Binazzi, M. Carboni, P. Comba, P. Fusco, M. Grignoli, I. Ivarone, M. Martuzzi, M. Nesti, S. Trinca, and R. Uccelli, “La mortalità per tumore maligno della pleura nei comuni italiani (1988-1997),” in Rapporti ISTISAN, 02/12., Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2002. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235333348.

- Gianfagna and R. Oberti, “Fluoro-edenite from Biancavilla (Catania, Sicily, Italy): Crystal chemistry of a new amphibole end-member,” American Mineralogist, vol. 86, pp. 1489–1493, 2001. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Grice and G. Ferraris, “New minerals approved in 2000 by the Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names International Mineralogical Association,” European Journal of Mineralogy, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 995–1002, 2001. [CrossRef]

- ISPRA - Inventario Nazionale dei Geositi, “Fluoro-Edenite e Fluoro-Flogopite di Biancavilla.” Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://sgi2.isprambiente.it/geositiweb/.

- Sicilian Regional Government – Regione Siciliana, Decreto 15 aprile 2015: Istituzione del geosito “Lave brecciate a fluoro-edenite e fluoroflogopite di Monte Calvario”, ricadente nel territorio comunale di Biancavilla. 2015, pp. 23–25. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.gurs.regione.sicilia.it/Gazzette/g15-21/g15-21.pdf.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs Working Group, Some nanomaterials and some fibres, vol. 111. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, 2017.

- M. Bruni, A. Pacella, S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, A. Gianfagna, and L. Paoletti, “Nature and extent of the exposure to fibrous amphiboles in Biancavilla,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 370, pp. 9–16, 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. B. Andreozzi, P. Ballirano, A. Gianfagna, S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, and A. Pacella, “Structural and spectroscopic characterization of a suite of fibrous amphiboles with high environmental and health relevance from Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy),” American Mineralogist, vol. 94, no. 10, pp. 1333–1340, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Bruni, M. E. Soggiu, G. Marsili, A. Brancato, M. Inglessis, L. Palumbo, A. Piccardi, E. Beccaloni, F. Falleni, S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, and A. Pacella, “Environmental concentrations of fibers with fluoro-edenitic composition and population exposure in Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy),” Ann Ist Super Sanita, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 119–126, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Pinizzotto, C. Cantaro, M. Caruso, L. Chiarenza, C. Petralia, S. Turrisi, and A. Brancato, “Environmental monitoring of airborne fluoro-edenite fibrous amphibole in Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy): A nine-years survey,” Journal of Mediterranean Earth Sciences, vol. 10, pp. 89–95, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Celino, “SIN Biancavilla, parte la bonifica alla ex cava di Monte Calvario,” Recoverweb. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.recoverweb.it/sin-biancavilla-parte-la-bonifica-alla-ex-cava-di-monte-calvario/.

- Ufficio Regionale per l’espletamento di Gare per l’appalto dei lavori – UREGA, “Lavori per la bonifica e la Messa in Sicurezza Permanente dell’area di cava di Monte Calvario, causa la presenza delle pericolosa fibra (fluoro-edenite).,” Portale Gare d’appalto. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://urega.lavoripubblici.sicilia.it/gare/it/homepage.wp?actionPath=/ExtStr2/do/FrontEnd/Bandi/view.action¤tFrame=6&codice=G00181&_csrf=ELVHHPC4HHA9V1M6KWWW5RWUH277MHO.

- P. Comba, A. Gianfagna, and L. Paoletti, “Pleural Mesothelioma Cases in Biancavilla are Related to a New Fluoro-Edenite Fibrous Amphibole,” Archives of Envirnomental Health, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 229–232, 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. DeNardo, B. Bruni, L. Paoletti, R. Pasetto, and B. Sirianni, “Pulmonary fibre burden in sheep living in the Biancavilla area (Sicily): Preliminary results,” Science of the Total Environment, vol. 325, pp. 51–58, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, M. Angelone, G. Armiento, R. Pacifico, C. Cremisini, and A. Gianfagna, “Arsenic and fluorine in the Etnean volcanics from Biancavilla, Sicily, Italy: Environmental implications,” Environ Earth Sci, vol. 66, pp. 561–572, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Famoso, M. Mangiameli, P. Roccaro, G. Mussumeci, and F. G. A. Vagliasindi, “Asbestiform fibers in the Biancavilla site of national interest (Sicily, Italy): Review of environmental data via GIS platforms,” Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol, vol. 11, pp. 417–427, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, C. Gargano, A. Guercio, R. Punturo, and B. Rimoldi, “Workers’ risks in asbestos contaminated natural sites,” Journal of Mediterranean Earth Sciences, vol. 10, pp. 97–106, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Russo, G. Della Ventura, I. Campostrini, and D. Preite, “Nuove specie minerali al Monte Somma: I. la Fluoro-Edenite,” MICRO (notizie mineralogiche), pp. 173–174, 2009, Accessed: May 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.earth-prints.org/entities/publication/848999a2-06b5-4d67-b1b1-c3e7ea58a0c5.

- M. Rossi, F. Nestola, M. R. Ghiara, and F. Capitelli, “Fibrous minerals from Somma-Vesuvius volcanic complex,” Mineral Petrol, vol. 110, pp. 471–489, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry for the Environment and the Protection of Land and Sea – Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio, Decreto 18 luglio 2002: “Perimetrazione del sito di interesse nazionale di Biancavilla”. 2002, p. 21. Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/vediMenuHTML;jsessionid=NzBWHdn4cm3t+8groY9ipA__.ntc-as2-guri2a?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2002-10-02&atto.codiceRedazionale=02A11676&tipoSerie=serie_generale&tipoVigenza=originario.

- S. Branca, M. Coltelli, G. Groppelli, and F. Lentini, “Geological map of Etna volcano, 1:50,000 scale,” Italian Journal of Geosciences, vol. 130, no. 3, pp. 265–291, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Giuffrida, E. Nicotra, and M. Viccaro, “How an embryonic magma feeding system evolves: Insights from the primordial pulses of Mt. Etna volcano,” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, vol. 451, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Gillot, G. Kieffer, and R. Romano, “The Evolution of Mount Etna in the Light of Potassium-Argon Dating,” Acta Vulcanologica, vol. 5, pp. 81–87, 1994.

- M. Giuffrida, M. Cardone, F. Zuccarello, and M. Viccaro, “Etna 2011–2022: Discoveries from a decade of activity at the volcano,” Earth Sci Rev, vol. 245, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gianfagna, G. B. Andreozzi, P. Ballirano, S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, and B. M. Bruni, “Structural and chemical contrasts between prismatic and fibrous fluoro-edenite from Biancavilla, Sicily, Italy,” The Canadian Mineralogist, vol. 45, pp. 249–262, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Gianfagna, F. Scordari, S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, G. Ventruti, and L. Ottolini, “Fluorophlogopite from Biancavilla (Mt. Etna, Sicily, Italy): Crystal structure and crystal chemistry of a new F-dominant analog of phlogopite,” American Mineralogist, vol. 92, no. 10, pp. 1601–1609, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, G. B. Andreozzi, B. M. Bruni, A. Gianfagna, A. Pacella, and L. Paoletti, “Quantitative chemistry and compositional variability of fluorine fibrous amphiboles from Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy),” Periodico di Mineralogia, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 65–74, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Nicotra, M. Viccaro, C. Ferlito, and R. Cristofolini, “Influx of volatiles into shallow reservoirs at Mt. Etna volcano (Italy) responsible for halogen-rich magmas,” European Journal of Mineralogy, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 121–138, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, E. Nicotra, M. Viccaro, and A. Gianfagna, “Halogen-dominant mineralization at Mt. Calvario dome (Mt. Etna) as a response of volatile flushing into the magma plumbing system,” Mineral Petrol, vol. 106, pp. 89–105, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Mauro, J. Sejkora, Z. Dolníček, “Badalovite, NaNaMg(MgFe3+)(AsO4)3, and associated calciojohillerite, NaCaMgMg2(AsO4)3, from Biancavilla, Etna volcanic complex, Sicily, (Italy): occurrence and crystal chemistry”. Mineralogical Magazine, 1-21, 2025) . [CrossRef]

- R. Grimaldi and M. R. Pinizzotto, “Scavi nel SIN di Biancavilla, l’attività di ARPA Sicilia,” Ecoscienza, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 44–45, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, S. Cairo, D. Gastaldi, A. Gianfagna, S. Mazziotti Tagliani, G. Tosi, and C. Conti, “Characterization of fluoro-edenite by μ-Raman and μ-FTIR spectroscopy,” Mineral Mag, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 291–298, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Brancato, M. R. Pinizzotto, and G. Valastro, “La contaminazione da fluoro-edenite ed il modello Biancavilla (CT): L’esperienza di ARPA Sicilia nella gestione delle attività edilizie e di scavo dall’istituzione del SIN ai giorni nostri,” in TIC VI-GdL VI/03-SO VI/03-01 - Amianto: Linea guida per lo scavo, la movimentazione e il trasporto delle terre e rocce da scavo con amianto naturale e per i relativi criteri di monitoraggio, A. Defilippi, C. Cazzola, D. Ceseri, E. Scotti, G. Beccaris, L. Muto, M. L. Fercia, M. R. Pinizzotto, M. Zannellato, M. Morelli, R. Lonis, S. Bucci, S. Prandi, S. Galeani, and T. Bacci, Eds., Sistema Nazionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente, 2021, pp. 87–112.

- M. Soffritti, F. Minardi, L. Bua, D. Degli Esposti, and F. Belpoggi, “First experimental evidence of peritoneal and pleural mesotheliomas induced by fluoro-edenite fibres present in Etnean volcanic material from Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy),” European Journal of Oncology, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 169–175, Jun. 2004, [Online]. Available: https://hal.science/hal-04359150.

- V. Cardile, M. Renis, C. Scifo, L. Lombardo, R. Gulino, B. Mancari, and A. Panico, “Behaviour of the new asbestos amphibole fluoro-edenite in different lung cell systems,” International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, vol. 36, pp. 849–860, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Pugnaloni, G. Lucarini, F. Giantomassi, L. Lombardo, S. Capella, E. Belluso, A. Zizzi, A. M. Panico, G. Biagini, and V Cardile, “In vitro study of biofunctional indicators after exposure to asbestos-like fluoro-edenite fibres,” Cell Mol Biol, vol. 53, pp. 965–80, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Y. Grosse, D. Loomis, K. Z. Guyton, B. Lauby-Secretan, F. El Ghissassi, V. Bouvard, L. Benbrahim-Tallaa, N. Guha, C. Scoccianti, H. Mattock, K. Straif on behalf of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monograph Working Group, “Carcinogenicity of fluoro-edenite, silicon carbide fibres and whiskers, and carbon nanotubes,” Lancet Oncol, vol. 15, no. 13, pp. 1427–1428, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry for the Environment and the Protection of Land and Sea – Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio, Decreto 18 settembre 2001, n. 468: Regolamento recante “Programma nazionale di bonifica e ripristino ambientale.” 2002. Accessed: May 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2002/01/16/13/so/10/sg/pdf.

- Italian Ministry for the Environment and the Protection of Land and Sea – Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio, Decreto 8 luglio 2002, n. 231: “Perimetrazione del sito di interesse nazionale di Biancavilla”. 2002. Accessed: May 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2002/10/02/231/sg/pdf.

- World Healt Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe, Air quality guidelines for Europe, second edition, 2nd Edition., vol. European Series 91. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Publications, 2000.

- Biancavilla Oggi, “Amianto, vertice per la bonifica: quasi 18 mln per monte Calvario.” Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.biancavillaoggi.it/2019/11/06/amianto-vertice-per-la-bonifica-quasi-18-mln-per-monte-calvario/.

- Scordari, E. Schingaro, G. Ventruti, E. Nicotra, M. Viccaro, and S. Mazziotti-Tagliani, “Fluorophlogopite from Piano delle Concazze (Mt. Etna, Italy): Crystal chemistry and implications for the crystallization conditions,” American Mineralogist, vol. 98, no. 5–6, pp. 1017–1025, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Bellagamba, F. Paglietti, V. Di Molfetta, F. Damiani, and P. De Simone, “Gis for data management of environmental surveys, carried out in Biancavilla (CT) superfund experience,” Air Pollution, vol. XIX, pp. 199–209, 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Fiannacca, G. Ortolano, M. Pagano, R. Visalli, R. Cirrincione, and L. Zappalà, “IG-Mapper: A new ArcGIS® toolbox for the geostatistics-based automated geochemical mapping of igneous rocks,” Chem Geol, vol. 470, pp. 75–92, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Fazio, G. Ortolano, G. I. Alsop, A. D'Agostino, R. Visalli, V. Luzin, F. Salvemini, and R. Cirrincione, “Enhanced structural analysis through a hybrid analogue-digital mapping approach: Integrating field and UAV survey with microtomography to characterize metamorphic rocks,” J Struct Geol, vol. 187, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R. Di Stefano, V. Ricceri, M. La Rosa, A. Cernigliaro, P. Ciranni, G. Di Maria, D. Mandrioli, A. Zona, P. Comba, and S. Scondotto, “Fluoro-edenite non-neoplastic diseases in Biancavilla (Sicily, Italy): pleural plaques and/or pneumoconiosis?,” Ann Ist Super Sanita, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 187–193, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Campostrini, F. Demartin, P. Vignola, and F. Pezzotta, “Ferro-fluoro-edenite, a new amphibole endmember from Vulcano Island (Sicily, Italy),” The Canadian Mineralogist, vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 741–749, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Gualtieri and M. Leoncini, “Comparison of the toxicity/carcinogenicity of regulated and unregulated mineral fibres using the Fibre Potential Toxicity Index (FPTI)”. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 139202, 2025.

- P. Comba, C. Bruno, and D. Marsili, “Partnership between scientists and populations resident in contaminated sites. The case study of Biancavilla, Italy,” European Journal of Oncology and Environmental Health, vol. 29, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).